?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

The purpose of this study is to examine whether foreign direct investments are a blessing or a curse for capital accumulation in developing countries. Data were collected for 16 developing countries over the period 2005–2018. An Arellano-Bover/Blundell-Bond dynamic panel estimation method was adopted to analyze the physical capital accumulation effect of foreign direct investments. Our analysis indicates that for every percentage increase in foreign direct investment inflows to developing countries, physical capital increases by 2.31 percent. In addition, a random-effect panel estimation was implemented to analyze the effect of foreign direct investments on human capital. For a one-percent increase in foreign direct investments, human capital increases by 2.38 percent. The results of our regressions show that not only the volume but also the type of foreign direct investment matters for capital formation in developing countries. Specifically, foreign direct investments in the secondary sector have a statistically significant positive effect on both physical and human capital. By contrast, foreign direct investments in the primary and tertiary sectors have a negligible effect. Our analysis suggests that developing countries would benefit from investing more resources in education and opening up their economies to attract foreign direct investments, particularly in the manufacturing sector.

1. Introduction

Capital plays an important role in the development process (Solow Citation1956; Agosin and Mayer Citation2000; Misun and Tomsik Citation2002). However, capital accumulation in developing countries is very low (Ahmad et al. Citation2018; Sucubasi et al. Citation2020). External sources of capital, such as foreign direct investment (FDI), are preferable for developing countries as they lack capital (Apergis, Katrakilidis, and Tabakis Citation2006; Ugwuegbe, Modebe, and Edith Citation2014). FDI is an investment by a multinational enterprise (MNE) that does business in at least one country other than its home country. FDIs come in the form of new investments, intercompany loans (loans from parent companies to subsidiaries), and reinvestment of profits in FDI-receiving countries. Compared to other types of capital flows, FDI is considered more stable and less irreversible (Harms and Méon Citation2018).

Countries with more FDI are transforming faster (Misun and Tomsik Citation2002). Developing countries have therefore tried to attract more FDI by opening their economies and offering various incentives. Consequently, between 1990 and 2018, FDI inflows to developing countries increased 20-fold from $34.65 billion to $706 billion (United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) Citation2019, Citation2021). However, its effect on domestic capital accumulation (both physical and human) is ambiguous.

Some scholars argue that countries with higher FDI stocks have greater accumulations of physical capital. It is argued that FDI promotes local capital formation by providing capital goods that cannot be produced locally, such as modern machinery, seeds, and spare parts (Apergis, Katrakilidis, and Tabakis Citation2006). It also augments the domestic capital by providing financial capital (including hard currency) to fund domestic operations. FDI can increase local liquidity and alleviate financial constraints on local firms (Jude Citation2018). FDI forces the local firms to invest more to compete with MNEs, renewing and expanding their capital stock (example, by purchasing new machinery) (Al-Sadig Citation2012). Finally, they also contribute to capital formation by providing infrastructure (transport, schools, hospitals, telecommunications, etc.) (Al-Sadig Citation2012).

The Solow theory asserts that FDI produces only a short-term growth effect despite an increase in physical capital (Solow Citation1956). It is due to the fact that as total capital accumulation increases, returns on additional capital will decrease. However, endogenous growth theory and most scholars believe that FDI contributes more to the domestic economy not only by providing physical capital but also by enhancing human capital (through technology transfer and improved education) (Lucas Citation1988). Technology transfer from MNES to local firms can be occurred through the following channels: (i) experiential learning and observation, (ii) competitiveness, (iii) labor mobility (domestic firms hire workers previously worked for or trained by foreign firms), and (iv) value chain connectivity (vertical and horizontal) (Fahinde et al. Citation2015; Demena and van-Bergeijk Citation2019). Successful technology transfer from MNEs to local companies requires highly skilled workers. However, human capital in developing countries is very low and continues to hinder the technology transfer from foreign firms to domestic firms in these countries. Therefore, it is necessary to study the effect of FDI on human capital growth, a topic that has received little attention so far.

However, there is still debate about the effect of FDI on human capital in developing countries. Some authors argue that FDI acts as a catalyst for human capital development. First, the education sector is a potential area for MNEs to invest in developing countries. The experience of MNEs in developing countries shows that they can invest in the education sector through the establishment of primary schools and universities to provide foreigners and local residents with access to quality education (Willem Citation2002). Second, MNEs pay higher wages to highly skilled workers to avoid turnover and technology spillovers (Blomstrom and Kokko Citation2003; Soltanpanah and Kariml Citation2013; Abubakar, Kassim, and Yusoff Citation2015; Polloni-Silva et al. Citation2021). Raising wages for skilled workers by MNEs, therefore, motivates individuals to acquire more skills through education in developing countries (Lu 2022). Third, it also increases the resources available to finance education. For example, more FDI would stimulate economic growth and tax revenue from capital, labor, or both, allowing governments in developing countries to increase investment in the education sector to encourage school enrollment (Demena and van-Bergeijk Citation2019). FDI increases school attendance not only through taxes but also by providing good, high-paying jobs that allow parents to send their children to school instead of going to work. Finally, MNEs can also take on corporate social responsibility (CSR) to build schools and help students in local communities (Goyal Citation2006; Sun and He Citation2014; Bello, Othman, and Khairri Shariffuddin Citation2017; Ogbuagu and Onyeike Citation2021).

On the other side, some authors, such as Wang and Zhuang (Citation2021), argue that FDI significantly reduces school enrollment rates in developing countries. MNEs employ not only skilled but unskilled labor as well, which increases the opportunity cost of attending school and thus increases the dropout rate (Atkin Citation2016). Their argument rests on two points. First, MNEs often come to developing countries for low labor costs, making their wages unattractive to educated workers. Second, they do not hire highly skilled workers from developing countries. This is because the type of FDI that often goes to developing countries is FDI that uses outdated technology and requires large numbers of unskilled workers led by a small number of foreign managers.

It is misleading to use the total FDI to draw conclusions about whether the FDI has a positive, negative, or neutral effect on physical or human capital. In practice, the quality of FDI varies by sector, as MNEs behave differently in terms of their motives, modes of entry, linkages with local firms, types of workers they employ, and types of products they seek to offer in local markets (Misun and Tomsik Citation2002: Apergis, Katrakilidis, and Tabakis Citation2006; Budang and Hakim Citation2020). For example, FDI in manufacturing often takes the form of ‘greenfield’ investments that introduce new types of capital goods and innovative technologies to developing markets (Agosin and Mayer Citation2000; Jude Citation2018). Moreover, it has strong vertical and horizontal links with domestic businesses, enabling domestic firms to generate additional physical capital (Agosin and Mayer Citation2000; Chen, Yao, and Malizard Citation2017). Therefore, FDI in manufacturing sector will significantly boost the growth of physical capital in developing countries. On the other side, FDI into the services sector often takes the form of mergers and acquisitions (M&A), where foreign investors purchase existing assets through privatization or other initiatives. Therefore, FDI into the service sector may not directly contribute significantly to improving the physical capital of developing countries (Misun and Tomsik Citation2002). FDI in the primary sector tends to be extractive in nature and thus more likely to reduce domestic physical capital through exports of minerals and commodities (Soe Citation2020).

