ABSTRACT

University students, who face an elevated risk of influenza due to close living quarters and frequent social interactions, often exhibit low vaccine uptake rates. This issue is particularly pronounced among Chinese students, who encounter unique barriers related to awareness and access, emphasizing the need for heightened attention to this problem within this demographic. This cross-sectional study conducted in May-June 2022 involved 1,006 participants (404 in the UK, 602 in Mainland China) and aimed to explore and compare the factors influencing influenza vaccine acceptance and intentions between Chinese university students residing in the UK (C-UK) and Mainland China (C-M). The study employed a self-administered questionnaire based on the Theoretical Domains Framework and Capability Opportunity Motivation-Behavior model. Results revealed that approximately 46.8% of C-UK students received the influenza vaccine in the past year, compared to 32.9% of C-M students. More than half in both groups (C-UK: 54.5%, C-M: 58.1%) had no plans for vaccination in the upcoming year. Knowledge, belief about consequences, and reinforcement significantly influenced previous vaccine acceptance and intention in both student groups. Barriers to vaccination behavior included insufficient knowledge about the influenza vaccine and its accessibility and the distance to the vaccine center. Enablers included the vaccination behavior of individuals within their social circles, motivation to protect others, and concerns regarding difficulties in accessing medical resources during the COVID-19 pandemic. The findings of this study offer valuable insights for evidence-based intervention design, providing evidence for healthcare professionals, policymakers, and educators working to enhance vaccination rates within this specific demographic.

Introduction

China has a substantial population at high risk for seasonal influenza, resulting in a significant public health burden.Citation1 Each year, seasonal influenza was estimated to result in approximately 88,000 excess respiratory deaths from 2010 to 2015 in China.Citation2 This burden encompasses a range of social and economic implications, including absenteeism from work or school, elevated medical expenses, limited mobility due to symptoms and contagiousness, and even job loss.Citation3 Vaccination is the established method for protecting susceptible individuals from severe symptoms and mitigating the risk of disease transmission.Citation4–6 However, the vaccine coverage rate in mainland China remains remarkably low.Citation7–9 Based on a systematic review spanning from 2005 to 2017, the pooled vaccination rate among the general population was found to be merely 9.4%.Citation8 Another review found that this rate was 16.74% until 2022.Citation10 These numbers are much lower than the targeted threshold of 40%, as identified by modeling studies, which is deemed crucial for effective prevention and control of the influenza epidemic at a national scale.Citation11,Citation12

Despite the high likelihood of contracting and transmitting seasonal influenza, young adults – particularly university students – are often overlooked in previous research that largely focuses on vulnerable populations such as children, the elderly, and those with chronic disease.Citation8,Citation13 This is despite the fact that their high-density living conditions and frequent social interactions which make them particularly susceptible.Citation14,Citation15 University students have been found to have a high risk of experiencing severe symptoms and death, yet they tend to underestimate the severity of influenza.Citation16,Citation17 Influenza infections among them can lead to significant absenteeism, affecting their academic performance.Citation3,Citation18 Despite these risks, the vaccination rate among university students remains suboptimal globally, particularly in comparison to other vulnerable groups.Citation19

Numerous empirical studies have investigated factors influencing university students’ decisions to receive vaccines,Citation20–24 primarily conducted in the United States.Citation19 However, limited data are available for Chinese domestic students or those with a Chinese cultural background studying abroad outside the US, despite the growing number of Chinese students choosing the UK as their study destination.Citation25 The influence of race or ethnicity on vaccine intention among university students has been identified as a significant factor,Citation26–28 underlining the necessity for focused research that specifically explores the perspectives of Chinese students. Moreover, prior research on university students has predominantly concentrated on intrinsic or psychological, such as risk perception and protective elements linked to vaccination behavior, while often overlooking the external factors that influence decision-making.Citation29,Citation30 Given mainland China’s large population and centralized governance structure, external factors, such as policy, may significantly impact vaccine intentions. Therefore, gaining a comprehensive understanding of vaccination behavior among university students is vital for developing effective behavioral intervention strategies and guiding future research.Citation31

To address these gaps, this study aims to investigate the factors influencing influenza vaccination intention and acceptance among university students studying in Mainland China. The mainland Chinese students studying in the UK have been chosen as the comparative group for several reasons. Firstly, it has the largest number of Chinese university students studying abroad, providing a representative sample of this population.Citation32 Secondly, the UK’s abundant supply of influenza vaccines allows for measuring actual vaccine behavior and avoids potential biases caused by limited vaccine availability in mainland China.Citation33 Lastly, comparing Chinese students in the UK with those in mainland China allows for examining the influence of cultural and environmental backgrounds on vaccination decisions. Thus, this study will compare Chinese students studying in mainland China with those studying in the UK as two comparative groups (referred to as “C-M” and “C-UK” students, respectively, for simplicity).

Methods

Context and procedure

The context of this study delves into the distinct settings of influenza vaccination among Chinese university students in Mainland China and the UK. It is important to highlight that university students do not qualify as eligible individuals for free influenza vaccines in both countries.Citation2,Citation34 There are differences in prices and access to the vaccine. In the UK, the influenza vaccine costs approximately GBP 14.5 ($17.6). Students can access influenza vaccines through local vaccine centers or pharmacies, such as Boots or Superdrug.Citation34 In China, the influenza vaccine costs around CNY 150 ($21.4), and students can only obtain it through clinics and hospitals.Citation2 The study was conducted from May to June 2022. The timeline for this study was deliberately selected outside the influenza season. This decision aimed to assess the acceptance rate for the previous season and the intention for the upcoming one. Notably, Mainland China was operating under a zero-COVID-19 policy during the study period.Citation35 This policy involved preventive measures including mandatory face masks and lockdowns. On the contrary, there are no COVID-19 restrictions in the UK during the study period as the related measures had been lifted since February 2022.Citation36

The research protocol for this study received approval from the UCL Ethics Committee before initiation (ref no. 21647/001). The study adopted a cross-sectional research design, involving the administration of two surveys among Chinese university students in Mainland China and the UK separately. The questionnaires were developed and administered online using the Chinese survey platform Wenjuanxing.com. The introduction pages conveyed information regarding the research objectives and approximate survey duration, mentioning the voluntary nature of participation. Participants indicated their consent by clicking “Continue,” agreeing that they had read and approved all conditions outlined in the informed consent document, including their rights, benefits, and potential risks associated with their participation.

