ABSTRACT

Due to structural inequalities, women’s well-being faces greater privations than that of men, with both direct and indirect effects on individual well-being. Measuring women’s poverty relative to men’s is not easy due to the statistical reliance on the household as the unit of data collection and analysis. This is not ideal, as resources are unequally distributed within households. This study constructs a multidimensional poverty index in which the unit of analysis and identification is the individual, allowing researchers to identify and compare the poverty of Mexican women and men. Time poverty, which denotes a scarcity of time for leisure and self-care, is included. The multidimensional poverty index is constructed using nationally representative official Mexican data from 2020. The Alkire and Foster (2011, Counting and Multidimensional Poverty Measurement, Journal of Public Economics 95 (7-8): 476–487. doi:10.1016/j.jpubeco.2010.11.006) methodology is used to estimate and compare the poverty of women and men in different age groups. The results show that the multidimensional poverty index is greater for women than for men, and that its significance and importance vary with age. While education contributes most to the adjusted headcount ratio, time deprivation is also important, especially for women.

1. Introduction

Women face inequalities in various intersecting forms and dimensions in the private and public spheres due to gender-discriminatory structures and processes (Chant Citation2006, 3). This has led to the recognition that poverty needs to be accounted for using the genderFootnote1 perspective. This means, firstly, that poverty affects women and men in different ways. Secondly, poverty acquires different features across women and men, who have different responsibilities, experiences, interests and needs. Thirdly, there are differences in the factors that influence the way they experience poverty. Thus analyzing poverty from a gender perspective requires finding new ways of measuring it that take its complexity and multidimensionality into account (CEPAL Citation2004).

The Capabilities framework is useful for analyzing gendered poverty because it centers on individuals’ quality of life, which is not achieved through income or consumption alone. This approach does not inquire into what resources women have, but considers their capability to function; i.e. what they are able to do or be, such as whether they are physically healthy, their physical integrity, their ability to play, etc. (Nussbaum Citation2000). The Capabilities approach, then, requires a multidimensional poverty measure that accounts for the various forms of deprivation that individuals experience (Haughton and Khandker Citation2009).

This paper rejects the notion that women’s well-being can be subsumed within that of the household or community, and acknowledges the importance of relationships and their interdependence (Chattier Citation2012). This implies that women’s well-being cannot be accounted for at the household level; yet most poverty measures, including multidimensional ones, use the household as the unit of analysis. Since household-level data is silent on the asymmetries between women and men in the distribution of benefits and burdens in the household, it is much more appropriate to calculate a poverty index that uses the individual as the unit of analysis rather than the household.

A key issue that quantitative research has largely neglected is the element of time. Poverty measurements should take into consideration the fact that women’s disproportionate productive and reproductive burden can lead to relative time poverty (Bradshaw, Chant, and Linneker Citation2017, 1670). They have little or no time for the rest and recreation that are fundamental to well-being (Bardasi and Wodon Citation2006; Bradshaw, Chant, and Linneker Citation2017)

This article sets out a multidimensional poverty index (MPI) incorporating a fundamental aspect of well-being, time poverty. The unit of analysis and identification is the individual. The index is calculated for Mexico using data from the Mexican National Institute of Statistics and Geography’s 2020 National Expenses and Income Survey (ENIGH) (INEGI Citation2020), and is estimated using the Alkire-Foster method (Alkire and Foster Citation2011). Multidimensional poverty and the incidence of the different dimensions within it depend not only on the sex of a person but also on their life cycle; for this reason, the measure is calculated for females and males in different age groups.

The next section contains the theoretical framework and the literature review. The methodology follows, and then the results and the empirical analysis are presented. The last section offers conclusions.

2. Theoretical framework and literature review

Haughton and Khandker (Citation2009, 2) define poverty as ‘pronounced deprivation in well-being’. In the conventional view of poverty the more economic resources a person has, the greater their well-being. For measurement purposes, the poor, then, are those with insufficient income or consumption. Poverty is seen largely in monetary terms (Haughton and Khandker Citation2009).

In the 1980s, feminists started to analyze poverty from a gender perspective, identifying the mechanisms by which gender inequalities affect women’s poverty in specific ways (CEPAL Citation2004). These inequalities result from the sexual division of labor and gendered social hierarchies that restrict women’s access to social resources, participation in the labor market, participation in political, economic, and social decisions, and access to an adequate income (CEPAL Citation2004). In the household, gendered social norms dictate women’s opportunities to access resources, education, nutritious food, adequate health care, etc. (Chattier Citation2012).

In line with mainstream measurements of poverty, women’s poverty has also been calculated using monetary-based indicators, which feminists identified as problematic. Due to empirical and conceptual difficulties in disaggregating consumption and income by gender, monetary-based poverty measurement assumes that resources are equally distributed within households: if someone is a member of a poor household, they are considered poor. Therefore, women’s poverty has been measured based on the number headcounts of female household members identified as poor (Klasen Citation2007, 2).

This is not ideal, however, as the distribution of resources within the household is not equal (Agarwal Citation1997; Ilahi Citation2000). Intrahousehold inequalities and household members’ bargaining power depend on gendered social norms and social perceptions, as well as economic resources and support from kinship, the community, and the state (Agarwal Citation1997). Correspondingly, gender, age, and position in the family shape individuals’ reality (Bessell Citation2015).

