ABSTRACT

This study explores how the Japanese and Korean governments use multi-bi aid to complement their bilateral aid and compares their allocation behaviors. As opposed to traditional multilateral aid, multi-bi aid is earmarked for a specific country, project, region, sector, or theme. Japan—a traditional leading donor—and Korea—a small but growing donor—are considerably different in terms of their ODA history and size; although, they are comparable in meaningful manners in terms of their level of cooperation with multilateral organizations. Over the past 10 years, both countries used the multilateral system to a significantly lesser extent yet showed a higher proportion of earmarked funding within multilateral aid compared to the average DAC donor. This study identified more similarities than differences between Japan and South Korea—both countries commit a large proportion of their multi-bi to fragile and conflict-affected states, countries under-represented in their bilateral aid programs. Accordingly, a large proportion of their aid has been channeled through multilateral organizations leading the sectors that are not prioritized with their bilateral aid. Overall, this study identified strong complementarities between the composition of Japan’s and Korea’s bilateral and multi-bi aid.

Introduction

Since donors possess multiple motives for aid-giving, ranging from economic, political, security, and diplomatic reasons, donors have traditionally disbursed development assistance via bilateral or multilateral aid channels; choosing whichever channel best serves their motives. While there are particular strengths and weaknesses to each channel, donors tend to utilize bilateral channels if they seek predominantly to exercise influence over aid flows and build relationships with recipient countries (Gulrajani Citation2016; OECD Citation2020a). On the other hand, multilateral channels are best suited if donors are inclined to fund global challenges such as climate change, public health crises, and food scarcity by adopting collective approaches (Eichenauer and Reinsberg Citation2017; Gulrajani Citation2016, Citation2017). Multilateral aid is also referred to as core or non-earmarked aid, since it is pooled with other contributions and disbursed at the discretion of the agency without any restrictions (Kroll Citation2021).

Over the past two decades, a third form of development assistance, ‘multi-bi aid’ (alternatively referred to as earmarked, non-core, or trust funds) has grown massively, with a value that currently exceeds half of the total aid allocated to or through multilateral organizations (OECD Stat). The rise of multi-bi aid is associated with international agreements such as the Millennium Development Goals and the Paris Declaration’s principles for enhanced aid effectiveness (OECD Citation2009). As opposed to core aid, it supports specific development purposes, notably sectors, themes, regions, or modalities. Because of such features, multi-bi aid is often viewed as a vehicle for donors to widen their geopolitical ambitions. In fact, there has been a shift in the past twenty years in aid allocation patterns and aid composition to accommodate donors’ national interests (Gulrajani and Faure Citation2019; OECD Citation2015; Reinsberg, Michaelowa, and Eichenauer Citation2015). From the donor’s perspective, the advantage of earmarking funds is that they can utilize the expertise and professionalism of multilateral agencies, while still exercising influence over their aid activities. Moreover, multi-bi aid allows multilateral organizations to engage in contexts in which they would otherwise participate, not by their institutional limitations and restrictive mandate (Independent Evaluation Group Citation2011; Weaver Citation2008). In other words, UN agencies, for instance, are able to expand their activities beyond what is possible with core funding alone. Despite its advantage, the multi-bi has been criticized for various reasons, such as diminishing agencies’ operational flexibility, coordination, and coherent approaches to achieving their core mandates (Eichenauer and Reinsberg Citation2017; Gulrajani Citation2016, Citation2017). Nevertheless, donors are more likely to increase their multi-bi given how it appears to benefit them.

When Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) and Development Assistance Committee (DAC) members report on ODA, they provide a very different mix of bilateral, core, and earmarked funding. Thus, questions with regard to donors’ resource allocation decisions have been raised: How do donors distribute their development aid resources across different channels, and across different multilateral agencies? How may such choices add value to their development strategy? Scholars of development usually approach these questions with the assumption that multilateral aid is less political and legitimate since it is less specifically tied to donors’ development policy agendas (Girod Citation2012; Gulrajani Citation2016; Nunnenkamp and Thiele Citation2006; SIPPEL and NEUHOFF Citation2009). As a consequence, existing works focus on whether earmarking funding politicizes multilateral aid, undermining the pursuit of the core mandates and missions set by the broad membership (Barder, Ritchie, and Rogerson Citation2019; Eichenauer and Reinsberg Citation2017; OECD Citation2020b; Saez et al. Citation2021). Some studies found that donors politicize multilateral aid by matching multi-bi aid with their bilateral priorities (e.g. sectoral and country priorities) (Greenhill et al. Citation2016; Han Citation2021; Schneider and Tobin Citation2016). In other words, donors support multilateral agencies that share similar objectives, rather than those with a complementary focus. In contrast, other studies (Reinsberg Citation2017; Tadesse, Shukralla, and Fayissa Citation2017) found that donors allocate multi-bi aid to fund countries in which donors do not have a bilateral presence. Indeed, there is yet no consistent evidence or consensus. This study explores the details of multi-bi portfolios in order to contribute to the existing debate about whether bilateral and multi-bi channels are complements or substitutes in donors’ pursuit of their development goals. The result would suggest particular strengths and weakness to each channel that should at minimum enable donors to think strategically and fully exploit the advantages of each channel. This is important as the public demand for justification of aid giving is growing in many donor countries.

