ABSTRACT

International and national actors are increasingly calling for a double or triple nexus approach to humanitarian, development, and peace activities to improve the flexibility of programming, particularly in complex crises. The double or triple nexus approach can, however, also replicate or create new challenges. To avoid this, the double and triple nexus requires more nuance. We explore how the double and triple nexus raises concerns about (1) control and decision-making, (2) the potential to cause harm, and (3) impositions that create inefficiencies, aspects of the double and triple nexus that are rarely considered. As actors seek to integrate and align activities via double and triple nexus approaches, they must proactively set in place policies to avoid negative consequences through localization to avoid replicating unequal control and decision-making. To ensure ‘do no harm’ is upheld, actors must consider the pace and scale of double and triple nexus implementation. As actors tend to have specific capacities, double or triple nexus impositions may create inefficiencies in operationalization which coordination and collaboration can reduce with significant investment.

Introduction

Humanitarian, development, and peace actions are often funded and implemented in distinct ways, within unique operational paradigms, and by different actors. However, certain contexts require humanitarian, development, and peace actions in parallel, either geographically or temporally. Additionally, many circumstances require flexibility to shift between programming modalities due to changing contexts. Due to these realities, intergovernmental, governmental, and non-governmental agencies have called for a nexus approach which has had two distinct iterations, the humanitarian-development nexus and the humanitarian-development-peace nexus, the former emerging in literature and practice prior to the latter (ICVA Citation2017; OCHA Citationn.d.; UNDP Citationn.d.). For ease of readability, and as both are studied within this article, we hence forth will be referring to the humanitarian-development nexus as the ‘double nexus’ and the humanitarian-development-peace nexus as the ‘triple nexus’.

The double and triple nexus are presented by the United Nations (UN) as an approach to assistance that requires broad partnership amongst UN agencies, non-governmental organizations (NGOs), civil society organizations (CSOs), the private sector, and governments, but also as a need for internal reform (ICVA Citation2017). The United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) and United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) in particular, have emerged as some of the leading UN agencies in advancing the double and triple nexus agenda which the OCHA describes as an assistance program that is working to achieve collective outcomes (ICVA Citation2017; OCHA Citationn.d.; UNDP Citationn.d.). According to a statement made by the UN Secretary General, the organization’s aim is to enhance collaboration across UN subsidiaries, a goal shared by both the double and triple nexus, while also placing greater emphasis on instability, exclusion, vulnerability, and conflict prevention, marking a distinct shift towards the dominance of the triple nexus in the international sphere (ECOSOC Citation2017).

The UN and its subsidiaries draw on the 2030 Agenda and Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) as their justification of the need for a triple nexus approach (ECOSOC Citation2017). For example, the 2030 Agenda’s assertion that sustainable development is not possible in the absence of peace, and that peace is not possible in the absence of sustainable development, provide the UN and its partners a unique opportunity to use the triple nexus to address the root causes of the issues highlighted in the SDGs (ECOSOC Citation2017). Moreover, the UN, along with its partners, see the 2030 Agenda and the SDGs as inherently tied to the concept of the triple nexus as they both set out to reduce risk, vulnerability, and need, and therefore cannot be separated (ECOSOC Citation2017). The specifics of the definitions and justifications for this call, however, vary amongst actors. As discussed below, the call for both the double and triple nexus is prevalent and we support the call for nexus approaches. What concerns us, however, is the lack of consideration of ‘unintended consequences’, which have the potential to replicate failures of the past in new forms.

‘Unintended consequences,’ in this context, relating to Robert K. Merton’s (Citation1936) essay on the matter entitled The Unanticipated Consequences of Purposive Social Action, which states that unintended consequences are the direct result of social action, which discussion of the double or triple nexus can be considered to be (Davidson et al. Citation2022). Furthermore, Merton (Citation1936) goes on to attribute these unanticipated consequences on (1) a lack of knowledge or, in Merton’s words, ‘ignorance’, (2) ‘error,’ specifically, yet not solely, as a result of habit and neglect, (3) the consideration of the immediate over the future implications of social action, and (4) the assumption, in the prediction of consequences by agents of social action, that all other elements of a society, aside from the elements which are the target of social action, will remain the same, an unlikely outcome in the face of social change. Therefore, this article seeks to address and minimize Merton’s (Citation1936) causes of unintended consequences in relation to the operationalization of the double and triple nexus by (1) analyzing existing academic literature and reports on the topic in order to find neglected areas of study, (2) identifying repeated areas of complication across various development programming initiatives to avoid similar neglect during double and triple nexus discussions, and (3) identifying and discussing potential short- and long-term implications of the double and triple nexus on both organizations and societies. This article, therefore, builds upon existing challenges (programmatic, financial, organizational) and identifies three areas we believe require more attention, namely: (1) control and decision-making, (2) potential to cause harm, and (3) impositions that create inefficiencies.

This article begins by specifying the aim and research questions that guided this paper, followed by a contextualization of the double, and subsequently triple, nexus’s history, outlining four generations of its development over time by identifying their changing focus areas and priorities. We then go on to outline the methodology employed for this article, which includes a multi-platform systematic review of literature, seeking out both academic and nonacademic literature, along with its limitations. We then go on to discuss the results of this systematic review in our results and discussion section titled ‘Nuancing the Nexus.’ This section’s key contributions are the three areas, (1) control and decision-making, (2) potential to cause harm, and (3) impositions that create inefficiencies, we suggest need nuance, making our case by situating these areas within our findings from the existing literature while also contextualizing their importance when designing and implementing double or triple nexus approaches.

Aim & research questions

This research paper aims to analyze the pre-existing literature on the humanitarian-development nexus and the humanitarian-development-peace nexus, identify any existing gaps, and discuss these gaps’ potential to increase negative, ‘unintended consequence’ vulnerabilities, in efforts to commence a larger conversation required to redress these gaps. The research questions that guided this paper are as follows:

RQ 1. What existing literature is there on the humanitarian-development nexus and the humanitarian-development-peace nexus and what does it tell us about current academic and partitioner thought and practice?

RQ 2. What is missing from this discussion in the literature and what unintended, negative consequences could it pose?

Context: historicizing the double and triple nexus

The linking of humanitarian and development activity is not a new concept. Some of the earliest efforts to link the two can be seen in nineteenth-century British colonial policies for famines in India (Lindahl Citation1996). The concept of the double nexus’s more contemporary origins, however, are rooted in the aftermath of World War II, with the linking of relief and reconstruction efforts in development policy (Lindahl Citation1996). By the 1960s, the concept of the double nexus was beginning to become a focal issue for certain UN institutions as well as the subject of numerous international conferences, briefings, and meetings, beginning the first generation of linking humanitarian and development assistance; a predecessor to what would ultimately become the double nexus (Askwith Citation1994; Lindahl Citation1996; Shusterman Citation2021). From this point forward, we identify four generations of the development of the double and subsequently triple nexus, defined largely around the evolving priorities and areas of focus, as outlined in , and as described in the following sub-sections. Notably, these generations do not neatly divide over time, but rather occurred sometimes in parallel, and as distinct discourses. Nonetheless, amidst these discourses, we outline four key generations to capture the developments of the nexus over time.

