?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

The study assessed the residents’ perception of privacy and their privacy regulating mechanisms with a view to providing information that could improve public housing design. The study used quantitative and qualitative approach. A sample size of 565 household heads was selected for questionnaire administration using systematic random sampling, representing 50% of the sampling frame. In-depth interviews were conducted on twelve (12) key informants from among the executive of neighbourhood associations. Descriptive and inferential statistics were used to analyse quantitative data while content analysis was used for the qualitative data. About half of the residents (50.38%) perceived privacy as low or very low, with visual privacy being rated least (Privacy Perception Index, PPI = 2.34), followed by family (2.22), olfactory (2.12), aural (2.00), neighbourhood (1.79) and personal privacy (1.64). Positioning of spaces, orientation of openings, and absence of dedicated guest room, contributed to low perception of visual and family privacy. About 92% of the respondents agreed or strongly agreed to the use of privacy regulating mechanisms, with personal space and territorial behaviour being more adopted, while non-verbal behaviour was least adopted. The study concluded that perception of privacy was influenced more by housing characteristics than by residents’ socio-economic and cultural characteristics.

1.0 Introduction

Public housing, in particular, refers to housing that is financed, constructed or allotted by the state, especially for people of low and medium income (Eni, Citation2014; Ilesanmi, Citation2010). Many governments in developing nations of the world have initiated public housing schemes, some of which have been evaluated in terms of affordability and adequacy (Ibem, Citation2011; Ilesanmi, Citation2005). Housing should not only be affordable and adequate but be sensitive to the privacy needs of the residents (Tao, Citation2018). Privacy has been defined in different contexts and acquired a variety of interpretations. It is the ability of an individual or group to seclude themselves, or information about themselves, and thereby express themselves selectively (Altman, Citation1975). According to L. Altman (Citation1976), privacy is a selective control of access to the self and to one’s group. Privacy is a universal value that has been studied in diverse disciplines, including: Law, Information Technology, Environmental Psychology, Architecture, Sociology and Media studies (Gavison, Citation1980; Trepte & Reinecke, Citation2011; Namazian & Mehdipour, Citation2013; AlKhateeb, Citation2015; Anthony et al., Citation2017; Sarikakis & Winter, Citation2017;). In the built environment, privacy is the ability of individuals or groups to control visual, auditory and olfactory interactions with others. Its main functions are: restraining social interaction; establishing mechanisms for regulating interaction and developing self-identity (Tomah, Citation2011).

The study of privacy is particularly important in the context of public housing because it has been identified as a means of controlling overcrowding, developing sense of identity and territoriality, maintaining personal autonomy and self-evaluation, and providing protected information, social behaviour and the healthy relation of the individual within society (Ahmad & Zaiton, Citation2008). Public housing has been criticized for not being designed in accordance with residents’ privacy needs and sensitivity to socio-cultural factors (Kennedy et al., Citation2015; Liu, Citation2016).

Meanwhile, privacy is an important socio-cultural factor influencing house form (Rapoport, Citation2005). Some cultures have stronger preferences for privacy than others (Altman & Chemers, Citation1980; Zaiton, Citation2018). The need for privacy is universal; the approaches for regulating it differ considerably across cultures (Othman et al., Citation2015). Privacy can be regulated in two broad ways. First, is through behavioural means attained by structuring events in time, such as cues, roles, manners and hierarchies. Second, is by means of environmental mechanisms like separation of spaces and the use of physical components such as partitioning walls, fences, curtains.

Privacy is one of the most essential aspects of housing quality that has however not received adequate attention, especially with regards to public housing. A common notion about public housing environments is that they seldom provide the privacy that people desire (Tao, Citation2018). Among these is the lack of attention to residents’ privacy in contrast to the more culturally sensitive traditional residential environments (Alitajer & Nojoumi, Citation2016). It has been suggested that design concepts that are non-complimentary to existing cultures are often imported and wrongly adapted. Moreover, many public housing options are driven by economic factors than socio-cultural and psychological considerations (Tomah, Citation2011). Therefore, the challenge of enhancing privacy through architectural design is becoming a subject of emergent concern for residents, architects and researchers (Heydaripour et al., Citation2017).

Residents’ socio-economic attributes have been found to influence privacy (Margulis, Citation2003). However, public housing is usually designed without the input of the prospective residents, and their personal, socio-economic and cultural characteristics, are rarely considered. Studies on privacy reveal differences in its perception and practices, relative to age, gender, socio-economic status, family size, family life cycles, age of children and other factors that may influence perspectives to privacy.

Tomah (Citation2011) establish that the need for privacy varies with age. Pedersen and Frances (Citation1990) found that differences in socio-economic status also influence the desire and need for privacy, with privacy norms being less strict in low-income than high-income groups, as the former’s crowded living environments force a lack of privacy. Wealthy populations require extra visual privacy demands to be secluded from the economically disadvantaged sectors of the population. This study will build upon these empirical findings, particularly in the rarely studied context of public housing.

Privacy also relates to gender, religion and culture. Abdul Rahim (Citation2015, Citation2018) examined the role of culture and religion in the regulation of visual privacy and design attributes influencing it. He concluded that the concept of privacy in the traditional Malay society was based on gender roles, the position of women and separation of genders. The Islamic system disapproves of intermingling between unrelated members of the opposite sexes, and restricts the privacy boundaries of individuals, with significant effects on housing design. However, many of the studies on privacy in relation to residents’ characteristics have been in the contexts of Middle Eastern societies, with emphasis on culture and religion (Abdul Rahim, Citation2018; Othman et al., Citation2015).

Al-Hamoud (Citation2009) investigated the connection between privacy control and personal space expressed by the physical components of the quality and quantity of bedroom space in single-family homes. Bekleyen and Dalkiliç (Citation2011) examined the design characteristics of indigenous courtyard houses of Diyarbakir, Turkey, in terms of the effects of climate and privacy measures. Heydaripour et al. (Citation2017) examined the layout of modern apartments in Iran from privacy perspectives, in order to establish a framework to improve their spatial order. It is accordingly fundamental to analyse housing and neighbourhood characteristics in a public housing context.

As indicated by Altman (Citation1975), L. Altman (Citation1976), privacy is measured as either desired or achieved; and significantly in three measurements: visual, acoustic and olfactory (Omid et al., Citation2017; Zaiton, Citation2018). Visual privacy alludes to the openness of relatives inside the home and from neighbours and outsiders; auditory privacy is the shielding of residents from surrounding noise; and olfactory privacy alludes to the control of scents, fragrance or smell. Visual privacy gives off an impression of being the main part of privacy hence, most examinations on privacy levels have focused on visual privacy. The value ascribed to visual privacy does not however exclude the importance of auditory and olfactory privacy in the house. This study therefore assessed privacy levels in public housing based on the three types of privacy.

In essence, studies on privacy have been restricted to: assessing the conception and alteration of privacy, the obligation of social and cultural patterns and religion (Razali and Talib, Citation2013; Abdul Rahim, Citation2015, Citation2018; Hosseini et al., Citation2015), the investigation of a particular space inside the house, like the room (Al-Hamoud, Citation2009) or a house type, for example, courtyard houses (Bekleyen & Dalkiliç, Citation2011; Hosseini et al., Citation2015) and flats (Heydaripour et al., Citation2017).