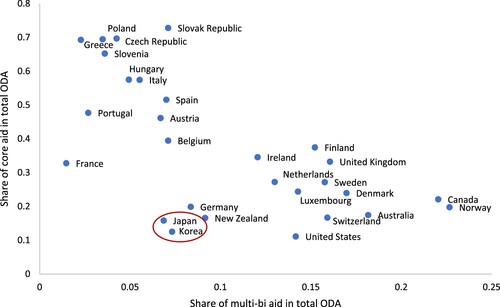

In this study, core funding combined with earmarked funding constitutes the total ‘multilateral ODA.’ This study focuses on two current DAC members, Japan and South Korea (hereafter referred to as Korea). As the DAC members, they are distinctly different. Japan joined the Development Assistance Group (DAG), the predecessor to the OECD-DAC in 1960 and has become one of the largest donors; contributing the fourth largest amount in 2020 (OECD, Stat). Korea joined the DAC in 2011. In 2022, Korea ranked 16th in total ODA volume with an ODA/GNI ratio of 0.14. Despite these differences, both countries use the multilateral system to a much lesser extent than other DAC donors: from 2011-2019, the percentage of the core aid in the total ODAFootnote1 was 16% for Japan and 12% for Korea; and the percentage of the multi-bi aid in the total ODA was 6.8% for Japan and 7.3% and Korea (see ). Both of these numbers are considerably below the DAC country average (37% for core aid and 10.5% for multi-bi aid).

Figure 1. Relative use of the multilateral system by OECD DAC countries (2011-2019).

Note: created by the author using data from the OECD CRS Stat.

Meanwhile, Japan and Korea have been two of the most widely criticized donor countries due to allegations that they prioritize national interests over the needs of recipient countries (Kalinowski and Cho Citation2012; Tonami and Müller Citation2013). These two countries share a set of characteristics that differentiate them from Western donors including their geographical and sectoral focus, grants and loans profile, and public-private links. These characteristics have, together, created an image of Japan’s and Korea’s aid as self-serving (Stallings and Kim Citation2017). Indeed, what distinguishes Japan and Korea from other Western donors is that their aid has not been only altruistic, but also about mutual benefits, global recognition, and economic interests (Kim and Oh Citation2012; Tonami and Müller Citation2013). While reinforcing potentially harmful self-interested behaviors for aid, they both also set long-term development objectives based on their experience and expertise in the following areas: poverty reduction, human security, gender equality, good governance, peace and prosperity, humanitarianism, and self-reliant sustainable development (Government of KOREA Citation2020; MOFA of Japan Citation2015). However, aid programs targeting humanitarian and peacebuilding represented an average of 3.4 and 6.5 percent of Japan and Korea’s bilateral aid in 2017-2020, remaining well below the DAC average of 11.3 percent (OECD, Stat). Overall, the two DAC countries are reasonably comparable in terms of their development policies and goals, as well as their use of the multilateral system, despite their substantial differences in ODA history and volume.

Although Japan and Korea are similar in their development policies, to the best of the author’s knowledge, no study has compared their multi-bi aid allocation preferences. Probing the application of multi-bi aid and describing important patterns in the application of this understudied aid channel in reference to the more often studied bilateral channel would provide important insights into the strategic decisions each country should make to sustain and carry forward their own development goals. Hereby, the main objective of this study is to review, describe, and analyze the multi-bi portfolio of Japan and Korea in detail and to discuss similarities and differences in their multi-bi approaches. In particular, the portfolio analysis seeks to identify how distinctive multi-bi aid is from bilateral aid by attempting to answer the following questions: (1) does multi-bi aid from Japan and Korea complement or act as a substitute for bilateral aid and enhance the value of Japanese and South Korean bilateral development efforts? (2) does multi-bi aid flows into substantially different areas than bilateral aid, and how strongly are they earmarked by donor governments? (3) how does the pattern of multi-bi aid allocation align with Japan’s and Korea’s development strategies? This study can help the Japanese and Korean governments to reflect on their own motives for aid allocation, justify the allocation choice between bilateral and multilateral channels, and strategize the role of each channel to pursue a greater role on the international stage. Consequently, this study may hold significant implications for countries that are seemingly less willing to interact with multilateral agencies by providing information that can be used to formulate new ways of expanding the scope of potential collaborations with multilateral agencies.

Lastly, this study has been conducted against the background of the COVID-19 pandemic and the unprecedented pressures it has placed on the international system. Looking at the increasing trend of earmarked funding to multilateral agencies would provide an indication of the factors that will influence the multilateral system in the future. Given the financial hardships caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, the development landscape is likely to see important changes in the coming period. This is because the unpredictable financial hardships may challenge donor countries to justify their investment in foreign aid, which will be reflected in the central question of what core tasks multilateral agencies should assume in the future. While donors have idiosyncratic reasons for using multilateral channels, examining whether multilateral agencies have the capacity to coordinate programs that are normally seen as less effective through bilateral channels (e.g. humanitarian and medical assistance) would influence donors, especially small donors, to increase their aid to the multilateral system, hoping to expand their influence in areas where they have limited capacity. Eventually, donors’ choices in the present will have important consequences on the visibility and survival of organizations in the coming years. Put differently, multilateral agencies may take advantage of the current characteristics of each donor’s contribution, for instance, nudging Japan and Korea to further focus on long-term projects in sectors of their interest. In addition, donors can expand their use of multi-bi channels within a like-minded coalition. Overall, this study can create the opportunity to rethink how donors and multilateral agencies can improve the way they interact with each other.

Methods

To examine the multi-bi aid portfolio of Japan and Korea, the study used data from the OECD-DAC Creditor Reporting System (CRS). This study used aid commitment instead of aid disbursement to explore donors’ intentions behind aid allocation decisions. This was done because the actual disbursement can be more volatile due to how it depends on the aid recipient countries or implementing organizations, which may fail to fulfill their commitments (Bulíř and Hamann Citation2001; Hudson Citation2013; Eichenauer and Reinsberg Citation2017). In practice, donors can exert full control over only their aid commitment. Data about DAC donors’ yearly commitment to each multilateral organization is only available from 2011 and onwards, but in the context of the multi-bi aid portfolio analysis, this is sufficient to conduct a meaningful analysis. The study covers from 2011 to 2019 as 2019 is the latest year available. The CRS data provides detailed information on earmarked contributions to multilateral organizations by sector, recipient countries, and implementing agencies. The data for the study period were pooled together for Japan and Korea since an individual year would provide meaningful data for comparative analysis.

