ABSTRACT

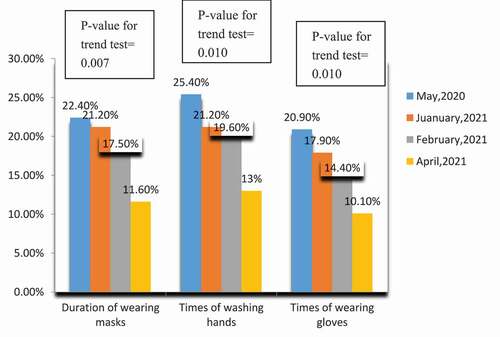

This study is conducted to explore the association between health behaviors and the COVID-19 vaccination based on the risk compensation concept among health-care workers in Taizhou, China. We conducted a self-administered online survey to estimate the health behaviors among the staff in a tertiary hospital in Taizhou, China, from May 18 to 21 May 2021. A total of 592 out of 660 subjects (89.7%) responded to the questionnaire after receiving an e-poster on WeChat. Subjects who had been inoculated with the COVID-19 vaccine were asked to mention the differences in their health behaviors before and after the vaccination. The results showed that there were no statistical differences in health behaviors between vaccinated and unvaccinated groups, except in terms of the type of gloves they used (62.8% in the vaccinated group and 49.2% in the unvaccinated group, p = .048). Subjects who received earlier COVID-19 vaccinations exhibited better health behaviors (22.40% increased for duration of wearing masks (P = .007), 25.40% increased for times of washing hands (P = .01), and 20.90% increased for times of wearing gloves (P = .01)). Subjects also revealed better health behaviors (washing hands, wearing gloves, and wearing masks) after vaccination compared to that before. In conclusion, concept of risk compensation was not applied in our findings. The health behaviors did not reduce after the COVID-19 vaccination, which even may improve health behaviors among health-care workers in the hospital setting.

KEYWORDS:

Introduction

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) broke out at the end of 2019. Subsequently, the novel severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) was identified as the causative agent by researchers.Citation1 The virus spread in China and across the world,Citation1 and, on 11 March 2020, the World Health Organization declared COVID-19 a pandemic. It has caused more than 3.46 million deaths as of 23 May 2021 and extensive damage and destruction to the society and daily life. Regretfully, there are few special antiviral treatments for COVID-19.Citation2,Citation3

Vaccines have been proved to be an extremely effective means to deal with epidemics in the past.Citation4 COVID-19 vaccines have been producing at an amazing rate globally in an effort to deal with the pandemic.Citation2 Countries around the world are at full steam, accelerating research and development of COVID-19 vaccines; there have been over 160 vaccine candidates to date, with approximately 20 in clinical evaluation.Citation2 In China, at least five different COVID-19 vaccines across three platforms have been conditionally approved for emergency use.Citation5 A global survey revealed that 54.85–88.62% of respondents were willing to accept the COVID-19 vaccine.Citation6

Health behaviors, such as washing hands and wearing face masks and gloves, are of great importance in combating COVID-19. Wearing face masks in public is one of the key measures to control the spread of COVID-19.Citation7 The use of face masks has also been associated with a reduction in the risk of COVID-19 infection.Citation7 Healthcare workers are encouraged by the WHO to wear gloves when engaged in the direct care of patients and even to wear double gloves when dealing with COVID-19 patients’ airways, urine, blood, and other body fluids, for as long as the pandemic continues.Citation8 Touching contaminated surfaces followed by a hand-to-face transfer has been confirmed as a potential infection route.Citation9 Because humans involuntarily touch their faces more than 20 times per hour, thus washing hands with soap and water is recommended to prevent this transmission.Citation9

Risk compensation – which occurs when people adjust their behaviors based on diminished perceived susceptibility resulting from participation in some preventive intervention – creates a subsequent increase in risk behaviors.Citation10,Citation11 Some direct associations between risk compensation and vaccines exist. For example, a decrease in condom use after Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) vaccinationCitation12 and an increase in risky sexual behaviors after human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccinations have been reported.Citation13 The risk compensation theory suggests that healthcare workers may engage in fewer health behaviors after receiving the COVID-19 vaccination, however, this is supported by empirical evidence. Therefore, we conducted a questionnaire survey to address this topic and assess the situation among healthcare workers in China.

