?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

The inflow of foreign direct investment (FDI) worldwide, especially in European countries, suffered a steep fall due to the rapid spread of the COVID-19 virus. This article is the first effort to empirically investigate the nexus between digital transformation and FDI inflows, thereby finding a way to help countries overcome the current situation. Using the data of 23 European countries pre-COVID (2015–2019) and during the COVID health crisis (2020), we demonstrate a nonlinear relationship between digitalization and FDI inflows, implying that a certain extent of digital transformation could promote the inflows of FDI. Before the COVID-19 health crisis, digital business played a critical role in attracting FDI inflows. E-commercial activities also enhanced FDI flows during the spread of the COVID-19 pandemic, and digital public services may be an effective tool to help countries overcome the health crisis. Furthermore, digitalization plays a critical role in promoting FDI inflows in both the short term and long term. Hence, digital transformation is an inevitable process that countries need to embrace in order to overcome the challenges of the COVID-19 pandemic and resolve the delay or lack of foreign investments.

1. Introduction

In 2020, the world witnessed a global catastrophe. The coronavirus (COVID-19), which first appeared in Wuhan, China, quickly spread to many other countries. The World Health Organization (WHO) officially declared a pandemic on 11 March 2020 (Jebril Citation2020; Sohrabi et al. Citation2020). To slow the spread of the coronavirus, many countries around the world have implemented extraordinary measures, including social distancing and lockdowns to save lives, as well as many other measures to support businesses. Many countries have announced the closure of major cities or even entire countries, and banned foreigners from crossing their borders. These restrictive measures have severely damaged the global economy (Hayakawa and Mukunoki Citation2021), which experienced an unprecedented sharp contraction in 2020 (Guerrieri et al. Citation2020). Earlier experts, such as Daszak (Citation2012), Ford et al. (Citation2009), and Webster (Citation1997), predicted that the global pandemic would place severe strains on components of global supply chains, directly affecting capital flows between countries.

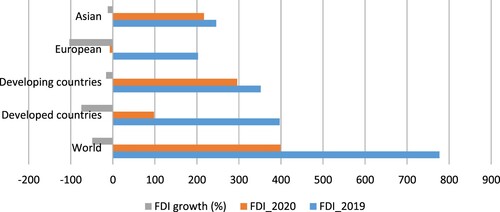

It is widely affirmed that FDI is a significant determinant of economic progress. FDI can significantly contribute to the sustainable development of both home and host countries in a number of important ways, according to a study published in ESCAP 2021. It expands production capacity, market access, foreign exchange earnings, skill development, human capital growth, technology transfer, and competition in the local market. However, global FDI flows were impacted drastically by the quick spread of the COVID-19 pandemic. The report of UNCTAD in 2021 also indicates that global FDI flows decreased by 49% compared to 2019. Surprisingly, developed countries suffered the most drastic reductions, while developing countries weathered the storm better. By analyzing the change in FDI inflows by region between 2019 and 2020, as demonstrated in , it can be observed that the developed countries showed the largest drop in FDI inflows during this period. Furthermore, this trend was exacerbated by a sharp reduction in FDI inflows into European countries (−104%), while there was only a less-stronger-than-expected drop in FDI inflows into Asian and developing countries. highlights the fact that European countries are suffering the worst impacts of the COVID-19 health crisis. Consequently, the gross domestic product (GDP) of the 27 European Union countries declined by 11.9 percent in 2020. Conversely, the unemployment rate increased quickly. The French economy shrank by 13.8 percent, the GDP of Italy declined by 12.4%, and that of Spain fell by 18.4% (Kalogiannidis and Chatzitheodoridis Citation2021). European firms have also been hit hard, with nearly half of all startups seeking government financial assistance (Brown Citation2021).

While the COVID-19 pandemic has spread quickly and caused serious consequences for the global economy, the digital transformation process is entrenched (Bayram et al. Citation2020). This trend has become more inevitable as governments around the world have been forced to take extraordinary measures like lockdowns and social distancing, which accelerate the application of technology as it is used to promote remote working (Dingel and Neiman Citation2020). The process of digital transformation, therefore, is taking place in a strong and pervasive manner in all dimensions of the economy. According to Autio et al. (Citation2018), digitalization can be defined as the process of applying digital technologies and infrastructures to diverse aspects of businesses, the economy and society. Many individuals nowadays are familiar with the use of information technology (IT) in production and business. Every element of the economy has been progressively digitized as the industrial revolution has progressed. As contended by Dethine, Enjolras, and Monticolo (Citation2020), digitalization significantly influences the way that businesses operate globally. It also provides businesses with competitive advantages in the global economy (Lee and Falahat Citation2019), and can be considered as a tool for promoting internationalization (Dethine, Enjolras, and Monticolo Citation2020).

