ABSTRACT

Background

Vaccination against COVID-19 is the key to controlling the pandemic. Parents are the decision makers in the case of children vaccination as they are responsible for them. This study aims to investigate the acceptability of COVID-19 vaccination for children among parents in Saudi Arabia.

Methods

This cross-sectional study used an online self-administered questionnaire. A 35-items questionnaire was distributed via social media platforms between June 6 and July 9–2021. Descriptive statistics were used to describe the participants’ characteristics. Categorical variables were reported as frequencies and percentages. Predictors of vaccination acceptance were identified using binary logistic regression.

Results

A total of 581 parents were involved in this study. A majority of parents 63.9% reported that they will vaccinate their children if the vaccine becomes available. Around 40% of them confirmed that they want their child to be among the first to receive the COVID-19 vaccine. Nearly a quarter, 23.9%, reported that they will vaccinate their child against influenza this year. The most commonly reported reason for hesitancy was poor awareness about the vaccine’s effectiveness on children. Adequate information about the COVID-19 vaccine was the most agreed cause to accept the vaccine. Having five or more children was a significant predictor for poor vaccination acceptance (OR: 0.42 (95%CI: 0.21–0.86), p < .05).

Conclusion

An appropriate proportion of parents are willing to vaccinate their children if the vaccine becomes available for children in Saudi Arabia. Public health awareness must be raised to gain public trust in the vaccination and the healthcare system.

1. Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic has had a catastrophic global impact.Citation1,Citation2 Locally, in Saudi Arabia COVID-19 is prevalent and cause a considerable hospitalization rate since the beginning of the pandemic.Citation3 In Saudi Arabia, multiple studies reported how COVID-19 affected the population clinical and mental outcomes.Citation4–8

Although children may experience milder infections, severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS)-CoV-2 infection has severe clinical symptoms that can affect children of various ages. It has several negative consequences for children, including social isolation and disruption to their education.Citation9 In addition, children with underlying medical conditions and/or compromised immune systems are at a higher risk of serious disease. Little is known regarding the long-term consequences of COVID-19 infection and its complications, such as multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C).Citation2

Since preventive measures alone are not sufficient to control the spread of COVID-19, vaccination against COVID-19 is essential.Citation10 Vaccination has reduced the incidence of infectious diseases, as well as the morbidity and mortality associated with them, and has raised average life expectancy.Citation11 The development of an efficient COVID-19 vaccine is critical to reducing the individual risks associated with the infection in children and community transmission. Therefore, to restrict the transmission of COVID-19, an estimated 60–72% coverage is required to achieve the herd immunity threshold, and children’s vaccinations are a key element in establishing this.Citation12

Recently, the United States (US) Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and the US Centers for Disease Control (CDC) have expanded the emergency use authorization (EUA) for the COVID-19 Pfizer vaccine to teenagers aged 12–15.Citation13 Children aged less than 18 are not yet candidates to receive the vaccine in Saudi Arabia, but they can register them to take the vaccine once it is available, by a smartphone app called Sehhaty.Citation14

As vaccines become more widely available, proper distribution and administration will be critical to ensure a safe return to normal daily life.Citation2 There is uncertainty about willingness and acceptance among parents regarding vaccinating their children against COVID-19, with a lot of concern about the vaccine’s safety and efficacy and its rapid production. Several international studies investigated this subject, including studies in Germany, UK, China and Turkey.Citation12,Citation15–18 However, previous studies in the Middle East are limited.

Understanding caregivers’ willingness to accept COVID-19 vaccination for their children and related barriers and facilitators is crucial. To our knowledge, there have been no studies investigating parental acceptance of COVID-19 vaccination for their children in Saudi Arabia. Therefore, this study aims to investigate the parental acceptance of free COVID-19 vaccination for children under the age of 18 years among parents in Saudi Arabia.

2. Methods

2.1. Study design

A cross-sectional study using an online self-administered questionnaire was conducted between 6 June and 9 July 2021 in Saudi Arabia.