The context of study

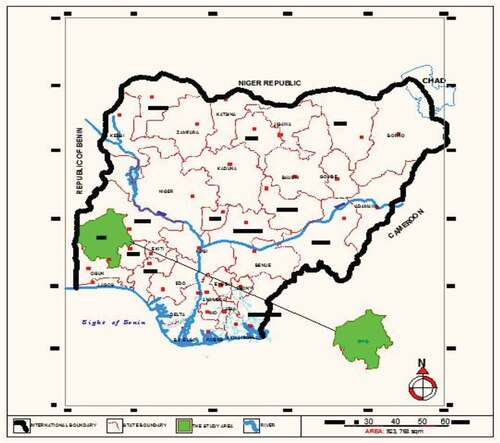

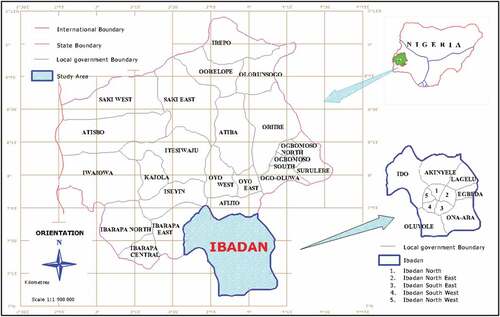

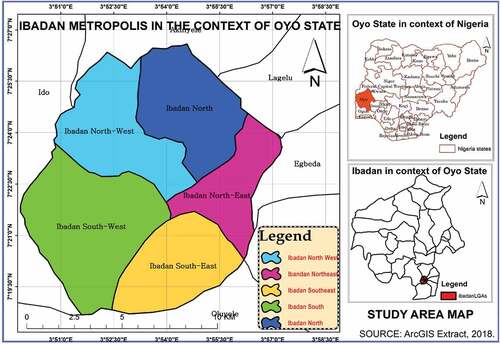

Ibadan is considered to be an appropriate context for the study, being representative of evolving cities in the developing world, where despite the cosmopolitan nature, cultural characteristics still strongly influence residents’ lifestyles (Tomori, Citation2012). Moreover, the public housing estates in Ibadan have been in existence long enough to provide the expected data. Based on this background, this study examined the residents’ perception of privacy and their privacy regulating mechanisms in selected public housing estates in Ibadan, with a view to enhancing future public housing design. Presently, the city comprises of eleven Local Government Areas, five within the city centre, while six are at sub-urban (Iddo, Lagelu, Oluyole, Akinyele, Egbeda, Ona-Ara) as shown in .

2.0 Literature review

Privacy has been characterized in various settings and gained a variety of implications. It has been studied in various discourses. All the more, as of late, the investigation of privacy developed in architecture (AlKhateeb, Citation2015). From an environmental understanding viewpoint, privacy is characterized as the condition of being separated from group or perception (Namazian & Mehdipour, Citation2013). Accordingly, the term ‘privacy’ is firmly corresponded with the word ‘seclusion’ and contrasted with the words such as ‘public’ and ‘social’.

From housing perspective, privacy is fundamentally recognized as an imperative mechanism for controlling congestion and maintaining an healthy relation of the individual within society (Tao, Citation2018; Zaiton, Citation2018). Privacy gives independence from unapproved interruption. In spite of the different definitions, characterizing privacy regarding housing stays a difficult assignment since it involves a conceptualization of certain spatial conditions coming from the countless social relations between relatives, households and neighbours. Privacy is dynamic, implying that it continually goes through adjustments as far as delivering social relations, yet additionally constantly impacting spatial variations in built forms. Privacy is a spatial setup that produces social relations (Ahmad & Zaiton, Citation2010). In connection to architecture, Pedersen & Frances, Citation1990) stated that privacy is tied in with opening and closing obstructions, and underlined the significance of privacy practical profile to designers. For Al-Thahab et al. (Citation2014), privacy identifies with the connection among private and public spaces inside the house.

According to another point of view on the usefulness of privacy, Hall (Citation1990) fostered the hypothesis of proxemics which was inspected by Griffin (Citation2006) and analysed culture as a factor influencing privacy. Proxemics, which is applicable for implementation in the work of architects, relates to the individual and the space around him; a space which he gets control over to arrive at the required level of privacy (Bekci & Özbilen, Citation2012). According to Hall (Citation1990), individual space was diverse between people according to their social background. Edwards (Citation2010) stressed the significance of Hall’s idea in design as it addresses dynamic and non-verbal correspondence and can assist designers with understanding the residents’ privacy needs in spatial design. The insight and levels of privacy vary between societies as the Western idea of privacy is not the same as its Eastern partner.

The Eastern points of view on privacy vary from the Western as the Eastern culture esteems the privacy of the family as a unit and supersedes the significance of individual privacy. In some Eastern societies, there is no particular word for privacy (AlKhateeb, Citation2015). In Japanese culture, for instance, the possibility of private circles that are autonomous of the gathering isn’t worthy. The Arabs were found to lean toward living in huge spaces for family assembly and avoid partitions in their plan. Curiously, the conventional Yoruba additionally positioned more significance on communal closeness instead of individual closeness as the ideas of sharing and participation is significant to the Yoruba culture (Jiboye, Citation2009). The plan of the conventional Yoruba house has been directed by the social traditions of the Yoruba that were affected by religion, for example, the arrangement of a private space for womenfolk and a public space for engaging male visitors during gathering (Ekhaese & Adeboye, Citation2014).

The idea of family privacy which was a significant building component in conventional Yoruba house has for some time been excluded from public housing plan. Ibem (Citation2011) expressed that the plan for the majority of the house accessible in the market particularly social housing in Nigeria don’t consider privacy since it isn’t viewed as a significant spatial restrictions by the public authority. Salama and Alshuwaikhat (Citation2006) proposed that many architects and engineers looked at design and affordable as exclusive and are looked at in isolation.

There are various empirical studies on privacy and the assessment of privacy in public housing. The conceptual and theoretical models of privacy include: Privacy Regulation Theory, Proxemics Theory and Congruence Model (Al-Thahab et al., Citation2014; Altman, Citation1977; Daneshpour et al., Citation2012; Edwards, Citation2010; Hall, Citation1990; Kiyak & A, Citation1978; Memarian et al., Citation2011; Witte, Citation2003). Evidence in literature reveals that over the years, authors used contrast theories as well as comparison approach to model these studies. In any case, most exact investigations on privacy draw on the worldview that whenever desired privacy surpasses acquired privacy, residents might not be able to control their region, leading to overcrowding while whenever acquired privacy surpasses required one, it might prompt isolation (Altman, Citation2013a). A portion of these empirical studies analysed the characteristics of the residents (compositional) or attributes of the environment (contextual) – physical, social and cultural (Ahmad & Zaiton, Citation2010; Alitajer & Nojoumi, Citation2016; Margulis, Citation2003; Othman et al., Citation2015). These sets of compositional and contextual attributes have been seen as the reasonable factors that decide residents’ perception of privacy and responses to privacy needs.

Empirical studies have distinguished various significant factors identifying with residents’ attributes like age, gender, income, educational background and personality (Aliens, Citation2011; Memarian et al., Citation2011). Age applies a positive effect on privacy needs and levels. Older residents will in general be more contented with low privacy levels than youthful individuals (Liu, Citation2016; Shabani et al., Citation2011). Kiyak and A (Citation1978) revealed that the privacy needs of old residents are likely to be lower than those of more youthful residents. Walden et al. (Citation2011) likewise argued that empirical discoveries of privacy ought to be classified by family scope.Yeun et al. (Citation2006) also discovered a huge connection between income and privacy. Past works by Fahey (Citation1995) stressed that higher pay permits households to move to a reasonable house in a secured neighbourhood which might bring about a relatively higher level of privacy.

Memarian et al. (Citation2011) looked at the privacy and hospitality trends of houses in Kerman while Othman et al. (Citation2015) related the perceived concept of privacy inside Muslim homes. They found that there were huge contrasts between the residents’ understanding of privacy and residents’ socio-economic characteristics. Margulis (Citation2003) noticed that the higher the education level of the household heads, the more satisfied they were with their housing equated with those with lower educational attainment.

