ABSTRACT

This study aimed to evaluate the knowledge and attitudes of community pharmacists (CPs) on vaccination and assess the barriers and willingness to implement community pharmacy-based vaccination services (CPBVS) in Ethiopia. An online cross-sectional study was conducted on 423 CPs in Ethiopia, and questionnaires were distributed to CPs through the Ethiopian Pharmaceutical Association telegram group and e-mail invitations. Data were analyzed using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) version 27. Most CPs (92%) had good knowledge of vaccination, and 43.5% strongly agreed that the population’s immunization rates would rise if CPs were authorized to provide vaccinations. The overall mean attitude score (±SD) toward vaccination was 35.95 (±4.11) out of a total score of 45, with 187 (44.2%) scoring below the mean. The most common barriers were lack of authorization (94.1%), costs and time associated with professional development and training (71.4%), time requirements for professional development (70%), and insufficient staff or resources for implementation (70%). Two hundred thirty CPs (54.4%) expressed a willingness to implement CPBVS. Educational qualifications were significantly associated with knowledge of CPs regarding vaccination. Those with inadequate knowledge had about 2.5 times (AOR = 2.51, 95% CI: 1.19, 5.31, p = .016) a poorer attitude toward vaccination services compared with those with adequate knowledge. Those study participants who had a good attitude toward vaccination services were nearly seven (AOR = 6.80, 95% CI: 4.36–10.59, p = .0001) times more willing to provide CPBVS when compared with their counterparts. Implementing CPBVS in Ethiopia requires overcoming barriers and providing professional development opportunities.

Introduction

Vaccination is one of the most efficient strategies for preventing infectious diseases.Citation1 Despite the immunization recommendations, vaccine-preventable diseases continue to pose a significant burden in many countriesCitation1,Citation2. To overcome inequities and reach national vaccination targets, Ethiopia’s Expanded Program on Immunization (EPI) must implement tailored interventions. This is because continuous efforts to improve vaccine coverage have uncovered preexisting obstacles.Citation3–6 To improve vaccination coverage challenges, several developed countries, including Canada, the United Kingdom, and the United States, have successfully implemented community pharmacy-based vaccination services (CPBVS), and since the 1990s, more than 30 countries have adopted this approach.Citation1,Citation7,Citation8 The CPBVS initiative has expanded the roles of community pharmacists (CPs), empowering them to administer vaccines, handle storage, report adverse events, and educate the public, provided they receive adequate training and certification in vaccine delivery.Citation8–11

Pharmacists in community pharmacy settings can play a crucial role in increasing immunization rates by providing convenient and accessible options for receiving vaccines.Citation12 They have successfully fulfilled these roles in community pharmacy settings in various countries by providing year-immunization services.Citation12–16 The CPBVS serves as a vital hub for information and vaccine administration, bridging the gap between the two.Citation17 Furthermore, these services are often more affordable for patients and insurance providers, and they have the potential to improve vaccination rates.Citation18 However, the implementation of CPBVS has faced various challenges, including issues related to the availability of private space for vaccine administration, reimbursement procedures, physician support, CP’s knowledge and skill levels, community demand and confidence, training programs, policy frameworks, patient safety concerns, recognition within the healthcare system, patient resistance, staffing shortages, and adaptation to suit the unique context.

Considering the significance of vaccination and the potential impact of CPBVS, it is important to explore their implementation in sub–Saharan African countries like Ethiopia.Citation19 Although community pharmacy staff members in Ethiopia are actively engaged in providing health services related to advice on vitamins and supplements, newborn milk or formulas, and minor symptoms, they are not involved in vaccination, as reported in a recent study.Citation20 Analyzing the barriers and advantages of CPBVS in Ethiopia will provide valuable insights for improving the healthcare system and addressing the challenges related to vaccination services.Citation18 The current study presents a pioneering initiative aiming to establish a baseline understanding of CPBVS, provide insights into community pharmacists’ knowledge, attitudes, barriers, and willingness to implement CPBVS, and ultimately inform evidence-based decision-making processes on the implementation of such services.

Methods

Study area

This study was conducted in Ethiopia, a country with an estimated total population of about 123.4 million people as of 2022. Ethiopia is administratively divided into 13 regions and two city administrations. CPs from all regions and city administrations in the country were included in this study.

