Abstract

People increasingly turn to social media to get their daily news updates. Still, we are only beginning to understand how this development affects people’s perceptions of consumed news stories. The article reports on an experiment designed to investigate the effect the distribution of a news story in social media (Facebook) has on news message credibility. A control group was exposed to a news story on an original news website, and treatment groups were exposed to the same news story shared on Facebook. Results demonstrate that distribution via Facebook affects the credibility of the news story. The effect is strongest when politicians are intermediary-senders, and to some extent depend on the party affiliation of intermediary-sender and the social media audience. In the context of fake news, the results are reassuring: people are less trustful of news they consume through social media. However, the results also suggest that social media news sharing can contribute to the long-term decrease in trust in news.

Introduction

The internet and the emergence of social mediaFootnote1 have altered the political communication systems of advanced democracies in fundamental ways (e.g. Chadwick Citation2013; Blumler Citation2016). News is now not only available on increasingly numerous platforms 24/7 with continuous deadlines, but news stories are also diffused and consumed in digital networks through so-called intermediaries, such as social media platforms like Facebook. In other words, the way people consume news is changing. More and more people, the young in particular, turn to social media, typically Facebook, to get their daily news (Newman et al. Citation2018; Elvestad and Phillips Citation2018; Nielsen and Schrøder Citation2014). Although these developments have potentially fundamental effects on the news audience and the role of the news media in democratic societies, we are only beginning to understand how such intermediaries affect people’s perceptions of news and the credibility of news stories (see Anspach Citation2017; Sterrett et al. Citation2019; Turcotte et al. Citation2015).

From a democratic perspective, it is essential that citizens find news about politics and current affairs credible and trustworthy (e.g. Coleman Citation2012). The more a news source is trusted, the more effective it will be in informing citizens about the relevant information needed to make political choices (Hovland and Weiss Citation1951; Zaller Citation1992; Dahl Citation1998). Trust in news, or news credibility, encompass a variety of factors ranging from trust or credibility in sources, journalists, news outlets, to news organizations (e.g. Kohring and Matthes Citation2007; Fisher Citation2016). News distribution on social media introduce new factors that potentially influence people’s credibility evaluations of news stories (e.g. Anspach Citation2017; Oeldorf-Hirsch and DeVoss, Citation2020; Sterrett et al. Citation2019; Tandoc Citation2019; Turcotte et al. Citation2015).

In this article, we contribute to the emerging literature on news credibility and social media through an experiment designed to investigate to what extent and in what sense sharing of news on social media affects the credibility of the news story. More precisely we study if people find news stories distributed through Facebook less credible than when presented on the original news site. The experiment was embedded in round II of the 2017 Norwegian Election Campaign Panel Survey (NECS), where a control group was exposed to a news story on the website of the original source, while treatment groups were exposed to the same news story distributed on Facebook, with the original news platform still visible.

We develop, based on existing studies, an analytical framework of factors that might influence credibility evaluations when news is distributed in social media. These factors, we argue, act as cues and activate heuristics that influence the evaluation of the news story (e.g. Metzger, Flanagin, and Medders Citation2010). More precisely, we identify and develop hypothesis related to the intermediary platform (e.g. Facebook) the intermediary sender (the individual, organization or page sharing the news story), and the original news source (e.g. a public broadcaster or commercial outlet).

The results show that people’s credibility perceptions of a news story is influenced by distribution via Facebook. There is a clear effect of intermediary distribution on credibility evaluations of the news story. The negative effect of Facebook distribution is stronger when the news story is shared by a politician than when shared by a nonpartizan individual. To some extent, the effects depend on political support for the party the politician represents, but such intermediary-sender effects are part of a complex pattern of news credibility perceptions and political ideology. The results are simultaneously reassuring and unsettling from a democratic perspective. As reports of fake news are increasing (e.g. Lazer et al. Citation2018), it is surely healthy that people are more sceptical of the news they consume through intermediaries like Facebook. However, if scepticism is the new normal, social media news sharing can contribute to long-term decrease in news credibility.