Regarding human capital, FDI in mining and agriculture discourages school enrollment. This is because FDI into these sectors tends to employ low-paid and unskilled workers such as children and girls (Doytch, Thelen, and Mendoza Citation2014; Kechagia and Metaxas Citation2023). By contrast, FDI in manufacturing increases school enrollment. This is because it is likely to boost national economic growth and create significant employment opportunities compared to other sectors (Doytch, Thelen, and Mendoza Citation2014). Thus, parents can afford to pay education fees for their children, and the country can invest in education. A counter-argument, however, is that child labor is more likely to be used when the manufacturing sector outsources work to microenterprises, small businesses (SMEs), and the informal economy (Narula Citation2019). Microenterprises and SMEs often employ women and children, resulting in lower school enrollment and reduced human capital formation. Another argument is that the demand for skilled workers in the service sector is higher than in other sectors, encouraging locals to pursue up-skilling (Doytch, Thelen, and Mendoza Citation2014; Nguyen et al. Citation2020).

Therefore, there is generally no a clear image on the effect of FDI on capital formation in developing countries. The effect of FDI on capital formation is negative, neutral, or positive. In other words, some scholars have demonstrated that FDI improves capital accumulation (Apergis, Katrakilidis, and Tabakis Citation2006; Lean and Tan Citation2011; Al-Sadig Citation2012; Soltanpanah and Kariml Citation2013; Rath and Bal Citation2014; Ugwuegbe, Modebe, and Edith Citation2014; Polloni-Silva et al. Citation2021), while others have found that FDI impedes capital accumulation (Eregha Citation2012; Liu et al. Citation2014; Zhuang Citation2016; Fahinde et al. Citation2015; Ahmad et al. Citation2018; Budang and Hakim Citation2020). Some studies (e.g. Ahmed et al. Citation2015) point out that FDI inflows follow a neutral hypothesis (neither domestic investment crowds in nor crowds out). This suggests that the overall effect of FDI in developing countries may be inconclusive.

Empirical studies to date have yielded conflicting results, as all studies used a single dimension of physical or human capital to measure capital accumulation (domestic investment). It also does not adequately address the effect of sector-specific FDI on capital accumulation in developing countries. The aim of this study is therefore to determine to what extent FDI in developing countries contribute to the growth of capital accumulation, given the nature of FDI and the question of capital measurement. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first attempt to examine the relationship between FDI and capital formation in developing countries, using both physical and human capital separately and considering the nature of FDI. However, this paper is limited, as data are available for 16 developing countries over a 14-year period (2005–2018).

The rest part of this study is organized as follows. Section 2 presents relevant theories and analyses of the empirical literature from previous studies. Study areas, data, econometric models, and estimation methods are described in Section 3. Section 4 presents descriptive and econometric regression results and discussion. The conclusions and policy recommendations of this study are presented in Section 5.

2. Review of related literatures

2.1. Theoretical review

To better understand how FDI affects capital accumulation in developing countries, it is important to look at both theoretical and empirical studies. It is important to note that modernization theory and dependency theory examine FDI in different ways in relation to its economic contribution to the host country. The former focuses on benefits, and the latter on costs. Modernization theory is a broad type of theory that bases its arguments on neoclassical principles and endogenous theory. It claims that FDI promotes capital accumulation and technology, which are essential for economic growth in developing countries. The Solow theory of growth states, for example, that FDI boosts capital stock and promotes domestic industry growth through new technology transfer (Solow Citation1956). Furthermore, endogenous growth theory assumes that FDI provides not only physical capital but also technical and managerial knowledge and skills, leading to the accumulation of human capital (Lucas Citation1988; Romer Citation1990; Grossman and Helpman Citation1991).

By contrast, dependency theory argues that FDI hurts developing countries beacuse MNEs are less likely to contribute to government revenues (because of tax cuts, tax avoidance, and tax evasion) (Beer Citation1999). They are also more likely to use capital-intensive technologies in extractive ways, leading to inappropriate relationships with domestic firms and discouraging local entrepreneurship (Weeks Citation1981). They are also often concerned with repatriating profits rather than inflowing capital and reinvesting profits into developing countries (Santos Citation1970). Raul Prebisch, who served as Executive Director of UCTAD in the 1960s, pointed out that FDI can reduce the prices of different commodities, ultimately exacerbate underdevelopment. (Namkoong Citation1999).

Moreover, as MNEs tend to exploit cheap labor and natural resources, developing countries are less likely to benefit from knowledge spillovers, productivity gains, and improved human capital (Frank Citation1978). Chilean economist Osvaldo Sunkel notes that FDI promotes exports of raw materials and imports of manufactured goods, leading to worsening trade, a lower accumulation of physical capital, and underdevelopment (Sunkel and Girvan Citation1973). Brazilian economist Celso Furtado also notes that FDI in developing countries tends to focus on profitable export-oriented sectors, while local firms focus on less profitable and less productive sectors. Because of the focus, they argue that it creates a dual economy (Loureiro, Rugitsky, and Saad-Filho Citation2020). They are also so large and technologically advanced that local businesses cannot compete on the open market, leading to a crowding-out effect (Santos Citation1970).

The effect of FDI on human capital accumulation is also ambiguous. According to the theory of Basu and Van (Citation1998), when income is insufficient, parents prefer to send their children to work rather than school. In this theory, FDI improves human capital by providing higher wages even to unskilled workers, enabling families to send their children to school. A theory proposed by Blomstrom and Kokko (Citation2003) suggests that MNEs offer attractive employment opportunities for skilled workers in host countries. Outstanding graduates can benefit from the attractive employment opportunities offered by MNEs, motivating talented students to complete both secondary and tertiary education. Atkin (Citation2016), however, claims that the opportunity cost of education determines whether FDI affects human capital positively or negatively. This means that the opportunity cost of school increases as the wages of unskilled and child workers rise, thereby increasing dropout rates. It is therefore questionable whether MNEs in developing countries are motivated by low or highly-skilled workers. It is the subject of empirical research that answers the question, ‘Does FDI promote human capital formation in developing countries?’

2.2. Empirical evidence

2.2.1. Physical capital accumulation

According to panel integration and co-integration testing by Apergis, Katrakilidis, and Tabakis (Citation2006), FDI inflows stimulated domestic capital formation in 30 developing countries during the period 1992–2002. It is recognized that FDI affects capital formation in developing countries through many channels, such as the provision of more advanced production technology, improved organizational and managerial skills, marketing expertise, and market access. In a study using Malaysian data from 1970 to 2009, Lean and Tan (Citation2011) found a complementary relationship between FDI and local investment. Using the generalized method of moments (GMM), Al-Sadig (Citation2012) reported that FDI significantly increased capital accumulation in developing countries between 1970 and 2000. It is noted that the availability of human capital in the host country determines the effectiveness of FDI in low-income countries. The high availability of a well-educated labor force increases the efficiency of FDI in accumulating capital.

