?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

Group B streptococcus (GBS) is a major cause of neonatal death worldwide. A GBS vaccine for pregnant women is under development and is expected to be available in the near future. The perceptions and preferences of pregnant women in China of GBS vaccines has not been investigated, and this study aimed to investigate pregnant women‘s awareness of GBS and their potential preferences for the GBS vaccine. A discrete choice experiment was conducted among pregnant women in hospitals from Shaanxi, Hunan, and Zhejiang provinces located in Western, Central, and Eastern China, respectively. A conditional logit model was used to analyze the data and calculate willingness to pay values and choice probabilities of different GBS vaccine programs. A total of 354 pregnant women were included in the final analysis, 45.8% of whom were willing to receive a GBS vaccine if it were licensed. Vaccine safety was the most important attribute of a future vaccine, while cost was the least important attribute. Compared with no vaccination, pregnant women had a strong preference for future GBS vaccination (ASC = 1.267, p < .001). Pregnant women’s decisions were highly influenced by those of other pregnant women. Improving the safety, efficacy, and vaccination rate of the GBS vaccine in China is of great significance for future GBS vaccine development and vaccination. Compared to other variable options, the cost of a GBS vaccine was of the least importance among pregnant women in mainland China. These findings can inform public health policy decisions related to GBS vaccination in China.

Introduction

Group B streptococcus (GBS) is a leading cause of neonatal death, causing meningitis, sepsis, and pneumonia, which may lead to long-term neurological sequelae, contributing to a large disease burden worldwide.Citation1,Citation2 GBS disease in infants is divided into two types: early-onset GBS (EOGBS), which occurs within the first 7 days of life, and late-onset GBS (LOGBS), which occurs between 7 and 89 days of life.Citation2 Globally, GBS contributes to around 9,700 infant deaths annuallyCitation1 and the overall global incidence is 0.49 per 1,000 live births.Citation2 Our previous national multicenter study found that in China, the incidence of GBS disease was about 0.31 per 1,000 live births.Citation3 The absolute number of Chinese infants suffering from GBS disease is 25,000 (UR 0–59,000), which ranks second in the world, following India.Citation4

The current approach to preventing GBS involves identifying high-risk women (maternal fever during labor ≥38°C, unavoidable premature delivery, preterm premature rupture of membranes (PPROM), rupture of membranes ≥18 hours) during pregnancy and administering antibiotics during labor, also known as intrapartum antibiotic prophylaxis (IAP) use.Citation4 The use of IAP in USA has reduced the incidence of GBS EOD, from 0.37 to 0.23 per 1,000 live births (37.8%),Citation5 and the Perinatal Medicine Branch of Chinese Medical Association has recommended IAP since 2021.Citation6 However, IAP cannot prevent LOGBS, and the use of antibiotics may influence the infant’s bacterial flora, leading to drug resistance, allergy, and other risks.Citation7 Moreover, absence of adequate laboratory testing and identification resources poses a challenge for GBS screening and of implementation of the widespread use of IAP in China’s secondary and primary level healthcare facilities.Citation8

Due to the fact that GBS screening and IAP cannot cover all pregnant women, maternal vaccination against GBS is crucial. The 6-valent GBS vaccine under development, which has been granted breakthrough therapy certification by the Food and Drug Administration, Priority Medicines by the European Medicine Administration,Citation9 is expected to reduce drug resistanceCitation10 and protect newborns from both LOGBS and EOGBS.Citation11,Citation12

It can be challenging for pregnant women to accept GBS vaccines which are offered during pregnancy, and the refusal rate among pregnant women can be as high as 32%.Citation13 Pregnant Chinese women’s knowledge of GBS and their preferences for future GBS vaccination are unknown. Recent studies in the United States and Ireland suggest that pregnant women in countries with different incidence and preventive interventions may have different preferences for GBS vaccination.Citation14 Gaining insights into how various attributes of vaccines influence individual preferences regarding vaccination can provide valuable information to public health authorities.

