ABSTRACT

Current COVID-19 vaccination levels are insufficient to achieve herd immunity. To implement effective interventions toward ending the pandemic, it is essential to understand why people are motivated and willing to receive vaccination. The study aims to evaluate attitudes toward COVID-19 vaccination mandates and the impact of policies on future vaccine uptake and behavior utilizing self-determination theory. We conducted an online survey (n = 569) in the U.S. and Turkey to investigate a relationship between respondents’ psychological needs and their willingness and motivation to receive COVID vaccination. The study examined the possible impact of vaccine mandates on these needs. Autonomy satisfaction was the leading predictor of willingness to receive vaccination (p < .0001). Relatedness satisfaction was the leading predictor of one’s intention to receive vaccination (OR = 3.382; p = .0001). The strongest positive correlation was found between needs frustration and external motivation. A moderate positive correlation was found between competence frustration and introjected motivation. No association was found between vaccine mandates and psychological needs. Need satisfaction, especially autonomy and relatedness, appear to positively influence willingness and intention to receive a vaccination. On the other hand, need frustration, especially autonomy and competence frustration, correlates with external motivation, thereby suggesting a detrimental long-term effect on vaccination behavior. Need satisfaction promotes positive vaccination behavior, while need frustration might adversely affect motivation and willingness to receive vaccination. Strategies promoting autonomous decision-making might be more effective than vaccination enforcement in sustaining positive vaccination behavior.

Introduction

A large share of the world’s population needs to obtain immunity to COVID-19 to end the pandemic. The world’s hopes have been pinned on vaccines.Citation1 As of June 1, 2023, 5.58 billion people worldwide have received at least one dose of a COVID-19 vaccine, equal to about 70% of the global population.Citation2 Some of the remaining population, especially those who live in less wealthy countries, did not get vaccinated because of production problems, export bans, and vaccine hoarding by wealthy nations.Citation3

However, some people are disinclined to take the vaccine despite its availability. The most often cited reasons for adults not willing to get vaccinated against COVID-19 are concerns about possible side effects, distrust of the vaccines, distrust of the government, beliefs that vaccines are unnecessary, and the perception that COVID-19 is not a significant threat.Citation4 Further, some vaccinated individuals are reluctant to vaccinate their children. Half of the adult population say they “definitely” will not vaccinate their children under 11 years of age.Citation5 Although this reluctant group is a small part of the population, it has significant implications for achieving herd immunity.

The herd immunity threshold (HIT) for COVID-19 has been challenging to estimate. Scientists have assessed that approximately 70% of the population would need to be vaccinated to achieve herd immunity against the original coronavirus. However, the estimated HIT increased to 80% to 90% for the more contagious Delta variant of COVID-19.Citation6,Citation7 Since vaccination coverage in many places worldwide has remained at much lower levels than the estimated HIT, governments have faced the complex decision of imposing vaccination mandates or using different approaches to increase vaccination coverage.

Vaccine mandates aimed at allowing people to move freely and return to their daily activities have raised concerns about potential violations of individual autonomy and freedom of choice.Citation8 Moreover, previous research found that vaccine mandates might negatively affect attitudes toward vaccination and facilitate negative vaccination behavior.Citation9–13 Since continued vaccination is necessary to achieve herd immunity, vaccine mandate policies need to be analyzed to see if it might have detrimental long-term consequences or increase resistance to vaccination.

Self-determination theory (SDT) presents a broad framework for studying human motivation and personality. Conditions supporting the individual’s experience of autonomy, competence, and relatedness support basic psychological needs, and current literature shows that meeting these needs is essential for adherence to preventive COVID-19 measures. The absence of those conditions, SDT predicts, will have a highly detrimental impact on wellness in this context and has been exemplified by conspiracy theories, lack of motivation, and defensiveness toward vaccination.Citation14,Citation15

Our research replicates a study by Porat and colleagues, who used SDT to investigate the impact of COVID-19 passports on people’s willingness and motivation to receive vaccination in the United Kingdom and Israel, countries with initially the highest COVID-19 vaccine uptake.Citation13 Using population samples from the United States (US), which introduced multiple forms of vaccine mandates, and Turkey, which did not use such instruments, our study results will help enhance the internal and external validity of this previous research. Furthermore, according to the classification of replication study types by The Dutch Research Council, our study is an independent conceptual replication.Citation16,Citation17

The aim of this paper, using SDT, is to assess attitudes toward COVID-19 vaccination mandates and the impact of these policies on vaccine uptake and future vaccination behavior in the US and Turkey. Considering previous researchCitation9–13 on populations in other countries, we hypothesize that psychological needs influence vaccination behavior, motivation, and willingness to vaccinate against COVID-19. Moreover, we expect that vaccine mandates might frustrate psychological needs and thus negatively impact vaccination behavior.