2.2. Sampling strategy

Convenience sampling techniques were used to recruit the study participants. Residents of Saudi Arabia (including citizens and non-citizens) aged 18 years and older who have children were invited to participate in the study. These inclusion criteria were highlighted in the invitation letter that was sent along with the study survey link. Social media platforms such as WhatsApp, Twitter, and Facebook were used to recruit the study participants. All participants voluntarily participated in the study and there was, therefore, no need for written informed consent. The study aims and objectives were clearly explained in the invitation letter.

2.3. Questionnaire tool

The questionnaire was adapted from previously validated assessment scales.Citation12,Citation19 The questionnaire consisted of 35 items divided into four sections. Section One involved demographic information, including basic information regarding age of the parents, marital status, educational level, history of chronic disease in the family, and COVID-19 vaccine status. Section Two involved COVID-19 and influenza vaccine willingness. In Section Three we used a 5-point Likert scale to assess parents’ perspectives toward the severity of and susceptibility to COVID-19 infection. Section Four included reasons for hesitancy, perceived benefits, and reasons/causes for action.

2.4. Sample size

To estimate the sample size, we used the WHO recommendations for the minimal sample size needed for a prevalence study.Citation20 Using a confidence interval of 95%, a standard deviation of 0.5, and a margin of error of 5%, the required sample size was 385 participants from each study population.

2.5. Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using Statistical Package for Social Science (SPSS) software, Version 27 (IBM Corp, Armonk, NY, USA). Descriptive statistics were used to describe the participants’ characteristics. Categorical variables were reported as frequencies and percentages. Predictors of vaccination acceptance were identified using binary logistic regression analysis. A confidence interval of 95% (p < .05) was applied to represent the statistical significance of the results, and the level of significance was assigned as 5%.

2.6. Ethical approval

This study was approved by the faculty of Medicine at University of Umm Alqura, Mecca, Saudi Arabia, (NO. HAPO-02-K-012-2021-06-695).

3. Results

3.1. Participant’s demographic characteristics

A total of 581 participants were involved in this study. More than half of them (61.3%) were mothers. Around 46% of the study participants were aged 30–39 years old. The vast majority of them (94.7%) were married and residents (85.7%) of the western area of Saudi Arabia. Around two-thirds of the study participants have a college degree or the equivalent. Around 12% of the study participants reported a history of chronic disease. Over a third (38.2%) of the participants reported that they have a family member with one or more chronic diseases. The majority of them (71.9%) reported that they had received the COVID-19 vaccine. A similar percentage (71.6%) reported that they would advise others to receive the COVID-19 vaccine. For further details on participants’ demographic characteristics, refer to .

Table 1. Participants demographic characteristics

3.2. Information about children

Around one-third of the study participants reported that they have two children. More than half (61.8%) of the study participants reported that the age of their children ranged between 7 and 12 years. The vast majority of them (91.0%) reported that their children were up to date with their other vaccines. Only 3.8% of the study participants reported that have a vaccine refusal history. The most commonly reported reasons for vaccine refusal history were reading published articles about the safety/harmful effect of the vaccine, not believing in the benefit of the vaccine, and allergies. Around two-thirds of the study participants reported that the child’s age affected their decision (Example: it is unsafe to vaccinate your infant/ toddler); for details see .

Table 2. Child information

3.3. Perceptions about COVID-19

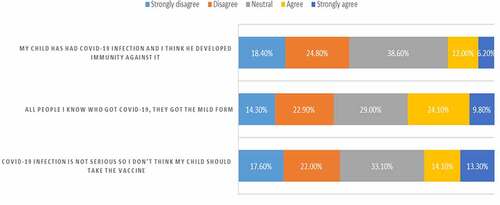

Just under one fifth (18.2%) the study participants reported that they believe their children had developed immunity against COVID-19 because they had had the infection. One-third of the study participants (33.9%) reported that all people they had contact with had developed only mild COVID-19 symptoms when they got infected. Over a quarter (27.4%) of them believed that COVID-19 infection was not serious, and they should not vaccinate their children; see .

