Abstract

Media practitioners and policy makers are calling for more public support to facilitate the digital transformation of local journalism. However, newer academic literature focuses on explaining why public support for local media has become a necessity from a market failure and societal point of view. Almost no attention is dedicated to the question which known public support instruments might be considered as helpful from the perspective of local media and their digital transformation strategies. Therefore, this study draws on strategic path dependence theory and investigates how local media’s perceptions of innovation constraints (i.e., lock-in mechanisms), their innovation status (i.e., lock-ins) and their preferences for public support instruments to enable innovation (i.e., public un-lock mechanisms) differ depending on the type of strategy. Four strategies are compared: two content strategies (multimedia formats and artificial intelligence applications) as well as two commercial strategies (revenue diversification and digital payment models). Data about the four strategies are collected with an online survey of local media, which operate in the Swiss Canton of St. Gallen. The findings show significant differences between the investigated strategies and suggest a differentiated approach to public support of local media in the digital age.

Findings across media markets indicate that local media’s circulations and advertising revenues are decreasing. In fact, according to Wahl-Jorgensen, the “greatest challenge facing journalism today lies in the collapse of local news provision” (2019, 163), which has serious consequences for local communities and, more broadly, for democratic societies (Ali Citation2016; Olsen, Pickard, et al. Citation2020).

Accordingly, local media are under pressure to find sustainable business models by adapting their commercial strategies, diversifying their revenue sources and increasing their reader-based online revenues (Hansen et al. Citation2018). Moreover, local media are challenged to transform their content strategies in order to increase the efficiency of news production and to meet the needs of local online audiences more effectively (Jenkins and Nielsen Citation2020). These transformations, however, are hindered – for instance by a lack of financial recourses and know-how (Villi et al. Citation2020).

Therefore, even in more commercialized media systems such as the US, media practitioners and policy makers are calling for more public support to facilitate the digital transformation of local journalism (Ali et al. Citation2019; Olsen, Pickard, et al. Citation2020; Pickard Citation2020). After all, according to Ali (Citation2016), local journalism is a merit good. More specifically, merit goods are “under-produced by the market and under-invested in by consumers” (107). Furthermore, “merit goods are based on a normative assumption that the good should be provided regardless of consumption habits” (107). Therefore, “[p]ositioning local journalism as a merit good provides justifications rooted in economic theory for increased regulartory support” (107).

However, newer academic literature focuses on explaining why public support for local media has become a necessity from a market failure and societal point of view. Previous research has not systematically analyzed how local media’s innovation constraints differ depending on the type of strategy and which public support instruments they perceive as suitable to facilitate strategy implementation.

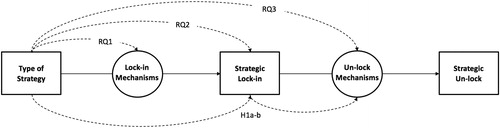

Therefore, this study draws on strategic path dependence theory and investigates how local media’s perceptions of innovation constraints, their innovation status and their preferences for public support instruments to enable innovation differ depending on the type of strategy. Strategic path dependence theory is particularly usefuly for this study because it dicsusses not only mechanisms, which constrain innovation (i.e., lock-in mechanisms) and lead to a strategic lock-in, but also mechanisms, which enable innovation (i.e., un-lock mechanisms) and facilitate a strategic un-lock. Previous studies have used strategic path dependence theory to analyse why supra-regional newspapers in Germany (Rothmann and Koch Citation2014) and regional newspapers in England (Cestino and Matthews Citation2016) have been struggling to innovate their business models. This study, in turn, investigates not only constraints but also possible enablers of strategic innovation.

More specifically, based on Mintzberg (Citation2007), we define a strategy in general as a pattern in decisions (i.e., intended strategy) and actions (i.e., implemented strategy), which serve a specific goal. Strategies are hierarchical, i.e., lower-level strategies serve higher-level strategies and goals. On the highest level, (local) news organizations pursue editorial (i.e., content) and economic (i.e., commercial) strategic goals, which are interrelated and implemented with specific content and commercial lower-level strategies (Meckel Citation1999). Accordingly, this study investigates four lower-level strategies: two content strategies, namely multimedia formats (MM) and artificial intelligence applications (AI), and two commercial strategies, namely revenue diversification (RD) and digital payment models (DP). After all, these lower-level strategies are considered to be particularly emerging fields in local journalism (Radcliffe Citation2017; Hansen et al. Citation2018; Olsen and Solvoll Citation2018b; Legg Citation2019).

More specifically, we conduct an online survey and investigate the four strategies in news organizations, which operate at the local or regional level in the Swiss Canton of St. Gallen. Switzerland has a democratic corporatist media system, and, accordingly, is characterized by relatively strong public support for media at the federal level (Künzler et al. Citation2013). However, most of the public support is dedicated to direct support of the public broadcasting media, while national and local print media are indirectly supported through VAT reduction and subsidies for newspaper distribution costs. Given the high importance of local media for the Swiss direct democracy on the one hand and their fast deteriorating economic situation on the other hand, several Cantons (i.e., member states of the Swiss Confederation) have implemented different complementary instruments to publicly support local journalism (Kanton Bern Citation2019). The Canton of St. Gallen, which consists of eight electoral districts, however, has not implemented such instruments so far, which gave reason to conduct the study in this local media market.

Beyond the importance for the Canton of St. Gallen, this study is also of broader academic interest. After all, it takes a different perspective than available literature by exploring local media’s specific needs for public support depending on the type of strategy. Thus, the insights of this study provide a starting point for an analysis of innovation constraints and targeted public support in other local media markets.

Literature Review: Digital Transformation of Local Media

Previous research has closely examined how local media transform their content and commercial strategies in the digital age. In fact, while earlier studies have investigated how local media interact with audiences (Paulussen and D’heer Citation2013; Radcliffe Citation2017; Konieczna, Hatcher, and Moore Citation2018; Nelson Citation2018; Wenzel Citation2019), more recent studies have shifted their focus towards further (online) content strategies. For instance, research findings show that MM such as podcasts and videos are becoming increasingly relevant for local media (Radcliffe Citation2017; Radcliffe, Ali, and Donald Citation2017).