Table 1. Key questions for each generation of the nexus.

First generation: origins of the double nexus

The United Nations System as a whole – with the major exceptions of UNICEF [United Nations Children’s Fund] and to some extent WHO [World Health Organization] and FAO/WFP [Food and Agriculture Organization/World Food Programme] – is not equipped to provide emergency relief. […] The United Nations System is not geared for action of this kind, nor is it realistic, given its structure, it could become so (Thant Citation1971, 19).

UNICEF was one of the first organizations to begin to bridge the divide. During the week of 1–7 April 1964, UNICEF participated in the ‘International Conference on Planning for Children in Developing Countries’ in Bellagio, Italy, where the organization began its transformation from a humanitarian to development agency (Shusterman Citation2021). This was a pivotal moment in the development of what would become the double nexus (Shusterman Citation2021). During UNICEF’s transition not only did the organization win the 1965 Nobel Peace Prize but it also made clear that it’s humanitarian aims could only be achieved through the combination of both short term, individualized relief and long term, national economic and social development projects (Shusterman Citation2021). UNICEF’s first edition of The State of the World’s Children (1981) served to demonstrate this unique position, stating that while the organization would provide a humanitarian response to ‘loud emergencies’ when required, it’s larger commitment was to development projects combating the ‘silent emergencies’ such as poverty, hunger, and lack of access to basic human needs; a narrative that permeated UNICEF through the 1980s and 1990s (Grant Citation1981; Shusterman Citation2021). By the 1990s, UNICEF saw its role in emergency humanitarian action as ‘a limited but significant part of its overall mandate’ (Shusterman Citation2021; UNICEF Citation1996a, 1). This conversation revolving around the transition from humanitarian to development assistance amongst other UN organizations, however, only began to gain prominence in the early 1990s (Askwith Citation1994; Shusterman Citation2021).

On 19 December 1991, the UN General Assembly adopted resolution 46/182 which stated that all emergency assistance should attempt to facilitate long-term development and recovery (Askwith Citation1994). Resolution 46/182 was additionally responsible for the creation of the United Nations Department of Humanitarian Affairs (DHA) (Askwith Citation1994; Lindahl Citation1996). Established in 1992, the DHA’s primary responsibility was the linking of humanitarian and development efforts (Askwith Citation1994; Lindahl Citation1996). However, between 1992 and 1997 the DHA meticulously drew a sharp distinction between what constituted humanitarian and development assistance by systematically rejecting emergency appeals from projects they deemed developmental (Shusterman Citation2021). As a result, the distinction between humanitarian and development assistance widened (Shusterman Citation2021) and continued to be formalized within institutional structures of funding.

An early attempt to bridge the humanitarian-development divide was the concept of the ‘continuum’; an earlier version of what would ultimately transform into the double nexus (Gómez and Kawaguchi Citation2018; Shusterman Citation2021). First introduced by UNDP and the DHA in 1991, the ‘continuum’ was a mechanism for disaster preparedness and prevention involving the immediate operationalization of humanitarian relief followed by development and reconstruction efforts (Gómez and Kawaguchi Citation2018; Shusterman Citation2021). By 1996, the EU had developed the ‘Linking Relief, Rehabilitation, and Development’ (LRRD) framework, the main element of which centered around the concept of non-linear programming, drawing on lessons from the hunger crises of the mid-1980s that highlighted the chaotic cycle of populations moving from relief to development or vice versa (Buchanan-Smith and Fabbri Citation2005; Commission of the European Communities Citation1996; Humanitarian Coalition Citation2021; Macrae et al. Citation1997; Mosel and Levine Citation2014; Otto and Weingärtner Citation2013). The EU’s justification for the proposed linking of relief, rehabilitation, and development in their 1996 report is as follows:

disasters are costly in both human life and resources; they disrupt economic and social development; they require long periods of rehabilitation; they lead to separate bureaucratic structures and procedures which duplicate development institutions … Better ‘development’ can reduce the need for emergency relief; better ‘relief’ can contribute to development; and better ‘rehabilitation’ can ease the transition between the two. (Commission of the European Communities Citation1996, iii)

Second generation: the first discussions of conflict and peace

The second generation of linking humanitarian and developmental assistance emerged shortly after the end of the Cold War (Lindahl Citation1996; Shusterman Citation2021). Closely associated with security, foreign policy, and military intervention, it focused mainly on conflict-related disasters, which began to occur more frequently across Eastern Europe (Lindahl Citation1996; Shusterman Citation2021). These new conflicts proved to be extremely malevolent, difficult to subdue, and impossible to anticipate (Lindahl Citation1996). As a result, the concept of ‘permanent emergencies’ emerged (Lindahl Citation1996). In this realm of conflict and crisis-related discourses, one notable example is the Brookings Process of 1999, which discussed the ‘continuum’s’ relevance in post-conflict zones; a very early conceptualization of the triple nexus (Sadako, Citation2013; Shusterman Citation2021). The Brookings Process was the product of Sadako Ogata’s (head of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), 1990-2001) and James Wolfensohn’s (the ninth president of the World Bank, 1995-2005) leadership, focusing on improving organizational approaches to complex crises which require both fluid responses and funding (Ogata and Wolfenshon 1999 cited in Crisp Citation2001; Shusterman Citation2021). The article by Ogata and Wolfenshon (1999 cited in Crisp Citation2001) concluded by stating:

The challenge is to develop a more comprehensive approach that would address the specific needs of people in war-torn societies, thereby helping to reduce the recurrence of violence and displacement … We believe that the starting point for a more integrated humanitarian-development response (with an international political-military dimension when necessary) is a more coherent, co-operative planning process that utilizes organizations’ particular strength in particular situations. This, in turn, could drive, and be driven by, more coherent funding arrangements. (Ogata and Wolfensohn 1999 cited in Crisp Citation2001, 15)

Third generation: resilience & the soon to be ‘Double nexus’ discourse

The third generation emerged during the 2000s and was heavily tied to the concepts of ‘resilience’ – for both those in, and vulnerable to, crises – and ‘localization’ – specifically the collaboration between humanitarian and development workers in localized settings (Mosel and Levine Citation2014; Shusterman Citation2021). Unlike the second generation, which emerged largely from emergency and crisis context, resilience and localization were now prominent discussions in the development discourse. On the former, for example, resilience was widely adopted in developmental contexts impacted by a changing climate. The need to strengthen resilience via enhancing adaptive capacity required new ways of working, including approaches that analyzed a spectrum of responses and potential future shocks. In the development sphere, this often resulted in shifts toward multi-sectoral programming, which included aspects traditionally considered humanitarian or developmental, within broader package of interventions. This focus on resilience as a concept was thought to open opportunities for development assistance to be deployed more frequently in protracted crises and to reform humanitarian assistance to be longer-term and more collaborative with development assistance (Mosel and Levine Citation2014). On the latter, the questions of power emerging out of the calls for localization can be seen in the 2005 Paris Declaration for Aid Effectiveness and the 2008 Accra Agenda for Action. These conversations often did not merge into the discourse of what would soon be formally named double nexus but provided the seeds for critiques about why both humanitarian and development programming experienced failures and/or were replicating problematic colonial relationships.

