ABSTRACT

This study aimed to identify effective strategies for improving the uptake of influenza vaccination and to inform recommendations for influenza vaccination programs in Australia. A rapid systematic review was conducted to assimilate and synthesize peer-reviewed articles identified in PubMed. The National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) Hierarchy of Evidence was used to appraise the quality of evidence. A systematic search identified 4373 articles and 52 that met the inclusion criteria were included. The evidence suggests influenza vaccination uptake may be improved by interventions that (1) increase community/patient demand and access to influenza vaccine and overcome practice-related barriers; (2) reinforce the critical role healthcare providers play in driving influenza vaccination uptake. Strategies such as standing orders, reminder and recall efforts were successful in improving influenza vaccination rates. Community pharmacies, particularly in regional/remote areas, are well positioned to improve influenza vaccine coverage. The findings of this rapid review can be utilized to improve the performance of influenza immunization programs in Australia and other countries with comparable programs; and recommend priorities for future evaluation of interventions to improve influenza vaccination uptake.

Introduction

Most high-income countries have a national influenza vaccination policy with programmes targeting specific WHO-defined risk groups and yet uptake of the recommended influenza vaccinations among high-risk groups has been suboptimal.Citation1 In Australia, annual seasonal influenza vaccination is funded under the National Immunization Program (NIP) and State funded influenza programs for individuals in the following specific high-risk groups; pregnant women, people aged 6 months and older with medical risk factors, all children aged 6 months to less than 5 years of age, all Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people and everyone aged 65 years and over.Citation2 In South Australia, adults and children who are homeless and are not eligible for free flu vaccines under the National Immunization Programs are eligible for free flu vaccine under the state funded influenza Program.Citation2

The global coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic has increased demand for seasonal influenza vaccination.Citation3 Many countries, including Australia, have begun rolling out COVID-19 vaccination, which may complicate the delivery of seasonal influenza vaccination programs. Moreover, ongoing changes to influenza vaccination recommendations and policy changes have complicated program delivery at all levels of government and for all immunization providers. This rapid review aimed to identify effective strategies to improve influenza vaccine uptake, coordination and delivery of influenza vaccine programs and make recommendations for successful influenza vaccination programs in Australia by summarizing the literature evaluating strategies or influenza vaccination programs. Medical settings (hospital or primary setting) to venue-based and community-based approaches were included, in an effort to identify the features of such programs that are most successful and may guide efforts to increase the performance of influenza vaccination programs in Australia and similar high-income countries.

Materials and methods

Search strategy

A search was conducted of the English language literature in the PubMed/MEDLINE (PubMed delivers a publicly available search interface for MEDLINE as well) from 1st January 2011 through 1st August 2021. Keywords and terms used for the search included primarily the following: influenza, vaccination, uptake, intervention, strategies and program (Supplementary table 1).

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

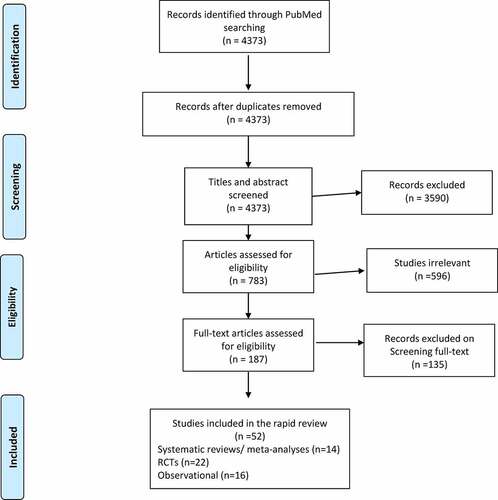

This rapid review is limited to studies that were explicitly, at least in part, concerned with evaluating an intervention or influenza vaccine program aimed at increasing influenza vaccine rates among individuals at high risk/vulnerable cohorts. Both systematic reviews and primary studies published in English were sought. Studies were included based on the methodological quality of their design and if they met the following criteria: were systematic reviews/meta-analyses or primary studies that used one of the following designs: (1) individual or cluster randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and quasi-randomized controlled trials; (2) controlled or uncontrolled before and after studies where participants were allocated to control and intervention groups using non-randomized methods; (3) interrupted time series with before and after measurements (). RCTs included in the eligible systematic reviews or meta-analyses were not individually included in this rapid review to avoid replication of any study findings.

Table 1. The inclusion and exclusion criteria for the rapid review followed the PICOS format

The National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) Level of Evidence table was used to appraise the quality of evidence found ().Citation4 Studies generating NHMRC levels V evidence or lower such as systematic reviews of descriptive and qualitative studies (levels V), a single descriptive or qualitative study or gray literature (levels VI), expert opinion or commentaries (levels VII) were excluded. The authors accept that the best available evidence is that which is least susceptible to bias, such as that provided by Levels I and II of the NHMRC levels of evidence (). However, a broader search strategy included studies more prone to bias (Levels III and IV) given most studies in this area are observational reflective of real-world data.

