ABSTRACT

Parent hesitancy contributes to reduced HPV vaccination rates. The HPVcancerfree app (HPVCF) was designed to assist parents in making evidence-based decisions regarding HPV vaccination. This study examined if parents of vaccine-eligible youth (11–12 yrs.) who use HPVCF in addition to usual care demonstrate significantly more positive intentions and attitudes toward HPV vaccination and greater HPV vaccination rates compared to those not using HPVCF. Clinics (n = 51) within a large urban pediatric network were randomly assigned to treatment (HPVCF + usual care) or comparison (usual care only) conditions in a RCT conducted between September 2017 and February 2019. Parents completed baseline and 5-month follow-up surveys. Participant-level analysis determined 1) change in HPV vaccination initiation behavior and related psychosocial determinants and 2) predictors of HPV vaccine initiation. Parents (n = 375) who completed baseline and 5-month follow-up surveys were female (95.2%), 40.8 (±5.8) yrs. married (83.7%), employed (68.3%), college educated (61.9%), and privately insured (76.5%). Between-group analysis of HPVCF efficacy demonstrated that parents assigned to receive HPVCF significantly increased knowledge about HPV and HPV vaccination (p < .05). Parents who accessed content within HPVCF significantly increased knowledge about HPV & HPV vaccine (p < .01) and perceived effectiveness of HPV vaccine (p < .05). Change in HPV vaccine initiation was not significant. A multivariate model to describe predictors of HPV vaccine initiation demonstrated an association with Tdap and MCV vaccination adoption, positive change in perceived effectiveness of the HPV vaccine, and reduction in perceived barriers against HPV vaccination. HPVCF appears to be a feasible adjunct to the education received in usual care visits and reinforces the value of apps to support the important persuasive voice of the health-care provider in overcoming parent HPV vaccine hesitancy.

Introduction

Background and objectives

Persistent HPV infection causes nearly all cervical cancers, estimated at 35,900 cancer cases per year.Citation1 Evidence shows that CDC and ACIP-recommended HPV vaccination at a young age can prevent cervical cancer.Citation2 Despite recommendations to initiate HPV vaccination at the 11 and 12 year old annual visits, in 2019 just 71.5% of U.S. adolescents received the first dose of the HPV vaccine compared with Tdap (90.2%) and meningitis (MCV) (88.9%).Citation3 Despite the benefits of HPV vaccination,Citation4 common barriers include misunderstanding how the HPV vaccine prevents cancer, such as preventing infection rather than progression of an infection to disease,Citation5 and that the immune response is greatest when administered at a younger age.Citation6–8 The Community Preventive Services Task Force has identified a number of evidence-based implementation strategies that increase vaccination, including provider assessment and feedback, provider prompts regarding vaccine-eligible youth, and patient scheduling reminders and prompts.

Strong provider recommendations regarding the vaccine (e.g., presumptive statements regarding the child’s vaccine agenda and rolling with patient resistance) can increase vaccination rates.Citation1,Citation9 Ultimately, parental motivation to vaccinate is paramount, yet physicians report parental vaccine hesitancy as a significant barrier to vaccination at the recommended 11- and 12-year-old well checkup.Citation10–12 Resultant delayed vaccination leads to missed opportunities at a time when younger adolescents have three times more preventive visits than older adolescents.Citation13,Citation14

The reasons why parents decline to initiate the HPV vaccination as recommended vary. National Immunization Survey-Teen trend data (2010 to 2016) indicate common sources of hesitancy including safety concerns, a lack of vaccine knowledge and perceived lack of necessity.Citation15 Psychosocial factors that related to behaviors to initiate or complete the HPV vaccine series are summarized in a 2019 systematic review of 71 U.S.-based studies exploring HPV vaccine beliefs.Citation16 The review found four negative beliefs: perceived adverse effects (promotes sexual activity, too new, causes illness); perceived lack of necessity, related to perceptions of their child’s susceptibility to HPV infection; morality concerns; and skepticism about effectiveness, and one positive belief (prevents STIs) across the literature ().Citation16

Addressing factors that negatively affect parental vaccination decision-making is a key strategy to improving HPV vaccination rates.Citation17,Citation18 Providers are the most trusted sources of health information, even for vaccine hesitant parents, and provider recommendations are a strong determinant of vaccination. However, provider HPV vaccination recommendations are inconsistent, and often weak.Citation19 In addition, parents increasingly seek other sources of health information, such as television and social media.Citation20 Regardless of accuracy, social media messaging has the power to influence parent vaccination behavior.Citation21 Social media exposure has been associated with HPV vaccine refusal and an increased tendency to share negative content with others with concerns about vaccine safety, potential side effects, and lack of efficacy.Citation22 Parent decisions to follow HPV vaccination guidelines has been challenged by mixed messages and misinformation regarding HPV vaccines.

Strategies to provide parents with clear and evidence-based decision-making are needed to reach the HPV vaccination Healthy People goal of 80% series completion by ages 13–15 years. Thus, it is important that parents have access to accurate HPV vaccination information and access to parent education that addresses complex psychosocial barriers to HPV vaccination acceptance.

In this regard, digital behavioral change interventions may hold promise to positively influence vaccination behavior and offer an additional source of credible information in a social environment saturated with misinformation. The evidence-base for this is modest. A recent systematic review of apps to promote childhood vaccination indicated that relatively few studies demonstrated that app use was associated with vaccine uptake (n = 4/25; p ≤ .05) or on knowledge and on vaccine decision-making (n = 4/25; p ≤ .054) and that there was a need for more robust studies.Citation23

The HPVcancerfree app (HPVCF) was designed to assist parents to make evidence-based decisions regarding HPV vaccination through provision of facts and debunking of misperceptions regarding HPV and HPV vaccination. The purpose of this study is to determine if parents of vaccine-eligible youth who use HPVCF, in addition to usual care, demonstrate significantly greater HPV vaccination rates, improved intention to vaccinate, improved attitudes, and reduced barriers to HPV vaccination over a 5-month period compared to those who experience usual care without using HPVCF.

