ABSTRACT

This study aimed to evaluate the attitudes and practices of US healthcare professionals (HCPs) regarding the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) vaccination recommendations on HepA and HepB for adult patients at risk of contracting these infections or experiencing complications of hepatitis disease. This cross-sectional, web-based survey of 400 US HCPs, which included nurse practitioners and family medicine, internal medicine, infectious disease, emergency department, and gastroenterology physicians, assessed HCPs’ attitudes and practices regarding the ACIP recommendations for adult patients at risk for hepatitis disease. HCP participants were identified via a survey research panel. A recruitment quota of 400 HCPs was set, including 50 NPs, 100 FMs, 100 IMs, 50 GIs, 50 EDs, and 50 IDs. The most frequently reported reasons for not recommending either HepA or HepB vaccines were “I think the risk of HepA infection is low in this patient population” and “I am uncertain about what the guidelines say about vaccinating this population.” The most reported factors considered when determining eligibility for either vaccine were medical history and the patient’s willingness/motivation to be vaccinated. Most reported it was extremely or moderately important to prevent hepatitis disease by vaccinating adult patients at risk, and most also reported recommending a HepA vaccine or HepB vaccine to patients at risk. Although most HCPs reported recommending HepA and HepB vaccines to patients at risk, these findings contrast with the low reported vaccination rates among these populations, and improved awareness of the ACIP recommendations among HCPs is needed.

Plain Language Summary

Although hepatitis A and hepatitis B are vaccine-preventable diseases, not enough adults at risk are vaccinated in the United States (US). The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) makes recommendations on the use of vaccines in the US. The ACIP recommendations identify groups of people at risk of contracting hepatitis A infection or experiencing complications of hepatitis A disease (e.g., people with chronic liver disease) and hepatitis B infection or its related complications (e.g., people with diabetes).

To identify potential barriers to vaccination, we surveyed 400 US healthcare professionals to evaluate their views about the ACIP recommendations on hepatitis A and hepatitis B vaccination for patients at risk of infection or complications. Most reported it was extremely or moderately important to prevent hepatitis A or hepatitis B infection by vaccinating these adult patients. The most commonly reported reasons for not recommending either vaccine were “I am uncertain about what the guidelines say about vaccinating this population” and “I think the risk of hepatitis A or hepatitis B infection is low in this patient population”.

Our findings show that improved awareness of the guidelines among healthcare professionals is needed, particularly of the importance of hepatitis A vaccination, and hepatitis B vaccination in adults with diabetes. In addition to helping the ongoing multi-state hepatitis A outbreaks, this could aid in the successful implementation of the recent ACIP recommendation for hepatitis B vaccination in all adults that is expected to reduce barriers to vaccination.

Introduction

Hepatitis A (HepA) and Hepatitis B (HepB) are among the 14 vaccine-preventable adult diseases in the United States (US), as designated by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).Citation1 Since 2016, HepA outbreaks have emerged in 37 states, with 23 ongoing as of December 2021.Citation2 The CDC reported 18,846 acute HepA cases in 2019, but estimated the true number to be 37,000. These new cases contributed to a 1,325% increase in HepA incidence in the US from 2015 to 2019, attributable primarily to widespread outbreaks among individuals who reported illicit drug use or homelessness.Citation3–5 Reported HepB cases have been relatively stable over the past decade, with the CDC estimating approximately 20,000 annual acute infections from 2011 to 2019. However, HepB cases have been increasing in the 40–49 and 50–59 age groups.Citation6

Despite the widespread outbreaks and existence of vaccines with well-characterized safety profiles for both HepA and HepB, the most recent CDC estimates from 2018 showed that only 11.9% of US adults aged ≥19 y were vaccinated against HepA, and 30.0% were vaccinated against HepB.Citation7 The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) provides recommendations for vaccination of patient populations who are most at risk for HepA or HepB.

