ABSTRACT

The connections between WASH and gender equality have been extensively explored and documented using qualitative approaches, but not yet through quantitative means in ways that can strengthen WASH programming. The Water, Sanitation and Hygiene Gender Equality Measure (WASH-GEM) is a novel quantitative multidimensional tool co-produced in partnership between researchers and practitioners. This article explores three dimensions of the WASH-GEM co-production and implementation: (i) the role of partnerships in co-production processes for bringing contextual and practitioner knowledge into measure development; (ii) selected results from the validation pilot in Cambodia and Nepal (n = 3,056) that demonstrate ways in which the measure can inform WASH programming through analysis at different levels and with different co-variants; and (iii) the collaborative process of translating research into programming. The study illustrates that strong partnership and co-production processes were foundational for the development of a conceptually rigorous quantitative measure that has practical relevance. The findings presented in this article have implications for future measure development and WASH programming that aims to influence gender equality in rural communities.

Introduction

Water, sanitation, and hygiene (WASH) programs within low- and middle-income countries have shown potential as an entry point to address harmful traditional gender roles in household and community WASH, as well as wider gender equality dynamics (Carrard et al. Citation2013; MacArthur, Carrard, and Willetts Citation2021; Dickin et al. Citation2021; Caruso et al. Citation2021). In many contexts, women are typically responsible for cooking, cleaning, collecting water and caregiving, and men are typically responsible for the maintenance and repair of household systems and decision-making regarding new WASH systems (Mandara, Niehof, and van der Horst Citation2017; O’Reilly and Dreibelbis Citation2018).

In this context, and guided by country commitments to Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) 5 and 6, there are significant opportunities to strengthen gender equality through improvements in WASH and to improve WASH through gender equality (Willetts et al. Citation2010). Such modalities are known as gender-transformative approaches to WASH (MacArthur, Carrard, and Willetts Citation2020). Aiming to support the synergies between gender equality and WASH programming, initiatives such as the Water for Women Fund, have sought to engage the gender-WASH nexus. However, robust monitoring and evaluation of change at a programmatic level remain complex.

Following the Beijing Declaration and Platform for Action and initiation of the Millennium Development Goals, and more recently the SDGs, there has been an increase in approaches seeking to quantify development improvements to understand how policies, programs, and projects support and enable changes in gender equality (MacArthur, Carrard, and Willetts Citation2021). Such quantitative measures have created comparable datasets such as the Demographic and Health Surveys and the Joint Monitoring Programme for WASH. However, the translation of national measures to explore changes at a programmatic level remains difficult (Hancock Citation2010). Aiming to address the programmatic measurement gap, a variety of measures have been developed in the last decade, many aligned with the Women’s Empowerment in Agriculture Index (WEAI) (Alkire et al. Citation2013). These include the pro-WEAI (Malapit et al. Citation2019) and other sectoral-focused measures in livestock (Galiè et al. Citation2019), nutrition (Narayanan et al. Citation2019), and WASH.

Recently developed quantitative measures related to gender and WASH include the Empowerment in Water, Sanitation and Hygiene Index (EWI) (Dickin et al. Citation2021), the Agency, Resources and Institutional Structures for Sanitation-related Empowerment (ARISE) scale (Sinharoy et al. Citation2022), the Sanitation Insecurity Measure (Caruso et al. Citation2017), and the household water insecurity and women’s psychological distress measure (Stevenson et al. Citation2016). These measures each cover certain aspects of gender outcomes related to WASH; however, there is an opportunity to also examine both women’s and men’s perspectives of gender equality dimensions more broadly beyond WASH, with a mandate to explore how WASH programs can be an entry point to wider gender equality.

Additionally, despite this increase in programmatic measures, little has been written on the co-development of measures by researchers and local implementing partners and the opportunity to translate findings into actionable outcomes for program teams. This type of co-production is used in transdisciplinary (Mitchell, Cordell, and Fam Citation2015) and transformative (Mertens Citation2009) research and evaluation practice. Co-production by academics and non-academics has been asserted to support more relevant and effective research, which has a greater impact on sustainable development outcomes (Norstrom et al. Citation2020).

In this article, we describe and reflect on the co-production of a quantitative measure—the WASH-Gender Equality Measure (WASH-GEM)—designed to holistically investigate changes in gender equality through WASH programming. Founded on strong partnership and principles of co-production, the development and implementation of the WASH-GEM aimed to bring together WASH research and programming to achieve conceptual rigor, practical relevance, and potential for transformative outcomes for partners. The WASH-GEM was developed and piloted through a partnership between a research institute: the Institute for Sustainable Futures-University of Technology Sydney (ISF-UTS) and international implementing civil society organizations (CSO) partners: iDE in Cambodia and SNV in Nepal, both with a long-term presence in each country. The International Women’s Development Agency (IWDA) was also a partner, providing specialist support.

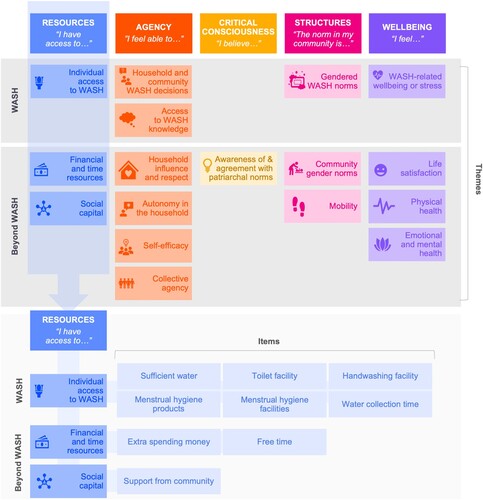

The WASH-GEM is informed by gender and development theory as elaborated in Carrard et al. Citation2022, and the evidence base on gender-WASH interactions (e.g. Fisher Citation2006; Caruso et al. Citation2017; Carrard et al. Citation2013; Fisher, Cavill, and Reed Citation2017). The WASH-GEM uses five domains of change—Resources, Agency, Critical Consciousness, Structures, and Wellbeing— which were identified through critical literature review and engagement with practitioners and specialists (see Carrard et al. Citation2022). The domains are discrete and complementary and are not combined into a single composite index. The WASH-GEM focuses on both women and men and overall gender dynamics, and in doing so, is not limited to a focus on women’s empowerment. The measure design recognizes that gender equality is contextual (Richardson Citation2018), and rather than setting specific thresholds and cut-off points as indicating certain levels of (dis)empowerment, (e.g. Malapit et al. Citation2019; Dickin et al. Citation2021), the WASH-GEM focuses primarily on comparisons between men and women within the same context. It can be used as a diagnostic tool, as described in this article, and is also intended to be used over time for comparison. The intention is to illuminate differences in women’s and men’s experiences and perspectives in relation to gendered aspects of WASH, and gender equality more broadly, and provide a basis for addressing and informing changes in practice.