As indicated by Daneshpour et al. (Citation2012), housing attributes were more vital determinants of perception of privacy than demographic attributes of housing residents. Consequently, empirical studies show that building factors like number, size, area and plan of spaces like room, kitchen and toilet, were unequivocally identified with privacy. Liu (Citation2016) tracked down a positive connection between number of rooms and privacy. He likewise discovered a pessimistic association between individual per-room proportion and privacy in social housing. As the number of people per-room rises, establishing a higher density environment, a privacy level diminishes. Liu (Citation2016) in a review of public housing privacy in Hong Kong additionally found that while the residents were profoundly happy with the cost of the house acquired, they were not happy with the size of spaces like kitchen, room and public facilities like recreational area and private playground in the housing environment.

Ahmad and Zaiton (Citation2010) investigated the housing attributes identified with privacy and found that building design, spatial arrangement of the structure, size of room, fittings and fixtures design, design of living and kitchen, positioning of fittings like entryways, windows, material of building elements and finishes, comfort and security in the house were identified with privacy. Ibem and Aduwo (Citation2013) in an appraisal of residential satisfaction in the public housing in Ogun State, Nigeria, observed that while the residents of public housing in Ogun were contented with privacy inside neighbourhood they were dissatisfied with privacy inside housing units because of size, number, position of certain spaces and facilities in the house.

Location qualities are significant factors for understanding the perception of privacy among public housing residents. Attributes of the neighbourhood, for example, location of playground are probably going to affect privacy. Djebarni and Al-Abed (Citation2000) observed that the residents of low-income housing in Yemen, appended extraordinary significance to the degree of satisfaction with their neighbourhood, especially, with privacy which indicates the social foundation of Yemeni society (Bekci & Özbilen, Citation2012).

Behavioural characteristics of residents, for example, housing adjustment and adaptation as conceptualised by Ahmad and Zaiton (Citation2010) are the residents’ responses to adjust the discrepancies between the housing they have and what they believe they ought to have. A conflict among required and acquired privacy resulted to some form of modification. Housing modification in this setting might be as alteration of privacy needs to accommodate the uniqueness, or improvement of housing conditions through housing alteration, or, in all likelihood there could be displacement to somewhere else that brings housing into congruity with residents’ desires or needs (Ahmad & Zaiton, Citation2010). Ahmad and Zaiton (Citation2010) called attention to that housing alteration comprises could adopt two strategies: (a) expansion in the measure of room or number of rooms in the housing; and (b) improvement in privacy of the residence. Consequently, changes and additions are regular methods of responding to privacy needs in housing.

The methodical approach has been utilized in examining privacy in the built environment (Margulis, Citation2003). Ramezani and Hamidi (Citation2010), exploiting the methodical way to studying privacy inside traditional towns to contemporary metropolitan in Iran, established privacy as an issue comprising of four associating parts. These are: the residents, housing unit, neighbourhood and environment, which produce a housing condition that the inhabitant’s elements (personality and demographic attributes) agreed as acceptable as per privacy needs.

Drawing from the above conception, interaction of the different components of the privacy model acts as a stimulus to an individual who forms a perceptive image of self and each of the components in the residential system. Such a reasoning image formed by a resident through the perception process becomes the basis of his or her attitude towards each of the components. Features, such as number of bedrooms, size and location of kitchen were strongly related to the model. Location of neighbourhood facilities such as gardens, schools and community social centre has been noted to be an important factor of privacy. Al-Hamoud (Citation2009) in a study of privacy control as a function of personal space in Single-Family Homes in Jordan reported that the residents were pleased with privacy within housing units but dissatisfied with privacy within the neighbourhood.

Mohit et al. (Citation2010) conversely found that residents in social housing in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, appended a lot of significance to the degree of privacy inside their communities, in consonance with the cultural context of Kuala society. Liu (Citation2016) established that neighbourhood attributes are essential to understanding privacy in the public housing. Housing design attributes and neighbourhood attributes, for example, nearness and location are major factors influencing privacy in public housing. Al-Thahab et al. (Citation2014) analysed spatial frameworks of privacy in domestic Architecture of Contemporary Iraq and realised that both housing and neighbourhood characteristics contributed emphatically to privacy.

AlKhateeb (Citation2015) established that in spite of the fact that socio-economic factors, for example, gender were considerably more significant components in the perception of privacy in contemporary Saudi houses, neighbourhood qualities remained important determinants of privacy, when residents’ perspectives were considered. Djebarni and Al-Abed (Citation2000) in an examination on satisfaction level with neighbourhoods in low-income public housing in Yemen discovered neighbourhood characteristics to be predominant variables influencing the levels of housing privacy.

The assessment of privacy in housing is typically founded on various dimensions in accordance with the philosophical orientation and background of researchers as well as the motivation behind the assessment. This led to various dimensions of assessment of privacy in housing. Shahab et al. (Citation2015) demonstrated that housing privacy has been assessed regarding physical, social and cultural dimensions. Liu (Citation2016) recognized architectural (design and material), sociological (safety) and economic (cost effectiveness) as dimensions of privacy examined. Shahab et al. (Citation2015) established that investigation of privacy in housing environment can be classified into three dimensions, specifically, physical, social and cultural dimensions. These dimensions of assessment of privacy include various events. First is the assessment of physical and design attributes of housing. This includes the design and organization of spaces, the distance and accessibility, spatial design and interrelationship of spaces just as function of space in meeting social, physiological and privacy needs of residents.

Second viewpoint concerns the social dimension of privacy assessment which fundamentally analyses social relationship, ties and social connection existing among residents. This dimension of assessment is essentially founded on the opinion that privacy can be utilized to develop individual personality and social relationship (Rustemli & Kokdemir, Citation1993). According to Wills (Citation1963), the idea of social relationship in the neighbourhood could go from basically no association to level of participation and closeness with neighbour. She referenced that social dimension of privacy vary starting with one individual to another. The social dimension of privacy assessment in this manner centres on the assessment of the diverse socio-economic groups living inside a characterized residential setting to comprehend and suggest their behavioural attitudes to privacy needs inside neighbouring environment. For example, Hashim (Citation2003) in an examination of social incorporation in the social housing in Malaysia found that default in physical structure and deprived social and physical settings do influence social interaction among residents of public housing and neighbourhoods.

Third, the cultural dimension of privacy assessment identifies issues of social standards, belief and custom. This has been the emphasis of many evaluations. This host of studies (Al-Thahab et al., Citation2014; Altman, Citation1977; Rapoport, Citation1969; Sobh & Belk, Citation2011; Zaiton, Citation2018) concentrated on the perception and cultural attributes of residents in housing units and encompassing neighbourhood with accentuation on some theoretical and methodical issues identified with the study of privacy.

From the above mentioned, it is clear that privacy has been assessed at various dimensions. These incorporated the physical, social, cultural dimensions. It can be concluded that the different dimensions of privacy examined in public housing involved resident’s perceptions and responses to privacy needs. These dimensions of privacy were considered as appropriate determinant factors of privacy and utilized in the current research.

Notwithstanding the various dimensions of privacy investigated, there are likewise levels of privacy studied. Othman et al. (Citation2015) recognized five levels of privacy in housing, which proposes that privacy can be assessed at five unique, however related levels of inner spaces, housing units, street, neighbourhood and community levels. Privacy is understood as the organization of spaces at the internal spaces level (Ahsen and Gulcin, Citation2005). Proximity, accessibility and position of spaces like room and kitchen are the critical parts at these levels of privacy examined according to Al-Thahab et al. (Citation2014).

The empirical studies revealed that a large group of factors has a place with housing and its contexts including the socio-economic characteristics of residents which apply critical impacts on the perception of privacy and responses to privacy needs. It likewise revealed from the past empirical studies on privacy that while different housing, neighbourhood and residents attributes determined the level of privacy, privacy dimension and behaviour, the effects of these factors as determinants of perception of privacy tend to vary by personalities, socio-economic background and cultures.

