ABSTRACT

Australia’s COVID-19 vaccine rollout included prioritizing older adults and those with underlying conditions. However, little was known around the factors impacting their decision to accept the vaccine. This study aimed to assess vaccine intentions, information needs, and preferences of people prioritized to receive the COVID-19 vaccine at the start of the Australian vaccine rollout. A cross-sectional online survey of people aged ≥70 years or 18–69 with chronic or underlying conditions was conducted between 12 February and 26 March 2021 in Victoria, Australia. The World Health Organization Behavioural and Social Drivers of COVID-19 vaccination framework and items informed the survey design and framing of results. Bivariate logistic regression was used to investigate the association between intention to accept a COVID-19 vaccine and demographic characteristics. In total, 1828 eligible people completed the survey. Intention to vaccinate was highest among those ≥70 years (89.6%, n = 824/920) versus those aged 18–69 years (83.8%, n = 761/908), with 91% (n = 1641/1803) of respondents agreeing that getting a COVID-19 vaccine was important to their health. Reported vaccine safety (aOR 1.4, 95% CI 1.1 to 1.8) and efficacy (aOR 1.9, 95% CI 1.5 to 2.3) were associated with intention to accept a COVID-19 vaccine. Concerns around serious illness, long-term effects, and insufficient vaccine testing were factors for not accepting a COVID-19 vaccine. Preferred communication methods included discussion with healthcare providers, with primary care providers identified as the most trusted information source. This study identified factors influencing the prioritized public’s COVID-19 vaccine decision-making, including information preferences. These details can support future vaccination rollouts.

Introduction

The first Australian confirmed COVID-19 case was reported on 25 January 2020.Citation1 By the end of 2020, Australia had recorded 28,408 cases and 909 deaths.Citation2 One of the key components of the Australian emergency response plan for COVID-19 was approval and implementation of a SARS-CoV-2 vaccine when available.Citation3 Australia’s COVID-19 vaccine national rollout commenced on 22 February 2021 using an age and risk-based approach. The Australian Government’s strategy prioritized frontline healthcare workers, aged care workers and quarantine facility employees in the initial Phase (1a) of the vaccine roll out when vaccine supply was very limited.Citation4 In Phase 1b, prioritized members of the public included elderly adults aged 70 years and over, and adults aged over 18 years with an underlying medical condition or disability. The COVID-19 vaccines were mainly delivered via hospital and primary care-based vaccination programs or through residential aged care or disability care facilities.

Implementing effective communication strategies to build public confidence in vaccine safety and effectiveness is critical to the success of a vaccination program.Citation5–8 Previous studies addressing reasons for low vaccine coverage rates among healthcare workers,Citation9 parental COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy for their childrenCitation10 and hesitancy amongst other populations globallyCitation11 have demonstrated the importance of effective vaccine communication and public health interventions to increase vaccine uptake. However, at the start of the Australian vaccine rollout in February 2021, little was known about the factors impacting decision-making of individuals initially prioritized to receive the vaccine in Australia. Therefore, to inform public health vaccine communication strategies, we aimed to assess vaccine intentions, concerns, information needs, and decision-making factors for individuals prioritized to receive COVID-19 vaccines at the start of the vaccine rollout in Victoria, Australia.

Materials and methods

Study design and context

This study was part of a larger mixed methods study conducted in Victoria, Australia between 12 February and 26 March 2021, early in the Australian vaccine rollout. The larger study involved surveys, interviews and stakeholder feedback sessions with healthcare workers, aged care workers, and members of the prioritized population groups. Detailed study design, recruitment and a sampling framework for the larger mixed methods study were described elsewhere.Citation12,Citation13 For the survey study described here, we utilized a quantitative cross-sectional design comprising of an online survey to understand COVID-19 vaccine intentions and factors influencing uptake in the target groups.

Data collection

The survey included 38 items, including 14 screening or demographic items. We used/adapted twelve items from the World Health Organization Behavioural and Social Drivers of Immunization (BeSD) of COVID-19 vaccination survey,Citation14 which has been validated and applied in several countries.Citation15 BeSD items addressed the domains of thinking and feeling (e.g., ‘How concerned are you about getting COVID-19?’), motivations (e.g., ‘If a COVID-19 vaccine were recommended for you, would you get it?), social processes (e.g., ‘Do you think most of your close family and friends would want you to get a COVID-19 vaccine?’) and practical issues (e.g., ‘Where would you prefer to get a COVID-19 vaccine?’). Additional items developed by the research team assessed information needs and preferences and specific factors participants felt were relevant to their decision-making. For multi-select questions, responses were presented in order of frequency of selection. Some multi-select questions (e.g., who do you trust to provide information about COVID-19 vaccines) were limited to two selections to force prioritization. No questions were mandatory. The survey was not pilot tested, but it was reviewed by experts outside the study team and representatives from the Victorian Department of Health, resulting in edits to reduce length and improve question clarity. Please see Appendix A for complete patient questionnaire.

Two metropolitan and two regional Victorian general practices (primary care practices with general practitioners), who are members of The Victorian Primary Care Practice-based Research and Education Network (VICREN) at The University of Melbourne, were approached to assist with study recruitment. Eligible patients were identified via the general practice extraction tool (Pen CS)Citation16 at each general practice. Study advertisements were sent to approximately 18,000 eligible people (≥70 years old and 18–69 years old with underlying medical conditions or disabilities) via short messaging service (SMS). General practices were reimbursed for SMS costs and each practice also received an AUD$500 payment for staff time required to set up and distribute the messages. Prioritized publics were also recruited through condition-specific consumer groups (e.g., organizations related to heart disease, respiratory conditions, cancer, diabetes, immunocompromising conditions, or chronic kidney or liver disease) across Victoria, Australia. Those interested in participating could click on the link provided in the advertisement or SMS which took them to the information sheet and survey. The 10-minute survey was administered online via REDCap.Citation17 Consent was implied upon completion of the survey. All respondents were eligible to be in the draw for one of eight AUD$75 gift cards. Those who wished to be in the draw were asked to provide contact details via a separate REDCap link to ensure participant anonymity.