Participants

The study targeted Chinese university students aged 18 and above studying in the UK or Mainland China. The inclusion criteria for the “Chinese” population specify that participants should be born in China, and both the participant and their parents should hold Chinese nationality at the time of survey completion. A combination of convenience and purposive sampling methods was employed to recruit eligible participants, aiming to enhance survey response rates. The initial survey link was disseminated through the university WeChat accounts of University College London located in London, UK, and Southeast University located in Jiangsu province, China. It was also shared in student group chats in both the UK and China where the researchers have access. Snowball sampling was initiated by encouraging participants who completed the survey to share it solely within their class group chats. To ensure eligibility, participants were asked to report their university name and year of study. Additionally, participants were explicitly requested not to share the survey link beyond their immediate social circles. Prior to inclusion, participants were screened for eligibility based on their place of study and year of birth.

Measurements

The survey instruments were inspired by the Theoretical Domains Framework (TDF), which incorporates 33 behavior change theories, and the adapted “Capability, Opportunity, and Motivation-Behaviour Model” for the vaccination behavior (COM-B).Citation37–40 These models have been successfully applied in previous studies examining intentions to receive vaccines for COVID-19 and HPV.Citation41,Citation42 An initial version of the questionnaire was pilot-tested among a small sample of participants using convenience sampling, resulting in 51 responses and qualitative feedback. Based on the feedback, the questionnaire was refined by rewording and clarifying ambiguous questions to improve readability and comprehensibility. The final version of the questionnaire comprised 36 items covering 7 TDF domains (see Supplementary Material 1). The questionnaire structure and its relationship with the COM-B and TDF domains are presented in . Participants were asked to indicate their level of agreement with statements on a five-point Likert scale, ranging from “strongly agree” to “strongly disagree.” The survey began with sociodemographic questions to capture sample characteristics, including age, gender, education, self-reported health status, vaccine history, and the source of vaccine information. Previous vaccine acceptance, or historical vaccine acceptance, was measured through three option questions with “never”, “a year ago” and “within a year”. Participants’ intention to receive the influenza vaccine was measured using two identical questions with a five-point Likert scale, ranging from “very likely” to “impossible” assessing their likelihood of getting the vaccine within the next 6 months. To mitigate potential order effects, the two questions were placed separately at the beginning and end of the questionnaire.Citation43

Data analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to calculate frequencies and percentages for demographic characteristics. The Shapiro-Wilk tests have been performed to verify the data normality. Independent t-tests were employed for continuous outcomes, specifically age differences, between the two groups. Pearson’s Chi-square test was conducted to examine differences in other categorical outcomes between the two groups. The paired Wilcoxon Sign Rank test was employed to assess differences between vaccine intention scores recorded at the beginning and end of the survey. Due to the skewness, a series of Mann-Whitney tests were conducted to examine the difference in vaccine acceptance and intention between the C-M and C-UK student groups. Independent T-tests were used to analyze group differences in response to each factor question.Citation44 Scores for each TDF domain were derived by calculating the mean score of corresponding items. Subsequently, binary logistic regressions were performed separately for the two groups to identify potential factors associated with vaccine acceptance (either “yes” or “no”) and intention, adjusting for demographic differences. The intention scores were measured by taking the mean of the beginning and end questions. These scores were then coded as either “very low to medium willingness” (≤2.5) or “high to very high willingness” (>2.5). Statistical analysis was carried out using R 4.2.1,Citation45 the MASSCitation46 and the LikertCitation47 packages. A significance level of 0.05 was established for all analyses, indicating statistical significance at p < 0.05.

Results

Sample description

Sociodemographic characteristics

A total of 523 C-M students and 614 C-UK students completed the survey. After data cleaning, which involved removing participants based on country, age (>18), and response time (>100 seconds), 119 (22.7%) participants were excluded from the C-M sample, and 12 (2.0%) participants were excluded from the C-UK sample. This resulted in 404 participants for analysis in the C-M group and 602 in the C-UK group.

The mean age of the participants was 22.7 years (range: 18–43). shows that nearly three-fourths of the included college students were female in both samples. The majority of C-UK students were pursuing master’s degrees (73%), contributing to a significantly higher mean age in C-UK compared to C-M, where most students were pursuing bachelor’s degrees (83%). There was a significantly higher proportion of students studying health-related majors in the C-M sample compared to the C-UK sample (42% vs. 4.5%, respectively). The top three cities where the universities were located were “London, Coventry, and Edinburgh” for the C-UK sample and “Nanjing, Suzhou, and Guiyang” for the C-M sample. Statistical tests revealed significant differences between the two samples regarding age, degree, and major.

Table 1. Sociodemographic characteristics.

Regarding health-related categories, significant differences were observed between the C-M and C-UK samples in the frequency of having cold-like symptoms and self-reported health conditions. C-M students generally reported lower health scores and a lower frequency of having cold-like symptoms within the last three months compared to C-UK students. Details can be found in .

