ABSTRACT

Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) is a global pandemic caused by the SARS-CoV-2 virus. COVID-19 vaccine is the best strategy for prevention. However, it remained the main challenge. Therefore, this systematic review and meta-analysis aimed to determine the overall pooled estimate of COVID-19 vaccine acceptance and its predictors in Ethiopia. Consequently, we have searched articles from PubMed, EMBASE, Web of Science, Google Scholar, reference lists of included studies, and Ethiopian universities’ research repository. The weighted inverse variance random effects model was employed. The quality of studies and the overall variation between studies were checked through Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) quality appraisal criteria and heterogeneity test (I2), respectively. The funnel plot and Egger’s regression test were also conducted. Following that, a total of 14 studies with 6,773 participants were considered in the study and the overall pooled proportion of COVID-19 vaccine acceptance was 51.2% (95% CI: 43.9, 58.5). Having good knowledge (Odds ratio: 2.7; 95% CI: 1.1, 7.1; P.value: 0.00), chronic disease (Odds ratio: 2; 95% CI: 1.3, 3.1), older age (Odds ratio: 1.8; 95% CI: 1.1, 3.0; P.value: 0.02), and secondary education and above (Odds ratio: 3.3; 95% CI: 1.7, 6.7; P.value: 0.00) were significantly associated with the acceptance of COVID-19 vaccine. In conclusion, Having good knowledge, chronic disease, older age, and secondary education and above were significantly associated with COVID-19 vaccine acceptance. Therefore, special attention and a strengthened awareness, education, and training about COVID-19 vaccine benefits had to be given to uneducated segments of the population.

KEYWORDS:

Introduction

Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) is a global pandemic and an infectious disease caused by the SARS-CoV-2 virus. It is very contagious with a fast-spreading rate in every part of the world.Citation1,Citation2 To mitigate the crisis of this pandemic problem, several prevention strategies have been recommended by World Health Organization and adopted by the government of Ethiopia. These were, washing hands frequently with soap, maintaining social distancing, stay informed and following advice given by health care providers, staying at home if you begin to feel sick and if you develop cough or fever or experiences difficulty of breathing, seek medical advice and call to the center assigned for COVID-19 response.Citation3 But, these prevention measures had not been strictly followed and the magnitude of COVID-19 remained high.

Many countries made a remarkable effort to produce a vaccine for the prevention of COVID-19 starting from the occurrence of COVID-19 in December 2019. With many trials, an effective COVID-19 vaccine has been developed. By 11 December 2020, the Pfizer vaccine became the first to receive emergency use authorization from the Food and Drug Administration (FDA).Citation4 However, the acceptance rate was low. Globally, a scoping review showed that the average rate of vaccine hesitancy in April 2020 was 21%, which increased to 36% in July 2020 and later declined to 16% in October 2020.Citation5 Another global survey on 19 countries about the acceptance of the COVID-19 vaccine revealed that only 71.5% of the respondents would consider taking a COVID-19 vaccine and only 48.1% of them would take it if their organization recommends the vaccine.Citation6 According to other several systematic reviews and meta-analysis studies report, the COVID-19 acceptance rate was 73.31% in the world,Citation7 and (48.93%) in Africa.Citation8

Many studies have identified the key predictors of COVID-10 vaccine acceptance and reported several factors that would affect the outcome variable including, age,Citation5,Citation8−Citation10 educational level,Citation5,Citation7,Citation10 Occupation,Citation5 Gender,Citation5,Citation11 knowledge,Citation11 having a chronic disease,Citation11,Citation12 and residence.Citation13

Even though much hesitancy, by October 2021, healthcare workers had delivered more than 7 billion doses of the COVID-19 vaccine globally.Citation14 Whereas in Ethiopia, on 16 November 2021, the Federal Ministry of Health (MoH) launched a COVID-19 vaccination campaign aiming to vaccinate people aged 12 years and above. Consequently, the Ministry has deployed over 28,000 vaccinators and more than 6.2 million doses of COVID-19 vaccines for the campaign, namely, Sinopharm, AstraZeneca, Johnson & Johnson/Janssen, and Pfizer-BioNTech.Citation15 But, still, the number of COVID-19 cases and deaths are rising alarmingly in Ethiopia and this is mainly due to unwillingness to receive the COVID-19 vaccine. Therefore, this study aimed to estimate the overall pooled acceptance rate of the COVID-19 vaccine and its predictors in Ethiopia.

Objective

The main aim of this study was to estimate the overall pooled estimate of COVID-19 Vaccine acceptance and its predictors among adult populations in Ethiopia, 2021.

Method

Reporting

The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) guideline and protocol have been used for reporting the study findings (Supplemental file 1).

