ABSTRACT

The article examines the impact of the study for Levittown of urban sociologist Herbert Gans on Denise Scott Brown’s thought. It scrutinizes Denise Scott Brown, Robert Venturi, and Steven Izenour’s ‘Remedial Housing for Architects or Learning from Levittown’ conducted in collaboration with their students at Yale University in 1970. Taking as its starting point Scott Brown’s endeavour to redefine functionalism in ‘Architecture as Patterns and Systems: Learning from Planning’, and ‘The Redefinition of Functionalism’, which were included in Architecture as Signs and Systems: For a Mannerist Time (2004), the article sheds light on the fact that the intention to shape a new way of conceiving functionalism was already present in Learning from Las Vegas, where Robert Venturi, Denise Scott Brown and Steven Izenour suggested an understanding of Las Vegas as pattern of activities. Particular emphasis is placed on Scott Brown’s understanding of ‘active socioplastics’, and on the impact of advocacy planning and urban sociology on her approach. At the core of the reflections developed in this article is the concept of ‘urban village’ that Gans uses in US in The Urban Villagers: Group and Class in the Life of Italian-Americans (1972) to shed light on the socio-anthropological aspects of inhabiting urban fabric.

KEYWORDS:

- Active socioplastics

- socioplastic praxis

- advocacy planning

- urban sociology

- Denise Scott Brown

- Herbert Gans

- urban village

- socio-anthropological perspective

- Paul Davidoff

- Ludovico Quaroni

- West End in Boston

- Levittown

- as found

- sensibility of place

- Alison and Peter Smithson

- Robert Venturi

- New Brutalism

- University of Pennsylvania

- social planners

- CIAM Summer School

- new objectivity

- city planning

- non-judgemental perspective

- Urban Re-identification Grid

- Louis Kahn

- architectural pedagogy

- urban planning pedagogy

- functionalism

- Steven Izenour

1. Introduction

In 1952, Denise Scott Brown resettled in London to work as an architect, but, eventually, enrolled at the Architectural Association (AA) (Lee Citation2017). In 1954, two years after her arrival at the AA, the Department of Tropical Architecture was formed. This department was renamed Department of Tropical Studies in 1961. It was led by Otto Koenigsberger and its core concern was the research on climatically responsive, energy conscious ‘Green Architecture’.Footnote1 Scott Brown graduated from the AA Diploma and Certificate in Tropical Architecture in 1956 (Troiani Citation2005, 133). Before studying in London, she studied at Witwatersrand University in South Africa, starting in 1949. During her stay in London, she was particularly interested in the ‘urbanistic ideas of the New Brutalists’ (Scott Brown Citation2016; Citation1990b). Reyner Banham, in his seminal article entitled ‘The New Brutalism’, paid special attention to the exhibition ‘Parallel of Life and Art’ held at the Institute for Contemporary Art (ICA) in London in 1953 and curated by Alison and Peter Smithson, Nigel Henderson and Eduardo Paolozzi. Banham described New Brutalist aesthetics ‘as being anti-art, or at any rate anti-beauty in the classical aesthetic sense of the word’ (Banham Citation1955, 359; Charitonidou Citation2021b). Alison and Peter Smithson instrumentalised the concept of ‘New Brutalism’ to redefine the conventional understanding of function characterising the modernist era (Charitonidou Citation2022d). In 1955, three years after their entry for the competition for the Golden Lane project, Alison Smithson defined as follows ‘New Brutalism’:

The New Brutalism is the extension of the original functionalism (Constructivism and the Esprit Nouveau) in that it is the poetry of the natural order – a seizing on the essence of the programme, an attitude which is fundamentally anti-academic even in a period when anti-academic has become academic.Footnote2

Scott Brown has described New Brutalism as ‘a movement of the 1950s and 1960s that related architecture to social realism’ (Scott Brown Citation2004a, 109). Scott Brown has mentioned regarding the British context when she relocated in London in 1952: ‘I landed in post-World War II England amidst the look-back-in-anger generation, in a society in upheaval, where social activism was part of education’ (Scott Brown Citation2004a, 109).

Scott Brown has remarked that one of the main characteristics of the New Brutalists’ ideology was the intention to shed light on what happened ‘in the streets of poor city neighborhoods’. According to her, sociologists such as Michael Young and Peter Willmott (Young & Willmott Citation1957), who invited ‘planners to understand how people lived in the East End of London, saying that those who had been bombed out of housing could not simply be moved to the suburban environment of the new towns’, helped architects realize how important was the endeavour of understanding the reasons for which ‘life on the streets was [for low-income citizens] a support system’ (Scott Brown in Fontenot Citation2021, 202). Scott Brown has also highlighted that ‘[b]efore Jane Jacobs, Young and Willmott voiced complaints against the social disruption induced by urban planning’ (Scott Brown in Fontenot Citation2021, 202).

Scott Brown stayed in London for six years, before resettling in Philadelphia in the United States to study planning at the Department of City Planning at the Graduate School of Fine Arts of the University of Pennsylvania. An aspect that is of great importance for understanding the reasons behind her decision to study there is the impact that Alison and Peter Smithson had on her thought. Peter Smithson encouraged her to go to the University of Pennsylvania to study planning. Characteristically, Scott Brown has remarked: ‘Peter Smithson recommended that we apply to the University of Pennsylvania because the architect Louis I. Kahn taught there’ (Scott Brown Citation2016; Citation2021). The fact that Alison and Peter Smithson had met Louis Kahn in the framework of Team 10 meetings could explain this. Alison and Peter Smithson were influenced by Kahn’s approach as it becomes evident in an essay they devoted to his work in 1960 (Smithson & Smithson Citation1960).

When Scott Brown arrived at the University of Pennsylvania, the Department of City Planning was significantly influenced by the methods of social sciences. The projects that were conducted in the framework of the Institute for Urban Studies of the Graduate School of Fine Arts had not many connections with the dominant models during the same period at the Department of Architecture. An important figure at the time within the context of Philadelphia, but also beyond it, was Louis Kahn. Kahn had started teaching at Yale University in 1947. In 1955, he was appointed Professor at the University of Pennsylvania, and in 1966, he became Cret Professor of Architecture modern ideas. When Denise Scott Brown arrived at University of Pennsylvania as a student in 1958, Kahn was teaching there. As Stanislaus von Moos has remarked, ‘Venturi had worked at Kahn’s office for nine months in 1956–57’ (Von Moos Citation1999, 15).

Denise Scott Brown, while studying at the University of Pennsylvania, took numerous social sciences courses. Among them, the courses of Herbert Gans played an important role for her trajectory. During the same period, she collaborated with a number of social planners, and was involved in social planning in Philadelphia. Her collaboration with the circles of social planners should be taken into account when one tries to understand how the exchanges between architects, urban planners and sociologists determined the formation of her pedagogical and design approach (Scott Brown Citation1976). Insightful is her remark that architects, instead of trying to adopt the perspective of sociologists, should try ‘to look at the information of sociology from an architectural viewpoint’ (Scott Brown in Cook and Klotz Citation1973, 252). An aspect that explains the novelty of Scott Brown’s viewpointFootnote3 is the fact that her approach aims to bring together her interest in the non-judgmental viewpoint of the ‘new objectivity’ of Gans’s understanding of urban sociology and her passion for pop art aesthetics. Regarding this issue, she has highlighted: ‘I like the fact that the influences upon us are the pop artist on one side and the sociologist on the other’ (Scott Brown in Cook and Klotz Citation1973, 252; Scott Brown Citation2003). Enlightening regarding how the sociological perspective meets the pop artist viewpoint are Scott Brown’s following words:

The forms of the pop landscape […] speak to our condition not only aesthetically but on many levels of necessity, from the social necessity to rehouse the poor without destroying them to the architectural necessity to produce buildings and environments that others will need and like. (Scott Brown Citation1971, 28)

2. Denise Scott Brown at the 1956 CIAM Summer School and the significance of planning

Among the aspects that could help us better understand her interest in planning and the reasons for which she decided to resettle in Philadelphia in order to study planning at the University of Pennsylvania are her participation to the CIAM Summer School in Venice, as well as the impact of Italian architect Giuseppe Vaccaro on her thought (Scott Brown Citation1996). In 1956, Denise and her first husband Robert Scott Brown, who died in 1959 in a car accident, participated to the CIAM (Congrès Internationaux d’Architecture Moderne) Summer School in Venice (Charitonidou Citation2018). During the same period, Robert Venturi, who would become the second husband of Scott Brown, spent two years – from 1955 to 1956 – as visiting scholar at the American Academy of Rome. During his stays in Italy, Venturi developed a friendship with Ernesto N. Rogers and, as Matino Stierli notes, was confronted with the question building in historically sensitive urban areas, which was a major issue in the post-war Italian architectural scene (Stierli Citation2007). Denise and Robert Scott Brown assisted Vaccaro for his project “for Ina-Casa’s Ponte Mammal neighbourhood on the northeast side of Rome (Pilat Citation2016). Characteristically, she remarks, in ‘Towards an ‘Active Socioplastics’:

Summer School in Venice and some weeks in the architecture office of Giuseppe Vaccaro in Rome reinforced our intention, first formulated at the AA, to continue our training in architecture via the study of city planning. (Scott Brown Citation2009, 27)

During the 1956 CIAM Summer School, Ludovico Quaroni delivered a keynote lecture entitled ‘The architect and town planning’ on 14 September 1956 (Scimeni Citation1956). At the core of this lecture was the interrogation regarding the ways in which architects could have social responsibilities. Quaroni argued that key for enhancing architects’ impact on society is the dissolution of the boundaries between town planning and architecture. He tried to explain ‘why […] town planning [should] be the architects’ concern’, drawing a distinction between an understanding of function as object and an understanding of function as principle. He highlighted: ‘the latest development of the battle for modern art caused architecture to formulate as an object what is just a principle, namely that the form must rise from the functionalism’ (Van Bergeijk Citation2010).

