ABSTRACT

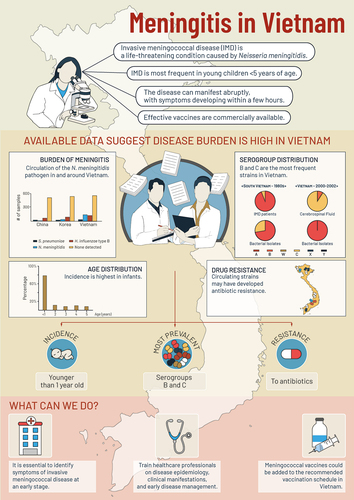

Invasive meningococcal disease (IMD), caused by Neisseria meningitidis, is life-threatening with a high case fatality rate (CFR) and severe sequelae. We compiled and critically discussed the evidence on IMD epidemiology, antibiotic resistance and disease management in Vietnam, focusing on children. PubMed, Embase and gray literature searches for English, Vietnamese and French publications, with no date restrictions, retrieved 11 eligible studies. IMD incidence rate (/100,000 population) was 7.4 [95% confidence interval 3.6–15.3] in children under 5 years of age; driven by high rates in infants (e.g. 29.1 [8.0–106.0] in 7–11 month-olds). Serogroup B IMD was predominant. Neisseria meningitidis strains may have developed resistance to streptomycin, sulfonamides, ciprofloxacin, and possibly ceftriaxone. There was a lack of current data on diagnosis and treatment of IMD, which remain challenging. Healthcare professionals should be trained to rapidly recognize and treat IMD. Preventive measures, such as routine vaccination, could help address the medical need.

Introduction

Invasive meningococcal disease (IMD), caused by N. meningitidis bacteria, is an aggressive disease requiring urgent medical attention, and is responsible for a substantial clinical and economic burden.Citation1 IMD causes death in 4–20% of cases within two days of symptom onset.Citation2–4 About 10–20% of those who survive the disease suffer severe, long-term medical sequelae, such as limb amputations, hearing loss, and learning, emotional and behavioral difficulties.Citation5 There is a narrow time window for clinical diagnosis and medical intervention between appearance of the first symptoms and severe disease or death.Citation2 By the time of hospital admission, 7–15% of children with IMD will be unconscious.Citation2

The highest incidence of IMD occurs in the youngest population of infants (aged under 12 months) and children younger than five years.Citation6 Six meningococcal serogroups (A, B, C, W, X and Y), each with a distinct type of polysaccharide capsule, cause most IMD cases worldwide.Citation7 The epidemiological profile of the disease is unpredictable, leading to isolated sporadic cases or to long-lasting outbreaks.Citation1 The temporal dynamics of the disease indicate that it is seasonal, with winter peaks.Citation8 The prevalence of meningococcal serogroups varies with age and geographical region.Citation6 In the same region, serogroup predominance may change from one year to another, as it can be affected by local immunization programs, behavioral and environmental factors, as well as international travel.Citation9

In Vietnam, most cases of IMD are diagnosed and treated in specialty care hospitals. Based on data from the available surveillance system,Citation10 the incidence rate in 2018 was 0.02 per 100,000 population.Citation11 Studies have estimated higher incidence rates (/100,000 population) in the military population, ranging from 0.22–2.67 between 2018 and 2021,Citation12 and in children aged <5 years (7.4) and infants reundent <1 month (36.2).Citation13 There is scarce evidence about circulating strains and their antibiotic susceptibilities, and about the diagnosis and clinical management of IMD, especially for severe cases in the Vietnamese pediatric population.

This review of the available evidence aimed to compile and critically discuss existing information in relation to IMD epidemiology and management in Vietnam. We sought to synthesize evidence pertaining to the pediatric population and, ultimately, to increase awareness of the disease and its management among healthcare professionals (HCPs) ().

Materials and methods

This structured literature review was guided by the following research questions, with a focus on disease caused by N. meningitidis: (a) what is the current epidemiology (e.g., incidence, serogroups in cases and carriers, case fatality rate [CFR]) of IMD in Vietnam? (b) what evidence is there of antibiotic resistance to IMD treatments in the Vietnamese population? and (c) how is IMD managed (e.g., diagnosis, symptoms, laboratory findings, treatments, duration of hospitalization) in the Vietnamese population, especially in children?

Search strategy

A literature search was performed in Embase and Medline (via PubMed) using a combination of Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) and keywords to describe meningococcal disease with terms for Vietnam. The search was limited to human studies, with no language restrictions, limitations on date, publication type or publication status, or population age applied (Supplementary Table A1). A search of the gray literature was also performed; with conference publications, hospital journals, and websites of the Ministries of Health (MoH), medical associations and medical institutes also reviewed.