Most importantly, views of poverty based on material deprivation have been critiqued on theoretical grounds. Anand and Sen (Citation1997, 4) point out that people may be deprived of more than material well-being: they can also lack the opportunity to live a tolerable life. For example, their lives may be shortened, they may be difficult and painful, and so on.

Sen (Citation1990, Citation1999) developed a theoretical framework along these lines that emphasizes the importance of evaluating the social condition according to the richness of human life that emerges from it. Human life is composed of functionings – a series of ‘beings and doings’, such as being well-nourished, being well-fed, having confidence, and being able to read and write. These functionings reflect what a person succeeds in being and doing. Although functionings are an important aspect of well-being, an assessment of these alone would not be complete as it does not reflect a person’s freedom to function in a certain way. Considering the importance of the freedom to acquire functionings, Sen also introduced the notion of capabilities: a person’s potential to acquire a combination of functionings, reflecting their freedom to choose between different ways of living.

In assessing quality of life and poverty, the evaluative space must be people’s ability to achieve functionings. Poverty must be seen as the failure to have certain basic capabilities, rather than low income per se (Sen Citation2006, 34). Income is only one among many instruments by which better capabilities for functioning can be obtained; political and social opportunities, personal characteristics, and the environment in which people live, etc. are also important (Sen Citation2006, 34). In the Capabilities framework, poverty refers to deprivation in dimensions that are indispensable to individuals’ adequate social functioning, and is therefore multidimensional.

Since the 1970s, methodologies have been developed that define and measure multidimensional poverty including various aspects of economic, social, and welfare well-being (Alkire et al. Citation2015), but these continue to use the household as the unit of analysis (Vijaya, Lahoti, and Swaminathan Citation2014). Assessing individual-based poverty is easier using a non-monetary framework such as the Capabilities approach, which enables the identification of individual well-being outcomes (Klasen Citation2007).

Studies comparing the differences between multidimensional measures of poverty at the household level of analysis and individual-level analysis find that analyzes based on the household underestimate gendered poverty differences, demonstrating that measuring the poverty of the individual better reflects deprivations faced by each household member (Vijaya, Lahoti, and Swaminathan Citation2014; Klasen and Lahoti Citation2016; Lekobane Citation2022).

A small number of studies delve into gender differences using only individual-level analysis. Espinoza-Delgado and Klasen (Citation2018) propose an individual-based multidimensional poverty measure for Nicaragua; Wu and Qi (Citation2017) for China; Omotoso, Adesina, and Adewole (Citation2022) for South Africa; and Tekgüç and Akbulut (Citation2022) for Turkey. These studies find important gender gaps in the incidence and intensity of multidimensional poverty, apart from that of Espinoza-Delgado and Klasen (Citation2018), who find small gender gaps.

A multidimensional measure can incorporate dimensions and indicators that reflect women’s structural inequalities and disadvantages. Tekgüç and Akbulut (Citation2022) and Espinoza-Delgado and Klasen (Citation2018) include employment; Lekobane (Citation2022) incorporate security; and Vijaya, Lahoti, and Swaminathan (Citation2014), empowerment, measured by women’s mobility. The difficulty of incorporating such dimensions and indicators specific to women’s disadvantages is the lack of available data, especially when comparing different demographic groups. Data on empowerment, for example, is often only available for women.

This study includes the dimension of time poverty. A person is time-deprived if they are too busy with paid or unpaid work to find enough time for rest, self-care, and leisure (Bardasi and Wodon Citation2006). Time to enjoy leisure and self-care activities such as sleeping, eating, socializing, sports, etc., is an important aspect of well-being and thus has an intrinsic value (Nussbaum Citation2000; Robeyns Citation2003). It affects mental and physical health and the possibility of socializing with others (Sparks et al. Citation2018; Hyde, Greene, and Darmstadt Citation2020).

Time patterns are gendered by social roles and norms. Men engage primarily with their productive role while women are responsible for caring and domestic activities, even if they also engage in paid activities (Blackden and Wodon Citation2006; Gammage Citation2009; Hyde, Greene, and Darmstadt Citation2020), implying that women are more time-pressured than men. This impedes their completion of schooling and engagement in paid employment, and prevents them from working the same number of hours as men, leading to their segregation into lower-paying jobs (Hyde, Greene, and Darmstadt Citation2020).

Although time deprivation is a fundamental aspect of well-being, few multidimensional poverty measures incorporate this dimension. Benvin, Rivera, and Tromben (Citation2016) calculate a multidimensional poverty index(MPI)that includes it for Colombia, Ecuador, Mexico, and Uruguay, using the household as the unit of analysis, and Gammage’s (Citation2009) MPI uses factor analysis including a time dimension for Guatemala based on the individual.

This paper calculates a multidimensional poverty index using the individual as the unit of analysis and identification. Few studies do this to analyze gendered poverty. This index is novel in that it includes time poverty, an important aspect of well-being. As age also shapes individuals’ opportunities to achieve well-being, this MPI compares females and males in different age groups.