Quaroni’s critique of functionalism could be interpreted as a critique of Le Corbusier’s categorisation of human actions into ‘dwelling, working, [and] cultivating mind and body’, and of Le Corbusier’s understanding of the user as ‘machine-man’ and the house as ‘machine à habiter’. Quaroni suggested a reinvention of the concept of function, challenging Le Corbusier’s quantitative and simplistic understanding of function, and blaming him for neglecting the physical, special, psychological, and moral factors related to function. He asserted, during the aforementioned lecture: ‘not having fully digested the idea of function, in the long run, we identified it only with a question of form’. Quaroni also argued that ‘function cannot be determined by means of mere square or cubic meters, since it is a compound of physical, special, psychological, moral factors’, and underscored the importance of understanding ‘architecture as a social function’ (Van Bergeijk Citation2010).

Quaroni identified Le Corbusier and Frank Lloyd Wright as ‘the last specimen of that generation of architects, the founder of which was perhaps Brunelleschi’, who without ‘having fully digested the idea of function […] identified it only with a question of form’ (Van Bergeijk Citation2010). He also underlined the importance of the architects’ role in revealing the connections between the individual and the collective in society. According to Quaroni, a characteristic of contemporary city was the absence of a homogeneous structure. Quaroni used the concept of ‘marvellous city’ to refer to this absence of homogeneity in urban structures. The notion of ‘urban architecture’, which was dominant in the debates concerning architectural and urban epistemology and educational strategies in several schools of architecture in Italy during the 1960s, was at the core of Quaroni’s thought. What I argue here is that Scott Brown was influenced by this keynote lecture of Quaroni, particularly as far as the critique of modernist functionalism and the dissolution of the distinction between architecture and town planning are concerned.

Ludovico Quaroni’s aforementioned keynote lecture and his critique of Le Corbusier and the functionalism of modernist architecture and urbanism constituted an early encounter of Scott Brown with an analysis of the risks that a rigid understanding of the concept of function in architecture and urban planning entails, on the one hand, and the drawbacks of separating the practice of architecture and the practice of urban planning, on the other hand. Quaroni, eleven years later, in La torre di Babele, ‘Quaroni argues that “the modern city is really ugly” and that the neglected lesson of historic cities is the well-integrated synthesis of function, technology and aesthetics’ (Charitonidou Citation2022a; Citation2022b; Citation2020, 231; Quaroni Citation1967). Despite the commonalities between some aspects of Quaroni’s critical view of modernist functionalism and Scott Brown’s deferred judgment, Quaroni’s analysis of ‘the tension between the historic and the modern city’, and his choice to relate ‘the historic city’s beauty to its “clear design … and structure” [and the ugliness of] […] the modern city [to the fact that it is] […] “chaotic”’ (Charitonidou Citation2022a; Citation2022b; Citation2020d, 231; Quaroni Citation1967; Chowkwanyun Citation2014) differs a lot from Scott Brown’s posture, who seems to desire to understand the logic behind the complexity and patterns characterising the post-war urban and suburban fabric.

3. Advocacy planning movement and the critiques of urban renewal

To grasp the specificity of the context of Philadelphia during the late 1950s, we should bear in mind the urban renewal efforts and the critiques of the advocacy planning movement. Scott Brown has commented on advocacy planners’ critique of urban renewal program, highlighting that it ‘derived from the problem that urban renewal had become “human removal”’ (Scott Brown Citation2009, 32; Charitonidou Citation2021c; Lung-Amam et al., Citation2015). She has also underscored that the main argument of advocacy planners was that architects and urban planners’ ‘leadership had diverted urban renewal from a community support to a socially coercive boondoggle’ (Scott Brown Citation2009, 33; Pacchi Citation2018). In parallel, during this period, several universities in the United States launched programs in city planning or urban design. Among them is Harvard University that initiated its program on urban design two years before Scott Brown’s arrival in the United States.

The pedagogical approaches at the Department of City Planning at the University of Pennsylvania when Scott Brown resettled there was influenced by social sciences and New Left critiques. The activities and publications of Jane Jacobs are also of great significance for understanding the social aspects of the ideas of Scott Brown during those years. Among the texts of Jacobs that had an important impact on Scott Brown’s thought is Jane Jacobs’s articles entitled ‘The City’s Threat to Open Land’, ‘Redevelopment Today’, and ‘What is a City?’ published in Architectural Forum in 1958, that is to say the same year in which Scott Brown resettled in Philadelphia (Jacobs Citation1958a; Citation1958b; Citation1958c; Klemek, Citation2014; Citation2009). Scott Brown remarked concerning the context in Philadelphia in the 1950s and its relationship to what would later be called New Left:

Here, long before it was visible in other places, was the elation that comes with the discovery and definition of a problem: poverty. The continued existence of poor people in America was a real discovery for students and faculty in the late 1950s. The social planning movement engulfed Penn’s planning department. (Scott Brown Citation1984a; Klemek Citation2011, 184)

In the early 1960s, one of the most important advocacy planners, Paul Davidoff, also taught at the City Planning Department of the University of Pennsylvania between 1958 and 1965. Davidoff was among the protagonists of Advocacy Planning movement in the United States. In his seminal article entitled ‘Advocacy and Pluralism in Planning’ published in 1965, remarked that ‘[p]lanners should be able to engage in the political process as advocates of the interests both of government and of such other groups, organizations, or individuals who are concerned with proposing policies for the future development of the community” (Davidoff Citation1965, 332).

David A. Crane, who was Scott Brown’s student advisor at the University of Pennsylvania, also had an important impact on her, especially as far as the strategies employed in studio teaching are concerned (Scott Brown Citation2016; Crane Citation1960a; Citation1960b). As Clément Orillard reminds us, Crane collaborated with Kevin Lynch for the preparation of the maps and diagrams included in The Image of the City (Lynch Citation1964; Orillard, Citation2009, 297). During the period Crane mentored Scott Brown, he worked on a conference focusing on urban design criticism.Footnote4 In. 1959, Scott Brown started working as Crane’s teaching assistant (Orillard Citation2009, 297).

During the period that Scott Brown studied at the Department of City Planning of the University of Pennsylvania there was a tension between the pedagogical methods of social planners and studio-based teaching strategies. This tension is described by ScottBrown as ‘the physical/non-physical debate’ (Scott Brown Citation2015, 80; Scott Brown Citation1965). Gans used the expression ‘fallacy of physical determinism’ (Gans Citation1968; Citation2002) to refer to the tendency of urban planners to believe that ‘place shapes people’s behavior’ (Arefi and Triantafillou Citation2005, 76).

4. The impact of Herbert Gans’s socio-anthropological perspective on Denise Scott Brown’s approach

The University of Pennsylvania was one of the universities that hired sociologists to teach at their planning departments. An important figure that taught there when Scott Brown arrived was urban sociologist Herbert Gans, who is mentioned in Paul Davidoff’s seminal article ‘Advocacy and Pluralism in Planning’ (Davidoff Citation1965). Between 1953 and 1971, Gans was affiliated with the Institute of Urban Studies of the University of Pennsylvania, the Center for Urban Education, and the MIT-Harvard Joint Center for Urban Studies(Rao Citation2012). Along with Davidoff, he played an important role in the emergence of the advocacy planning movement in the United States. Scott Brown was particularly interested in Gans’s ‘new objectivity’, which aimed to relate ‘social life, popular culture and planning’ (Scott Brown Citation2009; Citation2003, 29).

Scott Brown’s interest in the concept of ‘objectivity’ goes back to her years at the AA, as it becomes evident in her following words: ‘The belief that architecture could save the world through objectivity and a brave use of technology was shared by many young architects at the AA’ (Scott Brown Citation2009, 27). During her studies at the AA, Scott Brown had as student advisor German Jewish architect and urban planner Arthur Korn, who was then member of the MARS (Modern Architectural Research) group, which was active between 1933 and 1957 (Mumford Citation2002, 168). Scott Brown has associated her interest in the concept of ‘active socioplastics’ with the impact that Korn’s ideas had on her. Regarding Arthur Korn’s impact on Scott Brown’s approach, one should bring to mind Korn’s book entitled History Builds the Town, in which special attention is paid to the fact that ‘[t]here has been in history an infinite variety of towns differing in function, structure and components’ (Korn Citation1953; Kurgan Citation2020). At the core of Korn’s analysis is the idea that the different forms of towns encountered in different societies are related to the economic and political structures of these societies.

