ABSTRACT

Two polar viewpoints have emerged regarding Rwanda’s post-genocide development: (1) that economic development has improved the wellbeing of Rwandans and (2) that repressive policies have negatively impacted many. Assessing the impacts and inclusiveness of policies through trends among different social groups is timely in the context of the Sustainable Development Goals’ pledge to ‘leave no-one behind’. This study examines rural Rwandans’ perspectives on the changes affecting them. A multidimensional wellbeing approach was applied through mixed-method research involving 115 rural households in two locations in western Rwanda, in 2011–12. Findings reveal that the household-level impact was heavily influenced by socio-economic power and socio-ethnic grouping. Negative impacts, including restricted freedom and loss of material and cultural resources are disproportionately felt by the poorest. The indigenous Batwa suffer particularly detrimental impacts. The findings suggest that strategies deemed successful in making progress towards the Millennium Development Goals in Rwanda need, as a minimal measure, to be supported by social protection programs that specifically target the landless, vulnerable and cultural minorities. However, to align Rwanda’s development policies with the ambitions of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), a dramatic strategic shift is required to ‘leave no-one behind’ and avoid the reproduction of poverty and exacerbation of inequality.

Introduction

The objectives of global development policy have shifted in recent years, punctuated by striking differences between the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) and Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Notably, the underlying premise to ‘leave no-one behind’ represents a significant normative progression towards more inclusive development (Pogge and Sengupta Citation2016; Biermann, Kanie, and Kim Citation2017): Thus the emerging international development agenda and assessment criteria embodied in the SDGs have moved beyond income and asset ownership for the average citizen to consider a diverse range of impacts, including for example land tenure security and food insecurity, for specifically disaggregated social and cultural groups, such as indigenous peoples (Costanza, Fioramonti, and Kubiszewski Citation2016). This leap in ambition necessitates scrutiny of the strategies employed to pursue development goals, to determine their suitability to realize a more holistic and inclusive vision of development, and to identify options to reinforce, adapt or replace those strategies as necessary (Freistein and Mahlert Citation2016; Protopsaltis Citation2017).

Rwanda provides a pertinent case through which to explore the multiple objectives and diverse impacts of recent development policy. Debates about Rwanda’s post-genocide development, and particularly the impact of policies on the Rwandan population, polarize opinion. On the one hand, Rwanda is hailed as a shining example to other sub-Saharan African nations for the economic development which has been achieved and the recorded improvements in the lives of Rwandans. Economic growth has been consistently high for over a decade and Rwanda aims to be a middle-income country by 2020 (Crisafulli and Redmond Citation2012). Alongside these national economic trends, the proportion of the overall population suffering income poverty rapidly decreased from 57% to 45% between 2006 and 2011(NISR Citation2012). Rwanda topped the list of sub-Saharan African countries making progress towards the MDGs (UN Citation2013), as reflected by a 17% drop in the nation’s Multidimensional Poverty Index (MPI) from 2005 to 2010 (OPHI Citation2013).

Yet on the other hand, many take an opposing view that the nature of policies introduced, the vision of modernization they embody and the way in which they are implemented to meet both political and economic objectives has had considerable negative effects on the freedoms and practices of Rwandans and placed unfair burdens on some of the poorest in Rwandan society (Booth and Golooba-Mutebi Citation2012; Pritchard Citation2013; Ansoms and Cioffo Citation2016; Hasselskog Citation2017). Critics also point out that the Rwandan population consists of diverse groups with different levels of power not equally represented in policies, not least the three major ethnic groups: majority Hutu, minority Tutsi and less than 1% indigenous Batwa, and subgroups among them.

Since the end of the 1990s, numerous policies have been implemented by the Rwandan state, which combine strategies of reconciliation and development to try to include all citizens in a newly conceived citizenship (Booth and Golooba-Mutebi Citation2012; Hasselskog Citation2015). Indeed, national ‘development’ policies are rarely isolated from prevailing political agendas, and comprise multiple objectives influenced by international and national aims and associated discourses (de Sardan Citation1988; Lewis and Mosse Citation2006). Alongside the resettlement of large numbers of returning Rwandans after the war and the process of rebuilding institutions, the state has put forward a strong vision for the unity of Rwandans, incorporating modernization, development and the market orientation of a population consisting primarily of subsistence farmers (Clark and Kaufman Citation2008). These goals are often repeated through radio broadcasts, frequent local meetings, ingando education camps, umuganda monthly community services, and the appointment of local information officers (Purdeková Citation2008; Waldorf Citation2011). The rhetoric embedded in these attempts to persuade people to fulfill their potential to contribute to the national economy and to modernize housing, trade buildings and centers, maintain standards of hygiene, embrace new technology, send children to school, hold a bank account, medical insurance, take credit and form cooperatives. Specific policies with important implications for the rural population include: universal basic education provided free to all, widespread establishment of health centers and a national health insurance scheme, eradication of grass roofs nationwide through the ‘bye bye nyakatsi’ policy, a zero-grazing policy to restrict livestock interactions with crops, the villagization or imidugudu policy targeting the restructuring of scattered settlements through the establishment of rural centers (Newbury Citation2011); the crop intensification program and associated national land policy which seek to promote a ‘green revolution’ through maximizing land utilization and setting production targets for approved crops, facilitated by subsidized seeds and chemical fertilizers (ROR Citation2004; MINAGRI Citation2011; Dawson, Martin, and Sikor Citation2016). These highly centralized policies are not simply guidelines for desired behavior but are locally implemented and strongly enforced by local leaders provided with centrally-determined targets through a system of fines for non-compliance (Ingelaere Citation2011; Chemouni Citation2014; Hasselskog Citation2016). This suite of policies was applied through the latter stages of the MDGs and has continued into the current SDG era (Ansoms and Cioffo Citation2016; Harrison Citation2016).

Assessments of Rwanda’s post-genocide development have been poorly supported by disaggregated analyses or detailed case studies, and the impacts of these far-reaching policies on rural Rwandans, the vast majority of a rapidly growing population, remain unclear. Firstly, policy monitoring provides insufficient detail about how the poor are faring in Rwanda’s post-genocide development because documented successes often focus on aggregate national level data or, if disaggregated, tend to focus only on a limited selection of socio-economic indicators (Holvoet and Rombouts Citation2008; Dawson Citation2015; Ansoms et al. Citation2017). The few studies that disaggregate the Rwandan population in some detail reveal that levels of inequality are high and some have found rural poverty to be increasing (Ansoms and McKay Citation2010; WFP Citation2012; Finnoff Citation2015). These limitations also preclude a deeper understanding of the trajectories of different cultural and ethnic groups and interactions between them. This is an understandably sensitive research topic and explicit study of such issues in Rwanda is forbidden. Indeed, the state seeks to suppress attention to ethnic difference in Rwandan society with reference to ethnic groups removed from political representation, civil society and social policy, to the extent that mention of ethnic difference in daily life can be punished as an incitement of ethnic division or spreading of genocide ideology (Purdeková Citation2008; Reyntjens Citation2011). Counterproductively, this also means that external, national-scale generalizations about power relations between Hutu and Tutsi are common, and serves to problematize assessment of the extent to which the rights of cultural minorities with particular traditional practices and customary institutions, such as the Batwa, are being upheld (Beswick Citation2011).

