Abstract

How audiences behave behind newspaper paywalls is, in research, almost unknown territory. In editorial offices, however, this has become common knowledge, since traffic data is available around the clock. In this study, we have had the opportunity to study how subscribers with different degrees of subscription experience behave behind the paywall. In the analysis, we use traffic data generated from tracking scripts and stored in Amazon Redshift. The results are unambiguous. Readers with a paid subscription show a higher degree of activity, greater involvement, and more varied usage than do newly added readers with a free subscription, independent of age. Following subscribers with free subscriptions over time shows that their behaviour mainly is negative, with an overall lower degree of activity. Young subscribers with short-term accounts show the lowest degree of activity, independent of the measurement used. Implications of the results are discussed.

Introduction

Since the turn of this century, the Western world has experienced a decrease in newspaper circulation and advertising revenue, mainly due to digitalization and globalization. The dual-financing model has thus been challenged, and media companies have had to make cutbacks. Company managements perceive that the advertising market is more or less lost, and reader revenue has therefore become more important than ever before (Ohlsson and Facht Citation2017). How to attract readers, and then keep them, has thus become a crucial issue, especially online.

However, news consumption is of interest not only to the media business. It is also crucial for society in general, not least because it helps people keep up with current affairs (e.g. Ostertag Citation2010) and creates a sense of belonging (Skogerbø and Winsvold Citation2011).

Subscribed, home-delivered morning papers have long had a strong position in Sweden, the country in focus in this article, which can be defined as a democratic corporatist country (Hallin and Mancini Citation2004). Most of the newspapers were early in publishing online, compared to their global counterparts, and for many years most of the content from newspaper companies was published online free of charge. As in other countries, the strategies gradually changed, and the industry has developed different kinds of paywalls (cf. Arrese Citation2016; Carson Citation2015; Myllylahti Citation2014; Olsen and Solvoll Citation2018b). Since 2017, almost all newspapers in Sweden have had a paywall. Along with Norway, Sweden is at the forefront regarding willingness to pay for online news: a fourth of the population is paying for online news (Digital News Report 2019, Citation2019).

Before paywalls were introduced, traffic between the media sites and social media was regarded as important (Myllylahti Citation2018; Oh, Animesh, and Pinsonneault Citation2016). “Convergence” was a buzzword, and scholars talked about a shift from distribution of analogue content towards the circulation of online content, in order to let the news flow and be spread as much as possible (Jenkins, Ford, and Green Citation2013; cf. Wadbring and Ödmark Citation2016). With the introduction of paywalls, the trend seems to have turned back to distribution of content, but in digital and not analogue form. Instead of trying to increase traffic, it has become important to attract new and loyal readers who paid for the content. The new buzzword in the media industry seems to be “churn”, not convergence or circulation. Having a low churn, i.e. a low dropout of subscribers, has become essential. Everything that can turn a new subscriber into a loyal subscriber is of importance to analyse, and the knowledge is then turned into churn-reducing action (Powell, Wiley, and Gray Citation2019).

In order to reduce the churn, the audience must first and foremost find its way to the newspaper brand, try it, and then find the content interesting enough to stay and become loyal readers. In this study, we will analyse the behaviour of habitual readers, or, to be more specific, subscribers with paid, long-term accounts, along with newly added readers or subscribers with short-term accounts, all behind the paywall. The reading patterns that can be detected behind the paywall will serve as an indicator of the market position for online newspapers in general, especially since this data provides us with more background information than when only general traffic data is used (cf. De Vreese and Neijens Citation2016). We will use the terms “long-term accounts” and “short-term accounts” in the analysis, since we cannot be sure about the relation between accounts and individuals (cf. De Vreese and Neijens Citation2016; Taneja, Citation2016).

As a matter of fact, we know little about how the audience behaves behind the paywall, even if studies point out how increasingly important audience behaviour has become for both media management and journalists (e.g. Wang Citation2018; Zamith Citation2018). A research review shows that several studies have examined the use of analytics/metrics in the newsroom (Belair-Gagnon and Holton Citation2018; Ferrer-Conill and Tandoc Citation2018; Petre Citation2018; Powers Citation2018), audiences’ attitudes towards paywalls and willingness to pay (Chyi Citation2012; Chyi and Lee Citation2013; Chyi, Lee, and Holton Citation2016; Fletcher and Kleis Nielsen Citation2017; Goyanes Citation2014; Gundlach and Hofmann Citation2017; Himma-Kadakas and Kõuts Citation2015; Kammer et al. Citation2015; Olsen and Solvoll Citation2018a), and the content behind the paywalls (Brandstetter and Schmalhofer Citation2014; Kvalheim Citation2020; Myllylahti Citation2017; Saridou, Spyridou, and Veglis Citation2017; Sjøvaag Citation2016).

However, few studies have been conducted on audience behaviour behind the paywalls, probably because access to internal data/metrics is necessary and hard to procure (Taneja, Citation2016). This study is the result of cooperation between the newspaper industry and the academy. It is based on commercial audience metrics, which often are not available for academics. As such, there are advantages as well as drawbacks, which will be discussed in more detail in the methodology section.

The specific aim of the study is to analyse the reading behaviour behind the paywall among readers with different degrees of newspaper subscription experience, i.e. habitual readers/subscribers with long-term accounts and newly added readers/subscribers with short-term accounts. We have five research questions, which are presented in the theoretical section.

