ABSTRACT

Public-private partnerships (PPPs) have become a widely recognized phenomenon in recent years, along with the rising emphasis on the private sector involvement in solving social problems both locally and globally. Against this backdrop, this study focuses on the expanded role of corporate social responsibility (CSR) in the Korean official development assistance framework. Private stakeholders’ expected roles and responsibilities in the area of international development cooperation have been augmented. The article explores the various factors driving this phenomenon from the perspectives of the public and private sectors. The case study of Korea International Cooperation Agency (KOICA) is carried out by analyzing the identified factors in the context of KOICA’s PPP strategy. The study found that the motives of the private sector to participate in KOICA’s global CSR program is less likely to be satisfied under the current arrangement whereas the public sector is highly motivated to attract and engage businesses in delivering PPP projects abroad. The study suggests policy implications such as incorporating non-financial performance indicators in evaluation criteria, resolving administrative challenges, and increasing the budget for PPP programs.

Introduction

Public expectations for private interventions are higher in times of uncertainty (UNGC Citation2021). With ongoing struggles, such as the fight against the COVID-19 pandemic, climate change, increasing government indebtedness, and social inequity, there are rising interests in public-private partnerships (PPPs) not only in domestic affairs but also in the field of international development (The World Bank Group Citation2020). Official development assistance (ODA) programs, which traditionally have been financed purely by public means, started to seek for increased participation from the private sector (The World Bank Group Citation2020). The issue of lacking monetary resources in ODA was pointed out as a significant obstacle to achieving Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) (Sohn, Park, and Kim Citation2014), and the promotion of active private capital flows is imperative for poverty reduction and economic development in Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) (Liverman Citation2018). Such solicitation is being positively responded by donors ‘deploying the concept of ‘blended finance’ and expanding their use of financial instruments … for PPPs’ (Mawdsley Citation2018, 192). Consequently, private entities including multinational companies, start-ups, civil society groups, as well as the non-governmental organizations (NGOs) have emerged as important stakeholders in the international development scene.

After the Republic of Korea (hereafter Korea) joined the Development Assistance Committee (DAC) of the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) in 2010, Korea International Cooperation Agency (KOICA), the leading development cooperation agency affiliated to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, launched pilot PPP projects as one of their ODA programs, which was later renamed to the global corporate social responsibility (CSR) program (Sohn, Park, and Kim Citation2014). Global CSR programs are evaluated as a valuable mechanism to promote PPPs, leveraging the know-how and financial resources of the private sector in development cooperation (Kim Citation2015). In 2021, however, Korea had spent only 7% of the ODA budget in cooperation projects with civil organizations and other private entities, whereas half of other DAC member countries executed 40% of the total ODA budget in PPPs (Maeil Business News, 11 May 2021). Such value would be even smaller if it is accounted only for corporate actors, excluding domestic and global NGOs. Despite the low level of PPP budget of KOICA, the partner role of the private sector in development cooperation prevails.

Against this backdrop, the study aims to identify and analyze the critical factors related to the PPPs in the form of CSR that has expanded to the global sphere and draw implications for the PPP strategy of KOICA. We examined relevant studies to evaluate reasons and motivations behind changing private sector roles in the Korean ODA framework in perspectives of both the public and private sectors. Specifically, three significant motives behind the public sector to work with private counterparts are identified: cost-efficiency, accountability to the international community, and the new governance paradigm. In the meantime, four motives of the private sector are identified to participate in PPP procurements: creating shared value, achieving non-financial performance goals, particularly in the environment, society, and governance (ESG) criteria, attracting Generation Z to the workforce, and entering a new market. We then analyzed how these identified variables come into promote or halt private participation in global CSR initiatives and the Korean framework of PPP arrangements. We conclude with relevant policy implications from the analysis.

The study contributes to the understanding of the changing nature of PPP, which is closely connected with global CSR activities. While previous literature focused on examining the roles, structure, or performance of PPPs (see Casady et al. Citation2020; Hodge and Greve Citation2016; Yuan et al. Citation2012), this study's findings provide insights on the multifarious motivation of participating in PPPs of diverse stakeholders. The implications drawn from the analysis of the KOICA’s PPP framework and strategy may also contribute to policy directions of emerging donors as Korea’s case is scarcely discussed despite the growing number of articles on PPPs (see Ma et al. Citation2019). Based on our findings, practical implications related to tailoring KOICA’s current PPP schemes to the private sector’s needs are suggested such as incorporating non-financial performance indicators in evaluation criteria, resolving administrative challenges, and increasing the ODA budget for PPP programs.

What is driving PPPs? Perspectives of the public and the private sectors

Even though the concept of PPP has been used since the early 1960s in the United States, the recent form of PPPs has developed with the stream of the New Public Management (NPM) movement in the 1980s (Bovaird Citation2010). To adjust to the demands of a competitive market economy, public bureaucracies started to make efforts to overcome administrative corruption and inefficient allocation of resources caused by elitist bureaucracy (Robinson Citation2015), embracing private sector management models such as performance measurements, detailed output specifications, and goal settings (Dunleavy and Hood Citation1994; Hodge, Greve, and Biygautane Citation2018; Robinson Citation2015). The pursuit of NPM has guided governments to turn their attention to implementing PPP arrangements, partnering with businesses in the various stages of the project cycle (Hodge and Greve Citation2016).

Even though the form and structure are entirely different from cooperating under PPP procurement models, the concept of promoting partnership between the public and private sectors has been frequently observed in the context of Korea’s economic development since the 1960s. Evans (Citation1995) claimed that countries vary in the way they are tied to social groups and that Korea is a nation of ‘embedded autonomy’: a government with organizational coherence embedded in close and dense social ties especially with the private sector. He characterized embeddedness as a concrete set of connections between the government and social groups in achieving development goals, putting emphasis on the cooperation between public and private actors (Evans Citation1995). His theory entails that it is important for the state to have the ability to formulate and implement policies autonomously so that such close ties with the private sector do not fall into political corruption (You Citation2005). Exerting strong authority and influence on industrial policies, the Korean government desired the symbiotic relationship with businesses that have grown into chaebol, a term referring to family-run conglomerates, providing support in loans, subsidies, and tax incentives from the initial phase in the industrialization (Council on Foreign Relations, 4 May 2018). This effort was made to rebuild the economy and infrastructure of the devastated land after the Korean War in the mid-1950s (Council on Foreign Relations, 4 May 2018; Rhyu Citation2005). In the early 1960s, these firms were small in size; however, Korea’s government-led industrial policy and incentive schemes offered to the companies for the nation’s economic development allowed them to earn expertise and global brand names, strengthening the state-business networks (Sial and Doucette Citation2020). Explained by the theory of embedded autonomy, state-business relations have been amicable to achieve the nation’s goal through a combination of centralized government and close networks with corporations.

