ABSTRACT

Respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) is a leading cause of bronchiolitis and pneumonia in children under one year and a leading cause of infant hospitalization. Palivizumab was approved by the FDA in 1998 as RSV immunoprophylaxis to prevent severe RSV disease in children with specific health conditions and those born at <35 weeks gestational age (wGA). This study compared RSV-related hospitalization (RSVH) and RSVH characteristics in very preterm (<29 wGA) and term (>37 wGA) infants. Using the MarketScan Commercial and Multi-State Medicaid administrative claims databases, infants born between 7/1/2003 and 6/30/2020 were identified and classified as very preterm or term. Infants with evidence of health conditions, such as congenital heart disease and cystic fibrosis, were excluded. During 2003–2020 RSV seasons (November to March), claims incurred by infants while they were <12 months old were evaluated for outpatient administration of palivizumab and RSVH. The study included 40,123 very preterm infants and 4,421,942 term infants. Rate of RSVH in very preterm infants ranged 1.5–3.8 per 100 infant-seasons in commercially insured infants and 3.5–8.4 in Medicaid insured infants and were inversely related to wGA at birth. Relative risk of RSVH in very preterm was 3–4 times higher, and ICU admissions and mechanical ventilation were more common during RSVH in very preterm infants relative to term infants. However, these outcomes were less common or less severe in very preterm infants who received outpatient palivizumab administration, despite evidence of higher baseline risk of RSVH in these infants.

Introduction

Respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) is a leading cause of bronchiolitis and pneumonia in children under one year.Citation1 RSV infections are a leading cause of hospitalizations among infants and children in the U.S.Citation2–5 and in particular, infants born prematurely and those with bronchopulmonary dysplasia or congenital heart disease are at higher risk for infection and related hospitalizations.Citation1–6-Citation9 Infants born preterm have the highest rates of RSV infection and related hospitalizations,Citation10–13 with infants of gestational age less than 29 weeks (i.e., very preterm) being particularly vulnerable to adverse outcomes associated with RSV infection. Rates of RSV hospitalization (RSVH) in very preterm infants are consistently higher than those of moderately preterm or term infants.Citation1,Citation14,Citation15

Palivizumab was approved by the FDA in 1998 as RSV immunoprophylaxis to prevent severe RSV disease in children with specific health conditions and those born at <36 0/7 weeks gestational age (wGA). Previous studies have demonstrated a reduction in the risk of hospitalization due to severe RSV infection by the administration of palivizumab, an intramuscular injection, which is administered monthly during the RSV season.Citation7–16–Citation19 The American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Infectious Diseases (AAP COID) Policy on RSV prophylaxis recommends palivizumab prophylaxis for infants born at <29 wGA who are younger than 12 months at the start of the RSV season.Citation16 Infants born at 29 wGA or later may be eligible for palivizumab based on the presence of conditions that put them at high-risk for RSV infection (e.g., bronchopulmonary dysplasia (BPD) and chronic lung disease of prematurity (CLD)).Citation20 In infants <29 wGA, palivizumab prophylaxis has been consistently recommended since 1998 despite changes in the recommendations for other preterm infants.

Previous research has described trends in palivizumab use and RSVH among term and preterm infants,Citation6–27 but limited data are available for very preterm infants.Citation10–12 The primary objective of the current study is to characterize palivizumab prophylaxis and risk of RSVH among very preterm (<29 wGA) infants and to compare the RSVH course among very preterm infants. We also described trends in outpatient palivizumab administration and RSVH in very preterm infants in the 2003–2020 RSV seasons.

Methods

Data source

This retrospective observational cohort used de-identified claims from infant patients in the Merative MarketScan Commercial and Multi-State Medicaid administrative claims databases. The commercial database contains claims representing inpatient, outpatient, and outpatient prescription drug experience of patients covered under a variety of fee-for-service and managed care health plans. The Medicaid database represents the healthcare experience of Medicaid enrollees from multiple geographically diverse states. All database records were de-identified and fully compliant with United States patient confidentiality requirements, including the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) of 1996. Merative MarketScan Research Databases are available to purchase by federal, nonprofit, academic, pharmaceutical, and other researchers. Use of the data is contingent on completing a data use agreement and purchasing the data needed to support the study. The study used only de-identified patient records and did not involve the collection, use, or transmittal of individually identifiable data. Thus, Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval was not sought.