Materials and methods

Study design

The University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston (UTHealth), School of Public Health and Baylor College of Medicine collaborated on this pre- and posttest randomized, controlled trial (RCT) from September, 2017 through March 2019 (). Clinics within a 51 clinic network were randomly assigned to the behavioral intervention. Parents in intervention clinics were invited to use the HPVCF app in the context of usual care. Parents in the comparison group received no access to the HPVCF app.

Setting, sample, and recruitment

Setting: The study was conducted through a clinic network that is the largest group of general pediatricians in the U.S. The network was established in 1995 and is the primary care group affiliated with Texas Children’s Hospital and Baylor College of Medicine through which patients have access to a range of pediatric subspecialties. The clinic network is based in five counties and serves over 100,000 children and adolescents 11–17 years of age, and approximately 30% of the pediatric population in the Houston area. At the time of the study, there were 249 physicians and 23 nurse practitioners, in addition to other clinical staff. During the quarter preceding the study period (April–June, 2017), assessed at baseline, the pediatric patient population (10–17 years of age) numbered 57,084. Patient demographics comprised mean age 13.5 (±2.2) years; 50.6% female; and ethnic composition of non-Hispanic white (46.6%), Hispanic (25.1%), non-Hispanic African American (12.2%), Asian (4.7%), and other (11.4%). Patient insurance coverage comprised mainly private insurance (80.9%) and public insurance (19.1%). A majority of the population had received at least one dose the HPV vaccine (62.8%); and 41.4% had completed the HPV vaccine series. All practices participated in the Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set (HEDIS) and were NCQA-recognized medical homes, several keeping extended hours including Saturdays. The rates for the mandated vaccinations (Tdap and MCV) within the network were 88.7% and 90.5%, respectively, at baseline. These were significantly higher than HPV vaccination rate (62.8%) at the commencement of the study.

Sample: The priority population was parents of 11–17 year-old male and female patients. The emphasis for intervention was on younger adolescents, corresponding to recommendations to initiate the vaccination process when patients are 11–12 years old and receive other concurrently recommended vaccinations.

Inclusion/exclusion criteria

Inclusion criteria comprised consent to participation in pre- and post-surveys about adolescent vaccination, being the parent or guardian of an active patient at TCP, having at least one child between the ages of 10 and 17 who had never received any HPV vaccines at TCP or elsewhere and with no contraindication for vaccination (e.g., severe allergies and severe illness). Parents must have had access to a mobile device (e.g., tablet, computer, and smartphone) and be able to speak and write in English. Parents of patients 18 years of age and older were excluded because parental consent is not required for vaccination.Citation24

Clinic randomization to study condition

Clinics (n = 51) were randomized using stratified randomization, by mean HPV initiation rate (±62.8%) and mean clinic size (±1,377 patients ages 11–17) seen during the quarter prior to the baseline parent survey (April through June 2017). Clinics were randomized to the treatment study condition that would link parent participants to HPVCF (n = 26) or to the comparison condition that would provide parents with usual care only (n = 25). Patients were seen by their regular pediatricians who were not residents. There were no statistically significant differences in group size or HPV initiation rates between the two groups after randomization (p = .2191). Intraclass correlation (ICC) was expected to be less than 0.1Citation25 ICC estimates from 0.01 to 0.1, with 80% power and 2-sided alpha of <0.05 provided an estimated detectable difference of 10–15% depending upon survey response rates.Citation26–28

Recruitment for the study took place from September 2017 to September 2018. Parents were invited to take part in the study through, in order of recruitment success, MyChart patient portal messages, fliers in the clinics, posts on the clinic network Facebook page, and through their providers during the course of regular visits. All parent participants were asked to complete baseline (pretest) and follow-up (posttest) surveys. Parents who were randomized to usual care clinics were informed by the research team that they would be asked to complete another survey in 6 to 9 months and would not be contacted again until that time. Parents who were randomized to the treatment (HPVCF) condition were provided an e-mail with a link to HPVCF subsequent to survey completion. They were asked to download and view HPVCF. Parents were asked to do this in the course of their typical activities. They were not given prescriptive instructions to review or complete particular components of HPVCF or given a prescriptive duration of use other than to access HPVCF before the study posttest survey which would contain questions about their perceptions of HPVCF. All participating parents received a $50 gift card for completing both surveys. This project received human subjects research approval from the local institutional review board at the University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston (UTHealth) and Baylor College of Medicine (IRB# SPH- 15-0202).

Intervention

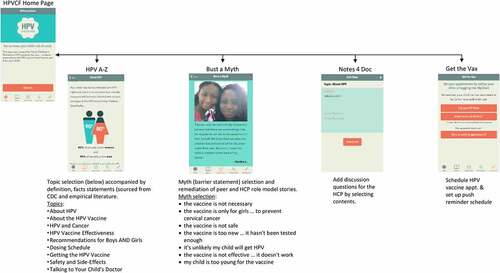

HPVcancerFree app (HPVCF) was designed for use by English = speaking parents of HPV vaccine-eligible patients 11–17 years of age at TCP clinics.Citation29–31 It is compatible with iOS and Android systems on mobile devices. HPVCF was designed to provide parent educational content to reduce barriers and increase willingness to initiate HPV vaccination among 11–17-year-old children, enable parents to record talking points regarding the HPV vaccine for discussion with the HCP at a future appointment, and to provide a reminder system for HPV vaccine dose appointments to promote completion of the series. HPVCF comprises four components accessible through tabs from the homepage (): 1) ‘HPV A-Z’ (a compendium of content domains (n = 9) providing facts about HPV and HPV vaccine), 2) ‘Bust A Myth’ (educational modules (n = 7) including peer and provider testimonials addressing the most salient HPV vaccination barriers); 3) ‘Notes 4 Doc’ (a medium to facilitate communication with providers on HPV vaccine), and 4) ‘Get the Vax’ (enabling parents to schedule tailored HPV vaccination appointment reminders). HPVCF was developed based on behavioral theory and empirical evidence using a stepped program planning framework, Intervention Mapping (IM).Citation32 The theoretical basis of HPVCF included the Health Belief Model,Citation33 Social Cognitive Theory,Citation34 and Theory of Reasoned Action.Citation35 IM guided identification of HPV vaccination behaviors and determinants of vaccination behaviors. Determinants were identified in the literature and included risk perception (knowledge, perceived susceptibility, perceived effectiveness), attitudes (intentions, outcome expectations, perceived barriers), self-efficacy, and perceived social norms (). Methods and practical strategies were selected to target the behavioral determinants and provided the basis of the AVPCF structure and content. Prior to the RCT, usability testing was conducted with parents to establish the acceptability and perceived feasibility of HPVCF for implementation.