There is no single definition or framework of PPP that all the international community concedes because PPPs are inherently broad (Hodge, Greve, and Biygautane Citation2018). Asian Development Bank refers to PPPs as risk-sharing projects among the public and the private sector entities, in which ‘financial rewards to the private party commensurate with the achievement of pre-specified outputs’ (Asian Development Bank Citation2006, 11). According to a report published by the World Bank, PPP is defined as ‘[a]ny contractual arrangement between a public entity or authority and a private entity to provide a public asset or service, in which a private party bears significant risk as well as management and operational responsibility’ (Ruiz Nunez et al. Citation2020, 5). PPPs have conceptually developed ever since, and the length of the contractual arrangement and project stages were specified in a study. Casady et al. (Citation2020) define PPPs as ‘long term contractual arrangements between public agencies and private partners that increase private participation and risk-sharing in various stages of the project lifecycle, including facility design, construction, financing, operations, and maintenance.’ In our study, we adopt a definition of the World Bank, adding assumptions that PPPs encompass diverse ways of private participation ranging from financial or in-kind contributions to operational and managerial involvement in various stages of the project lifecycle.

Motivations of the public sector

Motives of the Korean public sector to engage in PPPs are identified as the achievement of cost-efficiency, demonstration of accountability to the international community, and the rise of the new governance paradigm. It is undeniable that public missions can be pursued at a lesser cost when the private sector provides financial resources. Because PPP procurements focus on sharing costs, risks, benefits, and resources with private partners (Casady et al. Citation2020), the government has less burden of public borrowing, especially for a large-scale program involving infrastructure building. Moreover, governments that agreed to the SDGs, the ambitious global agenda to mobilize global efforts to solve sustainable development challenges by 2030, are aware that these goals are unlikely to be achieved without private capital. Lastly, as a novel form of the collaborative policymaking in the new governance era, a PPP procurement model promotes creating social value and generating profits simultaneously (Osborne Citation2000; Prats Citation2019).

Cost-efficiency

Every government considers how it can reduce costs while maintaining a high level of impact (Hemmige, Watters, and Daniel Citation2021). Given that public sector resources are primarily generated through taxes, they should be used efficiently and effectively to present accountability to the public (Mandl, Dierx, and Ilzkovitz Citation2008). Often characterized by bureaucratic inefficiency and political costs, however, public spending is difficult to be assessed (Mandl, Dierx, and Ilzkovitz Citation2008). To accommodate this issue, partnering with private entities may offer innovative ways to deliver projects on time and within budget, enhancing the public’s perception of value for money (Casady et al. Citation2020; Mandl, Dierx, and Ilzkovitz Citation2008). Thus, the critical motivation on the government’s side to partner with businesses is to achieve enhanced cost-efficiency in delivering large-scale projects or public services (Wang et al. Citation2018).

There are arguments, however, that there would be new or increased costs to manage relationships and bargain with private actors (Hong and Kim Citation2018). Because PPP procurements require partners to negotiate and interact throughout the project lifecycle, governments need additional resources in this process, which were not utilized when they provided public service on their own. Nevertheless, the private sectors’ for-profit nature, such as innovation capacity, risk management, and maintenance ability, can substantially enhance the cost-efficiency of PPP procurement models (ADB et al. Citation2016), reducing the public sides’ burden on financing.

Accountability to the international community

Unlike the MDGs, for which the pre-eminent form of financing is ODA or foreign aid from donors, the SDGs encourage investments from the private sector (Mawdsley Citation2018). The SDGs encompass a wide range of inter-connected topics across sustainable development's economic, social, and environmental dimensions. The goals are universally applied to both developing and developed countries, and committed governments are expected to incorporate these goals into their national development plans and policies (UNGC Citation2021). One of the most critical prerequisites to achieve this ambitious plan is to secure finances. ODA continues to be recognized as an essential resource, yet businesses are regarded as accountable partners for the SDGs to be achieved.

As one of the newest member countries of the OECD DAC, the Korean government thrives on remaining an accountable donor, actively encouraging the private sector’s aid funding. From the 1950s to the 1980s, Korea had been a major recipient country of ODA. In 2009, however, South Korea joined the DAC as its 24th member and became the first country in history to transform from recipient to donor (Arirang News, 26 November 2021). Although the ODA volume of Korea is far from reaching the target suggested by the United Nations (i.e. ODA/Gross National Income (GNI) ratio of 0.7%), Korea has continuously increased its ODA to GNI ratio. In this regard, the Korean government has proposed the advancement of partnership with the private sector as one of the key strategies of the International Development Cooperation Plan of 2022, mainly to maximize the efficiency and effectiveness of its use of the limited ODA budget (ODA Korea Citation2022). This strategy includes diverse plans: increasing the budget for cooperative programs with civil society (i.e. NGOs); developing innovative partnership programs with business participants including social venture, start-ups, and small and medium-sized enterprises; supporting private firms to enter the international market; and achieving ESG goalsFootnote1 by bridging ODA to CSR activities.

Compared to its predecessor (i.e. MDGs), the SDGs emphasize not only the multidisciplinary development but also the sustainability of development outcomes (Kwak Citation2012). Partnership with the private sector, both from the donor and recipient countries, can enhance the follow-up and maintenance of development results that require continuous financing and management (ADB et al. Citation2016; Casady et al. Citation2020). Such tendency has been demonstrated especially from the infrastructure projects. Pursuing values and incentives that are innately different from the public sector, private counterparts exhibited prompt delivery as well as follow-up activities that often lead to another business opportunity, seeking a return on their investment (Hodge, Greve, and Biygautane Citation2018).

New governance paradigm

A shift to the new governance paradigm, which embraces the relational capital of diverse actors in policymaking, has been another motivating factor for a government to pursue PPP procurements abroad. The prevailing idea of public administration of the twentieth century was command and control, characterized by the centralized government (Robinson Citation2015). There are arguments, however, that no single government or a public agency has the capacity to meet diverse needs or solve complicated problems of present-day economic, social, political, or cultural conditions (Weber and Khademian Citation2008). Moreover, a critical environmental context in which public agencies operate is globalization, an era of transnational governance rather than individual nations (Koppell Citation2010; Kwak Citation2012). In this regard, the new governance approach does not put government as the only force engaged in policymaking and implementation but instead promotes inter-organizational relationships. The emergence of various stakeholders and the increase in multiple and complex interests have led governments to have no choice but to accept and adopt the new governance approach in policy deliberation at local, national, and global levels (Robinson Citation2015).