HepA and HepB vaccination coverage among adult patient populations at risk is suboptimal based on the most recent CDC estimates from 2018. For example, in patients with chronic liver disease HepA vaccination coverage was only 15.8%. In 2018, HepB vaccination coverage (≥3 doses) was 30.0% for US adults aged ≥19 y (the CDC Healthy People target set in 2010 was 90%).Citation7,Citation8 There was suboptimal HepB vaccination coverage for populations at risk, such as patients with diabetes (33.0% for those aged 19–49 y, 15.3% for those aged ≥60 y) and chronic liver disease (33.0% for those aged 19–49 y).Citation7 In 2020, the US Department of Health and Human Services called for increasing HepA and HepB vaccination in at-risk adults as recommended by the ACIP.Citation9

This study aimed to evaluate US healthcare providers’ (HCPs’) attitudes and practices regarding the ACIP vaccination recommendations on HepA and HepB vaccination for patients at risk of contracting these infections or experiencing complications of hepatitis disease. This study was conducted before the creation of the 2022 ACIP/CDC adult immunization schedule, which now includes a universal recommendation for HepB vaccination in adults aged 19–59 y.Citation10 Thus, patients at risk of HepB infection or experiencing complications were defined based on previous risk-based ACIP recommendations for adults.

Methods

Study design

This cross-sectional, web-based survey of 400 US HCPs included nurse practitioners (NPs) and family medicine (FMs), internal medicine (IMs), infectious disease (IDs), emergency department (EDs), and gastroenterology (GIs) physicians. The survey assessed HCPs’ attitudes and practices regarding the ACIP recommendations for adult patients at risk for HepA (patients with chronic liver disease [including persons with HepB], homeless individuals, injection/non-injection drug users, men who have sex with men (MSM), travelers visiting countries with endemic HepA infections) or HepB (patients with diabetes, patients with chronic liver disease [not including persons with HepB], injection/non-injection drug users, MSM, healthcare workers with percutaneous or mucosal risk for exposure to blood, and travelers visiting countries with endemic HepB infections).Citation11 Although not included in the ACIP recommendations as populations at risk for HepA, food handlers and healthcare workers at risk of exposure to blood were also included in this survey. One food handler infected with HepA can pass the virus to many downstream consumers, and although a CDC study estimated transmission in a restaurant setting to occur at less than 1%, the authors included food handlers in situations where secondary transmission risk is deemed high, and hence, should be prioritized for vaccination.Citation12 Furthermore, although healthcare workers are not considered to be at increased risk of infection for HepA due to occupation alone, those who work in certain healthcare settings (including HepA research laboratories, group homes, and healthcare settings targeting drug use) are considered to be at-risk by the CDC.Citation10 Data were collected from April 21 to 12 May 2020. This study was approved for exemption by an RTI institutional review board (Federal Wide Assurance #3331).

Participants

The methods describing survey development and eligibility criteria, and the survey questions, have been published previously.Citation13 Briefly, HCP participants were identified via a research panel owned by M3 Global Research.Citation14 A recruitment quota of 400 HCPs was set, including 50 NPs, 100 FMs, 100 IMs, 50 GIs, 50 EDs, and 50 IDs. Included HCPs who prescribed, recommended, or administered a HepA and HepB vaccine to an adult ≥18 y of age in the 3 months prior to the survey.

Primary outcomes

To assess HCPs’ attitudes relating to HepA and HepB vaccination in patients at risk, the proportion of HCPs who reported it was “extremely important” or “moderately important” to prevent HepA or HepB infection in patients at risk based on the ACIP recommendations was evaluated. The proportion of HCPs who reported “yes” to recommending a HepA or HepB vaccine to adult patients at risk was evaluated to assess HCPs’ practices relating to HepA and HepB vaccination in these populations.

Secondary outcomes

To further explore HCPs’ attitudes and practices, and to identify reasons why HCPs may not recommend HepA and HepB vaccines to all populations of interest, the following outcomes were evaluated: (1) the proportion of HCPs who were “very likely” to recommend a HepA or HepB vaccine to patients, calculated based on the total number of HCPs who had experience treating each patient group; (2) the proportion of HCPs who considered specific factors in determining a patient’s eligibility for a HepA or HepB vaccine, including medical history, vaccination history, willingness to be vaccinated, age, or reimbursement to the provider; and (3) reasons for not recommending vaccines to patient populations at risk.