Materials and methods

Study design and population

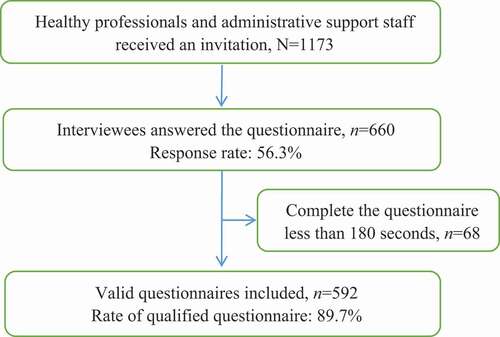

We conducted an anonymous cross-sectional survey online via the WeChat-incorporated Wen-Juan – Xing platform (Changsha Ranxing information Technology Co., Ltd., Hunan, China), the largest online survey platform in China, and provided freely to all customers.Citation5 The medical staff who worked in tertiary hospital in Taizhou, China, were our target population. As shown , a total of 1,173 healthy professionals (doctors, nurses, pharmacists and medical technicians) and administrative support staff (janitors, nursing aides and dietary aides) were notified to report their health behaviors via WeChat. Additionally, 660 interviewees volunteered to answer the self-administered questionnaire between 18 and 21 May 2021. The response rate was 56.3%. Of these volunteers, 68 were excluded because of inadequate time (less than 180 seconds) to complete the questionnaire. Finally, 592 questionnaires with valid data were included in this study (response rate: 89.7%, 592/660). We investigated the subjects gender, knowledge, category of employment, and health behaviors such as wearing masks, wearing gloves, and washing hands. Their experiences with negative emotions (anxiety, panic, and fear) of were also noted. Subjects who had been inoculated with the COVID-19 vaccine were asked to mention the differences in their health behaviors before and after the vaccination. This survey was exempted from informed consent and approved by the Ethics Committee of Enze Hospital of Zhejiang province (approval number:K20210501) in China. Participants was anonymized. The COVID-19 vaccine in this study was inactive and manufactured by Sinovac.The Chinese government provided the COVID-19 vaccine freely to healthcare workers.

Questionnaires

We consulted experts at the infection-control department in the study hospital regarding the protective health behaviors of the hospital staff during the COVID-19 pandemic in order to create and conduct a self-administered questionnaire. The questionnaire comprised the following items related to:

Basic demographic information including gender, education, and professional/technical title

Health behaviors followed as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic, as assessed by the questions: ‘What is the situation about wearing masks, gloves and washing hands?’

COVID-19 vaccination status, as assessed by the questions: ‘Did you get the COVID-19 vaccination?’ and ‘If you did, when did you get it? ‘

Comparison of health behaviors among vaccinated protections before and after receiving the COVID-19 vaccination in terms of wearing masks, wearing gloves and washing hands

Experience of negative emotions (anxiety, panic and fear) as a result of the prevalence of COVID-19.

Statistical analysis

All data were analyzed using IBM SPSS statistics 22.0 software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).In the univariate analysis, the χ2-test was used to assess categorical variables between subjects with and without fatigue. The primary outcome of this survey was the adherence to health behaviors following the outbreak of COVID-19 pandemic and the difference of health behaviors among vaccinated protections before and after the vaccination. All respondents provided answers the regard to the health behaviors they followed and almost answered whether they had received the vaccine. Follow-up questions, such as the time of receiving the first dose of the vaccine were answered by responders the vaccinated participants. A p-value of <0.05 was considered to represent a statistically significant difference among the test population.