Influenza vaccine acceptance and intention

displays the influenza vaccine acceptance and intention of the two samples, revealing significant differences across all measured categories. Approximately 46.8% of C-UK students reported receiving the influenza vaccine within the past year, whereas only 32.9% of C-M students reported the same. More than half of the students in both samples indicated that they had no plans to receive the influenza vaccine (C-UK: 54.5%, C-M: 58.1%). Significant differences were observed between the two samples in terms of vaccination intention measured at the beginning and end of the surveys. Paired Wilcoxon tests showed that intention scores measured at the end were significantly higher than those measured at the beginning for the total sample and the two sub-groups (C-UK, C-M).

Table 2. Influenza vaccine history and intention by groups.

COM-B model and TDF domain

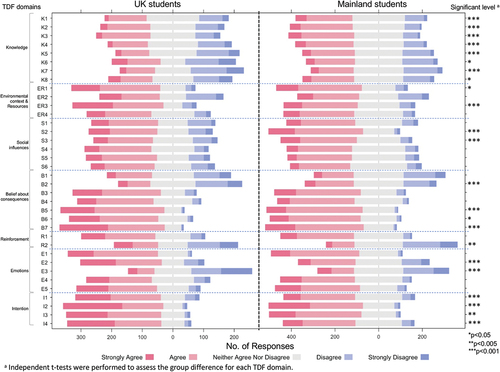

All participants were queried about the factors influencing their decision to receive the influenza vaccination. Self-reported barriers were categorized within the seven domains of the TDF framework. presents the Likert-scale percentages for each question, along with group differences tested by the T-test. illustrates the question indices, and Supplementary Materials 2 and 3 provide additional statistical details. Descriptive results for each COM-B component are outlined below. The figures cited in the subsequent sections are calculated by aggregating the percentages of “disagree” and “Strongly disagree” for negative statements, or “agree” and “Strongly agree” for positive statements.

Figure 2. Likert chart displaying questionnaire responses on factors influencing influenza vaccine decisions with group differences.

Capability

In the knowledge domain, over one-third of C-UK students reported being unclear about K5 (34.41% unsure who needs the vaccine), K6 (40.59% unsure where and how to get the vaccine in the UK), and K7 (42.57% unsure about the side effects of the influenza vaccine). In contrast, C-M students generally demonstrated better knowledge across all items than C-UK students. However, both C-M and C-UK students showed a lack of knowledge on items K6 and K7, with 26.58% and 29.24% of C-M students also reporting unsure on these topics. Statistics reveal that both C-M and C-UK students have the best knowledge regarding K2 (how to prevent and treat influenza) and K3 (influenza transmission routes and infectivity intensity), with over 40% of both samples selecting “agree” or “strongly agree.”

Opportunity

In the environmental context and resources domain, ER2 (distance to vaccination centers) was reported as a common major barrier in both samples, with 29.95% and 23.09% of C-UK and C-M students, respectively, acknowledging it as a problem. A significant difference was found in ER3 (affordability) between the two samples, with 73.27% of C-UK students reporting they could afford the cost of the influenza vaccine compared to only 56.15% among C-M students.

In the social influence domain, the proportion of C-M students who would follow S2 (healthcare workers’ recommendations) and S3 (government and university promotions) was significantly larger than that of C-UK students. Conversely, C-UK students heavily relied on online information such as S4 (websites) and S6 (social media), with 53.71% and 51.24%, respectively, compared to C-M students (49.50% and 45.52%).

Motivation

Regarding the beliefs about consequences domain, nearly one-third of both samples acknowledge the potential severity of influenza disease (B1). A significantly higher proportion among C-M preferred natural immunity (B2) compared to C-UK, with 37.04% vs. 25.73%, respectively. Factors such as B5 (“trusting influenza vaccine in reducing the risk of infection and having severe symptoms”) and B7 (“motivation to achieve herd immunity and protect the vulnerable”) were identified as enablers for more than half of the participants in receiving the influenza vaccine.

Significant differences were found in all items in the intention domain between the two samples. Although the majority of both groups showed a strong preference for a free vaccine (I2) and a shorter waiting time (I4), C-M students expressed less intention to pay (I1) for the vaccine and spend time accessing it (I3), with 54.32% and 70.10%, respectively, compared to C-UK students (68.81% and 76.49%).

Factors associated with the influenza vaccine uptake intentions

After controlling for sociodemographic characteristics, logistic regression analysis () revealed that knowledge, belief about consequences, and reinforcement domains were significantly associated with both previous vaccine acceptance and future vaccination intention among all participants. On the other hand, environmental context and resources domain (including time, distance of vaccine center, affordability), social influences domain, and emotion domain were only significantly associated with vaccination intention. Although there was a significant association between vaccine history and the C-UK and C-M students, there was no significant difference in their intentions. Overall, C-UK students demonstrated higher previous vaccine acceptance but relatively lower intention to be vaccinated within the following year. The study found that the intention score within the TDF domains was not a significant influencing factor for actual vaccination intention among university students. C-UK students with higher knowledge scores (aOR = 1.43, 95% CI [1.05–1.95], p = .022), higher emotion scores (aOR = 1.66, 95% CI [1.04–2.66], p = .035), higher reinforcement scores (aOR = 1.80, 95% CI [1.31–2.47], p < .001), and lower belief about consequences scores (aOR = 0.43, 95% CI [0.25–0.72], p = .001) exhibited a greater intention to receive the vaccination. C-M students with higher social influence scores (aOR = 1.79, 95% CI [1.11–2.88], p = .017), higher environmental context and resource scores (aOR = 1.44, 95% CI [1–20.07], p = .049), higher reinforcement scores (aOR = 1.53, 95% CI [1.08–2.17], p = .018), and lower belief about consequences scores (aOR = 0.29, 95% CI [0.16–0.52], p < .001) exhibited a greater intention to receive the influenza vaccination. Only two TDF domains, belief about consequences and intention, were found to negatively affect influenza vaccine intention among C-UK (aOR = 0.43 and 0.97, respectively) and C-M students (aOR = 0.29 and 0.99, respectively) and were also negatively correlated with their previous vaccine acceptance (C-UK: aOR = 0.68 and 0.94, respectively; C-M: aOR = 0.54 and 0.80, respectively).