Soltanpanah and Kariml (Citation2013) found that FDI leads to knowledge transfer to local workers via education and training, as well as new skills, information, and technology. Similar results were reported by Rath and Bal (Citation2014) for India over the period 1978–2018 using vector autoregressive (VAR) estimation. Ugwuegbe, Modebe, and Edith (Citation2014), using ordinary least-squares (OLS) estimates, conclude that FDI has a significant long-term positive effect on the accumulation of physical capital in Nigeria. Based on fixed effects generalized least squares (FEGLS), Polloni-Silva et al. (Citation2021) have found that FDI enhances human capital status in Brazil. This is because MNEs are paying their employees better wages and allowing them to invest in the education and health of their families.

By contrast, Eregha (Citation2012), based on a study of 10 countries of the Economic Community of West African States (ECUWAS) from 1970 to 2008, argues that FDI has no positive effect on capital accumulation. The failure of developing countries to benefit from technological spillovers has been pointed out as a result of a lack of human capital and technical know-how. On the other hand, other scholars agree that FDI has a negative impact on the accumulation of physical capital. Fahinde et al. (Citation2015) found that FDI has a significant negative effect on physical capital formation in the economies of the West African Economic and Monetary Union (WAEMU). This is due to a weak technology transfer. MNEs do not hire local workers in positions where they can acquire knowledge. GMM results from Ahmad et al. (Citation2018) in China, based on data collected in 30 provinces between 2000 and 2014, also found that FDI had a negative effect on capital formation due to its polluting characteristics. Budang and Hakim (Citation2020) also observed negative effects of FDI using fixed estimates for 36 Asian countries from 1993 to 2016.

There is some ambiguity about the generalization of the impact of total FDI on physical capital accumulation, although some argue that it is sector-specific. Despite the fact that FDI has no overall effect on capital accumulation in Uganda, Ahmed et al. (Citation2015) found that sector-specific FDI has a crowding-out effect in the financial, construction, and agricultural sectors. However, FDI has a crowding-in effect on the mining and wholesale sectors. FDI in the energy, transport, and manufacturing sectors has a positive but insignificant effect on capital formation. Autoregressive distributed lag model (ARDL) estimation by Shah et al. (Citation2020) shows that FDI in manufacturing and services boosts domestic investment in Pakistan. On the other hand, analysis shows that FDI in the primary sector industries does not have a significant effect on capital formation. Soe (Citation2020) analyzed panel data for 15 regions in Myanmar from 2012 to 2017 and found that the crowd-in effect of FDI was found in the non-oil and gas sectors. This is a result of weak linkages between FDI and domestic investment in the oil and gas sector. Djokoto (Citation2021) and Nyiwul and Koirala (Citation2022) found conflicting results on the effect of agricultural FDI on capital accumulation in developing countries. The former argues that FDI in agriculture has negative long-term effects, while the latter has positive effects on domestic capital formation.

2.2.2. Human capital formation

This section examines how FDI affects human capital accumulation through formal education. For example, the empirical results of Neumayer (Citation2005) indicate that developing countries with high FDI stocks have fewer out-of-school children. This is justified by the fact that FDI boosts economic growth while indirectly reducing the incidence of child labor. In Nigeria, Bello, Othman, and Khairri Shariffuddin (Citation2017) highlight the major role that MNEs play in improving school enrollment through corporate social responsibility. According to the authors, MNEs facilitate school enrollment by providing schools with access to information and communication technology (ICT), paying student tuition fees, and providing school furniture (tables, chairs, and desks). Evidence from China, by Sun and He (Citation2014), shows that FDI has a positive effect on school enrollment in the presence of a high degree of financial deregulation.

However, Liu et al. (Citation2014) found that FDI in China has a negative effect on human capital. A study by Wang and Zhuang (Citation2021) found that between 1980 and 2014, FDI reduced school enrollment rates for both boys and girls in 80 developing countries, but it is statistically significant only for girls. It gives women access to formal employment that was previously not possible without a college education. Finally, based on data from nine African countries, Kaulihowa and Adjasi (Citation2019) provide evidence that FDI has no significant impact on strengthening human capital in developing countries.

This suggests that the effect of FDI on human capital formation is ambiguous. This may be due to the use of total FDI, which is based on the assumption that FDI is of uniform quality across sectors. FDI skill requirements and wage levels in the primary, secondary, and tertiary sectors may differ. Thus, it may be more credible to expect a heterogeneous effect of FDI on human capital across sectors. For example, according to Doytch, Thelen, and Mendoza (Citation2014), FDI in the mining and agricultural sectors increases child labor and reduces school enrollment rates. The authors say it is shocking those children as young as six in Mali have been forced to work in mining, leading to increased absenteeism and school dropouts.

Regarding FDI in manufacturing, Wang (Citation2011) investigated the effect of FDI in various industries on secondary school enrollment in the United States (US) and found that manufacturing FDI was associated with increased secondary school enrollment. Doytch, Thelen, and Mendoza (Citation2014) reported that manufacturing FDI has a positive indirect effect on schooling by boosting economic growth. Similarly, according to Zhuang (Citation2016), the presence of FDI in the manufacturing sector is also associated with a higher secondary school enrollment rate in China. Ibarra-Olivo (Citation2021) and Saucedo, Ozuna, and Zamora (Citation2020) conducted an empirical study in Mexico and found that FDI in both manufacturing and services reduces human capital by increasing the relative wages of unskilled workers and the opportunity cost of education. Finally, from a service sector perspective, the study by Doytch, Thelen, and Mendoza (Citation2014) showed that FDI in the service sector, especially the financial sector, has a large positive effect on school enrollment. This means that FDI in the financial sector will allow access to credit to pay for school tuition, reduce poverty, and allow children to go to school rather than work to supplement their household income.

2.3. Summary

There is no consensus in the theoretical literature on the effect of FDI on physical and human capital. Empirical evidence also lacks conclusive evidence for the effect of FDI on capital accumulation in developing countries. Moreover, the empirical studies conducted so far in developing countries are not sufficiently broad and comprehensive. This is because most studies are conducted at the national or regional level rather than grouping regions such as Africa, Asia, and Latin America together. In the literature so far, no study has considered the nature of FDI (FDI by sector) on capital accumulation. This study, therefore, aims to fill these gaps.

3. Methodology

3.1. Study area

The choice of countries and time period was driven by data availability (sector-specific FDI). Therefore, annual time series data on macroeconomic variables of interest from 2005 to 2018 were collected for 16 developing countries. Countries included in this study are Argentina, Armenia, Bangladesh, Colombia, Ecuador, El Salvador, Ghana, Guatemala, India, Indonesia, Malaysia, Mauritius, Mozambique, Pakistan, Rwanda, and Thailand.