Moreover, a review of projects, which were funded by Google’s Digital News Initiative, shows that local media are also increasingly applying AI for different activities of the news value chain (Kaufmann et al. Citation2019). After all, an automated identification of issues for news coverage and an automated production of news content allow increasing both efficiency and output of news production. Furthermore, the personalized distribution of news content facilitates addressing audiences’ specific needs more effectively (Diakopoulos Citation2019; Lindén and Tuulonen Citation2019; Villi et al. Citation2020).

In terms of commercial strategies, Hansen et al. (Citation2018) state that direct reader revenue must be at the center of sustainable business models of local media. As advertising cedes its position as the most relevant path to revenue, viral clicks are less alluring (Jacob Citation2019). In fact, research findings indicate that local media are increasingly shifting their strategy to focus on reader-based revenue models, i.e., DP (Hansen et al. Citation2018; Jenkins and Nielsen Citation2018; Olsen and Solvoll Citation2018b; Legg Citation2019).

The success of DP, however, depends on whether local media deliver the value that customers require. In fact, Olsen and Solvoll (Citation2018a) conclude that local media’s offerings are particularly misaligned with younger and lower income audiences. Therefore, Olsen encourages media practitioners and policy makers “to explore ways of bridging the gap between people’s perception of individual and societal worthwhileness of local news media” (2020, 521). In line with these findings, Goyanes (Citation2015) shows that US adults’ willingness to pay for online local news increases with age. Therefore, delivering the value that customers require and thereby increasing their willingness to pay becomes a crucial factor that according to Olsen, Kammer, et al. (Citation2020) has to compensate for a decrease in online traffic due to hard or soft paywalls.

However, DP – as well as further reader-based revenue sources such as donations and memberships – alone are not likely to support local news businesses by themselves. Accordingly, local media need to consider alternative revenue sources as well. In fact, Hansen et al. (Citation2018) and Schmidt (Citation2019) show that local media are indeed increasingly pursuing RD strategies, for instance based on events, educational offers, publishing services and e-commerce.

Finally, as various academic systematizations show, different types of media systems have implemented different instruments of public support for different types of (local) media (Nielsen and Linnebank Citation2011; Künzler et al. Citation2013; Ali Citation2012, Citation2017). Further studies have investigated how public support for local journalism is innovated (Lindgren, Corbett, and Hodson Citation2020; Stonbely, Weber, and Satullo Citation2020).

However, we argue that there is a lack of comparative research on how local media’s innovation constraints differ depending on a specific strategy and what public support instruments they perceive to be most suitable to enable strategy implementation. Therefore, this study draws on strategic path dependence theory and investigates how local media’s perceptions of innovation constraints as well as their preferences for public innovation enablers differ depending on the type of strategy.

Theoretical Framework: Lock-In Mechanisms, Lock-Ins and Un-Lock Mechanisms

Strategic path dependence theory explains how specific mechanisms constrain or enable strategic innovation in organizations during several phases (Schreyögg, Sydow, and Koch Citation2003; Cestino and Matthews Citation2016). In the first so-called preformation phase, the range of strategic actions is broad but nevertheless constrained by initial conditions. After all, strategic choices do not start from scratch but “reflect, at least partially, the rules and the culture making up the institution” (Schreyögg and Sydow Citation2011, 324). However, once a strategic choice is made, this choice may turn out to be an event, which sets of a self-reinforcing lock-in process.

This leads to the formation phase where one or several lock-in mechanisms kick in (Schreyögg, Sydow, and Koch Citation2003). They drive the formation of dominant action patterns and decrease the range of possible strategic actions even more. These lock-in mechanisms are based on specific (organizational) dynamics, namely commitment, learning, coordination and adaptive expectation effects.

First, commitment effects occur when actors allocate their resources to specific activities and, thereafter, are constrained to shift their efforts (Staw Citation1981). “Even in the case of warning signals indicating that the current course of action may fail […], managers are often reluctant to pull out from the initial course of action” (Schreyögg and Sydow Citation2011, 327). For instance, previous research has shown that local media are constrained to shift their efforts towards online strategies and, accordingly, argue that a lack of resources restricts innovation (Villi et al. Citation2020).

Moreover, learning effects hold that the more often an operation is performed, the more efficient a process becomes. “The operations are more skillfully performed […], which, in turn, means decreasing average costs per unit of output” (Schreyögg and Sydow Citation2011, 325). Accordingly, “the more attractive the chosen solution becomes […], the less attractive it is to switch to new learning sites” (Schreyögg and Sydow Citation2011, 325). For instance, while local journalists are “eager to learn more about” (Radcliffe, Ali, and Donald Citation2017, 41) new technologies, local media are nevertheless struggling to shift their competencies towards online strategies.

Furthermore, coordination effects build on the benefits of rule-guided behaviour, i.e., the more actors adopt and apply a specific organizational rule or routine, the more efficient the interaction is among these actors (Schreyögg and Sydow Citation2011). In such contexts, organizational structures become inflexible (Sydow, Schreyögg, and Koch Citation2009) and constrain innovation. Accordingly, news organizations, which balance out conflicting goals at the management level (Gilbert Citation2006), overcome structural inertia (Wilczek Citation2019) and set up specialized online units (Küng Citation2017), are more likely to innovate their digital products and business models.

Finally, adaptive expectation effects relate to the interactive building of preferences, i.e., the more people are expected to prefer a particular product, the more attractive it becomes (Schreyögg and Sydow Citation2011). News organizations are also confronted with such market constraints. For instance, Rothmann (Citation2013) and Rothmann and Koch (Citation2014) show that news organizations’ dependence on specific audience and advertising segments hinders the implementation of DP.

However, the intensity of a specific lock-in mechanism might depend on the type of strategy. This leads to the following research question (RQ1): How do local media’s perceptions of lock-in mechanisms differ depending on the type of strategy?

These lock-in mechanisms will eventually lead into the lock-in phase where the emerging dominant action patterns become locked in. This is reflected in the innovation status of a strategy. More specifically, even if challenged by more efficient alternatives, decision-makers will tend to stick to the strategic path and, thereby, will constrain innovation (Sydow, Schreyögg, and Koch Citation2009). This leads to the following research question (RQ2): How do local media’s lock-ins differ depending on the type of strategy?