3.0 Methodology

Qualitative and the survey research method were the research design adopted for this study. Data for this study were derived from primary and secondary sources. Quantitative primary data were obtained by means of questionnaire administration, while qualitative primary data were obtained through key informant interview and physical observation. The secondary data were derived from various sources such as published materials in books, journals and housing demographics from Oyo State Housing Corporation.

Study Population for this research consists of all household heads in four out of six public housing estates managed by Oyo State Government. The study population for the Old Bodija Estate is 466, Olubadan Estate is 114, Owode Estate is 280 and Ajoda New Town is 270 making a total of 1130 household heads. These four estates meet the inclusion criteria. Bashorun Estate and Akobo Estate are also allocated by Oyo State Government under site and service scheme but do not meet the inclusion criteria. These two estates were not designed and constructed by the State Government but only allotted and managed.

A combination of two sampling methods was considered appropriate for this research. These two sampling methods were the Purposive and Systematic Random Sampling Method. The sampling frame of the housing units consisted of 1130 household heads in the four purposively selected public housing estates design, developed, completed and allocated by Oyo State Government namely: Bodija Estate; Owode Estate; Ajoda New Town; Olubadan Estate (). A sample size of 565 household heads representing 50% of the sampling frame was selected using the systematic random sampling method. The first house was selected randomly and subsequently every 2nd house in the street was systematically selected for questionnaire administration on the household head or his representative.

Table 1. Sample size of household heads in the housing units

Three principle data gathering instruments were utilized in gathering the essential data for this investigation, to be specific: the questionnaire, the semi-organized interview guide and observation schedule. The questionnaires were designed for the residents of the housing units, the interview guide for key informants, while the observation schedule was for the expert’s utilization. The questionnaire covered every parts of the study objectives. These encompassed questions on: the social-economic and cultural attributes of residents, the housing and neighbourhood attributes, the residents’ perception of privacy and the residents’ privacy regulating mechanisms. The surveys included both closed and open-ended inquiries.

The close-ended questions obtained exact opinion while the open-ended ones permitted the respondents to give more intricate answers and clarifications where proper. For close-ended questions, a 5-point Likert scale (1–5) was utilized as the scale of evaluation for the data on the residents, the housing and neighbourhood attributes; the residents’ perception of privacy and the residents’ privacy regulating mechanisms. The inquiries in the surveys were arranged in areas as per the groupings of the factors as gotten from the significant exploration issues in the investigation (see Appendices 1 and 2).

For the interviews, an interview outline was prepared. This instrument was utilized on total of twelve (12) key informants from among the executive landlord of neighbourhood associations in the four public housing estates. The interview sessions were directed by a definite interview outline designated at gathering issues that couldn’t be comprehensively inspected through the survey. It comprised of a list of issues that were asked in the interviews (see Appendix 3). A portion of the inquiries were phrased in a foreordained style. The conduct of the interviews followed the adoption of standardized format of interview.

The observation schedule was arranged essentially to record observations made by the analyst (experts) during the field work (Appendix 2). This data assortment instrument was utilized in the gathering of data relating to the physical characteristic of the housing units and neighbourhoods in the housing estates examined. Among the data this instrument designed to collect were: housing typology, types of walling, roofing and ceiling materials, wall finishing, type of windows and doors, burglary proof on windows, burglary proof on external doors, type of floor finish, layout of the estate, types of partition, perimeter fencing, security post at entrance, location of openings, location of windows, territorial makers and orientation of buildings. The secondary data utilized were likewise sourced from secondary sources. A visit to the housing authority (Oyo State Housing Corporation OSHC) to acquire secondary data, for example, land-use plan, details of the various typologies and their architectural drawings, master plan and total number of authorized households among others in each of the selected estates.

Quantitative data analysis comprised of descriptive analysis such as Frequency distribution, Percentages and Cross tabulation and inferential statistical analysis such as Analysis of Variance and Chi Square. Qualitative data analysis was mainly from non-statistical analytical tool such as content analysis.

Both descriptive and inferential statistical analyses were used for the study. The first was to obtain frequencies and percentages while the second was to develop Perception of Privacy Index (PPI). Summation Weight Value (SWV) or Variables Score (VS) were used to measured responses from residents so as to gain a better understanding of their perception of privacy.

In the first approach, 5-point Likert scale of: Strongly Agree, Agree, Neutral, Disagree, Strongly Disagree was, respectively, assigned a value of 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 for all the fifty (50) questions used to measure perception of privacy. This implied that the range of scores for each respondent for all the fifty (50) questions would be between 50 (50x1) and 250 (50x5).

In the second approach, the sum of individual respondents’ score on all perception of privacy variables is referred to as individuals’ overall perception score (IS). The total scores given by all the respondents (565) to each of the perception of privacy variables is the Summation of Weight Value (SWV) or variables score (VS).

The Summation of Weight Value (SWV) for each perceived variable was obtained by adding the product of responses for each variable and their respective weight value.

Mathematically, this is expressed in Equationequation 3.1(3.1)

(3.1) :

Where:

SWV = Summation of Weight Value of each of the fifty (50) questions

Xi = number of respondents choosing a particular rating i

Yi = the weight assigned a value (i = 1, 2, 3, 4, 5)

For instance, to measure the level of perception to which the residents of the selected public housing estate attached to the types and levels of privacy, the formula to use is given in Equationequation 3.2(3.2)

(3.2) below.

Where PPI = Privacy Perception Index

The SWV is divided by the number of respondents (565 household heads) to give the Privacy Perception Index (PPI). For ease of measurement, the perception is thus measured using an index. This method was employed to measure the perception of the respondents on the level of privacy in the study area. It must be noted that the closer the PPI of a factor is to five (5) the lower the assumed perception of privacy. The Mean Index (X) used was also obtained by summing up the PPI and dividing it with the total number of variables. The deviation and standard deviation were also calculated to be able to establish the level of perception of privacy. From this calculation, a positive indicates a low level of perception of privacy, and when the deviation is negative, it depicts a high level of perception of privacy.

SWV and PPI were used in assessing the contribution of each of the 50 variables to overall perception of privacy and perception of privacy across the four estates. The total scores on each privacy type and level by all the respondents is the Privacy Perception Scores (PPS), while the total possible Mean Index that can be given by all the respondents on each of the six privacy types and levels is the Aggregate Privacy Perception Index (API). For the purpose of comparing the level of perception of each of the six privacy types and levels used in this study across the four estates, Privacy Perception Index (PPI) was calculated by summing up the API and dividing it with the total number of variables (N). This is expressed mathematically as: PPI = API/N.

4.0 Analysis, findings and discussions

4.1 Socio-economic and cultural characteristics of residents

A total number of 565 residents were sampled in the study area, 73.5% of males respondents were young adults (48.1%) between the ages of 31 and 45 years. Majority (84.2%) of the residents were married and predominantly of the Yoruba extraction, who had tertiary education (85.1%) and lived as either renters (47.8 %) or home-owners (46.2%). A concentration of the Yoruba ethnic group in the estates aligns with Zaiton (Citation2018), in that members of the same ethnic groups prefer to agglomerate in order to feel more secure and are more likely to integrate with each other in such kind of neighbourhood. The Christian population in these housing estates was more in number than other religions, and this might have influenced the predominantly monogamous family settings within the estates.

About half (53.6%) of the respondents were Civil servants, who rented mainly apartments in blocks of flat or owned semi-detached bungalows within the estates. More than half of the residents had stayed within the estates for less than ten years, while a lesser proportion of the residents had stayed for between 31 and 40 years. Majority (84.0%) were single-family; mainly small-sized household (56.6%) with majority had 1–3 male and female children not co-habiting (see, ).