Table 2. NHMRC levels of evidence criteria

Organization of evidence

Each study was classified by the level of evidence it represented (). Levels of evidence start with a hierarchy of research designs that range from the greatest to least ability to reduce bias. Level I evidence is supported by the results of two or more RCTs (including meta-analysis of all relevant RCTs) producing the strongest and most definitive evidence.Citation4 Level II evidence produces tentative conclusions drawn from at least one good quality RCT or high-quality systematic reviews of RCTs and observational studies. Levels III produces limited evidence supported by at least one cohort study or single group interventions. Conflicting evidence is classified as disagreements between the findings of at least two RCTs or where RCTs are not available between two non-RCTs.Citation4 The recommendations were based on the majority of the studies, unless the study with conflicting results was of higher quality design.Citation4

Data collection

One reviewer (HM) independently reviewed identified titles and abstracts. Studies were sought in full text if they appeared eligible for inclusion against the criteria. Two reviewers (HM and PA) reviewed the identified relevant full text papers to determine eligibility. Detailed characteristics of included systematic reviews were captured and descriptively summarized in identifying study design, population, setting, measured outcomes and their main findings. A table of individual eligible studies (not included in the systematic reviews) is presented in Supplementary table 1, describing relevant information.

Table 3. Overall description and characteristics of the included systematic reviews

Results

The initial search generated 4373 published studies. After removing duplicates and screening titles, 187 relevant articles were identified for full review. Two members of the research team (HM & PA) read each relevant article for eligibility, utilizing the inclusion and exclusion criteria of the rapid review. Of the final included 52 studies that met the selection criteria, 14 were systematic literature reviews/meta-analyses, 22 were RCTs and 16 were observational studies (). No additional studies were obtained from the reference lists of the included studies. Differences in opinion were resolved by discussion.

Figure 1. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses (PRISMA) summary of the paper-screening process.

NHMRC level I and II: systematic reviews

The included systematic reviews covered in this rapid review incorporated i) a broad range of settings and intervention types for influenza vaccination programs targeting a variety of high risk/vulnerable groups, ii) influenza vaccine program or interventions for a particular high-risk group (e.g. pregnant women) or a particular setting (e.g. antenatal clinics or hospital providing services to pregnant women) and iii) an aspect of influenza vaccine programs/intervention within the articles reviewed, although the systematic review may not have been solely focused on influenza immunization programs (). For systematic reviews identified in this rapid review, the available evidence on the effectiveness of interventions are discussed among the high-risk groups i) people with medical conditions ii) elderly iii) pregnant women and iv) interventions targeted to the general population.

People with medical conditions

The systematic review by Sanftenberg et al.Citation7 (2019) included 15 RCTs that focused on primary care physicians and evaluated interventions to improve the uptake of influenza vaccination among people with chronic disease. The high-quality review (NHMRC level I)Citation7 demonstrated that training programs for medical practice teams that focused on particular chronic diseases improved influenza vaccination uptake by as much as 22% and may be more effective than vaccination-centered approaches. The reviewCitation7 also found that reminder systems for healthcare providers in primary care setting is another effective strategy with a maximum 3.8% absolute increase in vaccination rates among people with chronic illness (). Another systematic review of 11 studies (five RCTs and six quasi experimental)Citation15 (NHMRC level II) also demonstrated that implementation of reminder/recall systems improve influenza vaccination rates in children with asthma ().

Normal et al.Citation8 (2021) and Aigbogun et al.Citation9 (2014) conducted a systematic review of 35 studies (five RCTs and 29 non-RCTs) and 18 studies (seven RCTs & 12 non-RCTs) respectively assessing interventions aimed at increasing influenza vaccination rates in children with high-risk conditions. Normal et al.Citation8 (2021) identified a further 17 studies not captured by Aigbogun et al.Citation9 (2014) and pooled effect estimates for each intervention type in the included RCTs and other study methods (NHMRC level I). Both systematic reviewsCitation8,Citation9 found sufficient evidence that reminder letters to parents can improve influenza vaccination uptake in children with high-risk conditions ().

(ii) Elderly adults

Thomas et al.Citation5 (2018) conducted a systematic review of 61 RCTs focused on improving influenza vaccination rates in people aged 60 years and older in the community. Although heterogeneity limited some meta-analyses, the reviewCitation5 (NHMRC level I) identified strategies that demonstrated significant moderate effects of low (client reminders by postcards), medium (personalized phone calls), and high (home visits, facilitators) intensity interventions to increase community demand for vaccination, enhance access and provider or system response ().

(iii) Pregnant women

Two systematic reviewsCitation16,Citation18 collected the available evidence on the effectiveness of interventions used to improve influenza vaccination uptake in pregnant women. Reminders about influenza immunization on antenatal healthcare records, midwives providing vaccination, and education and information provision for healthcare providers (HCPs) and patients were found to be effective strategies in improving maternal influenza vaccination rates.Citation16,Citation18