Discrete Choice Experiments(DCE)have been widely used in the field of vaccination preference research.Citation15 DCE relies on individuals’ personal knowledge and perceptions to assess their preferences,Citation16 considering trade-offs between different options. Compared to other survey methods, DCE is argued to better simulate real-world decision-making processes.Citation17 Many DCE studies of vaccines which benefit children have been conducted by interviewing parents and doctors, and existing DCE vaccine studies include those for human papillomavirus (HPV),Citation18 influenza,Citation19 haemophilus influenzae type b,Citation20 and meningitis.Citation21 The GBS vaccine, which would be administered to mothers during pregnancy, would confers benefits to newborns.Citation12,Citation22

As such, in this study, we applied a DCE to evaluate pregnant Chinese women’s preferences regarding the attributes and characteristics of an upcoming GBS vaccine. By examining these preferences, we aimed to identify the factors that influence their vaccination choices and determine which attributes should be considered for future information and awareness campaigns, and in the integration of the GBS vaccine into the national immunization program.

Methods

We applied the DCE method following the research practice guideline established by the International Society for Pharmacoeconomics and Outcomes Research (ISPOR).Citation23–25

Attributes, levels, and DCE development

In DCE studies on vaccine preference, it is necessary to identify the attributes that have an impact on vaccination preference. A literature review of vaccine-related DCE was conducted using keywords including “discrete choice experiment,” “vaccine,” and “preference,” through Pubmed/Medline, Web of Science, Cochrane, CNKI, and WanFang databases, and nine attributes were extracted from the literature to be included in this study: vaccine efficacy, vaccine safety, out-of-pocket cost, proximity of vaccination location to home, whether the vaccine is imported, vaccine duration of protection, vaccine recommenders, proportion of the pregnant women vaccinated. A single retrieved article explored future GBS vaccination preferences, in both Philadelphia, USA and Dublin, Ireland.Citation14 A review by Marshall et al.Citation26 estimated that 70% of studies use between 3 and 7 attributes, and a review by Marilyn et al.Citation27 found that literature review and focus interviews were the most common methods for identifying attributes.

The final attributes and levels of the survey were determined through online one-on-one semi-structured focus interviews with a stakeholder group consisting of 3 obstetricians, 2 gynecologists, 2 pediatricians, 6 pregnant women, and 11 vaccine developers. We asked respondents to rate the importance of the 9 attributes extracted from the literature, with the most important being 9 and the least important being 1. We summarized the scores of each attribute and selected the 6 attributes with the highest scores for inclusion in the study. Six attributes were selected which were the most important of the 9 discussed with participants: efficacy, safety (Adverse Vaccine Event (AVE)), duration of protection, out-of-pocket cost of single dose, total number of doses, and proportion of pregnant women who have been vaccinated (). The maximum level (or different categories) of cost was determined using the price of the ACYW135 meningococcal polysaccharide conjugate vaccine (CRM197 vector)Citation28 because of their similarities in R&D principles. The level of other attributes was determined by referring to previous DCE studies, the Guiding Principles of the National Medical Products Administration of China on the Issuance of Grading Standards for Adverse Events in Clinical Trials of Vaccines for Prophylactic Use,Citation29 and the ISPOR Task ForceCitation23–25 on DCE.

Table 1. Attributes and levels for GBS vaccine discrete choice experiment.

Our selection of attributes and levels resulted in a total of 729 hypothetical scenarios (calculated by multiplying 3 options for each of the 6 attributes). Additionally, there were 265,356 potential paired choices (calculated using the formula (729 × 728)/2) that could be generated from these scenarios. We used SAS software (version 9.4; Cary, NC) D-optimal algorithm to generate choice sets, and 18 was the minimum number of choice sets to complete a 100% efficient design. To reduce the cognitive burden on respondents, 18 choice sets were divided into two versions, each consisting of 9 unique choices (example listed in ). Within the survey, each set of choice questions was randomly assigned to half of the sample for distribution.

Table 2. An example of choice sets.

Study sample and data collection

Using stratified random sampling, based on the regional divisions outlined in the China Health Statistics Yearbook,Citation30 1 city was selected from each of the eastern (Hangzhou, Zhejiang), western (Xi’an, Shannxi), and central regions (Changsha, Hunan) of China. According to the empirical formula proposed by Johnson and Orme, the number of required samples can be calculated using the equation: n > 500c/ta.Citation31

When only the main effect exists, c represents the maximum level value in the attribute. When the second-order interaction effect between attributes is considered, c represents the maximum number of combinations of any two attributes; t represents the number of questions in the questionnaire; and a represents the number of options in each question (excluding the opt-out). The final sample size was determined to be at least n > 500 * 3 * 3/9 * 2 = 250.