Table 2. Socio-economic and cultural characteristics of residents

With respect to age, marital status, religion, occupational status, level of education, type of tenure system, among others, significant variations existed among the public housing estates, as confirmed in summary of ANOVA and Chi-Square test (). With such significant variation, it is expected that the housing and neighbourhood characteristics as well as residents’ perception of privacy and privacy regulating mechanisms would vary as well.

Table 3. Summary of ANOVA and Chi-Square of the socio-economic and cultural characteristics of residents across the four public housing estates

4.2 Housing and neighbourhood characteristics

The housing characteristics showed that types of houses originally provided was majorly block of flats (47.4%) and semi-detached Bungalows (23.7%). Majority of these houses were provided with entrance porch (51.7%), living room (97.0%), dining room (62.3%), kitchen (95.4%), bedroom (100.0%) and toilet (96.8%) (see, .

Table 4. Types of houses originally provided

Table 5. Types of spaces provided in the house

However, the respondents required spaces such as guest room, visitors’ toilet, study room, laundry and balcony. reveals that most of the walls were finished with cement screed, apart from the walls of kitchen and toilet that were finished with tiles. The floors were also predominantly (86.5%) finished with tiles for all the spaces.

Table 6. Wall finishing materials

Generally, the entrance door faced the street, bedrooms were positioned at the rear side, and the bathroom was shared by two bedrooms. The orientation of the bedroom, kitchen and toilet windows faced the balcony while the orientation of the living room window was toward the street. Observation from the field survey revealed that majority of the residents with bedroom windows facing either the street or opposite neighbour’s house had replaced the original louvers blades with tinted sliding windows. One of the respondents during an interview had this to say:

It is quite unfortunate that two out of three bedrooms’ windows in my houseare facing the street. I don’t have any choice than to change the windows to asuitable type for my family privacy.

Louvre types of windows were predominantly used. The window height of the bedroom, living room and kitchen was typically 0.9 m normal level, while that of toilet was above normal level. The window sizes of the bedroom, living room and kitchen were mainly normal, while, window sizes in the toilets were small.

Majority of the residents had effected modifications in their houses by adding different components to existing ones. Exterior spaces such as terrace, balcony, porch and courtyard were also added to the house. Reasons for modifications by the residents were: privacy (76.6%), security (11.3%), comfort (7.2%) and aesthetic (4.9%). Neighbourhood characteristics showed that majority of the residents had open spaces such as playground, garden and park in their neighbourhood, although, the spaces were converted to recreation, social, political events as well as religious gathering purposes. The effects of these activities in the neighbourhood open spaces on residents’ sense of privacy across the housing estates, was high. Having examined the housing and neighbourhood characteristics in the study area, it is equally important to assess the residents’ perception of privacy.

4.3 Residents’ perception of privacy

4.3.1 Overall perception of privacy

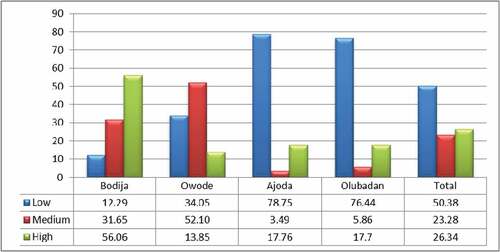

shows the result of the respondents’ ratings of the perception of privacy in the study area. About 34.22% of the respondents perceived privacy as low; 16.16% claimed it was very low; 23.42% felt that it was high; 2.92% indicated that it was very high; while 23.28% perceived it as medium. These clearly show that about half (50.38%) of the residents perceived privacy in the four housing estates as low or very low, while about a quarter (26.34%) viewed privacy as high or very high.

Table 7. Overall perception of privacy

4.3.2 Contributing variables to overall perception of privacy

shows 50 perception of privacy variables ranked in descending order of their contributions to overall perception of privacy. The 50 variables relate to: Visual privacy, Auditory privacy, Olfactory privacy, Personal privacy, Family privacy and Neighbourhood privacy. The closer the Perception of Privacy Index (PPI) score is to 5, the higher the residents’ disagreement to the perception of privacy. That is, the higher the PPI score of a variable, the lower the level of perception. On the whole, the absence of dedicated guest room for visitors contributed most to the low perception of visual privacy while separate dressing room within the bedroom contributed most to the high perception personal privacy.

Table 8. Contributing variables to overall perception of privacy

The results revealed that nineteen (19) variables had positive deviations above the mean index (2.03) in all the estates, suggesting that these variables contributed most to low perception of privacy. The nineteen (19) variables with high PPI scores and positive deviations above the aggregate mean (2.03) related to visual (8 variables), aural (3 variables) and olfactory privacy (2 variables); at family (5 variables) and neighbourhood (1 variable) levels. The eight variables that related to visual privacy were: dedicated guest room for visitors (3.46), outsiders seeing through toilet window (3.21), entrance doors directly facing opposite neighbour’s house (2.81), entrance doors placed away from the main street 2.35), bedrooms open directly to living room (2.27), separate rooms for boys and girls (2.24), kitchen interior visible to visitors (2.13) and kitchen exit door visible from outsiders 2.12). Three variables relate to aural privacy, namely: the noise from neighbour’s generator (2.12), sounds from neighbour’s bedroom (2.09) and clear conversation from neighbour’s house (2.03). Two variables are olfactory privacy related, namely: smell of cigarettes from neighbours’ balcony (3.20), and odour from neighbour’s toilet (2.09).

The five variables that relate to family privacy were: separate room for the guests (3.23), use of waiting room for visitors (3.04), visitors entering family lounge (2.43), visitors using family toilet (2.38) and sitting in the family garden (2.20). The only neighbourhood privacy variable was: keeping a distance in relationship with neighbours (2.05). Findings on the family privacy level can be explained within the context of the Yoruba being the predominant group in the study area with 89.4% (see Table 4.1), and their tendency for household interactions.

The ten variables with the least PPI scores and negative deviations below the mean index (2.03) included eight (8) variables relating to personal privacy, namely: window not facing neighbour’s house directly (1.66), lobby before entering bedroom (1.63), not allowing outsiders into bedroom (1.63), having separate bedroom (1.62), toilet located within bedroom (1.61), children having separate bedrooms (1.50), sleeping in a quiet room (1.45) and separate dressing room within bedroom (1.41). These variables suggest a high level of perception of privacy.

From the foregoing analyses, dedicated guest room for visitors was the highest ranked variable (PPI of 3.46), while separate dressing room within bedroom was the least ranked (PPI of 1.41) variable. The result of ‘dedicated guest room for visitors’ can be explained within the context of earlier finding that majority of the residents had two (2) or three (3) bedrooms, which perhaps made it not adequate for them to set aside dedicated guest room for visitors.

Similar explanation can be given to ‘separate room for the guests’, which was ranked second by the residents. The large proportion of respondents who had modified their houses by increasing the number of bedrooms to four (4) or five (5) is perhaps due to the need to provide dedicated guest room for visitors. This confirmed previous finding that 87.3% of the respondents required the dedicated guest room for visitors. This result contradicts earlier finding by Aduwo et al. (Citation2013) that residents do not have a need for guest room as it is a luxury which they can do without in their housing units.

It is also to be noted that while the variable with the highest PPI score of 3.46 and highest contribution to low perception of privacy (dedicated guestroom for visitors) is a Visual privacy variable, that with the lowest PPI and the least contribution is an aural privacy variable (hearing clear conversation from neighbour’s house). This indicates that aural privacy in the four estates was moderate as residents could not hear clear conversation from neighbour’s house, unlike visual privacy which had the highest contribution to low perception of privacy.

4.3.3 Perception of privacy types

Disaggregating the data in , the levels of perception of the three privacy types were also examined in order to identify how the respondents perceived the different privacy types: visual, aural and olfactory. This was important in analysing which variables contributed most and least to overall perception of privacy.