The literature indicates that digitalization has a significant and positive impact on the flow of FDI, and its role has become particularly important during the COVID-19 pandemic. Digitalization allows firms to conduct business through the internet, which may lead to changes in the structure of FDI to keep up with competitors in the global market. As revealed by Vasić et al. (Citation2019), if customers’ psychological preference to buy from traditional stores can be changed, and the fears of buying online can be subdued, many benefits can be derived from the flows of FDI into the company segment and customers compared to other firms. Rather than a traditional infrastructure, digital infrastructures stemming from the digital transformation process now play a critical role in attracting FDI flows, especially during the COVID-19 health crisis (World Economic Forum Citation2021). Improvements in digital infrastructure are important to attract more foreign investment under COVID-19 circumstances (Name Citation2021). Furthermore, digitization provides a driving force for industry to evolve more quickly because it can quickly reduce labor and product intermediate costs (Devold, Graven, and Halvorsrød Citation2017; Herzog et al. Citation2017; Pop Citation2020) and help cross-border firms to trade more straightforwardly, thus giving them new investment options (Damgaard, Elkjaer, and Johannesen Citation2018). The digital information system also enables FDI businesses to expand their reach into new markets (World Economic Forum, 2021). However, we also believe that digitalization can have negative influences on FDI inflows. For example, Ivanova et al. (Citation2019) and Radanliev, De Roure, and Van Kleek (Citation2020) indicate that firms may encounter difficulties with managing their servers and this puts them at risk of system failure or data loss. Furthermore, newly developed technologies may potentially have detrimental effects on the environment, thus digital FDI may become less attractive in the eyes of domestic countries (Hilty and Bieser Citation2017; Yadav and Iqbal Citation2021). Therefore, we predict that there may be a nonlinear relationship between digitalization and FDI inflows. In other words, digitalization may lead to a rise in FDI inflows if the digital transformation reaches a certain level.

Hence, the main purpose of this study is to explore the nonlinear curve association between digital transformation and FDI inflows. We focus on comparing the effects of digitalization on FDI in two periods: before the period of 2015–2019 and during 2020, when the COVID-19 crisis began. To achieve this goal, diverse econometric techniques are applied to a database covering 23 European countries during the 2015–2020 period. Particularly, we follow Canh and Thanh (Citation2020) and Le et al. (Citation2020) to apply the feasible generalized least square estimates (FGLS) model to investigate the digitalization-FDI nexus, taking the presence of heteroscedasticity and fixed effects into account. The panel corrected standard errors (PCSE) model is also a good option in the case of cross-sectional dependence. However, the FGLS model is preferred in this study as our sample covers a short time period T (2015–2020) and has few participants N (23 European countries). Furthermore, in another analysis, our paper focuses on the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, and the PCSE model then becomes a pertinent method that serves our purpose. For a robustness check, we also use the FGLS model for the full sample.Footnote1 Our article considers the influences of four digital activities: the use of internet services, business digitalization, e-commerce, and digital public services. We collect the data for digitalization from various surveys, for example, the Eurostat Community Survey on ICT usage in Households and by Individual; the Eurostat ICT Enterprises Survey; and the eGovernment Benchmarking Report from 2015 to 2020. Due to the potential existence of endogeneity, we include the one-year-lagged data of the explanatory variables. Since we assume the existence of a nonlinear relationship between digitalization and FDI inflow, the squared terms of the digitalization variables are also added to the model. Predictive margins analysis is employed to confirm our findings. To quantify the short-term and long-term effects of digitalization, this study also applies the autoregressive distributed lag (ARDL) method and considers the dynamic fixed effects (DFE) estimator to deal with the time and country-fixed effects (Canh, Schinckus, and Thanh Citation2021; Canh and Thanh Citation2020; Le et al. Citation2020).

2. Literature review and hypothesis development

2.1. Drivers of FDI inflows

Macroeconomic variables such as economic growth (Bevan and Estrin Citation2004; Biswas Citation2002; Blonigen and Piger Citation2014), labor force, and human capital (Blomström, Kokko, and Mucchielli Citation2003; Globerman and Shapiro Citation2002), exchange rates (Bevan and Estrin Citation2004), inflation (Asiedu Citation2002), international trade (Bevan and Estrin Citation2004), are considered as the main factors affecting FDI inflows. In addition, political-institutional factors are also mentioned as an indirect factor affecting FDI (Aziz Citation2018; Bénassy-Quéré, Coupet, and Mayer Citation2007; Biswas Citation2002; Blonigen and Piger Citation2014; Schneider and Frey Citation1985). Schneider and Frey (Citation1985), for example, provided a politico-economic model to explain FDI flows in 80 developing countries, and they discovered that political instability considerably impacted FDI inflows. Governance infrastructure, such as the political, institutional, and legal environment, is a key driver of FDI flows (Globerman and Shapiro Citation2002). Institutional indices such as bureaucracy, corruption, information, the banking sector, and legal institutions, based on Bénassy-Quéré, Coupet, and Mayer (Citation2007), influence FDI in 52 economies. Brada et al (Citation2018) found that the amount of corruption in the host nation, as well as the distance of international corruption, have a negative impact on FDIs. In a sample of 155 countries, (Xu Citation2019) found that economic freedom in both the home and host nations is positively connected with bilateral FDI.

2.2. Digitalization and FDI inflows

Prior scholars consider digitalization as an important determinant of FDI inflow. Digitalization can be defined as the process of applying digital technologies and infrastructures in diverse dimensions of businesses, the economy, and society (Autio et al. Citation2018). Nowadays, many people and firms utilize IT in their daily activities, production and business. Every element of the economy has been progressively digitized as the industrial revolution has progressed, and the way that businesses operate globally is affected significantly by digitalization (Dethine, Enjolras, and Monticolo Citation2020). FDI is considered a long-term strategic investment. FDI investors often make decisions about location investments based on the output market or the accessibility of key resources (Damgaard, Elkjaer, and Johannesen Citation2018). However, these factors are not as important as before, as in the digital economy, intangible assets take the key roles. Therefore, other considerations play a more critical role in driving the location decision.