Although the contrasting viewpoints about the impacts of Rwanda’s development strategy appear irreconcilable, this paper aims to illustrate why such divergent assessments have arisen, (a) through a more rounded look at the wellbeing of rural Rwandans and assessment of impacts upon them, and (b) by exploring the way in which social and institutional relations affect the outcomes for different social and ethnic groups (though not including a gendered analysis). Through in-depth qualitative study at two sites in western Rwanda, the article sheds new light upon the way in which policies are being experienced by diverse rural inhabitants and discusses implications for making progress towards the inclusive development ambitions of the SDGs. Specific attention is afforded to the indigenous Batwa, who are rarely included in such analyses.

Methodology

Conceptual approach

The wellbeing approach applied for this study draws from multiple theories and disciplines but is heavily influenced by Amartya Sen’s capability approach (Sen Citation1999; Gough and McGregor Citation2007). To look beyond simple material indicators, it seeks to represent ‘what a person has, what they can do and how they think and feel about what they both have and can do’ (McGregor, McKay, and Velazco Citation2007). It therefore focuses on the perceptions, values and experiences of participants themselves. ‘What a person has,’ is represented by different types of resources: natural, human, material, cultural and social, similar to sustainable livelihoods approaches (Bebbington Citation1999). ‘What they can do,’ represents the wellbeing outcomes someone is able to achieve with those resources. These outcomes include the capacity to meet certain basic needs in addition to achieving further goals regarding the quality of that person’s life. Basic needs are conceptualized here along the lines of Doyal and Gough (Doyal and Gough Citation1991), i.e. the level (for different categories including health, food, water, shelter, security) below which harm of an objective kind will result for any individual, and are therefore considered relatively universal for all. The definition of wellbeing utilized here also comprises a subjective dimension or ‘how they think and feel about what they both have and can do.’ It is this aspect of the definition which, importantly for the analysis presented in this paper, places the focus on an individual’s own perspective of what is important, the perceived value of different resources and what represents a good quality of life to them. Groups who apply different socially constructed, subjective meanings to ways of living and acting often occupy different relative positions of power in society and this differential power influences the standard of living they are able to achieve (Mosse Citation2010). Wellbeing outcomes such as poverty may be seen in part as the consequence of social categories and unequal power relations between them (Cleaver Citation2005). This wellbeing approach therefore necessitates attention to power relations between different groups and institutions. This article latterly tries to describe some of the social and political dynamics which influence rural inhabitants’ wellbeing in Rwanda.

Study sites and sampling approach

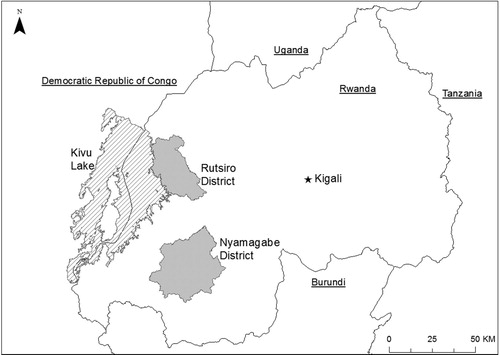

The following sections present results of mixed methods research (including six focus groups and 115 semi-structured interviews, described below) conducted in two rural areas in western Rwanda: one in Nyamagabe district in the southwest and the other in Rutsiro district in the northwest (). Both were remote, mountainous areas lying over 2,000 meters above sea level, without paved roads and with very limited public transport. Study sites are not nationally representative. Instead these areas were selected because they share characteristics typical of much of western Rwanda, with challenges to development caused by their remoteness from urban centers and topographic and climatic constraints to agriculture-based livelihoods. Agriculture was the dominant occupation in both areas, contributing to the income of all but three of the 115 households. Both study sites were also adjacent to protected forest areas, Gishwati Forest in Rutsiro and Nyungwe National Park in Nyamagabe.

Research was undertaken in two villages in Nyamagabe district and, due to the greater segregation of cultural groups, in four different villages in Rutsiro, over nine months from October 2011. Several weeks were initially spent at each site prior to formal research methods to introduce the purpose of the research to villagers, to gain the trust of and enhance mutual understanding with participants and importantly to allow a choice of whether to participate. Research participants in Rwanda do not commonly express their true preferences to strangers without attention to such factors (de Lame Citation2005) and so continual reflection on the researcher-participant relationship was particularly necessary to explore sensitive issues of social and institutional relations and the influence of policy discourse.Footnote1 The time spent in villages prior to formal data collection was also used to enhance understanding of local values and practices through participant observation and informal interviews. This allowed for a more informed selection of villages to include within the study to capture some of the different social groupings identified. The aim of sampling was to encompass as much of the variation present in the local population as possible rather than to represent proportionally the wider rural population.

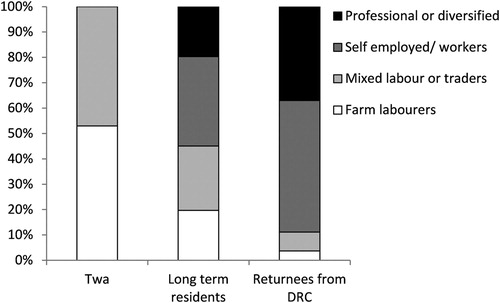

The study considers three separate socio-ethnic groups of relevance to this location. Reverting to simple ethnic labels of Tutsi and Hutu precludes a deeper understanding of cultural difference (Schraml Citation2014), so instead, based on observation in the two study sites, distinctions are drawn between: (1) the Batwa (16 of 115 interviews); (2) long-term rural inhabitants to these mountainous areas (excluding Batwa), predominantly Hutu (72 interviews), and; (3) those who returned to Rwanda from late 1994 from more fertile, less densely populated environments in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), just one group which forms part of Rwanda’s diverse Tutsi population (27 interviews). Detail on the history of these groups regionally and in the study localities is provided as supplementary information. Although undoubtedly of importance, differentiation by gender is outside the scope of this article.