The inclusion criteria for subjects in this study were as follows: pregnant women who go to the hospital for routine prenatal checkups, and willing to undergo a discrete choice experiment. Exclusion criteria for the study included: unwillingness to participate in the preference study, incomplete informed consent, and inability to understand the content of the study. From March to April 2023, the survey was conducted anonymously in quiet fetal monitor rooms in Xi ‘an Fourth Hospital, Xi ‘an International Medical Center, Zhejiang University Maternity Hospital, and Changsha Maternal and Child Health Hospital. The questionnaire contained demographic information, GBS vaccination intention question (whether the pregnant women are willing to receive GBS vaccine), GBS knowledge questions (based on the subjective feelings of pregnant women), relative importance ranking of GBS vaccine attributes, and 9 choice sets per participant. Each choice set required subjects to choose among 2 vaccine programs or 1 opt-out option. In the discrete choice experiment, 2 trained researchers from Xi ‘an Jiaotong University carried computer tablets to the site to complete a one-on-one interview. Researchers introduced GBS, the concept of a GBS vaccine, and the meaning of attributes (see Appendix 1), before they started the interview. In order to control the quality of the study, one trap question (repeated question) was set for each version of the questionnaire, and the quality of the questionnaire was controlled through the consistency of the answers. All data from participants who provided inconsistent responses to trap questions was removed from the study analysis.

Data analyses

EpiData (EpiData Association, Odense, Denmark) was used for double data entry, and except for the price level, which was treated as a continuous variable,Citation32,Citation33 the remaining attributes were encoded using dummy variables. Descriptive analyses were used to examine the demographic characteristics of the participants in the study. To determine the influence of each attribute, a conditional logit model was employed in R (See EquationEquation (1)(1)

(1) ).

The utility () of different GBS vaccination programs is determined by the deterministic utility of 6 observed vaccine attributes (

), along with a random error term (

). The Alternative Specific Constant (ASC) is a randomly determined value that reflects the preference individuals have for vaccination options when compared to the choice of not getting vaccinated (opt-out). Preferences

to

represent the preference co-efficiency of each attribute level compared to the reference level, with the sign of coefficients indicating the positive or negative effect on utility. The goodness of fit of the final model was assessed using the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) and the Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC).

Policy analysis

We assessed the participants’ willingness to pay (WTP) for variations in attribute levels by calculating the ratio between the coefficients of categorical variables and the coefficient associated with the cost of vaccination. To illustrate, when all other attribute levels remained constant, the ratio β1/β11 indicated the parents’ WTP for enhancing vaccine effectiveness from 65% to 85%.Citation33

We performed policy simulations aimed at determining the likelihood of individuals favoring a specific vaccination program with certain characteristics. This estimation was derived by employing the following equation:

represents the likelihood of selecting a specific vaccination strategy (alternative) among various options available,

refers to the measure of overall satisfaction, benefit, or value derived from choosing alternative “i” in the vaccination program, and

represents a combination of both receiving vaccinations and not receiving them.

Results

Socio-demographic characteristics of the respondents

shows the demographics of the study respondents. A total of 420 pregnant women participated in the survey, including 140 from Zhejiang province, 150 from Shaanxi province, and 130 from Hunan Province. Excluding the pregnant women with inconsistent choices in the trap questions, a total of 354 samples were collected (116 from Zhejiang province, 130 from Shaanxi Province, and 108 from Hunan Province). The average age of the respondents was 30.9 (SD = 3.77) years old, the average gestational weeks of the respondents were 35.86 (SD = 2.42) weeks. 99.72% of the respondents were married, 89.83% of them have a bachelor or above degree, and 42.37% of them are enterprise employees. 7.91% of the respondents had an occupation related to health care, 88.7% of them are from urban areas, and 45.76% of the respondents were willing to be vaccinated against GBS (this question was asked prior to the DCE portion of the survey). Only 22.32% of the respondents were very familiar with GBS, and 46.9% of respondents reported having a prior pregnancy. 75.99% of the respondents have an annual household income of more than 100,000 CNY.

Table 3. Demographic characteristics.

