ABSTRACT

A disparity in the uptake of the Human papillomavirus vaccine (HPVV) among immigrants and refugees leads to a social gradient in health. Recognizing that immigrants and refugees may encounter unique barriers to accessing prevention and care, this study seeks to determine barriers to and facilitators of HPVV among these subgroups to uncover high-resolution quality improvement targets of investment for under-immunized pockets of the population. The study undertook a qualitative inquiry into understanding immigrant and refugee parents’ perspectives on HPV infection and HPVV experience through school-based programs. We collected data first through short online surveys (N = 15) followed by one-on-one interviews (N = 15) and then through detailed online surveys (N = 16) followed by focus group discussions (N = 3) with 4–6 participants per group discussion from different groups: Black, South Asian and West Asian. Analysis of surveys and interviews identified that: information, awareness, and education about HPV infection and HPVV were among the most cited barriers that impede the uptake of HPVV. Moreover, vaccine-related logistics were equally important, including not having immunization information packages in different languages and relying solely on the child to bring home packages in paper copies from school-based vaccine programs. A multi-component intervention remains instrumental in enhancing HPV immunization rates, given the inconsistent uptake of HPVV by these subgroups who voice unique barriers and facilitators. An educational campaign that involves educating parents who consent for their child(ren) for HPVV, the children receiving the vaccination, and training staff providing HPVV through school-based immunization programs would be paramount.

Introduction

Human Papillomavirus (HPV) is the most common sexually transmitted infection.Citation1 More than 75% of sexually active Canadians will contract at least one HPV infection in their lifetime.Citation2 Current estimates (2023) indicate that 1422 Canadian women are diagnosed with cervical cancer yearly, and 637 die from it.Citation3 Carcinogenic HPV genotypes are responsible for almost 5% of all human cancers,Citation4 and about 70% of invasive cervical cancers are attributed to HPVs 16 or 18.Citation3 Oncosims model projections indicate that increasing HPVV uptake to 90% from 67% would result in a 23% reduction in cervical cancer incidence rates, which in turn causes a 23% decline in the average annual cervical cancer mortality rate.Citation5

Since the successful launch of Human Papilloma Virus Vaccination (HPVV) across Canada, achieving and maintaining optimal HPVV coverage throughout the country has remained challenging, particularly against a background of anti-vaccine activism, that has reversed some early gains.Citation6 Despite a widespread effort to implement publicly funded HPVV programs throughout Canada, the uptake of HPVV remained suboptimal in some Canadian jurisdictions.Citation7 Suboptimal uptake of HPVV could partly be because its impact on cancer prevention is still not realized adequately.Citation8 Saskatchewan (SK) remains below the national target for HPVV uptake and is amongst the provinces with the lowest uptake rates in the country.Citation9

The burden of cervical cancer remains disproportionately high among socioeconomically disadvantaged women.Citation10 More than 85% of cervical cancers occur in women with low socio-economic status (SES).Citation11 Also, cervical screening has been underutilized, specifically among women from low SES, immigrants, and Indigenous women.Citation12 Moreover, Canadian studies have shown that immigrant populations in Canada tend to have lower vaccination rates for some routine vaccines hence, these population subgroups have higher vaccine-preventable disease-related hospitalizations than their Canadian-born counterparts.Citation13,Citation14 A systematic review of the uptake of HPVV found that newcomers encounter unique challenges to HPVV uptake, such as insufficient knowledge about HPVV and the virus, insufficient access to health care, cultural beliefs about sexuality, etc.Citation15 which impede their HPVV uptake. These factors contribute to disparities in the uptake of HPVV; hence, creating a social gradient in health.Citation16

Given Canada’s significant investments in implementing HPVV programs, ensuring its utility across all subgroups of populations is critical, especially for those at a greater risk of developing HPV-related diseases, i.e., cervical cancers. On a related note, it is important to note that, like any infection, the risk of contracting HPV infection depends on various factors: individual risk factors (i.e. sexual orientation, vaccine status, etc.), social risk factors and sexual risk factors (i.e. vaccine coverage, etc.).Citation17 Therefore, HPVV coverage assessment and understanding the drivers of HPVV uptake is vital in all settings, employing a variety of study approaches since a higher overall vaccine uptake rate may obscure lower HPVV uptake in subgroups of the most susceptible populations.Citation17

The arguments articulated herein demonstrate a focus on the Social Determinants of Health (SDoH). It is essential to recognize that unless designed with a powerful equity lens, policies that target the populations’ health promotion, in general, can inadvertently act to increase the existing difference in people’s health belonging to different SES.Citation11 Against this background, there is a need for a vulnerable population intervention framework to address the limitations of the whole population approach intervention framework.Citation18 Despite widespread efforts to launch and operationalize publicly funded HPVV programs, HPVV uptake has remained suboptimal in some Canadian jurisdictions, including Saskatchewan (SK).Citation19

SK remains below the national target for HPV coverage rates.Citation19 School closures during the COVID-19 pandemic have challenged HPVV uptake further due to the abrupt disruption of vaccination programs in schools.Citation20 HPVV uptake rates from the school year (2018–19) for girls only (based on the most recent available data) is 76.5% for the first dose and 69.1% for the second dose from the total size of eligible girls cohort.Citation19 No data on HPVV uptake rates for the same years for boys is reported.Citation19

The rate of cervical cancer among Canadian women has not declined since 2005. The suboptimal uptake of HPVV with a status quo of cervical cancer incidence rate is mainly because HPV immunization’s impact on cancer prevention has not been realized adequately by vaccine providers and receivers (patients). A Social Determinants of Health (SDOH) approach reinforces prioritization to invest in HPVV uptake efforts among sub-populations who may be less likely to get the HPVV due to encountering unique barriers in accessing healthcare and prevention. The determinants of HPVV uptake play a crucial role in the etiological cascade of HPV-related cancer development. COVID-19 has further impacted some populations more than others, exacerbating the inequities many racialized and marginalized communities face.

The performance of public health systems includes “equity” as a measure of success. Therefore, identifying SDOH leverage points by exploring peoples’ perspectives on HPVV uptake at different levels (i.e., patient, provider, and system level) is critical to combat inequalities and barriers to HPVV uptake.