Research methods

Focus groups were conducted in each village with a random sub-selection of interview participants to understand local conceptions of wellbeing and important drivers of changes in wellbeing. The facilitator posed one simple question regarding what it means to live well in that particular village and sought only to encourage further debate among the five to seven randomly selected participants. Focus groups always consisted of both male and female respondents. Semi-structured interviews were then performed to capture household level information regarding material wellbeing (in terms of material assets and ability to meet basic needs), subjective values held and the various changes which were perceived to have had an influence on the wellbeing of that household. Interviews were held in more than 10% of households in each village (between 15 and 20 in each village, 115 in total) with respondents selected at random from lists provided by local administrators. Quantitative data such as livestock and land holdings were commonly verified to check size and amount. Interviews took place with either household head or spouse. 42% of interview respondents were male, 58% female and 19% of those households had a female head.

From interview responses, more than 20 different income strands were identified in the two sites, and these were reduced to four categories to assign households to a socio-economic group. These groups consisted of households characterized by: (1) lower paid activities such as agricultural laboring or transporting goods; (2) more regular or higher paid laboring options such as tea labor, charcoal making, trade of low value goods or shepherding; (3) trade of own farmed crops, trees, cash crops, running a shop or taxi, or; (4) more professional occupations such as administration or local government, teachers or mechanics.

Results

Trends in commonly-measured socio-economic indicators

Elements of participants’ wellbeing improved considerably over the 10-year period to 2011/12. Provision of communal water taps during that time meant that every household could satisfy their basic need of year-round access to clean water (). Education levels increased substantially, evident by the pronounced difference between those of household heads and their children (). In 2011/12 only a minority of households lacked a single member with five years’ education or more (), an indicator given high priority in the MPI, making up one sixth of the index score compared to one eighteenth for clean water, housing or sanitation standard (Alkire and Santos Citation2014). Twenty-six percent of households attained this level of education in the preceding 10 years reflecting a rapid decrease in ‘multidimensional poverty’. The universal basic education policy (up to eight years) was introduced nationwide and in many cases incentivized through the provision of free meals. Therefore, few children of schooling age do not attend. Within the 10 years to 2012 health centers were built at each of the two sites, cutting travel time to the nearest modern health facility, meaning that many more illnesses can be treated locally and births now take place in medical centers attended by health professionals (Basinga et al. Citation2011). Rapid change has also occurred in some aspects of housing. Whereas in 2010 many rural homes were made with grass roofing, by late 2011 all rural homes in this study area, including the most basic constructions of earth and sticks, had modern roofs (). This change was enacted through the prohibition of natural roofing materials under the ‘bye bye Nyakatsi’ policy. Incomes and consumption potential have also increased for many households and are discussed in further detail in the next section.

Table 1. Selected socio-economic indicators by socio-economic group in 2011/12.

Locally-grounded indicators of wellbeing and poverty

Though the provision of services such as education, health and water improved greatly, this did not equate with local perceptions of trajectories in poverty and wellbeing. In contrast, many of the rural participants in this study maintained that they had become less well-off and less able to meet their basic needs. To explain the discrepancy it is important to explore local conceptions of wellbeing and poverty. The results of focus group meetings revealed a strong consistency with factors considered to be priorities in each village. These generally included: land; livestock; employment; health; housing; infrastructure; social relations and sharing; and finally autonomy over land use and investment decisions. Each of these elements were highlighted in at least five of the six focus group discussions. This list differs in several important ways to widely used indicators such as the Human Development Index or Multidimensional Poverty Index. Education, though commonly included in normative indicators of wellbeing and poverty, was notably absent. Returns to basic education are often very low in Sub-Saharan Africa (Barouni and Broecke Citation2014) and interview respondents frequently cited examples of people who had completed their basic education but did the same unskilled work for the same pay as those less educated.

Land and livestock (particularly to provide manure to fertilize the land) were commonly prioritized resources, which rarely feature in poverty indicators. Participants felt that without them people struggled to meet the need to provide sufficient food for their household. This clear response is not surprising in an area where topography and climate places severe constraints on food production and where a large proportion of the population farm for subsistence. Access to land was low with an average holding of less than one hectare ().

Table 2. Contextually relevant socio-economic variables by socio-economic group (changes refer to the preceding 10 years to 2011/12).

Variation in wellbeing and development impacts by socio-economic group

Land was distributed very unequally among participants: the lowest two socio-economic groups (44% of households) held on average less than a quarter of a hectare and just 15% of households owned 55% of the total area (). Only 30% of households earned any income from trading surplus crops. This paucity of land and income-earning potential explains the high proportion of households, particularly from poorer socio-economic groups who suffer regular food scarcity (having to go at least one entire day per month without a single meal, ). This situation was found to be deteriorating rather than improving. Furthermore, land inequality had increased over the 10 years to 2012 (). Population increase (including resettlement) and the subsequent intensification of land use, reduced fallow periods and reductions in livestock contributed to reduced productivity and decreasing land holdings. However, the passing of land to children or division of land for returnees was reported as the primary cause of decreased land holdings for only 4% of households. Instead political and economic factors meant land was being redistributed within the population, with 42% of those in the highest wealth category able to increase their holdings while 42% of those in the lowest two categories (farm laborers and mixed laborers) saw their land holdings decrease ().

The redistribution of land away from poorer households appeared to have been exacerbated by policies. Specifically, changes in land holdings were driven by the Rwandan land policy and subsequent crop intensification program, which had placed considerable restrictions on people’s freedom to use land as they wished and created tenure insecurity through the threat of expropriation for non-compliance (Dawson, Martin, and Sikor Citation2016). The costs of obtaining fertilizer and the importance of combining manure acted as a barrier to poorer households participating in (obligatory) agricultural policy schemes, to the extent that only 29% of the 115 households in this study applied fertilizers to their land (). Negative perceptions of the policy and its impacts were frequently voiced when interviewees were asked ‘Have you made any change to your farming methods?’ Reasons given related primarily to the constraints on the ability of households to subsist and the reduction of tenure due to the potential for the government to reallocate land to wealthier households who could afford various inputs. The reduction in tenure security accelerated redistribution as poorer households became more likely to sell land to wealthier households. The threat of land reallocation was considered a very real possibility, and 15 of the 115 households in this study had experienced being expropriated from land due to agricultural and forest policies within the last 10 years, three of them within the previous year in relation to crop specialization.

Rapid reductions in livestock holdings among the rural population () were a factor preventing people from investing in trade and agricultural inputs. Reductions in livestock occurred due to the increased living costs associated with: buying medical insurance to access health facilities or meeting medical costs; the cost of school materials for children; costs of buying food that people could no longer produce themselves, or; expenses incurred to comply with modernization policies such as ‘bye bye nyakatsi’. The prohibition of grazing on public land meant cattle must be caged and fodder be collected daily to feed them, which places a considerable burden on rural smallholders (Klapwijk et al. Citation2014). Forty-four percent of participants cited one or a combination of these reasons when questioned as to why they had substantially reduced their livestock holdings and only 12% of households had been able to sustain or increase their holdings.