This article has two main aims. Firstly, to demonstrate the importance and benefits of practitioner-researcher partnerships for co-production of a quantitative measure that is grounded, usable, and closes the gap between research and implementation. Secondly, to present illustrative results of the WASH-GEM validation pilot to demonstrate the different ways in which the measure can be used to collaboratively derive meaning and enhance research impact.

In this article, first, we detail the process of co-production and piloting of the WASH-GEM. Then we present qualitative reflections on the shared experience of working in partnership and the influence it had on the evolution of the measure and its use by CSOs. We then present illustrative quantitative results from the validation piloting phase and data-related insights from the WASH-GEM’s multiple levels, showing how the measure can be used collaboratively to explore important programmatic questions. This is followed by a description of the process of making sense of research findings, and finally, we present concluding remarks and pathways for future uptake and development of the measure.

Methods

Study contexts

Both iDE and SNV employ systems strengthening approaches in their WASH programs, and emphasize gender and social inclusion. iDE’s Sanitation Marketing Scale-Up Program 3 (SMSU3) is implemented in six provinces in Cambodia, focused on the sale of latrines and water filters, commercialization of rural fecal sludge management, and hygiene behavior change strategies. SNV’s Beyond the Finish Line program operates in two districts in Nepal, focused on improving the governance of rural water supply services, the performance of rural water supply implementers, and hygiene behavior change communication.

In Cambodia and Nepal, WASH and gender data illustrate the importance of ongoing efforts to strengthen service delivery and achieve equality. In Cambodia, in 2020, only 18% of the rural population had access to safely managed drinking water, and 61% had at least basic sanitation (WHO/UNICEF Citation2021). Meanwhile, Cambodia’s Gender Inequality Index (GII) score was 0.474, ranking it 117th out of 162 countries (UNDP Citation2020), reflecting the impact of poor health, empowerment, and economic status of women, compared to men. Traditional gender norms in Cambodia dictate that women are subordinate to men, and they are responsible for the majority of the housework including that related to WASH, such as water collection and cleaning; much of which is documented in the Cbpab Srei, the Code of Conduct for Women (Ledgerwood Citation1990).

Similarly, in Nepal, in 2020, only 16% of the rural population had access to safely managed drinking water, and 50% had safely managed sanitation services (WHO/UNICEF Citation2021). Additionally, Nepal’s GII score (0.452) ranked it 110th (UNDP Citation2020). In Nepal, women and girls bear the main burden of poor WASH services, being particularly vulnerable to water insecurity, as well as poor health and emotional and psychological distress (Wali et al. Citation2020).

Cambodia and Nepal have both achieved significant progress in increasing access to basic sanitation in the last five years (WHO/UNICEF Citation2021), with potential for associated improvements in gender equality, given women’s roles. However, these links require interrogation, which was made possible through the deployment of the WASH-GEM.

The WASH-GEM was piloted in five diverse locations: three provinces in Cambodia —Kampong Thom, Kandal, and Prey Veng— and two districts in Nepal —Dailekh and Sarlahi. Kampong Thom was the most remote of the three Cambodian provinces, and considerably less densely populated compared with Kandal and Prey Veng. Kandal is a peri-urban province that surrounds Phnom Penh, borders Vietnam, and is one of the wealthier provinces in the country. Prey Veng also borders Vietnam and is one of the least wealthy areas in Cambodia. Dailekh is in a mountainous region with limited road access, and many women face strong social restrictions during menstruation (chhaupadi) (Thakuri et al. Citation2021). Sarlahi is in the plains in the Terai region, neighboring India, and is more accessible than Dailekh.

Ethical approval was obtained from the University of Technology Sydney prior to data collection, and informed consent was obtained from all respondents prior to their participation.

Co-production of the WASH-GEM through partnership

Co-production was fundamental to the overall WASH-GEM approach, underpinning the measure design and exploration of its usefulness for WASH programming. Co-production refers to ‘iterative and collaborative processes involving diverse types of expertise, knowledge and actors to produce context-specific knowledge and pathways’ (Norstrom et al. Citation2020, 183). Our approach was based on an ethical commitment to integrating practical knowledge in shaping research priorities and conduct, which aligns with conceptions of co-production as challenging traditional knowledge hierarchies and offering a potentially transformative research method (Bell and Pahl Citation2017; Chambers et al. Citation2021). We also hoped that co-production would support the research to have an impact, such that the WASH-GEM would achieve development outcomes during its development and when used in the future.

Partnership in the context of the WASH-GEM refers to a formal arrangement between the research organization (ISF-UTS), the WASH-focused CSOs (iDE and SNV) and specialist CSO (IWDA). This arrangement comprised a common goal and shared resources, benefits and risks, as key pillars of partnerships in international development (Winterford Citation2017; Fransman and Newman Citation2019). The partnership involved formal contracts between organizations, which defined each organization’s roles and contributions. The partners came together at the proposal development stage and had pre-existing and long-standing collaborative relationships. Three core principles characteristic of strong partnerships guided the interactions, namely equity, transparency, and mutual benefit (Winterford Citation2017). Additionally, cognizant of power imbalances that can occur in Global South–North partnerships (Vincent et al. 2020), efforts were made to adhere to joint decision-making, and promote equitable participation and safe spaces for open dialogue.

The WASH-GEM was co-developed through a formative conceptual phase and three cycles of piloting: (i) rapid piloting (n = 80); (ii) exploratory piloting (n = 634); and (iii) validation piloting (n = 3,056). The co-development team comprised researchers and implementing CSOs, with input also sought from partners of the wider grant within which this work was conducted. Different members of the research and CSO teams were involved in different ways, such as defining overall aims and expectations, involvement in feedback loops, technical review, translation, study design, data collection, data analysis, and sensemaking, contributing to all stages of design, development, and implementation. This mode of collaboration leveraged the complementary strengths and knowledge-base of all partners and involved a commitment to ensure mutual learning.

Our aim was for the research partnership to be transformational rather than transactional. As such, it involved three key elements (Winterford Citation2017): (i) long-term commitment to the same goal, (ii) evolving ways of working and reflection processes, and (iii) shared power to make key decisions together. Our shared goal was to develop a robust measure of gender equality in WASH that was usable by project staff in international organizations, with meaningful findings for programming. With CSO partners as joint researchers, the WASH-GEM development benefited from their lived experiences and depth of contextual and technical knowledge.

The study was guided by recent evidence on approaches to facilitating research impact. A study of 130 development research projects identified knowledge co-production as a key facilitator of research impact (RDI Network Citation2017). Other facilitators were: familiarity and prior engagement with research context and users; influential outputs; intentional focus on impact and integrated methods for its achievement; and lasting engagement and continuity of relationships (ibid). In this article, we focus specifically on the first three. Firstly, how the partnership provided a depth of contextual knowledge and engagement with research end-users (CSOs) to inform the development and use of the WASH-GEM. Secondly, the role of partnership in designing outputs that are likely to be influential, including determining how to communicate the breadth of insights the tool can offer in ways that can influence the evolution of programming approaches. And thirdly, the application of deliberate research translation efforts to ensure research impact.