Therefore, we designed a project that seeks to understand people’s perspectives on the barriers and facilitators in the uptake of HPVV. The project aimed to first (a) determine current-state-of-science on the factors that influence the uptake of HPV vaccine across English Canada,Citation21 then (b) explore people’s perspectives on the uptake of the HPVV through school-based programs at three levels: patients-, providers- and system -level, across Saskatchewan and (c) determine the COVID-19 pandemic related disruption of the school-based program HPVV program across SK. This paper reports findings from the patient-level perspective from the city of Saskatoon under objective (b). The system and provider-level perspectives gathered from across Saskatchewan are reported elsewhere. In the context of this study, patients are migrant parents. Migrants are individuals who move from one place to another, within the country or outside, whereas immigrants are individuals who move from their country of origin to another country, ensuring legal formalities.Citation22

Methods

Study design

This overall study is situated in a pragmatismCitation23 grounded Qualitative Sequential Mixed Method designCitation24 with an Interpretive Description approach.Citation25 This paper focuses on findings from our exploration of patient-level perspective on the barriers to and facilitators of HPVV uptake through school-based vaccine programs, guided by the following question: (1) What do migrant (immigrants and refugees) parents of eligible children identify as barriers and facilitators in receiving HPV immunization in Saskatoon?

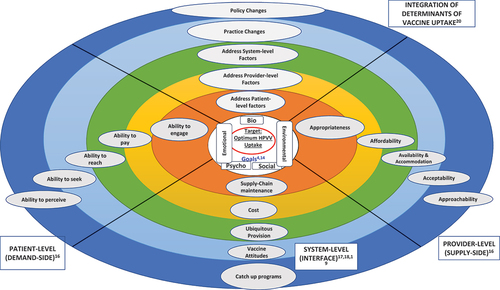

We used an adapted framework we developed in addressing our study’s objective of patients’ perspectives on the uptake of the HPVV through school-based programs. We adapted the Engels biopsychosocial concept modelCitation26 and Levesque frameworksCitation27 and combined them into a new comprehensive framework called A. Khan’s framework for access to care and prevention,Citation21 that informs the inquiry covered in this paper. Refer to ().

Study setting

During the first two decades of the 20th century, SK had one of the highest immigration rates in Canada.Citation28 By 1931 the proportion of immigrants reached more than a third (34.6%) of the SK’s population, the majority from Western and Eastern Europe.Citation28 Over the years, the ethnocultural composition of immigrants to SK changed dramatically, with a high proportion of black and racialized communities. According to the 2021 census, immigrants comprise the largest proportion of the population in the country’s history, and SK is catching up with this trend.Citation29 Recent immigrants (who arrived in the five years before the census) comprised 31.3% of the total immigrant population in SK. It is projected that immigrants will be the driver of population growth in Saskatchewan and across the country.Citation29 Most immigrants to SK prefer to settle in Saskatoon or Regina; therefore, its population composition is ethnically diverse. This study was conducted in Saskatoon, SK, the largest city in the province. In SK, HPVV is offered mainly through publicly funded school-based vaccination programs, and specialized immunization clinics also administer HPVV to catch up for missed opportunities. Gardasil 9 is administered according to the National Advisory Committee on Immunization schedule for HPVVCitation30 to school children in grade 6. Individuals between the ages of 9 and 26 who missed school HPVV dose can get it at a public health immunization clinic.Citation30 In SK, HPVV is offered for free until the 27th birthday. Public health nurses collect informed consent letters and administer the vaccines.

Participant sampling

Using a purposive sampling strategy, we conducted participant recruitment aiming for a diversity of participants based on migration status (immigrant or refugee), ethnicity, and duration of stay in Canada since we aimed to procure rich insights and gather multiple and different perspectives on barriers to and facilitators of HPVV uptake among these subgroups. In purposive sampling, the researchers identify members of the population who are likely to possess certain characteristics or experiences and maybe willing to share them.Citation31 Patient-level participants broadly represent the following subgroups: very recent immigrants (landed immigrants who had been in Canada for five years or less), recent immigrants (landed immigrants for more than 5 to 10 years in Canada), established immigrants (landed immigrants for more than 10 years), and refugee (landed as a refugee) who are parents or caregivers of youth aged 9–18 years. We recruited parents or caregivers because HPVV is offered to grade six children after parental or caregiver consent.

We collaborated with the Saskatoon Open Door Society (SODS),Citation32 a nonprofit organization and part of Reconciliation Saskatoon. SODS helps immigrants and refugees connect to build and promote a diverse and inclusive community to develop a sense of belonging and participate in social, economic, intellectual, and cultural life.Citation32 In collaboration with the research support team at SODS, we recruited study participants for interviews and Focus Group Discussions (FGDs). The research support team posted paper posters of the study and circulated the e-poster among the target population subgroups. Working closely with the research support team at SODS, a population health research specialist recruited the participants. Although the research support team reached the same target population for interviews and FGDs, different participants were recruited based on migration status and ethnicity each time. Only a few Black and South Asian migrant parents participated in both individual interviews as well as in FGDs. Since the refugee population was underrepresented in interviews, we contacted a larger group of refugees across Saskatoon through the SODs for participant recruitment for FGDs.

Participant recruitment material consisting of an invitation letter, an information sheet briefly describing the study, and a consent form was sent to all participants willing to be interviewed. Population health research specialists scheduled interviews for the participants willing to participate and sent a brief survey to all participants to complete before the interview. We made it clear on the recruitment poster and the information material shared that we would provide participants with an honorarium to acknowledge their time for this study and that consenting to be interviewed would contribute to a better understanding of the problem in question. We conducted all the interviews online on the participants’ preferred days and times.

Data collection

We first conducted 15 one-on-one semi-structured interviews and collected 15 responses for short online anonymous surveys between August and September 2022. We then held three Focus Group Discussions (FGDs) between January and February 2023 and collected 16 responses for the detailed online anonymous surveys. Each FGD-involved participant ranged from (4 to 6) with the following subgroups: FGD-1: Black migrant parents (n = 6), FGD-2: South Asian parents (n = 5) and FGD-3: West Asian refugee parents (n = 5).

