ABSTRACT

Interurban commercial bus drivers are confronted with inherent risk of over speeding, road curvature, road geometry, and weather condition predisposing them to Road Traffic Crashes (RTCs). Lived experiences of inter-urban commercial bus drivers involved in RTCs in Ghana remains relatively underreported. This relates to their experiences and opinions on the causes of RTCs and the post-experiences as survivors. This paper is an exploratory qualitative study involving face-to-face in-depth interviews with 15 interurban commercial bus drivers who survived RTCs and still drive. The sample was a mix of purposive and snowball sampling techniques at the terminals/stations of interurban commercial bus drivers in Cape Coast, the Capital city of Central Region. The analysis revealed environmental factors (such as weather condition, road surface, road curvature) accounted for the RTCs. Survivors received poor pre-hospital trauma care and no welfare package. Measures to RTCs could include road/transport infrastructure improvements and survivors are to be provided with social welfare package.

1. Introduction

Globally, Road Traffic Injuries (RTIs) rank as the eight leading cause of death and account for the majority of deaths for young people aged 15–29 (Murray, Ehlers, & Mayou, Citation2002). With the current trend by 2030, Road Traffic Deaths (RTDs) will become the fifth killer disease unless an urgent action is taken (WHO, 2015). According to the WHO (2015) report, eighty eight countries have reduced the number of deaths on their roads with RTDs still unacceptably high at more than 1.2million annually. The highest of these RTDS are in the low and middle income countries particularly in Africa. Road Traffic Injuries and Deaths(RTI&Ds) cause economic losses of up to 5% of Gross Domestic Product in low and middle-income countries (WHO, 2015).

Poor enforcement of Road Traffic Regulations is considered to account for high burden of RTCs in low and medium-income countries in general and Ghana in particular as well as the growth in the numbers of motor vehicles (Museru & Leshabari, Citation2002; Nantulya &Reich, Citation2002). Ghana was rated as the second highest Road Traffic Crashes (RTCs) prone country among six West African countries, with 73 deaths per 1000 accidents in 2001 (Haadi, Citation2012). From 2001–15, an estimated average of 6 and 1,900 deaths daily and annually are recorded in Ghana (Teye Kwadjo et al., Citation2013). Ghana loses about 1.7 percent of its Gross Domestic Product (GDP), which is over $230 million dollars yearly besides the loss of lives to RTCs (National Road Safety Commission [NRSC], Citation2012; WHO, 2015).

There are three broad causes of RTCs -human, environmental and vehicular (Aikins & Abane, Citation2015). Of these human factors (such as over-speeding, substance misuse, and wrongful overtaking) account for almost 85% of the RTCs (Aikins & Abane, Citation2015). The environmental factors such as weather condition, road geometry and road surface) account for more than 12% with vehicular causes (such as defective car parts; broken down vehicles) making up the remaining 3% (Ackaah &Adonteng, Citation2011).

Available statistics in Ghana reveals that 53% of the fatalities associated with RTCs involved occupants of vehicles (NRSC, Citation2015; Thompson, Citation2014). Thus, many travelers never return home alive, end up being hospitalized for months/years, or sometimes suffer long-term disability (Ackaah & Adonteng, Citation2011; Yankson et al., Citation2010). The remaining 47% of the fatalities involve pedestrians, motorcyclists and cyclists in that order. Commercial drivers are overtly involved in such RTCs resulting in fatalities because of the associated risks of driving on highways for long distances, over speeding, fatigue from long driving, weather condition and road curvature (Ackaah & Adonteng, Citation2011; Damsere-Derry, et al., Citation2008; Morrow & Crum, Citation2004; Olvera, Guézéré, Plat, & Pochet, Citation2015).

The likelihood of these commercial drivers being injured/maimed or dying portends danger for the well-being of families, local communities and the nation because they constitute the manpower needed to contribute to the economic wealth of these families, communities and the nation at large (Sabet et al., Citation2016; Teye-Kwadjo et al., Citation2013). For each interurban commercial driver killed in an RTC, three or more other people are also killed (Ackaah & Adonteng, Citation2011; Donkor, Citation2014).

