ABSTRACT

In 2020–21, during the COVID-19 pandemic, a free influenza vaccination program was initiated among the elderly residents in Ningbo, China. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic and free vaccination policy on influenza vaccine uptake needs to be evaluated. The influenza vaccine uptake among individuals born before 31 December, 1962 from 2017–18 to 2022–23 season in Ningbo was analyzed. Multivariate logistic regressions were used to estimate the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic and free vaccination policy. Our analysis included an average of 1,856,565 individuals each year. Influenza vaccination coverage increased from 1.14% in 2017–18 to 33.41% in 2022–23. The vaccination coverage among the free policy target population was 50.03% in 2022–23. Multivariate analysis showed that free vaccination policy increased influenza vaccine uptake most (OR = 11.99, 95%CI: 11.87–12.11). The initial phase of the pandemic was associated with a positive effect on influenza vaccination (OR = 2.09, 95%CI: 2.07–2.12), but followed by a negative effect in the subsequent two seasons(2021–22: OR = 0.75, 95%CI: 0.73–0.76; 2022–23: OR = 0.40, 95%CI: 0.39–0.40). COVID-19 vaccination in the current season was a positive predictor of influenza vaccine uptake while not completing booster COVID-19 vaccination before was negative predictor in 2022–23. Having influenza vaccine history and having ILI medical history during the last season were also positive predictors of influenza vaccine uptake. Free vaccination policies have enhanced influenza vaccination coverage among elderly population. The COVID-19 pandemic plays different roles in different seasons. Our study highlights the need for how to implement free vaccination policies targeting vulnerable groups with low vaccination coverage.

Introduction

Influenza is a highly contagious acute respiratory infectious disease that circulates annually with an estimated infection rate of 10% in unvaccinated adults and 20% in unvaccinated children.Citation1,Citation2 Each year, there are more than 1 billion cases of influenza, of which 3–5 million are severe cases and 290 000–650 000 influenza-related respiratory deaths globally.Citation2,Citation3 Older adults are at a greater risk of developing severe influenza, complications, hospitalization and mortality than other populations. The 2017 Global Burden of Disease Study indicated that adults aged 70 years or older had the highest mortality rate from influenza lower respiratory tract infections.Citation4

To date, immunization is the most effective strategy for preventing influenza, particularly for preventing severe disease in older adults. The World Health Organization (WHO) recommends that all countries should consider implementing seasonal influenza immunization programs in certain target groups, such as older adults.Citation2 Many countries including major European countries, the United States and South Korea, provide free influenza vaccination to the elderly. However, the influenza vaccination rate among the elderly population has not reached the WHO target of 75%Citation5 and vaccine uptake is highly variable among countries. Although vaccine acceptance is a complex phenomenon with more than 70 influencing factors identified, many of which are time-specific and context-specific, the free policy, the necessary recommendations, the awareness of the burden of influenza, and concerns about vaccine safety and efficacy should be considered.Citation6,Citation7

Despite the fact that seasonal influenza is associated with notable mortality and morbidity in the elder populationCitation8,Citation9 in China and the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention (China CDC) designates the elderly as a priority group for influenza vaccination,Citation10 influenza vaccination is not included in the National Immunization Program (NIP). This may contribute to low vaccine coverage of 3.16% and 2.47% for the entire population in China during the influenza seasons of 2020–21 and 2021–22, respectively.Citation11 In recent years, a number of provinces and large cities have implemented annual free influenza vaccination policies for the elderly population with the aim of increasing vaccination coverage.Citation12–14 Ningbo is an economically developed coastal city located in Zhejiang Province and has two influenza activity peaks, one in November to February and the other in July to September.Citation15 The incidence rate of influenza infections indicated by serology in the elderly was 21% during the winter season of 2019–20.Citation15 In 2020, with the COVID-19 pandemic, a free influenza vaccination program was initiated in Zhejiang Province was initiated, providing the trivalent inactivated influenza vaccine to the elderly permanent household residents aged 70 years or older. In Ningbo, the target population has been expanded to permanent household residents aged 65 years or older since the 2021–22 season. Furthermore, the elderly are permitted to select the self-paid quadrivalent inactivated influenza vaccine as an alternative. The free influenza vaccine in Ningbo can be only administered at community healthcare centers and consigned medical institutions. Individual-level vaccination records are stored in the Zhejiang Immunization Information Management System (ZJIIMS), which provides an optimal tool for estimating influenza vaccination coverage in the elderly population.

A multitude of factors influence the influenza vaccination behavior of the elderly. During the COVID-19 pandemic, the similar initial symptoms of influenza and COVID-19, coupled with the potential co-circulation of both viruses, have led to heightened awareness of influenza vaccination, influencing vaccine uptake. A recent meta-analysis demonstrated that the COVID-19 pandemic has led to an increase in the intention to vaccinate against influenza.Citation16 However, other studies have indicated a decrease in influenza vaccination coverage during the same period.Citation11,Citation17,Citation18 To the best of our knowledge, no studies have been conducted to investigate whether free vaccination policies and the COVID-19 pandemic affect influenza vaccination coverage among the Chinese elderly population. Consequently, we conducted this study with the objective of estimating the trends of influenza vaccination coverage during six influenza seasons from 2017–18 to 2022–23, utilizing data from ZJIIMS, with a particular focus on the change between pre- and post- the COVID-19 pandemic. Furthermore, the impact of the free vaccination policy for influenza vaccination among the elderly was evaluated during three seasons from 2020–21 to 2022–23, with particular attention paid to the influence of the COVID-19 pandemic and the associated vaccination campaign.

Materials and methods

Target population

Given that annual seasonal influenza vaccines are available from July or August onwards, the influenza season was defined as the period from July 1 through May 31 of the following year. For each season under consideration (2017–18 through 2022–23), the elderly individuals were eligible for inclusion if they met the following criteria: 1) were born before 31 December, 1962; and 2) were registered in ZJIIMS and lived in Ningbo during the study period; and 3) were alive on July 1 of each influenza season.