Based on the participants’ preferences, we conducted all interviews online using virtual platforms (either Zoom or Webex) in Saskatoon at the research specialist’s office at Royal University Hospital. We used translation services for Mandarin and Afghan languages for one individual interview and one FGD. We audio-recorded all the interviews (individual and group) using the audio recorder borrowed from the Canadian Hub for Applied and Social Research (CHASR), University of Saskatchewan. The interviews lasted 1 to 1.5 hours, whereas FGDs lasted a maximum of 2 hours.

Our review ofCitation21 the barriers and facilitators in the HPVV uptake across English Canada informed questions of the interview guide we used to facilitate the interviews. The questions in the interview guide were based on the key themes related to the barriers to and facilitators of HPVV uptake in the broader context (English Canada).Citation21 In the interviews, we explored participants understanding of HPV infection and HPVV. We asked questions related to (1) their knowledge and understanding of HPV infection and HPVV, (2) their experience with school based HPVV programs, (3) factors they consider important in deciding on HPVV for their child (ren) and (4) possible solutions to enhance HPVV uptake. The short online surveys we sent out to the participants collected data on the demographic characteristics through 6-item questionnaires.

Based on the high-level findings from the interview data, we created a new interview guide for FGDs and detailed surveys. We sent a detailed survey that contained a 19-item questionnaire and collected information on the demographic characteristics of the respondents and assessed their knowledge about HPV and their experience with the HPVV school-based program.

Strategies for establishing trustworthiness of findings

Qualitative studies often face criticism due to lacking validity and reliability. Validity criteria have long been viewed under the quantitative paradigm, which Lincoln and Guba restated as trustworthiness criteria.Citation33 Drawing from Lincoln and Guba’s ideologyCitation33 and adopting some strategies proposed by Tracy,Citation34 this study ensured trustworthiness using the following: crystallization, member checking and peer debriefing. Crystallization is akin to triangulation, where data from different sources are compared and analyzed to find convergences. In carrying out crystallization, however, the researcher will crystallize instead of triangulate since crystallization recognizes that there are far more than “three sides” to approach the worldCitation35

Citation35 In this study, data was collected in a phased manner (initial interviews and follow-up group interviews), and multiple data sources were used (interview data as well as data from surveys), reflecting the use of different data types. This technique allowed me to visualize multiple realities and their varied meanings from different angles/dimensions where a search for convergence is not desired, but room for nuances is offered. Hence, developing unique ways to understand drivers of low HPV vaccine uptake despite the potential of vaccines to prevent HPV-linked cancers.

Data analysis

Audio-recorded interview data were transcribed verbatim by a transcription specialist at CHASR. We conducted data analysis using a thematic analysis approach adopting a hybrid coding strategy and following the six pragmatic steps proposed by Braun and Clark.Citation36 The six steps included data familiarization, generating initial coding, searching for themes, reviewing the themes, defining, and naming the themes and writing the report.Citation36 Qualitative research software NVIVO 12 facilitated the data analysis process. The final themes and subthemes were discussed and agreed upon with other members of the research team expert in the qualitative research field.

The detailed surveys were collated and assessed for potential data grouping based on similarities and differences. We collected detailed surveys from participants from different ethnic origins and immigration statuses. We created descriptive data on demographic characteristics, knowledge about HPV and experience with HPVV school-based immunization programs from the detailed surveys. We adopted data crystallization strategies employing relevant study design, mixing methods, and creating different data sources, such as semi structured one-on-one interviews, focus group discussions and short surveys with a detailed follow-up survey.

Ethical considerations

We obtained approval from the University of Saskatchewan’s Behavioural Research Ethics Board (Application ID#: 3545) for the study and the evaluation protocol that included recruitment strategies and data collection tools. We collected informed consent from all the participants before the interview. Before data analysis, we removed all identifying information from the verbatim transcripts.

Results

Interview participants survey responses: sociodemographic information

We collected responses from 15 respondents. The language of the survey was English. We collected 10 surveys from the female parent and five surveys from the male parent. The surveys revealed the following subgroups of migrants: very recent immigrants (landed immigrants who had been in Canada for five years or less), recent immigrants (landed immigrants for more than 5 to 10 years in Canada), established immigrants (landed immigrants for more than 10 years), refugee (landed as a refugee).

In terms of racial and ethnic identity, our surveys sampled different population subgroups: Black, South Asian, Chinese, and Southeast Asian. Moreover, the survey respondents reported having both male and female child (ren). Almost equal number of respondents reported to have been able to save some money after family expenditure at the end of the month. Finally, most of the respondents were found unaware of self HPVV status. For details on the sociodemographic information of the interview participants, please refer to .

Table 1. Sociodemographic information of Interview participants.

Focus group participants survey responses: sociodemographic information, knowledge about HPV infection and experience with HPV school-based immunization program

We conducted a total of three FGDs after interviews. We gathered responses from (N = 16) respondents with (n = 6) from the black immigrant parents’ group, (n = 5) from the South Asian and Southeast Asian immigrant parents groups, and (n = 5) from the West Asian refugee parents’ group. Concerning parental status, we found nearly a half-and-half divide between mothers (N = 7) and fathers (N = 8) interviewed along with one guardian (N = 1). Most of the parents fell in the age range of 40–50 (N = 9) and followed by the age range of 30–40 (N = 3) and the lowest from the age range 20–30 (N = 2) and 50–60 (N = 2), respectively. Participants’ duration of stay in Canada varied widely, ranging from 6 months to 17 years for immigrants for Blacks and Asians together, and this was 4 to 6 months for the refugee group. When asked if they have experience with school based HPVV programs, (N = 10) responded ‘yes’ and (N = 6) answered ‘no.’

Overall, while the majority of the participants reported a certain level of knowledge, a surprising percentage did not. For example, 56.5% of respondents reported knowing that HPV is a sexually transmitted infection. Similarly, 56.5% of respondents reported knowing that HPV infection can cause cancer of the cervix, throat, anus, and male and female genitalia; responses from the remaining varied from no, do not know, to unsure. When asked for opinions on the best way to educate people about HPV infection and HPVV, 68.7% of participants opted for awareness through social media. We found a half-and-half divide between participants’ responses on their preferred way of receiving immunization information packages, with 50% opting for electronic and the rest for a combination method, via the Edsby school app or a paper copy.