Implementing the WASH-GEM in communities

WASH-GEM findings shared in this article draw from the validation piloting phase (n = 3,056). The same survey tool was used in both countries with minor differences in one question.Footnote1 While the WASH-GEM did not demonstrate measurement invariance across contexts (MacArthur et al. Citationforthcoming), we examined differences in response patterns between countries, geographic locations, and genders to promote discussion and understanding of the tool and its use, and to facilitate its refinement. All data were collected face-to-face by the CSO enumerator teams in Nepali, Maithili, or Khmer language.

CSO enumerator teams were trained to implement the WASH-GEM, with training at each of the three phases of piloting. Training included tool overview, data collection methods, research ethics, and distress protocols. Data collection for the validation pilot was conducted between September and December 2020. The data collection approach involved both women and men enumerators, and gender-pairing when interviewing respondents. Refer to MacArthur et al. (Citationforthcoming) for further details on the sampling strategy.

Validation data were analyzed through univariate descriptive analysis to explore the distribution of responses. Bivariate analyses were then used to assess how response patterns varied between countries and by gender. Principal component analysis was conducted to develop a wealth index, generating wealth quintiles specific to this dataset. Cohen’s d effect sizes and unpaired t-tests were calculated for different co-variants to estimate and compare differences in the domain-, theme-, and item-level results. Lastly, correlation coefficients between WASH and Beyond-WASH subdomains were calculated using Pearson’s r. The data were analyzed using RStudio and Microsoft Excel. Further statistical analyses were conducted to assess the measure validity, described in detail in MacArthur et al. (Citationforthcoming).

Limitations

Although the COVID-19 pandemic did not pose major constraints to the research, adaptations were required to follow government recommendations and maintain the safety of the team and respondents. Some research activities were adapted to be conducted online, including the sensemaking and research translation processes, which were originally planned as a series of multi-day in-person workshops with wider CSO teams and local stakeholders. Instead, short workshops were held online only between ISF-UTS researchers and the CSO teams, limiting the time that could be dedicated to these processes. While the online nature of engagement influenced partnership dynamics, long-standing relationships between partners established prior to travel restrictions combined with a commitment to interactive, inclusive online processes ensured the partnership remained strong throughout the co-development process.

The potential for such a co-production approach to be replicated may be limited by traditional funding arrangements and contextual specificity. Building strong partnerships and engaging in co-production takes time and requires more resources relative to traditional producer-led research and projects (Vincent et al. 2020), and it is not always possible for practitioners and academics to access funding mechanisms that support this kind of partnership. Finally, the measure was developed for use in rural contexts in South Asia and may require adaptation to be used in other contexts. The findings presented in this article are specific to the study context and scope.

The role of contextual and CSO partner knowledge in the WASH-GEM design

In this section we explore the role of partnership and co-production processes in bringing contextual and CSO partner knowledge to measure development, outlining how participant and enumerator feedback shaped the design of the WASH-GEM. Three examples demonstrate the critical influence of CSO partners’ in-depth contextual knowledge in shaping measure development: the WASH-GEM’s approach to measuring self-efficacy, application of a do no harm approach, and tool refinement informed by enumerator reflections. Time was taken in the partnership to share ideas, challenges, and ways to make the research process and the measure more practical.

The WASH-GEM’s approach to measuring self-efficacy changed substantially during design in response to CSO partner input. Our starting point was to use the general self-efficacy scale, a reputable scale that is widely used, including in development contexts via its incorporation in the WEAI. During rapid piloting, CSO enumerator teams conducted qualitative interviews with participants after administering the survey as a form of cognitive testing. The enumerator teams repeatedly found that the generalized statements in this scale caused confusion and consternation. One such statement was: ‘I will be able to achieve most of the goals that I set for myself.’ Cognitive interviews revealed that the concept of ‘goals’ in abstract was not readily conveyed in the Cambodian and Nepalese contexts.

For the exploratory and validation phases, we modified statements to make them more easily understood (in this case: ‘It is easy for me to achieve the things I would like to do in my life’). In both phases, we again received feedback that such generalized statements, particularly those that used conditional tense, continued to be problematic. Based on self-efficacy literature (Bandura Citation1977; Donald et al. Citation2017), we formulated statements that were specific and focused on the idea of ‘confidence’ to do something (e.g. ‘How confident are you that you can discuss and change your household roles and responsibilities if you want to?’), which we termed the specific self-efficacy scale. We analyzed the internal consistency of the two scales (general and specific) using Cronbach’s alpha. The two scales performed almost identically (general scale ɑ = 0.85; specific scale ɑ = 0.84); however, due to recurrent challenges with general statements, we decided to remove the general self-efficacy scale. This was a difficult decision from a researcher perspective, since the use of widely respected, tested scales and tools is expected in academia, and there is uncertainty associated with new items and how they may perform in different contexts. This example provides insight into the tensions that arise in the joint development of a tool, and how the role of CSO partners and their feedback informed tool development.

In a second example, our jointly developed approach to research ethics comprised testing initial survey content with CSO partners regarding the principle of ‘do no harm’. The review of an initial draft tool resulted in feedback from specialist CSO partner, IWDA, about items that addressed violence against women (VAW). Since VAW has been associated with certain WASH situations such as safety in accessing latrines or when collecting water (Pommells et al. Citation2018), we had included items addressing this context. However, given the administration of the WASH-GEM with a man and a woman of the same household, it was deemed unsafe to prompt respondents to answer questions of this type, and hence the questions were removed. This experience highlights that successfully employing a do-no-harm approach requires deep contextual and technical knowledge to identify potential risks, which is best achieved through strong partnerships.

The third example relates to WASH-GEM refinement informed by participant and enumerator experiences. The WASH-GEM includes questions to enumerators after administering the survey, concerning participants’ comprehension and emotional responses. For example, in response to ‘Did the participant understand the questions?’ men demonstrated more difficulty (16% in Nepal responses ‘not much’ or ‘not at all’ and 13% in Cambodia) than women (6% in both countries). From this data and discussions with the field teams, we were able to identify questions causing difficulty and removed them as appropriate (for example, some questions related to mobility). In addition, the WASH-GEM implementation guidance materials (MacArthur, Gonzalez, and Willetts Citation2021) include suggestions to pay particular attention to the training of male enumerators and check their grasp of intended item meaning, to support improved understanding by male respondents.

In terms of emotional response among respondents, while 95% of respondents were fully or somewhat comfortable, enumerators noted that respondents with a disability became stressed and the distress protocol had to be followed. Despite the stress caused, these respondents were reported by enumerators to be motivated to participate so they could present different facts about their lives, challenging assumptions. As a result, within the WASH-GEM guidance materials (ibid), suggestions are made on implementing it with people with a disability and responding to participant distress.