Statistical analysis

Analyses were performed in SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute, Inc.; Cary, NC). Percentages of HCPs who provided responses to each question were calculated based on the total number of HCPs who had the opportunity to answer, excluding HCPs who were asked to skip the question due to a previous response. Binary primary and secondary outcomes were evaluated by constructing exact 95% confidence intervals (CIs) using the Clopper–Pearson method.

Results

HCP characteristics, practice setting, and experience with HepA and HepB vaccination

The characteristics of the surveyed HCPs have been previously published.Citation13 The sample was diverse regarding age, years practicing, and geography. Most HCPs reported working in a group private practice, and most practices were based in urban or suburban environments.

HCP attitudes and practices toward HepA and HepB vaccination in patients at risk

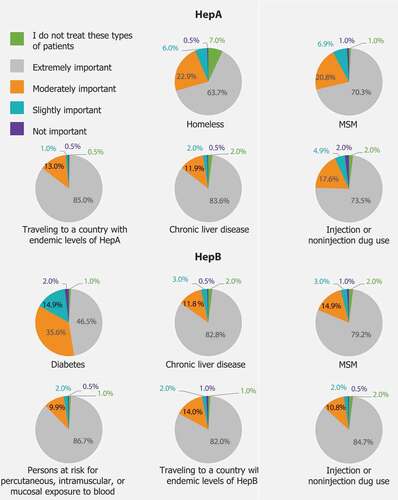

provides a summary of the study results and implications. HCPs were asked how important it was that individuals within the listed patient populations get vaccinated for HepA and HepB. For both HepA and HepB, “extremely important” was the most frequently reported response, followed by “moderately important” for each patient population listed ().

Figure 2. Importance of vaccinating for HepA or HepB based on the ACIP recommendations in the overall sample. ACIP: Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices; CDC: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; HepA: Hepatitis A; HepB: Hepatitis B. HCPs were asked how important it was to vaccinate the individuals within the listed patient populations for HepA based on the ACIP recommendations.

The proportions of HCPs who said it was moderately or extremely important to vaccinate patients at risk for HepA ranged from 87% [95% CI, 83–90%] for homeless patients to 99% [95% CI, 97–99%] for patients traveling to a country with endemic levels of HepA infection; for HepB, these proportions were between 83% [95% CI, 78–83%] for patients with diabetes and 97% for patients with current or recent injection drug use [95% CI, 94–98%], patients traveling to a country with endemic levels of HepB infection [95% CI, 94–98%], and healthcare workers at risk for exposure to blood [95% CI, 95–98%] (Table S1).

For each patient population at risk, the proportion of HCP participants who reported recommending a HepA or HepB vaccine were similar. When examining reported importance to vaccinate patients at risk by HCP specialty, EDs (60%) were the least likely to report that it was extremely important to vaccinate patients experiencing homelessness against HepA. EDs (30%) and IDs (36%) were considerably less likely to report it was extremely important to vaccinate patients with diabetes against HepB than IMs (55%) and NPs (60%; Table S2).

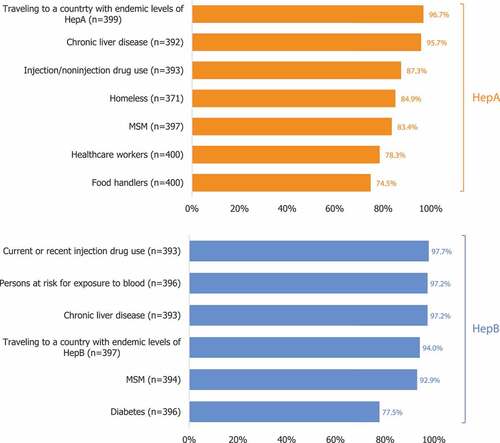

All HCPs were most likely to report recommending a HepA vaccine to patients traveling to countries with endemic HepA levels (97% [95% CI, 94–98%]) and least likely to report recommending the vaccine to food handlers (75% [95% CI, 70–79%]; food handlers are not included in the ACIP recommendations; ). Most HCPs reported recommending a HepB vaccine to each patient population, ranging from 78% for patients with diabetes to 98% for current or recent injection users. The proportion of HCPs who reported they recommend HepA or HepB vaccines was similar across specialties (Table S3).