3.2. The econometric model

Assessing either physical capital accumulation or human capital accumulation alone may not provide the full picture of the effect of FDI on capital accumulation, so it is more useful to consider both. Therefore, a first attempt was made to construct an econometric model of the aggregate effect of FDI on domestic physical capital, as shown in Equation (1), and then an attempt was made to model the effect at the sector level, as shown in Equation (2).

(1)

(1)

Based upon the literature review section, analyzing the aggregate effect of FDI on capital accumulation can be deceptive, therefore, decomposing it down into primary, secondary, and tertiary sectors makes it clearer and more logical. Because it is assumed that FDI quality varies across sectors. In order to estimate the effect of FDI at a disaggregate level on capital formation; we used Equation (2) as follows:

(2)

(2)

The study also attempted to construct an econometric model to examine the aggregate effect of FDI on human capital accumulation (Equation (3)) as well as the sector-specific effects of FDI on human capital (Equation (4)).

(3)

(3)

Breaking down FDI into different sectors allows us to better understand the effect of FDI on human capital, rather than simply estimating total FDI. For this purpose, the econometric model is set up (Equation (4)) as:

(4)

(4) Where, in equation (1) – (4), the subscript it stands for the ith country in year t, the effect of the explanatory variables on the dependent variable is denoted by βs (but β0 is intercept), while the error term is represented by ϵ.

The analysis and other parts of this study primarily focus on the effect of total FDI and sector-level FDI, the variables of interest in this study. Control variables such as PCGDP, DS, CPI, OT, EduExp, and MYS were included in the model in addition to interest variables. above clearly presents these variables, their definitions, measurements, expected signs, and data sources.

Table 1. List of variables, their definition, measurement, hypothesis, and sources of data.

3.3. Estimation techniques

The physical capital lag value is included because the initial capital is required to create new capital and should be accounted for in the FDI-physical capital regression. When the lag of the dependent variable is used as an explanatory variable, a dynamic panel data model (DPM) is generated, as shown in Equations (1) and (2). The DPD can be estimated correctly using the generalized method of moments (GMM) estimator, but not using the ordinary least-squares, fixed-effects, or random-effects estimator (Arellano and Bond Citation1991; Arellano and Bover Citation1995). GMM adequately addresses the endogeneity problem caused by including the lag values of the dependent variable, whereas other methods do not. Thus, we implemented the Arellano-Bover/Blundell-Bond GMM estimate approach, which is extensively utilized and well-suited to short time periods and vast cross-sectional units (Roodman Citation2009).

The probability of being in school at a given age is the same as the current enrollment rate for that age (UNESCO Citation2009). Lag values are unlikely to be significantly impacted by the enrollment rate from the previous year, so they may not need to be included in the FD-human capital regression. Thus, we used the random-effects estimation technique to estimate Equations (3) and (4) based on the Hausman specification test and the Breusch and Pagan Lagrangian Multiplier (LM) Test.

STATA (15.0) software is used for all statistical analyses, tests, and graphs.

4. Estimation results and discussion

4.1. Descrptive statistic analysis

shows the descriptive statistics of the variables used in the analysis. In this study, for example, the average per capita income is $4,001.42. Argentina ($11,024.34), Malaysia ($9,007.14), Mauritius ($8,365.52), and Colombia ($6,176.92) are countries with high GDP per capita, while Mozambique ($540.10), Rwanda ($612.12), Bangladesh ($935.98), and Pakistan ($1,034.96) have extremely low GDP per capita. Moreover, for the countries included in this study, the average share of physical capital accumulation in total GDP is 23.34 percent. India (33.59%), Indonesia (29.76%), and Ghana (29.38%) are countries with relatively high physical capital as a percentage of GDP. On the other side, Pakistan (14.90%), Guatemala (16.38%), and El Salvador (16.47%) are countries with low levels of accumulation of physical capital.

Table 2. Average Value of Different Variables across Different Countries (over the Period 2005–2018).

Meanwhile, the average domestic savings rate as a percentage of GDP is 20.93 percent. Domestic savings rates are relatively high in Malaysia (32.48%), India (34.32%), Indonesia (26.65%), and Ecuador (26.28%). Mozambique (11.7%), Guatemala (13.1%), Ghana (13.1%), El Salvador (13.4%), and Rwanda (13.2%) have relatively low savings rates.

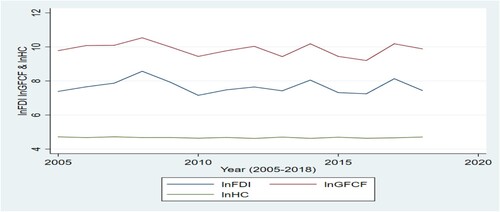

As shown in , the average logarithm of FDI for the countries investigated is 7.73. Rwanda (5.53), El Salvador (5.80), and Mauritius (6.08) have low scores, while India (9.90), Indonesia (9.37), and Colombia (9.32) have high scores. shows that both the human capital and physical capital graphs are positively correlated with total FDI. It is clear that the trends and shapes of the two graphs (FDI and physical capital) are almost identical from 2005 to 2018. This implies that FDI is essential for the augmentation of physical capital.

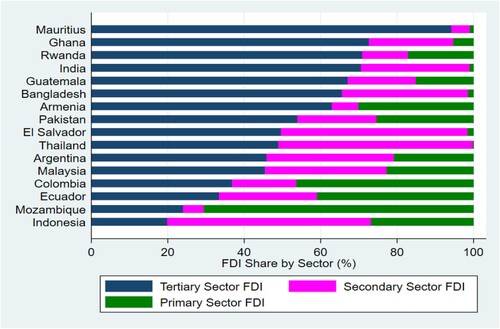

The overall structure of FDI differs from country to country. As shows, most of the FDI inflows to developing countries belong to the tertiary sector. However, FDI in the primary sector is dominant in Mozambique, Ecuador, and Colombia, whereas FDI in the secondary sector is dominant in Thailand.

Between 2005 and 2018, secondary school enrollment averaged 72.83 percent, with Argentina, Ecuador, Colombia, Armenia, Mauritius, and Thailand achieving over 90 percent. Enrollment rates are very low in Mozambique (27.14%), Pakistan (34.32%), and Rwanda (36.32%). Moreover, the average government expenditure in the education sector as a percentage of GDP in the investigated countries is 3.93%. Countries such as Argentina (5.05) have relatively high expenditure on education as a percentage of GDP. Meanwhile, Bangladesh (1.99%), Pakistan (2.49%), and Guatemala (2.99%) have made relatively less investments. On average, the countries included in this survey have a maximum attainment level of education of 7.41 grades. Bangladesh (11.29), Armenia (11.29), and Argentina (10.25) are countries with high percentages of relatively well-educated populations. Mozambique (2.91), Rwanda (3.90), and Pakistan (4.72), on the other side, are countries where the majority of the population is poorly educated.