In the first phase, this study reviews trends in multilateral aid flows from Japan and Korea over the period 2011-2019. By doing so, this study seeks to observe differences in their use of the multilateral system by tracking the flow of funds to multilateral agencies, sectors, and recipient countries. Notably, in this study, the total multilateral aid refers to the core and multi-bi aid combined.

Results

Overview of Korean and Japanese ODA

Between 2011-2019, the total ODA (bilateral, core, and multi-bi combined) for Japan and Korea averaged 23 billion USD and 2.4 billion per year (in real prices), of which 76.8 and 80.6% were bilateral aid respectively (OECD, Stat). While both donors are mindful of the need to achieve the 0.7% of ODA/GNI target, neither have met it, representing 0.29% and 0.15% of GNI in 2019 (Donor Tracker Citation2022a, Citation2022b). Japan, as a donor who has committed the largest amount of multilateral aid in the absolute term from the early 2000s, consistently showed similar figures; whereas Korea established a broadly upward overall growth trend from 2011 to 2019 (see ).

Table 1. the total ODA flows from Japan and South Korea.

On average, Japan allocated nine times more than Korea to the multilateral system from 2011-2019; yet within the total ODA, the share of the core and multi-bi has been similar between the two countries. Both donors allocated about 7% of their total ODA as earmarked contributions to multilateral organizations, although their annual commitments varied considerably from one year to the next. For instance, Korea’s multi-bi aid fell about 4% from 2015 to 2016 and then rebounded in 2017 by 44%. In the case of Japan, its multi-bi aid has been less volatile, but in 2018, its volume increased by 36% from the previous year and then fell by 48% in the following year due to decreased ODA in all channels. Within the multilateral total (core and multi-bi combined), after reaching the peak of 8.1 billion USD, it declined by 52% in 2019. While the flexibility of multi-bi aid gives donors the freedom to react to budgetary constraints at the national level, such unpredictable and volatile multi-bi aid can create management problems in multilateral organizations in terms of planning and delivering assistance (OECD Citation2018; Reinsberg, Michaelowa, and Knack Citation2015). Yet, the data suggests that, up to now, this type of aid has not been significantly more volatile than the core aid.

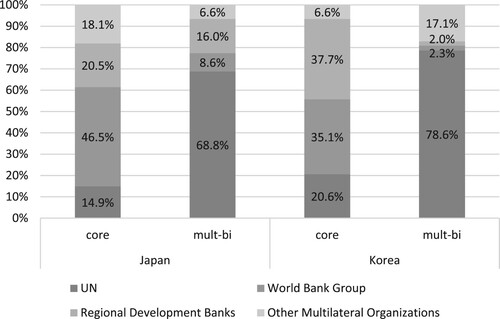

Donors decide to which multilateral organizations they contribute, how much, and whether the funding is provided as core or multi-bi. Within the multilateral total, the ratio of core to multi-bi contribution is 75:25 for both countries (Donor Tracker Citation2022b; Government of KOREA Citation2020). From 2011-2019, multilateral agencies—such as those under the UN, the World Bank Group, regional development banks, and vertical funding mechanismsFootnote2 like the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis, and Malaria (GFATM), and Green Climate Fund (GCF)—received significant volumes of multilateral aid (OECD Stat). Combined, the UN, World Bank Group, and regional banks accounted for 85.8 and 91.6% of Japan and Korea's ODA to multilateral agencies over the past 10 years respectively. When the core and multi-bi are observed separately, the two multilateral sources contrast (). The multilateral banks were the main contributor to the core, while the UN was the main contributor to the multi-bi for both countries.

Figure 2. Use of multilateral organizations for core and multi-bi aid (2011-2019).

Note: the author created this graph using data from OECD CRS (https://stats.oecd.org/Index.aspx?DataSetCode = CRS1).

Zooming into specific multilateral organizations, the International Development Association (IDA, the World Bank’s grant and concessional lending arm) has been the largest single recipient of Japan and Korea’s multilateral aid by far, accounting for about 29 and 14% of the total multilateral aid respectively (see ). In the case of Korea, almost all ODA given to the World Bank Group (IDA & IBRD) were core contributions, which means a minuscule part of Korea’s multi-bi aid has been allocated to World Bank-managed trust funds. This is laudable as the proliferation of small initiatives increases transaction costs and fragmentation in aid delivery (Gulrajani Citation2017; Reinsberg Citation2016). Yet, it is important to remember that some organizations act as a pass-through mechanism, providing funding to other multilateral organizations like the World Bank. Most pass-through multilateral organizations exist as global funds. Thus, for instance, being a member of the multilateral Global Environmental Facility (GEF) means that Korea ultimately channels earmarked funding to the World Bank. Hence, it is worth noting that the existing CRS, which only provides multi-bi data that is directly controlled by donors, makes it very difficult to obtain a more granular picture of the streams and practices around earmarked funding (Weinlich et al. Citation2020).

Table 2. Top 10 multilateral aid channels (2011-2019).

Most of Japan and Korea’s contributions to UN agencies were earmarked for specific purposes or countries. Such a high proportion of multi-bi aid to UN agencies may indicate that both donors’ development policies may align poorly with that of UN agencies because donors with priorities contrary to collective priorities set for multilateral organizations might use multi-bi aid as a substitute for core-funding (Eichenauer and Reinsberg Citation2014; OECD Citation2015).

Six recipients—IDA, IBRD, UNDP, World Food Programme (WFP), African Development Fund, and Asian Development Fund—ranked within the top 10 recipients of both countries. Both countries provided a significant portion of multilateral aid to multilateral organizations, providing humanitarian assistance in emergencies and insecure or refugee-dense environments. These include the WFP, the UN Children’s Fund (UNICEF), the UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), and the UN Department of Peace Operations (DPKO). Interestingly, as for the WFP, the portion of ‘earmarked’ aid was as high as 99.7% for Korea and 97% for Japan. Another significant portion of Japan’s and Korea’s multilateral aid went to multilateral organizations focused on advancing global health like the GFATM and World Health Organization (WHO) respectively.