Materials and methods

Design and setting

The study was an online survey conducted via Sogolytics in the US and Turkey.Citation18 Sogolytics, previously known as Sogosurvey, is a cloud-based SaaS platform that enables creation, distribution, and multilingual analysis of surveys. This most frequently used online survey tool provides an end-to-end solution with advanced functionalities designed to engage participants, increase response rates, and analyze trends in the data. Once the survey is created, Sogolytics sends a single-user URL to collect a unique response from each individual. Once the sample size is calculated from power analysis, the data can be downloaded for use in analysis.

Data were collected from August 23, 2021, to April 5, 2022. We selected the US and Turkey for this research because at the time of the study (August 23, 2021), COVID-19 vaccination rates differed despite vaccination availability in both countries (61% of the US population vs. 54% of the Turkish population having received at least one dose of the vaccine).Citation19

Participants

The aim of this study was to generalize to a population without prior vaccination. Therefore, the study population comprises individuals who have not been vaccinated. Of 1000 people invited to participate in the study, 639 respondents completed the study (162 from the US and 477 from Turkey), of which 23 participants from the US and 47 from Turkey failed the attention check and were excluded. Our final sample consisted of 569 participants (139 from the US and 430 from Turkey). All participants were at least 18 years old. Participation was voluntary and unpaid.

Main outcome measures

Psychological need satisfaction and frustration

Twelve items from the Basic Psychological Need Satisfaction and Frustration Scale were adapted to the context of vaccination,Citation20 according to the method outlined in Porat et al.Citation13 For each basic psychological need – autonomy, relatedness, and competency – we asked participants two questions regarding satisfaction and frustration and asked them to rate their responses from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). Internal consistency measures are presented as Cronbach’s alpha coefficients ().

Table 1. Basic psychological needs and their reliability coefficients.

Vaccination behavior

Vaccination behavior was determined by asking participants whether they were vaccinated and, if so, the number of doses they received.

Willingness to receive vaccination

Two questions determined a participant’s willingness to get vaccinated:Citation13 (1) How willing are you [or were you, if already vaccinated] to get vaccinated, on a scale from 1 (not at all willing) to 5 (extremely willing)? and (2) Would you get vaccinated [if not already vaccinated]?

Attitudes toward vaccination mandate

To assess attitudes toward mandatory vaccination, participants were presented with three possible scenarios: (1) full vaccination required for certain activities (e.g., participating in major public events or staying at hotels); (2) full vaccination or a recent negative test to perform activities; (3) mandatory full vaccination for all residents. They were then asked to demonstrate the extent of their support for each scenario. Note that vaccine hesitancy assumes that one is not against others being vaccinated and that they are willing to be tested. People who were unwilling to get vaccinated or tested were not in our sample because the aim was to examine vaccine hesitancy, not testing hesitancy.

Motivations to receive or forgo vaccination

Two questions were asked to measure motivations to get vaccinated/not vaccinated with choices 1 (not at all true) to 7 (very accurate) as in the Treatment Self-Regulation Questionnaire,Citation21,Citation22 according to the method outlined in Porat et al.Citation13 presents the questions and their internal consistency as measured by Cronbach’s alpha.

Table 2. Types of motivation and their reliability coefficientsCitation13.

Demographics

We asked participants to report their age, gender, and education ().

Table 3. Demographics and vaccine status of participants from the US and Turkey.

Statistical analysis

In accordance with the methodology of Porat et al.Citation13 in our primary analysis, we conducted a linear regression with autonomy satisfaction, autonomy frustration, competence satisfaction, competence frustration, relatedness satisfaction, and relatedness frustration as independent variables and people’s willingness to get vaccinated as the outcome variable. Further, we conducted a logistic regression with the same independent variables and dichotomous intention to get vaccinated as the outcome variable.

