ABSTRACT

There is a continued need for research to better understand the influence social media has on parental vaccination attitudes and behaviors, especially research capturing the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic. The goal of this study was to explore parents’ perspectives related to the impact the pandemic had on 1) social media engagement, 2) vaccine messaging on social media, and 3) factors to guide future intervention development. Between February and March 2022, 6 online, synchronous, text-based focus groups were conducted with parents of adolescents aged 11 to 17 years. Participants who all utilized social media were recruited from across the United States. Qualitative data were analyzed using content analysis. A total of 64 parents participated. Average age was 47 years, and participants were predominantly White (71.9%), female (84.3%), and engaged with social media multiple times per day (51.6%). Participants (95.3%) viewed obtaining all recommended vaccines as important or very important; however, overall vaccination rates for their adolescents were varied (50% ≥1 dose HPV; 59.4% MenACWY; 78.1% Tdap; 65.6% Flu; 81.3% COVID-19). Three themes emerged highlighting the pandemic’s impact on parent’s (1) general patterns of social media use, (2) engagement about vaccines on social media and off-line behaviors related to vaccination, and (3) perspectives for developing a credible and trustworthy social media intervention about vaccination. Participants reported fatigue from contentious vaccine-related content on social media and desired future messaging to be from recognizable health institutions/associations with links to reputable resources. Plus, providers should continue to provide strong vaccine recommendations in clinic.

Introduction

Vaccination has been noted as one of the greatest public health achievements and one of the most significant contributions to improved health of children in the 20th century.Citation1,Citation2 However, in 2019, the World Health Organization identified vaccine hesitancy as one of the ten leading threats to global health.Citation3 In the United States (US), the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) currently recommends that all adolescents aged 11–12 years routinely receive four vaccines: the tetanus- diphtheria-acellular pertussis vaccine (Tdap), quadrivalent meningococcal conjugate vaccine (MenACWY), human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine, and seasonal influenza vaccine.Citation4,Citation5 For adolescents aged 16–18 years, ACIP routinely recommends the second dose of MenACWY and issued a shared clinical decision making (SCDM) recommendation for meningococcal B (MenB) vaccine. Plus, in 2023, the ACIP added the COVID-19 vaccine to the list of routinely recommended vaccines for all adolescents.Citation6 However, despite strong professional guidelines and the great potential prevention benefits, US national data indicate that many adolescents do not receive recommended vaccinations.

While coverage for Tdap and the first dose of MenACWY exceed the US Healthy People 2030 goal of 80% coverage,Citation7 other adolescent vaccines do not fare as well, reflecting, in part, parental vaccine hesitancy or a lack of confidence in vaccination. Data from the 2021 National Immunization Survey-Teen (NIS-Teen) showed that among adolescents aged 13–17 years, HPV vaccine series completion (61.7%) was well below the Healthy People 2030 goal of 80% series completion.Citation8 Similarly, NIS-Teen data show that the recommended second dose of MenACWY is only at 60.0% coverage and MenB administration is at 31.4%.Citation8 With respect to influenza vaccination, only 49.8% of adolescents aged 13–17 years received annual influenza vaccination for the 2021–2022 season,Citation9 well below the Healthy People 2030 goal of 70%.Citation7 The low coverage of these adolescent vaccines has significant implications for adolescent and young adult health now and in the future.

While strong healthcare provider recommendations increase vaccine acceptance among parents,Citation10–12 there is evidence that effective provider recommendations are underutilized, and that other influences, including social media and other online health information, also play an important role in parental vaccine decision making.Citation13 Ample evidence suggests that negative messages about vaccination abound on social media,Citation14–19 and the COVID-19 pandemic exacerbated the negative rhetoric.Citation20 Although it is known that parents receive health information via social media and that message framing can have profound effects on parent vaccination attitudes and behaviors,Citation21,Citation22 there is a continuing need for research to better understand how vaccine messaging on social media, particularly since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, may influence parental vaccine confidence and decision making.

Previous reports indicate links between social media use, political leanings, and education level with an individual’s ability to identify misinformation, trust vaccines, trust vaccine messaging, and engage in vaccine decision making.Citation23,Citation24 Additionally, vaccination status has been shown to influence social media interactions with vaccine posts (i.e., mothers posting unfavorable HPV vaccine comments were less likely to have vaccinated their daughter),Citation25 and negative messaging on media contributes to vaccine hesitancy and decisions to delay vaccination.Citation18 Social media effects on vaccine confidence have been identified as a priority area for vaccination research in the US.Citation26 Research that directly supports evidenced-based vaccine communication/messaging interventions on social media is sorely needed.