Theoretical Framework

One general perspective regarding people’s behaviour and attitudes towards media is the so-called uses-and-gratification approach (for overviews, see Diddi and LaRose Citation2006; Sullivan Citation2013; Sundar and Limperos Citation2013), where at least four factors can be taken into account: structure, situation, motivation, and individual.

In order to evaluate whether a news media outlet offers any value, people must first be able to examine the content. In terms of uses-and-gratification concepts, this is about the media structure. As competition in the media landscape has increased, it is not easy for a subscribed morning paper with a paywall to catch the audience’s attention (Webster Citation2014), and thus it is not easy for potential subscribers to evaluate the content. In this study, however, everyone has the same opportunity to read the paper, due to specific offers (see below, in the methods and material section). In Sweden in general, access to all kinds of platforms is also widespread, especially desktop and smartphones (Swedish Trends 1986–2017, Citation2018), which is another part of the structure issue and thus relevant for people’s opportunity to use a news site.

Second, we have situational factors, where the single most relevant concept might be habits. Habits are self-created and can thus be changed. The meaning of the concept itself implies that an act of doing something has become more or less unconscious and therefore natural. No single decisions have to be made regarding habits. Everyday behaviour often develops into habits and routines (Biel and Dahlstrand Citation2005). On an aggregated level, this means that habits are relatively stable for a population as a whole. When new media forms are introduced, the new forms must find a niche in our already stable time schedules. After our formative years, most people add new habits along with old ones, which do not disappear. For most people, behavioural changes take time (Carey and Elton Citation2010; Diddi and LaRose Citation2006; Ghersetti and Westlund Citation2018; Shehata Citation2016; Voorveld and Viswanathan Citation2015). If a behaviour is not often repeated, habits cannot be established. A high degree of conscious activity is thus a prerequisite for developing new habits regarding regular news consumption (e.g. Biel and Dahlstrand Citation2005; Carey and Elton Citation2010). Our first research question is therefore what kind of differences and similarities in degree of activity can be seen among readers with long-term subscription accounts, compared to readers with short-term subscription accounts? Our second research question concerns the readers with short-term accounts: are there differences in activity, and if so which, between readers who churn and those who turn from a free-of-charge subscription into a paid-for account?

Motivation, as a third factor, refers to the process that causes people to behave as they do. The needs behind the motivation can be biological or learned, and motives have directions as well as strengths. Motives are also goal oriented in order to satisfy specific needs. Needs can be either biogenic or psychogenic, and they differ between individuals (Salomon et al. Citation2010). Here, only psychogenic needs are of interest. Motivation explains, for example, that people with a high political and societal interest consume news to a greater extent than people with low political and societal interest (Prior Citation2007; Strömbäck, Djerf-Pierre, and Shehata Citation2013). People with a high degree of motivation for being informed on societal issues would therefore probably be more motivated to consume hard news, i.e. on topics such as politics, culture, and business (Reinemann et al. Citation2012), which are of importance in a democratic society. High motivation to consume news is closely linked to the establishing of consumption habits. The third research question is therefore on content: what kind of news is read among readers with different types of accounts?

Fourth, examples of important individual factors are age, family situation, family communication, social class, and working situation (cf. Elvestad and Blekesaune Citation2008; Shehata Citation2016; Webster, Phalen, and Lichty Citation2006). Age is the main explanatory factor regarding media use in general and news use in particular. Older people are still rather faithful news readers, but the middle-aged and young are not. Therefore, many scholars have had a strong emphasis on studying young people’s news behaviour (Thurman and Fletcher Citation2019).

Instead of age per se as the explanatory factor, generational belonging may be a more nuanced understanding of the same phenomenon. A generation is constituted on the basis of shared experiences during people’s formative years, where media technology and dominant media forms, among other factors, play a specific role. Generational differences are also bigger for some media forms than for others. It is obvious that the adoption process for new technology is much faster among younger than among older generations, and that legacy media does not play the same role for the young as for the older generation (Antunovic, Parsons, and Cooke Citation2018; Bergström and Jervelycke Belfrage Citation2018; Chiou and Tucker Citation2013; Drok, Hermans, and Kats Citation2018; Ghersetti and Westlund Citation2018; Taneja, Wu, and Edgerly Citation2018; Thurman and Fletcher Citation2019; Wadbring and Bergström Citation2017). Two research questions on age are therefore formulated. First, RQ4: what kind of differences and similarities regarding platform use can be seen related to age? Second, RQ5: what differences and similarities among older and younger readers with short-term accounts can be found over time?

The second part of the uses-and-gratification approach is about gratification obtained from the media use. Because that is an issue beyond this analysis—where we will use traffic data—we will not address gratification in this short review.

Methods and Material

The analysis is based on a case study of the Swedish national quality newspaper Dagens Nyheter (DN), and the method used is registration of media use, analysed through standard SQL to compile metrics.

As with most newspapers, DN is available both in print and online (as a website, an app, and an e-paper), and this study comprises only the digital subscribers using the website and the app. By 1 January 2019, 74% of all digital subscribers used only the site/app, 23% combined the site/app and the e-paper, and the remaining 3% used only the e-paper. In general, digital subscriptions account for just over half of DN’s total circulation. The printed edition, as the other half of the total circulation, is mainly subscribed and home-delivered early in the morning. As a subscriber of the printed edition, you have access to all content online. Some 14% of all subscribers have a digital subscription on weekdays in combination with a subscription for the printed paper during the weekends. None of the subscribers with a printed subscription (solely or partially) are included in the analyses.