Patient selection and cohort assignment

Infants born between 7/1/2003 and 6/30/2020 at less than 29 wGA (very preterm) or greater than 37 wGA (term) and discharged alive were identified using the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) and International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-10-CM) diagnosis codes and Diagnosis-Related Group (DRG) codes on inpatient claims. Infants with a DRG indicating they were born at term (≥37 wGA) with no major health problems were classified as term. Gestational age at birth was assessed as a categorical variable (<25wGA, 25–26 wGA, 27–28 wGA, ≥ 37 wGA), and determined using ICD-9-CM or ICD-10-CM codes on medical claims that indicated gestational age at birth. Infants with evidence of health conditions, such as congenital heart disease and cystic fibrosis, were excluded. Only very preterm or term infants who were traceable from birth were included in the study. Infants were followed from birth through the first year of life, end of continuous enrollment, or inpatient death, whichever was earliest.

Variables

Demographic and birth characteristics were assessed during the birth hospitalization; RSVH characteristics were described during RSVH. The number of contributed infant-seasons were calculated as the days of follow-up during the RSV season (November to March) while <12 months old divided by the number of days in an RSV season (151 days). During RSV seasons (November to March) from 2003 to 2020, claims incurred by infants while they were <12 months old were evaluated for outpatient administration of palivizumab and RSVH. Outpatient palivizumab administration was identified using National Drug Codes (NDC), and the proportion of infants with outpatient palivizumab use was calculated among infants less than 12 months old during an RSV season. Infants with at least one outpatient claim for palivizumab administration were included in the palivizumab cohort. RSVH were identified on inpatient claims with a diagnosis of RSV (ICD-9-CM: 079.6, 466.11, or 480.1; ICD-10-CM: B974, J121, J205, or J210) in any position during an RSV season. RSVH rates for infants are presented as the number of hospitalizations per 100 infant-seasons to account for the variable follow-up.

Analysis

All analyses were conducted separately in commercially insured and Medicaid insured infants. Baseline demographic and birth characteristics were described during the birth hospitalization in very preterm infants by palivizumab use and compared to term infants. Bivariate analyses were conducted to test for differences in outcomes in very preterm infants by palivizumab use (with versus without palivizumab) and to compare outcomes in very preterm and term infants using Chi-square or Fisher’s exact tests for nominal/categorical variables and t-tests for interval/continuous variables. The relative risk of RSVH and 95% confidence intervals were calculated overall and for three wGA strata (<25 wGA, 25–26 wGA, 27–28 wGA) to compare the risk of RSVH in very preterm and term infants.

Results

The number of infants and infant-seasons by the payer and palivizumab use is provided in . Among the commercially insured infants, 13094 were born at <29 wGA and contributed 9,631 infant-seasons during the study period; 1,925,658 term infants contributing 1.7 million infant seasons were also included in the study. Roughly twice the number of very preterm infants were identified in the Medicaid database; 27029 infants born at <29 wGA were identified and contributed 20,346 infant-seasons; 2,496,284 term infants, contributing 2.4 million infant-seasons were included.

Table 1. Number of infants and infant-seasons contributed by palivizumab use and payer.

shows the demographic characteristics of term and very preterm infants by outpatient palivizumab use and payer. The overall rate of outpatient palivizumab administration in very preterm infants was similar in commercially insured (57.1%), and Medicaid insured (56.2%) infants. Inpatient palivizumab administration was not captured in this database. Demographic characteristics were similar in preterm and term infants regardless of whether palivizumab was received in both the commercially insured and Medicaid insured cohorts. However, differences in the geographic distribution of commercially insured infants with and without palivizumab were observed with lower rates of palivizumab use among infants in the North Central region. Very preterm infants were more commonly Black or of other race, and palivizumab use was more common in White infants in the Medicaid insured infants ().