Therefore, the overall goal of this study was to explore parent’s perspectives related to the impact the COVID-19 pandemic had on 1) their social media engagement, 2) vaccine messaging on social media, and 3) factors related to messaging influence (credibility and trustworthiness). In addition, we sought to garner opinions related to the development of future social media vaccine messaging interventions to increase vaccine confidence and acceptance. Data were collected in February and March of 2022, approximately 2 years after the start of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Materials and methods

Procedures and study population

A qualitative, descriptive study using an online synchronous text-based focus group methodology (6 focus groups, each 60 to 90 min, 9 to 15 participants per group) was conducted using a US national purposive sample. Members of the investigative team have a record of success using this methodology to provide robust data, particularly for topics that are sensitive or difficult to discuss face to face.Citation27–31 Eligibility criteria included: 1) parent or primary caregiver of an adolescent aged 11 to 17 years, 2) ability to read English, 3) access to a computer/tablet with internet access, and 4) utilization of at least one form of social media. Lastly, we sought to capture a diversity of vaccination perspectives/attitudes (vaccine cautious to vaccine confident). Therefore, participants were recruited if they had obtained at least one CDC ACIP recommended adolescent vaccine for their child. We also focused on recruiting mothers/female caregivers as they are often the primary caregiver present at health care visits, and women have been known to have higher rates of social media utilization as compared to men.Citation32 Those who had not obtained any of adolescent vaccinations for their child were presumed to have negative attitudes toward all childhood vaccination and were thus excluded from this study.

Potential participants were recruited from an existing online US national panel of persons who have agreed to engage in research managed by InsideHeads, LLC, an experienced marketing research company. This panel provides the ability to reach quality large samples for online qualitative studies in a timely manner. Potential participants were contacted by InsideHeads and if interested they were provided additional study information. Once participants were willing to engage they were provided a copy of the informed consent and given instructions on how to attend the online focus group (e.g., date, time, login instructions). As participants joined the discussion platform they were automatically and randomly assigned pseudonyms. After participants were welcomed to the discussion, they were provided a separate link to complete the online consent and demographic survey (via Qualtrics). Once all consents were obtained, the text-based, interactive, synchronous discussion occurred with each participant on their own computer in a place of their choosing. Participants actively engaged online with the moderator (the principle investigator) and other participants by typing comments, thoughts, and beliefs, and responding to others’ posts (text-based discussions are like ‘blogs,’ participants could not view each other and no verbal exchange occurred). Investigators were able to substitute brief agreement and disagreement of typed comments as non-verbal cues during the discussions (i.e., participants used “☺” as positive feedback to others posts) and compiled detailed field notes after each discussion. All data collected remained anonymous and de-identified. InsideHeads directly remunerated their panel members (study participants) with a $75 gift card. Study protocol and procedures were approved by the University of Hawaii at Manoa Institutional Review Board June 9, 2021.

Measures

Descriptive socio-demographic quantitative data included age, gender, race/ethnicity, state/US region, level of education, employment status, health insurance status, and relationship status. We also assessed perceived level of importance for their child/children obtaining all recommended vaccines as well as their child’s vaccine status. Lastly, we collected data on rate and type of social media utilization.

A semi-structured discussion guide was utilized to collect qualitative data (Supplemental Table S1). We queried participants about their thoughts and behaviors related to social media utilization, the type of information they view or engage with related to vaccines, how they determine credibility of information and trustworthiness of sources, how they process and engage with both negative and positive information about vaccines, and their views related to social messaging influence on their decisions about vaccination for their child/children. We also elicited the COVID-19 pandemic’s influence on their social media use and content associated with vaccination.

Analysis

Quantitative data were downloaded to Microsoft Excel for management and analysis. Descriptive analyses included mean and standard deviation for the one continuous variable (age) and percentages for all nominal data. Qualitative (typed) data was downloaded from the secure discussion platform in Microsoft Word, and then was uploaded into Microsoft Excel for qualitative management (coding). Due to the nature of the data collected and goals of the study, content analysis was used to objectively engage with the data and to identify the final thematic categories.Citation33 The principal investigator along with two research team members, all experienced in qualitative research, independently immersed themselves in the data, reviewing each transcript along with field notes. Investigators met to discuss the emerging codes, concepts, and develop the final code book. The data were independently coded by the principal investigator and one team member. Throughout the coding process, the entire analysis team (three team members) met to assess accuracy across coders, examine relationships in the data, and refine codes. Whenever conflicting interpretations occurred discussion ensued until consensus was reached. Coded data was collapsed into broader categories and reexamination led to the development of the final themes and sub-themes.