3.4. Attitude toward the vaccine

3.4.1. Acceptance of the vaccine

Nearly two-thirds of the study participants (63.9%) reported that they will vaccinate their children if the vaccine becomes available. Around 40% of them confirmed that they want their child to be among the first to receive the COVID-19 vaccine. Just under one-quarter of the study participants (23.9%) reported that they will vaccinate their child against influenza this year.

3.4.2. Reasons for hesitancy

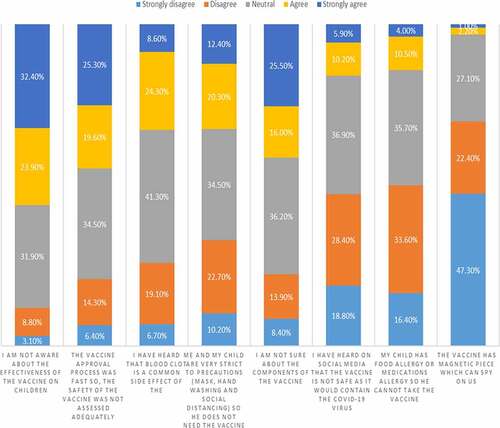

The most commonly reported reasons for hesitancy about vaccinating children with the COVID-19 vaccine were 1) poor awareness about the effectiveness of the vaccine on children (56.3% agreed with this reason), 2) because the vaccine approval process was fast, so the safety of the vaccine was not assessed adequately (44.9% agreed with this reason), and 3) they had heard that blood clots were a common side effect of the vaccine (32.9% agreed with this reason); see .

3.4.3. Reasons for action

When the participants were asked about their reasons for vaccinating their children against COVID-19, 55.3% agreed that they would only let their children receive the COVID-19 vaccine if they were given adequate information about it. Around 40% of them agreed that they would only let their children receive the COVID-19 vaccine if it was made mandatory, and a similar percentage agreed that they would only let their children receive the COVID-19 vaccine if the vaccine were taken by many children in the public; see .

Table 3. Attitude toward the vaccine

3.4.4. Perceived benefits

When the participants were asked about the perceived benefits from COVID-19 vaccine, 54.9% agreed that vaccination would ease the precautionary measures including lock down, quarantine, work permit and travel ban, 54.5% agreed that vaccination decreases my child chance of getting COVID-19 or its complication, 51.8% agreed that complications of COVID-19 will be decrease significantly if my child received the vaccine, and 48.5% agreed that if their children take the vaccine that would make them less worried about catching COVID-19, .

3.4.5. Vaccination acceptance predictors

Binary logistic regression analysis was conducted to identify predictors of vaccination acceptance, . There was no statistically significant difference in vaccination acceptance between participants from different demographic characteristics, except for number of children; for which we found that parents who have five or more children have lower acceptance toward vaccination (OR: 0.42 (95%CI: 0.21–0.86), p < .05).

Table 4. Predictors of vaccination acceptance

4. Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study investigating caregivers’ willingness and acceptance of COVID-19 vaccinations in Saudi Arabia that provides preliminary data to inform policymaking for future child COVID-19 vaccination plans.

In this study, approximately two thirds (63.9%) of Saudi parents were willing to have their children vaccinated against COVID-19. This result was similar to that of comparable studies, in which the percentage of parents’ willingness was 59.3% in China and 65% in an international study conducted in six countries.Citation12,Citation21 A lower rate was reported in studies done in Turkey and Germany, in which 36.3% and 51%, respectively, of parents stated that they would vaccinate their children against COVID-19.Citation15,Citation17 In contrast, higher percentages of willingness were also reported previously. One study in China reported that 72.6% of parents were willing to vaccinate their children; however, the study sample was limited to factory workers, with 66.6% of them being frontline workers.Citation18 In England 89% of parents stated that they are ‘definitely’ or ‘unsure but leaning towards yes’ when asked about their plans to have their children vaccinated against COVID-19. Most of the English study participants (95%) were mothers, unlike the current study, in which the percentage of mothers was 61.3%.Citation16 In the United States 80% of the parents were willing to vaccinate their children.Citation22 According to these studies, parental acceptance of COVID-19 vaccination varied widely among countries.

