ABSTRACT

International policymakers prioritize financial stability and inclusion, but often view them as separate goals, overlooking potential overlap and trade-offs. If synergies and trade-offs between the two concepts are not recognized and understood, policy design may yield less-than-ideal results. This paper provides a systematic review of the theoretical literature on financial inclusion and financial stability as well as empirical research initiatives examining the relationship between the two concepts. We found that current studies do not always present a unified theoretical approach or conceptual framework to explain the channels of the relationship between financial inclusion and stability. Empirical studies to date offer divergent views on the financial inclusion and stability nexus. While some studies are inconclusive, some also suggest that financial inclusion has a positive and significant impact on financial stability, as explained by the institutional theory. While other studies, supported by the aggressive credit expansion theory, reveal that financial inclusion can have a negative influence on financial stability. Through this comprehensive review, we intend to improve awareness and cohesion among scholars and policy makers of financial inclusion and financial stability while also facilitating the development of solid foundations to address future research and policy making challenges.

1. Introduction

International policy makers place a high priority on both financial stability and financial inclusion. For instance, a lot of attention is being paid to the global promotion of financial inclusion through programs like the Global Partnership for Financial Inclusion (launched in 2010 in Seoul, South Korea) and the G-20's Maya Declaration (launched in 2011 in Riviera Maya, Mexico), which aim to reduce poverty and inequality, create wealth, and support sustainable economic growth. Comparably, in the wake of the global financial crisis (GFC) of 2007–2009, regulators and policy makers around the globe have emphasized the need for financial sector reform to enhance financial stability on a national, regional, and global scale. This is demonstrated by calls made by international organizations like the Financial Stability Board and the International Monetary Fund (IMF) to improve global financial stability by enacting reforms like the Basel III accords and other complementary regulatory changes (Čihák, Mare, and Melecky Citation2021, Citation2016).

There is no one standard measure of financial inclusion. In general terms, financial inclusion refers to the provision of accessible, affordable, secure, effective, transparent, and high-quality financial products and services to businesses and households, while ensuring efficient financial system operation (Gadanecz and Tissot Citation2017; Amidžic, Massara, and Mialou Citation2014; Sahay et al. Citation2015). Similarly, there is no universally recognized definition of financial stability. Generally, a stable financial system is viewed as one that can efficiently allocate resources, manage risks, maintain employment, and eliminate disruptive price movements, ensures stability and self-correction, preventing adverse events from disrupting the economy (Schinasi Citation2004; World Bank Citation2015; Gadanecz and Jayaram Citation2008; Jeanneau Citation2014).

There is evidence to suggest that policy makers typically seek financial stability and inclusion as distinct goals, ignoring the possibility of overlap and potential trade-offs between the two. For instance, one important takeaway from the Global Financial Crisis of 2007–2009 is that, on the one hand, a significant impairment of financial stability might result from a rapid growth of credit to economic actors who are not creditworthy (see, Amatus and Alireza Citation2015; Morgan and Pontines Citation2018). Conversely, increased use of financial services and products by economic actors that have previously been unbanked or financially excluded might promote financial stability by helping financial institutions diversify their risks (see, Čihák, Mare, and Melecky Citation2016; Mendoza, Quadrini, and Rios-Rull Citation2009; Al-Smadi Citation2018). Nonetheless, the utilization of ‘newer’ and less understood financial services and assets contributed significantly to the worsening of the Global Financial Crisis. On this basis financial stability may be positively or negatively impacted by financial inclusion. Considering this, it is vital to recognize and comprehend possible trade-offs as well as areas of convergence between financial inclusion and stability to develop and execute well-informed policies that advance both goals simultaneously. Policy design runs the danger of producing less-than-ideal results if these links are not highlighted and understood.

Efforts should be made to improve awareness and cohesion among scholars and policy makers of financial inclusion and financial stability while also facilitating the development of solid foundations to address future research and policy making challenges. One way of doing this is to identify what studies on the relationship between financial inclusion and stability have recently been conducted and published in academic and scholarly journals as well as which theories contribute to the explanation of the relationship between the two concepts. In this regard, the objective of our study is to offer an organizing and integrative lens through which to view and understand the different contributions to knowledge creation from studies that investigate the relationship between financial inclusion and financial stability.

Our study contributes to existing literature in four ways. First, it provides a systematic review of common definitions and measures of financial inclusion and financial stability, respectively, while also identifying the overlaps in each case. In this way, it complements earlier studies such as Cull, Ehrbeck, and Holle (Citation2014), Demirgüç-Kunt, Klapper, and Singer (Citation2017) as well as Duvendack and Mader (Citation2018) that have focused more on the positive socio-economic and macroeconomic spill overs of financial inclusion, as opposed to how it is defined and/or measured. Second, by presenting a detailed understanding of how financial inclusion and financial stability are respectively defined and measured, this paper provides a synthesized and holistic view that policy makers can use to balance the trade-offs between inclusion and stability while developing effective policies aimed at promoting inclusion and stability. This will ensure that previously underbanked and underserved economic agents have greater access to financial products and services in a sustainable and safe manner. Third, the study offers a comprehensive review of the theoretical background of the linkage between financial inclusion and financial stability. This allows for the identification of a unified theoretical approach or conceptual framework that policy makers can use to explain the channels of the relationship between financial inclusion and financial stability. Fourth, by conducting a comprehensive review of the empirical literature on the relationship between financial inclusion and financial stability, our study provides a detailed understanding of the extent of the country and regional coverage in various studies, as well as the methodological issues and nature of results. This allows for recognizing overlaps and policy lessons while also identifying any gaps in the empirical literature to be closed in future studies.

The rest of this study is organized into the following sections. Section 2 provides a conceptualization of financial inclusion and financial stability, respectively. Section 3 explores the theoretical nexus between financial inclusion and financial stability, placing emphasis on the transmission channels that underpin the relationship. The empirical link between financial inclusion and financial stability is covered in Section 4, highlighting how theory and empirical evidence come together to facilitate an understanding of the nature of the relationship between the two concepts. A detailed discussion of the empirical literature is provided in Section 5, with an emphasis on the overlaps and gaps. Section 6 concludes the study.

2. Conceptualization of Financial Inclusion and Financial Stability

This Section contributes to the financial inclusion and financial stability literature by providing a systematic review of common definitions and measures of financial inclusion and financial stability, respectively, while also identifying the overlaps in each case. Policy makers can use this to develop effective policies that promote both financial stability and financial inclusion while balancing the trade-offs between the two.

2.1. Financial Inclusion

Financial inclusion is a concept that varies across countries and can be viewed from various perspectives, including users, suppliers, regulators, and policymakers. Working definitions of financial inclusion can be categorized into two types: one-dimensional definitions that focus on access to formal financial services and products by economic agents (see Carbó, Gardener, and Molyneux Citation2005; Leyshon and Thrift Citation1995), and broader, multidimensional definitions that consider use, cost, and quality (see Allen et al. Citation2016; Demirgüç-Kunt and Klapper Citation2013; Demirgüç-Kunt, Klapper, and Singer Citation2017). presents an overview of how access, use, cost, and quality are understood in the multidimensional view of financial inclusion. It also presents commonly used proxies for access, use, cost, and quality. Evaluating these proxies over time can provide policymakers with a sense of financial inclusion trajectory at a country, regional, or global level, guiding policy development.

Table 1. Dimensions and proxies of financial Inclusion.

reveals that proxies of access to financial inclusion measure the availability of physical financial services and products based on the distance to them. These proxies typically include geographic or demographic penetration indicators such as ATMs and bank branches per 1000 km. Proxies of the use of formal financial services and products involve households having at least one deposit account with a formal financial institution, including transferable, sight, savings, and fixed-term deposits. Common use proxies also include household borrowers with at least one loan account with a formal financial institution, including mortgage loans, consumer loans, financial leases, and hire-purchase credit (Espinosa-Vega et al. Citation2020; Pesqué-Cela et al. Citation2021; Beck, Demirgüç-Kunt, and Levine Citation2007; Amidžic, Massara, and Mialou Citation2014; Queralt Citation2016). The cost dimension of financial inclusion is determined by the average cost of opening, maintaining, and transferring basic bank accounts. A well-developed financial sector with high competition can offer lower costs. Lower costs indicate better financial inclusion. The quality dimension of formal financial services and products is measured by indicators such as financial literacy, disclosure requirements, and formal dispute resolution frameworks at the country level (Espinosa-Vega et al. Citation2020; Pesqué-Cela et al. Citation2021; Beck, Demirgüç-Kunt, and Levine Citation2007; Amidžic, Massara, and Mialou Citation2014; Queralt Citation2016).