Ethical approval to conduct this study was granted by the Royal Children’s Hospital Human Research Ethics Committee (HREC/72845/RCHM-2021).

Data analysis

Categorical responses were presented as numbers and percentages for each priority group (i.e., 18–69 years old with underlying medical conditions or disabilities and ≥70 years) or by culturally and linguistically diverse (CALD) status (i.e., born overseas and/or speaking a language other than English at home). Bivariate logistic regressions were used to investigate the association between intention to accept a COVID-19 vaccine and demographic characteristics (i.e., age group, sex, CALD status, education, employment type and remoteness). These demographic characteristics were considered as potential confounders in the relationship between intention to accept a COVID-19 vaccine and other factors (i.e., concerns – How concerned are you about getting COVID-19; beliefs – How much do you think getting a COVID-19 vaccine for yourself will protect other people in your community from COVID-19?; and information – From whom would you prefer to receive information about your personal eligibility for vaccination?), and included in the multivariate logistic regression model to adjust for their influence on the relationship. Given <5% missing data across the surveys that included demographic characteristics, we analyzed complete surveys for regression analysis only.

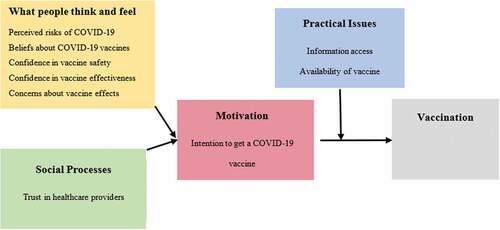

Results were presented according to the BeSD framework () which outlines measurable and modifiable drivers of vaccine uptake. For responses that were relevant to more than one domain of the BeSD framework, results were presented in only one section. Data were analyzed using Stata 16.1.Citation18

Results

A total of 1828 eligible people responded to the survey, 50.3% (n = 920) were aged ≥70 years, 55.6% (n = 999) were female, and 35.7% (n = 636) were from a CALD background. Less than half had undergraduate or postgraduate education (44.2%, n = 767). Among the 908 respondents aged between 18 and 69 years, diabetes (25.2%, n = 229) and respiratory illnesses (23.1%, n = 210) were the most reported chronic or underlying health conditions.

Motivation

Intention to vaccinate (intention to accept a COVID-19 vaccine)

Of those aged ≥70 years, 89.6% (n = 824/920) intended to accept COVID-19 vaccines, as did 83.8% (n = 761/908) of those in the 18–69 age group. Males (90.8%, n = 684/753) were more likely to accept a COVID-19 vaccine compared to females (84.8%, n = 847/999) (Appendix B & ). CALD respondents (83.6%, n = 532/636) were less likely to accept a COVID-19 vaccine compared to non-CALD respondents (88.2%, n = 1011/1146) (Appendix C & ). Similarly, respondents with an educational qualification of trade certificate or diploma (82.9%, n = 345/416) were less likely to report their intention of accepting a COVID-19 vaccine compared to those with the highest educational level of high school (89.9%, n = 425/473). However, intention to accept a vaccine was similar among respondents with other education levels: high school, undergraduate, and postgraduate qualification (Appendix B & ).

Table 1. Respondents demographic factors and experience and concerns associated with vaccine acceptance.

Respondents who reported having been tested for COVID-19 (89.0%, n = 733/824) were more likely to accept a COVID-19 vaccine compared to those who had never been tested (85.1%, n = 850/999). However, it was unclear whether receiving a positive COVID-19 test result would influence intention to receive a COVID-19 vaccine ().

Thinking and feeling

Factors influencing COVID-19 vaccine decisions

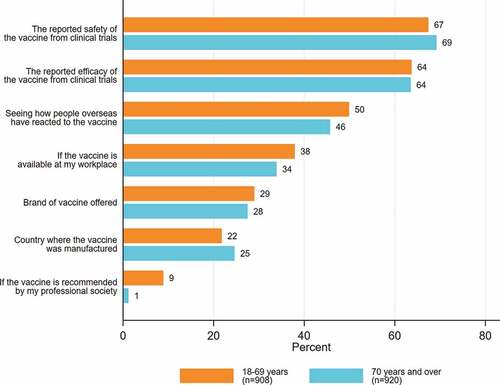

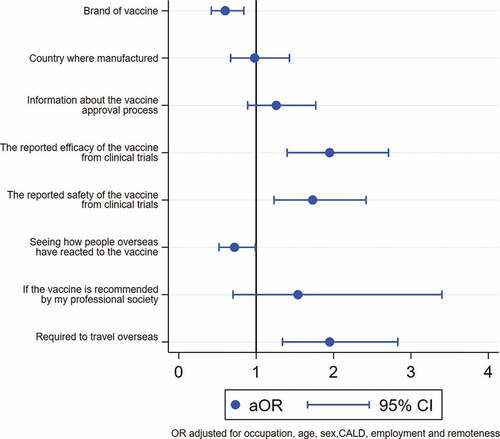

The most frequently reported influences on vaccine decision-making were reported safety and efficacy of the vaccine from clinical trials and seeing how people overseas reacted to the vaccine (). The most frequently reported influential factors were the same for both groups. Reported vaccine safety (adjusted odds ratio (aOR) 1.4, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.1 to 1.8) and efficacy (aOR 1.9, 95% CI 1.5 to 2.3) were associated with intention to accept a COVID-19 vaccine. However, there was not enough evidence in support of the association between seeing how people overseas reacted to the vaccine and intention to accept a COVID-19 (aOR 0.8, 95% CI 0.7 to 1) ().

More people from CALD backgrounds compared to non-CALD backgrounds reported that the vaccine being required to travel overseas was an important decision-making factor (Appendix C). In contrast, more people from non-CALD backgrounds compared to CALD backgrounds reported that the efficacy and safety of the vaccines were important factors (Appendix C).

Only 28.2% (n = 516/1828) of respondents considered the brand of vaccine offered to be important, and the proportions were similar between two priority groups (Appendix B & ) and those between people from CALD and non-CALD backgrounds (Appendix C).

