ABSTRACT

Extensive research has focused on the relationship between culture and creativity. However, related studies typically adopt national cultural values, set countries as independent variables to explore the relationship between culture and individuals’ creativity, or have inconsistent conclusions. Therefore, this study attempted to explore this relationship at the individual level in design processes from a phenomenological perspective, based on two design tasks carried out by 27 students at a university in China. The results showed a positive association between pleasure and long-term versus short-term orientation of individual cultural values in the two creative methods – 6-3-5 and collaborative sketching (C-sketch) – which were statistically significant. However, the correlation between enlightenment and long-term versus short-term orientation only existed in the 6-3-5 method. Based on the analysis, we found that an individual’s educational level affected their self-evaluation in the experience of creativity, and the 6-3-5 method was more favorable than the C-sketch method for the participants. Moreover, we developed a visualization framework and explained the relationship between culture and creativity based on the componential theory of creativity and Hofstede’s culture theory. Furthermore, the study might serve as a groundwork for further examination of the relationship between individuals’ culture and their experience of creativity.

1. Introduction

Creativity is regarded as a unique ability and need among human beings (Albert, Citation1990), which can be affected by many factors (Amabile, Citation2011; Jablokow et al., Citation2020; Tan, Citation2016; Wrigley, Citation2017), such as an external source (Rhodes, Citation1961; Runco & Jaeger, Citation2012), including culture (Glaveanu et al., Citation2019; Hofstede et al., Citation2010; Rhodes, Citation1961). For example, Runco and Jaeger (Citation2012) reviewed the early studies related to the definition of creativity. They affirmed and endorsed Stein’s (1953) work and described how creativity is affected by individuals’ perception of the environment as ‘a traitx state interaction and was clearly apparent in the early definition of press (one of the four strands of research identified by Rhodes, Citation1961) ’ (Runco & Jaeger, Citation2012, p. 95). Moreover, design can be viewed as a process of composing a desirable figure toward the future, with design classifications such as drawing, problem solving, and idea pursuit (Taura & Nagai, Citation2010). On this basis, and depending on the specifics, the design can be aware or be responsive to many aspects, such as sustainability, the problem at hand or its formulation, and this process requires design creativity. Design creativity is related to the interaction between design, creativity, and human beings (Taura & Nagai, Citation2010, p. 1) and is affected by culture (Hong et al., Citation2018; Saad et al., Citation2015). The role of design creativity also differs depending on cultures based in different geographical regions (Lubart, Citation1999). For example, individuals from the East focus more on the appropriateness of creative results, while individuals based in the West fixate more on their novelty (Lubart, Citation1999; Niu & Sternberg, Citation2001).

Researchers explored the relationship between culture and creativity based on various independent variables, such as the participants’ nationality (Niu & Sternberg, Citation2001), national cultural values (Tsegaye et al., Citation2019) or specific cultural values (Hong et al., Citation2018; Saad et al., Citation2015). However, there are several limitations regarding the study exploring the relationship between culture and creativity. First, setting country as the independent variable is concerning because there is no way to know whether the findings genuinely reflect the culture or just some characteristics of the chosen country (Xie & Paik, Citation2019). Second, it is inappropriate to adopt national cultural values when the study explores the relationship between culture and creativity by measuring individuals’ and groups’ creativity that is irrelevant to the nation and society (Yoo & Shin, Citation2017). Thirdly, exploring the relationship between culture and creativity by focusing on a few single cultural values is questionable (Yong et al., Citation2020). Yong et al. (Citation2020) proposed that bundles of cultural dimensions (including power distance, uncertainty avoidance, masculinity-femininity, and individualism-collectivism) affect creativity by influencing its components, such as creativity-relevant skills and task motivation. They proposed that when studying creativity and culture across countries, it is better to have a more comprehensive view of culture (i.e. cultural bundles) rather than look at each dimension separately. For example, suppose a study only focuses on the influence of individualism-collectivism on domain-relevant skills of creativity. In that case, the researchers may conclude that domain-relevant skills are generally encouraged in China (an example of a higher collectivism country). However, suppose they were to research the effects of power distance on domain-relevant skills of creativity. In that case, researchers may surmise that domain-relevant skills are discouraged in China (a higher power-distance country), which contradicts the first example (Yong et al., Citation2020).

Inspired by the mentioned research (Xie & Paik, Citation2019; Yong et al., Citation2020; Yoo & Shin, Citation2017), this study attempts to understand the relationships between individual culture and creativity by measuring individuals’ cultural values before the experiment and measuring their experience of creativity after completing the design tasks. We begin this by discussing the concepts of creativity and culture. This is followed by our study that reports on the influence of culture on creativity to help get a better understanding of the relationship between them.

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. Creativity Definition and Measurement

Creativity is multidimensional, which poses a challenge for researchers attempting to propose a single method of defining and measuring it (Cropley, Citation2000; Furnham et al., Citation2008; Kaufman et al., Citation2008). Therefore, we explained the related studies (i.e. the definition and measurement of creativity) to understand creativity comprehensively.

2.1.1. Creativity Definition

The literature defines creativity from various perspectives, usually using at least one of these four perspectives: person, process, product, and press (Kampylis & Valtanen, Citation2010; Said-Metwaly et al., Citation2017). Focusing on the process, Torrance (Citation1977) defined creativity as the process of identifying problems; generating, testing, and modifying ideas of hypotheses; and communicating the results. Other researchers defined creativity as a form of problem-solving and identified two types of cognitive operations – divergent and convergent production (Guilford, Citation2017). Creativity has also been defined based on products, where ideas or outcomes are produced as both novel and appropriate to some goal or open-ended tasks (Sternberg, Citation1999). There are, in fact, more than 100 different definitions of creativity (Said-Metwaly et al., Citation2017).

Nevertheless, for the purpose of this paper, we follow the widely used definition that includes all four aspects (person, process, product, and press). Rhodes coined this and referred to ‘a noun naming the phenomenon in which a person communicates a new concept (which is the product). Mental activity (or mental process) is implicit in the definition, and of course no one could conceive of a person living or operating in a vacuum, so the term press is also implicit’ (Rhodes, Citation1961, p. 305).

2.1.2. Creativity Measurement

Measuring creativity is also a challenge (Baer & McKool, Citation2009; Batey et al., Citation2010; Kaufman et al., Citation2008), and researchers have developed a variety of measurements (Borgianni et al., Citation2013; Dean et al., Citation2006; Georgiev & Georgiev, Citation2018; B. A. Nelson et al., Citation2009; B. Nelson & Rawlings, Citation2009; Torrance, Citation1977). For example, measuring creativity through the process, such as divergent thinking tests. Although the divergent thinking test is a widely used measurement relating to creative processes (Kaufman et al., Citation2007) and the reliability of it has been obtained (Torrance & Haensly, Citation2003), there is still insufficient validity of its constructs (Said-Metwaly et al., Citation2017). Other research measures creativity in the context of design (i.e. design creativity) by evaluating products, for example, analyzing the appropriateness and novelty of creative output (Koronis et al., Citation2019), or evaluating quality, novelty and variety of ideas (Shah et al., Citation2001), or evaluating original, usable, feasible, aesthetic and elaboration of industrial design solutions (Georgiev & Casakin, Citation2019). Although various metrices to measure design creativity based on researchers’ research aims and the types of outputs (Said-Metwaly et al., Citation2017), one popular measurement is the consensual assessment technique (CAT), suggested by Amabile (Citation1982). It evaluates generated outcomes with two independent domain-related experts and examines them using inter-rater reliability. However, concerns were raised regarding the reliability of this method, such as the influence of certain factors (e.g. the number of tasks being rated (Kaufman et al., Citation2007; Lee et al., Citation2005)) and differences in personality, personal preferences, or cultural background might impact judgment when evaluating creativity (Niu & Sternberg, Citation2001; Said-Metwaly et al., Citation2017). Because the quantitative method is the primary method of measuring creativity (B. Nelson & Rawlings, Citation2009), and their study has limitations (Said-Metwaly et al., Citation2017), as explained before, we selected a qualitative method to evaluate the experience of creativity through a questionnaire. Nelson and Rawlings (Citation2009) developed a questionnaire to help fully understand the phenomenology of creativity during the creative process. They stated that the questionnaire is qualitative and would help measure creativity from a phenomenological aspect, focusing on how creative processes are experienced (named experience of creativity) rather than evaluating design creativity or creative outputs, or divergent thinking, as we explained previously. Phenomenology ‘is the search for “essences” that cannot be revealed by ordinary observation. Phenomenology is the science of essential structures of consciousness or experience’ (Sanders, Citation1982, p. 354). Another reason for choosing the questionnaire to measure individuals’ experiences of creativity is the definition of creativity that we cited as a phenomenon; thus, we attempted to explore the relationship between individuals’ culture and their experience of creativity (i.e. personal experience of creativity during the idea-generation process) from a phenomenological perspective for consistency.

