ABSTRACT

This study aimed to investigate multi-dimensional psychological and social factors that influence the willingness to receive a COVID-19 vaccine booster in China. A nationwide cross-sectional online survey was conducted between March and April 2022. A total of 6375 complete responses were received. The majority were of age 18 to 40 years old (80.0%) and college-educated (49.2%). In total, 79% responded extremely willing to receive a COVID-19 vaccine booster. By demographics, younger age, females, higher education, and participants with the lowest income reported higher willingness. Having a very good health status (odds ratio [OR] 3.56, 95% confidence interval [CI] 2.92–4.34) and a higher score of vaccine confidence (OR 3.50, 95% CI 2.98–4.11) were associated with an increased willingness to receive a booster shot. Experiencing no side effects with primary COVID-19 vaccination (OR 2.46, 95% CI 1.89–3.20) and higher perceived susceptibility of COVID-19 infection (OR 2.38, 95% CI 1.92–2.95) were also associated with an increased willingness to receive a booster shot. A variety of psychosocial factors, namely having no chronic diseases, lower perceived concern over the safety of a booster shot, higher perceived severity of COVID-19 infection, and a higher level of institutional trust, were also significantly associated with greater willingness to get a booster shot. In conclusion, the present study adds evidence to the significant role of psychosocial factors in predicting COVID-19 vaccine booster acceptance and provides insights to design interventions to increase booster uptake in certain targeted demographic groups.

Introduction

COVID-19 vaccinations greatly reduce the risk of SARS-CoV-2 infection and are essential to mitigate the COVID-19 pandemic. The vaccines to prevent COVID-19 have proven to be safe and effective.Citation1 To date, more than 5.16 billion people worldwide, or 67.4% of the global population, have received a dose of the COVID-19 vaccine.Citation2 In many countries, the coronavirus pandemic has ceased to be a worry, with declining daily cases and hospitalization rates. This would not have been made possible without the global rollout of the COVID-19 vaccines. However, the pandemic should not be assumed to be over. The serum antibody levels in vaccinated individuals gradually decline over time.Citation3 Furthermore, since its identification in late December 2019 in Wuhan, large-scale whole-genome sequencing of the SARS-CoV-2 genome has identified many sequence changes, and SARS-CoV-2 variants of concern have been reported to have potential immune escape, and they exhibit worrisome epidemiologic, immunologic, or pathogenic characteristics.Citation4 A COVID-19 vaccine booster may increase SARS-CoV-2-specific neutralizing antibody levels and result in even stronger and longer-lasting protection from the primary doses.Citation5 Consequently, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) announced booster shot recommendations for individuals above the age of 12 years who had completed their primary vaccination series.Citation6

As of 28 April 2022, approximately 86.5% of people in China had been fully vaccinated against SARS-CoV-2.Citation7 There are five vaccines included in the public vaccination programme: CanSino, Sinopharm (Beijing), Sinopharm (Wuhan), Sinovac, and ZF2001 developed by Anhui Zhifei Longcom.Citation7 The National Health Commission’s Bureau of Disease Control and Prevention of the People’s Republic of China reported that China had administered a total of 3. 340,711 billion doses of the COVID-19 vaccines. A total of 1249.688 million people in China had fully administered the COVID-19 vaccine, among which 750.189 million have received the booster dose.Citation8