A recurring challenge during all phases of piloting was the tension between developing a standardized tool and applicability across different contexts. Since gender equality is inherently contextual (Richardson Citation2018), and a quantitative measure is, by nature, reductionist, this is an important area for critical reflection. Compounding the challenge is the fact that gender equality concepts and meanings do not directly translate across languages, so a key component of WASH-GEM development involved deliberation between partners about how to convey intended meanings consistently in the translation of the survey tool. Many of the decisions made were compromises, based on an assessment that a ‘good enough’ fit would have the capacity to provide sufficiently meaningful data for program use, particularly when complemented by qualitative research tools, consistent with the WASH-GEM implementation guidance.

Deriving meaning from the different levels of the WASH-GEM: program-relevant results

The WASH-GEM is a layered measure, with data enabling examination of insights at different levels of aggregation, from item to domain level. Items are aggregated into themes, themes into WASH and Beyond-WASH subdomains, and subdomains to domains (). In this section, we present illustrative findings from the validation pilot to demonstrate how the WASH-GEM can be used by CSOs to explore insights at different levels. Significant discussion took place in the partnership to consider appropriate analyses, statistics, and programming needs to ensure meaningfulness and relevance to practice.

Figure 1. Visual representation of the different levels of the WASH-GEM, including items of the Resources domain.

Each domain is designed to be viewed as a discrete, important aspect of gender equality in the context of WASH, and not compensated for by achievements in other domains. As such, the WASH-GEM domains are not combined into a single index score and are not intended to be directly compared to one another. We considered this level of aggregation to be important and meaningful for understanding gender equality dynamics; however, it also inevitably simplifies a much more complex picture and can mask differences that may occur between women and men at the theme and the item levels. As such, we propose that the measure results for women and men be examined at each of these levels. Scores at all levels range from 0 to 1. The findings below demonstrate how meaning can be derived from analysis of WASH-GEM data including examination against co-variants such as level of education and wealth, reinforcing the arguments in intersectional discourse in WASH (Soeters et al. Citation2019).

The gender-disaggregated dataset included 3,054 respondents (1,496 in Cambodia and 1,558 in Nepal), of which 51% identified as women and 49% as men. Respondents had different levels of education, (41% pre-school or below, 36% primary, and 23% secondary or higherFootnote2). Almost all respondents were married or living together (93%), and 63% of respondents were interviewed as part of a dyad (a man and woman of the same household interviewed separately). Twenty-two per cent of respondents reported someone in their household lived with a disability. Refer to MacArthur et al. (Citationforthcoming) for details of the sociodemographic characteristics of respondents.

Domain-level findings

A strength of the WASH-GEM is that it readily enables overall comparisons (e.g. by country, gender, geographic region) and deconstruction to reveal the circumstances influencing these findings. Here we present findings at the domain level, and where appropriate, identify key drivers of outcomes at a different level (e.g. theme or item).

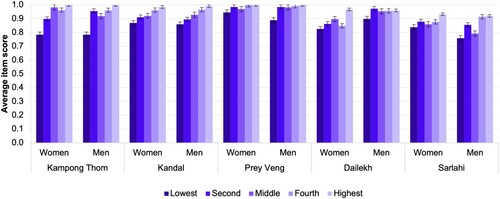

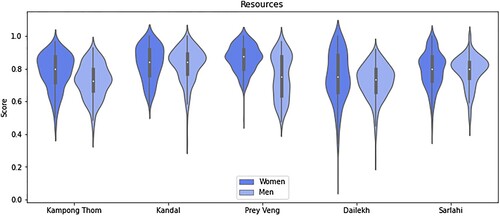

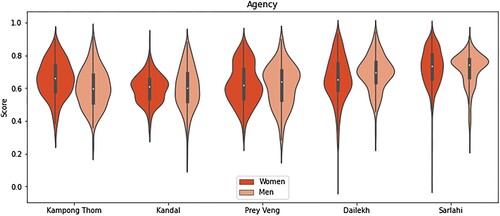

presents the average score for each domain by gender, country and province/district. Refer to supplementary material for violin plots of this data.

Table 1. Average domain scores by gender, country, and province/district. Darker colors represent higher scores within each domain.

The Resources domain explored ownership, access and use of material, human and social resources (Carrard et al. Citation2022). The results showed that on average, women in Cambodia had significantly higher domain scores than men (0.83 and 0.77, respectively), particularly in the province of Prey Veng (0.86 for women and 0.75 for men), which appeared to be due to reporting having more free time and spending less time collecting water. In Nepal, women also had higher or similar average domain scores when compared to men, with slightly higher scores observed in Sarlahi district, which aligns to the higher socioeconomic context in Sarlahi as compared to Dailekh.

Agency was defined as the ability to set goals and act upon them. The Agency domain explored respondents’ decision-making and self-confidence (Carrard et al. Citation2022). Scores were similar between men and women from the same country and province/district, except for Kampong Thom. In this province, on average, women had higher scores than men (0.66 and 0.60 respectively), driven mainly by women’s higher collective agency scores, compared to men. These included belonging to community groups and confidence in their decision-making within those groups.

The Structures domain focused on the formal and informal rules of society and gender norms (Carrard et al. Citation2022). Women in Cambodia, on average, perceived social structures to be somewhat more gender-equal than did Cambodian men (scores of 0.57 and 0.53, respectively), and mainly influenced by women’s scores in Kandal and Prey Veng. However, these scores are in the mid-range (out of a possible maximum of 1.0), indicating a significant opportunity to strengthen Structures as an enabler of gender equality for both women and men. In contrast, in Nepal, women appeared to perceive gendered structures as notably more unequal than men did (0.39 compared to 0.51 respectively).

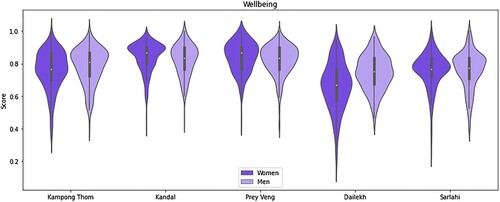

Wellbeing explored the health, safety, and comfort of individuals (Carrard et al. Citation2022). The average Wellbeing domain scores in Cambodia were the same for women and men (0.81), while in Nepal, the average score for men overall (0.75) was slightly higher than for women (0.72), mainly driven by results observed in Dailekh district.

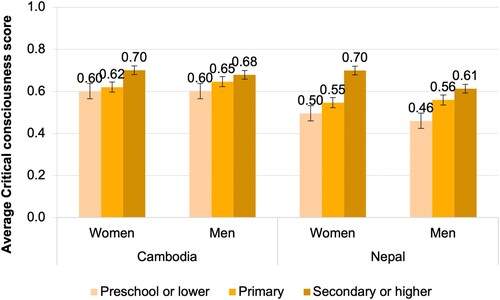

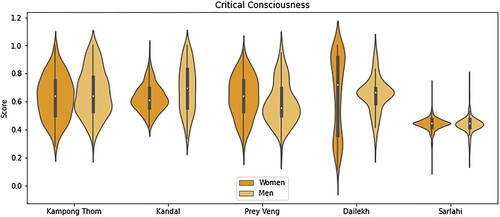

Critical consciousness refers to being aware of the gender inequalities that exist within society and believing they can be changed (Carrard et al. Citation2022). This domain explored perceptions, attitudes, and beliefs around adherence to patriarchal norms related to education, gender roles, rights, and opportunities for women and men. At a country and subnational level, average domain scores were similar between women and men from the same locations, except for Kandal and Prey Veng, with men’s average score significantly higher than women’s.