(iv) The general population

A meta-analysis that pooled data from 8 RCTs (NHMRC level I) showed that educational interventions in general were not effective in improving influenza vaccination rates (OR = 1.16, 95% CI: 0.95–1.41) among different population groups.Citation6 However, a sub-group analysis demonstrated educational interventions delivered via text messages and personalized letters were effective in increasing influenza vaccination rates (OR = 1.30, 95% CI: 1.05–1.61), whilst educational interventions delivered via poster/pamphlet (OR = 1.00, 95% CI: 0.92–1.08), or face‐to‐face (OR = 1.16, 95% CI: 0.69–1.94) were ineffective.Citation6 Another systematic review of eight studiesCitation10 assessed the effect of providing patients with access to their Personal Electronic Health Records (PEHR) in improving vaccination uptake (four RCTs focused on influenza vaccine). Findings from an RCT included in this review found study participants with access to PEHR were 6.7% (intervention vs control: 11.6% vs 4.9%; p = .008) more likely to receive an influenza vaccine than those with no access to PEHR. A similar positive effect of PEHR on influenza vaccination uptake was observed in one of the other RCT, although improvements were not statistically significant (intervention vs control: 24% vs 19%; p = .50).Citation10 Moreover, two RCTs included in the review have demonstrated patients with access to PEHR in combination with messages promoting influenza vaccines (adjusted OR = 1.20, 95% CI: 1.06–1.35) or active vaccine reminders via electronic messages (intervention vs control: 22.0% vs 14.0%; p = .018) were effective in improving influenza vaccination uptake.Citation10

A reviewCitation11 of four RCTs that evaluated the use of multiple mail-order reminders suggested that more than one reminder sent by mail improves adherence to influenza vaccination in older adults. In contrast to these findings, multiple mail-order reminders to parents make little or no difference in adherence to influenza vaccination in children under 6 years of age. However, another systematic reviewCitation13 demonstrated reminders improve vaccinations for childhood influenza (RR 1.51, 95% CI 1.14 to 1.99; risk difference of 22%; five studies; 9265 participants) and adult influenza (RR 1.29, 95% CI 1.17 to 1.43; risk difference of 9%; 15 studies; 59,328 participants).

Okoli et al.Citation12 (2021) conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis of the effectiveness of interventions (included seven RCTs and 32 observational studies) on HCPs to improve seasonal influenza vaccination rates among patients. Pooled data from two RCTs (20.1%, 95% CI: 7.5–32.7%) and two observational studies (13.4%, 95% CI: 8.6–18.1%) showed that team-based training /education of physicians significantly increased influenza vaccination rates in adult patients as well as in pediatric patients (7%, 95% CI: 0.1–14%; two observational studies).Citation12 One-off provision of guidelines to physicians, and to both physicians and nurses, significantly improved influenza vaccination rates by an average 24% in adult patients (23.8%, 95% CI:15.7–31.8%; three observational studies) and pediatric patients (24%, 95% CI: 8.1–39.9%; two observational studies).Citation12

A systematic reviewCitation17 (included 31 studies) of hospital-based strategies in acute care settings aimed at improving influenza vaccination rates for adult inpatients showed that standing order protocols were significantly more effective than other individual interventions, but multi-component interventions (which included standing order protocols) were more effective than standing order protocols alone. Isenor et al.Citation14 (2016) conducted a high-quality systematic review and meta-analysis assessing the impact of pharmacists as educators, facilitators, and administrators of vaccines on immunization rates. Pharmacist participation in these three roles improved vaccination rates compared to vaccine provision by traditional providers without pharmacist involvement (). Citation14

NHMRC level II, III and IV: summary of primary research findings by setting and intervention and targeted population groups

For other individual studies included in this rapid review, influenza vaccine interventions or programs are discussed in five different settings i) hospital/tertiary-care settings ii) primary-care settings iii) venue-based iv) large-scale programs and v) targeted delivery.

Hospital/tertiary-care settings

Hospital-and tertiary-care-based programs for improving influenza vaccination rates generally focused on the provider and included standing orders and reminders to hospital staff. The evidence around influenza vaccination programs in hospital settings is both limited and generally of lower quality (mostly Levels III). One observational study evaluated the impact of an active choice intervention in the electronic health record (EHR) in improving influenza vaccination rates.Citation19 Rather than the standard approach of depending on HCPs to recognize the need for vaccination, the EHR confirmed patient eligibility during the hospital visit and used an alert to ask the HCP which resulted in a significant relative increase in influenza vaccination rates by 37.3% compared to the pre-intervention period.Citation19 Similarly, an observational study evaluated clinical decision support in the EHR and found it to improve influenza vaccination rate by 20 times higher a year after the program’s implementation.Citation20 One pre-post study assessed the effectiveness of a multifaceted intervention to improve influenza vaccination rates among children in a large pediatric hospital in the USA.Citation21 The interventions targeted medical and nursing providers and included web-based education modules, reminders in EHR and financial incentives (an end-of-year financial bonus) for resident doctors.Citation21 The intervention was associated with 1.23 (95% CI 1.11–1.35) times higher odds of a child receiving influenza vaccination at discharge.Citation21 Another four-year before-and-after observational study (n = 3734) evaluated a vaccination campaign of an Emergency Department (EDVC) at Bichat hospital in Paris with 80,000 visits per year.Citation22 The intervention during the fourth year incorporated standing orders to enable nurses to administer vaccines to patients admitted through the emergency department (ED) without an individually prescribed medication from doctors. The vaccination uptake of patients in ED setting was shown to effectively double during the post intervention period (33% to 66%) (Supplementary table 2).Citation22

(ii) Primary-care settings

Primary care was the most common setting for studies of influenza vaccination multicomponent programs for high-risk populations, and interventions were directed at the patient, provider, and/or organization levels. The evidence around influenza vaccination programs in a primary setting were generally higher quality (14 RCTs-level II & five level III studies) and the majority of the interventions incorporated in these studies were patient centered. Patient reminders were among the most frequent patient-level program components (portal & interactive voice response (IVR) callsCitation23,Citation24 and letters or text messaging influenza vaccine reminders.Citation6,Citation21,Citation25–30 Three RCTsCitation28–30 evaluated the effectiveness of text reminder to patients in combination with other promotional messages. Overall, these studiesCitation28–30 provided modest evidence that patient reminder systems to improve influenza vaccination rates in high-risk groups can be effective (Supplementary table 2).

