ABSTRACT

Research shows a disparity continues to exist between women and men with regard to cycling behavior; women cycle at far lower rates. Cargo bikes have been suggested as one tool to increase the gender balance in bicycle ridership. This research evaluates this suggestion through the lens of: (1) an analysis of survey data regarding cargo bike usage by gender; and (2) interviews with women who use cargo bikes. Data from surveys and interviews explore the influence of cargo bikes on transportation patterns and how behavior, attitude, spatial context, and perception vary between riders. Results show that 78% percent of women used cargo bikes for trips with kids, vs. 56% of men. Qualitative work expands this and suggest that cargo bike use is likely tempered by access to a cargo platform, geography, cultured and rider experience. These results illustrate not only the powerful potential cargo bikes might have in shaping the travel patterns of the future, but also need to address issues in infrastructure and education that may pose impediments to female ridership.

Introduction

Although the United States tends to be an automobile-dominated culture, many attitudinal variables and gender differences play a role in mode choice (Baker, Citation2009). Differences in people’s attitudes and personality traits lead them to attribute varying importance to environmental considerations, safety, comfort, convenience, and flexibility when determining their choice in transport (Johansson, Heldt, & Johansson, Citation2006). In addition to individual differences, variances between gender groups in the rate of bicycle selection for trip purposes and the reasons for these differences will be important for increasing cargo bike ridership in the United States. Research shows that many of these differences reflect the different transportation patterns, needs, and purposes between women and men (Clark, Chatterjee, & Melia, Citation2015). Female bicyclists have different perceptions of safety and different trip purposes than male bicyclists. For women, safety concerns are influenced by both physical and social environments, they tend to make more trips for household and family activities/needs than men, many of which require the transport of goods or passengers like children (Akar, Flynn, & Namgung, Citation2012; Riggs, Rugh, Cheung, & Schwartz, Citation2016), while trips by men are largely job/commute oriented (Pucher & Buehler, Citation2012; Riggs, Citation2016).

This research looks at the influence of cargo bikes on transportation patterns and follows how behavior, attitude, spatial context, and perception vary between individual riders and gender groups. Specific attention is given to the use of cargo bikes by women with children, as this demographic represents a minority group in the bicycling community and a group who could benefit most from the capabilities of a cargo bike platform. This research was divided into two parts. First, data was collected from a nation-wide survey to explore trends and behaviors amongst cargo bike users using descriptive statistics. Second, interviews were conducted with female cargo bike riders who bike with children to further inform the function of a cargo bike as a family vehicle. The research objective is to better understand if the cargo bike is a feasible mode substitution for the automobile, specifically by the use of women, and what factors contribute to this substitution behavior. Information gathered from this research may then inform policies and environmental design decisions to best support cargo bike transportation for all user groups.

Literature

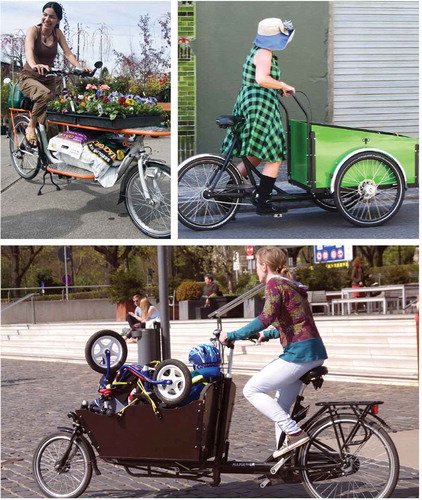

Cargo bikes (also referred to as freight bicycles, carrier cycles, freight tricycles, box bikes, longtails or cycletrucks as shown in ) are human-powered vehicles designed and constructed specifically for transporting loads (Riggs, Citation2015, Citation2016; Riggs & Schwartz, Citation2015). They have been in existence for almost as long as traditional bicycles and were originally used by shopkeepers to make local deliveries (Börjesson Rivera & Henriksson, Citation2014). In the Netherlands, for example, principle uses for cargo bikes include the transportation of children and goods. There is ample work that has been completed on these kind of bikes in the area of ity logistics. Studies have been completed in New York, Paris, London, Seattle, Portland, and Austin particularly for cargo, yet research lags in the area of use of the cargo bike for personal commutes (Choubassi, Citation2015; Masterson, Citation2017; Schliwa, Armitage, Aziz, Evans, & Rhoades, Citation2015). Research suggests that there are factors that influence mode choice selection and travel behavior (Handy, Boarnet, Ewing, & Killingsworth, Citation2002). Impacts of these factors are assumed to affect men and women differently due to physical and psychological differences between genders (Garrard, Handy, & Dill, Citation2012; Heesch, Sahlqvist, & Garrard, Citation2012).