While 68.7% of respondents reported being very comfortable reading and understanding the immunization material, the remaining 31.3% of respondents were either somewhat comfortable or not comfortable at all. The survey found that about 56.3% were unaware if the immunization information material was present in languages other than English; however, 43.7% were aware of this. Interestingly, 62.5% of participants reported having insufficient time to review the immunization information material, and 37.5% thought they had sufficient time to review.

When asked if the respondents prefer school-based vaccine programs, 62.5% reported ‘yes.’ However, 37.5% did not prefer it. Interestingly, the same percentage of respondents reported being comfortable with the school HPV vaccine clinic timing, and the remaining were not. Surprisingly, only 25% of the respondents reported having all the information they needed to make good decisions about immunizing their child with the HPVV. On similar lines, 31.3% of respondents reported being comfortable arranging previous vaccine records of their child(ren) from a previous country or province. Finally, 43.7% of the respondents said that the COVID Vaccine experience changed their attitude toward vaccines, and 56.3% reported that this experience increased their likelihood of getting other vaccines. For details, please refer to .

Table 2. Focus group participant survey responses: socio-demographic characteristics.

Table 3. Focus group participant survey responses: knowledge about HPV infection and experience with HPV school-based immunization program.

Patient-level barriers to and facilitators of HPVV uptake

We report the barriers and facilitators of HPVV uptake from individual and group interviews (FGD) based on the key themes. The key themes are: 1. Information, Awareness and Education. 2. HPV Vaccine-Related Logistics. In reporting results, the themes are divided into subthemes related to barriers and facilitators. Interestingly, similar key themes were found in the individual interviews and FGD.

Information, awareness & education: barriers

Based on A. Khan’s framework for access to care and prevention,Citation21 the first key theme, ‘information, awareness, and education’ and the corresponding subthemes fall under the following determinants of HPVV uptake: the ability to perceive and engage, which are navigated by the psycho-social components of individuals’ life. provides details on migrant parents’ perception of barriers to and facilitators of HPVV in the interviews and FGDs with key themes, subthemes, and exemplar quotes.

Table 4. Migrant Parents’ perception of barriers to and facilitators of HPV vaccination in interviews and FGD: key themes and exemplar quote.

Parents expressed a lack of information, low literacy, and inadequate information about HPV infection and HPVV. Many parents reported they never knew about HPVV before, and this was their first time learning about such a virus that can cause cancer and is preventable through the HPV vaccine. Some parents thought HPVV was for girls only because that was a predominant notion in their home country, and girls are mainly offered these vaccines. Some of the parents who had once heard about HPVV were uncertain about the safety of this vaccine. Parents were confused about the possibility of contracting HPV infection in a monogamous relationship. Many participants believed that one could not get an HPV infection if he/she is in a monogamous relationship, which determines the need to take HPVV or not. Parents articulated that their skepticism about the HPVV mainly stems from their lack of understanding of the HPV infection and the HPVV. Misconceptions that HPVV would induce promiscuity in children further add to parents’ skepticism about HPVV.

I was not sure about what HPV or vaccine is? The other thing is that they are not sexually active, so why do they need it? Also, is this vaccine safe for them or not? That was another question for me. I didn’t think it was necessary for them, and for me to think it is important for them … … … . (Black immigrant parent, Interview #15)

Many parents were uncomfortable with the idea of providing HPVV to young folks, especially when parents believe that their child(ren) is sexually inactive and, therefore, it is not the right age to provide HPVV. Some parents also expressed concerns that providing HPVV to younger folks might mean increasing their susceptibility to early involvement in sexual activities, as giving them this vaccine is akin to preparing them for sex. Many parents were also concerned that seeking HPVV may make their child(ren) promiscuous. Also, a few parents reflected on their immunization history as a child and thought that HPV was a newer vaccine as they did not get one or another name for the BCG vaccine they got. The majority of the parents cited HPVV skepticism mainly due to their lack of clear understanding of HPVV.

Because of not understanding what HPV is, and even you understand what HPV is, you might have some misconceptions about the vaccination. And that could be thinking that “Oh, if I get my child vaccinated with HPV, maybe they would become sexually active early” and, “Oh, because I feel my kids’ age is not right for sex, so why should I get myself bothered about vaccination on HPV? … … .(West Asian Refugee Parents, FGD 2)

Information, awareness & education: facilitators

Many parents strongly believed that ‘Prevention is Better than Cure.’ Parents articulated that despite their vague or incomplete understanding of the HPV infection and HPV vaccine, they would still want to seek the HPVV because they believe it’s better to prevent the HPV infection than to get it treated and cured after the development of the disease. Parents expressed the desire to understand the basics of HPV infection and the HPVV. They emphasized the need to create awareness around HPV infection, its consequences, and prevention through proper educational workshops and campaigns. Parents advocated adopting the COVID-19 model for HPVV.

Parents expressed frustration about not knowing about HPV infection and the potential of HPV-linked cancer development and cited Hepatitis B, C and HIV as examples they know. Still, they wondered what could stop them from learning about HPV, especially when the infection in question could potentially cause cancer of the female and male genital regions, mouth and throat. Parents, therefore, emphasized the great need to adopt the COVID model to spread HPVV awareness and increase the likelihood of its uptake.

Parents naturally respond fairly to anything that has to do with the kids. As people have already said, we should try a campaign. There should be a serious campaign about HPV. Because most people like me, honestly, I heard about it last year when we had individual interviews. The point is that the HPV vaccine needs more promotion. They need to make people more aware that it should become something everybody knows about. Like AIDS, nobody we see that doesn’t know what AIDS is all about. Nobody we see doesn’t know; even small kids would tell you what COVID-19 is and what the vaccine is. There should be more sensitizations, and people through the school program should be promoted through different mediums. (Black Immigrant Parents, FGD 3)

Parents suggested youths’ education through different mediums for creating awareness and spreading information. Parents highlighted the need for youths’ education about HPV infections, HPV-linked cancers, and HPVV, as children are the end users and are administered HPVV in their arms. Parents cited difficulty exchanging information with their child(ren) due to not understanding HPV disease and HPVV. Parents, therefore, suggested using multiple mediums such as social media, game apps, you-tube add, and posters in school to make children aware of the HPV infection and why HPV vaccines are important. Moreover, parents suggested an educational campaign and a talk at school tailored to the level of grade sixers about the need to get HPV vaccines.