The WASH-GEM data can be explored using different co-variants to provide insights at different levels and for different demographics. We found that the respondents’ education level had the strongest association with Critical Consciousness scores (Cohen’s d = 0.948, p < 0.001). The average domain results were higher among women and men with higher levels of education (). Additionally, secondary educated women had slightly higher average scores than men in both countries.

WASH and beyond-WASH subdomain-level findings

The second level of the measure is the WASH and Beyond-WASH subdomains. The Beyond-WASH subdomain explores gender dynamics that relate to gender equality more broadly than just WASH. There were strong associations between WASH and Beyond-WASH subdomains in all the domains; however, the strongest associations were observed in relation to Agency.

We observed positive associations between Agency WASH and Beyond-WASH subdomains among men in all locations (Kampong Thom: r = 0.54, p < 0.001; Kandal: r = 0.47, p < 0.001; Prey Veng: r = 0.62, p < 0.001; Dailekh: r = 0.55, p < 0.001; Sarlahi: r = 0.52, p < 0.001), and among women in Prey Veng (r = 0.42, p < 0.001), Dailekh (r = 0.45, p < 0.001), and Sarlahi (r = 0.65, p < 0.001). These results indicated a close connection between the two aspects of Agency, confirming that they reinforce one another. For example, improving WASH-related decision-making at home and in the community may lead to increased Agency in other aspects of life (e.g. autonomy in the household, collective action, self-efficacy), and vice versa.

Understanding these distinct components of Agency could also be useful when comparing baseline and endline data, to help discern whether and to what extent program activities have contributed to improvements in agency specifically linked to WASH activities and to wider changes in agency in other areas of life.

Theme-level findings

Each WASH or Beyond-WASH subdomain consists of between one and four themes. Exploring theme-level findings illuminates factors influencing the domain-level results and can reveal gender dynamics that are not evident at the domain-level aggregation. We explore two themes: individual access to WASH and self-efficacy.

Individual access to WASH is a foundational theme to understanding the context and dynamics of WASH and gender. In comparing women’s and men’s average theme scores, we observed similar average scores for women and men in Nepal (0.86 and 0.88 respectively), and Cambodia (0.95 and 0.94 respectively). This is an encouraging result from a gender equality perspective. The WASH-GEM’s focus on the extent to which individual WASH needs are met differs from other typical sector global monitoring methods, which focus on household-level access and may obscure gendered differences.

We explored individual access to WASH by wealth quintile, as wealth had the strongest association with the theme (d = 0.56, p < 0.001), and found that the average theme scores were positively associated with higher levels of wealth for both women and men; however, as overall access to WASH was high, the increases were relatively minor. Insights derived from these types of findings could inform WASH strategies to ensure both women’s and men’s individual WASH needs are met across different socio-economic circumstances. In situations where WASH access is relatively high across gender and wealth categories, low WASH access scores might serve as a flag indicating relatively anomalous circumstances that might be associated with other risk factors.

The second theme we explore is self-efficacy (Agency domain). Self-efficacy refers to a person’s confidence in their ability to successfully perform certain behaviors required to produce desired outcomes (Bandura Citation1977), including self-confidence related to changing roles and responsibilities in the household and beyond, ability to solve problems in the household and beyond, and decision-making. Lower average Agency domain scores among respondents in Cambodia were driven by low self-efficacy theme scores. Exploring the theme in more detail, at the items level, we found that this was driven specifically by items beyond the household, where both women and men felt less confident in their ability to take on new roles in the community or the workplace, and their ability to help solve problems in their community.

Item-level findings

Each theme consists of one to eight items, or individual questions. Using selected items, we illustrate the insights that are possible by analyzing results at this level.

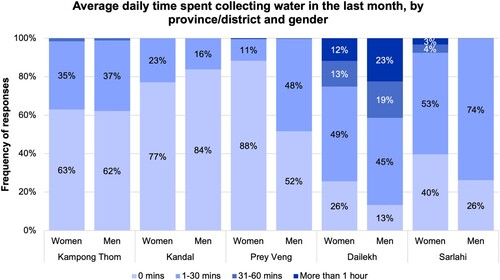

Gendered aspects of water collection are widely discussed in the WASH sector, and our results suggest that having nuanced data about different contexts is important. The results on time spent on water collection highlighted differences between men and women in Dailekh, Prey Veng, and Sarlahi, where men reported spending more time collecting water than women (), which is recorded in some studies (e.g. Geere and Cortobius Citation2017). Men and women in Dailekh spent the most time collecting water, partly driven by lower access levels and older male respondents noting long collection times.

An item in the Structures domain asked respondents how many people they knew thought that water collection was women’s responsibility. Aligned to the results above, this item revealed that in both countries, women thought that water collection was only women’s responsibility more often than men thought it was. Combining item-level data about practices and perceived norms in this way opens the opportunity to identify different lived experiences, create opportunities for conversations about adjusting roles and responsibilities supported by evidence, and to identify shared infrastructure priorities.

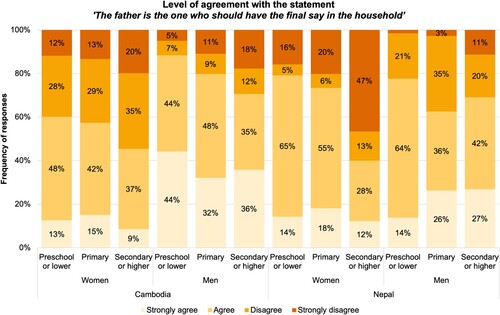

WASH programs commonly include a focus on supporting women's involvement in decision-making, including within the household. WASH-GEM data showed that in both countries it was more common for women than men to disagree with a statement that the father should have the final say in the household, and it was more common for higher-educated women to disagree (). Such insights from the WASH-GEM can inform targeted efforts to shift norms and power concerning decision-making at the household level.

Figure 4. It was more common for higher-educated women than men to disagree with the statement ‘the father is the one who should have the final say in the household.’

To further illustrate how the WASH-GEM can reveal links between WASH and other aspects of women’s and men’s lives, we compared two items concerning care work, one from Structures and one from Critical Consciousness. These items enable exploration of the relationship between what community members see as accepted social norms and their views about how things ‘should’ be.