Three factors that were discussed most frequently in research as influential factors of modal decisions include: the built environment, attitudes, behavior, and personality traits, and the distribution of male and female roles. The following literature will review the influences of each of these factors and help inform how gender-response differences lead to variances in mode choice selection and travel behavior, ending with existing research that has looked at the cargo bike as a transportation platform.

Since very little literature exists on cargo bikes in the United States, most of the following literature research focuses on traditional bicycle transportation and the behaviors influenced by this mode. However, this research identifies variables that influence mode choice and enlightens a new area of research to emerge, which looks specifically at women and the impact of the cargo bike on travel behavior.

The built environment and mode choice

The built environment is one of the most apparent impacts of mode choice, based on the physical presence of bicycle infrastructure and the observable design of the cityscape. The built environment is a multidimensional concept and comprises urban design, land use, transportation systems, and human activity within the physical environment (Handy et al., Citation2002). The impact of these variables influences modal decisions and human behavior. Impacts are tied to the type of environment of the community (i.e. rural, suburban, urban) and the local and regional characteristics (Chatman, Citation2009).

Research has suggested that the development of the built environment can be disempowering and even isolating toward women. For example, the separation of kitchen from living space in the house provides a physical barrier for women, just the traditional roles of women in child pick up and drop off at schools aligns with traditional of domestic labor roles household, and limits their type of travel (usually via car) and social networks (Fagan & Trudeau, Citation2014). Many women and their families choose neighborhoods based on their expected travel patterns, this is called the residential self-selection hypothesis (Chatman, Citation2009). Households choose where to live based on access to work and non-work activity locations, such as parks, shops, doctors’ offices, movie theaters, and child care. The characteristics of the built environment near homes and areas of child-related activities (e.g. school) influence auto dependency and the likelihood of bicycle mode choice. Depending on who in the household makes these trips most often and their level of comfort with using a bike for these trips, the built environment has the capability to positively influence the use of a biking mode. When investigating the comfort differences between men and women, the interdependence between residential locations, commute behavior characteristics, and attitude towards travel (Schwanen & Mokhtarian, Citation2005) should be considered.

The effects of attitudes, behavior, personality traits and mode choice

Differences in people’s attitudes and personality traits lead them to attribute varying importance to environmental considerations, safety, comfort, convenience, and flexibility when determining their choice in transport (Johansson et al., Citation2006). Gender differences in transport cycling include different transportation patterns, needs, and purposes of men and women. For example, women are generally more concerned with issues of safety, comfort, and accessibility, and are more likely to trip chain (combining multiple errands into one trip) as part of their commute because of their greater amount of responsibility for transporting children and to do household shopping (Heesch et al., Citation2012). They are also more likely to report other perceived environmental factors as constraints, such as traffic and transport issues, weather and climate conditions, as well as individual factors.

Few studies have investigated women’s perceptions and experiences of cycling and little is known about what motivates and sustains their involvement in cycling in general, let alone the use of a cargo bike platform. Some work suggests that cargo bikes can provide a tool for mode substitution behavior on a day-to-day travel basis (Riggs, Citation2016), and other work suggests that commute patterns and attitudes are more likely to change during major life/life stage events (Clark et al., Citation2015). Literature indicates that things like having a child (of which are traditionally responsible), taking a new job or moving to a new residential location are connected to commute change.

The distribution of male and female roles and mode choice

Why are there gender differences in rates of bicycling? Women are more heavily impacted by some of these impediments than men because of women’s greater responsibility for domestic tasks, like shopping (Bonham & Wilson, Citation2012). Providing additional empirical insight on how gender influences the decision to use a bicycle will help increase bicycle ridership in communities, particularly amongst women. Behavior related to mode selection as well as how bicycle use differs among genders is influenced by individual, social, and physical factors. The existing research on cargo bikes looks particularly at the impact of a cargo bike type on individual behavior. In a broad sense, individual factors include attitudes, preferences, and beliefs, as well as confidence/self-efficacy (Emond, Tang, & Handy, Citation2009). Based on these two factors relevant to gender differences are concern for/perceptions of safety and household responsibility. Commuting by car has been found to be associated with having children, having greater access to household cars, living in a multi-occupancy household, having greater income, being self-employed, and being female (Clark et al., Citation2015).