3. Methodology

3.1. Alkire-Foster methodology

The Alkire-Foster (AF) methodology (Alkire and Foster Citation2011) is used to estimate a multidimensional poverty index at the individual level. Like any multidimensional poverty methodology, it has both advantages and disadvantages. The appendix presents the methodology and discusses these. This methodology was chosen as it is easy to communicate, can be used with ordinal data, and can be broken down by dimension.

3.2. Data

The dataset used is ‘National Expenses and Income Survey’ (ENIGH) (INEGI Citation2020), which is representative at the national level and the state level. It is conducted every two years and includes data on household income and expenditure (identified at the household level), household members’ sociodemographic characteristics including health and use of time (identified at the individual level), and housing conditions and household equipment (identified at the housing level). The National Council of Evaluation of Social Development Policy (CONEVAL) uses this dataset to provide a national multidimensional poverty measure that incorporates indicators of the population’s income and social rights (education, access to health services, access to social security services, nutrition, and decent housing). Income and nutrition privation are calculated at the household level, and all members of these households are considered poorFootnote2 (CONEVAL Citation2019). CONEVAL does not consider possible intrahousehold differences.

For this paper, the unit of analysis is individuals aged 12 years and above, as data on time use is only available for this age group. shows this population by sex and age group.

Table 1. Mexican population 12 and older, by sex and age group.

ENIGH’s sampling design is probabilistic, stratified, and by conglomerates. From each conglomerate dwellings were selected. Standard errors and confidence intervals are calculated using the Taylor series approximation.

3.3. Dimensions and indicators

This multidimensional poverty measure includes five dimensions: time privation, education, health, housing, and dwelling’s access to basic services (). The choice of dimensions and indicators is based on Nussbaum (Citation2000) and Robeyns’s (Citation2003) lists of central capabilities, and on the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), which have a degree of public consensus and legitimacy (Alkire Citation2013). However, data availability constrained this choice.

Table 2. Indicators and dimensions of the multidimensional poverty index.

Education is both intrinsically and instrumentally valuable, as it is of value in itself and is instrumental in other vital outcomes (Alkire and Santos Citation2014). A person may value knowledge for its own sake, but it can also provide them with greater economic opportunities and jobs; it can open peoples’ minds; give them better information about health issues; and contribute to a more tolerant society (Robeyns Citation2006). An individual is considered deprived in this dimension if they have not completed secondary education. Espinoza-Delgado and Klasen (Citation2018) propose this cut-off point as it is the target of SDG 4, Quality Education. This target is also relevant in the Mexican context, as universal primary education has almost been achieved, but secondary education has not (D’Alessandre and Mattioli Citation2015). In 1934, public provision of primary education became mandatory, but secondary and high school education did not become obligatory until 1993 and 2012 respectively (CONEVAL Citation2019). In 1997, the government implemented its Progresa program,Footnote3 which gave poor mothers conditionalFootnote4 transfers for every child attending school. These transfers were higher for girls than boys because their educational levels were lower (Yaschine Citation2019).

Nussbaum (Citation2000) and Robeyns (Citation2003) recognize health as a dimension of well-being. According to Sen, ‘health is among the most important conditions of human life and a critically significant constituent of human capabilities which we have reason to value’ (Sen Citation2002, 660).

Social health insurance in Mexico is accessible to individuals in formal employment. In 2019, the Health and Well-Being Institute (INSABI) was created to provide health services to all Mexicans without access to social insurance.Footnote5 However, universality in access to health services has yet to be achieved, and the quality of the services provided is questionable (CONEVAL Citation2022). Thus an indicator of effective access to health care is relevant in the Mexican context and is in line with the capabilities framework.

According to Larrañaga (Citation2007), one way to construct an indicator of health is by determining whether a person has previously had a health problem, and if so, whether they searched for and found treatment. An indicator was constructed to identify people who had fallen ill in the previous year and had not sought or received treatment, those who had sought treatment and had had to travel for over an hour and a half to receive it, and those who had had to wait more than an hour and a half to receive treatment.Footnote6

As explained, time for leisure, rest, and self-care is a central capability. Analyzing time privation is especially significant in Mexico, as of 37 countries surveyed by the OECD (Citation2020), Mexico has the highest percentage of people in paid work for 50 h or more per week(27%). Time-use data is incorporated in ENIGH (INEGI Citation2020), which asked how much time individuals spend per week in paid and unpaid work.

Vickery (Citation1977) proposes that the minimum amount of leisure time necessary to maintain a person’s health is 81 h a week (7.6 h a day to sleep, 0.3 to rest, 1.2 to eat, 1.1 for personal care, and 10 free hours a week). This means that total reproductive and productive work should not exceed 87 h a week. If it does, the person is considered deprived in this dimension.Footnote7