Data resources

Appropriate anonymized individual records of the elderly, including vaccination records between July 1, 2017 and June 30, 2023 and demographic information were extracted from ZJIIMS on 30 June 2023. ZJIIMS is a computerized, population-based vaccination registration system, containing demographic information and all the vaccination records (including the vaccination records of more than 20 types of vaccines used in Ningbo) for the population living in Zhejiang Province. All vaccination clinics from 10 districts in Ningbo city are included in ZJIIMS. Upon the first visit to a vaccination clinic in Ningbo, the individual’s information will be registered into ZJIIMS, accompanied by a unique national identification number (NID). In light of the implementation of the COVID-19 vaccination campaign among the elderly since June 2021, a community-based initiative in Ningbo sought to collate and register the basic information of all individuals over the age of 60 residing in the area and this information was subsequently registered into ZJIIMS. Consequently, nearly all the elderly individuals residing in Ningbo were duly registered in ZJIIMS upon reaching the age of 60. Vaccination records from 2012 onwards were entered into ZJIIMS and updated in real time. The mortality data for the elderly was updated in accordance with the data from the Ningbo Death Surveillance Information System using the Unique NID number. The diagnosis records of influenza-like illness (ILI) of the elderly between July 1, 2017 and June 30, 2022 were obtained from the data warehouse of the Ningbo Regional Health Information Platform (NRHIP) which includes all the electronic medical records (EMRs) data of outpatient, emergency and inpatient visits from a network of all 65 public hospitals and 154 primary care institutions across Ningbo. The data is linked with other datasets using unique NID numbers.

Measures

In this study, we evaluated influenza vaccine uptake at the individual level for each influenza season. The outcome variable was defined as influenza vaccine coverage which was calculated as the proportion of vaccinated elderly individuals among the target population.

The free influenza vaccination policy was initiated in September 2020 and targeted permanent residents aged 70 years and older or born before 31 December 1950 during the 2020–21 season. In the 2021–22 season, the target population of the free influenza vaccination policy was expanded to include the permanent residents aged 65 years and older or born before 31 December 1956. In the 2022–23 season, the policy was extended to include the permanent residents born prior to 31 December 1957 (). The free influenza vaccines provided were trivalent inactivated split-virion influenza vaccines. All the other individuals were required to pay for the full cost of the influenza vaccine.

Table 1. Eligibility for free influenza vaccination in Ningbo, China by date of birth and immigration status.

As COVID-19 began to spread in Ningbo in mid-January 2020, when the influenza vaccination in the 2019–20 season was nearly complete, we defined the 2017–18 to 2019–20 season as the pre-COVID-19 period and the 2020–21 to 2022–23 season as period of the COVID-19 pandemic.

With regard to covariates, we obtained demographic characteristics and vaccination history from ZJIIMS. The demographic characteristics included gender, date of birth, immigration status, and region of residence. The immigration status of the subjects was categorized into two types: resident population and migrant population. The resident population was defined as individuals who have household registration and a place of actual residence within Ningbo. In contrast, the migrant population was defined as individuals who do not have household registration and reside temporarily in Ningbo from other municipalities in China. With regard to the region of residence, the areas were divided into two categories: the urban areas included the districts of Haishu, Jiangbei, Yinzhou, Zhenhai, Beilun and Fenghua, while the rural areas comprised the districts of Yuyao, Cixi, Ninghai and Xiangshan.

As ILI history and influenza vaccination history have been found to be important predictors of influenza vaccine uptake,Citation19–21 we obtained the diagnosis of ILI in the previous influenza season using corresponding ICD-10-CM codes (Supplemental Table 1) from NRHIP and influenza vaccination in the previous influenza season from ZJIIMS. It should be noted that the COVID-19 vaccination campaign was commenced in October 2020 and was implemented on a large scale among the elderly during 2021–2022. This may also have an impact on influenza vaccine uptake, as evidenced by studies indicating that the uptake of influenza vaccines is influenced by prior vaccination against other pathogens, including COVID-19.Citation22–24 Therefore, COVID-19 vaccination before this season and during August to December of each influenza season were also obtained from ZJIIMS.

Statistical analysis

All analyses were conducted using STATA version 16 for Windows (StataCorp LLC, College Station, TX). Microsoft Excel was also used for figure generation. Descriptive statistics were calculated for all study variables, including counts and proportions. The influenza vaccination coverage rates stratified by demographic characteristics, free vaccination policy, COVID-19 pandemic, previous influenza and COVID-19 vaccination history were calculated. The weekly counts of influenza vaccine uptake after July 1 in each influenza season were computed.

A multivariate logistic regression model was constructed to examine the associations of individual influenza vaccine uptake with gender, age, immigration status, region, free influenza vaccination policy, COVID-19 pandemic status, diagnosis with ILI last influenza season, previous influenza and COVID-19 vaccination history and COVID-19 vaccination status in the current season during 4 seasons from 2019–20(the season before COVID-19 pandemic) to 2022–23. As a sensitivity check, we also conducted multivariate logistic regression models without the COVID-19 pandemic indicator for 2019–20, 2020–21, 2021–22 and 2022–23 season separately. In all the analysis, A two-tailed p-value of < .05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Description of the study population

The number of individuals in the study population who fulfilled the eligibility criteria was 1,861,959 in 2017–18, decreasing to 1,838,794 in 2022–23, with an average of 1,856,565 per season over the 6 seasons. In our analytical sample, 50.34% were female, 48.84% were living in the urban area of Ningbo and 83.36% were local residents on average. The proportions of subjects in the 60–64, 65–69, 70–79 and ≥80 years age groups on Dec.31 2022 were 28.10%, 28.43%, 31.05% and 12.42% on average. The free influenza vaccination policy target population in 2020–21 was 32.47% of the study population, which increased to 58.03% in 2021–22 and 62.84% in 2022–23.

With regard to medical history, 27.14% and 30.71% of the study population had a diagnosis of ILI during the last season in 2018–19 and 2019–20 respectively before the COVID-19 pandemic while the proportion of subjects with ILI during the last season subsequently declined to 13.95% in 2022–23 during COVID-19 pandemic. The proportion of subjects with a history of influenza vaccination during the last season increased from 0.24% in 2017–18 to 27.73% in 2022–23. During the COVID-19 pandemic, 0.07%, 53.69% and 12.51% of the participants received COVID-19 vaccination between August and December in 2020–21, 2021–22 and 2022–23 respectively. The proportion of subjects with COVID-19 vaccination history was 65.31% in 2021–22 and 95.65% in 2022–23.