Some scholars have connected concepts of difference, exclusion, access, and justice with concrete issues of daily movement (Law, Citation1999). Daily mobility incorporates a range of issues central to human geography, such as unequally distributed resources and the experience of social interactions in transport-related settings. Gender norms of domestic responsibility look at the impact of temporal rhythms of childcare, domestic work, and the spatial patterns of segregated land-uses on the restricted mobility of women. Until child care and household responsibilities are shared equally by women and men likewise the responsibility to be employed outside of the home is equal amongst genders (Eagly & Steffen, Citation2000), it is assumed that women will continue to take on more responsibility for the needs of their children and family.

Methodology

As indicated in the literature, research on and the use of cargo bikes in the United States (US) is limited, but a necessity given the continued gender differences and biases that exist in the country. Despite scarcity, conducting research on American behavior with the cargo bike provides relevant information and the opportunity to expose the impacts of this modal option. The research includes two windows of assessment: starting with a comparative analysis of male and female cargo bike users before and after purchase of a bike; and then focusing on interviews with female riders.

Part I: survey

In mid-2015, a survey was issued to an email list of roughly 2,500 individuals who had recently made a purchase (Riggs & Schwartz, Citation2015). Yuba Bicycles, a leading vendor of cargo bikes in the US, provided the list through a relationship facilitated by a California-based vendor, Cambria Bicycle Outfitters. While this was a potential limitation of the study in that it focused primarily on one particular manufacturer and consisted of individuals who had chosen to purchase a cargo bike, it had a few advantages in the study of use and modal decisions: 1) they only manufacture cargo bikes that are distributed both in the US and internationally; 2) they offer numerous cargo bike platforms for buyers to choose from (e.g. rear, electric, front-loading, small); and 3) they offer a product that is more cost-effective than other manufacturers, helping address potential limitations of cost (i.e. concerns that only the affluent can afford a cargo bike).Footnote1 While these results might vary if the general population/non-buyers were surveyed, given that the focus of this work was to explore the challenges of those who desire to cycle via cargo bike, this limitation was counterbalanced by a follow-on qualitative evaluation.

Surveys took approximately 10 minutes to complete and explored three factors: 1) trip mode before and after the purchase of a cargo bike (e.g. auto, transit, traditional bike, cargo bike, walk, other); 2) trip type (work, school, other); and 3) individual characteristics and preferences, focusing acutely on trips involving children. Respondents were first asked a series of questions about their travel behavior before they owned a cargo bike. They were then asked about their behavior after owning the cargo bike, using the same sequence of questions.

Roughly 300 responses were received and a subset of 173 valid responses were assessed using descriptive statistics and crosstabs to look for associations. A valid response included someone who had both responded as having owned a cargo bike and also indicated a gender of either a male or female gender.Footnote2 For the purposes of this work, other gender classifications were not made available. The responses were assessed for the entire population, as well as by subsets like gender – exploring the different changes in behavior after owning a cargo bike.

The margin of error was ±6% at the 95% confidence interval. The survey complied with all human subject requirements and all responses were anonymous.

Part II: interviews with women

Following the survey, to gather a more detailed assessment of a woman’s experience on and with the cargo bike, in-person interviews were conducted. The interviews were targeted toward, women who currently use a cargo bike as a transportation mode in the City of San Luis Obispo, California. The location was selected due to the large number of cyclists in the community relative to its’ size, as well as the communities’ temperate climate with little weather variation, and moderately hilly geography both of which pose a principle limitation cycling behavior (Cervero & Duncan, Citation2003) and are minimized in this case. The City of San Luis Obispo is recognized as being a bikeable city (recently rated Gold Bicycle Friendly Community by the League of American Bicyclists) with an above-average proportion of well-educated residents and bicycle commuters, which together, are recognized as influential factors that will be noted in conclusions made as a result of the findings.

However, while geography and culture have an impact on an individual’s biking experience, interview focused heavily on an experiential perspective of using the cargo bike and the influence of environmental conditions and family responsibility, which can be translatable across other communities and women. This is consistent with the qualitative mentality of Flyvberg who would argue that a focused and small number of cases can allow research to explore ‘little questions,’ focus on ‘values’ and develop a feel for the irrationality of human behavior that ‘moves beyond agency and structure’ (Flyvbjerg, Citation2001, Citation2006).

Participants for this extended study were found through snowball sampling and interviewed usually at the interviewee’s residence. Several women who use a cargo bike with their child(ren) were recommended to the research team. These women agreed to be interviewed and helped refer the research team to other women who also use a cargo bike. Interviews were structured according to questions based on these five (5) main categories: 1) introduction (to the bike, rider, and family); 2) transportation and behavior (primary use and reasons for riding); 3) safety and perception (level of comfort and discomfort); 4) demographics; and 5) open-ended comments.