Most content (approximately 60%) is locked behind the paywall, and non-subscribers can read a few articles per week of the remaining 40% of the content. All activities on social media are aimed to attracting readers to DN, and texts are therefore not published on social networking services.

This analysis thus covers half of DN’s subscribers. In general, DN’s readers are more highly educated than the average Swede, and more interested in politics. They do, however, have the same age structure as the population as a whole (The SOM Survey 2018, Citation2019).

The specific reason for using DN as a case study is that during autumn 2018, it was possible to conduct a passive registration analysis along with receiving some specific background information for the accounts. Otherwise, when using passive registration data from one media outlet, i.e. site-centric data, it is hard or impossible to gain any background information (De Vreese and Neijens Citation2016). In June 2018, DN had a campaign directed towards youth between 18 and 25 years old, where they could get a digital subscription free of charge until the national election in September 2018. The offer was later extended another full year, until September 2019. In July 2018, a similar offer was given to anyone, independent of age, who was interested in receiving a subscription free of charge throughout 2018. Finally, as a third group, we have the regular subscribers who pay for their subscriptions. All digital users have a subscription ID that can be used to track DN usage for specific groups, and they can also be tracked across devices and browsers. However, analyses are never made on individuals or small groups, in order to respect the privacy of the users.

This means that the three groups have different characteristic profiles in their engagement with reading DN, and thus we can assume that they have different motivation for subscription. Readers behind the long-term subscription accounts, with an ordinary paid subscription, can be assumed to be habitual readers with a high degree of motivation because they pay for their news. The average age of the account holder in this group is 49.

The subscribers under age 25 with short-term accounts have an average age of 22 for the account holder. The other group of subscribers with short-term accounts has an average age of 47. The subscribers behind these latter short-term accounts are thus similar in age to the subscribers behind the long-term accounts, but similar to the short-term accounts with young subscribers regarding willingness to pay, as they do not have an ordinary subscription but accepted the offer to have one free of charge. Both groups who have a free subscription can thus be assumed to have a lower degree of motivation than the subscribers who show willingness to pay (cf. Kammer et al. Citation2015).

It is important to note that the analyses are based on all digital accounts (in other words, the whole population of accounts) during the studied period, and thus not on a selection. Significance testing of data is therefore not needed, since there are no statistical errors (Field Citation2018). However, during the measured period the number of accounts varied somewhat. The average number of active accounts during the measured time period in the analysis was this: short-term accounts with young subscribers, 11,000; short-term accounts with older subscribers, 14,300; and long-term accounts, 128,000. Not all accounts were active every week, however. Adjacent to the respective figure in the analysis, notes will tell the details about the analyses.

Additionally, it is important to emphasize that the analysis is based on subscription accounts, not individuals. It is equally important to know that the analytics at DN are unable to discern how many individuals are using the same accounts. A subscription might be used by an entire family or group of friends, and the person who signed up for the subscription might not be the user of the account. It is also reasonable to believe that it is more common for more than one person to use a paid account than a free account, as it would cost nothing to have several free accounts compared to paid ones. These limitations we have to accept.

For most of the analyses, the measured period is eight weeks: October and November 2018. This means that the Swedish national election was over (it was held September 9) and thus did not “disturb” the analysis, and that the subscribers behind the short-term accounts had time, at least to some extent, to get used to their digital newspaper.

A tracking code is implemented in the source code of the website and app. It collects and stores data in a data warehouse called Amazon Redshift. Clickstreams and events can be fetched and analysed from the data warehouse via a SQL client.

Editors manually mark an article with the specific section where it is to be published. The section identifications, as well as information about tags, titles, and authors, follow the page views made on DN platforms as metadata. All visits to pages, including the DN start page, are in general counted as page views. However, for some analyses, only article page views are considered; these instances are marked next to the analyses.

This study is a result of cooperation between the academy and the media industry, more specifically DN. Without such cooperation, it is hard to obtain data like this (cf. Taneja, Citation2016). However, due diligence must be undertaken, not least regarding validity and reliability (ibid). The cooperation has been close, and it is the researcher who posed the research questions. An analyst at DN helped solve problems and conducted the data analyses. Together the researcher and analyst processed the data. As always, a source of error can be poor data quality, but such a flaw has not been reported during the research period. However, intermittent errors might still occur, although the risk and eventual impact on the results are small.

Another question of importance is validity. Our dependent variables are several, in order to capture diverse behaviour regarding degree of activity and platform used: number of visits, time spent, number of read articles, kind of read articles, different use of platforms. It has been possible to analyse some of the dependent variables in a long-term perspective. Even more important to discuss is our use of independent variables. Passive registration cannot completely correspond to theoretical concepts of behaviour. We cannot be sure that the account holders are the ones who read the paper. Therefore, we use the terms “long-term accounts” and “short-term accounts”, and it is reasonable to believe that the account holders are the main readers but maybe not the only ones.

Our analyses are mainly descriptive-comparative. As it is rare to be able to compare groups of accounts like this, the descriptive analyses have an intrinsic value. Using metrics based on user behaviour also enables us to go beyond self-reported data, like surveys (cf. De Vreese and Neijens Citation2016; Taneja, Citation2016). We mean that it is valuable to describe behaviour which we know little about, and there is a need to use commercial data in academic analyses, since they can be very useful (Taneja, Citation2016).