Preferences of pregnant women toward GBS vaccination and subgroup analysis

The outcomes of the conditional logit model for two different scenarios are presented in . Model 1 displays the results for the main effects only, while Model 2 includes the main effects along with interaction effects. Significant differences (p < .001) were observed in participants’ preference for GBS vaccination based on vaccine versus no vaccine, minor versus moderate/severe adverse events following vaccination, efficacy of 95% versus 65%, number of doses (1 versus 3), and vaccine coverage of 90% versus 30%. The preference coefficients show that pregnant women prefer GBS vaccines with low risk of adverse events, high efficacy, 1 dose, and high pregnant population coverage. Pregnant women surveyed showed a slight positive preference for the price of GBS vaccine: 0.007/10USD, but this preference was not statistically significant. Compared with no vaccination, pregnant women had a strong preference for future GBS vaccination (coefficient of preference = 1.267, p < .001). The safety of a vaccine (avoiding severe AVE) was the most important attribute (coefficient of preference = −1.707, p < .001), the second most important attribute is the vaccination rate among pregnant women (90%) (coefficient of preference = 0.249, p < .001), while vaccination cost was the least significant attribute (coefficient of preference = 0.007, p = .503).

Table 4. Results of conditional logit model with main effects and interactions.

When considering demographic interactions, it becomes evident that pregnant women from varying household income backgrounds exhibit no difference in their preferences for GBS vaccines. Women with higher levels of education exhibited a greater capacity to endure minor adverse events after receiving immunizations and demonstrated a greater acceptance of receiving multiple doses of the vaccine compared to those with lower levels of education. Additionally, more educated women expressed a dispreference regarding the increased cost associated with the vaccine.

Policy analysis

Trade-offs among attributes

The marginal willingness to pay (WTP) values for each attribute associated with GBS vaccination are presented in . Pregnant women exhibited a pronounced inclination toward greater vaccine efficacy and demonstrated a willingness to allocate 257.26 USD for a GBS vaccine with 95% efficacy as opposed to 65%. Moreover, pregnant women indicated a monetary valuation of 2,293.71 USD in order to mitigate the occurrence of severe adverse drug events (AVEs).

Table 5. Willingness to pay.

In terms of the relative importance, the most crucial attribute is vaccine efficacy, with a score of 27.29%, whereas total number of doses ranked as the least important attribute at 9.94%. There were no notable disparities in the relative importance of vaccine attributes among women residing in different regions of China. The results also indicate that the preferences observed in the direct relative importance ranking are distinct from those observed in the DCE, implying a disparity between the two methods in terms of exhibited preferences.

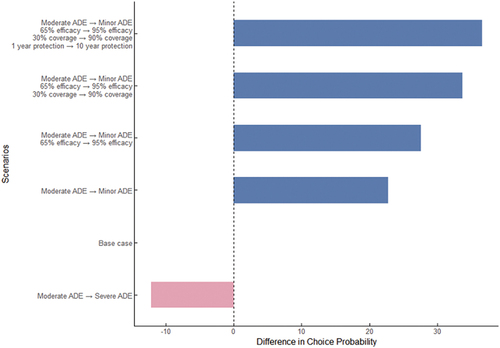

Choice probability of vaccine program

The base case vaccine option has Moderate AVE, costs 31.16 USD and has an efficacy of 65%. It provides protection for 1 year with a single dose and has a coverage rate of 30%. The choice probability for this vaccine is 27.8%. In , we analyze the change in choice probability compared to the base case when modifying vaccine attributes. When the vaccine’s AVE changes from moderate to minor, the choice probability increases by 22.8%, while increasing efficacy from 65% to 95% leads to a 4.8% increase in choice probability. For the vaccination programs with the following attributes: minor AVE, 31.16 USD, 95% efficacy, 10-year protection, 1 dose, and 90% coverage, the choice probability was found to be 64.4%.

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this research represents the inaugural attempt in mainland China to examine pregnant women’s preferences regarding possible GBS vaccination through DCE methodology. Although a GBS vaccine is not yet available on the market, substantial progress has been made in its research and development. It is crucial to evaluate the preferences for GBS vaccination among pregnant women to optimize vaccine marketing strategies and vaccination campaigns, and thereby safeguarding newborns against GBS infection.