Digitalization may transform FDI in a variety of ways. For example, the release of digital fundraiser platforms allows for more direct financing without the need for traditional intermediation. Cross-border financing becomes quicker, cheaper, and more secure with blockchain technologies (Damgaard, Elkjaer, and Johannesen Citation2018). With the advancement of digital systems, which allow firms to conduct their business activities through the internet, the structure of FDI is changing to keep up with the market. As revealed by Vasić et al. (Citation2019), the flows of FDI benefit companies and their customers if the habit of buying from traditional stores and the fear of buying online can be changed and overcome. Rather than traditional infrastructures, the digital infrastructures stemming from the digital transformation process now play a critical role in attracting FDI inflows. Moreover, the numerous costs for labor and intermediate products are minimized by digital information systems, meaning that the industrialization process evolves more quickly (Devold, Graven, and Halvorsrød Citation2017; Herzog et al. Citation2017; Pop Citation2020). The barriers to international trade gradually disappear through the digital transformation process, thus providing new investment opportunities (Damgaard, Elkjaer, and Johannesen Citation2018). The digital information system also enables FDI businesses to expand their reach into new markets (World Economic Forum, 2021). Multinational companies (MNCs) use digitization to improve the competitiveness of their products and services, resulting in positive GDP contributions in both the home country and in foreign markets. By utilizing innovative programs and reducing the usage of old traditional technology, the digitalization of the FDI sector could assist economies in moving towards sustainable development. According to Yadav and Iqbal (Citation2021), digitalization tactics can have a favorable impact on FDI activities. Electronic infrastructures can assist firms with determining where the investments flow. Furthermore, digitization can assist governments with promoting themselves in order to attract more FDI capital (Yadav and Iqbal Citation2021).

Based on our discussion, we hypothesize that:

H1: Digitalization promotes the inflows of foreign direct investments.

Based on our discussion, we hypothesize that:

H2: There may exist a nonlinear relationship between digitalization and foreign direct investment inflows.

3. Empirical methodology

We investigate the effects of digitalization on FDI inflows by using the following panel data regression:

(1)

(1) where i and t respectively represent country i and year t.

and

are added into the model to capture the country and year fixed effects, and

is the error term. The dependent variable,

is the net FDI inflow measured as the share of GDP of country i in year t.

is the proxy for the digital transformation process. We consider four genres of digitalization, including the use of the internet (INTERSER), business digitization (DIGIBUSI), e-Commerce (eCOM), and digital public servicesFootnote2 (eGOV). These variables reflect the digital performance of 27 member countries (including United Kingdom) of the European Union. They are sourced from various surveys, for example the Eurostat Community Survey on ICT Usage in Households and by Individual, the Eurostat ICT Enterprises Survey, and the eGovernment Benchmarking Report from 2015 to 2020. INTERSER captures information about internet users, or the proportion of people do certain activities, such as reading news, playing music, videos and games, video on demand, video calls, using social networks, studying online, and online transactions, such as banking, shopping, and selling online. DIGIBUSI shows information about businesses using electronic information sharing, social media, and big data, while eCOM reflects the proportion of SMEs selling online and their total turnover from e-commerce. eGOV is the number of of administrative steps associated with major life events like the birth of a child, a new residence or the share of public services needed for starting a business and for conducting regular business operations that can be done online.

Regarding other control variables, we follow similar works in the literature to incorporate the income level (Y) measured by the real GDP per capita at the constant 2010 price as in Bevan and Estrin (Citation2004) and Biswas (Citation2002); inflation (INFLA) measured by the annual percentage change of the GDP deflatorFootnote3 as in Asiedu (Citation2002); the real effective exchange rateFootnote4 (REER) as in Bevan and Estrin (Citation2004); saving (SAVE) as the share of GDP, as in Majeed and Tauqir (Citation2020) and Oladipo (Citation2010); the share of trade values (TRADESHARE) as in Bevan and Estrin (Citation2004); and the level of industrialization (INDUS) measured as the values added of the industry sector to GDP as in Gui-Diby and Renard (Citation2015) and Munir and Ameer (Citation2019). These variables are available from the World Development Indicators (WDI). Following Bénassy-Quéré, Coupet, and Mayer (Citation2007) and Nguyen et al. (Citation2018), we also incorporate political factors, such as the level of democratization (DEMO) measured by the democratization index and the level of corruption measured by the corruption perception index (CORR). While DEMO is taken from the Finnish Social Science Data Archive (FSSDA), we source CORR from Transparency International. For a further check, we add other variables reflecting the quality of governments’ policy implementation, including how efficiently they control corruption (QPP_CC) and the government efficiency index (QPP_GE). These government efficiency indexes are sourced from the World Bank Group Indicator (WBGI). The detailed descriptions of the included variables are provided in . After eliminating any countries that had missing observations, we have 23 countriesFootnote5 with data from 2015 to 2020. The correlation matrix between all the variables is displayed in , which reveals that there is a negative association between digitalization and life expectancy.

Table 1. Description of variables.

Table 2. Correlation coefficients

Subsequently, we use the cross-sectional dependence (CD) tests developed by (Pesaran Citation2021) to examine for cross-sectional dependence and then the Levin-Lin-Chu unit-root test (Levin, Lin, and Chu Citation2002) and Im-Pesaran-Shin unit-root test (Im, Pesaran, and Shin Citation2003) to perform the stationarity test of data with CD. displays the results and shows that the CD-stat is statistically significant in most of the variables, except for INDUS. This confirms that CD is existent in these variables. The unit-root tests are also included in and they demonstrate the stationarity of various variables. In addition, comparative tests for the first difference of the included variables are used, and the findings confirm stationarity.

Table 3. Cross-sectional dependence tests and stationary tests.