The blurred roles of regulatory actors well describe the characteristic of new governance paradigm (Solomon Citation2010). Initially, there were clear-cut roles: the government regulates, and the private sector is regulated. Traditional roles are becoming indistinguishable that sometimes the private sector gets involved in setting rules and regulations, and the government plays the role of facilitator (Solomon Citation2010). New functions in the new governance paradigm do not assign fixed positions of private, public, or non-profit sectors to solve a nation or the world’s prominent issues ranging from economic development to climate change (Kramer and Kania Citation2006; Sial and Doucette Citation2020). This approach considers diverse actors as co-producers and co-implementers of public service (Osborne Citation2006; Robinson Citation2015).

Adherence to the new governance paradigm highlights collaborative policymaking between the state, market, and civil society from agenda-setting to evaluation (Kim Citation2010; Osborne Citation2006). Improvement in local welfare services of Korea is an example of the successful adoption of the new governance paradigm. Before it was incorporated, local governments and hospitals had provided welfare services independently, causing inefficiency due to overlap and omission in welfare services (Kim Citation2010). In 2001, however, the Local Councils on Social Welfare was established in fifteen cities in Korea as a collaborative forum that invite public officials, healthcare experts, and practitioners from the private sector to discuss welfare issues in linking social welfare and medical services (Kim Citation2010). Such workable new governance forum has expanded its size and influence that all cities in Korea have systematized by 2006, enhancing efficiency of welfare services and promoting democratic values (Kim Citation2010).

The rise of the new governance paradigm in Korea was first noticed in local politics from the late 1990s, and the governance paradigm has expanded its sphere to the global political process. During the Kim Dae Jung administration, taking office from 1998 to 2003, the new governance theory was applied in forming domestic policies (Lee, Lim, and Park Citation2008). Under the Roh Moo Hyun government, the next administration, the governance model was actively incorporated by including civil and labor participation in the political process, mainly to earn political support (Lee, Lim, and Park Citation2008; Kim Citation2010). The topic of ‘governance and structure’ notably increased in the Korean media coverage during the Lee Myung Bak administration from 2008 to 2013, which was rarely discussed in public before 2010 (Koo and Cho Citation2017). The establishment of the legal and institutional foundation of ODA in 2010 may have influenced the media to discuss the topic frequently during the Lee administration (Koo and Cho Citation2017).

Even though a policy package has not yet announced in the area of ODA, more PPP projects reflecting the new governance paradigm are expected in the Yoon Suk Yeol administration, who took office on 10 May 2022. His biggest campaign pledge was to foster private sector-led economy and to shift to the new governance paradigm, systemizing expert and market-centered policy formulation and implementation (Munhwa Ilbo, 31 May 2022). Such direction is differentiated from mere dispersion of power in that it suggests active participation of experts and businesses’ creative capacity to be reflected in polices (Seoul Shinmun, 28 January 2022). Numerous conglomerates have shown support for the government’s move by releasing large-scale investment plans in areas including next-generation growth power and recruitment (Economy Chosun, 1 June 2022). The new governance paradigm is expected to be featured in a wide range of policy areas both in domestic and global affairs, including the international development agenda.

Motivations of the private sector

The motivation of the private sector to participate in PPP projects mainly stemmed from the evolved nature of CSR initiatives. The meaning of CSR has vastly changed since the term first emerged in the 1960s. When the aim of self-interest maximization was prioritized for enterprises, the earlier CSR initiatives were only passively delivered or even disregarded (Kramer and Kania Citation2006). Later, businesses started promoting corporate reputation or building brand image with CSR efforts but only by committing to episodic or one-time event (Kramer and Kania Citation2006). As the movement to create shared values (CSV) was initiated in the 2000s, however, CSR has evolved to become more strategic by integrating social and environmental impact into daily operation (Kwak Citation2012).

Besides achieving CSV, other key factors that drive businesses to get involved in development cooperation with the public sector are the pursuit of ESG, the attraction of the employment population, and the opportunity to enter new markets. PPPs in the field of international development can lead to the achievement of the ESG goals by participating in environmentally and socially sustainable programs (Chao and Farrier Citation2021; SDG Compass Citation2015). Moreover, businesses started to perceive global CSR as an integral step for corporate survival. Attracting Generation Z, a generational cohort of the young who value ethical perspectives in choosing their careers, has become one of the top agendas for businesses, especially considering the anticipated demographic cliff crisis. At the same time, securing new opportunities through market expansion is nevertheless still a fundamental objective for its sustainable growth and profit maximization (Kim, Park, and Kim Citation2018).

Beyond corporate reputation: creating shared value (CSV)

There is a consensus that CSR initiatives take responsibility for the environment and society beyond profit maximization (Choi et al. Citation2021). In the earlier days, the primary motivation for CSR was limited to improving corporate reputation, the most valuable intangible assets to the firms (Gibson, Gonzales, and Castanon Citation2006; Hall Citation1993). When non-profits or activists raise an issue such as labor rights or greenhouse gas emissions, companies can be vulnerable to irreparable reputational damage (Kramer and Kania Citation2006).

The idea of CSV, or the strategic CSR, has appeared in the early 2000s emphasizing the harmony of economic and social objectives between the business and society (Porter and Kramer Citation2006). CSV is a new business paradigm that enables firms to achieve long-term economic performance while addressing societal needs (Porter and Kramer Citation2006). It can lead to strategic initiatives that are connected to the business objective, being a source of business opportunity, innovation, and social values, while generating benefits to both the private and public sectors (Porter and Kramer Citation2006). Under the notion of CSV, socially responsible activities are no longer separately carried out from business activities (Drucker Citation1984; Lim and Chun Citation2018) as a firm may find economic opportunity in the process of fixing social problems and vice versa.

In this article, we are using the term global CSR to refer to strategic CSR or CSV initiatives pursued by the private sector in the field of international development cooperation. In pursuit of the company’s benefit and competitiveness, corporations may strategically collaborate with the public sector to operate under shared value. As global CSR programs involve corporate responsibility regarding the development of the partner country (i.e. poverty reduction, economic development, protection of human rights, etc.), they are often carried out in PPP arrangements.