Fourth generation: the double & triple nexus

The fourth generation of the nexus, the one which we are currently in, began with the formalization of the double and triple nexus (Barakat and Milton Citation2020; Shusterman Citation2021).

The ‘double nexus’ was proposed as part of the Grand Bargain agreement and launched at the 2016 World Humanitarian Summit (Barakat and Milton Citation2020). The goal of the Grand Bargain was to ensure enhanced coordination, transparency, and comparative advantage between actors (Barakat and Milton Citation2020; IASC Citation2020). However, while there has been convergence on the need for the double nexus by intergovernmental, governmental, and non-governmental agencies, the specific definition remains debated. UNICEF argues that there is no common definition of the double nexus, instead proposing that there are rather four key elements of the nexus; (1) joint risk, vulnerability, and needs analysis through strengthening coordination, (2) cooperative programming, (3) planning cycle alignment, and (4) partnership between actors (UNICEF Citation2020).

The ‘triple nexus’, on the other hand, was proposed one year later in 2017 by Secretary General Antonio Guterres, aiming to emphasize conflict prevention amongst UN agencies following a recognition that in areas that are at risk and experiencing crises, violence, poverty, and environmental challenges are becoming more prevalent (Barakat and Milton Citation2020; OECD Citation2022). The Inter-Agency Standing Committee (IASC) believes that the triple nexus can be interpreted in one of five ways; (1), an approach which reflects the reality of interaction amongst nexus actors (2), a policy imperative which urges the UN to reformulate their policies (3), an operational imperative for actors in the field requiring them to collaborate (4), a conundrum for the international community to solve and (5), a whole-of-system approach requiring coherence amongst actors (IASC Citation2016; ICVA Citation2017).

And, while these conceptual differences matter, we draw attention not to what should or should not be included and/or how the components of the nexus are defined, but rather we focus on the potential for the nexus to have unintended, negative consequences. We now turn to three key nuances, which we view as critical, lest the rush for nexus approaches replicate failures and/or result in new ones.

Methodology

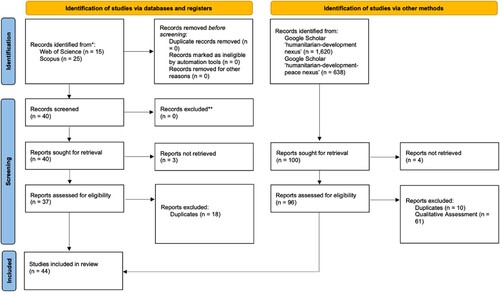

Historicizing the nexus as well as assessing the available literature for existing evidence and criticisms required a thorough research approach. To do so, we draw on methodologies utilized for systematic literature reviews. However, unlike many systematic literature reviews, we did not only seek academic literature, but also publications from outside of it, such as government, non-governmental, and intergovernmental reports. To achieve this, the search criteria outlined in were applied to three databases: Web of Science, Scopus, and Google Scholar. First, we searched Web of Science, an academic database that only indexes materials deemed to meet a certain degree of rigor, typically peer-reviewed academic articles and books. Second, the search criteria were applied to Scopus, another academic database which includes different indexed material (e.g. Aghaei et al. Citation2013; Martín-Martín et al. Citation2018). We then applied the same search process with Google Scholar as well as possible due to the search constraints of the platform, which lacked some search functionality.

Table 2. Literature search inclusion and exclusion criteria.

We included Google Scholar, which is not an academic database nor is it curated, because it indexes a broader range of materials, such as reports and briefs which would not have been included in the other two databases. We felt this is particularly important for the topic of study, as the nexus has been widely discussed within intergovernmental and non-governmental reports that may not meet the qualifications necessary for Web of Science or Scopus, and their exclusion would present a serious limitation. Google Scholar does however present challenges for systematic literature reviews as it conducts a full-text search (as opposed to keywords, title, and abstract) which results in far too many potential results to review. As a result, we reviewed Google Scholar results by page (Google Scholar suggests that its results are listed by relevance), reviewing the first five pages (or most relevant 50 results) for new, relevant publications (‘new’ in this instance means publications not already identified by Web of Science or Scopus). The searches were conducted in April 2021 and PDF copies of all files were saved to create a database for analysis.

The results varied by search platform, which reinforces the importance of utilizing multiple databases when conducting a literature review or systematic search (see ).

The analysis of this set of literature was conducted in three stages: (1) quantitative analysis using NVivo’s full-text, key word search; (2) contextual, qualitative analysis of the full-text, key word search result; and (3) expert assessment of the literature.

In stage 1, the search terms utilized in the NVivo analysis – localiz*, localis*, decoloniz*, decolonis*, Accra Agenda, Paris Declaration, solidarity, Grand Bargain, local leadership, inequalit*, do no harm, unintended, negative effects, impartiality, neutrality, exit strategy, specialization, crisis modifier, legacy, sustainability strategy, sustainable strategy – were broad and required multiple combinations of searches.Footnote1 Boolean modifiers such as the asterix were utilized for just this purpose, ensuring that all possible endings (e.g. localization, localized, localizing, etc.) were included. Regional spelling variations (e.g. ‘localiz*’ versus ‘localiz*’) were also considered to ensure no possible results were missed. From a methodological perspective, these are critical processes to ensure accurate results, which we outline in some detail here to emphasize for other researchers and future research.

Where matches were found, we conducted a qualitative analysis of every single match; stage 2. All results were tracked, including every instance of the use of the term within context. This step sought out specific discussions and critiques within the nexus context.

Finally, based on our expert assessment of the literature, we identified gaps, based upon which we delved into more specific qualitative studies to better situate those gaps or ‘nuances’ allowing us to make the unique contributions of this paper. And, while our expert assessment identified several existing challenges discussed at length within the nexus work – namely, programmatic, organizational, and financial, which we touch upon briefly at the beginning of the results and discussion section – our identification of the three specific nuances we present – (1) control and decision-making, (2) potential to cause harm, and (3) impositions that create inefficiencies – were those not sufficiently discussed within the existing literature. The focus, therefore, based on the literature and our qualitative and quantitative analysis, identified these nuances and being under analyzed and hence our highlighting of them in this paper.