Findings

The first research question is about the degree of activity among the different groups of subscription accounts. First, it is worth mentioning that not all accounts are active, and this analysis is only about active accounts/users. Among readers with long-term accounts and older readers with short-term accounts, the share of active accounts (those used at least once a week) is 70–80%. Among young readers with short-term accounts, the share of active accounts is 57%. This is thus a first sign of the different degree of activity among the three groups. Even though young readers with short-term accounts do not have to pay for their subscription, and they have had enough motivation to register for a free subscription, only just over half of them use it a few weeks after the subscription begins.

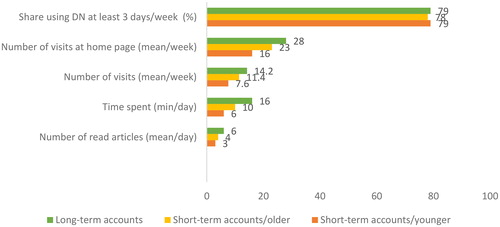

Having said that, it is clear—with one exception—that the degree of activity is highest among readers with long-term accounts and lowest among young readers with short-term accounts in terms of number of visits, time spent, and number of articles read (). The exception from the overall pattern is in the share size of the active accounts that visit DN at least three days a week, which is around 80%, with no significant differences among the different kinds of accounts.

Figure 1. Degree of activity among different kinds of active subscription accounts, 2018 (per cent, mean, minutes, numbers).

Note: The share of active accounts among all accounts/week is 72 per cent among the long-term accounts, 79 per cent among the short-term accounts/older, and 57 per cent among the short-term accounts/younger. The analyses are based on all active accounts, not a selection of accounts. All subscribers with long-term accounts who also have a print subscription are excluded from the analysis. All page views are included independent of time spent, but for number of articles read, only visits longer than five seconds are included. In addition, the articles are counted only once per subscriber, even if they are read several times. The explanation for the higher number of visits on the start page in relation to the number of visits overall is that many readers navigate from the start page to the article, back to the start page, and to the next article, etc.

It is not surprising that readers with long-term accounts show a higher degree of activity than readers with short-term accounts in general: account holders have decided to pay for a subscription, which indicates a higher degree of interest than for those who accepted a free offer. More surprising perhaps is that the share of accounts who visit DN at least three days a week is similar among the three groups analysed. On the other hand, if all accounts were considered instead of only active accounts, the pattern would be different because the share of active accounts differs among the groups (see above). We can conclude that readers with long-term subscription accounts establish stronger habits reading the newspaper behind the paywall than readers with short-term subscription accounts.

The second research question is about conversions. Such an analysis is possible to conduct only for one of the three groups in , namely the short-term accounts/older, because their offer had a fixed end date in another way than the short-term accounts/younger. shows that habits have clear impact on the churn rate, which is much higher among the accounts with a lower degree of activity.

Table 1. Degree of activity on active short-term accounts/older during the free-of-charge period, 2018 (mean).

Number of page views, number of active days during the measured period, and time spent online all seem to have a significant effect on the churn rate. Number of platforms used, however, seems not important at all. Readers with a short-term account who converted into a paid-for subscription after the test period had ended showed a more active behaviour already during the test period. It must however be noted that we do not know if this shows correlation or causality.

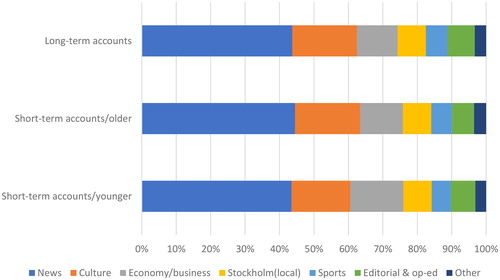

The third research question is about which content attracts readers, i.e. what they read. A first result to mention is that the difference between readers with long-term accounts and both groups of readers with short-term accounts is the same as seen in (not shown in any figure). The readers with long-term accounts read the most, across all content categories, and the young readers with short-term accounts read the least.

However, the proportions of the types of content read among the different kinds of accounts are very similar (). Independent of whether the accounts are long- or short-termed, news articles are read the most, followed by culture and economy/business.

Figure 2. Share of total page views per editorial section among different kinds of active subscription accounts, 2018 (per cent).

Note: Only article page views—not the start page—are included in this analysis. Quizzes, etc. are excluded. All subscribers with long-term accounts who also have a print subscription are excluded from the analysis. The category “other” includes lifestyle, food and drink, insights, obituaries, and travel. The analyses are based on all active account, not a selection of accounts.

The fourth research question is about platforms used among the three groups of readers. The pattern varies depending on the measure used. Readers with long-term accounts use all platforms—dn.se for desktop and mobile as well as the DN app—to a very high extent in an average week. The older readers with short-term accounts prefer the site, mainly on desktop, over the app. In contrast, young readers with short-term accounts mainly use the app (). They also use only one platform to a larger extent than do the other groups. Few young readers with short-term accounts use all three platforms for reading DN.

Table 2. Platforms used among different kinds of active subscription accounts, 2018 (per cent and number).

The pattern regarding the number of page views is similar to previous results: readers with long-term accounts have the most page views independent of platform used, and young readers with short-term accounts have the least. But it is also worth mentioning that even though young readers with short-term accounts use DN on desktop or mobile to a lower extent than the app, they have the most page views per user when using the desktop. The opposite holds for readers with long-term accounts, who primarily use DN on desktop but have more page views per user in the app.