Our primary findings reveal that the most critical factor considered by pregnant women in mainland China was the vaccine’s safety, specifically in preventing severe adverse effects (AVE), the cost of vaccination was the attribute with the least impact on their decision-making, and pregnant women residing in mainland China exhibit a preference for a GBS vaccines that possess the following attributes: minor risk of adverse events, high efficacy, 1 dose, and high pregnant population coverage. In previous studies, respondents have shown a negative preference for vaccine price increases.Citation32,Citation34,Citation35 In our study, however, the coefficient of preference for vaccine price is positive, which means that pregnant women are willing to take the vaccine at a higher price (though this relationship was not statistically significant), which is consistent with a previous study of influenza vaccine on the elderly.Citation36 The reason for this finding may be that pregnant women and the elderly are more concerned about the benefits and risks of vaccination and are relatively insensitive to price, but more research is needed to confirm this. Notably, in our study we found that pregnant women’s decisions were highly influenced by those of other pregnant women. When other pregnant women decided to get a GBS vaccine (assuming 90% coverage), pregnant women showed a clear preference for receiving vaccine. This may be explained by the fact that pregnant women believe that vaccines with high coverage tend to reflect public confidence in the good quality of vaccines, which is consistent with previous studies.Citation37,Citation38 Furthermore, the results suggest that there are variations in preferences regarding GBS vaccination among pregnant women with different levels of education, with more highly educated women preferring minor adverse events following immunization and demonstrated a greater acceptance of receiving multiple doses. The vaccination intention rate among the cohort of pregnant women in this study was approximately 45.76%, which is comparatively low compared with the rates observed in developed countries like the United States (68%),Citation39 Australia (74%),Citation13 and the United Kingdom (68.4%).Citation40,Citation41 We also found that the results of the DCE were different from relative importance ranking: coverage of GBS vaccine is considered to be the least important attribute in questions of relative importance ranking, but in DCE results, whether other pregnant women have received GBS vaccine is considered to be the second important attribute. These insights are valuable in informing the development and introduction of future GBS vaccines in China. By considering the preferences and priorities of pregnant women, researchers and policymakers can focus on developing vaccines that meet these criteria and develop vaccination campaigns which highlight key attributes. This information can aid in guiding public health initiatives and policy decisions related to GBS vaccination in China, ultimately contributing to the reduction of GBS-related complications and improving maternal and neonatal health outcomes.

This study had several notable strengths. First, it involved conducting face-to-face interviews by trained researchers with pregnant women. When the interviewees are unable to comprehend the DCE questions, the researchers can clarify the questions. Second, the inclusion of an opt-out option within the choice set allowed participants to refrain from making a challenging decision, thereby enhancing the validity of their responses. The third strength was the incorporation of repeated “trap questions” within the choice set, enabling the identification of pregnant women who may not have fully grasped the purpose of the DCE design, with that data being removed from analysis. However, it is important to acknowledge that this approach resulted in a reduction in the sample size.

Our study had some limitations. Screening for GBS in China is more well established in tertiary hospitals, whereas secondary and primary healthcare facilities may face limitations due to inadequate laboratory resources.Citation8 Consequently, pregnant women who receive obstetric care in tertiary hospitals are more likely to be informed about the risks associated with GBS. As a result, we specifically chose pregnant women from tertiary hospitals in major cities as our sample, and this sample may not accurately represent the preferences of pregnant women residing in rural areas. As well, since a GBS vaccine has not yet been approved, our study was conducted with limited information regarding potential vaccine adverse events. Furthermore, since participants may opt out of answering some questions, not only to genuinely express their real-life preferences but also to evade challenging trade-offs at attribute levels, the accuracy of parameter estimates may have been impacted.Citation42,Citation43

Conclusions

In conclusion, the findings of this study indicate that pregnant women are more inclined toward receiving the GBS vaccination compared to opting for no vaccination, and they strongly favor a future GBS vaccine with certain key attributes: a low risk of adverse events, high efficacy, 1 dose administration, and the adoption of the vaccine by a significant portion of the pregnant population. Women with a higher educational attainment demonstrated an increased tolerance in minor adverse events following immunization and exhibited a greater willingness to receive multiple doses of the GBS vaccine, in comparison to pregnant women with lower levels of education. Moreover, pregnant women with higher educational backgrounds expressed an elevated level of apprehension regarding the increased cost of the vaccine.

Author contributions

W.J, J.D, and Y.F conceived the original idea and design the study. J.D conducted the DCE design, DCE interview, data analysis and manuscript drafting. H.Z helped with DCE interview. Y.Z, J.C and D.M provided critical review and edits. W.J obtained the funding. All authors have review and approved the final manuscript.