Methodological & study limitations

There are several limitations of this study that should be considered, which may have impacted both the literature identified as well as the critiques that we identified. One limitation is linguistic; we only searched for materials in English, meaning conversations on this topic in all other languages were missed. In addition to this, the content tends to be biased toward academic and researcher perspectives, due to the nature of the publications included. What is missed is other realms of sourcing evidence, such as discussions of this issue on social media and/or in journalistic reporting. For the nuances, we opted to focus on the recent literature (2010 forward), which aligns with the emergence of the ‘fourth generation’ of the nexus. This resulted in the exclusion of older materials. However, as this article focuses on the current (and future) discourse, the most recent material is best suited for our research objective. It is possible that relevant literature has been missed in our search due to the databases selected or the search terms employed. Furthermore, selection and interpretive bias likely impacted the articles chosen during the qualitative assessment of the title, keywords, and abstract which eliminated articles that were unrelated to the key terms. Future research can address these gaps, complementing the findings and arguments of this research.

Results & discussion: nuancing the double and triple nexus

We have identified three areas of the double and triple nexus that require nuance: (1) control and decision-making, (2) potential to cause harm, and (3) impositions that create inefficiencies. However, we also recognize that existing literature has already identified three other challenges for the double and triple nexus, namely the need for (a) programming, (b) financing, and (c) organizational reform due to the demand for concurrent humanitarian, development, and peace programming by the double and triple nexus (Development Initiatives Citation2021). All of which, drawing on summative work by Development Initiatives (Citation2021) at the country level, can be addressed by (a) exploiting present synergies amidst double and triple nexus programming by developing a common approach, improving context analysis capabilities and, consequently, establishing review systems to adapt new implementation strategies based on this context analysis. (b), fostering a common understanding surrounding appropriate support for crisis-affected places and peoples, improving tracking and targeting of official development assistance, greater coherence between crisis and development financing initiatives, and increased funding flexibility as well as making double and triple nexus actors more aware of the financial tools available to them (Development Initiatives Citation2021). And (c), accelerating crisis adaptation by decentralizing management, improving context-driven decision-making, and reducing barriers between disciplines to expand all actors’ knowledge of one another’s initiatives and overall skills in order to improve communication and comprehension (Development Initiatives Citation2021). However, while these three challenges are substantial, in many ways these are not new. As a result, we now turn towards the three unique challenges that we identified that are specific to the double and triple nexus or may emerge as it is integrated into donor frameworks and organizational mandates.

The double and triple nexus as a new form of donor control

The double and triple nexus are promoted as a new ‘best practice’, and for many justifiable reasons. However, the double or triple nexus approach also has the potential to centralize decision-making away from local actors; one of many possible control risks. For example, if the double or triple nexus becomes a donor design and implementation requirement, as a measure of success that actors are required to report against, as coordination requirements, or as an assumed means of cost savings. These forms of power and control continue to be embedded within technocratic and administrative mechanisms (e.g. Airey Citation2022; Cochrane and Thornton Citation2016), which the double and triple nexus has the potential of replicating. If the double or triple nexus were institutionalized in these forms, it would run counter to the Grand Bargain and commitments to localization. In our review of the literature, we find – troublingly – that very few publications about the nexus also discuss localization. This is also the case for other aspects that would highlight a central concern about power, such as engaging with calls for the decolonization of aid, commitments made to the Paris Declaration on Aid Effectiveness, the Accra Agenda for Action, and the Grand Bargain, or assertions of doing aid differently by focusing upon solidarity and local leadership. There are a few key scholars that have made these linkages, with whom we agree, and advance a specific nuance for nexus related to risks of power and control.

Burkina Faso provides one example wherein good aspirations can encounter barriers via newfound rigidity, creating systems not designed in ways that are flexible, particularly in hybrid contexts where both humanitarian and development activities may operate in parallel (e.g. see United Nations Citation2018). These lessons have also emerged in Ethiopia (United Nations Citationn.d.a), Mauritania (United Nations Citationn.d.b) and Uganda (Lie Citation2020). One way in which we could see the concerns about power and control within the double or triple nexus discourse is if there were intersections with the demands for greater localization. When we searched for localization (in its varied forms), 12 of 45 (27%) articles used the terms. While this appears positive, the qualitative assessment of the uses of these terms identified that most did not engage the subject substantively. Some publications did not use the terms in the text at all, only appearing in the reference list (e.g. Hovelmann Citation2020a, Citation2020b), while others reference localization in peripheral ways, often mentioned only once in passing (e.g. Al-Mahaidi Citation2020; Dūdaitė Citation2018; Erdilmen Citation2019; Gallagher, Vernaelde, and Casey Citation2020; Kocks et al. Citation2018; Shusterman Citation2021; Waisová and Cabada Citation2019a, Citation2019b).

Of the publications that engaged with localization within the context of the double and triple nexus, Lafrenière, Sweetman, and Thylin (Citation2019) and Schaff et al. (Citation2020) refer to localization as a means to better engage and support women-led organization. Kuipers et al. (Citation2019) substantively integrate the triple nexus and localization discussions, clearly identifying the power and control issues involved and explicitly argues for localization. Anholt (Citation2020) also explicitly raises localization as a means to strengthen double nexus approaches, specifically in the context of building resilience as well as in ownership and leadership. Yet, Anholt (Citation2020) also cautions against simplistic binaries of localization itself, which can foster ‘blind spots’ of inclusion and exclusion. Barakat and Milton (Citation2020) focus their entire article on localization within the humanitarian, development, and peace aspect of conflict response. The authors identify four key issues in relation to localization (defining local, valuing local capacity, maintaining political will, multi-scalar responses), and these conceptualizations link with the nuance outlined in this article, in that when the triple nexus considers localization (which is infrequent) these conceptualizations have direct consequences for power and control. In the context of minimal or tokenistic forms of localization, Barakat and Milton (Citation2020) argue that national organizations can be infantilized with colonial approaches and attitudes; we argue that the same can occur under the guise of implementing the double or triple nexus. The ability for local actors to design projects based on local priorities may be negated as donor priorities regarding double or triple nexus design take precedence. Similarly, the expectation of double or triple nexus implementation has the potential to centralize decision-making, ensuring donor expectations are met.

Localization is not the only pathway to critical considerations of power and control. There have been a range of commitments where this can be focal, such as the Paris Declaration on Aid Effectiveness (2005), the Accra Agenda for Action (2008), and the Grand Bargain. Only three publications make mention of the Paris Declaration (Callies, Giorgis-Audrain, and Krizan Citation2021; Howe Citation2019; Kocks et al. Citation2018), all of which in passing as general commitments. No single publication mentioned the Accra Agenda. The Grand Bargain was more frequently referred to, albeit largely in passing as a commitment (e.g. Callies, Giorgis-Audrain, and Krizan Citation2021; Cimino Citation2020; Guinote Citation2019; Hovelmann Citation2020c; Howe Citation2019; Kocks et al. Citation2018; Shusterman Citation2021; Spiegel Citation2017; Weishaupt Citation2020), with only a few noting the failure of actors to meet this commitment (e.g. Kuipers et al. Citation2019) or their limitations (e.g. Dūdaitė Citation2018; Lafrenière, Sweetman, and Thylin Citation2019; Schaaf et al. 2020). In all these instances, the commitments are not engaged within ways that would force us to rethink how the double or triple nexus has the potential to counter these objectives. Alternatively, publications could have framed their engagement in positive terms, such as in reforming action towards solidarity-based activity (as per Tandon Citation2008). References to solidarity, however, were largely made in passing (e.g. Erdilmen Citation2019; Klein-Kelly Citation2018; Türk Citation2019), without substantive engagement with how this can or should alter the way the double or triple nexus operates.