Vaccine concerns for those unsure or not intending to accept the vaccine

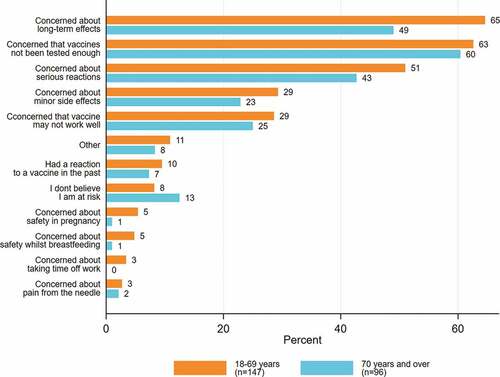

Of the respondents who were unsure or did not intend to accept a COVID-19 vaccine, 61.7% (n = 150/243) were concerned that the vaccines had not been tested enough, 58.4% (n = 142/243) were concerned about the long-term effects of the vaccine, and 48% (n = 116/243) were concerned about serious reactions. The vaccine concerns are presented by priority groups in and Appendix B and by CALD status in Appendix C.

Perceived risks of COVID-19

Fifty-four percent (n = 976/1828) of respondents were concerned that they might get COVID-19; this was similar between both groups (Appendix B). While the intention to receive a COVID-19 vaccine was high even for those who were ‘not at all/a little’ concerned about getting COVID-19 (83.0%, n = 700/843), they were less likely to report their intention to receive a COVID-19 vaccine compared to respondents who were concerned or moderately concerned ().

Beliefs about COVID-19 vaccines

Overall, most respondents trusted COVID-19 vaccines (87.5%, n = 1599/1828), with those aged ≥70 years (91.0%, n = 831/913) reporting higher trust than those aged 18–69 years (85.0%, n = 768/903) with medical conditions (difference 6%, 95% CI 3% to 9%). Ninety-one percent (n = 1641/1803) of respondents believed that getting a COVID-19 vaccine was important to their health, and 89.6% (n = 1616/1804) believed that getting a COVID-19 vaccine would protect others in the community. The majority of respondents believed the COVID-19 vaccine would be safe for them (88.9%, n = 1612/1814), that most of their close family and friends would want them to get a COVID-19 vaccine (81.8%, n = 1485/1815), and that getting a COVID-19 vaccine would allow them to safely see their family and friends again (79.4%, n = 1441/1815) (Appendix B).

Social processes/practical issues

Information about COVID-19 vaccines

Over half of all respondents felt they had enough information about the safety (59.8%, n = 1065/1782) and effectiveness of the COVID-19 vaccines (58.9%, n = 1052/1785), and how the COVID-19 vaccines work (60.9%, n = 1092/1791). However, only 36.5% (n = 649/1776) responded that they had enough information about vaccine side effects. Overall, respondents in the ≥70 years priority group were more likely to agree that they had enough information than the other group (Appendix B).

Communication preferences

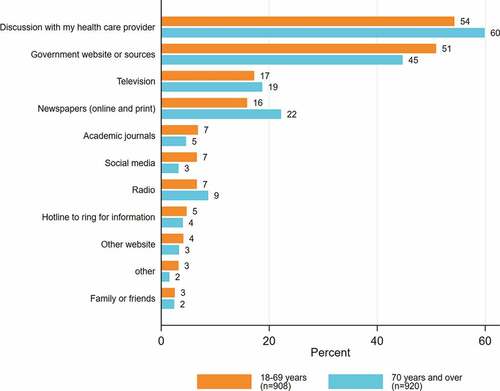

Discussion with their healthcare provider (57.1%, n = 1044/1828) was the most preferred method of receiving COVID-19 vaccine information in both groups. However, compared with people from non-CALD backgrounds (59.4%, n = 681/1146), fewer people from CALD backgrounds (53.1%, n = 338/636) preferred to get information from their healthcare providers. Receiving information from Government websites or sources (47.8%, n = 873/1828) was the second most preferred method (Appendices B, C & ).

In both priority groups, medical professionals (67.3%, n = 1231/1828), respondents’ personal primary healthcare provider (48.7%, n = 891/1828), and scientists or researchers (39.2%, n = 717/1828) were identified as most trusted people from whom to receive information about COVID-19 vaccines. Celebrities or online influencers (0.1%, n = 2/1828) were ranked as the least trusted to provide information about the vaccine.

People from CALD backgrounds reported lower levels of trust in medical professionals, their primary healthcare providers, and scientists/researchers than people from non-CALD backgrounds (Appendix C).

Discussion

This study was among the first to explore vaccine intentions, concerns, information needs, and the decision-making process of prioritized public (18–69 years old with underlying medical conditions or disabilities and those ≥70 years) to receive COVID-19 vaccines in Victoria, Australia. The study was important as the Australian Government prioritized groups in initial phases when vaccine supply was limited. We identified key barriers and enablers to vaccine uptake among these cohorts, which were communicated to the Victorian Department of Health to inform the COVID-19 vaccine rollout.

We found that intention to vaccinate was high in both groups. Males from both groups were more likely to vaccinate than females. While most respondents trusted the COVID-19 vaccines and believed the vaccines provided protection for their health and for others in the community, barriers to accepting a COVID-19 vaccine included concerns around long-term effects of the vaccine and that the vaccines had not been tested enough for safety. Other Australian and international studies have found that vaccine intentions were associated with increasing age, being male, and high self-perceived risk of getting COVID-19.Citation19–22 In particular, perceived risk of disease and community benefits were associated with positive intention to vaccinate, while vaccine safety concerns including side effects and fear of getting sick from the vaccine negatively impacted COVID-19 vaccine acceptance.Citation23–27 Potential disease exposure was also related to intention to vaccinate, with respondents who had a COVID-19 test being more likely to accept a vaccine than those who were not tested.