Study selection process and data extraction

Two reviewers (TP, MNHL) conducted the database searches independently and assessed the eligibility of studies identified. If there was disagreement regarding study eligibility, an independent reviewer (GM) was consulted to reach a final mutual agreement. All studies that addressed any of the research questions were included in this review. Studies that were excluded, with reasons for exclusion, are in Supplementary Table A2. Data extraction was done in Microsoft Excel using pre-designed tables to ensure consistent extraction by the two reviewers. Extracted data included study characteristics (first author, journal name, and year of publication), time period of the study, study design, study population, objectives, methodology and the main findings that addressed the research questions above. Findings from the gray literature were handled in the same way.

Results

The literature search retrieved 22 publications, of which 11 studies were eligible for inclusion in the review. Pediatric populations were included in five studies.Citation13–17 Seven studiesCitation12–16,Citation18,Citation19 reported epidemiologic outcomes () and information was identified on annual meningococcal meningitis case numbers from the Vietnam Medical Association.Citation20 Six studiesCitation12,Citation16−Citation19,Citation21 reported antibiotic susceptibility outcomes (). Disease management in adults was reported in one studyCitation12 () with additional data from the Vietnam Medical Association,Citation20 while information from a pediatric hospital case studyCitation22 or expertsCitation23 reported on childhood management issues.

Table 1. Studies reporting epidemiological outcomes.

Table 2. Studies reporting antibiotic resistance outcomes.

Table 3. Studies reporting disease manifestation and clinical work-up.

Epidemiology of IMD

Epidemiologic outcomes () were reported in three prospective surveillance studiesCitation12–14 and a retrospective hospital database analysis during an epidemic in 1977.Citation15 Additional data on IMD serogroups were reported in three retrospective analyses of isolates from cases and/or carriers.Citation16,Citation18,Citation19

The most recent data on the incidence of IMD were from a prospective surveillance study in adults across all military hospitals in Vietnam from 2014 to 2021. Overall, 69 IMD cases due to N. meningitidis were reported, with annual incidence rates (/100,000 population) varying each year, from 0.22 in 2021 to 3.33 in 2016. The mean incidence across the study time period was 1.92, with a CFR of 8.7%. Serogroup B IMD was predominant in each year, ranging from 86.7% in 2016 to 100% (in 2015, 2017, 2019–2021).Citation12 The wearing of face masks and hygiene guidelines imposed on military recruits as part of the COVID-19 pandemic control measures may have contributed to the reduced IMD incidence observed in 2020–2021, and the authors suggest that such measures might also be helpful as a preventive measure against IMD.Citation12

In children, IMD incidence was reported in 2000–2002 from a multinational prospective surveillance study (including 10 culture-confirmed and 110 PCR-confirmed cases in Vietnam)Citation13 and from a prospective surveillance study in Hanoi (including 10 IMD cases due to N. meningitidis).Citation14 The first study reported age-dependent incidence rates (/100,000 [95% confidence interval]) of 7.4 [3.6–15.3] in children <5 years; driven by high rates in infants (e.g., 29.1 [8.0–106.0] in 7–11 month-olds) and younger children aged 1–2 years (i.e., 13.7 [3.8–50.1]) compared with older children aged 2–5 years (2.4 [0.5–10.2]). In this study, among 32 specimens tested, 20 CSF (cerebrospinal fluid) specimens identified serogroup C IMD, while 10 bacterial isolates and 2 CSF isolates identified serogroup B IMD.Citation13 Among the 10 children from the second study in Hanoi, N. meningitidis IMD incidence was 2.6 [0.8–8.5] in children <5 years with a peak of 21.8 [5.0–94.4] in infants aged 7–11 months.Citation14

An older study of IMD incidence in adults and children in southern Vietnam reported that 1,079 IMD cases occurred between 1966 and 1974. The incidence rates were over 5 since 1976, and increased during the serogroup C epidemic (1977–1979) to over 20 in 1977, with a CFR of 27.4–34.7% during the epidemic.Citation15

According to the Vietnam Medical Association,Citation20 Vietnam has, on average, 650 cases of bacterial meningitis per year, with IMD accounting for 14% of cases. Additionally, they estimate that if treatment is delayed, CFRs can reach 60–70% for fulminant IMD and 30–40% for purulent meningitis.Citation20

From the three retrospective studies providing data on serogroups, the majority of IMD cases tested were serogroup B IMD (100% of five military population cases in 2008–2017,Citation18 100% of 11 hospitalized cases in 1987–1996Citation16 and 94% of 50 cases in South Vietnam in 1980–2019 vs. 6% serogroup C cases).Citation19 Serogroup B was also predominant among carriers, (i.e., 73.9% of 23 military population carriers tested vs. 26.1% with serogroup C18, and 56% of 59 carrier isolates tested vs. 21% for serogroup C19).