While studying at the University of Pennsylvania, Scott Brown followed the courses of Gans, who was the first awardee of a PhD Degree from the Department of City Planning (Birch Citation2011, 24; Scott Brown and Venturi Citation2004). Gans, before joining the Department of City Planning at the University of Pennsylvania, was at the University of Chicago. Important for Gans’s approach was the work of Martin Meyerson and John Dyckmen (Klemek Citation2011, 56). Among Gans’s books that influenced Scott Brown’s approach is US in The Urban Villagers: Group and Class in the Life of Italian-Americans (Gans Citation1962), in which the author examined the everyday life of the inhabitants in Boston’s West End, a slum cleared area. The aforementioned book constituted a critique of the urban renewal strategies in the West End in Boston. It was based on an eight-months in situ research conducted during a period preceding the demolition of this area. More specifically, Gans remarked regarding his study of Italian Americans in Boston’s West End: ‘The West End was not really a slum, and although many of its inhabitants did have problems, these did not stem from the neighborhood’ (Gans Citation1962). ()

Figure 1. Photograph of the West End by Herbert Gans, ca. 1957. Credits: Herbert Gans papers, 1944–2004, Columbia University Rare Book & Manuscript Library.

Gans placed particular emphasis on the special characteristics of the environment and the community in Boston’s West End, analysing the impact of urban renewal, gentrification and displacement on existing communities (Mueller and Dooling Citation2011). Characteristically, he remarks, in US in The Urban Villagers: Group and Class in the Life of Italian-Americans, that ‘[n]ot all city neighborhoods are urban villages’ (Gans Citation1962, 16). Reading Gans’s book, one realizes that he intended to shed light on the socio-anthropological meaning of the concept of ‘urban village’. More specifically, he defined ‘urban village’ as a ‘city low-rent neighborhood typically one in which European immigrants – and more recently Negro and Puerto Rican – try to adapt their nonurban institutions and culture to the urban milieu’ (Gans Citation1962, 4).

5. Learning from Levittown Studio: towards a socio-anthropological perspective

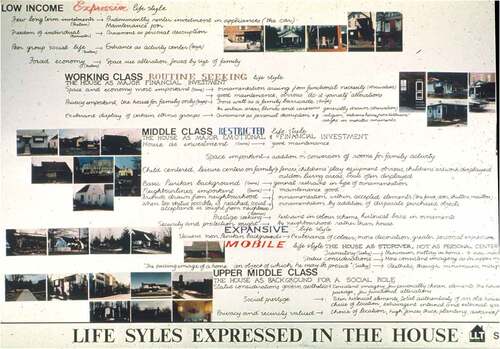

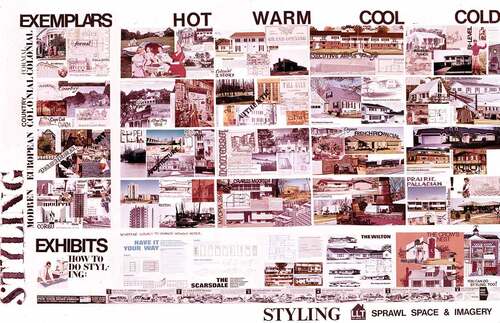

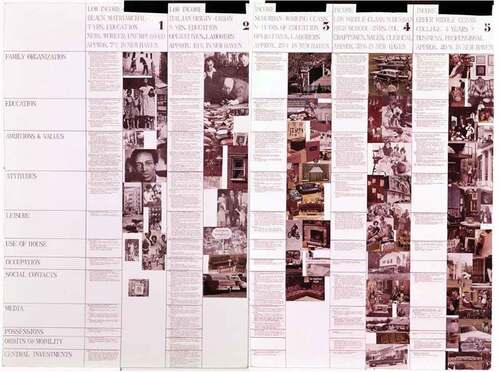

In the photographs that Scott Brown took in South Street West of Broad Street in Philadelphia, one can discern the impact of Gans’s approach on her perspective (). Another seminal book by Gans that influenced significantly Scott Brown’s approach is The Levittowners: Ways of Life and Politics in a New Suburban Community (Gans Citation1966; Citation1967). Three years after the publication of the latter, in 1970, Robert Venturi, Steven Izenour and Denise Scott Brown coordinated the study entitled ‘Remedial Housing for Architects or Learning from Levittown’, which was held in collaboration with their students at Yale University (). In the themes addressed in the framework of the course entitled ‘Learning from Levittown Studio’ that Robert Venturi, Denise Scott Brown, and Steven Izenour taught during the fall semester in 1970, we can easily discern the influence of Herbert Gans’s work. This influence was particularly present in the interest of Robert Venturi, Steven Izenour, Denise Scott Brown and their students in depicting the iconographical and symbolic values of suburbia, on the one hand, and in their choice to attach importance to the socio-anthropological dimension of the perception of architecture and the city. In the framework of the aforementioned course, special emphasis was placed on the analysis of the following aspects concerning the profile of the citizens of Levittown: their family organization, their education, their ambitions and values, their attitudes, their habits concerning leisure, their ways of inhabiting their houses, their habits concerning occupation, their social contacts, their media, their possessions, their orbits of mobility, and their central investments.

Figure 2. Photograph taken at South Street in Philadelphia by Denise Scott Brown. Credits: Venturi, Scott Brown Collection, The Architectural Archives, University of Pennsylvania.

Figure 3. Robert Venturi, Denise Scott Brown, and Steven Izenour, Learning from Levittown Studio, Fall 1970. Life Styles Expressed in the House. Credits: Venturi, Scott Brown Collection, The Architectural Archives, University of Pennsylvania.

Figure 4. Robert Venturi, Denise Scott Brown, Steven Izenour, Learning from Levittown Studio, Fall 1970. Styling. Sprawl, Space & Imagery. Scanned from photo reproduction. Credits: Venturi, Scott Brown Collection, The Architectural Archives, University of Pennsylvania.

Of great interest is the way in which Robert Venturi, Steven Izenour, Denise Scott Brown and their students in categorized the groups of citizens in the posters produced in the framework of the Learning from Levittown Studio. These groups were the following: (a) a first group concerning low income-black matriarchal families with 7 years of education, which were occupied mainly as workers and unemployed and corresponded to approximately 7% of the population of New Haven, (b) a second group concerning low income-Italian origin-urban families with 8 years of education, which were occupied mainly as operatives and laborers and corresponded to approximately 10% of New Haven (c) a third group concerning suburban-working class families with 8–11 years of education, which were occupied mainly as operatives and laborers and corresponded to approximately 10% of the population of New Haven, (d) a fourth group concerning suburban-low-middle class families with High School and 2 years College education, which were occupied mainly as craftsmen, salesmen and clerical and laborers and corresponded to approximately 35% of the population of New Haven, and (e) a fifth group concerning upper-middle class families with 4 years College education, which were occupied mainly in business and corresponded to approximately 20% of the population of New HavenFootnote5 ().

Figure 5. Robert Venturi, Denise Scott Brown, Steven Izenour, Learning from Levittown Studio, Fall 1970. House style by income category in New Haven, CT. Photos and markers on poster board. Credits: Venturi, Scott Brown Collection, The Architectural Archives, University of Pennsylvania.

Looking closely at the posters produced in the framework of the Learning from Levittown Studio, one distinguishes the emergence of new means of communication or new signs that reveal a shift concerning the social and aesthetic parameters of architectural and urban perception. Despite the fact that the emergence of these new media is more usually related in the existing scholarship on Denise Scott Brown and Robert Venturi to their study of Las Vegas and their seminal Learning from Las Vegas (Scott Brown et al. Citation1972), for which they also collaborated with Steven Izenour, one could argue that they were at the core of their visual analysis of Levittown as well. Many of the posters that were produced during the Learning from Levittown Studio were included in ‘Learning from Pop’, which was published in Casabellà in 1971 (Scott Brown Citation1971; Citation1984; Charitonidou Citation2021b; Citation2021d; Citation2021e). In this article, Scott Brown criticised Le Corbusier’s approach, juxtaposing it to the strategies of analysing the ways in which the inhabitants of Levittown shape their environment. According to her, architects should take into account ‘what people do to buildings’ (Scott Brown Citation1984b, 27; Citation1971).

Scott Brown’s concern about the cultural dimension of the quotidian life of the inhabitants of Levittown was also present in ‘Learning from Lutyens: Reply to Alison and Peter Smithson’, which was originally published in 1969 in the RIBA Journal (Scott Brown and Venturi Citation1969; Citation1984a). In this article, which constituted a reply to two articles published in the same journal by Alison Smithson and Peter Smithson respectively, (A. Smithson Citation1969; P. Smithson Citation1969), Scott Brown posed the following question, which echoes Gans’s socio-anthropological view:

Are architect still so condescending about the “dreams” of the occupants of Levittown, and cavalier about the complex social and economic, as well as symbolic, bases of residential sprawl? (Scott Brown & Venturi Citation1969; Citation1984a, 20).