Results

Characteristics of the study population

A total of 592 hospital staff completed the questionnaire. The sample comprised 87 men (14.7%) and 505 women (85.3). All of them reported their health behaviors and negative emotions after the outbreak of COVID-19. Among all the staff, 522 (88.2%) received at least one dose of the COVID-19 vaccine, 59 were unvaccinated, and 11 participants did not report whether they had received the COVID-19 vaccine for unknown reasons. Excluding these 11 participants, the demographic variables of the remaining participants’ education level, professional title, position, and years of service are described in .

Table 1. Baseline characteristics of subjects

Behaviors of healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic

In our survey, we investigated the different health behaviors of vaccinated and unvaccinated respondents. indicates that the type of gloves used was associated with being vaccinated, although other health behaviors showed no association.

Table 2. Behaviors of healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic

Differences in health behaviors among vaccinated healthcare workers

As shown in , based on time of the first vaccination, the increase in the duration of wearing masks, frequency of washing hands, and frequency of wearing gloves after vaccination was significantly different. By comparing health behaviors in pre- and post-vaccination, we found an obvious increase in the duration of wearing masks, frequency of washing hands, and frequency of wearing gloves among our sample ().

Experience of negative emotions (anxiety, panic, and fear) during COVID-19

Our survey data indicate that 61.15% of the participants never experienced negative emotions, while there was a reduction in the negative emotions among only 6.52% of the participants after the COVID-19 vaccination. These results are described in .

Table 3. Experience of negative emotions (anxiety, panic, and fear) during working hours related with COVID-19 prevalence and vaccine inoculation

Discussion

Clinical implications

To our knowledge, this is the first study to investigate the relationship between COVID-19 vaccine and health behaviors. Our study may provide population-based empirical data on this relationship.

Risk compensation, in which individuals respond to safety measures with a compensatory increase in risky behaviors, is named the “Peltzman Effect” after University of Chicago economist Sam Peltzman who first described it in 1975.Citation14 A comprehensive review of the Peltzman Effect identified four main factors – visibility, motivation, control, and effectiveness – as likely contributors to risk compensation, all of which appear to be present in the COVID-19 pandemic.Citation14 Four interventions are believed to lead to risk compensation – wearing of bike or ski helmets (purportedly leading to riskier cycling or skiing), circumcision to prevent HIV infection, HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis, and HPV vaccination (all purportedly leading to increased unprotected sexual activity).Citation15 One of the most alarming features of the Peltzman Effect is that there may exist a bystander component, which suggests that, even those who have not received the COVID-19 vaccine may stop wearing masks and social distancing if they aware that others have received the vaccine.Citation14

Preventive HIV vaccines have the potential to curtail the HIV epidemic. As the first HIV vaccines on the market may only be effective to a limited extent, risk compensation could severely weaken and even offset the vaccine’s public health benefit.Citation11 In fact, some studies have reported that a combination of frequent risk compensation and low vaccine effectiveness by an HIV vaccine campaign could actually increase the incidence of HIV.Citation11 In addition, risk compensation has been employed in a sensationalistic manner to stop HIV vaccine development, similar to the misleading arguments leveled against the introduction of other preventive and safety interventions that have since rescued millions of lives, ranging from seatbelt regulations and speed limits to condoms.Citation16 Some parents worry that their children may be more likely to engage in sex, or experience unprotected sex, if inoculated against the sexually transmitted HPV, which could cause cervical cancer.Citation17 This worry could be one of the reasons why the efficacious HPV vaccine has a lower uptake compared to many other vaccines, and despite being provided free of charge in organized childhood vaccination programmes.Citation17

No evidence for an increase in any outcome deemed to reflect risk compensation has been provided by the most recent systematic reviews for any intervention.Citation15 In studies, when participants are asked about their personal likelihood of risk compensation, they anticipate fewer behavioral change.Citation11 Risk compensation exerted no prominent impact on young women in terms of engaging in sexual activity or refraining from using condoms after being inoculation with HPV vaccine.Citation18 Moreover, no association was discovered between the HPV vaccination and risky sexual behaviors.Citation19