Since the COVID-19 vaccines received approval for use, many studies assessing the acceptance of primary COVID-19 vaccines have been conducted in ChinaCitation9–11 and many other countries around the world.Citation12–15 There have also been some recently published studies about the acceptance of a COVID-19 vaccine booster in China,Citation12–16–Citation20 with an acceptance rate ranging from 75% to 94%.Citation16–20 However, factors that influence COVID-19 booster vaccine acceptance have not been researched extensively and warrant further investigation. Despite the COVID-19 vaccination has substantially altered the course of the pandemic and prevented an estimated 14.4 million death from COVID-19 globally,Citation21 considerable vaccine hesitancy persists and remains complex. Global studies have revealed that the acceptance of primary COVID-19 vaccinations is influenced by a variety of factors related to psychological and societal aspects, and the vaccine itself.Citation12,Citation22 Similarly, recent studies on willingness to receive a COVID-19 vaccine booster in China found that, among other factors, there are specific psychosocial and societal factors; specifically, individual motivation toward self-protective measures and vaccine confidence greatly influence vaccination intention.Citation16,Citation17 Investigating other psychosocial factors – for example, public trust in government institutions and perception of the threat of COVID-19 infection – might further enhance understanding of why some people are skeptical or hesitant about receiving a COVID-19 vaccine booster. Perceived susceptibility and perceived severity are two dimensions of ‘threat’ in the Health Belief Model (HBM).Citation23 Perceived susceptibility refers to beliefs regarding vulnerability to infection, while perceived severity refers to beliefs regarding the negative effects of contracting the infection. Perception of the virus threat emerged as the most widely construct in the HBM model in vaccination behaviors and has been recognized as an important predictor of primary COVID-19 vaccination uptake in previous studies around the world as well as in China.Citation9 Individuals who perceived the virus as a serious threat tended to comply with recommended primary and booster vaccinations, whereas those who considered that the pandemic has subsided or is no longer dangerous tended to refuse booster vaccination. Similarly, the population’s trust in government authorities and the public health system is a critical aspect that affects adherence to recommended primary COVID-19 vaccination, a finding that has been supported by local and international studies.Citation24,Citation25 Less is known, however, regarding whether COVID-19 booster vaccine acceptance is influenced by these psychosocial factors.

To fully comprehend the public responses to the current recommendation for COVID-19 vaccine booster in China, it is necessary to investigate multifaceted psychological and social indicators influencing willingness to receive a COVID-19 vaccine booster dose. This endeavor will allow proposing strategies to enhance COVID-19 vaccine booster acceptance.

Methodology

Study participants and survey design

A nationwide cross-sectional study was conducted from 15 March to 23 April 2022, through the dissemination of an online survey in all regions of mainland China. The inclusion criteria were that the respondents were Chinese citizens aged ≥18 years, who had received a completed recommended dose of the primary COVID-19 vaccination series, and who had not received a COVID-19 vaccine booster. The researchers used the social network platform WeChat to advertise and disseminate the survey link. Both professional and personal networks of the researchers, faculty members, students, and alumni were used to reach out to the general public. Respondents who completed the survey received a note encouraging them to disseminate the survey link to all their friends and family members.

The sample size was calculated for each region using the formula: n = Z2 P(1–P)/d2 where Z = 1.96 for a confidence level of (α) of 95%, P = % of population probability, assumed to be 50%, d = margin of error of 0.05. Using a margin of error of 0.05 (5%), with a 95% CI and 50% response distribution, the calculated sample size was 384.

Measures

The survey consisted of questions (Appendix 1) that assessed (1) demographic characteristics and general health status; (2) experience of side effects with primary COVID-19 vaccination; (3) perceived safety concerns of a COVID-19 vaccine booster; (4) perceived threat of COVID-19 infection; (5) vaccine confidence; (6) institutional trust; and (7) intention to receive a COVID-19 vaccine booster.

The demographic questions were age, gender, birth location, current residence, regional location, average monthly household income, and highest educational attainment. Participants were asked if they had ever been diagnosed with chronic diseases. They were asked to rate their health on a continuum from very poor to very good. In the second section of the questionnaire, study participants were asked to rate the severity of the side effects they experienced in their past primary COVID-19 vaccination series on a scale from 0 (no side effects at all) to 10 (very severe side effects). The scale was classified as 0 (no side effects at all), 1–5 (mild to moderate), or 6–10 (moderate to severe). The third section assessed participants’ perceptions of worries about serious adverse side effects of a COVID-19 booster dose and unknown long-term side effects of receiving multiple doses of a COVID-19 vaccine. The questions in this section were self-developed. The response options were strongly agree, agree, disagree, or strongly disagree. The section on the perceived threat of COVID-19 infection asked participants’ perceptions of susceptibility and severity of COVID-19 infection influencing perceived needs for COVID-19 booster were assessed in single-item question. The perceived threat construct was adopted from the Health Belief Model.Citation26 The response options were strongly agree, agree, disagree, or strongly disagree. Vaccine confidence was measured using three survey statements related to individual perceptions of the importance, safety, and effectiveness of vaccines, adapted from a previous study.Citation27 The response options were rated using a 5-point Likert-type scale (1 = strongly disagree, 2 = disagree, 3 = neither agree nor disagree, 4 = agree and 5 = strongly agree). The total score ranges from 3 to 15, with higher scores indicating a higher level of vaccine confidence. Institutional trust assessed how participants attribute trust to public authorities regarding the management of the COVID-19 emergency in China and implementation of the COVID-19 vaccination programmes in China on a scale from 0 (completely no trust) to 10 (extremely trust). The last question queried participants on their willingness to receive a COVID-19 vaccine booster was measured using a one-item question on a five-point scale (extremely willing to extremely unwilling).