Table 2. Infant demographic characteristics of term and very preterm infants by palivizumab use and payer.

Birth characteristics for very preterm infants with and without palivizumab use are shown in . In the commercially insured population, infants who received palivizumab had significantly longer birth hospitalizations (80.7 vs. 69.2 days, p < .001), higher rates of NICU stays (99.5% vs. 93.5%, p < .001), and higher use of mechanical ventilation (39.8% vs. 36.8%, p < .001). CLD (8.4% vs. 4.9%, p < .001) and BPD (10.0% vs. 8.7%, p = .011) were also more common among infants with outpatient palivizumab use. A similar pattern was found among infants in the Medicaid population. The infants who received palivizumab in the outpatient setting following their birth discharge had longer birth hospitalizations (80.5 vs. 67.3 days, p < .001), higher rates of NICU stays (99.6% vs. 95.5%, p < .001) and higher rates of mechanical ventilation (40.0% vs. 36.3%, p < .001).

Table 3. Birth characteristics of very preterm infants by palivizumab use and payer.

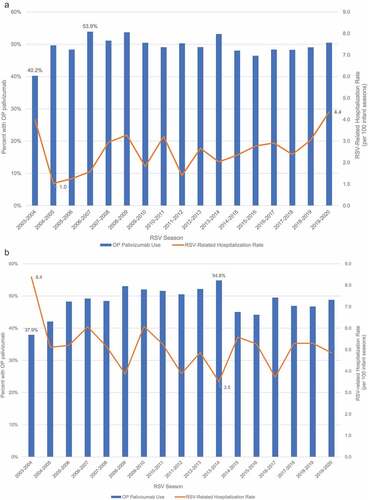

shows the proportion of very preterm infants with outpatient palivizumab use and the rate of RSVH from 2003 to 2020 RSV seasons. Rates of outpatient palivizumab administration ranged from a low of 40.2% in the 2003–2004 RSV season to 53.9% in the 2006–2007 season in the commercial population, and from 37.9% (2003–2004) to 54.8% (2013–2014) in the Medicaid population. Rates of RSVH ranged from 1.0 (2004–2005) to 4.4 (2019–2020) hospitalizations per 100 infant seasons in the commercial population. Rates of RSVH were higher in the Medicaid population, ranging from as high as 8.4 (2003–2004) to a low of 3.5 per 100 infant-seasons (in 2013–2014).

Figure 1. Outpatient palivizumab use and rate of RSV-related hospitalizations (per 100 infant seasons) by RSV season: 2003–2020.

RSVH characteristics of very preterm infants by palivizumab use are shown in . In the commercially insured population, 2.4% of infants with palivizumab use and 1.4% of infants without palivizumab use had RSVH in the first 12 months of life. However, length of stay for RSVH was significantly shorter in very preterm infants with palivizumab use (7.4 days vs 9.0 days; p < .001). Though rates of ICU admission were similar among commercially insured infants, the length of ICU admission was significantly shorter (9.5 versus 13.7 days, p = .0081) in infants with palivizumab use. Similar trends were observed with other measures of RSVH severity in the commercially insured population (e.g., lower costs, lower rates of mechanical ventilation), but these differences were not statistically significant.

Table 4. RSV hospitalization characteristics of very preterm infants by palivizumab use and payer.

A higher proportion of infants with RSVH in the first year of life was observed in the Medicaid insured population than in the commercially insured population, regardless of palivizumab use. As seen in the commercially insured population, a higher proportion of Medicaid-insured infants who received palivizumab were hospitalized for RSV within their first 12 months following birth (4.4% vs. 3.2%). Length of stay for RSVH in Medicaid-insured infants was also significantly shorter among very preterm infants with palivizumab use (8.1 days vs. 10.8 days; p = .019). In addition, significantly lower rates of ICU admission (35.6% vs. 44.7%; p = .002), mechanical ventilation (2.8% vs 6.0%; p = .007), and death (0.1% vs 1.3%; p = .011) were observed in Medicaid insured very preterm infants with palivizumab administration.