Trust in News

From a democratic perspective, trust in news is essential for the ideal of the informed citizen (e.g. Dahl Citation1998). According to Coleman (Citation2012, 36), citizenship only works on the basis of common knowledge. Hence, not only do we need to be informed ourselves, but we also need to trust that others are informed: ‘Unless we can trust the news media to deliver common knowledge, the idea of the public – a collective entity possessing shared concerns – starts to fall apart’ (Coleman Citation2012, 36). In order to trust that democracy function properly, it is essential to believe that the electorate is well and fairly informed (Tsfati and Cohen Citation2005, 32). Moreover, the more people trust the news, the more effective news will be in providing citizens with relevant information needed to make political choices, as mistrust moderates the influence of media on its audience (e.g. Miller and Krosnick Citation2000). From this perspective, the much-talked-about diminishing trust in news media (e.g. Jones Citation2004; Gronke and Cook Citation2007; Ladd Citation2012; see Newton Citation2017 for a review) is highly worrying. Although the evidence is not crystal clear, studies find that in general, people’s trust in news media is declining (Newman et al. Citation2018; PEW Citation2016).

Trust in news media, however, differs between individuals (e.g. Hanitzsch et al. Citation2018). Still, studies find surprisingly different patterns in regards to what explains trust in the media. Some studies find that education is a positive predictor of media trust (Bennett et al. Citation1999), while others find the opposite (Tsfati and Ariely Citation2014). Some studies find women trust the media more than men (Jones Citation2004; Tsfati and Ariely Citation2014), and others that men trust the media more (Gronke and Cook Citation2007). Conservative political ideology is a negative predictor of trust, at least in the US (Jones Citation2004), and those who consume mainstream media also trust the media more than others (e.g. Tsfati and Ariely Citation2014). In turn, trust in news also drives news consumption (Tsfati and Ariely Citation2014; Fletcher and Park Citation2017). Those with low levels of trust tend to prefer non-mainstream news sources, such as blogs and social media (Fletcher and Park Citation2017). It is also well established that people’s trust varies between different news outlets. Some outlets, such as public broadcasters and traditional broadsheet papers, receive much trust, while tabloids and commercial TV channels in general receive less (Newman et al. Citation2018).

Trust in the media and news is closely related to political bias (Eveland and Shah Citation2003; Lee Citation2010). People tend to believe that media are hostile to their own viewpoints and favour opposing opinions (e.g. Dalton, Beck, and Huckfeldt Citation1998; Vallone, Ross, and Lepper Citation1985). Consequently, a decreasing trust in the news media is partly related to the development of partisan news media in some countries, where more people have come to expect news to be politically biased. Of course, this development is strongest in the US. In Western Europe the development is arguably less dramatic (Newman et al. Citation2018; Newton Citation2017).

News Credibility and Social Media

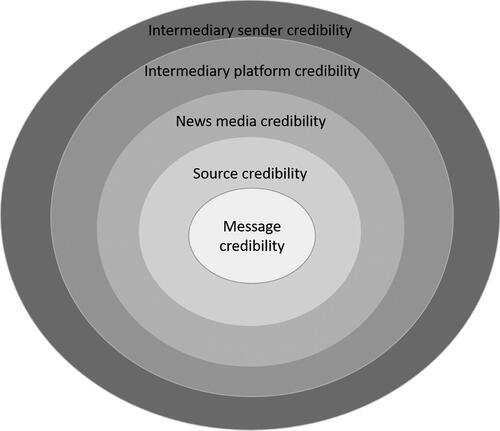

Trust in news is related to a long history of credibility research, and trust and credibility is used nearly interchangeably in the literature (Kohring and Matthes Citation2007; Kiousis Citation2003).Footnote2 A wide range of factors related to the news story itself and the news outlet are thought to influence the credibility of the news story. The introduction of the Internet, and digital network intermediaries, complicated matters further and introduced more factors that need to be considered (see Flanagin and Metzger Citation2017; for an overview). Different analytical approaches has been used to conceptualize this situation. Some, for example, talk of multiple layers of sources (Kang et al. Citation2011, Tandoc Citation2019). We base our approach on previous work that has, in broad terms, distinguished trust in news media into three categories (e.g. Metzger et al. Citation2003; Fisher Citation2016): message credibility—trust in the information presented; source credibility—trust in the provider of the information; and media credibility—trust in the medium conveying the message. We put forward that social media introduce a more complex situation and suggest a more complex framework with five layers, distinguishing the “intermediary platform credibility” (e.g. Facebook) and “intermediary sender credibility” as well. Let us explain in more detail.

When evaluating information, people use heuristics and cues. Granted, sometimes people are highly attentive and carefully process information, but people are often less attentive and therefore rely on mental shortcuts (see Evans Citation2008, for a review of such dual processing models). Of course, heuristics are also used to evaluate news in an online setting (e.g. Metzger, Flanagin, and Medders Citation2010; Metzger and Flanagin Citation2015; Kang et al. Citation2011). Hence, news story credibility is related to and to some extent dependent upon source and media credibility: the sources in the news story, as well as the outlet activate different heuristics that influence evaluations of the message. News story credibility is also related to trust in individual journalists (Kohring and Matthes Citation2007), the journalistic method or journalism as a whole (Blöbaum Citation2014).