Antibiotic resistance

Antibiotic susceptibility data () were reported in one prospective surveillance study,Citation12 three retrospective isolate analysis studies,Citation16,Citation18,Citation19 a retrospective case studyCitation21 and a randomized controlled antibiotic trial.Citation17

From studies in a military population; there were two IMD cases (from 8 isolates tested) with ceftriaxone resistance, the first line treatment for this population;Citation12 and two IMD cases (from 5 cases tested) with chloramphenicol resistance and reduced susceptibility to ampicillin.Citation18 Another drug-resistant isolate from a soldier hospitalized in 2014 with signs of sepsis and meningitis also had considerable resistance to chloramphenicol (minimal inhibitory concentration [MIC] 256 µg/ml) and reduced susceptibility to ampicillin and rifampicin.Citation21

In other populations, high levels of chloramphenicol resistance were also found in 11 N. meningitidis isolates from hospitalized IMD cases (1987–1996).Citation16 Resistance to ciprofloxacin and intermediate resistance to penicillin was found in IMD isolates from South Vietnam between 1980 and 2019.Citation19 In a randomized controlled trial of ceftriaxone (2001–2006) in 164 infants in Vietnam with purulent bacterial meningitis, all were susceptible to ceftriaxone.Citation17

Clinical management of patients with IMD

Recent data on the presentation and current management of IMD () was extracted from a prospective surveillance study in adults across military hospitals from 2014–2021.Citation12 One case studyCitation22 and pediatric hospital expertsCitation23 reported information on current management of IMD in children.

Among the military population, 69 IMD cases were hospitalized during 2014–2021, of which 43.5% presented with meningitis, 37.7% with meningococcemia and 18.8% with septicemia. The most common symptoms at admission were neck stiffness (88.4%), altered mental status (72.5%), petechial rash (50.7%), shock (29%), coma (18.8%), seizure (13%) and incontinence (11.6%).Citation12 According to the Vietnam Medical Association, a necrotic rash on the skin can be mistaken for streptococcal illness, and early detection of IMD is often difficult due to the nonspecific initial symptoms, which can rapidly escalate.Citation20

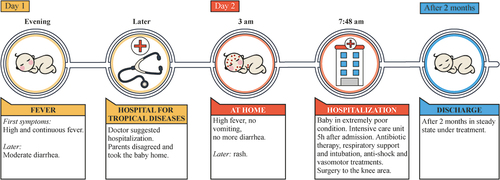

The mean time from the onset of the initial symptoms to hospitalization was 1.9 days (standard deviation, 0.9) in meningitis cases, 2.2 days (0.8) in meningococcemia cases, and 1.8 days (0.8) in septicemia cases.Citation12 In children, the rapid disease progression seen with IMD is also challenging, according to experts from the National Children’s Hospital and the Pasteur Da Lat Medical Center, with average time between onset of symptoms and hospital admission reported to be as short as 19 hours.Citation23 A case report from a pediatric hospitalCitation22 showed IMD can progress within one hour from the onset of symptoms, with continuously worsening and no signs of recovery, despite intensive interventions ().

Before hospitalization, a third of patients had received a third-generation cephalosporin, and 4.3% had received carbapenem. Hospital treatment involved central catheter insertion (33.3%), antibiotic therapy with third-generation cephalosporin (30.4%), mechanical ventilation (13%), continuous renal replacement therapy (8.7%), plasma transfusion (5.8%), carbapenem (4.3%), platelet transfusion (2.9%), amputation (2.9%) and an arterial line (1.4%).Citation12 According to the authors, a sharp increase in cases in 2016 was swiftly addressed by a guideline for the management of suspected IMD from the Department of Military Medicine, which resulted in a subsequent decrease in case numbers.Citation12

From the gray literature, a description of IMD outcomes in children was reported from pediatric hospital experts.Citation23 Although meningococcal infection is rare in children, N. meningitidis can cause serious illness ranging from sepsis, to meningitis, and to fulminant meningococcal septicemia, with a mortality rate of 30–40%. In addition, severe complications, such as brain damage, weakness, necrosis of the skin, and limb amputation, result in both a physical and a mental health challenge for patients, their families and society.Citation23

The Ministry of Health Department of Preventive Medicine issued the following recommendations to help prevent the spread of encephalitis and meningococcal disease in the community; (1) increased personal hygiene (2) increased living space hygiene, (3) a rapid visit to a medical faculty if symptoms of headache, fever, nausea, vomiting or stiff neck occur, and (4) active childhood vaccination against encephalitis and meningococcal disease.Citation20,Citation24 Meningococcal vaccination is not part of the national immunization program in Vietnam. The Central Children’s Hospital in Hanoi, for example, only recommends vaccination for high-risk individuals (close contacts of a case, immunocompromised individuals, travelers).Citation25 Two vaccines are available; a bivalent polysaccharide meningococcal vaccine against serogroups B and C is recommended in two doses, at least 6–8 weeks apart, beginning at six months of age;Citation23 and a conjugate vaccine against serogroups A, C, W and Y, recommended in two doses, three months apart, for children aged 9–23 months, or a single dose for individuals aged 2–55 years.Citation23,Citation26,Citation27