Birth characteristics of very preterm and term infants are compared in . In the commercially insured population, very preterm infants had markedly longer birth hospitalizations on average than term infants (76.1 days vs. 3.0 days,), much greater rates of NICU admission (97.1% vs. 1.3%), and greater rates of mechanical ventilation (38.6% vs. 0.2%) (p < .001 for all). Differences in the birth characteristic of very preterm and term infants in the Medicaid-insured population were similar, with significantly longer birth hospitalizations (75.1 days vs. 3.1 days) and higher rates of NICU admission (97.9% vs. 1.3%) and mechanical ventilation (38.5% vs. 0.2%) observed in very preterm infants.

Table 5. Birth characteristics of term and very preterm infants by payer.

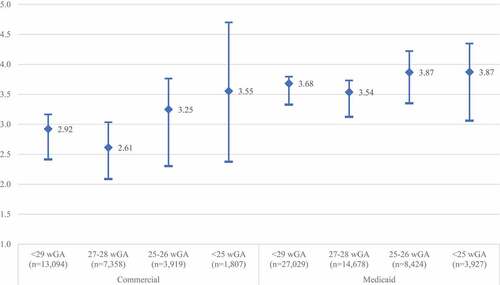

In both the commercial and Medicaid cohorts, the rate of RSVH among preterm infants were significantly higher than those observed in term infants (). Commercially insured infants born at less than 29 wGA were nearly three times more likely to have RSVH in the first year of life relative to term infants (RR: 2.92; 95% CI: 2.41–3.17). In Medicaid-insured infants, rates of RSVH were more than three and a half times the rate in term infants (RR: 3.68; 95% CI: 3.33–3.80). The relative risk of RSVH was inversely related to wGA at birth in both the commercially insured and Medicaid insured populations, with the highest relative risk observed in infants <25 wGA at birth.

describes RSVH characteristics of term and very preterm infants. The total number of infants hospitalized were higher in term infants. Overall, 15,694 (0.8%) commercially insured term infants and 279 (2.1%) of commercially insured very preterm infants had an RSVH. Among Medicaid insured, 34,167 (1.4%) term infants and 1,154 (4.3%) very preterm infants had an RSVH. In the commercially insured population, the cost of RSVH was more than four times higher for infants born at less than 29 wGA, length of stay doubled, rate of ICU admissions tripled, and use of mechanical ventilation was more common in very preterm infants. Results were similar in the Medicaid population. In particular, cost of RSVH was more than four times higher for infants born at less than 29 wGA, length of stay doubled, rate of ICU admissions nearly tripled, and use of mechanical ventilation was more common in very preterm infants. Death was also more common in very preterm infants, though the number of events was low in both term and very preterm infants.

Table 6. RSV hospitalization characteristics of term and very preterm infants by payer.

Discussion

The very preterm infants included in this study were more medically fragile at birth relative to term infants, with significantly longer birth admission and higher NICU utilization and use of mechanical ventilation in very preterm infants. This study showed significantly higher rates of RSVH during the 2003–2020 RSV seasons in these medically fragile, very preterm infants relative to term infants in both commercially insured and Medicaid insured populations. In addition, RSVHs in very preterm infants were more severe compared to term infants, as they were longer in duration and significantly more likely to include ICU admissions and use of mechanical ventilation. CLD and BPD, were both more common at birth among very preterm infants who received palivizumab prophylaxis, indicating a higher baseline risk of RSVH in infants who received palivizumab prophylaxis. However, RSVH tended to be less serious or of shorter duration among the commercial and the Medicaid insured very preterm infants who received palivizumab prophylaxis, despite the higher baseline risk of RSVH.