There should be some other medium it gets through. Some people don’t read their messages or sheets at times. We are all different. There should be some other medium to get it through such as social media or some other things to promote a campaign. We are different. I would like my kids to be educated. There can be some videos, there can be some posters, there can be some talks even in the school, so they can get some knowledge from their school. So, it would be a nice idea if they get some education, like the other education they are getting from school. (West Asian Refugee Parents, FGD 2)

Parents urged that physicians and other Health Care Providers (HCP) recommendations remain instrumental in improving HPVV coverage overall. Parents believed physicians and other HCPs are trusted well in society, and their recommendation would likely result in seeking HPVV and enhancing the HPVV uptake rates. Parents trust HCPs and said that they do not need to self-explore or research the type of vaccine their HCP recommends, and it increases their confidence in the vaccine. Parents cited that vaccine information from a trusted source is a significant factor in helping them decide to get their child (ren) vaccinated against HPV.

Of course, like everybody else was saying that when our healthcare provider gives us some information, we actually hold onto it, and we actually take action on it. If my healthcare provider says, “Get an HPV vaccine.” I’ll probably just get it; I will not even probably investigate much on it. I’ll make sure I get the vaccine . … .(South Asian Immigrant Parents, FGD 1)

Vaccine-related logistics: barriers

Based on A. Khan’s framework for access to care and prevention,Citation21 the second key theme, ‘vaccine-related logistics’ and the corresponding subthemes fall under the following determinants of HPVV uptake: the ability to seek and reach, which are navigated by the environmental/contextual components of individuals’ life.

Parents expressed great concern about the vaccine information sheet being too technical and difficult to understand by the lay public; therefore, it is a barrier to deciding about consenting for HPVV. Parents articulated issues keeping track of paper-based immunization packages their child(ren) is supposed to bring home and cited concerns about the potential loss of paper copies. Parents were frustrated about the medium of transportation of immunization packages which relies solely on a child to hand in the material to parents and return it to the school. Many parents, therefore, suggested a paperless mode and encouraged sending immunization packages electronically to the parents.

Some parents also suggested adopting a hybrid approach (paper and electronic copy) to send immunization packages home. In addition, parents found the consent form lengthy and difficult to follow and complete. Parents felt that filling out the consent form was akin to writing an exam as it included a series of questions at a time that they had to recall. Parents suggested having a brief and precise consent form so that they are comfortable filling it. Parents suggested reducing the number of items (questions) included in the consent form because, at times, they complete the form with a vague and incomplete understanding of the vaccine.

From school only, the information material was not too obvious. It was not something that I learned about HPV. So, I didn’t get my older ones vaccinated for the HPV vaccine actually because I thought that as my kids are not sexually active, they don’t need a vaccine. They don’t need a vaccine, so I didn’t get them vaccinated for HPV” … .(Black Immigrant Parent, Interview#7).“They know, you want to explain what kind of vaccination they’re taking and what it is for because sometimes you’re just putting the abbreviations and names of that stuff. Nobody knows what their use is. You put out the brief of what this one is, what it prevents, if it has any side effects, and stuff like that. So, a layperson can understand that by just going through that. Also, it must be brief so that nobody can read two pages of such material. … .(Black immigrant parent, Interview#11)

Parents voiced concerns about insufficient venues for HPVV delivery and administration to schoolgoers, which is challenged by only a one-time offer of HPVV through school-based vaccine programs. If a child misses this opportunity, there is no make-up day for the missed opportunity. Parents must book an appointment from public health clinics where preschoolers are predominantly given vaccinations. Parents articulated the need to bring vaccine programs to the doorstep by offering an HPVV clinic on alternate days and outside school premises for improved HPVV coverage. Parents believed that providing different opportunities to seek HPVV for their child(ren) would be a better strategy than only providing HPVV through school-based immunization programs.

Not the timing but frequency, I will say, because there have been times when there was a vaccine day in the school and incidentally, same day because I didn’t know, I had another appointment booked for myself that I could not cancel. I had to take my child over there, and then they said there would not be another vaccine day in the school. You now have to go to the health center and get him vaccinated. Maybe if they have a simple thing as a school picture, they have repeat days that if somebody has missed one day, they can get their picture taken two days later. They could also have a repeat day or leftover day for the vaccine day as well. … … .(South Asian Immigrant Parent, Interview#12)

Vaccine-related logistics: facilitators

Most parents highlighted the need for the vaccine info sheet in a different language. Parents articulated that providing the vaccine information material in English and French is insufficient to make the consent sorting process smoother. Many parents do not read the vaccine information material; if they do, they do not understand it completely. In both cases, it results in either not providing consent for HPVV for their child (ren) or consent without information. Parents suggested creating a vaccine information sheet in simple English without using medical terminologies and in layman’s language would be the best option for enhancing their understanding and confidence in the vaccine. Parents believed that creating versions of the vaccine information sheet in layman’s style and translating the material into different languages would facilitate clear messaging about the HPV infection and the vaccine.

The kind of information I would like to see is that the information sheet should be made available to everybody in different languages because some people actually don’t really read the sheet, I know people don’t read English. If we could have multilingual information sheets for families that are not English based, that would make lots of sense. Also, there are some basic languages that we have; we know Mandarin, and we know Arabic. We know that a few languages are predominant — they are dominating Saskatchewan quite a bit. And so, seeing those basic pamphlets online, that would be great if we could click it and it opens in my language. I would love that. (South Asian Immigrant Parents, FGD 1)

Parents also suggested elaborating on the ‘what, why and how’ of the HPV infection and HPVV in non-medical terms and at level one. Parents cited that reading the word ‘sexual’ without a clear understanding of the disease and vaccine under question creates stigma and keeps them in a vicious cycle of not knowing about the disease and vaccine and not wanting to know about it. Parents, therefore, suggested elaboration on the word ‘sexual’ when written in the context of sexually transmitted diseases is important in the context of younger folks who are sexually not active.