As Barakat and Milton (Citation2020) explain, localization is fundamentally political; it was only these authors who made the connection of this concern to decolonizing humanitarian and development activity and they are the only authors to emphasize local leadership. The double and triple nexus is not a technical process, it is a political one that needs to be engaged politically lest it act as a way that counters commitments to localization and reinforces colonial power imbalances. We need to integrate the Paris Declaration on Aid Effectiveness, the Accra Agenda, and the Grand Bargain into all our discussions surrounding the double and triple nexus. It is unacceptable that most publications about the double or triple nexus are not substantively engaging these discussions surrounding control, nor the implications of these commitments. This reiterates the importance of our concern that unless we nuance the double and triple nexus it has a high potential to silently become a new mechanism of control.

Implementing the double or triple nexus can cause harm

When implementing the double or triple nexus, difficult decisions must be made: When to transition from humanitarian to development programming? If resources are concentrated in a more developmental way (e.g. geographically or sectorally) for whom or where might resources be reduced? These decisions can cause direct or unintended harm, which is why most humanitarian and development actors advocate for a ‘do no harm’ foundation to guide their work. However, not all organizations embrace this in the same way, some do this as a flexible approach while others refer to ‘do no harm’ as a specific framework and/or set of principles (Lie Citation2017). Other actors do not refer to ‘do no harm’, instead referring to the humanitarian charter (Charancle, Bonis, and Lucchi Citation2018). This is important because implementing the double or triple nexus assumes a common understanding of implementation approaches; however, the literature on the double and triple nexus highlights that divergence of conceptualizations and definitions have the potential to result in different ways that those difficult questions are answered (Dūdaitė Citation2018; Guinote Citation2019; Horne and Boland Citation2019; Klein-Kelly Citation2018; Weishaupt Citation2020). While there may be actors that have cohesion across the humanitarian and development spaces, this should not be assumed. For example, humanitarian actors may view ‘do no harm’ as minimizing newly introduced risk (as in the Humanitarian Charter), while development actors may consider negative impacts in society (culture, economy, environment; Charancle, Bonis, and Lucchi Citation2018; Weishaupt Citation2020). These varied conceptualizations and definitions are not limited to ‘do no harm’, but also ‘localization’, as pointed out by Barakat and Milton (Citation2020), who identify different conceptualizations used between humanitarian actors when compared to development and peacebuilding ones.

In making this nuance, we are not suggesting that the nexus approach itself causes harm, but rather divergent conceptualizations of appropriate decision-making can transpose what is acceptable risk in one context to another where it is not. Similarly, we are not suggesting that harm is an outcome in a deterministic way, actors involved could proactively deepen their contextual analysis, align their risk assessments, and coordinate on approaches. We highlight this as an area for additional attention because of the limited engagement it has had to-date in the literature. Secondly, we highlight this nuance because some implementations of the nexus have caused harm and this is not merely an academic critique. In one project in Ethiopia, a NGO attempted to shift from humanitarian modalities of working to developmental ones. In practice, this meant concentrating the geographic focus to offer multi-sectoral activities within a more focused set of communities. From a development actor perspective, this is a shift toward ‘best practices.’ However, in this context, the vulnerability remained high and pervasive. This was also an area of ethnic diversity where these decisions crossed ethnic and linguistic lines. When the development actor opted to offer multi-sectoral interventions in communities within one geographic area, another ethnic group – given their emergency needs at the time – felt this was an act of illegitimate favoritism. Conflict ensued, and unfortunately, this choice resulted in the loss of life in both communities. We leave out the specifics of this case because the point is not to blame a specific actor, but highlight how challenging implementing the nexus can be, and the risks involved. The answers to these difficult decisions can, and already have, been the cause of conflict. Yet, beyond statements affirming the importance of ‘do no harm’, the literature on the nexus does not engage with the practicalities of implementation and the potential for causing harm.

In the emerging research and discourse on the double and triple nexus, the consequences of differences in decision-making approaches (and the guiding conceptualizations of that) between humanitarian and development actors are insufficiently considered. In the publications on the double and triple nexus, many recognize the risks related to operating in areas of inequality, including as a driver of conflict (Décobert Citation2019; Erdilmen Citation2019; Howe Citation2019; Oller Citation2020) as well as the potential for negative, unintended consequences in general (e.g. Décobert Citation2019; Klein-Kelly Citation2018). Publications also raise concerns about how some humanitarian principles could work against the aims of the double or triple nexus, such as impartiality and neutrality (e.g. Guinote Citation2019; Hovelmann Citation2020a, Citation2020c; Howe Citation2019; Klein-Kelly Citation2018; Kocks et al. Citation2018; Kuipers et al. Citation2019; Nguya and Siddiqui Citation2020). We do not find the substantial engagement of how implementing the double or triple nexus can cause conflict, nor explicit recognition that differences in decision-making across the humanitarian and development spheres can be the root cause of this.

Imposing the double or triple nexus on NGOs can foster inefficiency

Humanitarian and development actors tend to have specializations; these may be situational (e.g. conflict) or sectoral (e.g. health or agricultural development). The double and triple nexus assumes that organizations will either have the expertise outside of their specialization, will rapidly obtain it, or will coordinate with other actors appropriately. This assumption is critical to explore because if actors are pushed into areas outside of their expertise, they may replicate errors of the past due to a lack of experience (e.g. if development actors newly engage in conflict settings, or actors with high capacity in conflict resolution begin engaging in humanitarian or development activity delivery). Each of these sphere, and indeed the sector-specific specializations within each of these domains, requires specific technical knowledge and institutional capacity, The limited capacity required to implement double or triple nexus approaches have been noted as key issues (e.g. see United Nations Citation2018) and the identification of ‘key actors’ for implementing it as critical (e.g. United Nations Citationn.d.c), however, lacking from this conversation is the unique capacities, experiences, and priorities of different actors in the humanitarian, development, and peace spheres. One way actors have been creating flexibility to move across humanitarian and development activities in a more responsive way is to integrate crisis modifiers in the design. Somewhat unexpectedly, no publication mentioned this term. Relatedly, only one publication mentioned ‘exit strategy’ (Lie Citation2017) and none engaged ‘sustainability strategy’, ‘sustainable strategy’, or ‘legacy’ in this context (in our search for other adopted terminologies). In general, there seems to be a lack of attention to the details of implementation without exploring the difficulties of how the implementation of the double or triple nexus will occur in practice.