Though rates of RSVH were significantly higher and RSVH was more severe in very preterm infants, it is important to note that the overall number of term infants with RSVH was much higher than number of term infants. Therefore, despite the higher overall risk of RSVH, mechanical ventilation, and RSVH ICU admission in very preterm infants, the burden of RSVH in term infants remains an important consideration when describing the overall burden of RSVH. Nonetheless, the morbidity associated with RSVH in very preterm infants is substantial and this study has shown that outpatient administration palivizumab reduces RSVH severity in very preterm infants.

Prophylactic therapy for RSV in very preterm infants has been consistently recommended by the AAP as these infants are considered medically fragile and at increased risk from RSV infections.Citation16,Citation28 However, less than 60% of commercially insured or Medicaid insured very preterm infants received outpatient prophylactic therapy, resulting in suboptimal protection against severe RSV outcomes. External factors may interfere with adequate administration or result in unpredictable administration schedules. In this study, very preterm infants who received outpatient palivizumab had a longer duration of birth admission higher NICU utilization and use of mechanical ventilation and higher rates of CLD and BPD along with RSVH rates suggesting that those infants may have a higher baseline risk of RSVH and may be more likely to receive palivizumab as a result. However, despite evidence that very preterm infants who received palivizumab were more medically fragile, RSVH tended to be less serious or of shorter duration in both the commercially and Medicaid insured populations with outpatient palivizumab administration.

A decrease in use of palivizumab and increase in RSVH following the 2014 change in AAP policy was observed in this study even though RSV immunoprophylaxis was still recommended in these very preterm infants <29wGA and is consistent with other studies. One study found higher rates of RSVH and lower rates of immunoprophlaxis use in very preterm infants following the change in guidance, but did not compare RSVH outcomes by IP receipt.Citation23 Higher rates of RSVH and lower rates of palivizumab use have also been reported in preterm infants aged 29–34 wGA at birth following the policy change,Citation16,Citation21,Citation24,Citation29 and these changes persisted for five years after the change in guidance.Citation6 Higher rates of ICU admission, mechanical ventilation, and longer hospitalization duration in infants born at 29–34 wGA with RSVH have also been observed following this change in policy.Citation30 Despite consistent evidence of these unintended consequences in very preterm infants, for whom the AAP has consistently recommended palivizumab prophylaxis, AAP policy was renewed without revision in 2019. Specific policy updates emphasizing the importance of RSV immunoprophylaxis in very preterm infants may improve coverage in this medically fragile population and subsequently reduce the incidence of RSVH and decrease RSVH severity.

We found evidence of racial disparities in the use of outpatient palivizumab. Specifically, despite being a higher percentage of the very preterm infants in the Medicaid insured population, Black infants were less likely to be given palivizumab. Because race is not a biological construct, this racial disparity likely indicates that access to outpatient palivizumab may be negatively impacted by race. We did not, however, assess whether barriers to access, ecologic factors, race, or parent and/or provider characteristics were associated with suboptimal coverage of this high-risk population of very preterm infants, and future research on the barriers to palivizumab administration is needed.Citation31,Citation32

This study is subject to limitations common to all retrospective administrative claims studies, such as coding errors and omission of unbilled/over-the-counter services. However, to the extent these errors/omissions occur, we expect them to be non-differential. In addition, data on inpatient administration of palivizumab is not available in this database and only outpatient administrations are measured. Some infants in the subgroup without outpatient palivizumab use may have received palivizumab during the birth hospitalization or during a subsequent hospitalization, resulting in misclassification error. RSVH may have occurred before palivizumab administration in some infants, and infants with a single dose of palivizumab were included, though the recommended regimen is monthly. Finally, the study was restricted to commercially or Medicaid-insured infants, and the findings may not extend to infants with other insurance or no insurance.