Databases and searching strategies

All potential articles and papers were retrieved from the electronic databases (PubMed, Google Scholar, EMBASE, and the Web of Sciences) and other sources (searching from the reference lists of the included studies and the Ethiopian institutional research repositories). Article searching was conducted using searching terms and strings. We used the following searching terms including, “COVID-19,” “Coronavirus,” “Pandemic,” “SARSE COVID-2,” “Highly contagious disease,” “Vaccine,” “Immunization,” “Preventive measures,” “COVID-19 vaccine,” “Acceptance,” “Willingness,” “Intention,” “COVID-19 vaccine acceptance,” “COVID-19 vaccine willingness,” “COVID-19 vaccine intention,” “Populations,” “Adults,” “Health workers,” “Predictors,” “Factors,” “Barriers,” “Risk factors,” “Prevalence,” “Proportion,” and “Ethiopia.” The search string was developed using “AND” and “OR” Boolean operators. Articles were searched from November 15 to December 10/2021. For PubMed searching we have used this searching formulation: ((COVID-19) OR (Corona virus [MeSH Terms]) OR (Pandemic) OR (SARSE COVID-2 [MeSH Terms]) OR (Highly contagious disease) AND (Vaccine) OR (Immunization [MeSH Terms]) OR (preventive measures) OR (COVID-19 vaccine[MeSH Terms]) OR (Acceptance) OR (Willingness [MeSH Terms]) OR (Intention) OR (COVID-19 vaccine acceptance[MeSH Terms]) OR (COVID-19 vaccine willingness [MeSH Terms]) OR (COVID-19 vaccine intention) AND (Populations) OR (Adults [MeSH Terms]) AND (predictors) OR (risk factors[MeSH Terms]) OR (associated factors) OR (Barriers[MeSH Terms]) AND (Prevalence) OR (Proportion[MeSH Terms]) AND (Ethiopia)).

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Inclusion criteria

In this study, observational studies (cross-sectional, case-control, and cohort), published articles at any time in the English language, conducted in Ethiopia, and studies reported extractable data that helps to compute the odds ratio of predictors were included.

Exclusion criteria

Abstracts, studies without full texts, conference papers, editorials, letters, protocols, program evaluation reports, systematic reviews, trials, and qualitative studies were excluded from this study. In addition, studies with a high risk of bias or scored less than 50% on the critical appraisal checklist were excluded.

Outcome measurement

COVID-19 vaccine acceptance: For a question of “Did you have an intention to accept COVID-19 vaccine if it is available in the future?” respondents who respond “yes” will score 1 and “No” response will earn zero scores. Accordingly, respondents who scored 1 were thought of as having the intention to accept the COVID-19 vaccine, and respondents who scored 0 were thought of as having no intention to accept the COVID-19 vaccine.Citation16

Study screening and selection

Primarily, all articles found from the databases were imported to EndNote version 7 citation manager, and duplicates of articles were checked and removed systematically. Secondly, four independent authors (GMB, KAA, NTA, and CAW) have screened and reviewed the title and abstract. The variation among the authors was solved with discussion, communication, and repeating the procedures. Additionally, these authors have reviewed the full text and extracted the relevant data from the articles which fulfilled the inclusion criteria. The first author of the article, year of publication, study area, region, design, population, and sample size, the proportion of COVID-19 vaccine acceptance, predictors, and data used to compute the odds ratio of predictors were extracted carefully on an Excel spreadsheet. The difference among investigators was also solved by revising the procedures and reaching a consensus. Finally, after calculating the standard error and logarithm of proportion (log p), the data were exported to STATA version 11 for further analysis.

Quality assessment

Three independent authors (GMB, KAA, and SFK) assessed the quality of the studies using the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) quality appraisal checklist.Citation17,Citation59 All the included studies were cross-sectional. Therefore, the JBI critical appraisal checklist for analytical cross-sectional studies was employed (Supplemental file 2). Any difference among reviewers was also solved by repeating the procedures.

Data synthesis

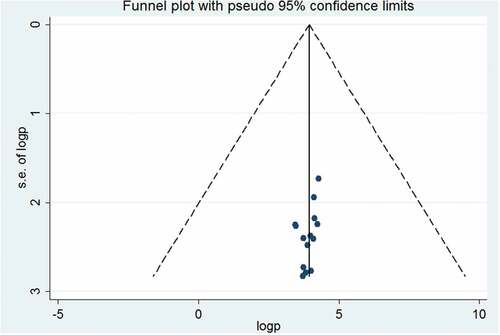

To determine the overall pooled proportion of COVID-19 vaccine acceptance and its predictors among adult populations, a weighted inverse variance random effects model was used. The publication bias of the articles was checked by visual inspection of the funnel plot and conducting Egger’s regression test. The total percentage of variations between studies due to heterogeneity was assessed by I2 statistics.Citation20 The values of I2, 25%, 50%, and 75% represent low, moderate, and high heterogeneity, respectively.Citation20 After checking and managing the publication bias, the overall pooled proportion of COVID-19 vaccine acceptance and the odds ratio of its predictors were determined. In addition, the proportion was also determined by region and study participants. Next, the data from the cross-tabulation of the studies were taken and transferred to an Excel spreadsheet to compute the odds ratio of the predictors. Then, the extracted data was exported from an excel spreadsheet to STATA version 11 for analysis. Finally, the PRISMA guideline was used for reporting.Citation21