Results

Socio-demographics and social media utilization

A total of 64 parents/caregivers of adolescents aged 11 to 17 years participated (see ). The average age was 47.1 years and the majority (84.3%) identified as female. The racial/ethnic demographics were 71.9% White, 12.5% Black, 6.3% Asian, and 7.8% identified as another race or more than one race. Approximately one-third (34.4%) identified as Hispanic. Participants were primarily college educated (76.6%), employed full time (71.8%), married/partnered (84.3%), and had private health insurance (65.6%). Most viewed having their child/children receive all recommended vaccines as “very important” (60.9%) or “important” (34.4%); however, when queried specifically, in this purposely diverse sample of vaccine acceptors, only 50% had obtained HPV, 59.4% MenACWY, and 78.1% Tdap vaccines for their adolescent. Interestingly, 81.3% indicated their adolescent received the COVID-19 vaccine and 65.6% noted obtaining the Flu vaccine.

Table 1. Sociodemographic characteristics of the sample (N = 64).

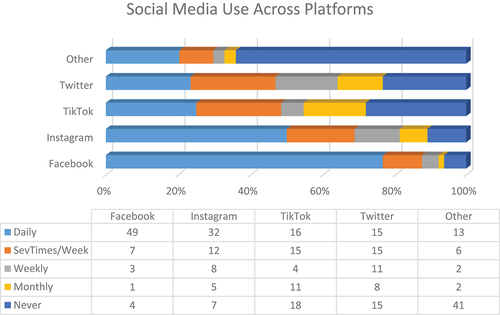

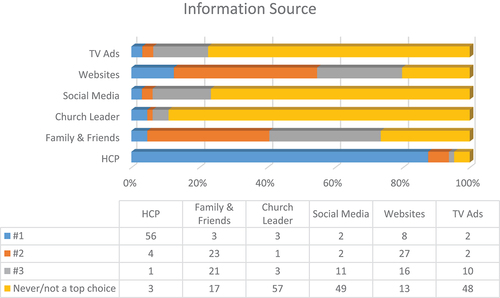

The rate of social media use was high among participants. Over half (51.6%) indicated engaging with social media multiple times per day and 35.9% indicated daily use (). highlights the rate of social media use across platforms. The majority (76.5%) indicated daily Facebook use, 50% indicated daily Instagram use, followed by TikTok (25%) and Twitter (23.4%). highlights the preferred sources for health care information and health care providers were overwhelmingly (87.5%) the preferred source of information. Other top ranked preferred sources included: websites (42.2%) and friends and family (35.9%). Conversely, social media (76.6%), church leaders (89.1%), and television advertisements (75%) were predominantly noted as “never/not a top choice.”

Qualitative analysis

Three common themes emerged from the qualitative data: (1) the pandemic’s impact on parent’s general patterns of social media use; (2) the pandemic’s impact on parental engagement about vaccines on social media as well as off-line behaviors related to vaccination; and (3) perspectives for developing a credible and trustworthy social media intervention about vaccination in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic. See for illustrative quotes by theme.

Table 2. Illustrative quotes.

Pandemic’s impact on parents’ general patterns of social media use

Most participants stated that their social media habits changed over the course of the pandemic. The slight majority said they used social media less now than at the start of the pandemic. Participants who used it less expressed exasperation with negativity and polarization. One said, “I’m done with the constant panic and fear … Not just the pandemic but EVERYTHING is negative” [female (F), age 43]. Those who reported using social media more often indicated that it was because they had more free time or because “it was a way to stay connected with others when we couldn’t do so in person” (F, age 48). A subgroup discussed their experience with both the impulse to stay connected, as well as the frustration with bitter disagreements: “My contact on FB [Facebook] became less and less. Initially I took to social media more to lessen the isolation of the pandemic. I found myself agitated with much of the ignorance [related to vaccine and health topics],” said one participant (F, age 49). The frustration with the negativity encountered online led many to use social media more passively (only reading or browsing but not posting or making comments to posts).

By far, most participants said they only used social media for lighthearted purposes: posting pictures of family and friends, pets, food, or fun memes. One said “I post humorous things. The world needs some happiness and good news right now. And [to see] pretty food I’ve made or am eating lol” (F, age 43). Most were wary about getting involved with “the ugliness” (F, age 43) surrounding contentious issues and wanted to avoid fights or persecution for their beliefs. “Social media has become a landmine field of dissention and bickering, so I am limiting my time there. I seldom repost [or] comment and if I do it’s something very inoffensive. Never political or vulgar,” explained a participant (F, age 56). However, if the content was uplifting or funny, then people were highly motivated to post or repost.

Pandemic’s impact on parental engagement about vaccines on social media and off-line behaviors related to vaccination

Just as the pandemic affected general social media behaviors, it also affected people’s online and offline engagement, attitudes, and behaviors related to vaccination. When asked about routine adolescent vaccines, participants repetitively brought the conversation back to discussing COVID-19 vaccines and the associated rhetoric.