Beliefs about the safety and efficacy of COVID-19 vaccines were associated with COVID-19 vaccine acceptance. Respondents’ belief that the vaccine would be safe for them and that getting the vaccine would allow them to safely see their family and friends were strongly associated with intention to vaccinate. Recent studies have shown those who did not believe COVID-19 vaccination was useful, low concerns about the severity of COVID-19, and concerns around potential vaccines side effects were likely to be vaccine hesitant.Citation10,Citation22,Citation28 While our study showed that most respondents trusted COVID-19 vaccines, a US study found there was a general lack of trust in the vaccine approval and development processes, leading to higher hesitancy.Citation29 These concerns were also observed in Australia, where the public’s vaccine confidence shifted due to the thrombosis with thrombocytopenia syndrome (TTS) associated with the Oxford/AstraZeneca COVID-19 vaccine. Subsequently, the Australian Technical Advisory Group on Immunisation (ATAGI) made the Pfizer vaccine the preferred vaccine for adults aged <50 years in Australia in April 2021.Citation30–32 Thus, building trust is critical to vaccine uptake, and transparency is important to building that trust.

Trust in medical professionals and primary healthcare providers influenced the general public’s decision to accept COVID-19 vaccines. Our study showed that participants preferred to discuss COVID-19 vaccine information with their healthcare providers, and primary care providers were the most trusted sources of COVID-19 vaccine information. The importance of trust between patients and their healthcare providers cannot be underestimated, with patient trust in their providers directly associated with patient satisfaction, health transparency, and better health outcomes.Citation33–36 Our study also found that responders’ most preferred method of receiving COVID-19 vaccine information was through healthcare providers. This highlighted the pivotal role that healthcare providers can play in promoting vaccination in different settings and specific at-risk groups.Citation28,Citation37 To ensure public confidence in COVID-19 vaccines, healthcare providers must be armed with the most up-to-date, evidence-based, easy to access health information to communicate with the public regarding specific health advice.Citation7,Citation8,Citation38,Citation39

Although our study found that people from CALD backgrounds were less likely to accept a COVID-19 vaccine and reported lower levels of trust in the medical profession than people from non-CALD backgrounds, the overall differences were low (<5% overall difference). However, low health literacy, difficulties accessing health services, and barriers in cross-cultural care can provide additional challenges for CALD communities.Citation40,Citation41 In order to address vaccine hesitancy and increase COVID-19 vaccine uptake in CALD communities, it is imperative that messages are targeted to their specific needs, with appropriate language and literacy levels, and that healthcare providers, such as general practitioners, are supported with evidence-based resources tailored to communicate with their relevant CALD patients.Citation40

Our large sample size, and the ability to target the prioritized public (those who were ≥70 years of age, and those aged between 18 and 69 years with one or more underlying medical conditions) through both metropolitan and regional general practices in Victoria, Australia, was one of the strengths to our study. However, the lack of thorough pilot testing and validation of the questionnaire due to timing, and the broad recruitment strategies used reduced our ability to quantify or describe non-respondents, were identified as limitations to our study. In addition, due to the prioritized public targeted in our study, our sample was not nationally representative. Nonetheless, the survey was timely as it was at the beginning of the vaccine rollout in Australia, so initial vaccine intentions and specific vaccine brand preferences were able to be examined in this cohort. However, due to the safety concerns relating to the AstraZeneca vaccine,Citation42 this may have impacted vaccine brand preferences, intentions, and uptake later in the vaccine rollout, which were not captured in our results.

Eighteen months since the start of the vaccine rollout, Australia has one of the highest COVID-19 vaccine coverage rates in the world, with >96% of people aged 16 years and older fully vaccinated and 71.4% having received their first booster dose.Citation43 The COVID-19 wavesCitation44 (Delta; June 2021, and Omicron; December 2021), and mandatory COVID-19 vaccination policies requiring the majority of workers to be fully vaccinated,Citation45–47 may have contributed to the high COVID-19 vaccine rate. However, the Australian COVID-19 vaccine rollout was not smooth with negative media amplifying hesitancy and reducing public trust around the Oxford/AstraZeneca COVID-19 vaccine early in the programCitation31; confused and mixed messaging around COVID-19 vaccine eligibility, schedules and priority populationsCitation48; and reduced early supply of COVID-19 vaccines which further diminished public confidence.Citation49 Currently, the first dose booster uptake has stalled at 74.1% and there are ongoing challenges with the vaccine rollout for children aged 5–11 and under five years.Citation43 As we transition from a COVID-19 restriction setting to a COVID-safe environment, it is critical that we continue to understand the barriers and drivers to vaccine uptake amongst the public, especially for priority groups, to continue to develop targeted messaging and evidence-based resources. This is especially important as we prepare for future vaccine doses/boosters considering waning immunity and variant-specific vaccines. Communication between Government, healthcare providers and the public around vaccine safety and side effects will be essential to optimize vaccine confidence and uptake in Australia.

Conclusion

This study advances understanding of the COVID-19 vaccine intentions, concerns, information needs, and decision-making factors amongst the prioritized public (≥70 years of age, and those aged between 18 and 69 years with one or more underlying medical conditions) at the start of the Australian vaccine rollout. The intention to vaccinate was high amongst these groups, with concerns around vaccine safety and efficacy, perceived risks and beliefs about COVID-19 vaccines and trust in healthcare providers and government key decision-making factors. Our findings support the need for Government and healthcare providers to provide evidence-based, up-to-date and easy to access information, regarding the risks of COVID-19 and the risks and benefits of COVID-19 vaccines, to deliver a more equitable COVID-19 vaccination program.

Informed consent statement

Informed consent was obtained from all participants through the provision of the Participant Consent and Information Form and subsequent completion of the survey (implied consent).

Institutional review board statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Royal Children’s Hospital Human Research Ethics Committee (HREC/72845/RCHM-2021).

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge the project advisory group members: Stefanie Johnston (Pharmaceutical Society of Australia), Belinda Hibble (Australasian College for Emergency Medicine), Ken Griffin (Australian Primary Health Care Nurses Association), Amy Miller and Melanie Chisholm (Victorian Department of Health), Stephen Peterson (consumer representative), Talei Richards (Victorian Multicultural Commission), Shanthi Gardiner (Australian Primary Health Care Nurses Association) and Deepak Gaur (Australian Medical Association). We would also like to thank the general practices and consumer organizations that supported our recruitment efforts, and the participants who gave their time to our study.

