ABSTRACT

Given the high level of exposure to SARS-CoV-2, cold-chain workers are considered priority vaccination groups. To date, many studies have reported on the willingness within distinct populations to be vaccinated against COVID-19, whereas it has not been reported among cold-chain workers worldwide. To address this void, we conducted a cross-sectional survey to gather general information, COVID-19-related knowledge, attitudes, and practices (KAP), and willingness to receive a COVID-19 vaccine among cold-chain workers in Shenzhen, China. Binary logistic analyses were conducted to explore the associations between COVID-19-related KAP factors and the willingness for COVID-19 vaccination. Among 244 cold-chain workers, 76% indicated that they were willing to be vaccinated. Knowledge about SARS-CoV-2, comprehending the most effective prevention, understanding the transmission routes, and recognizing the priority vaccination groups were positively associated with willingness to be vaccinated against COVID-19. Regarding attitude factors, perceiving the social harmfulness and severity of COVID-19 were related to a higher willingness to vaccination. Participants considering themselves a priority group for COVID-19 vaccination were more likely to get vaccinated. For practice factors, attaining more knowledge and higher self-reported compliance with maintaining adequate ventilation were also positively associated with the dependent variable. Agreement on the importance of COVID-19 vaccination was the most frequent reason for accepting the COVID-19 vaccine; additionally, concerns about side effects and insufficient understanding of efficacy were the main factors contributing to vaccine refusal. Enhancing KAP levels related to COVID-19 helps promote vaccine acceptance. Health authorities should promptly implement educational activities following the updated vaccine status among cold-chain workers.

Introduction

The epidemic of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) has been increasing worldwide since December 2019.Citation1 Given a lack of specific antiviral treatments for COVID-19, efficacious vaccination is an urgent need to end the COVID-19 pandemic.Citation2 At present, significant progress has been made globally for the development of COVID-19 vaccines utilizing various technologies and producing hundreds of vaccine candidates ranging from traditional inactivated vaccines and recombinant DNA vaccines as well as mRNA vaccines.Citation2,Citation3,Citation4 Several reports concerning the large phase-3 COVID-19 vaccine trials in humans were made public at the beginning of November 2020.Citation2,Citation3,Citation4 In China, five COVID-19 vaccines have been conditionally approved for market authorization or granted emergency use authorization by the National Medical Products Administration (NMPA).Citation5 These include three inactivated COVID-19 vaccines manufactured by the Beijing Institute, Wuhan Institute, and Sinovac; one adenovirus-5 vectored COVID-19 vaccine developed by CanSinoBIO; and one recombinant subunit COVID-19 vaccine produced by Anhui Zhifei.Citation5 According to the National Health Commission of the People’s Republic of China, cost-free vaccination for COVID-19 has been available for emergency use since 22 July 2020 among high-risk groups such as healthcare workers and personnel working in epidemic prevention. Subsequently, the COVID-19 vaccine was scheduled for the general Chinese population. As of 5 March 2022, over three billion doses of vaccine have been received in China, and greater than ten billion doses have been administered globally.Citation6,Citation7

As a novel emerging infectious disease, understanding the common barriers for COVID-19 vaccination willingness and addressing vaccine hesitancy represent critical points to maximize vaccination rates.Citation8,Citation9 To date, studies on COVID-19 vaccination acceptance have already been published in some countries among different populations. As an illustration, prior studies focused on the acceptance and use of a vaccine against the 2009 H1N1 pandemic showed the willingness to accept the 2009 H1N1 vaccination was 67% in the Australian public but only 17% among healthcare workers in Greece.Citation10,Citation11 A systematic review indicated that COVID-19 vaccine acceptance rates in 33 different countries ranged from 24% to 97% among the general population.Citation12 Consequently, reports on acceptance of the COVID-19 vaccine are warranted to clarify in vaccination willingness in various countries, regions, and populations.

It is commonly recognized that better knowledge, attitudes, and practices (KAP) among the public are critical to guarantee success in the battle against pandemics.Citation13,Citation14 Heightening the public’s consciousness about the seriousness of the disease benefits their willingness to be vaccinated.Citation15 A population-based investigation in Hong Kong reported that perceived severity, perceived benefits of the vaccine, and more cues to action were positive correlates of vaccine acceptance.Citation16 From a previous study of Chinese adults, Rugang and colleagues found that the COVID-19 vaccination willingness rate of people with a high awareness level of vaccine effectiveness was higher than the low-awareness group.Citation17 Likewise, prior research illustrated that the perceived risk of COVID-19 was a significant predictor of vaccination intention among 1144 Middle Eastern participants.Citation15 Furthermore, our previous study indicated that participants who had better knowledge about pneumonia were more willing to receive the pneumococcal vaccine than those with a lesser degree of knowledge.Citation18 Numerous studies have been published focused on COVID-19-related KAP and the willingness to be vaccinated within different populations worldwide, especially for high-risk groups such as healthcare workers.Citation14–Citation19–23