The Ministry of Health (MOH) in Saudi Arabia continues to provide free coronavirus immunization to all citizens and residents who register for using the Sehhaty App. The service is provided at several locations around the country.Citation19 Besides the high levels of parents’ willingness reported by the current study, about three quarters (71.9%) of parents were vaccinated against COVID-19. The high percentages of willingness and acceptance reported by the current study represent the parents’ confidence in vaccination and the healthcare system and the government in general.

Despite the high levels of vaccine acceptance, a degree of vaccine hesitancy was observed in the current study. The efficacy and safety of vaccination was the most important aspect in vaccine uptake decisions; 56.3% of parents had poor awareness about the effectiveness of the COVID-19 vaccine on their children. In addition, 44.9% of parents agreed that the vaccine’s safety was not assessed adequately because the vaccine approval process was fast. These findings seem to be consistent with other research, which found that a high level of vaccination hesitancy might be explained by fear of socio-political pressures potentially leading to fast approval of the COVID-19 vaccination without adequate assurances of safety and efficacy.Citation23 Also, the frequency of unclear scientific results is relatively high, potentially lowering public trust and increasing the percentage of resistance.Citation17,Citation24

On the other side, the perceived benefit of the vaccination was a motivating factor noticed in this study. COVID-19 and its precautionary measures have undoubtedly had a negative impact on people’s daily lives and routines, and the closure of schools and the lack of social activities have affected children’s emotional and psychological development.Citation25,Citation26 Therefore, the desire to return to normal daily life is an expected motivation to receive the vaccine. As reported in a survey-based study done in Saudi Arabia, 46.7% of the participants agreed that easing the preventive measures would be a perceived benefit of the vaccination.Citation19 This was also noted in this study by approximately 55% of the participants. Decreasing the chance of contracting COVID-19 and protecting children against severe complications are other significant potential benefits of vaccination.Citation25 In our sample, over half of the participants (54.5%) believed that vaccinating their children against COVID-19 would decrease their children’s chance of contracting COVID-19, and (51.8%) believed that COVID-19 complications would be reduced significantly if their children were vaccinated.

However, one third of the study participants (33.9%) reported that all the people they knew had developed a mild form of COVID-19 when they were infected, while 27.4% of them believe that COVID-19 infection is not serious, and the vaccination is not necessary. In an international cross-sectional survey, a correlation between caregivers’ perceptions of COVID-19 risk and their willingness to vaccinate their children was observed, as 31% of caregivers who were unwilling to vaccinate their children believed they were not at risk of contracting COVID-19.Citation21 Although pediatric cases are generally less severe than adult cases, a rare severe complication of multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C) has recently been described.Citation27 Children who have preexisting medical conditions may be at higher risk of developing severe illness or requiring hospitalization, as seen in adults.Citation27 Furthermore, children may play a role in transmitting the infection, which could undermine the efforts to control the outbreak.Citation25,Citation28 Therefore, raising caregiver’s awareness regarding the severity and susceptibility of COVID-19 disease and the protective role of vaccination against the infection might be warranted and may increase the uptake of the vaccine in the future.

In the regression analysis model used to identify predictors of vaccine acceptance, we found that parents of five or more children were less likely to accept the COVID-19 vaccination for their children. This is consistent with the findings of a study conducted in England, which found that parents with more than four children were around four times (OR 4.13; 95%CI: 1.873–9.104) more likely to reject the vaccination for their children than those with only one child.Citation16 In contrast, this factor was found to be non-significant in a study conducted in Turkey.Citation17 The other demographic characteristics, on the other hand, did not show any statistical significance in terms of vaccination acceptance in the current study.