The study shows an average economic openness of 71.29%. Mauritius, Thailand, Malaysia, and Mozambique are very open to international trade, with cross-border trade accounting for over 90% of their respective GDP. Pakistan, Argentina, and Rwanda, on the other side, are less open, with cross-border trade accounting for less than 45% of their respective GDP. Finally, the average perception of corruption in the countries included in this survey is 35.78%, with Mauritius (52.54%), Malaysia (48.89%), Rwanda (46.30%), and Ghana (43.37%) having the highest level. By contrast, Bangladesh (23.57%), Pakistan (26.50%), and Mozambique (28.87%) are countries where societies perceive low levels of corruption.

4.2. Regression analysis

First, this section tried to present the pre-regression and post-regression tests required for econometric analysis. Second, the key results of the one-step system Arellano-Bover/Blundell-Bond dynamic panel estimates of FDI on physical capital accumulation were presented. Third, an estimate of the random effects of FDI on human capital followed. Finally, the robustness of the econometric regression is evaluated and presented in this section.

4.2.1. Pre-and-Post regression tests

Before performing the Arellano-Bover/Blundell-Bond dynamic panel estimation, we tested for the presence of unit root for each variable.

shows that the p-values for all four tests are less than 5 percent. This indicates that all variables are ‘stationary at a level’ according to the ADF-Fisher method. Thus, we rejected the null hypothesis that all panels contain a unit root. Furthermore, the statistical robustness of the results depends on the validity of the Allerno-Bond test for zero autocorrelation in the case of first-order differential errors. The p-values for the Arellano-Bond test for zero autocorrelation with first-order differential error are 0.0165 for AR(1), 0.4823 for AR(2), 0.2905 for AR(3), and 0.7795 for AR(4). Except for AR(1), there is no evidence to reject the null hypothesis of no autocorrelation.

Table 3. Augmented Dickey-Fuller (ADF) Fisher Unit Root Test Output.

There were three options for running a regression of FDI on human capital: OLS, Fixed Effects (FE), and Random Effects (FE) estimation techniques. The Hausman specification test was used to select FE over RE, and then the Breusch and Pagan-Lagrange multiplier (LM) test was used to select RE over OLS. A non-significant p-value (p > 0.05) for the Hausman specification test indicates a preference for RE. Otherwise, FE is valid. In the LM test, negligible p-values favor RE over OLS (Greene Citation2002). According to , the Hausman test results show that RE is preferred over FE, as the Hausman test p-value is greater than 5 percent. The LM test was then performed, and the p-value for the LM test is less than 5 percent, indicating that RE is preferred over OLS.

Another issue that needs to be addressed is the need for diagnostic tests such as multicollinearity and heteroscedasticity before regression. Otherwise, you cannot be sure that your estimate is correct. Therefore, tests were performed, and the results of the multicollinearity and heteroscedasticity tests are shown in and .

Table 4. Multicollinearity and heteroskedasticity test output.

Table 5. Pairwise correlation.

Multicollinearity is not a problem if the variance inflation factor (VIF) value is less than 10 or the pairwise correlation is less than 0.8 (Gujarati Citation2003). However, heteroscedasticity becomes a problem when the p-value for the Breusch–Pagan/Cook–Weisberg test for heteroscedasticity is less than 0.05. and show that the data are not multicollinear but have heteroskedasticity, indicating that robust regression should be used. Thus, a robust regression was performed and the regression output is presented in .

Table 6. The Arellano-Bover/Blundell-Bond (GMM) and random effect model regression output.

4.2.2. The effect of FDI on physical capital

presents the empirical results of the decomposition of capital accumulation, showing that FDI has a significant positive effect on both physical and human capital accumulation at the aggregate level. Holding all other factors constant, on average, a one-percent incremental change in FDI inflows is associated with a 1.33 percent short-term increase in physical capital formation. In the long run, FDI inflows to developing countries increase physical capital accumulation by 2.31 percent (long-term effect = FDI coefficient divided by 1 minus DC lag coefficient). This means that FDI can be productive in both the short and long term, but its effect on capital accumulation in developing countries, in the long run, is highly significant.

also shows that FDI has heterogeneous effects across different sectors. Although FDI affects physical capital formation in developing countries differently in all three sectors, only FDI in the secondary sector has a statistically significant effect. All other things being equal, a one-percent increase in FDI inflows in the secondary sector would increase physical capital production by 1.24 percent in the short term. In the long run, it will increase domestic physical capital by 2.02 percent. This is because FDI into secondary sectors, especially manufacturing, has higher employment potential than FDI into other sectors. It also brings more income to workers and triggers a savings boom in developing countries. Compared to FDI in other sectors, FDI in the manufacturing sector also has the potential to build strong forward and reverse relationships with local businesses. Thus, the presence of FDI in manufacturing enhances the profitability of local firms by facilitating technology transfer, training, financing and connection of firms to global markets. Greenfield FDI is more likely to accumulate capital than FDI related to M&A (Harms and Méon Citation2018). As such, FDI in manufacturing is also often of the greenfield type, and is more likely to directly facilitate capital accumulation in developing countries than FDI in the services sector, which is usually M&A type.

In general, the findings of this study on the overall effect of FDI on physical capital are consistent with those of Slaughter (Citation2002); Apergis, Katrakilidis, and Tabakis Citation2006, Soltanpanah and Kariml (Citation2013), Rath and Bal (Citation2014), Ugwuegbe, Modebe, and Edith (Citation2014), Azam et al. (Citation2015), Zhuang (Citation2016), and Jude (Citation2018), who presented that MNEs promote capital accumulation in developing countries. Because FDI is an important source of foreign exchange, modern machinery and taxes (profits, wages, rent). It also contradicts the dependency theory that FDI leads to a decrease in domestic capital through the export of raw materials and minerals. Nor does it correspond to the empirical findings of Fahinde et al. (Citation2015), Ahmad et al. (Citation2018), and Budang and Hakim (Citation2020), who found that due to the superior technological and financial strength of MNEs, low domestic absorptive capacity and high incentives for natural resources lead to physical capital crowding out. At the sector level, the results of this study are consistent with those of Shah et al. (Citation2020) and Soe (Citation2020), who argue that FDI into the manufacturing sector has a positive and statistically significant effect on the accumulation of physical capital. It also contradicts the findings of Ahmed et al. (Citation2015), who argue that it has little effect on the physical capital in developing countries.

4.2.3. The effect of FDI on human capital

In developing countries, FDI generally has a positive and statistically significant effect on human capital. According to the results of the random effects panel estimates in , a one-percent increase in FDI in developing countries leads to a 2.38 percent increase in secondary school enrollment. FDI also plays an important role in strengthening human capital in developing countries, especially in the secondary sector. All else being equal, a one-percent increase in FDI into the second sector would increase human capital formation by 1.59 percent. Human capital is found to be negatively impacted by FDI in the primary sector and positively impacted by FDI in the service sector. However, those impacts are not statistically significant.