As well as demonstrating the existence of CD and the stationarity of first-difference variables, we select the FGLS model for our sample as recommended by Beck and Katz (Citation1995), Gala et al. (Citation2018), Nguyen, Schinckus, and Su (Citation2020) and Sweet and Eterovic (Citation2019). The PCSE model is an alternative choice when a CD arises. In this paper, the FGLS model is preferred to empirically analyze the digitalization-FDI nexus as our final sample covers a short time period T (2015–2020) and contains few entities N (23 European countries). Furthermore, in another analysis, our paper focusses on the period of the COVID-19 pandemic, and then the FGLS model becomes a pertinent method that serves our purpose. For a robustness check, this paper also employs the PCSE model for the full sample.Footnote6 All explanatory variables are lagged by one period as represented in EquationEquation (1)(1)

(1) to resolve the endogeneity stemming from the simultaneous relationship between digitalization and FDI. Other explanatory variables are included one by one into our estimations as part of the sensitivity analysis. In addition, the impact of digitalization on FDI in the short and long term is a topic discussed in this research. As a result, the ARDL technique developed by (Pesaran and Smith Citation1995) is employed. The DFE estimator utilized in the ARDL model is used due to the likelihood of endogeneity coming from the causal link between variables and the heteroscedasticity among EU countries (Pesaran and Smith Citation1995). We subdivided the complete sample into pre-COVID (2015–2019) and during-COVID (2020) periods because we anticipate that digitalization will cause FDI to fluctuate during the duration of the COVID-19 pandemic. The outcomes of this discussion can help governments determine appropriate measures and strategies for addressing the repercussions of the COVID-19 pandemic.

illustrates the findings from the Kao cointegration test, Pedroni test, and Westerlund cointegration test, which was established by Kao (Citation1999), Pedroni (Citation2004), and Westerlund, respectively, to evaluate the cointegration relationship between variables (2005). The long-term cointegration between the variables is found in digitalization and FDI.

Table 4. Cointegration test.

4. Empirical results

4.1. Baseline results

For the sample group, we first estimate the linear effects of digitalization on FDI in two subsamples for the time before and during the COVID 19 pandemic. summarizes the estimation results. Columns 1–4 were estimated for the INTERSER, DIGIBUSI, eCOM, and eGOV, respectively. Similar estimates are applied for the time during COVID-19, as reported in columns 5–8, to compare the effect of digitalization on FDI inflows before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. shows that before the pandemic, none of the four factors have a statistically significant impact on FDI inflows. During the COVID-19 health crisis, however, Internet Services (INTERSER) and Business Digitalization (DIGIBUSI) have a negative impact on FDI, meaning that a larger INTERSER or DIGIBUSI decreases FDI inflows.

Table 5. The linear influences of digitalization on foreign investments before and during the COVID-19 pandemic: The feasible generalized least square estimates.

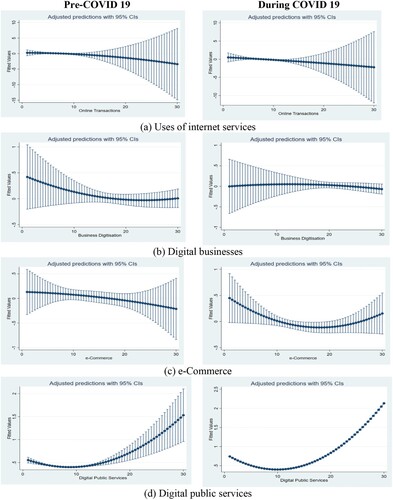

Next, we examine the nonlinear influences of digitalization on foreign investments, focusing on the periods before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. We report the estimation results in . The results reveal that business digitalization had a significant negative influence on FDI before the pandemic, but its squared term has a substantial positive impact on FDI. In other words, when the DIGIBUSI rises, the magnitude of FDI initially decreases, and the inflows of FDI tend to rise after the DIGIBUSI reaches a particular level. During the COVID-19 pandemic, we find empirical evidence for a nonlinear relationship between e-commerce (eCOM) and FDI inflows. In other words, the larger the eCOM, the lower the magnitude of FDI, and when the eCOM reaches a certain point, the impact reverses. We employ predictive margins analysis for digitalization and FDI inflows and exhibit our findings in . a depicts a gradual decline in FDI in response to a given rise in INTERSER in both periods. This straight line has a flat slope, implying that the effects of INTERSER are quite modest. b and c confirm our findings regarding the nonlinear effects of DIGIBUSI on FDI before the COVID-19 period and the nonlinear effects of eCOM on FDI during the COVID-19 period. The role of e-commerce to enhance FDI inflows during the COVID-19 pandemic is emphasized by the steep reverted U-shaped curve. Surprisingly, digital public services (eGOV), which are not statistically significant in our estimate, display a nonlinear U-shaped curve. The findings suggest that attention should also be paid to the digitalization of administrative procedures and public services. To confirm our findings, we conduct robustness checks by adding other explanatory variables and using other econometric techniquesFootnote7; we report the results in in the Appendix. The estimate indicates that our findings are reliable and robust.

Table 6. The nonlinear effect of digitalization on foreign investments: The feasible generalized least square estimates.

Next, we look at the impact of the control factors on FDI. Before the pandemic, the real output growth (Y) and the real exchange rate (REER) are statistically significant in our estimating model, with positive and negative effects, respectively. Inflation level has a negative impact on FDI during the pandemic, while savings and the industrialization level, on the other hand, have a significant positive effect on FDI.

In the following analysis, we quantify the short- and long-term effects of digitalization on FDI with the DFE-ARDL model. summarizes the findings of our study. The estimates suggest that, in the short term, the use of internet services has a large and favorable impact on FDI, and its effects persist in the long run. Notably, in the short term, Digital Public Services has significant and negative effects on FDI, but it has a favorable influence in the long run. This finding provides supporting evidence for the nonlinear relationship between digital public services and FDI inflow through the reverted U shape. The digitalization of businesses and e-commerce has a considerable positive impact on FDI. These findings suggest that while digitalization, notably Digital Public Services, may have a detrimental impact on FDI, its development has a favorable impact.