A number of studies have been conducted on incidence of RTCs involving commercial drivers in Ghana (Abimah, Citation2013; Damsere-Derry et al., Citation2008; Osei, Citation2016; Teye-Kwadjo, Citation2010). Damsere-Derry, Afukaar, Donkor and Mock, (Citation2008) assess the prevalence RTCs involving interurban commercial drivers in Ghana. Teye-Kwadjo (Citation2010) determine the risk perception, traffic attitudes and behaviour of commercial minibus drivers in Ghana. Abimah (Citation2013) considers approaches to changing road safety behaviors of commercial drivers in Ho Municipality, Ghana with Osei (Citation2016) investigating how driver attitudes and vehicle behaviours contribute to RTCs on the Kumasi-Dunkwa trunk road. Human factors such as speeding, aggressive driving and lastly fatigue were found to be the main causes of RTCs in these studies.

However, none of these studies assesses the lived experiences of commercial drivers who survived RTCs. The lived experiences entail the experiences and opinions of survivors on the causes of the RTCs, pre and post-hospital care. The public health and economic impact of RTCs and the resultants effects can be incalculable in developing countries like Ghana owing to the poorly developed trauma care systems and nonexistent social welfare infrastructure to accommodate the needs of the injured and the disabled drivers (Hazen & Ehiri, Citation2006). Therefore, there is a need to assess lived experiences of interurban commercial bus drivers who survived RTCs. It is also expedient to know, the drivers’ opinions of the causes of RTCs, pre and post-hospital care. This when ascertained in relation to the socio-demographic characteristics (such as age, years of driving experience and marital status) will shed more lights on the vicissitude of RTCs. The findings of the study will inform policy on the provision of ambulance services and health care facilities in the Region to ensure that RTC victims receive prompt and professional care. The study will also bring to the fore the testimonies of survivors on the unintended injuries (Peden, Scurfield, Sleet, Mohan, & Hyder et al., Citation2004).

2. Data and methods

2.1. Study area

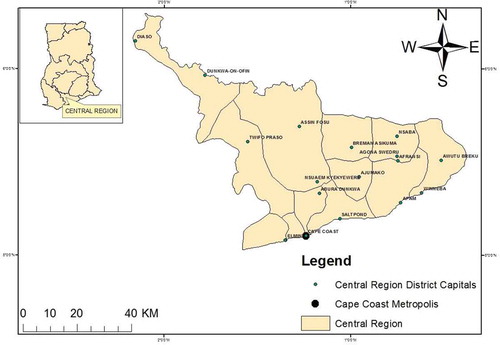

The Central Region is one of the ten administrative regions in Ghana as shown in . It is bordered by the Ashanti and Eastern regions to the north, Western region to the west, Greater Accra region to the east, and to the south by the Atlantic Ocean. Central Region with these regions accounts for more than 50% of RTCs in Ghana (National Road Safety Commission (NRSC), Citation2015). The region’s population is 1,593,823 with a growth rate of 2.1 percent per annum. The region is also the second most densely populated in the country, with a population density of 162 persons per square kilometre.

Figure 1. Map of Central Region, Ghana showing the different urban areas.

Source: GIS Unit, Department of Geography and Regional Planning, UCC.

All the socio-economic and political activities mentioned are aided mainly by road transport because of the virtual absence of rail and air services (Abane, Citation2010). Available statistics showed a decline in the incidence of pedestrian crashes in the Region in 2010 with a steady decline in the regional fatalities per 100,000 per year (NRSC, Citation2015). These statistics do not show the contribution of the commercial bus in general and interurban commercial bus in particular to the incidence of Road Traffic Injuries and Deaths (RTI&Ds) in the Region, but account for almost a fifth of RTCs in Ethiopia (Seid, Azazh, Enquselassie, & Yisma, Citation2015).