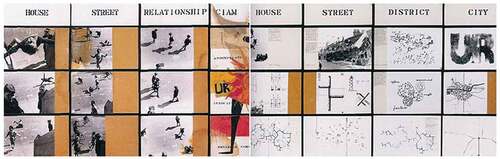

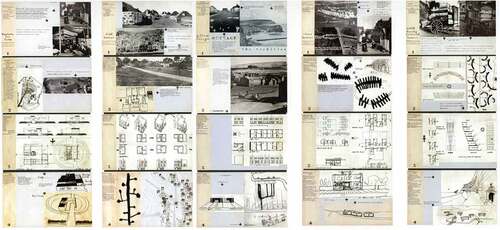

There is a thought-provoking graphic similarity between the poster produced in the framework of Learning from Levittown studio and Alison and Peter Smithson’s representation in the case of the ‘Urban Re-identification Grid’ shown at the 9th CIAM held in Aix-en-Provence in France in 1953 (; Charitonidou Citation2019), and the grille ‘Housing Appropriate to the Valley Section’ (; Charitonidou Citation2020a, 124), which was presented at the 10th CIAM held in Dubrovnik in Yugoslavia in 1956, that is to say the same year that the CIAM Summer School mentioned above took place in Venice.

Figure 6. Alison and Peter Smithson, Urban Re-identification Grid, presented at the 9th CIAM in Aix-en-Provence in 1953. Credits: Smithson Family Collection.

Figure 7. Alison and Peter Smithson, CIAM grille entitled ‘Housing Appropriate to The Valley Section’ presented at the 10th CIAM. Credits: Smithson Family Collection.

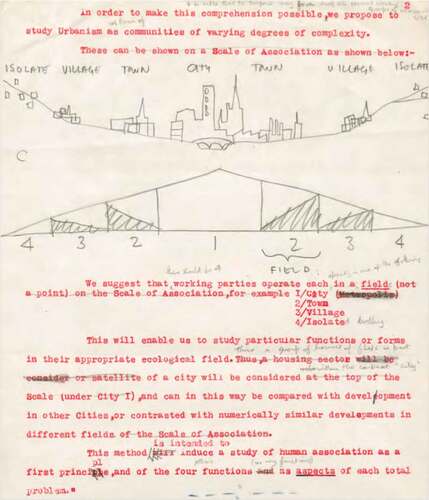

The ‘Urban Re-identification Grid’ constitutes a turning point regarding the conception of the inhabitants and the ‘humanization’ of functionalism during the post-war era .The critique of modernist functionalism, which is at the core of Scott Brown’s thought, was also at the heart of the debates of Team 10, which is also known as Team X or Team Ten and refers to the group of architects and urban planners, as well as other figures concerned about architecture and urbanism. At the centre of Team 10 was the intention to challenge certain rigid ideas of the CIAM. Team 10 emerged in July 1953 during the 9th CIAM. Its creation should be understood in relation to the intention ‘to “re-humanise” architecture’ (Charitonidou Citation2019, 73) and urbanism. The Doorn Manifesto or ‘Statement on Habitat’ is considered to be the founding document of Team 10. It was named after the city in which it was formulated and ‘signed in January 1954 by the architects Peter Smithson, John Voelcker, Jaap Bakema, Aldo van Eyck and Sandy van Ginkel and the social economist Hans Hovens-Greve’ (Charitonidou Citation2019). The main objectives of the Doorn Manifesto was ‘[t]he rediscovery of the “human” and the intensification of interest in proportions’, and the establishment of design strategies aiming to ‘to produce towns in which “vital human associations” [would be] […] expressed’’ (Charitonidou Citation2019, 73). It was in this manifesto that ‘Team 10 presented their “Scale of Association”, which was a kind of re-interpretation of Patrick Geddes’ Valley Section’ (; Charitonidou Citation2019, 73).

Figure 8. Valley Section Diagram as included in Doorn Manifesto for CIAM meeting in Doorn, January 1954. Credits: Het Nieuwe Instituut Collections and Archive, Rotterdam, CIAM Congresses and Team 10 Meetings.

The concern about reinventing the way architectural and urban artefacts are inhabited is reflected in the theme of the ninth CIAM held in 1953 in Aix- en-Provence in France, which was the ‘Grid of Living’. Through their ‘Urban Re-identification Grid’, Alison and Peter Smithson expressed their ideas concerning the transformation conception of the user in architecture during the post-war years, criticising the reductive of understanding urban reality during the modernist era (Charitonidou Citation2020d). Such a critique is also very present in Scott Brown’s work and, more particularly in the posters produced during the Learning from Levittown Studio in collaboration with Robert Venturi, Steven Izenour, and their students. The ‘Urban Re-identification Grid’ was organized around the concepts of ‘house’, ‘street’, ‘relationship’, ‘district’, and ‘city’, which were important for the visual argumentation of Learning from Levittown Studio as well. Among the visual components included in the ‘Urban Re-identification Grid’ were a photograph of Chisendale Road by Nigel Henderson (1951), who was along with Alison and Peter Smithson, Richard Hamilton, Eduardo Paolozzi, Lawrence Alloway, William Turnbull, John McHale, and Reyner Banham member of the Independent Group (Robbins Citation1990; Charitonidou Citation2021b; Citation2021d, Citation2021e), as well as a ‘diagram showing the network of housing and streets in the air and their collage for the competition for the Golden Lane Housing project (1952)’ (Charitonidou Citation2020c, 34).

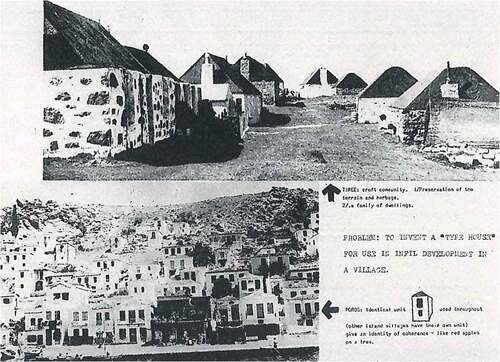

In the grille entitled ‘Housing Appropriate to the Valley Section’, Alison and Peter Smithson included a photograph taken in the Island of Poros in Greece accompanied by the following remark: ‘Poros: Identical unit used throughout (other Island villages have their own unit) give an identity of coherence – like red apples on a tree’ (; Charitonidou Citation2020a, 122). Three years, in 1959, during the last CIAM held in Otterlo in the Netherlands, Peter Smithson, in his presentation, paid special attention to the open-ended morphologies he encountered during his travels in Greek coastal villages, placing particular emphasis on ‘the relationship between the aggregation of Greek villages and the social and cultural patterns of quotidian life of their inhabitants’ (Charitonidou Citation2020a, 122). This concern about associating the social and cultural patterns of quotidian life of their inhabitants with the architectural and urban morphologies has certain affinities with the study of Robert Venturi, Denise Scott Brown, Steven Izenour, and their students in Levittown.

6. South street in Philadelphia and a careful regard for people and existing architecture

In ‘The Positive Functions of Poverty’, Herbert Gans, drawing upon Merton’s conception of function, analysed the ‘functions of poverty’ (Gans Citation1972, 276; Citation1974). He identified ‘functions for groups and aggregates’, including ‘interest groups, socioeconomic classes, and other population aggregates, for example, those with shared values or similar statuses’ (Gans Citation1972, 276). Scott Brown and Venturi remarked in a text describing their study for South Street in Philadelphia:

A rehabilitation of South Street, starting with what is there now rather than with utopian, non-refundable dreams and architectural monuments, with careful regard for people (residents and merchants) and existing architecture, would be a means for economic regeneration of the whole community, of much more than the street itself.Footnote6

In the aforementioned description of South Street in Philadelphia by Scott Brown and Venturi, one can discern their care about respecting the choices of inhabitants concerning the way space is experienced and transformed according to their cultural characteristics. To grasp the context of the South Street in Philadelphia in the late 1960s, one should bear in mind the activities of the so-called ‘Citizens’ Committee to Preserve and Develop the Crosstown Community’ (CCPDCC), which was established in 1968 by African-American housing activist Alice Lipscomb, community leader George Dukes, and lawyer Robert Sugarman, and advocated that the viable characteristics of the street should be preserved.