Table 7. The influence of digital transformation on life expectancy: Short-run and long-run effects

5. Discussion

Our study also supports the view that digitalization is a double-edged sword since it may adversely influence the economy and FDI inflows. The literature has indicated the dark side of digitalization. Tarafdar, Gupta, and Turel (Citation2013) refer to the adverse effects of IT as a ‘collection of negative phenomena’ and state that the use of IT potentially infringes the well-being of individuals, organizations, and societies. By reviewing the dark side of digitalization over two decades, Pirkkalainen and Salo (Citation2016) suggest the existence of four types of dark side phenomena: technostress, information overload, IT addiction, and IT anxiety. Indicating a taxonomy of the dark side of the Internet (as a subdimension of digital technology), Kim et al. (Citation2011) describe digitalization’s various adverse influences, such as spam, malware, hacking, and the violation of digital property rights.

As argued by Ivanova et al. (Citation2019) and Radanliev, De Roure, and Van Kleek (Citation2020), companies may experience difficulties with managing their servers and this puts them at a risk of system failure or data loss. Prior scholars, such as Damgaard, Elkjaer, and Johannesen (Citation2018), argue that digital transformation generates difficulties not only with geographically connecting investments but also with separating real financial integration and diversification from financial engineering. High dependency on intangible assets leads to little or no physical contacts, and this causes investment valuations to be imprecise, thus increasing the difficulty of raising funds through initial public offerings (Damgaard, Elkjaer, and Johannesen Citation2018). Additionally, the environment is adversely affected by newly developed technologies (Hilty and Bieser Citation2017; Yadav and Iqbal Citation2021). These difficulties make small firms hesitant to digitize their operations, especially in nations where labor is cheap. They will choose the old-fashioned way of doing business with people as their primary resource, eschewing technological investment due to its high cost.

Another dark side of digitalization is that it leads to a prevalence of corruption (Ha Citation2022). Smith (Citation2010) contends that corruptive behavior makes the introduction and application of law inequitable, thus impeding the country's economic and commercial development, and the efficiency of firms’ operations. Furthermore, the legitimacy-based view asserts that favorable treatment by government officials and easier access to rare and valuable resources gained from better political legitimacy discourage firms from changing or being aware of alternative strategic choices to gain competitive advantages (DiMaggio and Powell Citation1983). Instead, firms become further embedded in the favorable conditions in the long run and enjoy the ‘economic rent’ obtained from this legitimacy (Meyer and Rowan Citation1977). In this regard, bribery-paying firms may have fewer incentives to invest money in foreign countries, as this requires them to take more risks and bear higher costs (Dong Citation2017). The reason for this is that they could ensure long-term business growth in the domestic market, at low costs and risks, given the legitimacy obtained from bribery practices. In fact, managerial experience and entrepreneurial attitudes are crucial determinants of FDI (Harvie, Narjoko, and Oum Citation2010). Given the strong position in the domestic market, the more firms rely on the ‘economic rent’ obtained from bribery, the more likely it is that managers will direct resources and capabilities away from the international market. Hence, the effect of digitalization on FDI is ambiguous but the positive effects outweigh the negative ones, and thus digitalization may promote FDI inflows.

6. Conclusions

In the Industry 4.0 era, digital transformation plays an essential role in all aspects of the economy as well as society. Due to the quick spread of the COVID-19 health crisis, the role of digitalization is more clearly affirmed as a way to help countries overcome difficulties. Our empirical study is the first effort to show a link between digitalization and FDI inflows. We demonstrate fascinating discoveries on this relationship by utilizing an international sample of 23 European countries. Prior to the pandemic, business digitalization had a nonlinear effect on foreign investment, while the role of e-Commerce became particularly important during the pandemic. Second, we discover that all the aspects of digitalization and FDI have a long-term impact, whereas only some of them have a short-term impact on FDI. As a result, digitalization has a substantial impact on FDI in both the short run and the long run. Our analysis also suggests the importance of digital public services in the long run.

On the policy front, first and foremost, our study highlights the critical role of digital transformation in attracting FDI. Therefore, through this research paper, we recommend paying particular attention to this process. However, the digital transformation process may also cause negative effects in the short term, which implies that the governments should consistently focus their resources on the digitalization process to achieve a certain development threshold. Among all the dimensions of digitalization, digital business, including the use of electronic information sharing, social media, big data, and i-cloud, are the key elements involved in attracting the inflows of FDI. Governments should introduce a comprehensive package of support, including legal, financial, and technical support, to promote the digital transformation process in businesses. Furthermore, during the COVID-19 outbreak, e-commerce has been critical for attracting FDI. E-commerce involves adapting online selling, e-commerce turnover, and selling online across borders. We also recommend that governments should promote the development of e-commerce to a certain extent, not leaving it halfway. Thus, the effectiveness of e-commerce is clearly demonstrated, and e-commerce could become an effective tool for countries to overcome the challenges of the pandemic, especially for dealing with a lack of or delay of FDI inflows. Lastly, e-Government users, pre-filled forms, online service completion, and digital public services for enterprises (including the cross-border dimension) also need to receive special attention.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 The estimation results of this robustness check can be provided by authors upon request.

2 The detailed description of the methodology used to compute this index is provided in DESI (2021).

3 We use the GDP deflator instead of the consumer price index due to data availability in 2020.

4 Lower export diversification stems from a higher uncompetitive exchange rate (Ferdous Citation2011). On the other hand, a lower exchange rate can promote the diversification of export products and trading partners (de Piñeres & Ferrantino, 1997).