2.2. Culture Values based on Hofstede’s Theory

Culture is the collective programming of the mind that distinguishes groups of people from other groups (Hofstede, Citation1980). In addition, culture comprises thought processes, feelings, and response methods and behaviors that are predominantly obtained and spread through symbols. The fundamental core of this concept is tradition (e.g. behavior and thinking that are historically derived and selected) – the composition of ideas, specifically their attached value (Kluckhohn, Citation1951). Following prior research, we conceptualize culture as the transmission and creation of content and patterns of values, ideas, and other factors that can shape and mold individual cognitive and behavioral tendencies (Kroeber & Parsons, Citation1958). Cultural values were identified by Hofstede (Citation1980), whose study conducted with the computer company IBM from 1967 to 1973 collected more than 11,600 responses from 72 countries and classified them into four categories: power distance index, uncertainty avoidance index, masculinity-femininity index, and individualism-collectivism index. Later, Hofstede (Citation2001) added one more category to these national cultural values: the long-term versus short-term orientation index.

Although Hofstede’s national cultural values (Hofstede, Citation2001) are a widely used measurement in researching culture, it is not appropriate when the study is irrelevant to national or society research (Yoo & Shin, Citation2017) because of a few reasons. Culture is not inherited by birth but affected by many factors, changing over time (Iorgulescu, Citation2014). However, the values pertaining to national culture measured by Hofstede in the 1960s and 1970s have not been updated (Yoo & Shin, Citation2017). Moreover, the increased heterogeneity and mobility among many current national populations and superior global communication channels mean that assigning national-level cultural scores to each member of society is less meaningful (Yoo & Shin, Citation2017). There is substantial cultural diversity among members in the modern world; therefore, it is inappropriate to adopt national cultural values when the research aim is not related to the national society (Yoo et al., Citation2011), such as creativity as we are viewing it in this study. Individual cultural values refer to cultural dimensions at the individual level, reflecting individual attitudes and behaviors toward individual-level cultural orientations (Yoo et al., Citation2011). They have the same level of importance as collective values, and it is more appropriate to adopt individual cultural values when studies deal with dimensions that are irrelevant to research of nation and society. To this end, numerous scales have been developed to evaluate individual cultural values (Bearden, Citation2006; Sharma, Citation2010; Triandis, Citation2018; Yoo et al., Citation2011). For example, Sharma (Citation2010) devised a long-term orientation scale (a two-factor, eight-item scale) at the individual level, based on more than 2,000 respondents across four countries. This evaluation method showed acceptable validity when being applied to the investigation of individual differences in long-term orientation within and across cultures. Yoo et al. (Citation2011) focused more on each cultural dimension. They developed a 26-item, five-dimensional individual cultural values scale (CVSCALE) based on 433 participants in South Korea and the United States, which we adopted for our study with satisfactory reliability and validity after the low loadings had been removed.

2.3. Influence of Culture on Creativity

Culture has a profound influence on creativity. It forms the growth environment, but it also shapes people and the creation and functions of products (Ludwig, Citation1992). This implies that people with different cultural values have differing personal feelings, behaviors, and methods of collaboration during the creative process (Détienne et al., Citation2017; Wodehouse & Maclachlan, Citation2014; Wodehouse et al., Citation2011). We reviewed studies on the influence of each cultural value of interest on research collaborative layout creativity and summarized the key findings below.

2.3.1. Power Distance

Power distance (PD), is ‘the degree of inequality in power between a less power Individual (I) and a more powerful Other (O)’ (Mulder, Citation2012, p. 90). Individuals with a higher PD value are conscious of the hierarchy in their community. They prefer to comply with instructions and guidance from their leaders, leading to less proactive behavior. However, individuals with a lower PD value tend to ignore hierarchy, think of each other as equal, prefer to communicate, and have less inclination to follow rules they disagree with. This encourages them to take the initiative in a task or event (Tsegaye et al., Citation2020). During the creative process, individuals with higher PD cannot take the initiative because they are too concerned about their supervisors’ responses. They are more likely to follow the rules as per their supervisor’s expectations rather than deviate from them (Shane, Citation1995). A study compared two groups of students from a country with a higher PD and one with a lower PD country and discussed the influence of culture on creativity by measuring the novelty, fluency, and elaboration of ideas generated under three conditions: working alone, working with peers, and working with a supervisor (Nouri et al., Citation2015). The results showed that students from the higher-PD country generated fewer novel ideas in working with the supervisor than in working alone and with their peers, which demonstrated that PD negatively affected creativity.

2.3.2. Uncertainty Avoidance

Uncertainty avoidance (UA), refers to the degree of anxiety and risk aversion that people feel during ambiguous situations (Hofstede, Citation1980). Although some societies accept that life is uncertain and uncontrollable, others consider uncertainty a threat (Hofstede, Citation1980). This affects individuals’ actions, communication, and motivation. Their UA value impacts exploratory behavior, which either encourages or hinders individuals from generating ideas in creativity (Erez & Nouri, Citation2010). Individuals in societies with higher UA tend to avoid risk or ambiguity. Conversely, individuals in societies with lower UA would be encouraged to be risk-takers, as they accept failure as a part of the high-risk process (Gupta et al., Citation2019), which has a positive effect on creativity (Albar & Southcott, Citation2021; Wan et al., Citation2021). For example, Adair and Xiong (Citation2018) conducted two experiments exploring UA’s influence on emphasizing novelty and usefulness in creativity. The results showed that individuals with a higher UA were less likely to emphasize novelty. However, other studies have arrived at different results, that there is no correlation between UA and national creativity (Rinne et al., Citation2012). These findings mean further exploration is needed to confirm the relationship between UA and creativity.

2.3.3. Long-term versus Short-term Orientation

Long-term versus short-term orientation (LSO), refers to an individual’s attitude toward time: either viewing it holistically, attaching importance to the past and the future, or otherwise thinking that actions are only crucial for the moment or short-term impact (Bearden, Citation2006). An individual with a higher score in LSO values planning, tradition, working hard for future benefits, and perseverance. Such individual traits positively affect individuals’ performance in problem-solving (Scherer & Gustafsson, Citation2015), which is part of the creativity process (Torrance, Citation1977), and studies have shown that LSO is positively related to creativity (Hong et al., Citation2018; Kittová & Dušan, Citation2018).

2.3.4. Masculinity-Femininity

Masculinity-femininity (MF), refers to the dominance of gender-role patterns. A higher value of MF represents male assertiveness, and a lower MF represents female nurturance (Hofstede, Citation2001; Yoo et al., Citation2011). An individual with a higher MF value focuses on achievement and success. In comparison, one with a lower MF value is characterized by unity, equality, seeking consensus, and attentiveness toward social relations. Although studies have indicated a negative correlation between MF value and creativity (e.g. Nakata & Sivakumar, Citation1996), other researchers disagree and state that organizational cultural dimensions, such as MF, are positively correlated with employees’ creativity (Khan et al., Citation2017). Therefore, no definitive conclusion regarding the relationship between MF and creativity can be drawn yet.

2.3.5. Individualism-Collectivism

Individualism-collectivism (IC), collectivism (i.e. a higher score of IC) applies to societies in which people are integrated into strong, cohesive internal groups since birth. These groups continue to protect them throughout their lives in exchange for unquestioned loyalty. Individualism (a lower score of IC), on the other hand, applies to societies where individuals are loosely connected: everyone focuses on taking care of their own needs and those of their immediate family members (Hofstede, Citation1991). This can also be a state of mind, which might positively or negatively affect creativity (Tsegaye et al., Citation2020; Ye & Robert, Citation2017). On the one hand, individuals with a higher score in IC see themselves as group members instead of individuals and view both the group and individual equally or give preference to group goals. On the other hand, individuals with a lower score of IC see themselves as having higher priority than their group and value their personal goal(s) over the group’s collective goals (Triandis, Citation1989). There have been inconsistent results from studies into the relationship between IC and creativity. For example, individuals who value collectivism (a higher score of IC) had a lower score in creativity than individuals with a lower score of IC (Kurman et al., Citation2015). However, other researchers found that priming an individual’s collectivism (IC value) can improve creativity in group ideation (Ye & Robert, Citation2017). In addition, another study found that individuals with a higher collectivism value generated more original and high-quality ideas than individuals with individualism because collectivists look for higher levels of accuracy before contributing ideas (Saad et al., Citation2015).