Robert Venturi and Denise Scott Brown were invited by the CCPDCC to show in a visual why an ensemble of features of the street were valuable and should not be neglected. At the core of the activities of the CCPCCC was the critique of the so-called ‘Crosstown Expressway’, which had been approved to be sponsored by the Federal government. According to Sebastian Haumann, ‘[t]he intention of the collaboration was to develop an alternative plan for the “Corridor” to fend off the City’s intrusive proposals effectively’ (Haumann Citation2009, 40). Scott Brown has noted, in Urban Concepts, regarding their study in South Street in Philadelphia: ‘One of the reasons they accepted us was that we had a concern in common. Bob Venturi, apart from being an architect, was a fruit merchant. He had inherited his father’s business on South Street’. (Scott Brown Citation1990c, 35)

7. The patterns of mapped data as signs of life

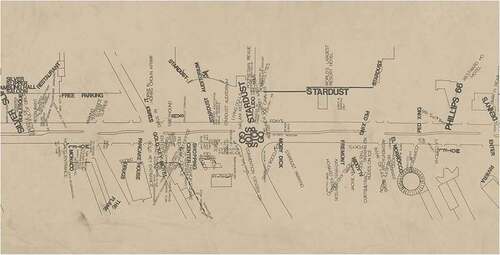

Denise Scott Brown first visited Las Vegas in 1965, during a trip to Los Angeles, where she was teaching at Berkeley for a short period. Scott Brown has remarked that their main objective in the case of their study on Las Vegas was to analyse ‘symbols in space’ (Scott Brown in Rattenburry & Hardigham Citation2007, 81). In order to conduct their analysis of ‘symbols in space’, they chose to examine ‘the shapes, sizes and locations and symbolic content of signs to learn how people in cars would react to [them]’ (Scott Brown in Rattenburry and Hardigham Citation2007, 81). They decided to focus on Las Vegas because they considered it representative of the new type of urban form related to the intensified use of the car. In other words, for them, Las Vegas was representative of ‘the emerging automobile city’. In this sense, Las Vegas was chosen because, in their opinion, it constituted an ‘archetype’ automobile city, to borrow Scott Brown’s own expression. Perceiving Las Vegas as an ‘archetype’ automobile city went hand in hand with believing that investigating closely how drivers react when confronted with ‘symbols in space’ would also help them better understand the automobile vision characterizing other cities that are closely connected to the car such as Los Angeles (). Regarding his issue, Scott Brown has underscored: ‘we examined the archetype, but our aim was to understand, from it, the automobile city – to understand the Los Angeles of that time’ (Scott Brown in Rattenburry and Hardigham Citation2007, 81; Charitonidou Citation2021a).

Figure 10. Robert Venturi, Denise Scott Brown, and Steven Izenour, Learning from Las Vegas. First edition, 1972. Credits: Venturi, Scott Brown Collection, The Architectural Archives, University of Pennsylvania.

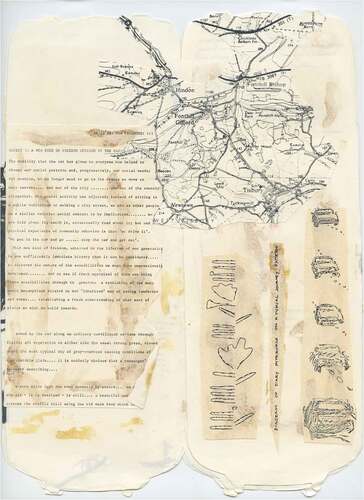

Scott Brown has remarked that ‘[i]n planning school, [she] […] learned to understand complex urban orders by mapping urban systems and studying their patterns’. She has always considered mapping as an important tool in architecture, and urbanism. More specifically, she seems to believe that ‘patterns of mapped data [can] help us to discover an order emerging from within – from what appears to be the chaos of the city – and to avoid imposing an artificial order from without’. She understands mapping as a mechanism serving to reveal ‘what “ought to be” from what “is”’ (Scott Brown Citation2016). Scott Brown taught the so-called ‘Form, Forces and Functions Studio’ at the University of Pennsylvania. This studio placed particular emphasis on the interactions between urban activity, settlement patterns, topography, and transportation, and on the of activity intensity patterns. It was centred on urban design, and on the economic and social forces charactering urban design (Scott Brown Citation1990a). This studio was a point of departure for developing a systematic planning approach.

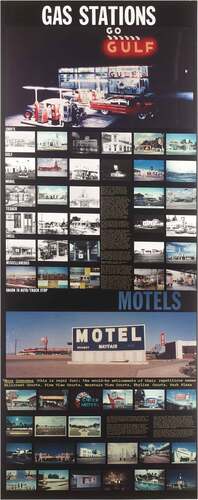

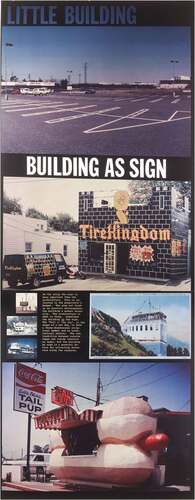

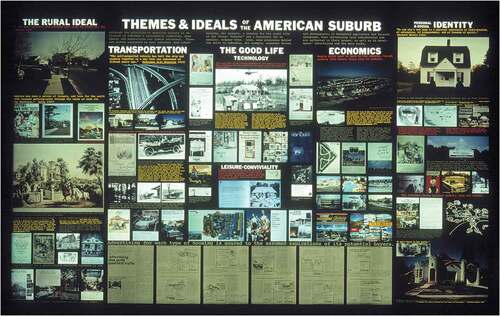

Another interesting case is the exhibit panel ‘Gas Stations’ concerning the theme ‘Signs of Life: Symbols in the American City’, which was among the outcomes of a study that Robert Venturi, Denise Scott Brown and John Rauch conducted between 1974 and 1976. This panel was displayed at Renwick Gallery in Washington D.C. from 26 February through 31 October 1976 (). In this exhibit panel, Venturi, Scott Brown and Rauch juxtaposed different typologies of Gas stations. The exhibition included the exhibit panels ‘Building as sign’ () and ‘Themes & ideals of the American Suburb’ as well (). In the latter, one can read:

Although the pluralism of American society is reflected in suburbia’s residential symbolism, some ideals and aspirations are almost universal. These are widely expressed in most suburban (and urban) housing, for example, a longing for the rural life or for things “natural” and a nostalgia for an earlier, simpler time. Also, some pressures behind the drive to suburbia, for example, economic forces and developments in household appliances and leisure equipment, bear universally upon suburbanites and are reflected in their houses, as well as in the developers’ advertising and the mass media.Footnote7

Figure 11. Robert Venturi, John Rauch, and Denise Scott Brown, architects and planners, signs of life: symbols in the American city Renwick Gallery, Washington D.C., 1974–1976. Exhibit panel ‘Gas Stations’. Credits: venturi, Scott Brown Collection, The architectural archives, University of Pennsylvania.

Figure 12. Robert Venturi, John Rauch, and Denise Scott Brown, Architects and Planners, Signs of Life: Symbols in the American City Renwick Gallery, Washington D.C., 1974–1976. Exhibit panel ‘Building as sign’. Credits: Venturi, Scott Brown Collection, The Architectural Archives, University of Pennsylvania.

Figure 13. Robert Venturi, John Rauch, and Denise Scott Brown, Architects and Planners, Signs of Life: Symbols in the American City Renwick Gallery, Washington D.C., 1974–1976. Exhibit panel ‘Themes & ideals of the American Suburb’. Credits: Venturi, Scott Brown Collection, The Architectural Archives, University of Pennsylvania.

8. Towards a conclusion: looking sociology from an architectural viewpoint

The intention to shape new ways of conceiving functionalism were present in Learning from Las Vegas, where Robert Venturi, Denise Scott Brown and Steven Izenour promoted an understanding of ‘Las Vegas as a Pattern of Activities’, arguing that a ‘city is a set of intertwined activities that form a pattern on the land’, as well as that ‘Las Vegas Strip is not a chaotic sprawl but as set of activities whose pattern […] depends on the technology of movement and communication and the economic value of land’ (Scott Brown et al. Citation1972, 76). Telling is the question that Scott Brown addresses, in ‘The Redefinition of Functionalism’: ‘How “functional” is it to plan for the first users […] and not give thought to how it may adapt to generations of users in the unforeseeable future?’ (Scott Brown Citation2004b).

Scott Brown’s fascination with Gans’s ‘new objectivity’ goes hand in hand with her interest in non-judgemental perspective. Regarding this, she has noted: ‘But we don’t say we don’t judge. We say we defer judgment. In deferring it, we let more data into the judgment, we make the judgment more sensitive’ (Scott Brown in Cook and Klotz Citation1973, 254). This process of deferring judgment is related to Robert Venturi, Denise Scott Brown and Steven Izenour’s strategies of combining social and aesthetic parameters while choosing to focus on certain aspects of Las Vegas Strip. Scott Brown’s following remark is enlightening concerning this: ‘Why do we accept certain aspects of the strip and not other aspects? The basis of that judgment is partly social, partly aesthetic’(Scott Brown in Cook and Klotz Citation1973, 254).

Denise Scott Brown’s way of interpreting architectural and urban forms was informed by both urban sociology and pop art. This explains why she believed that being in the middle can help you to learn from both. Her intention to reconcile these two perspectives – that informed by sociology and that informed by pop art – made her develop a critique not only vis-à-vis ‘the architects who say there’s nothing we can learn from the sociologist’, but also vis-à-vis ‘the sociologists [arguing] that […] architects [should] […] extend [their] […] conceptual framework’ (Scott Brown in Cook and Klotz Citation1973, 252; Horowitz Citation2012) in order to be able to grasp the specificities of urban sociology. Scott Brown has noted concerning the ways in which the tools and strategies of architects are useful for reshaping the perspective of the sociologists: ‘I say we will have to extend their framework as well, since they have neither the tools nor the outlook to take it into our field themselves’ (Scott Brown in Cook & Klotz Citation1973, 252).