Figure 3. Proportion of HCPs who report recommending a HepA or HepB vaccination to patients at risk (all HCPs, N = 400)*. HCP: healthcare provider; HepA: Hepatitis A; HepB: Hepatitis B; MSM: men who have sex with men. HCPs were asked if they recommended a HepB vaccine to specified patient populations (aged ≥ 19 years). *Percentages were calculated based on the total number of HCPs who reported having experience treating each patient population.

Most HCPs reported they were “very likely” to recommend a HepA vaccine or HepB vaccine to each population at risk (Figure S1). Out of all at risk patient groups, HCPs were least likely to respond they were “very likely” to recommend a HepB vaccine to patients with diabetes (64%).

Across all HCPs, the most commonly reported factors considered when determining eligibility for the HepA or HepB vaccine were medical history, including comorbidities (HepA: 94%, HepB: 96%), vaccination history (HepA: 93%, HepB: 95%), and willingness or motivation to be vaccinated (HepA: 92%, HepB: 93%; Figure S2).

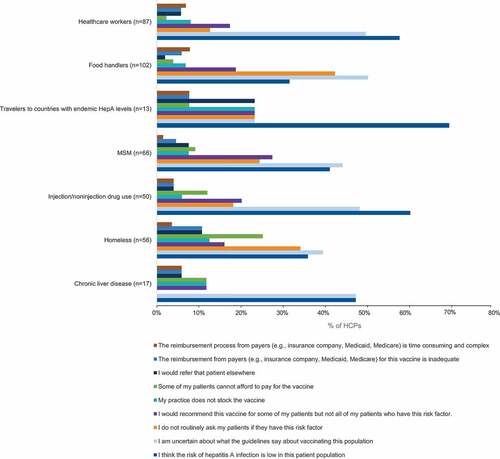

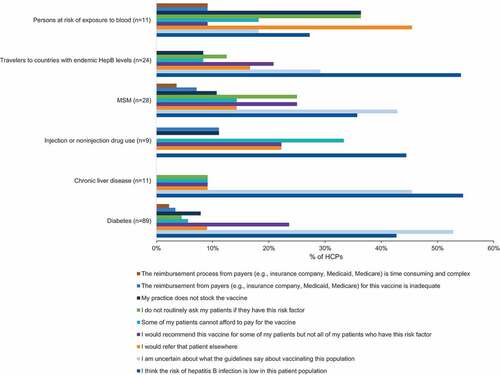

Reasons for not recommending HepA and HepB vaccines

Across all patient groups, the most commonly reported reasons for not recommending HepA vaccines were “I think the risk of HepA infection is low in this patient population” and “I am uncertain about what the guidelines say about vaccinating this population” (). Similarly, the most common reasons reported for not recommending HepB vaccines across all patient groups were “I am uncertain about what the guidelines say about vaccinating this population” and “I think the risk of HepB infection is low in this patient population” ().