We summarized the relationship between risk compensation and vaccines in different populations, as presented in . Not all the results indicated that the average tendency was to agree with the risk compensation statements. This study revealed that healthcare workers do not necessarily engage in fewer non-pharmacological interventions, such as washing hands, wearing masks, and wearing gloves, after receiving the COVID-19 vaccination. More importantly, our study indicates that healthcare workers who had been vaccinated early enhanced and practiced better after the inoculation. However, we still do not understand whether actual risk compensation behaviors will occur following COVID-19 vaccination in terms of reduced disease prevention efforts. This needs to be further considered in less hypothetical studies as more and more people get vaccinated.

Table 4. Determing whether a relationship exists between risk compensation and vaccine in different studies

Methodological considerations

Our survey comprises some limitations. First, accurate information cannot be guaranteed by self-administrated online questionnaires. However, we conducted a logic data check and called back to revise any non-logical data. Second, affected by the current prevalence of the COVID-19, the implementation of non-pharmacological interventions may be overestimated. The respondents were asked to recall their behaviors prior to COVID-19, which may have resulted in inaccurate information. A low response rate in this study is another drawback. However, we still had sufficient statistical power to evaluate the health behaviors before and after vaccination (power = 85%, α = 0.05). In addition, the survey respondents were likely to be younger and healthier than the general population, which could have resulted in selection bias.

Conclusions

In conclusion, concept of the risk compensation was not applied in our findings. The health behaviors did not reduce after the COVID-19 vaccination, which even may improve health behaviors among healthcare workers in the hospital setting. Further large-scale population-based investigations are needed to identify the application of risk compensation theory for the association between health behaviors and the COVID-19 vaccination.

Author contributions

LS, MY, and LM conceived the study. LC, MY, LS, and JZ collected the data. LS was responsible for the coding of the analyses. LS, TT, and MZ analysed and interpreted the data. LS wrote the first draft of the paper and interpreted the relevant literature. TT edited and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgments

We thank the participants for their cooperation and support.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Lin HJ, Guo CC, Hu YF, Liang HB, Shen WW, Mao WH, He N. COVID-19 control strategies in Taizhou city, China. Bull World Health Organ. 2020;98:632–7. doi:10.2471/BLT.20.255778.

- Wang JH, Jing RZ, Lai XZ, Zhang HJ, Lyu Y, Knoll MD, Fang H. Acceptance of COVID-19 vaccination during the COVID-19 pandemic in China. Vaccines. 2020;8:482. doi:10.3390/vaccines8030482.

- Huang C, Wang Y, Li X, Ren LL, Zhao JP, Hu Y, Zhang L, Fan GH, Xu JY, Gu XY, et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet. 2020;395:497–506. doi:10.1016/j.virusres.2020.198043.

- Wadman M, You J. The vaccine wars. Science. 2017;356:364–65. doi:10.1126/science.356.6336.364.

- Zhang MX, Zhang TT, Shi GF, Cheng FM, Zheng YM, Tung TH, Chen HX. Safety of an inactivate SARS-COV-2 vaccine among healthcare workers in China. Expert Rev Vaccines. 2021;20:891–98. doi:10.1186/s13063-020-04775-4.Trials.

- Wang Q, Xiu SX, Zhao SY, Wang JL, Han Y, Dong SH, Huang JX, Cui TT, Yang LQ, Shi NY, et al. Vaccine hesitancy: COVID-19 and influenza vaccine willingness among parents in Wuxi, China—a cross-sectional study. Vaccines. 2021;9:342. doi:10.3390/vaccines9040342.

- Ogoina D. Improving appropriate use of medical masks for COVID-19 prevention: the role of face mask containers. Am Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2020;103:965–66. doi:10.4269/ajtmh.20-0886.

- Tabary M, Araghi F, Nasiri S, Dadkhahfar S. Dealing with skin reactions to gloves during the COVID-19 pandemic. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2020;42(2):247–48. doi:10.1017/ice.2020.212.