Regarding the influenza vaccine uptake during the pandemic, the current study found that only 23.9% of the parents were willing to vaccinate their children. A higher percentage 52.4% was expressed by parents in China.Citation12 An international study reported that 31.9% of children received the influenza vaccine in the last year, which was a predictor factor for parents’ willingness to vaccinate their children against COVID-19 (OR: 1.49; 95%CI: 1.09–2.05).Citation21 On the other hand, a high percentage 76.8% of influenza vaccine acceptance has been reported among parents in Saudi Arabia before the pandemic.Citation29 In Saudi Arabia, 38.2% and 37.6% of children received the seasonal influenza vaccine before the pandemic.Citation29,Citation30 These findings underline that the uptake of COVID-19 vaccines for children in Saudi Arabia needs more attention. In this study, parents’ main concerns revolved around the safety and efficacy of a rushed and new COVID-19 vaccine. To address these fears, we recommend better communication and transparency from a trusted governmental agency about how COVID-19 vaccines are created and tested, as well as safety and efficacy data. In addition, due to the existing gap between acceptability and actual actions, extensive health promotion and public awareness are required to achieve high vaccine coverage among children.Citation31

5. Limitations

This study has some limitations. First, it was cross-sectional in study design, and participants were asked to complete an online questionnaire. A self-administered questionnaire through an online platform could be biased. However, owing to the current epidemic, everyone is using virtual meetings, social networking, and online platforms. As a result, we assume that we still targeted a well-representative sample. Second, the study was anonymous and did not gather participants’ personal information. Third, the sample size was small, so the study’s results may have limited generalizability. Future studies in different regions in Saudi Arabia on the current topic are recommended.

6. Conclusion

In conclusion, our study suggests that an appropriate proportion of parents are willing to vaccinate their children if a vaccine becomes available in Saudi Arabia. Nevertheless, given the significant association between vaccine hesitancy and the concerns about vaccine safety and efficacy that was identified in this study and previous studies, effort must be made to gain public trust in the vaccination and the healthcare system, and to raise public awareness regarding the possible severity and susceptibility of COVID-19 disease.

Authors contributions

Conceptualization, Mohammed Samannodi; Data curation, Mohammed Samannodi, Renan Alabbasi, Nouf Alsahaf and Rawan Alosaimy; Formal analysis, Abdallah Y Naser; Investigation, Mohammed Samannodi and Hassan Alwafi; Methodology, Mohammed Samannodi and Hassan Alwafi; Project administration, Mohammed Samannodi; Resources, Mohammed Samannodi and Hassan Alwafi; Supervision, Mohammed Samannodi and Hassan Alwafi; Validation, Mohammed Samannodi and Hassan Alwafi; Writing original draft, Mohammed Samannodi, Renan Alabbasi, Nouf Alsahaf, Rawan Alosaimy and Hassan Alwafi; Writing – review & editing, Mohammed Samannodi, Abdallah Y Naser, Renan Alabbasi, Nouf Alsahaf, Rawan Alosaimy, Faisal Minsahwi, Mohammad Almatrafi, Rami Khalifa, Rakan Ekram, Emad Salawati and Hassan Alwafi.

Informed consent statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Institutional review board statement

This study was approved by the faculty of Medicine at University of Umm Alqura, Mecca, Saudi Arabia, (NO. HAPO-02-K-012-2021-06-695).

Supplemental Material

Download ()Data availability statement

Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Supplemental data

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed on the publisher’s website at https://doi.org/10.1080/21645515.2021.2004054.

Additional information

Funding

References

- WHO. COVID-19 dashboard. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2020. https://covid19.who.int/.

- Wilson E, Girotto J, Passerrello N, Stoffella S, Shah D, Wu A, Legaspi J, Weilnau J, Meyers R, Cash J. Importance of pediatric studies in SARS-CoV-2 vaccine development. J Pediatr Pharmacol Ther. 2021;26(4):418–21.

- Alyami MH, Naser AY, Orabi MAA, Alwafi H, Alyami HS. Epidemiology of COVID-19 in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia: an ecological study. Front Public Health. 2020;8:506. doi:10.3389/fpubh.2020.00506.