Other patient-level interventions in primary care settings included advertising campaigns for influenza vaccination using posters and pamphlets in general practice sites for different at‐risk populations.Citation31–33 Whilst an RCTCitation31 evaluating clinic-based advertising to the elderly did not show improvement in influenza vaccine delivery, two other RCTs demonstrated significant increases in influenza vaccination rates in the elderly and children respectively.Citation32,Citation33 Additionally, one of the RCTsCitation34 demonstrated that websites with vaccine information and interactive social media components sent to pregnant women, positively influence maternal influenza vaccine uptake. Two longitudinal studiesCitation35,Citation36 evaluated provider focused intervention in primary care settings. The two studies assessed the effectiveness of implementation of a “best practice alert (BPA)” within the electronic medical record in an integrated pediatric health care delivery systemCitation35 and quality improvement initiative with continuing vaccine education for primary care physicians, respectively.Citation36 Whilst the BPA did not demonstrate a significant improvement in the uptake of influenza vaccination among pediatric subpopulation,Citation35 the 3-stage longitudinal educational intervention on physicians did significantly improve influenza vaccination rates by 3.4% in elderly patients >65 years of age and by 2.1% in high-risk groups (P < .001)Citation36 (Supplementary table 2).

(iii) Venue-based influenza vaccination delivery

An effective strategy for immunizing individuals at high risk of influenza is to target venues frequented by high-risk groups. Venues frequented by high-risk groups included nursing homes, which are specialized tertiary-care facilities. Evidence obtained from the systematic review (level I)Citation5 discussed above, demonstrated enhancing vaccine access in long‐term care facilities can improve influenza vaccination uptake among the elderly. Giles et al.Citation37(2018) assessed the feasibility of an outreach mobile influenza vaccination program led by a large hospital network targeting high‐risk and vulnerable populations in residential aged care facilities, sites attended by homeless people, and refugee centers in Melbourne, Australia. The pilot study has demonstrated the value and feasibility of a mobile outreach influenza immunization program focusing on hard‐to‐reach and vulnerable populations.Citation37 School-based influenza clinics are an alternative venue-based influenza vaccination delivery targeting school aged children. One of the RCTsCitation38 evaluated text message reminders sent to parents from the school nurse which did not improve children’s influenza vaccination rates. In contrast, the RCT by Humiston et al.Citation39 (2014) showed that school aged children are more likely to be vaccinated in school-located vaccination versus standard care control schools (Supplementary table 2).

(iv) Large-scale regional programs

Nine studies have evaluated large-scale vaccination interventions in different populations using a variety of approaches alone or in combination. Three RCTsCitation40–42 and one observational studyCitation43 examined the effect of centralized reminder/recall (autodialer, postcard, text reminders),Citation40 a state-wide immunization information system (IIS) for seasonal influenza vaccine reminders from local health departments,Citation41 large-scale messaging using mobile applicationsCitation42 and a free national text service providing influenza vaccination education and reminders.Citation43 The interventions in all these studies reported a modest impact on improving influenza vaccination coverage across large high-risk populations.Citation40–43 In contrast to the systematic review findings by Isenor et al.Citation14 recent studies of level III qualityCitation44–48 produced inconsistent results in the effectiveness of a large-scale pharmacy-based vaccine distribution in increasing influenza vaccination rates (Supplementary table 2). Two recent studiesCitation44,Citation45 that reported no association of improved influenza vaccine rates following pharmacist administered vaccination encounters were identified as having a high risk of bias, primarily due to non-randomized design and use of historical control data to compare changes in influenza vaccination rates.

(v) Influenza Immunization programs involving active community engagement

Community-wide programs are less commonly reported. Borg et al.Citation49 (2018) evaluated a communication-based program that sent personalized letter or pamphlets to parents of Victorian children (aged 6 months to <5 years) who identified as Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander aimed at increasing influenza vaccination coverage among Aboriginal children in Victoria, Australia. The communication program involved designs that align with recommendations for designing health information resources for Aboriginal communities (i.e. pamphlets including Aboriginal artwork, pictures of Aboriginal families). Sending pamphlets directly to parents/guardians did not improve vaccination rates but a personalized letter was found to be an effective strategy for improving influenza vaccination by 34% among Aboriginal children.Citation49 The authors suggested the lack of effectiveness of the pamphlet in improving vaccine uptake may be due to the lack of personalization and the authority related with the letter.Citation49 Esteban-Vasallo et al.Citation50 (2019) evaluated the effectiveness of influenza vaccination campaign in the Autonomous Community of Madrid improving the uptake of influenza vaccination in patients with rare diseases. The intervention including SMS text messaging and a reminder was modestly effective by an average 30% in improving influenza vaccination uptake in patients with rare diseases (Supplementary table 2).Citation50

Discussion

This rapid review was conducted to identify interventions that were effective in improving uptake of influenza vaccination in high-income countries to inform recommendations for influenza vaccination programs in Australia. Although the review identified 40 studies evaluating interventions aimed at increasing influenza vaccination rates, there was substantial heterogeneity in study designs, intervention types, target groups, settings and vaccination status ascertainment methods. Furthermore, several of the studies used multiple component interventions in their study population making it difficult to identify effectiveness by individual strategies.