Power analysis yielded that, for the linear regression model, when we estimate physiological needs and willingness to get vaccinated, we needed the sample sizes of 311, 43, and 20 to detect small, medium, and large effect sizes with a statistical power of 0.80.Citation23 For the logistic regression model of psychological needs and one’s decision to get vaccinated, the sample size needed was 136 for an odds ratio of 0.578 and 35 for an odds ratio of 3.38 with statistical power 0.80.

Results

Demographics, vaccination status, and willingness to receive vaccination

Demographics and vaccine status of the participants from the US and Turkey are displayed in . Among the 39 participants in the US who were unvaccinated, 15% (3.7% of the total US sample) said they intended to get vaccinated. In contrast, 85% (20% of the US sample) said they did not intend to receive vaccination. Of 22 unvaccinated Turkish participants, 73% (3.35% of the total Turkey sample) said they intended to get vaccinated. In contrast, 27% (1.25% of the Turkey sample) said they did not intend to get vaccinated.

However, regarding willingness to receive the vaccine, participants in both countries who had been vaccinated with at least one dose of the vaccine were highly willing to get vaccinated (US: median, 5; mean, 4.29; SD, 1.10; Turkey: median, 5; mean, 4.29; SD, 0.96, respectively). However, among participants who had not yet been vaccinated, participants in both countries were relatively unwilling to do so.

Psychological needs

To assess the relationship between people’s psychological needs and their willingness to receive vaccination, we conducted a linear regression with the six predictive needs ratings. shows that autonomy satisfaction was the top predictor of people’s willingness to receive the vaccine, such that the more they felt a sense of autonomy over the decision to get vaccinated, the more willing they were to receive the vaccine. Autonomy frustration also predicted willingness to receive vaccination. The more people felt coerced to get vaccinated, the less willing they were to do so.

Table 4. Multivariate analysis of psychological needs and willingness to get vaccinated.

To understand the factors associated with the decision to get vaccinated, consistent with the methodology of Porat et al.,Citation13 we conducted logistic regression using the decision whether to get vaccinated as a dichotomous variable. Since our study involved two populations, correlation within each population is accounted for by using multi-level analysis approach. This regression () shows that, among all the frustration and satisfaction measures, relatedness satisfaction most strongly predicted one’s intention to get vaccinated. The more people perceived that the authorities cared about and understand their needs, the more likely they were to indicate an intention to get vaccinated. The relationships established through the analysis support our hypothesis that psychological needs influence people’s willingness and intention to receive the COVID-19 vaccine.

Table 5. Multivariate analysis of psychological needs and one’s decision to get vaccinated.

Self-determination theory suggests that frustration (i.e., dissatisfaction of needs) is related to four types of motivation: identified, introjected, external, and amotivation. In identified motivation, a person is motivated by seeing the value and importance of the activity they are completing. Introjected motivation is driven by avoiding guilt, shame, or anxiety. External motivation is driven by external rewards and amotivation happens when a person lacks any motivation or interest in a task and may not even understand why they are doing it. Moreover, behavior that is motivated by self-determined/internal motivation has the most potential to be sustained over time.Citation24 Thus, we sought to investigate how frustration around vaccination might affect motivation to receive vaccination in the US and Turkey. These correlations are shown in .

Table 6. Correlations between need frustration and motivation.

We found that across all the needs, need frustration was positively correlated with all motivation types. However, the magnitude of correlations varied. We observed the strongest correlation between all three psychological needs frustration and external motivation. Thus, those with frustrated psychological needs tended to experience more external motivation to get vaccinated. Moderate correlation was also found between competence frustration and introjected motivation. The more people’s competence need was frustrated, the more their motivation was driven by avoiding guilt, shame, or anxiety. Moreover, a weak correlation was found between autonomy frustration and introjected motivation as well as between competence and relatedness frustration and amotivation.

Our findings suggest that need satisfaction is associated with an increased willingness to get vaccinated. However, need frustration is linked to decreased willingness to vaccinate and shifts motivation from self-determined to external motivation and to amotivation. Hence, vaccine mandates that may frustrate psychological needs and are an external motivator for vaccination might have a negative effect on vaccination behavior ().