In the un-lock phase, in turn, specific mechanisms may come into play, which will enable decision-makers to overcome commitment, learning, coordination or adaptive expectation effects and, thereby, will facilitate strategic innovation (Ericson and Lundin Citation2013). Schreyögg, Sydow, and Koch (Citation2003) identify internal and external agents who may drive strategic un-locking.

Regarding local media, we argue that public support instruments are potential external un-lock mechanisms. Two types of public support are differentiated: direct and indirect instruments (Nielsen and Linnebank Citation2011; Künzler et al. Citation2013; Ali Citation2017; Harte, Howells, and Abingdon Citation2019; Olsen, Kammer, et al. Citation2020; Murschetz Citation2020). While direct instruments support specific news organizations, indirect instruments support journalistic ecosystems. Of course, such instruments are not limited to financial resources (e.g., targeted subsidies and reduced VAT rates), which aim to mitigate commitment effects. Further instruments such as the transfer of know-how (e.g., through education and training) or the fostering of collaborations (e.g., through enabling networks and infrastructures) target the reduction of learning, coordination and even adaptive expectation effects.

However, local media’s preferences for a specific public support instrument might depend on the type of strategy. This leads to the following research question (RQ3): How do local media’s preferences for public un-lock mechanisms differ depending on the type of strategy?

Moreover, drawing on Schreyögg, Sydow, and Koch (Citation2003) as well as Ericson and Lundin (Citation2013), we expect that local media’s preferences for public un-lock mechanisms will differ depending on the degree of a strategic lock-in. First, while local media may benefit from media subsidies and further instruments of public support, they may also experience a loss of journalistic independence (Trappel Citation2015). This suggests that local media will more likely accept public un-lock mechanisms the more they are under pressure, i.e., the higher the degree of a strategic lock-in is. However, the main challenge of strategic lock-ins is that decision-makers are stuck (Schreyögg, Sydow, and Koch Citation2003). Accordingly, we suggest that the higher the degree of a strategic lock-in is, the less will local media be able to identify specific public un-lock mechanisms. This leads to the following hypotheses:

H1a: The relationship between the type of strategy and local media’s range of preferred public un-lock mechanisms is mediated by the degree of lock-in of a strategy in that a higher degree of lock-in leads to a higher range of preferred public un-lock mechanisms.

H1b: The relationship between the type of strategy and local media’s range of preferred public un-lock mechanisms is mediated by the degree of lock-in of a strategy in that a higher degree of lock-in leads to a lower range of preferred public un-lock mechanisms.

summarizes the conceptual model of the study and provides an overview of the research questions and hypotheses.

Methods

Data

To examine the research questions and test the hypotheses, we investigated news organizations, which operate at the local or regional level in the Swiss Canton of St. Gallen. Data were collected based on an online survey. More specifically, with the online survey we measured local media’s perceptions of lock-in mechanisms (i.e., constraints of innovation), their lock-ins (i.e., status of innovation) and their preferences for public un-lock mechanisms (i.e., media subsidies and other public support instruments) regarding the four introduced strategies: multimedia formats (MM) and artificial intelligence applications (AI) as well as revenue diversification (RD) and digital payment models (DP).

In a first step, the population of local media, which operate in the Canton of St. Gallen, was defined based on Swiss audit bureaus of circulation (WEMF) and online traffic (NET-Metrix) as well as based on industry reports. The study considered different media types, i.e., print, radio, TV and online only. Local government gazettes and (hyper-)local citizen journalism (Ford and Ali Citation2018), however, were not analysed. This resulted in 49 local media.

In a second step, the online survey referring to the four strategies was sent to corresponding media managers or editors-in-chief via personalized e-mails. We surveyed actors on higher management levels because they have a relatively broad overview regarding lock-in mechanisms and lock-ins in their news organizations in terms of the investigated content and commercial strategies. Moreover, their preferences are particularly influential in terms of what public un-lock mechanisms shall be implemented on the organizational and policy levels. The online survey was administered via UniPark and took place between November and December 2019 (incl. two reminders).

31 local media responded to the survey. More specifically, 17 local media are print outlets, three are radio stations, also three are TV stations and eight are online only players. Accordingly, print outlets are the most frequent media type in the sample. However, all local media have a news website. Moreover, in terms of the media market, the local media operate on average in 2,97 electoral districts of the Canton of St. Gallen. Furthermore, 20 local media are owned by a parent media company. Finally, in terms of newsroom resources, the local media have on average 7,65 full-time equivalents (FTE). Overall, as four strategies were investigated per local news organization, this resulted in N = 124 observations on the strategy level.

The questionnaire for the online survey consisted of four sections with closed and open-ended questions. The first section investigated the characteristics of local media, while the subsequent sections assessed local media’s perceptions of lock-in mechanisms, their lock-ins and their preferences for public un-lock mechanisms per strategy. We operationalized the constructs based on literature regarding local journalism, public support and strategic path dependence (see literature review and theoretical framework).

Measurement

Strategy

In a first step, the status quo of the strategies was measured (item: “please indicate whether you are currently pursuing the following activity in your local news organization: [type of strategy]”). In terms of MM, respondents were asked whether they publish podcasts (1 = yes; 0 = no) and videos (1 = yes; 0 = no) on their news websites. In terms of AI, respondents were asked whether they use algorithms for the automated identification of issues for news coverage (1 = yes; 0 = no), for the automated production of news content (1 = yes; 0 = no) and for the personalized distribution of news content (1 = yes; 0 = no). In terms of RD, respondents were asked whether they use alternative revenue sources such as events, educational offers, publishing services or e-commerce (1 = yes; 0 = no). Finally, respondents were asked whether they use DP such as full and metered paywalls, freemium models or micropayments (1 = yes; 0 = no).

Lock-In Mechanisms

For each strategy, respondents were asked to select the corresponding perceived constraints (multiple answers; item: “please indicate the most important restrictions and challenges in your local news organization regarding the implementation of [type of strategy]”): lack of financial resources (1 = yes; 0 = no), lack of human resources (1 = yes; 0 = no), lack of know-how (1 = yes; 0 = no), disagreement at the management level (1 = yes; 0 = no), inflexible or hindering organizational structure (1 = yes; 0 = no), interest/acceptance on the user market is not known or not existent (1 = yes; 0 = no), interest/acceptance on the advertising market is not known or not existent (1 = yes; 0 = no), added value of the strategy is not known or not existent (1 = yes; 0 = no), regulative constraints (1 = yes; 0 = no) or other constraints (1 = yes; 0 = no). Moreover, respondents had the option to indicate that they don’t perceive any constraints (1 = yes; 0 = no) and they were invited to specify other constraints via an open-ended question.