Most multilateral organizations are funded through multi-year replenishment rounds. Given the strategic withholding of reserves and project cycle timetables, disbursements by multilateral agencies will never equal the ODA they receive from donors in any given year (OECD Citation2020d). The OECD CRS provides detailed information on aid disbursements and commitments. The detailed profiles in indicate that both countries’ multi-bi disbursement and commitment in all years have been fairly consistent; more than 90% of their aid scheduled for disbursement has been actually distributed according to donor records. Given that substantial discrepancies between disabused aid volumes and commitments were found by many donors in the past (Bulíř and Hamann Citation2001; Celasun et al. Citation2008), keeping a promise by fulfilling the commitment is still laudable. One notable difference between Japan and Korea is that, since 2011, Japan’s multi-bi aid has been unpredictable and volatile with a sudden drop in 2019; whereas Korea’s multi-bi showed less fluctuation. However, apart from Japan in 2019, it appears that both countries’ multi-bi has been on a rising trend.

Table 3. Details of multi-bi contributions of Japan and Korea.

Multi-bi contributions can range from very tight, highly customized, donor-driven projects, to soft (Weinlich et al. Citation2020). Although support for specific organizations is justified in some cases by describing the primary mandate of the organization, multi-bi contributions are, in general, justified by targeting funds to a specific country or sector, or by placing new issues on multilateral organizations’ agendas (Eichenauer and Reinsberg Citation2017; Reinsberg, Michaelowa, and Eichenauer Citation2015). For instance, donors may earmark their contributions by country, restricting funding to a single country even when the receiving organization has a global mandate. Broadly speaking, non-country-specific and programmatic funds are much less restrictive and softly earmarked; meaning the receiving organization decides how to allocate funding to specific projects within its overall programs (Eichenauer and Reinsberg Citation2014). In contrast, project-specific funds are most tightly earmarked, being associated with specific inputs, activities, and outputs with a certain amount of donor influence and visibility (Gulrajani Citation2017; OECD Citation2020a). For example, consider funding for the improvement of the sanitation sector for Syrian refugees in Jordan.

Most of Korea’s multi-bi aid after 2016 was project-based (see ). Of the 410 million USD of multi-bi aid in 2019, the lion’s share (65%) was allocated to specific projects; whereas for Japan, except for 2011, most of its multi-bi aid was categorized as programs. Indeed, a country earmark may ensure that funding reaches the people most in need and hence effectively respond to short-term requirements (e.g. post-conflict reconstruction). However, it also leaves the implementing agency with no flexibility to address the next unplanned crisis in other regions. Thus, even in cases where Korea has a clear rationale behind its use of multi-bi aid, it should carefully consider the long-term implications of its funding decisions. Moreover, projects with short durations (less than two years) and a rigid orientation towards tangible results can create problems around host government ownership and undermine the agency’s ability to tackle complex issues in a sustainable manner (Weinlich et al. Citation2020). In fact, soft earmarking can bring agencies together for improved coherence.

In the CRS, data on the sector are recorded using 5-digit purpose codes. The first three digits of the code refer to the corresponding sector or category. For a sectoral analysis, this study adopted the first three digits of a five-digit CRS code (OECD Citation2019). The sectoral allocation was found using the average of the total amount spent on each sector annually for the 2011–2019 period. Over the past decade, Japan has contributed profoundly to recipient countries’ economic infrastructure, allocating nearly 50% of its bilateral aid to economic infrastructure and services (see ). For the last ten years, the transport and storage and energy sectors have always received the largest share of bilateral aid from Japan. Similarly, Korea’s bilateral aid also focused on building economic infrastructure and production capacity including industrial development, which can be interpreted as aid for improving trading capacity. While the largest share of bilateral aid, in terms of a specific sector, went to the transport and storage sector, in terms of a general category, social development sectors (codes in 100 levels) received the largest bilateral aid. This implies that Korea’s bilateral aid allocation between social and economic development has been relatively well balanced compared to Japan. With multi-bi aid, both donors showed a strong preference for emergency response, development food assistance, and reconstruction relief. Both allocated significantly a larger share of multi-bi to those respective activities. In addition, both countries, especially Japan, contributed a large share of ODA for multi-sector development through multilateral agencies. One notable difference between the two regards supporting the government and civil society sector: the Japanese government mainly utilized multilateral channels, and the Korean government utilized both bilateral and multilateral channels at similar levels with 7.1 and 12.1%.

Table 4. Sectoral allocation of bilateral vs. multi-bi aid (2011-2019)

This analysis detects two noteworthy features of multi-bi aid allocation. First, both countries’ multi-bi aid is concentrated in a few sectors and allocated very unequally. Second, both countries’ purposes for multi-bi aid greatly differ from that of their bilateral programs. It is clear that humanitarian purposes are a high multi-bi priority for both countries, while their bilateral aid is more centered on economic growth. This suggests that both countries consider multi-bi aid as a mechanism for pooling funding and risk toward global public good provisions such as security and natural hazards concerns.

illustrates a key rationale for multi-bi aid, notably the support for specific countries. Compared to the bilateral aid recipients in , both donors’ multi-bi aid is centered on fragile and conflict-affected states that are under-represented in bilateral aid programs. Fragile and conflict-affected states are marked with a bracket [F] for easy recognition. This result suggests that both countries prefer to provide aid through multi-bi channels in difficult environments to share burdens and mitigate individual risks. Put differently, both Japan and Korea can raise their visibility in those countries given that donors, not only these two, are reluctant to interfere in states characterized by low democratic activity, an absence of public services, corruption, and a weak legal system (Devarajan Citation2009; Hayman Citation2011). Within the multi-bi total, the share for these top 10 countries was approximately the same at 38%.

Table 5. Top 10 multi-bi aid recipient countries of South Korea and Japan (2011-2019).