The multifaceted view of financial inclusion can be understood from definitions of financial inclusion from various international standard-setting bodies (SSBs), including the International Monetary Fund (IMF), the World Bank, the Alliance for Financial Inclusion (AFI), the Bank of International Settlements (BIS), and the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), respectively.Footnote1 The definitions of financial inclusion presented in highlight the importance of access and effective use of formal financial products and services given constraints such as time and distance while being mindful of the importance of minimizing associated costs and ensuring the necessary quality. The IMF and AFI definitions view financial inclusion as a vehicle that enables households and firms to guard against macroeconomic shocks and better manage risks. In this way, it provides the means for households to smooth their income and grow wealth over time while also affording firms the resources to invest, create businesses and help grow the economy. It can contribute to economic sustainability and support monetary and financial stability by making savings and investments more efficient, safe, and transparent through the functioning of robust financial infrastructure. Complementarily, the World Bank, BIS and OECD definitions emphasize that financial inclusion should be extended to all segments of society in a safe, secure, and sustainable manner. The implication is that although financial services and products should be extended to all economic agents, necessary care must be taken to ensure that this is done in a responsible and sustainable manner, as uncontrolled expansion in financial access can lead to instability. From a policy maker’s perspective, the pursuit of financial inclusion should therefore strive to achieve an optimal combination of its four key dimensions, namely access, use, cost, and quality, respectively.

Table 2. Definition of financial inclusion by various international organizations.

2.2. Financial Stability

Financial stability does not have a universally accepted definition, but a functioning definition is crucial for analyzing policy challenges in the expanding financial stability landscape. An ideal financial system should possess qualities of efficiency and should work to maintain them at national, regional, and global levels while preventing financial instability (Schinasi Citation2004; Allen and Wood Citation2006; Rosengren Citation2011; Morgan and Pontines Citation2018). A stable financial system involves efficient resource allocation, risk assessment, and management, which maintains employment levels and reduces volatility in relative asset prices. Self-corrective processes make it resistant to shocks. Banks are less likely to fund successful business projects in an unstable financial system, as they are less willing to tap into household surplus savings. Highly volatile asset prices, which can be indicative of an unstable financial system, can lead to negative consequences, such as bank runs, stock market collapses, high non-performing loans, and hyperinflation (Schinasi Citation2004; Allen and Wood Citation2006; Rosengren Citation2011; Morgan and Pontines Citation2018; Gadanecz and Jayaram Citation2008).

Financial stability is assessed at both institutional and systemic levels. National central banks evaluate financial stability through financial stability reports (FSRs). They examine Financial Soundness Indicators (FSIs) at the institutional level and aggregate them to the systemic level. FSIs, launched by the IMF in the late 1990s, evaluate a nation's risks to financial stability and assess the financial stability of financial institutions, businesses, and households. They offer an overall assessment of the financial stability and health of a nation's financial institutions, as well as that of its businesses and households (Gadanecz and Jayaram Citation2008; San Jose and Georgiou Citation2008). presents the set of core FSIs recognized internationally.

Table 3. Core financial soundness indicators for deposit takers.

According to , the primary collection of financial sector indicators (FSIs) is based on the CAMELS grading system, which stands for capital sufficiency, asset quality, earnings, liquidity, and market risk sensitivity. The IMF releases the Global Financial Stability Report (GFSR) every two years, evaluating global financial system risks using country-level FSI data. The report aims to identify policies to reduce systemic risks, prevent crises, and contribute to global financial stability and economic growth in its 190 member nations. The z-score is a widely used indicator for assessing financial stability, similar to FSIs. It compares a bank's buffers to its risk, assessing solvency risk. The z-score calculates the likelihood of a financial institution's insolvency based on assets and debt value, with a higher z-score indicating a decreased likelihood of insolvency (Demirgüç-Kunt, Klapper, and Singer Citation2017; Laeven and Levine Citation2009; Čihák and Hesse Citation2010). FSIs and z-score assess a financial institution's resilience to shocks and unexpected losses. Deposit takers’ liquid assets to total assets ratio evaluates their ability to withstand global market disruptions and idiosyncratic funding shocks, while regulatory capital to risk-weighted assets measures a bank's capacity to absorb unexpected losses (San Jose and Georgiou Citation2008; IMF Citation2008).

Further discussion incorporates financial stability definitions from international standard setting bodies (SSBs), including the IMF, World Bank, BIS, and European Central Bank (ECB). These SSBs are chosen based on their ongoing work in the global financial stability landscape.

From , all the definitions have discernible overlaps. They each underscore that a stable financial system is one that ensures efficient financial intermediation without impeding economic growth. This involves the ability to withstand shocks and unravel financial imbalances using efficient risk management instruments. The IMF, World Bank and BIS definitions specifically touch on the all-important concept of self-correction, or the potential for the financial system to inherently possess the ability to prevent or eliminate both internal and external financial imbalances emanating from unforeseen shocks, without destabilizing efficient macroeconomic performance. Absent of these efficiency qualities, instability can lead to negative shocks spreading throughout the system, causing financial crises. Financial stability encompasses various aspects of money and the financial system, ensuring that finance plays a role in resource and risk allocation, savings mobilization, development, growth, and wealth accumulation, while maintaining the smooth operation of the economy.

Table 4. International Standard Setting Bodies and their definition of financial stability.

3. Theoretical Nexus between Financial Inclusion and Financial Stability

Finding and comprehending the synergies and potential trade-offs between financial stability and inclusion is essential to developing and implementing informed policies in a coordinated manner. If these relationships are not highlighted and comprehended, policy design may result in less-than-optimal outcomes. The objective of this Section is to examine the theoretical relationships that exist between financial stability and inclusion. Scholars’ perspectives on the theoretical connections between financial inclusion and stability differ. Most of the studies in this area are not clear about how financial inclusion affects financial stability. The discussion focuses on the positive and negative relationship between financial inclusion and financial stability.

3.1. Positive Impact of Financial Inclusion on Financial Stability

A number of studies have been done that highlight the positive effects of financial inclusion on financial stability (see Khan Citation2011; Cull, Demirgüç-Kunt, and Lyman Citation2012; Ozili Citation2018; Ahamed and Mallick Citation2019; Berlin and Mester Citation1999; Ozili Citation2020; Pham and Doan Citation2020; Frączek Citation2019; Danisman and Tarazi Citation2020; Kamal, Hussain, and Khan Citation2021; Ozili Citation2021; Eton, Mwosi, and Okello-Obura Citation2021). In these studies, scholars advance several ways through which greater financial inclusion can lead to financial stability. The transmission channels are broadly in line with the institutional theory (Meyer and Rowan Citation1977; DiMaggio and Powell Citation1983), wherein financial inclusion initiatives are posited to foster greater resource and financial intermediation efficiency, which in turn enhances financial stability provided that a nation establishes robust financial infrastructure and strengthened financial sector regulation and supervision. A similar point is made by Abosedra et al. (Citation2023) and Arayssi, Fakih, and Kassem (Citation2019) who point out that policies that seek to enhance the effectiveness and functioning of institutions like a nation's legal system, citizens’ ability to vote in elections, freedom of speech, and the state of financial development are critical to spur on sustainable and inclusive economic growth. These efforts also facilitate better access and use of banking services by a large portion of the population, including the underprivileged (Okpara Citation2011; Prasad Citation2010; Cull, Demirgüç-Kunt, and Lyman Citation2012). Further, as financial systems, and the supervisory and regulatory frameworks are strengthened, financial stability in the previous period can have positive spillovers into the current period’s level of financial stability (Morgan and Pontines Citation2018; Hakimi, Boussaada, and Karmani Citation2022).