The questionnaire was content validated. Content validation involved consulting with experts and academics to evaluate whether the items in the questionnaire were clear and represented the intended construct. A forced answering option was implemented where all questions had to be answered before the participant could move on to the next page to avoid incomplete responses. Data checking and cleaning were carried out before analyses to ensure valid and reliable responses. Straightlining and duplicate responses were checked and removed.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive analyses were performed to examine the distribution of all variables of interest, including normality, means, and frequencies. Vaccine confidence item scores were totaled. The score for vaccine confidence was not normally distributed, so the median and interquartile range (IQR) are used to describe these scores. Cronbach’s alpha was calculated for the vaccine confidence scale to assess reliability in terms of internal consistency. The vaccine confidence scale had good internal consistency, with Cronbach’s alpha of 0.893. Binary logistic regression and multivariate logistic regression were used to explore the factors affecting the intention to receive COVID-19 vaccine booster (1 = definitely willing; 0 = somewhat willing/undecided/somewhat unwilling/definitely unwilling). The variables with p < .05 in the binary logistic regression analyses were entered into the multivariate logistic regression model. The odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were computed for each independent variable. The model fit was assessed using the Hosmer – Lemeshow goodness-of-fit test. The Hosmer – Lemeshow statistic indicated a poor fit if the significance value is <0.05.Citation28 All analyses were also conducted using SPSS version 22.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Statistical significance was established at a p-value <.05.

Ethical considerations

This study was implemented according to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and granted ethical approval by the Fujian Medical University Research Ethics Committee, China (FJMU 2021 NO.63). Identifying information was not collected from the participants when they completed the survey. Participants were also informed that their participation was voluntary. To consent to participate, participants were required to click “Yes, I consented to participate in this study.” Participants were compensated with 1–3 CNY upon completion of the survey.

Results

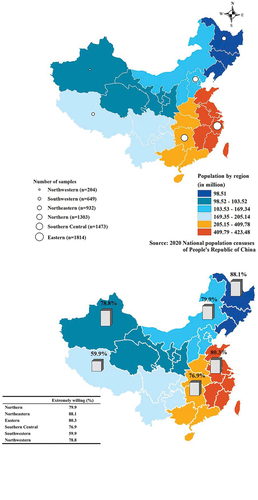

A total of 6375 complete responses were received in the survey. shows the distribution of responses by region. The majority of the respondents were from the Southern Central and Eastern regions. shows the demographics of the study participants. The age of the participants ranged from 18 to 80 years (mean = 33.3, standard deviation [SD] ± 10.4). The majority were between 18 and 30 (45.0%) and 31 and 40 (35.0%) years old. There were almost equal proportions of male (51.7%) and female (49.3%) respondents. By education level, 31.8% had high school as the highest education level, while university graduates comprised 49.2%. Based on the income categories, a slightly lower proportion had an average monthly income of ≥15,000 CNY (15.6%). Most participants (86.5%) did not have any chronic diseases. Most participants were from urban areas (71.0%), and a majority of the participants were from the Eastern (28.5%) Southern Central (23.1%), and Northern China (20.5%) regions ().

Figure 1. Distribution of responses and proportion reported extreme willingness to receive a COVID-19 vaccine booster by regions.

Table 1. Demographic characteristics of study participants and univariate analyses of factors associated with willingness to receive COVID-19 vaccine booster.