Disclosure statement

J.K., K.B., J.T., D.S.O., C.J., J.O. and M.D.’s institution MCRI receives funding from the Commonwealth and Victorian Department of Health for COVID-19 vaccine social research. J.T. is an investigator on a project grant sponsored by industry. Her institution has received funding from industry (GlaxoSmithKline) for investigator-led research. She does not receive any personal payments from industry. J.S.B. has received grant funding or consulting funds from the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC), Victorian Government Department of Health, Dementia Australia Research Foundation, Yulgilbar Foundation, Aged Care Quality and Safety Commission, Dementia Centre for Research Collaboration, Pharmaceutical Society of Australia, Society of Hospital Pharmacists of Australia, GlaxoSmithKline Supported Studies Programme, Amgen, and several aged care provider organizations unrelated to this work. All grants and consulting funds were paid to the employing institution. H.S. is a listed investigator on studies receiving funding from the NHMRC. She is also receiving funding for investigator-driven research from state government. She has previously received funding from drug companies for investigator-driven research and consulting fees to present at conferences/workshops and develop resources (Seqirus, GlaxoSmithKline and Sanofi Pasteur). M.D. receives funding from the NHMRC. She also sat on the Australian Technical Advisory Group on Immunisation advising the Commonwealth on COVID-19 vaccination communications and confidence and is a Specialist Advisor to the Vaccine Safety Investigation Group of the Therapeutic Goods Administration. J.M.N. receives funding from the NHMRC and MRFF. J.L. receives funds from WHO, UNICEF, CDC and NHMRC. She is a member of the Expert Advisory Group for the Victorian Department of Health and Human Services COVID-19 vaccine rollout.

Data availability statement

Restrictions apply to the availability of these data. Data are available from the authors upon request and with the permission of the Victorian Department of Health.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Victoria State Government Department of Health and Human Services. Victorian coronavirus (COVID-19 data). Victoria, Australia: Victoria State Government Health and Human Services; 2020 [accessed 2022 Oct 10]. https://www.dhhs.vic.gov.au/victorian-coronavirus-covid-19-data.

- Australian Government Department of Health. Coronavirus (COVID-19) at a glance. 2020 [accessed 2022 Oct 10]. https://www.health.gov.au/resources/collections/coronavirus-covid-19-at-a-glance-infographic-collection.

- Australian Government Department of Health and Aged Care. Australian health sector emergency response plan for novel coronavirus (COVID-19). 2022 [accessed 2022 Oct 10]. https://www.health.gov.au/resources/publications/australian-health-sector-emergency-response-plan-for-novel-coronavirus-covid-19.

- Australian Government Department of Health. Australia’s COVID-19 vaccine national roll-out strategy. 2021 [accessed 2022 Jan 18]. https://www.health.gov.au/sites/default/files/documents/2021/01/covid-19-vaccination-australia-s-covid-19-vaccine-national-roll-out-strategy.pdf.

- Al‐metwali BZ, Al‐jumaili AA, Al‐alag ZA, Sorofman B. Exploring the acceptance of COVID‐19 vaccine among healthcare workers and general population using health belief model. J Eval Clin Pract. 2021;27(5):1112–18. doi:10.1111/jep.13581.

- Dror AA, Eisenbach N, Taiber S, Morozov NG, Mizrachi M, Zigron A, Srouji S, Sela E. Vaccine hesitancy: the next challenge in the fight against COVID-19. Eur J Epidemiol. 2020;35(8):775–79. doi:10.1007/s10654-020-00671-y.

- Danchin M, Biezen R, Manski-Nankervis J-A, Kaufman J, Leask J. Preparing the public for COVID-19 vaccines: how can general practitioners build vaccine confidence and optimise uptake for themselves and their patients? Aust J Gen Pract. 2020;49(10):625–29. doi:10.31128/AJGP-08-20-5559.

- Leask J, Carlson SJ, Attwell K, Clark KK, Kaufman K, Hughes C, Frawley J, Cashman P, Seale H, Wiley K, et al. Communicating with patients and the public about COVID‐19 vaccine safety: recommendations from the collaboration on social science and immunisation. Med J Aust. 2021;215(1):9–12.e1. doi:10.5694/mja2.51136.

- Genovese C, Picerno IAM, Trimarchi G, Cannavò G, Egitto G, Cosenza B, Merlina V, Icardi G, Panatto D, Amicizia D, et al. Vaccination coverage in healthcare workers: a multicenter cross-sectional study in Italy. J Prev Med Hyg. 2019;60(1):E12–7. doi:10.15167/2421-4248/jpmh2019.60.1.1097.

- Bianco A, Della Polla G, Angelillo S, Pelullo CP, Licata F, Angelillo IF. Parental COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy: a cross-sectional survey in Italy. Expert Rev Vaccines. 2022;21(4):541–47. doi:10.1080/14760584.2022.2023013.

- Hassan W, Kazmi SK, Tahir MJ, Ullah I, Royan HA, Fahriani M, Nainu F, Rosa SGV. Global acceptance and hesitancy of COVID-19 vaccination: a narrative review. Narra J. 2021;1(3):E57. doi:10.52225/narra.v1i3.57.

- Kaufman J, Bagot KL, Tuckerman J, Biezen R, Oliver J, Jos C, Suryawijaya Ong D, Manski-Nankervis J-A, Seale H, Sanci L, et al. Qualitative exploration of intentions, concerns and information needs of vaccine-hesitant adults initially prioritised to receive COVID-19 vaccines in Australia. Aust N Z J Public Health. 2022;46(1):16–24. doi:10.1111/1753-6405.13184.

- Kaufman J, Bagot KL, Hoq M, Leask J, Seale H, Biezen R, Sanci L, Manski-Nankervis J-A, Bell JS, Munro J, et al. Factors influencing Australian healthcare workers’ COVID-19 vaccine intentions across settings: a cross-sectional survey. Vaccines. 2022;10(1):3. doi:10.3390/vaccines10010003.

- World Health Organization. Data for action: achieving high uptake of COVID-19 vaccines. 2021 [accessed 2022 Jan 18]. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-2019-nCoV-vaccination-demand-planning-2021.1.