Overall, recall/reminders for patients and HCP reminders had the highest level of evidence and were the most effective interventions in improving influenza vaccination rates in all high-risk groups and in all types of setting including from primary and tertiary hospitals to large-scale community interventions in the real-world settings.Citation5–9,Citation15,Citation18,Citation21,Citation25–30,Citation39–41,Citation43,Citation50,Citation51 Most reminders identified in this review incorporated educational information to either patients or HCPs. Although, the evidence on whether patient focused educational interventions in improving influenza vaccination uptake is mixed and varies with different target populations, they have shown a positive impact in improving vaccination uptake when administered through different outlets.Citation5,Citation7,Citation8,Citation14,Citation18,Citation33 Additionally, specific educational training programs for HCPs that sought to improve influenza vaccination rates in people at high risk for developing influenza-related complicationsCitation36 including people with chronic illnessCitation7 was successful. Another important provider-centered approach is standing orders which have been applied in various settings, such as in clinics, hospitals,Citation18 emergency rooms,Citation22 and community pharmacies.Citation14 Standing orders allowing community pharmacists,Citation14 nurses,Citation22 and midwivesCitation16,Citation18 to administer vaccination without medical prescription has improved influenza vaccination rates in different high risk groups.

The present rapid review revealed that pharmacist participation in vaccination as educators, facilitators, or administrators of vaccines has improved influenza vaccination rates.Citation14 Across Australia there has been progressive implementation of pharmacist-administered vaccination programs and Western Australia was the first state to comprehensively evaluate the program.Citation52 The evaluation report suggested a high proportion of pharmacist administered vaccinations in regional areas with 12% to 17% of consumers receiving the vaccine in pharmacies despite their eligibility to receive free influenza vaccinations under NIP.Citation52 Victoria is the only state in Australia that allow pharmacists to administer both government-funded (NIP) and privately purchased vaccines in either a community or hospital-based pharmacy.Citation53 Although pharmacist vaccination account for a small percentage of vaccinations in Australia (2.7% in 2019),Citation54 a recent report indicated that COVID-19 pandemic has affected the capability of pharmacists in Australia to offer vaccination services.Citation55 Community pharmacists are well positioned to improve influenza vaccination rates, considering that influenza vaccine programs being rolled out in 2021 alongside the COVID-19 vaccines is creating logistical challenges.Citation54,Citation55

Strengths and limitations

This was a rapid systematic review, conducted under time constraints in order to be relevant and apply findings from current evidence to the context of COVID-19. This review was originally conducted as part of an independent evaluation to determine the best process for distribution and increase uptake of publically funded influenza vaccine in South Australia. The review was expanded to identify strategies that were effective in improving uptake of influenza vaccination in high-income countries to inform recommendations for influenza vaccination programs in Australia. Therefore there was no published a priori protocol for the present rapid review. Although rapid review methods enable a timely review of publications, they do involve trade-offs compared with the methodological rigor of an in-depth systematic review.Citation56 Other limitations of this rapid review are the small number of studies particularly in the Australian context and the poor methodological quality of most observational studies. Meta-analysis was not possible in this review due to the heterogeneity of study designs and outcome measures used in the included studies.

Recommendations and public health and policy implications

The authors suggest that the evidence found in this review supports the following recommendations:

Patient level

Deliver community wide education and information regarding influenza vaccination to a target high-risk groups through different outlets including posters, leaflets, booklet, brochure and educational-text message or letter reminders.

Set up patient reminder/recall systems. Send alerts that influenza vaccinations are due (reminders) or late (recall) to high-risk groups; delivery techniques can include telephone calls, postcards, letters or mail tailored to patient’s needs.

The evidence, while limited, suggest delivery of culturally appropriate interventions for Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islanders within Aboriginal health services might improve influenza vaccination rates.

Provider or system level

Standing orders: empower and authorize nurses/midwives, community pharmacists to deliver seasonal influenza vaccinations without a medical order.

Pharmacist-administered vaccination programs may have an important role in improving influenza vaccination coverage in Australia particularly in regional and rural areas where there may be difficulty in accessing other primary healthcare services.

Encourage computer-based clinical decision support systems for vaccine providers in a variety of settings including clinics, hospitals, and residential aged care facilities.

Provider reminders/recall system: Notify those who administer influenza immunization that individual patients are due (reminder) or overdue (recall) for vaccination.

Deliver information to immunization providers to increase their knowledge; techniques include vaccine education and training programs and computer-based learning programs.