For the statistical analysis, dummy variables were constructed. They relate to commitment, learning, coordination and adaptive expectation effects, i.e., constraints regarding financial and human resources (1 = yes; 0 = no), know-how (1 = yes; 0 = no), structure (i.e., management and organization) (1 = yes; 0 = no) and market (i.e., user market, advertising market, added value and regulative constraints) (1 = yes; 0 = no). A further dummy variable refers to no perceived constraints (1 = yes; 0 = no). As all respondents specified other constraints, this variable was merged with the variables structure and market.

Lock-Ins

For each strategy, respondents were asked to choose one of the following options in terms of lock-ins (item: “please indicate your local news organization’s future plans regarding [type of strategy]”). In the case that local media have already implemented a strategy (to some extent), respondents were asked whether they plan to further develop this strategy (1 = yes; 0 = no) or whether they are interested (1 = yes; 0 = no) or not interested (1 = yes; 0 = no) to do so. In the case that local media have not implemented a strategy yet, respondents were asked whether they plan to implement the strategy (1 = yes; 0 = no) or whether they are interested (1 = yes; 0 = no) or not interested (1 = yes; 0 = no) to do so. Due to zero cell counts, for the statistical analysis, we collapsed the six categories into three variables: planned (1 = yes; 0 = no), interested (1 = yes; 0 = no) and not interested (1 = yes; 0 = no). Moreover, in terms of the degree of strategic lock-in, we created an ordinal variable: 3 = not interested; 2 = interested; 1 = planned.

Un-Lock Mechanisms

For each strategy, respondents were asked to select the corresponding preferred public un-lock mechanisms (multiple answers; item: “please indicate the most useful instruments to publicly support your local news organization regarding the implementation of [type of strategy]”): seed funding (1 = yes; 0 = no), financing of education and further education (1 = yes; 0 = no), organization of workshops for knowledge transfer (1 = yes; 0 = no), development of collaborations and partnerships (1 = yes; 0 = no), development of informal networks for industry exchange (1 = yes; 0 = no), other direct subsidies (1 = yes; 0 = no) and other indirect subsidies (1 = yes; 0 = no). Moreover, respondents had the option to indicate that they do not identify any preferred enablers (1 = yes; 0 = no) and they were invited to specify other direct and indirect subsidies via an open-ended question.

For the statistical analysis, dummy variables were constructed. They relate to established instruments, which aim to publicly support local media in overcoming commitment, learning, coordination and adaptive expectation effects: financial and human resources (i.e., seed funding) (1 = yes; 0 = no), know-how (i.e., education and workshops) (1 = yes; 0 = no), collaborations (i.e., partnerships and networks) (1 = yes; 0 = no) as well as other direct and indirect media subsidies (1 = yes; 0 = no). A further dummy variable refers to no identified enablers (1 = yes; 0 = no). Moreover, in terms of the range of preferred public un-lock mechanisms, we recoded the dummy variables into an additive index and created an ordinal variable: 4 = 4; 0 = 0.

Controls

In terms of media type (item: “please indicate the media type of your local news organization”), respondents were asked whether their local news organization is a print outlet (1 = yes; 0 = no), a radio station (1 = yes; 0 = no), a TV station (1 = yes; 0 = no) or an online only player (1 = yes; 0 = no). For the statistical analysis, we constructed a dummy variable: print outlet (1 = yes; 0 = no). Moreover, in terms of media market (multiple answers; item: “please indicate the distribution area of your local news organization according to the electorial districts in the Canton of St. Gallen”), respondents were asked in which of the eight electoral districts of the Canton of St. Gallen they operate. In terms of ownership structure (item: “please indicate whether your local news organization is part of a parent media company”), respondents were asked whether their local news organization is part of a parent media company or not (1 = yes; 0 = no). Finally, in terms of newsroom resources (item: “please indicate how many newsroom resources your local news organization has”), respondents were asked to indicate the number of staff members expressed as full-time equivalents (FTE).

provides an overview of the measurement of the constructs and the variables, which we used for the statistical analysis.

Table 1. Measurement of constructs.

Data Analysis

To examine research questions 1-3, logistic regressions were performed with SPSS. For that purpose, we created dummy variables for AI (1 = yes; 0 = no), RD (1 = yes; 0 = no) as well as DP (1 = yes; 0 = no) and used MM as reference category. After all, MM is most widely implemented ( and ) and facilitates a comparison with (the investigated) emerging strategies.

Table 2. Descriptive statistics (status quo of strategy implementation).

Table 3. Descriptive statistics (lock-in mechanisms, lock-ins and un-lock mechanisms).

Furthermore, to test the hypotheses, we conducted a mediation analysis with the PROCESS macro for SPSS (Hayes Citation2018). Significance was tested using 10,000 bootstrapped samples to estimate 95% bias-corrected confidence intervals. A mediation is significant when the 95% confidence interval does not include zero (Hayes Citation2018).

Findings

Descriptive Statistics

indicates sums and percentages regarding the status quo of the implementation per strategy, while indicates sums and percentages regarding local media’s perceptions of lock-in mechanisms, their lock-ins and their preferences for public un-lock mechanisms per strategy. In terms of the status quo, the findings show that 90,3% of the investigated local media have already implemented MM to some extent. However, fewer local media are already using AI (25,8%) and RD (29%) and even fewer local media are already operating DP (6,5%).

Logistic Regressions

Lock-In Mechanisms

As shows, local media are significantly less likely to perceive a lack of financial and human resources as a constraint regarding DP (odds ratio = 0,011), AI (odds ratio = 0,111) and RD (odds ratio = 0,146) than regarding MM.

Table 4. Logistic regressions (lock-in mechanisms).

A similar pattern holds for know-how. Local media are significantly less likely to perceive a lack of know-how as a constraint regarding DP (odds ratio = 0,091) and RD (odds ratio = 0,143) than regarding MM. However, the findings do not indicate significant differences between AI and MM.