The negative information people saw related to vaccines (largely COVID-19 vaccine related) ranged from what they described as conspiracy theories to concerns about side effects. Participants identified what they believed to be misinformation, which included: the link between vaccines and autism, the belief vaccines are fatal, and that the COVID-19 vaccine is not actually a vaccine. A few also noted viewing messages that they felt misconstrued incidence and severity of common side effects or rare adverse events. For example, one said “[I have seen] how healthy young people are suddenly dying of heart problems [post-vaccine]. Mostly in FB [Facebook] groups of people that are anti-vaccine” (F, age 53) in reference to rare incidents of myocarditis and pericarditis following COVID-19 vaccine administration. However, most participants noted that they did not view negative information as credible or trustworthy. Negative vaccine information was often described as opinionated, irrational, and not based on facts and participants were skeptical of the sources that disseminated negative information. As a result, many participants said they ignored the negative information. Still, some did relay that at least some of the negative vaccine information caused concern or gave them pause: “I didn’t view negative [information] as trustworthy or not because I didn’t know the facts. It was more food for thought,” (F, age 34) and “I didn’t necessarily believe the [negative] information was credible, but I was concerned enough about it – because it involved my child – to ask her pediatrician” (F, age 56).

The positive vaccine information participants viewed on social media was described as more straightforward in its messages. Participants noted that they read how the COVID-19 vaccines were helping lower the number of new infections, that if a vaccinated person was infected with COVID-19 the illness was more likely to be mild, and that vaccines protect oneself and the people around them. Participants described the positive information as credible and trustworthy. A crucial part of why participants found the positive information credible was the source and the neutrality of its presentation.

Engaging in discussions about vaccination (of any type, including routine and school required vaccines) online was described as political and almost taboo, and again participants noted concerns related to hostility, persecution, and simple futility. One described how they were “instantly sent hostile messages for a week or so” (F, age 42) after posting their views on vaccination. As a result, they said they have ceased to post their vaccine opinion. One stated, that they did not post on “[all matters] of any merit anymore” (F, age 42). Only a small minority were willing to discuss health and vaccines online.

Participants noted that their choices for obtaining routinely recommended vaccines for their adolescent were largely unchanged from the beginning of the pandemic. One stated, “I have always believed in vaccines all along. My kids are all up to date with recommended immunizations. COVID or no COVID, we stand with vaccines” (F, age 41). A few did note how the online rhetoric changed their minds about obtaining routinely recommended vaccines for their adolescent; however, the numbers of participants who were more likely to vaccinate and/or less likely to vaccinate were nearly equal. Participants who were more likely to vaccinate expressed concern for their family’s safety: “[COVID-19] made me make sure [my] kid is safe” [male (M), age 43] thereby increasing uptake for all routinely recommended vaccines for their adolescent, including HPV and influenza. Those who said they were now less likely to obtain routine vaccinations expressed a myriad of concerns related to side effects, government distrust, perceived lack of vaccine efficacy, and vaccine development. One said, “I never had any doubts prior. Some doubts have creeped in. People always say they know someone who has had complications or side effects” (M, age 49).

Perspectives for developing a credible and trustworthy social media intervention regarding vaccination in the wake of COVID-19 pandemic

Participants’ discussions about future social media vaccine interventions focused on their viewpoints related to how they determine if information they view on social media is credible and from a trustworthy source. Nearly all participants expressed that information obtained from social media was credible if it included data and statistics and was “information from scientists and researchers” (F, age 51), or “information universally accepted […] by experts” (M, age 49). Trustworthy sources included the CDC, World Health Organization, US Food and Drug Administration (FDA), a health care provider, or a local health system/center or health department. For a source to be considered trustworthy, one stated “It would have to come from an official government source. Like a post from the CDC” (M, age 49).

Participants had mixed beliefs related to following or obtaining vaccine information from a primary health care provider (PCP) on social media. While nearly all participants viewed PCPs as trustworthy, “[My PCP] is my first source [of information]” (F, age 38), only a few noted that they would follow or engage with their PCP on social media. They described that following their PCP on social media felt too intrusive into their personal lives or “weird” (F, age 38) to engage directly with their PCP on social media. But, on the whole participants were supportive of following a professional healthcare organization’s or their health clinic/health center’s social media page and/or a highly visible public figure who may also be a respected health care provider. One stated, “I would prefer [information] from a public site. Not a clinicians private account” (M, age 49).

Despite the majority consensus that credible information was scientific and originated from a reputable medical source, the degree of confidence participants described in their ability to discern credible information ranged from low to high. Plus, while infographics, videos, and other visual aids assist in the accessibility of the information participants noted these visual aids did not influence credibility as they could depict misinformation. Participants who rated their ability to distinguish credible information as low or moderate acknowledged the difficulty in sorting through the abundance of information and misinformation on social media. This led to skepticism for all information, “I usually don’t trust anything on social media because a lot of people repost things without thinking about how true they are” (F, age 34). In general, participants felt that if social media posts contained a link to the source for the information this was helpful because they could then independently check the source and determine if it was legitimate. Many participants used the term doing their “own research” (F, age 31) to describe the ways in which they would try to determine credibility and independently verify what they had learned on social media. Participants clearly noted that any future vaccine campaign should share links to where they could go to learn more and validate what they have read about vaccines online.

