ABSTRACT

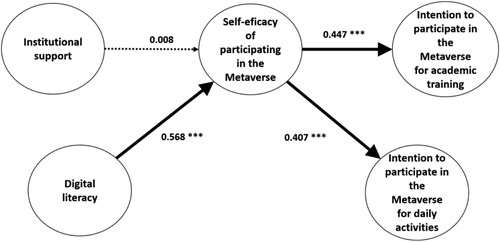

The pandemic has led to a surge in virtual training, prompting the need to assess whether people are open to using more advanced technologies, like the metaverse, for academic training. This research aims to identify the factors influencing people’s intention to receive academic training through the metaverse. The study collected responses from 251 individuals in Colombia through an online survey, and the data was analyzed using the partial least squares structural equation modeling technique. The results showed that digital literacy significantly positively affects self-efficacy to participate in the metaverse (0.568; p < 0.001). Furthermore, self-efficacy to participate in the metaverse was found to have a positive impact on people’s intention to participate in the metaverse for academic training courses (0.447; p < 0.001) as well as for daily activities (0.407; p < 0.001). The findings suggest universities can use the metaverse to create globally competitive short and long courses. However, a larger sample size is required to ensure the reliability of the results. Additionally, improving digital literacy is crucial for engaging more users of the metaverse, which can help reduce training costs, ensure consistent learning, and foster collaboration among teams.

1. Introduction

The widespread use of the Internet has made it easier for people to access increasingly immersive offers such as the metaverse. The term ‘metaverse’ was first coined by Neal Stephenson in 1992. It is essentially a virtual environment on a computer based on various concepts (Stephenson Citation1992). The metaverse has been described as a virtual space relevant for businesses and universities to understand the willingness of people to participate in metaverse-related activities, including training and daily routines (Alvarez-Risco et al. Citation2022), which can help generate personalized offers (Alvarez-Risco et al. Citation2021). During the pandemic, internet usage surged with varying impacts, causing people to adapt their lifestyles. Even though people are no longer isolated, the new habits generated by internet browsing remain, creating an opportunity for companies to offer software and computer systems such as the metaverse. The metaverse concept has gained increasing attention in digital technology in recent years.

The term ‘metaverse’ refers to a virtual space that can be accessed through the internet and is shared among users. It is a highly immersive and interactive environment where people can interact with each other, create, and consume content in ways that are not possible in the real world. The metaverse can revolutionize how we live, work and interact while supporting a sustainable future. With its unique capabilities, it can be used to promote healthcare services, such as virtual reality experience and therapy, support communities for fatal diseases, medical training, and research. By leveraging the metaverse, providing greater access and diversification of healthcare services may be feasible, improving overall quality of life.

The pandemic caused a profound change in education (Lin et al. Citation2022; Singh, Malhotra, and Sharma Citation2022). Tlili et al. (Citation2022) found that education quickly moved from in-person to virtual due to mobility restrictions. Now, it has become a hybrid approach, as some universities have realized its benefits for students who have already successfully adapted to it.

Cell phones and computers are widely used in education as they serve as the primary means of connection to classes (Tkachuk et al. Citation2021). The metaverse offers an advanced mode of access and is more attractive to students and professionals in real-world training. Also, online retailers are perfecting immersive buying offers (Gadalla, Keeling, and Abosag Citation2013) through more complete tools (Ondrejka Citation2004). Users often search for new digital experiences, looking for more interaction and intense experiences, so they increasingly seek to stimulate more senses.

It is necessary to gather information from potential participants to build the metaverse. The records of daily activities of people are the primary source of this information, which is why internet users need to participate in various social networks (Liu, Rehman, and Wu Citation2021). By doing so, user preferences can be modeled, which is crucial in providing personalized products. Constant participation in platforms like Twitter (Yen, Huang, and Chen Citation2018), Facebook (Bogaert et al. Citation2021), Instagram (Georgakopoulou, Iversen, and Stage Citation2020), and TikTok (Wang and Fu Citation2020) can facilitate this process.

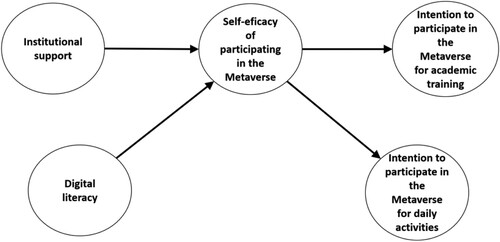

This research aims to identify the factors that can predict one’s interest in participating in the metaverse for academic training or daily activities. A model is established based on social cognitive theory that confirms the influence of various factors proposed in the study to achieve this. On the one hand, the research considers institutional support for the user, which is linked to whether the educational or professional institution promotes and supports learning and participation in digital environments (Diamantidis and Chatzoglou Citation2019). Digital literacy, which refers to the skills required to carry out daily activities using technology (Farrell, Newman, and Corbel Citation2021), is another important factor that several factors, like training from primary school to older ages, can influence. Self-efficacy, or the behavioral intention to act on one is knowledge and intentions, is also considered.