Ethical approval

As this study is a cross-sectional survey which does not involve patient privacy, poses no harm to patient well-being, and ensures complete anonymity, it has been exempted from ethical review. Informed consent was obtained from the participants of this study.

Appendix.docx

Download MS Word (14.4 KB)Acknowledgments

We thank the pregnant women and researchers from Xi ‘an Fourth Hospital, Xi ‘an International Medical Center, Zhejiang University Maternity Hospital, and Changsha Maternal and Child Health Hospital for their cooperation and support in this study.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

Datasets are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Supplementary data

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed on the publisher’s website at https://doi.org/10.1080/21645515.2023.2281713.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Gonçalves BP, Procter SR, Paul P, Chandna J, Lewin A, Seedat F, Koukounari A, Dangor Z, Leahy S, Santhanam S, et al. Group B Streptococcus infection during pregnancy and infancy: estimates of regional and global burden. Lancet Glob Health. 2022;10(6):e807–10. doi:10.1016/S2214-109X(22)00093-6.

- Madrid L, Seale AC, Kohli-Lynch M, Edmond KM, Lawn JE, Heath PT, Madhi SA, Baker CJ, Bartlett L, Cutland C, et al. Infant Group B Streptococcal disease incidence and serotypes worldwide: systematic review and meta-analyses. Clin Infect Dis. 2017;65(suppl_2):S160–S72. doi:10.1093/cid/cix656.

- Ji W, Liu H, Madhi SA, Cunnington M, Zhang Z, Dangor Z, Zhou H, Mu X, Jin Z, Wang A, et al. Clinical and molecular epidemiology of invasive Group B Streptococcus disease among infants, China. Emerg Infect Dis. 2019;25(11):2021–30. doi:10.3201/eid2511.181647.

- Seale AC, Bianchi-Jassir F, Russell NJ, Kohli-Lynch M, Tann CJ, Hall J, Madrid L, Blencowe H, Cousens S, Baker CJ, et al. Estimates of the burden of Group B Streptococcal disease worldwide for pregnant women, stillbirths, and children. Clin Infect Dis. 2017;65(suppl_2):S200–S19. doi:10.1093/cid/cix664.

- Nanduri SA, Petit S, Smelser C, Apostol M, Alden NB, Harrison LH, Lynfield R, Vagnone PS, Burzlaff K, Spina NL, et al. Epidemiology of invasive early-onset and late-onset Group B Streptococcal disease in the United States, 2006 to 2015: multistate laboratory and population-based surveillance. JAMA Pediatr. 2019;173(3):224–33. doi:10.1001/jamapediatrics.2018.4826.

- Chinese Medical Association. Chinese experts consensus on prevention of perinatal Group B Streptococcal disease. Chin J Perinat Med. 2021;24:561–6. (In Chinese).

- Azad MB, Konya T, Persaud RR, Guttman DS, Chari RS, Field CJ, Sears MR, Mandhane PJ, Turvey SE, Subbarao P, et al. Impact of maternal intrapartum antibiotics, method of birth and breastfeeding on gut microbiota during the first year of life: a prospective cohort study. Bjog. 2016;123(6):983–93. doi:10.1111/1471-0528.13601.

- Le Doare K, O’Driscoll M, Turner K, Seedat F, Russell NJ, Seale AC, Heath PT, Lawn JE, Baker CJ, Bartlett L, et al. Intrapartum antibiotic chemoprophylaxis policies for the prevention of Group B Streptococcal disease worldwide: systematic review. Clin Infect Dis. 2017;65(suppl_2):S143–s51. doi:10.1093/cid/cix654.

- Pfizer. FDA grants breakthrough therapy designation to Pfizer’s Group B Streptococcus vaccine candidate to help prevent infection in infants via immunization of pregnant women |Business wire. [Online]. [assessed 2022 Sep 25].

- Oliveira LMA, Simões LC, Costa NS, Zadoks RN, Pinto TCA. The landscape of antimicrobial resistance in the neonatal and multi-host pathogen Group B Streptococcus: review from a one health perspective. Front Microbiol. 2022;13:943413. doi:10.3389/fmicb.2022.943413.

- Carreras-Abad C, Ramkhelawon L, Heath PT, Le Doare K. A vaccine against Group B Streptococcus: recent advances. Infect Drug Resist. 2020;13:1263–72. doi:10.2147/IDR.S203454.