The details of the main characteristics of the study sample by gender, age on Dec.31 2022, region, immigration status, free influenza vaccination policies, diagnosis of ILI last influenza season, influenza vaccination last season, the COVID-19 pandemic, COVID-19 vaccination in the current season and before during each season from 2017–18 to 2022–2023 are summarized in .

Table 2. Characteristics of enrolled elderly in influenza seasons from 2017–18 to 2022–23, Ningbo City.(N, %).

Changes in influenza vaccine uptake in the target groups and the impact of the free policy

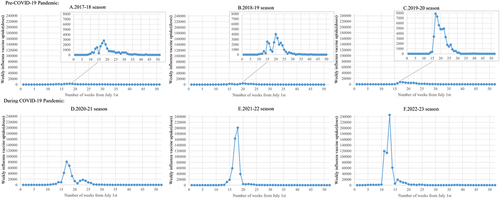

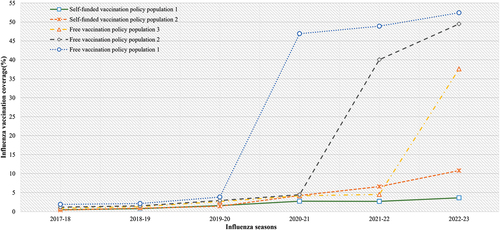

The overall influenza vaccination coverage in the elderly population increased from 1.14% in the 2017–18 to 33.41% in the 2022–23 (). Among those eligible for a free vaccination policy, the coverage was 46.91% in 2020–21, 44.98% in 2021–22 and 50.03% in 2022–23. presents a graphical representation of the temporal evolution of influenza vaccine uptake among the target groups. The influenza vaccination coverage of the 2020–21 free influenza vaccination policy cohort (aged over 72 on Dec.31 2022, residents) increased dramatically in the first season (2020–21) when they were eligible for free influenza vaccination, reaching 46.91%. Thereafter, the increase was more gradual in the next two seasons, reaching 48.90% in 2021–22 and 52.44% in 2022–23. In the second and third seasons (2021–22, 2022–23), the coverage of the free influenza vaccination policy cohorts (aged 66–71 or 65 on Dec.31 2022, residents) demonstrated a comparable initial increase, although the coverage was lower, at 40.06% for the 2021–22 free vaccination policy cohort (aged 66–71 on Dec.31 2022, residents) and 37.61% for the 2022–23 free vaccination policy cohort (aged 65 on Dec.31 2022, residents). In the 2022–23 season (the second season of the free vaccination policy for the 2021–22 free vaccination policy cohort), the coverage of this cohort increased to 49.49%, which was close to the coverage for the 2020–21 free influenza vaccination policy cohort (aged over 72 on Dec.31 2022, residents). In contrast, the coverage of the self-funded vaccination policy cohort increased annually, albeit at a slower pace. The growth was from 0.5% in 2017–18 to 3.62% in 2022–23 for the self-funded vaccination policy cohort (aged 60–64 on Dec.31 2022) and from 0.43% in 2017–18 to 10.78% in 2022–23 for the self-funded vaccination policy cohort (aged over 65 on Dec.31 2022, migrants). As anticipated, after controlling for demographic characteristics, medical and vaccination history, and the COVID-19 pandemic, the free influenza vaccination policy had a strong effect on influenza vaccination coverage (OR = 11.99, 95%CI: 11.87–12.11). This effect was observed to be particularly pronounced in the 2020–21 and 2021–22 seasons, with ORs of 17.45 (95% CI: 17.07–17.85) and 9.38 (95% CI: 9.16–9.61), respectively ().

Figure 1. Trends of influenza vaccination coverages in target birth cohorts from 2017–18 to 2022–23 season.

Table 3. Influenza vaccine uptake among the elderly by influenza season, demographic characteristics, free vaccination policy, medical and vaccination history during pre- and post-Covid-19 pandemic in Ningbo.

Table 4. Factors associated with influenza vaccination among the elderly in Ningbo.

The impact of COVID-19 related factors on influenza vaccine uptake

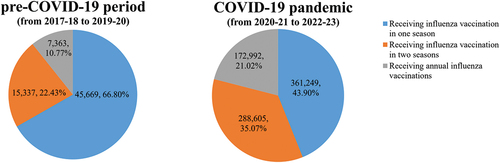

The COVID-19 pandemic was also associated with influenza vaccination coverage. For both the free vaccination policy cohorts and self-funded vaccination cohorts, influenza vaccination coverages during the COVID-19 pandemic were higher than that in the pre-COVID-19 period (, ). Interestingly, after controlling for the other characteristics, we found that the COVID-19 pandemic was found to have a positive effect on influenza vaccine uptake in the initial season of the pandemic in comparison to the pre-COVID-19 period (OR = 2.09, 95%CI: 2.07–2.12). However, the pandemic was found to have a negative effect in the subsequent two seasons of the pandemic (second year: OR = 0.75, 95%CI: 0.73–0.76; third year: OR = 0.40, 95%CI: 0.39–0.40) (). illustrates that the weekly influenza vaccine uptake during the pandemic was significantly higher than the uptake before the COVID-19 pandemic. The peak uptake during the COVID-19 pandemic was 245,740 doses in 2022–23 while the peak uptake prior to the onset of the pandemic was only 7884 doses in 2019–20. Furthermore, we observed that most elderly individuals received the influenza vaccination in a shorter period of time during 2021–22 and 2022–23 (). In addition, the frequency of influenza vaccination increased during the pandemic. Prior to the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, only 10.77% of influenza vaccine recipients opted to receive influenza vaccine annually, while 22.43% received influenza vaccine twice over the course of three seasons. During the COVID-19 pandemic, the proportion of individuals receiving annual influenza vaccine increased to 21.02%, while 35.07% received influenza vaccine twice ().