Table 3. Factors associated with the influenza vaccination behavior of the study population.

Discussion

The findings of this study shed light on the factors influencing influenza vaccine acceptance and intention among Chinese university students studying in the UK (C-UK) and Mainland China (C-M).

One notable finding is the significance of knowledge on influenza disease and influenza vaccine, as the primary barrier, has a great impact on influencing both previous vaccine acceptance in the past and future vaccination intention among both student groups, especially for C-UK students. These findings support previous research indicating insufficient education and awareness campaigns regarding influenza vaccines in the Chinese population.Citation8,Citation13,Citation48 This study adds that Chinese university students are generally unaware of the importance of vaccination, its potential benefits, and where to access the vaccine. Additionally, the government and health authorities may have limited motivation to promote influenza vaccines, as mentioned earlier.Citation13,Citation49 C-UK students may face additional obstacles in receiving information on influenza vaccines due to unfamiliar surroundings and language barriers.Citation50

Accessibility to influenza vaccine centers also emerged as a significant barrier, particularly in areas with scarce or distant vaccine centers, which can deter university students from intending to receive the influenza vaccine. It indicates that convenient access to vaccines is crucial for increasing vaccine uptake rates among university students, as evidenced by a previous study.Citation16 Efforts should be made to improve the accessibility and convenience of vaccination services on campuses and nearby areas. In the context of C-M China, cultural beliefs, preference for relying on natural immunity, and trust in alternative healthcare systems can influence vaccine intention. Cultural norms, such as reliance on natural remedies or a preference for traditional healthcare practices, contribute to vaccine hesitancy or delay, consistent with previous findings.Citation51 While traditional Chinese medicine’s preference for herbal remedies to treat influenza may bring attention to the issue, there are concerns about the effectiveness.Citation52 Therefore, promoting preventive care through vaccination is crucial, as it offers a proactive approach to healthcare rather than just a curative one.Citation53

Several factors were identified as enablers of vaccine acceptance and intention. These included the vaccination behavior of individuals within their social circles who have received the vaccine, motivation to protect others, and concerns about seeking medical resources during the COVID-19 pandemic. Interestingly, a difference was observed in the vaccine information sources between C-UK and C-M students. C-M students relied more on recommendations from healthcare workers and government or university promotions,Citation8 while C-UK students heavily relied on online information. While acknowledging that cultural and environmental factors may contribute to the observed variations and warrant further investigation, it is evident that the perspectives of peers, medical professionals, and government and university campaigns significantly influence vaccination attitudes among C-M students.

Furthermore, the logistic regression analysis found that knowledge and reinforcement domains were positively associated with previous influenza vaccine acceptance and vaccination intention in both C-M and C-UK student groups. Conversely, belief about consequences was negatively correlated with both indicators. This indicates that students who have positive beliefs about the severity and impacts of influenza tend to exhibit lower vaccine intention and acceptance, which aligns with evidence from previous studies.Citation19,Citation54,Citation55 Addressing misconceptions and enhancing confidence in the vaccine’s effectiveness through targeted educational campaigns and accurate information dissemination are essential to improve vaccine acceptance.Citation56,Citation57 Additionally, among C-UK students, intention was positively associated with emotions, including fear of living alone while studying abroad, concerns about the impact of COVID-19, and spreading the virus to others, which supports the study’s hypothesis. In comparison, among C-M students, intention was correlated with environmental context and resources (such as distance, time, and affordability) and social influences. These findings provide valuable insights for designing future interventions tailored to the specific needs of each group.

Another intriguing finding in our study is the noteworthy surge in vaccination intention reported at the end in comparison to participants’ initial responses. This may be attributed to the survey questions, which could have heightened awareness about the importance of the influenza vaccine. Further qualitative investigations are warranted to delve into the reasons behind this positive change. It is essential to note that this increase aligns with the well-known Hawthorne effect, wherein individuals tend to alter their behavior when they are aware of being observed.Citation58,Citation59 Nonetheless, these results indicated the potential effectiveness of interventions incorporating education and reminders in enhancing influenza vaccination intention among Chinese students.

Implications for intervention design

The main barrier to receiving the influenza vaccine is a lack of knowledge and belief about the consequences of vaccination. Targeted educational information emphasizing the safety, necessity, and benefits of the vaccine is recommended. It is important to tailor the communication strategy according to the preferences of the target group.Citation60 For instance, to promote vaccination among C-UK students, leveraging social networks and influential community members may be effective. It is important to note that the impact of social media as both an enabler and a potential barrier to vaccination information dissemination was not specifically assessed in the study survey.Citation56,Citation61 This aspect should be considered in future research to provide a more comprehensive understanding of the factors influencing vaccination attitudes. On the other hand, mainland students may respond better to policies and campaigns promoted by the government. Additionally, limited knowledge about accessing vaccines and related information hinders vaccine acceptance among students, particularly C-UK students. This suggests that Chinese students, as an ethnic minority group, may face access issues due to language and cultural barriers. They may also lack the skills to navigate the UK health system effectively. In particular, foreign-born Chinese might not be clear about healthcare services (e.g., ways to find vaccine services, steps to book appointments, or payment methods or procedures).Citation62 Offering clear information on how and where to receive the vaccine in the UK would be helpful in addressing this barrier and potentially increasing their vaccination intention and acceptance.