The ways through which financial inclusion can positively affect financial stability include:

A more resilient economy is produced by diversifying the funding sources of financial institutions and absorbing a wider range of economic agents (Khan Citation2011; Cull, Demirgüç-Kunt, and Lyman Citation2012; Ozili Citation2018; Ahamed and Mallick Citation2019; Berlin and Mester Citation1999; Ozili Citation2020; Pham and Doan Citation2020).

Expanding the scope and effectiveness of savings intermediation (Mehrotra and Yetman Citation2015; Khan Citation2011; Ozili Citation2021; Cull, Demirgüç-Kunt, and Lyman Citation2012; Ahamed and Mallick Citation2019; Saha and Dutta Citation2022; Saha and Dutta Citation2021).

Providing ways for households to become more resistant to the various vulnerabilities they face (Mehrotra and Yetman Citation2015; Khan Citation2011; Ozili Citation2021; Cull, Demirgüç-Kunt, and Lyman Citation2012; Ahamed and Mallick Citation2019; Saha and Dutta Citation2022; Saha and Dutta Citation2021).

Creating a more stable foundation of customer deposits and promoting greater confidence in the banking system. In this sense, low-income families tend to save and borrow responsibly even during financial crises when there is faith in the financial system, with deposits being held safely and loans being repaid (Khan Citation2011; Cull, Demirgüç-Kunt, and Lyman Citation2012; Ozili Citation2018; Ahamed and Mallick Citation2019; Berlin and Mester Citation1999; Ozili Citation2020; Pham and Doan Citation2020).

Limiting the existence of a sizable informal sector in order to increase the effectiveness of monetary policy (Mehrotra and Yetman Citation2015; Khan Citation2011; Ozili Citation2021; Cull, Demirgüç-Kunt, and Lyman Citation2012; Ahamed and Mallick Citation2019).

Assisting in the efficient execution of anti-terrorism and anti-money-laundering laws (Mehrotra and Yetman Citation2015; Khan Citation2011; Ozili Citation2021; Cull, Demirgüç-Kunt, and Lyman Citation2012; Ahamed and Mallick Citation2019).

Lowering income disparity in order to increase social and political stability (Khan Citation2011; Cull, Demirgüç-Kunt, and Lyman Citation2012; Ozili Citation2018; Ahamed and Mallick Citation2019; Berlin and Mester Citation1999; Ozili Citation2020; Pham and Doan Citation2020).

Summarily, financial institutions can benefit from financial inclusion by obtaining affordable deposits from retail consumers, reducing their marginal costs, and providing banking services in a more inclusive financial sector. This approach helps banks tackle asymmetrical information problems by developing deeper customer connections, allowing them to work more efficiently in a stronger institution setting with expanded creditor rights (Aduda and Kalunda Citation2012; Kamal, Hussain, and Khan Citation2021; Sethy and Goyari Citation2022; Barik and Pradhan Citation2021; Petersen and Rajan Citation1995; Ahamed and Mallick Citation2019).

3.2. Negative Impact of Financial Inclusion on Financial Stability

There is literature that contends that increased financial inclusion may result in banking sector instability (see Igan and Pinheiro Citation2011; Mehrotra and Yetman Citation2015; Khan Citation2011; Ozili Citation2021; Cull, Demirgüç-Kunt, and Lyman Citation2012; Ahamed and Mallick Citation2019; Danisman and Tarazi Citation2020). The adverse impact of financial inclusion on financial stability can generally be explained through the extreme financial inclusion (EFI) theory (Morawetz Citation1908). EFI exists when economic agents are given access to the formal financial sector and its range of products and services, regardless of their level of income or level of risk. It is based on several justifications for completely eliminating financial access restrictions (Cull, Demirgüç-Kunt, and Lyman Citation2012; Ahamed and Mallick Citation2019; Frączek Citation2019; Danisman and Tarazi Citation2020; Feghali, Mora, and Nassif Citation2021). Inadvertently, this might result in a violation of the integrity of the financial system, for example, if legal obstacles to financial inclusion, such as methods of identification and verification procedures, were fully abolished to meet rising demand. Avoiding EFI is preferable since it can lessen the likelihood of negative externalities like fraud that might otherwise undermine financial stability.

Literature argue that financial instability risks can manifest from:

Low-income clients, outsourcing activities, the makeup of local financial institutions, and financial product developments (Mehrotra and Yetman Citation2015; Khan Citation2011; Ozili Citation2021; Cull, Demirgüç-Kunt, and Lyman Citation2012; Ahamed and Mallick Citation2019).

Increased involvement of low-income groups in the financial system, which could lead to high transaction and information costs (due to lack of collateral or credit history) and inefficiencies that are challenging to address technically and managerially (Mehrotra and Yetman Citation2015; Khan Citation2011; Ozili Citation2021; Cull, Demirgüç-Kunt, and Lyman Citation2012; Ahamed and Mallick Citation2019).

An important factor contributing to the inefficiency of financial systems is the rise of information asymmetries (Mehrotra and Yetman Citation2015; Khan Citation2011; Ozili Citation2021; Cull, Demirgüç-Kunt, and Lyman Citation2012; Ahamed and Mallick Citation2019; Saha and Dutta Citation2022; Saha and Dutta Citation2021).

Locally focused financial institutions, such as cooperatives or rural banks, may have inadequate governance, lax regulation, lack of supervision, engage in inter-institutional lending, and have a high geographic concentration, making them more susceptible to disasters and downturns (Mehrotra and Yetman Citation2015; Khan Citation2011; Ozili Citation2021; Cull, Demirgüç-Kunt, and Lyman Citation2012; Ahamed and Mallick Citation2019; Saha and Dutta Citation2022; Saha and Dutta Citation2021).

Financial product developments and outsourcing operations that put financial stability at risk by creating new risks due to a lack of regulation or supervision (Mehrotra and Yetman Citation2015; Khan Citation2011; Ozili Citation2021; Cull, Demirgüç-Kunt, and Lyman Citation2012; Ahamed and Mallick Citation2019; Saha and Dutta Citation2022; Saha and Dutta Citation2021).

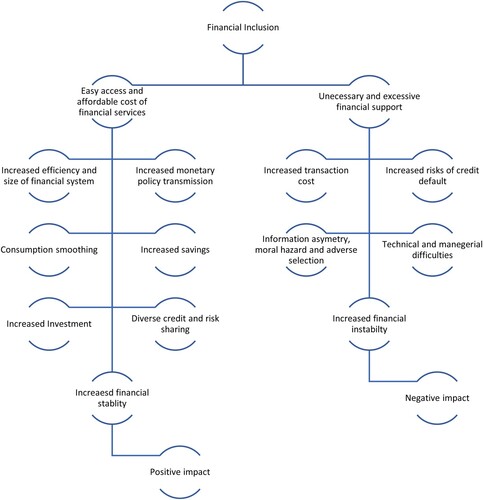

From the discussion so far, the theoretical basis for the relationship between financial inclusion and financial stability covers arguments for both a positive and negative linkage. In this regard, provides a graphical summary of the advanced theoretical relationships between financial inclusion and financial stability.

Figure 1. The Linkages between Financial Inclusion and Financial Stability. Source: Authors’ own compilation.

On one hand, shows that an increased level of financial inclusion translates into easy access and affordable cost of financial services as well as an enhanced level of efficiency and size of the financial system. This informs increased formalization of the financial sector through the improvement in the monetary policy transmission (see, Mbutor and Uba Citation2013; Mehrotra and Yetman Citation2014, Citation2015; Mehrotra and Nadhanael Citation2016; Lenka and Bairwa Citation2016; Huong Citation2018; Yoshino and Morgan Citation2018; Čihák, Mare, and Melecky Citation2021;). Further, high levels of financial inclusion help to smoothen consumption and mobilize savings from the informal to formal sectors, thus increasing banks’ deposit base and stability (see, Hawkins Citation2006; Hannig and Jansen Citation2010; Prasad Citation2010; Cull, Demirgüç-Kunt, and Lyman Citation2012; Han and Melecky Citation2013; Rahman Citation2014; Neaime and Gaysset Citation2018; Dienillah, Anggraeni, and Sahara Citation2018; Čihák, Mare, and Melecky Citation2021). A higher level of savings translates into increased investment finance as well as diverse avenues for credit and risk sharing. For instance, increased lending to small and medium sized enterprises (SMEs) potentially diversifies bank assets, reduces loan book exposure to any single borrower and informs financial stability by reducing the likelihood of credit default and non-performing loans (NPLs) (see, Cull, Demirgüç-Kunt, and Lyman Citation2012; Rahman Citation2014; Čihák, Mare, and Melecky Citation2016; Chen, Feng, and Wang Citation2018; Čihák, Mare, and Melecky Citation2021). With greater financial sector regulation and formalization, potential instability is averted, and a stable financial system is maintained.