One proposed solution is not that individual actors/organizations fill these gaps, but that they coordinate with others to do so. Indeed, a key component in operationalizing the double or triple nexus is building effective partnerships (Development Initiatives Citation2021). However, the ‘different approaches to partnership that humanitarian, development, and peace actors adopt can support but also potentially limit their ability to work collaboratively at the nexus’ (Development Initiatives Citation2021, 6). Given the ongoing challenges of coordination within humanitarian and development sectors on their own (BouChabke and Haddad Citation2021; Cochrane Citation2020), expecting collaboration across sectors seems unrealistic. Effective partnership also extends beyond development actors. Local CSOs’ and national governments’ engagement is, and has always been, central to the practice of successful development (Development Initiatives Citation2021). Thus, in order to operationalize the nexus, partnership at the country level is argued to be ‘dynamic, flexible, risk informed and context specific to enable not only longer-term partnership but also short-term mechanisms for flexibility and responsiveness to immediate needs; partner with local governments as a critical player, particularly in conflict-affected regions and where the central government may be weak, supporting decentralization where it will enable better inclusion and long-term peace; [and] invest in partnerships beyond the government – local civil society and the private sector are vital and too often lack investment in protracted crises. Pooled funds and NGO consortia are a useful way to do this at scale’ (Development Initiatives Citation2021, vi). For anyone assuming that the double or triple nexus will be more cost effective, this nuance should make clear that it will not. Coordination of actors across scales and sectors is not simple, swift, nor low cost.

Conclusion

In conclusion, over the past six decades there has been a substantial improvement of, and excitement for, the concept of a double or triple nexus approach. This, however, does not mean each generation and their subsequent improvements have come without their own unique challenges and flaws. In this fourth generation especially there has been great enthusiasm for the implementation of a double or triple nexus approach given the rise of complex crises around the globe, but also calls for caution regarding the double or triple nexus’ programmatic, financing, and organizational challenges. These challenges, while substantial, are not new, plaguing the implementation of a double or triple nexus approach along with siloed initiatives. This article, however, sought to go beyond this by analyzing recent (between January 2010 to May 2021) scholarly, government, non-governmental, and intergovernmental literature across three different search platforms (45 unique articles in total) to identify three specific challenges: (1) control and decision-making, (2) potential to cause harm, (3) impositions that create inefficiencies – related directly to the implementation of a double or triple nexus approach. We found that (1) while there have been international calls and agreements to decentralize and decolonize decision-making such as the Grand Bargain, the Paris Declaration on Aid Effectiveness, and the Accra Agenda, there has been little discussion of this within the double and triple nexus literature. (2) despite the double and triple nexus’s inherent need for coordination, core concepts/principles such as ‘do no harm’ and ‘localization’ are not cohesively conceptualized across different double and triple nexus actors, a reality which the literature on the double and triple nexus does not engage with beyond highlighting said differences. Despite the double and triple nexus’s ability to cause harm because of this, there is little engagement of the double or triple nexus’s ability to cause conflict as well within the literature. (3) despite the double and triple nexus’s assumption that organizations – which have specific focuses and specializations – will require expertise outside of their focus, their ability to rapidly obtain or gain expertise, there is little discussion in the literature of the unique capacities, experiences, and priorities of different actors in the humanitarian, development, and peace spheres, nor of methods to improve organizational flexibility and response such as ‘crisis modifiers’, ‘exit strategies’, ‘sustainability strategy’, ‘sustainable strategy’, or ‘legacy’. Therefore, we argue that while we support the calls for the implementation of a double or triple nexus approach, there is a lack of consideration for the unintended consequences of the double and triple nexus which have the potential to replicate failures of the past in new forms.

Acknowledgements

Open Access funding was provided by the Qatar National Library.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 The results are presented within the nuances section, with each searched term introduced in the sub-section relevant to it.

References

- Aghaei, Chadegani Arezoo, Hadi Salehi, Melor Yunus, Hadi Farhadi, Masood Fooladi, Maryan Farhadi, and Nader Ale Ebrahim. 2013. “A Comparison Between Two Main Academic Literature Collections: Web of Science and Scopus Databases.” Asian Social Science 9 (5): 18–26. doi:10.5539/ass.v9n5p18

- Airey, Siobhán. 2022. “Rationality, Regularity and Rule – Juridical Governance of/by Official Development Assistance.” Canadian Journal of Development Studies/Revue Canadienne D’études du Développement 43 (1): 116–136. doi:10.1080/02255189.2022.2026306

- Al-Mahaidi, Ala. 2020. “Financing Opportunities for Durable Solutions to Internal Displacement: Building on Current Thinking and Practice.” Refugee Survey Quarterly 39: 481–493. doi: 10.1093/rsq/hdaa019

- Anholt, Rosanne. 2020. “Resilience in Practice: Responding to the Refugee Crisis in Turkey, Jordan, and Lebanon.” Politics and Government 8 (4): 294–305. doi:10.17645/pag.v8i4.3090

- Askwith, Michael. 1994. “The Roles of DHA and UNDP in Linking Relief and Development.” IDS Bulletin 25 (4): 101–104. doi:10.1111/j.1759-5436.1994.mp25004014.x

- Barakat, Sultan, and Sansom Milton. 2020. “Localization Across the Humanitarian-Development Nexus.” Journal of Peacebuilding and Development 15 (2): 147–168. doi:10.1177/1542316620922805

- BouChabke, Soha, and Gloria Haddad. 2021. “Ineffectiveness, Poor Coordination, and Corruption in Humanitarian Aid: The Syrian Refugee Crisis in Lebanon.” VOLUNTAS 32 (4): 894–909. doi:10.1007/s11266-021-00366-2

- Buchanan-Smith, Margie, and Paola Fabbri. 2005. “Links between Relief, Rehabilitation and Development in the Tsunami Response: A Review of the Debate.” Tsunami Evaluation Coalition. https://www.alnap.org/help-library/links-between-relief-rehabilitation-and-development-in-the-tsunami-response-a-review-of.

- Callies, Lydia, Alexandra Giorgis-Audrain, and Laura Krizan. 2021. “The Importance of Transparency, Accountability and Intersectionality in the Implementation of International Assistance.” Pandemic 2021 Global Trends Report An Anthology of Briefing Notes by Graduate Fellows at the Balsillie School of International Affairs. https://www.balsillieschool.ca/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/Graduate-Fellows-Anthology-2021-revised.pdf#page=59.

- Campanaro, Giulia, Davidson Hepburn, Malgorzata Kowalska, and Ann Wang. 2002. “Developmental Relief: The European Perspective.” https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/2AB751A15ED18DE7C1256CB600572888-ia-dev-apr02.pdf.