Study design and period

A cross-sectional study was conducted among pharmacists working in community pharmacies in Ethiopia from March 25 to May 20, 2023, through a self-administered online survey. We designed this study to assess community pharmacists’ knowledge and attitudes regarding vaccination, as well as their perceived barriers to and willingness to implement CPBVS and the predictors of these outcomes.

Target, source, and study population

The target population consisted of CPs working in Ethiopia. All CPs working in Ethiopia were targeted, as this nationwide survey was intended to include CPs working in the country. The source population was CPs who received an online survey during the study period, whereas the study population comprised CPs who fulfilled the study criteria and participated in the study.

Eligibility criteria

The eligibility criteria were working as a CP in Ethiopia during the study period, willingness to participate in the study, and holding at least a bachelor’s degree in pharmacy.

Sample size and sampling techniques

The sample size was determined using the single-population proportion formula. The sample size was determined by using the single population proportion formula by considering the assumptions Zα/2 = critical value for normal distribution at 95% confidence level, which equals 1.96 (z value at α = 0.05), estimated proportion (p = 50% as there were no previous studies on CPBVS in Ethiopia), and absolute precision or margin of error 5% (d = 0.05). This calculation resulted in an initial calculated sample size of 384. To account for potential incomplete, non-response rate, or withdrawn data, a 10% contingency was added, and the final sample size became 423 for this study.

Data collection tools and procedures

The main questionnaire used to assess knowledge, attitudes, barriers, and willingness was adapted from Edwards et al.Citation21 and subsequently modified to align with the characteristics and context of CPs in Ethiopia. It was structured into five sections. Section I gathered CPs’ socio-demographic information (gender, age, years of practice in a pharmacy and, highest pharmacy qualification, job title in the current role, and pharmacy setting, while Section II consisted of CPs’ knowledge vaccination. CPs were asked to choose one answer from “yes,” “no,” and “don’t know” for each statement or question. Correct responses were scored as one (1), while incorrect and “don’t know” responses were scored as zero (0). The scores for each respondent were summed up. A score of 37.5% or less (scores of 3 or less), a score between 50% and 62.5% (scores of 4–5), and those who scored 75% and above (scores of 6 and above) were categorized as having a low, moderate, and good knowledge level on vaccination, respectively. Section III assessed the attitude of CPs toward vaccination services, and it was evaluated using a 5-point Likert scale of “strongly agree” to “strongly disagree.” For positive statements, “strongly disagree,” “disagree,” “neutral,” “agree,” and “strongly agree” responses were given one (1), two (2), three (3), four (4), and five (5) marks, respectively. Reverse scoring was carried out on one negative statement. A higher score, i.e., above the mean score, indicated a good attitude toward the immunization services. Sections IV and V addressed barriers and willingness to implement CBPVS, respectively. Potential barrier statements were listed, and participants were asked to select all that apply to them, while the willingness to implement the CBPVS question had three choices (yes, no, and uncertain) for each statement or question. Responses were scored as one (1) for ‘Yes responses, and the scores of ‘No were summed up as zero (0).

Data collection

Data were collected electronically using the Google Forms platform. The online questionnaire featured an introductory section that provided participants with an overview of the study’s purpose, inclusion/exclusion criteria, a virtual consent form, and expectations from study participants. Following this, participants were directed to the main body of the questionnaire. The online survey questionnaire link was distributed primarily through the Ethiopian Pharmaceutical Association Office to engage CPs from various regions of the country. Additionally, various communication modalities, including e-mail, Telegram, WhatsApp, and LinkedIn, were utilized to invite individuals to complete the survey and encourage them to share the survey link within their networks. This multi-modal approach aimed to reach a diverse range of CPs across the nation.

Data quality assurance

To ensure data quality, a pretest was conducted to assess the clarity and effectiveness of the data collection tool. Based on the results of the pretest, necessary adjustments were made to refine the online survey tool using Google Forms. To prevent duplicate submissions, the survey tool was designed to restrict multiple entries from the same participant. After data collection, a thorough review was carried out to ensure data completeness and integrity. Any incomplete data entries were excluded from the analysis to maintain data quality.