On the other hand, reflects that increased financial inclusion may result in information asymmetry, elevated transaction and information costs, and increased risks of credit default as financial institutions move into new and remote locations to cater for a wider participation of low-income people as well as small and medium sized enterprises (SMEs) in the formal financial system. This can create inefficiencies in the financial system which may lead to financial instability (see, Beck and De Jonghe Citation2013; Sahay et al. Citation2015; García and José Citation2016). For instance, to increase the financial inclusion of low-income people as well as SMEs, banks can outsource various know your client (KYC) functions such as the assessment of credit worthiness. In this regard, they can face reputational risks, information asymmetry, moral hazard, and adverse selection, which may impede on the efficiency of their operations and of the financial system (see, Khan Citation2011; Aduda and Kalunda Citation2012; Barik and Pradhan Citation2021; Kamal, Hussain, and Khan Citation2021; Sethy and Goyari Citation2022). Further, as non-bank financial institutions (NBFIs) such as microfinance institutions (MFIs) provide their services to the previously unbanked to increase financial inclusion, they will lead to an increase the credit base. The rapid growth in the credit base can create difficulties in efficient credit assessment and can increase the probability of credit default. Subsequently, because of the ever-increasing financial sector integration between banks and NBFIs, banks can face liquidity crises if credit defaults rise. This can adversely affect the overall regulation of financial system and lead to financial instability (Dell’Ariccia and Marquez Citation2006; García and José Citation2016; Ahmad Citation2018).

4. Empirical Evidence of Effects of Financial Inclusion on Financial Stability

The objective of our systematic review of empirical literature is to offer a lens through which to view and understand the different contributions to knowledge creation from studies that empirically investigate the relationship between financial inclusion and financial stability. Guided by Hiebl (Citation2023), Čihák, Mare, and Melecky (Citation2021), Frączek (Citation2019), Pati and Lorusso (Citation2018), as well as Rother (Citation2007), we conducted a systematic search of the JSTOR and Google Scholar electronic databases to identify relevant articles under the specific search terms ‘the relationship between financial inclusion and financial stability’ and ‘the impact of financial inclusion and financial stability’, respectively. We did not impose a strict time period for the review. Nonetheless, the systematic search resulted in 26 academic papers spanning the period from 2015 to 2022.

Empirical research work on the relationship between financial stability and financial inclusion can broadly be segmented into three strands. First, academic papers that are of the view that financial inclusion will enhance financial stability (20 out of 26). Second, studies that support the view that financial inclusion will lead to financial instability (5 out of 26). Third, studies that have produced conflicting and thus inconclusive findings on the relationship between financial inclusion and financial stability (1 out of 26). summarizes the empirical findings on the impact of financial inclusion on financial stability. The literature shows that the concepts of financial inclusion and stability are multi-faceted and given aspects such as country specificities and data availability, various proxies have been used to capture these concepts.

Table 5. Summary of empirical studies reflecting relationship between financial inclusion and banking sector stability.

5. Discussion of the Empirical Literature

This section offers a comprehensive discussion of the empirical literature on the relationship between financial inclusion and financial stability. The discussion underscores the methodological issues and nature of results. This allows for recognizing overlaps and policy lessons while also identifying any gaps in the empirical literature to be closed in future studies.

The studies reviewed fall under the three general strands of empirical literature (i.e. those that find positive, negative, and inconclusive relationships between financial inclusion and financial stability, respectively) and cover advanced, developing, and emerging market economies. In most cases, the distance to default, as measured by bank Z-scores is a widely used proxy for financial stability. On the same token, some studies use banks’ non-performing loans, and the percentage of bank credit to bank deposits as other possible measures of stability in the financial sector. Financial inclusion proxies usually encompass use, access, and cost variables, with access (i.e. number of automatic teller machines (ATMs) per 100,000 adults or per 1000 km square; number of bank branches per 100,000 adults or per 1000 km square) and use (i.e. percentage of adults with at least one type of regulated deposit account) proxies being the most popular. Control variables included in the models vary across studies but mostly include a measure of income, such as the real GDP or real GDP per capita and a measure of price stability such as the consumer price index. In the multi-country studies, the preferred econometric technique is broadly a dynamic panel equation relative to a static panel model.

Across the studies that point to a positive impact of financial inclusion on stability, the transmission channels are generally consistent with the institutional theory (Meyer and Rowan Citation1977; DiMaggio and Powell Citation1983), which proposes that financial inclusion initiatives should increase the efficiency of financial resources and financial intermediation. This, in turn, should improve financial stability, given that a country builds a strong financial infrastructure and strengthens the regulation and supervision of the financial sector. The majority of the studies underscore that increasing financial services and products such as lending to the previously unbanked (i.e. low-income households or SMEs) can expand bank assets and reduce the relative exposure to any single borrower in the overall portfolio, thus, reducing the volatility of the loan book and the propensity of nonperforming loans as well as the risk of default, which will translate into greater financial stability. Similarly, higher levels of financial inclusion increase banks’ deposit base and stability by facilitating the growth of many small deposits as part of the banks’ stable funding. Additionally, improved financial inclusion supports a more formal financial system that improves the functioning of monetary policy and by extensions supports financial stability.

Regarding the negative impacts of financial inclusion on financial stability, the main argument advanced in the studies aligns with the extreme financial inclusion theory (Morawetz Citation1908), such that, financial stability can be jeopardized when access and use of financial services is irresponsibly promoted to economic agents regardless of their level of income or level of risk (Morawetz Citation1908; Hakimi, Boussaada, and Karmani Citation2022; Le, Chuc, and Taghizadeh-Hesary Citation2019; Čihák, Mare, and Melecky Citation2016; Koudalo and Toure Citation2023). The empirical evidence generally identified that a rapid increase in financial inclusion could lead to an erosion of financial institutions’ lending standards and an increase in their reputational risks if functions such as the assessment of the credit worthiness of smaller borrowers are outsourced. Again, as more financial service providers, such as the microfinance institutions (MFIs) enter the system, this will result in an expansion of the overall credit base and may lead to challenges in credit assessment. Inadequate credit assessment will increase the risks of credit default and bank liquidity problems. If the MFIs are not regulated and supervised properly, the integrity of the entire financial system will become compromised and result in financial instability.

There are currently not many empirical studies that provide evidence for the conclusion that financial inclusion has mixed or inconclusive effects on financial stability. The studies that point in this direction generally contend that programs aimed at expanding financial inclusion, which increase bank deposit bases, have been shown to increase financial stability, on one hand. On the other hand, they also conclude that lowering lending rules and significantly increasing the pool of potential borrowers might lead to greater dangers to the financial system and the economy. Furthermore, depending on the sort of financial inclusion initiative, the research suggests that increased financial inclusion outcomes may have favorable or unfavorable effects on financial stability.

Considering all the empirical studies reviewed, we identified four major gaps as well as recommendation for future research. First, current studies do not always present a unified theoretical approach or conceptual framework to explain the nature of the relationship between financial inclusion and financial stability (see; Khan et al. Citation2022; Siddik, Alam, and Kabiraj Citation2018; Morgan and Pontines Citation2018). The implication is that the link between financial stability and financial inclusion is often purported and suggested without this being grounded in concrete theory. Future studies can address this gap by clearly incorporating credible theory such as the institutional theory (Meyer and Rowan Citation1977; DiMaggio and Powell Citation1983) and the extreme financial inclusion theory (Morawetz Citation1908), to explain the channels through which financial inclusion could impact financial stability.