The restrictions placed on people’s choices through these different policies explain the high priority participants place on autonomy as an important component of a good life. The same result can be found in other studies relating to Rwandans’ subjective wellbeing (Abbott and Wallace Citation2012; Ingelaere Citation2014). Its inclusion here was primarily justified with reference to specific policies. For example, tenure over land, housing and livestock was beginning to be affected by the villagization policy, which was in the early stages of implementation in the study areas during 2011/12. The policy aims to bring the entire rural population of the country into clustered settlements by 2020, ostensibly to provide services and better housing (ROR Citation2007). Local authorities had begun to sensitize and strongly encourage some remote households to move to central locations. Eleven interviewees (10%) voiced tenure security concerns for their homes and nearby land due to villagization. Some of those had already experienced considerable impacts, having to sell land and livestock to afford the higher costs of moving to a central location against their wishes.

It is noteworthy that, despite these negatively perceived and experienced policy impacts, common poverty measures such as income levels and consumption potential may, counterintuitively, reflect positive impacts. The redistribution of land to wealthier households and reduction in subsistence activities increased the need for many to seek income from other sources and buy food from markets. The main options available were agricultural laboring for local landowners, working on tea plantations or being involved in timber and charcoal production from the increasing number of private forests, in response to rising urban demand. The livelihood shift towards employed labor results, for many, in increased incomes and consumption potential while the shift away from subsistence farming and increased marketization results in reduced food security and perceived increases in poverty. Those impacts are exacerbated by occasional sharp, seasonal fluctuations in the price of staple foods such as beans, sweet potatoes and potatoes. For example, over six months in 2012 potato prices more than doubled while wages did not increase (Mbonyinshuti Citation2012). Price increases had been so severe during this time that 94% of participants stated that their families had changed the types of food they ate or reduced the number of meals they ate per day.

The reduction in material wellbeing for many rural inhabitants also explains why 41% of those interviewed were unable to afford health insurance and access health care, despite improved proximity to these services and almost one-fifth of households having medical insurance costs waived by the government (). Medical insurance cost 3000 Rwandan francs (c.US$4.50) per individual in 2012, though no household member was allowed access to treatment unless all household members had paid for their insurance.

Variation in wellbeing and development impacts by socio-cultural group

Although no questions specifically addressing ethnicity were posed, cultural difference was a clear indicator in the data collected. Differences were stark in terms of the resources each socio-ethnic group had access to and the outcomes they could achieve (). Most strikingly, land and livestock holdings were negligible for the Batwa, while being clearly highest for returnees from DRC, with long-term residents intermediate (). The absolute poverty faced by Batwa households was evident as 94% faced food scarcity (going at least one day a month eating no meals and often much more frequently than that), 100% were reliant on collecting firewood illegally for warmth and cooking, being unable to produce or afford to buy any, and 59% struggled to meet their basic needs of adequate shelter and lived in very small constructions of earth and sticks. Many of those living in more robust houses had received them from the government ().

Table 3. Socio-economic data by socio-ethnic group and study site (changes refer to the preceding 10 years to 2011/12).

In contrast to other groups, conceptions of wellbeing for the Batwa rested on finding laboring opportunities and on access to forest resources, despite hunting and other forest uses having been prohibited for many years. The forest played a clear role in their culture and livelihood activities. Even once removed from forests, they collected and sold forest resources to non-Batwa such as firewood, material for ropes, honey, medicinal plants and wild meat. But the increased protection of forests meant that the risks involved had increased thus reducing these practices rapidly. At both sites, Batwa were acutely aware that their own activities were not proven causes of deforestation and perceived that they had been treated unjustly through that process. As one male Batwa expressed:

That (the forest) was our source of livelihood, where we got everything and we do not find any alternative … … Our culture is starting to disappear. Like knowing how to look for honey, our children no longer know how that is done. … ..The forest now is for the government and for people who got jobs in the forest … .. For us we can only look at it like a poster!. (Focus group discussion with seven Batwa participants, Rutsiro District, 2nd May 2012)

Through the trade and exchange of forest goods, the Batwa had always interacted with other groups outside of the forest, but were not treated as equals. Although there had been a substantial change in the way Batwa were treated by others, relations had changed from physical abuse and discrimination to mere discrimination. As described by a female Batwa resident:

Nobody here gets beaten anymore without any reason. We could be struck by people as we were accused of stealing. Or even people would say ‘what right do you have to be taking this path?’ and could beat us. We couldn’t take those cases to anyone to seek justice because they were the very people who would beat us.. (Focus group discussion with seven Batwa participants, Rutsiro District, 2nd May 2012)

Sweeping doesn’t require somebody with school qualifications, or at least to be a guard you don’t need a high level of education! Even the guards there at the sector offices are no stronger than us. They are the same like us but we aren’t chosen for that work, you can’t find a Batwa working there. Having a sustainable job doesn’t require just education, your ethnicity is a factor. (Focus group discussion with seven Batwa participants, Rutsiro District, 2nd May 2012)

The main occupations provide a strong indication of the variation in socio-economic position between households in each of the three groups (). More than half of Batwa households depended only on agricultural labor, transporting materials or collecting grasses, as opposed to only a very small minority of returnees and less than a fifth of long-term residents. During focus group discussions both returnees and long-term residents placed land as the key resource required to live well. However different choices in land use were indicative of some cultural differences as only 26% of returnees traded crops (), a far lower proportion than long-term residents despite their greater land holdings. Returnees had instead begun to plant trees to engage in the charcoal and timber trade (52% of returnee households). The majority also reared cows (55%, ) to enable them to consume and trade milk. Education levels tended to be much higher among returnees () who overwhelmingly occupied the higher two livelihood categories, with 37% of households receiving income from professional or diversified occupations, a proportion of which were as local administrators with decision-making powers.

After the challenges posed by resettlement, many returnees who stayed in their new villages had been able to adapt and accumulate resources relative to other groups. When others decided to leave, they commonly sold the land they had been provided with to fellow returnees, something commonly highlighted as inequitable by long-term residents. The achievement of a favorable relative position, emphasized by their greater relative land and livestock holdings (), was partly explained by their political representation. Returnees collectively influenced decision-making and negotiated outcomes suited to their experience and culture. For example, returnees in Rutsiro had been able to argue against keeping livestock caged at home and instead converted crop land to a landscape scarcely seen in Rwanda, of rolling green pastures where cattle roamed monitored by shepherds, in place of the patchwork of cropland that typifies the rest of the country.