- World Health Organization. Understanding the behavioural and social drivers of vaccine uptake WHO position paper- May 2022. 2022 [accessed 2022 Oct 10]. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/who-wer9720-209-224.

- pencs. General practice and AMS. 2022 [accessed 2022 Oct 10]. https://www.pencs.com.au/general-practice/.

- Harris PA, Taylor R, Minor BL, Elliott V, Fernandez M, O’Neal L, McLeod L, Delacqua G, Delacqua F, Kirby J, et al. The REDCap consortium: building an international community of software platform partners. J Biomed Inform. 2019;95:103208. doi:10.1016/j.jbi.2019.103208.

- StataCorp. Stata statistical software: Release 15. StataCorp LPTX, USA: College Station; 2019.

- Enticott J, Gill JS, Bacon SL, Lavoie KL, Epstein DS, Dawadi S, Teede HJ, Boyle J, iCARE Study Team. Attitudes towards vaccines and intention to vaccinate against COVID-19: a cross-sectional analysis—implications for public health communications in Australia. BMJ Open. 2022;12(1):e057127. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2021-057127.

- Al-Rawashdeh S, Rababa M, Rababa M, Hamaideh S. Predictors of intention to get COVID-19 vaccine: a cross-sectional study. Nurs Forum. 2022;57(2):277–87. doi:10.1111/nuf.12676.

- Coe AB, Elliott MH, Gatewood SBS, Goode J-V, Moczygemba LR. Perceptions and predictors of intention to receive the COVID-19 vaccine. Res Social Adm Pharm. 2022;18(4):2593–99. doi:10.1016/j.sapharm.2021.04.023.

- Miraglia Del Giudice G, Napoli A, Corea F, Folcarelli L, Angelillo IF. Evaluating COVID-19 vaccine willingness and hesitancy among parents of children aged 5–11 years with chronic conditions in Italy. Vaccines. 2022;10(3):396. doi:10.3390/vaccines10030396.

- Chu H, Liu S. Integrating health behavior theories to predict American’s intention to receive a COVID-19 vaccine. Patient Educ Couns. 2021;104(8):1878–86. doi:10.1016/j.pec.2021.02.031.

- Eibensteiner F, Ritschl V, Nawaz FA, Fazel SS, Tsagkaris C, Kulnik ST, Crutzen R, Klager E, Völkl-Kernstock S, Schaden E, et al. People’s willingness to vaccinate against COVID-19 despite their safety concerns: Twitter poll analysis. J Med Internet Res. 2021;23(4):e28973. doi:10.2196/28973.

- Johnson KD, Akingbola O, Anderson J, Hart J, Chapple A, Woods C, Yeary K, McLean A. Combatting a “Twin-demic”: a quantitative assessment of COVID-19 and influenza vaccine hesitancy in primary care patients. Health Promot Perspect. 2021;11(2):179–85. doi:10.34172/hpp.2021.22.

- Troiano G, Nardi A. Vaccine hesitancy in the era of COVID-19. Public Health. 2021;194:245–51. doi:10.1016/j.puhe.2021.02.025.

- Rosiello DF, Anwar S, Yufika A, Adam RY, Ismaeil MI, Ismail AY, Dahman NBH, Hafsi M, Ferjani M, Sami FS, et al. Acceptance of COVID-19 vaccination at different hypothetical efficacy and safety levels in ten countries in Asia, Africa, and South America. Narra J. 2021;1(3):e55. doi:10.52225/narra.v1i3.55.

- Napolitano F, Miraglia Del Giudice G, Angelillo S, Fattore I, Licata F, Pelullo CP, Di Giuseppe, G. Hesitancy towards childhood vaccinations among parents of children with underlying chronic medical conditions in Italy. Vaccines. 2022;10(8):1254. doi:10.3390/vaccines10081254.

- Szilagyi PG, Thomas K, Shah MD, Vizueta N, Cui Y, Vangala S, Fox C, Kapteyn A. The role of trust in the likelihood of receiving a COVID-19 vaccine: results from a national survey. Prev Med. 2021;153:106727. doi:10.1016/j.ypmed.2021.106727.

- Lachlan H, Macleay A GP led COVID-19 respiratory clinic opens in Kempsey. 2020 [accessed 2022 Feb 21]. https://www.proquest.com/docview/2404092562?accountid=12372.

- Australian Government Department of Health. ATAGI statement on COVID-19 vaccination and a reported case of thrombosis: Commonwealth Government. Department of Health; 2021 [accessed 2022 Mar 10]. https://www.health.gov.au/news/atagi-statement-covid-19-vaccination-reported-case-of-thrombosis.

- Australian Government Department of Health. Is it true? Does the Vaxzevria (AstraZeneca) COVID-19 vaccine cause blood clots?. 2021 [accessed 2022 Mar 16]. https://www.health.gov.au/initiatives-and-programs/covid-19-vaccines/is-it-true/is-it-true-does-the-vaxzevria-astrazeneca-covid-19-vaccine-cause-blood-clots#: :text=There%20has%20been%20a%20link,every%20million%20after%20being%20vaccinated.

- Marshall M. The power of trusting relationships in general practice. BMJ. 2021;374:n1842. doi:10.1136/bmj.n1842.

- Biezen R, Grando D, Mazza D, Brijnath B. Why do we not want to recommend influenza vaccination to young children? A qualitative study of Australian parents and primary care providers. Vaccine. 2018;36(6):859–65. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2017.12.066.

- Birkhäuer J, Gaab J, Kossowsky J, Hasler S, Krummenacher P, Werner C, Gerger H, Nater UM. Trust in the health care professional and health outcome: a meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2017;12(2):e0170988. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0170988.

- Gabarda A, Butterworth SW. Using best practices to address COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy: the case for the motivational interviewing approach. Health Promot Pract. 2021;22(5):611–15. doi:10.1177/15248399211016463.

- Bianco A, Mascaro V, Zucco R, Pavia M. Parent perspectives on childhood vaccination: how to deal with vaccine hesitancy and refusal? Vaccine. 2019;37(7):984–90. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2018.12.062.