The study measures digital literacy through different items focused on the perception of proficiency by users in software such as Word, Excel, and social media platforms like TikTok, Instagram and Facebook. Additionally, it evaluates the ability of users to manage emails, advance levels in video games, and the use of Enterprise Resource Management (ERP) like SAP or Oracle. This research is beneficial for explaining the intention to participate in the metaverse among Colombian citizens for both learning and regular activities. Understanding the factors influencing one’s intention can help convert those interested in traditional training to training in the metaverse environment.

More and more institutions are showing interest in participating in the metaverse. To achieve this, they focus on infrastructure and networking implementation. One crucial element that is being developed in-depth is the human interface. This interface ensures that the avatars representing participants accurately reflect their gestures and physical characteristics. Decentralization is another critical factor that is developing with spatial computing in the metaverse, which involves mapping the real-world position of users with Global Positioning System (GPS) to create three-dimensional elements of the metaverse. By testing this model, researchers can better understand the expectations of current internet users when it comes to participating in the metaverse and confirm whether their daily lives can be integrated into it, including academic training activities.

2. Literature review

The metaverse, as such, has very little time, but it already has some evidence that shows its progress, acceptance, challenges and opportunities. In this way, there is evidence that the metaverse generates a different experience in video games and education, both combinable for a disruptive offer for the youngest (Chen Citation2022).

The metaverse creates a virtual society that coexists with the real world, generating meta-companies and meta-cities that exist in both realms. In other words, we are talking about virtual organizations that go hand in hand with their actual peers in terms of human, material and scenario elements. This parallel world allows computational predictions that work for the real world of businesses and cities. Several studies have evaluated the use of metaverse in various fields, including anatomy learning (Iwanaga et al. Citation2023), artificial intelligence (Huynh-The et al. Citation2023), education (Jauhiainen, Krohn, and Junnila Citation2023), and audience satisfaction (undisclosed). However, there is limited research on the intention to use metaverse in professional training in Latin America.

Likewise, it is necessary to know what role the participant’s institutional support plays in explaining the self-efficacy they may have. On the other hand, knowing whether digital literacy is an important variable in explaining self-efficacy is very important. These variables need to be evaluated simultaneously to determine the effects between them in a multivariate model. Unlike them, the present study directly evaluates the potential information of users on the intention to use metaverse in training and daily activities.

3. Theoretical framework and hypothesis development

3.1. The social cognitive theory (SCT)

SCT has achieved different evolutions over time, but concretely, it proposes that learning in people occurs within an interaction in society, seen as a dynamic process of the individual, his behavior and all the aspects that make up his environment. Likewise, SCT describes how people regulate their behavior to finally achieve a specific goal-oriented behavior that can be continued in the future (de la Fuente, Kauffman, and Boruchovitch Citation2023). We utilized the SCT, which mentions that the actions within the control of a person can increase self-efficacy, a predictor of behavioral intention. In this research, self-efficacy is relevant because it involves the confidence of an individual to perform a task (de la Fuente, Kauffman, and Boruchovitch Citation2023). Self-efficacy is a fundamental concept in Social Learning Theory.

As described by Bandura, self-efficacy refers to a personal belief in their ability to perform a task or achieve a goal. It is influenced by their previous experiences, observation of others, and interpretation of feedback. Self-efficacy plays a crucial role in learning new behaviors and skills since it affects an individual’s motivation, effort, and persistence. Motivation is affected by self-efficacy as it influences the goal-setting process. Individuals with high self-efficacy are more likely to set challenging goals and work towards achieving them. They are also more likely to persevere when faced with obstacles, setbacks, and failures. Conversely, people with low self-efficacy tend to set easier goals or avoid challenging tasks entirely.

Self-efficacy also affects effort, influencing the energy and resources people invest in learning new behaviors and skills. People with high self-efficacy tend to invest more time, energy, and resources in learning new behaviors and skills. They are also more likely to engage in activities facilitating the learning process, such as seeking feedback, asking questions, and practicing.

Conversely, individuals with low self-efficacy are more likely to avoid activities that require effort or investment. Then, self-efficacy also affects persistence, as it influences the degree to which people continue to pursue their goals and learn new behaviors and skills over time. People with a high level of self-efficacy are more likely to persist in the face of setbacks, failures, and challenges. They are also more likely to bounce back from failures and continue to learn from their experiences. Conversely, individuals with low self-efficacy are more likely to give up or disengage from learning activities when faced with challenges or setbacks. One crucial issue is that the authors believe self-efficacy affects digital literacy. Greater digital literacy can improve self-efficacy and encourage metaverse use. However, many individuals still only use basic digital tools. Improving digital literacy is crucial for positively impacting self-efficacy.

3.2. Hypothesis development

The conceptualization of the study variables and the hypotheses based on the theoretical model to be tested are presented below.

3.3. Intention of participation in the metaverse for academic training (IPMVAT) and daily activities (IPMVDA)

The objective is to identify the variables that affect self-efficacy and IPMV, which help to understand how people perceive taking training using the metaverse, which integrates the physical and virtual worlds. Although the metaverse is still being developed and evolving, it is important to gather information about the expectations of people participating. This data can help us plan academic programs based on the metaverse for future students. Previous studies have shown that having digital literacy can predict the intention to participate in online environments. In addition, self-efficacy can predict the intention to use technological devices and social media based on SCT. With this evidence, we can create programs that meet the current and future training expectations.