5 in the Appendix provides information about these countries.

6 The estimation results of this robustness check can be provided by the authors upon request.

7 To save space, the results can be provided by the authors upon request.

References

- Asiedu, Elizabeth. 2002. “On the Determinants of Foreign Direct Investment to Developing Countries: Is Africa Different?” World Development 30 (1): 107–119. doi:10.1016/S0305-750X(01)00100-0.

- Autio, Erkko, Satish Nambisan, Llewellyn D. W. Thomas, and Mike Wright. 2018. “Digital Affordances, Spatial Affordances, and the Genesis of Entrepreneurial Ecosystems.” Strategic Entrepreneurship Journal 12 (1): 72–95. doi:10.1002/sej.1266.

- Aziz, Omar Ghazy. 2018. “Institutional Quality and FDI Inflows in Arab Economies.” Finance Research Letters 25: 111–123. doi:10.1016/j.frl.2017.10.026.

- Bayram, Mustafa, Simon Springer, Colin K. Garvey, and Vural Özdemir. 2020. “COVID-19 Digital Health Innovation Policy: A Portal to Alternative Futures in the Making.” OMICS: A Journal of Integrative Biology 24 (8): 460–469. doi:10.1089/omi.2020.0089.

- Beck, Nathaniel, and Jonathan N. Katz. 1995. “What to Do (and Not to Do) with Time-Series Cross-Section Data.” The American Political Science Review 89 (3): 634–647. doi:10.2307/2082979.

- Bevan, Alan A., and Saul Estrin. 2004. “The Determinants of Foreign Direct Investment Into European Transition Economies.” Journal of Comparative Economics 32 (4): 775–787. doi:10.1016/j.jce.2004.08.006.

- Bénassy-Quéré, Agnès, Maylis Coupet, and Thierry Mayer. 2007. “Institutional Determinants of Foreign Direct Investment.” The World Economy 30 (5): 764–782. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9701.2007.01022.x.

- Biswas, Romita. 2002. “Determinants of Foreign Direct Investment.” Review of Development Economics 6 (3): 492–504. doi:10.1111/1467-9361.00169.

- Blomström, Magnus, Ari Kokko, and Jean-Louis Mucchielli. 2003. “The Economics of Foreign Direct Investment Incentives.” In Foreign Direct Investment in the Real and Financial Sector of Industrial Countries, edited by H. Herrmann, and R. Lipsey, 37–60. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer.

- Blonigen, Bruce A., and Jeremy Piger. 2014. “Determinants of Foreign Direct Investment.” Canadian Journal of Economics/Revue Canadienne D’économique 47 (3): 775–812. doi:10.1111/caje.12091.

- Brada, J. C., Z. Drabek, J. A. Mendez, and M. F. Perez. 2019. “National Levels of Corruption and Foreign Direct Investment.” Journal of Comparative Economics 47 (1): 31–49. doi:10.1016/j.jce.2018.10.005.

- Brown, Stephen. 2021. “The Impact of COVID-19 on Development Assistance.” International Journal 76 (1): 42–54. doi:10.1177/0020702020986888.

- Canh, Phuc Nguyen, Christophe Schinckus, and Su Dinh Thanh. 2021. “What Are the Drivers of Shadow Economy? A Further Evidence of Economic Integration and Institutional Quality.” The Journal of International Trade & Economic Development 30 (1): 47–67. doi:10.1080/09638199.2020.1799428.

- Canh, Nguyen Phuc, and Su Dinh Thanh. 2020. “Financial Development and the Shadow Economy: A Multi-Dimensional Analysis.” Economic Analysis and Policy 67: 37–54. doi:10.1016/j.eap.2020.05.002.

- Damgaard, Jannick, Thomas Elkjaer, and Niels Johannesen. 2018. “Piercing the Veil.” Finance & Development 0055: 002. doi:10.5089/9781484357415.022.A016.

- Daszak, Peter. 2012. “Anatomy of a Pandemic.” Lancet (London, England) 380 (9857): 1883–1884. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61887-X.

- DESI. 2020. Shaping Europe’s Digital Future. Accessed April 3, 2022. https://digital-strategy.ec.europa.eu/en/library/digital-economy-and-society-index-desi-2021

- Dethine, Benjamin, Manon Enjolras, and Davy Monticolo. 2020. “Digitalization and SMEs’ Export Management: Impacts on Resources and Capabilities.” Technology Innovation Management Review 10 (4): 18–34. doi:10.22215/timreview/1344.

- Devold, H., T. Graven, and S. O. Halvorsrød. 2017. “Digitalization of Oil and Gas Facilities Reduce Cost and Improve Maintenance Operations.” OnePetro.

- DiMaggio, Paul J., and Walter W. Powell. 1983. “The Iron Cage Revisited: Institutional Isomorphism and Collective Rationality in Organizational Fields.” American Sociological Review 48 (2): 147–160. doi:10.2307/2095101.

- Dingel, Jonathan I., and Brent Neiman. 2020. “How Many Jobs Can Be Done at Home?” Journal of Public Economics 189: 104235. doi:10.1016/j.jpubeco.2020.104235.

- Dong, Menghang. 2017. “Does Corporate Political Activity Make Firms Less Risk Taking.” Undefined.

- Ferdous, Farazi Binti. 2011. “Export Diversification in East Asian Economies: Some Factors Affecting the Scenario.” International Journal of Social Science and Humanity 1 (1): 13–18. doi:10.7763/IJSSH.2011.V1.3.