Measures

The baseline (pretest) survey assessed clinic- and participant-level demographics. Both baseline (pretest) and 5-month follow-up (posttest) surveys assessed vaccination initiation rates and psychosocial predictors of vaccination (). Process and fidelity measures, collected throughout the study, included assessment of exposure to the HPVCF.

Table 1. Description of measures.

Participating clinic demographics

Clinic aggregated HPV vaccination initiation rate was based on the Electronic Health Record (EHR) data. Clinic size (numbers of physician providers and patients 11–17 years) was based on available network data and clinic manager self-report. Descriptive data on clinic implementation of evidence-based HPV vaccination strategies (i.e., clinic vaccination champion, provider CME, A&F reports, EMR prompts, and patient reminders) was based on fidelity data collected in a previously reported prevention trial assessing these strategies.Citation40

Participating parent demographics

Parent and child demographics comprised number of children in the family, recruitment channel, parent gender and age, child gender and age, race/ethnicity, parent marital status, employment, and education, HPV vaccination status of child (parent self-report), medical insurance, and attitudes toward vaccination. Parents of multiple vaccine-eligible children provided responses pertaining to their youngest unvaccinated child.

Vaccine initiation

Participant vaccination rates were measured as the proportion of the study participants who reported that their vaccine-eligible child received at least one HPV vaccine (initiated) between the pre-survey and completion of the post-survey.

Psychosocial predictors of vaccination behavior

Pre- and posttest surveys comprised adapted scales and items assessing constructs previously demonstrated to be predictive of HPV vaccination initiation (). These included intention to vaccinate, knowledge, perceived effectiveness, outcome expectations, perceived susceptibility, barriers, and norms, perceived future regret, and self-efficacy (). Intention to vaccinate was assessed with a single 5-point Likert-type item (I have no intention/haven’t thought about/considering/probably will/definitely will get my child the HPV vaccine). Knowledge regarding HPV and the HPV vaccine was assessed using a 6-item scale (e.g., Most sexually active people will get HPV at some point in their lives.) with a True/False/Don’t know response format.Citation40 Knowledge regarding sequelae of HPV was assessed with a single item stating that ‘The HPV vaccine can prevent the following health conditions’ for which the respondent selects all that apply from the following: Cervical/Mouth and throat/Anal/Penile/Vulvar/Vagina/Genital warts). The resultant score represents the cumulative total of correct selections. Perceived effectiveness was assessed using a two-item scale (i.e., How effective do you think the HPV vaccine is in preventing [cancers caused by HPV/preventing genital warts] with a 4-point Likert response scale (Not at all to very effective). Outcome expectations of the HPV vaccination for protection was assessed using a 3-item scale (e.g., Getting the HPV vaccine would be a good way to protect my child from getting certain kinds of cancers) with a 4-point Likert scale (Strongly disagree to strongly agree).Citation36 Internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha) was 0.85 for the scale with the current sample. Outcome expectations for contracting HPV in the future was assessed using a single item (i.e., Without the HPV vaccine, what do you think is the chance that your child will get HPV in the future?) with a 4-point Likert scale (High chance to low chance).Citation39 Perceived susceptibility was assessed using a two-item scale (i.e., I’m worried my child will be infected with HPV when he/she is a [teenager/adult]?) using a 4-point Likert scale (Strongly agree to strongly disagree).Citation38 Perceived barriers was assessed with an 8-item scale representing commonly attributed barriers to HPV vaccine hesitancy of safety (e.g., I am concerned about the safety of the HPV vaccine), side effects (e.g., I am concerned about the possible side effects of the HPV vaccine), lack of information (e.g., I don’t have enough information about the HPV vaccine to decide whether to give it to my child), newness of the vaccine (The HPV vaccine is so new that I want to wait a while before deciding if my child should get it), cost (e.g., I am concerned that the HPV vaccine costs more than I can pay), that the child is too young (e.g., My child is too young to get a vaccine for a sexually transmitted infection like HPV), that the child is more likely to have sex (e.g., If my child gets the HPV vaccine, he/she may be more likely to have sex), and that getting the vaccine is too much of a hassle (e.g., Taking my child to the pediatrician to get all required doses in the HPV vaccine series would be a hassle). The scale used a 4-point Likert scale (Strongly disagree to strongly agree).Citation38 Internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha) was 0.75 for the scale with the current sample. Perceived norms was assessed with a 4-item scale (e.g., Most parents at Texas Children’s Pediatrics are giving their children the HPV vaccine) using a 4-point Likert scale (Strongly disagree to strongly agree).Citation36 Internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha) was 0.67 for the scale with the current sample. Perceived future regret was assessed with a single item (i.e., Imagine that your child got an HPV infection that could lead to cancer. How much would you regret it if your child did NOT get the HPV vaccine?) using a 4-point Likert scale (Not at all to a lot).Citation39 Self-efficacy was assessed as confidence to communicate with the HCP about HPV using a 4-item scale (e.g., How confident are you in your ability to ask your child’s pediatrician questions about the HPV vaccine?) using a 4-point Likert scale (Not at all confident to very confident). Internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha) was 0.79 for the scale with the current sample.