3.4. Institutional support (IS)

Individuals who are part of an institution receive different types of influence. The variable presented here involves the institutional support provided by these organizations, mainly universities or companies, to their members regarding access and training in technology (Tondeur et al. Citation2018). Universities and companies play a huge role in people’s lives, as they spend a considerable amount of time there. Thus, guiding and supporting members (students or workers) to improve digital resources is crucial for academic and professional growth (Stephan, Uhlaner, and Stride Citation2015).

Hypothesis 1. IS has a positive and significant effect on the SEPMV.

3.5. Digital literacy (DL)

This construct describes a person’s ability to successfully use various technological tools, especially computers, daily (Hasse Citation2017). Having digital literacy means effectively using, understanding, and navigating digital technologies and information. It involves a wide range of skills, knowledge, and competencies that enable people to succeed in a world increasingly driven by technology. Digital literacy is crucial in personal and professional settings, as it equips individuals to access, evaluate, create, and communicate using digital tools and platforms. Digital literacy is crucial today. Institutions should provide training to integrate it into metaverse activities. Greater digital literacy is expected to have an effect on the SEPMV since having more knowledge and skills in the digital context generates more confidence, and therefore, the SEPMV increases.

Hypothesis 2. DL has a positive and significant effect on SEPMV

3.6. Self-efficacy of participating in the metaverse (SEPMV)

The self-efficacy described in SCT is the belief that a person has concerning their ability to perform any task and incorporate specific behaviors into their daily actions (Bandura Citation1992). Self-efficacy is expected to mediate between IS, DL and IPMV.

Hypothesis 3. SEPMV has a positive and significant effect on IPMVAT

Hypothesis 4. SEPMV has a positive and significant effect on IPMVDA

4. Mediation

Our study evaluated the mediator role of the SEPMV between different variables of the research model. We wish to test whether self-efficacy would mediate between institutional support and the intention to use metaverse. It could be expected that this institutional support could contribute to making this intention materialize and be maintained over time. The mediation may be stronger for professional training than for daily activities. On the other hand, the mediation of self-efficacy for digital literacy could be the same for both uses of the metaverse.

Hypothesis 5. SEPMV has a significant mediating role between IS and IPMVAT

Hypothesis 6. SEPMV has a significant mediating role between DL and IPMVAT

Hypothesis 7. SEPMV has a significant mediating role between IS and IPMVDA

Hypothesis 8. SEPMV has a significant mediating role between DL and IPMVDA

5. Material and methods

This section presents the research design and sample and details how the instrument is composed. Subsequently, the analysis to be carried out with the data collected is detailed.

5.1. Design

This correlational study analyzes the effect and statistical significance of variables that explain IPM for academic training purposes and daily activities.

5.2. Instrument and collection of data

A 5-point Likert scale questionnaire was built and used in this study. We used the items described in the literature for the model proposal. Items considered to evaluate the variables in the model were obtained from Alvarez-Risco et al. (Citation2021) (IS), Cruz-Torres, Alvarez-Risco, and Del-Aguila-Arcentales (Citation2021) (DL), previous studies (Alvarez-Risco et al. Citation2021) (self-efficacy), and the authors (IPMV). The authors developed four items for IPMV for academic training; they also elaborated eight items to measure IPMV for daily activities. Education experts validated these items.

We utilized a non-probabilistic sampling process to collect data between September and October 2022. After the data collection process, we received 267 answers, and after cleaning, we obtained 251 valid surveys from participants in Colombia over 18 years old. Colombia was chosen due to the significant progress of the metaverse in the country compared to others where potential participants are unfamiliar with the subject matter. We collected the data through online distribution via emails and WhatsApp using the snowball technique. Snowball sampling is a research technique where participants refer others who meet the study criteria. This creates a ‘snowball’ effect, making it useful for studying hard-to-reach populations. All steps followed the ethical standards of the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

5.3. Sample

The participants had to agree to the 3 questions posed at the beginning of the questionnaire:

I have been informed about the purpose of this research.

I know that participating in the research is voluntary

I have freely decided to participate in the present study

5.4. Data analysis

The second-generation analysis technique partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) was used for data analysis, which allows multivariate studies; for this purpose, the SMART PLS 3.3.3 software was used (Becker et al. Citation2023). Reliability and validity, as well as bootstrapping, were measured by 5000 resamples; the mediating effect of self-efficacy was also evaluated.

6. Results

This section presents the results of the present study, showing the reliability tests, convergent and discriminant validity, bootstrapping to verify the statistical significance of the relationships between variables and, finally, the indirect effects to verify the mediating effects of the model tested.

6.1. Demographic data

The participants were Colombian consumers. The age of the participants was 18 years and older. The year mean is 33.57 (SD = 11.8). About the sex of the participants, 122 (48.6) were females and 129 (51.4) were males. About occupation, 202 (80.47) are work, 31 (12.35) are study, and 18 (7.17) are study and work.

6.2. Reliability of the questionnaire

The scales of the questionnaire evaluated the reliability using an internal consistency analysis. shows that the variables had reliability coefficients (Alpha of Cronbach) of more than 0.7. The composite reliability of the questionnaire was confirmed.

Table 1. Construct validity using PLS-SEM.