Achieving ESG

ESG criteria are a set of non-financial indexes of business performance, risk, and values in environment, society, and governance factors. The environmental factor considers a company’s compliance and contribution to preventing climate change; the social factor refers to the treatment of internal and external stakeholders and impact on local communities; and the governance facChao and Farrier Citation2021tor addresses transparency in the management of a firm and its stakeholders (i.e. selecting board members) (Chao and Farrier Citation2021). Incorporating the ESG framework into corporate decisions is becoming a standard practice, not only to fulfill the ethical standards but also to pursue a practical return. Acknowledging that positive ESG outcomes can attract more investment and enhance corporate value (Serafeim Citation2020), a myriad of companies is becoming increasingly conscious of the ESG criteria. Because most international development projects pursue socially and environmentally sustainable outcome with innately humanitarian purposes, participation in global CSR programs in the form of PPP arrangement is an attractive option to achieve ESG goals for corporate actors (Chao and Farrier Citation2021; Park Citation2022).

Against this backdrop of global trends regarding ESG, the current state of the Korean private sector features an insufficient level of incorporating ESG goals into daily operation. The K-ESG guideline report, which was developed in cooperation of multiple ministries and distributed by the Ministry of Trade, Industry and Energy (Citation2021), elaborates trends of the Korean ESG and introduces ESG guidelines specific to the Korean context. This report points out how small and medium-sized enterprises face difficulties to respond to ESG goals due to lacking resources (i.e. budget and staff) unlike large conglomerates equipped with capacity to establish a system to work exclusively on ESG-related policies or goals. A guideline developed by the government specific to the Korean context may accommodate small and medium-sized enterprises to have better understanding of ESG and attract more investment accordingly. This report, however, does not provide the assessment standard for global CSR activities, a criterion that highly reflects ESG performance. Value of both CSR and ESG emphasize environmental and social sustainability, and the successful implementation of global CSR can contribute to the fulfillment of ESG expectations and goals (Choi et al. Citation2021). At the same time, when businesses incorporate ESG principles in delivering PPP procurements, they can arrange investments and bring social impact simultaneously, which is a clear demonstration of a shared value.

Attracting generation Z

The demographic crisis is a huge threat and challenge to numerous Korean businesses because it will cause a shrinking workforce, an issue related to business survival (Leibold and Voelpel Citation2007). The aging population is a world-wide problem, and ahead of this curve, Korea’s total population has shrunk at an unprecedented rate (Lee and Botto Citation2021). In 2021, the total number of babies born decreased 6.7% compared to the year before, and the fertility rate was 0.82 births per woman, which is the lowest record in the world (The Korea Herald, 24 November 2021). Moreover, in 2020, the nation hit more deaths than births for the first time (CNN World, 4 January 2021).

It has become a top concern for businesses to attract and engage Generation Z at a time when the overall workforce is shrinking. In Korea, generational cohorts are mainly divided into five categories: baby boomers, the 386 generations, Generation X, millennials, and Generation Z (hereafter Gen Z) (See ). Among these divisions, Gen Zs, which will soon surpass millennials in terms of population, are particularly interested in human rights because they perceive identity-related causes are important (Francis and Hoefel Citation2018). They choose consumption to manifest personal values, staying keen on politically correct positions or ethical behaviors demonstrated by businesses (Francis and Hoefel Citation2018). The Gen Zs no longer judge a company only by its products or services but rather by its ethics, practices, and social impact (Gomez, Mawhinney, and Betts Citation2019), and such judgments would influence their choice of employer. In Deloitte (Citation2021)'s Millennial and Gen Z Survey, however, 70% of respondents felt that businesses ‘focus on their agendas rather than considering the wider society,’ reflecting a regretful view that Gen Zs have of businesses. In order to satisfy and attract this potential workforce whose priority is being a ‘good’ global citizen, companies should demonstrate their commitment to social problems (Gomez, Mawhinney, and Betts Citation2019). Aligning products or services with global CSR initiatives, thus illustrating that their actions are consistent with their ethics, is an effective strategy for companies to attract and engage Gen Zs to prepare for the labor shortage and secure workforce for business survival.

Table 1. Generational cohorts in Korea.

New opportunity

As much as the social responsibility of business is emphasized, the traditional objective of business is no less degraded: businesses must survive from the competition and maximize profit, maintaining growth. In the era of globalization, companies consider foreign governments, businesses, and individuals abroad as their potential clients. In this regard, participating in a global CSR project in the form of PPP is an attractive way to enter a new market and achieve growth, especially when the company owns innovative technologies that can contribute to the sustainable development of the partner country. Participation in the pursuit of SDGs can lead to new business opportunities through developing new products and solutions or targeting new market segments (SDG Compass Citation2015). Markets in recipient countries are most likely to lack both infrastructure and business know-how (Kim, Park, and Kim Citation2018). Businesses of a donor country can provide the hardware (i.e. infrastructure, equipment, etc.) and software (i.e. technical assistance, consulting, etc.) solutions to these countries under a PPP scheme, a novel way that was not tried before in the domestic market (Kim, Park, and Kim Citation2018).

The initiatives for traditional ODA-PPPs and global CSR-PPPs both serve the corporate objective of searching for new opportunity; however, there are differences in two ways. First, corporate actors do not necessarily have to consider shared value, aligning their business activities with the company’s own CSR strategy, when they participate in traditional ODA-PPPs. In contrast, when companies participate in global CSR-PPP projects, they often coordinate them with the corporate’s own CSR strategy and objective (Bodruzic Citation2015). Therefore, CSR-PPPs are more likely to induce new market entrance aligned with a CSR strategy than traditional ODA projects. Another difference is the extent of involvement of corporate actors. The traditional ODA-PPP projects are developed and implemented by traditional developmental actors such as governments and international organizations (Richey and Ponte Citation2014). Here, corporate actors bid for the PPP projects that are designed and funded by ODA. On the other hand, global CSR projects in the form of PPP often involve a joint planning and financing, which provides corporate actors more autonomy for searching for market entrance and expansion than that of traditional ODA projects.