We found important gendered distinctions between the perceived and desired care work norms. The Structures item showed that the perceived social norm was unequal, especially in the views of women in Nepal (79% reported that everyone or most people they knew thought household care work should be done by women, compared to 60% of men). In Cambodia, it was 47% of women and 44% of men. However, the related Critical Consciousness item results showed strong aspirations in both countries for a more equal share of household care work responsibilities. This was especially true among men in Cambodia (68% strongly agree, compared to 41% of women in Cambodia; and in Nepal, 31% of women and only 18% of men). These insights could be used to create a permissive space for dialogue about the shared desire for different, more equal arrangements, and decisions about ways to work towards them.

Lastly, we present an item from the Wellbeing domain concerned with how often respondents felt safe when accessing their toilet. The results showed that the levels of safety were generally high for both women and men. We found that wealth was strongly associated with Wellbeing scores (d = 0.73, p < 0.001), and we observed a positive association between wealth levels and safety when accessing toilets (). Kampong Thom, a remote province, showed a large difference in safety scores between the lowest and the highest wealth quintiles for both men and women. From a WASH programming and gender perspective, these results demonstrate the importance of understanding how women and men experience sanitation safety differently, and that sanitation safety is a relevant issue for both genders.

Figure 5. Higher levels of wealth were associated with a greater sense of safety among women and men when accessing their toilets.

Insights from validation findings are important to inform program strategies and as entry points for encouraging wider social change through WASH programs in communities. For example, these findings, complemented by qualitative social dynamics research, could open discussions about the extent to which the data reflects different experiences for men and women. Discussions in gender-specific groups might then identify potential areas for positive change. Ideas might then be presented and discussed in mixed groups to identify shared priorities. The data could also be used to inform activities that explore assumed gendered roles and norms in WASH, enabling participants to question their assumptions about norms and whether in the future things could work differently.

In this section we have demonstrated how to use the WASH-GEM as a diagnostic tool across the study locations in Cambodia and Nepal, highlighting the importance of intersectional and intrahousehold insights. We have also demonstrated that the WASH-GEM enables both higher-level insights and nuanced information, ensuring that crucial insights are not obscured by a single aggregation of results, and providing a deeper understanding of complex social and gender dynamics, within households and communities.

Sensemaking and research translation for WASH program implementation

Research translation was a priority to ensure the WASH-GEM provided meaningful data to inform SNV’s and iDE’s WASH programs. In the context of international development research, the concept of translation was defined by Mosse and Lewis (Citation2006, 13) as ‘mutual enrolment and the interlocking interests that produce project realities.’

The strategies implemented to support research translation were: (i) ensuring that the insights derived from the data could be easily interpreted by all stakeholders; (ii) understanding existing CSO program activities and their potential to influence gender equality; and (iii) drawing on insights from the data to propose and prioritize concrete program actions. These strategies were designed to support research impact, moving from research insights to WASH programming, and beyond.

Communicating statistical results from a multidimensional measure that explored complex gender dynamics without losing meaning or trespassing technical terms was challenging. We worked closely and iteratively with experienced practitioners at IWDA and statistics specialists to ensure that the different approaches to developing accessible visual representations conveyed the intended meaning and maintained scientific integrity. For example, in trying to communicate the ‘effect size’ and ‘statistical significance’ of scores to a non-specialist audience, we worked through different language options (ultimately using terms from ‘strong’ to ‘negligible’ associations as both clear and correct) and used heat maps to help visualize results.

The iterative process and close collaboration among partners ensured that the WASH-GEM findings shared with non-specialist audiences were engaging and had been distilled to the essential messages while maintaining the integrity of the data. An important component of this was data visualization, telling a story through data, and following principles of analytical design (Tufte Citation2001, Citation2006). We tested different types of charts and strategically used colors to draw attention to key results and prompt comparisons within locations, between genders and co-variants, while discouraging comparisons between domains. Visual representations were always accompanied by summaries that captured the key message in each chart and highlighted key questions for sensemaking.

The second and third strategies were implemented through online workshops facilitated by ISF-UTS with iDE and SNV staff, which purposely included a mix of gender and social inclusion specialists, monitoring and evaluation staff, field staff, and program managers and leadership. One aim of the sensemaking and research translation workshops was to derive meaning from results within context, theory, and sector knowledge. This was a two-way sensemaking process, with CSOs sharing their knowledge of the country context, and researchers situating the results within the theory.

The workshops also aimed to facilitate small group brainstorming and prioritization of specific actions linked to the findings, using the framework of spheres of control, influence, and concern. Discussions and outcomes were documented in post-workshop reports shared with participants.

The workshops with SNV and iDE were held separately and focused on exploring the findings from each country and identifying related short-term actions. For SNV, the workshops and overall involvement in the study resulted in the team being more sensitized to gender equality issues, through an encouraging learning and sharing process. The workshops also motivated the SNV team to share and validate findings with local partners, and more widely within the organization. For example, SNV identified that item findings related to menstrual hygiene management (MHM) were useful for validating their programmatic focus on improving MHM. Involvement in the WASH-GEM study, and other complementary research and evaluation activities, contributed to SNV’s development of training modules for women entrepreneurs to sell MHM products in schools and develop their leadership skills.

For iDE, the workshop reports were shared with the broader leadership team and provided a basis for further discussion and prioritization of specific short-term activities. For example, the WASH-GEM showed that on average, women latrine business owners (LBO) had lower Agency scores compared to men LBO (0.70 and 0.78 respectively). Women LBO consistently reported lower levels of self-confidence in the household (e.g. only 18% reported feeling very confident to change their household roles and responsibilities; in problem-solving; and having the power to make important decisions, compared to 50% of men). This was a finding that iDE addressed by refining its approach to fostering gender equality with LBOs. iDE’s program has prioritized ongoing capacity building support and greater consciousness of language during interactions. One such example is for iDE staff to avoid terms such as ‘LBO wife’ to refer to the LBO women entrepreneurs, which could hinder their self-confidence and agency.

In another example from Cambodia, WASH-GEM data showed that although there were high levels of access to MHM products and facilities, 17% of women in Prey Veng reported experiencing severe stress from managing their menstruation. In response, iDE updated its annual staff gender mainstreaming training to include an MHM component, to increase awareness and enable open conversations between men and women. iDE will also launch a training directed at women change agents, which will include MHM content. These decisions were underpinned by the WASH-GEM data and research discussions.

Encouraging a diverse mix of participants in the sensemaking and research translation workshops required ensuring that the process was inclusive, and that language and level of experience were not barriers to participation and engagement. This was addressed by ensuring that there was at least one group in which discussions were held in the participants’ first language and limiting the use of highly technical terminology that required expert knowledge and would not be easily translatable.

Overall, the sensemaking and research translation processes were mutually beneficial, supporting learning and complementarity of expertise while highlighting the transformative power of research. Through this process, the partners developed skills for knowledge co-production and research uptake. The researchers improved their research communication strategies, while the CSOs strengthened their evidence-based decision-making and planning processes.