Discussion

This study aimed to evaluate US HCPs’ attitudes and practices regarding the ACIP vaccination recommendations on HepA and HepB vaccination for patients at risk of contracting these infections or experiencing complications of hepatitis disease. Overall, most HCPs reported it was extremely or moderately important to vaccinate patients for HepA and HepB as per the recommendations. Most HCPs also reported they recommended vaccines to patients at risk. Previous analysis of these survey results showed approximately nine of ten HCPs reported following the recommendations most of the time or always.Citation13 However, this contrasts with the low vaccination rates among at-risk patient populations, suggesting the need for improved awareness of and education on the recommendations (including the recent HepB universal recommendation in adults 19–59 y of age).Citation7

The majority of HCPs reported it was moderately or extremely important to vaccinate patients at risk of HepA as per the ACIP recommendations. While roughly four in five HCPs reported recommending HepA vaccines to these patients at risk, the other one in five consider vaccinating homeless patients and drug users against HepA to be only moderately important. This finding is of particular interest because homeless patients and drug users comprise the majority of patients associated with the ongoing multi-state HepA outbreaks.Citation2

Only about six in ten EDs reported it was extremely important to vaccinate patients experiencing homelessness against HepA. Further, only 76% of EDs reported recommending a HepA vaccine to this patient population, representing the lowest proportion across all specialties. This is significant because emergency departments are often the primary point of care for the homeless,Citation15 and so ED adherence to the HepA vaccination recommendations is crucial to limit HepA outbreaks in this population.

Interestingly, about three-quarters of HCPs reported recommending HepA vaccines to food handlers and healthcare workers even when these populations are not recommended for HepA vaccination in the current ACIP recommendations. Vaccinating food handlers against HepA may protect both food handlers and consumers, and prevent the costly burden of an outbreak.Citation16

While more than nine in ten HCPs reported recommending the HepB vaccine to most patients at risk, only 78% reported recommending it to patients with diabetes. Similarly, HCPs were less likely to report that vaccinating patients with diabetes against HepB was extremely or moderately important, or that they were very likely to recommend the vaccine to patients with diabetes, compared with other patient populations. However, diabetes has been shown to be associated with an increased risk for acute HepB. Transmission can occur even in clinical settings such as assisted living arrangements through contaminated equipment such as shared glucose monitoring devices and insulin injection equipment.Citation17 It is important for HCPs to be aware of this high risk and recommend vaccines to patients with diabetes (under shared clinical decision-making for patients 60 y or older). HCP awareness of the recent universal recommendation for HepB vaccination in adults aged 19–59 y might simplify recommending HepB vaccines, and, hence, improve vaccination coverage in patients with diabetes, including those without medical records of diabetes.

Medical and vaccination history were considered by almost all HCPs before vaccination. Since HepA or HepB infection results in protective immunity, the ACIP does not recommend for patients with current or past HepA or HepB infections to receive the respective vaccines. While vaccinating these patients does not increase the risk for adverse events, pre-vaccination serologic testing in settings where the patient populations have a high risk of previous HepA or HepB infections can reduce costs by avoiding vaccination of patients with prior immunity. However, the ACIP notes that lack of access to pre-vaccination testing should not be a barrier to vaccination against HepA or HepB.Citation18,Citation19 Better record-keeping of adult immunizations across providers through, for example, immunization information systems, may facilitate the confirmation of patient vaccine history.Citation20 The rationale for the recent ACIP/CDC recommendation for all unvaccinated adults aged 19–59 y includes removing barriers such as limited time during routine patient encounters, provider and patients’ reluctance to discuss risk factors, and addressing health inequities.Citation21

Most HCPs also considered patients’ willingness/motivation to be vaccinated. The growth of vaccine hesitancy in the US over the last decade can be attributed to several factors, including false associations with the onset of medical conditions, being unfamiliar with the disease, and potential side effects.Citation22 Since the HepA and HepB vaccines have well-characterized safety profiles, this indicates there is a need for improved patient education regarding vaccines.