- Moore JE, Millar BC. Improving COVID-19 vaccine-related health literacy and vaccine uptake in patients: comparison on the readability of patient information leaflets of approved COVID-19 vaccines. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2021;46(6):1498–500. doi:10.1111/jcpt.13453.

- Mercadante AR, Law AV. Will they, or won’t they? Examining patients’ vaccine intention for flu and COVID-19 using the health belief model. Res Social Adm Pharm. 2021;17(9):1596–605. doi:10.1016/j.sapharm.2020.12.012.

- Mahimbo A, Ikram A, Heywood A COVID-19 vaccine uptake in CALD communities: support GPs better. MJA InSight+. 2021 [accessed 2022 Mar 18]. https://insightplus.mja.com.au/2021/34/covid-19-vaccine-uptake-in-cald-communities-support-gps-better/.

- Australian Government Department of Health. Culturally and linguistically diverse communities COVID-19 health advisory. 2022 [accessed 2022 Feb 7]. https://www.health.gov.au/committees-and-groups/culturally-and-linguistically-diverse-communities-covid-19-health-advisory-group.

- Therapeutic Goods Adminstration. AstraZeneca ChAdox1-S COVID-19 vaccine. 2021 [accessed 2022 Feb 7]. https://www.tga.gov.au/media-release/astrazeneca-chadox1-s-covid-19-vaccine.

- Australian Government Department of Health and Aged Care. Vaccination numbers and statistics. 2022 [accessed 2022 Aug 7]. https://www.health.gov.au/initiatives-and-programs/covid-19-vaccines/numbers-statistics#total-national-doses.

- Mao F. COVID: how Delta exposed Australian’s pandemic weakneses. BBC News. 2021 Jun [accessed. 2022 Jun 29]. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-australia-57647413.

- Berkhout A, Crawford N, Buttery J, McGuire R, Machingaifa F COVID-19 mandatory vaccination directions in Victoria. 2021 [accessed 2022 Mar 27]. https://mvec.mcri.edu.au/references/covid-19-mandatory-vaccination-directions-in-victoria/.

- WA.gov.au. COVID-19 coronavirus: mandatory COVID-19 vaccination information: government of Western Australia; 2022 [accessed. 2022 August 5]. https://www.wa.gov.au/government/covid-19-coronavirus/covid-19-coronavirus-mandatory-covid-19-vaccination-information.

- Northern Territory Government. Coronavirus (COVID-19) mandatory vaccinations. 2022 [accessed 2022 Mar 17]. https://coronavirus.nt.gov.au/business-and-work/mandatory-vaccinations.

- Choudhury SR Australia’s mixed messages on COVID vaccines sow confusion. CNBC; 2021 Jul 1. [accessed. 2022 Mar 17]. https://www.cnbc.com/2021/07/01/australias-mixed-messages-on-covid-vaccines-sow-confusion.html.

- Knaus C ‘Critical’ lack of COVID vaccine supply in Melbourne forcing GPs to turn people away. The Guardian; 2021 Jun 3 [accessed 2022 Mar 17]. https://www.theguardian.com/australia-news/2021/jun/03/critical-lack-of-covid-vaccine-supply-in-melbourne-forcing-gps-to-turn-people-away.

Appendix Appendix A.

COVID Vaccine Preparedness Survey - prioritised public

Are you a healthcare worker currently working in Victoria, Australia?

□ Yes –> re-direct to HCW survey “Thank you for answering this question. Please click here <HCW SURVEY LINK> to complete the survey for healthcare workers”

□ No

Do you live in Victoria, Australia?

□ Yes

□ No –> Ineligible “Thank you for your time. This survey is for adults living in Victoria.”

Are you:

□ Less than 18 years old –> Ineligible “Thank you for your time. This survey is for people 18 years and older.”

□ 18–69 years-old –> Go to q4

□ 70 years old or older

(If aged 18–69):

Do you have any of the following chronic or underlying health conditions? (tick all that apply)

□ Cardiovascular disease (e.g. Heart disease, history of heart attack or stroke)

□ Respiratory disease or chronic respiratory condition (e.g. severe asthma, COPD, emphysema, other lung disease)

□ Chronic neurological conditions (e.g. multiple sclerosis, spinal cord injuries, seizure disorders)

□ Cancer or history of cancer

□ Diabetes (type 1 or type 2)

□ Autoimmune disease (e.g. lupus, multiple sclerosis, rheumatoid arthritis, psoriasis, Crohn’s disease, inflammatory bowel disease)

□ Immunocompromising condition (e.g. HIV, cancer, transplantation, regular steroid use)

□ Chronic kidney disease

□ Chronic liver disease

□ Other, please specify ___

□ Prefer not to say –> Ineligible if aged 18-69 years-old “Thank you for your time. This survey is for people over 70 and people aged 18-69 with chronic or underlying health conditions.”

□ None of the above –> Ineligible if aged 18-69 years-old “Thank you for your time. This survey is for people over 70 and people aged 18-69 with chronic or underlying health conditions.”

(5) Have you ever been tested for COVID-19?

□ No

□ Yes

◯ Approximately how many times have you been tested? ____

◯ Have you ever received a positive COVID-19 test result?

∎ No

∎ Yes

(6) Has anyone in your household received a positive COVID-19 test result?

□ No

□ Yes

(7) How concerned are you about getting COVID-19?

□ Not at all concerned

□ A little concerned

□ Moderately concerned

□ Very concerned

(8) How much do you trust the new COVID-19 vaccines?

□ Not at all

□ A little

□ Moderately

□ Very much

(9) How important do you think getting a COVID-19 vaccine will be for your health?

◯ Not at all important

◯ A little important

◯ Moderately important

◯ Very important

(10) How much do you think getting a COVID-19 vaccine for yourself will protect other people in your community from COVID-19?

□ Not at all

□ A little

□ Moderately

□ Very much

(11) How safe do you think a COVID-19 vaccine will be for you?

□ Not at all safe

□ A little safe

□ Moderately safe

□ Very safe

(12) How concerned are you that a COVID-19 vaccine could cause you to have a serious reaction? Would you say …

□ Not at all concerned

□ A little concerned

□ Moderately concerned

□ Very concerned

(13) If a COVID-19 vaccine were recommended for you, would you get it?