Of course, the information sheets is something that, if I don’t understand clearly, I’m not going to mark a check on the consent form. If I’m not understanding what HPV means because it’s confusing to me, I will, just to be on safe side, I won’t put a check mark next to the consent form. Also, if you put a word “sexual” in front on the sheet, it kind of becomes a big taboo. And without understanding it, people will not consent to it because there’s the word “sexual” on there. So, it can be sexually transmitted disease. Just like the other participant said, my kid is not sexually active, so they’re not going to get it. We don’t think about the future, we are just thinking about right now and that can be a really big thing, especially for some cultures. So, explain clearly. (Black Immigrant Parents, FGD 3)

Parents suggested having a catch-up day for HPVV for those who could not get their HPVV shots when offered for the first time would prove an influential factor in enhancing HPV coverage overall. Parents emphasized the continuation of the practice of seeking suitable times from parents for setting up school vaccine clinics and administering HPVV administration to their child(ren). Parents believed that offering an alternate day for the HPVV vaccine and setting up a vaccine clinic within school hours near the time of dismal were two critical factors that would substantially increase HPVV uptake rates. Finally, parents emphasized that we should consider using all possible means of communication to get the message to the parents and get the HPV immunization program to the doorstep “easy to be availed.”

Discussion

The study aimed to gain an in-depth understanding of patient-level perspectives (vaccine receivers) on the uptake of HPVV. We found parents perceive that (a) information, awareness and education and (b) vaccine-related logistics are the key factors that influence the uptake of HPVV. Parents’ lack of knowledge about HPV infection and HPVV and low literacy around the same have fueled the prevailing misconceptions and myths about the HPV vaccine. As a result, there is a stigma attached to the HPV vaccine. Therefore, unawareness about the HPV infection and vaccine, lack of opportunities for exchanging the right information and inadequate immunization information material from school-based programs add to suboptimal uptake of the HPVV.

Parents’ concerns about HPVV safety, uncertainty about eligibility, and reluctance to get HPVV for youth, especially when parents believe they are not sexually active, impede HPVV uptake. Misconceptions that HPVV has a gender association and that only females should get it to protect themselves from cervical cancers are significant barriers to effective HPVV uptake by all. As a corollary, awareness about HPV infection, HPVV education, and having the right information to facilitate HPVV uptake is critical as parents will be confident to consent for their child (ren) to get HPVV. Vaccine-related logistics are found equally important if not more, that influence the uptake of HPVV. Among the vaccine-related logistics, factors such as the mode of delivery of the immunization packages (i.e. paper vs. electronic copies) and the medium of delivery (i.e. a child who brings the immunization package in and returns it to the school) are the most influential factors in the uptake of HPVV. Thus, findings from our study highlight that ‘vaccine communication,’ either through public messaging or school immunization packages, is vital in enhancing ‘vaccine coverage’ in all settings.

When comparing findings from interviews and FGDs, most of the findings from interviews confirm key themes from FGDs and that several sub-themes from both also overlap. Example: 1. Parental and youth education, the role of school, providing the right information and addressing misconceptions. 2. Critiques on the vaccine information sheet in terms of content included being too technical to follow, English as the only language used and the distribution of immunization material predominantly via paper copies. Interestingly, healthcare providers’ recommendation was also identified as a strong facilitator in the uptake of HPVV in interviews as well as FGDs. FGDs, however, gave a closer look into the nature of barriers migrant and refugee parents encounter around the uptake of HPVV through school-based programs and potential solutions to address those. In addition to identifying the potential facilitators, FGDs highlighted that already operating factors could prove valuable facilitators if they remain functional, e.g., school vaccine clinic times.

The study supports the literature that vaccine attitudes drive vaccine decisions, and knowledge, attitudes, and beliefs shape those.Citation37 Our study resonates with the literature that the HPVV uptake increases with increased awareness about HPV infection, its consequence, and the role of HPVV.Citation38 Our study corroborated the factors important in HPVV uptake we had previously summarized in our review from across English CanadaCitation21 and with this study, in the context of SK at the receiver’s level (patient level). Our study built on the available literature in the following ways: the findings align with the literature showing that vaccine attitudes are directly proportional to vaccine literacy and vice-versa.Citation39 Our study additionally emphasizes that vaccine-related logistics are equally important factors in HPVV uptake just as knowledge, attitudes, and beliefs.

Our study supports the literature that various population subgroups, such as immigrant and refugee parents, encounter unique barriers to HPVV uptake and that knowledge insufficiency about HPV infection, the role of HPVV, and insufficient access to care and prevention are important factors that impact HPVV uptake.Citation15 We, however, did not find cultural beliefs-related barriers about sexuality to be a factor that impedes HPVV uptake, although parents very found generally found it uncomfortable when HPV vaccine was discussed in the context of sexually transmitted infection without clarity on reasons for recommendation to school-aged children who may not have been sexually active yet.The study adds to the literature that barriers and facilitators around HPVV uptake can vary even within the same population subgroup, such as migrants, based on many factors, where ethnic origin, migration status, and duration of stay in Canada are few to count on.

Strengths

At a procedural level, using a qualitative mixed method is the major strength of this study. It enables using different data collection techniques that provide an in-depth understanding of the topic area under investigation. Drawing from various data sources helped develop a refined sense of changes needed for population subgroups through the combination approach.Citation40

At a practical level, it provides a sophisticated example at the forefront of related research proceduresCitation40 and carries implications for practice, research, and education. At the policy level, the study has provided recommendations that include updating immunization guides tailored to suit the needs of migrant populations identified in this study.