- Ford, Timothy E., Rita R. Colwell, Joan B. Rose, Stephen S. Morse, David J. Rogers, and Terry L. Yates. 2009. “Using Satellite Images of Environmental Changes to Predict Infectious Disease Outbreaks.” Emerging Infectious Diseases 15 (9): 1341–1346. doi:10.3201/eid/1509.081334.

- Gala, Paulo, Jhean Camargo, Guilherme Magacho, and Igor Rocha. 2018. “Sophisticated Jobs Matter for Economic Complexity: An Empirical Analysis Based on Input-Output Matrices and Employment Data.” Structural Change and Economic Dynamics 45: 1–8. doi:10.1016/j.strueco.2017.11.005.

- Globerman, Steven, and Daniel Shapiro. 2002. “Global Foreign Direct Investment Flows: The Role of Governance Infrastructure.” World Development 30 (11): 1899–1919. doi:10.1016/S0305-750X(02)00110-9.

- Guerrieri, Veronica, Guido Lorenzoni, Ludwig Straub, and Iván Werning. 2020. Macroeconomic Implications of COVID-19: Can Negative Supply Shocks Cause Demand Shortages? Working Paper. 26918. National Bureau of Economic Research. doi:10.3386/w26918.

- Gui-Diby, Steve Loris, and Mary-Françoise Renard. 2015. “Foreign Direct Investment Inflows and the Industrialization of African Countries.” World Development 74: 43–57. doi:10.1016/j.worlddev.2015.04.005.

- Ha, Le Thanh. 2022. “Are Digital Business and Digital Public Services a Driver for Better Energy Security? Evidence from a European Sample.” Environmental Science and Pollution Research 29: 27232–27256. doi:10.1007/s11356-021-17843-2.

- Harvie, Charles, Dionisius Narjoko, and Tae Oum. 2010. “Firm Characteristic Determinants of SME Participation in Production Networks.”.

- Hayakawa, Kazunobu, and Hiroshi Mukunoki. 2021. “Impacts of COVID-19 on Global Value Chains.” The Developing Economies 59 (2): 154–177. doi:10.1111/deve.12275.

- Herzog, Kurt, Günther Winter, Gerhard Kurka, Kai Ankermann, Raffael Binder, Markus Ringhofer, Andreas Maierhofer, and Andreas Flick. 2017. “The Digitalization of Steel Production.” BHM Berg- Und Hüttenmännische Monatshefte 162 (11): 504–513. doi:10.1007/s00501-017-0673-9.

- Hilty, Lorenz, and Jan Bieser. 2017. Opportunities and Risks of Digitalization for Climate Protection in Switzerland. Zurich: University of Zurich. doi:10.5167/uzh-141128.

- Im, Kyung So, M. Hashem Pesaran, and Yongcheol Shin. 2003. “Testing for Unit Roots in Heterogeneous Panels.” Journal of Econometrics 115 (1): 53–74. doi:10.1016/S0304-4076(03)00092-7.

- Ivanova, I. A., V. N. Pulyaeva, L. V. Vlasenko, A. A. Gibadullin, and M. I. Sadriddinov. 2019. “Digitalization of Organizations: Current Issues, Managerial Challenges and Socio-Economic Risks.” Journal of Physics: Conference Series 1399: 033038. doi:10.1088/1742-6596/1399/3/033038.

- Jebril, Nadia. 2020. World Health Organization Declared a Pandemic Public Health Menace: A Systematic Review of the Coronavirus Disease 2019 “COVID-19.” SSRN Scholarly Paper. ID 3566298. Rochester, NY: Social Science Research Network. doi:10.2139/ssrn.3566298.

- Kalogiannidis, Stavros, and Fotios Chatzitheodoridis. 2021. “Impact of Covid-19 in the European Start-Ups Business and the Idea to Re-Energise the Economy.” International Journal of Financial Research 12 (2): 55. doi:10.5430/ijfr.v12n2p55.

- Kao, C. 1999. “Spurious Regression and Residual-Based Tests for Cointegration in Panel Data.” Journal of Econometrics 90 (1): 1–44. doi:10.1016/S0304-4076(98)00023-2.

- Kim, Won, Ok-Ran Jeong, Chulyun Kim, and Jungmin So. 2011. “The Dark Side of the Internet: Attacks, Costs and Responses.” Information Systems 36 (3): 675–705. doi:10.1016/j.is.2010.11.003.

- Le, Thai-Ha, Canh Phuc Nguyen, Thanh Dinh Su, and Binh Tran-Nam. 2020. “The Kuznets Curve for Export Diversification and Income Inequality: Evidence from a Global Sample.” Economic Analysis and Policy 65: 21–39. doi:10.1016/j.eap.2019.11.004.

- Lee, Yan, and Mohammad Falahat. 2019. “The Impact of Digitalization and Resources on Gaining Competitive Advantage in International Markets: Mediating Role of Marketing, Innovation and Learning Capabilities.” Technology Innovation Management Review 9 (11): 26–39. doi:10.22215/timreview/1281.

- Levin, Andrew, Chien-Fu Lin, and Chia-Shang James Chu. 2002. “Unit Root Tests in Panel Data: Asymptotic and Finite-Sample Properties.” Journal of Econometrics 108 (1): 1–24. doi:10.1016/S0304-4076(01)00098-7.

- Majeed, Muhammad Tariq, and Aisha Tauqir. 2020. “Effects of Urbanization, Industrialization, Economic Growth, Energy Consumption, Financial Development on Carbon Emissions: An Extended STIRPAT Model for Heterogeneous Income Groups.” Pakistan Journal of Commerce and Social Sciences (PJCSS) 14 (3): 652–681.

- Meyer, John W., and Brian Rowan. 1977. “Institutionalized Organizations: Formal Structure as Myth and Ceremony.” American Journal of Sociology 83 (2): 340–363.