Sporadic and localized outbreaks still have occurred following sufficient measures against COVID-19 transmission. In July 2020, a COVID-19 outbreak occurred in Dalian, China. Based on epidemiological investigations, laboratory testing, and genome sequencing, the Dalian COVID-19 outbreak resulted from COVID-19 contaminated imported cold-chain seafood products. This report suggested that SARS-CoV-2 could be transmitted via cold-chain products.Citation24 Later on 4 September 2020, two Chinese stevedores were reported as being SARS-CoV-2 positive during a routine nucleotide acid test, and an epidemiological investigation was then carried out to identify the source of infection. The results showed that 50 out of 421 surface samples of a frozen cod outer package tested positive for SARS-CoV-2.Citation25 In the case of COVID-19 detected in a cargo worker at Shanghai Pudong Airport on 8 November 2020, the initial suspicion was transmission by materials rather than person to person because of the lack of an apparent transmission chain.Citation26 Saitin and Viroj have also summarized evidence on pathogen contamination in food, indicating the necessity of appropriate recommendations for contamination prevention.Citation27 Even though the likelihood of transmission on frozen food is lower than other transmission routes, researchers believed SARS-CoV-2 could be potentially transmitted on frozen surfaces.Citation28,Citation29 Hence, a number of localized COVID-19 outbreaks in different cities in China could be tracked as originating from workers at cold port storage, seafood processing facilities, and market sites associated with imported cold-chain food.Citation30–32These incidents provided accumulating evidence that workers in cold, humid, and communal locations are also at high risk for acquiring and transmitting respiratory infections.Citation29 They should therefore be regarded as a high-risk group and placed in the priority vaccination population. Even though we expected a higher willingness for COVID-19 vaccination, it could be affected since they might not be aware that they belong to one of the high-risk groups. Shenzhen, locating in the coastal area of Southern China, is one of the largest cities in China and has a number of imported cold-chain food industries. Similar to the factory and service industry employees, these workers are supposed to represent one of the most activitive population regarding social activity.

To the best of our knowledge, there are currently no relevant studies investigating willingness toward COVID-19 vaccination among workers who have frequent contact with imported cold-chain food (we called cold-chain workers for this study). To address this lack, we conducted a cross-sectional investigation to survey the willingness to be vaccinated against COVID-19 among cold-chain workers and to evaluate their KAP related to COVID-19 vaccination, identifying associated factors that significantly affected their vaccination willingness. Since the COVID-19 vaccine would be scheduled for the cold-chain workers of the study site by the end of 2020, our findings could be helpful to provide evidence on facilitating health education and management and also recommendations to health authorities for future vaccination responses.

Methods

Study design, participants, and sampling

This cross-sectional investigation was conducted in Shenzhen City between 16 December 2020 and 21 December 2020, with over 20 million local populations in southern China as of 2018.Citation33

This study included all 41 market sites associated with imported cold-chain products in Longhua, an urban district of Shenzhen with similar social conditions and populations as other urban districts of the city. Eligible persons were 772 full-time employees aged over 18 years engaging in imported frozen food-related work. Following the Public Places Health Management Regulations and Implementing Rules announced by the Chinese government, such employees in food production and operations are required to undergo a physical examination annually.Citation34 It is illegal to engage in food-related work without a health certificate, as described previously.Citation34

Based on the statistical significance of 0.05 and the maximum allowable error of 7% and assuming the proportion of COVID-19 vaccine acceptance as 45%,Citation12 a minimum sample size of 206 subjects was calculated using PASS version 11.0. Considering that the non-response rate was 10% and 10% of questionnaires were invalid, 254 subjects were the target sample size. A two-stage sampling method was used to select the participants. In stage I, 50% of the market sites related to imported cold-chain products were randomly chosen as primary sample units. In stage II, all individuals among the primary units were continuously numbered (e.g., 1, 2, 3 …), and subsequently, we wrote the numbers on pieces of paper with the same shape and size. Based upon the principle of simple random sampling, 254 cold-chain workers were then selected by lottery. These individuals were invited to participate and were given a brief description of the purposes of the present survey. Only those who gave consent to be a part of the investigation were recruited as participants. Finally, a total of 244 full-time cold-chain workers who agreed to participate in the present survey completed the questionnaires, with a response rate of 96%. All questionnaires were under quality control, and none of the participants was excluded because of invalid responses.

Data collection

Ethics approval for this research was obtained from the Longhua Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) of Shenzhen. We developed the present survey via the most extensive online survey platform in China, called Wen Juan Xing (Changsha Ranxing Information Technology Co., Ltd., Hunan, China). A specific URL link to the online questionnaire was generated. Participants were asked to click the URL to complete the investigation on their mobile devices. Wen Juan Xing would check the completeness of questionnaires before submission, and thereby only the completed ones would be submitted successfully. Rewards such as an e-coupon were provided as incentives for participation through a lottery after completion.

Data were collected from a self-administered questionnaire approved by the Longhua CDC. Based on the literature review regarding the given topic, a panel consisting of three CDC researchers, a market manager, and two experts in epidemiology and infectious diseases was formed to develop the questionnaire for this investigation. CDC researchers prepared the first version of the questionnaire. Subsequently, we conducted a pretest using 10 cold-chain workers other than those included in this study to assess the accuracy and consistency. After that, the first version of the questionnaire was reviewed again and modified by CDC researchers and experts. Specifically, the items with a Cronbach’s alpha coefficient ≥0.6 were included. The final version of the questionnaire consisted of four sections covering demographic characteristics, COVID-19-related KAP, and the willingness for COVID-19 vaccination. All collected data were kept strictly confidential and only used for research purposes.

Measurements

Demographic characteristics

Participants reported their gender (male, female), age (18–30, 31–40, or >40 years), education level (high school or lower, college or above), marital status (unmarried, married, or divorced), monthly income (<CNY 10,000, CNY 10,000–30,000, or >CNY 30,000), and underlying diseases, including hypertension, heart diseases, diabetes, respiratory disease, and gastrointestinal disease (yes, no). Additionally, participants were asked for their COVID-19 history based on the question, “Have you or your family members been diagnosed with COVID-19?”