Different kinds of public transport operators offer interurban services in the Region. According to Abane (Citation2010), the safety records of drivers of these public operators (whether intra urban or interurban services) in the Region are poor as compared to other parts of the country. One thing lacking in Abane’s (Citation2010) study and other similar studies (such as Abimah, Citation2013; Aikins & Abane, Citation2015; DamsereDerry et al., Citation2008; Teye-Kwadjo, Citation2010) in Ghana is information on the experiences of survivors of RTCs in the Region.

2.2. Research design

The research design adopted for this study is an exploratory qualitative case study. This helps at bringing people to understand a complex issue or object and can extend experience or add strength to what is already known through previous research. It also generates theory that can be tested more widely through quantitative analysis. The subjective sensitive nature of this study is guided by interpretive phenomenological analysis orientation (Nnajjuma, Citation2013). To Smith, Flowers, and Larkin (Citation2009) this approach is concerned with exploring in detail how respondents are making sense of their ‘personal and social world’. It involves a detailed description of the respondents’ lived experience and exploration of personal experience(see Appendix). It is concerned with respondents’ perceptions or account of the object or happening phenomenon.

2.3. Target population and sample size

The target population included all interurban commercial drivers who have ever been involved in RTCs in which there occurred one or more injuries or deaths in Central Region (irrespective of a number of such occurrences). These are expected to be registered members of transport unions/operators in Central Region -i.e. Ghana Private Road Transport Union (GPRTU), Co-operative Society, Cape Coast FORD and Metro Mass Transit (MMT).

There was no data on the number of RTC victims by these operators. Therefore, the study focused on survivors in the last five years to take care of memory lapse. Qualitative studies on trauma care for RTCs victims in developing countries employed a smaller sample size (15 or 24) because of the subject of study (Hashan et al., Citation2010). Eventually, 18 survivors were contacted but 15 survivors agreed to take part in the survey.

2.4. Data collection procedures

To achieve the aim of the study, the researchers relied on the initial referrals of the station managers/operation managers of the interurban bus operators. Snowball sampling technique was later employed due to lack of record keeping on information of drivers who have ever been involved in RTCs (Howitt, Citation2010). Therefore, the station managers were the first of contact for the research team. They were introduced to the survivors and the survivors, in turn, referred the research team to fellow survivors.

A pilot study was conducted on intra-urban commercial bus drivers in the Cape Coast Metropolis. It was revealed that respondents felt restrained at the initial stage of the interview but more comfortable with time-sharing their experiences. A lot of prompts were required to make the respondents share their experiences. There was an incident of minor accidents that was largely ignored. The interview session was carried out between 10 to 20minutes. The drivers were interviewed at the terminals/stations where they operate.

The interview guide as shown in Appendix comprised questions on: respondents socio-demographic information questions such as gender, age, license category, years of experience, last recalled year of being involved in an accident; place of accident, time of accident; cause(s) of the accidents-environment factors; vehicular factors, and human factors as well as open questions them the opportunity to share their experiences regarding the RTC(see Appendix). Various prompts were used respectively at points when the broad question seemed lacking or as the situated evaluation dictated (Nnajjuma, Citation2013).

2.5. Data analysis

The data from 15 interviews were analyzed considering the following five stages suggested by Graneheim and Lundman (Citation2004) as follows:

Transcribing the whole interview immediately after completion;

Reading the text to gather an overall understanding of its content;

Determining meaning units and initial codes;

Classifying initial codes into more comprehensive categories, and finally; and

Determining hidden content of the data.

Each interview was transcribed on a daily basis to forestall memory loss on the part of the research team based on these stages and read severally to extract initial codes. The codes were later categorized based on similarities. Finally, hidden concepts and contents of the data were also extracted. The use of N-VIVO software might have been more convenient but thematic analysis was adopted because of the size of the data collected.

2.6. Ethical considerations

An introductory letter from the Department of Geography and Regional Planning was issued to the Transport Unions/Operators through the Trade Union Congress. However, the letter for MMT was sent directly to the Head Office in Accra. A copy of the letter was later shown to the station managers of the interurban terminals in Cape Coast where the respondents were surveyed.