Discussion

This review of the Vietnamese scientific literature was on meningococcal disease epidemiology, antibiotic resistance and clinical management, with an emphasis on children. Recent evidence on incidence rates was available for adults from military hospitals; incidence ranged from 0.22 to 3.33/100,000 population from 2016 to 2021, serogroup B was predominant, and the overall CFR was 8.7%. Serogroup B was also found to be predominant in both IMD cases and carriers in other (nonmilitary) populations. During the serogroup C epidemic in 1977–79, incidence rates were over 20, with a CFR peak of nearly 35%. In children, data from 2000–2002 were identified from a large study in Vietnam, which confirmed higher incidence rates are observed in infants (e.g., 29.1 in 7–11 month-olds), and in children under five (7.4). Limited data were identified on antibiotic resistance, showing that N. meningitidis strains circulating in Vietnam may have developed resistance to chloramphenicol, streptomycin, sulfonamides, ciprofloxacin and possibly ceftriaxone, with reduced susceptibility reported to ampicillin, penicillin G and rifampicin. Limited data were found on IMD clinical management (one study in military hospitals), especially in children (one case study). IMD can present as meningitis, meningococcemia or septicemia. Data show a range of potential early symptoms, and a rapid progression to severe illness or death, the need for intensive hospital treatment, the need for antibiotic treatment, and a risk of severe complications and sequelae. Due to the difficulties in diagnosing and managing IMD, prevention measures, including vaccination, are recommended to reduce the spread of IMD, although IMD vaccines are not currently part of the national immunization program.

The epidemiology data from Vietnam show an age-related pattern with highest incidence rates in children and infants and a predominance of serogroup B, which is in line with data from other countries throughout Southeast Asia and Asia-Pacific regions.Citation28,Citation29 High CFRs were reported in children in some of these countries (e.g., over 50% in the Philippines, around 40% in Thailand), however, no recent Vietnamese studies report incidence rates and CFR by age group. Data from South Korea also report a higher incidence in army populations, of around 2.2/100,000 per year, compared to the national average rates.Citation28

Since the late 1970s, there has been an increase and spread of antibiotic-resistant bacteria as a result of the widespread use of antibiotics.Citation30 Chloramphenicol-resistant N. meningitidis has been identified in isolates from Vietnam since 1987.Citation16 The same type of antibiotic-resistant isolates was detected in 8 of the 18 N. meningitidis isolates collected from Cambodia, Laos and Thailand between 2007 and 2018.Citation31 Available data from Vietnam indicate a decrease in penicillin and ciprofloxacin sensitivity,Citation12,Citation16,Citation19,Citation21 which has been taken to imply an increase in antibiotic use in primary care. Susceptibility testing should be performed while the individual is being treated with first-line antimicrobials, which may be switched once susceptibility results becomes available, to avoid treatment delays.Citation32 Penicillin resistance among N. meningitidis isolates has been seen elsewhere as well, whereas ceftriaxone- and ciprofloxacin-resistant strains are rare.Citation32,Citation33 Antibiotic resistance is a global problem that jeopardizes progress in the fight against infectious diseases.Citation34 As such, special attention and actions to decrease antibiotic use in the community are warranted, which include increased vaccination.Citation35,Citation36

While IMD remains difficult to diagnose and manage, evidence on the current clinical diagnosis and management of IMD, especially in children, was lacking in Vietnam. Timely, appropriate antibiotic treatment for cases, as well as prophylactic treatment for their close contacts, is essential.Citation37–40 However, recognizing and diagnosing IMD is exceedingly challenging, even more so for community physicians who are only likely to have seen a few cases.Citation2 Therefore, it is essential to train HCPs on IMD morbidity and early management of this disease, as well as on the proper collection and handling of specimens for laboratory testing. Guidelines and studies from other countries can help to inform clinicians about IMD presentation and clinical management options, and are summarized below.

IMD presentation

Meningitis and sepsis are the most prevalent manifestations of IMD, and in some cases both occur.Citation41 In children, IMD can manifest abruptly, with symptoms developing within a few hours. While it is vital to notice symptoms early on when a child presents to primary care,Citation42,Citation43 this remains challenging, with only a few children presenting as acutely ill or with classic meningitis symptoms.Citation42,Citation44 Nonspecific symptoms such as headache, fever, loss of appetite, nausea, vomiting, sore throat and coryza are among the most frequently encountered initial disease presentations, lasting for approximately 4 hours.Citation2 Not every child with a fever, headache or coryza will develop IMD, but it cannot be ruled out in the first 6 hours.Citation2,Citation43 Classic IMD-specific symptoms such as rash, meningitis and altered consciousness are typically recorded later in the illness, during the pre-admission period.Citation2 Parents should monitor their child’s symptoms and consult their HCPs if the child’s condition deteriorates.Citation43 Repeated clinical examination should be scheduled for the same day.Citation2 Subsequent signs of sepsis e.g., leg pain, cold limbs or abnormalities in skin coloring, develop within 7–12 hours, and more rapidly in infants than in older children.Citation2 These are followed by other IMD-specific signs and symptoms such as photophobia, neck stiffness, hemorrhagic rash, bulging fontanel (in infants), and lastly, loss of consciousness, delirium, or seizures.Citation2 Hemorrhagic rash (purpura) is not always present.Citation2 Younger children can present with more atypical and subtle symptoms than older patients.Citation45 While the temporal course of symptoms varies by age, the sequence of symptoms from fever to sepsis and subsequently to specific symptoms (hemorrhagic rash, decreased consciousness, meningism) is consistent.Citation2