In total, nine (9) women were interviewed, eight (8) of which currently own a cargo bike and ride with children, a sample that arguably be called small, but when taken as a whole provide a ‘thick’ and well-rounded understanding of experience with a large level of saturation and is consistent with the justification that small samples (or N = 1) can have the same if not more validity that large ones (Mira Crouch & Heather McKenzie, Citation2006; Edgar & Billingsley, Citation1974; Small, Citation2009). The women were between the ages of 37–44, and had a family size between three and five people. All of the women had either a bachelor’s or master’s degree and an average household income of approximately $140,000. The majority considered themselves experienced bicycle riders and bicycle advocates. While this level of experience may not normative in all communities, it does allow us to infer how an experienced cargo-bike cyclist engages in travel. Furthermore, consistent with Small, this allows for the qualitative work experience to be representative of a series of experiences that are not representative of all things to all people but of different things to different people, raising questions and bringing about opportunity for dialogue and discussion.

Survey results

The results from the survey look at participant responses from before and after the ownership of a cargo bike to assess how the cargo bike has influenced the travel behaviors for both men and women. As stated in the methodology for this part of the study, three factors represent the focal criteria for observing changes before and after cargo bike ownership: trip mode, trip type, and individual characteristics and preferences. The final part to the survey assessment looks at open-ended responses that help describe the implications of cargo bike use for both men and women. Together, the following sections analyze the response comparison between genders before and after cargo bike purchase and whether there are changes in primary mode choice and trip purposes, such as the share of child-related trips.

Before a cargo bike

Before owning a cargo bike, participants were asked to think about their primary travel mode, the purposes of trips made with their primary travel mode, and if children were on these trips. As shown in , a majority of both men and women commuted by ‘car/truck/auto’ before ownership of a cargo bike, followed by a ‘traditional bicycle’ as the second most common primary mode. However, a much greater percentage of men used a ‘traditional bicycle’ as their primary mode for travel with 39 (36.1%) of the male participants reporting this use. Each of the other mode options, ‘bus/transit’, ‘walking’, or ‘other’ (e.g. bike and subway; motorcycle, etc.), were reported below 6.0% for each gender response group. Prior to owning a cargo bike, participants were asked what their primary purpose was for using their primary commute mode. 156 (68.1%) of the participants reported ‘work’, 25 (10.9%) reported ‘school’, and 48 (21.0%) reported ‘other’. This included things such as errands, dropping a child off at school, going to the gym, or taking part in a child activity.

Table 1. Primary travel mode prior to owning a cargo bike.

Looking at the gender comparison for the primary mode and the purpose for trips men and women used cargo bikes differently. and illustrate the transportation patterns of men as opposed to women. Responses show that both are heavily dependent on a ‘car/truck/auto’ as their primary travel mode to work. 44 (40.7%) men and 24 (36.9%) women reported using a vehicle as their primary mode for work purposes. Across all three trip purposes (‘work’, ‘school’, ‘other’), 56 (51.9%) men depended on a vehicles, versus 46 (70.8%) women. With regard to bikes, 39 (36.1%) men said that they use a traditional bicycle as their primary mode for all three trip purposes, versus only 12 (18.5%) women.

Over half of the respondents reported having children as a part of their home. Survey participants were also asked if children came on trips before ownership of a cargo bike. This revealed that 37.2% of men used of a ‘traditional bicycle’ to transport children, while only 18% of women transported children on a bike.

After a cargo bike

In comparison to primary mode choice prior to owning a cargo bike, 133 (69%) of all respondents reported that the cargo bike became their primary mode of travel after purchase. This yields potential for a 40% reduction in car use for daily trips, consistent with the findings of Riggs (Citation2016) which grappled with the mode-shift potential of cargo bikes using all trips in the same data set. For the sample, the total number of bike riders (cargo and other) rose from 65 (28.0%) to 154 (79.4%). A total of 133 (68.9%) participants reported that this cycling behavior was a change from how they traveled prior to owning a cargo bike. A total of 60 (31.1%) participants said that their primary transportation patterns did not change, despite the new ownership of a cargo bike, however the data show many of these individuals were already bike riders (e.g. cargo bike substituted a traditional bike).