- Charancle, Jean, Martial Bonis, and Elena Lucchi. 2018. Incorporating the Principle of “Do No Harm”: How to Take Action Without Causing Harm. Lyon: F3E.

- Cimino, Diego. 2020. “The Humanitarian-Development-Peace Nexus: Solving Rubik’s Cube in Policy and Practice.” Journal of International Cooperation and Development 3 (1): 129–143. doi:10.36941/jicd-2020-0011

- Cochrane, Logan. 2020. “Synthesis of Evaluations in South Sudan: Lessons Learned for Engagement in Fragile and Conflict-Affected States.” Journal of Humanitarian Affairs 2: 21–34. doi:10.7227/JHA.031

- Cochrane, Logan, and Alec Thornton. 2016. “Charity Rankings: Delivering Development or De-Humanizing Aid?” Journal of International Development 28: 57–73. doi:10.1002/jid.3201

- Commission of the European Communities. 1996. “Communication from the Commission to the Council and the European Parliament on Linking Relief, Rehabilitation and Development.” https://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=COM:1996:0153:FIN:EN:PDF.

- Crisp, Jeffrey. 2001. “Mind the Gap! UNHCR, Humanitarian Assistance, and the Development Process.” The International Migration Review 35.1 (2001): 168–191. doi:10.1111/j.1747-7379.2001.tb00010.x

- Dafinova, Maya. 2018. “Keeping the Inter-Agency Peace? A Comparative Study of Swedish, German, and British Whole-of-Government Approaches in Afghanistan.” PhD diss., Carleton University.

- Davidson, Angus Alexander, Michael Denis Young, John Espie Leake, and Patrick O’Connor. 2022. “Aid and Forgetting the Enemy: A Systematic Review of the Unintended Consequences of International Development in Fragile and Conflict-Affected Situations.” Evaluation and Program Planning 92 (2022): 1–13. doi:10.1016/j.evalprogplan.2022.102099.

- Desrosiers, Marie-Eve, and Philippe Lagassé. 2009. “Canada and the Bureaucratic Politics of State Fragility.” Diplomacy and Statecraft 20 (4): 659–678. doi:10.1080/09592290903455774

- Development Initiatives. 2021. Development Actors at the Nexus: Lessons from Crises in Bangladesh, Cameroon and Somalia. Rome: FAO, DI and NRC.

- Décobert, Anne. 2019. “The Struggle Isn’t Over: Shifting Aid Paradigms and Redefining ‘Development’ in Eastern Myanmar.” World Development 127 (2020): 104768–104780. doi:10.1016/j.worlddev.2019.104768

- Dūdaitė, Giedre. 2018. “Humanitarian-Development Divide: Too Wide to Bridge?” Masters Thesis, Aalborg Universitet.

- ECOSOC. 2017. “Enhancing the Humanitarian-Development-Peace Nexus. United Nations.” https://www.un.org/ecosoc/en/node/14973644.

- Erdilmen, Merve. 2019. “Durable Solutions and the Humanitarian-Development Nexus: A Literature Review.” LERRN, 1–28. doi:10.13140/RG.2.2.33867.34084.

- Gallagher, Meghan, Jamie Vernaelde, and Sara Casey. 2020. “Operational Reality: The Global Gag Rule Impacts Sexual and Reproductive Health in Humanitarian Settings.” Sexual and Reproductive Health Matters 28 (3): 68–70. doi:10.1080/26410397.2020.1824320

- Gómez, Oscar, and Chigumi Kawaguchi. 2018. “A Theory for the Continuum: Multiple Approaches to Humanitarian Crises Management.” In Crisis Management Beyond the Humanitarian-Development Nexus, edited by Atsushi Hanatani, Oscar Gómez, and Chigumi Kawaguchi, 15–25. New York: Routledge.

- Grant, James. 1981. The State of the World’s Children 1980–81. UNICEF. https://www.unicef.org/media/84521/file/SOWC-1980-81.pdf.

- Guinote, Filipa Schmitz. 2019. “QandA: The ICRC and the ‘Humanitarian-Development-Peace Nexus’ Discussion.” International Review of the Red Cross 101 (912): 1051–1066. doi:10.1017/S1816383120000284

- Hanatani, Atsushi, Oscar Gomez, and Chigumi Kawaguchi. 2018. Crisis Management Beyond the Humanitarian-Development Nexus. Boca Raton, FL: Routledge.

- Horne, Simon, and S. Boland. 2019. “Understanding Medical Civil-Military Relationships Within the Humanitarian-Development-Peace ‘Triple Nexus’: A Typology to Enable Effective Discourse.” BMJ Military Health. doi:10.1136/jramc-2019-001382. pre-print.

- Hovelmann, Sonja. 2020a. Triple Nexus to Go. Centre for Humanitarian Action.

- Hovelmann, Sonja. 2020b. Triple Nexus To Go: Humanitarian Topics Explained. Berlin: Centre for Humanitarian Action.

- Hovelmann, Sonja. 2020c. Triple Nexus in Pakistan: Catering to a Governmental Narrative or Enabling Independent Humanitarian Action? Berlin: Centre for Humanitarian Action.

- Howe, Paul. 2019. “The Triple Nexus: A Potential Approach to Supporting the Achievement of the Sustainable Development Goals?” World Development 124 (2019): 104629–104642. doi:10.1016/j.worlddev.2019.104629

- Humanitarian Coalition. 2021. “From Humanitarian to Development Aid.” https://www.humanitariancoalition.ca/from-humanitarian-to-development-aid.

- IASC. 2016. “Background paper on Humanitarian-Development-Peace Nexus.” https://interagencystandingcommittee.org/system/files/peace-hum-dev_nexus_150927_ver2.docx.

- IASC. 2020. “The Grand Bargain in Humanitarian Operations.” https://interagencystandingcommittee.org/system/files/2020-11/%5BEN%5D%20The%20Grand%20Bargain%20in%20humanitarian%20operations%20-%20September%202020.pdf.

- ICVA. 2017. “The ‘New Way of Working’ Examined: An ICVA Briefing Paper.” https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/NewWayOf%20Working_Explained.pdf.

- Klein-Kelly, Natalie. 2018. “More Humanitarian Accountability, Less Humanitarian Access? Alternative Ideas on Accountability for Protection Activities in Conflict Settings.” International Review of the Red Cross 100: 287–313. doi:10.1017/S1816383119000031

- Kocks, Alexander, Ruben Wedel, Hanne Roggemann, and Helge Roxin. 2018. “Building Bridges Between International Humanitarian and Development Responses to Forced Migration: A Review of Conceptual and Empirical Literature with a Case Study on the Response to the Syria Crisis.” EBA. https://www.ssoar.info/ssoar/handle/document/58565.