To better grasp Scott Brown’s conception of ‘active socioplastics’, it would be useful to relate it to how Alison and Peter Smithson understood this concept given that she relates it to their design strategies (Boyer Citation2017; Stierli Citation2010). For the Smithsons, ‘active socioplastics’ referred to ‘the relationship between the built form and social practice’ (Avermaete Citation2008, 114). They drew upon Michael Young and Peter Willmott’s anthropological perspective when they coined the term (Moran Citation2012; Young and Willmott Citation1957). In 1953, Young founded the Institute of Community Studies in 1953. Scott Brown remarks, in ‘Towards an “Active Socioplastics”’ regarding Alison and Peter Smithson’s interpretation of ‘active socioplastics’:

They used the term socioplastics to suggest tying together the social and the physical, creating physical containers for the social at different scales. The term active referred to the life of people on the streets and discovering means of learning about it - achieving vitality and allowing for change (Scott Brown Citation2009; Citation2015)

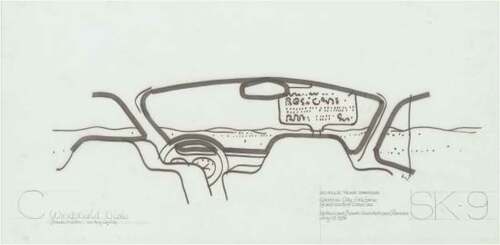

The concept of ‘active socioplastics’ could also be related to the concepts of ‘as found’ and ‘sensibility of place’ in Alison and Peter Smithson’s thought (Charitonidou Citation2021b; Citation2021d, Citation2021e). According to Claude Lichtenstein and Thomas Schregenberger, the concept of the ‘[a]s found [refers to] […] the tendency to engage with what is there, to recognize the existing, to follow its traces with interest’ (Lichtenstein and Schregenberger Citation2001, 8; Charitonidou Citation2021b, 15). An aspect of the ‘as found’ that could be related to Scott Brown’s view of urban reality its association with the ‘directness, immediacy, rawness, and material presence’, and its ‘concern with the here and now’ (Lichtenstein and Schregenberger Citation2001, 9, 15). We could relate ‘[t]he interest of the Smithsons in the new social patterns and social needs that emerge thanks to the intensified presence of the car in quotidian life […] to their understanding of the concept of sensibility’ of place (Charitonidou Citation2021b, 14). Alison Smithson related the ‘as found’ to ‘the new sensibility resulting from the moving view of landscape’ (Smithson Citation1983, 47; Citation2001). The shared interest of Alison and Peter Smithson and Robert Venturi and Denise Scott Brown in the view from the car and in how automobile vision affects how urban and suburban landscapes are perceived, and their concern about how automobile vision pushes architects and urban planners to invent new visual tools to represent the perception of urban, and their design ideas should be interpreted in relation to the attention they paid to ‘active socioplastics’, the ‘as found’, ‘sensibility of place’, and to the articulation between the social patterns of inhabitants and their material expression in the urban and suburban fabric ().

Figure 14. Mock-up of double page spread for AS in DS: An Eye on the Road (Smithson, Citation1983; Citation2001). Artwork by Alison Smithson, 1982. Credits: Smithson Family Collection.

Figure 15. Page from photo album, 1973–1976. Top left: Picnic at Scaceber, Autumn 1973. Middle panorama, Six Mile, January/February 1974. Bottom: trees. Photographs by Alison and Peter Smithson. Credits: Smithson Family Collection.

Figure 16. Robert Venturi, John Rauch and Denise Scott Brown, Architects and Planners. California City General Plan California City, California 1970–1971, not implemented. SK-9, 20 Mule Team Parkway, Windshield View Design sketch by Robert Venturi, 17 July 1970. Marker on paper. Credits: Venturi, Scott Brown Collection, The Architectural Archives, University of Pennsylvania Architectural Archives.

Figure 17. Detail from Robert Venturi, Denise Scott Brown, and Steven Izenour, Learning from Las Vegas Studio, Fall 1968. Word map, Las Vegas Strip, 1968. Credits: Venturi, Scott Brown Collection, The Architectural Archives, University of Pennsylvania.

Figure 18. Robert Venturi, Denise Scott Brown, and Steven Izenour Learning from Las Vegas Studio, Fall 1968. Word map, Las Vegas Strip 1968. Credits: Venturi, Scott Brown Collection, The Architectural Archives, University of Pennsylvania.

Denise Scott Brown, in ‘Towards an ‘Active Socioplastics’, uses the expression ‘socioplastic praxis’ to refer to the strategy of aligning ‘analysis and synthesis by mapping the patterns of relevant systems, [and] […] abstracting key variables and overlaying them to create further patterns’ (Scott Brown Citation2015, 91). Her belief that an attentive analysis of existing patterns can help us shape effective methods for creating, through architectural design and urban planning, patterns able to take into account the social and cultural aspects of communities has certain affinities with Herbert Gans’s perspective, which paid special attention to popular culture, everyday landscape, and existing social patterns. Gans’s teaching helped Scott Brown refine her understanding of functionalism in architecture and urban planning, and challenge the modernist conception of functionalism. Characteristically, Scott Brown has underscored: ‘Gans rocked our ideas of functionalism’ (Scott Brown Citation2009, 30). Among the main references of Gans concerning his critique of functionalism was the work of American sociologist Robert K. Merton (Merton Citation1949). At the core of Merton’s approach was the critique of the assumptions on which functionalism in anthropology was based (Loy and Booth Citation2004). Scott Brown’s intention to challenge the conventional understanding of modernist functionalism should be interpreted in relation to her endeavour to address architecture and urban planning adopting an inter-disciplinary perspective based on the exchanges between anthropology, urban sociology, architecture and planning.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank Smitshon Family collection for authorizing me to use . Moreover, I am grateful to the Architectural Archives of University of Pennsylvania for their authorisation to use . I am also thankful to Het Nieuwe Instituut for authorising me to use , and to Columbia University Rare Book & Manuscript Library for authorising me to use . The reflections developed in this article are related to the postdoctoral project “The Travelling Architect’s Eye: Photography and the Automobile Vision” that I conducted at the Department of Architecture of ETH Zurich, the seminar “The City Represented: The View from the Car as a New Perceptual Regime” that I taught at the Department of Architecture of ETH Zurich, and the exhibition “The View from the Car: Autopia as a New Perceptual Regime” that I curated at the Department of Architecture of ETH Zurich. I would like to thank Prof. Dr. Tom Avermaete for our insightful exchanges in the framework of the aforementioned postdoctoral project and Fredi Fischli and Niels Olsen for our great collaboration for the preparation of the aforementioned exhibition. Finally, I am grateful to the anonymous reviewers of their insightful comments.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Marianna Charitonidou

Dr. Ing. Marianna Charitonidou is architect Engineer, Urban Planner, and historian & theorist of architecture and urbanism. She is a postdoctoral researcher at the Faculty of Art Theory and History of Athens School of Fine arts, where she is conducting the postdoctoral research project “Constantinos A. Doxiadis and Adriano Olivetti’s Post-war Reconstruction Agendas in Greece and in Italy: Centralising and Decentralising Political Apparatus”. She conducted the postdoctoral project “The Travelling Architect’s Eye: Photography and the Automobile Vision”, and the the postdoctoral project “Architecture between Nature and Archaeology: A Transnational and Altermodern Investigation of the Image of Greece” at the School of Architecture of the National Technical University of Athens. Moreover, she curated the exhibition “The View from the Car: Autopia as a New Perceptual Regime” at the Department of Architecture of ETH Zurich (https://viewfromcarexhibition.gta.arch.ethz.ch). In September 2018 she was awarded a Doctoral Degree all’unanimità from the National Technical University of Athens for her PhD dissertation “The Relationship between Interpretation and Elaboration of Architectural Form: Investigating the Mutations of Architecture’s Scope” (jury: Jean-Louis Cohen, Bernard Tschumi, George Parmenidis, Pippo Ciorra, Constantinos Moraitis, Kostas Tsiambaos, Panayotis Tournikiotis), which she is currently editing into two books. In her PhD dissertation she examined the mutations of the modes of representation in contemporary architecture in relation to the transformation of the status of the addressee of architecture. Apart from her PhD Degree, she also holds an MPhil Degree in History and Theory of Architecture and Urbanism (Inter-Departmental Postgraduate Program “Design, Space, Culture”) from the School of Architectural Engineering of the National Technical University of Athens (2013) (MPhil Dissertation Project: “From Semiology to Deconstruction: Metaphysics and Subject”), an MSc Degree in Sustainable Environmental Design from the Architectural Association in London (2011), and a Master Degree in Architectural Engineering from the Department of Architectural Engineering of the Aristotle University of Thessaloniki (2010). She has more than 80 scientific publications focused on architecture and urban planning, and has taught in various schools in Europe – especially in Zurich, Paris and Greece. She is a licensed architect engineer since 2010 and the founder and principal of THINK THROUGH DESIGN architectural and urban design studio. Website: https://charitonidou.com Email: [email protected]

Notes

1. Otto Koenigsberger ‘Tropical Planning Problems’, Paper presented at the Conference on Tropical Architecture, Otto Koenigsberger Archive, AA Archives, 1953.