In total, 21.6% (n = 1375) of the participants had not experienced side effects in their past primary COVID-19 vaccination, while over half (59.8%) rated their side effects as mild to moderate (1–5) and 25.5% rated them as moderate to severe (6–10). A total of 40.2% of the participants reported strongly agree/agree about being worried about the serious side effects of a COVID-19 vaccine booster. Similarly, 40.6% expressed they strongly agree/agree about being worried over unknown long-term side effects of multiple doses of COVID-19 vaccines. A smaller proportion (24.5%) perceived low susceptibility to COVID-19 infection. Meanwhile, a relatively lower proportion (20.5%) perceived low severity of COVID-19 infection

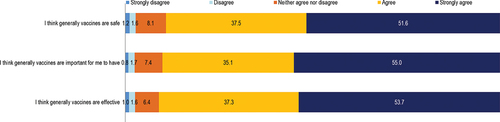

The responses to vaccine confidence items are shown in Appendix 2. The total vaccine confidence score range was 3 to 15, and the median was 14.0 (IQR 12.0–15.0). The vaccine confidence score was categorized as 3–13 or 14–15, based on the median split; as such, a total of 3012 (47.2%, 95% CI 46.0%–48.5%) were categorized as having a score of 3–13 and 3363 (52.8%, 95% CI 51.5%–54.0%) were categorized as having a score of 14–15.

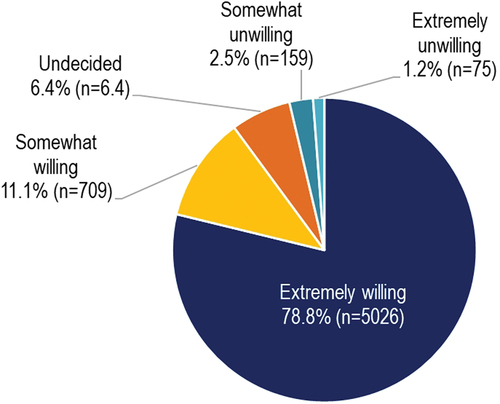

shows the proportion of responses for intention to receive a COVID-19 vaccine booster. Overall, 5026 (78.8%) participants responded that they would be extremely willing to receive a COVID-19 vaccine booster, while 709 (11.1%) responded they would be somewhat willing. Only 75 participants (1.2%) responded they would be extremely unwilling. Participants from the Southwestern region (59.9%) reported the lowest proportion of being extremely willing to receive a COVID-19 vaccine booster ().

shows the univariable analyses of factors influencing willingness to receive a COVID-19 booster. Significant factors in the univariate analyses were included in the multivariable analysis. The finding of multivariate regression analysis of factors influencing willingness to receive a COVID-19 booster is shown in . By demographics, participants aged 41–50 years had the highest significant odds of extreme willingness to receive a COVID-19 vaccine booster (OR 1.49, 95% CI 1.10–2.03). Female participants expressed higher odds of extreme willingness to receive a COVID-19 vaccine booster than males (OR 1.21, 95% CI 1.05–1.40). College-educated participants reported the highest significant odds of extreme willingness to receive a COVID-19 vaccine booster compared with participants with secondary and lower education (OR 1.25, 95% CI 1.02–1.53). Participants in the lowest income group reported the highest significant odds of extreme willingness to receive a COVID-19 vaccine booster (OR 2.01, 95% CI 1.57–2.57). Participants without chronic diseases reported significantly higher odds of extreme willingness to receive a COVID-19 vaccine booster compared with those with chronic diseases (OR 1.28, 95% CI 1.06–1.55). Having very good (OR 3.56, 95% CI 2.92–4.34) and good health status (OR 1.76, 95% CI 1.49–2.08) were significantly associated with higher odds of extreme willingness to receive a COVID-19 vaccine booster. Appendix 3 showed the results of the multivariate regression analysis of only the demographic characteristics influencing willingness to receive a COVID-19 booster. Similar to those reported in , most of the demographic characteristics significantly associated with the willingness to receive a COVID-19 vaccine booster.

Table 2. Multivariable analysis of factors associated with willingness to receive COVID-19 vaccine booster.

Participants who had experienced no side effects with primary COVID-19 vaccination reported significantly higher odds of extreme willingness to receive a COVID-19 vaccine booster (OR 2.46, 95% CI 1.89–3.20) compared with those who reported mild to moderate or moderate to severe side effects. Higher perceived worry of adverse side effects after a booster dose (OR 1.28, 95% CI 1.01–1.62) and worry of unknown long-term side effects after receiving multiple doses of a COVID-19 vaccine (OR 1.55, 95% CI 1.22–1.96) also were associated with significantly higher odds of extreme willingness to receive a COVID-19 vaccine booster. Similarly, participants having higher perceived susceptibility (OR 2.38, 95% CI 1.92–2.95) and severity (OR 1.24, 95% CI 0.99–1.56) of COVID-19 infection were also associated with significantly higher odds of extreme willingness to receive a COVID-19 vaccine booster. Participants having a vaccine confidence score of 14–15 had significantly higher odds of extreme willingness to receive a COVID-19 vaccine booster than those who scored 3–13 (OR 3.50, 95% CI 2.98–4.11).