Data analysis

The data collected through online Google Forms was exported to Excel formats and subsequently transferred to SPPS for analysis. Data cleaning and coding were performed as necessary. The data was then exported to SPSS version 27 for final analysis. Descriptive data were summarized using frequencies and percentages. To identify factors associated with the outcome variable, binary logistic regression was employed. Variables with p < .25 (based on the Wald test from logistic regression) in bivariate analysis were considered candidates for multivariable analysis to adjust for potential confounding effects. The association between independent and dependent factors was determined using odds ratios (ORs) with a 95% confidence interval (CI). Statistical significance was established at p < .05 in multivariable analysis. Attitude-related questions were scored on a scale of 0 to 45, with scores below the mean (<35.9) indicating a poor attitude.

Ethical approval

Ethical approval (Ref. No.: ERB/SOP/472/15/2023) was obtained from the Ethical Review Committee of the School of Pharmacy, College of Health Sciences, Addis Ababa University, Ethiopia. Before participating in the study, participants were asked to provide virtual informed consent. They were provided with comprehensive information about the study’s purpose and were assured that all information provided would be treated with strict confidentiality.

Results

Socio-demographic profile of study participants

Out of the total 423 community pharmacists included in the study, 230 (54.4%) were female and 193 (45.6%) were male participants, with a mean age of 34.29 ± 8.78 years (range 23 to 65). Most of the participants (71.2%) were working in Addis Ababa, and their mean total years of experience as a pharmacist and working in pharmacies were 8.71 ± 7.22 and 6.50 ± 5.61 years, respectively. About 60% of pharmacists had a dispensing role, 87.3% worked during the daytime shift, and more than two-thirds (68.3%) of the participants practiced in private pharmacy settings ().

Table 1. Socio-demographic profile of community pharmacists working in Ethiopia (N = 423).

Knowledge of community pharmacists in vaccination

The mean knowledge score of CPs on vaccination was 7.26 (±1.03). All CPs correctly answered the importance of vaccines in preventing and controlling infectious diseases. Furthermore, 98.3 and 98.1% of CPs answered questions related to the health benefits of vaccines rather than their risks and the potential impact of improper storage on the immune response of the vaccine recipients, respectively ().

Table 2. Knowledge of community pharmacists on vaccination (N = 423).

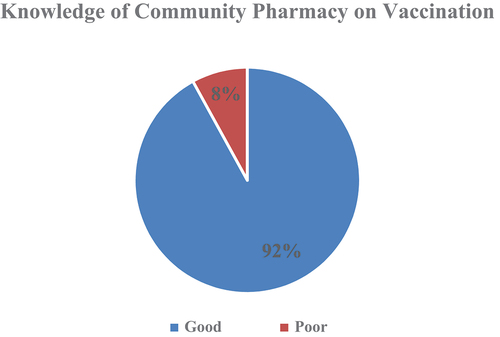

Most community pharmacists (92%) had good knowledge about vaccination and detail is provided in .

Attitude of community pharmacists in vaccination

Approximately a quarter of the respondents (23.6%) strongly agreed that CPs should be permitted to expand their practice to include the administration of vaccines. Moreover, 52.7% of the participants stated the necessity of formal certification for CPS to provide this service. Furthermore, 68.7% of the respondents strongly agreed that pharmacists’ opinions should be considered when expanding CPs’ scope to the administration of vaccines. In this survey, 43.5% of CPs strongly agreed that allowing them to offer vaccination services would lead to an increased proportion of the population receiving immunization ().

Table 3. Attitude of community pharmacists in vaccination and community pharmacy-based vaccination services (N = 423).

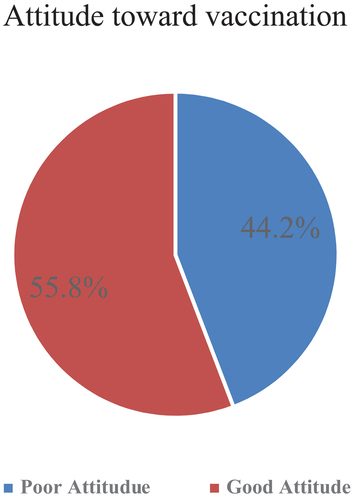

The overall mean score (±SD) of the attitude of the participants toward vaccination was 35.95 (± 4.11) from an overall score of 45, with 187 (44.2%) scoring below the mean, indicating having a poor attitude toward vaccination service ().