When looking at the difference between genders, both men and women saw a decrease in all other modes as a result of the introduction of a cargo bike. As shown in , the cargo bike emerged as the primary travel mode for both gender groups. The women’s group saw the greatest changeover with over half of all trips originally made by a ‘car/truck/auto’ as now being made by a ‘cargo/utility bicycle’.

When asked what the primary purpose of these trips were, most (113 or 59.8%) said it was for ‘work’, 25 (13.2%) said it was for ‘school’, and 45 (27.0%) described other reasons such as having fun with kids, errands, and appointments. For both men and women, the cargo bike became the primary vehicle for trips including children, with a majority of women continuing to report that children are included on a majority of all trips made across all mode types.

A total of 40 (56.3%) men and 39 (78.0%) women reported using the cargo bike on trips with children (numbers reflect counts from all participants – not only those who reported that they have children). It is assumed that the high percentage of women utilizing the cargo bike for both ‘work’ purposes as well as the transportation of children is a result of women performing more trip-chaining (making many trips and errands out of one long trip) and relying on either a cargo bike or a car/truck/auto to be able to accommodate the diversity of trip purposes and needs.

Interview results

The second part of the study focused on interviews with women. As indicated previously, while this survey was limited to 9 individuals it focuses on values and revealing experiences – looking openly and carefully at individual cases with less of a desire to prove something than to learn something (Flyvbjerg, Citation2006). This focus on exploratory cases came as a result of survey data which illustrated how women, when given the option, often choose to ride a cargo bike over driving a car/truck/auto, even if children are included on trips. Interviews with women who use the cargo bike platform helped to inform the idea of what contributes to the mode choice decision-making process, as well as provide a more well-rounded understanding of how women interact with cargo bikes on a day-to-day basis. Consistent with feminist theory, we used pseudonyms both humanize and help retain the female identity of our respondents.

In sum, when asked to describe themselves, many spoke about where they went to school, where they work or volunteer, and any community activities they are a part of. Seven (7) out of the nine (9) women had either their bachelor’s or master’s degree. Three (3) of the women had full-time jobs, while six (6) women worked part-time and/or stayed at home. Women also expressed interests in gardening, participation in the local Bike Coalition, and family activities. Each woman interviewed used she/her pronouns, was a part of a heterosexual marriage or partnership, and had between one and three children. All the women who used their cargo bike for transporting their children had kids of or below age eight.

Each of the participants had owned their cargo bike for at least six months, and several women identified the time it took to feel comfortable riding their cargo bike with their kids around town. Seven (7) women said that they had two cars in their household and two (2) women said that their household had one (1) car. A majority added that use of the car in the local setting was used almost exclusively for trips with many items to carry or events where there was not enough time to trip chain on the cargo bike. Lastly, the cargo bike model that each mom rode varied between Yuba, Xtracycle, Larry vs Harry, and the Christiania Dutch-style cargo bike.

Each woman was asked to think about her use of a vehicle and discuss whether she and her family had considered giving up a car/truck/auto as a result of the cargo bike, and if not, what would it take to get them to do so. Although many felt that they had shared responsibilities with their male partners, all stated that they took primary responsibility traditional role of traveling with kids, and furthermore took pride in the one their role and that they did it via cargo bike – almost as if it empowered them beyond the traditional role.

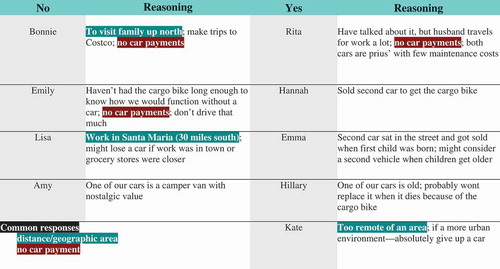

illustrates this sentiment in the responses and reasoning for why women (as opposed to their partners) considered cargo bikes. Over half of the group said, they had considered giving up a vehicle, or had already given up a vehicle. Limitations to not giving up a car included work location, and an inability to depend on a cargo bike for all their errands. Further, most felt that they thought they might experience some financial savings that would justify getting rid of car/shedding a car for their family, but that this was not clear for them in the end. A comment from Emma, currently a single-vehicle household, described how a second vehicle might be purchased in the future illustrates this point. Emma and her partner felt that as her children aged, they had more activities. They felt they might need another car to address these growing trip demands.