Knowledge

Five items in the knowledge section were designed according to the guideline for diagnosis and treatment of COVID-19 promulgated by the National Health Commission of the People’s Republic of China on 18 August 2020,Citation35 together with the national guideline for prevention and control of COVID-19 announced on 11 September 2020.Citation36 Of these, two items were used to evaluate knowledge about COVID-19: “COVID-19 is a respiratory infectious disease caused by SARS-CoV-2,” and “COVID-19 infection can be transmitted by respiratory droplets, aerosol, and contact with infected individuals.” The following three items were used to assess knowledge related to COVID-19 vaccine and priority vaccination groups: “COVID-19 vaccination is the most effective measure to prevent the COVID-19 infection,” “Healthcare workers, older adults, travelers from overseas, suspected cases of COVID-19, and people who had directly contacted SARS-CoV-2 are the priority vaccination populations,” and “Persons who are elderly or with underlying diseases or with weakened immunity are more vulnerable to developing COVID-19.” All response options were “Yes,” “No,” and “Unsure.” Cronbach’s alpha coefficient indicated a.71 score for this section.

Attitudes

Participants were asked four items about their attitudes toward COVID-19 and its vaccine. The first two items measured the participants’ perception of social harmfulness and severity of COVID-19: “Although the COVID-19 becomes a normalized infectious disease identical to influenza, its social harmfulness is far greater than influenza,” and “COVID-19 infection can lead to severe health and economic burdens.” Participants’ perception of the necessity for COVID-19 vaccination was measured by the item “It is necessary to get vaccinated against COVID-19.” The last item was “I consider myself in a priority group for COVID-19 vaccination.” Similar to prior studies,Citation3,Citation37 all responses were categorized by a five-point Likert scale ranging from strongly disagree to strongly agree. Agreement was defined as “agree” or “strongly agree.” Cronbach’s alpha coefficient indicated a.73 score for the attitudes section.

Practices

In the practices section, participants were asked to assess their practices to curb COVID-19 and the reasons for acceptance or refusal of vaccination. The first two items were “I am actively seeking information about COVID-19,” and “I have understood more about infectious diseases prevention and control during the COVID-19 pandemic.” The response options were “Yes,” “No,” and “Unsure.” Participants also reported whether they had the following preventive behaviors during the COVID-19 pandemic: (1) maintaining adequate ventilation indoors, (2) wearing a face mask, (3) sanitizing hands frequently, (4) doing more exercises, and (5) avoiding crowded places. Cronbach’s alpha coefficient indicated a.69 score for the practices section.

We assessed the willingness to receive a COVID-19 vaccine based on the item: “Are you willing to receive the COVID-19 vaccine?” Response options were “Yes” and “No.” The participants who chose “Yes” were assigned to the willing group and were asked to report the reasons for vaccination acceptance. The participants that answered “No” were classified into the unwilling group and were also asked to indicate the reasons for not getting vaccinated.

Statistical analyses

Questionnaire data were extracted from Wen Juan Xing and exported to a Microsoft Excel 2016 spreadsheet. Statistical analyses were performed using R statistical software v.4.0.3 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

Descriptive statistics were used for the participants’ demographic characteristics and COVID-19-related KAP. All items were closed-ended and treated as categorical variables that were summarized as frequencies and proportions. The 95% confidence interval (CI) for the overall proportion was estimated by using the exact binomial test. This study adopts qualitative analysis method. The binary variables of the willingness to get vaccinated against COVID-19 were used as the dependent variable. Both bivariate and multivariate analyses were generated. A bivariate logistic regression model first estimated the association between each KAP factor and the dependent variable, with crude odds ratios (OR) and 95% CI being calculated. Furthermore, we fit multivariable logistic regression models to assess the associations after adjustment for age, gender, education level, marital status, monthly personal income, and underlying diseases, with adjusted odds ratios (aOR) and 95% CI reported. We considered statistical tests with P < .05 statistically significant. Multicollinearity among independent variables was detected by estimating the variance inflation factor (VIF). The VIF values for each independent variable were less than 5, suggesting there was no multicollinearity.

Results

Demographic characteristics of the participants

In total, 244 cold-chain workers with complete data were involved in the present study. The demographic characteristics and their willingness to receive a COVID-19 vaccine are shown in . A large proportion of participants (76%) displayed willingness toward the COVID-19 vaccination. The proportion of men and women was 57.0:43.0, and roughly half (49%) were aged between 31 and 40. Most participants (85%) had an education level of high school or lower, whereas the group with a college or above education accounted for only 15%. The majority of participants were unmarried (79%) and had a monthly personal income of CHN <10,000 (84%). Only 3% of the participants reported an underlying disease. Also, both the participants and their family members were not diagnosed with COVID-19 in the past year.

Table 1. Demographic characteristics of participants and willingness toward COVID-19 vaccination, Shenzhen, China, December 2020.

Knowledge, attitudes, and practices toward COVID-19 and vaccination

Frequencies and percentages of KAP items associated with COVID-19 and its vaccine are described in . In terms of the knowledge section, a large number of our participants (82%) believed that COVID-19 is a respiratory disease caused by SARS-CoV-2 (χ2 = 4.698, P = .03). Of the participants, 66% agreed that COVID-19 vaccination is the most effective measure to prevent COVID-19 infection (χ2 = 6.893, P = .009), and most of them (95%) responded that COVID-19 infection could be transmitted through respiratory droplets, aerosols, and contact with infected individuals (χ2 = 13.123, P < .001). During the survey, 74% of the participants believed that the priority vaccination populations include healthcare workers, older adults, travelers from overseas, those with suspected cases of COVID-19, and people who had direct contact with COVID-19 patients (χ2 = 9.025, P = .003). Meanwhile, 84% of participants also regarded the elderly or people with underlying diseases or weakened immunity as the vulnerable group (χ2 = 3.330, P = .07) ().