Table 6. Bilateral priority countries of Japan and Korea.

Also distinguishable was the largest beneficiary of both countries. Both countries provided the largest amount of funding to Afghanistan, allocating about 21% and 18% of their total multi-bi aid respectively from 2011-2019. However, their multi-bi aid declines rapidly when arranged by share. This indicates that both countries tend to allocate a small, yet even-sized, amount of funding across the individual recipient. Another noticeable similarity is the funding size across the individual aids. Except for Afghanistan, for which the mean of Japan and Korea’s aid were 54.3 and 13.2 million USD respectively, the mean of the aid for the remaining nine recipients was 3.7 and 1.8 million USD for Japan and Korea respectively. From 2011 to 2019, about 76% of Korea-funded aid projects each totaled less than 1 million USD compared to 50% of aid projects funded by Japan. This is further evidence that both donors distribute their funding across recipient countries and specific aid projects. In terms of total spending, it is notable that the Syrian Arab Republic hosted the largest number of Japanese and Korean aid projects, and it received 4.5 times more aid (234 million USD) from Japan than it received from Korea (51 million USD).

Korea selects priority partner countries every five years based on recipient countries’ income level, political situation, diplomatic relations with Korea, and economic cooperation potential (Government of Korea Citation2016; Government of KOREA Citation2020). While Japan does not select priority countries or targets for apportioning its ODA, instead, Japan considers its own foreign policy, the role of the country in the region, and its own influence, as well as its absorptive capacity when deciding allocations (OECD Citation2020c). shows the top 25 countries that received the largest amount of Japan’s bilateral aid over the past decade. These countries received approximately 68.5% of Japan’s bilateral total over 2011-19. In the case of Korea, for the period of 2011-2015, 26 priority countries were selected. For the next round (2016-2020), Korea selected 24 countries. There are many countries who were selected in both the first round and the second round, implying that Korea made little change in its regional focus on bilateral aid. To enhance aid effectiveness, the Korean government concentrates at least 70% of its bilateral aid on assisting those 24 countries.

This analysis found some noteworthy features of the two countries’ aid. First, bilateral aid and multi-bi aid are directed towards different priority countries. Of the top 10 recipients of Japan’s multi-bi aid, only two countries (Afghanistan and Pakistan) were also ranked within the top 25 recipients of Japan’s bilateral aid. For Korea, only four countries (Afghanistan, Ethiopia, Philippines, and Tanzania) were ranked on both lists ( and 6). This result suggests that Korea leaned more toward its bilateral aid priority countries with its multi-bi aid, compared to Japan. Furthermore, as seen in , both countries’ priority countries are comprised primarily of politically stable countries, allocating nearly all bilateral aid for lower-middle income and even upper-middle-income countries. In 2019, 92% and 85.6% of Japan and Korea’s bilateral aid targeted middle-income countries respectively, of which 11% (Japan) and 6.5% (Korea) targeted upper-middle-income countries. Only 7.5% of Japan’s aid targeted low-income countries. Despite Korea’s commitment to low-income countries being double in share (14.5%), it was significantly different from the DAC average of 30% of bilateral aid to low-income countries. Of Japan’s top 25 recipient countries, only three (Afghanistan, DR Congo, and Mozambique) are classified as low-income countries, whereas the respective number for Korea was four (Ethiopia, Mozambique, Rwanda, and Uganda).

This result indicates that the target countries and themes differ between the multi-bi and the bilateral aid. Both Japan and Korea may consider multi-bi aid to be better positioned to assist fragile states as it utilizes multilateral agencies’ expertise and professionalism— skills, and knowledge accumulated over a long time in those states. Obviously, both countries are pursuing geographic (Asia) and thematic priorities (economic development) through bilateral funding, and their multi-bi aid can help expand their influence in areas where they have limited capacity. This suggests that both countries use multi-bi aid in a way that is complementary to their bilateral aid.

Discussion

Strong complementarities between the composition of Japan’s and Korea’s bilateral and multi-bi aid suggest that both countries need to assess and strategize the role of their multi-bi aid as an aid channel over bilateral aid to achieve the goals set based on human security, equality, and peacebuilding. Multilateral agencies with in-depth knowledge of particular regional or country contexts compared with foreign affairs ministries would help the governments to provide tailored support for diverse regional needs. Korea’s aid in particular, as a small aid provider, may be better served using multi-bi channels given opportunities for achieving economies of scale and efficiency gains through a pooling of resources (Dreher, Simon, and Valasek Citation2021).

In practice, the complex and fragmented administrative procedures and structures—one of the chronic problems for both countries—may prohibit them from making efficient interactions with multilateral agencies (Gulrajani Citation2016; Hirata Citation1998; Kwon et al. Citation2020). For example, there is no shared priority among ministries on their own commitments and no inter-ministry collaboration in the budget acquisition process (Nomura et al. Citation2020). As a result, government bodies are aiding numerous multilateral agencies with overlapping contributions and programs. That being said, as for limiting excessive aid dispersion, both governments should develop overarching and coherent strategies to set priories among competing policies of the government bodies. This would help them, at least, decide whether they need to shift funding from some channels to others to adapt to emerging challenges while achieving their goals with the funding type.

The discussion of encouraging more interaction with multilateral agencies reflects the central question of what tasks these agencies should assume in the future. As discussed earlier, some trends related to the COVID-19 pandemic meant development agencies have rarely stood still. If they are to endure and progress further in the post-COVID aid landscape, donors will need to recognize their value. It is important that multilateral agencies adjust their priorities and cooperation approaches in response to changing agendas at global, donor, and partner country levels to justify their existence and relevance to the extent to which their core mission is not undermined.

Lastly, both Japan and Korea do not have an established systematic aid assessment program. Besides assessing multilateral effectiveness through the Multilateral Organization Performance Assessment Network (MOPAN), there are no indicators in place that can measure multilateral contributions. Scattered funding due to the fragmented structure makes it even more difficult for the government to learn what works in the overall results reporting, and to use the findings of evaluations to feed into decision-making accordingly. Each country developing more strategic evaluations and demanding their partner agencies to use the feedback as part of the performance improvement process would, in turn, help them deliver on their mandates and enhance their actual impact.