This study found the most frequently reported reasons for not recommending HepA or HepB vaccines for patients at risk were (1) the belief that the risk of infection is low in the patient population and (2) uncertainty about the ACIP recommendations for the population. These results echo the findings of a 2015 survey of primary care residents at academic institutions that investigated why HepB vaccination rates were suboptimal among patients with diabetes. The investigators surveyed the primary care medical residents about their knowledge of HepB and assigned them to an educational intervention or control group. The baseline knowledge survey scores reflected a lack of knowledge and risk-assessment skills regarding HepB in patients with diabetes. Comparison of the baseline knowledge scores with those immediately after the educational intervention and 6 months postintervention revealed the primary care residents consistently scored more than twice as high on the knowledge survey following the intervention.Citation23 This finding highlighted the need for improved awareness of and education regarding the vaccination recommendations among HCPs and proved the effectiveness of an educational intervention program. The universal recommendation for HepB vaccination in adults 19–59 years of age is a critical step to remove barriers inherent in risk-based recommendations. However, improved HCP awareness of and education regarding HepB vaccination in groups at risk will still be needed for patients 60 y or older.

The challenge of ensuring patients complete the designated number of doses in the series was considered a moderate barrier to vaccination by over 25% of respondents. This is notable because the CDC guidelines state that one dose of the HepA vaccine is considered sufficient for outbreak control.Citation24 This suggests that concerns about series completion should not deter HCPs from vaccinating at-risk patients, particularly during outbreaks.Citation25 The low percentages of HCPs that consider it moderately important to vaccinate these patient populations against HepA, even when a single dose is adequate, shows that HCP education on HepA vaccination practices is lacking.

Finally, about seven in ten HCPs in this study reported they consider reimbursement before vaccinating, highlighting the importance of provider reimbursement to ensure adequate vaccination coverage. Although Medicaid programs provide reimbursement for HepA, HepB, and HepA/HepB vaccines in 45, 50, and 48 states, respectively, reimbursement amounts vary by Medicaid program and provider. Even when Medicaid reimbursement is provided, it may not be sufficient to cover the cost of administering vaccinations. At least eight state programs do not provide separate reimbursement for vaccine administration, and no state provides separate reimbursement for vaccine counseling if a patient refuses vaccination.Citation26,Citation27 Moreover, Medicaid reimbursement payments for adult vaccine administration have been found to be substantially lower than payments from Medicare and private payers.Citation28 HCP concerns over reimbursement may therefore be a significant barrier to the vaccination of low-income individuals. Additionally, among private payers, one study has found that although reimbursement for vaccine administration is usually adequate for most private practices, there are large variations in insurance reimbursements between states. The same study also found that reimbursements were lower for nurse practitioners than for physicians.Citation29 Ensuring HCPs receive sufficient reimbursement for HepA, HepB, and other ACIP-recommended adult vaccination despite payer mix and provider type may lead to increased recommendation of these vaccines.

Limitations

Although the study population was diverse, included HCPs may not represent all US HCPs. Selection bias was another potential limitation of this study; members of the M3 panel may be systematically different from HCPs who are not in the panel. Finally, adherence to guidelines was self-reported and may not reflect actual vaccination practices, as HepA and HepB vaccination rates were not measured.

Conclusions

Most surveyed HCPs reported recommending HepA and HepB vaccines to patients at risk of infection or complications as recommended by the ACIP/CDC. However, improved awareness of the recommendations among HCPs is needed, particularly regarding the importance of HepA vaccination in light of the ongoing multi-state outbreaks among homeless persons and illegal drug users, as well as HepB vaccination in patients with diabetes.

Beginning with the 2022 adult immunization schedule, the ACIP/CDC now recommends HepB vaccination for all adults aged 19–59 y, and for those age 60 y and older if a known risk is present. Future studies could evaluate the impact of removing the risk-based recommendations for adults aged up to 59 y.

Prior presentation

The data presented in this manuscript on factors considered before administering Hepatitis A or Hepatitis B vaccines were presented at the American Association of Nurse Practitioners (AANP) 2021 National Conference and the European Public Health Conference (EPH) 2021.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (171.8 KB)Acknowledgments

The authors thank the healthcare providers who took part in this study. The authors also thank Costello Medical for editorial assistance and publication coordination, on behalf of GSK, and acknowledge Isabel Katz, Costello Medical, USA, for medical writing, and Jenna Hebert, PhD, Costello Medical, USA and Katie Hamilton, Costello Medical, UK, for publication coordination and editorial assistance based on authors’ input and direction. This study was funded by GlaxoSmithKline Biologicals SA.