In contrast to returnees, only a small minority of long-term residents could be classed as having diversified or professional livelihoods, with most occupied by traditional modes of agriculture on relatively small land parcels (). These subsistence practices meant relatively few long-term residents suffered food scarcity, yet also meant higher proportions were unable to afford expenses such as medical insurance (). The agricultural and associated social practices of long-term residents conflicted with the vision of modern, profit maximizing rural inhabitants supported by government policies. Many of the remainder suggested that they would likely sell their land rather than see it reallocated because of their inability to grow approved crops successfully. In the meantime, many risked fines by continuing to practise polyculture, provoking potential conflict with local authorities. The social relations and practices built around traditional farming practices are also contrary to the vision of a modern Rwandan and local authorities sought to dismantle them by actively preventing the traditional gatherings by which much sharing took place (Dawson, Martin, and Sikor Citation2016). A minority of wealthier individuals and particularly young, educated adults from wealthier households were very dismissive of past traditions and felt part of the new movement towards modernization. However, relatively poor long-term residents frequently referred to the rapid reduction in levels of sharing of harvests, meals, labor and resources between households, social protection mechanisms which had been part of village life in the past but had diminished due to developmental policies and discourses surrounding marketization.

Exceptions to the rule: inconsistencies in status between socio-cultural groups

Wellbeing and cultural identities were not uniform for all Batwa. Despite rejection of their cultural practices and the discrimination they are subjected to, some Batwa appeared to be affected by the discourse surrounding a new Rwandan culture (although here perceptions of the researchers may have some influence on responses). As one respondent explained, ‘The culture has changed, and because of the new vision of development it has to,’ adding that despite the hardships they have faced in transitioning away from forest-based livelihoods, that ‘now we feel like it was the right thing to do.’ Whereas some had only been recently removed from forest areas or may even still practice some forest use, others have never known these connections in their lifetimes. Batwa may move between areas and many in Rutsiro had come from semi-urban areas to the newly formed settlement. Others had lived only a few miles from the forest, yet it played little part in their lives. In trying to discuss common Batwa cultural values, conversations revealed frequent disagreement, even regarding whether forest access should be granted or not.

There were also examples of Batwa who were sufficiently empowered to transform their household’s fortunes. One man refused to accept rejection from a tea plantation job on ethnic grounds, instead successfully pleading for a chance to prove himself, which may ultimately enable other Batwa to do the same. Similarly, one female household head overcame corruption when denied access to donated livestock for refusing to pay the associated bribe to local officials. She sought justice at sector and district levels and although dissuaded at several stages, she persisted and eventually became the only Batwa in this study to own a cow ().

Power relations between residents and returnees were not consistent between the two sites. In Nyamagabe a small group of long-term residents formed the elite, dominating local organizations and economy. Their families were given land in Nyamagabe in the 1980s as part of the European Commission Development Project. They found continued options for work and gained tenure over unused land after the project ceased operating in 1993. Six of these long-term resident households were interviewed as part of the random sample and their average land holding was 2.9 hectares as opposed to just 0.27 hectares for the other 23 long-term residents sampled there. This group therefore formed a substantially wealthier class of about 40 households in the area, some of whom had been able to accumulate sufficient wealth to send their children to private schools, acquire more land and livestock and who provided laboring opportunities to others in the area. This drives the difference in average land size between study areas (). This group formed cooperatives for cultivating, livestock and for tea growing, for which membership costs were prohibitive to others, including many returnees. Returnees in Nyamagabe struggled to accumulate wealth and most retained small, basic houses alongside the Batwa, located on a distinct hillside to the larger homes of longer-term residents.

Discussion and conclusion

Rwanda has undergone enormous change since the mid-1990s. The enacted state-led political agenda represents a significant alteration to the lives and livelihoods of ordinary Rwandans (Booth and Golooba-Mutebi Citation2012; Hasselskog Citation2015). Considerable successes have been realized and recorded, particularly through the provision of services to rural areas including clean drinking water, education and health facilities alongside consistent economic growth (UN Citation2013). However, to evaluate trends in poverty and wellbeing and draw conclusions about the effectiveness of development policies necessitates a focus beyond objective measures such as asset ownership and years of education, to consider more context-specific values and practices which may determine experiences of change (Ravallion Citation2011; Shaffer Citation2013). This study in western Rwanda reveals that standard measures of poverty based on income, consumption or even broader measures such as the Multidimensional Poverty Index, fail to reflect even material factors that are crucially important to the lives and wellbeing trajectories of rural Rwandans. Due to lack of adaptation to context and inattention to social and cultural diversity, standard poverty indices are shown to be a mirage detracting attention from some of the most important changes in key resources for rural inhabitants. These findings have considerable implications for the strategic transformation required to align with emerging international norms of inclusive development, reduced inequality and eradication of all forms of poverty manifest in the SDGs.

While Rwanda’s development policies have been deemed successful through limited impact evaluations, this locally-grounded and socially disaggregated assessment reveals those same policies have exacerbated inequality and imposed considerable burdens and restrictions on some of the poorest in Rwandan society. Strategies to modernize and marketise the rural Rwandan population serve to redistribute valued resources away from the poorest and most marginal towards the wealthiest and most powerful who are able to comply and accumulate, supporting descriptions of the suite of top-down policies as ‘internally exclusive’ (Purdeková Citation2008). The policy strategies employed in Rwanda may therefore require reconsideration or substantial buttressing through targeted pro-poor initiatives to align with the SDGs, including SDG 10 to reduce inequality and SDG 1 to eradicate poverty.

Land and livestock are particularly important resources to rural Rwandans, and evidence at the national level, supportive of the findings presented here, shows trends of increasing inequality in ownership and decreasing access for the poor (Finnoff Citation2015). The omission of land and livestock from development indicators enables positive trajectories in the wellbeing of Rwandans to be publicly presented even as the poorest are rapidly losing the land, livestock and related food sufficiency on which their wellbeing depends. The inclusion of indicators relating to food insecurity and land tenure within SDGs 1 and 2 (Smith, Rabbitt, and Coleman-Jensen Citation2017) therefore represents important progress with scope to inspire reassessment of Rwanda’s policy direction. However, their progressive influence is likely to be hampered by: lack of existing data and therefore inability to retrospectively assess trends; limited capacity to collect data, and; a likely focus on legally recognized property rights rather than historic or customary tenure, including non-consideration of forest tenure for groups such as the Batwa. To mitigate the ongoing processes of land and livestock dispossession among the poorest Rwandans, caused in part by agricultural policies with developmental aims, programs must be introduced to specifically support land access and tenure security for those with little or no land, to protect against the likelihood of the poor needing to sell land to meet other costs (often associated with development policies) and to enable the continuation of subsistence activities, associated social practices and local trade systems.