- Naser AY, Dahmash EZ, Alsairafi ZK, Alwafi H, Alyami H, Jalal Z, Al Rajeh AM, Paudyal V, Alhartani YJ, Turkistani FM, et al. Knowledge and practices during the COVID-19 outbreak in the middle east: a cross-sectional study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(9):9. doi:10.3390/ijerph18094699.

- Shabrawishi M, Al-Gethamy MM, Naser AY, Ghazawi MA, Alsharif GF, Obaid EF, Melebari HA, Alamri DM, Brinji AS, Al Jehani FH, et al. Clinical, radiological and therapeutic characteristics of patients with COVID-19 in Saudi Arabia. PLoS One. 2020;15(8):e0237130. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0237130.

- Shabrawishi MH, Naser AY, Alwafi H, Aldobyany AM, Touman AA. Negative nasopharyngeal SARS-CoV-2 PCR conversion in response to different therapeutic interventions. medRxiv. 2020:2020.2005.2008.20095679.

- Alwafi H, Naser AY, Qanash S, Brinji AS, Ghazawi MA, Alotaibi B, Alghamdi A, Alrhmani A, Fatehaldin R, Alelyani A, et al. Predictors of length of hospital stay, mortality, and outcomes among hospitalised COVID-19 patients in Saudi Arabia: a cross-sectional study. J Multidiscip Healthc. 2021;14:839–52. doi:10.2147/JMDH.S304788.

- Badr OI, Alwafi H, Elrefaey WA, Naser AY, Shabrawishi M, Alsairafi Z, Alsaleh FM. Incidence and outcomes of pulmonary embolism among hospitalized COVID-19 patients. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(14):14. doi:10.3390/ijerph18147645.

- Kamidani S, Rostad CA, Anderson EJ. COVID-19 vaccine development: a pediatric perspective. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2021;33(1):144–51. doi:10.1097/MOP.0000000000000978.

- Yang Y, Peng F, Wang R, Guan K, Jiang T, Xu G, Sun J, Chang C. The deadly coronaviruses: the 2003 SARS pandemic and the 2020 novel coronavirus epidemic in China. J Autoimmun. 2020;109:102434–102434. doi:10.1016/j.jaut.2020.102434.

- Rappuoli R, Santoni A, Mantovani A. Vaccines: an achievement of civilization, a human right, our health insurance for the future. J Exp Med. 2019;216(1):7–9. doi:10.1084/jem.20182160.

- Wang Q, Xiu S, Zhao S, Wang J, Han Y, Dong S, Huang J, Cui T, Yang L, Shi N, et al. Vaccine hesitancy: COVID-19 and influenza vaccine willingness among parents in Wuxi, China—a cross-sectional study. Vaccines (Basel). 2021;9(4):342. doi:10.3390/vaccines9040342.

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Coronavirus (COVID-19) update: FDA authorizes Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine for emergency use in adolescents in another important action in fight against pandemic. 2021. https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/coronavirus-covid-19-update-fda-authorizes-pfizer-biontech-covid-19-vaccine-emergency-use.

- Ministry of Health, Saudi Arabia. COVID-19 vaccine FAQs. 2021. https://articlesen.covid19awareness.sa/COVID-19-Vaccine-FAQs.

- Brandstetter S, Böhmer MM, Pawellek M, Seelbach-Göbel B, Melter M, Kabesch M, Apfelbacher C, Ambrosch A, Arndt P, Baessler A, et al. Parents’ intention to get vaccinated and to have their child vaccinated against COVID-19: cross-sectional analyses using data from the KUNO-kids health study. Eur J Pediatr. 2021;180(11):3405–10. doi:10.1007/s00431-021-04094-z.

- Bell S, Clarke R, Mounier-Jack S, Walker JL, Paterson P. Parents’ and guardians’ views on the acceptability of a future COVID-19 vaccine: a multi-methods study in England. Vaccine. 2020;38(49):7789–98. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2020.10.027.