This is because the premium wages for skilled manufacturing workers are higher than for unskilled workers, making education more attractive. FDI into manufacturing is appreciated for its high technology, high level of productivity, and rapid growth rate (due to high-scale returns). All these contribute to sustainable economic growth and higher per capita income. This allows developing countries to invest more in education and reduce their economic hardships to keep their children in school. Moreover, FDI in manufacturing is known to employ many unemployed people, despite paying premium wages to skilled workers. They are also known to pay relatively high wages compared to local businesses, increasing household income beyond survival rates.

This allows workers to send their children to school instead of working to support the household. FDI in manufacturing is also generally a long-term investment compared to FDI in the primary and secondary sectors (Burger, Ianchovichina, and Rijkers Citation2016). FDI in the tertiary sector tends to be highly volatile, while FDI in the primary sector stays until the natural resources that drive it persist. FDI in manufacturing is therefore more likely to engage in corporate social responsibility activities such as school building and equipment relief initiatives as they seek a stable environment and positive relationships with the surrounding society.

The results of this study are consistent with those of Neumayer (Citation2005), Wang (Citation2011), Doytch, Thelen, and Mendoza (Citation2014), Sun and He (Citation2014), Zhuang (Citation2016), and Bello, Othman, and Khairri Shariffuddin (Citation2017). They argued that FDI has beneficial and statistically significant effects on human capital, as it can support the utilization of skilled labor and economic growth. It is also inconsistent with the results of Liu et al. (Citation2014), Mughal and Vechiu (Citation2015), Fahinde et al. (Citation2015), Saucedo, Ozuna, and Zamora (Citation2020), Ibarra-Olivo (Citation2021), and Wang and Zhuang (Citation2021) argue that wage increases create strong incentives for unskilled workers to delay or drop out of school. MNEs are primarily interested in exploiting the low cost of unskilled labor, which is abundant in developing countries. They have therefore provided a great deal of employment to all unskilled workers, especially women with previously inaccessible formal jobs.

4.3. Robustness checks

We experimented with various models of the capital accumulation equation. To begin, it would be reassuring to do a jackknife exercise to see how the estimates change as each country or control variable is dropped in turn. For example, as shown in , we removed Thailand from model (5), which shows the overall effect of FDI on physical capital accumulation, and Argentina from model (7), which shows the effect of FDI on human capital accumulation. Aside from a slight magnitude change, no change in significance or sign of estimator including our interesting variable, FDI, was observed.

Table 7. Sensitive analysis.

Similarly, some tests are performed to determine how sensitive the results are to the list of control variables. If the mean year of schooling is dropped, the results have the same sign and significance (with the original regression) as shown in under model (6), which shows the effect of FDI on physical capital accumulation. If the openness of the economy is removed, the sign and significance of variable coefficients in the model (8) in are similar to the results in the model (3) in . Even when no control variables are included, the coefficient of lnFDI in the physical capital equation is 0.6827 with a robust standard error of 0.0286 and 4.1029 with a standard error of 1.4427 in the human capital accumulation equation, both of which are statistically significant. This suggests that our reported estimate is trustworthy.

5. Conclusion and recommendations

The purpose of this study is to investigate the effect of FDI on capital accumulation in developing countries. The analysis used data from 16 developing countries over 14 years, from 2005 to 2018. We used the Arellano-Bover/Blundell-Bond dynamic panel to explore the effect of FDI on physical capital accumulation. Variables such as economic openness, financial development, and institutional status (proxied by the state of corruption) were used as control variables. The effect of FDI on human capital was also examined using a random effects model. The following important conclusions were drawn from the regression results.

First, FDI facilitates the creation of physical and human capital, thereby helping to facilitate structural change in developing countries. Second, not only the level of the FDI inflows but also the sector in which FDI is invested plays an important role in capital accumulation in developing countries. Therefore, FDI into manufacturing is the most important type of FDI to promote capital accumulation in developing countries compared to FDI into primary and tertiary sectors. Third, time is an important consideration, as FDI has more impact in the long term than in the short term. Finally, FDI in developing countries contributes more to human capital than to physical capital.

Developing countries can therefore benefit more from paying attention to both the sectoral composition and the overall volume of FDI inflows. It is very important to pay particular attention to the accumulation of FDI in manufacturing. By creating well-structured advertising agencies, developing countries can receive more FDI. Moreover, enhancing investment in education sector and improving institutional quality, such as opening up cross-border trade, is critical to reaping the full benefits of FDI. Offering special incentives such as tax exemptions and low-rent land to manufacturing MNEs in developing countries is essential to attract more capital. Capital formation, especially human capital, could be improved if developing countries directly restricted the use of child labor by MNEs or by domestic enterprises linked through vertical ties to MNEs..

Authors’ details

Ezo Emako (PhD), Lecturer & Researcher, Arba Minch University, Ethiopia.

Seid Nuru (PhD, Associate Professor of Economics), Lecturer & Researcher, Arba Minch University, Ethiopia.

Mesfin Menza (PhD), Lecturer & Researcher, and Dean of CBE, Arba Minch University, Ethiopia.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Abubakar, A., S. H. Kassim, and M. B. Yusoff. 2015. “Financial Development, Human Capital Accumulation and Economic Growth: Emprical Evidence from the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS).” Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences 172: 96–103. doi:10.1016/j.sbspro.2015.01.341.

- Agosin, M. R., and R. Mayer. 2000. Foreign Direct Investment in Developing Countries: Does It Crowd in Domestic Investment? UNCTAD/OSG/DP/146 Working Paper, 1–20.

- Ahmad, N., M. Hdia, H. Li, J. Wang, and X. Tian. 2018. “Foreign Direct Investment, Domestic Investment and Economic Growth in China: Does Foreign Investment Crowd-in or Crowd-out Domestic Investment.” Economics Bulletin 38 (3): 1279–1291.

- Ahmed, K. T., G. M. Ghani, N. Mohamad, and A. M. Derus. 2015. “Does Inward FDI Crowd-out Domestic Investment? Evidence from Uganda.” Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences 172: 419–426. doi:10.1016/j.sbspro.2015.01.395.

- Al-Sadig, A. 2012. “The Effects of Foreign Direct Investment on Private Domestic Investment: Evidence from Developing Countries.” Empirical Economics 44 (3): 1267–1275. doi:10.1007/s00181-012-0569-1.

- Apergis, N., C. P. Katrakilidis, and N. M. Tabakis. 2006. “Dynamic Linkages Between FDI Inflows and Domestic Investment: A Panel Cointegration Approach.” Atlantic Economic Journal 34: 385–394. doi:10.1007/s11293-006-9026-x.

- Arellano, M., and S. Bond. 1991. “Some Tests of Specification for Panel Data: Monte Carlo Evidence and an Application to Employment Equations.” Review of Economic Studies 58: 277–297. doi:10.2307/2297968.

- Arellano, M., and O. Bover. 1995. “Another Look at the Instrumental Variable Estimation of Error-Components Models.” Journal of Econometrics 68: 29–51. doi:10.1016/0304-4076(94)01642-D.