2.4. Influence of Other Factors on Creativity

Except for culture, other factors also influence creativity, such as gender differences in divergent thinking (Razumnikova, Citation2004) and the adopted creative methods in creativity performance (Chulvi, Mulet et al., Citation2012; Koronis et al., Citation2021, Citation2019; Linsey et al., Citation2005; Shah et al., Citation2001). For example, Vieira et al. conducted a study to explore the effects of gender on frequency bands in constrained and open design tasks, which revealed the difference in brain activity between genders during problem-solving included in the process of creativity (Torrance, Citation1977; Vieira et al., Citation2022). Other researchers verified that creativity was influenced by the adopted creative methods (brainstorming, SCAMPER, and functional analysis); for example, applying functional analysis assisted participants in getting a higher score in usefulness, and brainstorming led participants to perform better in novelty (Chulvi, Mulet et al., Citation2012).

2.5. Research Questions

Although many studies have focused on culture and creativity, the relationship between culture and creativity is unclear, deserving further exploration (Kurman et al., Citation2015; Ye & Robert, Citation2017). Moreover, as mentioned above, when attempting to analyze the relationship between culture and individuals’ creativity (irrelevant to national and societal studies), it is better to measure the individual’s cultural values than to adopt national cultural values. Furthermore, creativity-related research needs to develop a fuller understanding of how it has been experienced from a phenomenological perspective (B. Nelson & Rawlings, Citation2009). Therefore, we formulated the following research questions:

(1) What is the relationship between cultural values and experience of creativity at the individual level?

(2) Do other factors affect the experience of creativity in this cultural context, such as gender, level of education, or the creative methods that are used?

3. Methods

3.1. Participants

We used the free downloadable software G*Power (Version 3.1.9.7) to calculate the sample size (Faul et al., Citation2007), for which we set the correlation coefficient r = 0.5, power = 0.8, and α = 0.05, which is acceptable (Shoukri et al., Citation2004). The results showed that 29 participants were needed. However, because of the COVID-19 social distancing restrictions, we recruited only 27 participants through posters that were shared on social media, such as WeChat. The participants were undergraduate and graduate students majoring in education, electronic and information engineering, bioscience, or statistics at a university in China. The mean age of the respondents was 22.56, with a standard deviation of 2.77; and 70.4% of the respondents were male, and 44.4% were undergraduate students, as shown in . We collected 27 valid responses for the CVSCALE and 54 effective responses (two design tasks x 27 participants) for the creativity questionnaire after completing each design task.

Table 1. Demographic characteristics of the participants.

3.2. Tasks

More than ten design tasks were selected from the existing studies on creativity (e.g. Chulvi, Mulet et al. (Citation2012); Ide et al. (Citation2020)). We discussed these design tasks and consulted creativity experts about relevant aspects of the tasks, such as the similar levels of difficulty, the level of balance, and their appropriateness, for our experiment. Based on the discussion and expert suggestions, we modified the two tasks and adopted them in the experiment. Task 1 was to design a new working table that takes up as little space as possible when not in use but provides a sufficient surface for working on when it is in use (Chulvi, Sonseca et al., Citation2012), as shown in the example outcome in . Task 2 was to arrange a small bedroom, using the space efficiently for furniture, such as the table, bed, shelf, sofa, and closet (Ide et al., Citation2020; see example in ).

3.3. Creative Methods Adopted for This Study

For choosing the creativity methods in our study, we decided to adopt the never-used or less-used creativity methods, to avoid their existing skills affecting creativity (Amabile & Hennessey, Citation2010). We selected the 6-3-5 method and the collaborative sketching (C-sketch) method based on two reasons. First, it is based on our previous study (Gong et al., Citation2022), which collected an online questionnaire to investigate the adopted creative methods (around 20 creative methods, such as mind-mapping, brainstorming, and SCAMPER) in higher education in different countries. The results showed that C-sketch and 6-3-5 were the least adopted creativity methods selected by participants (Gong et al., Citation2022). Second, in the pre-experiment, we asked participants to choose the creativity methods they had never used before. These two methods were selected as never-before-used methods.

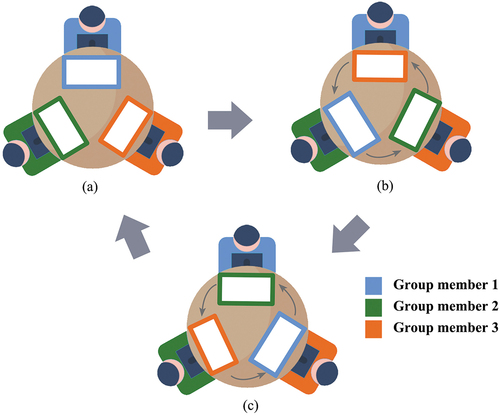

The 6-3-5 method was developed by Bernd Rohrbach (Citation1969) in German; while; it has been applied and developed by other researchers (Baruah & Paulus, Citation2019), such as Shah et al. (Citation2001), and Schröer et al., (Citation2010) in the past few decades. We conducted the experiment based on the 6-3-5 method explained by (Schröer et al., Citation2010) with three group members – less than 6 group members also acceptable (Linsey et al., Citation2005). Following the 6-3-5 method, group participants had to write down three ideas on a worksheet in a given amount of time ( and then pass the worksheet on to the next team member who had to add to the existing ideas (). This process is repeated until all group members have contributed and the worksheet has been filled in and returned to the initial contributor, as shown in . The 6-3-5 method only allows the representation of ideas by text (Törlind & Garrido, Citation2012).

C-sketch, originally named 5-1-4 G and proposed by Shah (Citation1993), considers groups of five participants. Each participant comes up with one idea, and four passes are made to the other members of the group. The ‘G’ indicates that the method is graphically oriented. The method was later renamed C-sketch in an attempt to provide a more descriptive name (Shah et al., Citation2000, Citation2001). Although the original methods were for six or five participants, three ideas or one idea, and five or four passes, many studies have subsequently changed these variables based on their study needs (Linsey et al., Citation2005). Therefore, we arranged three individuals randomly in a group to generate three ideas and make passes, as shown in .

3.4. Procedure

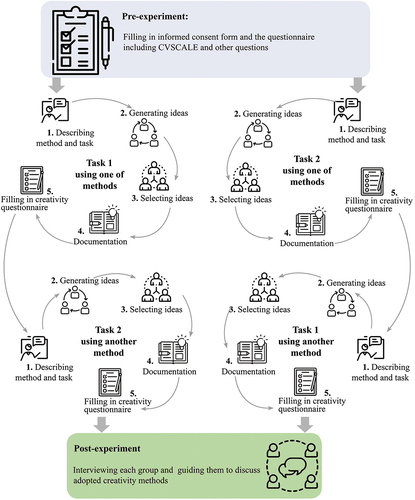

This experiment was divided into three stages: (1) the pre-experiment stage to fill in the individual cultural-values questionnaire; (2) the experiment conducted to complete the two design tasks; and (3) the post-experiment session to interview the participants about their experiences during the experiment, as shown in .

3.4.1. Pre-experiment

During the pre-experiment stage, we briefly explained the research aim and the process of the experiment, and the participants provided informed consent. They were guaranteed the right to withdraw at any stage without providing a reason. They were assured that their responses would be kept confidential, and anonymized data may be used in publications, reports, web pages, and other research outlets. Then they had to fill in the CVSCALE and answer other questions related to their gender, age, educational background, and previously unused creative methods (detailed description in Section 3.3). The 6-3-5 and C-sketch were selected as the never-used creative methods.

3.4.2. Experiment

We divided the 27 participants into random three-member groups; nine groups participated in the two design tasks. The two methods (6-3-5 method and C-sketch) were performed as two tasks (Task 1 vs. Task 2), implying that a counterbazlance was applied. After each task, they were required to complete the creativity questionnaire to self-evaluate their experience of creativity during the design ideation. Thus, each task consisted of five steps:

(1) A preparatory meeting with the participants to explain the creative method and simulate the process to ensure they understood how to apply the creative method during the concerned task (20 min), as described in Section 3.3.

(2) Perform the design tasks (6-3-5: total 15 min including three passes, 5 min for each pass, C-sketch: total 30 min including three passes, 10 min for each pass).

(3) Select the solution (5 min) to avoid potential misunderstandings in the group discussion.

(4) Documentation (20 min): the participants were asked to choose and improve on their best ideas.

(5) Completion of the creativity questionnaire (B. Nelson & Rawlings, Citation2009).