Although variables such as housing and access to services are resources and can thus can be problematic in the Capabilities framework, they can be related to material capabilities (Espinoza-Delgado and Klasen Citation2018). The SDGs, participatory exercises, and the Human Rights Act identify them as important (Alkire and Santos Citation2014). Data on housing conditions and access to basic services were collected and identified by the ENIGH (INEGI Citation2020) dataset at the household level. Many of these are semi-public in nature because they are non-excludable (Vijaya, Lahoti, and Swaminathan Citation2014). Vijaya, Lahoti, and Swaminathan (Citation2014) provide the example of a toilet, which is semi-public as it can be used by all household members and all can derive well-being from its use. It is very difficult to identify the ultimate beneficiaries and determine which household members use them more than others (Vijaya, Lahoti, and Swaminathan Citation2014; Espinoza-Delgado and Klasen Citation2018). Following Vijaya, Lahoti, and Swaminathan (Citation2014), these are assumed to be public goods here, accessible to all. The 1983 Mexican Constitution confers the right to a dignified dwelling, yet since the 1990s, policies related to housing acquisition have been based on awarding non-subsidized credits to formal workers. During these years real-estate market built urban dwellings of inadequate size, composition, connectivity, and location. In 2012, the state began to award subsidies for people in rural and urban areas (Olivera and Serrano Citation2022).

The lack of certain household services, such as energy, electricity, and water, can place a greater burden on women, who, due to gendered roles, are mainly responsible for reproductive tasks, than on men. While indicators that capture the extra effort these tasks involve are not available, the possible time burden is represented in the time privation indicator. Deprivation of these services can have an important impact on all household members, including those who do not engage in reproductive activities (Vijaya, Lahoti, and Swaminathan Citation2014).

A living standard dimension is included the indicators of access to basic services were based on CONEVAL (Citation2019), except for its energy indicator. CONEVAL (Citation2019) considers a household deprived if coal or wood are used for cooking or heating food and if the dwelling does not have a chimney. According to WHO (Citation2014, 33), emissions to the outdoor environment reduce the ambient air quality, in turn contributing to lower indoor air quality. For this reason, this paper considers dwellings both with and without a chimney deprived if they use coal or wood for heating.

In terms of the poverty cut-off, this paper uses a value is 0.3, i.e. 3 out of 10 in the total weighted indicators. Following Santos and Villatoro (Citation2016), to be identified as poor a person must experience deprivation in a full dimension, and in some other indicator. Using this poverty cut-off, the poor are considered multidimensionally poor when they are deprived in more than one dimension.

3.4. Data limitations

Due to data limitations it is not possible to include other dimensions of well-being that could evidence gendered privations at the individual level, such as who makes decisions within the household, or violence against women.

The assets a household owns are not included as a dimension in this study. ENIGH (INEGI Citation2020) contains information on asset ownership at the household level. For this paper, while access to basic services in the dwelling and housing are assumed to be accessible to all with equal externalities, it is much more difficult to apply this assumption in the case of assets. There is evidence that access to and control and ownership of household assets are very different for men and women (Agarwal Citation1997; Deere and Doss Citation2006).

Indicators of employment are not included here either. While ENIGH (INEGI Citation2020) has detailed information on employment characteristics, it does not include information about individuals who are available for paid work but are not looking for a job, a category into which a large proportion of Mexican women fall (Feix Citation2020). Furthermore, both caring for children and having a paid job are fundamental capabilities. Valuing paid work over caring, and vice versa, is questionable.

4. Results

4.1. Deprivation by dimension and indicator

shows the uncensored deprivations of males and females. Compared to other dimensions, education is the dimension in which both a larger percentage of Mexicans and a larger percentage of women than men are deprived. A larger percentage of women than men are also deprived of effective access to health services and of time.

Table 3. Percentage h (%) of males and females that are deprived in each indicator.

As shows, the percentage of deprived individuals in each dimension varies greatly by age and sex. In education, the higher the age group, the greater the proportion of individuals without secondary-level education. While less than 10% of young people aged 12–30 lack secondary education, this rises to more than 66% of those over 61. As indicated previously, the Mexican government expanded educational coverage, increasing the school attainment for the younger. The higher government transfers since the mid-90s, for poor families that sent girls to school compared to those who sent boysled to educational levels in women outstripping those of men (Yaschine Citation2019). Thus fewer women than men aged 12–40 are deprived of education, while there is a higher incidence of educational deprivation in women whose age is greater than 51. In Latin America fewer young men complete secondary education than women, due to their incorporation into the labor market. Also, the school system has been inadequate to retain young individuals from families with accumulated social, economic and family disadvantages, especially males (D’Alessandre and Mattioli Citation2015).

Table 4. Proportion (h%) of males and females by age group that are deprived in each indicator.

In the case of health, as expected, the higher the age group, the higher the percentage of people who were ill and did not receive or did not have access to adequate health service. The percentage of deprived women in this dimension is greater than that of men, except for those aged over 61. Case and Deaton (Citation2005, 186) indicate that older women report worse health than older men in several parts of the world, and the reason is unknown.

The percentage of women and men who are time-deprived increases up to the age of 40 and then decreases, coinciding with the reproductive years. Also, while a larger proportion of women is time-deprived than men, the gap between the two sexes increases during the childbearing years (ages 20–40), when women dedicate more time to domestic work and care activities, working more hours overall than men when reproductive activities are considered, especially when they have children (Blackden and Wodon Citation2006; Gammage Citation2009; Hyde, Greene, and Darmstadt Citation2020).

Sex differences by age group in housing and number of people per bedroom are not great, given that, as explained previously, they are semi-public in nature. Interestingly, the age group, the lower the percentage of people living in a household with three or more people per bedroom.