6.3. Validity using SEM-PLS

By calculating the average variance extracted (AVE), the convergent validity was measured to be 0.5 or more. Then, using the Fornell-Larcker criterion (Fornell and Larcker Citation1981), discriminant validity was assessed. shows the fulfillment of this criterion for all the study variables, evidencing the discriminant validity of the questionnaire.

Table 2. Discriminant validity.

6.4. Evaluation of nonlinear effects

The test proposed by Svensson et al. (Citation2018) evaluated potential nonlinearities in the structural model relationships. It used Ramsey Regression Equation Specification Error Test (RESET), which was proposed by Ramsey (Citation1969). The results of bootstrapping with 10000 samples and using no sign changes indicate that neither of the nonlinear effects is significant (). The linear effects model is robust.

Table 3. Evaluation of nonlinear effects.

shows R Square and R Square Adjusted to evaluate the model’s goodness-of-fit. shows that the results have the correct goodness of fit. By the goodness of fit, we should understand the degree of coupling between the original data and the theoretical values obtained from the regression.

Table 4. Structural model evaluation.

6.5. Evaluation of structural model

To evaluate the structural model, bootstrapping, according to Streukens and Leroi-Werelds (Citation2016), is an analysis technique to verify if the path coefficients are statistically significant. shows the evaluation of each hypothesis. Applied 5000 resamples with p-value < 0.05. Hypothesis 1 was rejected because the p-value was above 0.05, the limiting value. Hypotheses 2, 3 and 4 were accepted because the values in all 3 cases were 0.000, lower than the limit value mentioned above. The variance inflation factor (VIF) values verify the absence of multicollinearity.

Table 5. Direct effects.

details the specific indirect effects of the model. Hypotheses 5 and 8 were not supported because the p-value was more than 0.05. Also, hypotheses 6 and 7 were supported. In other words, SEPMV is a mediator between DL and IPMVAT and between DL and IPMVDA. Also, SEPMV was demonstrated to mediate between IS and IPMVAT and between IS and IPMVDA, showing that increased SEPMV by IS and DL increases IPMV for academic training and daily activities.

Table 6. Specific indirect effects.

The outcomes allowed verification that DL, through SEPM, has an effect on IPMVAT and IPMDA (). It was found that DL has an effect on SEPMV, which is very relevant because it shows the need to increase the DL so that potential users of the metaverse can feel confident of participating successfully. On the other hand, it is evident that the IS does not have an effect on SEPMV, which is worrying because it shows that companies are not currently encouraging their workers to have an eco-system that facilitates their incorporation. It can also be seen that SEPMV affects both the IPM for professional training and daily life. These results show that the variables that improve the SEPMV directly affect the intention of potential users.

7. Discussion

The effectiveness of the model presented in was examined in this study. The results showed that the questionnaire used in the research was reliable, valid, and can be utilized in future studies conducted in different countries. The findings of the current study indicate that IS does not have a positive and significant impact on SEPMV; however, previous studies have mentioned that IS has an effect on self-efficacy in other activities, such as education (Anthony et al. Citation2019; Chen Citation2022), entrepreneurship (Jafari-Sadeghi et al. Citation2020), mental health (Copeland et al. Citation2021), and innovation (Muda et al. Citation2018).

Some education organizations have reported having organizational support for digital skills development, as the reports in Sweden (Amhag, Hellström, and Stigmar Citation2019), Spain (Cabero-Almenara et al. Citation2020), Russia (Vershitskaya et al. Citation2020), and Australia (Devlin and McKay Citation2016). STEM careers are the basis of training that can be used to successfully adopt the metaverse and various similar technologies.

At present, technology courses are readily available to both students and professionals. However, the demand for institutions to achieve digital skill parity may vary. Professionals like lawyers, administrators, and salespeople may lack a STEM background, leading to diverse teams that can impede digitization and metaverse adoption. MOOC-style programs can efficiently foster teamwork and address this challenge.

Based on this experience, institutions can use it as a reference to develop games for their students or employees. These games can be used to improve their skills in a fun and interactive manner. By creating games involving the company’s different departments, all members can significantly develop their digital skills and become more competitive. Institutions can use this experience as a reference to develop games that encourage skill development and inter-departmental competition for employees. This playful approach improves digital skills and keeps members competitive. Gamification processes facilitate learning (Gimenez-Fernandez et al. Citation2021).

Our study reveals that institutional support does not significantly determine why a person engages in the metaverse. It is more of a personal issue. We found that the training received does not focus on the digital skills of students or workers, assuming that they already possess excellent digital skills due to their daily use, which is not always the case. Therefore, improving digital literacy can increase self-efficacy in participating in the metaverse.

We propose that organizations recognize literacy gaps among their members and devise strategies to narrow them. Evidence suggests that improving digital literacy has a positive impact in various sectors. In this way, it has been possible to recognize the positive effects of high digital literacy on teachers (Dashtestani and Hojatpanah Citation2022), entrepreneurs (Neumeyer, Santos, and Morris Citation2021), students (Terry et al. Citation2019), and firms (Priyono, Moin, and Putri Citation2020).

A predictor of technological participation was previously reported in some countries, such as the USA (Kwon et al. Citation2019), China (Huang and Ren Citation2020), Malaysia (Shaikh et al. Citation2020), Hong Kong (Lee, Yeung, and Cheung Citation2019), and Germany (Börnert-Ringleb, Casale, and Hillenbrand Citation2021). The main contribution of this research is to report variables that explain the intention to participate in the metaverse for daily activities and mainly for teaching purposes.