Relationship of the key factors of private sector motives

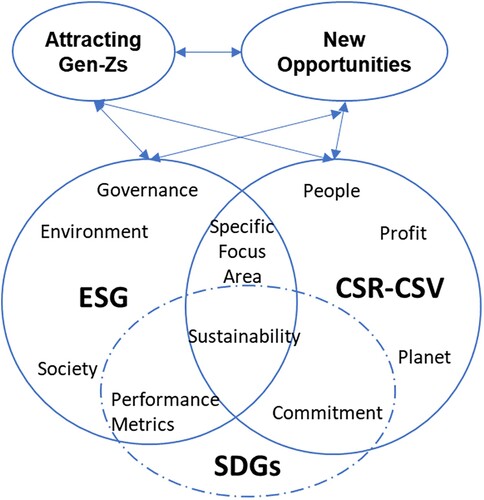

As illustrated in , these factors of motivations of participating in the PPP initiatives, especially in the form of global CSR, are highly interactive and correlated. The individual factors are complementary to each other: embracing CSV and ESG have intersections while achieving these values will encourage the attraction of potential employees and expansion of the market. The relationship between ESG, CSR, and SDGs upholds a critical common value: sustainability. Commitment to SDGs is one of the significant factors identified in the public motivation for PPP arrangements in this article, demonstrating the interrelated relationship with the overlapped motives of the private sector.

Figure 1. Factors of Private Partnership in Global CSR Activities. * Source: Planet People Productivity (Citation2021). ‘The Great Sustainability Bake-Off: CSR vs. ESG vs. SDG,’ and modified by authors.

KOREA’s PPP-ODA: KOICA’s PPP framework

Korea’s PPP-ODA trend

The data of OECD DAC member countries demonstrate the higher proportion of private grant, both in absolute and comparative terms, than that of the public grant. shows the proportion of grants in ODA, other official flows, private flows at market terms, and net private grants of the DAC members by year (OECD Stat). Private flows at market terms are resources financed out of the private sector, and net private grants are grants given by NGOs and net subsidies received from the official sector (CitationOECD.Stat). According to the OECD data, private capital flows can be divided into foreign direct investment, portfolio equity, remittances sent home by migrants, and private sector borrowing. The data of OECD DAC member countries demonstrates that the proportion of private grants, the sum of private flows at market terms and net private grants, has remained substantially higher than public grants from 2010 to 2019, except for the year 2015 when the ratio recorded approximately 1:1. The data does not capture the size of private contribution in the PPPs or global CSR; however, it demonstrates the significance of the private grant for the development finance both by the nominal and comparative size.

Table 2. OECD-DAC’s development resources flow by year (Proportion).

with Korea-specific data demonstrates the expansion of private funds in ODA in Korea. Korea’s proportion of private grants in the year 2019 recorded 114.4%, while that of public funds decreased substantially. An increase in private grants both in absolute and comparative values indicates that total financing for development has expanded, which is likely to bring qualitative effectiveness as a result (Kwak Citation2012). The Korean data also illustrates a high proportion of private flows consisting of over 65% for all years since 2010. Even though it does not specifically capture the amount of budget allocated to the PPPs or global CSR, it demonstrates a large amount of direct investment from the Korean private sector.

Table 3. Korea’s development resources flow by year (Proportion).

KOICA’s framework for PPP

KOICA is an aid implementing agency under the Ministry of Foreign Affairs that oversees grant type ODA of Korea, which takes up about 60% of the total ODA budget.Footnote2 KOICA’s PPP procurement model, first implemented in 2010 as a pilot program, evolved into the agency’s separate program division titled the Development Innovation Program (DIP). The DIP consists of three separate programs: the Creative Technology Solution (CTS) program supporting entrepreneurs developing innovative technology for application in ODA projects, the Inclusive Business Solution (IBS), a program specifically designed for the bottom of the pyramid (BOP) of the least developed countries, and Innovative Partnership Solution (IPS) program promoting partnerships with various international NGOs and organizations as well as local private institutions of recipient countries.

According to KOICA, the DIP has served as a platform to partner with enterprises and NGOs in diverse fields, successfully carrying out numerous projects, attracting a high volume of outside investment, and creating jobs both in Korea and project sites (KOICA Citation2022). KOICA has financed approximately 58 million US dollars in 237 PPP projects in 37 countries. Among the three DIP programs, the IBS program resembles PPP arrangements familiar to us, while the CTS program suggests an evolved form of PPP schemes. The IBS emphasizes cooperative project design between KOICA and the business partner, emphasizing the inclusive business model of BOP stakeholders (KOICA Citation2021b). The projects implemented through IBS programs usually involve large-scale infrastructure projects (i.e. construction of hospitals or vocational schools in addition to the relevant training and service provision) or integrative area development (i.e. village-side development programs involving both infrastructure and service provision).

On the other hand, the CTS program has more of an incubating nature targeting the start-ups (KOICA Citation2021a). KOICA provides not only training programs for business model building but also funding for technology development and pilot project implementation. The participating start-ups are not obligated to contribute financially, but they need to develop innovative technology and business models with a market value that can attract outside investments. In that sense, the CTS program seems to propose a new form of PPP in which the public sector, in this case, KOICA, provides a fundamental investment as well as project opportunity in the field. The participating start-up company contributes by developing and delivering a relevant solution, while the additional financing to implement and sustain the actual project is partially attracted from the third party, which can be another public or private entity.

What is working? and what is not?

It still needs to be questioned whether the motivations of the private sector are fulfilled in KOICA’s framework. The initiative to attract start-ups and social ventures deserves credit, especially under the circumstances where global CSR programs had been carried out mostly by large firms such as chaebol. In Korea, chaebol companies are the usual target of activists due to their high visibility, thus making them to have turned their attention to linking CSR initiatives to development cooperation projects since 2010 (Sial and Doucette Citation2020). Nevertheless, a large proportion of businesses participating in KOICA’s PPP programs still conduct projects at the level of receiving subsidies or outsourced contracts (Koo, Kim, and Kim Citation2015). A myriad of programs carried out with these private entities targets the underprivileged of partner countries, but most of them have not been able to create goods or services using the core technologies and shared values (Koo, Kim, and Kim Citation2015)

Moreover, KOICA’s programs invite private partners to join and contribute to international development, but it lacks performance indicators that assess a wide range of ESG. There are international CSR standards and principles, such as ISO 26000, Footnote3 but they only serve as self-regulatory schemes to the corporate actors. Global CSR projects in the form of PPP may fall under the globally agreed evaluation and reporting mechanism (i.e. OECD DAC evaluation criteria), which might be unfamiliar to corporate actors. According to the recent report published by Korea University and the Korea Institute of Procurement on PPP strategy, most companies interviewed are unaware of the OECD DAC evaluation criteria (Choi et al. Citation2021). At the same time, private companies’ main goal of participating in KOICA’s global CSR program was mostly related to promotion of brand image when surveyed in 2013 (Baek Citation2013). These data reveal that private actors lack a clear guideline or a framework to pursue non-financial performance goals and that they regard global CSR-PPP programs as mere defensive CSR initiatives, not to create shared value or achieve ESG goals. The specific elements of CSV can be different for each company based on the field of operation or business model, whereas the ESG is a commonly shared goal. In that sense, a comprehensive evaluation framework incorporating both global development agenda represented by the OECD DAC criteria and ESG values can serve as a roadmap that spells out a clear value-based objective for the private partners to participate in global CSR programs.