Notwithstanding these limitations, this study extends the existing literature by demonstrating higher rates of RSVH and poorer RSVH outcomes in very preterm infants relative to term infants in both commercially insured and Medicaid-insured populations. Though prior studies have described the rates of palivizumab use and RSVH among infants born at 29–34 wGA, the sample size for the <29wGA was not sufficiently powered to conduct statistical comparisons in all populations and RSVH outcomes (length of stay, use of mechanical ventilation, and ICU admission) were not compared in infants with and without palivizumab administration.Citation6,Citation23,Citation24 The current study utilized data from 2003 to 2020, which provided a sufficient sample size to compare use of palivizumab and RSVH rates in very preterm and term infants. Despite evidence that palivizumab reduces RSVH severity, rates of outpatient palivizumab utilization were suboptimal among very preterm infants throughout the study period. Targeted interventions to increase provider and parent awareness and remove barriers to access, particularly among Medicaid patients, may improve RSV immunoprophylaxis coverage in medically fragile, preterm infants.

Abbreviations

| BPD | = | bronchopulmonary dysplasia |

| CLD | = | chronic lung disease of prematurity |

| ICU | = | intensive care unit |

| RSVH | = | RSV-related hospitalization |

| wGA | = | weeks gestational age |

Ethics approval and informed consent

All database records are statistically de-identified and certified to be fully compliant with US patient confidentiality requirements set forth in the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996. Because this study used only de-identified patient records and did not involve the collection, use, or transmittal of individually identifiable data, this study was exempted from Institutional Review Board approval.

Acknowledgments

Medical writing services were provided by James Nelson and Heather Larkin of Merative (IBM Watson Health when the study was conducted). Programming services were provided by David Diakun of Merative. These services were paid for by Sobi, Inc.

Disclosure statement

Abiola Oladapo and Matthew Wojdyla are employees of Sobi Inc. Tara Gonzales was an employee of Sobi, Inc. at the time of this study, and is now affiliated with Veru Inc. Elizabeth Packnett, Isabelle Winer, and Heather Larkin are employees of Merative (IBM Watson Health when the study was conducted) which received funding from Sobi, Inc. to conduct this study. Mitchell Goldstein and Vincent C. Smith are paid consultants of Sobi, Inc. This research was presented in part at the 2022 38th Annual Advances in Care Conference – Advances in Therapeutics and Technology: Critical Care of Neonates, Children, and Adults in Snowbird, Utah.

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from Merative. Restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under license for this study.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Figueras-Aloy J, Manzoni P, Paes B, Simões EAF, Bont L, Checchia PA, Fauroux B, Carbonell-Estrany X. Defining the risk and associated morbidity and mortality of severe respiratory syncytial virus infection among preterm infants without chronic lung disease or congenital heart disease. Infect Dis Ther. 2016;5(4):1–9. doi:10.1007/s40121-016-0130-1.

- Leader S, Kohlhase K. Recent trends in severe respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) among US infants, 1997 to 2000. J Pediatr. 2003;143(5 Suppl):S127–132. doi:10.1067/S0022-3476(03)00510-9.

- Shi T, McAllister DA, O’Brien KL, Simoes EAF, Madhi SA, Gessner BD, Polack FP, Balsells E, Acacio S, Aguayo C, et al. Global, regional, and national disease burden estimates of acute lower respiratory infections due to respiratory syncytial virus in young children in 2015: a systematic review and modelling study. Lancet. 2017;390(10098):946–58. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30938-8.

- Hall CB. The burgeoning burden of respiratory syncytial virus among children. Infect Disord Drug Targets. 2012;12(2):92–97. doi:10.2174/187152612800100099.

- Hall CB, Weinberg GA, Iwane MK, Blumkin AK, Edwards KM, Staat MA, Auinger P, Griffin MR, Poehling KA, Erdman D, et al. The burden of respiratory syncytial virus infection in young children. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(6):588–98. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa0804877.

- Kong AM, Winer IH, Zimmerman NM, Diakun D, Bloomfield A, Gonzales T, Fergie J, Goldstein M, Krilov LR. Increasing rates of RSV hospitalization among preterm Infants: a decade of data. Am J Perinatol. 2021. doi:10.1055/s-0041-1736581.