Moreover, in terms of structure, the findings do not indicate significant differences. In fact, disagreements at the management level and inflexible organizational structures have been rarely identified as lock-in mechanisms ().

Furthermore, local media are significantly more likely to perceive market constraints regarding DP and AI than regarding MM. In fact, the odds ratios indicate that local media are even more likely to identify market constraints regarding DP than regarding AI. However, local media are significantly less likely to perceive market constraints regarding RD than regarding MM.

Finally, local media are significantly more likely to not identify any lock-in mechanisms regarding RD than regarding MM. However, the findings do not indicate significant differences between AI and DP as well as MM.

Lock-Ins

As shows, local media are significantly less likely to be already planning to (further) implement RD (odds ratio = 0,101), AI (odds ratio = 0,159) and DP (odds ratio = 0,366) than MM.

Table 5. Logistic regressions (lock-ins).

Moreover, local media are significantly less likely to be interested to (further) implement DP than MM. However, the findings do not indicate significant differences between AI and RD as well as MM.

Finally, local media are significantly more likely to be not interested to (further) implement DP, AI and RD than MM. In fact, the odds ratios indicate that local media are most likely uninterested in the case of DP.

Un-Lock Mechanisms

As shows, local media are significantly less likely to prefer public support in terms of financial and human resources regarding DP (odds ratio = 0,038) than regarding MM. However, the findings do not indicate significant differences between AI and RD as well as MM.

Table 6. Logistic regressions (un-lock mechanisms).

This pattern holds also for know-how related public un-lock mechanisms. After all, local media are significantly less likely to prefer public support in terms of know-how regarding DP (odds ratio = 0,208) than regarding MM. However, the findings do not indicate significant differences between AI and RD as well as MM.

Moreover, local media are significantly less likely to prefer public support in terms of collaborations regarding DP (odds ratio = 0,088), AI (odds ratio = 0,161) and RD (odds ratio = 0,161) than regarding MM.

However, regarding other direct or indirect media subsidies, the findings do not indicate significant differences between the strategies. In fact, such public un-lock mechanisms have been rarely identified ().

Finally, local media are significantly more likely to not identify any public un-lock mechanisms regarding DP, RD and AI than regarding MM. In fact, the odds ratios indicate that local media are least likely to identify public un-lock mechanisms regarding DP.

Mediation Analysis

As shows, AI (B = −0,241, 95% CI = −0,461 to −0,080), RD (B = −0,208, 95% CI = −0,393 to −0,067) and DP (B = −0,296, 95% CI = −0,550 to −0,114) have significant and negative relative indirect effects on local media’s range of preferred public un-lock mechanisms through their degree of lock-in.

Table 7. Mediation analysis.

This indicates that local media are more likely to have a higher degree of lock-in in the case of these strategies than in the case of MM and, therefore, are also more likely to identify a lower range of public un-lock mechanisms in the case of these strategies. In fact, the coefficients indicate that this holds more for DP, less for AI and even less so for RD.

Discussion

Regarding research questions 1-3, the logistic regressions reveal significant differences between the investigated strategies in relation to local media’s perceptions of lock-in mechanisms (i.e., constraints of innovation), their lock-ins (i.e., status of innovation) and their preferences for public un-lock mechanisms (i.e., media subsidies and other public support instruments).

More specifically, in the case of MM, local media perceive that innovation is relatively strongly constrained by a lack of financial and human resources and by a lack of know-how. Accordingly, commitment and learning effects are particularly relevant lock-in mechanisms regarding MM. Nevertheless, local media face the lowest degree of lock-in regarding this content strategy. After all, most of the investigated local media are already publishing MM () and they are also more likely to be already planning to (further) develop podcasts and videos.

At the same time, in the case of MM, local media have a relatively high interest in public un-lock mechanisms, which provide financial and human resources (i.e., seed funding) as well as know-how transfer (i.e., financing of education and further education; organization of workshops for knowledge transfer) and, above all, facilitate collaborations (i.e., development of partnerships and informal networks for industry exchange).

Accordingly, the findings suggest that local media are more willing to collaborate in a field, in which they have more experience. While this approach is comprehensible, local media might also benefit from collaborations regarding other strategies. After all, previous research has shown that local media are increasingly forging partnerships with other local media for instance regarding AI and DP (Kaufmann et al. Citation2019). Thereby, they aim to pool resources, share know-how and use scale effects (Buschow and Wellbrock Citation2019; Jenkins and Graves Citation2019; Villi et al. Citation2020).

Moreover, in the case of AI, local media perceive that innovation is relatively strongly constrained by a lack of know-how and market constraints. Therefore, learning and adaptive expectation effects are particularly relevant lock-in mechanisms regarding AI. In fact, many local media state that, so far, they do not see an added value of AI, which might be related to their lack of know-how. After all, previous research has shown that local media in various countries are already developing AI applications (Kaufmann et al. Citation2019) to increase efficiency and output of news production and to address audiences’ specific needs more effectively (Lindén and Tuulonen Citation2019; Diakopoulos Citation2019).

Accordingly, in the case of AI, local media face a relatively high degree of lock-in. After all, few local media are already using AI for the automated identification of issues for news coverage, for the automated production of news content and for the personalized distribution of news content (). However, many local media are interested to use AI applications in the future. To achieve this, local media have a relatively high interest in public un-lock mechanisms, which provide financial and human resources as well as know-how transfer.

Furthermore, compared to the other investigated strategies, local media are least likely to identify any specific lock-in mechanisms in the case of RD. At the same time, however, they face a relatively high degree of lock-in regarding this strategy. After all, few local media have already diversified their revenue strategies through events, educational offers or publishing services (), though many local media are interested to do so in the future.

As local media are least likely to identify any specific lock-in mechanisms regarding RD, the findings suggest that so far – i.e., as long as their traditional revenue strategies were sufficient – local media have simply not perceived a need to explore new revenue sources. Nevertheless, they have also a relatively high interest in public un-lock mechanisms, which provide financial and human resources as well as know-how transfer.