Figure 3. Frequency of influenza vaccination among the elderly before and during the COVID-19 pandemic.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, despite the lack of a recommendation from the China CDC for the simultaneous administration of the COVID-19 and influenza vaccines, multivariate logistic regression analysis demonstrated that the COVID-19 vaccination from August to December in the current season increased the probability of influenza vaccine uptake (1 dose: OR = 1.65, 95%CI: 1.63–1.66; ≥2 doses: OR = 2.02, 95%CI: 1.99–2.05). Notably, the impact of COVID-19 vaccination history on influenza vaccination was positive in 2021–22 (1 dose: OR = 1.59, 95%CI: 1.56–1.61; ≥2 doses: OR = 3.10, 95%CI: 3.07–3.14) but varied by doses administered in 2022–23. In 2022–23, the COVID-19 vaccination history still provided positive effect on influenza vaccination among the population with a history of at least 3 doses COVID-19 vaccination (≥3 doses: OR = 2.07, 95%CI: 2.04–2.11) but had a negative effect among the population with a history of 1 or 2 doses COVID-19 vaccination (1 dose: OR = 0.59, 95%CI: 0.57–0.60; ≥2 doses: OR = 0.98, 95%CI: 0.96–0.99).

Impact of ILI medical history and influenza vaccination history on influenza vaccine uptake

demonstrates the influenza vaccination coverage by ILI medical history and vaccination history. For each season (2018–19 to 2022–23), the elderly with the diagnosis of ILI last season had a higher coverage rate than those who without such a diagnosis (), and Our analysis indicated that the odds of receiving an influenza vaccination was 1.47 (95%CI: 1.46–1.48) in total which was higher in 2019–20 during pre-COVID-19 period (OR = 2.38, 95%CI: 2.33–2.43). As excepted, the population with influenza vaccination history last season demonstrated a consistently high level of influenza vaccination coverage across all six seasons, ranging from 45.06% to 73.75%. They also exhibited a markedly higher likelihood of receiving the influenza vaccination compared to those without influenza vaccination history last season (OR = 6.44, 95%CI: 6.40–6.48). The strongest association was observed during the 2019–20 season (OR = 81.00, 95%CI: 78.75–83.32), although the increase in influenza vaccine uptake was smaller than that observed in the population without influenza vaccination history last season from 2019–20 to 2020–21. In the 2020–21 season, influenza vaccination coverage increased by 14.53 points(p < .001) among the population with influenza vaccination history last season and 4.05 points(p < .001) among the population without, compared to the 2019–20 season.

The associations between demographic factors and influenza vaccine uptake

also demonstrates the influenza vaccination by different demographic characteristics in each season. As anticipated, the influenza vaccination coverage was found to be lower among females than males, among residents than migrants in all 6 seasons. Before the COVID-19 pandemic, influenza vaccination coverage increased with age. Individuals in each age group experienced a relatively modest improvement in influenza vaccination coverage from 2017–18 to 2019–20. During the COVID-19 pandemic, individuals aged 65 and above exhibited a higher probability of influenza vaccination compared to those aged 60–64 years old (). The influenza vaccination coverage among 70–79 age group increased the most, with a substantial improvement of 50.57% points from 2019–20 to 2022–23; Among the individuals aged over 80 years old, the coverage increased by 38.53% points (p < .001) at the first influenza season of the COVID-19 pandemic and decreased by 7.19% points (p < .001) in 2021–22, before experiencing a slight recovery of 3.10% points (p < .001) in 2022–23. Furthermore, we found that living in the urban area was associated with slightly higher odds of vaccination compared to those living in the rural areas (OR = 1.25, 95%CI: 1.24–1.25).

Discussion

We conducted a comprehensive analysis of data from a large and well-established population-based cohort of older Chinese individuals living in eastern China with the primary aim of better understanding influenza vaccine uptake from 2017–18 before the COVID-19 pandemic to 2022–23 during the pandemic. This enabled us to monitor fluctuations in vaccine uptake over time among the same individuals and to investigate potential associations with a range of factors, including ILI medical experience and COVID-19 vaccination status.