IMD diagnosis and therapeutic management

To establish a diagnosis of IMD, the initial clinical assessment should be followed by laboratory analyses of CSF or blood samples collected as soon as possible,Citation37,Citation46,Citation47 but also samples of synovial, pleural, or pericardial fluid, or from skin lesions.Citation46 The presence of N. meningitidis bacteria is confirmed if the sample is positive for bacterial culture. However, the culture diagnosis method can be compromised if antibiotics have been administered prior to sampling, or if samples have not been handled correctly.Citation48 The most recently developed quantitative polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assays do not suffer the same limitationsCitation48 and could complement culture diagnosis; however, cost constraints may prohibit wider use of this method.Citation46

Children presenting with ongoing shock should be admitted to the intensive care unit, probably ventilated, and treatment with antibiotic therapy and intravenous resuscitation fluid administration should commence immediately.Citation22,Citation48 The antibiotics of choice are ceftriaxone and cefotaximeCitation22 or chloramphenicol in patients with severe allergy to penicillin or cephalosporin.Citation45,Citation48,Citation49 Treatment duration is typically 5 to 7 days.Citation22,Citation48 Patients who are in shock should receive appropriate vasopressors; dexamethasone has not been shown to be beneficial in meningococcal meningitis. Deep tissue damage or necrosis may require surgery or amputation.Citation22,Citation48

Prevention of IMD

The two vaccines available in Vietnam are the meningococcal serogroup A, C, W and Y vaccine (MenACWY) and the BC meningococcal polysaccharide vaccines.Citation50 BC vaccine is indicated for ages 6 months to 45 years of age and is an outer membrane vesicle (OMV) vaccine that cannot offer full protection.Citation51

Meningococcal vaccination is offered mainly to high-risk groups and travelers. Vaccination for children is rarely considered, despite the high annual incidence in infantsCitation14 and risk of detrimental medical sequelae. While Vietnam has a history of unpredictable meningococcal outbreaks,Citation15,Citation52 prophylactic vaccinations have been overlooked in the country’s healthcare system. Emergency vaccination is used to tackle an ongoing epidemic but it is both logistically and financially costly, and preventable deaths may occur while awaiting the onset of vaccine-induced immunity.Citation53

Preventive meningococcal immunization has reduced meningococcal disease incidence in every region where it has been adopted. The introduction of routine immunization programs with serogroup C vaccination resulted in substantial decreases in cases, for example, in England, disease incidence decreased by 81% from 1999 to 2001 with a further decrease observed in non-vaccinated adults as well, attributed to herd immunity.Citation54 A similar decrease in cases in all age groups was also observed in the Netherlands and the United States with routine serogroup C vaccination.Citation6

Strengths and limitations

The strengths of this literature review are the methodology used to conduct the search and the broad eligibility criteria. However, few studies were identified in the general population, and those included often had small sample sizes, unspecified origins of samples and discrepancies in laboratory assessments. In Vietnam, research into IMD remains scarce. Most retrospective laboratory analyses include small numbers of CSF or blood samples acquired from hospitalized patients over extended periods of time. Although the search strategy to identify reports on epidemiology and management of IMD in Vietnam was broad and inclusive, some valuable sources of information may have been overlooked. The different settings of the retrieved studies render interpretation difficult, thus the results should be interpreted with due caution. The conclusions drawn here are based on the particular context of Vietnam and may not be generalizable to other locations, especially with different IMD epidemiology or disease management. More prospective studies are needed, as well as evidence from the general population and in children, who have the highest burden of disease, to collect age-specific data on epidemiology and disease presentation and management.

Conclusions

IMD has a high burden of disease, with risks of long-term sequelae and mortality and high incidence rates, especially among infants and young children. Despite the history of epidemics and the regular occurrence of sporadic cases, IMD epidemiology and clinical management remain poorly understood in Vietnam.

The available evidence shows that meningococcal serogroup B predominates in Vietnam. A serogroup B-specific vaccine (MenB) is available and efficacious in infants,Citation1,Citation55,Citation56 and could be included in the vaccination program in Vietnam with MenACWY vaccination for high-risk groups. Currently, non-vulnerable populations can only obtain these vaccines through the private sector, although routine immunization is the most effective means of controlling IMD.Citation1,Citation53

Authors’ contributions

All authors participated in the conception, data collection, implementation, analysis, or interpretation of the study, and the development of the present manuscript. All authors had full access to the data and gave final approval before submission

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (169.4 KB)Acknowledgment

The authors thank the Business & Decision Life Sciences platform for editorial assistance and manuscript coordination, on behalf of GSK. Athanasia Benekou provided writing assistance.

Disclosure statement

Gaurav Mathur, Thatiana Pinto, and Minh Hoan Le Nguyen are employees of GSK, and declare no other financial and non-financial relationships or activities. Phung Nguyen The Nguyen and Nguyen Thanh Hung declare no financial and non-financial relationships or activities and no conflicts of interest.