- Absalon J, Segall N, Block SL, Center KJ, Scully IL, Giardina PC, Peterson J, Watson WJ, Gruber WC, Jansen KU, et al. Safety and immunogenicity of a novel hexavalent Group B Streptococcus conjugate vaccine in healthy non-pregnant adults: a phase 1/2 randomised placebo-controlled observer-blinded dose-escalation trial. Lancet Infect Dis. 2021;21(2):263–74. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30478-3.

- Giles ML, Buttery J, Davey MA, Wallace E. Pregnant women’s knowledge and attitude to maternal vaccination including Group B Streptococcus and respiratory syncytial virus vaccines. Vaccine. 2019;37(44):6743–9. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2019.08.084.

- Geoghegan S, Faerber J, Stephens L, Gillan H, Drew RJ, Eogan M, Feemster KA, Butler KM. Preparing for Group B Streptococcus vaccine. Attitudes of pregnant women in two countries. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2023;19(1):2195331. doi:10.1080/21645515.2023.2195331.

- Michaels-Igbokwe C, MacDonald S, Currie GR. Individual preferences for child and adolescent vaccine attributes: a systematic review of the stated preference literature. Patient. 2017;10(6):687–700. doi:10.1007/s40271-017-0244-x.

- EW de Bekker-Grob, Ryan M, Gerard K. Discrete choice experiments in health economics: a review of the literature. Health Econ. 2012;21(2):145–72. doi:10.1002/hec.1697.

- Quaife M, Terris-Prestholt F, Di Tanna GL, Vickerman P. How well do discrete choice experiments predict health choices? A systematic review and meta-analysis of external validity. Eur J Health Econ. 2018;19(8):1053–66. doi:10.1007/s10198-018-0954-6.

- Hofman R, de Bekker-Grob EW, Raat H, Helmerhorst TJ, van Ballegooijen M, Korfage IJ. Parents’ preferences for vaccinating daughters against human papillomavirus in the Netherlands: a discrete choice experiment. BMC Public Health. 2014;14(1):454. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-14-454.

- Shono A, Kondo M. Parents’ preferences for seasonal influenza vaccine for their children in Japan. Vaccine. 2014;32(39):5071–6. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2014.07.002.

- Wang X, Feng Y,Zhang Q, Ye L, Cao M, Liu P, Liu S, Li S, Zhang J. Parental preference for haemophilus influenzae type b vaccination in Zhejiang Province China: a discrete choice experiment. Front Public Health. 2022;10:967693. doi:10.3389/fpubh.2022.967693.

- Poulos C, Reed Johnson F, Krishnarajah G, Anonychuk A,Misurski D. Pediatricians’ preferences for infant meningococcal vaccination. Value Health. 2015;18(1):67–77. doi:10.1016/j.jval.2014.10.010.

- Madhi SA, Anderson AS, Absalon J, Radley D, Simon R, Jongihlati B, Strehlau R, van Niekerk AM, Izu A, Naidoo N, et al. Potential for maternally administered vaccine for infant Group B Streptococcus. N Engl J Med. 2023;389(3):215–27. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2116045.

- Hauber AB, González JM, Groothuis-Oudshoorn CG, Prior T, Marshall DA, Cunningham C, IJzerman MJ, Bridges JFP. Statistical methods for the analysis of discrete choice experiments: a report of the ISPOR conjoint analysis good research practices task force. Value Health. 2016;19(4):300–15. doi:10.1016/j.jval.2016.04.004.

- Bridges JF, Hauber AB, Marshall D, Lloyd A, Prosser LA, Regier DA, Johnson FR, Mauskopf J. Conjoint analysis applications in health—a checklist: a report of the ispor good research practices for conjoint analysis task force. Value Health. 2011;14(4):403–13. doi:10.1016/j.jval.2010.11.013.

- Reed Johnson F, Lancsar E, Marshall D, Kilambi V, Mühlbacher A, Regier DA, Bresnahan BW, Kanninen B, Bridges JFP. Constructing experimental designs for discrete-choice experiments: report of the ISPOR conjoint analysis experimental design good research practices task force. Value Health. 2013;16(1):3–13. doi:10.1016/j.jval.2012.08.2223.

- Marshall D, Bridges JF, Hauber B, Cameron R, Donnalley L, Fyie K, Johnson FR. Conjoint analysis applications in health – how are studies being designed and reported? Patient. 2010;3(4):249–56. doi:10.2165/11539650-000000000-00000.