The Korean government’s newly shared K-ESG guideline can serve as a useful reference when developing such comprehensive evaluation framework for KOICA’s global CSR programs. This report provides detailed but essential ESG assessment factors that are commonly included in global standards such as World Economic Forum and Global Reporting Initiative. The identified criteria and specific factors can serve as a standard for corporations to diagnose and improve the quality of ESG achievement at a local level. Nevertheless, the K-ESG guideline lacks measurements for any ESG contribution made from CSR activities performed at international sites. Incorporation of global development agenda with the existing ESG guideline, therefore, can be a meaningful amendment that can broaden the spectrum of application.

Another hurdle for PPP is the complicated administrative tasks to work with KOICA and regulations rooted in the public sector. The private entity may lack employees specializing in development cooperation projects, and it is challenging to manage complex administrative steps and tasks required to work with a government agency (Choi et al. Citation2021; Eom Citation2017). It is a plausible option for businesses to cooperate with NGOs familiar with administrative tasks in development projects (Eom Citation2017). One way to solve this problem is providing a separate platform for companies to partner with civil society organizations such as local and global NGOs where KOICA can play a matchmaking role.

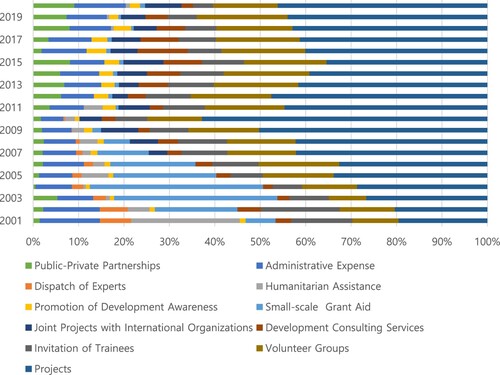

After all, despite the Korean government and KOICA’s demonstrated initiatives and strategies to strengthen the partnership with the private sector, the government budget for PPP arrangements is still relatively low. Data from KOICA indicates increasing expense in PPPs, yet the proportion is less than 10% of its total budget in 2020 (see ). The number of global CSR programs compared to the overall CSR initiatives of Korean companies is also far from significant. The Social Gap Report jointly published by the Korean government and Korea Association of Social Workers in 2020 found that out of 418 CSR activities of Korean companies, 10% is carried out both domestically and internationally while only 5% is solely global. KOICA and the government need to acknowledge the challenges and barriers faced by the private sector and provide the tailored strategy accordingly. At the same time, budget allocated specifically for PPP procurements needs to be raised to the level of other OECD DAC countries.

Conclusion

This study focused on the emerging role of CSR in the Korean ODA framework, identifying significant factors that motivate the public and private sectors. Private stakeholders’ expected roles and responsibilities have been augmented, and in this article, we have explored the various factors driving this phenomenon. In the perspective of the public sector, PPP procurements share costs and risks with the private sector, reducing the public side’s burden. Moreover, the commitment to the international community in achieving SDGs and the emergence of the new governance made it critical for the government to promote partnership with the private sector in tackling global challenges. On the other hand, CSV became a strategic option for businesses, aligning their practices with social values. Other motives for the private sector to partner with the government include achieving non-financial performance goals such as ESG, engaging the young generation by becoming an attractive employer, and expanding into new markets, which are all related to business survival in the coming years.

The case study of KOICA’s PPP framework is carried out by applying the identified factors as a framework of analysis. Our study found that the public sector is highly induced to cooperate with the private sector in delivering PPP arrangements; however, from the private sector perspective, businesses are less likely to be motivated under the current PPP framework of KOICA. Companies may perceive it as challenging to achieve their CSV or ESG objectives from the mere outsourcing type of projects, and there are no guidelines or evaluation criteria outlined incorporating ESG indicators for global CSR projects. The complicated administrative process to work with the government is another huge barrier. The study provides policy implications for KOICA to allocate more PPP budget to promote quality-enhanced partnership between the two sectors and tailor its strategy to the needs of private sector partners.

Based on the survey conducted by the Korea University research team, more than 63% of the companies responded that they have plans to participate in CSR-CSV projects in developing countries, and more than 85% of the companies expressed their interests in partnering with the public sector to carry out such projects (Choi et al. Citation2021). The implications drawn from this study can contribute to realize such plans so that effective and sustainable outcomes of the PPP procurement model are attributable to both sectors.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 The Korean government recently published ‘K-ESG Guideline’ (2021) as an attempt to develop a standard for ESG quality management. Further discussions regarding this report are made later in this paper.

2 Korea’s ODA is composed 60% of grant and 40% of loan (Economic Development Cooperation Fund (EDCF)), in which the EDCF is implemented by Korea’s Export-Import Bank under the monitoring of the Ministry of Economy and Finance. (see https://www.mofa.go.kr/eng/)

3 Other principles and guidelines include, but are not limited to, G4 Sustainability Reporting Guidelines, UN Global Compact, Global Reporting Initiative, OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises, and Social Accountability 8000.

References

- ADB, EBRD, IDB, IsDB, and WBG. 2016. “Chapter 1: Public-Private Partnership- Introduction and Overview” In the APMG Public-Private Partnership (PPP) Certification Guide, 3–180. Washington, DC: World Bank Group.

- Asian Development Bank. 2006. Public-Private Partnership Handbook. Manila: ADB.

- Baek, S. H. 2013. “A Study on the Global CSR of Korean Corporations.” MSc diss., Hanyang University. in Korean.

- Bodruzic, D. 2015. “Promoting International Development Through Corporate Social Responsibility: The Canadian Government's Partnership with Canadian Mining Companies.” Canadian Foreign Policy Journal 21 (2): 129–145.