Participants who had a score of 6–10 in the level of trust in public authorities for the management of the COVID-19 emergency (OR 1.69, 95% CI 1.35–2.11) and trust in public authorities for the implementation of a COVID-19 vaccination programme (OR 1.67, 95% CI 1.33–2.10) were also significantly associated with higher odds of extreme willingness to receive a COVID-19 vaccine booster compared with those who had a score of 0–5. The Hosmer – Lemeshow test was not significant (p = .048), indicating a model with a good fit. The model accounted for 36.5% of the variation (Nagelkerke’s R2 = 0.365).

Discussion

In the present study, we found that nearly 80% of the participants expressed an extreme willingness to receive a COVID-19 vaccine booster dose, which is nearly similar to the recently published studies conducted in China.Citation16–18 It is important to note that the current study sample comprises mostly young and middle age people and college-educated. A large sample national study in China reported that COVID-19 vaccination acceptance was found to be associated with younger age.Citation10 This perhaps explains the overall high vaccination acceptance in this study. Nonetheless, our study adds to the body of evidence of the high COVID-19 vaccine booster acceptance among the Chinese public. Of note, other population surveys around the world have found varying rates of willingness to receive a COVID booster dose, ranging from only 45% among the public in Jordan,Citation29 62% in adult Americans,Citation30 and up to 90% among adults in Denmark.Citation31 High vaccination coverage for primary vaccination and booster doses represents the most important public health strategy to control the pandemic. Hence, pursuing booster vaccination against COVID-19 brings hope to limit the spread of SARS-CoV-2 and remains the most rational decision and important public health strategy to control the pandemic.

Despite overall high COVID-19 vaccine booster acceptance in this study, there is a regional disparity in booster acceptance. Acceptance is poorer in less economically developed regions. An international survey of COVID-19 vaccine acceptance in low-and middle-income countries likewise reported that poorer and less-educated individuals reported lower acceptance.Citation32 Therefore, government authorities should engage and take action in promoting booster uptake in these regions. Further, although people who refuse boosters account for a small proportion of the population, they require attention. The multivariable regression analyses showed that demographics play an important role in COVID-19 booster vaccine acceptance. Importantly, the present study shows that older age, males, and participants with lower educational achievement reported lower willingness to receive a COVID-19 vaccine booster, which provides insights into specific determinants of the target group for intervention to reduce disparities. Some similarities in demographics of people who are willing to receive booster dose have also been reported in other studies from ChinaCitation19 and other countries.Citation29–31

In this study, participants with preexisting health conditions were also more likely to be unwilling to receive a booster vaccine; this finding contradicts a previous study.Citation29 The CDC has approved the COVID-19 booster for people aged ≥50 years, and includes people with underlying medical conditions as the vaccine helps to prevent severe illness or death from SARS-CoV-2.Citation6 Healthcare providers should assist in evaluating the appropriateness of people with poor health or underlying medical condition to receive a booster shot, to clarify their misconceptions and to provide recommendations. Additionally, efforts should be made to promote the benefits and safety of a COVID-19 vaccine booster in older adults, particularly those with multiple comorbidities and frailty.

Although the majority of the study participants had a high level of vaccine confidence, we still found that this measure is an important predictor of COVID-19 vaccine booster acceptance. A significant association between vaccine confidence and COVID-19 vaccine booster dose acceptance has also been reported in another study.Citation29 Public confidence in vaccination is vital to the success of immunization programmes worldwide.Citation28 Hence, to promote COVID-19 vaccine booster acceptance, there should be an emphasis on improving communication to build and maintain trust to strengthen vaccine confidence. It is also important to note that experiencing side effects after primary COVID-19 vaccination impacts the vaccine booster dose decision, as evidenced by the over twofold higher odds of willingness to receive a COVID-19 booster among those who experienced no side effects after primary COVID-19 vaccination. The results from this study and previous studies in China imply that worry about side effects and vaccine safety are consistent, predominant concerns for the acceptance of COVID-19 primary and booster vaccination.Citation9,Citation33,Citation34 Likewise, adverse side effects and vaccine safety were among the prime concerns reported in other studies worldwide.Citation15,Citation32 Individuals who are concerned about the risks of emergent adverse events following immunization (AEFI) need to be provided with some reassurance that the common side effects reported after getting a booster shot are similar to those after the two-dose or single-dose primary shots. Specifically, fever, headache, fatigue, and pain at the injection site have been the most commonly reported side effects and, overall, most side effects are mild to moderate.Citation35 Messages should also highlight that the benefits of booster vaccination outweigh the potential risks of AEFI and the consequences of contracting COVID-19 infection.