Table 2. Knowledge factors associated with the willingness to receive a COVID-19 vaccine among cold-chain workers in Shenzhen, China, December 2020.

Table 3. Practice factors associated with the willingness to receive a COVID-19 vaccine among cold-chain workers in Shenzhen, China, December 2020.

Table 4. Attitude factors associated with the willingness to receive a COVID-19 vaccine among cold-chain workers in Shenzhen, China, December 2020.

For participants’ attitudes, 87% of them acknowledged that the social harmfulness of COVID-19 is far greater than that of influenza, even if it would be a normalized infectious disease (χ2 = 5.774, P = .02). A large proportion of participants (93%) responded that severe health and economic burdens could be attributed to COVID-19 infection (χ2 = 3.435, P = .06). Most participants (86%) recognized the necessity to be vaccinated against COVID-19 (χ2 = 2.895, P = .09), and 87% regarded themselves as a priority group for COVID-19 vaccination (χ2 = 6.467, P = .01) ().

In regard to COVID-19-related practices, a large majority of participants (92%) were actively searching for information about COVID-19 (χ2 = 2.804, P = .09), and 87% of them indicated that they had obtained greater understanding of infectious disease prevention and control during this outbreak (χ2 = 6.467, P = .01). In this survey, most of the participants reported preventing COVID-19 infection by wearing a mask outside (97%, P = .67), followed by sanitizing hands frequently (95%, χ2 = 0.203, P = .65), maintaining adequate ventilation (87%, χ2 = 5.774, P = .02), avoiding crowded areas (85%, χ2 = 3.549, P = .06), and doing more exercises (70%, χ2 = 1.245, P = .27) ().

Factors associated with the willingness to receive a COVID-19 vaccine

Using willingness to get vaccinated as the primary outcome, we conducted bivariate and multivariate logistic regression analyses to identify the significant KAP factors. The findings of bivariate analyses are shown in Multimedia Supplementary Appendix. After adjusting for demographic characteristics, participants who agreed that COVID-19 is a respiratory disease caused by SARS-CoV-2 were 2.3 times more likely to accept the COVID-19 vaccine than those who failed to understand this (aOR 2.3, 95% CI 1.1–4.9). As expected, both understanding the most effective measures for preventing COVID-19 (aOR 2.4, 95% CI 1.2–4.7) and recognizing the priority vaccination groups (aOR 2.6, 95% CI 1.3–5.0) were positively correlated with the dependent variable. Understanding the transmission routes of COVID-19 infection was considered the most significant factor with an adjusted OR 8.8 and 95% CI 2.4–31.9 (). In parallel, participants perceiving the social harm and severity of COVID-19 (aOR 2.6, 95% CI 1.2–5.9 and aOR 3.1, 95% CI 1.1–8.7) and considering themselves a priority group for COVID-19 vaccination (aOR 2.6, 95%CI 1.2–5.9) were more likely to get vaccinated (). Furthermore, positive relationships were also observed in participants who attained more understanding of infectious disease prevention and control (aOR 2.6, 95% CI 1.1–6.1) and contained COVID-19 infection by maintaining adequate ventilation (aOR 2.4, 95%CI 1.1–5.4) (). However, the remaining variables regarding the COVID-19-related KAP were not significantly associated with the dependent variable.

Reasons for willingness or not to receive a COVID-19 vaccine

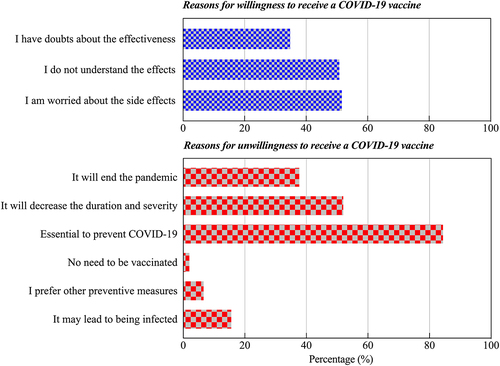

Moving away from the bivariate and multivariate logistic regression analyses, it is also necessary to pay attention to the reasons people were willing or not to be vaccinated. Among the 76% of participants willing to be vaccinated against COVID-19, the majority (84%) said that COVID-19 vaccination is vital to stop COVID-19 infection. However, the three main reasons for participants’ vaccination refusal included 52% worried about side effects of the COVID-19 vaccine, 51% failed to believe in the vaccine’s effectiveness, and 35% would not be vaccinated until the vaccine is in greater use ().

Discussion

Principal results

This cross-sectional survey represents the first investigation regarding COVID-19 vaccination willingness among cold-chain workers worldwide and might be used to map out future vaccine administration. Although the most participants (76%) of this study displayed an intention to be vaccinated against COVID-19, the objective of herd immunization against COVID-19 remains far from being achieved. KAP related to COVID-19 were important factors influencing their vaccination willingness. The majority of participants (84%) in the willingness group believed it is essential to prevent COVID-19 through vaccination. In comparison, more than half of the participants refused to be vaccinated because of concerns about side effects (52%) and insufficient understanding of vaccine efficacy (51%).