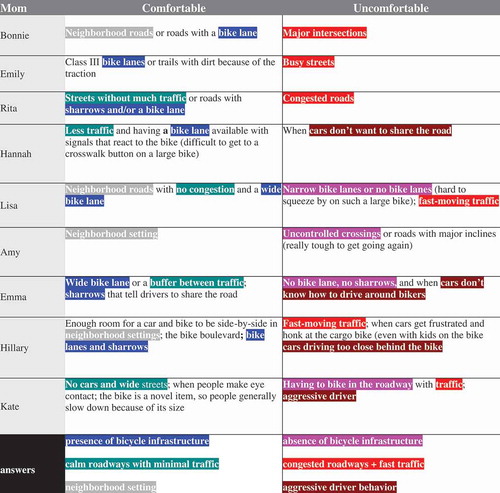

When asked about comfort when using a cargo bike, the women interviewed largely cited streetscape improvements, rather than elements of the bike, as key elements contributing to a more comfortable experience while riding. The elements they mentioned included things like: calm roadways with minimal traffic; the presence of bicycle infrastructure (e.g. bike lanes, sharrows; informative signage for automobiles to understand how to share the road with bicyclists); biking on a dedicate street, lane or boulevard in a pleasant-looking neighborhood setting. Conditions that felt uncomfortable to the women included things like congested roadways with fast-moving traffic, places without bicycle infrastructure, and experiences with aggressive drivers. Several moms shared they had experienced aggression from drivers on multiple occasions (even with children on-board) and made a distinction that this experience was much different than the experience of their male partners. These factors are illustrated in .

Discussion

How do cargo bikes impact the travel habits of women? Our quantitative assessment illustrates that women do use cargo bike for travel, particularly with children. Further, it may be that the comfort these platforms provide have more benefit to them in terms of boosting cycling confidence than their male partners. Factors contributing to use of cargo bikes, reinforced repeatedly during interview conversations, included: roadway conditions; the incorporation of children on trips; cost of distance and destinations; and level of confidence on a bicycle. For example, the women interviewed underscored the imports of making trip-chaining, or linked trips with various purposes around town (particularly with children) – something that the bike empowered them to do. They felt they there were different that the men in their lives because as women they carried gear and kids, and needed tools to do this. As Amy brought up,

‘Women … need a trunk. My bike is my trunk.’

This statement suggests a larger role for cargo bikes, and perhaps a role for electric assist motors, especially to address considerable energy for stopping and starting as noted in . This would also help overcome some of the challeges from the women interviewed who felt strongly deterred by an uncomfortable built environment. This includes the presence of fast-moving or congested traffic as well as ensuring the safety of their children and themselves while riding a cargo bike. Interviewees also raised weather as a concern for cargo bike use, bringing up the conversation of location-specific characteristics that support ridership.

As mentioned previously, while our survey had respondents from around the US, the City of San Luis Obispo is a bicycle-friendly community with above average bicycle infrastructure, mild winters and minimal rainfall. It is also in this region where even those with acute bicycle knowledge that influences their degree of comfort still have challenges with their level of experience in inclement weather. Recognizing the influence of this experience, several women brought up the importance of bicycle education and biking with confidence. Emma mentioned:

“I would like to find ways to encourage more moms get out there and bike more, whether with kids or not. I have friends (other moms) who say that they would like to bike with their kids, but they feel nervous about it, and I think it’s because they didn’t grow up biking and they don’t have that comfort level for biking in a city.”

In addition to roadway improvements, gaining a level of comfort as a female bike rider on a shared roadway with automobiles was also a theme of interviews. Bicycle education was discussed by all of the women who participated. Bicycle education may take place in the form of classes at a local bike coalition or from current cargo bike women who can make their cargo bike available for a ‘test ride’ to other interested women/families. Both educational would help build up confidence as a rider, with and without children on-board.

In the end, while a small sample that may be biased toward individuals who are predisposed to cycling, our data and cases provide illustrative narratives in that Small, Flyvberg and others, exploring the relationship between women and cargo bikes. We find that not only do they have potential to reframe travel but that there is much more to learn about how can encourage cycling for women and those with children, and policy might help educate and improve the perception of safety for these individuals.

Conclusions

The research study highlights a substantial difference in travel behavior between men and women and utilizes the cargo bike as the means for investigating thresholds of transportation comfort, function, and enjoyment. As assessment of a national survey along with discussions with women about their experience suggest that the cargo bike is a practical substitute for a vehicle. Results show that 78% percent of women used cargo bikes for trips with kids, vs. 56% of men. Qualitative work expands this and suggest that cargo bike use is likely tempered by access to a cargo platform, geography, cultured and rider experience. Based on these results this may be limited to unique circumstances, a certain level of comfort and extant bicycle culture. Circumstances likely include living in a city with supportive bicycle infrastructure; having pre-existing experience or knowledge of how to ride safely in traffic; possessing the financial ability to invest in a cargo bike; and time availability to transport children and make errands on a slower mode of transit. Unless these are achieved, a woman may be less inclined to use a cargo bike.