Upon further critical reflection, we acknowledge that the sensemaking and research translation processes would have benefitted from more time to fully engage with the volume and depth of data generated and to better understand the contexts. We have observed that, in general, the time allocated to these processes can be underestimated and disproportionate to the time and resources invested in data collection, and a shift to allocating more resources to sensemaking and translation is recommended. Additionally, translating the insights from data into programming was highlighted as a critically important step by CSO program teams. Lastly, a recommendation to have specific hypotheses to test during sensemaking processes can be beneficial to ensure the process remains focused and efficient.

Through this partnership, the CSO teams have acquired new knowledge and expertise that can be applied in other WASH programs. The planned next phase of the WASH-GEM is to expand its implementation by SNV to Lao PDR and Bhutan, and by iDE to Ghana and Bangladesh, and co-develop open-access training and support materials for field teams, setting up pathways for future uptake.

Conclusions

This article has demonstrated the benefits of adopting a partnership and co-production approach to the development of a quantitative measure that is contextually grounded, relevant, usable, and well-placed to enable research impact. Contextual knowledge of civil society implementing partners complemented the technical expertise of a research institute to enable field-based collaborative development and use of the WASH-GEM. The unique contexts of Cambodia and Nepal, with varying gender and WASH dynamics, provided valuable case studies through which to demonstrate the useability of the measure to inform a range of programming decisions. Specifically designed research translation processes supported the use of the findings to inform WASH program implementation. At the time of writing, the measure is being adopted by additional partners to monitor and evaluate gender outcomes within WASH programming in other countries, towards wider global uptake with the aim of supporting strengthened gender outcomes from WASH programs. The WASH-GEM has proved to be a valuable tool to identify priorities and specific spaces and opportunities for change – key information for those working to accelerate action towards the SDGs.

Appendices

Violin plots of domain scores by province/district and gender

Appendices figures

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the participants in Cambodia and Nepal for generously sharing their time and experiences with the team.

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 The only required minor adaptation was concerning legal marriage age (20 in Nepal, and 18 in Cambodia).

2 The survey item included seven education categories identified in collaboration with CSO partners, however, for simplicity of analysis, these were grouped into three overarching categories.

References

- Alkire, S., R. Meinzen-Dick, A. Peterman, A. R. Quisumbing, G. Seymour, and A. Vaz. 2013. “The Women’s Empowerment in Agriculture Index.” World Development 52: 71–91. doi:10.1016/j.worlddev.2013.06.007.

- Bandura, A. 1977. “Self-efficacy: Toward a Unifying Theory of Behavioral Change.” Psychological Review 84 (2): 191–215. doi:10.1037/0033-295X.84.2.191.

- Bell, D. M., and K. Pahl. 2017. “Co-Production: Towards a Utopian Approach.” International Journal of Social Research Methodology 21 (1): 105–117. doi:10.1080/13645579.2017.1348581.

- Carrard, N., J. Crawford, G. Halcrow, C. Rowland, and J. Willetts. 2013. “A Framework for Exploring Gender Equality Outcomes from WASH Programmes.” Waterlines 32 (4): 315–333. doi:10.3362/1756-3488.2013.033.

- Carrard, N., J. MacArthur, C. Leahy, S. Soeters, and J. Willetts. 2022. “The Water, Sanitation and Hygiene Gender Equality Measure (WASH-GEM): Conceptual Foundations and Domains of Change.” Women’s Studies International Forum 91, doi:10.1016/j.wsif.2022.102563.

- Caruso, B. A., T. Clasen, K. M. Yount, H. L. F. Cooper, C. Hadley, and R. Haardörfer. 2017. “Assessing Women’s Negative Sanitation Experiences and Concerns: The Development of a Novel Sanitation Insecurity Measure.” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 14 (7): 755. doi:10.3390/ijerph14070755.

- Caruso, B. A., A. Conrad, M. Patrick, A. Owens, K. Kviten, O. Zarella, H. Rogers, and S. S. Sinharoy. 2021. “Water, Sanitation, and Women’s Empowerment: A systematic review and qualitative metasynthesis.” medRxiv [Preprint]. doi:10.1101/2021.10.26.21265535.

- Chambers, J. M., C. Wyborn, M. E. Ryan, R. S. Reid, M. Riechers, A. Serban, N. J. Bennett, et al. 2021. “Six Modes of co-Production for Sustainability.” Nat Sustain 4: 983–996. doi:10.1038/s41893-021-00755-x.

- Dickin, S., E. Bisung, J. Nansi, and K. Charles. 2021. “Empowerment in Water, Sanitation and Hygiene Index.” World Development 137: 105158. doi:10.1016/j.worlddev.2020.105158.

- Donald, A., G. Koolwal, J. Annan, K. Falb, and M. Goldstein. 2017. Measuring Women’s Agency. Policy Research Working Paper No. 8148. Washington DC: World Bank. http://hdl.handle.net/10986/27955.

- Fisher, J. 2006. For her it’s the big issue: Putting women at the centre of water supply, sanitation and hygiene. Water Supply and Sanitation Collaborative Council. https://www.wsscc.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/For-Her-Its-the-Big-Issue-Putting-Women-at-the-centre-of-Water-Supply-Sanitation-and-Hygiene-WASH-Evidence-Report.pdf.

- Fisher, J., S. Cavill, and B. Reed. 2017. “Mainstreaming Gender in the WASH Sector: Dilution or Distillation?” Gender and Development 25 (2): 185–204. doi:10.1080/13552074.2017.1331541.

- Fransman, J., and K. Newman. 2019. “Rethinking Research Partnerships: Evidence and the Politics of Participation in Research Partnerships for International Development.” Journal of International Development 31 (7): 523–544. doi:10.1002/jid.3417.

- Galiè, A., N. Teufel, L. Korir, I. Baltenweck, A. Webb Girard, P. Dominguez-Salas, and K. M. Yount. 2019. “The Women’s Empowerment in Livestock Index.” Social Indicators Research 142 (2): 799–825. doi:10.1007/s11205-018-1934-z.

- Geere, J. A., and M. Cortobius. 2017. “Who Carries the Weight of Water? Fetching Water in Rural and Urban Areas and the Implications for Water Security.” Water Alternatives 10 (2): 513–540. http://www.water-alternatives.org/index.php/alldoc/articles/vol10/v10issue2/368-a10-2-18/file.

- Hancock, P. 2010. “The Utility of Qualitative Research: A Study of Gender Empowerment in Sri Lanka.” Studies in Qualitative Methodology 9 (9): 177–195. doi:10.1016/S1042-3192(07)00207-8.

- Ledgerwood, J. 1990. “Changing Khmer Conceptions of Gender: Women, Stories, and the Social Order”. PhD diss., Cornell University. ProQuest Dissertations Publishing.

- MacArthur, J., N. Carrard, and J. Willetts. 2020. “WASH and Gender: A Critical Review of the Literature and Implications for Gender-Transformative WASH Research.” Journal of Water Sanitation and Hygiene for Development 10 (4): 818–827. doi:10.2166/washdev.2020.232.