Lastly, health messages that participants said influenced them most were a mix of anecdotes/storytelling (narrative messages) and scientific results (non-narrative messages), but these messages needed to adhere to the above criteria for credibility/trustworthiness. For example, one said, “The messages that are scientifically based promote a sense of motivation” (F, age 49), while another said, “I saw personal stories of people dying of the disease [related to COVID-19], [and] I made a decision that I would do whatever it took to prevent that from happening to me” (F, age 48). The storytelling was powerful, but participants always returned to the importance of social media interventions/campaigns providing links to original sources of information so they could read and learn more independently.

Discussion

Much of the research related to the influence of social media on routinely recommended adolescent vaccination was conducted before the COVID-19 pandemic. The public health measures that were implemented to mitigate the spread of COVID-19 such as stay-at-home orders, quarantines, and the closure of businesses and public centers may have led many people to spend more time at home using social media.Citation34 Furthermore, the COVID-19 pandemic fueled the public conversation around public health, viruses, and vaccinations. One might expect the social media behaviors and vaccine attitudes/behaviors to shift as a result of these significant lifestyle changes. Timing of this study captured the pandemic’s impact on general patterns of social media use and engagement about vaccines on social media. Plus, the study helped to provide insights for designing new interventions about vaccination that would be credible and trustworthy in the post-pandemic period.

A combined 87% of participants indicated they use social media “multiple times per day” or “daily.” Most participants stated that their social media habits changed over the course of the pandemic, with a slight majority noting less use. The negativity and hostility of social media were the predominate reasons motivating participants to reduce their social media engagement. When queried about the type of posts they share or engage with, the majority stated they almost exclusively make lighthearted posts, such as jokes, pictures of family, or recipes. Participants were wary of getting involved in any discussions about health or vaccines for fear of judgment and verbal attacks or wanting to avoid futile arguments. Interestingly, some participants noted a more passive engagement, that is, viewing but not posting or commenting. However, whether or not passive engagement has increased as a result COVID-19, the majority of participants in this study were not interested in making posts or participating in discussions online related to health and/or vaccines.

Similar to this study, recent reports have also documented the proliferation of negative information and misinformation on social media about vaccines, particularly on Facebook.Citation14,Citation18,Citation35 Others have described how the significant proliferation of anti-vaccine sentiment on social media has increased hesitancy, potentially leading parents opting out of vaccinations for themselves or their children.Citation14,Citation36–39 In our sample, most viewed the positive messaging about vaccines to be credible, but not the negative messaging. This is important to note as other reports have found that negative messages are more likely to have more ‘likes’ or views.Citation19 Taken together, this may indicate that negative messages about vaccination on social media, while not necessarily believed, may be sufficient to confuse and cast doubt for parents as they make vaccine decisions. In this study many described this skepticism and wanted to be provided with links to reputable resources so that they can independently learn more, form their own conclusions, and then seek the advice of their PCP.

Additionally, vaccine hesitancy may coexist with vaccine uptake, whereby a recommendation from PCPs strongly predicts the decision to vaccinate, but media exposure to vaccine negative messages results in persistent vaccine hesitancy.Citation18 This may explain why participants preferred to discuss vaccination and clear up misinformation with their PCP, but some may retain lingering concerns about their decision to vaccinate even when provided evidence-based information. Determining what is legitimate health information on social media presents a significant challenge for parents/caregivers as negative messaging (including mis- or dis-information) is both more prevalent and spreads more quickly than positive messaging.Citation35,Citation38,Citation40

Nearly all (95%) participants in this study viewed having their children up to date on all routinely recommended adolescent vaccines as “very important” or “important,” yet this did not align with the reported adolescent vaccination rates (i.e., only 50% reported ≥ 1 HPV vaccine dose and 59.4% reported obtaining the MenACWY). It is possible that accurate recall of vaccines administered may have been influenced by the salience of the vaccine (e.g., COVID-19 vaccination experiences may have been more memorable than routine vaccination for MenACWY). Also, during the pandemic, routine adolescent vaccination rates declined and besides the potential effect of negative rhetoric on social media, other barriers to accessing health care existed.Citation41–43 For example, many offices around the US were closed at various times, there was an increase in virtual health care, people may have feared returning to health care settings (due to risk of exposure), and with the shift to online learning for students many schools loosened vaccine requirements.Citation44,Citation45

In this study, the majority indicated that they were pro-vaccine prior to the pandemic and have remained pro-vaccine. However, a noteworthy minority did change their attitudes about vaccination over the course of the pandemic, with the number of those who were more likely to vaccinate equaling the number who became less likely to vaccinate. So, while our sample indicates there was little net change in the number of parents willing to obtain routine vaccines for their children, the myriad effects of the pandemic did have an influence on parental vaccine decision making and should be explored further.