Conclusion

This study explores how the government of Japan and Korea uses multi-bi aid to complement bilateral aid and compares their allocation behaviors through the portfolio analysis of their multi-bi contributions to multilateral organizations. As opposed to traditional multilateral aid, multi-bi aid is earmarked for a specific country, project, region, sector, or theme. Japan—a traditional leading donor—and Korea—a small but growing donor—are considerably different in terms of their ODA history and size, but they are comparable in meaningful ways in terms of their level of cooperation with multilateral organizations. Over the past 10 years, both countries used the multilateral system to a significantly lesser extent than other DAC donors yet showed a higher proportion of earmarked funding within multilateral aid compared to the average DAC donor. In summary, as one of the world's top contributors to ODA, Japan’s multilateral aid (core and earmarked) has been massive but has remained stagnant over the past 10 years. In contrast, Korea has gradually increased its multilateral funding in absolute terms since it joined the DAC in 2010.

While bilateral and multilateral channels are distinctive aid conduits, this study found sufficient reason to see them as possible complements from Japan’s and Korea’s perspectives. This finding is similar to previous work (Eichenauer and Reinsberg Citation2017; Independent Evaluation Group Citation2011; Nunnenkamp and Thiele Citation2006; SIPPEL and NEUHOFF Citation2009) that identified how bilateral and multi-bi portfolios are different; multi-bi aid has a strong orientation toward humanitarian and security concerns while bilateral aid is directed toward commercial and geopolitical ones. Both countries utilize each channel for different development and humanitarian purposes, often covering different regions and sectors. While the bilateral aid of both countries is skewed toward Asian countries, a large proportion of their multi-bi aid is allocated to fragile and conflict-affected states and countries under-represented in their bilateral aid programs. Accordingly, a large proportion of their aid has been channeled through multilateral organizations that are leaders in sectors that the donors prioritize less with their bilateral aid. Examples are the WFP, UNICEF, UNHCR, and WHO whose primary responsibility is to deliver humanitarian aid and health services. This may suggest that both donors use multi-bi aid to enhance their visibility in countries where they have a small presence. In other words, their multi-bi aid is pursuing what their bilateral aid cannot achieve. In some sense, multi-bi aid appears to be a better option to accomplish their goals in relation to peace and security; both countries have yet to accomplish those goals with their bilateral aid as it centered more on economic growth in recipient countries.

It is also found that the size of Korea’s multilateral funding, and Japan’s to a lesser extent, has been volatile over the past 10 years. The volatility of multi-bi aid has been perceived as a risk, which burdens the multilateral system with management problems in terms of planning long-term development strategies (OECD Citation2018; Reinsberg, Michaelowa, and Knack Citation2015). This means that multilateral organizations, especially the UN agencies receiving a large proportion of funding as earmarked, will face challenges in scaling up existing activities with unpredictable funding. Given the findings imply that multilateral agencies can be an important tool for both Japan and Korea for fulfilling their development goals related to human security, the volatility of multilateral contributions must be addressed in the near future. Korea is found to exert tighter control over its multi-bi aid compared to Japan since a large share of multi-bi funding was organized as a project, which is known to be most tightly earmarked with a specific development theme (Gulrajani Citation2017). In contrast, programmatic funds were a more common type for Japan. This may be attributed to the fact that Korea is a small donor with less influence over multilateral organizations than Japan. Tight earmarking may be a means by which Korea can exert a greater degree of control over funding allocation and gain greater visibility for their contributions; other donors often do this as well (OECD Citation2014). However, Korea may earmark funding to specific purposes in line with its internal and strategic interests. Whatever their intention, if Korea’s tight earmarked contributions continue, the country will be criticized for fostering fragmentation and competition between multilateral agencies, and this may affect the coherence and pursuit of common results (Medinilla, Veron, and Mazzara Citation2019). Going forward, if Korea is serious about its commitment to its selected sectors and countries, it will have to support the implementing agencies at least with predictable consistency and align with those agencies’ core strategic plans.

The findings of this study raise interesting questions that necessitate future research. First, it does not provide a definite answer to the causality as well as the effectiveness of multi-bi aid. Any empirical relation between the donors’ channel choices and aid effectiveness should be established. Second, we know very little about how the Japanese and Korean governments should balance bilateral and multi-bi aid, which are largely different, in a way to maximize gains and pursue development goals. There should be a deeper portfolio analysis of individual development agencies in order to gain a more comprehensive understanding of Japan and Korea’s multi-bi approach.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 ODA in commitment as it better shows donors’ intentions with regard to using ODA.

2 Classified as other multilateral organizations

References

- Barder, O., E. Ritchie, and A. Rogerson. 2019. “Contractors or Collectives?” Earmarked Funding of Multilaterals, Donor Needs and Institutional Integrity: The World Bank as a Case Study. Washington, DC: Center for Global Development. Retrieved from Center for Global Development website: https://www.cgdev.org/publication/contractors-or-collectives-earmarked-funding-multilaterals-donor-needs-and.

- Bulíř, A., and A. J. Hamann. 2001. “How Volatile and Unpredictable Are Aid Flows, and What Are the Policy Implications?” IMF Working Papers 2001 (167), doi:10.5089/9781451858181.001.A001.

- Celasun, O., J. Walliser, J. Tavares, and L. Guiso. 2008. “Predictability of Aid: Do Fickle Donors Undermine Aid Effectiveness? [with Discussion].” Economic Policy 23 (55): 545–594.

- Devarajan, S. 2009. “Aid and Corruption.” Retrieved March 24, 2021, from https://blogs.worldbank.org/africacan/aid-and-corruption.