Furthermore, incorporating the Theoretical Domains Framework (TDF) and COM-B model can provide a better understanding of vaccination behavior.Citation31,Citation56 Within this framework, this study represents the first step in understanding the behavior and identifying areas that require change. As summarized earlier, significant underlying mechanisms, including facilitators and obstacles, have been systematically identified. These mechanisms of action serve as potential targets for future interventions aimed at increasing vaccine uptake rates and addressing vaccine hesitancy among Chinese university students. In the next stage, it is recommended to use a comprehensive intervention mapping approach based on the behavior change wheel to select potential intervention functions and techniques.Citation63 Moreover, understanding how to enhance intention by improving the environmental context and providing resources can also potentially influence vaccine behavior.Citation64 This process requires restructuring the overall context, involving stakeholders such as the public sector, universities, and media to reduce barriers to vaccine and information access.

Strengths and limitations

This study offers valuable insights into influenza vaccination intention among Chinese university students in the UK and Mainland China, with notable strengths contributing to our understanding. One strength is the inclusion of two student groups with relatively larger sample sizes, allowing for a more in-depth analysis. This enables a better understanding of the barriers, enablers, and associated factors specific to each group, which is crucial for designing tailored interventions using a co-design approach with the end-user group. However, it is important to interpret the findings with caution due to the differences in demographic characteristics between the two groups. To address this, statistical methods were employed to adjust for these differences during the regression modeling.

There are limitations to this study. One limitation is the use of a self-reported survey, which may restrict the ability to conduct a more in-depth evaluation of vaccination barriers and verify participants’ actual immunization status. Additionally, the non-probability sampling method used to recruit students may introduce sampling bias,Citation65 which should be taken into consideration when interpreting the findings. In particular, it is essential to discuss the potential bias introduced by snowball sampling, particularly the risk of oversampling students within a population who share similar perceptions and value assessments of vaccination.Citation66 To minimize potential bias, efforts were made to include students from various universities in both countries and keep the questionnaire concise and accessible. Furthermore, as mentioned above, the generalizability of the findings may be limited by the demographic characteristics of the sample. For example, there was a higher proportion of medical students in the Mainland China sample than the UK sample, which could have influenced some of the results. The unequal distribution of participants across cities in both countries may introduce selection bias, limiting the representativeness of the samples, and potentially affecting the generalizability of our findings to the larger Chinese student population. Additionally, a relatively high proportion of female respondents participated in the study. However, gender did not show any significant effects on vaccination intention in the present study. Moreover, it is essential to acknowledge that the timing of the survey falls outside the typical influenza season and it occurred during the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, characterized by lockdowns and a focus on COVID-19 vaccination, which likely influenced social interactions and perception of disease risk. Consequently, the acceptance estimates generated from our study may have limited generalizability to other times. Another factor to consider is that the characteristics of the vaccines, such as the type, company, and country of manufacture, were not taken into account, which could potentially impact vaccination intention.

Despite these limitations, the findings of this study provide valuable insights into influenza vaccination intention among Chinese university students and lay the groundwork for further research and the development of targeted interventions.

Conclusion

This study sheds light on the factors influencing influenza vaccine acceptance and intention among Chinese university students studying in the UK and Mainland China. The findings highlight the critical need to bridge knowledge gaps, address beliefs about consequences, harness social influences, enhance vaccination service accessibility, and consider emotional factors to effectively promote vaccine acceptance and intention within this demographic. Key barriers identified include insufficient knowledge and misconceptions regarding the consequences of influenza vaccination. To overcome these challenges, tailored communication strategies are imperative, with social media platforms catering to C-UK students and government or university promotions being more effective for C-M students. Meanwhile, the findings support the notion that greater knowledge of influenza, the vaccine and its access, and adequate social support would likely increase the vaccine intention and acceptance. These insights contribute to formulating targeted interventions aimed at elevating influenza vaccine uptake rates and mitigating vaccine hesitancy among Chinese university students. Further research and comprehensive intervention mapping based on behavior change models are recommended to address the identified barriers and facilitate vaccine uptake among this population.

Author contributions statement

LL, CW, and PK were involved in the conception and design of the study and supervised the data collection. LL, LY, and QW contributed to the data collection. LL analyzed and interpreted the collected data. LL wrote the manuscript independently, and other authors revised and commented on it critically for intellectual content. All authors critically revised, reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Supplementary Material 3.pdf

Download PDF (161.4 KB)Supplementary Material 2. Likert_Chart_Statistics.pdf

Download PDF (72.5 KB)Supplementary Material 1. Questionnaire English.doc

Download MS Word (137.5 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The survey data is available on request provided ethics committee approval for sharing the anonymized data is granted. To request access conditional on approval, please contact [email protected].

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed on the publisher’s website at https://doi.org/10.1080/21645515.2023.2290798.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Li J, Chen Y, Wang X, Yu H. Influenza-associated disease burden in mainland China: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci Rep [Internet]. 2021;11:2886. [accessed 2021 Oct 23]. https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-021-82161-z110.1038/s41598-021-82161-z.

- China CDC. Influenza Vaccination Technical Guidelines (2020-2021) [Internet]. 2020. https://www.chinacdc.cn/jkzt/crb/bl/lxxgm/jszl_2251/202009/P020200911453961714086.pdf.

- Kawahara Y, Nishiura H. Exploring influenza vaccine uptake and its determinants among university students: a cross-sectional study. Vaccines [Internet] 2020;8(1):52. [accessed 2022 May 8]. https://www.mdpi.com/2076-393X/8/1/52.

- Marczinski CA. Perceptions of pandemic influenza vaccines. Hum Vaccines Immunother [Internet] 2012;8(2):275–12. [accessed 2022 May 8]. doi:10.4161/hv.18457.

- Vemula SV, Sayedahmed EE, Sambhara S, Mittal SK. Vaccine approaches conferring cross-protection against influenza viruses. Expert Rev Vaccines [Internet]. 2017;16(11):1141–54. [accessed 2022 May 8]. doi:10.1080/14760584.2017.1379396.

- Plans-Rubió P. The vaccination coverage required to establish herd immunity against influenza viruses. Prev Med [Internet]. 2012;55:72–7. [accessed 2022 May 8]. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0091743512000588110.1016/j.ypmed.2012.02.015.