- Munir, Kashif, and Ayesha Ameer. 2019. “Nonlinear Effect of FDI, Economic Growth, and Industrialization on Environmental Quality: Evidence from Pakistan.” Management of Environmental Quality: An International Journal 31 (1): 223–234. doi:10.1108/MEQ-10-2018-0186.

- Name. 2021. “The Rise of Digital Infrastructure as an FDI Driver.” Investment Monitor. Accessed August 8, 2021. https://investmentmonitor.ai/business-activities/infrastructure/fdi-drivers-infrastructure-and-the-rise-of-digital.

- Nguyen, Canh Phuc, Christophe Schinckus, and Thanh Dinh Su. 2020. “The Drivers of Economic Complexity: International Evidence from Financial Development and Patents.” International Economics 164: 140–150. doi:10.1016/j.inteco.2020.09.004.

- Nguyen, Canh Phuc, Christophe Schinckus, Thanh Dinh Su, and Felicia Chong. 2018. “Institutions, Inward Foreign Direct Investment, Trade Openness and Credit Level in Emerging Market Economies.” Review of Development Finance 8 (2): 75–88. doi:10.1016/j.rdf.2018.11.005.

- Oladipo, Olajide S. 2010. “Does Saving Really Matter For Growth In Developing Countries? The Case Of A Small Open Economy.” International Business & Economics Research Journal (IBER) 9 (4), doi:10.19030/iber.v9i4.556.

- Pesaran, M. Hashem. 2021. “General Diagnostic Tests for Cross-Sectional Dependence in Panels.” Empirical Economics 60 (1): 13–50. doi:10.1007/s00181-020-01875-7.

- Pedroni, P. 2004. “Panel Cointegration: Asymptotic and Finite Sample Properties of Pooled Time Series Tests with an Application to the PPP Hypothesis.” Econometric Theory 20 (3): 597–625. doi:10.1017/S0266466604203073.

- Pesaran, M. Hashem, and Ron Smith. 1995. “Estimating Long-Run Relationships from Dynamic Heterogeneous Panels.” Journal of Econometrics 68 (1): 79–113. doi:10.1016/0304-4076(94)01644-F.

- Pirkkalainen, Henri, and Markus Salo. 2016. “Two Decades of the Dark Side in the Information Systems Basket: Suggesting Five Areas for Future Research.” ECIS 2016: Proceedings of the 24th European conference on information systems, Tel Aviv, Israel, June 9–11, 2014 (Article 101). European Conference on Information Systems. http://aisel.aisnet.org/ecis2016_rp/101.

- Pop, Liviu Dorin. 2020. “Digitalization of the System of Data Analysis and Collection in an Automotive Company.” Procedia Manufacturing 46: 238–243. doi:10.1016/j.promfg.2020.03.035.

- Radanliev, Petar, David C. De Roure, and Max Van Kleek. 2020. Digitalization of COVID-19 Pandemic Management and Cyber Risk from Connected Systems. SSRN Scholarly Paper. ID 3604825. Rochester, NY: Social Science Research Network. doi:10.2139/ssrn.3604825.

- Schneider, Friedrich, and Bruno S. Frey. 1985. “Economic and Political Determinants of Foreign Direct Investment.” World Development 13 (2): 161–175. doi:10.1016/0305-750X(85)90002-6.

- Smith, T. H. 2010. Corruption: The Abuse of Entrusted Power in Australia. Albert Park, VIC: Australian Collaboration.

- Sohrabi, Catrin, Zaid Alsafi, Niamh O’Neill, Mehdi Khan, Ahmed Kerwan, Ahmed Al-Jabir, Christos Iosifidis, and Riaz Agha. 2020. “World Health Organization Declares Global Emergency: A Review of the 2019 Novel Coronavirus (COVID-19).” International Journal of Surgery 76: 71–76. doi:10.1016/j.ijsu.2020.02.034.

- Sweet, Cassandra, and Dalibor Eterovic. 2019. “Do Patent Rights Matter? 40 Years of Innovation, Complexity and Productivity.” World Development 115: 78–93. doi:10.1016/j.worlddev.2018.10.009.

- Tarafdar, Monideepa, Ashish Gupta, and Ofir Turel. 2013. “The Dark Side of Information Technology Use.” Information Systems Journal 23 (3): 269–275. doi:10.1111/isj.12015.

- Vasić, Nebojša, Milorad Kilibarda, Tanja Kaurin, Nebojša Vasić, Milorad Kilibarda, and Tanja Kaurin. 2019. “The Influence of Online Shopping Determinants on Customer Satisfaction in the Serbian Market.” Journal of Theoretical and Applied Electronic Commerce Research 14 (2): 70–89. doi:10.4067/S0718-18762019000200107.

- Webster, R. G. 1997. “Predictions for Future Human Influenza Pandemics.” The Journal of Infectious Diseases 176 (Suppl 1): S14–S19. doi:10.1086/514168.

- World Economic Forum. 2021. The Davos Agenda 2021. Accessed March 28, 2022. https://www.weforum.org/focus/the-davos-agenda-2021/.

- Xu, Tao. 2019. “Economic Freedom and Bilateral Direct Investment.” Economic Modelling 78: 172–179. doi:10.1016/j.econmod.2018.09.017.

- Yadav, Arti, and Badar Alam Iqbal. 2021. “Socio-Economic Scenario of South Asia: An Overview of Impacts of COVID-19.” South Asian Survey 28(1):20–37. doi:10.1177/0971523121994441.

Appendix

Table A1. Countries in the sample

Table A2. Digitalization and foreign investments: A robustness check by adding more explanatory variables.