Second, of the limited (albeit growing) number of empirical studies conducted, there is evidence of divergent views on the impact of financial inclusion on financial stability. Studies that support a positive relationship between financial inclusion and financial stability include Amatus and Alireza (Citation2015) as well as Morgan and Pontines (Citation2018), while those that support a negative relationship include Čihák, Mare, and Melecky (Citation2016); Mendoza, Quadrini, and Rios-Rull (Citation2009); Al-Smadi Citation2018. Some studies, including Frączek (Citation2019), Boachie, Aawaar, and Domeher (Citation2021) as well as Matsebula and Sheefeni (Citation2022) provide inconclusive results on the inclusion-stablity relationship. One possible reason for this may be the lack of non-uniformity in the use of inclusion and stability proxies across studies (See; Al-Smadi Citation2018; Čihák, Mare, and Melecky Citation2016; Morgan and Pontines Citation2018). Another reason, especially in multi-country studies within and across regions, could be the failure to account for the possibility of panel cross-sectional dependence (see Brei, Gadanecz, and Mehrotra Citation2020; Al-Smadi Citation2018; Čihák, Mare, and Melecky Citation2016; Morgan and Pontines Citation2018; Ahamed and Mallick Citation2019; Jima and Makoni Citation2023). This general lack of consensus implies that more work still needs to be done to provide a more comprehensive conclusion. Future studies could expand on exisiting work by using composite indicators of inclusion and stablity and leveraging the latest data vintages and more robust empirical techniques.

Third, most studies review financial inclusion's impact on average financial stability across countries, neglecting its effects at low or high levels of financial stability, thereby providing a narrow perspective on the effects of financial inclusion. In this way, past studies estimating the influence of financial inclusion on financial stability have relied on classic regression techniques that focus on the mean impacts of financial inclusion on financial stability, ignoring the effect of inclusion on stability across the entire conditional distribution (see Matsebula and Sheefeni Citation2022; Anthony-Orji et al. Citation2019; Al-Smadi Citation2018; Neaime and Gaysset Citation2018; Jungo, Madaleno, and Botelho Citation2022; Jima and Makoni Citation2023). Future studies can look to complement existing studies by examining the impact of financial inclusion on financial stability throughout the conditional distribution, while controlling for unobserved individual country heterogeneity. For policy makers, this is useful because it enables a nonlinear analysis of the relationship between financial inclusion and financial stability with a focus on how policy can be formulated across different levels of financial stability, and not just the mean.

Fourth, of the few studies that examine the relationship between financial inclusion and financial stability in SSA countries, they often fail to account for the economic development context or the impact of financial inclusion of SMEs on financial stability, highlighting the need for more comprehensive analysis (see Aduda and Kalunda Citation2012; Amatus and Alireza Citation2015; Leigh and Mansoor Citation2016; Arora Citation2019; Jungo, Madaleno, and Botelho Citation2022). Future studies can extend on this work by providing a holistic empirical understanding of how financial inclusion (including that of SMEs) affects financial stability at the regional level and across in low income, lower-middle income and upper middle-income SSA country groups, respectively. For policy makers, the granularity brought about by income classification is beneficial for analytical and operational reasons. Analytically, income classification helps in understanding and identifying differences in developmental achievements and processes within countries. Operationally, the classification of countries by income informs better tailoring of policies to country specific circumstances on the basis of evidence.

6. Conclusion

This section concludes the study, and offers policy recommendations for public, and identifies potential topics for further investigation.

6.1. Summary of Findings

Our study discovered that the concept of financial inclusion lacks a single, accepted definition. According to various sources (Gadanecz and Tissot Citation2017; Amidžic, Massara, and Mialou Citation2014; Sahay et al. Citation2015), financial inclusion can be generally explained as the process of offering businesses and households easily accessible, reasonably priced, safe, efficient, transparent, and high-quality financial products and services while ensuring efficient operation of the financial system. In a similar vein, financial stability lacks a consensus definition. Generally, a stable financial system is one that can effectively manage risks, allocate resources, preserve employment, and get rid of price movements that cause instability. It also guarantees self-correction and stability, preventing adverse occurrences from disrupting the economy (Schinasi Citation2004; World Bank Citation2015; Gadanecz and Jayaram Citation2008; Jeanneau Citation2014).

In our overview of the theoretical literature on financial inclusion and stability, we provide a synthesis of the potential transmission channels that explain the positive as well as negative impact of financial inclusion on stability, from a theoretical perspective. Our study discovers that the theoretical transmission channels that explain the positive effects of financial inclusion on financial stability are broadly enshrined in the institutional theory (Meyer and Rowan Citation1977; DiMaggio and Powell Citation1983), wherein financial inclusion initiatives are posited to foster greater resource and financial intermediation efficiency, which in turn enhances financial stability provided that a nation establishes robust financial infrastructure and strengthened financial sector regulation and supervision. The theoretical transmission channels that explain the adverse impact of financial inclusion on financial stability can generally be captured through the Extreme financial inclusion (EFI) theory (Morawetz Citation1908). EFI exists when economic agents are given access to the formal financial sector and its range of products and services, regardless of their level of income or level of risk (Cull, Demirgüç-Kunt, and Lyman Citation2012; Ahamed and Mallick Citation2019; Frączek Citation2019; Danisman and Tarazi Citation2020; Feghali, Mora, and Nassif Citation2021).

When exploring the range of empirical evidence from studies that evaluate the influence of financial inclusion on financial stability, our study finds important overlaps and gaps. Empirical studies to date offer divergent views on the financial inclusion and financial stability nexus, a dispensation that may be due to country specificities, the multi-faceted nature of financial inclusion and stability or the seldom uniform use of proxies to capture these concepts in the literature. The studies reviewed fall under the three general strands of empirical literature (i.e. positive, negative, and inconclusive relationships between financial inclusion and financial stability, respectively). Financial stability is often measured by bank Z-scores, non-performing loans, and credit to bank deposits. Financial inclusion proxies include use, access, and cost variables. Control variables include income and price stability. In multi-country studies, a dynamic panel equation is preferred over a static panel model. Across the studies that conclude on a positive impact of financial inclusion on financial stability, the transmission channels are generally consistent with the institutional theory (Meyer and Rowan Citation1977; DiMaggio and Powell Citation1983). Regarding the negative impacts of financial inclusion on financial stability, empirical studies that support this conclusion align with the extreme financial inclusion theory (Morawetz Citation1908),

6.2. Recommendations for Policy

Despite the absence of universally recognized definitions for financial inclusion and financial stability, it is advised that authorities leverage the findings of our study to recognize and incorporate the fundamental characteristics of the two concepts to develop country and/or regional specific definitions for the terms. This can be used to more effectively inform national financial sector policies that seek to efficiently promote financial inclusion and financial stability while balancing the trade-offs between them.

It is recommended that policy makers take advantage of the study's thorough review of the theoretical and empirical literature of the linkage between financial inclusion and financial stability and use it as a conceptual framework to explain the transmission channels of the relationship between financial inclusion and financial stability, given that the majority of empirical studies of this relationship lack a cohesive structure that integrates and unifies divergent views from different studies. This will facilitate the development of hypotheses, the identification of pertinent variables, and the establishment of conceptual relationships, all of which will aid in organizing and directing the policy-making process. It will also serve as a foundation for data interpretation, analysis, conclusion-making, and recommendation-making.

6.3. Limitations of Reviewed Studies and Suggested Areas for Future Research

Four key gaps are observable in the empirical studies that investigate the impact off financial inclusion on financial stability. First, current studies do not always present a unified theoretical approach or conceptual framework to explain the nature of the relationship between financial inclusion and financial stability. Future studies can address this gap by clearly incorporating credible theory such as the institutional theory (Meyer and Rowan Citation1977; DiMaggio and Powell Citation1983) and the extreme financial inclusion theory (Morawetz Citation1908), to explain the channels through which financial inclusion could impact financial stability. Second, there is a lack of consensus on the relationship between financial inclusion and financial stability, with some studies suggesting a positive relationship and others arguing for a negative one. This may be due to differences in financial inclusion and stability proxies or inappropriate methodology to efficiently capture single or multi-country dynamics. Future research could use composite indicators and more robust empirical techniques. Third, most studies focus on financial inclusion's impact on average financial stability across countries, neglecting its effects at low or high levels of financial stability. Future research should examine the impact of financial inclusion on financial stability across conditional distributions., while controlling for unobserved individual country heterogeneity. Fourth, few studies on the relationship between financial inclusion and financial stability, especially those on SSA countries consider economic development contexts or the impact of financial inclusion of SMEs on financial stability, indicating the need for more comprehensive analysis.