- MacArthur, J., N. Carrard, and J. Willetts. 2021. “Exploring Gendered Change: Concepts and Trends in Gender Equality Assessments.” Third World Quarterly 42 (9): 2189–2208. doi:10.1080/01436597.2021.1911636.

- MacArthur, J., R. P. Chase, D. Gonzalez, T. Kozole, C. Nicoletti, V. Toeur, J. Willetts, et al. Forthcoming. “Investigating impacts of gender-transformative interventions in water, sanitation, and hygiene: The water, sanitation, and hygiene – gender equality measure (WASH-GEM).

- MacArthur, J., D. Gonzalez, and J. Willetts. 2021. “Using the WASH-GEM: Guidance Document.” Institute for Sustainable Futures – University of Technology Sydney, Sydney. https://multisitestaticcontent.uts.edu.au/wp-content/uploads/sites/57/2021/12/15095111/ISF-UTS-WASH-GEM-Guidance.pdf.

- Malapit, H., A. Quisumbing, R. Meinzen-Dick, G. Seymour, E. M. Martinez, J. Heckert, D. Rubin, A. Vaz, and K. M. Yount. 2019. “Development of the Project-Level Women’s Empowerment in Agriculture Index (pro-WEAI).” World Development 122: 675–692.

- Mandara, C. G., A. Niehof, and H. van der Horst. 2017. “Women and Rural Water Management: Token Representatives or Paving the Way to Power?” Water Alternatives 10 (1): 116–133.

- Mertens, D. M. 2009. Transformative Research and Evaluation. New York: Guilford Press.

- Mitchell, C., D. Cordell, and D. Fam. 2015. “Beginning at the end: The Outcome Spaces Framework to Guide Purposive Transdisciplinary Research.” Futures 65: 86–96. doi:10.1016/j.futures.2014.10.007.

- Mosse, D., and D. Lewis. 2006. “Theoretical Approaches to Brokerage and Translation in Development.” In Development Brokers and Translators: The Ethnography of Aid and Agencies, edited by David Lewis, and David Mosse, 1–26. Bloomfield, CT: Kumarian Books.

- Narayanan, S., E. Lentz, M. Fontana, A. De, and B. Kulkarni. 2019. “Developing the Women’s Empowerment in Nutrition Index in Two States of India.” Food Policy 89: 101780. doi:10.1016/j.foodpol.2019.101780.

- Norstrom, A., C. Cvitanovic, M. F. Lof, S. West, C. Wyborn, P. Balvanera, A. T. Bednarek, et al. 2020. “Principles for Knowledge co-Production in Sustainability Research.” Nature Sustainability 3: 182–190. doi:10.1038/s41893-019-0448-2.

- O’Reilly, K., and R. Dreibelbis. 2018. “WASH and Gender: Understanding Gendered Consequences and Impacts of WASH In/Security.” In Equality in Water and Sanitation Services Vol 1, edited by Oliver Cumming, and Tom Slaymaker, 80–90. London: Routledge. https://doi-org.ezproxy.lib.uts.edu.au/10.4324/9781315471532.

- Pommells, M., C. Schuster-Wallace, S. Watt, and Z. Mulawa. 2018. “Gender Violence as a Water, Sanitation, and Hygiene Risk: Uncovering Violence Against Women and Girls as It Pertains to Poor WaSH Access.” Violence Against Women 24 (15): 1851–1862. doi:10.1177/2F1077801218754410.

- RDI Network (Research for Development Impact Network). 2017. From Evidence to Impact: Development contribution of Australian Aid funded research: A study based on research undertaken through the Australian Development Research Awards Scheme 2007–2016. https://rdinetwork.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/From-Evidence-to-Impact-Full-Report.pdf.

- Richardson, R. A. 2018. “Measuring Women’s Empowerment: A Critical Review of Current Practices and Recommendations for Researchers.” Social Indicators Research 137: 539–557. doi:10.1007/s11205-017-1622-4.

- Sinharoy, S. S., A. Conrad, M. Patrick, S. McManus, and B. A. Caruso. 2022. “Protocol for Development and Validation of Instruments to Measure Women’s Empowerment in Urban Sanitation Across Countries in South Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa: The Agency, Resources and Institutional Structures for Sanitation-Related Empowerment (ARISE) Scales.” BMJ Open 12: e053104. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2021-053104.

- Soeters, S., M. Grant, N. Carrard, and J. Willetts. 2019. Intersectionality: ask the other question. Water for Women: Gender in WASH - Conversational article 2, Institute for Sustainable Futures, University of Technology Sydney.

- Stevenson, E. G. J., A. Ambelu, B. A. Caruso, Y. Tesfaye, and M. C. Freeman. 2016. “Community Water Improvement, Household Water Insecurity, and Women’s Psychological Distress: An Intervention and Control Study in Ethiopia.” PLoS One 11 (4), doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0153432.

- Thakuri, D. S., R. K. Thapa, S. Singh, G. N. Khanal, and R. B. Khatri. 2021. “A Harmful Religio-Cultural Practice (Chhaupadi) During Menstruation Among Adolescent Girls in Nepal: Prevalence and Policies for Eradication.” PLoS ONE 16 (9): e0256968. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0256968.

- Tufte, E. R. 2001. The Visual Display of Quantitative Information 2nd ed. Cheshire: Graphics Press.

- Tufte, E. R. 2006. Beautiful Evidence. Cheshire: Graphics Press.

- UNDP (United Nations Development Programme). 2020. Human Development Report. The Next Frontier: Human Development and the Anthropocene. New York. ISBN: 978-92-1-126442-5. http://hdr.undp.org/sites/default/files/hdr2020.pdf.

- Vincent, K., S. Carter, A. Steynor, E. Visman, and K. Lund Wågsæther. 2020. “Addressing Power Imbalances in Co-Production.” Nature Climate Change 10 (10): 877–878.

- Wali, N., N. Georgeou, O. Simmons, M. S. Gautam, and S. Gurung. 2020. “Women and WASH in Nepal: A Scoping Review of Existing Literature.” Water International 45 (3): 222–245. doi:10.1080/02508060.2020.1754564.

- WHO/UNICEF (World Health Organization and the United Nations Children’s Fund). 2021. Progress on household drinking water, sanitation and hygiene 2000-2020: Five years into the SDGs. Geneva. https://washdata.org/sites/default/files/2021-07/jmp-2021-wash-households.pdf.

- Willetts, J., G. Halcrow, N. Carrard, C. Rowland, and J. Crawford. 2010. “Addressing two Critical MDGs Together: Gender in Water, Sanitation and Hygiene Initiatives.” Pacific Economic Bulletin 25 (1): 211–221. http://hdl.handle.net/1885/30589.

- Winterford, K. 2017. How to Partner for Development Research. Research For Development Impact Network, Canberra, Australia. https://rdinetwork.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/How-to-Partner-for-Development-Research_fv_Web.pdf.