Result

Search results

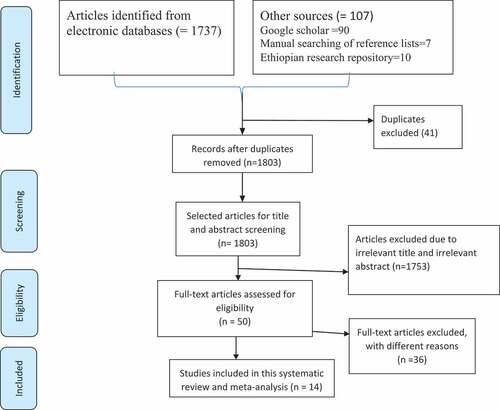

1844 articles were found in the databases including, 1725 from PubMed, 90 from Google Scholar, 8 from EMBASES, 4 from Web of sciences, 10 from Ethiopian universities’ research repositories, and 7 from the reference lists of included studies. While a total of 1830 articles were excluded due to various reasons. For instance, 41 articles were removed because of duplicates, 1753 due to irrelevant titles and abstracts, 5 due to the study designs, and 31 due to study areas. Finally, 14 articles were included in the study ().

Characteristics of studies

In this study, a total of 14 articlesCitation13,Citation16−Citation18,Citation22−Citation32 with a sample size of 6,773 study participants were included in the analysis. All of the studies were published and cross-sectional. The majority of the studies (6 articles)Citation18,Citation22,Citation26,Citation28,Citation30,Citation32 were conducted in the Amhara region, four from South nation nationalities and people regional states,Citation13,Citation16,Citation23,Citation29 one from Oromia,Citation25 and the remaining two studies were conducted through an online survey by sending the questionnaire through e-mail, telegram and other means of communication for those who able to access the internet.Citation24,Citation27 A detailed description of the studies were found in ().

Table 1. Characteristics of studies included in this systematic review and meta-analysis.

Quality of the studies

The quality of all included studiesCitation13,Citation16,Citation18–22–Citation32 was assessed using the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) quality appraisal checklist for cross-sectional studies. After assessment by independent reviewers, all studies which scored above 50% were considered in the current study.

Meta-analysis

The publication bias of the studies was checked through the funnel plot and Egger's regression test. Consequently, publication bias was not observed as the funnel plot revealed a symmetrical distribution of articles on the graph, and also Eger’s regression test was 0.075 ().

COVID-19 vaccine acceptance

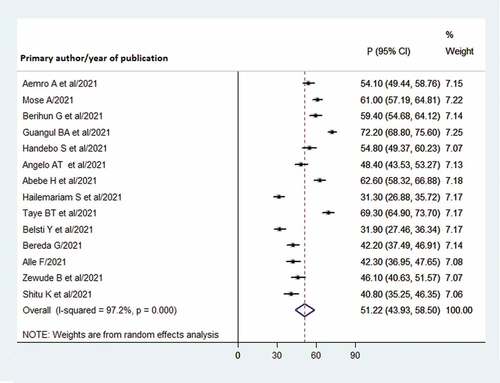

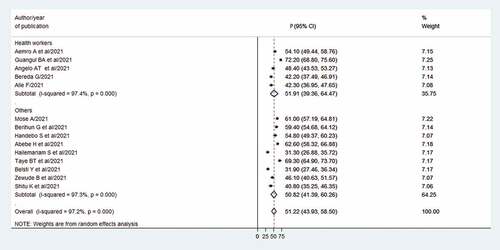

In this study, a total of 14 studiesCitation13–16–Citation18–22–Citation32 with 6,773 participants were incorporated to compute the pooled estimate. Consequently, the overall pooled proportion of COVID-19 vaccine acceptance in Ethiopia was 51.2% (95% CI: 43.9, 58.5) ().

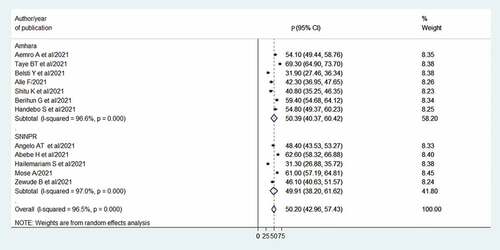

Sub-group analysis by region

To determine the regional variation of COVID-19 vaccine acceptance, sub-group analysis by region was conducted. We have done a subgroup analysis on the region (Amhara and South nation, nationalities, and people of regional states) those having two or more articles consequently, in the Amhara region, the overall pooled estimate of COVID-19 vaccine acceptance was 50.4% (95% CI: 40.4, 60.4) and in South nation, nationalities, and people of regional states was 49.9% (95% CI: 38.2, 61.6) ().