A prior study has reported that the prevalence of COVID-19 vaccine acceptance was 74% of 7664 adults from six European countries and the United Kingdom (UK).Citation38 A relevant study indicated that 65% and 69% of the general adults would be willing to get vaccinated for COVID-19 in Ireland and the UK, respectively.Citation39 Another study in the United States reported that 56% of U.S. citizens were somewhat or very likely to get a COVID-19 vaccine.Citation40 In Africa, relevant research showed that only around half of the citizens (56%) intended to get vaccinated in the Democratic Republic of Congo.Citation20 In Asia, it has been demonstrated that nearly 62% of Japanese adults had the intention of getting COVID-19 vaccine when it becomes available,Citation41 while an overwhelming number of participants in China (91%) expressed their willingness to receive it at the time it was developed successfully and approved for listing.Citation4 As discussed previously, although our findings are relatively higher than most of these percentages, it is not easy to accurately compare our study and prior ones because of differences in questionnaires, populations, the timing of these surveys, and local vaccine policies.Citation41 In contrast to other occupational groups in China, the prevalence of willingness conditional on cost-free COVID-19 vaccination was close to that reported in healthcare workers (77%)Citation42and university students (79%)Citation43but lower than that of the factory workers (81%) in the same study site.Citation44 Meanwhile, it was higher than parental acceptability for their children under 18 years (73%).Citation45 It was found that the willingness rates were not significantly different among different occupational groups.

It has been widely recognized that not enough vaccines are available for the entire global population to be vaccinated against COVID-19. There is no doubt that healthcare workers in all settings should be vaccinated first, but who is next to be prioritized for vaccination has become a global issue.Citation46 Government decisions across the world on this issue might be somewhat different because of distinctions in local epidemiology and societal values.Citation46 Nevertheless, it was a common global consensus that workers in high-risk employment could be given priority.Citation46 Given the fact that a number of localized COVID-19 outbreaks in China could be tracked to cold-chain workers, we suggest that effective health promotion is needed to improve self-protection and vaccination behaviors in various countries.

Decision-making with respect to COVID-19 vaccination could be influenced by various factors, including sociodemographic characteristics, COVID-19-related KAP, political views, and vaccine policies.Citation41,Citation47 Consequently, it is indispensable to evaluate vaccine acceptance and its associated factors to implement educational activities for targeted populations to improve vaccination acceptance. In this study, we identified some obstacles in achieving a high acceptance rate for the COVID-19 vaccine. First, insufficient knowledge about COVID-19 and the most effective way to prevent it and failure to identify priority groups for COVID-19 vaccination were inversely associated with willingness to be vaccinated. The factor that primarily hindered COVID-19 vaccination willingness was observed in the cold-chain workers who failed to recognize the transmission routes of COVID-19 infection. Interventions targeted at increasing COVID-19-related knowledge might lead to increased vaccination rates. Second, our participants who perceived social harmfulness and seriousness of COVID-19 had more intention to receive a COVID-19 vaccine, consistent with other previous findings.Citation39,Citation41 This suggested that the study participants’ perceptions need to be enhanced, as the perception of high risk would translate into preventive behaviors for infectious diseases that would help epidemic prevention and control.Citation3,Citation48 Finally, increased associations with the willingness to be vaccinated were observed in participants who were self-reported to obtain more understanding of infectious diseases prevention and control and those who prevented COVID-19 infection by maintaining adequate ventilation. In this regard, some participants might have mistakenly thought that closing windows could prevent the virus from entering. Keeping the rooms well-ventilated should be highlighted in facilitating health education.

As expected, most participants (97%) preferred to take measures against COVID-19 infection by wearing a mask outside, while the lowest frequency was found through doing more exercises. This observation seemed to be as result of the recommended precautions for COVID-19 by the Chinese government. However, no significant association was found between demographic variables and COVID-19 vaccination willingness in the present study (data not shown). The small sample size of this study might be the possible reason for the result. Therefore, further large-scale population-based investigations should be carried out to determine whether the willingness to get vaccinated would differ across demographic characteristics among cold-chain workers.

Despite the finding that most participants displayed a willingness to be vaccinated against COVID-19, it is still worthwhile to investigate the possible reasons for their vaccination decision.Citation4 In the group that intended to get a COVID-19 vaccination, many participants (84%) believed the vaccine is of vital importance to curb COVID-19 infection. Others considered that vaccination would reduce the duration and severity of being infected with COVID-19 (52%) and even stop the ongoing pandemic (38%). In terms of vaccine refusal, the most important predictor was concern about side effects of the COVID-19 vaccine (52%), followed closely by failure to understand its efficacy (51%). These findings coincided with previous studies explaining refusal for COVID-19 vaccination.Citation4,Citation23 A previous study reported that 17% and 29% of 3195 Chinese adults were worried about the safety and side effects of the COVID-19 vaccine, respectively.Citation3 Another prior study also indicated that influenza vaccines’ safety and side effects were considered the most common reasons for vaccination hesitancy.Citation49 Moreover, public concerns related to vaccine safety and adverse events have been reported frequently as the main barriers to vaccination decision-making, especially for recently introduced vaccines that have not been thoroughly tested.Citation4,Citation8,Citation9,Citation50

As we conducted the present study in the pre-vaccine stage, great efforts have been done to increase the effectiveness of vaccination campaign programs and uptake in light of the significant KAP issues and reasons for reluctance to get vaccinated. The comprehensive COVID-19-related information was further conveyed to the study population by the local CDC and Shenzhen Administration for Market Regulation. Except for a few people with contraindications to the vaccine, the current real vaccination rate of the study population is greater than 95% (unpublished data from Shenzhen CDC), which fully reflects the paramount public health significance of similar investigations. With the second or third dose of the COVID-19 vaccine being available, continuing to survey the willingness toward COVID-19 vaccination remains a future trend, as is the case with influenza and pneumococcal vaccines. Additionally, our findings might be helpful to put forward policy recommendations to government in case of future similar conditions.