Institutions offering courses should understand potential consumers’ willingness to pay for metaverse-based education. Identifying influencing factors can increase the conversion rate of traditional students to metaverse-based training.

The manuscript examines the correlation between digital literacy and individuals’ inclination toward using metaverse technologies. The authors draw attention to the metaverse’s emerging significance as a novel digital space with the potential to revolutionize various aspects of human interaction, such as education, commerce, and socialization. However, the adoption of metaverse largely hinges on the digital literacy of individuals, i.e. their ability to use digital technologies effectively and efficiently.

The manuscript presents a study that explores the relationship between digital literacy and metaverse intention, which refers to the willingness of individuals to use the metaverse. The study reveals that digital literacy significantly and positively affects metaverse intention, which means that people with higher digital literacy are more likely to use the metaverse. The authors argue that the results of the study have important implications for the development and adoption of the metaverse. They suggest that promoting the metaverse should be accompanied by programs enhancing digital literacy, including training and education on digital technologies, especially for those less familiar. By increasing digital literacy, individuals can overcome barriers that prevent them from using the metaverse, such as lack of skills or confidence.

Overall, the manuscript contributes to the growing literature on the metaverse and its potential impact on society. The findings of the study offer essential insights into the factors influencing the adoption of the metaverse and suggest practical steps that can be taken to promote its use. The manuscript is well-written, clearly presented, and provides a strong rationale for the importance of the research question. It should be considered for publication in a high-quality journal on digital technologies and their impact on society. On the other hand, companies in other sectors should also consider these results to take advantage of their rapid immersion in the metaverse and soon position themselves to offer various services, which is an indispensable requirement to improve digital literacy.

The data obtained correspond to users in Colombia and need to be evaluated in other countries to know the specific reality. It is also essential to consider that the studies could even be carried out in specific business sectors to help better shape the metaverse offer and to consider the investment to get more users to participate in this technology. This research indicates that people are interested in using the platform for their professional training activities, which contributes to a country’s social, environmental, and economic sustainability, aligning with various SDGs.

8. Conclusion

This result highlights the opportunity to bring people closer to participating in the metaverse through specific training that helps improve digital literacy. Future research should find other variables that significantly affect the SEPMV. An essential element to consider for implementing the metaverse is that it can improve connectivity in the country and the Internet supply at a reasonable price and high download speed, which translates into more benefits. To the extent that universities and companies can offer training services, this acceptance should continue to be evaluated to see if the same variables remain essential and even incorporate new variables that can more fully explain the IPM for vocational training.

Universities may have opportunities to contribute to increasing the preference for virtuality; it is important to evaluate the effect of regulation in promoting the use of the metaverse to generate disruptive training. It was shown that IS and DL had a positive effect on SEPMV. DL had a positive and significant effect. SEPMV was also shown to mediate between IS and IMPVAT significantly, IS and IMPVA, DL and IMPVAT, and DL and IMPVA. It means that digital literacy has a crucial role in the model and should be an aspect to be improved in the potential users of the training courses since it is evidenced that it influences SEPMV and, finally, the intention to use the metaverse for daily activities and professional training.

With communication systems becoming increasingly dynamic, it is common for them to become obsolete quickly. Therefore, essential tools such as the Office environment and Internet browsing are considered while evaluating digital literacy. In a few years, this minimum knowledge is expected to shift towards data science interpretation, artificial intelligence, and programming languages like Python. Institutional support is likely to increase as companies are forced to use more sophisticated technology, leading users to increase their digital performance. According to the social cognitive framework, self-perception is crucial as it directly affects intention. The readiness of people to take on these new digital challenges is still an issue that needs verification.

However, the fact that people feel they can be successful by participating in various activities in the metaverse is a starting point for organizations to work more nimbly to offer professional training services. Future studies should aim to prove that other variables positively and significantly influence SEPMV. Additionally, this study should be replicated in specific population segments, such as millennials and people in other Latin American countries. The present study is limited by the number of participants, which, although it allows the effects between variables to be recognized, makes it difficult to generalize the results, so studies with a larger population are needed.

Metaverse offers immersive training beyond the traditional classroom, allowing workers to engage in simulations relevant to their job roles like manufacturing processes and customer interactions, providing practical knowledge for real-world situations. The metaverse is also an excellent tool for facilitating collaboration between remote teams. Virtual meeting spaces and shared environments allow employees to work together, even if they are located in different parts of the world.

The metaverse incorporates AI algorithms that analyze each worker’s learning style and performance. This personalized approach to training content ensures efficient and effective skill development. High-risk industries can also leverage the metaverse to provide safety and compliance training, allowing workers to practice safety protocols in a virtual environment without real-world risks, enhancing their preparedness for potential hazards. Moreover, the metaverse offers a platform for ongoing learning, allowing workers to access training materials, attend virtual workshops, and interact with subject matter experts at their convenience. It fosters a culture of lifelong learning, empowering workers to enhance their skills and knowledge continuously.