Sub-group analysis by study participants

In this study, subgroup analysis was also done by study participants (health workers versus non-health workers/other occupations). Hence, COVID-19 vaccine acceptance among health workers was slightly higher 51.9% (95% CI: 39.4, 64.5) than in other occupations 50.8% (95% CI: 41.4, 60.3) ().

Predictors of COVID-19 vaccine acceptance

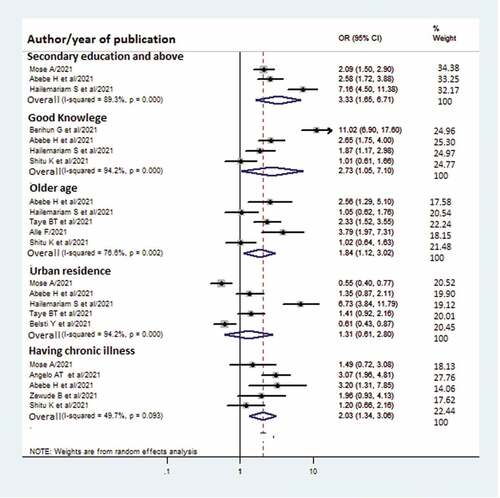

As indicated in (), predictors of COVID-19 vaccine acceptance were identified. These were having good knowledge, a having chronic disease, older age, and secondary education and above. Regarding secondary education and above, three studiesCitation13,Citation16,Citation29 were reporting extractable data that helps to compute the pooled odds ratio. All of these studies revealed a significant association and a pooled odds ratio has been computed and its overall odds ratio was (OR: 3.3; 95% CI: 1.7, 6.7; P.Value: 0.00).

About four studiesCitation13,Citation16,Citation26,Citation30 had reported data on knowledge status of which, three of themCitation13,Citation16,Citation26 showed a significant association with COVID-19 vaccine acceptance. Following that a pooled odds ratio was computed (OR: 2.73; 95% CI: 1.05, 7.10; P.Value: 0.00) and revealed a significant association with the outcome variable.

Five of the included studies,Citation13,Citation16,Citation24,Citation29,Citation32 had reported extractable data for determining the relationship between residence and the outcome variable. In four of the studies,Citation16,Citation24,Citation29,Citation32 the residence was not significantly associated with COVID-19 vaccine acceptance. Whereas, one of the studies,Citation13 showed a significant association with the outcome variable. Consequently, the overall pooled odds ratio (OR: 1.31; 95%CI: 0.61, 2.80) indicated that residence was not significantly associated with COVID-19 vaccine acceptance.

Moreover, data were also taken from the five studiesCitation16,Citation23,Citation29–31 and two of them showed having a chronic illness was significantly associated with COVID-19 vaccine acceptance,Citation16,Citation23 However, three studies Citation29–31 reported as it had no association. Besides, the overall odds ratio indicated chronic illness was significantly associated with the outcome variable (OR: 2.03; 95% CI: 1.34, 3.06).

Finally, the age of the study participants was also extracted from five studiesCitation13,Citation16,Citation18,Citation30,Citation32 in which three of the study reported older age (>46 years) as a significant factor,Citation16,Citation18,Citation32 but in the two studies, not revealed any association.Citation13,Citation30 In the meta-analysis, being older age had increased the COVID-19 vaccine acceptance (1.84; 95% CI: 1.12, 3.02).

Discussion

COVID-19 vaccine is the best strategy to prevent the spread of COVID-19 globally. Willingness to receive the COVID-19 vaccine has a paramount effect to mitigate COVID-19.

The finding of this study (51.2% (95% CI: 43.9, 58.5)) was in line with the study conducted in Africa (48.93%),Citation8 Kuwait (53.1%),Citation33 and Saudi Arabia (51.95%).Citation34 However, lower than from a worldwide study ranged from (66.01–71%),Citation9,Citation35,Citation36 Arab (62.4%),Citation37 Pakistan (70.2%),Citation38 Malaysia (93.2%),Citation39 Australia (96.4%), China (95.3%) and Norway (95.3%).Citation40 In Ethiopia, nearly half of the people believed that the COVID-19 vaccine would worsen the preexisting diseases as well as it could cause COVID-19 infection.Citation41 In addition, Ethiopia has strong cultural and religious perceptions that the diseases do not affect the young populations. And also they have no trust on COVID-19 prevention measures and this lead to a low COVID-19 vaccine acceptance rate in Ethiopia.Citation42 On the other hand, the result of the current study was higher than a study conducted in Japan (34.6%),Citation40 the U.S. (29.4%),Citation40 Morocco (26.9%),Citation43 Iran (27.9%)Citation40 and Jordan (36.8).Citation44