Limitations

Some potential limitations must be acknowledged. First, the targeted population consisted of cold-chain workers from a single center that was not generalizable to all cold-chain workers in China. Second, the collected information, especially the history of underlying diseases, might be subject to recall bias due to the utilization of self-reported questionnaires given this critical moment. Third, the market type failed to be included in the analyses and that might lead to selection bias. Finally, this survey was conducted before the COVID-19 vaccine became available for the public, such that the results might be somewhat different if carried out today.

Conclusions

Overall, this population-based study indicated that 76% of cold-chain workers expressed a willingness to be vaccinated against COVID-19. Knowledge, attitudes, and practices toward COVID-19 were significant factors associated with the COVID-19 vaccine acceptance. Agreement on the importance of vaccination to prevent COVID-19 was the most frequent reason for COVID-19 vaccination willingness. At the same time, concerns about side effects and poor understanding of efficacy were the main factors contributing to vaccine refusal. After addressing the barriers to vaccination among cold-chain workers, the current actual coverage rate of the COVID-19 vaccine has been significantly increased. Given that the second or third dose of COVID-19 vaccine has been available in China, we suggest that educational activities should be promptly implemented in light of the updated vaccine situations to increase future acceptance of the COVID-19 vaccine.

Abbreviations

| COVID-19 | = | Coronavirus disease 2019 |

| SARS-CoV-2 | = | Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 |

| KAP | = | Knowledge, Attitudes, and Practices |

| OR | = | Odds Ratio |

| aOR | = | adjusted Odds Ratio |

| CI | = | Confidence Interval |

| WHO | = | World Health Organization |

| CDC | = | Centre for Disease Control and Prevention |

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (29.3 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed on the publisher’s website at https://doi.org/10.1080/21645515.2022.2056400

Additional information

Funding

References

- Velavan TP, Meyer CG. Mild versus severe COVID-19: laboratory markers. Int J Infect Dis. 2020;95:1–10. doi:10.1016/j.ijid.2020.04.061. PMID: 32344011.

- Lurie N, Saville M, Hatchett R, Halton J. Developing Covid-19 vaccines at pandemic speed. N Engl J Med. 2020 May 21;382(21):1969–73. doi:10.1056/NEJMp2005630. PMID: 32227757.

- Chen M, Li Y, Chen J, Wen Z, Feng F, Zou H, Fu C, Chen L, Shu Y, Sun C, et al. An online survey of the attitude and willingness of Chinese adults to receive COVID-19 vaccination. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2021 Jan;31:1–10. doi:10.1080/21645515.2020.1853449. PMID: 33522405.

- Wang J, Jing R, Lai X, Zhang H, Lyu Y, Knoll MD, Fang H, et al. Acceptance of COVID-19 vaccination during the COVID-19 pandemic in China. Vaccines (Basel). 2020;8(3). doi:10.3390/vaccines8030482. PMID: 32867224.

- COVID-19 Vaccine Technical Working Group. Technical vaccination recommendations for COVID-19 vaccines in China (First Edition). China CDC Weekly. 2021;3(21):459–61. doi:10.46234/ccdcw2021.083.

- National COVID-19 vaccination status. National Health Commission of People’s Republic of China. [accessed 2022 March 7]. http://www.nhc.gov.cn/xcs/yqfkdt/202203/51618a50fffb4dd5b40f3e2a656ec0e3.shtml.

- Coronavirus (COVID-19) vaccinations. Our World in Data. [assessed 2022 March 7]. https://ourworldindata.org/covid-vaccinations.

- Nguyen T, Henningsen KH, Brehaut JC, Hoe E, Wilson K. Acceptance of a pandemic influenza vaccine: a systematic review of surveys of the general public. Infect Drug Resist. 2011;4:197–207. doi:10.2147/idr.S23174. PMID: 22114512.

- Larson HJ, Jarrett C, Eckersberger E, Smith DM, Paterson P. Understanding vaccine hesitancy around vaccines and vaccination from a global perspective: a systematic review of published literature, 2007-2012. Vaccine. 2014;32(19):2150–59. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2014.01.081. PMID: 24598724.

- Eastwood K, Durrheim DN, Jones A, Butler M. Acceptance of pandemic (H1N1) 2009 influenza vaccination by the Australian public. Med J Aust. 2010;192(1):33–36. doi:10.5694/j.1326-5377.2010.tb03399.x. PMID: 20047546.

- Rachiotis G, Mouchtouri VA, Kremastinou J, Gourgoulianis K, Hadjichristodoulou C. Low acceptance of vaccination against the 2009 pandemic influenza A(H1N1) among healthcare workers in Greece. Euro Surveill. 2010;15(6):19486. PMID: 20158980.

- Sallam M. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy worldwide: a concise systematic review of vaccine acceptance rates. Vaccines (Basel). 2021 Feb 16;9(2). doi:10.3390/vaccines9020160. PMID: 33669441.

- Al Ahdab S. A cross-sectional survey of knowledge, attitude and practice (KAP) towards COVID-19 pandemic among the Syrian residents. BMC Public Health. 2021 Feb 5;21(1):296. doi:10.1186/s12889-021-10353-3. PMID: 33546652.

- Zhong BL, Luo W, Li HM, Zhang QQ, Liu XG, Li WT, Li Y, et al. Knowledge, attitudes, and practices towards COVID-19 among Chinese residents during the rapid rise period of the COVID-19 outbreak: a quick online cross-sectional survey. Int J Biol Sci. 2020;16(10):1745–52. doi:10.7150/ijbs.45221. PMID: 32226294.