We have found that perceived susceptibility to COVID-19 infection had over twofold higher odds of willingness to receive a booster shot, in agreement with another study in China.Citation19 We also identified an association between perception of severity of COVID-19 infection and booster shot uptake intent, which implies the importance of introducing risk communication with the public. This finding suggests that the perceived threat construct in the HBM may provide insights into a promising intervention to promote COVID-19 booster uptake. Similarly, the population’s trust in government authorities and the public health system is a critical aspect that affects adherence to the recommendation of primary COVID-19 vaccination, both of which have been supported by previous localCitation24 and internationalCitation22 studies. We have shown that people who are more trusting in government authorities and the public health system are in favor of getting the booster vaccination. The results of this study further confirm the importance of institutional trust in the context of acceptance of recommended vaccinations. Hence, reviving trust in national health authorities is imperative.

Limitations

There are some limitations of the current study that need to be considered when interpreting the results. Firstly, the cross-sectional design used could not infer a causal relationship. Secondly, the survey link was disseminated through WeChat, therefore, we are unable to obtain the denominator for a calculation of response rates. Thirdly, internet surveys represent convenience samples that may have limited generalizability to the general population due to selection bias. To enhance generalizability we have recruited a relatively large sample size and the demographics of the study participants closely represent the general public in mainland China, however, there is a lack of representation from the Northwest region. Future research should include a more representative sample that encompasses the diverse demographics of the general public in China.

Conclusion

Our findings have revealed a considerably high acceptance rate of COVID-19 booster vaccination in a sample of the general public in mainland China, most were young and middle age adults and college-educated. Despite the high acceptance rate, it remains important to address vaccination attitudes among people hesitant about the vaccine. The present study adds evidence to the significant role of psychosocial factors in predicting COVID-19 vaccine booster acceptance and provides insights to design interventions to increase booster uptake in certain targeted demographic groups. Our findings outline several implications for both health care providers and policymakers. First, the results of vaccination attitudes among individual with poor health, frail patients, and those who experienced severe side effects in primary COVID-19 vaccinations suggests that people are particularly concerned with the safety of the booster dose. Thus, efforts to improve coverage of booster dose vaccination should focus on the identified vaccine-hesitant groups and provide targeted intervention to help them eliminate their irrational safety concerns, increase vaccine confidence, and enlighten them about the potential benefit of booster vaccination on the greater, more durable protection against severe outcomes. Second, COVID-19 threat perception can be applied to understanding COVID-19 booster vaccination intent. Hence, understanding people’s perceived health threat of COVID-19 infection is a critical step toward creating risk communication campaigns. Third, a positive association between institutional trust with COVID-19 vaccine booster vaccination intention is evident. Therefore, ongoing communications need to focus on strengthening trust in government institutions, systems, and processes.

Authors’ contribution

Yulan Lin, Zhijian Hu and Li Ping Wong contributed to the study conception and design. Data collection was performed by Yulan Lin, Zhiwen Huang, Xiaonan Xu, Wei Du and Zhijian Hu. Data analysis was performed by Li Ping Wong and Haridah Alias. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Li Ping Wong and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- CDC. Safety of the COVID-19 vaccines. 2022 May 16. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/vaccines/safety/safety-of-vaccines.html.

- Holder J. Tracking Coronavirus vaccinations around the World. The New York Times; 2022 May 18. https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2021/world/covid-vaccinations-tracker.html.

- Marcotte H, Piralla A, Zuo F, Du L, Cassaniti I, Wan H, Kumagai-Braesh M, Andréll J, Percivalle E, Sammartino JC. Immunity to SARS-CoV-2 up to 15 months after infection. ISci. 2022 Jan;7(2):1.

- Lou F, Li M, Pang Z, Jiang L, Guan L, Tian L, Hu J, Fan J, Fan H. Understanding the secret of SARS-CoV-2 variants of concern/interest and immune escape. Front Immunol. 2021;12:4326.