□ No

□ Yes

□ Not sure

◯ If no or unsure, what are your reasons for your decision (tick all that apply):

◯ I don’t believe I’m at risk

◯ I am concerned about minor side effects

◯ I am concerned about serious reactions

◯ I am concerned that the vaccines haven’t been tested enough for safety

◯ I am concerned about the potential long-term effects of the vaccine

◯ I am concerned about safety in pregnancy

◯ I am concerned about safety whilst breastfeeding

◯ I am concerned about pain from the needle

◯ I have had a reaction to a vaccine in the past

◯ I am concerned about needing to take time off work

◯ I am concerned that the vaccine won’t work well enough

◯ Other

(14) How much do you want to get a COVID-19 vaccine? Would you say …

□ Not at all

□ A little

□ Moderately

□ Very much

(15) Do you think most of your close family and friends would want you to get a COVID-19 vaccine?

□ No

□ Yes

□ Not sure

(16) Do you think most adults you know will get a COVID-19 vaccine, if it is recommended to them?

□ No

□ Yes

□ Not sure

(17) Do you think that getting a COVID-19 vaccine will allow you to safely see your family and friends again?

□ No

□ Yes

□ Unsure

(18) How convenient do you think it will be for you to get a COVID-19 vaccine?

□ Not at all convenient

□ A little convenient

□ Moderately convenient

□ Very convenient

If not at all/a little/moderately convenient, what do you think will make it hard for you to get a COVID-19 vaccine? (tick all that apply):

◯ Knowing which vaccine priority group I am in (e.g. Phase 1a, Phase 1b etc)

◯ Knowing where to go to get the vaccine

◯ Organising a vaccine appointment at a time that suits me

◯ Travelling to a location where I can get a vaccine

◯ Waiting a long time at the location

◯ Taking time off work

◯ Managing carer or family responsibilities (e.g. childcare)

◯ Something else, please specify: _______

(19) If your employer requires you to get a COVID-19 vaccine, will this make you more likely to get it?

□ No

□ Yes

□ Not sure

□ I am not currently working

(20) Where would you prefer to get a COVID-19 vaccine?

□ Hospital

□ General practice

□ Pharmacy

□ Community center, meeting hall, or local shop

□ Large public space (e.g. conference centre, stadium)

□ Council clinic

□ My usual workplace

□ Place of worship

□ Residential aged care or disability care facility

□ Somewhere else, please specify: ________

□ n/a

(21) Which of the following factors might influence your decision about getting the COVID-19 vaccine? (tick all that apply)

□ brand of vaccine offered

If yes, which brand would you prefer?

◯ Pfizer

◯ Oxford/AstraZeneca

◯ Novavax

◯ Other COVID-19 vaccines purchased through COVAX facility, such as Moderna

◯ If you can’t get your brand of choice, would you be willing to get another brand?

∎ Yes

∎ No

∎ Not sure

□ country where the vaccine was manufactured

If yes: which country would you prefer?

◯ Made in Australia

◯ Made in the USA

◯ Made in Europe/UK

◯ Made in Russia

◯ Made in another country?____

□ information about the vaccine approval process

□ the reported efficacy of the vaccine from clinical trials

□ the reported safety of the vaccine from clinical trials

□ seeing how people who have been vaccinated overseas have reacted to the vaccine

□ if the vaccine is available at my workplace

□ if the vaccine is required to travel overseas

□ other _____

For each of the following topics on COVD-19 vaccines, do you feel you have enough information?

(27) How do you prefer to receive COVID-19 vaccine information? (tick your TOP TWO)

□ Television

◯ Community/public

◯ Commercial

□ Radio

◯ Community/public

◯ Commercial

□ Government website or sources

□ Other website

◯ Specify ____

□ Newspapers (online and print)

□ Academic journals

□ Social media

◯ Facebook

◯ Twitter

◯ WhatsApp

◯ WeChat

◯ Other: ____

Hotline to ring for information

Discussion with my healthcare provider

Family or friends

Other:____

(28) Who do you trust to provide you with information about the COVID-19 vaccines? (tick your TOP TWO)

□ Scientists or researchers

□ Medical professionals

□ My primary healthcare provider

□ Commonwealth Government representative

□ State Government representative

□ Celebrities or online influencers

□ Community leaders

□ Religious leaders

□ Family or friends

□ Other:____

(29) Who would you prefer to inform you about the timing and location of your vaccination? (tick your TOP TWO)

□ Commonwealth Government representative

□ State Government representative

□ My local council

□ My primary healthcare provider

□ My employer

□ My union or professional body

□ Community health worker

□ Local hospital infectious disease or immunization department

(30) Do you have any comments, concerns or suggestions that you would like to share? (FREE TEXT)

Demographics

(31) What is your age group?

□ 18 - 29

□ 30 - 39

□ 40 – 49

□ 50 - 59

□ 60 - 69

□ 70 – 79

□ 80+

(32) What is your gender?

□ Woman

□ Man

□ Non-binary

□ Prefer not to say

(33) What is your country of birth? <drop down menu>

(34) Do you speak a language other than English at home most of the time?

□ No

□ Yes

◯ If yes, what language? _____________________________________

(35) Are you of Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander origin?

□ No

□ Yes

□ Prefer not to say

(36) What is the postcode where you live? ____

(37) What is your highest qualification?

□ High school

□ Trade certificate/diploma

□ Undergraduate degree

□ Postgraduate degree

□ None of the above

(38) Which of the following best describes your current employment?

□ Full-time

◯ Casual

◯ Fixed term contract

◯ Continuing position

◯ Self-employed/contractor

□ Part-time

◯ Casual

◯ Fixed term contract

◯ Continuing position

◯ Self-employed/contractor

□ Retired

□ Not working and not seeking work (e.g. home caring duties)

□ Unemployed and seeking work

□ Other (please specify) _______________________________

Appendix B.

Prioritized public by age group.

Appendix C.

Prioritized public by culturally and linguistically diverse (CALD) status