4.2. Multidimensional poverty estimates

shows the multidimensional poverty estimates for Mexican males and females: the multidimensional poverty incidence (h%), the average deprivation shares across the multidimensionally poor, and the adjusted headcount ratio (M0).

Table 5. Multidimensional poverty measures by sex and age group.

The incidence of both male and female multidimensional poverty increases as the age group rises. The fact that a large proportion of the population, lacks education and health, which rises with age could be driving this result. The figures are higher for females than for males for each age group to varying degrees, and are only significant for those aged 21–30 and 51–60. The relative difference for the former age group is even double-digit.

Interestingly, the average share of deprivation does not vary greatly between age groups. The resulting adjusted headcount ratio, however, does increase with age, especially in those over 60: it is also higher for women than for men in the age groups from 20 to 60,Footnote8 and very high for the 21–30 age group. As in Espinoza-Delgado and Klasen’s (Citation2018) results from Nicaragua, the size and the direction of the estimated gender gaps in MPI are mainly driven by the difference in the incidence of poverty.

Estimations of inequality are shown in Table A4 in the Annex. Inequality among the poor is relatively low, and is lower than Espinoza-Delgado and Klasen’s (Citation2018) findings from Nicaragua. It is greater for women than for men aged under 50, and greater for men above that age. Interestingly, inequality increases for both men and women with each age group up to the 31–40 group, and then decreases. In the latter age group the difference between men and women is greater.

4.3. Dimensional and indicator contributions to poverty

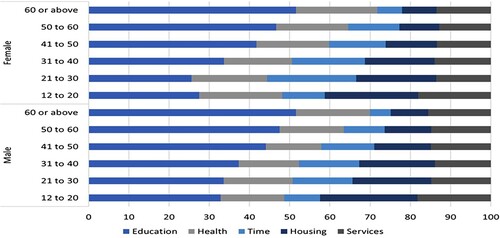

The contribution of each dimension and indicator was calculated by estimating the share of the weighted censored headcount ratio to M0. The complete results are shown in Table A5 in the Appendix. presents a bar graph of the influence of each dimension on poverty by age group.

Education is the dimension that contributes the most to the adjusted headcount ratio (M0), contributing more in men than women, especially as the age groups rise, while the influence of time deprivation on M0 is higher for women than for men. The time dimension is especially significant for women between 21 and 40, at close to 20%. The health dimension is more involved in women’s than men’s adjusted headcount ratio and its contributions also increase with age. The housing and services dimension is most important for younger individuals.

4.4. Robustness analysis

Since the elaboration of an MPI entails decisions on the choice of poverty line (k) and weighting structure (w), it is of interest to discover how the selection of these parameters affects the estimates (Alkire et al. Citation2015).

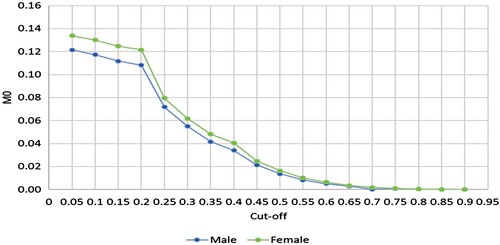

presents the different values of the adjusted headcount ratio (M0) when using different cut-offs (k). The results in terms of females and males of each age group are presented in Table A6 in the annex. For both males and females, the lower the cut-off, the greater the value of M0. At the cut-off 0.65, the value of M0 is already very close to zero, implying that the proportion of Mexicans with a combination of several deprivations is low.

For every cut-off equal to or below 0.4, M0 is significantly greater for women than for men in every age group, excluding those aged 12–20, and when k = 0.4 it is not significant for those aged over 61, dropping even lower for women than for men in the latter age group when the cut-off exceeds this value.

To test whether the findings are robust to a range of weights, M0 was estimated for males and females in different age groups using four alternative weighting groups with a cut-off of k = 0.3.

The four weighting structures and results can be found in Table A7 in the appendix. The adjusted headcount is greater when the weights on education are larger. This is expected as a bigger percentage of both poor and non-poor individuals, and especially those who are older, experience this deprivation. When the weighting is higher for health and time deprivations, the relative difference between women and men increases in all age groups. When housing and services have higher weighting, the gap in adjusted deprivations by sex is reversed in some age groups, based on the education dimension. If education is weighted more heavily, the adjusted headcount ratio is greater for men than for women in the older age range, while with a low weighting, this happens to young people. Therefore the gap in the adjusted headcount ratio between women and men in each age group varies depending on whether a higher or lower weighting is assigned to the dimension to which each experiences a higher deprivation.

4.5. Determinants of multidimensional poverty

A logit regression was estimated to investigate the determinants of the incidence of multidimensional poverty. Two different models were specified: the first included interaction terms to explore sex and age, age squared, ethnicity, and area of residence. The second model added interaction terms of sex and marital status as well as the above ().

Table 6. Logit regression results.

Compared to being single, all types of marital status except being divorced increase the likelihood of poverty, and more so for women, consistent with their bearing the brunt of reproductive activities. For men, being married increases the probability of being poor to a greater degree than being separated, while for women it is the other way around.