Finally, although the discussion questions were designed to investigate parents’ attitudes and behaviors regarding all routinely recommended adolescent vaccines, it was difficult for participants not to discuss the COVID-19 vaccine in particular. Participants described being inundated with messaging (negative and positive) about COVID-19 vaccines and this led to an information overload. Therefore, a common discussion point was the desire “do their own research,” which, with ongoing probing, meant participants wanted to learn more independently and be provided with links to credible sources of information. To identify credible social media messages, they focused on the sources of information, preferring posts from recognizable health organizations/leaders, and they viewed messaging from non-health experts with skepticism. As a result, participants overwhelming agreed that a social media intervention/campaign to promote vaccination should have (1) messaging delivered by recognizable health experts/organizations, (2) direct links to credible websites so that parents can read/learn more about vaccination for their child, and (3) messaging to promote off-line discussion with their child’s PCP. Similar to many studies, participants in this study continued to recognize that a health care provider recommendation was one of the most powerful influences in their decision making.

The results of this study must be viewed in terms of its limitations. While the sample size was robust for a qualitative study and included participants across all US regions, the sampling method was one of convenience and there could be some bias as it was drawn from a national panel of potential research participants. The sample also lacked racial/ethnic and other socioeconomic diversity and the majority of the participants indicated that they were from the Northeast US region. Differences from state to state and differences between the US and other countries were not captured. Due to the nature of qualitative design the results cannot be generalized beyond this sample, plus text-based discussions (while noted to improve discourse on sensitive topics due to the anonymity)Citation27–31 are limited as verbal and visual cues are not available. The sample did, however, include participants that had a high level of social media utilization and gave voice to parents/primary caregivers who reported a diverse range of vaccine uptake behaviors for their adolescent children. Finally, insights for future social-media vaccine interventions were garnered.

Conclusion

This study captured the influence the COVID-19 pandemic has exerted on social media utilization and the subsequent online public discourse and behaviors surrounding vaccination. Additionally, opinions related to the development of credible and trustworthy social media campaigns to increase vaccine confidence and reduce hesitancy in parental decision making for their adolescents were elucidated. Participants reported a wide range of vaccine behaviors with the majority reporting adolescent vaccination rates well below the Healthy People 2030 goals. Participants described being fatigued from the multiplicity of contentious vaccine-related content on social media and were overwhelmed by the abundance of vaccine information (primarily negative) on social media. The overwhelming majority of participants preferred not to get involved in online discussions related to vaccination because of the expected hostility. Future social media messaging interventions should include posts from recognizable health institutions (e.g., CDC, state or local health departments), professional health associations (e.g. American Academy of Pediatrics, Society of Adolescent Health and Medicine, or National School Nursing Association) or from nationally recognized health care providers with links to resources so that the parent/caregiver can learn more about vaccinations from reputable sources. Providers should ask patients about the types of messaging they have viewed on social media, have additional resources readily available, and continue to provide strong clear recommendations for all routinely recommended adolescent vaccines.

Supplement Table_Focus Group Discussion Guide.docx

Download MS Word (13.5 KB)Disclosure statement

GZ has served as an external advisory board member for Moderna and Pfizer, and as a consultant to Merck. He also has received investigator initiated research funding from Merck administered through Indiana University. HF has received investigator-initiated research funding from Merck administered through the University of Hawaii at Manoa, GG and GZ are also funded on this grant. KO, AM, have nothing to disclose.

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed on the publisher’s website at https://doi.org/10.1080/21645515.2024.2311476.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Centers for Disease Control Prevention. Ten Great public health achievements-United States, 1900–1999. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Report. 1999;48(12):241.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Ten Great public health achievements-United States, 2001–2010. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Report. 2011;60(19):619.

- World Health Organization. Ten Threats to global health in 2019. [accessed 2023 Jan 3]. https://www.who.int/news-room/spotlight/ten-threats-to-global-health-in-2019.

- Robinson CL, Romero JR, Kempe A, Pellegrini C. Advisory committee on immunization practices recommended immunization schedule for children and adolescents aged 18 years or younger — United States, 2017. MMWR Morbid Mortal Wkly Rep. 2017;17(4):1136–11. doi:10.1111/ajt.14245.

- Kim DK, Riley LE, Harriman KH, Hunter P, Bridges CB. Advisory committee on immunization practices recommended immunization schedule for adults aged 19 years or older — United States, 2017. Morb Mortal Wkly Report. 2017;66(5):136–8. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm6605e2.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Recommended vaccinations for children 7 to 18 years old, parent-friendly version- United States, 2023. [accesed 2023 Jan 3]. https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/schedules/easy-to-read/adolescent-easyread.html.