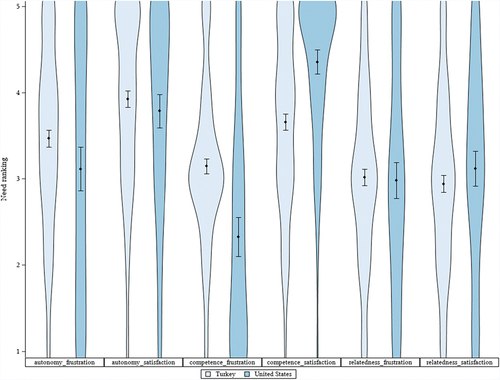

Figure 1. Violin plot displaying the distributions of participants’ need satisfaction and frustration ratings.

Our results show that autonomy frustration was higher in Turkey (). However, the most significant difference between the two countries was found in competence satisfaction and frustration. Competence satisfaction was markedly higher in the US, and competence frustration was significantly higher in Turkey. These findings do not support our hypothesis that vaccine mandates might frustrate psychological needs.

Discussion

We used a sample of 569 participants from the US and Turkey to investigate the relationship between psychological needs and willingness and motivation to get vaccinated against COVID-19. Our findings suggest that need satisfaction, especially autonomy and relatedness satisfaction, positively influences willingness and intention to get vaccinated. However, need frustration, especially autonomy and competence frustration, shifts motivation from autonomous to external motivation and amotivation and is associated with decreased willingness to get vaccinated.

According to the SDT, three psychological needs (autonomy, competence, and relatedness) are critical in improving health. That is because satisfying these needs promotes engagement in self-motivated activities, leading to positive changes in health behavior. Moreover, autonomously motivated behavior tends to be sustained over time because a person engages in it for its own sake, whereas people motivated by external rewards experience difficulties initiating the behavior change and sustaining it over time.Citation15,Citation25,Citation26 Therefore, our results support the evidence that need satisfaction promotes positive vaccination behavior. Moreover, need frustration that is correlated with external motivation might negatively affect vaccination behavior over an extended period of time. These findings corroborate the findings of Porat et al.Citation13

However, our analysis yielded different findings regarding the impact of vaccine mandates on psychological needs. According to Porat et al.,Citation13 vaccine passports might frustrate psychological needs and therefore negatively affect willingness and intention to get vaccinated with the COVID-19 vaccine. Yet, the comparison of the US and Turkey samples did not provide evidence supporting this statement; instead, higher need frustration was observed in Turkey, the country without vaccine mandates.

Moreover, this finding was the most evident for competence and autonomy frustration, suggesting that people in Turkey felt more pressure than those in the US to get vaccinated and were less able to get vaccinated if they wanted to do so. This greater autonomy and competence frustration among participants in Turkey might explain the lower COVID-19 vaccine uptake in that country. Further, we found that autonomy satisfaction was relatively high in both countries and slightly higher in Turkey. These findings suggest that even though Turkish residents felt more pressured to receive the COVID-19 vaccine than their US counterparts, they also felt more autonomy over the vaccination decision, which may seem contradictory.

Various reasons may explain the differences between the two countries. Cultural and social differences, different vaccine campaigns and distribution strategies, social and governmental pressure, health communications, and other circumstances can impact the need frustration and satisfaction. Campaigns such as “vaccination persuasion,” a door-to-door initiative introduced in Turkey to target elderly people reluctant to take the COVID-19 vaccine, might have contributed to the elevated autonomy frustration.Citation27

Limitations

Since this study is observational, the causal link between psychological needs and willingness to vaccinate cannot be established. Moreover, the study samples were relatively small and may not represent the entire population of the researched countries.

Since the sample sizes for each country were small, we decided to pool the population for multivariable analysis. To control for the differences in characteristics between the two countries, we used a country flag in the multivariable analysis. This assumes that the effect of explanatory variables that we controlled in the regression is same in both countries. For example, as discussed above, to the extent that the effect of education levels on vaccination status is different in different countries, our estimates would be biased.

Additionally, the US did not implement a uniform vaccine mandate policy. Even though the majority of respondents were residents of New York City, a city with one of the world’s most stringent vaccine mandate policies, a share of participants resided outside of New York State, where the policies were more lenient than in New York City. Therefore, the comparison of Turkey and US samples did not reflect a comparison of a country strictly with vaccine mandates and one without them.