In China, influenza vaccination coverage has among the elderly remained low over past few years.Citation25 Prior to the implementation of a free vaccination policy and the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, the influenza vaccination coverage among the elderly population in Ningbo ranged from 1.14% to 2.70%. A previous study demonstrated that the provision of a free influenza vaccine to the elderly population in China was highly cost-effective, with the potential to prevent 19,812 ILI outpatient consultations, 9418 severe acute respiratory infection hospitalizations, and 8800 respiratory excess deaths due to influenza, while also gaining 70,212 quality-adjusted life years per year.Citation26 In this study, influenza vaccination coverage among elderly residents in Ningbo found to be similar to the national level during the 2020–21 season, but significantly higher during the 2021–22 season.Citation11 In accordance with the findings of previous studies,Citation11,Citation21 our results indicated that the free vaccination policy was the most effective intervention, rapidly and substantially increasing and sustaining influenza vaccine uptake. Furthermore, our findings indicated that the impact of the free vaccination policy was more pronounced in the initial season of the free policy and the subsequent season, during which the target population of free policy was expanded from residents aged 70 and above to those aged 65 and above. Consistent increases in influenza vaccine utilization were also observed during the 2021–22 and 2022–23 seasons among the free influenza vaccination policy cohorts. This contrasts with the findings of other studies which reported decreased influenza vaccination coverage during the COVID-19 pandemic.Citation11,Citation18 This consistent increase in vaccine coverage may be attributed to the expanded promotion of the free policy by the government, media outlets and healthcare providers. Furthermore, we also observed a slight annual increase in the influenza vaccine uptake prior to the implementation of the free vaccination policy and the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. The reason for the higher rate compared to that of the 2017–18 season may be attributed to the official statement by the Chinese Health Commission in 2018–19 encouraging influenza vaccination among vulnerable populations,Citation27 as well as the policy of the Ningbo Health Commission encouraging healthcare workers to recommend influenza vaccines to the elderly with chronic diseases.Citation28,Citation29 The results demonstrated that, despite the implementation of a free influenza vaccination policy, the observed coverage rate of 50.03% among the population with a free vaccination policy in the 2022–23 influenza season, as covered by the policy, remained well below the 75% target set by the WHO. This challenge remained unresolved in Europe, where the policy had been operational for a considerable number of years. It would be beneficial to apply the insights gained from the large-scale COVID-19 vaccination campaign, which resulted in over 90% of the elderly receiving the vaccine, to the current situation. A study conducted in EuropeCitation6 indicated that a focus on raising awareness and education on the burden of disease, in conjunction with the broader usage of improved influenza vaccines for the elderly, could be considered as a complementary approach. The most interesting result need to be noted that the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic varied in the different seasons. In the initial phase of the pandemic (2020–21), our findings indicated that the pandemic was associated with an increased likelihood of influenza vaccination among elderly individuals. This is consistent with reports from the U.S., England and Canada.Citation19,Citation20,Citation30 In the early days of the pandemic, a great deal of information about COVID-19 was conveyed to the public, raising public concerns about similar respiratory infectious diseases like influenza. This motivated individuals to receive the influenza vaccination in order to protect themselves both from influenza directly and from co-infection with COVID-19 with supporting evidence of vaccine effectiveness.Citation31 In addition, the unavailability of the COVID-19 vaccine for the elderly in the 2020–21 season might urge them to be more likely to seek for vaccination against influenza. In the second and third seasons of the pandemic (2021–22, 2022–23), the impact of the pandemic was shown to be negatively related to the influenza vaccine uptake. In the 2021–22 season, the well-controlled COVID-19 pandemic and low prevalence of influenza in 2020–21 led the public to believe that the strict implementation of COVID-19 preventive measures, such as wearing face masks, bans on large gatherings and nonessential activities, and social distancing, were sufficient to protect themselves from infection even without vaccination. Consequently, there was a reduction in the perceived need for receiving influenza vaccination. Furthermore, the considerable workload of the vaccination clinicsCitation32 resulting from the extensive COVID-19 vaccination campaign since March 2021 may have a detrimental impact on the availability of other vaccination services and may negatively influence the uptake of influenza vaccines. In the 2022–23 season, massive COVID-19 infections sweeping the country occurred in December 2022 and January 2023. This resulted in a number of challenges in accessing influenza vaccinations, which further negatively impacted vaccination coverage. This was due to the fact that people were only permitted to be vaccinated only in community healthcare centers which may have exposed them to the risk of contracting COVID-19. It is noteworthy that a shift in utilization patterns was also observed during the pandemic. The weekly influenza vaccine uptake exhibited a marked increase from approximately 3000 doses in 2017–18 to over 80,000 doses in 2020–21 and then to more than 200,000 doses in 2021–22. During the pandemic, in response to the necessity of a massive vaccination campaign, the local government implemented a series of measures to facilitate the vaccination of the elderly. These included the establishment of temporary influenza vaccination clinics in communities and the provision of complimentary shuttle services to and from the vaccination clinics, making it easier for the elderly to be vaccinated. Technical guidelines for influenza vaccination in China (2021–2022)Citation33 also recommended a number of measures designed to improve influenza vaccine uptake. These included increasing the number of primary influenza vaccination points, starting vaccination earlier, increasing the frequency of vaccination services and daily service hours to improve influenza vaccine uptake.

The findings of this study indicate that COVID-19 vaccination status also affected the influenza uptake. In Ningbo, COVID-19 vaccines were firstly available for the healthcare workers in October, 2020 and subsequently expanded to the population aged 18–59 in March, 2021 and to the elderly aged over 60 in June 2021. In all three seasons during the pandemic, although co-administration of the two vaccines is not permitted,Citation33 receiving COVID-19 vaccination in the current season was found to increase the likelihood of influenza vaccine uptake indicating trust in the vaccine and awareness of immunization among this population. However, in the 2022–23 season, a history of 1 or 2 doses of the COVID-19 vaccine was associated with a decreased likelihood of receiving the influenza vaccine, when compared with those who had not received the COVID-19 vaccine. The results indicated that individuals who had self-determined contraindications to the COVID-19 vaccine and excessive concerns about vaccine side effects were less likely to be vaccinated against influenza. This may have contributed to a lack of trust in influenza vaccines. Conversely, those who had completed the booster dose of the COVID-19 vaccine were more likely to receive the influenza vaccine than those who had never received COVID-19 vaccine. This suggests that confidence in the safety and effectiveness of the vaccine and awareness of the COVID-19 vaccination can promote influenza vaccine uptake. This finding represents a significant addition to previous findings indicating that perceptions of a higher risk of adverse events following vaccination may act as a deterrent to influenza vaccine uptake among the elderly.Citation7,Citation34 Nevertheless, inactivated influenza vaccines, which are used in the elderly, display a robust safety profile.Citation35 The most frequently reported reactions are injection-site pain, fatigue, headache and myalgia. The incidence of adverse reactions is lower in the elderly than in other adults.Citation35 In Ningbo, the adverse events following immunization (AEFI) surveillance data indicates that the AEFI rate of influenza vaccine in the elderly during the 2020–21 to 2022–23 influenza season was only 7.23/100,000. Moreover, 92.86% of these reactions were classified as mild local reactions, indicating a high level of vaccine safety. This comparison serves to highlight the necessity of addressing the misconceptions surrounding the side effects and contraindications of influenza vaccines in the elderly.