Finally, in the case of DP, local media perceive that innovation is relatively strongly constrained by market constraints. Accordingly, adaptive expectation effects are a particularly relevant lock-in mechanism regarding DP. Most local media state that they are uncertain whether users will be willing to pay for their news content. In fact, compared to the other investigated strategies, local media face the highest degree of lock-in regarding this commercial strategy. The majority of local media has not implemented a digital payment model yet () and is also not interested to do so in the future. Accordingly, in the case of DP, local media are least likely to identify public un-lock mechanisms.

In view of strategic path dependence theory, the findings show not only that different strategies are constrained by different lock-in mechanisms. They indicate also that different lock-in mechanisms lead to different degrees of strategic lock-in. More specifically, the findings suggest that adaptive expectation effects are a particularly powerful lock-in mechanism and lead to a particularly high degree of strategic lock-in.

This is apparent in the case of DP where innovation is particularly strongly hindered by market constraints and where the investigated local media experience the highest degree of strategic lock-in. As indicated above, most local media state that they are uncertain whether users will be willing to pay for their news content and, accordingly, abstain from implementing DP. A possible explanation why adaptive expectation effects are more powerful than commitment, learning and coordination effects is that they are shaped by actors outside a local news organization and, therefore, are particularly challenging to overcome from within a local news organization.

However, adaptive expectation effects seem to be also particularly challenging to overcome from outside a local news organization, i.e., through public un-lock mechanisms. After all, the findings show not only that different strategies require different types of public un-lock mechanisms. In line with H1b, the findings also confirm that the higher the degree of a strategic lock-in is, the lower is the range of local media’s identified public un-lock mechanisms for the strategy.

More specifically, compared to MM, local media face a higher degree of strategic lock-in regarding RD and an even higher degree regarding AI. The highest degree, however, occurs in the case of DP, which are particularly strongly constrained by adaptive expectation effects. Accordingly, compared to MM, local media identified fewer instruments of public support regarding RD and even fewer regarding AI. Yet, in the case of DP, local media identified the lowest range of public un-lock mechanisms. This, of course, might reinforce local media’s strategic lock-in regarding DP, which, however, are expected to become particularly relevant revenue sources for local media in the future (Hansen et al. Citation2018).

Conclusions

This study investigated how local media’s perceptions of innovation constraints (i.e., lock-in mechanisms), their innovation status (i.e., lock-ins) and their preferences for public support instruments to enable innovation (i.e., public un-lock mechanisms) differ depending on the type of strategy.

Overall, the findings show that the investigated local media in the Swiss Canton of St. Gallen are indeed interested in public un-lock mechanisms in order to facilitate digital transformation. These findings confirm the necessity and calls for more public support regarding local journalism articulated in recent literature (Olsen, Pickard, et al. Citation2020; Pickard Citation2020).

However, more of the same public support is not sufficient. After all, the findings show significant differences between the investigated strategies and suggest – in line with Ali (Citation2017) – a differentiated approach to public support. For instance, while local media have a relatively high interest in public support, which facilitates collaborations, regarding multimedia formats, in the case of artificial intelligence and revenue diversification, they are more interested in public support, which transfers know-how. Accordingly, public support should be targeted and flexible, i.e., it should address specific strategies individually and it should not be limited to financial resources.

In fact, public support faces a further challenge, namely when local media are confronted with a particularly high degree of strategic lock-in – as in the case of digital payment models (DP). While Switzerland is characterized by a relatively high degree of digital news consumption (Newman Citation2020), the majority of the investigated local media in the Swiss Canton of St. Gallen has not implemented DP yet and is also not interested to do so in the future. Accordingly, in the case of DP, local media were least likely to identify instruments of public support. As DP are expected to become particularly relevant revenue sources for local media in the future (e.g., Hansen et al. Citation2018), public support should, therefore, also raise awareness for specific strategies, provide research-based knowledge and discuss solutions (Lindgren, Corbett, and Hodson Citation2020).

The coordination of such diverse and dynamic activities of public support requires an appropriate institutionalization (Murschetz Citation2020) – for instance in the form of media labs (Bisso Nunes and Mills Citation2019). Such media labs might work on behalf of regional governments, collaborate with research institutions and coordinate as well as further develop public support (Kaufmann et al. Citation2019). In fact, such media labs might become interfaces regarding local journalism – connecting “policy, practice, place and publics” (Ali Citation2012, 1113).

The study contributes to journalism research in two ways. First, the study proposes an approach on how to apply and operationalize strategic path dependence theory in order to assess the status of digital transformation strategies in local media and on how to link the status to public support instruments as potential external un-lock mechanisms. Second, the study further contributes by revealing how local media’s perceptions of innovation constraints and their preferences for public innovation enablers differ depending on the type of strategy. After all, while previous research has investigated how different types of media systems publicly support different types of (local) media, differences at the strategy level have found less attention and were not systematically investigated.

However, several limitations of this study need to be addressed. First, as the study focussed on local media, which operate in the Swiss Canton of St. Gallen, the findings are neither representative for the whole Swiss media market (where different Cantons pursue different approaches to public support) nor for other media systems (which vary in terms of public support). Accordingly, future research might explore if local media, which pursue the same strategies but operate in different media markets and regulatory environments, have similar preferences for public support.

Second, the focus on the Swiss Canton of St. Gallen constrained also the size of the investigated local media sample. For instance, a larger sample would facilitate to also investigate interactions between strategy and media type (i.e., print, radio, TV and online only).

Third, the study surveyed media managers and editors-in-chief because they have a relatively broad overview regarding lock-in mechanisms and lock-ins in their news organizations and because their preferences are particularly influential in terms of what public un-lock mechanisms are implemented. Of course, perceptions and preferences of media managers and editors-in-chief do not reflect perceptions and preferences of the entire local news organizations. Accordingly, future research might carve out differences for instance between higher and lower hierarchical levels and between editorial and business departments.

Finally, the study focussed on four specific strategies. Accordingly, future research might investigate constraints and enablers of further strategic approaches, which will become increasingly relevant.

Acknowledgements

We thank the editors and the anonymous reviewers for their valuable remarks on an earlier version of the article.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Ali, Christopher. 2012. “Media at the Margins: Policy and Practice in American, Canadian, and British Community Television.” International Journal of Communication 6: 1119–1138.