A limitation of this review is that our search for studies was limited to those obtained through JSTOR and Google Scholar, which may have resulted in fewer papers that met the review's eligibility requirements. We also limited our examination to English-language publications. Although this search criteria affected the choice of countries or regions included in the literature review, the study was deliberate to ensure that the studies reviewed covered both developing and developed countries and/or regions. Furthermore, we used research published in academic journals as an indicator of quality rather than attempting to do a quality evaluation of the chosen studies. We believe that credible academic journals’ peer review process offers a sufficient and effective indicator of quality.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 The selection of the SSBs was made in light of their innovative and persistently influential work in the field of financial inclusion around the world.

References

- Abdulkarim, F. M., and H. S. Ali. 2019. “Financial Inclusions, Financial Stability, and Income Inequality in OIC Countries: A GMM and Quantile Regression Application.” Journal of Islamic Monetary Economics and Finance 5 (2): 1–18. https://doi.org/10.21098/jimf.v5i2.1069

- Abosedra, S., A. Fakih, S. Ghosh, and K. Kanjilal. 2023. “Financial Development and Business Cycle Volatility Nexus in the UAE: Evidence from non-Linear Regime-Shift and Asymmetric Tests.” International Journal of Finance & Economics 28 (3): 2729–2741. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijfe.2560

- Aduda, Josiah, and Elizabeth Kalunda. 2012. “Financial Inclusion and Financial Sector Stability with Reference to Kenya: A Review of Literature.” Journal of Applied Finance & Banking 2: 95–120.

- Ahamed, M. M., and S. K. Mallick. 2019. “Is Financial Inclusion Good for Bank Stability? International Evidence.” Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization 157: 403–427. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jebo.2017.07.027

- Ahmad, D. 2018. “Financial Inclusion and Financial Stability: Survey of the Nigeria’s Financial System.” International Journal of Research in Finance and Management 1 (2): 47–54. https://doi.org/10.33545/26175754.2018.v1.i2a.15

- Al-Smadi, M. O. 2018. “The Role of Financial Inclusion in Financial Stability: Lesson from Jordan.” Banks and Bank Systems 13 (4): 31–39. https://doi.org/10.21511/bbs.13(4).2018.03

- Allen, F., A. Demirgüç-Kunt, A. L. Klapper, and M. S. Martinez-Peria. 2016. “The Foundations of Financial Inclusion: Understanding Ownership and use of Formal Accounts.” Journal of Financial Intermediation 27: 1–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfi.2015.12.003.

- Allen, W. A., and G. Wood. 2006. “Defining and Achieving Financial Stability.” Journal of Financial Stability 2 (2): 152–172. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfs.2005.10.001

- Alliance for Financial Inclusion. 2017. “Defining Financial Inclusion. Accessed March March, 2022. https://www.afi-global.org/wp-content/uploads/publications/2017-07/FIS_GN_28_AW_digital.pdf.

- Amatus, H., and N. Alireza. 2015. “Financial Inclusion and Financial Stability in Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA).” International Journal of Social Sciences 36 (1): 2305–4557.

- Amidžic, G., A. Massara, and A. Mialou. 2014. “Assessing Countries’ Financial Inclusion Standing—A new Composite Index.” IMF Working Paper, No. 14/36, Washington DC.

- Anarfo, E. B., M. Ntuli, S. S. Boateng, and J. Y. Abor. 2022. “Financial Inclusion, Banking Sector Development, and Financial Stability in Africa.” In The Economics of Banking and Finance in Africa, edited by J. Y. Abor and C. K. D. Adjasi, 101–134. Palgrave Macmillan Studies in Banking and Financial Institutions. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-04162-4_4

- Anthony-Orji, O. I., A. Orji, J. E. Ogbuabor, and E. O. Nwosu. 2019. “Do Financial Stability and Institutional Quality Have Impact on Financial Inclusion in Developing Economies? A new Evidence from Nigeria.” International Journal of Sustainable Economy 11 (1): 18–40. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJSE.2019.096541

- Arayssi, M., A. Fakih, and M. Kassem. 2019. “Government and Financial Institutional Determinants of Development in MENA Countries.” Emerging Markets Finance and Trade 55 (11): 2473–2496. https://doi.org/10.1080/1540496X.2018.1507907

- Arora, R. 2019. The Links Between Financial Inclusion and Financial Stability: A Study of BRICS. The Oxford Handbook of BRICS and Emerging Economies. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

- Banna, H., and M. R. Alam. 2021. “Impact of Digital Financial Inclusion on ASEAN Banking Stability: Implications for the Post-Covid-19 era.” Studies in Economics and Finance 38 (2): 504–523. https://doi.org/10.1108/SEF-09-2020-0388

- Barik, R., and A. K. Pradhan. 2021. “Does Financial Inclusion Affect Financial Stability: Evidence from BRICS Nations?” The Journal of Developing Areas 55 (1): 342–356. https://doi.org/10.1353/jda.2021.0023

- Beck, T., and O. De Jonghe. 2013. “Lending Concentration, Bank Performance and Systemic Risk: Exploring Cross-Country Variation.” World Bank Policy Research Working Paper, (6604).

- Beck, T., A. Demirgüç-Kunt, and R. Levine. 2007. “Finance, Inequality and the Poor.” Journal of Economic Growth 12 (1): 27–49. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10887-007-9010-6

- Berlin, M., and L. J. Mester. 1999. “Deposits and Relationship Lending.” The Review of Financial Studies Fall 1999 12 (3): 579–607.

- Boachie, R., G. Aawaar, and D. Domeher. 2021. “Relationship Between Financial Inclusion, Banking Stability and Economic Growth: A Dynamic Panel Approach.” Journal of Economic and Administrative Sciences 39 (3): 655–670. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1108/JEAS-05-2021-0084.

- Brei, M., B. Gadanecz, and A. Mehrotra. 2020. “SME Lending and Banking System Stability: Some Mechanisms at Work.” Emerging Markets Review 43: 100676. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ememar.2020.100676

- Carbó, S., E. P. M. Gardener, and P. Molyneux. 2005. Financial Exclusion. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Chen, F. W., Y. Feng, and W. Wang. 2018. “Impacts of Financial Inclusion on non-Performing Loans of Commercial Banks: Evidence from China.” Sustainability 10 (9): 3084. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10093084

- Čihák, Martin, and Heiko Hesse. 2010. “Islamic Banks and Financial Stability: An Empirical Analysis.” Journal of Financial Services Research 38 (2-3): 95–113. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10693-010-0089-0

- Čihák, M., D. S. Mare, and M. Melecky. 2016. “The Nexus of Financial Inclusion and Financial Stability: A Study of Trade-Offs and Synergies.” World Bank Policy Research Working Paper 7722.

- Čihák, M., D. S. Mare, and M. Melecky. 2021. “Financial Inclusion and Stability: Review of Theoretical and Empirical Links.” The World Bank Research Observer 36 (2): 197–233. https://doi.org/10.1093/wbro/lkaa006

- Cull, R., A. Demirgüç-Kunt, and T. Lyman. 2012. Financial Inclusion and Stability: What Does Research Show? (No. 9443). Washington, DC: The World Bank Group.

- Cull, R., T. Ehrbeck, and N. Holle. 2014. “Financial Inclusion and Development: Recent Impact Evidence.” CGAP (Consultative Group to Assist the Poor) Focus Note 9/2014, Washington, DC.

- Danisman, G. O., and A. Tarazi. 2020. “Financial Inclusion and Bank Stability: Evidence from Europe.” The European Journal of Finance 26 (18): 1842–1855. https://doi.org/10.1080/1351847X.2020.1782958

- Dell’Ariccia, G., and R. Marquez. 2006. “Competition among Regulators and Credit Market Integration.” Journal of Financial Economics 79 (2): 401–430. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfineco.2005.02.003

- Demirgüç-Kunt, A., and L. Klapper. 2013. “Measuring Financial Inclusion: Explaining Variation in Use of Financial Services Across and Within Countries.” Brookings Papers on Economic Activity 2013 (1): 279–340. https://doi.org/10.1353/eca.2013.0002

- Demirgüç-Kunt, A., L. Klapper, and D. Singer. 2017. “Financial Inclusion and Inclusive Growth: A Review of Recent Empirical Evidence.” World Bank Policy Research Working Paper, No. 8040, Washington, DC.