- Palache A, Oriol-Mathieu V, Abelin A, Music T. Seasonal influenza vaccine dose distribution in 157 countries (2004–2011). Vaccine. 2014;32:6369–76. [accessed 2022 Sep 6]. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0264410X140093844810.1016/j.vaccine.2014.07.012.

- Wang Q, Yue N, Zheng M, Wang D, Duan C, Yu X, Zhang X, Bao C, Jin H. Influenza vaccination coverage of population and the factors influencing influenza vaccination in mainland China: a meta-analysis. Vaccine. 2018;36(48):7262–9. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2018.10.045.

- Yuen CYS, Tarrant M. Determinants of uptake of influenza vaccination among pregnant women – a systematic review. Vaccine. 2014;32:4602–13. [accessed 2021 Oct 24]. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0264410X140086883610.1016/j.vaccine.2014.06.067.

- Chen C, Liu X, Yan D, Zhou Y, Ding C, Chen L, Lan L, Huang C, Jiang D, Zhang X, et al. Global influenza vaccination rates and factors associated with influenza vaccination. Int J Infect Dis [Internet]. 2022;125:153–63. [accessed 2023 Nov 9]. https://www.ijidonline.com/article/S1201-9712(22)00574-4/fulltext10.1016/j.ijid.2022.10.038.

- Nikbakht R, Baneshi MR, Bahrampour A, Hosseinnataj A. Comparison of methods to estimate basic reproduction number (R0) of influenza, using Canada 2009 and 2017-18 a (H1N1) data. J Res Med Sci [Internet]. 2019;24:67. [accessed 2023 Nov 9]. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6670001/110.4103/jrms.JRMS88818.

- Fu X, Zhou Y, Wu J, Liu X, Ding C, Huang C, Deng M, Shi D, Wang C, Xu K, et al. A severe seasonal influenza epidemic during 2017–2018 in China after the 2009 pandemic influenza: a modeling study. Infecti Microbes Dis [Internet]. 2019;1:20. [accessed 2023 Nov 9]. https://journals.lww.com/imd/Fulltext/2019/09000/ASevereSeasonalInfluenzaEpidemicDuring.4.aspx110.1097/IM9.0000000000000006.

- Wang Q, Xiu S, Zhao S, Wang J, Han Y, Dong S, Huang J, Cui T, Yang L, Shi N, et al. Vaccine hesitancy: COVID-19 and influenza vaccine willingness among parents in Wuxi, China—A cross-sectional study. Vaccines [Internet]. 2021;9(4):342. [accessed 2021 Nov 9]. https://www.mdpi.com/2076-393X/9/4/342.

- Guh A, Reed C, Gould LH, Kutty P, Iuliano D, Mitchell T, Dee D, Desai M, Siebold J, Silverman P, et al. Transmission of 2009 pandemic influenza a (H1N1) at a public university—Delaware, April–May 2009. Cli Infect Dis [Internet]. 2011;52:S131–7. [accessed 2022 May 8] . doi:10.1093/cid/ciq029.

- Uchida M, Tsukahara T, Kaneko M, Washizuka S, Kawa S. How the H1N1 influenza epidemic spread among university students in Japan: experience from Shinshu university. Am J Infect Control [Internet]. 2012;40:218–20. [accessed 2022 May 8]. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0196655311002306310.1016/j.ajic.2011.03.012.

- Bednarczyk RA, Chu SL, Sickler H, Shaw J, Nadeau JA, McNutt L-A. Low uptake of influenza vaccine among university students: evaluating predictors beyond cost and safety concerns. Vaccine. 2015;33:1659–63. [accessed 2022 Sep 6]. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0264410X150022241410.1016/j.vaccine.2015.02.033.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Update: influenza activity - United States, 2009-10 season. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2010;59(29):901–8.

- Nichol KL, Heilly SD, Ehlinger E. Colds and influenza-like illnesses in university students: impact on Health, academic and work performance, and Health care use. Clin Infect Dis [Internet]. 2005;40(9):1263–70. [accessed 2022 May 8]. doi:10.1086/429237.

- Shon E-J, Choe S, Lee L, Ki Y. Influenza vaccination among U.S. College or university students: a systematic review. Am J Health Promot [Internet]. 2021;35(5):708–19. [accessed 2022 May 8]. doi:10.1177/0890117120985833.

- Cole AP, Gill JM, Fletcher KD, Shivers CA, Allen LC, Mwendwa DT. Understanding African American college students’ H1N1 vaccination decisions. Health Psychology [Internet]. 2015;34(12):1185–90. [accessed 2022 May 18]. doi:10.1037/hea0000232.

- Lawrence HY. Healthy bodies, toxic medicines: college students and the rhetorics of flu vaccination. Yale J Biol Med [Internet]. 2014;87:423–37. [accessed 2022 May 18]. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4257030/.

- Ravert RD, Fu LY, Zimet GD. Reasons for low pandemic H1N1 2009 vaccine acceptance within a College sample. Adv Prev Med [Internet]. 2012;2012:e242518. [accessed 2022 May 18]. https://www.hindawi.com/journals/apm/2012/242518/.

- Sandler K, Srivastava T, Fawole OA, Fasano C, Feemster KA. Understanding vaccine knowledge, attitudes, and decision-making through college student interviews. J Am Coll Health [Internet]. 2020;68(6):593–602. [accessed 2022 May 18]. doi:10.1080/07448481.2019.1583660.

- Yang ZJ. Too scared or too capable? Why do college students stay away from the H1N1 vaccine?. Risk analysis Internet. 2012;32:1703–16. [accessed 2022 May 18]. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/j.1539-6924.2012.01799.xRiskAnalysis1010.1111/j.1539-6924.2012.01799.x.