Process measures

The surveys for participants randomized to the intervention group contained additional specific questions pertaining to app usage, relevance and enjoyment.Citation30 HPVCF exposure data comprised back-end analytics on download that represent dose of exposure, including number of visits, page access, and time-on-task, as well as reach across intervention sites (e.g., parent participants by clinic). Usability testing assessed HPVCF acceptability, credibility, understandability, ease, motivational appeal, and perceived impact and is reported elsewhere.Citation31

Analysis

Analysis of baseline clinic descriptors and demographics () was conducted at the participant level. To adjust for randomization by clinic, Chi-square tests for categorical variables and t-tests for continuous variables were conducted with cluster-weighted values that incorporated the ICC to correct for variation in clinic size, using Stata 16 for all analyses.Citation41 During the quarter preceding the study period, the HPV vaccination rates among the 51 clinics ranged from 43.4% to 87.2%. Logistic regression analysis with standard errors to account for clustering by clinic was used to compare changes in determinants among treatment groups ().Citation42,Citation43

Table 2. Clinic description and comparison by condition.

Table 3. Parent participant demographics.

Table 4. Pre & posttest mean comparison in determinants of HPV vaccine behavior between parents in the treatment condition who used HPVCF and parents in the comparison condition who did not use HPVCF.

Table 5. Association of determinants with HPV vaccine outcomes (n = 305).

The primary hypothesis was that those parents randomized to the treatment (HPVCF) condition would demonstrate significantly greater reported HPV vaccine initiation, intentions to vaccinate, and more positive movement at posttest in psychosocial variables than those parents randomized to the comparison condition. Inferential analyses examined between group (treatment and comparison) differences on pre-post tests for behavioral and psychosocial variables. Analysis was conducted for both comparison of parents randomized to the treatment group versus to the comparison group, and for HPVCF exposure (comparison of parents in the treatment group who used HPVCF versus parents in the comparison group) for a 2-tailed test of statistical significance. In the latter analysis HPVCF use was defined as viewing at least one page beyond the home screen. HPVCF use was verified by validating parent self-report against use data collected from app data base.

Exploratory analysis of determinants of HPV vaccine initiation was conducted using multivariable logit modeling of HPVCF use, positive parental vaccination behavior (self-reported Tdap and Meningococcal vaccination) and favorable parental psychosocial factors (knowledge, perceived effectiveness, outcome expectations, perceived susceptibility, perceived norms, perceived future regret, and self-efficacy). Univariate, multivariable (treatment and independent variable), and multivariable full Logit models were built using Stata/SE version 16 statistical software.Citation41 Initial selection of predictor variables in the model was based on conservative bivariate associations with 2-tailed p-values <.05.Citation43

Results

Clinic demographics

Clinic demographics. Within the 51 clinics participating in the study, equivalency was established between those randomly assigned to treatment and comparison conditions (). No difference existed between the treatment and comparison clinic sites on HPV vaccination rates or clinic size (number of providers). Clinic size (number of patients 10–17 years of age) was similar, although statistically significant, between treatment and comparison clinics, with 1389 vs. 1367 patients, respectively. No difference was found on the implementation of evidence-based strategies that have been associated with enhanced HPV vaccination rates including the existence of a clinic vaccination ‘champion’, exposure to provider CME, exposure to quarterly assessment and feedback reports, exposure to EMR prompts regarding patient vaccination eligibility, and use of patient reminders (e-mail, phone message).

Parent participant sample recruitment and retention

The denominator (those consenting to be in the study) consisted of the 512 eligible parents who completed the pre-survey (236 in the treatment (HPVCF) condition and 276 in the comparison condition) (). This represented 2.4% of the total patient population at baseline who were eligible for the HPV vaccine (i.e., unvaccinated). One hundred thirty-seven (26.8%) parents were lost to follow-up (did not complete the post-survey; ). Of the 375 eligible parents who completed the post-test survey, 168 were in the treatment [HPVCF] condition and 207 were in the comparison condition. This represented 73.2% of the baseline sample (and 1.8% of the vaccine eligible population in the network), providing power of 0.80 to determine a minimum difference between HPVCF users and usual care in HPV vaccination initiation, controlling for clusters. There was at least one, and a maximum of 22, parents participating from each of the 51 clinics. Of the 168 parents in the treatment group, 98 (58.3%) used HPVCF (viewed pages other than the home page), and 70 (41.6%) did not use HPVCF (either did not download it or did not move off the home screen). Research staff screening of the survey database led to 55 and 50 exclusions from the treatment and comparison groups, respectively. Criteria for exclusion included fraudulent data entry in Qualtrics (n = 13) identified as multiple attempts to complete more than one survey from the same location (e-mail address, IP/latitude/longitude, street address, or phone number) or multiple surveys completed by the same user providing differing eligibility criteria.

Participating parent demographics

Baseline surveys were completed between September 2017 and September 2018. Within the 375 participating parent and children dyads, equivalency was established between those randomly assigned to treatment and comparison conditions across all variables (). An exception was the gender of the child (p < .03). Most families (89.6%) reported having 1 or 2 children. Parents were mainly female (95.2%), 40.8 (±5.8) years of age, married (83.7%), employed (68.3%), college educated (61.9%), and privately insured (76.5%). Although most had not received the HPV vaccination (68.8%) most were positively disposed toward HPV vaccination and choosing to vaccinate (94.4%). A minority reported preferring to delay vaccination (4.5%) or choosing not to vaccinate (1.1%). Primary sources off HPV vaccine information were the HCP (n = 296), Internet (n = 223), and television (n = 100). The parent sample approximated the population of TCP on gender and ethnic composition. Ethnic composition comprised non-Hispanic white (55.9%), Hispanic (22.1%), non-Hispanic African American (13.3%), and Asian (6.1%). Despite a large Hispanic demographic, most patients preferred English (93.3%), 4.7% preferred Spanish, 3.6% spoke another language, and 2.1% had missing information. Other was less that reported in the TCP population (2.7%). The child participants were 11.2 years of age and mainly female (53.3%). Most parents had one child (59.2%) with 40.8% reporting 2 or more children. There were no differences in baseline demographic variables for those parents in the treatment condition who completed the baseline and follow-up surveys compared to those who only completed the baseline survey.