Owing to the sensitive nature of the phenomenon under review, there were a psychologist and a counsellor available to handle any respondents who could psychologically re-experience the RTCs ordeal during the interview (Mayou, Ehlers, & Hobbs, Citation2000). The respondents were assured of confidentiality except he/she refused to be anonymous. Informed consent was obtained from the respondents. Respondents were also informed that the interviews were to be recorded and as such, they were free to decline to participate in the survey.

3. Results

The results are presented based on the headings below:

3.1. Cause(s) of the RTCs

The identified causes of RTCs are sharp curves, potholes, weather condition (rainfall), police checkpoint and a flat tyre on a raining day (). Most of the identified causes of RTCs were environmental factors with only one vehicular factor (flat tyre).

Table 1. Causes of RTCs.

3.2. Post RTC experience

The themes identified were a lack of pre-hospital care, inability to work/drive, lost wages/monthly income, memory haunting, and lack of welfare package (See ). These experiences place the RTCs victims in a dicey situation. The victims are transported to the health centre/hospital by Good Samaritans/lay people without training in a commercial bus not meant to convey this RTCs victim. Depending on the severity of the RTCs, some of the victims are unable to drive for long and sometimes end up losing their wages/income during the period of incapacitation. Often, there is a reliving of experience as they approach the site of the RTCs. The operators or Transport Unions do not have a welfare package to cater for hospital bills and other benefits that the victims may lose during the period of recuperation.

Table 2. Post RTCs experiences.

3.3. Suggestions to prevent RTCs

The themes identified for suggestions to prevent RTCs are road safety education for drivers, the presence of Motor Transport and Traffic Department (MTTD) and sanctioning of errant drivers by the Union leaders (see ). These themes can help in reducing the incidence of RTCs in the Region. Regular road safety education at the terminals will create a lasting memory of the danger associated with RTCs. The presence of the MTTD of the Ghana Police Service deters drivers from reckless driving with errant drivers fined or arrested. Commercial drivers are to report recalcitrant drivers to their union leaders for sanctioning.

Table 3. Suggestions to prevent RTCs and take care of survivors.

3.4. Suggestion to assist survivors

The themes identified were the provision of welfare package and insurance scheme for all interurban commercial drivers in the Region (see ). The welfare package can be in form of daily contribution by the drivers to a common purse or daily deduction from the sales of tickets. Any victims of RTCs can go to the pool for assistance depending on the nature of need. Insurance scheme can be initiated by the transport operators through sensitization by the insurance companies.

4. Discussion

This study sought to obtain the experiences and opinions of interurban commercial drivers who are survivors of RTCs, as to the causes of the RTCs, priorities for road safety efforts, and priorities for improving pre and post-RTC care. This study showed that the drivers felt that there was a preponderance of environmental factors contributing to RTCs. Their suggestions for road safety measures included improved training for commercial drivers and amelioration of environmental factors. Their suggestions for improving pre and post-RTC care emphasized increased access to ambulance services and development of social welfare protection by their unions.

Unlike previous studies conducted in Ghana (such as Abane, Citation2010; Aikins & Abane, Citation2015) that emphasized the dominance of human factors of RTC, the study supports Zhang, Yau, and Chen (Citation2013) that environmental factors are very important in road safety. These environmental factors are weather condition, road surface, road geometry and road curvature. Other environmental factors from extant literature are street-light condition, weather conditions, visibility level, whether the RTC occurred on a weekend, whether it was a public holiday, season and year of the accident, intersection design, signage, and traffic-calming measures (Aidoo, Amoh-Gyimah, & Ackaah, Citation2013; Aworemi et al., Citation2010; Zhang et al., Citation2013).

The weather condition is the most significant environmental cause of RTCs (Aworemi et al., Citation2010; Eisenberg, Citation2004; Eisenberg & Warner, Citation2005). Rainfall has been associated with an increased RTC risk (Eisenberg, Citation2004; Eisenberg & Warner, Citation2005; NRSC, Citation2015). Rainfall causes the road surface to be wet thus reduce friction and flowing or standing water can cause the vehicle to hydroplane (Morgan & Mannering, Citation2011). Eisenberg (Citation2004) found lagged effects to be important during precipitation events (e.g., if it rained yesterday and today, the number of rain-related RTCs would be lower today than it would be if it had not rained today).