Age increases the possibility of being poor at decreasing rates. Age and age squared of women coefficients are significant when sex and marital status interaction effects are not included in the model, and are not significant when they are included.

Being indigenous and living in a rural area both increase the likelihood of being multidimensionally poor. Rural areas in Mexico have less access to health, educational, and dwelling service infrastructure. While women in rural areas are more likely to be poor than men, yet indigenous women are surprisingly not, and therefore policies should focus on these populations. Finally, those living in the north of Mexico are less likely to be poor than those living in Central Mexico, while living in the south of the country, which is a poorer area, are more likely to be poor.

5. Conclusions

The results show that the incidence of multidimensional poverty and of adjusted multidimensional poverty depend greatly on sex and age group, as is the case of the contribution to poverty of each dimension. Deprivation of education and effective access to health services contribute more to the MPI in individuals aged over 60, and to women. Time poverty is an important component for women aged 20–40. Housing and service deprivations have a greater effect on the poverty levels of the young. This heterogeneity shows the importance of disaggregating the MPI based on the different characteristics of household members. It also helps to target social policy better.

For example, strengthening adult education policy is important, as are ensuring the quality of educational institutions and preparing teachers, to avoid the dropout of young learners dropping outfrom school, especially boys. Expanding the coverage and quality of public health services, with a gender perspective, should also be a priority. Access to subsidized housing of adequate size and materials, especially for the young, should also be furthered.

Women bear the brunt of care activities, and thus their time deprivation is an important contributor to their MPI. Mexico’s National Care System includes a set of policies, and programs for everyone who needs and provides care, and recognizes their rights, as approved by the Deputy’s Chamber in 2020. Since then, the Senate has not discussed it. It is fundamentally important that this proposal is discussed and approved. Policies that ensure employers are complying with regulatory working hours and extending school hours, allowing mother’s (and father’s) labor participation, are also necessary to reduce Mexicans’ time deprivation (Barrera and Trujano Citation2022).

The results evidence the fundamental significance of focusing on the capabilities approach based on its holistic view of well-being. Further, the incorporation of gendered dimensions in multidimensional poverty measures is essential to enable effective analysis of the patterns of poverty in society. The findings show that time poverty strongly affects women, especially when they are of reproductive age; men are also affected, although to a lesser extent. Unfortunately, surveys seeking to incorporate gendered poverty dimensions are still restricted by lack of data. For example, the data used here is not disaggregated at the individual level (nor by sex or age) of important indicators such as access to assets or malnutrition, and fails to incorporate gendered information such as decisions in the household, violence against women, etc. It is hoped that national surveys will incorporate the gender dimension more fully in the future.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (60 KB)Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (63.8 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 Gender refers to the cultural construction of sexual differences. It denotes the distinctions between feminine and masculine and the relationship between them (CEPAL Citation2004).

2 A person is considered multidimensionally poor when the exercise of at least one of her social rights is not guaranteed and if their income is also insufficient to buy the goods and services required to fully satisfy their needs (CONEVAL Citation2019).

3 Renamed Oportunidades in 2012 and Prospera in 2014.

4 These were conditional on children’s school attendance and health checks.

5 Previous to the reform a national public insurance programme ‘Seguro Popular’ was in place.

6 Excludes individuals who did not look for medical attention because they did not want to or it was unnecessary or because they self-medicated. People did not search for attention for one or more of the following reasons: there was nowhere they could go to be treated; they had no money to pay; the hospital or clinic was too far away; they were not attended to at the medical unit; they did not trust the staff at the medical unit; they were mistreated when attended to; they did not speak the same language; they had to wait too long to be seen; were not given the medication they needed; the medical unit was not open; a household member prevented them going; no one could take them; there was no time.

7 The survey does not distinguish the hours when people multitask between activities. Total time dedicated to reproductive activities is considered work, regardless of whether it is done at the same time as leisure or self-care activities.

8 Although the confidence interval overlaps for those between 41 and 50.

References

- Agarwal, B. 1997. “‘Bargaining’ and ‘Gender Relations: Within and Beyond the Household.” Feminist Economics 3 (1): 1–51. doi:10.1080/135457097338799.

- Alkire, S. 2013. “Choosing Dimensions: The Capability Approach and Multidimensional Poverty.” In The Many Dimensions of Poverty, edited by N. Kakwani, and J. Silber, 89–120. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Alkire, S., and J. Foster. 2011. “Counting and Multidimensional Poverty Measurement.” Journal of Public Economics 95 (7-8): 476–487. doi:10.1016/j.jpubeco.2010.11.006.

- Alkire, S., J. M. Roche, P. Ballon, J. Foster, M. E. Santos, and S. Seth. 2015. Multidimensional Poverty Measurement and Analysis. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Alkire, S., and M. E. Santos. 2014. “Measuring Acute Poverty in the Developing World: Robustness and Scope of the Multidimensional Poverty Index.” World Development 59: 251–274. doi:10.1016/j.worlddev.2014.01.026.

- Anand, S., and A. Sen. 1997. “Concepts of Human Development and Poverty: A Multidimensional Perspective.” Human Development Report. New York: UNDP.