Some platform behaviour does not seem to depend on age or generation, but rather on having a long- or short-term account, i.e. habits. The percentage difference between readers with long-term accounts and short-term accounts (who are similar in age) is in some respects much bigger than the percentage difference between both groups of readers with short-term accounts.

The fifth research question concerns only two of the three analysed groups, the two groups of readers with short-term accounts. Habits are clearly an important factor for reading, and it takes time to establish habits. On an aggregate level, both groups of subscribers with short-term accounts had approximately the same amount of time to establish habits. However, they reflect different age groups and thus reflect the different media environments in which they grew up. Older subscribers with short-term accounts are in this respect more similar to subscribers with long-term accounts, while young subscribers with short-term accounts have grown up in the digital era. The interesting question is therefore whether all newly added readers show similar or different patterns on their way to becoming habitual readers.

First, it is worth mentioning that very few readers visit the site every day. Among the older readers with short-term accounts, 2% visit DN every day, and among the young readers with short-term accounts, the share is less than 1%. (This can be compared with the long-term accounts, where around 10% visit DN every day during a two-month period.)

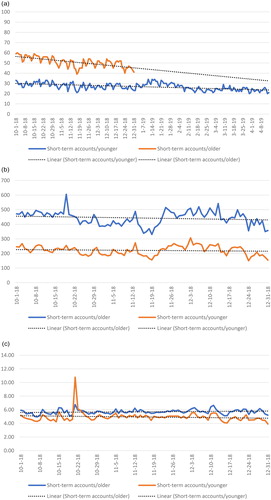

Three analyses were conducted regarding the fifth research question, and due to three different measurements, all over time, they have to be visualized in three figures. For a first measurement regarding both groups with short-term subscription accounts (), the pattern is the same but the level is different between old and young account holders. In both groups, it is not possible to find an increased number of accounts on the site over time, but rather the opposite. The trend line for older readers with short-term accounts shows a decline from 57 to 40% of active accounts per day over two months, and for young readers with short-term accounts a decline from 30 to 25% of active accounts per day for a period of about half a year. The change is thus much smaller for the group of young account holders, but the level is also much lower. Older readers with short-term accounts are at a higher level than younger readers regarding the share of active accounts throughout the measured period.

Figure 3. (a) Share of all accounts that are active per day on the DN website (desktop, tablet, mobile), among young and old subscribers with short-term accounts, 2018–2019 (per cent). (b) Average time spent per day per unique active accounts, among young and old subscribers with short-term accounts, 2018 (seconds). (c) Average number of articles read per day and unique active account, among young and old subscribers with short-term accounts, 2018 (number).

Note: The free subscription stopped by the turn of the year for the old subscribers with short-term accounts, while the young subscribers with short-term accounts had an offer for a whole year starting in summer 2018. The results are based on all active accounts, not a selection of accounts. Sum of time spent for all web pages (inclusive of the start page) are included in the analysis (desktop, tablet, mobile). Time measurement is not available in the app. The results are based on all active accounts, not a selection of accounts. All page views (except the start page) are included in this analysis. The results are based on all active accounts, not a selection of accounts.

Further measurements, to study the change over time, are time spent and the number of articles read. Regarding time spent (), the findings are the same as above concerning differences between the groups: older readers with short-term accounts spend more time reading DN than do younger ones. Over the study period, the groups neither increase nor decrease their time spent.

Regarding the number of articles read (), for which the start page is not counted, the findings are both similar and different from the patterns in : there is almost no change over time for any of the groups, and the difference between the groups of older and younger readers is small. The similarity between is that older readers with short-term accounts read more than young readers with short-term accounts.

Conclusion and Discussion

The specific aim of the study has been to analyse the reading behaviour behind the paywall among readers with different degrees of newspaper subscription experience, and the results are clear. Access to an online newspaper is not enough to reach a high degree of readership, even if the reader is interested enough to accept a free offer and also to read the paper on a regular basis.

The degree of activity differs widely among the three groups analysed. Habitual readers, i.e. readers with a paid, long-term DN account, have much higher activity than newly added subscribers—and among readers with short-term accounts, older readers have a higher degree of activity than younger readers. General news interest and generational belonging are probably the most important explanations (cf. Himma-Kadakas and Kõuts Citation2015; Kammer et al. Citation2015; Thurman and Fletcher Citation2019). In comparison to readers with a paid subscription, newly added readers have not been willing to pay for their news. On the other hand, their interest was large enough to accept a free subscription. Among those who did not churn after the period with a free-of-charge subscription was over, but turned into a paid-for subscription, the degree of activity was much higher than among the churned subscribers.

But even if both newly added groups of subscribers have the same prerequisites, the behaviour on their accounts is dissimilar. The older group with short-term accounts is close in age to readers with long-term accounts; they both grew up in an analogue media environment. A lot of them probably have past habits in reading a newspaper, or at least they grew up in a home where a (paper) subscription was available. Clear family effects regarding readership and news habits have been seen in previous research (Shehata Citation2016). However, it must be emphasized that this analysis covers only one specific media brand. Research shows that the generational gap is smaller regarding online news use than general news use, if several news sites are taken into account (Taneja, Wu, and Edgerly Citation2018).

Young readers with a short-term account show a low degree of activity. Almost half of them do not use their subscription at all, and for the rest, the level of activity is low. For young people, the use of social media is at least as important as legacy media for news consumption. They have habits, but their habits are different from those of older news consumers. Through social media they assume they will be informed, and both incidental and directed consumption is regarded as important (cf. Antunovic, Parsons, and Cooke Citation2018; Bergström and Jervelycke Belfrage Citation2018). A newspaper subscription is only one extra source of information.