Table 9. Overall perception of visual privacy variables

Perception of visual privacy

The results in reveal that more than half (53.85%) of the respondents perceived visual privacy as low, 21.03% felt it was very low and 1.45% indicated medium. However, 20.03% and 3.64% claimed that the visual privacy was high and very high, respectively. Therefore, a majority (74.88%) of the respondents perceived visual privacy in the four housing estates as low.

Perception of aural privacy

Regarding the perception of aural privacy, the results in reveal that 1.92% and 19.82 of the respondents perceived Aural Privacy Variables as low and very low, respectively, while 6.23% and 1.91% of the respondents perceived aural privacy was high and very high, respectively. The majority (70.12%) of respondents perceived aural privacy as medium or moderate.

Table 10. Overall perception of aural privacy variables

Perception of olfactory privacy

The respondents generally perceived the olfactory privacy provided in the housing estates as moderate. This is confirmed by the results in which shows that 32.24% and 9.91% of the respondents perceived the olfactory privacy as low and very low, respectively; 12.77%, and 2.8% felt that the level of olfactory privacy variables was high and very high, respectively; while 42.27% perceived that olfactory privacy was moderate.

Table 11. Overall perception of olfactory privacy variables

4.3.4 Perception of privacy levels

The perception to the three privacy levels variables was also examined, in order to identify how the respondents rate their perception of personal, family and neighbourhood privacy, and which variables contributed most and least to overall perception of privacy.

Perception of personal privacy

The results in show that almost half (49.29%) of the respondents perceived that the personal privacy variables highly, while 45.66% indicated that they were very high. Very small proportions (2.96%, 1.61% and 0.62%) indicated low, medium and very low, respectively. These clearly reveal that an overwhelming majority (94.95%) of the residents perceived personal privacy in the four housing estates as high.

Table 12. Overall perception of personal privacy variables

Perception of family privacy

Family privacy in public housing estates is another key component of privacy; therefore, an assessment of the perception of family privacy variables was done to better understand the extent the ten (10) variables contributed to overall perception of privacy. The results in show that a little less than half (47.40%) of the respondents perceived family privacy variables in the estates were low, while 21.40% indicated high. Very small proportions (2.50% and 1.40%) indicated very low and very high, respectively, while 27.31% felt that the family privacy variables in the housing estates were moderate.

Table 13. Overall perception of family privacy variables

The findings confirmed that separate guestrooms were not included in the original design of these estates; hence the visitors and residents were sharing the same habitable spaces which could have affected family privacy adversely.

Perception of neighbourhood privacy

With regards to the perception of neighbourhood privacy variables, the results in show that 59.43% of the respondents perceived neighbourhood privacy as high, and 33.73% as very high, while 4.67% of the respondents indicated low neighbourhood privacy. Therefore, a substantial proportion (93.16%) of the respondents perceived the level of neighbourhood privacy as high while 5.17% were of the opinion that it was low.

Table 14. Overall perception of neighbourhood privacy variables

The results in show that more than half (56.06%) of the respondents in Bodija estate perceived privacy as high, whereas the majority (78.75% and 76.44%) of the respondents in the Ajoda and Olubadan estates, respectively, perceived privacy as low. The highest proportion of respondents in Owode estate however perceived privacy as moderate (52.10%). In summary, residents perceived privacy as high in Bodija estate, moderate in Owode estate and low in Ajoda and Olubadan estates.

The assessment of residents’ perception of privacy shows that a good majority perceived the visual privacy as very low, while most perceived personal privacy as high. A sizeable proportion of the respondents considered of aural privacy and olfactory privacy to be moderate while family privacy was perceived low.

4.4 Residents’ privacy regulating mechanisms

4.4.1 Overall privacy regulating mechanism

Table 4.12 reveals that 55.71% of respondents agreed and 36.29% strongly agreed to the use of privacy regulating mechanisms. This represents in summation, 92.00% of the respondents. This confirms the earlier finding that majority of the residents perceived privacy level in the study are as low (). This may have influenced their responses to the privacy regulating mechanisms adopted in the estates.

Table 15. Overall privacy regulating mechanisms

This may be considered to be in tandem with the finding in Ahmad and Zaiton (Citation2010), which indicated that residents of Malay Urban Dwellers in Selangor were strongly agreed with their overall housing modification, and in Aduwo (Citation2011) suggesting that residents in low-income public housing estates in Lagos were also agreed with the housing modification.

4.4.2 Contribution of privacy variables to privacy regulating mechanism

As presented in , responses were elicited to twenty eight (28) statements relating to privacy regulating mechanisms identified in literature. Respondents were requested to indicate their level of agreement or disagreement, on a Likert scale. The mean index computed for the study area as a whole was 1.82. The closer the Privacy Regulating Index (PRI) is to 5, the higher the residents’ agreement to the statement that describes the privacy regulating mechanism.

Table 16. Contributing variables to overall privacy regulating mechanism

Twelve (12) residents’ privacy regulating mechanism variables had PRI and positive deviations above the mean index, the highest being ‘addition of bedrooms (PRI = 2.21), followed by insulation of walls against unwanted noise’ (2.15), ‘adjustment of initial layout plan of living room’ (PRI = 2.02) and ‘conversion of spaces to other uses’ (PRI = 2.01).

Conversely, the five (5) least adopted regulating mechanisms included: ‘blocking of doors for maximum privacy’ (PRI = 1.69), ‘hanging of curtains on the windows’ (PRI = 1.69), ‘regulation of interactions with neighbours’ (PRI = 1.67), ‘scrutinizing activities on time’ (PRI = 1.63) and ‘not looking into neighbour’s house’ (PRI = 1.56). The results show that privacy regulating mechanisms were not restricted to environmental mechanisms but also behavioural means such as verbal or non-verbal behaviour.

The results on show the comparative contributions of each of the 28 privacy regulating variables arranged in descending order of their PRI. The variables comprise: eight (8) personal space variables; fourteen (14) territorial behaviour variables; two (2) verbal behaviour variables; and four (4) non-verbal behaviour variables.

From the foregoing analyses, ‘addition of bedrooms’ was the highest ranked variable (PRI = 2.21) residents agreed with, while ‘not looking into neighbour’s house’ was the least ranked variable (PPI = 1.56). The high ranking of ‘addition of bedrooms’ can be explained within the context of earlier finding that majority of the residents required spaces such as dedicated guest rooms, which were not included in the original design of the housing units. A substantial proportion of residents had therefore modified their houses by increasing the number of bedrooms to cater for their households and visitors. It would be recalled from Table 4.16, that among those who had modified their housing units, the largest proportion of 23% were those who had added more rooms. This was also confirmed by the responses from the key informants in the interview conducted:

We added more bedrooms because the available rooms were not adequateat all[Ajoda New Town]

We added more rooms at our backyard in order to have a little sense ofprivacy [Bodija estate]

Interestingly, the contributing variables to Overall Perception of Privacy () appear to be similar to the contributing variables to Privacy Regulating Mechanisms as shown in Table 4.20. While ‘dedicated guestroom for visitors’ and ‘separate room for guests’ were the two highest ranked variables in the former, ‘addition of bedrooms’ is the highest ranked variable in the latter. The inference is that the most common mechanism by which residents regulate their need for privacy is by means of a Personal Space mechanism – adding bedrooms. This supports the findings in Aduwo (Citation2011), which indicated that addition of more bedrooms was the main mechanism of housing transformation in selected low-income public housing estates in Lagos.

The variable that is next in rank to ‘addition of bedrooms’ is the territorial behaviour of ‘Insulation of walls against unwanted noise’ (PRI = 2.15). This is followed by two other Personal Space mechanisms: ‘adjustment of initial layout plan of living room’ (PRI = 2.02) and ‘Conversion of spaces to other uses’ (PRI = 2.01). In general, the Personal Space and Territorial behaviour types of privacy regulation mechanisms were more predominant than Verbal behaviour or Non-verbal behaviour.