- Office of Disease prevention and Health promotion, Healthy People 2030. US Department of Health and Human Services. [accesed 2023 Jan 3]. https://health.gov/healthypeople.

- Pingali C, Yankey D, Elam-Evans LD, Markowitz LE, Valier MR, Fredua B, Crowe SJ, Stokley S, Singleton JA. National vaccination coverage among adolescents aged 13–17 years — national immunization survey-teen, United States, 2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Report. 2022;71:1101–8. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm7135a1.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Flu vaccination coverage, United States, 2021-22 influenza season. [accessed 2023 Jan 3]. https://www.cdc.gov/flu/fluvaxview/coverage-2022estimates.htm.

- Sturm L, Donahue K, Kasting M, Kulkarni A, Brewer NT, Zimet GD. Pediatrician-parent conversations about human papillomavirus vaccination: an analysis of audio recordings. J Adolesc Health. 2017;61(2):246–51. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2017.02.006.

- Gilkey MB, McRee AL. Provider communication about HPV vaccination: a systematic review. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2016;12(6):1454–68. doi:10.1080/21645515.2015.1129090.

- Gilkey MB, Calo WA, Moss JL, Shah PD, Marciniak MW, Brewer NT. Provider communication and HPV vaccination: the impact of recommendation quality. Vaccine. 2016;34(9):1187–92. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2016.01.023.

- President’s Cancer Panel. HPV vaccination for cancer prevention: progress, opportunities, and a renewed call to action. A Report to the President of the United States from the Chair of the President’s Cancer Panel. Bethesda, MD; 2018.

- Ortiz RR, Smith A, Coyne-Beasley T. A systematic literature review to examine the potential for social media to impact HPV vaccine uptake and awareness, knowledge, and attitudes about HPV and HPV vaccination. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2019;15(7–8):1465–1475. doi:10.1080/21645515.2019.1581543.

- Lin LY, Sidani JE, Shensa A, Radovic A, Miller E, Colditz JB, Hoffman BL, Giles LM, Primack BA. Association between social media use and depression among US young adults. Depress Anxiety. 2016;33(4):323–31. doi:10.1002/da.22466.

- Guidry JP, Carlyle K, Messner M, Jin Y. On pins and needles: how vaccines are portrayed on pinterest. Vaccine. 2015;33(39):5051–6. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.08.064.

- Basch CH, MacLean SA. A content analysis of HPV related posts on instagram. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2019;15(7–8):1476–1478. doi:10.1080/21645515.2018.1560774.

- Walker KK, Owens H, Zimet G. The role of the media on maternal confidence in provider HPV recommendation. BMC Public Health. 2020 Nov 23;20(1):1765. doi:10.1186/s12889-020-09877-x.

- Wawrzuta D, Jaworski M, Gotlib J, Panczyk M. Characteristics of antivaccine messages on social media: systematic review. J Med Internet Res. 2021;23(6):e24564. doi:10.2196/24564.

- Skafle I, Nordahl-Hansen A, Quintaa DS, Wynn R, Garbarron E. Misinformation about COVID-19 vaccines on social media: rapid review. J Med Internet Res. 2022;24(8):e37367. doi:10.2196/37367.

- Cates JR, Shafer A, Carpentier FD, Reiter PL, Brewer NT, McRee A-L, Smith JS. How parents hear about human papillomavirus vaccine: implications for uptake. J Adolesc Health. 2010;47(3):305–8. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2010.04.003.

- McRee AL, Reiter PL, Chantala K, Brewer NT. Does framing human papillomavirus vaccine as preventing cancer in men increase vaccine acceptability? Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2010;19(8):1937–44. doi:10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-09-1287.

- Manganello JA, Chiang SC, Cowlin H, Kearney MD, Massey PM. HPV and COVID-19 vaccines: social media use, confidence, and intentions among parents living in different community types in the United States [published online ahead of print, 2022 Jun 7]. J Behav Med. 2022;46:1–17. doi:10.1007/s10865-022-00316-3.

- Thompson EL, Preston SM, Francis JKR, Rodriguez SA, Pruitt SL, Blackwell J-M, Tiro JA. Social media perceptions and internet verification skills associated with human papillomavirus vaccine decision making among parents of children and adolescents: cross-sectional survey. JMIR Pediatr Parent. 2022 Sep 14;5(3):e38297. doi:10.2196/38297.

- Buller DB, Walkosz BJ, Berteletti J, Pagoto SL, Bibeau J, Baker K, Hillhouse J, Henry KL. Insights on HPV vaccination in the United States from mothers’ comments on Facebook posts in a randomized trial. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2019;15(7–8):1479–87. doi:10.1080/21645515.2019.1581555.