The content that attracts and engages the different groups of readers is the same: hard news is most read among all groups. This means that generational belonging does not seem to be important in the same way as degree of activity regarding attraction and engagement. However, in relation to the number of people aged 18 to 25 living in Sweden, the share of young subscribers on DN is small. That might serve as an indicator for similarities within the group. First, these young people found the offer of a free subscription; second, they accepted it; and third, those included in the analysis have active accounts. Probably they are all interested in societal issues. Furthermore, the same can be said about older readers with short-term accounts—and also habitual readers with long-term, paid accounts. In a media environment with few choices most people subscribe to a morning paper, but in a digital media environment like that of today, only the most dedicated are left (cf. Prior Citation2007).

In the analogue era, the reading platform was not an issue, but today this is highly relevant. Previous research has shown that the materiality of devices and platforms has an impact on news consumption in several ways. When using a non-media-centric approach, news consumption can be placed in an everyday life context, where different devices clearly are used for different purposes (Groot Kormelink and Costera Meijer Citation2019). The uses-and-gratification approach is about how people actively seek the media (cf. Sullivan Citation2013), and in this study the subscribers have actively chosen DN—but they use it in different ways, beginning with which media format is chosen. Clear differences in reading patterns are found not only between print and digital media but also among different digital devices. Scrolling, for example, can be the default mode for Facebook, and every stop or pause can feel like an interruption (Groot Kormelink and Costera Meijer Citation2019). For some users at least, online news might have the same default mode. It is clear that reading news on a desktop computer or laptop at home or the office, compared to using a smartphone, is a different experience, both regarding place (home or on the go) and the size of the screen. A generational difference rather than a difference regarding one’s historic reading of DN is obvious in the results. Using DN in the app is clearly most common for young readers with short-term accounts, while older readers with short-term accounts use the app to a lower extent. Habitual readers with a paid subscription have a more varied use of platforms.

The premises for both groups of newly added subscribers are that they have accepted a free subscription and use it, but they are different in age structure. Except for the difference between the two groups regarding level of use, the development over time is very similar. Independent of the measurement used, no increase in reading over time can be found. This must mean that their habits were established very early, but on a lower level than for the habitual readers with long-term accounts (cf. Diddi and LaRose Citation2006). One explanation for the stability might be that the less interested readers left at an early stage, and the remaining readers established an early reading pattern and kept that throughout their free subscription period.

When the older readers with a short-term account had to start paying after the turn of the year (2018/2019), a large share disappeared quickly: more than half of the subscribers churned. As we also see that the degree of activity among the remaining subscribers decreases over time, it becomes clear how hard it is to keep newly added subscribers. Similar results can be seen at newspapers like the Wall Street Journal, where a project designed for reducing churn found that new habits are formed rather quickly—or not at all (Powell, Wiley, and Gray Citation2019). Experiments to create habits are used at DN as well as other news outlets all the time to keep down the churn and to retain loyal readers. That is of importance not only for the media business, but also for society.

Limitations and Concerns

One limitation is that this article is about accounts and not individuals, and about only online use, without considering printed media as well. However, the kind of data used in this study is exactly what is used in the editorial offices. A lot of short- as well as long-term decisions are based on such data. Metrics have impact. At the same time, the printed newspaper is still the most important platform for reading (Thurman Citation2018; Von Krogh and Andersson Citation2016), and there are several risks with using the metrics in a too extensive and exclusive way. People’s behaviour online can certainly be tracked, and it is valuable, so long as it is not regarded as valid for readers in general. First, only a limited portion of readers can be studied through metrics, since all readers in print are absent in the analyses, and they might have totally different behaviour and interests as those of online readers. Second, the true meaning of clicks and reading is multifaceted. This is especially true for non-clicks (Groot Kormelink and Costera Meijer Citation2018). A methodological pluralism is still necessary for research (cf. Zamith Citation2018) and in newsroom work as well.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Dagens Nyheter for generously sharing requested data.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Arrese, Ángel. 2016. “From Gratis to Paywalls.” Journalism Studies 17 (8): 1051–1067.

- Antunovic, Dunja, Patrick Parsons, and Tanner R. Cooke. 2018. “Checking’ and Googling: Stages of News Consumption among Young Adults.” Journalism 19 (5): 632–648.

- Belair-Gagnon, Valerie, and Avery E. Holton. 2018. “Boundary Work, Interloper Media, and Analytics in Newsrooms.” Digital Journalism 6 (4): 492–508.

- Bergström, Annika, and Maria Jervelycke Belfrage. 2018. “News in Social Media. Incidental Consumption and the Role of Opinion Leaders.” Digital Journalism 6 (5): 583–598.

- Biel, Anders, and Ulf Dahlstrand. 2005. “Values and Habits: A Dual-Process Model.” In Environment, Information and Consumer Behaviour, edited by S. Krarup and C.S. Russel, Northampton, MA: Edward Elgar Cheltenham.

- Brandstetter, Barbara, and Jessica Schmalhofer. 2014. “Paid Content.” Journalism Practice 8 (5): 499–507.

- Carey, John, and Martin C. J. Elton. 2010. When Media Are New. Understanding the Dynamics of New Media Adoption and Use. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press.