Besides COVID-19 vaccination, our results echoed some observational studies showing that the influenza vaccination history was a strong motivator for future influenza vaccination.Citation19,Citation20,Citation31 This phenomenon indicated that individuals who have previously received an influenza vaccine tend to continue this vaccination behavior. This may be due to the behavioral inertia, whereby people often persist with their established behavior.Citation36 In this study, as influenza coverage has increased sharply since 2020–21, we observed an increase in the proportion of persisting continuous influenza vaccination in three seasons among influenza vaccine recipients, from 10.77% (2017–18 to 2019–20) to 21.02% (2020–21 to 2022–23). These findings indicate that encouraging influenza vaccination among those who have never been vaccinated may be an effective long-term strategy for modifying vaccine uptake behavior. In our study, the highest influenza coverage among the elderly with the free vaccination policy was only 50.03% in 2022–23, which was significantly lower than the coverage in developed countries with similar policiesCitation5,Citation20,Citation37 and also far below the World Health Organization target of 75% coverage. Moreover, a previous study conducted in Shanghai revealed that 88.3% of elderly individuals were willing to receive a free influenza vaccine during the COVID-19 pandemic. This estimate was considerably higher than the actual influenza vaccination coverage observed in our study, indicating a notable discrepancy between influenza vaccination intentions and subsequent vaccine uptake. Hence, more must be done besides providing free vaccination. Identifying those who have not been vaccinated recently and the reasons for vaccine hesitancy, and further developing tailored interventions for this population should be prioritized for increasing influenza vaccine uptake in the future. A more nuanced understanding of influenza vaccination behaviors among specific demographic groups can assist policymakers in more effectively incentivizing vaccine uptake and reducing disparities. This study identified several subgroups with persistently low vaccination rates. A comparison of the vaccination coverage of local residents with that of the migrant population revealed a significant disparity. The primary reason for this discrepancy is that the migrant population is not the target population of the free vaccination policy and therefore must bear the financial responsibility for vaccination. Consequently, it is of the utmost importance to provide this subgroup with financial support in order to encourage vaccine uptake in the future. Furthermore, the lack of accessibility to influenza vaccination information is a significant contributing factor to the low vaccination coverage observed among the migrant population. A study conducted in ShanghaiCitation38 during the COVID-19 pandemic revealed that perceived susceptibility to COVID-19 and ever consulting a medical professional about COVID-19 were independent predictors of influenza vaccination uptake. This was because some individuals might have received a recommendation for influenza vaccination during their consultations for COVID-19. Consequently, targeted educational interventions for the migrant population, which emphasize the risks of influenza infections and the importance of seasonal flu vaccination, especially during the ongoing pandemic, are required to increase the influenza vaccine uptake among this subgroup.Citation38 Living in rural areas was also found to be a negative predictor of influenza vaccine uptake. Nevertheless, the discrepancy narrowed during the initial two years of the pandemic as the number of temporary influenza vaccination points increased. The ILI medical history in the last season was also a significant predictor of influenza vaccine uptake. Two potential explanations for this phenomenon can be proposed. Firstly, the experience of influenza-like illness heightened their awareness of the potential severe outcomes of influenza infection, thereby motivating them to get vaccinated. Secondly, the results indicated that the probability of non-vaccination was higher in those who interacted less with the health system and had fewer medical appointments. This finding reinforces the importance of guidance in the field of primary prevention. The utilization of public health services should be improved and healthcare workers should be encouraged to recommend the influenza vaccine to the subgroups with the persistently low vaccination rates. These findings contribute to the existing body of evidence on how individual vaccination decisions changed during the pandemic.

This study has several limitations. Firstly, this study included only the elderly registered in ZJIIMS. Before the COVID-19 pandemic, elderly individuals were registered only when they were vaccinated. As a result of the COVID-19 vaccination campaign that began in June 2021, nearly all the elderly individuals living in Ningbo have been registered in ZJIIMS. Therefore, those who had never been vaccinated and died before June 2021 were missed. This may have resulted in an overestimation of influenza vaccination coverage before the COVID-19 pandemic in Ningbo. However, we believe that this impact is minor, as the mortality rate of the elderly individuals over 60 was approximately 2.2% in Ningbo. Secondly, although we captured important information in our estimates but still limited. Knowledge, belief and practice about the influenza vaccination among the elderly undoubtedly play a crucial role in vaccination uptake. Although we acknowledge its significance as a predictor of vaccine uptake among the elderly, regrettably, this information was not specifically recorded or evaluated in the dataset utilized for this study, thereby limiting our ability to comprehensively evaluate its influence on vaccine uptake. Consequently, we were unable to explore other determinants of influenza vaccine uptake among the elderly. In light of the accessibility of the free influenza vaccination policy and the knowledge, belief, and practice gaps among different groups, we have included the variable “Eligible for free influenza vaccination” in our analysis in order to mitigate this limitation. Further studies are required to identify motivators and barriers associated with vaccination and to focus on increasing overall coverage. Third, this study examined the ZJIIMS data up to the 2022–23 season. With the gradual liberalization of COVID-19 preventive measures since December 2022, the transmission and evolution of influenza viruses have changed accordingly,Citation39 which may affect the influenza vaccination behavior in the next season. Furthermore, the alteration of the complimentary vaccination policy(with the target population expanding to those living in Ningbo aged 60 or above in the 2024–25 season) may also have an impact on the influenza vaccine uptake. This study was unable to examine the data in its entirety. A further analysis of the data, incorporating data from the following years, is required.

Conclusion

Our study provides insights into the impact of the free vaccination policy and the COVID-19 pandemic on seasonal influenza vaccination uptake among older adults in Ningbo, China. Free vaccination policies for the elderly have enhanced influenza vaccination coverage. The COVID-19 pandemic promoted influenza vaccine uptake in 2020–21, but had a negative impact in 2021–22 and 2022–23. The findings that having influenza vaccine history last season, finishing the booster COVID-19 vaccination, taking the COVID-19 vaccine in the current season and having ILI medical history last season were positive predictors of influenza vaccine uptake showed that more efforts must be undertaken to target those who do not routinely engage with public health services. Recently, the WHO has appealed to all countries to consider developing or revising national respiratory pathogen (including influenza and coronaviruses) pandemic preparedness plansCitation40 and implementing an influenza vaccination program or including influenza vaccination in their national immunization program.Citation41 This is due to the unpredictable and recurring nature of respiratory pathogen pandemics as well as the potentially catastrophic consequences for human health and socioeconomic wellbeing. Future efforts should be directed toward the determination of the most effective means of implementing a policy of free vaccination, with a particular focus on the active promotion of vaccination among vulnerable populations with low vaccination coverage.

Author contributions statement

LY, YS, and TY conceived and designed the study. LY, JC, and TY helped with data collection. LY and TY provided statistical advice on study design and performed data analysis. LY, JC, and QM contributed to manuscript preparation and revision. All the authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethical considerations

The protocol for this research was approved by the Research Ethics Review Board of Ningbo Municipal Center for Disease Prevention and Control (No.202208). Informed consent was exempted because it was limited to analysis of previously de-identified data collected for public health surveillance purposes.

Supplemental files.docx

Download MS Word (20 KB)Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Shixing Chu from Suzhou Shensu Automatic Technology Co., Ltd. and Tang Lin from Ningbo Municipal Health Information Center for providing assistance with the ZJIIMS data.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Supplemental material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed on the publisher’s website at https://doi.org/10.1080/21645515.2024.2370999

Additional information

Funding

References

- Somes MP, Turner RM, Dwyer LJ, Newall AT. Estimating the annual attack rate of seasonal influenza among unvaccinated individuals: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Vaccine. 2018;36(23):3199–12. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2018.04.063.