- Al-Qerem WA, Jarab AS. COVID-19 vaccination acceptance and its associated factors among a Middle Eastern population. Front Public Health. 2021;9:632914. doi:10.3389/fpubh.2021.632914. PMID: 33643995.

- Wong MCS, Wong ELY, Huang J, Cheung AWL, Law K, Chong MKC, Ng RW, Lai CK, Boon SS, Lau JT, et al. Acceptance of the COVID-19 vaccine based on the health belief model: a population-based survey in Hong Kong. Vaccine. 2021 Feb 12;39(7):1148–56. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2020.12.083. PMID: 33461834.

- Liu R, Zhang Y, Nicholas S, Leng A, Maitland E, Wang J. COVID-19 vaccination willingness among Chinese adults under the free vaccination policy. Vaccines (Basel). 2021 Mar 21;9(3). doi:10.3390/vaccines9030292. PMID: 33801136.

- Zhang M, Chen H, Wu F, Li Q, Lin Q, Cao H, Zhou X, Gu Z, Chen Q, et al. Heightened willingness toward pneumococcal vaccination in the elderly population in Shenzhen, China: a cross-sectional study during the COVID-19 pandemic. Vaccines (Basel). 2021 Mar 3;9(3). doi:10.3390/vaccines9030212. PMID: 33802327.

- Jain S, Batra H, Yadav P, Chand S. COVID-19 vaccines currently under preclinical and clinical studies, and associated antiviral immune response. Vaccines (Basel). 2020 Nov 3;8(4). doi:10.3390/vaccines8040649. PMID: 33153096.

- Ditekemena JD, Nkamba DM, Mutwadi A, Mavoko HM, Siewe Fodjo JN, Luhata C, Obimpeh M, Van Hees S, Nachega JB, Colebunders R. COVID-19 vaccine acceptance in the democratic Republic of Congo: a cross-sectional survey. Vaccines (Basel). 2021;9(2). doi:10.3390/vaccines9020153. PMID: 33672938.

- Shekhar R, Sheikh AB, Upadhyay S, Singh M, Kottewar S, Mir H, Barrett E, Pal S, et al. COVID-19 vaccine acceptance among health care workers in the United States. Vaccines (Basel). 2021;9(2). doi:10.3390/vaccines9020119. PMID: 33546165.

- Gagneux-Brunon A, Detoc M, Bruel S, Tardy B, Rozaire O, Frappe P, Botelho-Nevers E, et al. Intention to get vaccinations against COVID-19 in French healthcare workers during the first pandemic wave: a cross-sectional survey. J Hosp Infect. 2021;108:168–73. doi:10.1016/j.jhin.2020.11.020. PMID: 33259883.

- Verger P, Scronias D, Dauby N, Adedzi KA, Gobert C, Bergeat M, Gagneur A, Dubé E, et al. Attitudes of healthcare workers towards COVID-19 vaccination: a survey in France and French-speaking parts of Belgium and Canada, 2020. Euro Surveill. 2021;26(3). doi:10.2807/1560-7917.Es.2021.26.3.2002047. PMID: 33478623.

- Ma JZ H, Wang J, Qin Y, Chen C, Song Y, Wang L, Meng J, Mao L, Li F, et al. COVID-19 outbreak caused by contaminated packaging of imported cold-chain products — Liaoning Province, China, July 2020. China CDC Weekly. 2021;3(21):441–47. doi:10.46234/ccdcw2021.114.

- Liu P, Yang M, Zhao X, Guo Y, Wang L, Zhang J, Lei W, Han W, Jiang F, Liu WJ. Cold-Chain transportation in the frozen food industry may have caused a recurrence of COVID-19 cases in destination: successful isolation of SARS-CoV-2 virus from the imported frozen cod package surface. Biosaf Health. 2020;2(4):199–201. doi:10.1016/j.bsheal.2020.11.003. PMID: 33235990.

- Fang F, Song Y, Hao L, Nie K, Sun X. A case of COVID-19 detected in a Cargo worker at Pudong Airport — Shanghai Municipality, China, November 8, 2020. China CDC Weekly. 2020;2(47):910–11. doi:10.46234/ccdcw2020.246.

- Sim S, Wiwanitkit V. Food contamination, food safety and COVID-19 outbreak. J Health Res. 2021;35(5):463–466. doi:10.1108/JHR-01-2021-0014.

- Lewis D. Can COVID spread from frozen wildlife? Scientists probe pandemic origins. Nature. 2021;591(7848):18–19. doi:10.1038/d41586-021-00495-0. PMID: 33637864.

- Li B, Yeru W, Yibaina W, Yongning W, Ning L, Zhaoping L. Controlling COVID-19 transmission due to contaminated imported frozen food and food packaging. China CDC Weekly. 2021;3(2):30–33. doi:10.46234/ccdcw2021.008.

- Group C-F, Laboratory Testing G, Ying Z. The source of infection of the 137th confirmed case of COVID-19 — Tianjin municipality, China, June 17, 2020. China CDC Weekly. 2020;2(27):507–10. doi:10.46234/ccdcw2020.122.

- Pang X, Ren L, Wu S, Ma W, Yang J, Di L, Li, J, Xiao, Y., Kang, Lu, Du, S. Cold-Chain food contamination as the possible origin of COVID-19 resurgence in Beijing. Natl Sci Rev. 2020;7(12):1861–64. doi:10.1093/nsr/nwaa264.

- Zhao X, Mao L, Zhang J, Zhang Y, Song Y., Bo Z, Wang, H, Wang, Ji, Chen, C, Xiao, J. Reemergent cases of COVID-19 — Dalian city, Liaoning Province, China, July 22, 2020. 2020;2(34):658–60. doi:10.46234/ccdcw2020.182.