- Bardasi, E., and Q. Wodon. 2006. “Measuring Time Poverty and Analyzing Its Determinants: Concepts and Application To Guinea.” In Gender, Time Use, and Poverty in Sub-Saharan Africa, edited by C. M. Blackden, and W. Quentin, 75–95. Washington: World Bank Publications.

- Barrera, A., and M. A. Trujano. 2022. “El Sistema Nacional de Cuidados en México existe solo en papel.” Serendipia, December 28, 2022. https://serendipia.digital/derechos-de-las-mujeres/sistema-nacional-de-cuidados-en-mexico/.

- Benvin, E., E. Rivera, and V. Tromben. 2016. “Propuesta de un indicador de bienestar multidimensional de uso del tiempo y condiciones de vid"a aplicado a Colombia, el Ecuador, Mexico y el Uruguay.” Revista Cepal 118: 121–145. doi:10.18356/b1115e4f-es. Accessed October 3, 2023. http://hdl.handle.net/11362/40033.

- Bessell, S. 2015. “The Individual Deprivation Measure: Measuring Poverty as if Gender and Inequality Matter.” Gender & Development 23 (2): 223–240. doi:10.1080/13552074.2015.1053213.

- Blackden, Mark, and Q. Wodon. 2006. “Gender, Time use, and Poverty: Introduction.” In Gender, Time use, and Poverty in sub-Saharan Africa, edited by C. M. Blackden, and Q. Wodon, 1–10. Washington: World Bank Publications.

- Bradshaw, S., S. Chant, and B. Linneker. 2017. “Gender and Poverty: What We Know, Don’t Know, And Need to Know for Agenda 2030.” Gender, Place & Culture 24 (12): 1667–1688. doi:10.1080/0966369X.2017.1395821.

- Case, A., and A. S. Deaton. 2005. “Broken Down by Work and Sex: How Our Health Declines.” In Analyses in the Economics of Aging, edited by D. Wise, 185–212. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- CEPAL. 2004. Entender la pobreza desde la perspectiva de género. Santiago de Chile: CEPAL/UNIFEM. Accessed September 20, 2022. https://repositorio.cepal.org/bitstream/handle/11362/5918/S0400008_es.pdf?sequence = 1#:~:text = Adem%C3%A1s%20de%20destacar%20que%20la,y%20necesidades%20tambi%C3%A9n%20son%20diferentes.

- Chant, S. 2006. “Re-Thinking the ‘Feminization of Poverty’ in Relation to Aggregate Gender Indices.” Journal of Human Development 7 (2): 201–220. doi:10.1080/14649880600768538.

- Chattier, P. 2012. “Exploring the Capability Approach to Conceptualize Gender Inequality and Poverty in Fiji.” Journal of Poverty 16 (1): 72–95. doi:10.1080/10875549.2011.639861.

- CONEVAL. 2019. Metodología para la medición multidimensional de la pobreza en Mexico. 3rd ed. Mexico City: CONEVAL. Accessed September 15, 2022. https://www.coneval.org.mx/InformesPublicaciones/InformesPublicaciones/Documents/Metodologia-medicion-multidimensional-3er-edicion.pdf.

- CONEVAL. 2022. Evaluación Estratégica de Salud. Primer Informe. Mexico City: CONEVAL. Accessed November 10, 2022. https://www.coneval.org.mx/InformesPublicaciones/Paginas/Mosaicos/Evaluacion_Estrategica_de_Salud_informe_2022.aspx#:~:text = Primer%20Informe.&text = Con%20la%20Evaluaci%C3%B3n%20Estrat%C3%A9gica%20de,General%20de%20Salud%20(LGS).

- D’Alessandre, V., and M. Mattioli. 2015. Por qué los adolescentes dejan la escuela? Comentarios a los abordajes conceptuales sobre el abandono escolar en el nivel medio. Cuaderno 21. Paris: SITEA, UNESCO.

- Deere, C. D., and C. R. Doss. 2006. “The Gender Asset Gap: What Do We Know and Why Does It Matter?” Feminist Economics 12 (1-2): 1–50. doi:10.1080/13545700500508056.

- Espinoza-Delgado, J., and S. Klasen. 2018. “Gender And Multidimensional Poverty In Nicaragua: An Individual-Based Approach.” World Development 110: 466–491. doi:10.1016/j.worlddev.2018.06.016.

- Feix, N. 2020. “Mexico y la crisis de la COVID-19 en el mundo del trabajo: respuestas y desafíos.” Panorama Laboral de tiempos de la COVID-19. Organización Internacional del Trabajo (OIT). Accessed March 10, 2023. https://repositorio.cepal.org/bitstream/handle/11362/25902/1/LCmexL955_es.pdf.

- Gammage, S. 2009. Género, pobreza de tiempo y capacidades en Guatemala: un análisis multifactorial desde una perspectiva económica. Mexico City: Comisión Económica para America Latina y el Caribe (CEPAL).

- Haughton, J., and S. R. Khandker. 2009. Handbook on Poverty and Inequality. Washington: World Bank Publications. Accessed September 15, 2023. https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/11985.

- Hyde, E., M. E. Greene, and G. L. Darmstadt. 2020. “Time Poverty: Obstacle to Women’s Human Rights, Health And Sustainable Development.” Journal of Global Health 10 (2): 1–5. doi:10.7189/jogh.10.020313.