Moreover, as with the previous study by Porat et al.Citation13 this study only analyzed data from developed, democratic countries and evaluated only domestic vaccine mandates. Therefore, it is necessary to investigate whether our findings apply to other countries and cultures, or to vaccine passport policies directed to international travel.

Conclusions

While need satisfaction promotes positive vaccination behavior, need frustration has a negative impact on one’s willingness and intention to receive the COVID-19 vaccine. Moreover, need frustration correlates with external motivation. Autonomy can be supported in various ways by the government and care providers. Governments can create an autonomy-supportive environment by letting individuals feel they are cared for, acknowledging their emotions, and considering their perspective. Campaigns providing reliable and sufficient information about vaccination that could help people make informed and autonomous decisions might prove to be more effective in sustaining positive vaccination behavior over time than external motivations such as vaccination enforcement.

Author contributions

O.B. supervised the study and developed the study’s conceptualization, methodology, validation, investigation, resources; K.R. administered the project and participated in investigation and writing the draft; L.C. participated in software application, formal analysis, validation, and data curation; and N.Y. participated in software application, formal analysis, validation, and data curation. We acknowledge Amy Endrizal for writing and editing assistance.

Informed consent statement

Informed consent was not required as the data were from an anonymous, de-identified database compliant with HIPAA.

Institutional review board

Ethics approvals were not required as the data were from an anonymous, de-identified database compliant with HIPAA.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

Data are not available due to privacy and ethical restrictions.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Viana J, van Dorp CH, Nunes A, Gomes MC, van Boven M, Kretzschmar ME, Veldhoen M, Rozhnova G. Controlling the pandemic during the SARS-CoV-2 vaccination rollout. Nat Commun. 2021;12(1):3674. doi:10.1038/s41467-021-23938-8.

- Yalcin TY, Topcu DI, Dogan O, Aydın S, Sarı N, Erol Ç, Kuloğlu ZE, Azap ÖK, Can F, Arslan H. Immunogenicity after two doses of inactivated virus vaccine in healthcare workers with and without previous COVID-19 infection: prospective observational study. J Med Virol. 2022 Jan;94(1):279–7. doi:10.1002/jmv.27316.

- Ahlberg BM, Bradby H. Ethnic, racial and regional inequalities in access to COVID-19 vaccine, testing and hospitalization: implications for eradication of the pandemic. Front Sociol. 2022;7:809090. doi:10.3389/fsoc.2022.809090.

- Agaku I, Adeoye C, Krow NAA, Long T. Segmentation analysis of the unvaccinated US adult population 2 years into the COVID-19 pandemic, 1 December 2021 to 7 February 2022. Fam Med Cmty Health. 2023 Feb;11(1):e001769. doi:10.1136/fmch-2022-001769.

- Sparks G, Lopez L, Hamel L, Montero A, Presiado M, Brodie M. KFF COVID-19 vaccine monitor: September 2022; [accessed 2023 Jun 2]. https://www.kff.org/coronavirus-covid-19/poll-finding/kff-covid-19-vaccine-monitor-september-2022/.

- García-García D, Morales E, Fonfría ES, Vigo I, Bordehore C. Caveats on COVID-19 herd immunity threshold: the Spain case. Sci Rep. 2022 Dec 1;12(1):598. doi:10.1038/s41598-021-04440-z.

- McNamara D. Delta variant could drive ‘herd immunity’ threshold over 80%; Updated Aug 3 [accessed 2022 Apr 26]. https://www.webmd.com/lung/news/20210803/delta-variant-could-drive-herd-immunity-threshold-over-80.

- Rieger T, Schmidt-Petri C, Schröder C. Attitudes toward mandatory COVID-19 vaccination in Germany—a representative analysis of data from the socio-economic panel for the Year 2021. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2022 May 13. Forthcoming. doi:10.3238/arztebl.m2022.0174.

- Graeber D, Schmidt-Petri C, Schröder C, Capraro V. Attitudes on voluntary and mandatory vaccination against COVID-19: evidence from Germany. PLoS ONE. 2021;16(5):e0248372–e0248372. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0248372.

- Betsch C, Böhm R. Detrimental effects of introducing partial compulsory vaccination: experimental evidence. Eur J Public Health. 2016 Jun;26(3):378–81. doi:10.1093/eurpub/ckv154.