3.4.3. Post-experiment

After the experiment, we interviewed each group about their reflections on the creative process, asking questions like ‘How did you feel when you adopted the methods?’ and ‘Do you think others helped you improve your idea?’ Then, we guided the participants to discuss the advantages or disadvantages of each creative method adopted. They also compared the methods used in the experiment with other previously used methods.

3.5. Data Collection

3.5.1. Individual Cultural Values

For evaluating cultural values, we adopted the CVSCALE developed by Yoo et al. (Citation2011), who measured Hofstede’s cultural dimensions at the individual level (a 26-item in five dimensions) because this suited our research aims of collecting data on dependent variables at the individual level instead of at the national level. Many researchers have adopted the CVSCALE in their studies (e.g. (Chien et al., Citation2016)) and verified its acceptable validity and reliability (e.g. (Djamen et al., Citation2020; Prasongsukarn, Citation2009)). Moreover, several studies have applied the CVSCALE to measure the relationship between culture and other research fields, such as employees’ innovative behavior (Tsegaye et al., Citation2020). The questionnaire used a five-point Likert scale, ranging from strongly disagree = 1 to strongly agree = 5 for measuring all values. LSO was measured from not at all important = 1 to extremely important = 5.

Although the original CVSCALE has been adopted in many studies, only one study has utilized it in mainland China after excluding two items from PD (Schumann et al., Citation2010). Moreover, this study did not provide validity for each cultural value included in the revised questionnaire. Therefore, we tested the validity and reliability of this CVSCALE questionnaire before applying it in the present experiment. After removing three items with low loading (PD 2, and LSO 1 and 5), the questionnaire demonstrated acceptable validity (Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) measure = 0.75, p < .0005) with a statistically significant yet strongly positive correlation between each item and its respective dimension. The reliability of each subscale had either an acceptable or good level, as determined by a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.68, PD with four items; 0.80, UA with five items; 0.73, LSO with four items; 0.79, MF with four items; and 0.85, IC with six items. Although Cronbach’s alpha of one sub-scale (PD) was less than 0.7 (0.68), it was also acceptable (Vaske, Citation2019). We were then able to adopt the modified CVSCALE questionnaire to measure the individual cultural values in this study.

3.5.2. Experience of Creativity

We adopted the experience of creativity questionnaire from a phenomenological perspective because it represents a unique human experience and suits research on the creative process (B. Nelson & Rawlings, Citation2009). The questionnaire provides a tool for exploring the research topics related to the relationship between creativity and other aspects (B. Nelson & Rawlings, Citation2009). For example, a study addressing the relationship between the phenomenology of creativity and personality measured creativity by the experience of creativity and personality by the Big Five Inventory (B. Nelson & Rawlings, Citation2010). It used a five-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (not my experience) to 5 (very much my experience) to measure how the creative process is experienced. Although the authors mentioned that the original questionnaire could be used in domains related to creativity, we modified it to measure the experience of creativity during a design process, specifically for individuals who do not come from professional creativity or design backgrounds during the creative process.

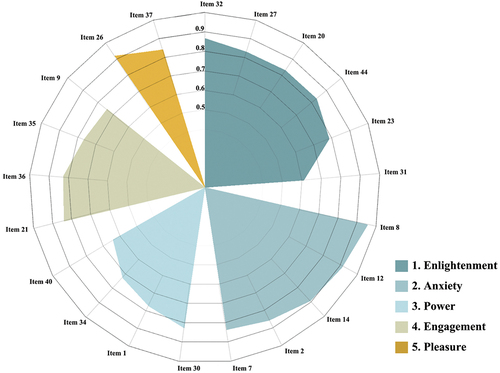

Our questionnaire was used to measure different underlying constructs. The scales of ‘enlightenment’, ‘anxiety’, ‘power’, and ‘engagement’ had acceptable levels of internal consistency, as determined by a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.82, 0.84, 0.74, and 0.76, respectively (Vaske, Citation2019), as shown in . Although Cronbach’s alpha for ‘pleasure’ was less than 0.7 (0.65), it consisted of only two items. According to a previous investigation (Vaske, Citation2019), the number of items in a scale influences the amount of inconsistency; therefore, Cronbach’s alpha of 0.65 for the pleasure construct is also acceptable (Vaske, Citation2019).

The first factor was labeled enlightenment, including six items, which refer to individuals in the creative process and experiencing a state of inspiration or enlightenment. The second factor was called anxiety, including five items related to the feeling of anxiety and vulnerability in the creative process. The third factor was named power, including four items to investigate individuals’ receptiveness to their ability and achievements in a creative process. The fourth factor was labeled engagement, consisting of four items, which aimed to explore the sense of freedom, the level of engagement, and individuals’ sense of discovery and being receptive to the creative process. The last factor was named pleasure, which refers to a sense of pleasure and satisfaction during the creative process.

3.6. Data analysis

We analyzed the relationship between individual cultural values and the experience of creativity in each method. Other possible influences were analyzed, such as gender, educational level, task order, creative method order, and type of creative method. Not all variables were normally distributed, as assessed by Shapiro-Wilk’s test (p < .05). Therefore, we used Spearman’s correlation, considered a non-parametric alternative to Pearson’s correlation, to test the relationship between cultural values and the experience of creativity. Moreover, the Mann-Whitney U test was used to determine whether differences existed between the two groups, which is the non-parametric alternative to the independent-samples t-test.

4. Results

4.1. Relationship Between Individual Cultural Values and the Experience of Creativity

We examined the relationship between individual cultural values and the experience of creativity seen in the two creative methods used in the experiment.

4.1.1. The 6-3-5 Method

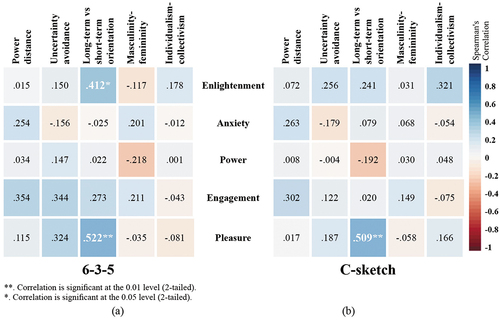

Spearman’s rank-order correlation determined the relationship between individuals’ experiences of creativity and cultural values when adopting the 6-3-5 method in design tasks, as shown in .

1) There was a statistically significant moderate positive correlation between enlightenment and LSO (rs(27) = .412, p = .033).

2) There was a moderate positive correlation between pleasure and LSO (rs(27) = .522, p = .005), which was statistically significant.

4.1.2. The C-sketch Method

When the C-sketch method was adopted for the design tasks, the Spearman correlation revealed that there was a moderate positive association between pleasure and LSO (rs(27) = .509, p = .007), as shown in .

4.2. The Influence of Other Factors on the Experience of Creativity

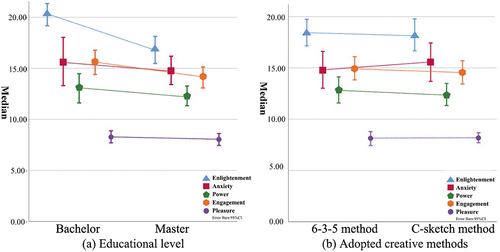

We ran a Mann-Whitney U test to examine whether there were any differences in creativity between gender (males vs. females), tasks (Task 1 vs. Task 2), method order, or task order. The median values reflecting the five factors of creativity were not significantly different statistically (Dinneen & Blakesley, Citation1973). Moreover, we tested for differences in the level of education in the experience of creativity scores. Enlightenment scores for bachelor students (median = 20) were moderately higher than those for master’s students (median = 17), U = 154.000, z = −3.609, p < .001 (. We also tested the differences in the experience of creativity scores between the methods of 6-3-5 and C-sketch. Although no statistical significance was found, the median scores of the 6-3-5 method were higher in all factors, except anxiety, than the C-sketch method, as shown in .

5. Discussion

This study revealed that two pairs of cultural values and the experience of creativity – LSO and enlightenment, and LSO and pleasure – had a moderate positive correlation with statistical significance, thereby answering research question 1 regarding the relationship between individual cultural values and the experience of creativity. Through an in-depth exploration of the above findings, we established a framework to explain the reasons for the relationship between individual cultural values and the experience of creativity, as discussed and illustrated in Section 5.1. Additionally, there was a statistically significant difference in educational levels and enlightenment. However, this does not mean that the educational level influences individuals’ experience of creativity. This partially answers the second research question about other influences on the experience of creativity, discussed in Section 5.2. Furthermore, although no statistical difference was found between the two creative methods in this study, the scores for the 6-3-5 method were higher in terms of the experience of creativity. Therefore, we conclude that the choice of creative method might impact the experience of creativity, partially answering research question 2 (discussed in Section 5.2).