- Reiter PL, Gerend MA, Gilkey MB, Perkins RB, Saslow D, Stokley S, Tiro JA, Zimet GD, Brewer NT. Advancing human papillomavirus vaccine delivery: 12 priority research gaps. Acad Pediatr. 2018;18(2):S14–s16. doi:10.1016/j.acap.2017.04.023.

- Brown CA, Revette AC, deFerranti SD, Fontenot HB, Gooding HC. Conducting web-based focus groups with adolescents and young adults. Int J Qual. 2021;20:1–8. doi:10.1177/1609406921996872.

- Fontenot HB, Fantasia HC, Vetters R, Zimet GD. Increasing HPV vaccination and eliminating barriers: recommendations from young men who have sex with men. Vaccine. 2016;34(50):6209–16. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2016.10.075.

- Fontenot HB, Rosenberger JG, McNair KT, Mayer KH, Zimet G. Perspectives and preferences for a mobile health tool designed to facilitate HPV vaccination among young men who have sex with men. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2019;15(7–8):1815–23. doi:10.1080/21645515.2019.1568156.

- Fontenot HB, Cahill SR, Wang T, Geffen S, White BP, Reisner S, Dunville R. Transgender youth experiences and perspectives related to HIV preventive services. PEDIATRICS. 2020;145(4). doi:10.1542/peds.2019-2204.

- Bustamante G, Liebermann E, McNair K, Fontenot HB. Women’s perceptions and preferences for cervical cancer screening in light of updated guidelines. J Am Assoc Nurse Pract. 2023:1–9. doi:10.1097/JXX.0000000000000923.

- Pew Research Center Social media use in 2021. 2021 Apr. [accessed 2022 Dec 19]. https://pewresearch-org-preprod.go-vip.co/internet/2021/04/07/social-media-use-in-2021/.

- Hsieh HF, Shannon SE. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual Health Res. 2005;15(9):1277–88. doi:10.1177/1049732305276687.

- Valdez D, ten Thij M, Bathina K, Rutter L, Bollen J. Social media insights into US mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic: longitudinal analysis of Twitter data. J Med Internet Res. 2020;22(12):e21418. doi:10.2196/21418.

- Johnson NF, Velásquez N, Restrepo NJ, Leahy R, Gabriel N, El Oud S, Zheng M, Manrique P, Wuchty S, Lupu Y. The online competition between pro- and anti-vaccination views. Nature. 2020 Jun;582(7811):230–233. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2281-1.

- Muric G, Wu Y, Ferrara E. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy on social media: building a public Twitter data set of antivaccine content, vaccine misinformation, and conspiracies. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 2021 Nov 17;7(11):e30642. doi:10.2196/30642.

- Suarez-Lledo V, Alvarez-Galvez J. Prevalence of health misinformation on social media: systematic review. J Med Internet Res. 2021 Jan 20;23(1):e17187. doi:10.2196/17187.

- Wang Y, McKee M, Torbica A, Stuckler D. Systematic literature review on the spread of health-related misinformation on social media. Social Sci Med. 2019 Nov;240:112552. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2019.112552.

- Wilson SL, Wiysonge C. Social media and vaccine hesitancy. BMJ Glob Health. 2020 Oct;5(10):e004206. doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2020-004206.

- Basch CH, Zybert P, Reeves R, Basch CE. What do popular YouTubeTM videos say about vaccines? Child Care Health Dev. 2017 Jul;43(4):499–503. doi: 10.1111/cch.12442.

- Saxena K, Marden JR, Carias C, Bhatti A, Patterson-Lomba O, Gomez-Lievano A, Yao L, Chen Y. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on adolescent vaccinations: projected time to reverse deficits in routine adolescent vaccination in the United States. Curr Med Res Opin. 2021;37(12):2077–2087. doi:10.1080/03007995.2021.1981842.

- Kujawski SA, Yao L, Wang E, Carias C, Chen Y. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on pediatric and adolescent vaccinations and well child visits in the United States: a database analysis. Vaccine. 2022;40(5):706–713. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2021.12.064.

- Murthy PB, MStat EZ, Kirtland K, Jones-Jack N, Harris L, Sprague C, Schultz J, Le Q, Bramer CA, Kuramoto S, et al. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on administration of selected routine childhood adolescent vaccinations- 10 U.S. Jurisdictions, March-September 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Report. 2021;70 (23):840–845. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm7023a2.

- Ryan G, Gilbert PA, Ashida S, Charlton ME, Scherer A, Askelson NM. Implementation of evidenced-based interventions to promote vaccine uptake during the COVID-19 pandemic:” HPV is probably not at the top of our list. Prev Chronic Dis. 2022;19:210378. doi:10.5888/pcd19.210378.

- Seither R, Laury J, Mugerwa-Kasujja A, Knighton C, Black CI. Vaccination coverage with selected vaccines and exemption rates among children in kindergarten- United States, 2020-21 school year. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Report. 2022;71(16):561–8. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm7116a1.