- Textor C China: study abroad destinations 2022 [Internet]. Statista2022. [accessed 2023 Jun 30]. https://www.statista.com/statistics/1108708/china-students-preferred-destinations-for-study-abroad/.

- Nan X, Kim J. Predicting H1N1 vaccine uptake and H1N1-related Health beliefs: the role of individual difference in consideration of future consequences. J Healthc Commun [Internet]. 2014;19(3):376–88. [accessed 2022 May 18]. doi:10.1080/10810730.2013.821552.

- Nyhan B, Reifler J, Richey S. The role of social networks in influenza vaccine attitudes and intentions among college students in the Southeastern United States. J Adolesc Health [Internet]. 2012;51:302–4. [accessed 2022 May 8]. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1054139X12000961310.1016/j.jadohealth.2012.02.014.

- Ratnapradipa KL, Norrenberns R, Turner JA, Kunerth A. Freshman flu vaccination behavior and intention during a Nonpandemic season. Health Promot Pract. 2017;18(5):662–71. [accessed 2022 May 18]. doi:10.1177/1524839917712731.

- Kostkova P, Mano V, Larson HJ, Schulz WS VAC Medi+board: analysing vaccine rumours in news and social media [Internet]. In: Proceedings of the 6th International Conference on Digital Health Conference. New York, NY, USA: Association for Computing Machinery; 2016:163–4. [accessed 2021 Jul 6]. doi:10.1145/2896338.2896370

- Kostkova P, Mano V, Larson HJ, Schulz WS. Who is spreading rumours about vaccines? Influential user impact modelling in social networks. ACM International Conference Proceeding Series. 2017;Part F128634:48–52.

- Michie S, van Stralen MM, West R. The behaviour change wheel: a new method for characterising and designing behaviour change interventions. Implement Sci [Internet]. 2011;6(1):42. [accessed 2021 Nov 20]. doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-6-42.

- Embassy of China in the UK. Basic information of overseas students, Chinese-funded enterprises, overseas Chinese and other groups in the UK [Internet]. 2021. [accessed 2022 May 8]. https://www.mfa.gov.cn/ce/ceuk//chn/lsfw/yingredianfangzuifangfan2021/t1877042.htm.

- Feng W, Cui J, Li H. Determinants of willingness of patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus to receive the seasonal influenza vaccine in Southeast China. Int J Env Res Pub He. 2019;16(12):2203. doi:10.3390/ijerph16122203.

- NHS. Flu vaccine [Internet]. 2019 [accessed 2022 May 8]. https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/vaccinations/flu-influenza-vaccine/.

- Ministry of foreign affairs of the People’s Republic of China. Dynamic zero-COVID: a MUST approach for China [Internet]. fmprc.gov.cn2022. [accessed 2023 Nov 13]. https://www.fmprc.gov.cn/mfa_eng/wjb_663304/zwjg_665342/zwbd_665378/202207/t20220715_10722096.html.

- UK Health Security Agency. Public reminded to stay safe as COVID-19 England restrictions lift [Internet]. GOV.UK2022. [accessed 2023 Nov 13]. https://www.gov.uk/government/news/public-reminded-to-stay-safe-as-covid-19-england-restrictions-lift.

- Atkins L, Francis J, Islam R, O’Connor D, Patey A, Ivers N, Foy R, Duncan EM, Colquhoun H, Grimshaw JM, et al. A guide to using the Theoretical domains framework of behaviour change to investigate implementation problems. Implement Sci [Internet]. 2017;12(1):77. [accessed 2021 Nov 24]. doi:10.1186/s13012-017-0605-9.

- Cane J, O’Connor D, Michie S. Validation of the theoretical domains framework for use in behaviour change and implementation research. Implement Sci [Internet]. 2012;7(1):37. [accessed 2021 Jun 4]. doi:10.1186/1748-5908-7-37.

- WHO Europe. TIP tailoring immunization programmes [Internet]. Copenhagen: WHO Regional Office for Europe; 2019. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/329448/9789289054492-eng.pdf.

- Crawshaw J, Konnyu K, Castillo G, Allen Z, van Grimshaw J, Presseau J. Factors affecting COVID-19 vaccination acceptance and uptake among the general public: a living behavioural science evidence synthesis. v.1.0. 2021 Apr 30. Canada: Ottawa Hospital Research Institute.

- Alhusein N, Scott J, Neale J, Chater A, Family H. Community pharmacists’ views on providing a reproductive health service to women receiving opioid substitution treatment: a qualitative study using the TDF and COM-B. Explor Res Clin Soc Pharm [Internet]. 2021;4:100071. [accessed 2023 Jun 5]. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2667276621000718.

- Austin JD, Rodriguez SA, Savas LS, Megdal T, Ramondetta L, Fernandez ME. Using intervention mapping to develop a provider intervention to increase HPV vaccination in a federally qualified health center. Front Public Health [Internet]. 2020;8. [accessed 2021 Jun 4]. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7775559/.

- Strack F. Order effects” in survey research: activation and information functions of preceding questions [Internet]. In: Schwarz N Sudman S, editors. Context effects in social and psychological research. New York, NY: Springer; 1992. pp. 23–34. [accessed 2023 Nov 10]. doi:10.1007/978-1-4612-2848-6_3.

- Wadgave U, Khairnar MR. Parametric tests for Likert scale: for and against. Asian J Psychiatr [Internet]. 2016;24:67–8. [accessed 2022 Sep 6]. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1876201816303628.

- R Core Team. R: a language and environment for statistical computing. [Internet]. 2022. [accessed 2023 Nov 14]. https://www.r-project.org/.

- Ripley B, Venables B, Bates DM, Ca 1998) KH (partial port, ca 1998) AG (partial port, Firth D. MASS: support functions and datasets for Venables and Ripley’s MASS [Internet]. 2023. [accessed 2023 Nov 14]. https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/MASS/index.html.