Development policies should not be judged on material outcomes alone, but should also consider impacts on non-material values and quality of governance. Participants in this study emphasized non-material social and political factors such as social relations and levels of autonomy for people to make their own decisions as important factors in the way people experience change. The governance of change in Rwanda has consisted of centrally-designed and strongly-enforced ‘development’ policies, which have imposed a transformation and placed considerable demands on their subjects (Gaynor Citation2014). The Rwandan political system shows little sign of transformation to more inclusive governance. With the aim to transform Rwandans into marketized, modern individuals, many restrictions have been placed on their own valued practices (for subsistence, social and cultural as well as economic purposes). As little scope is provided for choice, gradual adaptation or local negotiation, those restrictions act as important mechanisms through which people perceived and experienced impact. Rwanda’s land and agricultural policies have caused particularly negative impacts on rural communities (Van Damme, Ansoms, and Baret Citation2014; Dawson, Martin, and Sikor Citation2016). Despite the confounding, gradual effects of growing population, results of this study further detail mechanisms by which negative policy impacts are suffered, such as the centralized imposition of crop types at the regional scale, repression of farming and social practices, and state-induced insecurity of tenure over land and property. Such factors are given little attention in the economic analyses which dominate evaluation of impacts on the Rwandan population. Yet such key components of governance quality should receive considerable attention and scrutiny as part of approaches to pursue SDG 16: ‘Promote peaceful and inclusive societies for sustainable development, provide access to justice for all and build effective, accountable and inclusive institutions at all levels.’ This goal includes targets for: representation of different societal groups in decision-making bodies; the existence of effective independent human rights institutions; the nature of interactions between citizens and government officials; perceived levels of discrimination and harassment, and; perceived inclusiveness and responsive of decision-making. The extent to which such international norms gain traction in Rwanda and are adopted, assessed, scrutinized by key state, non-governmental and private sector donors and partners and embedded in Rwanda’s development policies will have a key influence on the lives of rural Rwandans going forward.

Rural Rwandans differ considerably in the way they value different resources and practices and are therefore affected in diverse ways by changes. In general, long-term residents, returnees from DRC and Batwa all displayed different preferences and practices, particularly regarding land use, which serve to reflect their different cultural knowledge and practices. There was also considerable spatial and social segregation between these groups. In the two rural areas in this study, returnees and wealthier long-term residents were more aligned with the state’s envisioned transformation, and have utilized their own capacity but also relatively strong representation to attune to the new discourse defining Rwandan culture and citizenship. Many of these local elites pour derision on the ways in which they used to act: not seeking to accumulate wealth, not wearing shoes, using traditional materials in place of modern alternatives. In contrast, the values and preferred practices of others are being rapidly and forcefully eroded and subsumed.

Material accumulation is not new to rural Rwandans, but in the past those objectives functioned alongside a locally-focused subsistence economy and associated social and cultural systems. Many poorer long-term residents lamented restrictions on their lives, including traditional gatherings and goods. For the large proportion of rural inhabitants unable to live up to the vision of a Rwandan citizen, such as those unable to afford soap, school materials for their children or the large proportion of people unable to buy medical insurance (let alone invest in new agricultural technologies), the loss of local social and economic systems and increased economic burdens associated with modernization policies serve to emphasize difference and represent a process of marginalization of the poor. The unequal power between groups, divided on interrelated socio-economic and socio-cultural grounds, played a strong role in the reproduction of social status, an effect which has been documented in other countries, including neighboring Tanzania (Cleaver Citation2005). Although SDGs appear, commendably, to disaggregate indicators by gender, age, disability and indigenous groups, the lack of attention to social and cultural difference, values and practices has been heavily criticized by cultural minorities and indigenous groups (Briant Carant Citation2016). Given the political suppression of cultural diversity and non-recognition of the indigenous Batwa to date, Rwanda is unlikely to take a more progressive stance on this issue than any international policy templates.

The majority of Batwa were excluded both from their traditional forest dwellings and livelihoods on one hand, and on the other also excluded from the economic diversification and market integration pursued by and promoted for other rural inhabitants. Many of them exist outside of either the traditional or the modern, excluded from both the old and the envisioned new ways of life. Although some Batwa appeared supportive of the Government’s modernization policies, many more perceive this to be a crucial time for both their culture and ability to meet basic needs. Negative stereotyping, denial of rights and segregation are all features of Batwa life (Kidd Citation2008) and of the countries inhabited by Batwa, Rwanda provides the least access to traditional forest land or compensatory support (Jackson and Payne Citation2003). The removal of ethnic identities in Rwanda represents a democratic paradox as promotion of equality has precluded recognition and representation of their specific needs required to achieve meaningful poverty alleviation (Beswick Citation2011). Recognition of their indigenous status or the historical injustices surrounding their dispossession and detachment from ancestral lands and traditional practices is not on the horizon through either national politics or international sustainable development governance.

It is important to acknowledge that, although ethnicity has a considerable influence on the way development is experienced, generalizations about the relative power of ethnic groups do not always hold at a local level. Findings of this study revealed that Tutsi do not always form the elite, and that Batwa may exhibit levels of agency to uphold rights in the face of social and political barriers. Levels of power are influenced by long-term socio-economic, political, cultural factors and psychological factors, at individual and local as well as national scales.

The centrally-planned modernization and marketization drive, and envisioned citizenship which Rwandan policies promote do not represent a gradual, negotiated acculturation but a much more engineered future identity which has undeniably significant impacts (Reyntjens Citation2011). The positive achievements of service provision are offset and in many cases overshadowed by the negative effects to key resources like land and livestock, and related tenure insecurity and restricted freedom of choice. Because negative experiences are disproportionately incurred by the poorest and most marginal rural inhabitants, often threatening their very basic needs, the rural population is being polarized and social difference counterproductively being amplified. These trends, although often overlooked, will play a key role in Rwanda’s economic, social and political development in the years to come.

Acknowledgements

I am grateful to Adrian Martin and Thomas Sikor for their guidance in supervising my PhD, including this chapter, as well as two anonymous reviewers for their time and suggestions. This study was made possible through funding from the Social Sciences Faculty of the University of East Anglia. Permitting and logistics were aided by staff at the Rwanda Development Board, Wildlife Conservation Society and Forest of Hope in addition to village chiefs and local executive secretaries. Above all I am thankful to those who participated in and contributed to the study.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Interview respondents frequently shared perspectives on sensitive or stigmatized issues such as personal health, intra-household relations and corruption suggesting a level of trust had been attained. Ethical clearance was obtained from the host university in the UK and official permits were obtained from the Rwanda Development Board. The research project and purposes (being to study the impacts of change on the wellbeing of rural inhabitants) were presented clearly to Rwandan government officials at the central level in Kigali as well as sector, cell, national park and village levels in addition to regional military representatives.