- World Health Organization. Vaccines against influenza: WHO position paper –May 2022 [accessed]. 2022 May 13. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/who-wer9719.

- Iuliano AD, Roguski KM, Chang HH, Muscatello DJ, Palekar R, Tempia S, Cohen C, Gran JM, Schanzer D, Cowling BJ, et al. Estimates of global seasonal influenza-associated respiratory mortality: a modelling study. Lancet. 2018;391(10127):1285–300. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(17)33293-2.

- Troeger CE, Blacker BF, Khalil IA, Zimsen SRM, Albertson SB, Abate D, Abdela J, Adhikari TB, Aghayan SA, Agrawal S, et al. Mortality, morbidity, and hospitalisations due to influenza lower respiratory tract infections, 2017: an analysis for the global burden of disease study 2017. Lancet Resp Med. 2019;7(1):69–89. doi:10.1016/S2213-2600(18)30496-X.

- Blank PR, van Essen GA, Ortiz DLR, Kyncl J, Nitsch-Osuch A, Kuchar EP, Falup-Pecurariu O, Maltezou HC, Zavadska D, Kristufkova Z, et al. Impact of European vaccination policies on seasonal influenza vaccination coverage rates: an update seven years later. Hum Vacc Immunother. 2018;14(11):2706–14. doi:10.1080/21645515.2018.1489948.

- Kassianos G, Cohen JM, Civljak R, Davidovitch N, Pecurariu OF, Froes F, Galev A, Ivaskeviciene I, Koivumagi K, Kristufkova Z, et al. The influenza landscape and vaccination coverage in older adults during the SARS-Cov-2 pandemic: data from several European Countries and Israel. Expert Rev Resp Med. 2024;18(3–4):1–16. doi:10.1080/17476348.2024.2340470.

- Schmid P, Rauber D, Betsch C, Lidolt G, Denker ML. Barriers of influenza vaccination intention and behavior - a systematic review of influenza vaccine hesitancy, 2005 - 2016. PLOS ONE. 2017;12(1):e0170550. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0170550.

- Zhang Y, Wang X, Li Y, Ma J. Spatiotemporal analysis of influenza in China, 2005-2018. Sci Rep-Uk. 2019;9(1):19650. doi:10.1038/s41598-019-56104-8.

- Dong K, Gong H, Zhong G, Deng X, Tian Y, Wang M, Yu H, Yang J. Estimating mortality associated with seasonal influenza among adults aged 65 years and above in China from 2011 to 2016: a systematic review and model analysis. Influenza Other Resp. 2023;17(1):e13067. doi:10.1111/irv.13067.

- Technical guidelines for seasonal influenza vaccination in China (2023-2024). Zhonghua Liu Xing Bing Xue Za Zhi. 2023;44(10):1507–30. doi:10.3760/cma.j.cn112338-20230908-00139.

- Zhao HT, Peng ZB, Ni ZL, Yang XK, Guo QY, Zheng JD, Qin Y, Zhang YP. Investigation on influenza vaccination policy and vaccination situation during the influenza seasons of 2020-2021 and 2021-2022 in China. Zhonghua Yu Fang Yi Xue Za Zhi. 2022;56(11):1560–4. doi:10.3760/cma.j.cn112150-20220810-00802.

- Yang J, Atkins KE, Feng L, Pang M, Zheng Y, Liu X, Cowling BJ, Yu H. Seasonal influenza vaccination in China: landscape of diverse regional reimbursement policy, and budget impact analysis. Vaccine. 2016;34(47):5724–35. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2016.10.013.

- Che X, Liu Y, Gu W, Wang F, Wang J, Jiang W, Du J, Zhang X, Xu Y, Zhang X, et al. Analysis on the intention and influencing factors of free influenza vaccination among the elderly people aged 70 and above in Hangzhou in 2022. Front Public Health. 2022;10:1052500. doi:10.3389/fpubh.2022.1052500.

- Chen H, Li Q, Zhang M, Gu Z, Zhou X, Cao H, Wu F, Liang M, Zheng L, Xian J, et al. Factors associated with influenza vaccination coverage and willingness in the elderly with chronic diseases in Shenzhen, China. Hum Vacc Immunother. 2022;18(6):2133912. doi:10.1080/21645515.2022.2133912.

- Xu C, Lao X, Li H, Dong L, Zou S, Chen Y, Gu Y, Zhu Y, Xuan P, Huang W, et al. Incidence of medically attended influenza and influenza virus infections confirmed by serology in Ningbo City from 2017-2018 to 2019-2020. Influenza Other Resp. 2022;16(3):552–61. doi:10.1111/irv.12935.

- Kong G, Lim NA, Chin YH, Ng Y, Amin Z. Effect of COVID-19 pandemic on influenza vaccination intention: a meta-analysis and systematic review. Vaccines-Basel. 2022;10(4):606. doi:10.3390/vaccines10040606.

- Nogareda F, Gharpure R, Contreras M, Velandia M, Lucia PC, Elena CA, Azziz-Baumgartner E, Salas D. Seasonal influenza vaccination in the Americas: progress and challenges during the COVID-19 pandemic. Vaccine. 2023;41(31):4554–60. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2023.06.024.

- Ma L, Han X, Ma Y, Yang Y, Xu Y, Liu D, Yang W, Feng L. Decreased influenza vaccination coverage among Chinese healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic. Infect Dis Poverty. 2022;11(1):105. doi:10.1186/s40249-022-01029-0.

- Li K, Yu T, Seabury SA, Dor A. Trends and disparities in the utilization of influenza vaccines among commercially insured US adults during the COVID-19 pandemic. Vaccine. 2022;40(19):2696–704. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2022.03.058.

- Sulis G, Basta NE, Wolfson C, Kirkland SA, McMillan J, Griffith LE, Raina P. Influenza vaccination uptake among Canadian adults before and during the COVID-19 pandemic: an analysis of the Canadian longitudinal study on aging (CLSA). Vaccine. 2022;40(3):503–11. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2021.11.088.