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed on the publisher’s website at https://doi.org/10.1080/21645515.2023.2172922

Additional information

Funding

References

- Martinón-Torres F. Deciphering the burden of meningococcal disease: conventional and under-recognized elements. J Adolesc Health. 2016;59:S12–9. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2016.03.041.

- Thompson MJ, Ninis N, Perera R, Mayon-White R, Phillips C, Bailey L, Harnden A, Mant D, Levin M. Clinical recognition of meningococcal disease in children and adolescents. Lancet. 2006;367:397–403. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(06)67932-4.

- Wang B, Santoreneos R, Giles L, Haji Ali Afzali H, Marshall H. Case fatality rates of invasive meningococcal disease by serogroup and age: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Vaccine. 2019;37:2768–82. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2019.04.020.

- World Health Organization (WHO). Meningococcal Meningitis; 2022 [accessed 2022 February 7]. https://www.who.int/teams/health-product-policy-and-standards/standards-and-specifications/vaccine-standardization/meningococcal-meningitis#:~:text=meningitidis%20is%20one%20of%20the,particularly%20in%20sub%2DSaharan%20Africa.

- Olbrich KJ, Müller D, Schumacher S, Beck E, Meszaros K, Koerber F. Systematic review of invasive meningococcal disease: sequelae and quality of life impact on patients and their caregivers. Infect Dis Ther. 2018;7:421–38. doi:10.1007/s40121-018-0213-2.

- Pelton SI. The global evolution of meningococcal epidemiology following the introduction of meningococcal vaccines. J Adolesc Health. 2016;59:S3–11. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2016.04.012.

- Hollingshead S, Tang CM. An overview of Neisseria meningitidis. Methods Mol Biol. 2019;1969:1–16.

- Paireau J, Chen A, Broutin H, Grenfell B, Basta NE. Seasonal dynamics of bacterial meningitis: a time-series analysis. Lancet Glob Health. 2016;4:e370–7. doi:10.1016/S2214-109X(16)30064-X.

- Parikh SR, Campbell H, Bettinger JA, Harrison LH, Marshall HS, Martinon-Torres F, Safadi MA, Shao Z, Zhu B, von Gottberg A, et al. The everchanging epidemiology of meningococcal disease worldwide and the potential for prevention through vaccination. J Infect. 2020;81:483–98. doi:10.1016/j.jinf.2020.05.079.

- Ministry of Health. Decision N 975/QĐ-BYT of Ministry of Health on 29 March 2012 [in Vietnamese]; 2012 [accessed 2022 January 7]. http://www.bvmatbinhdinh.vn/pages/2010/documents/2012/boyte/QD.975.2012.BYT.PDF

- Ministry of Health. Vietnam health statistics yearbook [in Vietnamese]; 2018 [accessed 2022 January 7]. https://moh.gov.vn/documents/176127/0/NGTK+2018+final_2018.pdf/29980c9e-d21d-41dc-889a-fb0e005c2ce9

- Van CP, Nguyen TT, Bui ST, Nguyen TV, Tran HTT, Pham DT, Trieu LP, Nguyen MD. Invasive meningococcal disease remains a health threat in Vietnam People’s Army. Infect Drug Resist. 2021;14:5261–69. doi:10.2147/IDR.S339110.

- Kim SA, Kim DW, Dong BQ, Kim JS, Anh DD, Kilgore PE. An expanded age range for meningococcal meningitis: molecular diagnostic evidence from population-based surveillance in Asia. BMC Infect Dis. 2012;12:310. doi:10.1186/1471-2334-12-310.

- Anh DD, Kilgore PE, Kennedy WA, Nyambat B, Long HT, Jodar L, Clemens JD, Ward JI. Haemophilus influenzae type B meningitis among children in Hanoi, Vietnam: epidemiologic patterns and estimates of H. Influenzae type B disease burden. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2006;74:509–15. doi:10.4269/ajtmh.2006.74.509.

- Oberti J, Hoi NT, Caravano R, Tan CM, Roux J. An epidemic of meningococcal infection in Vietnam (southern provinces). Bull World Health Organ. 1981;59:585–90.

- Galimand M, Gerbaud G, Guibourdenche M, Riou JY, Courvalin P. High-level chloramphenicol resistance in Neisseria meningitidis. N Engl J Med. 1998;339:868–74. doi:10.1056/NEJM199809243391302.

- Molyneux E, Nizami SQ, Saha S, Huu KT, Azam M, Bhutta ZA, Zaki R, Weber MW, Qazi SA, Csf SG. 5 versus 10 days of treatment with ceftriaxone for bacterial meningitis in children: a double-blind randomised equivalence study. Lancet. 2011;377:1837–45. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60580-1.

- Le TT, Tran TX, Trieu LP, Austin CM, Nguyen HM, Quyen DV. Genotypic characterization and genome comparison reveal insights into potential vaccine coverage and genealogy of Neisseria meningitidis in military camps in Vietnam. PeerJ. 2020;8:e9502. doi:10.7717/peerj.9502.