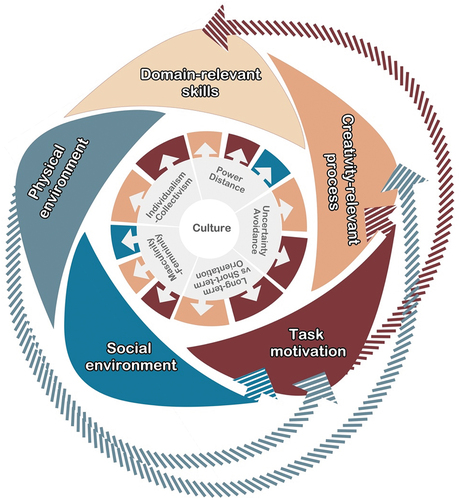

5.1. Culture and the Experience of Creativity

According to the component theory of creativity, four key factors influence individuals and their creative process: domain-related skills, creativity-related processes, task motivation, and social environment; physical environment can also affect creativity (Amabile, Citation2011; Gong & Georgiev, Citation2020). Because our study is focused on exploring individuals’ culture, the experience of creativity during the creative process, and the relationship between them, we attempted to identify the influence of cultural values on the five components of creativity in the context of design during ideation in order to outline a framework (). The direct influence of individuals’ culture, individual’s cultural values are influenced by their growing up environment (Hofstede, Citation2011), thus influencing creativity through task motivation, creativity-related processes, and social environment (The gray arrows from culture pointing to the corresponding colors of the components of creativity represent those direct effects in ). For example, the existence of a positive correlation between LSO and pleasure in our study might be because the participants value success more in the future than in the present. In addition, individuals feel satisfied and experience pleasure by learning new methods and recognizing their skills and abilities in ideation, which act as an intrinsic motivation, included in task motivation (Amabile, Citation2011). The indirect influence of individuals’ culture, each component of creativity interacts with the other components; when one of components is affected, there will be a knock-on effect on the other components (Amabile, Citation2011). Those interactions between components of creativity are also influenced by individuals’ culture, thus influencing individuals’ reactions and performance in creativity. For example, social environment affects task motivation and creativity-related processes (Amabile, Citation2011), and deeply exploring the effect is due to social environments’ interaction with individuals (e.g. individuals’ PD cultural dimension), thus affecting the individuals’ task motivation or creativity-related processes.

Figure 7. The influence of cultural values on components of creativity during ideation. The gray arrows pointing to the corresponding colors of the components of creativity represent that each cultural value directly affects those consistent components of creativity. The colorful arrows surrounding and pointing to the components of creativity affect the components toward which they point, which means the indirect influence of individuals’ culture on components of creativity.

Previous studies have verified that differences in PD levels affect how individuals express their opinions, their enthusiasm for interaction and communication during the design process, and diversity in their motivation levels in engaging in creativity processes (Erez & Nouri, Citation2010; Tian et al., Citation2018; Yuan & Zhou, Citation2015). They have also shown that people with a higher PD value are more likely to conform to authority. Leaders with a higher PD value their power and discourage subordinates from challenging them, which leads to a hierarchical working environment that does not support a relaxed social atmosphere required to generate creative output (Iorgulescu, Citation2014). Therefore, we summarize that PD value affects creativity-relevant processes, task motivation, and social environment, as shown in .

Surprisingly, there was no association between PD and the experience of creativity. Following related literature, we found that idea generation strategies might serve as moderators. It is important to note that our study’s methods (6-3-5 and C-sketch) are group ideation methods that help participants to draw or write their ideas simultaneously, without discussing them, leading to less interaction than in other ideation methods, such as brainstorming (Törlind, Citation2015). Interestingly, another study demonstrated that PD was irrelevant to creativity when the ideas were developed or modified from others’ ideas in group ideation, such as the 6-3-5 method (Thoring et al., Citation2014). Therefore, we conclude that the creative methods used in this study (less interaction, equal communication, independent consideration, and iterative idea generation) might be the reason for reducing the disadvantages (e.g. a tight hierarchical working environment) of group ideation that usually result from having a higher PD. In addition, there was no leader in the groups, and the instructor left the room after each task started. This meant that everyone shared equal power while performing the tasks. Specifically, the participants mentioned that they favor these methods more than other methods, such as brainstorming, where an individual can act as a leader. Others wanted to expand or follow the leader’s ideas and suppress their own ideas. Moreover, the participants stated that the adopted creative methods allowed them to think and express their thoughts more freely, in an equal manner without receiving judgment from others.

UA reflects risk-taking, which affects task motivation and creativity-relevant processes (Albar & Southcott, Citation2021; Wan et al., Citation2021), as depicted in . A lower level of UA leads to a higher level of risk-taking, such that individuals feel less anxious while performing a task and are more likely to accept challenges. However, people with a higher level of UA tend to have lower perceptions of self-efficacy and feel more anxious than their counterparts with a lower level of UA (Hofstede, Citation1980). According to the literature, Westerners with low UA are conducive to the creative stage, while Easterners with high UA are more suitable for the selection, editing, marketing, and acceptance stages (Adair & Xiong, Citation2018). However, a limited number of studies make it difficult to conclude the relationship between UA and the experience of creativity.

Overall, it is understandable that a negative association exists, albeit without statistical significance, between UA and anxiety in this study’s two design tasks. The design methods serve the purposes of idea generation, development, selection, and improvement. Individuals with high UA performed better in at least three steps: idea development, selection, and improvement (Adair & Xiong, Citation2018). Furthermore, based on the answers given in the interviews, we deduced that allowing enough time for individuals to complete each step and the documentation step might be the critical drivers encouraging further development of their solutions without feelings of anxiety.

Our analysis confirmed a positive association between LSO and the experience of creativity in two factors: pleasure and enlightenment. Therefore, we conclude that LSO affects task motivation and the creativity-relevant process (). To explore the possible reasons behind the positive association between LSO and pleasure, we explored the following answers to questions: ‘Did you get your inspiration during the ideation?’ and ‘How did you feel about the ideation process?’ Most participants mentioned that they enjoyed the experiment and will adopt these creative methods in performing routine tasks or tackling daily problems. Also, the participants stated that ‘this was an excellent practice to get to know our potential creativity, which we had not realized before, making us feel capable and empowered. The creative methods we used were helpful, and we enjoyed learning these effective methods, which could be beneficial for solving problems in study and future work’. Individuals with a high level of LSO believe that it is always necessary to prepare for the future (Kittová & Dušan, Citation2018). Learning these methods could help them solve problems in the future, which might be the reason for their feelings of pleasure.

Addressing the association between LSO and enlightenment that only existed in the 6-3-5 method, the participants explained that they were inspired by others when the worksheet was returned to them. They could develop or improve their iterated solutions. Moreover, the 6-3-5 method, without the sketches, provided an opportunity for greater diversity in thinking, unlike the C-sketch method with the illustrations that showed others’ ideas more clearly, which hindered the diversity of their critical thinking. From the responses above, we can deduce that the positive association between LSO and enlightenment results from text-based communication without illustrations, which provides the opportunity for diverse thinking in creativity-relevant processes. It is worth mentioning that textual content, featuring more abstract representation rather than pixelized illustrations, creates more space for the reiteration of ideas before formulating conclusions. The results were consistent with a previous study on LSO and ideation (building on the concept of others) that showed a positive correlation between the two; however, LSO might not affect visual ideation (Thoring et al., Citation2014).

It is difficult to determine the relationship between MF and the experience of creativity. Limited studies have observed this topic and presented ambiguous results (Xie & Paik, Citation2019). Therefore, we identified the implicit connections between MF and any possible component of creativity and found that MF may affect creativity-relevant processes, task motivation, and the social environment (). For example, individuals with a higher level of MF pay more attention to task-oriented achievements and have higher task motivation than individuals with a lower level of MF (Tsegaye et al., Citation2020; Yoo et al., Citation2011). Moreover, individuals with different levels of MF engage in different kinds of behavior, such as explorative behavior (Pelagio Rodriguez et al., Citation2014), some of which are related to the creativity-relevant process. Although gender is related to MF, and researchers have explored the effects of gender on design tasks (S. S. Vieira et al., Citation2022; S. L. da S. S. L. da S. Vieira et al., Citation2021) and creativity (Fink & Neubauer, Citation2006), it differs from MF in that MF considers the division of emotional roles between males and females rather than their biological differences (Hofstede, Citation2001).

Our study found that MF is positively related to engagement and anxiety and negatively related to power and pleasure. Although the results lacked statistical significance, they are consistent with previous research, verifying that a higher level of MF can lead to higher engagement in the ideation process (Tsegaye et al., Citation2020). However, the relationship between MF and the experience of creativity deserves further exploration.