This systematic review and meta-analysis revealed that having good knowledge about the COVID-19 vaccine increases the acceptance rate of the vaccine. Consequently, the odds of COVID-19 vaccine acceptance among individuals who had good knowledge were 2.7 times more likely than those with poor knowledge. This finding was supported by a global systematic review and meta-analysis,Citation45 and a Jordan study.Citation44 This was mainly due to people with high knowledge about COVID-19 and its vaccine would know very well about the bad consequences of COVID-19 and the greatest benefit of the vaccine.Citation46–49

This study also determined the association between age and COVID-19 vaccine acceptance. Following that, COVID-19 vaccine acceptance was 1.8 times more likely in older people (>46 years) than in the lower age groups and this was consistent with a study conducted in the globe,Citation45 Nigeria,Citation50 Saudi Arabia,Citation34 and Ethiopia.Citation51 As evidenced by various studies, older age groups were highly vulnerable to COVID-19 and even it was very severe in these groups.Citation52,Citation53 As a result, willingness to receive the COVID-19 vaccine among those groups was high.Citation54–56

Regarding chronic diseases, even though various studies revealed inconsistent results about the association between people having chronic diseases and COVID-19 vaccine acceptance, the current study showed a positive association. Eventually, the odds of accepting the COVID-19 vaccine were 2 times more likely among people with chronic diseases than their counterparts. This result was in agreement with a study employed around the globe,Citation45 Saudi Arabia,Citation34 and Japan.Citation56 Comorbidities increased the morbidity and mortality of people with COVID-19, for instance, patients with preexisting cardiovascular disease, coronary heart diseases, and hypertension were at a high risk of developing fatal COVID-19 disease.Citation57,Citation58 In addition, Hyperglycemia and altered immune function aggravate the severity of COVID-19 infection.Citation59

Furthermore, this study indicated that COVID-19 vaccine acceptance was high in people with secondary education and above. Hence, the odds of accepting the COVID-19 vaccine among people with secondary education and above were 3.3 times more likely than people with lower education. This finding was congruent with a systematic review and meta-analysis study conducted globally,Citation45 and in Saudi Arabia.Citation34 This was mainly because, people with high education levels would have high knowledge about COVID-19 and its vaccine. The study had some limitations. First, as the search strategy was limited to the English language, reporting bias was evident. Second, relevant predictors might be missed. Hence, future researchers should consider other factors of COVID-19 vaccine acceptance. Third, the presence of heterogeneity could be attributed to differences in sample sizes of individual studies as a result we have used a random effects model for meta-analysis; and fifth, since some regions did not report data on COVID-19 vaccine acceptance, the results of the study were not a representative for all regions in Ethiopia. In conclusion, about half of the people in Ethiopia did not show a willingness to receive the COVID-19 vaccine and it was low according to the global estimation. This study also revealed that having good knowledge, older age, having chronic diseases, and secondary education and above were significantly associated with the outcome variable. Hence, detailed and deep information about the COVID-19 vaccine and the disease itself better is be given to the general population. Moreover, special attention has to be given to people with low education level.

Abbreviations

AOR Adjusted Odds Ratio

CI Confidence Interval

COVID-19 Corona Virus Disease 2019

JBI Joanna Briggs Institute

OR Odds Ratio

SNNPRS South Nation, Nationalities People Regional State

WHO World Health Organization

Author’s contributions

Getaneh Mulualem Belay conceived and designed the study. All authors established the search strategy, extracted the data, assessed the quality of included studies, did the analysis, wrote the review, and prepared the manuscript. Finally, the authors read, modified, and agreed on the final prepared manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethics approval and consent to participate are not applicable since we used already previously done research.

Supplemental Material

Download Zip (667.5 KB)Acknowledgements

Our special gratitude goes to the authors of included studies who helped us to do this systematic review and meta-analysis.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

All data generated or analyzed during study are included in this systematic review and meta-analysis.

Supplemental data

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed on the publisher’s website at https://doi.org/10.1080/21645515.2022.2114699

Additional information

Funding

References

- World Health Organization. Corona virus diseases. 2021.

- Galal S. Number of coronavirus (COVID-19) deaths in the African continent as of November 22, 2021, by country. 2021.

- Baye K. COVID-19 prevention measures in Ethiopia: current realities and prospects. International Food Policy Research Institute. 2020.

- Solis-Moreira J. How did we develop a COVID-19 vaccine so quickly? 2021.

- Joshi A, Kaur M, Kaur R, Grover A, Nash D, El-Mohandes A. Predictors of COVID-19 vaccine acceptance, intention, and hesitancy: a scoping review. Front Public Health. 2021;9. doi:10.3389/fpubh.2021.698111.