- García CG, Bhore R, Soriano-Fallas A, Trost M, Chason R, Ramilo O, Mejias A. Risk factors in children hospitalized with RSV bronchiolitis versus non–RSV bronchiolitis. Pediatrics. 2010;126(6):e14530e11460. doi:10.1542/peds.2010-0507.

- Welliver RC. Review of epidemiology and clinical risk factors for severe respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) infection. J Pediatr. 2003;143(5 Suppl):S112–117. doi:10.1067/S0022-3476(03)00508-0.

- Agha R, Avner JR. Delayed seasonal RSV surge observed during the COVID-19 pandemic. Pediatrics. 2021;148(3). doi:10.1542/peds.2021-052089.

- Sucasas Alonso A, Pertega Diaz S, Saez Soto R, Avila-Alvarez A. Epidemiology and risk factors for bronchopulmonary dysplasia in premature infants born at or less than 32 weeks of gestation. An Pediatr (Engl Ed). 2021. doi:10.1016/j.anpedi.2021.03.002.

- Bell EF, Hintz SR, Hansen NI, Bann CM, Wyckoff MH, DeMauro SB, Walsh MC, Vohr BR, Stoll BJ, Carlo WA, et al. Mortality, in-hospital morbidity, care practices, and 2-year outcomes for extremely preterm infants in the US, 2013-2018. JAMA. 2022;327(3):248–63. doi:10.1001/jama.2021.23580.

- Stoll BJ, Hansen NI, Bell EF, Walsh MC, Carlo WA, Shankaran S, Laptook AR, Sánchez PJ, Van Meurs KP, Wyckoff M, et al. Trends in care practices, morbidity, and mortality of extremely preterm neonates, 1993-2012. JAMA. 2015;314(10):1039–51. doi:10.1001/jama.2015.10244.

- Taylor GL, O’Shea TM. Extreme prematurity: risk and resiliency. Curr Probl Pediatr Adolesc Health Care. 2022;52(2):101132. doi:10.1016/j.cppeds.2022.101132.

- Haerskjold A, Kristensen K, Kamper-Jorgensen M, Nybo Andersen AM, Ravn H, Graff Stensballe L. Risk factors for hospitalization for respiratory syncytial virus infection: a population-based cohort study of Danish children. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2016;35(1):61–65. doi:10.1097/INF.0000000000000924.

- Heikkinen T, Valkonen H, Lehtonen L, Vainionpaa R, Ruuskanen O. Hospital admission of high risk infants for respiratory syncytial virus infection: implications for palivizumab prophylaxis. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2005;90(1):F64–68. doi:10.1136/adc.2003.029710.

- American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Infectious D, American Academy of Pediatrics Bronchiolitis Guidelines C. Updated guidance for palivizumab prophylaxis among infants and young children at increased risk of hospitalization for respiratory syncytial virus infection. Pediatrics. 2014;134(2):e620–638. doi:10.1542/peds.2014-1666.

- IMpact-RSV Study Group. Palivizumab, a humanized respiratory syncytial virus monoclonal antibody, reduces hospitalization from respiratory syncytial virus infection in high-risk infants. Pediatrics. 1998;102:531–37. doi:10.1542/peds.102.3.531.

- Andabaka T, Nickerson JW, Rojas-Reyes MX, Rueda JD, Vrca VB, Barsic B. Monoclonal antibody for reducing the risk of respiratory syncytial virus infection in children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;30(4). doi:10.1002/14651858.CD006602.pub4.

- Prevention of respiratory syncytial virus infections: indications for the use of palivizumab and update on the use of RSV-IGIV. American academy of pediatrics committee on infectious diseases and committee of fetus and newborn. Pediatrics. 1998;102(5):1211–16. doi:10.1542/peds.102.5.1211.

- Meissner HC, Long SS, American academy of pediatrics committee on infectious D, committee on F, Newborn. Revised indications for the use of palivizumab and respiratory syncytial virus immune globulin intravenous for the prevention of respiratory syncytial virus infections. Pediatrics. 2003;112(6 Pt 1):1447–52. doi:10.1542/peds.112.6.1447.