Regarding the effect of IC on creativity, the literature cannot draw any clear conclusion. We summarize these views as follows. A higher level of IC leads to some constraints on developing diverse opinions and, hence, a lower level of creativity (Goncalo & Staw, Citation2006; Tsegaye et al., Citation2020; Wang et al., Citation2009). For example, individuals with a low IC score generated more ideas than those with a higher IC score (Wodehouse et al., Citation2011). Moreover, those with a high level of IC may experience conflicting priorities between their cultural norms of harmony and conformity; this conflict could decrease the willingness of individuals with a high IC value to contribute to group-led creative processes (Triandis, Citation2018; Wang et al., Citation2009). In contrast, those with a lower IC value, who values the expression of personal thoughts and ideas, particularly unique ones, could show a greater willingness to contribute to a group’s creative process (Triandis, Citation2018; Wang et al., Citation2009). However, other researchers hold the opposite view (Pelagio Rodriguez et al., Citation2014; Ye & Robert, Citation2017). Ye and Robert (Citation2017) showed that in virtual ideation priming collectivism could lead to more creativity than individualism. Although the relationship between IC value and the experience of creativity requires further investigation, our findings reinforce the notion that IC value affects task motivation and creativity-relevant processes ().

However, our case study showed no statistical correlation between IC value and each of the creativity factors in the ideation stage. We infer that the participants with a higher IC value might act as a moderator, reducing potential negative effects, such as social loafing, on creativity-relevant processes. The social loafing phenomenon occurs in group ideation and refers to the tendency of individuals to reduce their level of effort when working as a group than when working alone, leading to a loss of creativity during group ideation (Karau & Williams, Citation1993). However, the previous studies found that the social loafing phenomenon was not observed in Chinese individuals, who are considered to hold collectivistic beliefs (Earley, Citation1989). Our participants from China demonstrated a high IC value, implying that there might be an absence of linkage between the IC value and experience of creativity. However, this conclusion cannot be drawn yet. Further examination should be conducted in other countries to gain an understanding of the behaviors of individuals with lower IC values.

5.2. The Influence of Other Factors

Factors, such as the choice of creative method, can affect creativity (Gero et al., Citation2013); this study attempted to identify them. Education level (masters and bachelors) displayed a difference in creativity during the idea-generation stage. Although the two creative methods did not show any statistical difference in creativity, almost all the scores of the 6-3-5 method were higher than those of the C-sketch, as discussed below.

Our analysis showed a negative significant correlation between the level of education and experience of creativity, specifically concerning the enlightenment factor. We investigated the implicit influence of education level and the potential reasons behind the correlation. We are aware that the background of our participants could contribute to our findings (and limitations). They were recruited from a Confucian-based collective society in China, which encourages modesty, fitting in, and deference to assure harmony within the group, rather than arrogance (Cai et al., Citation2007). The common response of Chinese people is to be humble and modest toward others and about themselves and be aware of their own limitations and the vastness of the external (Lin et al., Citation2020), reflected in less positive self-evaluation (Uskul et al., Citation2010). The participants mentioned that they were inspired by others and realized their own limitations in creativity and the value of others’ creative ideas. Researchers have explored the relationship between the ‘Big Five’ factors of personality and levels of narcissism. The results indicated that a higher level of education led to a lower score for superiority and arrogance (Rubinstein, Citation2016). Therefore, we conclude that individuals from a Confucian-based collective society value modesty and humility (Lin et al., Citation2020), and individuals with a higher education level are more humble and modest (Rubinstein, Citation2016), thus having a less positive self-evaluation (Uskul et al., Citation2010). Therefore, we deduced that education level affects self-evaluation rather than creativity.

Although there was no statistical difference between the two creative methods utilized in our study in terms of experience of creativity, the respondents generally showed a more positive attitude toward the 6-3-5 method than C-sketch. These findings are not aligned with prior studies (Koronis et al., Citation2021; Shah et al., Citation2001). Previous research shows that the C-sketch method is superior to the 6-3-5 method regarding the quality and novelty of creativity outcomes (Koronis et al., Citation2021; Shah et al., Citation2001). A key reason behind the difference in our study is as follows: the participants in prior studies were designers or had previous experience with design-related subjects, and they were skilled at explaining their ideas through sketches or drawings. This could explain why the effectiveness of the C-sketch was higher than that of the 6-3-5 method. However, unlike such experiments, we recruited participants who could not draw or sketch professionally, explaining our results. As we discussed in Section 5.1, the participants believed that the 6-3-5 method, which uses written text rather than drawings, provided the opportunity for diversity in the creativity process, affecting the degree of enlightenment in the experience of creativity.

5.3. Limitations

One limitation of our study is that the participants were primarily from China, which could potentially lead to relatively minor differences between individual cultural values within the study group. The same experiment should be conducted in another country to explore the relationship between the experience of creativity and individual cultural values (individual cultural values among the two countries should be significantly different). Nevertheless, our study method can serve as a foundation for examining the relationship between culture and creativity during the ideation process. Another limitation is that we focused on the relationship between individual cultural values and creativity by measuring the experience of creativity based on the participants’ experiences during the ideation process; we will further investigate the relationship between individual cultural values and design creativity by evaluating creative outcomes. Moreover, a limitation of our study is that we employ a general domain-independent view of design, focusing on the initial generation of ideas in response to the design task.

6. Conclusion

This study examined the relationship between individuals’ cultural values and their experience of creativity by adopting two creative methods, namely the 6-3-5 method and C-sketch. According to creative processes observed among 27 participants, we found a positive association between LSO and pleasure for the two creative methods. Additionally, the 6-3-5 method demonstrated a positive association between enlightenment and LSO. Our discussion provided insights into the five cultural values (PD, UA, LSO, MF, and IC) that influence the experience of creativity based on our key results. Moreover, we discussed the influence of education level on self-evaluation and the choice of creative methods on the experience of creativity. Furthermore, our results revealed that individuals benefited from the 6-3-5 method, and were more relaxed, empowered, and satisfied than the C-sketch method; this differed from previous studies, reflecting the influence of the domain-related skills on creativity.

Our study contributes to the design field. First, it revealed that non-designers are willing to learn creative methods, participate in design tasks, and enjoy their work to be satisfied with design processes. Second, there are many creative methods in design ideation; therefore, it is important to select the suitable creative methods and consider participants’ cultural backgrounds. In our case, participants reported that the method of brainstorming was not ideal for them because they valued a relaxed and peaceful atmosphere for discussion without controversy, which is related to higher IC and PD values. Thirdly, rarely used creative methods are favored by participants. Accordingly, we might apply various creative methods in education, and students will have more options to create outputs or inspire their creativity in study or in daily life.

Our study might serve as a groundwork for future exploration into the relationship between individuals’ culture and creativity in the design process. Moreover, it might be interesting to compare designer and non-designer experiences of creativity and design creativity to explore the relationship between their cultural values and design creativity. Furthermore, learning creative methods or fostering creativity are not only beneficial for individuals from the design field but also provide more opportunities for individuals from other areas to create and enrich their lives, which should be considered in higher education.

Abbreviations

CVSCALE, cultural values scale; PD, power distance; UA, uncertainty avoidance; LSO, long-term versus short-term orientation; MF, masculinity-femininity; IC, individualism-collectivism; C-Sketch, collaborative sketching

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (19.2 KB)Disclosure statement

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed online at https://doi.org/10.1080/21650349.2022.2157889.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Adair, W. L., & Xiong, T. X. (2018). How Chinese and Caucasian Canadians Conceptualize Creativity: The Mediating Role of Uncertainty Avoidance. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 49(2), 223–238. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022022117713153

- Albar, S. B., & Southcott, J. E. (2021). Problem and project-based learning through an investigation lesson: Significant gains in creative thinking behaviour within the Australian foundation (preparatory) classroom. Thinking Skills and Creativity, 41, 100853. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tsc.2021.100853

- Albert, R. S. (1990). Real-world creativity and eminence: An enduring relationship. Creativity Research Journal, 3(1), 1–5. https://doi.org/10.1080/10400419009534329

- Amabile, T. M. (1982). Social psychology of creativity: A consensual assessment technique. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 43(5), 997. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.43.5.997

- Amabile, T. M. (2011). Componential Theory of Creativity. 538. Harvard Business School.

- Amabile, T. M., & Hennessey, B. A. (2010). Creativity. Annual Review of Psychology, 61(1), 569–598. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.093008.100416

- Bernd Rohrbach. (1969). Kreative nach Regeln: Methode 635, eine neue Technik zum Losen von Problemen. Absatzwirtschaft, 12, 73–75.