- Donor Tracker. 2022a, May 21. “South Korea.” Retrieved June 5, 2022, from https://donortracker.org/country/south-korea.

- Donor Tracker. 2022b, May 25. “Japan.” Retrieved June 5, 2022, from https://donortracker.org/country/japan.

- Dreher, A., J. Simon, and J. Valasek. 2021. “Optimal Decision Rules in Multilateral aid Funds.” The Review of International Organizations 16 (3): 689–719. doi:10.1007/s11558-020-09406-w.

- Eichenauer, V. Z., and B. Reinsberg. 2014, December. “Multi-Bi Aid: Tracking the Evolution of Earmarked Funding to International Development Organizations from 1990 to 2012 (Codebook) [Research Reports or Papers].” Retrieved June 5, 2022, from https://www.ethz.ch/content/dam/ethz/special-interest/gess/cis/cis-dam/Research/Working_Papers/WP_2014/CIS_WP_84.pdf.

- Eichenauer, V. Z., and B. Reinsberg. 2017. “What Determines Earmarked Funding to International Development Organizations? Evidence from the new Multi-bi aid Data.” The Review of International Organizations 12 (2): 171–197.

- Girod, D. M. 2012. “Effective Foreign Aid Following Civil War: The Nonstrategic-Desperation Hypothesis.” American Journal of Political Science 56 (1): 188–201.

- Government of Korea. 2016. “2nd Mid-Term Strategy for Development Cooperation (2016-2020) (in Korean).” Sejong, Korea. Retrieved from https://www.mofa.go.kr/www/brd/m_4080/view.do?seq=357022&srchFr=&%3BsrchTo=&%3BsrchWord=&%3BsrchTp=&%3Bmulti_itm_seq=0&%3Bitm_seq_1=0&%3Bitm_seq_2=0&%3Bcompany_cd=&%3Bcompany_nm=&page=269.

- Government of KOREA. 2020. “3rd Mid-Term Strategy for Development Cooperation (2021-2025) (in Korean).” Sejong, Korea. Retrieved from https://www.odakorea.go.kr/contentFile/MSDC/03.pdf.

- Greenhill, R., G. Rabinowitz, M. A. J. d’Orey, and A. Prizzon. 2016. Why do Donors Delegate to Multilateral Organisations? A Synthesis of six Country Case Studies. London, UK: Overseas Development Institute. Retrieved from Overseas Development Institute website: https://odi.org/en/publications/why-do-donors-delegate-to-multilateral-organisations-a-synthesis-of-six-country-case-studies/.

- Gulrajani, N. 2016. Bilateral Versus Multilateral aid Channels: Strategic Choices for Donors. London, UK: Overseas Development Institute. Retrieved from Overseas Development Institute website: https://odi.org/en/publications/bilateral-versus-multilateral-aid-channels-strategic-choices-for-donors/.

- Gulrajani, N. 2017. Five Steps to Smarter Multi-bi aid: A new way Forward for Earmarked Finance. London, UK: Overseas Development Institute. Retrieved from Overseas Development Institute website: https://odi.org/en/publications/five-steps-to-smarter-multi-bi-aid-a-new-way-forward-for-earmarked-finance/.

- Gulrajani, N., and R. Faure. 2019. “Donors in Transition and the Future of Development Cooperation: What do the Data from Brazil, India, China, and South Africa Reveal?” Public Administration and Development 39 (4–5): 231–244. doi:10.1002/pad.1861.

- Han, B. 2021. “Strategic Portfolio Building in Donors’ Multilateral Institutional Choice.” East Asian Economic Review 25 (4): 339–360. doi:10.11644/KIEP.EAER.2021.25.4.400.

- Hayman, R. 2011. “Budget Support and Democracy: A Twist in the Conditionality Tale.” Third World Quarterly 32 (4): 673–688.

- Hirata, K. 1998. “New Challenges to Japan’s Aid: An Analysis of Aid Policy-Making.” Pacific Affairs 71 (3): 311. doi:10.2307/2761413.

- Hudson, J. 2013. “Promises Kept, Promises Broken? The Relationship Between aid Commitments and Disbursements.” Review of Development Finance 3: 109–120. doi:10.1016/j.rdf.2013.08.001.

- Independent Evaluation Group. 2011. Trust Fund Support for Development: An Evaluation of the World Bank’s Trust Fund Portfolio. Washington, DC: World Bank. Retrieved from World Bank website: https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/21345.

- Kalinowski, T., and H. Cho. 2012. “Korea’s Search for a Global Role Between Hard Economic Interests and Soft Power.” The European Journal of Development Research 24 (2): 242–260. doi:10.1057/ejdr.2012.7.

- Kim, E. M., and J. Oh. 2012. “Determinants of Foreign Aid: The Case of South Korea.” Journal of East Asian Studies 12 (2): 251–274. Retrieved from JSTOR.

- Kroll, G. 2021. A Changing Landscape: Trends in Official Financial Flows and the Aid Architecture. Washington, DC: World Bank Group. p. 50. https://thedocs.worldbank.org/en/doc/9eb18daf0e574a0f106a6c74d7a1439e-0060012021/original/A-Changing-Landscape-Trends-in-Official-Financial-Flows-and-the-Aid-Architecture-November-2021.pdf. Retrieved from https://thedocs.worldbank.org/en/doc/9eb18daf0e574a0f106a6c74d7a1439e-0060012021/original/A-Changing-Landscape-Trends-in-Official-Financial-Flows-and-the-Aid-Architecture-November-2021.pdf.

- Kwon, H., T. Kim, S. G. Kim, E. Kim, and S. Lee. 2020. “New Directions of International Development Cooperation for Korea.” Korea Association of International Development and Cooperation 12 (1): 1–17. doi:10.32580/idcr.2020.12.1.1.

- Medinilla, A., P. Veron, and V. Mazzara. 2019. EU-UN Cooperation: Confronting Change in the Multilateral System. The Netherlands: European Centre for Development Policy Management, p. 52.