- Diks ME, Hiligsmann M, van der Putten IM. Vaccine preferences driving vaccine-decision making of different target groups: a systematic review of choice-based experiments. BMC Infect Dis. 2021;21(1):879. doi:10.1186/s12879-021-06398-9.

- yaozh data. 23-valent pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine procurement price. 2022.

- Guiding principles of the national medical products administration of China on the issuance of grading standards for adverse events in clinical trials of vaccines for prophylactic use. National Medical Products Administration; 2019.

- China Health Statistical Yearbook 2021. National health commission of People’s Republic of China. 2021.

- Johnson R, Orme B. Getting the most from CBC. Sawtooth Software Research Paper. 2003.

- Zhu S, Chang J, Hayat K, Li P, Ji W, Fang Y. Parental preferences for HPV vaccination in junior middle school girls in China: a discrete choice experiment. Vaccine. 2020;38(52):8310–7. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2020.11.020.

- Sargazi N, Takian A, Yaseri M, Daroudi R, Ghanbari Motlagh A, Nahvijou A, Zendehdel K. Mothers’ preferences and willingness-to-pay for human papillomavirus vaccines in Iran: a discrete choice experiment study. Prev Med Rep. 2021;23:101438. doi:10.1016/j.pmedr.2021.101438.

- Balogun FM, Omotade OO, Svensson M. Stated preferences for human papillomavirus vaccination for adolescents in selected communities in Ibadan Southwest Nigeria: a discrete choice experiment. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2022;18(6):2124091. doi:10.1080/21645515.2022.2124091.

- Patterson BJ, Myers K, Stewart A, Mange B, Hillson EM, Poulos C. Preferences for herpes zoster vaccination among adults aged 50 years and older in the United States: results from a discrete choice experiment. Expert Rev Vaccines. 2021;20(6):729–41. doi:10.1080/14760584.2021.1910502.

- Jiang M, Li P, Yao X, Hayat K, Gong Y, Zhu S, Peng J, Shi X, Pu Z, Huang Y, et al. Preference of influenza vaccination among the elderly population in Shaanxi province China. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2021;17(9):3119–25. doi:10.1080/21645515.2021.1913029.

- Hoogink J, Verelst F, Kessels R, van Hoek AJ, Timen A Willem L, Beutels P, Wallinga J, de Wit GA. Preferential differences in vaccination decision-making for oneself or one’s child in the Netherlands: a discrete choice experiment. BMC Public Health. 2020;20(1):828. doi:10.1186/s12889-020-08844-w.

- Verelst F, Kessels R, Delva W, Beutels P, Willem L. Drivers of vaccine decision-making in South Africa: a discrete choice experiment. Vaccine. 2019;37(15):2079–89. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2019.02.056.

- Dempsey AF, Pyrzanowski J, Donnelly M, Brewer S, Barnard J, Beaty BL, Mazzoni S, O’Leary ST. Acceptability of a hypothetical Group B strep vaccine among pregnant and recently delivered women. Vaccine. 2014;32(21):2463–8. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2014.02.089.

- McQuaid F, Jones C, Stevens Z, Plumb J, Hughes R, Bedford H, et al. Factors influencing women’s attitudes towards antenatal vaccines Group B Streptococcus and clinical trial participation in pregnancy: an online survey. BMJ Open. 2016;6:e010790. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2015-010790.

- McQuaid F, Jones C, Stevens Z, Meddaugh G, O’Sullivan C, Donaldson B, Hughes R, Ford C, Finn A, Faust SN, et al. Antenatal vaccination against Group B Streptococcus: attitudes of pregnant women and healthcare professionals in the UK towards participation in clinical trials and routine implementation. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2018;97(3):330–40. doi:10.1111/aogs.13288.

- Campbell D, Erdem S. Including opt-out options in discrete choice experiments: issues to consider. Patient. 2019;12(1):1–14. doi:10.1007/s40271-018-0324-6.

- Veldwijk J, Lambooij MS, EW de Bekker-Grob, Smit HA, de Wit GA. The effect of including an opt-out option in discrete choice experiments. PLoS One. 2014;9(11):e111805. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0111805.

Appendix

Before DCE begins, we showed the interviewees the specific meanings of the different attributes in DCE.

Table1. Attributes affecting the vaccination of pregnant women with Group B Streptococcus vaccine and their definitions.