HPVcancerFree app (HPVCF) use

For parents in the treatment (HPVCF) condition, access to HPVCF ranged from 1 to 8 visits with an average of 2 (±1.25) visits.Citation30 Number of HPVCF page views ranged from 2 to 84 with a mode of 3 page views. Visit duration ranged from 3 to 36 min with an average visit time of approximately 3 min 27 sec. The most visited fact pages were on dosing schedule (60 total views) and safety and side effects (48 total views). Most visited ‘bust-a-myth pages were on the vaccine being too new (33 total views), that the 11-12-year-old child is too young to receive the vaccine (32 total views), and that the vaccine is not safe (32 total views).

HPVCF use and change in determinants of HPV vaccination

Parents in the treatment (HPVCF) condition (n = 168) demonstrated significantly improved knowledge about HPV and the HPV vaccine (p < .05) compared to parents in the comparison condition (, Column A). HPV vaccination initiation rates were not significantly different between study conditions.

Parents in the treatment (HPVCF) condition who were exposed to the HPVCF demonstrated significantly greater knowledge about HPV & HPV vaccine (p < .01) as well as perceived effectiveness of the HPV vaccine (p < .05) compared to parents in the comparison condition (, Column B). Those parents also demonstrated higher initiation of Tdap and MCV, greater knowledge about HPV-related disease, and more positive perceived norms though differences were not statistically significant. HPV vaccination initiation rates were not significantly different between parents in the treatment condition who used the HPVCF app and those in the comparison condition.

Predictors of HPV vaccination

Univariate logit models for the sample that were statistically significance for eight predictive factors of HPV vaccination remained significant in bivariate (treatment and independent variable) models. The culminating multivariate model demonstrated a significant association between the initiation of the HPV vaccine with 1) the prior initiation of Tdap and MCV vaccinations, 2) positive change in perceived effectiveness of the HPV vaccine, and 3) reduction in perceived barriers to initiating the HPV vaccine (all p < .05). Treatment condition (HPVCF or Usual Care) was not significant (, Column A). Univariate logit models for the exposure (per protocol) sample (parents who used the HPVCF) were significant for seven predictive factors of HPV vaccination. Five of these remained significant in bivariate (treatment and independent variable) models—Tdap, MCV, knowledge of HPV/HPV vaccine, and perceived barriers (all p < .05). The culminating multivariate model for the exposure (per protocol) model demonstrated a significant association between the initiation of the HPV vaccine with 1) the prior adoption of Tdap and MCV vaccinations, 2) positive change in perceived effectiveness of the HPV vaccine, and 3) reduction in perceived barriers to initiating the HPV vaccine (all p < .05). Treatment condition (HPVCF or Usual Care) was not significant (, Column B).

Discussion

The study is one of few that have investigated the efficacy of a decision-support app to overcome parent hesitancy for HPV vaccine initiation in a pediatric clinical network. The findings have implications for the potential of digital behavioral change interventions like the HPVCF to influence parent decision-making and initiation of HPV vaccination.

Vaccination initiation behavior

HPV vaccine initiation behavior was not found to be significantly greater for parents who used HPVCF compared to those who did not. However, HPVCF use was associated with a strong trend toward greater initiation of Tdap and MCV vaccines. The reason for this is unclear but a pre-post test period of 5-months may have been too short a duration to determine the influence of HPVCF on parental HPV vaccination behavior. A minimum of 1-year follow-up is recommended for future trials. At baseline, both Tdap and MCV rates were lower among HPVCF users than in the comparison condition but these differences were not statistically significant and likely did not contribute to the results.

Psychosocial determinants of HPV vaccine initiation

Findings on the potential of HPVCF were encouraging. Parents receiving HPVCF demonstrated statistically greater knowledge about HPV and HPV vaccine compared to those who did not receive HPVCF. Parents who received the HPVCF and used it demonstrated significant change in knowledge about HPV and HPV vaccine and perceived effectiveness of the HPV vaccine as well as trends toward significance for parental knowledge about HPV-related disease and perceived norms. This is promising as these changes were demonstrated with only a casual use of HPVCF and in a parent sample already disposed toward vaccination. Knowledge, beliefs in vaccine effectiveness, and perceived norms regarding vaccination are critical determinants of HPV vaccination.Citation15,Citation16 These findings are consistent with the design objectives for the HPVCF that were to address facts regarding HPV and HPV vaccination, to debunk myths, and to increase positive normative perceptions of HPV vaccination. This suggests that HPVCF may provide a time-saving option for overburdened clinical staff by sharing patient instruction. While statistically significant, the change in knowledge and perceived effectiveness was modest and the clinical significance is difficult to determine. These psychosocial improvements appeared to have been insufficient to significantly increase vaccination behavior within the parameters of the study. A longer study period may have provided more definitive information on the influence of these behaviors antecedents.

Significant between-group differences were not observed for intentions to vaccinate, outcome expectations regarding vaccine benefits or risk of HPV infection, perceived susceptibility to contact HPV, perceived barriers to HPV vaccine initiation, perceived future regret in the event of not vaccinating a child, and self-efficacy to discuss HPV with the HCP. It is uncertain what psychosocial change is required to ‘tip’ parental decisional balance toward a decision to vaccinate. Future HPVCF enhancements may target these factors. In previously reported usability testing 17% of parents reported initiating their child’s HPV vaccination because of HPVCF despite infrequent HPVCF use.Citation31

Predictors of HPV vaccine initiation

In a culminating multivariable model a significant association was found between receiving the HPV vaccine and the dependent variables of adopting Tdap and MCV vaccinations, positive change in perceived effectiveness of the HPV vaccine, and reduced perceived barriers to initiating the HPV vaccine. This is supportive of previous studiesCitation22 and reinforces the importance of targeting parental perceptions of HPV vaccine effectiveness and of debunking ‘myths’ about the vaccine. These associations were found irrespective of HPVCF use. The culminating multivariable model did not demonstrate that exposure to HPVCF was a significant predictor of HPV vaccine initiation.