Assess the feasibility of improving access to influenza vaccine for vulnerable populations for example a mobile service that attends relevant sites attended by homeless people.

Disclosure of potential conflicts of interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Ortiz JR, Perut M, Dumolard L, Wijesinghe PR, Jorgensen P, Ropero AM, Danovaro-Holliday MC, Heffelfinger JD, Tevi-Benissan C, Teleb NA, et al. A global review of national influenza immunization policies: analysis of the 2014 WHO/UNICEF joint reporting form on immunization. Vaccine. 2016;34(45):5400–05. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2016.07.045.

- The Australian Government Department of Health and Ageing. Australian technical advisory group on immunisation Canberra 2019.

- Wang X, Kulkarni D, Dozier M, Hartnup K, Paget J, Campbell H, Nair H. Usher network for C-ERg. Influenza vaccination strategies for 2020–21 in the context of COVID-19. J Global Health. 2020;10:021102.

- Merlin T, Weston A, Tooher R. Extending an evidence hierarchy to include topics other than treatment: revising the Australian ‘levels of evidence.’ BMC Med Res Methodol. 2009;9:34. doi:10.1186/1471-2288-9-34.

- Thomas RE, Lorenzetti DL. Interventions to increase influenza vaccination rates of those 60 years and older in the community. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;5:Cd005188.

- Zhou X, Zhao X, Liu J, Yang W. Effectiveness of educational intervention on influenza vaccine uptake: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Iran J Public Health. 2020;49:2256–63.

- Sanftenberg L, Brombacher F, Schelling J, Klug SJ, Gensichen J. Increasing influenza vaccination rates in people with chronic illness. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2019;116:645–52.

- Norman DA, Barnes R, Pavlos R, Bhuiyan M, Alene KA, Danchin M, Seale H, Moore HC, Blyth CC. Improving influenza vaccination in children with comorbidities: a systematic review. Pediatrics. 2021;147(3):e20201433. doi:10.1542/peds.2020-1433.

- Aigbogun NW, Hawker JI, Stewart A. Interventions to increase influenza vaccination rates in children with high-risk conditions–a systematic review. Vaccine. 2015;33(6):759–70. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2014.12.013.

- Balzarini F, Frascella B, Oradini-Alacreu A, Gaetti G, Lopalco PL, Edelstein M, Azzopardi-Muscat N, Signorelli C, Odone A. Does the use of personal electronic health records increase vaccine uptake? A systematic review. Vaccine. 2020;38(38):5966–78. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2020.05.083.

- Julio C, Silva N, Ortigoza Á. Multiple mail reminders to increase adherence to influenza vaccination. Medwave. 2020;20(6):e7963. doi:10.5867/medwave.2020.06.7962.

- Okoli GN, Reddy VK, Lam OLT, Abdulwahid T, Askin N, Thommes E, Chit A, Abou-Setta AM, Mahmud SM. Interventions on health care providers to improve seasonal influenza vaccination rates among patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis of the evidence since 2000. Fam Pract. 2021;38(4):524–36. doi:10.1093/fampra/cmaa149.

- Jacobson Vann JC, Jacobson RM, Coyne-Beasley T, Asafu-Adjei JK, Szilagyi PG. Patient reminder and recall interventions to improve immunization rates. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;1:Cd003941.

- Isenor JE, Edwards NT, Alia TA, Slayter KL, MacDougall DM, McNeil Sa, Bowles SK. Impact of pharmacists as immunizers on vaccination rates: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Vaccine. 2016;34(47):5708–23. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2016.08.085.

- Jones Cooper SN, Walton-Moss B. Using reminder/recall systems to improve influenza immunization rates in children with asthma. J Pediatr Health Care. 2013;27(5):327–33. doi:10.1016/j.pedhc.2011.11.005.

- Wong VW, Lok KY, Tarrant M. Interventions to increase the uptake of seasonal influenza vaccination among pregnant women: a systematic review. Vaccine. 2016;34(1):20–32. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.11.020.

- McFadden K, Seale H. A review of hospital-based interventions to improve inpatient influenza vaccination uptake for high-risk adults. Vaccine. 2021;39(4):658–66. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2020.12.042.

- Bisset KA, Paterson P. Strategies for increasing uptake of vaccination in pregnancy in high-income countries: a systematic review. Vaccine. 2018;36(20):2751–59. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2018.04.013.

- Patel MS, Volpp KG, Small DS, Wynne C, Zhu J, Yang L, Honeywell S Jr., Sc D. Using active choice within the electronic health record to increase influenza vaccination rates. J Gen Intern Med. 2017;32(7):790–95. doi:10.1007/s11606-017-4046-6.

- Buenger LE, Webber EC. Clinical decision support in the electronic medical record to increase rates of influenza vaccination in a pediatric emergency department. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2020;36(11):e641–e5. doi:10.1097/PEC.0000000000001998.

- Rao S, Ziniel SI, Khan I, Dempsey A. Be inFLUential: evaluation of a multifaceted intervention to increase influenza vaccination rates among pediatric inpatients. Vaccine. 2020;38(6):1370–77. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2019.12.010.