Barriers to community pharmacy-based vaccination services

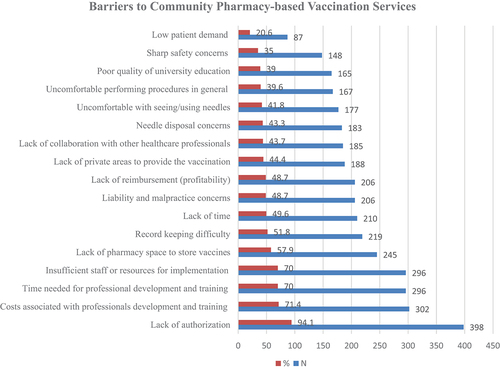

In this study, 18 key perceived barriers to implementing CPBVS were identified. More than half of the identified barriers were mentioned by 40% of CPs included in this study. The most common barriers identified by CPs were lack of authorization (94.1%), cost and time associated with professional development and training (71.4%), followed by time needed for professional development (70%), and insufficient staff or resources for implementation (70%). In contrast, low patient demand (20.6%) and sharp safety concerns (35%) were the least common barriers listed by CPs to CPBVS in their practice ().

Willingness of community pharmacists in vaccine administration

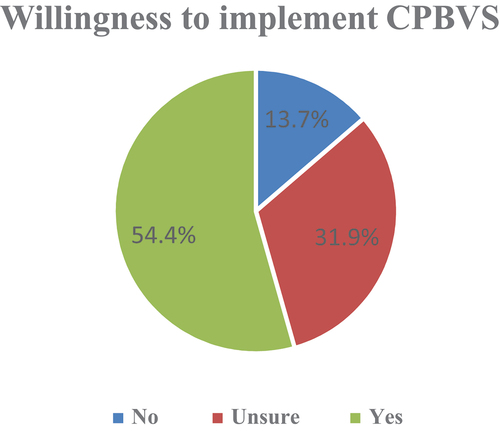

More than half of the CPs (54.4%) expressed their willingness to implement CPBVS into their practice ().

Predictors of vaccination knowledge among community pharmacists

Of the eight variables () included in the multivariable logistic regression following univariable binary logistic regression analysis, none of the variables were significantly associated with the knowledge status of pharmacy professionals working at community pharmacies toward vaccination services. However, in the univariable binary logistic regression analysis, educational qualification was significantly associated with community pharmacists’ knowledge of vaccination services ().

Table 4. Factors associated with knowledge of vaccination among CPs in Ethiopia.

Factors associated with attitude toward vaccination

Nine variables () were assessed to identify their association with community pharmacists’ attitudes toward vaccination services. Of the nine variables, in the univariable binary logistic regression analysis, four variables, namely age, highest educational qualification, years of experience, and knowledge, were significantly associated with community pharmacy professionals’ attitudes toward vaccination services at the community pharmacy level. However, in the multivariable binary logistic regression analysis following the univariable binary logistic regression analysis, only knowledge status was significantly associated with pharmacy professionals’ attitudes toward vaccination services at the community pharmacy level. Study participants who had inadequate knowledge had about 2.5 times (AOR = 2.51, 95%CI:1.19, 5.31, p = .016) and a poor attitude toward vaccination services at the community pharmacy level compared with those with adequate knowledge ().

Table 5. Factors associated with pharmacy professionals’ attitude toward vaccination service at the community pharmacy level.

Factors associated with the willingness to implement CPBVS

A total of those ten variables were assessed to see the association between pharmacy professionals’ willingness to provide vaccination services at the community pharmacy level. Out of the nine variables included in the multivariable binary logistic regression analysis model following univariable binary logistic regression analysis; only the attitude of professionals was significantly associated with willingness to provide vaccination service at the community pharmacy level. Those study participants who had a good attitude toward vaccination service were nearly seven (AOR = 6.80, 95%CI: 4.36–10.59, p = .0001) times more than willing to provide vaccination service at the community pharmacy level compared with their counterparts ().

Table 6. Factors associated with the willingness of pharmacy professionals to implement CPBVS.