4.4.3 Privacy regulating mechanism across the four housing estates

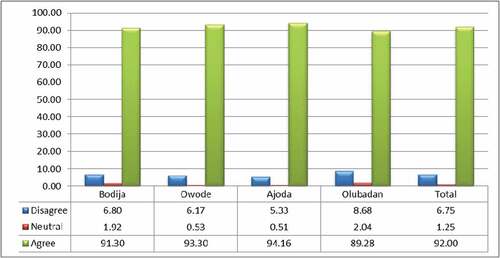

Analysis of the results in reveals that 91.30%, 93.30%, 94.16% and 89.28% of the respondents in Bodija, Owode, Ajoda and Olubadan estates, respectively, agreed with their privacy regulating mechanisms. The largest numbers of respondents who agreed with their privacy regulating mechanisms were in Ajoda, the least proportion resided in Olubadan estate.

This further confirms the earlier finding that respondents in Ajoda housing estate, more than any other, perceived the level of privacy as low (see, ). These results tend to suggest that people are more agreed with privacy regulating mechanisms when they perceived the level of privacy as low and they had no input into the design and construction of their housing. Therefore, public housing policy formulation, programmes, design and implementation should encourage the involvement of residents in public housing design.

5.0 Conclusion

The study concluded that there were significant variations in the socio-economic and cultural characteristics of residents across the public housing estates in Ibadan. The housing estates were inhabited by residents with different ages, marital status, religion, occupational status and level of education.The study established that perception of privacy was generally low across the housing estates, except for Bodija estate. Every one of the types and levels of privacy factors contributed generously to low perception of privacy while only personal privacy variables contributed the most to high perception of privacy in the four estates. Nevertheless, the majority of the residents who strongly disagreed with the levels of privacy in the estates had engaged more in environmental regulating mechanisms than behavioural mechanisms. This investigation has hence given information on what ought to be considered in planning future public housing estates dependent on residents’ perception of privacy. Sustainable design and privacy standards that can place residents into consideration and advance privacy of the housing units and neighbourhoods ought to be incorporated to the plan of public housing estates and in metropolitan design overall.

Government and the significant housing experts should involve residents in the design and execution of projects that influence their lives, particularly the development and improvement of public housing estates. Public housing professionals ought to consider cultural and social requirements of the residents, including privacy, which has been established to be a vital need of residents.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Abdul Rahim, Z. (2015). The influence of culture and religion on visual privacy. Procedia Social and Behavioural Sciences, 170, 537–544. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2015.01.055

- Abdul Rahim, Z. (2018). The role of culture and religion on conception and regulation of visual privacy. Asian Journal of Behavioural Studies (Ajbes), 3(11), 169–177. https://doi.org/10.21834/ajbes.v3i11.112

- Aduwo, B. E. (2011). Housing transformation and its impact of neighbourhoods in selected low-income public housing estates in Lagos, Nigeria. PhD thesis. Covenant University

- Aduwo, B. E., Ibem, O. E., & Opoko, P. A. (2013). Residents’ transformation of dwelling units in public housing estates in lagos, Nigeria. Implications for Policy and Practice International Journal of Education and Research, 4(1), 182.

- Ahmad, H. H., & Zaiton, A. R. (2008). The influence of privacy regulation on urban malay families living in terrace housing. Archnet-IJAR, International Journal of Architectural Research, 2(2), 94–102.

- Ahmad, H. H., & Zaiton, A. R. (2010). Privacy and housing modifications among malay urban dwellers in Selangor. Pertanika J. Soc. Sci. & Hum, 18(2), 259–269.

- Ahsen, O., & Gulcin, P. G. (2005). Space use, dwelling layout and housing quality: An example of low cost housing in Istanbul. Ashgate publishing Limited.

- Al-Hamoud, M. (2009). Privacy control as a function of personal space, in single-family homes in Jordan. Journal of Design and Built Environment, 5, 31–48.

- Al-Thahab, A., Mushatat, S., & Abdelmonem, M. G. (2014). Between tradition and modernity: determining spatial systems of privacy in domestic architecture of contemporary Iraq International Journal of Architectural Research, ArchNet-IJAR. 8(3), 238–250. doi:10.26687/archnet-ijar.v8i3.396.

- Aliens, S. (2011). Residential group size, social interaction and crowding. Environmental Behaviour, 5, 170–192.

- Alitajer, S., & Nojoumi, G. M. (2016). Privacy at home: Analysis of behavioural patterns in the spatial configuration of traditional and modern houses in the city of Hamedan based on the notion of space syntax. Frontiers of Architectural Research, 5(3), 341–352. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foar.2016.02.003

- AlKhateeb, M. (2015): An investigation into the concept of privacy in contemporary Saudi houses from a female perspective: A design tool, A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of Bournemouth University for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. (Bournemouth University). http://eprints.bournemouth.ac.uk/25016

- Altman, I. (1975). The environment and social behaviour: privacy, personal space, territory, crowding. Brooks/Cole Publishing Company.

- Altman, L. (1976). Privacy: A conceptual analysis. Environment and Behaviour, 8(1), 7–9. https://doi.org/10.1177/001391657600800102

- Altman, I. (1977). Privacy regulation: culturally universal or culturally specific? Journal of Social Issues, 33(33), 66–84. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4560.1977.tb01883.x

- Altman, I., & Chemers, M. (1980). Culture and environment. Cambridge University Press.

- Altman, I. (2013a). Psychological demand of the built environment, privacy, personal space and territory in architecture. International Journal of Psychology and Behavioural Science, 3(4), 109–113.

- Anthony, D., Campos-Castillo, C., & Horne, C. (2017). Towards A sociology ofPrivacy. Annual Review of Sociology, 43(1), 249–269. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-soc-060116-053643

- Bekci, B., & Özbilen, A. (2012). A research on the application of a harmony between personal space and architectural space into a case study like park. KastamonuÜniversitesiOrmanFakültesiDergisi Journal of Forestry Faculty, 12(2), 329–338.

- Bekleyen, A., & Dalkiliç, N. (2011). The influence of climate and privacy on indigenous courtyard houses in Diyarbaki{dotless}r, Turkey. Scientific Research and Essays, 6(4), 908–922 ISSN:1992-2248 .

- Daneshpour, A., Embi, M. R., & Torabi, M. (2012): Privacy in housing design: effective variables. In: 2th International Conference-Workshop on Sustainable architecture andUrban Design (ICWSAUD2012). Malaysia: UniversitiSains.

- Djebarni, R., & Al-Abed, A. (2000). Satisfaction level with nieghbourhood in low-income public housing in Yemen. Journal of Construction Management, 18(4), 230–242.

- Edwards, C. (2010). Interior design: A critical introduction (Berg Publishers)ISBN-10:1847883125 .

- Ekhaese, E. N., & Adeboye, A. B. (2014). Go-ahead element of domestic architecture: Socio- economic and cultural characteristics of the residents in Benin. IMPACT: International Journal of Research in Humanities, Arts and Literature (IMPACT: IJRHAL) (E): 2321-8878; (P): 2347-4564, 2(5), 73–88.

- Eni, C. M. (2014): Evaluation of Occupants’ Perception of Public Housing Estates in Awka and Onitsha, Anambra State, Nigeria, An Unpublished Ph.D. Dissertation Department of Environmental Management, Faculty of Environmental Sciences, NnamdiAzikiwe University.

- Fahey, T. (1995). Family and privacy: Conceptual and empirical reflections. Journal of the British Sociological Association, 29(4), 687.