- Kuipers, Erin, Hedwig Christina, Isabelle Desportes, and Michaela Hordijk. 2019. “Of Locals and Insiders: A ‘Localized’ Humanitarian Response to the 2017 Mudslide in Mocoa, Colombia?” Disaster Prevention and Management 29 (3): 352–362. doi:10.1108/DPM-12-2018-0384

- Lafrenière, Julie, Caroline Sweetman, and Theresia Thylin. 2019. “Introduction: Gender, Humanitarian Action and Crisis Response.” Gender and Development 27 (2): 187–201. doi:10.1080/13552074.2019.1634332

- Lie, Jon Harald Sande. 2017. “From Humanitarian Action to Development Aid in Northern Uganda and the Formation of a Humanitarian-Development Nexus.” Development in Practice 27 (2): 196–207. doi:10.1080/09614524.2017.1275528

- Lie, Jon Harald Sande. 2020. “The Humanitarian-Development Nexus: Humanitarian Principles, Practice, and Pragmatics.” Journal of International Humanitarian Action 5 (1): 1–13. doi:10.1186/s41018-020-00069-1

- Lindahl, Claes. 1996. “Developmental Relief? An Issues Paper and an Annotated Bibliography on Linking Relief and Development.” Sida Studies in Evaluation 96/3. https://publikationer.sida.se/contentassets/f8eaf5f8fd0e45fa8c9714c5838a7f82/12864.pdf.

- Macrae, Joanna, Mark Bradbury, Susanne Jaspars, Douglas Johnson, and Mark Duffield. 1997. “Conflict, the Continuum and Chronic Emergencies: A Critical Analysis of the Scope for Linking Relief Rehabilitation and Development Planning in Sudan.” Disasters 21 (3): 223–243. doi:10.1111/1467-7717.00058

- Martín-Martín, Alberto, Enrique Orduna-Malea, Mike Thelwall, and Emilio Delgado López-Cózar. 2018. “Google Scholar, Web of Science, and Scopus: A Systematic Comparison of Citations in 252 Subject Categories.” Journal of Informetrics 12 (4): 1160–1177. doi:10.1016/j.joi.2018.09.002

- Merton, Robert King. 1936. “The Unanticipated Consequences of Purposive Social Action.” American Sociological Review 1 (6): 894–904. doi:10.2307/2084615

- Mosel, Irina, and Simon Levine. 2014. Remaking the Case for Linking Relief, Rehabilitation and Development: How LRRD Can Become a Practically Useful Concept for Assistance in Difficult Places. London: Humanitarian Policy Group.

- Nguya, Gloria, and Nadia Siddiqui. 2020. “Triple Nexus Implementation and Implications for Durable Solutions for International Displacement: One Paper and in Practice.” Refugee Survey Quarterly 39: 466–480. doi:10.1093/rsq/hdaa018.

- OCHA. n.d. “Humanitarian Development Nexus: The New Way of Working.” https://www.unocha.org/fr/themes/humanitarian-development-nexus.

- OECD. 2022. “The Humanitarian-Development-Peace Nexus Interim Progress Review.” https://www.oecd.org/fr/cad/the-humanitarian-development-peace-nexus-interim-progress-review-2f620ca5-en.htm#:~:text = In%20February%202019%2C%20the%20OECD,root%20causes%20of%20humanitarian%20challenges.

- Oller, Santiago Daroca. 2020. “Exploring the Pathways from Climate-Related Risks to Conflict and the Humanitarian-Development-Peace Nexus as an Integrated Response: Guatemala Case Study.” UNDP Issue no. 21/2020.

- Otto, Ralf, and Lioba Weingärtner. 2013. Linking Relief and Development: More Than Old Solutions for Old Problems? The Hague, Netherlands: Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

- Sadako, Ogata. 2013. “Internal Displacement and Development Agendas: A Roundtable Discussion with Sadako Ogata.” Brookings. https://www.brookings.edu/events/internal-displacement-and-development-agendas-a-roundtable-discussion-with-sadako-ogata/.

- Schaaf, Marta, Victoria Boydell, Mallory C. Sheff, Christina Kay, Fatemeh Torabi, and Rajat Khosla. 2020. “Accountability strategies for sexual and reproductive health and reproductive rights in humanitarian settings: a scoping review.” Conflict and Health 14: 1–18. doi:10.1186/s13031-020-0026402

- Shusterman, Jeremy. 2021. “Gap or Prehistoric Monster? A History of the Humanitarian–Development Nexus at UNICEF.” Disasters 45 (2): 355–377. doi:10.1111/disa.12427

- Spiegel, Paul. 2017. “The Humanitarian System Is Not Just Broke, But Broken: Recommendations for Future Humanitarian Action.” The Lancet, 1–8. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31278-3

- Tandon, Yashpal. 2008. Ending Aid Dependence. Oxford: Fahamu Books.

- Thant, U. 1971. “Assistance in Cases of Natural Disaster.” United Nations Digital Library. https://digitallibrary.un.org/record/787654?ln=en.

- Türk, Volker. 2019. “Preventing Displacement, Addressing Root Causes and the Promise of the Global Compact on Refugees.” Forced Migration Review 62 (2019): 64–67.

- UNDP. n.d. “Humanitarian and Development Nexus in Protracted Emergencies.” https://www.europe.undp.org/content/geneva/en/home/partnerships/humanitarian-and-development-nexus-in-protracted-emergencies.html.

- UNICEF. 1996a. “Children and Women in Emergencies: Strategic Priorities and Operational Concerns for UNICEF.” United Nations Digital Library. https://digitallibrary.un.org/record/229766?ln=en.

- UNICEF. 2020. “The Humanitarian-Development Nexus: The Future of Protection in the Elimination of Female Genital Mutilation.” https://www.unicef.org/media/87311/file/FGM-Humanitarian-Development-Nexus-2020.pdf.

- United Nations. 2018. “Burkina Faso.” https://www.un.org/jsc/content/burkina-faso.

- United Nations. n.d.a. “Ethiopia.” https://www.un.org/jsc/content/ethiopia.

- United Nations. n.d.b. “Mauritania.” https://www.un.org/jsc/content/mauritania.

- United Nations. n.d.c. “Somalia.” https://www.un.org/jsc/content/somalia.

- Waisová, Šárka, and Ladislav Cabada. 2019a. “Environmental Cooperation as a Tool for Local Development and Peace-Building in Conflict-Affected Areas.” In Contemporary Drivers of Local Development, edited by Péter Futó, 269–284. Maribor, Slovenia: Institute for Local Self-Government Maribor.

- Waisová, Šárka, and Ladislav Cabada. 2019b. “Local Development Projects and Security Strategy: The Security-Development Nexus in the Post-9/11 Period.” In Contemporary Drivers of Local Development, edited by Péter Futó, 285–304. Maribor, Slovenia: Institute for Local Self-Government Maribor.

- Weishaupt, Sebastian. 2020. The Humanitarian-Development-Peace Nexus: Towards Differentiated Configurations. Geneva: United Nations Research Institute for Social Development.