- Atkin, D. 2016. “Endogenous Skill Acquisition and Export Manufacturing in Mexico.” American Economic Review 106 (8): 2046–2085. doi:10.1257/aer.20120901.

- Azam, M., S. Khan, Z. B. Zainal, N. Karuppiah, and F. Khan. 2015. “Foreign Direct Investment and Human Capital: Evidence from Developing Countries.” Investment Management and Financial Innovations 12 (3-1): 155–162.

- Basu, K., and P. H. Van. 1998. “American Economic Association The Economics of Child Labor : Reply Author (s): Kaushik Basu and Pham Hoang Van Source : The American Economic Review, Vol . 89, No . 5 (Dec ., 1999), pp . 1386-1388 Published by : American Economic Association Stable.” The American Economic Review 88 (3): 416. https://www.jstor.org/stable/116842.

- Becker, G. S. 1962. “Investment in Human Capital: A Theoeretical Analysis.” Journal of Political Economy 70 (5-Part2): 9–49. doi:10.1086/258724.

- Beer, L. 1999. “Income Inequality and Transnational Corporate Penetration.” Journal of World-Systems Research 5: 1–25. doi:10.5195/jwsr.1999.144.

- Bello, I., M. F. Othman, and M. D. Khairri Shariffuddin. 2017. “Multinational Corporations and Nigeria’s Education Development: An International Development Perspectives.” International Journal of Management Research & Review 7 (6): 637–647. www.ijmrr.com.

- Blomstrom, M., and A. Kokko. 2003. “Human Capital and Inward FDI.” European Institute of Japanese Studies Working Paper No. 167. https://swopec.hhs.se/eijswp/papers/eijswp0167.pdf.

- Budang, N. A., and T. A. Hakim. 2020. “Does Foreign Direct Investment Crowd in or Crowd Domestic Investment? Evidence from Panel Cointegration Analysis.” Academic Research in Economics and Management Sciences 9 (1): 50–65.

- Burger, M., E. Ianchovichina, and B. Rijkers. 2016. “Risky Business: Political Instability and Sectoral Greenfield Foreign Direct Investment in the Arabworld.” World Bank Economic Review 30 (2): 306–331. doi:10.1093/wber/lhv030.

- Chen, G. S., Y. Yao, and J. Malizard. 2017. “Does Foreign Direct Investment Crowd in or Crowd out Private Domestic Investment in China? The Effect of Entry Mode.” Economic Modelling 61: 409–419. doi:10.1016/j.econmod.2016.11.005.

- Demena, B. A., and P. G. van-Bergeijk. 2019. “Observing FDI Spillover Transmission Channels: Evidence from Firms in Uganda.” Third World Quarterly 40 (9): 1708–1729. doi:10.1080/01436597.2019.1596022.

- Djokoto, J. G. 2021. “Foreign Direct Investment into Agriculture: Does It Crowd-Out Domestic Investment?” Agrekon 60 (2): 176–191. doi:10.1080/03031853.2021.1920437.

- Doytch, N., N. Thelen, and R. U. Mendoza. 2014. “The Impact of FDI on Child Labor: Insights from an Empirical Analysis of Sectoral FDI Data and Case Studies.” Children and Youth Services Review 47 (P2): 157–167. doi:10.1016/j.childyouth.2014.09.008.

- Eregha, P. B. 2012. “The Dynamic Linkages between Foreign Direct Investment and Domestic Investment in ECOWAS Countries: A Panel Cointegration Analysis.” Africa Development Review 24 (3): 208–220. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8268.2012.00317.x.

- Fahinde, C., A. Abodohoui, M. Mohiuddin, and Z. Su. 2015. “External Financial Inflows and Domestic Investment in the Economies of WAEMU: Crowding-Out Versus Crowding-in Effects.” The Journal of Developing Areas 49 (3): 229–248. doi:10.1353/jda.2015.0161.

- Frank, A. G. 1978. “The Development of Underdevelopment or Underdevelopment of Development in China.” Modern China 4 (3): 341–350. doi:10.1177/009770047800400304.

- Goyal, A. 2006. “Corporate Social Responsibility as a Signalling Device for Foreign Direct Investment.” International Journal of the Economics of Business 13 (1): 145–163. doi:10.1080/13571510500520077.

- Greene, W. H. 2002. Econometrics Analysis. New Jersey: Prentice Hall.

- Grossman, G. M., and E. Helpman. 1991. “Quality Ladders in the Theory of Growth.” Review of Economic Studies 58: 43–61. doi:10.2307/2298044.

- Gujarati, D. N. 2003. Basic Econometrics. West Point: McGraw-Hill Higher Ed.

- Harms, P., and P. G. Méon. 2018. “Good and Useless FDI: The Growth Effects of Greenfield Investment and Mergers and Acquisitions.” Review of International Economics 26 (1): 37–59. doi:10.1111/roie.12302.

- Ibarra-Olivo, J. E. 2021. “Foreign Direct Investment and Youth Educational Outcomes in Mexican Municipalities.” Economics of Education Review 82 (May 2020): 102123. doi:10.1016/j.econedurev.2021.102123.

- Jude, C. 2018. “Does FDI Crowd out Domestic Investment in Transition Countries.” Economics of Transition and Institutional Change 27 (1): 163–200. doi:10.1111/ecot.12184.

- Kaulihowa, T., and C. Adjasi. 2019. “Non-linearity of FDI and Human Capital Development in Africa.” Transnational Corporations Review 11 (2): 133–142. doi:10.1080/19186444.2019.1635734.

- Kechagia, Polyxeni, and T. Metaxas. 2023. “Capital Inflows and Working Children in Developing Countries : An Empirical Approach.” Sustainability 15 (7): 6240. doi:10.3390/su15076240.

- Lean, H. H., and B. W. Tan. 2011. “Linkages between Foreign Direct Investment, Domestic Investment and Economic Growth in Malaysia.” Journal of Economic Cooperation and Development 32 (4): 75–96.

- Liu, X., Y. Luo, Z. Qiu, and R. Zhang. 2014. “FDI and Economic Development: Evidence from China's Regional Growth.” Emerging Markets Finance and Trade 50 (sup6): 87–106. doi:10.1080/1540496X.2014.1013852.

- Loureiro, P., F. Rugitsky, and A. Saad-Filho. 2020. “Celso Furtado and the Myth of Economic Development: Rethinking Development from Exile.” Review of Political Economy 33 (1): 28–43. doi:10.1080/09538259.2020.1827546.

- Lucas, R. E. 1988. “On the Mechanics of Economic Development.” Journal of Monetary Economics 22: 3–42. doi:10.1016/0304-3932(88)90168-7.

- Misun, J., and V. Tomsik. 2002. “Does Foreign Direct Investment Crowd in or Crowd out Domestic Investment?” Eastern European Economics 40 (2): 38–56. doi:10.1080/00128775.2002.11041015.