- Yılmaz M, and Sahin MK. Parents’ willingness and attitudes concerning the COVID-19 vaccine: a cross-sectional study. Int J Clin Pract 75 (9) . 2021;e14364.

- Zhang KC, Fang Y, Cao H, Chen H, Hu T, Chen YQ, Zhou X, Wang Z. Parental acceptability of COVID-19 vaccination for children under the age of 18 years: cross-sectional online survey. JMIR Pediat Parent. 2020;3(2):e24827. doi:10.2196/24827.

- Almaghaslah D, Alsayari A, Kandasamy G, Vasudevan R. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy among young adults in Saudi Arabia: a cross-sectional web-based study. Vaccines (Basel). 2021;9(4):330. doi:10.3390/vaccines9040330.

- Naing NN. Determination of sample size. Malays J Med Sci. 2003;10:84–86.

- Goldman RD, Yan TD, Seiler M, Parra Cotanda C, Brown JC, Klein EJ, Hoeffe J, Gelernter R, Hall JE, Davis AL, et al. Caregiver willingness to vaccinate their children against COVID-19: cross sectional survey. Vaccine. 2020;38(48):7668–73. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2020.09.084.

- Thunstrom L, Ashworth M, Finnoff D, Newbold S. Hesitancy towards a COVID-19 vaccine and prospects for herd immunity. SSRN Electron J. 2020. doi:10.2139/ssrn.3593098.

- Khubchandani J, Sharma S, Price JH, Wiblishauser MJ, Sharma M, Webb FJ. COVID-19 vaccination hesitancy in the United States: a rapid national assessment. J Community Health. 2021;46(2):270–77. doi:10.1007/s10900-020-00958-x.

- Wang C, Han B, Zhao T, Liu H, Liu B, Chen L, Xie M, Liu J, Zheng H, Zhang S, et al. Vaccination willingness, vaccine hesitancy, and estimated coverage at the first round of COVID-19 vaccination in China: a national cross-sectional study. Vaccine. 2021;39(21):2833–42. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2021.04.020.

- Anderson EJ, Campbell JD, Creech CB, Frenck R, Kamidani S, Munoz FM, Nachman S, Spearman P. Warp speed for coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) vaccines: why are children stuck in neutral? Clin Infect Dis. 2021;73(2):336–40. doi:10.1093/cid/ciaa1425.

- Patrick SW, Henkhaus LE, Zickafoose JS, Lovell K, Halvorson A, Loch S, Letterie M, Davis MM. Well-being of parents and children during the COVID-19 pandemic: a national survey. Pediatrics. 2020;146(4):e2020016824. doi:10.1542/peds.2020-016824.

- Jiang L, Tang K, Levin M, Irfan O, Morris SK, Wilson K, Klein JD, Bhutta ZA. COVID-19 and multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children and adolescents. Lancet Infect Dis. 2020;20(11):e276–e288. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30651-4.

- Lopez AS, Hill M, Antezano J, Vilven D, Rutner T, Bogdanow L, Claflin C, Kracalik IT, Fields VL, Dunn A, et al. Transmission dynamics of COVID-19 outbreaks associated with child care facilities — Salt Lake City, Utah, April–July 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69(37):1319–23. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm6937e3.

- Hamadah R, Hussain A, Alsoghayer N, Alkhenizan Z, Alajlan H, Alkhenizan A. Attitude of parents towards seasonal influenza vaccination for children in Saudi Arabia. Fam Med Prim Care. 2021;10(2):904–09. doi:10.4103/jfmpc.jfmpc_1602_20.

- Alolayan A, Almotairi B, Alshammari S, Alhearri M, Alsuhaibani M. Seasonal influenza vaccination among Saudi children: parental barriers and willingness to vaccinate their children. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16(21):4226. doi:10.3390/ijerph16214226.

- McEachan RRC, Conner M, Taylor NJ, Lawton RJ. Prospective prediction of health-related behaviours with the theory of planned behaviour: a meta-analysis. Health Psychol Rev. 2011;5(2):97–144. doi:10.1080/17437199.2010.521684.