2. Alison Smithson, ‘New Brutalism’, first page of the two-page unpublished typescript dated 7 March 1955. The Alison and Peter Smithson Archive, Special Collections, Frances Loeb Library, Graduate School of Design, Harvard University.

3. A short essay on Denise Scott Brown’s non-judgmental viewpoint authored by me is to be included in a forthcoming anthology on Denise Scott Brown, edited by Frida Grahn, which is to be published in Birkhäuser's Bauwelt Fundamente series later this year (Charitonidou Citation2022c).

4. David Crane, ‘A working paper for the University of Pennsylvania Conference on Urban Design Criticism’, 4 September 1958, 12. Rockefeller Foundation Archive 1.2/200/457/3904.

5. Robert Venturi, Denise Scott Brown, Steven Izenour, Learning from Levittown Studio, Fall 1970. House style by income category in New Haven, CT. Photos and markers on poster board. Venturi, Scott Brown Collection, The Architectural Archives, University of Pennsylvania.

6. Denise Scott Brown, Robert Venturi, text written for South Street in Philadelphia. Venturi, Scott Brown Collection, The Architectural Archives, University of Pennsylvania.

7. Robert Venturi, John Rauch, and Denise Scott Brown, Architects and Planners, Signs of Life: Symbols in the American City Renwick Gallery, Washington D.C., 1974–1976. Exhibit panel ‘Themes & ideals of the American Suburb’. Venturi, Scott Brown Collection, The Architectural Archives, University of Pennsylvania.

References

- Arefi, M., & Triantafillou, M. (2005). Reflections on the pedagogy of place in planning and urban design. Journal of Planning Education and Research, 25(1), 75–88. https://doi.org/10.1177/0739456X04270195

- Avermaete, T. (2008). A web of research on socio-plastics: team 10 and the critical framing of everyday urban environments. In R. Geiser (Ed.), Explorations in architecture: Teaching design research (pp. 114–115). Birkhäuser.

- Banham, R. (1955). The new brutalism. The Architectural Review, 118(708), 355, 358–361.

- Birch, E. L. (2011). From CIAM to CNU: The roots and thinkers of modern urban design. In Tridib Banerjee & A. Loukaitou-Sideris (Eds.), Companion to urban design (pp. 9–29). Routledge.

- Boyer, M. C. (2017). Not quite architecture: Writing around Alison and Peter Smithson. The MIT Press.

- Charitonidou, M. (2018). Between urban renewal and nuova dimensione: The 68 effects vis-à-vis the real. Histories of Postwar Architecture, 2(2), 1–26. https://doi.org/10.6092/.2611-0075/7734

- Charitonidou, M. (2019). An action towards humanization: Doorn manifesto in a transnational perspective. In N. Correia, M. H. Maia, & R. Figueiredo (Eds.), Revisiting the post-CIAM generation: Debates, proposals and intellectual framework (pp. 68–86). IHA/FCSH-UNL, CEAA/ESAP-CESAP. https://doi.org/10.3929/ethz-b-000451108

- Charitonidou, M. (2020a). Alison and Peter Smithson and their travels to greece: The search for an open-ended morphology. In S. Kousidi (Ed.), Viaggi e Viste. Mediterraneo e modernità, Altralinea edizioni/Momenti di architettura moderna. (pp. 113–128).

- Charitonidou, M. (2020b). Architecture’s addressees: Drawing as investigating device. villardjournal, 2(2), 91–111. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv160btcm.10

- Charitonidou, M (2020c). From the Athens Charter to the “Human Association”: Challenging the Assumptions of the Charter of Habitat. In K. Mohar & B. Vodopivec (Eds.), Proceedings of the international conference of the project Mapping the Urban Spaces of Slovenian Cities from the Historical Perspective. Založba ZRC, 28–43. https://doi.org/10.3929/ethz-b-000426865

- Charitonidou, M. (2020d). The immediacy of urban reality in post-war Italy: Between neorealism’s and Tendenza’s instrumentalization of ugliness. In T. Mical & W. Van Acker (Eds.), Architecture and ugliness. Anti-Aesthetics in postmodern architecture (pp. 223–244). Bloomsbury Academic.

- Charitonidou, M. (2021a). Exhibitions in France as symbolic domination: Images of postmodernism and cultural field in the 1980s. Arts, 10(1), 14. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts10010014

- Charitonidou, M. (2021b). Autopia as new perceptual regime: Mobilized gaze and architectural design. City, Territory and Architecture, 8(5), 1-25. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40410-021-00134-1

- Charitonidou, M. (2021c). The 1968 effects and civic responsibility in architecture and urban planning in the USA and Italy: Challenging ‘nuova dimensione’ and ‘urban renewal’. Urban, Planning and Transport Research, 9(1), 549–578. https://doi.org/10.1080/21650020.2021.2001365

- Charitonidou, M. (2021d). Autopia as a new episteme and new theoretical frameworks: The car-oriented perception of the city. In K. Hislop & H. Lewi (Eds.). Proceedings of the society of architectural historians Australia and the New Zealand: 37, What If? What next? Speculations on history’s futures (pp. 162–173). SAHANZ.

- Charitonidou, M. (2021e). The Travelling Architect’s Eye: Photography and Automobile Vision. In M. Pretelli, I. Tolic, & R. Tamborrino (Eds.), La città globale. La condizione urbana come fenomeno pervasivo/The Global City. The urban condition as a pervasive phenomenon (pp. 684–694). AISU.

- Charitonidou, M. (2022a). Ugliness in architecture in the Australian, American, British and Italian milieus: Subtopia between the 1950s and the 1970s. City, territory and Architecture, 9(9), 1-9. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40410-022-00152-7

- Charitonidou, M. (2022b). The Reconceptualization of the City’s Ugliness between the 1950s and 1970s: The Exchanges between the British, Italian, and Australian Milieus. In D. Kroll & J. Curry (Eds.) Proceedings of the society of architectural historians Australia and New Zealand: 38, Ultra: Positions and Polarities Beyond Crisis. SAHANZ. https://doi.org/10.3929/ethz-b-000487109

- Charitonidou, M. (2022c). Denise Scott Brown’s Nonjudgmental Perspective: Cross-Fertilization between Urban Sociology and Architecture. In F. Grahn (Ed.), Denise Scott Brown In Other Eyes: Portraits of an Architect. Birkhäuser.

- Charitonidou, M. (2022d). Drawing and Experiencing Architecture The Evolving Significance of City’s Inhabitants in the 20th Century. Transcript Verlag.

- Chowkwanyun, M., & Serhan, R. (Eds.) (2014). American democracy and the pursuit of equality. Routledge.

- Cook, J. W., & Klotz, H. (1973). Conversations with Architects. Lund Humphries.

- Crane, D. A. (1960a). The city symbolic. Journal of the American Institute of Planners, 32–39. https://doi.org/10.1080/01944366008978427.

- Crane, D. A. (1960b). Chandigarh reconsidered: The dynamic city. Journal of the American Institute of Planners, 26(4), 280–292. https://doi.org/10.1080/01944366008978427

- Davidoff, P. (1965). Advocacy and pluralism in planning. Journal of the American Institute of Planners, 31(4), 331–338. https://doi.org/10.1080/01944366508978187

- Fontenot, A. (2021). Non-Design: Architecture, liberalism, and the market. University of Chicago Press.

- Gans, H. J. (1962). US in the urban villagers: Group and class in the life of Italian-Americans. The Free Press of Glencoe.

- Gans, H. J. (1966). Popular culture in America: Social problem in a mass society or social asset in a pluralist society? In H. S. Becker (Ed.), Social problems: A modern approach (pp. 549–620). John Wiley and Sons, Inc.

- Gans, H. J. (1967). The Levittowners. Ways of life and politics in a new suburban community. Pantheon Books.

- Gans, H. J. (1968). People and plans: Essays on urban problems and solutions. Basic Books.

- Gans, H. J. (1972). The positive functions of poverty. American Journal of Sociology, 78(2), 275–289. https://doi.org/10.1086/225324

- Gans, H. J. (1974). Popular culture and high culture: An analysis and evaluation of taste. Basic Books.

- Gans, H. J. (2002). The sociology of space: A use-centered view. City and Community, 1(4), 329–339. https://doi.org/10.1111/1540-6040.00027.

- Haumann, S. (2009). Vernacular architecture as self-determination: Venturi, Scott Brown and the controversy over Philadelphia’s crosstown expressway, 1967-1973. Footprint, 3(4), 35–48. https://doi.org/10.7480/footprint.3.1.698.

- Horowitz, D. (2012). Consuming Pleasures Intellectuals and Popular Culture in the Postwar World. University of Pennsylvania.

- Jacobs, J. (1958a). The city’s threat to open land. Architectural Forum.

- Jacobs, J. (1958b). Redevelopment today. Architectural Forum.

- Jacobs, J. (1958c). What is a City?”. Architectural Forum.