- Casalino E, Ghazali A, Bouzid D, Antoniol S, Kenway P, Pereira L, Choquet C. Emergency department influenza vaccination campaign allows increasing influenza vaccination coverage without disrupting time interval quality indicators. Intern Emerg Med. 2018;13(5):673–78. doi:10.1007/s11739-018-1852-8.

- Cutrona SL, Golden JG, Goff SL, Ogarek J, Barton B, Fisher L, Preusse P, Sundaresan D, Garber L, Mazor KM. Improving rates of outpatient influenza vaccination through EHR portal messages and interactive automated calls: a randomized controlled trial. J Gen Intern Med. 2018;33(5):659–67. doi:10.1007/s11606-017-4266-9.

- Wijesundara JG, Ito Fukunaga M, Ogarek J, Barton B, Fisher L, Preusse P, Sundaresan D, Garber L, Mazor KM, Cutrona SL. Electronic health record portal messages and interactive voice response calls to improve rates of early season influenza vaccination: randomized controlled trial. J Med Internet Res. 2020;22(9):e16373. doi:10.2196/16373.

- Herrett E, Williamson E, van Staa T, Ranopa M, Free C, Chadborn T, Goldacre B, Smeeth L. Text messaging reminders for influenza vaccine in primary care: a cluster randomised controlled trial (TXT4FLUJAB). BMJ Open. 2016;6(2):e010069. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2015-010069.

- Regan AK, Bloomfield L, Peters I, Effler PV. Randomized controlled trial of text message reminders for increasing influenza vaccination. Ann Fam Med. 2017;15(6):507–14. doi:10.1370/afm.2120.

- Yudin MH, Mistry N, De Souza LR, Besel K, Patel V, Blanco Mejia S, Bernick R, Ryan V, Urquia M, Beigi RH, et al. Text messages for influenza vaccination among pregnant women: a randomized controlled trial. Vaccine. 2017;35(5):842–48. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2016.12.002.

- Milkman KL, Patel MS, Gandhi L, Graci HN, Gromet DM, Ho H, Kay JS, Lee TW, Akinola M, Beshears J, et al. A megastudy of text-based nudges encouraging patients to get vaccinated at an upcoming doctor’s appointment. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2021;118:20. doi:10.1073/pnas.2101165118.

- Stockwell MS, Kharbanda EO, Martinez RA, Vargas CY, Vawdrey DK, Camargo S. Effect of a text messaging intervention on influenza vaccination in an urban, low-income pediatric and adolescent population: a randomized controlled trial. Jama. 2012;307(16):1702–08. doi:10.1001/jama.2012.502.

- Stockwell MS, Westhoff C, Kharbanda EO, Vargas CY, Camargo S, Vawdrey DK, Castaño PM. Influenza vaccine text message reminders for urban, low-income pregnant women: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(Suppl1):e7–12. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2013.301620.

- Berkhout C, Willefert-Bouche A, Chazard E, Zgorska-Maynard-Moussa S, Favre J, Peremans L, Ficheur G, Van Royen P. Randomized controlled trial on promoting influenza vaccination in general practice waiting rooms. PLoS One. 2018;13(2):e0192155. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0192155.

- Ho HJ, Tan YR, Cook AR, Koh G, Tham TY, Anwar E, Hui CGS, Lwin MO, Chen MI. Pneumococcal vaccination uptake in seniors using point-of-care informational interventions in primary care in Singapore: a pragmatic, cluster-randomized crossover trial. Am J Public Health. 2019;109(12):1776–83. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2019.305328.

- Scott VP, Opel DJ, Reifler J, Rikin S, Pethe K, Barrett A, Stockwell MS. Office-based educational handout for influenza vaccination: a randomized controlled trial. Pediatrics. 2019;144:2. doi:10.1542/peds.2018-2580.

- O’Leary ST, Narwaney KJ, Wagner NM, Kraus CR, Omer SB, Glanz JM. Efficacy of a web-based intervention to increase uptake of maternal vaccines: an RCT. Am J Prev Med. 2019;57(4):e125–e33. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2019.05.018.

- Bratic JS, Cunningham RM, Belleza-Bascon B, Watson SK, Guffey D, Boom JA. Longitudinal evaluation of clinical decision support to improve influenza vaccine uptake in an integrated pediatric health care delivery system, Houston, Texas. Appl Clin Inform. 2019;10(5):944–51. doi:10.1055/s-0039-3400748.

- Kawczak S, Mooney M, Mitchner N, Senatore V, Stoller JK. The impact of a quality improvement continuing medical education intervention on physicians’ vaccination practice: a controlled study. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2020;16(11):2809–15. doi:10.1080/21645515.2020.1737457.

- Giles ML, Hickman J, Lingam V, Buttery J. Results from a mobile outreach influenza vaccination program for vulnerable and high-risk populations in a high-income setting: lessons learned. Aust NZ J Public Health. 2018;42(5):447–50. doi:10.1111/1753-6405.12810.

- Szilagyi PG, Schaffer S, Rand CM, Goldstein NPN, Younge M, Mendoza M, Albertin CS, Concannon C, Graupman E, Hightower AD, et al. Text message reminders for child influenza vaccination in the setting of school-located influenza vaccination: a randomized clinical trial. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 2019;58(4):428–36. doi:10.1177/0009922818821878.