- Ali, Christopher. 2016. “The Merits of Merit Goods: Local Journalism and Public Policy in a Time of Austerity.” Journal of Information Policy 6: 105–128.

- Ali, Christopher. 2017. Media Localism: The Policies of Place. Urbana: University of Illinois Press.

- Ali, Christopher, Thomas R. Schmidt, Damian Radcliffe, and Rosalind Donald. 2019. “The Digital Life of Small Market Newspapers: Results from a Multi-Method Study.” Digital Journalism 7 (7): 886–909.

- Bisso Nunes, Ana C., and John Mills. 2019. “Media Labs, Unlocking Change – World News Publishing Focus.” 3. Trends in Newsrooms. WAN-IFRA.

- Buschow, Christopher, and Christian Wellbrock. 2019. “Money for Nothing and Content for Free? Zahlungsbereitschaft für digitaljournalistische Inhalte.” Journalismus Lab. Landesanstalt für Medien NRW.

- Cestino, Joaquin, and Rachel Matthews. 2016. “A Perspective on Path Dependence Processes: The Role of Knowledge Integration in Business Model Persistence Dynamics in the Provincial Press in England.” Journal of Media Business Studies 13 (1): 22–44.

- Diakopoulos, Nicholas. 2019. Automating the News: How Algorithms Are Rewriting the Media. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Ericson, Mona, and Rolf A. Lundin. 2013. “Locking in and Unlocking – Adding to Path Dependence.” In Self-Reinforcing Processes in and among Organizations, edited by Jörg Sydow and Georg Schreyögg, 185–203. London: Palgrave Macmillan UK.

- Ford, Sam, and Christopher Ali. 2018. “The Future of Local News in New York City.” Tow Center for Digital Journalism. Columbia University.

- Gilbert, Clark G. 2006. “Change in the Presence of Residual Fit: Can Competing Frames Coexist?” Organization Science 17 (1): 150–167.

- Goyanes, Manuel. 2015. “The Value of Proximity: Examining the Willingness to Pay for Online Local News.” International Journal of Communication 9: 1505–1522. https://doi.org/1932–8036/20150005.

- Hansen, Elizabeth, Emily Roseman, Matthew Spector, and Joseph Lichterman. 2018. “Business Models for Local News: A Field Scan.” Shorenstein Center on Media, Politics and Public Policy. Harvard University. (blog). 6 September 2018. https://shorensteincenter.org/business-models-field-scan/.

- Harte, David, Rachel Howells, and Andy Williams Abingdon. 2019. “Hyperlocal Journalism: The Decline of Local Newspapers and the Rise of Online Community News.” Digital Journalism 7 (10): 1352–1354.

- Hayes, Andrew F. 2018. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach. 2nd ed. New York: Guilford Press.

- Jacob, Mark. 2019. “What Drives People to Pay for Journalism.” Local News Initiative (blog). 5 February 2019. https://localnewsinitiative.northwestern.edu/posts/2019/02/05/northwestern-subscriber-data/

- Jenkins, Joy, and Lucas Graves. 2019. “Case Studies in Collaborative Local Journalism.” Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism. University of Oxford. https://reutersinstitute.politics.ox.ac.uk/our-research/case-studies-collaborative-local-journalism

- Jenkins, Joy, and Rasmus K. Nielsen. 2018. “The Digital Transition of Local News.” Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism. University of Oxford. https://reutersinstitute.politics.ox.ac.uk/our-research/digital-transition-local-news

- Jenkins, Joy, and Rasmus Kleis Nielsen. 2020. “Proximity, Public Service, and Popularity: A Comparative Study of How Local Journalists View Quality News.” Journalism Studies 21 (2): 236–253.

- Kanton Bern. 2019. “Bericht über die Möglichkeiten der Medienförderung durch den Kanton Bern [Report on Possibilities for Media Support in the Canton of Bern].” Kanton Bern. https://www.gr.be.ch/etc/designs/gr/media.cdwsbinary.DOKUMENTE.acq/88da4547426c4a69b9de2477932d54b2-332/13/PDF/2017.STA.1782-Beilage-D-190464.pdf

- Kaufmann, Vincent, Miriam Meckel, Katarina Stanoevska-Slabeva, Stephanie Grubenmann, Bartosz Wilcze, and Kimberley Köttering. 2019. “Medienförderung im Kanton St.Gallen: Zusammenstellung und Evaluation der Möglichkeiten einer lokalen Medienförderung. [Public Media Support in the Canton of St.Gallen: Synthesis and Evaluation of Possibilites to Publicly Support Local Journalism].” Scientific report for the canton of St.Gallen. University of St.Gallen.

- Konieczna, Magda, John A. Hatcher, and Jennifer E. Moore. 2018. “Citizen-Centered Journalism and Contested Boundaries.” Journalism Practice 12 (1): 4–18.

- Küng, Lucy. 2017. Strategic Management in the Media: Theory to Practice. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications Ltd.

- Künzler, Matthias, Manuel Puppis, Corinne Schweizer, and Samuel Studer. 2013. “Monitoring Report “Medienförderung” [Monitoring Report “Media Subsidies”].” Department of Communication and Media Research. University of Zurich.

- Legg, Heidi. 2019. “A Landscape Study of Local News Models Across America.” Shorenstein Center on Media, Politics and Public Policy (blog). 3 July 2019. https://shorensteincenter.org/landscape-local-news-models/

- Lindén, Carl-Gustav, and Hanna Tuulonen. 2019. “News Automation – The Rewards, Risks and Realities of “Machine Journalism”.” WAN-IFRA. https://www.wan-ifra.org/reports/2019/03/08/news-automation-the-rewards-risks-and-realities-of-machine-journalism

- Lindgren, April, Jon Corbett, and Jaigris Hodson. 2020. “Mapping Change in Canada’s Local News Landscape: An Investigation of Research Impact on Public Policy.” Digital Journalism 8 (6): 758–779.

- Meckel, Miriam. 1999. Redaktionsmanagement: Ansätze aus Theorie und Praxis [Editorial Management: Approaches from Theory and Practice]. Wiesbaden: Westdeutscher Verlag.

- Mintzberg, Henry. 2007. Tracking Strategies: Toward a General Theory - Henry Mintzberg - Google Books. Oxfort: Oxford University Press.