- Lazarus JV, Ratzan SC, Palayew A, Gostin LO, Larson HJ, Rabin K, Kimball S, El-Mohandes A. A global survey of potential acceptance of a covid-19 vaccine. Nat Med. 2021;27(2):1–9. doi:10.1038/s41591-020-1124-9.

- Wang Q, Yang L, Jin H, Lin L. Vaccination against COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis of acceptability and its predictors. Prev Med. 2021;150:106694. doi:10.1016/j.ypmed.2021.106694.

- Wake AD. The acceptance rate toward COVID-19 vaccine in Africa: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Glob Pediatr Health. 2021;8:2333794X211048738. doi:10.1177/2333794X211048738.

- Nehal KR, Steendam LM, Campos Ponce M, van der Hoeven M, Smit GSA. Worldwide vaccination willingness for COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Vaccines. 2021;9(10):1071. doi:10.3390/vaccines9101071.

- Faturohman T, Kengsiswoyo GAN, Harapan H, Zailani S, Rahadi RA, Arief NN. Factors influencing COVID-19 vaccine acceptance in Indonesia: an adoption of technology acceptance model. F1000Research. 2021;10(476):476. doi:10.12688/f1000research.53506.1.

- Bono SA, Faria de Moura Villela E, Siau CS, Chen WS, Pengpid S, Hasan MT, Sessou P, Ditekemena JD, Amodan BO, Hosseinipour MC, et al. Factors affecting COVID-19 vaccine acceptance: an international survey among low- and middle-income countries. Vaccines. 2021;9(5):515. doi:10.3390/vaccines9050515.

- Kamal A-<-C-S-$-A-I, Sarkar T, Khan MM, Roy SK, Khan SH, Hasan SM, Hossain MS, Dell CA, Seale H, Islam M Factors affecting willingness to receive covid-19 vaccine among adults: a cross-sectional study in bangladesh. J Health Manag. 2021;23(3):09735984211050691.

- Hailemariam S, Mekonnen B, Shifera N, Endalkachew B, Asnake M, Assefa A, Qanche Q. Predictors of pregnant women’s intention to vaccinate against coronavirus disease 2019: a facility-based cross-sectional study in southwest Ethiopia. Sage Open Med. 2021;9:20503121211038454. doi:10.1177/20503121211038454.

- Felter C. Identifying and addressing social determinants of learning during the COVID-19 pandemic. 2021.

- WHO. Ethiopia launches a COVID-19 vaccination campaign targeting the 12 years and above population. 2021.

- Abebe H, Shitu S, Mose A. Understanding of COVID-19 vaccine knowledge, attitude, acceptance, and determinates of COVID-19 vaccine acceptance among adult population in Ethiopia. Infect Drug Resist. 2021;14:2015. doi:10.2147/IDR.S312116.

- Joanna Briggs Institute. Critical appraisal tools. 2017.

- Fentie Alle KEO Y. Attitude and associated factors of COVID-19 vaccine acceptance among health professionals in Debre Tabor Comprehensive Specialized Hospital, North Central Ethiopia; 2021: crosssectional study. Indian Virological Society. 2021;32(2):272-278. doi:10.1007/s13337-021-00708-0.

- DerSimonian R, Kacker R. Random-Effects model for meta-analysis of clinical trials: an update. Contemp Clin Trials. 2007;28(2):105–114. doi:10.1016/j.cct.2006.04.004.

- Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. Bmj. 2003;327(7414):557–560. doi:10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557.

- Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, Mulrow C, Gøtzsche PC, Ioannidis JP, Clarke M, Devereaux PJ, Kleijnen J, Moher D, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7):e1000100. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1000100.

- Aemro A, Amare NS, Shetie B, Chekol B, Wassie M. Determinants of COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy among health care workers in Amhara region referral hospitals, Northwest Ethiopia: a cross-sectional study. Epidemiol Infect. 2021;149. doi:10.1017/S0950268821002259.

- Angelo AT, Alemayehu DS, Dachew AM, Villar LM. Health care workers intention to accept COVID-19 vaccine and associated factors in southwestern Ethiopia, 2021. PloS One. 2021;16(9):e0257109. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0257109.

- Belsti Y, Gela YY, Akalu Y, Dagnew B, Getnet M, Seid MA, Diress M, Yeshaw Y, Fekadu SA. Willingness of Ethiopian population to receive COVID-19 vaccine. J Multidiscip Healthc. 2021;14:1233. doi:10.2147/JMDH.S312637.

- Bereda G. Enthusiasm to acceptance of SARS_COV_2 vaccine among health care workers in Oromia Regional State, Ethiopia. An Online Based Cross-Sectional Study, 2021. 2021.