- Humiston SG, Schaffer SJ, Szilagyi PG, Long CE, Chappel TR, Blumkin AK, Szydlowski J, Kolasa MS. Seasonal influenza vaccination at school: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Prev Med. 2014;46(1):1–9. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2013.08.021.

- Hurley LP, Beaty B, Lockhart S, Gurfinkel D, Breslin K, Dickinson M, Whittington MD, Roth H, Kempe A. RCT of centralized vaccine reminder/recall for adults. Am J Prev Med. 2018;55(2):231–39. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2018.04.022.

- Dombkowski KJ, Harrington LB, Dong S, Clark SJ. Seasonal influenza vaccination reminders for children with high-risk conditions: a registry-based randomized trial. Am J Prev Med. 2012;42(1):71–75. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2011.09.028.

- Lee W-N, Stück D, Konty K, Rivers C, Brown CR, Zbikowski SM, Foschini L. Large-scale influenza vaccination promotion on a mobile app platform: a randomized controlled trial. Vaccine. 2020;38(18):3508–14. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2019.11.053.

- Jordan ET, Bushar JA, Kendrick JS, Johnson P, Wang J. Encouraging influenza vaccination among Text4baby pregnant women and mothers. Am J Prev Med. 2015;49(4):563–72. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2015.04.029.

- Atkins K, van Hoek AJ, Watson C, Baguelin M, Choga L, Patel A, Raj T, Jit M, Griffiths U. Seasonal influenza vaccination delivery through community pharmacists in England: evaluation of the London pilot. BMJ Open. 2016;6(2):e009739. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2015-009739.

- Deslandes R, Evans A, Baker S, Hodson K, Mantzourani E, Price K, Way C, Hughes L. Community pharmacists at the heart of public health: a longitudinal evaluation of the community pharmacy influenza vaccination service. Res Social Adm Pharm. 2020;16(4):497–502. doi:10.1016/j.sapharm.2019.06.016.

- Patel AR, Breck AB, Law MR. The impact of pharmacy-based immunization services on the likelihood of immunization in the United States. J Am Pharm Assoc (2003). 2018;58(5):505–14.e2. doi:10.1016/j.japh.2018.05.011.

- Isenor JE, Alia TA, Killen JL, Billard BA, Halperin BA, Slayter KL, McNeil SA, MacDougall D, Bowles SK. Impact of pharmacists as immunizers on influenza vaccination coverage in Nova Scotia, Canada. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2016;12(5):1225–28. doi:10.1080/21645515.2015.1127490.

- Isenor JE, O’Reilly BA, Bowles SK. Evaluation of the impact of immunization policies, including the addition of pharmacists as immunizers, on influenza vaccination coverage in Nova Scotia, Canada: 2006 to 2016. BMC Public Health. 2018;18(1):787. doi:10.1186/s12889-018-5697-x.

- Borg K, Sutton K, Beasley M, Tull F, Faulkner N, Halliday J, Knott C, Bragge P. Communication-based interventions for increasing influenza vaccination rates among Aboriginal children: a randomised controlled trial. Vaccine. 2018;36(45):6790–95. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2018.09.020.

- Esteban-Vasallo MD, Domínguez-Berjón MF, García-Riolobos C, Zoni AC, Aréjula Torres JL, Sánchez-Perruca L, Astray-Mochales J. Effect of mobile phone text messaging for improving the uptake of influenza vaccination in patients with rare diseases. Vaccine. 2019;37(36):5257–64. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2019.07.062.

- Yeung KHT, Tarrant M, Chan KCC, Tam WH, Nelson EAS. Increasing influenza vaccine uptake in children: a randomised controlled trial. Vaccine. 2018;36(37):5524–35. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2018.07.066.

- Hattingh HL, Sim TF, Parsons R, Czarniak P, Vickery A, Ayadurai S. Evaluation of the first pharmacist-administered vaccinations in Western Australia: a mixed-methods study. BMJ Open. 2016;6(9):e011948–e. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2016-011948.

- Department of Health Victoria. Evaluation of the victorian pharmacist administered vaccination program.2018. [accessed 2021 April 9]. https://www2.health.vic.gov.au/about/publications/ResearchAndReports/pharmacist-administered-vaccination-program-evaluation

- The National Centre for Immunisation Research and Surveillance (NCIRS). Review of pharmacist vaccination reporting to the Australian Immunisation Register New South Wales, Australia. 2020 [accessed 2021 April 9]. https://www.ncirs.org.au/sites/default/files/2020-06/Review%20of%20pharmacist%20vaccination%20reporting%20to%20the%20AIR_Final%20report_May%202020.pdf.

- Patel C, Dalton L, Dey A, Macartney K, Letter: BF. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on pharmacist-administered vaccination services. Res Social Adm Pharm. 2021;17(1):2040–41. doi:10.1016/j.sapharm.2020.08.021.

- O’Leary DF, Casey M, O’Connor L, Stokes D, Fealy GM, O’Brien D, Smith R, McNamara MS, Egan C. Using rapid reviews: an example from a study conducted to inform policy-making. J Adv Nurs. 2017;73(3):742–52. doi:10.1111/jan.13231.