HPVCF use and feasibility

The results obtained from HPVCF are encouraging when considering feasibility of reach and low burden on use (e.g., designed for brief and infrequent use). HPVCF uses minimal branched chain logic and facilitates parents’ self-tailoring. HPVCF use was lower than expected. Only 58.3% of parents in the treatment condition downloaded and used HPVCF. Actual exposure to content was brief. Parents tended to visit once and usually viewed just a few pages. More research is needed to understand reasons for variation in number of pages/activities visited among parents. Typical health app use in the U.S. is at least once per day for up to 10 min,Citation45 though this doesn’t differentiate between apps used to monitor health metrics as well as those used for education.

The HPVCF was described to provide visitors with accurate vaccination information and self-tailored content, using a delivery channel that enables parents to navigate efficiently to the content of most interest. It was designed for casual use, without a prescribed regimen of lessons or modules. A single brief visit could sufficiently ameliorate particular concerns. As such, HPVCF was designed as supplemental to regular care. The theoretical methods and strategies used in the HVPCF include peer and professional testimonials and role modeling and information transfer. More sophisticated approaches to tailoring and readiness profiling could strengthen the intervention approach.

Despite agreement to access HPVCF if assigned to the treatment group and incentives provided after each survey (baseline and 5 mo. follow-up), access by parents in the treatment group was modest (58.3%). Over 40% of parents assigned to the treatment group did not use HPVCF (i.e., did not download it or did not move off the home screen). This suggests that an app may not be the educational channel of choice for all parents and that greater attention may need to be applied to promoting HPVCF. Follow-up requests and more prescriptive directions to parents to download and use the app may have increased its reach within the study. Future research could investigate the most effective ways to promote HPVCF to patients and strategies to make it more appealing (e.g., providing pediatrician and medical assistant training to refer hesitant parents to HPVCF). Despite limitations encountered in study enrollment and retention, use of apps like HPVCF appears to be a feasible channel to convey information to parents when those parents are disposed or motivated to use them. Further investigation of the characteristics of parents most disposed to HPVCF may inform HCPs on which parents will be most receptive to it. This information will also enable enhancement of HPVCF and development of promotional materials to broaden its appeal and attract those not naturally inclined to use it, including hesitant parents who may benefit the most from this supplemental education.

Social media

HPVCF represents one strategy to provide a counterfactual to misinformation provided on social media platforms. mHealth represents a novel channel for persuasive messaging. In this study, a greater percentage of parents in the comparison group reported receiving information from the Internet and social media compared to the treatment condition but the degree to which this information source and associated messaging might influence the impact of HPVCF is unclear. Emergent technology-based approaches to examine social media messaging on vaccination include the application of artificial intelligence and deep learning algorithms to identify, categorize, and remediate on HPV-related misinformation messagesCitation46 and the use of chatbots to intelligently inoculate users against misinformation.Citation47,Citation48 These approaches are the subject of empirical investigation but, unlike phone-based apps, are not widely applied.

Limitations and future studies

These findings need to be interpreted in light of study limitations. The sample included mainly married, college educated, employed, and privately insured parents. Most parents reported receiving their vaccine information from their provider and the Internet and had positive baseline intentions to vaccinate. The number of parents reporting vaccine hesitancy was low and the association between Tdap and MCV vaccination and HPV initiation further supported the finding that most parents were not vaccine resistant and possibly had provided their children with all vaccines at the same visit. Given the favorable disposition of the parents toward vaccination it is possible that a significant between group difference in vaccination behavior may not have been discernable even in a longer trial. However, despite their positive disposition a significant positive change in attitudes was still detected. The sample was representative of the broader clinic parent population and HPVCF appeared to be accepted as a credible resource by these parents. Generalizability of acceptance of HPVCF to other clinic populations with differing SES, ethnicity, and levels of hesitancy is unclear. Future research could profitably be directed to other demographic populations including those who are likely more hesitant. In this regard, there may be added utility in investigating the impact of using HPVCF in the clinic waiting room prior to the clinic encounter to promote parent-provider dialogue and enable providers to capitalize on HPV vaccination proximal to positive parental attitude change. Collectively, these findings suggest that apps like HPVCF could have utility in influencing parents’ attitudes but may not be sufficiently potent if not used adjunctive to the HCP ‘voice’.

Further study limitations include a reduced sample size (from that initially powered to detect change), limited study duration, and uncertain generalizability to other populations. Future app and mHealth studies are indicated to investigate how to reach parents and families and effectively persuade them to initiate HPV vaccination. Such studies can include the impact of enhancements (e.g., tailoring and interactivity), strategies to promote apps for download and ongoing use (“stickiness”), identifying strategies to increase app reach, especially for those most at-risk (or hesitant), and the potential ‘ripple’ effect of longitudinal reach in multi-child families. Future studies can also investigate the impact on HPV vaccine completion rates, which were beyond the scope of the current study.

Conclusion

HPVCF appears to be a feasible adjunct to the education received in usual care visits and may contribute to mitigating the influence of social media misinformation. Future work is indicated to address the issues that HPVCF was not, in itself, a significant influence of HPV vaccine initiation behavior and many parents elected not to use the app even when asked to do so. Results reinforce the value of apps as adjunctive strategies to support the important persuasive voice of the HCP in overcoming parent hesitancy.

Acknowledgement

We extend our deepest appreciation to the patients and clinicians who participated in the development and testing of the HPVcancerFree app and to the support of the Cancer Prevention and Research Institute of Texas (CPRIT).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. How many cancers are linked with HPV each year? [accessed 2021 Feb 12]. https://www.cdc.gov/cancer/hpv/statistics/cases.html.

- Drolet M, Benard E, Perez N, Brisson M, Hpvvis G, Boily M-C, Baldo V, Brassard P, Brotherton JML, Callander D. Population-Level impact and herd effects following the introduction of human papillomavirus vaccination programmes: updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2019;394(10197):1–13. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(19)30298-3.