Road maintenance such as filling of potholes and road resurfacing- plays an indispensable role in maintaining good road surface conditions and keeping roads safe (Usman, Fu, & Miranda-Moreno, Citation2010). Studies have revealed the association between road safety and road surface conditions resulting from the joint effects of weather and road maintenance on road safety (Andrey, Mills, & Vandermolen, Citation2001; Kumar & Wang, Citation2006). The pothole riddled roads allow rain water to settle on the road and poses a great threat to drivers. Besides, the road surface also becomes slippery, thus causing vehicles to skid off the road (Kumar & Wang, Citation2006; Usman et al., Citation2010; Zhang et al., Citation2013).

A very large proportion of RTI &Ds has been caused by loss of control on a bend or curve (Clarke, Ward, Bartle, & Truman, Citation2010; Wang, Quddus, & Ison, Citation2013). The number of curvatures on some of the routes (such as the Cape Coast-Accra and Cape Coast-Takoradi route) predisposes the interurban commercial drivers to RTCs. The thirteen curves on the Cape Coast- Accra route have claimed hundreds of lives and injured thousands since it was rehabilitated in the 1990s. Currently, there are road signs mounted at specific sections of the curvatures where scores of lives have been lost.

Studies have shown that the majority of RTCs occur at built-up areas but the locations of the black spots on the identified routes are far from settlements (Afukaar, Antwi, & Ofosu-Amaah, Citation2003; Seid et al., Citation2015). In the event of an RTC, Good Samaritan from the adjoining communities hurriedly run to assist/rescue RTC victims in the built up areas. The victims of RTCs on the highways are at the mercy of Good Samaritan motorists/lay people operating on the routes.

Emergency medical services and trauma care facilities assist in reducing the damage of RTCs and save lives (Abdul-Kadir, Citation2015; Chen, Citation2010). Many developing countries such as Ghana have insufficient pre-hospital trauma care with few victims receiving treatment at the crash scene and even fewer receive safe transport to the hospital by an ambulance. (M; Abdul-Kadir, Citation2015; Mock, Quansah, Krishnan, Arreola-Risa, & Rivara, Citation2004; Peden et al., Citation2004).

The gross inadequate number of ambulances operated by the Ghana Ambulance Service (GAS) compounds the fate of RTCs victims in the Region (GAS, 2017). Only two ambulances out of eight are operational in the Region. One of the ambulances is stationed on the Cape Coast-Praso route with the other one on the Cape Coast-Accra route. The length of the routes even makes the use of this ambulance service woefully inadequate. Therefore, RTCs victims are attended to by Good Samaritans/lay people and transported to the nearby health centres/hospitals in Good Samaritan vehicles (Abdul-Kadir, Citation2015; Kobusingye et al., Citation2005; Mock et al., Citation2004; Von Elm, Citation2004). These Good Samaritans/lay people when trained as first responders can help reduce RTI &Ds in (Abdul-Kadir, Citation2015).

The socio-demographic characteristics of the survivors raise concerns with all being male drivers, in their active age <60 years old and almost all married. It is really scarce to encounter female commercial interurban drivers in Ghana. This makes the sector a male dominated one predisposing them to the vagaries of the profession (Abane, Citation2010, Citation2010; Abimah, Citation2013; DamsereDerry et al., Citation2008; Teye-Kwadjo, Citation2010). The majority of these male survivors who are in their active age and are married contribute the economies of the Ghana by meeting the transport needs of the citizens (Damsere -Derry et al., Citation2008; Teye-Kwadjo, Citation2010).

Invariably, these survivors have dependents who will be worse hit by the vicissitude of RTCs. These bread winners may in turn have to depend on the family members because of the inability to save for raining resulting from meager wages/salaries. Without the support of the family members, they have to live on small gifts from colleagues.