- MOFA of Japan. 2015. “Japan’s Official Development Assistance Charter. Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan.” Retrieved from Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan website: https://www.mofa.go.jp/files/000067701.pdf.

- Nomura, S., H. Sakamoto, M. K. Sugai, H. Nakamura, K. Maruyama-Sakurai, S. Lee, A. Ishizuka, and K. Shibuya. 2020. “Tracking Japan’s Development Assistance for Health, 2012–2016.” Globalization and Health 16 (1): 32. doi:10.1186/s12992-020-00559-2.

- Nunnenkamp, P., and R. Thiele. 2006. “Targeting Aid to the Needy and Deserving: Nothing But Promises?” The World Economy 29 (9): 1177–1201. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9701.2006.00836.x.

- OECD. 2009. Managing Aid PRACTICES OF DAC MEMBER COUNTRIES. Paris, France: OECD. Retrieved from OECD website: https://www.oecd.org/dac/peer-reviews/35051857.pdf.

- OECD. 2014. Making Earmarked Funding More Effective: Current Practices and a way Forward. Paris, France: OECD. Retrieved from OECD website: https://www.oecd.org/dac/aid-architecture/Multilateral%20Report%20N%201_2014.pdf.

- OECD. 2015. Multilateral Aid 2015: Better Partnerships for a Post-2015 World. Paris: Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. Retrieved from https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/development/multilateral-aid-2015_9789264235212-en.

- OECD. 2018. Multilateral Development Finance: Towards a New Pact on Multilateralism to Achieve the 2030 Agenda Together. Paris: Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. Retrieved from https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/development/multilateral-development-finance_9789264308831-en?itemId=/content/component/9789264308831-11-en&_csp_=760789477e526fb642a524e2927ce2ca&itemIGO=oecd&itemContentType=chapter.

- OECD. 2019. “Purpose Codes: Sector classification - OECD.” Retrieved March 5, 2022, from https://www.oecd.org/dac/financing-sustainable-development/development-finance-standards/purposecodessectorclassification.htm.

- OECD. 2020a. Earmarked Funding to Multilateral Organisations: How is it Used and What Constitutes Good Practice? Paris, France: OECD. Retrieved from OECD website: https://www.oecd.org/dac/financing-sustainable-development/development-finance-topics/Multilateral-development-finance-brief-2020.pdf.

- OECD. 2020b. Multilateral Development Finance 2020. Paris: Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. Retrieved from https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/development/multilateral-development-finance-2020_e61fdf00-en.

- OECD. 2020c. OECD Development Co-Operation Peer Reviews: Japan 2020. Paris: Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. Retrieved from https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/development/oecd-development-co-operation-peer-reviews-japan-2020_b2229106-en.

- OECD. 2020d. “What is the Difference Between a Commitment and a Disbursement? Updated 2020. Retrieved June 5, 2022, from https://www.oecd.org/dac/financing-sustainable-development/development-finance-data/faq.htm.

- Reinsberg, B. 2016. “The Implications of Multi-bi Financing for Multilateral Agencies: The Example of the World Bank.” In The Fragmentation of Aid, edited by S. Klingebiel, T. Mahn, and M. Negre, 185–198. London: Palgrave Macmillan UK. doi:10.1057/978-1-137-55357-7_13.

- Reinsberg, B. 2017. “The Use of Multi-bi aid by France in Comparison with Other Donor Countries.” In Working Paper (No. 3c664604-b408-4a2c-bf46-5d20470fe0e0). Agence Française de Développement. Retrieved from Agence française de développement website: https://ideas.repec.org/p/avg/wpaper/en7732.html.

- Reinsberg, B., K. Michaelowa, and V. Z. Eichenauer. 2015. “The Rise of Multi-bi aid and the Proliferation of Trust Funds.” In Handbook on the Economics of Foreign Aid, edited by B. Arvin, and B. Lew, 527–554. Washington: Edward Elgar Publishing. doi:10.4337/9781783474592.00041.

- Reinsberg, B., K. Michaelowa, and S. Knack. 2015. Which Donors, Which Funds? : The Choice of Multilateral Funds by Bilateral Donors at the World Bank. Washington, DC: World Bank. Retrieved from World Bank website: https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/22872.

- Saez, P., L. Sida, R. Silverman, and R. Worden. 2021. Improving Performance in the Multilateral Humanitarian System: New Models of Donorship - World | ReliefWeb. Washington, DC: Center for Global Development. Retrieved from Center for Global Development website: https://reliefweb.int/report/world/improving-performance-multilateral-humanitarian-system-new-models-donorship.

- Schneider, C. J., and J. L. Tobin. 2016. “Portfolio Similarity and International Development Aid.” International Studies Quarterly 60 (4): 647–664. doi:10.1093/isq/sqw037.

- SIPPEL, M., and K. NEUHOFF. 2009. “A History of Conditionality: Lessons for International Cooperation on Climate Policy.” Climate Policy 9 (5): 481–494. doi:10.3763/cpol.2009.0634.

- Stallings, B., and E. M. Kim. 2017. South Korea as an Emerging Asian Donor. In Development Cooperation and Non-Traditional Security in the Asia-Pacific. Promoting Development: The Political Economy of East Asian Foreign Aid. Palgrave Macmillan. 81-116. doi:10.1007/978-981-10-3165-6

- Tadesse, B., E. Shukralla, and B. Fayissa. 2017. “Are Bilateral and Multilateral aid-for-Trade Complementary?” The World Economy 40 (10): 2125–2152. doi:10.1111/twec.12485.

- Tonami, A., and A. R. Müller. 2013. Japanese and South Korean Environmental Aid 26.

- Weaver, C. 2008. Hypocrisy Trap: The World Bank and the Poverty of Reform. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Weinlich, S., M.-O. Baumann, E. Lundsgaarde, and P. Wolff. 2020. “Earmarking in the Multilateral development System: Many Shades of Grey.” Studies. doi:10.23661/S101.2020.