- Murschetz, Paul Clemens. 2020. “State Aid for Independent News Journalism in the Public Interest? A Critical Debate of Government Funding Models and Principles, the Market Failure Paradigm, and Policy Efficacy.” Digital Journalism 8 (6): 720–739.

- Nelson, Jacob L. 2018. “And Deliver Us to Segmentation.” Journalism Practice 12 (2): 204–219.

- Newman, Nic. 2020. “Digital News Report 2020.” Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism. University of Oxford. https://reutersinstitute.politics.ox.ac.uk/sites/default/files/2020-06/DNR_2020_FINAL.pdf

- Nielsen, Rasmus K., and Geert Linnebank. 2011. “Public Support for the Media: A Six-Country Overview.” Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism. University of Oxford. https://reutersinstitute.politics.ox.ac.uk/sites/default/files/2017-11/Public%20support%20for%20Media.pdf

- Olsen, Ragnhild Kristine. 2020. “Understanding the Relationship People in Their Early Adulthood Have to Small-Town News and Paywalls.” Journalism 21 (4): 507–523.

- Olsen, Ragnhild Kristine, Aske Kammer, and Mona Kristin Solvoll. 2020. “Paywalls’ Impact on Local News Websites’ Traffic and Their Civic and Business Implications.” Journalism Studies 21 (2): 197–216.

- Olsen, Ragnhild Kristine, Victor Pickard, and Oscar Westlund. 2020. “Communal News Work: COVID-19 Calls for Collective Funding of Journalism.” Digital Journalism 8 (5): 673–680.

- Olsen, Ragnhild Kristine, and Mona Kristin Solvoll. 2018a. “Bouncing off the Paywall – Understanding Misalignments between Local Newspaper Value Propositions and Audience Responses.” International Journal on Media Management 20 (3): 174–192.

- Olsen, Ragnhild Kristine, and Mona Kristin Solvoll. 2018b. “Reinventing the Business Model for Local Newspapers by Building Walls.” Journal of Media Business Studies 15 (1): 24–41.

- Paulussen, Steve, and Evelien D’heer. 2013. “Using Citizens for Community Journalism.” Journalism Practice 7 (5): 588–603.

- Pickard, Victor. 2020. “Restructuring Democratic Infrastructures: A Policy Approach to the Journalism Crisis.” Digital Journalism 8 (6): 704–719.

- Radcliffe, Damian. 2017. “Local Journalism in the Pacific Northwest: Why It Matters, How It’s Evolving, and Who Pays for It.” SSRN Scholarly Paper ID 3045516. Rochester, NY: Agora Journalism Center. University of Oregon. https://papers.ssrn.com/abstract=3045516

- Radcliffe, Damian, Christopher Ali, and Rosalind Donald. 2017. “Life at Small-Market Newspapers: Results from a Survey of Small Market Newsrooms.” SSRN Scholarly Paper ID 3094661. Rochester, NY: Tow Center for Digital Journalism. Columbia University. https://papers.ssrn.com/abstract=3094661

- Rothmann, Wasko. 2013. “(Qualitäts-)Journalismus Ohne Wert? Über Eine Paradoxie Im Digitalen Strategischen Pfad Der Qualitätszeitungen [(Quality) Journalism without Value? On a Paradox in the Digital Strategic Path of Quality Newspapers].” MedienWirtschaft 10 (3): 10–25.

- Rothmann, Wasko, and Jochen Koch. 2014. “Creativity in Strategic Lock-Ins: The Newspaper Industry and the Digital Revolution.” Technological Forecasting and Social Change 83 (C): 66–83.

- Schmidt, Christine. 2019. “Who Works Best in a Revenue Development Role? Here’s What These Local News Organizations Have Found.” Nieman Lab (blog). 13 August 2019. https://www.niemanlab.org/2019/08/who-works-best-in-a-revenue-development-role-heres-what-these-local-news-organizations-have-found/.

- Schreyögg, Georg, and Jörg Sydow. 2011. “Organizational Path Dependence: A Process View.” Organization Studies 32 (3): 321–335.

- Schreyögg, Georg, Jörg Sydow, and Jochen Koch. 2003. “Organisatorische Pfade –Von der Pfadabhängigkeit zur Pfadkreation? [Organizational Paths – from Path Dependence to Path Creation?].” In Strategische Prozesse und Pfade [Strategic Processes and Paths], edited by Georg Schreyögg, Jörg Sydow, and Jochen Koch, 257–294. Wiesbaden: Gabler Verlag.

- Staw, Barry M. 1981. “The Escalation of Commitment to a Course of Action.” The Academy of Management Review 6 (4): 577–587.

- Stonbely, Sarah, Matthew S. Weber, and Christopher Satullo. 2020. “Innovation in Public Funding for Local Journalism: A Case Study of New Jersey’s 2018 Civic Information Bill.” Digital Journalism 8 (6): 740–757.

- Sydow, Jörg, Georg Schreyögg, and Jochen Koch. 2009. “Organizational Path Dependence: Opening the Black Box.” Academy of Management Review 34 (4): 689–709.

- Trappel, Josef. 2015. “Media Subsidies: Editorial Independence Compromised?” In Media Power and Plurality: From Hyperlocal to High-Level Policy, edited by Steven Barnett and Judith Townend, 187–200. Palgrave Global Media Policy and Business. London: Palgrave Macmillan UK.

- Villi, Mikko, Mikko Grönlund, Carl-Gustav Linden, Katja Lehtisaari, Bozena Mierzejewska, Robert G. Picard, and Axel Roepnack. 2020. “They’re a Little Bit Squeezed in the Middle”: Strategic Challenges for Innovation in US Metropolitan Newspaper Organisations.” Journal of Media Business Studies 17 (1): 33–50.

- Wahl-Jorgensen, Karin. 2019. “The Challenge of Local News Provision.” Journalism 20 (1): 163–166.

- Wenzel, Andrea. 2019. “Public Media and Marginalized Publics: Online and Offline Engagement Strategies and Local Storytelling Networks.” Journalism Practice 13 (8): 906–910.

- Wilczek, Bartosz. 2019. “Complexity, Uncertainty and Change in News Organizations: Towards a Cycle Model of Digital Transformation.” International Journal on Media Management 21 (2): 88–129.