- Bryer J, Speerschneider K Likert: analysis and visualization Likert items [Internet]. 2016 [accessed 2023 Nov 14]. https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/likert/index.html.

- Seale H, Wang Q, Yang P, Dwyer D, Zhang Y, Wang X, Li X, MacIntyre C. Hospital health care workers’ understanding of and attitudes toward pandemic influenza in Beijing. Asia-Pacific J Public Health. 2012;24(1):39–47. doi:10.1177/1010539510365097.

- Li R, Xie R, Yang C, Rainey J, Song Y, Greene C. Identifying ways to increase seasonal influenza vaccine uptake among pregnant women in China: a qualitative investigation of pregnant women and their obstetricians. Vaccine [Internet]. 2018;36:3315–22. [acessed 2021 Nov 11]. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0264410X183055772310.1016/j.vaccine.2018.04.060.

- Yang H, Chen Z, Fan Y, Hu X, Wu T, Kang S, Xiao B, Zhang M. Knowledge, attitudes and anxiety toward COVID-19 among domestic and overseas Chinese college students. J Public Health [Internet]. 2021;43(3):466–71. [accessed 2023 Aug 17]. doi:10.1093/pubmed/fdaa268.

- Wang X, Jia W, Zhao A, Wang X. Anti-influenza agents from plants and traditional Chinese medicine. Phytother Res [Internet]. 2006;20(5):335–41. [accessed 2023 Aug 17]. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1002/ptr.1892.

- Nabeshima S, Kashiwagi K, Ajisaka K, Masui S, Takeoka H, Ikematsu H, Kashiwagi S. A randomized, controlled trial comparing traditional herbal medicine and neuraminidase inhibitors in the treatment of seasonal influenza. J Infect Chemother [Internet]. 2012;18:534–43. [accessed 2023 Aug 17]. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1341321X12702829410.1007/s10156-012-0378-7.

- Demicheli V, Jefferson T, Rivetti D, Deeks J. Prevention and early treatment of influenza in healthy adults. Vaccine. 2000;18(11–12):957–1030. [accessed 2023 Nov 10]. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0264410X99003321.

- MacDonald L, Cairns G, Angus K, de Andrade M. Promotional Communications for Influenza Vaccination: A Systematic Review. J Health Commun [Internet]. 2013;18(12):1523–49. [accessed 2022 May 18]. doi:10.1080/10810730.2013.840697.

- Schmid P, Rauber D, Betsch C, Lidolt G, Denker M-L, Cowling BJ. Barriers of influenza vaccination intention and behavior – a systematic review of influenza vaccine hesitancy, 2005 – 2016. PLOS ONE [Internet]. 2017;12(1):e0170550. [accessed 2021 Oct 24]. https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0170550.

- Li L, Wood CE, Kostkova P. Vaccine hesitancy and behavior change theory-based social media interventions: a systematic review. Transl Behav Med [Internet]. [accessed 2021 Dec 7]. 2021; ibab148. 10.1093/tbm/ibab148.

- Yang L, Zhen S, Li L, Wang Q, Yang G, Cui T, Shi N, Xiu S, Zhu L, Xu X, et al. Assessing vaccine literacy and exploring its association with vaccine hesitancy: a validation of the vaccine literacy scale in China. J Affect Disord [Internet]. 2023;330:275–82. [accessed 2023 Aug 17]. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0165032723003488.

- McCambridge J, Witton J, Elbourne DR. Systematic review of the Hawthorne effect: new concepts are needed to study research participation effects. J Clin Epidemiol [Internet]. 2014;67:267–77. [accessed 2023 Nov 9]. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0895435613003545310.1016/j.jclinepi.2013.08.015.

- McIlvaine HP. What happened at Hawthorne? In: Robert L. Hamblin, John H. Kunkel, editors. Behavioral theory in sociology. New York: Routledge. 2021. pp. 323–57.

- Dubé E, Gagnon D, MacDonald NE. Strategies intended to address vaccine hesitancy: review of published reviews. Vaccine. 2015;33:4191–203. [accessed 2022 Jan 7]. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0264410X150050583410.1016/j.vaccine.2015.04.041.

- Wilson SL, Wiysonge C. Social media and vaccine hesitancy. BMJ Global Health [Internet]. 2020;5(10):e004206. [accessed 2021 Jun 4]. https://gh.bmj.com/content/5/10/e004206.10.1136/bmjgh-2020-004206.

- Lim J, Gonzalez P, Wang-Letzkus MF, Ashing-Giwa KT. Understanding the cultural health belief model influencing health behaviors and health-related quality of life between Latina and Asian-American breast cancer survivors. Support Care Cancer [Internet]. 2008;17(9):1137. [accessed 2022 May 18]. doi:10.1007/s00520-008-0547-5.

- Kok G, Schaalma H, Ruiter RAC, Van Empelen P, Brug J. Intervention mapping: protocol for applying health psychology theory to prevention programmes. J Health Psychol [Internet]. 2004;9(1):85–98. [accessed 2022 Jan 6]. doi:10.1177/1359105304038379.

- Ojo SO, Bailey DP, Brierley ML, Hewson DJ, Chater AM. Breaking barriers: using the behavior change wheel to develop a tailored intervention to overcome workplace inhibitors to breaking up sitting time. BMC Public Health [Internet]. 2019;19(1):1126. [accessed 2022 Jan 6]. doi:10.1186/s12889-019-7468-8.

- Nielsen M, Haun D, Kärtner J, Legare CH. The persistent sampling bias in developmental psychology: a call to action. J Exp Child Psychol [Internet]. 2017;162:31–8. [accessed 2023 Aug 17]. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0022096517300346.

- Parker C, Scott S, Geddes A. Snowball sampling. SAGE Research Methods Foundations [Internet] 2019. [accessed 2023 Nov 9]. http://methods.sagepub.com/foundations/snowball-sampling.