Disclosure statement

OHR is an employee of and shareholder in the GSK group of companies; KD, CS, ED are employees of RTI Health Solutions; PG was an employee of and shareholder in the GSK group of companies at the time of the study and manuscript development, and is currently an employee of and shareholder in Moderna, Inc.; PB was shareholder in the GSK group of companies, was an employee of the GSK group of companies at the time of the study, and is currently an employee of and shareholder in Moderna, Inc.

Data availability statement

GSK makes available the anonymized individual participant data and associated documents from interventional clinical studies that evaluate medicines, upon approval of proposals submitted to www.clinicalstudydatarequest.com. To access data for other types of GSK sponsored research, for study documents without patient-level data and for clinical studies not listed, please submit an enquiry via the website.

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed on the publisher’s website at https://doi.org/10.1080/21645515.2022.2123180.

Additional information

Funding

References

- CDC. Vaccine-preventable adult diseases. [accessed 2021 Jul 30]. https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/adults/vpd.html.

- CDC. Widespread outbreaks of hepatitis A across the U.S. [accessed 2021 Jul 30]. https://www.cdc.gov/hepatitis/outbreaks/2017March-HepatitisA.htm.

- CDC. Hepatitis A surveillance in the United States for 2019. [accessed 2021 Jul 30]. https://www.cdc.gov/hepatitis/statistics/2019surveillance/HepA.htm.

- Foster MA, Hofmeister MG, Kupronis BA, Lin Y, Xia G-L, Yin S, Teshale E. Increase in hepatitis A virus infections — United States, 2013–2018. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019 May 10;68(18):1–9. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm6818a2.

- Peak CM, Stous SS, Healy JM, Hofmeister MG, Lin Y, Ramachandran S, Foster MA, Kao A, McDonald EC. Homelessness and Hepatitis A—San Diego County, 2016–2018. Clin Infect Dis. 2020 Jun 24;71(1):14–21. doi:10.1093/cid/ciz788.

- CDC. Hepatitis B surveillance in the United States for 2019. [accessed 2021 Jul 30]. https://www.cdc.gov/hepatitis/statistics/2019surveillance/HepB.htm.

- Lu PJ, Hung MC, Srivastav A, Grohskopf LA, Kobayashi M, Harris AM, Dooling KL, Markowitz LE, Rodriguez-Lainz A, Williams WW, et al. Surveillance of vaccination coverage among adult populations —United States, 2018. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2021;70(3):1–26. doi:10.15585/mmwr.ss7003a1.

- CDC. The healthy people 2010 database - October, 2011 edition. [accessed 2021 Aug 26]. https://wonder.cdc.gov/scripts/broker.exe?_SERVICE=default&_PROGRAM=HP2010.INC.SAS&_DEBUG=0&focus=&related=&sg=0&clfiles=BLY+BSL+Y98+Y99+Y00+Y01+Y02+Y03+Y04+Y05+Y06+Y07+Y08+Y09+Y10+TRG&srcenote=Y&footnote=Y&errsw=0&progname=OBJ&b=1&obj=14-28a&race=&source=&gender=&rm=&st=0&tr=&ato=0.

- HHS.Viral hepatitis national strategic plan: a roadmap to elimination for the United States (2021–2025). Washington, D.C; 2020.

- CDC. Recommended adult immunization schedule for ages 19 years or older. 2022 [accessed 2022 May 25]. https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/schedules/downloads/adult/adult-combined-schedule.pdf.

- Recommended Adult Immunization Schedule. 2021. https://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/102666.

- Hofmeister MG, Monique AF, Montgomery MP, Gupta N. Notes from the field: assessing the role of food handlers in hepatitis A virus transmission - Multiple States, 2016-2019. Mmwr. 2020;69(20):636–37. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm6920a4.