Intermediaries, social media such as Facebook, complicates matters further. More specifically, media credibility, the channel conveying the message, is no longer restricted to the original news platform. Rather, when a news story is distributed through intermediaries (at least) two more factors related to media credibility can be distinguished. In addition to the original news platform credibility (e.g. CNN or Fox news), the intermediary platform (e.g. Facebook) as well as the intermediary sender (the individual, group or page) actively sharing the news story are factors potentially influencing media credibility. Whether or not to treat intermediary platform credibility and intermediary sender credibility as an aspect of media credibility or as new independent factors distinguishable from the traditional concept of media credibility is, as we see it, debateable. The essential aspect is that if we zoom in on the news story, the following factors will potentially act as heuristic cues for the audience, and should be included in an explanatory framework related to news story credibility evaluations. This more complex five layered credibility framework is presented in . Visualized in this way it is apparent how the intermediary platform and intermediary sender add to the layers surrounding the message, and potentially act as heuristics influencing peoples’ perceptions of news credibility.

Hypotheses

We build on the analytical framework presented above, and develop hypothesis related to the intermediary platform, and the intermediary sender, and a research question related to the media credibility of the original news source. To our knowledge, there are no existing studies comparing perceptions of news stories in the context of intermediaries with perceptions in the original context. However, numerous studies have investigated trust in traditional vs. online news sources. The internet was initially considered less credible as a source than traditional news sources (e.g. Flanagin and Metzger Citation2000; Johnson and Kaye Citation2010; see Flanagin and Metzger Citation2017; for an overview). However, as increasing numbers of citizens rely on online sources for their daily news, the differences between online and traditional sources have more or less disappeared. Still, digital media, and the hyperlink structure of the Internet, have increased uncertainty about who is responsible for information and whether it can be believed (e.g. Eysenbach and Kohler Citation2002; Rieh and Danielson Citation2002). Indeed, studies show that people in general have less trust in social media, intermediary platforms, such as Facebook, than they have in news outlets (e.g. Newman et al. Citation2018). Reports of and warnings about fake news in social media are plentiful, and people are encouraged to be critical of information they encounter and news they are exposed to on social media platforms (e.g. Lazer et al. Citation2018; Allcott and Gentzkow Citation2017). Hence, distribution of news on social media is likely to influence perceptions of the news story regardless of initial trust in the original source. Hence, in regards to the intermediary platform, all this leads us to formulate following hypothesis, H1: People will find a news story less credible when consuming it on Facebook than when consuming it on the original news outlet platform.

Earlier studies have found that the intermediary sender is important for news story credibility. People tend to trust news stories shared by a trusted news outlet (Tandoc Citation2019), their friends (e.g. Bene Citation2017a; Turcotte et al. Citation2015) and celebrities they already trust (Sterrett et al. Citation2019). On social media, politicians, political parties, and other political actors are ingrained as nodes in the network that defines the medium (cf. Karlsen Citation2015), and politicians are typically active in social media, sharing, discussing, and criticizing news stories (e.g. Bene Citation2017b; Karlsen and Enjolras Citation2016; Stier et al. Citation2018). Party affiliation of politicians most likely cue familiar heuristics when evaluation the news story (cf. Metzger, Flanagin, and Medders Citation2010; Metzger and Flanagin Citation2015). Hence, if politicians share a news story on social media this might increase perceptions of news being politically biased, as well as general perceptions of credibility. Hence, in regards to intermediary sender, we formulate the following hypothesis H2: The distribution of a news story through Facebook by a party politician will decrease perceptions of credibility in a news story to a greater extent than when shared by a non-politician.

The effect of a politician as an intermediary will, however, most likely be contingent on the political attitudes and the party political support of the audience. Previous research has found clear sender effects related to politicians and party politics: people react differently to messages based on the party affiliation of the sender based on their own party political sympathies (Slothuus and de Vreese Citation2010). In a similar manner, we would expect that people are less critical of a news story shared by a politician from a party they support. Hence, in regards to the intermediary sender, we also formulate a the following hypothesis, H3: The effect of the partisan treatment will be modified by political support for the politician’s party.