These findings also show that the dependency on the cargo bike may be restricted by changes to family needs, so the number of automobiles owned may be dependent on these changes, as well as additional factors (e.g. economic allowance or proximity to necessary resources). And while our study is focused on a limited geography predisposed to cycling and sample individuals who have already self-selected a cargo bike, consistent with Flyvbjerg (Citation2006) it does allow us to explore things we can learn from our case as opposed to developing generalizable theory. In light of this, two considerations for continued research include:

Access to a cargo bike may factor in to modal decisions, yet as the introductory literature alludes most literature on these platforms focuses on Western Europe – an environment with cultural and infrastructure differences from the U.S. and one that is worthy of more investigation;

Cargo bikes may provide empowerment but as interviews revealed limitations in infrastructure and education remain and more work is needed understand how this can be tailored to the needs of women.

First, the cargo bike is experienced differently in the United States as it is in Europe. Reasons for these differences include a difference in the cultural acceptance of bicycle transportation and the city infrastructure that accommodates this mode type to be accessible and used as a functional mode of transportation. European streetscapes that use embrace mixed flow or have less formal separation between modes may not be as easily in the United States or function in the same manner. Infrastructure should fit the needs and structure of cities and citizen groups, yet there is ample opportunity to accommodate the cargo bike platform into roadway design and developments in the U. S., let alone in any city or country around the globe. This could be interventions as simple as providing larger and more secure parking options or introducing wider bikeways to accommodate a longer, heavier, and wider bike model – changes that might also increase safety for the broader cycling community.

The second lesson brings up gender equity in bicycling. This research serves as documentation that shows that women have different experiences with the cargo bike in comparison to men. Key factors that contribute to these differences include familial responsibilities and commitment to household needs. These factors present women with a skewed opportunity to select a mode alternative to the automobile due to carrying capacity needs. However, the data shows that the cargo bike can help meet the need for some of those trips – it can be a tool for mode substitution and an option for women to break away time spent in a vehicle. It could also be the case that there is a role for e-bikes to play a role in reducing barriers, particularly given the recent studies on dockless e-bikes and e-scooter systems that show motors are a significant factor at reducing gender barriers for these new disruptive modes of travel (Populus, Citation2018). Yet even with this promise gaps still remain, only highlighting barriers in infrastructure and education that serve as continued barriers to entry for women. Given this, it may be safe to assume, that the full impact of cargo bikes as a mode substitution tool may still be ahead of us. To realize the fully we may need to overcome limitations of place and perception that have continued to limit female ridership.

Authors contribution

Riggs: Literature Search; Statistical Analysis; Manuscript Review, Writing & Editing

Schwartz: Literature Search; Interviews; Manuscript Writing

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Notes

1. See Riggs (Citation2016) for more information on cargo bike cost and mode substitution behavior, as well as the Red Tricycle blog (2018) which offers a cost comparison of front vs. rear loading bikes (http://redtri.com/biking-with-kids-family-cargo-bikes/). Since the original survey in 2015, cargo bike costs have come down and new technology (such as e-assist) have been introduced to the market. That said, although our sample represented users of many bike platforms, at the point when the original survey and interviews were conducted, Yuba’s rear-loading platform was the most cost-effective unit on the market.

2. The survey was issued to the owner on file, with a screening question that they were the primary user and recent purchaser of cargo bike, and that they consented to the survey. The individual then responded to questions about daily travel patterns before and after purchase. While some bike use may have happened by other individuals in a household, since our focus was on individual-level behavior and filtered by predominant user, we believe our data accurately represents individual-level behavioral patterns.

References

- Akar, G., Flynn, C., & Namgung, M. (2012). Travel choices and links to transportation demand management: Case study at Ohio State University. Transportation Research Record: Journal of the Transportation Research Board, (2319), 77–85.

- Baker, L. (2009). How to get more bicyclists on the road. Scientific American, 301, 28–29.

- Bonham, J., & Wilson, A. (2012). Bicycling and the life course: The start-stop-start experiences of women cycling. International Journal of Sustainable Transportation, 6(4), 195–213.