- Ilahi, Nadeem. 2000. The Intrahousehold Allocation of Time and Tasks: What Have We Learnt from The Empirical Literature? Gender and Development, Working Paper Series 13. Washington, DC: World Bank.

- INEGI. 2020. ENIGH, “Encuesta Nacional de Ingresos y Gastos de los Hogares.” INEGI. Accessed October 10, 2022. https://www.inegi.org.mx/programas/enigh/nc/2020/.

- Klasen, S. 2007. “Gender-Related Indicators of Well-Being.” In Well-Being: Studies in Development Economic and Policy, edited by M. McGillivray, 167–192. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Klasen, S., and R. Lahoti. 2016. “How Serious Is the Neglect of Intrahousehold Inequality in Multi-Dimensional Poverty Indices?”. doi:10.2139/ssrn.2742083.

- Larrañaga, O. 2007. La medición de la pobreza en dimensiones distintas al ingreso. Serie estudios estratégicos y prospectivos 58. Santiago de Chile: CEPAL. Accessed September 25, 2022. https://repositorio.cepal.org/handle/11362/4760.

- Lekobane, K. R. 2022. “Leaving No One Behind: An Individual-Level Approach to Measuring Multidimensional Poverty in Botswana.” Social Indicators Research 162 (1): 179–208. doi:10.1007/s11205-021-02824-2.

- Nussbaum, M. 2000. “Women’s Capabilities and Social Justice.” Journal of Human Development 1 (2): 219–247. doi:10.1080/713678045.

- OECD. 2020. Better Life Index. Accessed April 2, 2023. https://www.oecdbetterlifeindex.org/.

- Olivera, G., and O. Serrano. 2022. “Vivienda en México, un problema de calidad, de habitabilidad, del barrio y de la ciudad.” Revista Estado y Políticas Públicas 19: 143–171. https://revistaeypp.flacso.org.ar/files/revistas/1667932268_143-171.pdf.

- Omotoso, K. O., J. Adesina, and O. G. Adewole. 2022. “Profiling Gendered Multidimensional Poverty and Inequality in Post-Apartheid South Africa.” African Journal of Science, Technology, Innovation and Development 14 (2): 564–576. doi:10.1080/20421338.2020.1867363.

- Robeyns, I. 2003. “Sen’s Capability Approach and Gender Inequality: Selecting Relevant Capabilities.” Feminist Economics 9 (2-3): 61–92. doi:10.1080/1354570022000078024.

- Robeyns, I. 2006. “Three Models of Education: Rights, Capabilities and Human Capital.” Theory and Research in Education 4 (1): 69–84. doi:10.1177/1477878506060683.

- Santos, M. E., and P. Villatoro. 2016. “A Multidimensional Poverty Index for Latin America.” Review of Income and Wealth 64 (1): 52–82. doi:10.1111/roiw.12275.

- Sen, A. 1990. “Development as Capability Expansion.” In The Community Development Reader, edited by J. DeFilippis, and S. Saegert, 3–16. New York: Routledge.

- Sen, A. 1999. Commodities and Capabilities. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Sen, A. 2002. “Why Health Equity?” Health Economics 11 (8): 659–666. doi:10.1002/hec.762.

- Sen, A. 2006. “Conceptualizing and Measuring Poverty.” In Poverty and Inequality, edited by D. B. Grusky, and R. Kanbur, 30–46. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

- Sparks, K., C. Cooper, Y. Fried, and A. Shirom. 2018. “The Effects of Hours of Work on Health: A Meta-Analytic Review.” In Managerial, Occupational and Organizational Stress Research, edited by C. L. Cooper, 451–468. London: Routledge.

- Tekgüç, H., and B. Akbulut. 2022. “A Multidimensional Approach to The Gender Gap in Poverty: An Application for Turkey.” Feminist Economics 28 (2): 119–151. doi:10.1080/13545701.2021.2003837.

- Vickery, C. 1977. “The Time-Poor: A New Look at Poverty.” Journal of Human Resources 12 (1): 27–48. doi:10.2307/145597.

- Vijaya, R. M., R. Lahoti, and H. Swaminathan. 2014. “Moving from The Household to the Individual: Multidimensional Poverty Analysis.” World Development 59: 70–81. doi:10.1016/j.worlddev.2014.01.029.

- WHO. 2014. WHO Guidelines for Indoor Air Quality: Household Fuel Combustion. Geneva: World Health Organization. Accessed October 12, 2022. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/141496/9789241548885_eng.pdf.

- Wu, Y., and D. Qi. 2017. “A Gender-Based Analysis of Multidimensional Poverty in China.” Asian Journal of Women’s Studies 23 (1): 66–88. doi:10.1080/12259276.2017.1279886.

- Yaschine, Iliana. 2019. Progresa-Oportunidades-Prospera, veinte años de historia. En Hernández Licona, Gonzalo, De la Garza, Thania, Zamudio, Janet. y Yaschine, Iliana (coords.) (2019). El Progresa-Oportunidades. Prospera, a 20 años de su creación. Ciudad de Mexico: CONEVAL.