- Du Y, Jin C, Jit M, Chantler T, Lin L, Larson HJ, Li J, Gong W, Yang F, Ren N, et al. Influenza vaccine uptake among children and older adults in China: a secondary analysis of a quasi-experimental study. BMC Infect Dis. 2023;23(1):225. doi:10.1186/s12879-023-08145-8.

- Bianchi FP, Cuscianna E, Rizzi D, Signorile N, Daleno A, Migliore G, Tafuri S. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on flu vaccine uptake in healthcare workers in Europe: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Expert Rev Vaccines. 2023;22(1):777–84. doi:10.1080/14760584.2023.2250437.

- Liang X, Li J, Fang Y, Zhang Q, Wong M, Yu FY, Ye D, Chan PS, Kawuki J, Chen S, et al. Associations between COVID-19 vaccination and behavioural intention to receive seasonal influenza vaccination among Chinese older adults: a population-based random telephone survey. Vaccines-Basel. 2023;11(7):1213. doi:10.3390/vaccines11071213.

- You Y, Li X, Chen B, Zou X, Liu G, Han X. Knowledge, attitude, and practice towards influenza vaccination among older adults in Southern China during the COVID-19 pandemic. Vaccines-Basel. 2023;11(7):1197. doi:10.3390/vaccines11071197.

- Wang Q, Yue N, Zheng M, Wang D, Duan C, Yu X, Zhang X, Bao C, Jin H. Influenza vaccination coverage of population and the factors influencing influenza vaccination in mainland China: a meta-analysis. Vaccine. 2018;36(48):7262–9. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2018.10.045.

- Yang J, Atkins KE, Feng L, Baguelin M, Wu P, Yan H, Lau E, Wu JT, Liu Y, Cowling BJ, et al. Cost-effectiveness of introducing national seasonal influenza vaccination for adults aged 60 years and above in mainland China: a modelling analysis. BMC Med. 2020;18(1):90. doi:10.1186/s12916-020-01545-6.

- Feng LZ, Peng ZB, Wang DY, Yang P, Yang J, Zhang YY, Chen J, Jiang SQ, Xu LL, Kang M, et al. Technical guidelines for seasonal influenza vaccination in China, 2018-2019. Zhonghua Liu Xing Bing Xue Za Zhi. 2018;39(11):1413–25. doi:10.3760/cma.j.issn.0254-6450.2018.11.001.

- Yi B, Zhou S, Song Y, Chen E, Lao X, Cai J, Greene CM, Feng L, Zheng J, Yu H, et al. Innovations in adult influenza vaccination in China, 2014-2015: leveraging a chronic disease management system in a community-based intervention. Hum Vacc Immunother. 2018;14(4):947–51. doi:10.1080/21645515.2017.1403704.

- Ye L, Chen J, Fang T, Cui J, Li H, Ma R, Sun Y, Li P, Dong H, Xu G. Determinants of healthcare workers’ willingness to recommend the seasonal influenza vaccine to diabetic patients: a cross-sectional survey in Ningbo, China. Hum Vacc Immunother. 2018;14(12):2979–86. doi:10.1080/21645515.2018.1496767.

- Watkinson RE, Williams R, Gillibrand S, Munford L, Sutton M, Grais RF. Evaluating socioeconomic inequalities in influenza vaccine uptake during the COVID-19 pandemic: a cohort study in Greater Manchester, England. PLoS Med. 2023;20(9):e1004289. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1004289.

- Jiang X, Wang J, Li C, Yeoh EK, Guo Z, Wei Y, Chong KC. Impact of the surge of COVID-19 omicron outbreak on the intention of seasonal influenza vaccination in Hong Kong: a cross-sectional study. Vaccine. 2023;41(49):7419–27. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2023.11.006.

- Wang G, Yao Y, Wang Y, Gong J, Meng Q, Wang H, Wang W, Chen X, Zhao Y. Determinants of COVID-19 vaccination status and hesitancy among older adults in China. Nat Med. 2023;29(3):623–31. doi:10.1038/s41591-023-02241-7.

- Technical guidelines for seasonal influenza vaccination in China (2021-2022). Zhonghua Liu Xing Bing Xue Za Zhi. 2021;42(10):1722–49. doi:10.3760/cma.j.cn112338-20210913-00732.

- Bodeker B, Remschmidt C, Schmich P, Wichmann O. Why are older adults and individuals with underlying chronic diseases in Germany not vaccinated against flu? A population-based study. BMC Public Health. 2015;15(1):618. doi:10.1186/s12889-015-1970-4.

- Trombetta CM, Gianchecchi E, Montomoli E. Influenza vaccines: evaluation of the safety profile. Hum Vacc Immunother. 2018;14(3):657–70. doi:10.1080/21645515.2017.1423153.

- Liu J, Riyanto YE. The limit to behavioral inertia and the power of default in voluntary contribution games. Soc Choice Welfare. 2017;48(4):815–35. doi:10.1007/s00355-017-1036-x.

- Yeo M, Seo J, Lim J, Yon DK. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic and the expansion of free vaccination policy on influenza vaccination coverage: an analysis of vaccination behavior in South Korea. PLOS ONE. 2023;18(2):e0281812. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0281812.

- Han K, Francis MR, Xia A, Zhang R, Hou Z. Influenza vaccination uptake and its determinants during the 2019-2020 and early 2020-2021 flu seasons among migrants in Shanghai, China: a cross-sectional survey. Hum Vacc Immunother. 2022;18(1):1–8. doi:10.1080/21645515.2021.2016006.

- Liu X, Peng Y, Chen Z, Jiang F, Ni F, Tang Z, Yang X, Song C, Yuan M, Tao Z, et al. Impact of non-pharmaceutical interventions during COVID-19 on future influenza trends in Mainland China. BMC Infect Dis. 2023;23(1):632. doi:10.1186/s12879-023-08594-1.

- World Health Organization. A checklist for respiratory pathogen pandemic preparedness planning [accessed]. 2023 Dec 8. https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/374876/9789240084513-eng.pdf?sequence=1.

- World Health Organization. Seasonal influenza vaccination: developing and strengthening national programmes - policy brief [accessed]. 2023 Nov 24. https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/374324/9789240084636-eng.pdf?sequence=1.