- Elam-Evans LD, Yankey D, Singleton JA, Sterrett N, Markowitz LE, Williams CL, Fredua B, McNamara L, Stokley S. National, regional, state, and selected local area vaccination coverage among adolescents aged 13–17 years — United States, 2019. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69(33):1109–1116. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm6933a1.

- Lei J, Ploner A, Elfstrom KM, Wang J, Roth A, Fang F, Sundström K, Dillner J, Sparén P. HPV vaccination and the risk of invasive cervical cancer. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(14):1340–1348. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1917338.

- Hildesheim A, Herrero R, Wacholder S, Rodriguez AC, Solomon D, Bratti MC, Schiller JT, Gonzalez P, Dubin G, Porras C. Effect of human papillomavirus 16/18 L1 viruslike particle vaccine among young women with preexisting infection: a randomized trial. JAMA. 2007;298(7):743–753. doi:10.1001/jama.298.7.743.

- Leval A, Herweijer E, Ploner A, Eloranta S, Fridman Simard J, Dillner J, Young C, Netterlid E, Sparén P, Arnheim-Dahlström L. Quadrivalent human papillomavirus vaccine effectiveness: a Swedish national cohort study. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2013;105(7):469–474. doi:10.1093/jnci/djt032.

- Ali H, Guy RJ, Wand H, Read TR, Regan DG, Grulich AE, Fairley CK, Donovan B. Decline in in-patient treatments of genital warts among young Australians following the national HPV vaccination program. BMC Infect Dis. 2013;13(1):140. doi:10.1186/1471-2334-13-140.

- Giuliano AR, Lazcano-Ponce E, Villa L, Nolan T, Marchant C, Radley D, Golm G, McCarroll K, Yu J, Esser M. Impact of baseline covariates on the immunogenicity of a quadrivalent (types 6, 11, 16, and 18) human papillomavirus virus-like-particle vaccine. J Infect Dis. 2007;196(8):1153–1162. doi:10.1086/521679.

- Smulian EA, Mitchell KR, Stokley, Stokley S. Interventions to increase HPV vaccination coverage: a systematic review. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2016;12(6):1566–1588. doi:10.1080/21645515.2015.1125055.

- Khodadadi AB, Redden DT, Scarinci IC. HPV vaccination hesitancy among latina immigrant mothers despite physician recommendation. Ethn Dis. 2020;30(4):661–670. doi:10.18865/ed.30.4.661.

- Nguyen KH, Santibanez TA, Stokley S, Lindley MC, Fisher A, Kim D, Greby S, Srivastav A, Singleton J. Parental vaccine hesitancy and its association with adolescent HPV vaccination. Vaccine. 2021;39(17):2416–2423. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2021.03.048.

- Tsui J, Vincent A, Anuforo B, Btoush R, Crabtree BF. Understanding primary care physician perspectives on recommending HPV vaccination and addressing vaccine hesitancy. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2021;17(7):1961–1967. doi:10.1080/21645515.2020.1854603.

- Vadaparampil ST, Kahn JA, Salmon D, Lee J-H, Quinn GP, Roetzheim R, Bruder K, Malo TL, Proveaux T, Zhao X. Missed clinical opportunities: provider recommendations for HPV vaccination for 11–12 year old girls are limited. Vaccine. 2011;29(47):8634–8641. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.09.006.

- Rand CM, Shone LP, Albertin C, Auinger P, Klein JD, Szilagyi PG. National health care visit patterns of adolescents: implications for delivery of new adolescent vaccines. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2007;161(3):252–259. doi:10.1001/archpedi.161.3.252.

- Beavis A, Krakow M, Levinson K, Rositch AF. Reasons for lack of HPV vaccine initiation in NIS-teen over time: shifting the focus from gender and sexuality to necessity and safety. J Adolesc Health. 2018;63(5):652–656. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2018.06.024.

- Gidengil C, Chen C, Parker AM, Nowak S, Matthews L. Beliefs around childhood vaccines in the United States: a systematic review. Vaccine. 2019;37(45):6793–6802. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2019.08.068.

- Rodriguez SA, Mullen PD, Lopez DM, Savas LS, Fernandez ME. Factors associated with adolescent HPV vaccination in the US: a systematic review of reviews and multilevel framework to inform intervention development. Prev Med. 2020;131:105968. doi:10.1016/j.ypmed.2019.105968.

- Head KJ, Biederman E, Sturm LA, Zimet GD. A retrospective and prospective look at strategies to increase adolescent HPV vaccine uptake in the United States. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2018;14(7):1626–1635. doi:10.1080/21645515.2018.1430539.

- Cataldi JR, O’Leary ST, Markowitz LE, Allison MA, Crane LA, Hurley LP, Brtnikova M, Beaty BL, Gorman C, Meites E. Changes in strength of recommendation and perceived barriers to human papillomavirus vaccination: longitudinal analysis of primary care physicians, 2008-2018. J Pediatr. 2021;234:149–157 e143. doi:10.1016/j.jpeds.2021.03.002.

- Walker KK, Owens H, Zimet G. “We fear the unknown”: emergence, route and transfer of hesitancy and misinformation among HPV vaccine accepting mothers. Prev Med Rep. 2020;20:101240. doi:10.1016/j.pmedr.2020.101240.

- Lama Y, Quinn SC, Nan X, Cruz-Cano R. Social media use and human papillomavirus awareness and knowledge among adults with children in the household: examining the role of race, ethnicity, and gender. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2021;17(4):1014–1024. doi:10.1080/21645515.2020.1824498.

- Ortiz RR, Smith A, Coyne-Beasley T. A systematic literature review to examine the potential for social media to impact HPV vaccine uptake and awareness, knowledge, and attitudes about HPV and HPV vaccination. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2019;15(7–8):1465–1475. doi:10.1080/21645515.2019.1581543.

- de Cock C, van Velthoven M, Milne-Ives M, Mooney M, Meinert E. Use of apps to promote childhood vaccination: systematic review. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2020;8(5):e17371. doi:10.2196/17371.