Discussion

This is the first study in Ethiopia to assess community pharmacists on knowledge and attitudes vaccination service and their barriers and willingness to implement CPBVS. Furthermore, we analyzed predictors and offered interpretations, implications for public health practice, and recommendations for policy and advocacy. The participants of this study constitute a diverse group of community pharmacists, primarily based in Addis Ababa, with a significant number holding bachelor’s degrees in pharmacy. Their average years of experience in both pharmacy and community pharmacy settings was considerable. This profile underscores the potential significance of the study findings for the broader pharmacist community in Ethiopia.

A high level of knowledge among CPs regarding the importance of vaccines in preventing infectious diseases and the potential risks associated with improper storage is an encouraging finding. This suggests that CPs are cognizant of the critical role that vaccines play in public health, as well experienced in CanadaCitation22 and Italy.Citation23 However, the study also revealed that only 17% of the CPs strongly agreed that they received adequate training on vaccination during their pharmacy studies. This deficit in education implies a need for robust curriculum enhancement, ensuring that pharmacy students are comprehensively trained in vaccination.Citation24 Such improvements can empower CPs with the knowledge and skills necessary to provide effective vaccination services. These findings align with previous research demonstrating that pharmacists generally possess solid knowledge about vaccines and their role in public health.Citation22

The study identified a substantial willingness among CPs to expand their practices to include vaccine administration. This willingness aligns with prevailing regionalCitation25 and globalCitation26,Citation27 trends involving pharmacists in vaccination efforts. Furthermore, the recognition that formal training program and certification is necessary for providing vaccination services reflects a commitment to ensuring quality and safety and ultimately to equipping pharmacists with the necessary skills and knowledge.Citation21,Citation28,Citation29 Professional advocacy can leverage well-regulated pharmacy roles, expand services efficiently and safely, and reach more clients.Citation30,Citation31 The significant agreement that pharmacists’ opinions should shape the expansion of their role indicates that involving CPs in healthcare decision-making processes is vital. Policymakers and stakeholders must leverage this willingness to expand the scope of pharmacy practices to include vaccination services. This aligns with the findings of similar studies in other countries where pharmacists’ expanded roles have been proposed and implemented.Citation7,Citation13,Citation30

The study revealed that a significant proportion of community pharmacists had a poor attitude toward vaccination services, with over 40% scoring below the mean on the attitude scale. However, our findings contradict previous studies on CPs’ vaccination attitudes.Citation7,Citation22,Citation32 This suggests that while knowledge may be adequate, there is room for improvement in shaping positive attitudes among pharmacists. This finding highlights the influence of attitudes on healthcare professionals’ willingness to participate in vaccination programs. This study identified several key barriers to implementing community pharmacy-based vaccination services in Ethiopia. The most prominent barrier is the lack of authorization, followed by concerns about the cost and time associated with professional development and training. Time constraints for professional development and resource shortages are also significant hurdles. These barriers underscore the urgent need for streamlined authorization processes and investments in training and resource provision.Citation33 Overcoming these obstacles is crucial for the effective integration of CPs into vaccination programs. These barriers align with barriers reported in other countries where pharmacist-administered vaccination services have been introduced.Citation11,Citation21,Citation34

More than half of the CPs expressed willingness to provide vaccination services. This willingness is closely associated with positive attitudes toward vaccination services. The correlation between attitude and willingness highlights the influential role of individual beliefs and perceptions.Citation35 This underscores the importance of fostering a supportive environment that nurtures a positive attitude among CPs. Public health authorities and professional associations should capitalize willingness of CPs to provide CPBVS by offering training and incentives to further motivate CPs to actively participate in vaccination services.Citation7,Citation11,Citation36 This willingness may serve as a foundation for future policy and practice changes in Ethiopia, aligning with trends seen in other regions where pharmacist roles have expanded to include vaccination services.

This study identified knowledge as a significant predictor of CPs’ attitudes toward vaccination services. CPs with inadequate knowledge were found to have poor attitudes toward vaccination services. This finding underscores the critical importance of addressing knowledge gaps through targeted training and education programs. Interventions that enhance CPs’ knowledge can lead to more favorable attitudes and, consequently, better participation in vaccination services. These findings have significant implications for public health in Ethiopia. Strengthening the knowledge base of CPs through improved education and training can enhance their readiness to engage in vaccination. Creating an enabling policy environment, reducing authorization barriers, and investing in resources are essential steps toward facilitating the integration of CPs into vaccination programs.Citation12,Citation37,Citation38 Furthermore, public health authorities should leverage the willingness and positive attitudes of CPs to expand vaccination coverage, particularly in underserved areas.