- Phan T, Ho N, Vo D, Pham H, Ho T, Nguyen H, Nguyen TV. Characterization of Neisseria meningitidis in Vietnam from 1980s-2019. Int J Infect Dis. 2020;101:147. doi:10.1016/j.ijid.2020.09.399.

- Vietnam Medical Association. Four recommendations to prevent meningococcal disease [in Vietnamese]; 2015 [accessed 2022 February 13]. http://tonghoiyhoc.vn/4-khuyen-cao-phong-chong-benh-viem-mang-nao-do-mo-cau.htm

- Tran TX, Le TT, Trieu LP, Austin CM, Van Quyen D, Nguyen HM. Whole-genome sequencing and characterization of an antibiotic resistant Neisseria meningitidis B isolate from a military unit in Vietnam. Ann Clin Microbiol Antimicrob. 2019;18:16. doi:10.1186/s12941-019-0315-z.

- Phung NTN. A case report of meningococcal infection in Children. In: Tien Giang Hospital Medicine Conference, Vietnam, 2021.

- VNExpress. Meningococcal disease is a ‘death disease’ [in Vietnamese]; 2021 [accessed 2022 February 13]. https://vnexpress.net/viem-mang-nao-mo-cau-la-benh-tu-4263456.html

- National Hospital for Tropical Diseases. Recommendations for prevention of meningitis infection [in Vietnamese]; 2016 [accessed 2022 February 13]. http://www.benhnhietdoi.vn/tin-tuc/chi-tiet/khuyen-cao-phong-benh-viem-nao-mang-nao-do-nao-mo-cau/281

- Anh Tuan H. Meningococcal infections - how to recognize and prevent [in Vietnamese]; 2016 [accessed 2022 February 13]. https://benhviennhitrunguong.gov.vn/benh-nhiem-khuan-do-nao-mo-cau-cach-nhan-biet-va-du-phong.html

- Hanh Phuc Hospital. Meningococcal disease: causes, symptoms and prevention. Hanh Phuc International Hospital [in Vietnamese]. 2021 [accessed 2022 February 13]. https://www.hanhphuchospital.com/benh-do-nao-mo-cau-khuan-nguyen-nhan-trieu-chung-va-cach-phong-ngua/

- Pasteur Da Lat Medical Center. Menactra – vaccine against Meningococcal disease ACYW [in Vietnamese]; 2021 [accessed 2022 February 13]. https://ykhoapasteurdalat.vn/menactra-vac-xin-phong-benh-viem-nao-mo-cau-a-c-y-w/

- Aye AMM, Bai X, Borrow R, Bory S, Carlos J, Caugant DA, Chiou CS, Dai VTT, Dinleyici EC, Ghimire P, et al. Meningococcal disease surveillance in the Asia–Pacific region (2020): the global meningococcal initiative. J Infect. 2020;81:698–711. doi:10.1016/j.jinf.2020.07.025.

- Marshall HS. Meningococcal surveillance in Southeast Asia and the Pacific. Microbiol Australia. 2021;42:178–81. doi:10.1071/MA21050.

- Finland M. Emergence of antibiotic resistance in hospitals, 1935–1975. Rev Infect Dis. 1979;1:4–22. doi:10.1093/clinids/1.1.4.

- Batty EM, Cusack TP, Thaipadungpanit J, Watthanaworawit W, Carrara V, Sihalath S, Hopkins J, Soeng S, Ling C, Turner P, et al. The spread of chloramphenicol-resistant Neisseria meningitidis in Southeast Asia. Int J Infect Dis. 2020;95:198–203. doi:10.1016/j.ijid.2020.03.081.

- Kuehn BM. Emerging drug-resistant meningitis detected in the US. JAMA. 2020;324:540. doi:10.1001/jama.2020.13761.

- Zouheir Y, Atany T, Boudebouch N. Emergence and spread of resistant N. meningitidis implicated in invasive meningococcal diseases during the past decade (2008–2017). J Antibiot (Tokyo). 2019;72:185–88. doi:10.1038/s41429-018-0125-0.

- World Health Organization (WHO). National action plans on antimicrobial resistance; 2016 [accessed 2022 February 13]. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241509763

- Vekemans J, Hasso-Agopsowicz M, Kang G, Hausdorff WP, Fiore A, Tayler E, Klemm EJ, Laxminarayan R, Srikantiah P, Friede M, et al. Leveraging vaccines to reduce antibiotic use and prevent antimicrobial resistance: a World Health Organization action framework. Clin Infect Dis. 2021;73:e1011–7. doi:10.1093/cid/ciab062.

- Marchetti F, Prato R, Viale P. Survey among Italian experts on existing vaccines’ role in limiting antibiotic resistance. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2021;17:4283–90. doi:10.1080/21645515.2021.1969853.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Meningoccal disease – diagnosis, treatment, prevention; 2022 [accessed 2022 February 9]. https://www.cdc.gov/meningococcal/about/diagnosis-treatment.html

- Cabellos C, Pelegrín I, Benavent E, Gudiol F, Tubau F, Garcia-Somoza D, Verdaguer R, Ariza J, Fernandez Viladrich P. Invasive meningococcal disease: what we should know, before it comes back. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2019;6: ofz059-ofz. doi:10.1093/ofid/ofz059.