- Dienillah, A. A., L. Anggraeni, and S. Sahara. 2018. “Impact of Financial Inclusion on Financial Stability Based on Income Group Countries.” Buletin Ekonomi Moneter Dan Perbankan 20 (4): 429–442. https://doi.org/10.21098/bemp.v20i4.859

- DiMaggio, P. J., and W. W. Powell. 1983. “The Iron Cage Revisited: Institutional Isomorphism and Collective Rationality in Organizational Fields.” American Sociological Review 48 (2): 147–160. https://doi.org/10.2307/2095101

- Duvendack, M., and P. Mader. 2018. “Impact of Financial Inclusion in low- and Middle-Income Countries: A Systematic Review of Reviews.” Campbell Systematic Reviews 14 (1): 1–58. https://doi.org/10.1002/CL2.211

- Espinosa-Vega, M. A., M. K. Shirono, M. H. C. Villanova, M. Chhabra, M. B. Das, and M. Y. Fan. 2020. Measuring Financial Access: 10 Years of the IMF Financial Access Survey. Washington, DC: International Monetary Fund.

- Eton, M., F. Mwosi, and C. Okello-Obura. 2021. “Financial Inclusion and the Growth of Small Medium Enterprises in Uganda: Empirical Evidence from Selected Districts in Lango sub-Region.” Journal of Innovation 10: 23. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13731-021-00168-2.

- European Central Bank. 2012. “Financial Stability Review December 2012.” Accessed September 19, 2022. https://www.ecb.europa.eu/pub/pdf/fsr/financialstabilityreview201212en.pdf.

- Feghali, K., N. Mora, and P. Nassif. 2021. “Financial Inclusion, Bank Market Structure, and Financial Stability: International Evidence.” The Quarterly Review of Economics and Finance 80: 236–257. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.qref.2021.01.007

- Frączek, B. 2019. “Relationships Between Financial Inclusion and Financial Stability and Economic Growth—The Opportunity or Threat for Monetary Policy?” In Multiple Perspectives in Risk and Risk Management: ERRN 8th European Risk Conference 2018, Katowice, Poland, September 20-21 (pp. 261–278). Springer International Publishing.

- Gadanecz, B., and K. Jayaram. 2008. “Measures of Financial Stability-A Review.” Irving Fisher Committee Bulletin 31 (1): 365–383.

- Gadanecz, B., and B. Tissot. 2017. Measures of Financial Inclusion–A Central Bank Perspective, 190-196. Jakarta, Indonesia: Statistics Department, Bank of Indonesia.

- García, M. J. R., and M. José. 2016. “Can Financial Inclusion and Financial Stability go Hand in Hand.” Economic Issues 21 (2): 81–103.

- Ghassibe, M., M. Appendino, and S. E. Mahmoudi. 2019. “SME Financial Inclusion for Sustained Growth in the Middle East and Central Asia.” IMF Working Papers, 2019(209).

- Hakimi, A., R. Boussaada, and M. Karmani. 2022. “Are Financial Inclusion and Bank Stability Friends or Enemies? Evidence from MENA Banks.” Applied Economics 54 (21): 2473–2489. https://doi.org/10.1080/00036846.2021.1992342

- Han, R., and M. Melecky. 2013. “Financial Inclusion for Financial Stability: Access to Bank Deposits and the Growth of Deposits in the Global Financial Crisis.” World Bank Policy Research Working Paper, (6577).

- Hannig, A., and S. Jansen. 2010. “Financial Inclusion and Financial Stability: Current Policy Issues.” ADBI Working Paper Series, No. 259, Asian Development Bank Institute, Manila, Philippines.

- Hawkins, P. 2006. Financial Access and Financial Stability. in Central Banks and the Challenge of Development, 65–79. Basel, Switzerland: Bank for International Settlements.

- Hiebl, M. R. 2023. “Sample Selection in Systematic Literature Reviews of Management Research.” Organizational Research Methods 26 (2): 229–261. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094428120986851

- Huong, N. T. T. 2018. “The Impact of Financial Inclusion on Monetary Policy: A Case Study in Vietnam.” Journal of Economics and Development 20 (2): 5–22. https://doi.org/10.33301/JED-P-2018-20-01-01

- Igan, M. D., and M. Pinheiro. 2011. Credit Growth and Bank Soundness: Fast and Furious? Washington, DC: International Monetary Fund.

- International Monetary Fund. 2008. Financial Soundness Indicators: Compilation Guide. Washington, DC: International Monetary Fund.

- Jeanneau, S. 2014. “Financial Stability Objectives and Arrangements–What's New?.” BIS Paper, (76e).

- Jima, M. D., and P. L. Makoni. 2023. “Financial Inclusion and Economic Growth in Sub-Saharan Africa—A Panel ARDL and Granger Non-Causality Approach.” Journal of Risk and Financial Management 16 (6): 299. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm16060299

- Jungo, J., M. Madaleno, and A. Botelho. 2022. “The Effect of Financial Inclusion and Competitiveness on Financial Stability: Why Financial Regulation Matters in Developing Countries?” Journal of Risk and Financial Management 15 (3): 122. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm15030122

- Kamal, A., T. Hussain, and M. M. S. Khan. 2021. “Impact of Financial Inclusion and Financial Stability: Empirical and Theoretical Review.” Liberal Arts and Social Sciences International Journal (LASSIJ) 5 (1): 510–524. https://doi.org/10.47264/idea.lassij/5.1.33

- Khan, H. R. 2011. “Financial Inclusion and Financial Stability: Are They two Sides of the Same Coin.” Address by Shri HR Khan, Deputy Governor of the Reserve Bank of India, at BANCON, 1–12.

- Khan, I., I. Khan, A. U. Sayal, and M. Z. Khan. 2022. “Does Financial Inclusion Induce Poverty, Income Inequality, and Financial Stability: Empirical Evidence from the 54 African Countries?” Journal of Economic Studies 49 (2): 303–314. https://doi.org/10.1108/JES-07-2020-0317

- Koudalo, Y. M., and M. Toure. 2023. “Does Financial Inclusion Promote Financial Stability? Evidence from Africa.” Cogent Economics & Finance 11 (2): 2225327. https://doi.org/10.1080/23322039.2023.2225327

- Laeven, L., and R. Levine. 2009. “Bank Governance, Regulation and Risk Taking.” Journal of Financial Economics 93 (2): 259–275. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfineco.2008.09.003

- Le, T. H., A. T. Chuc, and F. Taghizadeh-Hesary. 2019. “Financial Inclusion and its impact on Financial Efficiency and sustainability: Empirical Evidence from Asia.” Borsa Istanbul Review 19 (4): 310–322. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bir.2019.07.002

- Leigh, L., and A. Mansoor. 2016. “Financial Inclusion and stability in Africa’s Middle-income countries.” In Africa on the Move: Unlocking the Potential of Small MiddleIncome States, edited by Lamin Leigh and Ali Mansoor, 107–129. Washington, DC: International Monetary Fund.

- Lenka, S. K., and A. K. Bairwa. 2016. “Does Financial Inclusion Affect Monetary Policy in SAARC countries?” Cogent Economics & Finance 4 (1): 1127011. https://doi.org/10.1080/23322039.2015.1127011

- Leyshon, A., and N. Thrift. 1995. “Geographies of Financial Exclusion: Financial Abandonment in Britain and the United States.” Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers 20 (3): 312–341. https://doi.org/10.2307/622654

- Matsebula, V., and J. P. Sheefeni. 2022. “An Analysis of the Relationship Between Financial Inclusion and Financial Stability in South Africa.” Global Journal of Economics and Business 12 (5): 637–648. https://doi.org/10.31559/GJEB2022.12.5.8

- Mbutor, M. O., and I. A. Uba. 2013. “The Impact of Financial Inclusion on Monetary Policy in Nigeria.” Journal of Economics and International Finance 5 (8): 318–326. https://doi.org/10.5897/JEIF2013.0541

- Mehrotra, A., and G. V. Nadhanael. 2016. “Financial Inclusion and monetary Policy in emerging Asia.” Financial Inclusion in Asia: Issues and Policy Concerns, 93–127. https://doi.org/10.1057/978-1-137-58337-6_4

- Mehrotra, A. N., and J. Yetman. 2014. “Financial Inclusion and Optimal Monetary Policy.” Bank of International Settlements Working Papers, No. 476. (pp. 1–26).