References

- Abbott, Pamela, and Claire Wallace. 2012. “Happiness in a Post-Conflict Society: Rwanda.” In Happiness Across Cultures, edited by Helaine Selin, and Gareth Davey, 361–376. Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands.

- Alkire, Sabina, and Maria Emma Santos. 2014. “Measuring Acute Poverty in the Developing World: Robustness and Scope of the Multidimensional Poverty Index.” World Development 59: 251–274. doi: 10.1016/j.worlddev.2014.01.026

- Ansoms, An, and Giuseppe D. Cioffo. 2016. “The Exemplary Citizen on the Exemplary Hill: The Production of Political Subjects in Contemporary Rural Rwanda.” Development and Change 47 (6): 1247–1268. doi: 10.1111/dech.12271

- Ansoms, An, Esther Marijnen, Giuseppe Cioffo, and Jude Murison. 2017. “Statistics Versus Livelihoods: Questioning Rwanda’s Pathway Out of Poverty.” Review of African Political Economy 44 (151): 47–65. doi: 10.1080/03056244.2016.1214119

- Ansoms, An, and Andrew McKay. 2010. “A Quantitative Analysis of Poverty and Livelihood Profiles: The Case of Rural Rwanda.” Food Policy 35 (6): 584–598. doi:10.1016/j.foodpol.2010.06.006.

- Barouni, Mahdi, and Stijn Broecke. 2014. “The Returns to Education in Africa: Some New Estimates.” The Journal of Development Studies 50 (12): 1593–1613. doi: 10.1080/00220388.2014.936394

- Basinga, Paulin, Paul J. Gertler, Agnes Binagwaho, Agnes L.B. Soucat, Jennifer Sturdy, and Christel M.J. Vermeersch. 2011. “Effect on Maternal and Child Health Services in Rwanda of Payment to Primary Health-Care Providers for Performance: An Impact Evaluation.” The Lancet 377 (9775): 1421–1428. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60177-3

- Bebbington, Anthony. 1999. “Capitals and Capabilities: A Framework for Analyzing Peasant Viability, Rural Livelihoods and Poverty.” World Development 27 (12): 2021–2044. doi: 10.1016/S0305-750X(99)00104-7

- Beswick, D. 2011. “Democracy, Identity and the Politics of Exclusion in Post-Genocide Rwanda: The Case of the Batwa.” Democratization 18 (2): 490–511. doi: 10.1080/13510347.2011.553367

- Biermann, Frank, Norichika Kanie, and Rakhyun E. Kim. 2017. “Global Governance by Goal-Setting: The Novel Approach of the UN Sustainable Development Goals.” Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability 26–27: 26–31. doi: 10.1016/j.cosust.2017.01.010

- Booth, David, and Frederick Golooba-Mutebi. 2012. “Developmental Patrimonialism? The Case of Rwanda.” African Affairs 111 (444): 379–403. doi: 10.1093/afraf/ads026

- Briant Carant, Jane. 2016. “Unheard Voices: A Critical Discourse Analysis of the Millennium Development Goals’ Evolution into the Sustainable Development Goals.” Third World Quarterly 38: 16–41. doi: 10.1080/01436597.2016.1166944

- Chemouni, Benjamin. 2014. “Explaining the Design of the Rwandan Decentralization: Elite Vulnerability and the Territorial Repartition of Power.” Journal of Eastern African Studies 8: 246–262. doi: 10.1080/17531055.2014.891800

- Clark, Philip, and Zachary Daniel Kaufman. 2008. After Genocide: Transitional Justice, Post-Conflict Reconstruction and Reconciliation in Rwanda and Beyond. Cambridge: Cambridge Univ Press.

- Cleaver, Frances. 2005. “The Inequality of Social Capital and the Reproduction of Chronic Poverty.” World Development 33 (6): 893–906. doi: 10.1016/j.worlddev.2004.09.015

- Costanza, Robert, Lorenzo Fioramonti, and Ida Kubiszewski. 2016. “The UN Sustainable Development Goals and the Dynamics of Well-Being.” Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment 14 (2): 59. doi: 10.1002/fee.1231

- Crisafulli, Patricia, and Andrea Redmond. 2012. Rwanda, Inc.: How a Devastated Nation Became an Economic Model for the Developing World. London: Macmillan.

- Dawson, Neil. 2015. “Bringing Context to Poverty in Rural Rwanda: Added Value and Challenges of Mixed Methods Approaches.” In Mixed Methods Research in Poverty and Vulnerability, 61–86. London: Springer.

- Dawson, Neil, Adrian Martin, and Thomas Sikor. 2016. “Green Revolution in Sub-Saharan Africa: Implications of Imposed Innovation for the Wellbeing of Rural Smallholders.” World Development 78: 204–218. doi: 10.1016/j.worlddev.2015.10.008

- de Lame, D. 2005. A Hill Among a Thousand: Transformations and Ruptures in Rural Rwanda. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press.

- de Sardan, Jean-Pierre Olivier. 1988. “Peasant Logics and Development Project Logics.” Sociologia Ruralis 28 (2-3): 216–226. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9523.1988.tb01040.x

- Doyal, Len, and Ian Gough. 1991. A Theory of Human Need. Basingstoke: Macmillan.

- Finnoff, Kade. 2015. “Decomposing Inequality and Poverty in Post-War Rwanda: The Roles of Gender, Education, Wealth and Location.” Development Southern Africa 32 (2): 209–228. doi: 10.1080/0376835X.2014.984375

- Freistein, Katja, and Bettina Mahlert. 2016. “The Potential for Tackling Inequality in the Sustainable Development Goals.” Third World Quarterly 37 (12): 2139–2155. doi: 10.1080/01436597.2016.1166945

- Gaynor, Niamh. 2014. “‘A Nation in a Hurry’: The Costs of Local Governance Reforms in Rwanda.” Review of African Political Economy 41 (sup1): S49–S63. doi: 10.1080/03056244.2014.976190

- Gough, Ian, and James A. McGregor (Eds.). (2007). Wellbeing in Developing Countries: From Theory to Research. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Harrison, Graham. 2016. “Rwanda: An Agrarian Developmental State?” Third World Quarterly 37 (2): 354–370. doi: 10.1080/01436597.2015.1058147

- Hasselskog, Malin. 2015. “Rwandan Developmental ‘Social Engineering’: What Does it Imply and How is it Displayed?” Progress in Development Studies 15 (2): 154–169. doi: 10.1177/1464993414565533

- Hasselskog, Malin. 2016. “Participation or what? Local experiences and perceptions of household performance contracting in Rwanda.” Forum for Development Studies 43 (2): 177–199. doi: 10.1080/08039410.2015.1090477

- Hasselskog, Malin. 2017. “A Capability Analysis of Rwandan Development Policy: Calling Into Question Human Development Indicators.” Third World Quarterly 39: 140–157.