Future studies should consider other variables that may explain self-efficacy, such as social influence, which could play a relevant role in people’s decisions since daring to participate in disruptive training could be better addressed with colleagues or friends. Another variable that can be evaluated in the future is the innovation climate of the institution where the participant is located. A climate of high innovation could influence a greater self-efficacy to participate in the metaverse on professional training issues. The metaverse changes the world, especially professional education, so it is valuable to know if the potential users are ready and which factors affect the engagement for the metaverse offer of education.

Author contributions

Conceptualization, J.S.-U., A.A.-R., S.D.-A.-A.; methodology, J.S.-U., A.A.-R., S.D.-A.-A.; validation, J.S.-U., A.A.-R., S.D.-A.-A.; formal analysis, J.S.-U., A.A.-R., S.D.-A.-A.; investigation, J.S.-U.; data curation, A.A.-R., S.D.-A.-A., D.V.-A., J.A.Y.; writing—original draft preparation, A.A.-R., M.R.-O., S.D.-A.-A., J.A.Y.; writing—review and editing, A.A.-R., S.D.-A..-A., D.V.-A., J.A.Y.; visualization, J.S.-U., A.A.-R., M.R.-O., S.D.-A.-A., D.V.-A., J.A.Y.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Alvarez-Risco, A., S. Del-Aguila-Arcentales, M. A. Rosen, and J. A. Yáñez. 2022. “Social Cognitive Theory to Assess the Intention to Participate in the Facebook Metaverse by Citizens in Peru During the COVID-19 Pandemic.” Journal of Open Innovation: Technology, Market, and Complexity 8 (3): 142. https://doi.org/10.3390/joitmc8030142.

- Alvarez-Risco, A., S. Del-Aguila-Arcentales, J. A. Yáñez, M. A. Rosen, and C. R. Mejia. 2021. “Influence of Technostress on Academic Performance of University Medicine Students in Peru During the COVID-19 Pandemic.” Sustainability 13 (16): 8949. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13168949.

- Alvarez-Risco, A., S. Mlodzianowska, V. García-Ibarra, M. A. Rosen, and S. Del-Aguila-Arcentales. 2021. “Factors Affecting Green Entrepreneurship Intentions in Business University Students in COVID-19 Pandemic Times: Case of Ecuador.” Sustainability 13 (11): 6447. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13116447.

- Amhag, L., L. Hellström, and M. Stigmar. 2019. “Teacher Educators’ Use of Digital Tools and Needs for Digital Competence in Higher Education.” Journal of Digital Learning in Teacher Education 35 (4): 203–220. https://doi.org/10.1080/21532974.2019.1646169.

- Anthony, B., A. Kamaludin, A. Romli, A. F. M. Raffei, D. Nincarean A/L Eh Phon, A. Abdullah, G. L. Ming, N. A. Shukor, M. S. Nordin, and S. Baba. 2019. “Exploring the Role of Blended Learning for Teaching and Learning Effectiveness in Institutions of Higher Learning: An Empirical Investigation.” Education and Information Technologies 24 (6): 3433–3466. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-019-09941-z.

- Bandura, A. 1992. “Self-Efficacy Mechanism in Psychobiologic Functioning.” In Self-Efficacy: Thought Control of Action, edited by Ralf Schwarzer, 355–394. New York: Hemisphere Publishing Corp.

- Becker, J.-M., J.-H. Cheah, R. Gholamzade, C. M. Ringle, and M. Sarstedt. 2023. “PLS-SEM’s Most Wanted Guidance.” International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management 35 (1): 321–346. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCHM-04-2022-0474.

- Bogaert, M., M. Ballings, R. Bergmans, and D. Van den Poel. 2021. “Predicting Self-Declared Movie Watching Behavior Using Facebook Data and Information-Fusion Sensitivity Analysis.” Decision Sciences 52 (3): 776–810. https://doi.org/10.1111/deci.12406.

- Börnert-Ringleb, M., G. Casale, and C. Hillenbrand. 2021. “What Predicts Teachers’ Use of Digital Learning in Germany? Examining the Obstacles and Conditions of Digital Learning in Special Education.” European Journal of Special Needs Education 36 (1): 80–97. https://doi.org/10.1080/08856257.2021.1872847.

- Cabero-Almenara, J., J.-J. Gutiérrez-Castillo, A. Palacios-Rodríguez, and J. Barroso-Osuna. 2020. “Development of the Teacher Digital Competence Validation of DigCompEdu Check-In Questionnaire in the University Context of Andalusia (Spain).” Sustainability 12 (15): 6094. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12156094.

- Chen, Z. 2022. “Exploring the Application Scenarios and Issues Facing Metaverse Technology in Education.” Interactive Learning Environments, 1–13.

- Copeland, W. E., E. McGinnis, Y. Bai, Z. Adams, H. Nardone, V. Devadanam, J. Rettew, and J. J. Hudziak. 2021. “Impact of COVID-19 Pandemic on College Student Mental Health and Wellness.” Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry 60 (1): 134–141.e132. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2020.08.466.

- Cruz-Torres, W., A. Alvarez-Risco, and S. Del-Aguila-Arcentales. 2021. “Impact of Enterprise Resource Planning (ERP) Implementation on Performance of an Education Enterprise: A Structural Equation Modeling (SEM).” Studies in Business and Economics 16 (2): 37–52. https://doi.org/10.2478/sbe-2021-0023.