Finally, the effect of an intermediary such as Facebook might also depend on the initial trust of the original source. As mentioned, people trust some news media outlets to a greater extent than others (Newman et al. Citation2018). However, as we see it, two opposite outcomes are both theoretically plausible based on media credibility, and we refrain from formulating any clear expectations. First, it is possible that Facebook will have a stronger effect when trust in the initial source is high. Then the scope for the intermediary to decrease the level of trust and increase perceptions of political bias is greater. However, it is also likely that when the original news site is trusted to a great extent, trust in the original source will trump people’s distrust in Facebook. Hence, in regards to news media credibility, we refrain from formulating a clear hypothesis and formulate the following research question (RQ1): Do trust in the original news source influence the effect of intermediary distribution on news story credibility?

Research Design

To investigate the effect of Facebook sharing on perceptions of news stories, we report on an experiment embedded in round II of the 2017 Norwegian Election Campaign Panel Study (NECS). The Norwegian context offers a good research setting for this type of experiment. Most importantly, Facebook use has been widespread for several years (Enjolras et al. Citation2012), and in 2017 about 70% of the population used the platform every day.Footnote3 People also report that they consume news on Facebook (Haugsgjerd, Karlsen, and Aalberg Citation2019) in a comparatively high extent (Newman et al. Citation2018, 11). Level of trust in news is also comparatively high in Norway, with 47% trusting news most of the time (Newman et al. Citation2018, 17). In 2020, forty per cent in Norway was concerned about what is real and what is fake on the Internet, placing Norway amongst the less concerned countries participating in the digital news report project (Newman et al. Citation2020, 18).

The 2017 NECS is a study surveying respondents before, during, and immediately after the election campaign. The data collection was web based, using Statistics Norway’s tools. The sample is based on a national probability sample of 10,000 individuals drawn from the official Norwegian citizen register. A total of 4038 respondents participated in round I of the panel survey. The experiment was included in the second round of the survey, in the field from August 15 to August 22, three to four weeks prior to election day. A total of 2026 respondents participated in round II.Footnote4

Experimental Set up

We base our approach on a classic experimental design where we expose a control group to a news story on an online news site and expose treatment groups to the same news story shared on Facebook. In the Facebook condition, we vary characteristics about the individual sharing the story. The Facebook condition therefore includes three manipulations. In the first manipulation subjects are exposed to a news article because it has been shared by a “neutral” person, who can be perceived as a Facebook-friend of a Facebook-friend. In the second and third manipulations, the same individual is identified as a politician, from the Labour party or the Conservative party, respectively. The treatment was presented to the respondents as pictures (they were not redirected to a different website).Footnote5

The treatment is based on an actual news story from the national broadcaster NRK’s website, but the wording was, for legal reasons, slightly adjusted by the research team. The exact same news story was presented within the visual platforms of the public broadcaster NRK, and main commercial national broadcaster TV 2 (see Figure A1). The individual sharing the news story was a fictional individual (Knut Hagen). The name and the news story were similar in all treatment groups, and the Labour Party and the Conservative Party symbols were included in the profile picture presented to treatment groups 3–4 and 5–6, respectively. The treatment was pretested by the method group at Statistics Norway, as a group of respondents was exposed to the experiment and thereafter in-depth interviewed. The main adjustment after the pre-test was that the party names (and symbols) were increased to make sure that the respondents observed them. The topic of the news story was purchasing power. To some extent this is a valence issue, everybody wants to improve purchasing power. However, it is also related to party politics as unions, closely related to the Labour Party, wants to ensure an increase in purchasing power.

We divided the control group in two: one was exposed to the news story on the public broadcasters news site (nrk.no), and the other was exposed to it on the commercial broadcasters’ news site (tv2.no). This was done to test if any effects depend on the initial trust in the news platform (media credibility), as the public broadcaster traditionally has greater general trust than the commercial broadcaster. To sum up, we hold the news story itself (and thereby source credibility–trust in the provider of the information); and news media (and thereby media credibility–trust in the medium conveying the message), constant, and are able to study the effect of the intermediary—Facebook—as well as characteristics with the individual sharing the news story on Facebook ().

Table 1. Control and treatment groups in the experiment.

Dependent Variables and Moderators

The main dependent variable is the news credibility index consisting of two items. One item measuring trust in the information presented in the news story and a second item measuring perceptions of political bias in the news story. The two items correlate considerably (.57) and a factor analysis returns one dimension (eigenvalue 1.6). The index ranges from 1-7, and Cronbach’s Alpha is high (.72). The question wording for the two items in the index was as follows: “On a scale from 1–7 where 1 indicates ‘to a great extent’ and 7 indicates ‘to a very little extent’, to what extent do you trust the information in this news article?”. For political bias: “On a scale from 1–7 where 1 indicates ‘totally neutral’ and 7 indicates ‘very biased’, do you think that the news story is politically neutral or politically biased?” Prior to these two questions, the respondents were asked how interesting they found the news story.