Strengths and limitations of the study

This study included a relatively large and diverse sample of patients with CPs in Ethiopia. Additionally, the findings of this study have practical implications, particularly for policymakers, to inform contemporary policy and practical decisions. Despite these strengths, this study has some limitations in its research design and data collection methods that should be acknowledged. First, it primarily focused on community pharmacists in Addis Ababa, which may not fully represent the diversity of pharmacists’ experiences and practices across different regions of Ethiopia. This geographical concentration could introduce sampling bias and limit the generalizability of the findings to the entire country. Second, this study relied on self-reported data gathered through an online questionnaire, which may be prone to response bias. Participants may provide socially desirable answers or inaccurately represent their attitudes and practices, which may affect the reliability of the findings. Moreover, the study did not provide detailed information on the psychometric properties of the survey questionnaire, including its validity and reliability, which might raise questions regarding the robustness and accuracy of the data collected. Finally, the response rate to the survey was not reported and potential non-response bias was not discussed. If a significant proportion of invited participants did not respond to the survey, this could have affected the study’s representativeness and introduced bias.

Conclusion

In summary, this study provides valuable insights into the readiness of community pharmacists in Ethiopia to participate in vaccination. The majority of CPs had a good knowledge of vaccination and held a positive attitude toward the implementation of community-based immunization services. This could help improve the coverage rate of the nation and improve the public’s accessibility and availability to the public health system. More than half of the CPs expressed willingness to provide vaccination services. However, perceived barriers should be addressed before expanding CPs’ roles as vaccinators for successful vaccination services in Ethiopia. Government, policymakers, and professional associations may consider reforming the national immunization program to include pharmacists as vaccination providers to enhance vaccination services in Ethiopia. Efforts to improve pharmacists’ attitudes toward vaccination can further facilitate active participation in public health initiatives.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all the study participants for their time and willingness to participate in the study. We would also like to forward our sincere gratitude to the Ethiopian Pharmaceutical Association for facilitating the study.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Ang WC, Fadzil MS, Ishak FN, Adenan NN, Nik Mohamed MH. Readiness and willingness of Malaysian community pharmacists in providing vaccination services. J Pharm Policy Pract. 2022;15(1):1–10. doi:10.1186/s40545-022-00478-0.

- Tang D, DeVit M, Johnston SA. Genetic immunization is a simple method for eliciting an immune response. Nature. 1992;356(6365):152–4. doi:10.1038/356152a0.

- Ababa A. Ethiopia national expanded program on immunization. 2021 Jul.

- Mihret Fetene S, Debebe Negash W, Shewarega ES, Asmamaw DB, Belay DG, Teklu RE, Aragaw FM, Alemu TG, Eshetu HB, Fentie EA. Determinants of full immunization coverage among children 12–23 months of age from deviant mothers/caregivers in Ethiopia: a multilevel analysis using 2016 demographic and health survey. Front Public Health. 2023;11. doi:10.3389/fpubh.2023.1085279.

- Lame P, Milabyo A, Tangney S, Onya GM, Luhata C, Le Gargasson J-B, Mputu C, Hoff NA, Merritt S, Mukadi DN, Sall DS, Otomba JS, El Mourid A, Lusamba P, Senouci K, et al. A successful national and multipartner approach to increase immunization coverage: the democratic Republic of Congo “Mashako plan” 2018–2020. Glob Health. 2023;11(2):1–16. doi:10.9745/GHSP-D-22-00326.

- Bele O, Barakamfitiye DG. The expanded program on immunization in the WHO African region: current situation and implementation constraints. Sante (Montrouge, France). 1994;4:137–42.

- Youssef D, Abou-Abbas L, Farhat S, Hassan H. Pharmacists as immunizers in Lebanon: a national survey of community pharmacists’ willingness and readiness to administer adult immunization. Hum Res Health. 2021;19(1):1–11. doi:10.1186/s12960-021-00673-1.

- Bach A, Goad J. The role of community pharmacy-based vaccination in the USA: current practice and future directions. Integr Pharm Res Pract. 2015;67. doi:10.2147/IPRP.S63822.