- Bovaird, T. 2010. “A Brief Intellectual History of the Public-Private Partnership Movement.” In International Handbook on Public-Private Partnerships, edited by G. Hodge, C. Greve, and A. Boardman, 43–67. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

- Casady, C. B., K. Eriksson, R. E. Levitt, and W. R. Scott. 2020. “(Re)defining Public-Private Partnerships (PPPs) in the New Public Governance (NPG) Paradigm: An Institutional Maturity Perspective.” Public Management Review 22 (2): 161–183.

- Chao, A., and J. Farrier. 2021. “Public-Private Partnerships for Environmental, Social, and Governance Projects: How Private Funding for Infrastructure Can Produce Mutual Benefits for Companies and the Public.” Paper presented at the International Conference on Sustainable Infrastructure 2021. December 6–10.

- Choi, J. W., M. K. Chung, K. W. Kang, J. H. Jung, M. J. Lee, Y. W. Kang, K. I. Lee, J. H. Koo, and S. H. Park. 2021. “Research on Cooperation Strategy with the Private Sector.” Korea Institute of Procurement, December. in Korean.

- Deloitte. 2021. “The Deloitte Global 2021 Millennial and Gen Z Survey.” Accessed March 16, 2022. https://www2.deloitte.com/content/dam/Deloitte/global/Documents/2021-deloitte-global-millennial-survey-report.pdf.

- Drucker, P. F. 1984. “Converting Social Problems into Business Opportunities: The New Meaning of Corporate Social Responsibility.” California Management Review 26 (2): 53–63.

- Dunleavy, P., and C. Hood. 1994. “From Old Public Administration to New Public Management.” Public Money & Management 14 (3): 9–16.

- Eom, E. 2017. “Localization of Oversea Korean Companies and CSR: Focusing on Cases in Indonesia.” Journal of the Association of Korean Geographers 6 (3): 479–493. in Korean

- Evans, P. 1995. Embedded Autonomy: States and Industrial Transformation. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Francis, T., and F. Hoefel. 2018. “‘True Gen’: Generation Z and its Implications for Companies.” McKinsey & Company, November 12. Accessed March 16, 2022. https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/consumer-packaged-goods/our-insights/true-gen-generation-z-and-its-implications-for-companies.

- Gibson, D., J. L. Gonzales, and J. Castanon. 2006. “The Importance of Reputation and the Role of Public Relations.” Public Relations Quarterly 51 (3): 15–18.

- Gomez, K., T. Mawhinney, and K. Betts. 2019. “Welcome to Generation Z.” Deloitte. Accessed March 16, 2022. https://www2.deloitte.com/content/dam/Deloitte/us/Documents/consumer-business/welcome-to-gen-z.pdf.

- Hall, R. 1993. “A Framework Linking Intangible Resources and Capabilities to Sustainable Competitive Advantage.” Strategic Management Journal 14: 607–618.

- Hemmige, H., M. Watters, and C. Daniel. 2021. “A Five-Step Agenda for Smarter Government Spending.” Boston Consulting Group, February 18. Accessed March 16, 2022. https://www.bcg.com/publications/2021/five-principles-to-manage-government-spending.

- Hodge, G. A., and C. Greve. 2016. “On Public-Private Partnership Performance: A Contemporary Review.” Public Works Management & Policy 22 (1): 55–78.

- Hodge, G. A., C. Greve, and M. Biygautane. 2018. “Do PPP’s Work? What and How have We been Learning so far?” Public Management Review 20 (8): 1105–1121.

- Hong, S., and T. K. Kim. 2018. “Public-Private Partnership Meets Corporate Social Responsibility – The Case of H-JUMP School.” Public Money & Management 38 (4): 297–304.

- Kim, S. 2010. “Collaborative Governance in South Korea: Citizen Participation in Policy Making and Welfare Service Provision.” Asian Perspective 34 (3): 165–190.

- Kim, S. G. 2015. “Development Cooperation and Global CSR: A Case Study of Automotive Technical Training Centre ODA Business in Ghana.” Journal of International Area Studies 19 (3): 3–30. in Korean.

- Kim, C. W., N. Y. Kim, and J. H. Yoo. 2019. “Will Everything Change with Generation Z?” Korea JoongAnkig Daily, February 10. https://koreajoongangdaily.joins.com/2019/02/10/industry/Will-everything-change-with-Generation-Z/3059215.html.

- Kim, T. H., J. M. Park, and M. J. Kim. 2018. “International Development Cooperation and Public-Private Partnership of Overseas Ports.” Regional Industry Review 41 (4): 159–176. in Korean.

- KOICA. 2021a. “2022 KOICA CTS Program Guidebook.” August. Accessed March 16, 2022. https://www.koica.go.kr/koica_kr/960/subview.do.

- KOICA. 2021b. “2022 KOICA IBS Program Guidebook.” June. Accessed March 16, 2022. https://www.koica.go.kr/koica_kr/961/subview.do.

- KOICA. 2022. “Development Innovation Program (DIP).” Brochure, December 28. Accessed March 16, 2022. https://www.koica.go.kr/koica_kr/959/subview.do.

- Koo, J. W., and S. G. Cho. 2017. “South Korean Media Coverage of Official Development Assistance: Topic Modelling Analysis of Six Print Media from 1993 to 2016.” Journal of International Area Studies 26 (3): 173–210. in Korean.

- Koo, J. W., Y. L. Kim, and D. W. Kim. 2015. “From Global Philanthropy to Creating Shared Values: Rethinking Public-Private Partnership in International Development Cooperation.” Journal of International Area Studies 24 (1): 75–113.

- Koppell, J. G. 2010. “Administration Without Borders.” Public Administration Review 70 (S1): S46–S55.

- Kramer, M., and J. Kania. 2006. “Changing the Game: Leading Corporations Switch from Defense to Offense in Solving Global Problems.” Stanford Social Innovation Review 4 (I): 22–29. doi:10.48558/GK61-B122.

- Kwak, J. S. 2012. “International Development, PPP, Issues and Implication.” Journal of International Development Cooperation 7 (1): 11–28. in Korean.

- Lee, C. M., and K. Botto. 2021. “Demographics and the Future of South Korea.” Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. June 29. Accessed March 16, 2022. https://carnegieendowment.org/2021/06/29/demographics-and-future-of-south-korea-pub-84817.

- Lee, Y. H., Y. J. Lim, and T. Y. Park. 2008. “Domestic Political Factors of the Rise of Governance.” 21st Century Political Science Review 17 (3): 169–198.

- Leibold, M., and S. C. Voelpel. 2007. Managing the Aging Workforce: Challenges and Solutions. Paris: Publicis.