- Statistics Bureau of Shenzhen Municipality. Shenzhen Statistics Yearbook (2019); 2019 [accessed 2021 March 31]. http://tjj.sz.gov.cn/attachment/0/695/695422/7971762.pdf.

- Ma Y, Li T, Chen W, Chen J, Li M, Yang ZK. Attitudes and practices (KAP) toward seasonal influenza vaccine among young workers in South China. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2018 May 4;14(5):1283–93. doi:10.1080/21645515.2017.1423157. PMID: 29308971.

- Notice on printing and distributing the guideline for diagnosis and treatment of COVID-19 (Trial Eighth Edition). National Health Commission of People’s Republic of China. [accessed 2021 March 31]. http://www.gov.cn/zhengce/zhengceku/2020-08/19/content_5535757.htm.

- Notice on printing and distributing the guideline for prevention and control of COVID-19 (Seventh Edition). National Health Commission of People’s Republic of China. [accessed 2021 March 31]. http://www.nhc.gov.cn/jkj/s3577/202009/318683cbfaee4191aee29cd774b19d8d.shtml.

- Shekhar R, Sheikh AB, Upadhyay S, Singh M, Kottewar S, Mir H, Barrett E, Pal S. COVID-19 vaccine acceptance among health care workers in the United States. Vaccines (Basel). 2021 Feb 3;9(2):119. PMID: 33546165.

- Neumann-Böhme S, Varghese NE, Sabat I, Barros PP, Brouwer W, van Exel J, Schreyögg, J, Stargardt, T. Once we have it, will we use it? A European survey on willingness to be vaccinated against COVID-19. Eur J Health Econ. 2020;21(7):977–82. doi:10.1007/s10198-020-01208-6. PMID: 32591957.

- Murphy J, Vallières F, Bentall RP, Shevlin M, McBride O, Hartman TK, McKay R, Bennett K, Mason L, Gibson-Miller J, et al. Psychological characteristics associated with COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy and resistance in Ireland and the United Kingdom. Nat Commun. 2021 Jan 4;12(1):29. doi:10.1038/s41467-020-20226-9. PMID: 33397962.

- Szilagyi PG, Thomas K, Shah MD, Vizueta N, Cui Y, Vangala S, Kapteyn, A. National Trends in the US Public’s Likelihood of Getting a COVID-19 Vaccine—April 1 to December 8, 2020. Jama. to December 8, 20202020 Dec 29;325(4):396–98. doi:10.1001/jama.2020.26419. PMID: 33372943.

- Machida M, Nakamura I, Kojima T, Saito R, Nakaya T, Hanibuchi T, Takamiya T, Odagiri Y, Fukushima N, Kikuchi H, Amagasa S, et al. Acceptance of a COVID-19 vaccine in Japan during the COVID-19 pandemic. Vaccines (Basel). 2021 Mar 3;9(3). doi:10.3390/vaccines9030210. PMID: 33802285.

- Sun Y, Chen X, Cao M, Xiang T, Zhang J, Wang P, Dai, H. Will healthcare workers accept a COVID-19 vaccine when it becomes available? A cross-sectional study in China. Front Public Health. 2021;9:664905. doi:10.3389/fpubh.2021.664905. PMID: 34095068.

- Mo PK, Luo S, Wang S, Zhao J, Zhang G, Li L, Li L, Xie L, Lau JT, et al. Intention to receive the COVID-19 vaccination in China: application of the diffusion of innovations theory and the moderating role of openness to experience. Vaccines (Basel). 2021 Feb 5;9(2). doi:10.3390/vaccines9020129. PMID: 33562894.

- Zhang KC, Fang Y, Cao H, Chen H, Hu T, Chen Y, Zhou, X, Wang, Z. Behavioral intention to receive a COVID-19 vaccination among Chinese factory workers: cross-sectional online survey. J Med Internet Res. 2021 Mar 9;23(3):e24673. doi:10.2196/24673. PMID: 33646966.

- Zhang KC, Fang Y, Cao H, Chen H, Hu T, Chen YQ, Zhou X, Wang Z, et al. Parental acceptability of COVID-19 vaccination for children under the age of 18 years: cross-sectional online survey. JMIR Pediatr Parent. 2020 Dec 30;3(2):e24827. doi:10.2196/24827. PMID: 33326406.

- Russell FM, Greenwood B. Who should be prioritised for COVID-19 vaccination?. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2021 May 4;17(5):1317–21. doi:10.1080/21645515.2020.1827882. PMID: 33141000.

- MacDonald NE. Vaccine hesitancy: definition, scope and determinants. Vaccine. 2015 Aug 14;33(34):4161–64. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.04.036. PMID: 25896383.

- Wong LP, Alias H, Wong PF, Lee HY, AbuBakar S. The use of the health belief model to assess predictors of intent to receive the COVID-19 vaccine and willingness to pay. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2020 Sep 1;16(9):2204–14. doi:10.1080/21645515.2020.1790279. PMID: 32730103.

- Lau AY, Sintchenko V, Crimmins J, Magrabi F, Gallego B, Coiera E. Impact of a web-based personally controlled health management system on influenza vaccination and health services utilization rates: a randomized controlled trial. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2012 PMID: 22582203;19(5):719–27. doi:10.1136/amiajnl-2011-000433.

- Yaqub O, Castle-Clarke S, Sevdalis N, Chataway J. Attitudes to vaccination: a critical review. Soc Sci Med. 2014;112:1–11. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.04.018. PMID: 24788111.