- Mughal, M., and N. Vechiu. 2015. “Foreign Direct Investment and Education in Developing Countries.” Revue Economique 2 (66): 369–400. doi:10.3917/reco.pr2.0038.

- Namkoong, Y. 1999. “Dependency Theory: Concepts, Classifications, and Criticisms.” International Area Review 2 (1): 121–150. doi:10.1177/223386599900200106.

- Narula, R. 2019. “Enforcing Higher Labor Standards Within Developing Country Value Chains: Consequences for MNEs and Informal Actors in a Dual Economy.” Journal of International Business Studies 50 (9): 1622–1635. doi:10.1057/s41267-019-00265-1.

- Neumayer, E. 2005. “Trade Openness, Foreign Direct Investment and Child Labor.” World Development 33 (1): 43–63. doi:10.1016/j.worlddev.2004.06.014.

- Nguyen, T. Q., L. Thi, K. Tran, P. L. Pham, and T. D. Nguyen. 2020. “Impacts of Foreign Direct Investment Inflows on Employment in Vietnam.” Institutions and Economies 12 (1): 37–62.

- Nyiwul, L., and N. P. Koirala. 2022. “Role of Foreign Direct Investments in Agriculture, Forestry and Fishing in Developing Countries.” Future Business Journal 8 (1), doi:10.1186/s43093-022-00164-2.

- Ogbuagu, Ifeoma Gracious, and V. C. Onyeike. 2021. “Multinational Companies Support for Students Through Corporate Social Responsibility In Community Secondary Schools In Rivers State, Nigeria.” Sokoto Educational Review 20 (1&2): 233–249. doi:10.35386/ser.v20i1&2.448.

- Polloni-Silva, E., H. F. Moralles, D. A. N. Rebelatto, and D. Hartmann. 2021. “Are Foreign Companies a Blessing or a Curse for Local Development in Brazil? It Depends on the Home Country or Host Region's Institutions.” Growth and Change 52 (2): 933–962. doi:10.1111/grow.12484.

- Rath, B. N., and D. P. Bal. 2014. “Do FDI and Public Investment Crowd-in or Crowd-out Private Domestic Investment in India.” The Journal of Development Areas 48 (3): 269–284. doi:10.1353/jda.2014.0048.

- Romer, P. M. 1990. “Endoegenous Technological Change.” The Journal of Political Economy 98 (5): S71–S102. doi:10.1086/261725.

- Roodman, D. 2009. “How to do xtabond2: An Introduction to Difference and System GMM in STATA.” The Stata Journal 9 (1): 86–136. doi:10.1177/1536867X0900900106.

- Santos, T. D. 1970. “The Structure of Dependence.” The American Economic Review 60 (2): 231–236.

- Saucedo, Jr., E., T. Ozuna, and H. Zamora. 2020. “The Effect of FDI on low and High - Skilled Employment and Wages in Mexico : A Study for the Manufacture and Service Sectors.” Journal for Labour Market Research 54 (9): 1–15. doi:10.1186/s12651-020-00273-x.

- Shah, S. H., H. Hasnat, M. H. Ahmad, and J. J. Li. 2020. “Sectoral FDI Inflows and Domestic Investments in Pakistan.” Journal of Policy Modeling 42 (1): 96–111. doi:10.1016/j.jpolmod.2019.05.007.

- Slaughter, M. J. 2002. Skill Upgrading in Developing Countries: Has Inward Foreign Direct Investment Played A Role? https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org.

- Soe, T. M. 2020. “Economic Effects of Inward Foreign Direct Investment in Myanmar.” Bulletin of Applied Economics 7 (2): 175–190. doi:10.47260/bae/7214.

- Solow, R. M. 1956. “A Contribution to the Theory of Economic Growth.” Quarterly Journal of Economics 70: 65–94. doi:10.2307/1884513.

- Soltanpanah, H., and M. S. Kariml. 2013. “Accumulation of Human Capital and Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) Inflows in ASEAN-3 Countries (Malaysia, Thailand, Indonesia).” African Journal of Business Management 7 (17): 1599–1605. doi:10.5897/AJBM11.1681.

- Sucubasi, B., B. Trenovski, B. Imeri, and G. Merdzan. 2020. “The Effects of FDI on Domestic Investment in Western Balkans.” Globalization and Its Socio-Economic Consequences 92: 1–14. doi:10.1051/shsconf/20219207059.

- Sun, M., and Q. He. 2014. “Does Foreign Direct Investment Promote Human Capital Accumulation? the Role of Gradual Financial Liberalization.” Emerging Markets Finance and Trade 50 (4): 163–175. doi:10.2753/REE1540-496X500410.

- Sunkel, O., and C. Girvan. 1973. “Dependence and Underdevelopment in New World and the Old.” Social and Economic Studies 22 (1): 132–176.

- Ugwuegbe, S. U., N. J. Modebe, and O. Edith. 2014. “The Impact of Foreign Direct Investment on Capital Formation in Nigeria: A Co-Integration Approach.” International Journal of Economics, Finance and Management Sciences 2 (2): 188–196. doi:10.11648/j.ijefm.20140202.21.

- UNCTAD (United Nations Conference on Trade and Development). 2019. World Investment Report 2019. Geneva: United Nations.

- UNESCO. 2009. Education Indicators Technical Guidelines. Paris: UNESCO Institute for Statistics. https://uis.unesco.org/sites/default/files/documents/education-indicators-technical-guidelines-en_0.pdf.

- United Nations Conferences on Trade and Development. 2021. UNCTAD: Annex (table 01: FDI inflows, by region and economy, 1990-2020. Retrieved from https://worldinvestmentreport.unctad.org.

- Wang, M. 2011. “FDI and Human Capital in the USA : Is FDI in Different Industries Created Equal ? FDI and Human Capital in the USA : Is FDI in Different Industries Created Equal ?” Applied Economics Letters 18: 37–41. doi:10.1080/13504850903442962.

- Wang, M., and H. Zhuang. 2021. “FDI and Educational Outcomes in Developing Countries.” In Empirical Economics (Vol. 61, Issue 6). Springer Berlin Heidelberg. doi:10.1007/s00181-021-02015-5.

- Weeks, J. 1981. “The Differences Between Materialist Theory and Dependency Theory and Why They Matter.” Latin American Perspectives 8 (3–4): 118–123. doi:10.1177/0094582X8100800307.

- Willem, D. 2002. Government Policies for Inward Foreign Direct Investment in Developing Countries : Implications for Human Capital and Income Inequality. In Working Paper No.193. https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/docserver/248666671311.pdf?expires=1681315956&id=id&accname=guest&checksum=DBA0A0C9A75CD58F905C180FDF2C4452.

- Zhuang, H. 2016. “The Effect of Foreign Direct Investment on Human Capital Development in East Asia.” Journal of the Asia Pacific Economy 22 (2): 195–211. doi:10.1080/13547860.2016.1240321.