- Lim, J. H., and D. Y. Chun. 2018. “A Review of Creating Shared Value (CSV) in Recent 7 Years (2011∼2017) in Korea.” Social Economy & Policy Studies 8 (1): 53–87. in Korean.

- Liverman, D. M. 2018. “Geographic Perspectives on Development Goals: Constructive Engagements and Critical Perspectives on the MDGs and the SDGs.” Dialogues in Human Geography 8 (2): 168–185.

- Ma, L., J. Li, R. Jin, and Y. Ke. 2019. “A Holistic Review of PublicPrivate Partnership Literature Published Between 2008 and 2018.” Advances in Civil Engineering Special Issue 2019: 1–18.

- Mandl, U., A. Dierx, and F. Ilzkovitz. 2008. “The Effectiveness and Efficiency of Public Spending.” Economic Papers 301. European Commission, 1-34. Accessed March 16, 2022. https://ec.europa.eu/economy_finance/publications/pages/publication11902_en.pdf.

- Mawdsley, E. 2018. “From Billions to Trillion’: Financing the SDGs in a World ‘Beyond Aid’.” Dialogues in Human Geography 8 (2): 191–195.

- Ministry of Trade, Industry and Energy. 2021. “K-ESG Guideline V1.0.” December, 1-176. Accessed June 9, 2022. in Korean.

- ODA Korea. 2022. “Annual Plan for International Development Cooperation of 2022.” International Development Cooperation Committee. January 27, 1-287. Accessed March 16, 2022. in Korean. http://www.odakorea.go.kr/contentFile/MSDC/40.pdf

- OECD.Stat. Total flows by donor (ODA + OOF + Private. Accessed March 16, 2021. oecd.org.

- Osborne, S. P. 2000. Public–Private Partnerships: Theory and Practice in International Perspective. London: Routledge.

- Osborne, S. P. 2006. “The New Public Governance?” Public Management Review 8 (3): 377–387.

- Park, S. W. 2022. “Reviewing ESG Based on International Political Philosophy: Possibility for Ethical Partnership Between Corporations, Nation, and the World?” Issue Briefing at the Institute of International Studies at Seoul National University 149: 1–8. in Korean.

- Planet People Productivity. 2021. “The Great Sustainability Bake-Off: CSR vs. ESG vs. SDG.” Accessed June 11, 2022. https://px3.org.uk/2021/04/29/the-great-sustainability-bake-off-csr-vs-esg-vs-sdg/.

- Porter, M. E., and M. R. Kramer. 2006. “Strategy and Society: The Link between Competitive Advantage and Corporate Social Responsibility.” Harvard Business Review 84 (12): 78–92.

- Prats, J. 2019. “The Governance of Public-Private Partnerships: A Comparative Analysis.” Cataloging-in-Publication data provided by the Inter-American Development Bank. Accessed March 16, 2022. https://publications.iadb.org/publications/english/document/The_Governance_of_Public-Private_Partnerships_A_Comparative_Analysis.pdf..

- Rhyu, S. 2005. “The Origins of Korean Chaebols and their Roots in the Korean War.” The Korean Journal of International Relations 45 (5): 203–230.

- Richey, L. A., and S. Ponte. 2014. “New Actors and Alliances in Development.” Third World Quarterly 35 (1): 1–21.

- Robinson, M. 2015. “From Old Public Administration to the New Public Service: Implications for Public Sector.” UNDP Global Centre for Public Service Excellence. Accessed March 16, 2022. https://www.undp.org/content/dam/undp/library/capacity-development/English/Singapore%20Centre/PS-Reform_Paper.pdf

- Ruiz Nunez, F., M. Tejada Ibanez, I. Franco Emerick Albergaria, N. Alreshaid, N.N. Aoudjhane, A. J. Jankowski, K. Khamudkhanov, J. Park, A. K. Srivastava, and D. Yurlova. 2020. “Benchmarking Infrastructure Development 2020: Assessing Regulatory Quality to Prepare, Procure, and Manage PPPs and Traditional Public Investment in Infrastructure Projects.” The World Bank Group, October 7. Accessed March 16, 2022.

- SDG Compass. 2015. “The Guide for Business Action on the SDGs.” Accessed March 16, 2022. https://sdgcompass.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/019104_SDG_Compass_Guide_2015.pdf

- Serafeim, G. 2020. “Social-Impact Efforts that Create Real Value.” Harvard Business Review, September-October 2020. https://hbr.org/2020/09/social-impact-efforts-that-create-real-value

- Sial, F., and J. Doucette. 2020. “Inclusive Partners? Internationalising South Korea’s Chaebol through Corporate Social Responsibility-Linked Development Cooperation.” Third World Quarterly 41 (10): 1723–1739.

- Sohn, H. S., B. K. Park, and N. K. Kim. 2014. “A Study on Korean Public-Private Partnership (PPP) for International Development Cooperation: Focusing on KOICA's Global CSR Program.” Journal of International Area Studies 23 (2): 121–155. in Korean.

- Solomon, J. M. 2010. “New Governance, Preemptive Self-Regulation, and the Blurring Boundaries in Regulatory Theory and Practice.” Wisconsin Law Review 2: 591–625.

- UNGC. 2021. “The SDGs Explained for Business.” Accessed March 16, 2022. www.unglobalcompact.org/sdgs/about

- Wang, H., W. Xiong, G. Wu, and D. Zhu. 2018. “Public-Private Partnership in Public Administration Discipline: A Literature Review.” Public Management Review 20 (2): 293–316.

- Weber, E. P., and A. M. Khademian. 2008. “Wicked Problems, Knowledge Challenges, and Collaborative Capacity Builders in Network Settings.” Public Administration Review 68 (2): 334–349.

- The World Bank Group. 2020. “Government Objectives: Benefits and Risks of PPPs.” Public-Private-Partnership Legal Resource Center. Accessed March 16, 2022. https://ppp.worldbank.org/public-private-partnership/overview/ppp-objectives

- You, J. S. 2005. “Embedded Autonomy or Crony Capitalism?: Explaining Corruption in South Korea, Relative to Taiwan and the Philippines, Focusing on the Role of Land Reform and Industrial Policy.” Paper presented at the annual meeting for the American Political Science Association, Washington, DC, September 1–4.

- Yuan, J., C. Wang, M. J. Skibniewski, and Q. Li. 2012. “Developing Key Performance Indicators for Public-Private Partnership Projects: Questionnaire Survey and Analysis.” Journal of Management in Engineering 28 (3): 252–264.