- Klemek, C. (2009). The rise & fall of New Lefturbanism. Daedalus, 138(2), 73–82. https://doi.org/10.1162/daed.2009.138.2.73

- Klemek, C. (2011). The transatlantic collapse of Urban Renewal: Postwar Urbanism from New York to Berlin. The University of Chicago.

- Klemek, C. (2014). Jane Jacobs and the transatlantic collapse of urban renewal. In D. Schubert (Ed.), Contemporary perspectives on Jane Jacobs: Reassessing the impacts of an urban visionary (pp. 171–184). Routledge.

- Korn, A. (1953). History Builds the Town. Lund Humphries.

- Kurgan, L., Brawley, D., Zhang, J., & Hui Kyong Chun, W. (2020). Weak ties: The Urban history of an algorithm. e-flux. https://www.e-flux.com/architecture/are-friends-electric/348398/weak-ties-the-urban-history-of-an-algorithm/

- Lee, R. (2017). A Transnational Assemblage. In E. Darling & L. Walker (Eds.), AA Women in Architecture 1917-2017. AA Publications.

- Lichtenstein, C., & Schregenberger, T. (2001). As found: A radical way of taking note of things. In Idem (Ed.), As found, the discovery of the ordinary: British architecture and art of the 1950s (pp. 8–10). Lars Müller.

- Loy, J., & Booth, D. (2004). Social structure and social theory: The intellectual insights of Robert K. Merton. In R. Giulianotti (Ed.), Sport and modern social theorists (pp. 33–47). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Lung-Amam, W. W., Anne Harwood, S., Francisco Sandoval, G., & Sen, S. (2015). Teaching equity and advocacy planning in a multicultural ‘post-racial’. Journal of Planning Education and Research, 35(3), 337–342. https://doi.org/10.1177/0739456X15580025

- Lynch, K. (1964). The Image of the City. The MIT Press.

- Merton, R. K. (1949). Social theory and social structure. Free Press.

- Moran, J. (2012). Imagining the Street in Post-War Britain. Urban History, 39(1), 166–186. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0963926811000836

- Mueller, E. J., & Dooling, S. (2011). Sustainability and vulnerability: Integrating equity into plans for central city redevelopment. Journal of Urbanism: International Research on Placemaking and Urban Sustainability, 4(3), 201–222. https://doi.org/10.1080/17549175.2011.633346.

- Mumford, E. P.(2002). The CIAM Discourse on Urbanism, 1928-1960. MIT Press.

- Orillard, C. (2009). Tracing urban design’s ‘Townscape’ origins: Some relationships between a British editorial policy and an American academic field in the 1950s. Urban History, 36(2), 284–302. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0963926809006294

- Pacchi, C. (2018). Epistemological critiques to the technocratic planning model: The role of Jane Jacobs, Paul Davidoff, Reyner Banham and Giancarlo De Carlo in the 1960s. City, Territory and Architecture, 5(17), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40410-018-0095-3

- Pilat, S. Z. (2016). Reconstructing Italy: The Ina-Casa Neighborhoods of the Postwar Era. Routledge.

- Quaroni, L. (1967). La Torre di Babele. Marsilio Editore.

- Rao, M. V. (2012). Paul Davidoff and planning education: A study of the origin of the urban planning program at Hunter College. Journal of Planning History, 11(3), 226–241. https://doi.org/10.1177/1538513212436518

- Rattenburry, K., & Hardigham, S. (2007). Supercrit #2. Robert Venturi and Denise Scott Brown. Learning from Las Vegas. Routledge.

- Robbins, D. (ed.). (1990). The independent group postwar Britain and the aesthetics of plenty. The MIT Press.

- Scimemi, G. (1956). La quarta scuola estiva del CIAM a Venezia. Casabella Continuità, 213, 69–73.

- Scott Brown, D. (1976). On Architectural Formalism and Social Concern: A Discourse for Social Planners and Radical Chic Architects. Oppositions, 5, 99–112.

- Scott Brown, D., & . (1965). The meaningful city. Journal of the American Institute of Architects, reprinted in Harvard’s Connection, Spring 1967, 27–32.

- Scott Brown, D. & R., Venturi. (1969). Learning from Lutyens: Reply to Alison and Peter Smithson. RIBA Journal, 353–354.

- Scott Brown, D. (1971). Learning from Pop. Casabella, 15–23, 359–360.

- Scott Brown, D. (1982). Between three stools: A personal view of urban design practice and pedagogy. In A. Ferebee (Ed.), Education for urban design (pp. 132–172). Institute for Urban Design.

- Scott Brown, D. (1984a). A worm’s eye view of recent architectural history. Architectural Record, 172(2), 69–81.

- Scott Brown, D. (1984b). Learning from Pop. In R. Venturi & D. Scott Brown (Eds.), The view from the Campidoglio. Selected essays 1953–1984 (pp. 28–31). Row.

- Scott Brown, D. (1990a). Learning from Brutalism. In D. Robbins (Ed.), The independent group: Postwar Britain and the aesthetics of plenty. MIT Press. (pp. 203–206).

- Scott Brown, D. (1990b). Paralipomena in Urban Design. In D. Scott Brown & A. C. Papadakis (Eds.), Urban concepts (pp. 6–29). Academy Editions/St. Martin’s Press.

- Scott Brown, D. (1990c). The Rise and Fall of Community Architecture. In D. Scott Brown & A. C. Papadakis (Eds.), Urban concepts. (pp. 31–39). Academy Editions/St. Martin’s Press.

- Scott Brown, D. (1996). Lavorando per Giuseppe Vaccaro. Edilizia Popolare, 243, 5–13.

- Scott Brown, D. (2003). Learning from Brinck. In C. Wilson, P. E. Groth, & P. Groth (Eds.), Everyday America: Cultural landscape studies after J. B. Jackson (pp. 37–48). University of California Press.

- Scott Brown, D. (2004a). Some Ideas and Their History. In D. Scott Brown, Venturi, R. (Ed.), Architecture as signs and systems: For a mannerist time (pp. 105–119). Belknap.

- Scott Brown, D. (2004b). The redefinition of functionalism. In D. Scott Brown, Venturi, R. (Ed.), Architecture as signs and systems: For a mannerist time (pp. 142–174). Belknap.

- Scott Brown, D. (2009). Towards an ‘Active Socioplastics‘. In Denise Scott Brown, architecture words 4: Having words. (pp. 22–54). Architectural Association.

- Scott Brown, D. (2015). Towards an ‘Active Socioplastics’. In M. Chowkwanyun & R. Serhan (Eds.), American democracy and the pursuit of equality (pp. 73–98). Routledge.

- Scott Brown, D. (2016). Studio: Architecture’s offering to academe. ARPA Journal, 4. https://arpajournal.net/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/Denise-Scott-Brown-Studio-ARPA-Journal.pdf.

- Scott Brown, D. (2021). “Studio: Architecture’s offering to academe, MAS Context, May 26 (2021). https://www.mascontext.com/observations/studio-architectures-offering-to-academe/

- Scott Brown, D., Venturi, R. (1984). Learning from lutyens: Reply to Alison and Peter Smithson. In R. Venturi & D. Scott Brown (Eds.), The view from the Campidoglio. Selected essays 1953–1984 (pp. 20–23). Row.

- Scott Brown, D., & Venturi, R. (2004). Architecture as signs and systems: For a mannerist time. Belknap.

- Scott Brown, D., Venturi, R., & Izenour, S. (1972). Learning From Las Vegas. The MIT Press.

- Smithson, A. (1969). The responsibility of lutyens. RIBA Journal, 146–151.

- Smithson, P. (1969). The viceroy’s house in imperial Delhi. RIBA Journal, 152–154.

- Smithson, A. (1983). AS in DS: An eye on the road. Delft University Press.

- Smithson, A. (2001). AS in DS: An eye on the road. Lars Muller Verlag.

- Smithson, A., & Smithson, P. (1960). Louis Kahn. Architects’ Yearbook, 9, 102–118.

- Stierli, M. (2007). In the academy’s garden: Robert Venturi, the grand tour and the revision of modern architecture. AA Files, 56, 42–63. https://www.jstor.org/stable/29544672.

- Stierli, M. (2010). Taking on mies: Mimicry and parody of modernism in the architecture of Alison and Peter Smithson and Venturi/Scott Brown. In M. Crinson & C. Zimmerman (Eds.), Neo-avant-garde and postmodern postwar architecture in Britain and beyond. Yale University Press. (pp. 151–173).

- Troiani, I. S. (2005). The Politics of Friends in Modern Architecture, PhD Dissertation, School of Design, Queensland University of Technology.

- Van Bergeijk, H. (2010). CIAM summer school 1956. OverHolland, 9, 113–124. https://doi.org/10.7480/overholland.2010.9.1639

- Von Moos, S. (1999). Penn’s Shadow. In Venturi, Scott Brown & associates: Buildings and projects—1, 1986-1998 (pp. 11–23). The Monacelli Press.

- Young, M., & Willmott, P. (1957). Family and kinship in east London. Routledge; Kegan Paul.