- Burckhardt RM, Dennehy JJ, Poon LL, Saif LJ, Enquist LW. Are COVID-19 vaccine boosters needed? the science behind boosters. J Virol. 2021 Nov 24;96(3): e01973-21.

- CDC. COVID-19 vaccine booster shots. 2022 May 13. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/vaccines/booster-shot.html.

- Zhang W. COVID-19 vaccination rate in China 2021-2022, by status. Statista; 2022 May 9. https://www.statista.com/statistics/1279024/china-coronavirus-covid-19-vaccination-rate/.

- CCTV. National health commission: over 700 million people complete booster immunization. 2022 Apr 29. http://news.cctv.com/2022/04/29/ARTIhw56yOrYtSUyG93mjXsX220429.shtml.

- Lin Y, Hu Z, Zhao Q, Alias H, Danaee M, Wong LP, Marques ETA. Understanding COVID-19 vaccine demand and hesitancy: a nationwide online survey in China. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2020 Dec 17;14(12):e0008961.

- Wu J, Ma M, Miao Y, Ye B, Li Q, Tarimo CS, Wang M, Gu J, Wei W, Zhao L. COVID-19 vaccination acceptance among Chinese population and its implications for the pandemic: a national cross-sectional study. Front Pub Health. 2022;10:796467. doi:10.3389/fpubh.2022.796467

- Huang Y, Su X, Xiao W, Wang H, Si M, Wang W, Gu X, Ma L, Li L, Zhang S. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy among different population groups in China: a national multicenter online survey. BMC Infect Dis. 2022 Dec;22(1):1–11. doi:10.1186/s12879-022-07111-0.

- Shakeel CS, Mujeeb AA, Mirza MS, Chaudhry B, Khan SJ. Global COVID-19 vaccine acceptance: a systematic review of associated social and behavioral factors. Vaccines. 2022 Jan;10(1):110. doi:10.3390/vaccines10010110.

- Snehota M, Vlckova J, Cizkova K, Vachutka J, Kolarova H, Klaskova E, Kollarova H. Acceptance of a vaccine against COVID-19-a systematic review of surveys conducted worldwide. Bratisl Lek Listy. 2021 Jan 1;122(8):538–47.

- Sallam M. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy worldwide: a concise systematic review of vaccine acceptance rates. Vaccines. 2021 Feb 16;9(2):160. doi:10.3390/vaccines9020160.

- Wong LP, Alias H, Danaee M, Ahmed J, Lachyan A, Cai CZ, Lin Y, Hu Z, Tan SY, Lu Y. COVID-19 vaccination intention and vaccine characteristics influencing vaccination acceptance: a global survey of 17 countries. Infect Dis Poverty. 2021 Dec;10(1):1–4. doi:10.1186/s40249-021-00900-w.

- Wu F, Yuan Y, Deng Z, Yin D, Shen Q, Zeng J, Xie Y, Xu M, Yang M, Jiang S. Acceptance of COVID‐19 booster vaccination based on the Protection Motivation Theory (PMT): a cross‐sectional study in China. J Med Virol. 2022 May 4;94(9):4115–214. doi:10.1002/jmv.27825.

- Wang X, Liu L, Pei M, Li X, Li N. Willingness of the general public to receive a COVID-19 vaccine booster—china, April–May 2021. China CDC Weekly. 2022 Jan 28;4(4):66–70.

- Tung TH, Lin XQ, Chen Y, Zhang MX, Zhu JS. Willingness to receive a booster dose of inactivated coronavirus disease 2019 vaccine in Taizhou, China. Expert Rev Vaccines. 2022 Feb 1;21(2):261–67.

- Qin C, Wang R, Tao L, Liu M, Liu J. Acceptance of a third dose of COVID-19 vaccine and associated factors in China based on health belief model: a national cross-sectional study. Vaccines. 2022 Jan;10(1):89. doi:10.3390/vaccines10010089.

- Lai X, Zhu H, Wang J, Huang Y, Jing R, Lyu Y, Zhang H, Feng H, Guo J, Fang H. Public perceptions and acceptance of COVID-19 booster vaccination in China: a cross-sectional study. Vaccines. 2021 Dec;9(12):1461. doi:10.3390/vaccines9121461.