5. Conclusions and recommendation

Based on the objectives set for the study, the study concludes that survivors feel that environmental factors (such as weather condition, road surface, road geometry, time of day) largely cause the RTCs. RTCs victims are at the mercy of Good Samaritans without adequate pre-hospital care and are transported to health centres/hospitals in Good Samaritan’s vehicles. There is no social welfare package for survivors and their families.

The National Road Safety Commission (NRSC) in collaboration with the officials of the MTTD of the Ghana Police Service should implement measures including road safety programs for interurban commercial drivers in the Region and focused enforcement of traffic regulation.

The Civil Engineers at the Ghana Highways Authority should consider Safety features prior to the construction of new roads and provide regular and periodic maintenance, with safety improvements (such as improving on road surfacing and filling the potholes).

The Government of Ghana through the Ministry of Health should resource the GAS with more ambulances and qualified personnel (such as paramedics) to handle pre-hospital trauma care in the Region. The GAS with the National Council for Civic Education (NCCE) can provide training for commercial drivers as first responders to reduce RTI&Ds in the region.

Transport Unions in the Region are to establish a social welfare package in form of an insurance scheme for their drivers. This social welfare package can be in form of daily contributions to cushion the effects of RTCs on the livelihoods of survivors and their dependents.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Abane, A. M. (2010). Background characteristics and accidents risk of commercial vehicle drivers in the cape coast-elmina area of the Central Region. The Oguaa Journal of Social Sciences 5, (1), 64–86.

- Abdul-Kadir, M. (2015). Training lay people as first responders to reduce road traffic mortalities and morbidities in Ethiopia: Challenges, barriers and feasible solutions (Unpublished Doctoral dissertation).

- Abimah, L. (2013). Assessing Approaches To Changing Road Safety Behaviours Of Commercial Drivers In Ho Municipality, Ghana.Unpublished Doctoral Thesis submitted to University of Ghana, Ghana

- Ackaah, W., & Adonteng, M. (2011). Crash prediction model for two-lane rural highways in the Ashanti region of Ghana. IATSS Research, 35(1), 34–40.

- Afukaar, F. K., Antwi, P., & Ofosu-Amaah, S. (2003). Pattern of road traffic injuries in Ghana: Implications for control. Injury Control and Safety Promotion, 10(1–2), 69–76.

- Aidoo, E. N., Amoh-Gyimah, R., & Ackaah, W. (2013). The effect of road and environmental characteristics on pedestrian hit-and-run accidents in Ghana. Accident Analysis & Prevention, 53, 23–27.

- Aikins, E. K. W., & Abane, A. M. (2015). Spatial Implications of the Yamoransa Mankessim coastal highway on pedestrian safety. Journal of Arts and Social Science, 3(1), 1–17.

- Andrey, J., Mills, B., & Vandermolen, J. (2001). Weather information and road safety. Toronto, Ontario, Canada: Institute for Catastrophic Loss Reduction.

- Aworemi, J. R., Abdul-Azeez, I. A., & Olabode, S. O. (2010). Analytical study of the causal factors of road traffic crashes in southwestern Nigeria. Educational Research, 1(4), 118–124.

- Chen, G. (2010). Road traffic safety in African countries–Status, trend, contributing factors, countermeasures and challenges. International Journal of Injury Control and Safety Promotion, 17(4), 247–255.

- Clarke, D. D., Ward, P., Bartle, C., & Truman, W. (2010). Killer crashes: Fatal road traffic accidents in the UK. Accident Analysis & Prevention, 42(2), 764–770.

- Damsere-Derry, J., Afukaar, F., Donkor, P., & Mock, N. C. (2008). Assessment of vehicle speeds on different categories of roadways in Ghana. International Journal of Injury Control and Safety Promotion, 15, 83–91.

- Donkor, K. B. (2014). 21 dead in accra-kumasi highway accident. Graphic Online. Retrieved November 15, 2016, from http://graphic.com.gh/news/general-news/29846-21-dead-in-accra-kumasi-highway accident.html.

- Eisenberg, D. (2004). The mixed effects of precipitation on traffic crashes. Accident Analysis & Prevention, 36(4), 637–647.