- Balkhi B, Aljadhey H, Mahmoud MA, Alrasheed M, Pont LG, Mekonnen AB, Alhawassi TM. Readiness and willingness to provide immunization services: a survey of community pharmacists in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. Saf Health. 2018;4(1):1–7. doi:10.1186/s40886-018-0068-y.

- Orenstein WA, Ferrara CP, Sprauer MA, Williams WW, Strikas RA. Pharmacists’ role in immunization. Am J Hosp Pharm. 1990;47(6):1273–4. doi:10.1093/ajhp/47.6.1273b.

- Jarab AS, Al-Qerem W, Mukattash TL. Community pharmacists’ willingness and barriers to provide vaccination during COVID-19 pandemic in Jordan. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2022;18(1):2016009. doi:10.1080/21645515.2021.2016009.

- Bach AT, Goad JA. The role of community pharmacy-based vaccination in the USA: current practice and future directions. Integr Pharm Res Pract. 2015;4:67–77. doi:10.2147/IPRP.S63822.

- Bragazzi NL. Pharmacists as immunizers: the role of pharmacies in promoting immunization campaigns and counteracting vaccine hesitancy. Pharmacy (Basel, Switzerland). 2019;7(4):166. doi:10.3390/pharmacy7040166.

- Westrick SC, Patterson BJ, Kader MS, Rashid S, Buck PO, Rothholz MC. National survey of pharmacy-based immunization services. Vaccine. 2018;36(37):5657–64. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2018.07.027.

- Ecarnot F, Crepaldi G, Juvin P, Grabenstein J, Del Giudice G, Tan L, O’Dwyer S, Esposito S, Bosch X, Gavazzi G, et al. Pharmacy-based interventions to increase vaccine uptake: report of a multidisciplinary stakeholders meeting. BMC Public Health. 2019;19(1):1–6. doi:10.1186/s12889-019-8044-y.

- Le LM, Veettil SK, Donaldson D, Kategeaw W, Hutubessy R, Lambach P, Chaiyakunapruk N. The impact of pharmacist involvement on immunization uptake and other outcomes: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Pharm Assoc (2003). 2022;62(5):1499–1513.e16. doi:10.1016/j.japh.2022.06.008.

- Beghi E, Giussani G, Abd-Allah F, Abdela J, Abdelalim A, Abraha HN, Adib MG, Agrawal S, Alahdab F, Awasthi A, et al. Global, regional, and national burden of epilepsy, 1990–2016: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2016. Lancet Neurol. 2019;18(4):357–75. doi:10.1016/S1474-4422(18)30454-X.

- Asmelashe Gelayee D, Binega Mekonnen G, Asrade Atnafe S. Practice and barriers towards provision of health promotion services among community pharmacists in Gondar, Northwest Ethiopia. Biomed Res Int. 2017;2017:7873951. doi:10.1155/2017/7873951.

- Bangura JB, Xiao S, Qiu D, Ouyang F, Chen L. Barriers to childhood immunization in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review. BMC Public Health. 2020;20(1). doi:10.1186/s12889-020-09169-4.

- Asmare G, Madalicho M, Sorsa A. Disparities in full immunization coverage among urban and rural children aged 12-23 months in Southwest Ethiopia: a comparative cross-sectional study. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2022;18(6). doi:10.1080/21645515.2022.2101316.

- Edwards N, Gorman Corsten E, Kiberd M, Bowles S, Isenor J, Slayter K, McNeil S. Pharmacists as immunizers: a survey of community pharmacists’ willingness to administer adult immunizations. Int J Clin Pharm. 2015;37(2):292–5. doi:10.1007/s11096-015-0073-8.

- Valiquette JR, Bédard P. Community pharmacists’ knowledge, beliefs and attitudes towards immunization in Quebec. Can J Public Health. 2015;106(3):e89–e94. doi:10.17269/CJPH.106.4880.

- Scarpitta F, Restivo V, Bono CM, Sannasardo CE, Vella C, Ventura G, Bono S, Palmeri S, Caracci F, Casuccio A, et al. The role of the community pharmacist in promoting vaccinations among general population according to the national vaccination plan 2017-2019: results from a survey in Sicily, Italy. Annali di Igiene Medicina Preventiva e di Comunita. 2019;31(2):25–35. doi:10.7416/ai.2019.2274.