- Watson OJ, Barnsley G, Toor J, Hogan AB, Winskill P, Ghani AC. Global impact of the first year of COVID-19 vaccination: a mathematical modelling study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2022 Jun 23;22(9):1293–302.

- Roy DN, Biswas M, Islam E, Azam MS, Delcea C. Potential factors influencing COVID-19 vaccine acceptance and hesitancy: a systematic review. PloS One. 2022 Mar 23;17(3):e0265496.

- Glanz K, Rimer BK, Viswanath K. Health behavior and health education: theory, research, and practice. 4th ed. San Fracisco: John Wiley & Sons; 2008.

- Wong LP, Wu Q, Hao Y, Chen X, Chen Z, Alias H, Shen M, Hu J, Duan S, Zhang J. The role of institutional trust in preventive practices and treatment-seeking intention during the coronavirus disease 2019 outbreak among residents in Hubei, China. Int Health. 2022 Mar;14(2):161–69. doi:10.1093/inthealth/ihab023.

- De Figueiredo A, Simas C, Karafillakis E, Paterson P, Larson HJ. Mapping global trends in vaccine confidence and investigating barriers to vaccine uptake: a large-scale retrospective temporal modelling study. Lancet. 2020 Sep 26;396(10255):898–908. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31558-0.

- Champion V, Skinner CS. The health belief model. In: Glanz K, Rimer B, Viswanath K, editors. Health behavior and health education. Vol. 4. San Francisco (CA): Jossey-Bass; 2008. p. 45–65.

- Larson HJ, Schulz WS, Tucker JD, Smith DM. Measuring vaccine confidence: introducing a global vaccine confidence index. PLoS Curr. 2015 Feb 25;7. doi:10.1371/currents.outbreaks.ce0f6177bc97332602a8e3fe7d7f7cc4

- Hosmer DW Jr, Lemeshow S, Sturdivant RX. Applied logistic regression. Hoboken (NJ): John Wiley; 2013.

- Al-Qerem W, Al Bawab AQ, Hammad A, Ling J, Alasmari F. Willingness of the Jordanian population to receive a COVID-19 booster dose: a cross-sectional study. Vaccines. 2022 Mar 9;10(3):410. doi:10.3390/vaccines10030410.

- Yadete T, Batra K, Netski DM, Antonio S, Patros MJ, Bester JC. Assessing acceptability of COVID-19 vaccine booster dose among adult Americans: a cross-sectional study. Vaccines. 2021 Dec;9(12):1424. doi:10.3390/vaccines9121424.

- Sønderskov KM, Vistisen HT, Dinesen PT, Østergaard SD. COVID-19 booster vaccine willingness. Dan Med J. 2022 Dec 7;69(1):A10210765.

- Bono SA, Faria de Moura Villela E, Siau CS, Chen WS, Pengpid S, Hasan MT, Sessou P, Ditekemena JD, Amodan BO, Hosseinipour MC. Factors affecting COVID-19 vaccine acceptance: an international survey among low-and middle-income countries. Vaccines. 2021 May 17;9(5):515.

- Zhu XM, Yan W, Sun J, Liu L, Zhao YM, Zheng YB, Que JY, Sun SW, Gong YM, Zeng N. Patterns and influencing factors of COVID-19 vaccination willingness among college students in China. Vaccine. 2022 May 11;40(22):3046–54.

- Lai X, Zhu H, Wang J, Huang Y, Jing R, Lyu Y, Zhang H, Feng H, Guo J, Fang H Public perceptions and acceptance of COVID-19 booster vaccination in China: a cross-sectional study. Vaccines. 2021 Dec;9(12):1461. doi:10.3390/vaccines9121461.

- CDC. Possible side effects. 2022 Jan 12. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/vaccines/expect/after.html#: :text=So%20far%2C%20reactions%20reported%20after,effects%20were%20mild%20to%20moderate.

Appendix

Appendix 1. Survey questionnaire

Multi-dimensional factors influencing the willingness to receive COVID-19 vaccine booster: A survey among public in Mainland China

Section A Socio- demographic characteristics

Section B Experience with previous COVID-19 vaccination

Section C Perceived safety concern of COVID-19 vaccine booster

Section D Perceives threat (susceptibility and severity) of COVID-19 infection

Section E Vaccine confidence

Section F Institutional Trust

Section G Willingness to receive a COVID-19 vaccine booster