- Dashtestani, R., and S. Hojatpanah. 2022. “Digital Literacy of EFL Students in a Junior High School in Iran: Voices of Teachers, Students and Ministry Directors.” Computer Assisted Language Learning 35 (4): 635–665. https://doi.org/10.1080/09588221.2020.1744664.

- de la Fuente, J., D. F. Kauffman, and E. Boruchovitch. 2023. “Editorial: Past, Present and Future Contributions from the Social Cognitive Theory (Albert Bandura) [Editorial].” Frontiers in Psychology 14. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1258249.

- Devlin, M., and J. McKay. 2016. “Teaching Students Using Technology: Facilitating Success for Students from Low Socioeconomic Status Backgrounds in Australian Universities.” Australasian Journal of Educational Technology 32 (1): 92–106. https://doi.org/10.14742/ajet.2053.

- Diamantidis, A. D., and P. Chatzoglou. 2019. “Factors Affecting Employee Performance: An Empirical Approach.” International Journal of Productivity and Performance Management 68 (1): 171–193. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJPPM-01-2018-0012.

- Farrell, L., T. Newman, and C. Corbel. 2021. “Literacy and the Workplace Revolution: A Social View of Literate Work Practices in Industry 4.0.” Discourse: Studies in the Cultural Politics of Education 42 (6): 898–912. https://doi.org/10.1080/01596306.2020.1753016.

- Fornell, C., and D. F. Larcker. 1981. “Evaluating Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error.” Journal of Marketing Research 18 (1): 39–50. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224378101800104.

- Gadalla, E., K. Keeling, and I. Abosag. 2013. “Metaverse-Retail Service Quality: A Future Framework for Retail Service Quality in the 3D Internet.” Journal of Marketing Management 29 (13–14): 1493–1517. https://doi.org/10.1080/0267257X.2013.835742.

- Georgakopoulou, A., S. Iversen, and C. Stage. 2020. “Measuring and Narrating the Disrupted Self on Instagram.” In Quantified Storytelling: A Narrative Analysis of Metrics on Social Media, edited by A. Georgakopoulou, S. Iversen, and C. Stage, 31–59. Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-48074-5_2.

- Gimenez-Fernandez, E., C. Abril, H. Breuer, and S. Gudiksen. 2021. “Gamification Approaches for Open Innovation Implementation: A Conceptual Framework.” Creativity and Innovation Management 30 (3): 455–474. https://doi.org/10.1111/caim.12452.

- Hasse, C. 2017. “Technological Literacy for Teachers.” Oxford Review of Education 43 (3): 365–378. https://doi.org/10.1080/03054985.2017.1305057.

- Huang, G., and Y. Ren. 2020. “Linking Technological Functions of Fitness Mobile Apps with Continuance Usage among Chinese Users: Moderating Role of Exercise Self-Efficacy.” Computers in Human Behavior 103: 151–160. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2019.09.013.

- Huynh-The, T., Q.-V. Pham, X.-Q. Pham, T. T. Nguyen, Z. Han, and D.-S. Kim. 2023. “Artificial Intelligence for the Metaverse: A Survey.” Engineering Applications of Artificial Intelligence 117: 105581. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.engappai.2022.105581.

- Iwanaga, J., E. C. Muo, Y. Tabira, K. Watanabe, S. J. Tubbs, A. V. D’Antoni, M. Rajaram-Gilkes, M. Loukas, M. K. Khalil, and R. S. Tubbs. 2023. “Who Really Needs a Metaverse in Anatomy Education? A Review with Preliminary Survey Results.” Clinical Anatomy 36 (1): 77–82. https://doi.org/10.1002/ca.23949.

- Jafari-Sadeghi, V., J.-M. Nkongolo-Bakenda, L.-P. Dana, R. B. Anderson, and P. P. Biancone. 2020. “Home Country Institutional Context and Entrepreneurial Internationalization: The Significance of Human Capital Attributes.” Journal of International Entrepreneurship 18 (2): 165–195. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10843-019-00264-1.

- Jauhiainen, J. S., C. Krohn, and J. Junnila. 2023. “Metaverse and Sustainability: Systematic Review of Scientific Publications Until 2022 and Beyond.” Sustainability 15 (1): 346. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15010346.

- Kwon, K., A. T. Ottenbreit-Leftwich, A. R. Sari, Z. Khlaif, M. Zhu, H. Nadir, and F. Gok. 2019. “Teachers’ Self-Efficacy Matters: Exploring the Integration of Mobile Computing Device in Middle Schools.” TechTrends 63 (6): 682–692. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11528-019-00402-5.

- Lee, C., A. S. Yeung, and K. W. Cheung. 2019. “Learner Perceptions Versus Technology Usage: A Study of Adolescent English Learners in Hong Kong Secondary Schools.” Computers & Education 133: 13–26. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2019.01.005.

- Lin, H., S. Wan, W. Gan, J. Chen, and H. C. Chao. 2022. “Metaverse in Education: Vision, Opportunities, and Challenges.” 2022 IEEE International Conference on Big Data (Big Data), 17–20 December 2022.

- Liu, G., M. U. Rehman, and Y. Wu. 2021. “Personal Trajectory Analysis Based on Informative Lifelogging.” Multimedia Tools and Applications 80 (14): 22177–22191. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11042-021-10755-w.