- Baer, J., & McKool, S. S. (2009). Assessing creativity using the consensual assessment technique. In Handbook of research on assessment technologies, methods, and applications in higher education, 65–77. https://doi.org/10.4018/978-1-60566-667-9.ch004

- Baruah, J., & Paulus, P. B. (2019). Collaborative Creativity and Innovation in Education. C. A. Mullen(Ed.) Creativity Under Duress in Education? (Vol. 3, pp. 155–177). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-90272-2_9

- Batey, M., Chamorro-Premuzic, T., & Furnham, A. (2010). Individual differences in ideational behavior: Can the big five and psychometric intelligence predict creativity scores? Creativity Research Journal, 22(1), 90–97. https://doi.org/10.1080/10400410903579627

- Bearden, W. O. (2006). A Measure of Long-Term Orientation: Development and Validation. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 34(3), 456–467. https://doi.org/10.1177/0092070306286706

- Borgianni, Y., Cascini, G., & Rotini, F. (2013). Assessing creativity of design projects: Criteria for the service engineering field. International Journal of Design Creativity and Innovation, 1(3), 131–159. https://doi.org/10.1080/21650349.2013.806029

- Cai, H., Brown, J. D., Deng, C., & Oakes, M. A. (2007). Self-esteem and culture: Differences in cognitive self-evaluations or affective self-regard? Asian Journal of Social Psychology, 10(3), 162–170. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-839X.2007.00222.x

- Chien, S.-Y., Sycara, K., Liu, J.-S., & Kumru, A. (2016). Relation between Trust Attitudes Toward Automation, Hofstede’s Cultural Dimensions, and Big Five Personality Traits. Proceedings of the Human Factors and Ergonomics Society Annual Meeting, 60(1), 841–845. https://doi.org/10.1177/1541931213601192

- Chulvi, V., Mulet, E., Chakrabarti, A., López-Mesa, B., & González-Cruz, C. (2012). Comparison of the degree of creativity in the design outcomes using different design methods. Journal of Engineering Design, 23(4), 241–269. https://doi.org/10.1080/09544828.2011.624501

- Chulvi, V., Sonseca, Á., Mulet, E., & Chakrabarti, A. (2012). Assessment of the Relationships Among Design Methods, Design Activities, and Creativity. Journal of Mechanical Design, 134(11), 111004. https://doi.org/10.1115/1.4007362

- Cropley, A. J. (2000). Defining and measuring creativity: Are creativity tests worth using? Roeper Review, 23(2), 72–79. https://doi.org/10.1080/02783190009554069

- Dean, D., Hender, J., Rodgers, T., & Santanen, E. (2006). Identifying Quality, Novel, and Creative Ideas: Constructs and Scales for Idea Evaluation. Journal of the Association for Information Systems, 7(10), 646–699. https://doi.org/10.17705/1jais.00106

- Détienne, F., Baker, M., Vanhille, M., & Mougenot, C. (2017). Cultures of collaboration in engineering design education: A contrastive case study in France and Japan. International Journal of Design Creativity and Innovation, 5(1–2), 104–128. https://doi.org/10.1080/21650349.2016.1218796

- Dinneen, L. C., & Blakesley, B. C. (1973). Algorithm AS 62: A Generator for the Sampling Distribution of the Mann- Whitney U Statistic. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society. Series C (Applied Statistics), 22(2), 269–273. https://doi.org/10.2307/2346934

- Djamen, R., Georges, L., & Pernin, J.-L. (2020). Understanding the Cultural Values at the Individual Level in Central Africa: A Test of the CVSCALE in Cameroon. International Journal of Marketing and Social Policy, 2(1), 28–41. https://doi.org/10.17501/23621044.2019.2105

- Earley, P. C. (1989). Social loafing and collectivism: A comparison of the United States and the People’s Republic of China. Administrative Science Quarterly, 34(4), 565–581. https://doi.org/10.2307/2393567

- Erez, M., & Nouri, R. (2010). Creativity: The Influence of Cultural, Social, and Work Contexts. Management and Organization Review, Nov, 6(3), 351–370. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1740-8784.2010.00191.x

- Faul, F., Erdfelder, E., Lang, A.-G., & Buchner, A. (2007). G*Power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behavior Research Methods, 39(2), 175–191. https://doi.org/10.3758/BF03193146

- Fink, A., & Neubauer, A. C. (2006). EEG alpha oscillations during the performance of verbal creativity tasks: Differential effects of sex and verbal intelligence. International Journal of Psychophysiology, 62(1), 46–53. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2006.01.001

- Furnham, A., Batey, M., Anand, K., & Manfield, J. (2008). Personality, hypomania, intelligence and creativity. Personality and Individual Differences, 44(5), 1060–1069. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2007.10.035

- Georgiev, G. V., & Casakin, H. (2019). Semantic Measures for Enhancing Creativity in Design Education. Proceedings of the Design Society: International Conference on Engineering Design, 1(1), 369–378. https://doi.org/10.1017/dsi.2019.40

- Georgiev, G. V., & Georgiev, D. D. (2018). Enhancing user creativity: Semantic measures for idea generation. Knowledge-Based Systems, 151, 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.knosys.2018.03.016

- Gero, J. S., Jiang, H., & Williams, C. B. (2013). Design cognition differences when using unstructured, partially structured, and structured concept generation creativity techniques. International Journal of Design Creativity and Innovation, 1(4), 196–214. https://doi.org/10.1080/21650349.2013.801760

- Glaveanu, V. P., Hanchett Hanson, M., Baer, J., Barbot, B., Clapp, E. P., Corazza, G. E., Hennessey, B., Kaufman, J. C., Lebuda, I., Lubart, T., Montuori, A., Ness, I. J., Plucker, J., Reiter-Palmon, R., Sierra, Z., Simonton, D. K., Neves-Pereira, M. S., & Sternberg, R. J. (2019). Advancing Creativity Theory and Research: A Socio-cultural Manifesto. The Journal of Creative Behavior, 54(3), 741–745. https://doi.org/10.1002/jocb.395

- Goncalo, J. A., & Staw, B. M. (2006). Individualism–collectivism and group creativity. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 100(1), 96–109. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.obhdp.2005.11.003

- Gong, Z., & Georgiev, G. V. (2020). Literature review: Existing methods using VR to enhance creativity. In Proceedings of the Sixth International Conference on Design Creativity (ICDC 2020). August 25-28, 117–124, Oulu, Finalnd. https://doi.org/10.35199/ICDC.2020.15

- Gong, Z., Soomro, S. A., Nanjappan, V., & Georgiev, G. V. (2022). The Gap in Design Creativity Education between China and Developed Countries. Proceedings of the Design Society, 2, 871–880. https://doi.org/10.1017/pds.2022.89

- Guilford, J. P. (2017). Creativity: A quarter century of progress. In Guilford, J. P.(Ed.), Perspectives in creativity (pp. 37–59). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315126265

- Gupta, M., Esmaeilzadeh, P., Uz, I., & Tennant, V. M. (2019). The effects of national cultural values on individuals’ intention to participate in peer-to-peer sharing economy. Journal of Business Research, 97, 20–29. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2018.12.018

- Hofstede, G. (1980). Motivation, leadership, and organization: Do American theories apply abroad? Organizational Dynamics, 9(1), 42–63. https://doi.org/10.1016/0090-2616(80)90013-3

- Hofstede, G. (1991). Empirical models of cultural differences. Bleichrodt, N., & Drenth, P. J. D. (Eds.), Contemporary issues in cross-cultural psychology (pp. 4–20). Swets & Zeitlinger Publishers.

- Hofstede, G. (2001). Culture’s Consequences: Comparing Values, Behaviors, Institutions and Organizations Across Nations. SAGE Publications.

- Hofstede, G. (2011). Dimensionalizing Cultures: The Hofstede Model in Context. Online Readings in Psychology and Culture, 2, 215. https://doi.org/10.9707/2307-0919.1014

- Hofstede, G., Hofstede, G. J., & Minkov, M. (2010). Cultures and Organizations: Software of the Mind, Third Edition. McGraw Hill Professional.

- Hong, J., Yang, N., & Hou, B. (2018). The effects of long-term orientation on entrepreneurial intention: A mediation model of creativity. Creativity and Innovation, 455.