- Yemeke TT, McMillan S, Marciniak MW, Ozawa S. A systematic review of the role of pharmacists in vaccination services in low-and middle-income countries. Res Soc Adm Pharm. 2021;17(2):300–6. doi:10.1016/j.sapharm.2020.03.016.

- Wada YH, Musa MK, Ekpenyong A, Adebisi YA, Musa MB, Khalid GM. Increasing coverage of vaccination by pharmacists in Nigeria; an urgent need. Public Health Pract. 2021;2(May):100148. doi:10.1016/j.puhip.2021.100148.

- Maidment I, Young E, MacPhee M, Booth A, Zaman H, Breen J, Hilton A, Kelly T, Wong G. Rapid realist review of the role of community pharmacy in the public health response to COVID-19. BMJ Open. 2021;11(6):1–14. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2021-050043.

- Santos YS, de Souza Ferreira D, de Oliveira Silva ABM, da Silva Nunes CF, de Souza Oliveira SA, da Silva DT. Global overview of pharmacist and community pharmacy actions to address COVID-19: a scoping review. Expl Res Clin Soc Pharm. 2023;10(December 2022):100261. doi:10.1016/j.rcsop.2023.100261.

- Houle SKD, Timony P, Waite NM, Gauthier A. Identifying vaccination deserts: the availability and distribution of pharmacists with authorization to administer injections in Ontario. Can Pharm J. 2022;155(5):258–66. doi:10.1177/17151635221115183.

- Percy JN, Crain J, Rein L, Hohmeier KC. The impact of a pharmacist-extender training program to improve pneumococcal vaccination rates within a community chain pharmacy. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2020;60(1):39–46. doi:10.1016/j.japh.2019.09.004.

- DeMarco M, Carter C, Houle SKD, Waite NM. The role of pharmacy technicians in vaccination services: a scoping review. J Am Pharm Assn. 2022;62(1):15–26.e11. doi:10.1016/j.japh.2021.09.016.

- Poudel A, Lau ETL, Deldot M, Campbell C, Waite NM, Nissen LM. Pharmacist role in vaccination: evidence and challenges. Vaccine. 2019;37(40):5939–45. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2019.08.060.

- Della Polla G, Napolitano F, Pelullo CP, De Simone C, Lambiase C, Angelillo IF. Investigating knowledge, attitudes, and practices regarding vaccinations of community pharmacists in Italy. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2020;16(10):2422–8. doi:10.1080/21645515.2020.1720441.

- Al Aloola N, Alsaif R, Alhabib H, Alhossan A. Community needs and preferences for community pharmacy immunization services. Vaccine. 2020;38(32):5009–14. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2020.05.060.

- Elayeh E, Akour A, Almadaeen S, AlQhewii T, Basheti IA. Practice of pharmaceutical care in community pharmacies in Jordan. Trop J Pharm Res. 2017;16(2):463–70. doi:10.4314/tjpr.v16i2.27.

- Qamar M, Koh CM, Choi JH, Mazlan NA. Community pharmacist’s knowledge towards the vaccination and their willingness to implement the community-based vaccination service in Malaysia. J Appl Pharm Sci. 2022;12(6):128–39. doi:10.7324/JAPS.2022.120612.

- Merks P, Religioni U, Bilmin K, Lewicki J, Jakubowska M, Waksmundzka-Walczuk A, Czerw A, Barańska A, Bogusz J, Plagens-Rotman K, et al. Readiness and willingness to provide immunization services after pilot vaccination training: a survey among community pharmacists trained and not trained in immunization during the COVID-19 pandemic in Poland. Int J Env Res Pubic Health. 2021;18(2):1–15. doi:10.3390/ijerph18020599.

- Dineen-Griffin S, Benrimoj SI, Garcia-Cardenas V. Primary health care policy and vision for community pharmacy and pharmacists in Australia. Pharm Pract. 2020;18(2):1–12. doi:10.18549/PharmPract.2020.2.1967.

- Goad JA, Taitel MS, Fensterheim LE, Cannon AE. Vaccinations administered during off-clinic hours at a national community pharmacy: implications for increasing patient access and convenience. Ann Fam Med. 2013;11(5):429–36. doi:10.1370/afm.1542.