- Holvoet, N., and H. Rombouts. 2008. “The Challenge of Monitoring and Evaluation Under the New aid Modalities: Experiences from Rwanda.” The Journal of Modern African Studies 46 (04): 577–602. doi: 10.1017/S0022278X08003492

- Ingelaere, B. 2011. “The Ruler’s Drum and the People’s Shout: Accountability and Representation on Rwanda’s Hills.” In Remaking Rwanda. State Building and Human Rights After Mass Violence, edited by S. Straus, and L. Waldorf, 67–78. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press.

- Ingelaere, Bert. 2014. “What’s on a Peasant’s Mind? Experiencing RPF State Reach and Overreach in Post-Genocide Rwanda (2000–10).” Journal of Eastern African Studies 8 (2): 214–230. doi: 10.1080/17531055.2014.891783

- Jackson, Dorothy, and Katrina Payne. 2003. Twa Women, Twa Rights in the Great Lakes Region of Africa. London: Minority Rights Group International.

- Kidd, Christopher. 2008. “Development Discourse and the Batwa of South West Uganda: Representing the ‘Other’: Presenting the ‘Self’.” PhD thesis., University of Glasgow, UK.

- Klapwijk, C. J., C. Bucagu, Mark T. van Wijk, H. M. J. Udo, B. Vanlauwe, E. Munyanziza, and Ken E. Giller. 2014. “The ‘One Cow per Poor Family’ Programme: Current and Potential Fodder Availability within Smallholder Farming Systems in Southwest Rwanda.” Agricultural Systems 131: 11–22. doi: 10.1016/j.agsy.2014.07.005

- Lewis, David, and David Mosse. 2006. Development Brokers and Translators: The Ethnography of aid and Agencies. West Hartford, CT: Kumarian Press.

- Mbonyinshuti, J. d’A. 2012. “‘Comment’.” New Times of Rwanda, 8th October 2012.

- McGregor, J. Allister, Andrew McKay, and Jackeline Velazco. 2007. “Needs and Resources in the Investigation of Well-Being in Developing Countries: Illustrative Evidence from Bangladesh and Peru.” Journal of Economic Methodology 14 (1): 107–131. doi: 10.1080/13501780601170115

- MINAGRI. 2011. Strategies for Sustainable Crop Intensification in Rwanda: Shifting Focus from Producing Enough to Producing Surplus, Rwandan Ministry of Agriculture Report, p.59, Kigali.

- Mosse, David. 2010. “A Relational Approach to Durable Poverty, Inequality and Power.” Journal of Development Studies 46 (7): 1156–1178. doi: 10.1080/00220388.2010.487095

- Newbury, C. 2011. “High Modernism at the Ground Level: The Imidugudu Policy in Rwanda.” In Reconstructing Rwanda: State Building & Human Rights after Mass Violence, edited by S. Straus, and L. Waldorf, 223–239. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press.

- NISR. 2012. The Evolution of Poverty in Rwanda from 2000 to 2011: Results from the Household Surveys. Kigali: National Institute of Statistics of Rwanda Report, p. 40

- OPHI. 2013. “Rwanda Country Briefing, Multidimensional Poverty Index Data Bank.” Oxford Poverty and Human Development Initiative, University of Oxford. Available at: www.ophi.org.uk/multidimensional-poverty-index/mpi-country-briefings/.

- Pogge, Thomas, and Mitu Sengupta. 2016. “Assessing the Sustainable Development Goals from a Human Rights Perspective.” Journal of International and Comparative Social Policy 32 (2): 83–97. doi: 10.1080/21699763.2016.1198268

- Pritchard, M. F. 2013. “Land, Power and Peace: Tenure Formalization, Agricultural Reform, and Livelihood Insecurity in Rural Rwanda.” Land Use Policy 30 (1): 186–196. doi: 10.1016/j.landusepol.2012.03.012

- Protopsaltis, Panayotis M. 2017. “Deciphering UN Development Policies: From the Modernisation Paradigm to the Human Development Approach?” Third World Quarterly 38: 1733–1752. doi:10.1080/01436597.2017.1298436.

- Purdeková, Andrea. 2008. “Building a Nation in Rwanda? De-Ethnicisation and its Discontents.” Studies in Ethnicity and Nationalism 8 (3): 502–523. doi: 10.1111/j.1754-9469.2008.00031.x

- Ravallion, Martin. 2011. “On Multidimensional Indices of Poverty.” The Journal of Economic Inequality 9 (2): 235–248. doi: 10.1007/s10888-011-9173-4

- Reyntjens, F. 2011. “Constructing the Truth, Dealing with Dissent, Domesticating the World: Governance in Post-Genocide Rwanda.” African Affairs 110 (438): 1–34. doi: 10.1093/afraf/adq075

- ROR. 2004. National Land Policy. Kigali: Republic of Rwanda Report, p. 54

- ROR. 2007. “Economic Development and Poverty Reduction Strategy, 2008–2012.” Ministry of Finance and Economic Planning. Republic of Rwanda (ROR), Kigali.

- Schraml, Carla. 2014. “How is Ethnicity Experienced? Essentialist and Constructivist Notions of Ethnicity in Rwanda and Burundi.” Ethnicities 14: 615–633. 1468796813519781. doi: 10.1177/1468796813519781

- Sen, A. 1999. Development as Freedom. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Shaffer, Paul. 2013. “Ten Years of ‘Q-Squared’: Implications for Understanding and Explaining Poverty.” World Development 45 (C): 269–285. doi: 10.1016/j.worlddev.2012.12.008

- Smith, Michael D., Matthew P. Rabbitt, and Alisha Coleman-Jensen. 2017. “Who are the World’s Food Insecure? New Evidence from the Food and Agriculture Organization’s Food Insecurity Experience Scale.” World Development 93: 402–412. doi: 10.1016/j.worlddev.2017.01.006

- UN. 2013. “MDG Report. Assessing Progress in Africa Toward the Millennium Development Goals.” United Nations Report.

- Van Damme, Julie, An Ansoms, and Philippe V. Baret. 2014. “Agricultural Innovation from Above and from Below: Confrontation and Integration on Rwanda’s Hills.” African Affairs 113 (450): 108–127. doi: 10.1093/afraf/adt067

- Waldorf, L. 2011. “Instrumentalising Genocide: The RPF’s Campaign Against ‘Genocide Ideology’.” In Reconstructing Rwanda: State Building & Human Rights after Mass Violence, edited by S. Straus, and L. Waldorf, 48–66. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press.

- WFP. 2012. Rwanda: Comprehensive Food Security and Vulnerability Analysis. Rome: World Food Programme Report, p. 126