- Gavison, R. (1980). Privacy and the limits of law. The Yale Law Journal, 89(3), 421–471. https://doi.org/10.2307/795891

- Griffin, E. (2006). Proxemics theory by edward hall. In A first look at communication theory (6th Ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill.

- Hall, E. T. (1990). The hidden dimension/Edward T. Hall. Anchor books 1969. Anchor Books: Doubleday & Company.

- Hashim, A. H. (2003). Residential satisfaction and social integration in public low cost housing in Malaysia. Pertanika Journal of Social Science and Humanity, 11(1), 1–10.

- Heydaripour, O., Behmaneshnia, F., Talebian, E., & Shahi, P. H. (2017). A Survey on privacy of residential life in contemporary apartments in Iran. International Journal of Science Studies, 5(3), 254–263.

- Hosseini, S. R., Ethegad, A. N., Guardiola, E. U., & Aira, A. A. (2015). Iranian courtyard housing: The role of social and cultural patterns to reach the spatial formation in the light of an accentuated privacy. Architecture, City and Environment, 10(29), 11–30.

- Ibem, E. O. (2011): Evaluation of public housing in Ogun State, Nigeria, PhD Thesis Submitted to the School of Postgraduate Studies, Covenant University.

- Ibem, E. O., & Aduwo, E. B. (2013). Assessment of residential satisfaction in public housing in Ogun State, Nigeria. Habitat International, 40, 163–175. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.habitatint.2013.04.001

- Ilesanmi, A. O. (2005): An Evaluation of Selected Public Housing Schemes of Lagos State Development and Property Corporation, Lagos Nigeria. Unpublished PhD Thesis Submitted to the School of Postgraduate Studies, ObafemiAwolowo University (OAU) Ile-Ife.

- Ilesanmi, A. O. (2010). Post-occupancy evaluation and residents’ satisfaction with public housing in Lagos, Nigeria. Journal of Building Appraisal, 6(2), 153–169. https://doi.org/10.1057/jba.2010.20

- Jiboye, A. D. (2009). Evaluating tenant’s satisfaction with public housing in Lagos, Nigeria. Town Planning and Architecture, 33(4), 239–247. https://doi.org/10.3846/13921630.2009.33.239-247

- Kennedy, R., Buys, L., & Miller, E. (2015). Residents’ experiences of privacy and comfort in Multi-Storey apartment dwellings in subtropical Brisbane. Journal ofSustainability, 7(6), 7741–7761. https://doi.org/10.3390/su7067741

- Kiyak, H. A., & A. (1978). Multidimensional perspective on privacy preferences or institutionalized elderly, in EDRA 9: New directions in environmental design research. (W. E. Rogers & W. H. Ittelson, Editors.). Environmental Design Research Association.

- Liu, W. T. (2016). Survey of the critical issue of the public housing privacy to influence on residents’ living condition in Hong Kong. HBRC Journal, 11(5), 1–11.

- Margulis, S. T. (2003). Privacy as a social issue and behavioural concept. Journal of Social Issues, 59(2), 243–261. https://doi.org/10.1111/1540-4560.00063

- Memarian, G. H., HashemiToghroljerdi, S. M., & Ranjbar-Kermani, A. M. (2011). Privacy of house in Islamic culture: A comparative study of pattern of privacy in houses in Kerman. International Journal of Architecture Engineering Urban Planning, 21(2), 69–77.

- Mohit, M. A., Ibrahim, M., & Rashid, Y. R. (2010). Assessment of residential satisfaction in newly designed public low-Cost housing in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. Habitat International, 34(1), 18–27. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.habitatint.2009.04.002

- Namazian, A., & Mehdipour, A. (2013). Psychological demands of the built environment, privacy, personal space and territory in architecture. International Journal of Psychology and Behavioural Sciences, 3(4), 109–113.

- Omid, H., Farzad, B., Ehsan, T., & Parisa, (2017): A survey on privacy of residential life in contemporary apartments in Iran

- Othman, Z., Aird, R., & Buys, L. (2015). Privacy, modesty, hospitality, and the design of Muslim homes: A literature review. Frontiers of Architectural Research, 4(1), 12–23. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foar.2014.12.001

- Pedersen, D. M., & Frances, S. Regional differences in privacy preferences. (1990). Psychological Reports, 66(2), 731–736. Pedersen 1997. https://doi.org/10.2466/pr0.1990.66.3.731

- Ramezani, S., & Hamidi, S. (2010). Privacy and social interaction in traditional towns to contemporary Urban design in Iran. American Journal of Engineering and AppliedSciences, 3(3), 501. https://doi.org/10.3844/ajeassp.2010.501.508

- Rapoport, A. (1969). House Form and Culture. Prentice Hall.

- Rapoport, A. (2005). Culture, Architecture, and Design. Locke Science Publishing Company.

- Razali, N. H. N., & Talib, A. (2013). Aspects of privacy in Muslim malay traditional dwelling interiors in Melaka. Procedia Social and Behavioural Sciences, 105, 644–654. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2013.11.067

- Rustemli, A., & Kokdemir, D. (1993). Privacy Dimensions and Preferences among Turkish Students. The Journal of Social Psychology, 133(6), 807–814. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224545.1993.9713942

- Salama, A. M., & Alshuwaikhat, H. M. (2006). A trans-disciplinary approach for a comprehensive understanding of sustainable affordable housing. Gber, 5(3), 35–50.

- Sarikakis, K., & Winter, L. (2017). Social media users’ legal consciousness about privacy. Social Media + Society.

- Shabani, M. M., Tahir, M. M., Shabankareh, H., Arjandi, H., & Mazaheri, F. (2011). Relation of cultural and social attributes in dwelling: Responding to privacy in Iranian traditional house. Journal of Social Sciences and Humanities, 6(2), 273–287.

- Shahab, A., Abasalt, A., & Rabori, N. K. (2015). Study of physical elements affecting spatial hierarchy in the residential complex, to enhance residents’ satisfaction, increase sense of privacy and social interaction.bulletin of environment. Pharmacology and Life Sciences Bull.Env.Pharmacol. Life Sci, 4, 50–62.

- Sobh, R., & Belk, R. (2011). Domains of privacy and hospitality in Arab Gulf homes. Journal of Islamic Marketing, 2(2), 125–137. https://doi.org/10.1108/17590831111139848

- Tao, W. T. (2018). Survey of the critical issue of the public housing privacy to influence on residents’ living condition in Hong Kong. HBRC Journal, 14(3), 288–293. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hbrcj.2016.11.005

- Tomah, A. N. (2011). Visual privacy recognition in residential areas through amendment of building regulation. Proceedings of the Institution of Civil Engineers (ICE), Urban Design and Planning.

- Tomori, M. A. (2012). Transformation of ibadan built environment through restoration of Urban infrastructure and efficient service delivery by: Ceo/Md. Macos Urban Management Consultant. Available at: Macosconsultancy.Com.

- Trepte, S., & Reinecke, L. (2011). Privacy Perspectives on privacy and self-disclosure in the social web. Springer.

- Walden, T., Nelson, P. A., & Smith, D. E. (2011). Crowding, privacy and coping. Environ. Behaviour, 13(2), 205–224. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013916581132005

- Wills, M. (1963). Overlooking. The Architects’ Journal, 23.

- Witte, N. (2003): Privacy: Architecture in Support of Privacy Regulation, School of Architecture of Interior Design of the College of Design, Architecture, Art, and Planning, University of Cincinnati, Architectural Thesis.

- Yeun, B., Yeh, A., Stephen, J. A., Earl, G., Ting, J., & Kwee, L. K. (2006). High-rise living Singapore public housing. Urban Studies, 42(3), 583–600. https://doi.org/10.1080/00420980500533133

- Zaiton, A. (2018). Role of culture and religion on conception and regulation of visual privacy. Asian Journal of Behaviour Studies, 2(11), 169–177.