- Eisenberg, D., & Warner, K. E. (2005). Effects of snowfalls on motor vehicle collisions, injuries, and fatalities. American Journal Public Health, 95(1), 120–124.

- Graneheim, U. H., & Lundman, B. (2004). Qualitative content analysis in nursing research: Concepts, procedures and measures to achieve trustworthiness. Nurse Education Today, 24, 105–112.

- Haadi, A. R. (2012). Identification of Factors that Cause Severity of Road Accidents in Ghana: A Case Study of the Northern Region. Unpublished Doctoral Thesis submitted to Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology, Ghana.

- Hashan -Bidgoli, H., Hasselberg, M., Khankeh, H., Khorasani-Zavareh, D., & Johansson, E. (2010). Barriers and facilitators to provide effective pre-hospital trauma care for road traffic injury victims in Iran: A grounded theory approach. BMC Emergency Medicine, 10(1), 20.

- Hazen, A., & Ehiri, J. E. (2006). Road traffic injuries: Hidden epidemic in less developed countries. Journal of the National Medical Association, 98(1), 73.

- Howitt, D. (2010). Introduction to qualitative methods in psychology. Edinburgh gate, London: Pearson education Limited.

- Kobusingye, O. C., Hyder, A. A., Bishai, D., Hicks, E. R., Mock, C., & Joshipura, M. (2005). Emergency medical systems in low- and middle-income countries: Recommendations for action. Bull World Health Organ, 83, 626-631.

- Kumar, M., & Wang, S. (2006). Impacts of weather on rural highway Operations showcase evaluation # 2. Report.pdf. Retrieved June 26, 2017, from, http://www.coe.montana.edu/wti/wti/pdf/Final

- Mayou, R. A., Ehlers, A., & Hobbs, M. (2000). Psychological debriefing for road traffic accident victims. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 176(6), 589–593.

- Mock, C., Quansah, R., Krishnan, R., Arreola-Risa, C., & Rivara, F. (2004). Strengthening the prevention and care of injuries worldwide. Lancet, 363, 2172–2179.

- Morgan, A., & Mannering, F. L. (2011). The effects of road-surface conditions, age, and gender on driver-injury severities. Accident Analysis & Prevention, 43(5), 1852–1863.

- Morrow, P. C., & Crum, M. R. (2004). Antecedents of fatigue, close calls, and crashes among commercial motor-vehicle drivers. Journal of Safety Research, 35(1), 59–69.

- Murray, J., Ehlers, A., & Mayou, R. A. (2002). Dissociation and post-traumatic stress disorder: Two prospective studies of road traffic accident survivors. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 180(4), 363–368.

- Museru, L., Leshabari, M. T., & Mbembati, N. A. A. (2002). Patterns of road traffic injuries and associated factors among school-aged children in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania: Short research article. African Safety Promotion, 1(1), 37–41.

- Nantulya, V. M., & Reich, M. R. (2002). The neglected epidemic: Road traffic injuries in developing countries. BMJ: British Medical Journal, 324(7346), 1139.

- National Road Safety Commission (NRSC). (2012). Road traffic crashes reports in Ghana. Accra, National Road Safety Commision.

- National Road Safety Commission (NRSC). (2015). Road traffic crashes reports in Ghana. Accra. National Road Safety Commision

- Nnajjuma, H. (2013). Road Traffic Accidents in Uganda in view of Taxi Drivers Masaka District (Unpublished Master’s thesis), Norges teknisk-naturvitenskapelige universitet, Fakultet for samfunnsvitenskap og teknologiledelse, Psykologisk institutt.

- Olvera, L. D., Guézéré, A., Plat, D., & Pochet, P. (2015). Earning a living, but at what price? Being a motorcycle taxi driver in a Sub-Saharan African city. Journal of Transport Geography, 55, 165-174

- Osei, K. G. (2016). Investigating into driver attitudes and vehicle behaviours as contributory factors to road accidents on Kumasi-Dunkwa trunk road (Unpublished Doctoral Thesis submitted to University of Ghana).