- Mehrotra, A. N., and J. Yetman. 2015. “Financial Inclusion-issues for Central Banks.” BIS Quarterly Review, March.

- Mendoza, E. G., V. Quadrini, and J. V. Rios-Rull. 2009. “Financial Integration, financial Development, and global Imbalances.” Journal of Political Economy 117 (3): 371–416. https://doi.org/10.1086/599706

- Meyer, J. W., and B. Rowan. 1977. “Institutionalized Organizations: Formal Structure as Myth and Ceremony.” American Journal of Sociology 83 (2): 340–363. https://doi.org/10.1086/226550

- Morawetz, V. 1908. “Evils of Excessive Credit Expansion.” Journal of Accountancy (pre-1986) 5 (000005): 345–354.

- Morgan, P. J., and V. Pontines. 2018. “Financial Stability and Financial Inclusion: The Case of SME Lending.” The Singapore Economic Review 63 (01): 111–124. https://doi.org/10.1142/S0217590818410035

- Naceur, S. B., B. Candelon, and Q. Lajaunie. 2019. “Taming Financial Development to Reduce Crisis.” Emerging Markets Review 40: 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ememar.2019.05.003

- Neaime, S., and I. Gaysset. 2018. “Financial Inclusion and Stability in MENA: Evidence from Poverty and Inequality.” Finance Research Letters 24: 230–237. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.frl.2017.09.007

- Negm, A. 2021. “The Effect of Financial Inclusion on Financial stability in the SME’s From Bankers’ Viewpoint ‘The Egyptian Case’ (September 5, 2021).” SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3917928.

- Okpara, J. O. 2011. “Factors Constraining the Growth and Survival of SMEs in Nigeria: Implications for Poverty Alleviation.” Management Research Review 34 (2): 156–171. https://doi.org/10.1108/01409171111102786

- Operana, B. 2016. “Financial Inclusion and Financial Stability in the Philippines.” Published Masters Dissertation. Graduate School of Public Policy (GraSPP). The University.

- Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development. 2013. “Financial Literacy and Inclusion.” Accessed March 26, 2022. https://www.oecd.org/daf/fin/financial-education/TrustFund2013_OECD_INFE_Fin_Lit_and_Incl_SurveyResults_by_Country_and_Gender.pdf.

- Ozili, P. K. 2018. “Impact of Digital Finance on Financial Inclusion and Stability.” Borsa Istanbul Review 18 (4): 329–340. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bir.2017.12.003

- Ozili, P. K. 2020. “Theories of Financial Inclusion.” In Uncertainty and Challenges in Contemporary Economic Behaviour (Emerald Studies in Finance, Insurance, and Risk Management), edited by E. Özen, and S. Grima, 89–115. Bingley: Emerald Publishing Limited.

- Ozili, P. K. 2021. “Financial Inclusion Research Around the World: A Review.” In Forum for Social Economics 50 (4): 457–479. https://doi.org/10.1080/07360932.2020.1715238

- Pal, S., and I. Bandyopadhyay. 2022. “Impact of Financial Inclusion on Economic Growth, Financial Development, Financial Efficiency, Financial Stability, and Profitability: An International Evidence.” SN Business & Economics 2 (9): 139. https://doi.org/10.1007/s43546-022-00313-3

- Pati, D., and L. N. Lorusso. 2018. “How to Write a Systematic Review of the Literature.” HERD: Health Environments Research & Design Journal 11 (1): 15–30. https://doi.org/10.1177/1937586717747384

- Pesqué-Cela, V., L. Tian, D. Luo, D. Tobin, and G. Kling. 2021. “Defining and Measuring Financial Inclusion: A Systematic Review and Confirmatory Factor Analysis.” Journal of International Development 33 (2): 316–341. https://doi.org/10.1002/jid.3524

- Petersen, M. A., and R. G. Rajan. 1995. “The Effect of Credit Market Competition on Lending Relationships.” The Quarterly Journal of Economics 110 (2): 407–443. https://doi.org/10.2307/2118445

- Pham, M. H., and T. P. L. Doan. 2020. “The Impact of Financial Inclusion on Financial Stability in Asian Countries.” The Journal of Asian Finance, Economics and Business 7 (6): 47–59. https://doi.org/10.13106/jafeb.2020.vol7.no6.047

- Prasad, E. 2010. “Financial Sector Regulation and Reforms in Emerging Markets: An Overview.” NBER Working Paper No. 16428. National Bureau of Economic Research, Cambridge, MA. https://www.nber.org/papers/w16428.

- Queralt, J. 2016. “A Human Right to Financial Inclusion.” In Ethical Issues in Poverty Alleviation, edited by H. P. Gaisbauer, G. Schweiger, and C. Sedmak, 77–92. Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing.

- Rahman, A. 2014. The Mutually Supportive Relationship Between Financial Inclusion and Financial Stability, AfiViewpoints Issue 1. Bangkok: Alliance for Financial Inclusion.

- Rosengren, E. S. 2011. “Defining Financial Stability, and Some Policy Implications of Applying the Definition.” In Keynote Remarks at the Stanford Finance Forum, edited by Federal Reserve Bank of Boston, 1–15. Boston, MA: Graduate School of Business, Stanford University.

- Rother, E. T. 2007. “Systematic Literature Review X Narrative Review.” Acta Paulista de Enfermagem 20 (2): v-vi. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0103-21002007000200001

- Saha, M., and K. D. Dutta. 2021. “Nexus of Financial Inclusion, Competition, Concentration and Financial Stability: Cross-Country Empirical Evidence.” Competitiveness Review: An International Business Journal 31 (4): 669–692. https://doi.org/10.1108/CR-12-2019-0136

- Saha, M., and K. D. Dutta. 2022. “Do Macroprudential Regulations Condition the Role of Financial Inclusion for Ensuring Financial Stability? Cross-Country Perspective.” International Journal of Emerging Markes 19 (7): 1769–1803.

- Sahay, M. R., M. Čihák, M. P. N'Diaye, M. A. Barajas, M. S. Mitra, M. A. Kyobe, and M. R. Yousefi. 2015. Financial Inclusion: Can it Meet Multiple Macroeconomic Goals? Washington, DC: International Monetary Fund.

- San Jose, A., and A. Georgiou. 2008. “Financial Soundness Indicators (FSIs): Framework and Implementation.” IFC Bulletin 31: 277–282.

- Schinasi, G. 2004. Defining Financial Stability (No. 2004/187). International Monetary Fund.

- Sethy, S. K., and P. Goyari. 2022. “Financial Inclusion and Financial Stability Nexus Revisited in South Asian Countries: Evidence from a new Multidimensional Financial Inclusion Index.” Journal of Financial Economic Policy 14 (5): 674–693.

- Siddik, M., N. Alam, and S. Kabiraj. 2018. “Does Financial Inclusion Induce Financial Stability? Evidence from Cross-Country Analysis.” Australasian Accounting, Business and Finance Journal 12 (1): 34–46.

- Vo, D. H., N. T. Nguyen, and L. T. H. Van. 2021. “Financial Inclusion and Stability in the Asian Region Using Bank-Level Data.” Borsa Istanbul Review 21 (1): 36–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bir.2020.06.003

- Wang, R., and H. R. Luo. 2022. “How Does Financial Inclusion Affect Bank Stability in Emerging Economies?” Emerging Markets Review 51: 100876. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ememar.2021.100876

- World Bank. 2015. “How to Measure Financial Inclusion.” Accessed March 16, 2022. https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/financialinclusion/brief/how-to-measure-financial-inclusion.

- World Bank. 2018. “UFA2020 Overview: Universal Financial Access by 2020.” Accessed July 18, 2022. https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/financialinclusion/brief/achieving-universal-financial-access-by-2020.

- Yoshino, N., and P. J. Morgan. 2018. “Financial Inclusion, Financial Stability, and Income Inequality: Introduction.” The Singapore Economic Review 63 (01): 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1142/S0217590818020022