- Bell S, Clarke RM, Ismail SA, Ojo-Aromokudu O, Naqvi H, Coghill Y, Donovan H, Letley L, Paterson P, Mounier-Jack S, et al. COVID-19 vaccination beliefs, attitudes, and behaviours among health and social care workers in the UK: a mixed-methods study. PLoS ONE. 2022;17(1):e0260949–e0260949. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0260949.

- Sprengholz P, Betsch C, Böhm R. Reactance revisited: consequences of mandatory and scarce vaccination in the case of COVID‐19. Appl Psychol Health Well Being. 2021;13(4):986–995. doi:10.1111/aphw.12285.

- Porat T, Burnell R, Calvo RA, Ford E, Paudyal P, Baxter WL, Parush A. “Vaccine passports” May Backfire: findings from a cross-sectional study in the UK and Israel on willingness to get vaccinated against COVID-19. Vaccines (Basel). 2021;9(8):902. doi:10.3390/vaccines9080902.

- University of Rochester Medical Center. Self-determination theory. Our Approach; [accessed 2022 Aug 10]. https://www.urmc.rochester.edu/community-health/patient-care/self-determination-theory.aspx.

- Flannery M. Self-determination theory: intrinsic motivation and behavioral change. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2017 Mar 1;44(2):155–156. doi:10.1188/17.Onf.155-156.

- The Dutch Research Council (NWO). Replication studies. https://www.nwo.nl/en/researchprogrammes/replication-studies.

- Peels R. Replicability and replication in the humanities. Res Integr Peer Rev. 2019 Sep 1;4(1):2. doi:10.1186/s41073-018-0060-4.

- Design engaging surveys in minutes. [accessed 2023 Jun 2]. https://www.sogolytics.com/online-survey-tool/?utm_source=google&utm_medium=cpc&campaign=8624657474&adgrp=88438208764&keyword=sogolytics&mtype=p&adpos=618782241061&network=g&a&camp=&gclid=CjwKCAjwpuajBhBpEiwA_ZtfhV8xb749anHLqUL87MQSt-OQmaK8LCo_BWw2Ko5Y-DDzybOM72KOrRoCzVQQAvD_BwE.

- Our World in Data. Coronavirus (Covid-19) vaccinations. Updated Jun 1 [ accessed 2023 June 2]. https://ourworldindata.org/covid-vaccinations.

- Chen B, Vansteenkiste M, Beyers W, Boone L, Deci EL, Van der Kaap-Deeder J, Duriez B, Lens W, Matos L, Mouratidis A, et al. Basic psychological need satisfaction, need frustration, and need strength across four cultures. Motiv Emot. 2015 Jan 4;39(2):216–236. doi:10.1007/s11031-014-9450-1.

- Ryan RM, Connell JP. Perceived locus of causality and internalization: examining reasons for acting in two domains. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1989 Nov;57(5):749–61. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.57.5.749.

- Levesque CS, Williams GC, Elliot D, Pickering MA, Bodenhamer B, Finley PJ. Validating the theoretical structure of the treatment self-regulation questionnaire (TSRQ) across three different health behaviors. Health Educ Res. 2006;22(5):691–702. doi:10.1093/her/cyl148.

- Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. 2nd ed. Routledge; 1988.

- Ryan RM, Deci EL. Intrinsic and extrinsic motivations: classic definitions and new directions. Contemp Educ Psychol. 2000 Jan;25(1):54–67. doi:10.1006/ceps.1999.1020.

- Lourenço J, Almagro BJ, Carmona-Márquez J, Sáenz-López P. Predicting perceived sport performance via self-determination theory. Percept Mot Skills. 2022 Oct;129(5):1563–80. doi:10.1177/00315125221119121.

- Ntoumanis N, Ng JYY, Prestwich A, Quested E, Hancox JE, Thøgersen-Ntoumani C, Deci EL, Ryan RM, Lonsdale C, Williams GC. A meta-analysis of self-determination theory-informed intervention studies in the health domain: effects on motivation, health behavior, physical, and psychological health. Health Psychology Review. 2021 Jun;15(2):214–244. doi:10.1080/17437199.2020.1718529.

- McKernan B, Saraçoğlu G. Covid ‘vaccination persuasion’ teams reap rewards in Turkey. The Guardian. Apr 27 [accessed 2023 Jun 9]. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2021/apr/27/covid-vaccination-persuasion-teams-reap-rewards-in-turkey.