- Ide, M., Oshima, S., Mori, S., Yoshimi, M., Ichino, J., & Tano, S. (2020). Effects of Avatar’s Symbolic Gesture in Virtual Reality Brainstorming. 32nd Australian Conference on Human-Computer Interaction, 170–177. https://doi.org/10.1145/3441000.3441081

- Iorgulescu, M.-C. (2014). The Impact of Management and Organizational Culture on Creativity in the Hotel Industry. Amfiteatru Economic Journal, 16(Special No. 8), 1205–1221. https://hdl.handle.net/10419/168887

- Jablokow, K. W., Zhu, X., & Matson, J. V. (2020). Exploring the diversity of creative prototyping in a global online learning environment. International Journal of Design Creativity and Innovation, 8(2), 102–124. https://doi.org/10.1080/21650349.2020.1713897

- Kampylis, P. G., & Valtanen, J. (2010). Redefining Creativity—Analyzing Definitions, Collocations, and Consequences. The Journal of Creative Behavior, 44(3), 191–214. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2162-6057.2010.tb01333.x

- Karau, S. J., & Williams, K. D. (1993). Social loafing: A meta-analytic review and theoretical integration. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 65(4), 681. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.65.4.681

- Kaufman, J. C., Baer, J., Cole, J. C., & Sexton, J. D. (2008). A comparison of expert and nonexpert raters using the consensual assessment technique. Creativity Research Journal, 20(2), 171–178. https://doi.org/10.1080/10400410802059929

- Kaufman, J. C., Lee, J., Baer, J., & Lee, S. (2007). Captions, consistency, creativity, and the consensual assessment technique: New evidence of reliability. Thinking Skills and Creativity, 2(2), 96–106. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tsc.2007.04.002

- Khan, A. A., Bashir, M., Abrar, M., & Saqib, S. (2017). The Effect of Organizational Culture on Employee’s Creativity, the Mediating Role of Employee’s Cognitive Ability. International Journal of Information, Business and Management, 9(2), 217. https://www.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/effect-organizational-culture-on-employees/docview/1903811671/se-2

- Kittová, Z., & Dušan, S. (2018). Culture as a Factor Influencing Creativity. 18th International Joint Conference Central and Eastern Europe in the Changing Business Environment. May 25, Bratislava, Slovakia and Prague, Czech Republic, 152–160.

- Kluckhohn, C. (1951). The Study of Culture. In H. D. Lasswell (Ed.), The Policy Sciences (pp. 86–101). Stanford University Press.

- Koronis, G., Casakin, H., & Silva, A. (2021). Crafting briefs to stimulate creativity in the design studio. Thinking Skills and Creativity, 40, 100810. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tsc.2021.100810

- Koronis, G., Meurzec, R. W., Silva, A., Leite, M., Henriques, E., & Yogiaman, C. (2019). Cross-Cultural Differences in Creative Ideation: A Comparison between Singaporean and Portuguese Students. Proceedings of the Design Society: International Conference on Engineering Design, 1(1), 89–98. https://doi.org/10.1017/dsi.2019.12

- Kroeber, A. L., & Parsons, T. (1958). The Concepts of Culture and Social System. The American Sociological Review, 23, 582–583. https://www.jstor.org/stable/42858956

- Kurman, J., Liem, G. A., Ivancovsky, T., Morio, H., & Lee, J. (2015). Regulatory focus as an explanatory variable for cross-cultural differences in achievement-related behavior. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 46(2), 171–190. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022022114558090

- Lee, S., Lee, J., & Youn, C.-Y. (2005). A variation of CAT for measuring creativity in business products. The International Journal of Creativity & Problem Solving, 15(2), 143–153.

- Lin, R.-M., Hong, Y.-J., Xiao, H.-W., & Lian, R. (2020). Honesty-Humility and dispositional awe in Confucian culture: The mediating role of Zhong-Yong thinking style. Personality and Individual Differences, 167, 110228. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2020.110228

- Linsey, J. S., Green, M. G., Murphy, J. T., Wood, K. L., & Markman, A. B. (2005). “Collaborating To Success”: An Experimental Study of Group Idea Generation Techniques. Volume 5a: 17th International Conference on Design Theory and Methodology, 277–290. https://doi.org/10.1115/DETC2005-85351

- Lubart, T. I. (1999). Creativity across cultures. In R. J. Sternberg (Ed.), Handbook of creativity (pp. 339–350). Cambridge University Press.

- Ludwig, A. M. (1992). Culture and Creativity. American Journal of Psychotherapy, 46(3), 454–469. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.psychotherapy.1992.46.3.454

- Mulder, M. (2012). The daily power game. Springer Science & Business Media.

- Nakata, C., & Sivakumar, K. (1996). National Culture and New Product Development: An Integrative Review. Journal of Marketing, 1, 61–72. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224299606000106

- Nelson, B., & Rawlings, D. (2009). How Does It Feel? The Development of the Experience of Creativity Questionnaire. Creativity Research Journal, 21(1), 43–53. https://doi.org/10.1080/10400410802633442

- Nelson, B., & Rawlings, D. (2010). Relating Schizotypy and Personality to the Phenomenology of Creativity. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 36(2), 388–399. https://doi.org/10.1093/schbul/sbn098

- Nelson, B. A., Wilson, J. O., Rosen, D., & Yen, J. (2009). Refined metrics for measuring ideation effectiveness. Design Studies, 30(6), 737–743. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.destud.2009.07.002

- Niu, W., & Sternberg, R. J. (2001). Cultural influences on artistic creativity and its evaluation. International Journal of Psychology, 36(4), 225–241. https://doi.org/10.1080/00207590143000036

- Nouri, R., Erez, M., Lee, C., Liang, J., Bannister, B. D., & Chiu, W. (2015). Social context: Key to understanding culture’s effects on creativity. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 36(7), 899–918. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.1923

- Pelagio Rodriguez, R., Hechanova, M., & M, R. (2014). A Study of Culture Dimensions, Organizational Ambidexterity, and Perceived Innovation in Teams. Journal of Technology Management & Innovation, 9(3), 21–33. http://dx.doi.org/10.4067/S0718-27242014000300002

- Prasongsukarn, K. (2009). Validating the cultural value scale (CVSCALE): A case study of Thailand. ABAC Journal, 29(2), 13.

- Razumnikova, O. M. (2004). Gender differences in hemispheric organization during divergent thinking: An EEG investigation in human subjects. Neuroscience Letters, 362(3), 193–195. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neulet.2004.02.066

- Rhodes, M. (1961). An Analysis of Creativity. The Phi Delta Kappan, 42(7), 305–310.

- Rinne, T., Steel, G. D., & Fairweather, J. (2012). Hofstede and Shane Revisited: The Role of Power Distance and Individualism in National-Level Innovation Success. Cross-Cultural Research, 46(2), 91–108. https://doi.org/10.1177/1069397111423898

- Rubinstein, G. (2016). Modesty doesn’t become me. Journal of Individual Differences, 37(4), 223–230. https://doi.org/10.1027/1614-0001/a000209

- Runco, M. A., & Jaeger, G. J. (2012). The Standard Definition of Creativity. Creativity Research Journal, 24(1), 92–96. https://doi.org/10.1080/10400419.2012.650092

- Saad, G., Cleveland, M., & Ho, L. (2015). Individualism–collectivism and the quantity versus quality dimensions of individual and group creative performance. Journal of Business Research, 68(3), 578–586. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2014.09.004

- Said-Metwaly, S., Noortgate, W. V. D., & Kyndt, E. (2017). Approaches to Measuring Creativity: A Systematic Literature Review. Creativity. Theories, 4(2), 238–275. https://doi.org/10.1515/ctra-2017-0013

- Sanders, P. (1982). Phenomenology: A New Way of Viewing Organizational Research. Academy of Management Review, 7(3), 353–360. https://doi.org/10.2307/257327

- Scherer, R., & Gustafsson, J.-E. (2015). The relations among openness, perseverance, and performance in creative problem solving: A substantive-methodological approach. Thinking Skills and Creativity, 18, 4–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tsc.2015.04.004

- Schröer, B., Andreas, K., & Lindemann, U. (2010). Supporting creativity in conceptual design: Method 635-extended. In DS 60: Proceedings of DESIGN 2010, the 11th International Design Conference, 10.

- Schumann, J. H., Wangenheim, F. V., Stringfellow, A., Yang, Z., Blazevic, V., Praxmarer, S., Shainesh, G., Komor, M., Shannon, R. M., & Jiménez, F. R. (2010). Cross-cultural differences in the effect of received word-of-mouth referral in relational service exchange. Journal of International Marketing, 18(3), 62–80. https://doi.org/10.1509/jimk.18.3.62

- Shah, J. J. (1993). Method 5-1-4 G-A variation on Method 635. MAE540 Class Notes, 635. https://ci.nii.ac.jp/naid/10012126180