- Kong AM, Krilov LR, Fergie J, Goldstein M, Diakun D, Wade S, Pavilack M, McLaurin K. The 2014–2015 national impact of the 2014 American academy of pediatrics guidance for respiratory syncytial virus immunoprophylaxis on preterm infants born in the United States. Am J Perinatol. 2018;35(2):192–200. doi:10.1055/s-0037-1606352.

- Fergie J, Goldstein M, Krilov LR, Wade SW, Kong AM, Brannman L. Update on respiratory syncytial virus hospitalizations among U.S. preterm and term infants before and after the 2014 American Academy of Pediatrics policy on immunoprophylaxis: 2011-2017. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2021;17(5):1536–45. doi:10.1080/21645515.2020.1822134.

- Goldstein M, Krilov LR, Fergie J, Brannman L, Wade SW, Kong AM, Ambrose CS. Unintended consequences following the 2014 American academy of pediatrics policy change for palivizumab prophylaxis among infants born at less than 29 weeks’ gestation. Am J Perinatol. 2021;38(S 01):e201–06. doi:10.1055/s-0040-1709127.

- Goldstein M, Krilov LR, Fergie J, McLaurin K, Wade S, Diakun D, Lenhart G, Bloomfield A, Kong A. Respiratory syncytial virus hospitalizations among U.S. preterm infants compared with term infants before and after the 2014 American Academy of Pediatrics Guidance on Immunoprophylaxis: 2012–2016. Am J Perinatol. 2018;35(14):1433–42. doi:10.1055/s-0038-1660466.

- Fergie J, Suh M, Jiang X, Fryzek JP, Gonzales T. Respiratory syncytial virus and all-cause bronchiolitis hospitalizations among preterm infants using the pediatric health information system (PHIS). J Infect Dis. 2022;225(7):1197–204. doi:10.1093/infdis/jiaa435.

- Rajah B, Sanchez PJ, Garcia-Maurino C, Leber A, Ramilo O, Mejias A. Impact of the updated guidance for palivizumab prophylaxis against respiratory syncytial virus infection: a single center experience. J Pediatr. 2017;181:183–8 e181. doi:10.1016/j.jpeds.2016.10.074.

- Gross I, Siedner-Weintraub Y, Abu Ahmad W, Bar-Oz B, Eventov-Friedman S. National evidence in Israel supporting reevaluation of respiratory syncytial virus prophylactic guidelines. Neonatology. 2017;111(3):240–46. doi:10.1159/000452196.

- Hall CB, Weinberg GA, Blumkin AK, Edwards KM, Staat MA, Schultz AF, Poehling KA, Szilagyi PG, Griffin MR, Williams JV, et al. Respiratory syncytial virus–associated hospitalizations among children less than 24 months of age. Pediatrics. 2013;132(2):e341–348. doi:10.1542/peds.2013-0303.

- Krilov LR, Fergie J, Goldstein M, Brannman L. Impact of the 2014 American Academy of pediatrics immunoprophylaxis policy on the rate, severity, and cost of respiratory syncytial virus hospitalizations among preterm infants. Am J Perinatol. 2020;37(2):174–83. doi:10.1055/s-0039-1694008.

- Krilov LR, Forbes ML, Goldstein M, Wadhawan R, Stewart DL. Severity and cost of RSV hospitalization among US preterm infants following the 2014 American Academy of pediatrics policy change. Infect Dis Ther. 2021;10(Suppl 1):27–34. doi:10.1007/s40121-020-00389-0.

- Ricco M, Ferraro P, Peruzzi S, Zaniboni A, Ranzieri S. Respiratory syncytial virus: knowledge, attitudes and beliefs of general practitioners from North-Eastern Italy (2021). Pediatr Rep. 2022;14(2):147–65. doi:10.3390/pediatric14020021.

- Weiner JH. Respiratory syncytial virus infection and palivizumab: are families receiving accurate information? Am J Perinatol. 2010;27(3):219–23. doi:10.1055/s-0029-1239493.