- Carson, Andrea. 2015. “Behind the Newspaper Paywall – Lessons in Charging for Online Content: A Comparative Analysis of Why Australian Newspapers Are Stuck in the Purgatorial Space between Digital and Print.” Media, Culture & Society 37 (7): 1022–1041.

- Chiou, Lesley, and Catherine Tucker. 2013. “Paywalls and the Demand for News.” Information Economics and Policy 25 (2): 61–69.

- Chyi, Hsiang Iris. 2012. “Paying for What? How Much? And Why (Not)? Predictors of Paying Intent for Multiplatform Newspapers.” International Journal on Media Management 14 (3): 227–250.

- Chyi, Hsiang Iris, and Angela M. Lee. 2013. “Online News Consumption. A Structural Model Linking Preference, Use and Paying Intent.” Digital Journalism 1 (2): 194–211.

- Chyi, Hsiang Iris, Angela M. Lee, and Avery E. Holton. 2016. “Examining the Third-Person Perception on News Consumers’ Intention to Pay.” Electronic News 10 (1): 24–44.

- De Vreese, Claes H., and Peter Neijens. 2016. “Measuring Media Exposure in a Changing Communications Environment.” Communication Methods and Measures 10 (2-3): 69–80.

- Diddi, Arvind, and Robert LaRose. 2006. “Getting Hooked on News: Uses and Gratifications and the Formation of News Habits among College Students in an Internet Environment.” Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media 50 (2): 193–210.

- Digital News Report 2019. 2019. Digital News Report 2019. Oxford: Reuters Institute.

- Drok, Nico, Liesbeth Hermans, and Karijn Kats. 2018. “Decoding Youth DNA: The Relationship between Social Engagement and News Interest, News Media Use and News Preferences of Dutch Millennials.” Journalism 19 (5): 699–717.

- Elvestad, Eiri, and Arild Blekesaune. 2008. “Newspaper Readers in Europe: A Multilevel Study on Individual and National Differences.” European Journal of Communication 23 (4): 425–447.

- Ferrer-Conill, Raul, and Edson C. Tandoc. Jr, 2018. “The Audience-Oriented Editor.” Digital Journalism 6 (4): 436–453.

- Field, Andy. 2018. Discovering Statistics Using IBM SPSS Statistics. Los Angeles: Sage publications.

- Fletcher, Richard, and Rasmus Kleis Nielsen. 2017. “Paying for Online News.” Digital Journalism 5 (9): 1173–1191.

- Ghersetti, Marina, and Oscar Westlund. 2018. “Habits and Generational Media Use.” Journalism Studies 19 (7): 1039–1058.

- Goyanes, Manuel. 2014. “An Empirical Study of Factors That Influence the Willingness to Pay for Online News.” Journalism Practice 8 (6): 742–757.

- Groot Kormelink, Tim, and Irene Costera Meijer. 2018. “What Clicks Actually Mean: Exploring Digital News User Practices.” Journalism 19 (5): 668–683.

- Gundlach, Hardy, and Julian Hofmann. 2017. “Preferences and Willingness to Pay for Tablet News Apps.” Journal of Media Business Studies 14 (4): 257–281.

- Hallin, Daniel C., and Paolo Mancini. 2004. “Comparing Media Systems.” Three Models of Media and Politics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Himma-Kadakas, Marju, and Ragne Kõuts. 2015. “Who is Willing to Pay for Online Journalistic Content?” Media and Communication 3 (4): 106–115.

- Jenkins, Henry, Sam Ford, and Joshua Green. 2013. Spreadable Media. Creating Value and Meaning in a Networked Culture. New York: New York University Press.

- Kammer, Aske, Morten Boeck, Jakob Vikaer Hansen, Hadberg Hauschildt, and Lars Juul. 2015. “The Free-to-Fee-Transition: Audiences’ Attitudes toward Paying for Online News.” Journal of Media Business Studies 12 (2): 107–120.

- Kormelink, Tim Grot, and Irene Costera Meijer. 2019. “Material and Sensory Dimensions of Everyday News Use. Media.” Media, Culture & Society 41 (5): 637–653.

- Kvalheim, Nina. 2020. “News behind the Wall. An Analysis of the Relationship between the Implementation of a Paywall and News Value.” Nordicom Review 34 (s1): 25–42.

- Myllylahti, Merja. 2014. “Newspaper Paywalls – the Hype and the Reality.” Digital Journalism 2 (2): 179–194.

- Myllylahti, Merja. 2017. “What Content is Worth Looking behind a Paywall?” Digital Journalism 5 (4): 460–471.

- Myllylahti, Merja. 2018. “An Attention Economy Trap? An Empirical Investigation into Four News Companies’ Facebook Traffic and Social Media Revenue.” Journal of Media Business Studies 15 (4): 237–253.

- Oh, Hyelim, Animesh Animesh, and Alain Pinsonneault. 2016. “Free versus for-a-Fee: The Impact of a Paywall on the Pattern and Effectiveness of Word-of-Mouth via Social Media.” MIS Quarterly 40 (1): 31–56.

- Ohlsson, Jonas, and Ulrika Facht. 2017. Ad Wars. Digital Challenges for Ad-Financed News Media in the Nordic Countries. Gothenburg: Nordicom.

- Olsen, Ragnhild Kristine, and Mona Kristin Solvoll. 2018a. “Bouncing off the Paywall – Understanding Misalignments between Local Newspaper Value Propositions and Audience Responses.” International Journal on Media Management 20 (3): 174–192.