- Ghaswalla P, Davis K, Sweeney C, Davenport E, Trofa A, Herrera-Restrepo O, Buck PO, et al. Knowledge, practices and perceived barriers to hepatitis A and B vaccination guidelines: a survey of United States healthcare providers. J Nurse Pract. 2022;18(4).

- M3 Global Research. [accessed 2021 June]. https://www.m3globalresearch.com/.

- Kushel MB, Perry S, Bangsberg D, Clark R, Moss AR. Emergency department use among the homeless and marginally housed: results from a community-based study. Am J Public Health. 2002 May;92(5):778–84. doi:10.2105/ajph.92.5.778.

- Fleetwood J. Ethical considerations for mandating food worker vaccination during outbreaks: an analysis of hepatitis A vaccine. J Public Health Policy. 2021 Jun 29;42(3):465–76. doi:10.1057/s41271-021-00293-y.

- Reilly ML, Schillie SF, Smith E, Poissant T, Vonderwahl CW, Gerard K, Baumgartner J, Mercedes L, Sweet K, Muleta D, et al. Increased risk of acute hepatitis B among adults with diagnosed diabetes mellitus. J Diabetes Sci Technol. 2012 Jul 1;6(4):858–66. doi:10.1177/193229681200600417.

- Nelson NP, Weng MK, Hofmeister MG, Moore KL, Doshani M, Kamili S, Koneru A, Haber P, Hagan L, Romero JR, et al. Prevention of hepatitis A virus infection in the United States: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020 Jul 3;69(5):1–38. doi:10.15585/mmwr.rr6905a1.

- Schillie S, Vellozzi C, Reingold A, Harris A, Haber P, Ward JW, Nelson NP, et al. Prevention of hepatitis B virus infection in the United States: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018 Jan 12;67(No. RR–1):1–31. doi:10.15585/mmwr.rr6701a1.

- Vaccines National Strategic Plan for the United States (2021–2025)

- Weng MK, Doshani M, Khan MA, Frey S, Ault K, Moore KL, Hall EW, Morgan RL, Campos-Outcalt D, Wester C, et al. Universal hepatitis B vaccination in adults aged 19–59 years: updated recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices — United States, 2022. MMWR. 2022;71(13):477–83. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm7113a1.

- Salmon DA, Dudley MZ, Glanz JM, Omer SB. Vaccine hesitancy: causes, consequences, and a call to action. Vaccine. 2015 Nov 27;33(Suppl 4):D66–71. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.09.035.

- Ngamruengphong S, Horsley-Silva JL, Hines SL, Pungpapong S, Patel TC, Keaveny AP. Educational intervention in primary care residents’ knowledge and performance of Hepatitis B vaccination in patients with diabetes Mellitus. South Med J. 2015 Sep;108(9):510–15. doi:10.14423/SMJ.0000000000000334.

- CDC. Outbreak-Specific considerations for hepatitis a vaccine administration. Hepatitis A Outbreaks; 2020 [accessed 2022 May 25]. https://www.cdc.gov/hepatitis/outbreaks/InterimOutbreakGuidance-HAV-VaccineAdmin.htm.

- CDC. Prevention of hepatitis A virus infection in the United States: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices. 2020. [accessed 2021 Aug 20]. https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/69/rr/rr6905a1.htm.

- Granade CJ, McCord RF, Bhatti AA, Lindley MC. State policies on access to vaccination services for low-income adults. JAMA Network Open. 2020;3(4):e203316. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.3316.

- Granade CJ, McCord RF, Bhatti AA, Lindley MC. Availability of adult vaccination services by provider type and setting. Am J Prev Med. 2021. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2020.11.013.

- Yarnoff B, Khavjou O, King G, Bates L, Zhou F, Leidner AJ, Shen AK. Analysis of the profitability of adult vaccination in 13 private provider practices in the United States. Vaccine. 2019 Sep 30;37(42):6180–85. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2019.08.056.

- Tsai Y, Zhou F, Lindley MC. Insurance reimbursements for routinely recommended adult vaccines in the private sector. Am J Prev Med. 2019 Aug;57(2):180–90. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2019.03.011.