- Muda, I., M. Rahmanta, M. Marhayanie, and A. S. Putra. 2018. “Institutional Fishermen Economic Development Models and Banking Support in the Development of the Innovation System of Fisheries and Marine Area in North Sumatera.” IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering 288 (1): 012082. https://doi.org/10.1088/1757-899X/288/1/012082.

- Neumeyer, X., S. C. Santos, and M. H. Morris. 2021. “Overcoming Barriers to Technology Adoption When Fostering Entrepreneurship Among the Poor: The Role of Technology and Digital Literacy.” IEEE Transactions on Engineering Management 68 (6): 1605–1618. https://doi.org/10.1109/TEM.2020.2989740.

- Ondrejka, C. 2004. “Escaping the Gilded Cage: User Created Content and Building the Metaverse.” NYL Sch. L. Rev 49: 81.

- Priyono, A., A. Moin, and V. N. Putri. 2020. “Identifying Digital Transformation Paths in the Business Model of SMEs During the COVID-19 Pandemic.” Journal of Open Innovation: Technology, Market, and Complexity 6 (4): 104. https://doi.org/10.3390/joitmc6040104.

- Ramsey, J. B. 1969. “Tests for Specification Errors in Classical Linear Least-Squares Regression Analysis.” Journal of the Royal Statistical Society: Series B (Methodological) 31 (2): 350–371. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2517-6161.1969.tb00796.x.

- Shaikh, I. M., M. A. Qureshi, K. Noordin, J. M. Shaikh, A. Khan, and M. S. Shahbaz. 2020. “Acceptance of Islamic Financial Technology (FinTech) Banking Services by Malaysian Users: An Extension of Technology Acceptance Model.” Foresight (los Angeles, Calif ) 22 (3): 367–383. https://doi.org/10.1108/FS-12-2019-0105.

- Singh, J., M. Malhotra, and N. Sharma. 2022. “Metaverse in Education: An Overview.” In Applying Metalytics to Measure Customer Experience in the Metaverse, edited by Devesh Bathla and Amandeep Singh, 135–142. Pennsylvania.

- Stephan, U., L. M. Uhlaner, and C. Stride. 2015. “Institutions and Social Entrepreneurship: The Role of Institutional Voids, Institutional Support, and Institutional Configurations.” Journal of International Business Studies 46 (3): 308–331. https://doi.org/10.1057/jibs.2014.38.

- Stephenson, N. 1992. Snow Crash. New York: Bantam Books.

- Streukens, S., and S. Leroi-Werelds. 2016. “Bootstrapping and PLS-SEM: A Step-by-Step Guide to get More out of Your Bootstrap Results.” European Management Journal 34 (6): 618–632. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.emj.2016.06.003.

- Svensson, G., C. Ferro, N. Høgevold, C. Padin, J. Carlos Sosa Varela, and M. Sarstedt. 2018. “Framing the Triple Bottom Line Approach: Direct and Mediation Effects Between Economic, Social and Environmental Elements.” Journal of Cleaner Production 197: 972–991. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.06.226.

- Terry, J., A. Davies, C. Williams, S. Tait, and L. Condon. 2019. “Improving the Digital Literacy Competence of Nursing and Midwifery Students: A Qualitative Study of the Experiences of NICE Student Champions.” Nurse Education in Practice 34: 192–198. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nepr.2018.11.016.

- Tkachuk, V., Y. Yechkalo, S. Semerikov, M. Kislova, and Y. Hladyr. 2021. Using Mobile ICT for Online Learning During COVID-19 Lockdown. Cham: Information and Communication Technologies in Education, Research, and Industrial Applications. 2021//.

- Tlili, A., R. Huang, B. Shehata, D. Liu, J. Zhao, A. H. S. Metwally, H. Wang, … D. Burgos. 2022. “Is Metaverse in Education a Blessing or a Curse: A Combined Content and Bibliometric Analysis.” Smart Learning Environments 9 (1): 24. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40561-022-00205-x.

- Tondeur, J., K. Aesaert, S. Prestridge, and E. Consuegra. 2018. “A Multilevel Analysis of What Matters in the Training of pre-Service Teacher’s ICT Competencies.” Computers & Education 122: 32–42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2018.03.002.

- Vershitskaya, E. R., A. V. Mikhaylova, S. I. Gilmanshina, E. M. Dorozhkin, and V. V. Epaneshnikov. 2020. “Present-day Management of Universities in Russia: Prospects and Challenges of e-Learning.” Education and Information Technologies 25 (1): 611–621. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-019-09978-0.

- Wang, S., and R. Fu. 2020. “Research on the Influencing Factors of the Communication Effect of Tik Tok Short Videos About Intangible Cultural Heritage.” In Advances in Creativity, Innovation, Entrepreneurship and Communication of Design, edited by Evangelos Markopoulos, Ravindra S. Goonetilleke, Amic G. Ho, and Yan Luximon, 275–282. New York: Springer International Publishing.

- Yen, A.-Z., H.-H. Huang, and H.-H. Chen. 2018. “Detecting Personal Life Events from Twitter by Multi-Task lstm.” In Companion Proceedings of the The Web Conference (pp. 21–22).