- Börjesson Rivera, M., & Henriksson, G. (2014, June 18–20). Cargo Bike Pool: A way to facilitate a car-free life? 20th International Sustainable Development Research Conference, Trondheim (pp. 273–280). Retrieved from http://www.diva-portal.org/smash/record.jsf?pid=diva2:845352

- Cervero, R., & Duncan, M. (2003). Walking, bicycling, and urban landscapes: Evidence from the San Francisco Bay Area. American Journal of Public Health, 93(9), 1478.

- Chatman, D. (2009). Residential choice, the built environment, and nonwork travel: Evidence using new data and methods. Environment and Planning A, 41(5), 1072–1089.

- Choubassi, C. (2015). An assessment of cargo cycles in varying urban contexts (PhD Thesis). University of Texas. Retrieved from https://repositories.lib.utexas.edu/bitstream/handle/2152/31772/CHOUBASSI-THESIS-2015.pdf

- Clark, B., Chatterjee, K., & Melia, S. (2015). Changes to commute mode: the role of life events, spatial context and environmental attitude. Transportation Research Board 94th Annual Meeting. Retrieved from http://trid.trb.org/view.aspx?id=1339187

- Crouch, M., & McKenzie., H. (2006). The logic of small samples in interview-based qualitative research. Social Science Information, 45(4), 483–499.

- Eagly, A. H., & Steffen, V. J. (2000). Gender stereotypes stem from the distribution of women and men into social roles. Retrieved from http://psycnet.apa.org/psycinfo/2000-16592-007

- Edgar, E., & Billingsley, F. (1974). Believability When N = 1. The Psychological Record, 24(2), 147–160.

- Emond, C., Tang, W., & Handy, S. (2009). Explaining gender difference in bicycling behavior. Transportation Research Record: Journal of the Transportation Research Board, (2125), 16–25.

- Fagan, C., & Trudeau, D. (2014). Empowerment by design? women’s use of new urbanist neighborhoods in suburbia. Journal of Planning Education and Research, 34(3), 325–338.

- Flyvbjerg, B. (2001). Making social science matter: Why social inquiry fails and how it can succeed again. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Flyvbjerg, B. (2006). Five misunderstandings about case-study research. Qualitative Inquiry, 12(2), 219–245.

- Garrard, J., Handy, S., & Dill, J. (2012). Women and cycling. City Cycling, 211–234.

- Handy, S. L., Boarnet, M. G., Ewing, R., & Killingsworth, R. E. (2002). How the built environment affects physical activity. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 23(2S), 64–73.

- Heesch, K. C., Sahlqvist, S., & Garrard, J. (2012). Gender differences in recreational and transport cycling: A cross-sectional mixed-methods comparison of cycling patterns, motivators, and constraints. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity, 9(1), 1.

- Johansson, M. V., Heldt, T., & Johansson, P. (2006). The effects of attitudes and personality traits on mode choice. Transportation Research Part A: Policy and Practice, 40(6), 507–525.

- Law, R. (1999). Beyond “women and transport”: Towards new geographies of gender and daily mobility. Progress in Human Geography, 23(4), 567–588.

- Masterson, A. (2017). Sustainable urban transportation: Examining cargo bike use in seattle.

- Populus. (2018). The micromobility revolution. Retrieved from https://www.populus.ai/micro-mobility-2018-july/

- Pucher, J. R., & Buehler, R. (2012). City Cycling. Cambridge: MIT Press.

- Riggs, W. (2015). A46 cargo bikes as a growth area for active transportation. Journal of Transport and Health, 2(2), S28–S29.

- Riggs, W. (2016). Cargo bikes as a growth area for bicycle vs. auto trips: Exploring the potential for mode substitution behavior. Transportation Research Part F: Traffic Psychology and Behaviour, 43, 48–55.

- Riggs, W., Rugh, M., Cheung, K., & Schwartz, J. (2016). Bicycling and gender: Targeting guides to women. Women in Sport and Physical Activity Journal, 24(2), 120–130.

- Riggs, W., & Schwartz, J. (2015). The impact of cargo bikes on travel patterns: survey report. City & regional planning studios and projects. Retrieved from http://digitalcommons.calpoly.edu/crp_wpp/15

- Schliwa, G., Armitage, R., Aziz, S., Evans, J., & Rhoades, J. (2015). Sustainable city logistics—Making cargo cycles viable for urban freight transport. Research in Transportation Business and Management, 15, 50–57.

- Schwanen, T., & Mokhtarian, P. L. (2005). What affects commute mode choice: Neighborhood physical structure or preferences toward neighborhoods? Journal of Transport Geography, 13(1), 83–99.

- Small, M. L. (2009). How many cases do I need?’: On science and the logic of case selection in field-based research. Ethnography, 10(1), 5.