- Peden, M., Scurfield, R., Sleet, D., Mohan, D., Hyder, A. (2004). World report on road traffic injury prevention. 2004. Geneva: WorldHealth Organization.

- Sabet, F. P., Tabrizi, K. N., Khankeh, H. R., Saadat, S., Abedi, H. A., & Bastami, A. (2016). Road traffic accident victims’ experiences of return to normal life: A qualitative study. Iranian Red Crescent Medical Journal.8(4),1-7.

- Seid, M., Azazh, A., Enquselassie, F., & Yisma, E. (2015). Injury characteristics and outcome of road traffic accident among victims at adult emergency department of Tikur Anbessa specialized hospital, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia: A prospective hospital based study. BMC Emergency Medicine, 15(1), 10.

- Smith, A., Flowers, P., & Larkin, M. (2009). Interpretive phenomenological analysis: Theory, method and research. London: Sage publication limited.

- Teye-Kwadjo, E., (2010). Risk perception, traffic attitudes and behaviour among pedestrians and commercial minibus drivers in Ghana: a case study of Manya Krobo district ( Master thesis), Norwegian university of and technology, Trondheim Norway.

- Teye-Kwadjo, E., Knizek, B. L., & Rundmo, T. (2013). Attitudinal and motivational aspects of aberrant driving in a West African country. tidsskrift for norsk psykologforening, 50, 451–461.

- Thompson, A. (2014). The aggravating trend of traffic collision casualties in Ghana from 2001 2011. Ritsumeikan Journal of Asia Pacific Studies, 33,132–138.

- Usman, T., Fu, L., & Miranda-Moreno, L. F. (2010). Quantifying safety benefit of winter road maintenance: Accident frequency modeling. Accident Analysis & Prevention, 42(6), 1878–1887.

- Von Elm, E. (2004). Prehospital emergency care and the global road safety crisis. JAMA : the Journal of the American Medical Association, 292, 923.

- Wang, C., Quddus, M. A., & Ison, S. G. (2013). The effect of traffic and road characteristics on road safety: A review and future research direction. Safety Science, 57, 264–275.

- Yankson, I. K., Browne, E. N., Tagbor, H., Donkor, P., Quansah, R., Asare, G. E., … Ebel, B. E. (2010). Reporting on road traffic injury: Content analysis of injuries and prevention opportunities in Ghanaian newspapers. Injury Prevention, 16(3), 194–197.

- Zhang, G., Yau, K. K., & Chen, G. (2013). Risk factors associated with traffic violations and accident severity in China. Accident Analysis & Prevention, 59, 18–25.

Appendix

In-depth Interview Guide

This in-depth interview is to elicit information on the lived experiences of intercity commercial bus drivers involved in Road Traffic Crashes. Any information offered is merely for an academic exercise. You are free to opt out if deemed necessary.

A. Socio-demographic characteristics of respondents

1. Gender

2. Age

3. Educational level

4. Monthly income

5. Mode of acquiring driving training

6. License weight

7. Years of experience

8. For how long do you work?

9. Marital Status

10. Number of wives

11. Place of residence of the spouse (if different from where the victim lives)

12. Number of Children

13. Educational level of the children

14. Place of residence of the children (if different from where the victim lives)

B. Experience of Road Traffic Crashes

15. Place of road traffic crashes

16. Time of traffic crashes

17. Cause(s) of the road traffic crashes -environment factors; vehicular factors, and human factors

18. Any casualty (deaths or injured persons)

C. Post Road Traffic Crashes

19. Any recall of the road traffic crashes (did you just find yourself at the hospital or –)

20. For how long where you hospitalized? (prompt)

21. How was the hospital bills settled? (prompt)

22. Was your employer still paying your monthly salaries when you were hospitalized (prompt)

23. When were discharged from the hospital?

24. What are the challenges you are confronted with after the Road Traffic Crashes? (prompt).

25. Do you still drive on intercity route? (prompt)

26. What are your post crash experiences?

D. Recommendations on how to prevent road traffic crashes and take care for victims like you.