- European Centre for Disease Prevention and Controll (ECDC). Public health management of sporadic cases of invasive meningococcal disease and their contacts; 2010 [accessed 2022 February 11]. https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/sites/default/files/media/en/publications/Publications/1010_GUI_Meningococcal_guidance.pdf

- Nadel S. Treatment of meningococcal disease. J Adolesc Health. 2016;59:S21–8. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2016.04.013.

- Bosis S, Mayer A, Esposito S. Meningococcal disease in childhood: epidemiology, clinical features and prevention. J Prev Med Hyg. 2015;56:E121–4.

- Haj-Hassan TA, Thompson MJ, Mayon-White RT, Ninis N, Harnden A, Smith LFP, Perera R, Mant DC. Which early ‘red flag’ symptoms identify children with meningococcal disease in primary care? Br J Gen Pract. 2011;61:e97–104. doi:10.3399/bjgp11X561131.

- Hovmand N, Christensen HC, Lundbo LF, Sandholdt H, Kronborg G, Darsø P, Anhøj J, Blomberg SNF, Bisgaard AT, Benfield T. Nonspecific symptoms dominate at first contact to emergency healthcare services among cases with invasive meningococcal disease. BMC Fam Pract. 2021;22:240. doi:10.1186/s12875-021-01585-8.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Meningoccal disease – signs and symptoms; 2022 https://www.cdc.gov/meningococcal/about/symptoms.html

- van de Beek D, Cabellos C, Dzupova O, Esposito S, Klein M, Kloek AT, Leib SL, Mourvillier B, Ostergaard C, Pagliano P, et al. ESCMID guideline: diagnosis and treatment of acute bacterial meningitis. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2016;22:S37–62. doi:10.1016/j.cmi.2016.01.007.

- Vázquez JA, Taha MK, Findlow J, Gupta S, Borrow R. Global meningococcal initiative: guidelines for diagnosis and confirmation of invasive meningococcal disease. Epidemiol Infect. 2016;144:3052–57. doi:10.1017/S0950268816001308.

- Olcén P, Fredlund H. Isolation, culture, and identification of meningococci from clinical specimens. Methods Mol Med. 2001;67:9–21.

- Moore JE. Meningococcal disease section 3: diagnosis and management: MeningoNI forum (see page 87(2) 83 for full list of authors). Ulster Med J. 2018;87:94–98.

- van Ettekoven Cn, van de Beek D, Brouwer MC. Update on community-acquired bacterial meningitis: guidance and challenges. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2017;23:601–06. doi:10.1016/j.cmi.2017.04.019.

- Thisyakorn U, Carlos J, Chotpitayasunondh T, Dien TM, Gonzales MLAM, Huong NTL, Ismail Z, Nordin MM, Ong-Lim ALT, Tantawichien T, et al. Invasive meningococcal disease in Malaysia, Philippines, Thailand, and Vietnam: an Asia-Pacific expert group perspective on current epidemiology and vaccination policies. Hum Vacc Immunotherap. 2022;18:2110759. doi:10.1080/21645515.2022.2110759

- Panatto D, Amicizia D, Lai PL, Cristina ML, Domnich A, Gasparini R. New versus old meningococcal group B vaccines: how the new ones may benefit infants & toddlers. Indian J Med Res. 2013;138:835–46.

- dtiNews. Meningococcal meningitis spreads in five Vietnam localities; 2012 [accessed 2022 February 10]. http://dtinews.vn/en/news/017004/20684/meningococcal-meningitis-spreads-in-five-vietnam-localities.html

- Soumahoro L, Abitbol V, Vicic N, Bekkat-Berkani R, Safadi MAP. Meningococcal disease outbreaks: a moving target and a case for routine preventative vaccination. Infect Dis Ther. 2021;10:1949–88. doi:10.1007/s40121-021-00499-3.

- White CP, Scott J. Meningococcal serogroup C conjugate vaccination in Canada: how far have we progressed? How far do we have to go? Can J Public Health. 2010;101:12–14. doi:10.1007/BF03405553.

- Argante L, Abbing-Karahagopian V, Vadivelu K, Rappuoli R, Medini D. A re-assessment of 4cmenb vaccine effectiveness against serogroup B invasive meningococcal disease in England based on an incidence model. BMC Infect Dis. 2021;21:1244. doi:10.1186/s12879-021-06906-x.

- Wang B, Giles L, Andraweera P, McMillan M, Almond S, Beazley R, Mitchell J, Lally N, Ahoure M, Denehy E, et al. Effectiveness and impact of the 4cmenb vaccine against invasive serogroup B meningococcal disease and gonorrhoea in an infant, child, and adolescent programme: an observational cohort and case-control study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2022;22:1011–20. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(21)00754-4.