- Przekwas A, Chen ZJ. Washing hands and the face may reduce COVID-19 infection. Med Hypotheses. 2020;144:110261. doi:10.1016/j.mehy.2020.110261.

- Adams J, Hillman M. The risk compensation theory and bicycle helmets. Inj Prev. 2001;7:89–90. discussion 90. doi:10.1136/ip.7.4.343.

- Young AM, Halgin DS, DiClemente RJ, Sterk CE, Havens JR. Will HIV vaccination reshape HIV risk behavior networks? A social network analysis of drug users’ anticipated risk compensation. PLoS One. 2014;9(101047):e101047. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0101047.

- Newman PA, Lee SJ, Duan NH, Rudy E, Nakazona TK, Boscardin J, Kakinami L, Shoptaw S, Diamant A, Cunningham WE. Preventive HIV vaccine acceptability and behavioral risk Compensation among a random sample of high-RiskAdults in Los Angeles (LA VOICES). Health Serv Res. 2009;44:2167–79. doi:10.1111/j.1475-6773.2009.01039.x.

- Marlow LA, Forster AS, Wardle J, Waller J. Mothers’ and adolescents’ beliefs about risk compensation following HPV vaccination. J Adolesc Health. 2009;44:446–51. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2008.09.011.

- Trogen B, Caplan A. Risk compensation and COVID-19 vaccines. Ann Intern Med. 2021;174:858–59. PMID:33646837. doi:10.7326/M20-8251.

- Mantzari E, Rubin GJ, Marteau TM. Is risk compensation threatening public health in the covid-19 pandemic? BMJ. 2020;370:m2913. doi:10.1136/bmj.m2913.

- Newman PA, Roungprakhon S, Tepjan S, Yim S. Preventive HIV vaccine acceptability and behavioral risk compensation among high-risk men who have sex with men and transgenders in Thailand. Vaccine. 2010;28:958–64. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2009.10.142.

- Hansen BT. No evidence that HPV vaccination leads to sexual risk compensation. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2016;12:1451–53. doi:10.1080/21645515.2016.1158367.

- Frio GS, França MTA. Human papillomavirus vaccine and risky sexual behavior: regression discontinuity design evidence from Brazil. Econ Hum Biol. 2021;40:100946. doi:10.1016/j.ehb.2020.100946.

- Liddon NC, Leichliter JS, Markowitz LE. Human papillomavirus vaccine and sexual behavior among adolescent and young women. Am J Prev Med. 2012;42:44–52. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2011.09.024.

- Wu T, Qu SY, Fang Y, Ip M, Wang ZX. Behavioral intention to performrisk compensation behaviors after receiving HPVvaccination among men who have sex with men inChina. Human Vaccine Immunother. 2019;15:1737–44. doi:10.1080/21645515.2019.1622975.

- Painter JE, DiClemente RJ, Jimenez L, Stuart T, Sales JM, Mulligan MJ. Exploring evidence for behavioral risk compensation among participants in an HIV vaccine clinical trial. Vaccine. 2017;35:3558–63. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2017.05.024.

- Brewer NT, Cuite CL, Herrington JE, Weinstein ND. Risk compensation and vaccination: can getting vaccinated cause People to engage in risky behaviors? Ann Behav Med. 2007;34:95–99. doi:10.1007/BF02879925.

- Painter JE, Temple BS, Woods LA, Cwiak C, Haddad LB, Mulligan MJ, DiClemente RJ. Theory-based analysis of interest in anHIV vaccine for reasons indicative of risk compensation among African American women. Health Educ Behav. 2018;45:444–53. doi:10.1177/1090198117736860.

- Leidner AJ, Chesson HW, Talih M. HPV vaccine status and sexual behavior among young sexually-active women in the US: evidence from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2007–2014. Health Econ Policy Law. 2020;15:477–95. doi:10.1017/S1744133119000136.