- Berihun G, Walle Z, Berhanu L, Teshome D. Acceptance of COVID-19 vaccine and determinant factors among patients with chronic disease visiting Dessie comprehensive specialized hospital, Northeastern Ethiopia. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2021;15:1795. doi:10.2147/PPA.S324564.

- Guangul BA, Georgescu G, Osman M, Reece R, Derso Z, Bahiru A, Azeze ZB. Healthcare workers attitude towards SARS-COVID-2 vaccine, Ethiopia. Glob J Infect Dis Clin Res. 2021;7(1):043–8.

- Handebo S, Wolde M, Shitu K, Kassie A, Wang Z. Determinant of intention to receive COVID-19 vaccine among school teachers in Gondar City, Northwest Ethiopia. PloS One. 2021;16(6):e0253499. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0253499.

- Mose A. Willingness to receive COVID-19 vaccine and its determinant factors among lactating mothers in Ethiopia: a cross-sectional study. Infect Drug Resist. 2021;14:4249. doi:10.2147/IDR.S336486.

- Shitu K, Wolde M, Handebo S, Kassie A. Acceptance and willingness to pay for COVID-19 vaccine among school teachers in Gondar City, Northwest Ethiopia. Trop Med Health. 2021;49(1):1–12. doi:10.1186/s41182-020-00291-y.

- Zewude B, Habtegiorgis T. Willingness to take COVID-19 vaccine among people most at risk of exposure in Southern Ethiopia. Pragmat Obs Res. 2021;12:37. doi:10.2147/POR.S313991.

- Taye BT, Amogne FK, Demisse TL, Zerihun MS, Kitaw TM, Tiguh AE, Mihret MS, Kebede AA. Coronavirus disease 2019 vaccine acceptance and perceived barriers among university students in northeast Ethiopia: a cross-sectional study. Clin Epidemiology Glob Health. 2021;12:100848. doi:10.1016/j.cegh.2021.100848.

- Alqudeimat Y, Alenezi D, AlHajri B, Alfouzan H, Almokhaizeem Z, Altamimi S, Almansouri W, Alzalzalah S, Ziyab AH. Acceptance of a COVID-19 vaccine and its related determinants among the general adult population in Kuwait. Med Princ Pract. 2021;30(3):262–271. doi:10.1159/000514636.

- Alghamdi AA, Aldosari MS, Alsaeed RA. Acceptance and barriers of COVID-19 vaccination among people with chronic diseases in Saudi Arabia. J Infect Dev Ctries. 2021;15(11):1646–1652. doi:10.3855/jidc.15063.

- Dimala CA, Kadia BM, Nguyen H, Donato A. Community and provider acceptability of the COVID-19 vaccine: a systematic review and meta-analysis systematic review and meta-analysis. Acmrhd. 2021;1(3) doi:10.53785/2769-2779.1076.

- Mahmud S, Mohsin M, Hossain S, Islam MM, Muyeed A The acceptance of COVID-19 vaccine: a global rapid systematic review and meta-analysis. Available at SSRN 3855987. 2021.

- Kaadan MI, Abdulkarim J, Chaar M, Zayegh O, Keblawi MA. Determinants of COVID-19 vaccine acceptance in the Arab world: a cross-sectional study. Glob Health Res Policy. 2021;6(1):1–7. doi:10.1186/s41256-021-00202-6.

- Malik A, Malik J, Ishaq U. Acceptance of COVID-19 vaccine in Pakistan among health care workers. medRxiv. 2021;16(9):e0257237 doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0257237 .

- Lau JFW, Woon YL, Leong CT, Teh HS. Factors influencing acceptance of the COVID-19 vaccine in Malaysia: a web-based survey. Osong Public Health Res Perspect. 2021;12(6):361–373. doi:10.24171/j.phrp.2021.0085.

- Wong LP, Alias H, Danaee M, Ahmed J, Lachyan A, Cai CZ, Lin Y, Hu Z, Tan SY, Lu Y, et al. COVID-19 vaccination intention and vaccine characteristics influencing vaccination acceptance: a global survey of 17 countries. Infect Dis Poverty. 2021;10(1):1–14. doi:10.1186/s40249-021-00900-w.

- Adane M, Ademas A, Kloos H. Knowledge, attitudes, and perceptions of COVID-19 vaccine and refusal to receive COVID-19 vaccine among healthcare workers in northeastern Ethiopia. BMC Public Health. 2022;22(1):1–14. doi:10.1186/s12889-021-12362-8.

- Tesfaw A, Arage G, Teshome F, Taklual W, Seid T, Belay E, Mehiret G. Community risk perception and barriers for the practice of COVID-19 prevention measures in Northwest Ethiopia: a qualitative study. PloS One. 2021;16(9):e0257897. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0257897.