- Texas Department of State Health Services, Texas Health Steps. Adolescent health. A guide for providers. 2011 [accessed 2014 Mar 1].

- Thompson DM, Fernald DH, Mold JW. Intraclass correlation coefficients typical of cluster-randomized studies: estimates from the Robert Wood Johnson prescription for health projects. Ann Fam Med. 2012;10(3):235–240. doi:10.1370/afm.1347.

- Dixon BE, Zimet GD, Xiao S, Tu W, Lindsay B, Church A, Downs SM. An educational intervention to improve HPV vaccination: a cluster randomized trial. Pediatrics. 2019;143(1):e20181457. doi:10.1542/peds.2018-1457.

- Creanor S, Lloyd J, Hillsdon M, Dean S, Green C, Taylor RS, Ryan E, Wyatt K. Detailed statistical analysis plan for a cluster randomised controlled trial of the healthy lifestyles programme (HeLP), a novel school-based intervention to prevent obesity in school children. Trials. 2016;17(1):599. doi:10.1186/s13063-016-1737-y.

- Hemming K, Marsh J. A menu-driven facility for sample-size calculations in cluster randomized controlled trials. Stata J. 2013;13(1):114–135. doi:10.1177/1536867X1301300109.

- Becker ERB, Shegog R, Savas SS, Frost EL, Healy CM, Spinner SW, Vernon SW. Informing content and feature design of a parent-focused HPV vaccination digital behavior change intervention: synchronous text-based focus groups. JMIR Formative Res. 2021;5(11):e28846. doi:10.2196/28846.

- Becker ERB, Myneni S, Shegog R, Fujimoto K, Savas LS, Frost EL, Healy CM, Spinner S, Vernon SW. Parent engagement with a self-tailored cancer prevention digital behavior change intervention: exploratory application of affiliation network analysis. MedInfo. In press.

- Becker ERB, Shegog R, Savas LS, Frost EL, Coan SP, Healy CM, Spinner SW, Vernon SW. Parents experience with an mHealth intervention to influence HPV vaccination decision-making: mixed methods study. JMIR Pediatr Parent. 2022;5(1):e30340. PMID: 35188469. doi:10.2196/30340.

- Bartholomew Eldredge LK, Markham CM, Ruiter RAC, Fernandez ME, Kok G, Parcel GS. Planning health promotion programs: an intervention mapping approach. 4th ed. San Francisco (CA): Jossey-Bass; 2016.

- Hochbaum GM. Public participation in medical screening programs: a socio-psychological study. Washington (DC): U.S. Department of Health, Education, and Welfare; 1958.

- Bandura A. Human agency in social cognitive theory. Am Psychol. 1989;44(9):1175–1184. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.44.9.1175.

- Fishbein M. A reasoned action approach to health promotion. Med Decis Making. 2008;28(6):834–844. doi:10.1177/0272989X08326092.

- Perez S, Tatar O, Ostini R, Shapiro GK, Waller J, Zimet G, Rosberger Z. Extending and validating a human papillomavirus (HPV) knowledge measure in a national sample of Canadian parents of boys. Prev Med. 2016;91:43–49. doi:10.1016/j.ypmed.2016.07.017.

- McRee AL, Brewer NT, Reiter PL, Gottlieb SL, Smith JS. The Carolina HPV immunization attitudes and beliefs scale (CHIAS): scale development and associations with intentions to vaccinate. Sex Transm Dis. 2010;37(4):234–239. doi:10.1097/OLQ.0b013e3181c37e15.

- Reiter PL, Brewer NT, Gottlieb SL, McRee AL, Smith JS. Parents’ health beliefs and HPV vaccination of their adolescent daughters. Soc Sci Med. 2009;69(3):475–480. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.05.024.

- Dempsey AF, Butchart A, Singer D, Clark S, Davis M. Factors associated with parental intentions for male human papillomavirus vaccination: results of a national survey. Sex Transm Dis. 2011;38(8):769–776. doi:10.1097/OLQ.0b013e318211c248.

- Vernon SW, Savas LS, Shegog R, Healy CM, Frost EL, Coan SP, Gabay EK, Preston SM, Crawford CA, Spinner SW. Increasing HPV vaccination in a network of pediatric clinics using a multi-component approach. J Appl Res Child. 2019;10(2):8. PMC7416872.

- Stata Statistical Software: Release 16 [ computer program]. College Station (TX): StataCorp LP; 2019.

- Goesling B. A practical guide to cluster randomized trials in school health research. J Sch Health. 2019;89(11):916–925. doi:10.1111/josh.12826.

- Hosmer DW, Lemeshow S. Applied logistic regression. 2nd ed. New York (NY): John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; 2000.

- Crawford CA, Shegog R, Savas LS, Frost EL, Healy CM, Coan SP, Gabay EK, Spinner SW, Vernon SW. Using intervention mapping to develop an efficacious multicomponent systems-based intervention to increase human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccination in a large urban pediatric clinic network. J Appl Res Children Informing Policy Children Risk. 2020;10(2):Article 9. PMCID: 7386427.

- Krebs P, Duncan DT. Health app use among US mobile phone owners: a national survey. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2015;3(4):e101. doi:10.2196/mhealth.4924.

- Du J, Preston SM, Sun H, Shegog R, Cunningham RM, Boom JA, Savas LS, Amith M, Tao C. Utilizing machine learning-based approaches for the detection and classification of human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine misinformation: infodemiology study of reddit discussions. JMIR. 2021;23(8):e26478.

- Nurzhynska A. Pros and cons of chatbot counselling for vaccine hesitancy. [accessed 2021 May 13]. https://www.comminit.com/content/pros-and-cons-chatbot-counselling-vaccine-hesitancy.

- Ferrand J, Hockensmith R, Houghton RF, Walsh-Buhi ER. Evaluating smart assistant responses for accuracy and misinformation regarding human papillomavirus vaccination: content analysis study. J Med Internet Res. 2020;22(8):e19018. doi:10.2196/19018.