- Olsen, Ragnhild Kristine, and Mona Kristin Solvoll. 2018b. “Reinventing the Business Model for Local Newspapers by Building Walls.” Journal of Media Business Studies 15 (1): 24–41.

- Ostertag, Stephen. 2010. “Establishing News Confidence: A Qualitative Study of How People Use the News Media to Know the News-World.” Media, Culture and Society 32 (4): 597–614.

- Petre, Caitlin. 2018. “Engineering Consent. How the Design and Marketing of Newsroom Analytics Tolls Rationalize Journalists’ Labor.” Digital Journalism 6 (4): 509–527.

- Prior, Markus. 2007. Post-Broadcast Democracy. How Media Choice Increases Inequality in Political Involvement and Polarizes Elections. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Powell, Anne, John Wiley, and Peter Gray. 2019. Habit formation: How the Wall Street Journal turned user-level data into strategy to keep subscribers coming back. NiemanLab, June 27, 2019.

- Powers, Elia. 2018. “Selecting Metrics, Reflecting Norms. How Journalists in Local Newsrooms Define, Measure, and Discuss Impact.” Digital Journalism 6 (4): 454–471.

- Reinemann, Carsten, Jame Stanyer, Sebastian Scherr, and Guido Legnante. 2012. “Hard and Soft News: A Review of Concepts, Operationalizations and Key Concepts.” Journalism: Theory, Practice & Criticism 13 (2): 221–239.

- Salomon, Michael R., Gary Bamossy, Soren Askegaard, and Margaret K. Hogg. 2010. “Consumer Behaviour.” A European Perspective. Harlow: Prentice Hall.

- Saridou, Theodora, Lia-Paschalia Spyridou, and Andreas Veglis. 2017. “Churnalism on the Rise?” Digital Journalism 5 (8): 1006–1024.

- Shehata, Adam. 2016. “News Habits among Adolescents: The Influence of Family Communication on Adolescents’ News Media Use – Evidence from a Three-Wave Panel Study.” Mass Communication and Society 19 (6): 758–781.

- Sjøvaag, Helle. 2016. “Introducing the Paywall. A Case Study of Content Changes in Three Online Newspapers.” Journalism Practice 10 (3): 304–322.

- Skogerbø, Eli, and Marte Winsvold. 2011. “Audience on the Move? Use and Assessment of Local Print and Online Newspapers.” European Journal of Communication 26 (3): 214–229.

- Strömbäck, Jesper, Monika Djerf-Pierre, and Adam Shehata. 2013. “The Dynamics of Political Interest and News Media Consumption: A Longitudinal Perspective.” International Journal of Public Opinion Research 25 (4): 414–435.

- Sullivan, John L. 2013. Media Audiences. Effects, Users, Institutions, and Power. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Sundar, S. Shyam, and Anthony M. Limperos. 2013. “Uses and Grats 2.0: New Gratifications for New Media.” Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media 57 (4): 504–525.

- Swedish Trends 1986–2017. 2018. Swedish Trends 1986–2017. Gothenburg: The SOM Institute.

- Taneja, Harsch. 2016. “Using Commercial Audience Measurement Data in Academic Research.” Communication Methods and Measures 10 (2-3): 176–178.

- Taneja, Harsh, Angela Ziao Wu, and Stephanie Edgerly. 2018. “Rethinking the Generational Gap in Online News Use: An Infrastructural Perspective.” New Media & Society 20 (5): 1792–1812.

- The SOM Survey 2018. 2019. The SOM Survey 2018. Gothenburg: The SOM Institute: www.som.gu.se.

- Thurman, Neil. 2018. “Newspaper Consumption in the Mobile Age.” Journalism Studies 19 (10): 1409–1429.

- Thurman, Neil, and Richard Fletcher. 2019. “Has Digital Distribution Rejuvenated Readership? Revisiting the Age Demographics of Newspaper Consumption.” Journalism Studies 20 (4): 542–562.

- Von Krogh, Torbjörn, and Ulrika Andersson. 2016. “Reading Patterns in Print and Online Newspapers. The Case of the Swedish Local Morning Paper VLT and Online News Site Vlt.” Digital Journalism 4 (8): 1058–1072.

- Voorveld, Hilde A. M., and Vijay Viswanathan. 2015. “An Observational Study on How Situational Factors Influence Media Multitasking with TV: The Role of Genres, Dayparts, and Social Viewing.” Media Psychology 18 (4): 499–526.

- Wadbring, Ingela, and Annika Bergström. 2017. “A Print Crisis or a Local Crisis? Local News Use over Three Decades. In.” Journalism Studies 18 (2): 175–190.

- Wadbring, Ingela, and Sara Ödmark. 2016. “Going Viral: News Sharing and Shared News in Social Media. In.” Observatorio (OBS*) 10 (4): 132–149.

- Wang, Qun. 2018. “Dimensional Field Theory. The Adoption of Audience Metrics in the Journalistic Field and Cross-Field Influences.” Digital Journalism 6 (4): 472–491.

- Webster, James G. 2014. The Marketplace of Attention. How Audiences Take Shape in a Digital Age. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Webster, James G., Patricia F. Phalen, and Lawrence W. Lichty. 2006. “Ratings Analysis.” The Theory and Practice of Audience Research. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

- Zamith, Rodrigo. 2018. “Quantified Audiences in News Production. A Synthesis and Research Agenda.” Digital Journalism 6 (4): 418–435.