- Khalis M, Boucham M, Luo A, Marfak A, Saad S, Mariama Aboubacar C, Ait El Haj S, Jallal M, Aazi F-Z, Charaka H, et al. COVID-19 vaccination acceptance among health science students in Morocco: a cross-sectional study. Vaccines. 2021;9(12):1451. doi:10.3390/vaccines9121451.

- Al-Qerem WA, Jarab AS. COVID-19 vaccination acceptance and its associated factors among a Middle Eastern population. Front Public Health. 2021;9:34. doi:10.3389/fpubh.2021.632914.

- Nindrea RD, Usman E, Katar Y, Sari NP. Acceptance of COVID-19 vaccination and correlated variables among global populations: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Epidemiology Glob Health. 2021;12:100899. doi:10.1016/j.cegh.2021.100899.

- Piltch-Loeb R, Savoia E, Goldberg B, Hughes B, Verhey T, Kayyem J, Miller-Idriss C, Testa M. Examining the effect of information channel on COVID-19 vaccine acceptance. PloS One. 2021;16(5):e0251095. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0251095.

- Hong J, Xu X-W, Yang J, Zheng J, Dai S-M, Zhou J, Zhang Q-M, Ruan Y, Ling C-Q. Knowledge about, attitude and acceptance towards, and predictors of intention to receive the COVID-19 vaccine among cancer patients in Eastern China: a cross-sectional survey. J Integr Med. 2022;20(1):34–44. doi:10.1016/j.joim.2021.10.004.

- Elharake JA, Galal B, Alqahtani SA, Kattan RF, Barry MA, Temsah M-H, Malik AA, McFadden SM, Yildirim I, Khoshnood K, et al. COVID-19 vaccine acceptance among health care workers in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Int J Infect Dis. 2021;109:286–293. doi:10.1016/j.ijid.2021.07.004.

- Mahmud S, Mohsin M, Khan IA, Mian AU, Zaman MA, Rajiah K. Knowledge, beliefs, attitudes and perceived risk about COVID-19 vaccine and determinants of COVID-19 vaccine acceptance in Bangladesh. PloS One. 2021;16(9):e0257096. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0257096.

- Mustapha M, Lawal BK, Sha’Aban A, Jatau AI, Wada AS, Bala AA, Mustapha S, Haruna A, Musa A, Ahmad MH, et al. Factors associated with acceptance of COVID-19 vaccine among university health sciences students in Northwest Nigeria. PloS One. 2021;16(11):e0260672. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0260672.

- Terefa DR, Shama AT, Feyisa BR, Desisa AE, Geta ET, Cheme MC, Tamiru Edosa A. COVID-19 vaccine uptake and associated factors among health professionals in Ethiopia. infect Drug Resist. 2021;14:5531–5541. doi:10.2147/IDR.S344647.

- Yanez ND, Weiss NS, Romand J-A, Treggiari MM. COVID-19 mortality risk for older men and women. BMC Public Health. 2020;20(1):1–7. doi:10.1186/s12889-020-09826-8.

- Hoffmann C, Wolf E. Older age groups and country-specific case fatality rates of COVID-19 in Europe, USA and Canada. Infection. 2021;49(1):111–116. doi:10.1007/s15010-020-01538-w.

- Kourlaba G, Kourkouni E, Maistreli S, Tsopela C-G, Molocha N-M, Triantafyllou C, Koniordou M, Kopsidas I, Chorianopoulou E, Maroudi-Manta S, et al. Willingness of Greek general population to get a COVID-19 vaccine. Glob Health Res Policy. 2021;6(1):1–10. doi:10.1186/s41256-021-00188-1.

- Reiter PL, Pennell ML, Katz ML. Acceptability of a COVID-19 vaccine among adults in the United States: how many people would get vaccinated? Vaccine. 2020;38(42):6500–6507. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2020.08.043.

- Yoda T, Katsuyama H. Willingness to receive COVID-19 vaccination in Japan. Vaccines. 2021;9(1):48. doi:10.3390/vaccines9010048.

- Bae S, Kim SR, Kim M-N, Shim WJ, Park S-M. Impact of cardiovascular disease and risk factors on fatal outcomes in patients with COVID-19 according to age: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Heart. 2021;107(5):373–380. doi:10.1136/heartjnl-2020-317901.

- Nishiga M, Wang DW, Han Y, Lewis DB, Wu JC. COVID-19 and cardiovascular disease: from basic mechanisms to clinical perspectives. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2020;17(9):543–558. doi:10.1038/s41569-020-0413-9.

- Flaherty GT, Hession P, Liew CH, Lim BCW, Leong TK, Lim V, Sulaiman LH. COVID-19 in adult patients with pre-existing chronic cardiac, respiratory and metabolic disease: a critical literature review with clinical recommendations. Trop Dis Travel Med Vaccines. 2020;6(1):1–13. doi:10.1186/s40794-020-00118-y.