Limitations

There were several limitations of our study: first, our study could not assess current area-based HPV immunization coverage rates of school-goers (grade sixers). Therefore, we could not study disparities in the uptake of HPV immunization across SK based on area based HPVV coverage rates. Second, our study interviewed participants from across the city of Saskatoon; the study did not target to interview parents specifically of the child (ren) who are not up to date for HPV immunization to explore barriers and facilitators they perceive in the uptake of HPVV. Third, our study’s findings do not guarantee generalizability outside of SK. The results can, however, guide thinking about creating robust vaccination programs for all population groups and subgroups in other jurisdictions. Finally, we relied on the translator to facilitate one FGD and one individual interview, which might have limited the original information from reaching us due to cross-translations.

While there might be more limitations associated with the study’s data-gathering components and beyond, the use of Qual-MMR involved the intentional collection and mixing of different data collection techniques and resultant data sources and the combination of each’s strengths in answering research questions and minimizing the weaknesses of each.

Conclusions

The study informs us that there cannot be a one-size-fits-all strategy that enhances the uptake of HPVV, and it requires a multi-component strategy to improve HPVV uptake rates. A multi-component approach remains instrumental, given the inconsistent uptake of HPVV by population subgroups who voice unique barriers and facilitators. An educational campaign that involves educating parents who consent for their child(ren), the child receiving the vaccination, and training of staff providing HPVV through school-based immunization programs could help improve HPVV immunization uptake rates among these subgroups. The study also suggests designing population-specific strategies to increase HPVV uptake rates by raising HPVV awareness, offering education, and tackling vaccine logistics-related factors. Educational workshops and provincial campaigns can address parental concerns, help dismantle myths, handle misinformation, improve HPVV belief and shift vaccine attitudes. Moreover, the study findings warrant further sub-group analysis with the established immigrants and refugees.

Facilitating immigrants and refugees in accessing and utilizing HPVV through better communication geared toward an improved understanding of HPV infection and the vaccine is paramount. In addition, supporting these subgroups in navigating through vaccine-related logistics, especially by providing vaccine information packages into different languages, is one of the most influential factors in the uptake of HPVV. Language is a part of communication that plays an instrumental role in the disease prevention, diagnosis, and treatment continuum.Citation41 Language transfers or exchanges information from person to person and serves as a communication system through which people develop knowledge and improve their understanding of a given issue.Citation42 Efforts to address barriers and incorporate facilitators this study suggests for immigrants and refugees might translate to also benefit other marginalized and vulnerable population subgroups. “An inclusive system for migrants may very well prove inclusive for all,”.Citation41(p60)

Consent for publication

I consent to publish data and images enclosed with this submission.

Acknowledgments

Thilina Bandara, Mika Rathwell, Charles Plante and Benjamin Neudorf.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Lee S. Human papillomavirus. Canadian Cancer Society; [accessed 2023 Apr 2]. https://cancer.ca/en/cancer-information/reduce-your-risk/get-vaccinated/human-papillomavirus-hpv.

- Canadian Cancer Statistics. 2020-Canadian-Cancer-Statistics-Special-Report-EN.pdf. Canadian Cancer Society; 2020. https://www.cancer.ca/en/cancer-information/cancer-101/canadian-cancer-statistics/?region=on.

- Bruni L, Albero G, Serrano B, Mena M, Collado JJ, Gómez D, Muñoz J, Bosch FX, de Sanjosé S. Human Papillomavirus and Related Diseases in Canada. Summary Report. Barcelona (Spain): ICO/IARC Information Centre on HPV and Cancer (HPV Information Centre); 2023.

- Bouvard V, Baan R, Straif K, Grosse Y, Secretan B, El Ghissassi F, Benbrahim-Tallaa L, Guha N, Freeman C, Galichet L, et al. A review of human carcinogens—Part B: biological agents. Lancet Oncol. 2009;10(4):321–14. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(09)70096-8.

- Smith A, Baines N, Memon S, Fitzgerald N, Chadder J, Politis C, Nicholson E, Earle C, Bryant H. Moving toward the elimination of cervical cancer: modelling the health and economic benefits of increasing uptake of human papillomavirus vaccines. Curr Oncol. 2019;26(2):80–4. doi:10.3747/co.26.4795.

- D’Souza G, Agrawal Y, Halpern J, Bodison S, Gillison ML. Oral sexual behaviors associated with prevalent oral human papillomavirus infection. J Infect Dis. 2009;199(9):1263–9. doi:10.1086/597755.

- Dubé E, Gagnon D, Clément P, Bettinger JA, Comeau JL, Deeks S, Guay M, MacDonald S, MacDonald NE, Mijovic H, et al. Challenges and opportunities of school-based HPV vaccination in Canada. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2019;15(7–8):1650–5. doi:10.1080/21645515.2018.1564440.

- Canadian Cancer Statistics. Special topic HPV-Associated cancers. Canadian Cancer Society; 2016. https://www.cancer.ca/~/media/cancer.ca/CW/cancer%20information/cancer%20101/Canadian%20cancer%20statistics/Canadian-Cancer-Statistics-2016-EN.pdf?la=en.

- Background and key statistics. Canadian partnership against cancer; Published 2021 Mar 29 [accessed 2023 Apr 2]. https://www.partnershipagainstcancer.ca/topics/hpv-immunization-policies/background-key-statistics/.

- Downs LS, Smith JS, Scarinci I, Flowers L, Parham G. The disparity of cervical cancer in diverse populations. Gynecol Oncol. 2008;109(2 Suppl):S22–S30. doi:10.1016/j.ygyno.2008.01.003.

- Brisson M, Drolet M. Global elimination of cervical cancer as a public health problem. Lancet Oncol. 2019;20(3):319–21. doi:10.1016/s1470-2045(19)30072-5.

- Hughes A, Mesher D, White J, Soldan K. Coverage of the English national human papillomavirus (HPV) immunisation programme among 12 to 17 year-old females by area-level deprivation score, England, 2008 to 2011. Euro Surveill. 2014;19(2). doi:10.2807/1560-7917.es2014.19.2.20677.

- Greenaway C, Greenwald ZR, Akaberi A, Song S, Passos-Castilho AM, Abou Chakra CN, Palayew A, Alabdulkarim B, Platt R, Azoulay L, et al. Epidemiology of varicella among immigrants and non-immigrants in Quebec, Canada, before and after the introduction of childhood varicella vaccination: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2021;21(1):116–26. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30277-2.

- Edward N, Sanmartin C, Elien-Massenat D, Manuel DG. Vaccine-preventable disease-related hospitalization among immigrants and refugees to Canada: study of linked population-based databases. Vaccine. 2016;34(37):4437–42. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2016.06.079.

- Wilson L, Rubens-Augustson T, Murphy M, Jardine C, Crowcroft N, Hui C, Wilson K. Barriers to immunization among newcomers: a systematic review. Vaccine. 2018;36(8):1055–62. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2018.01.025.

- Subramanyam MA, Kawachi I, Subramanian SV. Reactions to fair society, healthy lives (the marmot review). Social Sci Med. 2010;71(7):1221–2. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.07.002.

- Drolet M, Deeks SL, Kliewer E, Musto G, Lambert P, Brisson M. Can high overall human papillomavirus vaccination coverage hide sociodemographic inequalities? An ecological analysis in Canada. Vaccine. 2016;34(16):1874–80. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2016.02.069.

- Frohlich KL, Potvin L. Transcending the known in public health practice: the inequality paradox: the population approach and vulnerable populations. Am J Public Health. 2008;98(2):216–21. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2007.114777.

- Canadian Partnership Against Cancer. HPV immunization for the prevention of cervical cancer; 2021. https://s22457.pcdn.co/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/HPV-immunization-prevention-cervical-cancer-EN.pdf.

- Diamond LM, Clarfield LE, Forte M. Vaccinations against human papillomavirus missed because of COVID-19 may lead to a rise in preventable cervical cancer. CMAJ. 2021;193(37):E1467. doi:10.1503/cmaj.80082.

- Khan A, Abonyi S, Neudorf C. Barriers and facilitators in uptake of human papillomavirus vaccine across English Canada: a review. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2023;19(1):2176640. doi:10.1080/21645515.2023.2176640.

- Menon N. What is the difference between migration and immigration - GetGIS. GetGIS (Global Immigration Services); Published 2022 Nov 11 [accessed 2023 Sept 5]. https://getgis.org/blog/what-is-the-difference-between-migration-and-immigration.

- Saunders M, Lewis P, Thornhill A. Research Methods for Business Students. New York: Pearson education; 2009.

- Morse JM. Simultaneous and sequential qualitative mixed method designs. Qual Inq. 2010;16(6):483–91. doi:10.1177/1077800410364741.

- Thorne S. Interpretive Description: Qualitative Research for Applied Practice. London (NY): Routledge, Taylor and Francis Group; 2016.

- Engel GL. The clinical application of the biopsychosocial model. J Med Philos. 1981;6(2):101–23. doi:10.1093/jmp/6.2.101.

- Levesque JF, Harris MF, Russell G. Patient-centred access to health care: conceptualising access at the interface of health systems and populations. Int J Equity Health. 2013;12(1):18. doi:10.1186/1475-9276-12-18.

- Anderson A. The encyclopedia of saskatchewan; Published 2006 [accessed 2023 Mar 30]. https://esask.uregina.ca/entry/population_trends.jsp.

- Dayal P. 12.5 per cent of Sask. population is now immigrants: 2021 census. CBC News; Published 2022 Oct 27 [accessed 2023 Apr 18]. https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/saskatoon/immigration-is-driving-population-growth-in-saskatchewan-1.6630693.

- Saskatchewan. Canadian partnership against cancer. Published 2022 Nov 15 [accessed 2023 Sept 5]. https://www.partnershipagainstcancer.ca/topics/hpv-vaccine-access-2022/saskatchewan/.

- Nikolopoulou K. What is purposive sampling? Scribbr. Published 2022 Aug 12 [accessed 2023 Sept 5]. https://www.scribbr.co.uk/research-methods/purposive-sampling-method/.

- Saskatoon Open Door Society. Start your life in saskatoon. Published 2023 [accessed 2023 Mar 31]. https://www.sods.sk.ca/.

- Lincoln YS, Guba EG. Naturalistic Inquiry. Texas (USA): SAGE; 1985.

- Tracy SJ. Qualitative quality: eight “Big-Tent” criteria for excellent qualitative research. Qual Inq. 2010;16(10):837–51. doi:10.1177/1077800410383121.

- Richardson L, Pierre EAS. 36 Writing: A Method of Inquiry. Published online 2000. http://daneshnamehicsa.ir/userfiles/file/Manabeh/Manabeh03/Writing%20%20A%20Method%20of%20Inquiry.pdf.

- Rezaei Aghdam A, Watson J, Cliff C, Miah SJ. Improving the theoretical understanding toward patient-driven health care innovation through online value cocreation: systematic review. J Med Internet Res. 2020;22(4):e16324. doi:10.2196/16324.

- Cheng JYJ, Loong SSE, CESM H, Ng KJ, MMQ N, Chee RCH, Chin TXL, Fong FJY, Goh SLG, Venkatesh KNS, et al. Knowledge, attitudes, and practices of COVID-19 vaccination among adults in Singapore: a cross-sectional study. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2022;107(3):540. doi:10.4269/ajtmh.21-1259.

- Beyen MW, Bulto GA, Chaka EE, Debelo BT, Roga EY, Wakgari N, Danusa KT, Fekene DB. Human papillomavirus vaccination uptake and its associated factors among adolescent school girls in Ambo town, Oromia region, Ethiopia, 2020. PloS one. 2022;17(7):e0271237. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0271237.

- Shon EJ, Lee L. Effects of vaccine literacy, health beliefs, and flu vaccination on perceived physical health status among under/graduate students. Vaccines. 2023;11(4):765. doi:10.3390/vaccines11040765.

- Creswell JW, David Creswell J. Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches. USA: SAGE Publications; 2017.

- Galea S, Ettman CK, Zaman MH. Migration and health. University of Chicago Press; Published 2022 Nov [accessed 2023 Apr 2]. https://press.uchicago.edu/ucp/books/book/chicago/M/bo181540563.html.

- Kurniati E. The correlation of students’ listening habit in English conversation with vocabulary mastery of the second semester students’ English education at teacher training and education faculty at batanghari university academic year 2015/2016. Jurnal Ilmiah Universitas Batanghari Jambi. 2017;17:227–36.