Based on our hypothesis, we are interested in two types of moderator variables: support for the Conservative Party and support for the Labour Party. We utilize a modified version of the propensity to vote measure (Franklin Citation2004): “On a scale from 0 to 10, where 0 means ‘not at all likely’ and 10 means ‘very likely’, how likely is it that you will ever vote for …” The Conservative Party and the Labour Party were two of, in all, 10 alternatives. We used the PTV measures from the same round of the study, asked prior to the experiment ().

Table 2. Descriptive statistics.

Data Description

Respondents were randomly allocated to the control or treatment groups. Gender and age groups are distributed evenly in all groups, suggesting that randomization was successful (). However, men are overrepresented in Control group 1. Although the difference is not very big, it nevertheless makes it necessary to make sure that treatment effects are not due to gender differences. Hence, we have controlled all treatment effects for gender. The results show that the effect of the treatment is only marginally reduced, typically .01 points on the scale from 1–7, and does not influence the substantial effect of the treatment. Hence, we do not report the controls in the main analysis, but we report the effect of the treatment controlled for gender, education, political interest, and news consumption in Table A2, Appendix, Supplementary material. The control variables do not influence the size of the treatment effects in any substantial way.

Table 3. Control and treatment groups. Descriptive statistics.

Results

In we show the results of nine regression models testing the hypothesis formulated above. We begin by testing the main expectation that the sharing of a news story on Facebook will decrease the credibility in a news story (hypothesis 1). Model one show the effect in all treatment groups combined. The intercept reflects the mean on the scale for the control group, and the coefficient indicates the extent the mean in the treatment group differs from the control group.

Table 4. Experimental effects. Effect of treatments on news credibility index (1-7). OLS regression. Entries are b-coefficients, st. error in parenthesis.

As expected, the distribution of news through Facebook clearly affects credibility perceptions. The combined treatment effect is more than half a point on the credibility index ranging from 1-7 (Model 1). The effect is substantial and clearly significant, constituting, 7.6 standard deviations. Hence, hypothesis one is supported, undoubtedly, Facebook sharing reduce the overall credibility people have in the news story significantly. However, it could be that the partisan treatments drives the whole effect. Hence, to disentangle the overall treatment effect we report the effect of the nonpartizan and partisan treatment (Model 2). The nonpartizan treatment has a clear significant effect, it decreases the overall credibility by one third of a point. Still, this effect is only about half the size of the partisan effect. Indeed, the difference between the nonpartizan and the partisan effect is statistically significant (see Table A3, Appendix, Supplementary material). Moreover, the politician’s party affiliation do not seem to matter, as the effect is of similar size for both the conservative and labour treatment.

Above we nevertheless argued that the party affiliation of the politician sharing the news story would be contingent on supporter of the politician’s party—so-called intermediary-sender effects. The Conservative and Labour parties are the main opponents in Norwegian politics, so supporters of one party should overall be somewhat unsympathetic towards the other party. Although, as described, the effect of two party treatments are clearly significant overall, we nevertheless expect that the effect is stronger for people that do not sympathize with the politician’s party than people who support the party (H3). In order to test this, we included an interaction term between the partisan treatment and general support for the party (Models 4-7). Support for the party is based on the much-used propensity to vote measure (see above).

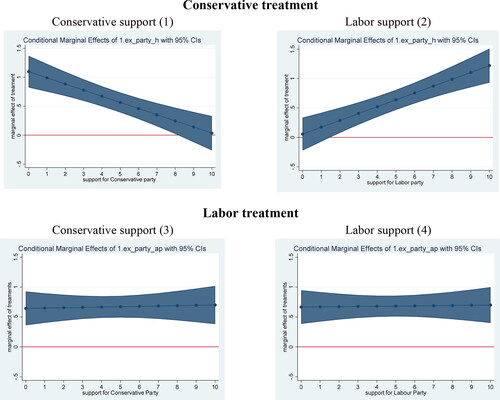

Interestingly, the interaction terms are clearly significant for the Conservative Party treatment, but not for the Labour Party treatment. Hence, the effect of political intermediary-senders seems to be contingent on support for the party, but that it again depends on what party. In , we visualize the interaction effects and show the marginal effect of the two partisan treatments conditioned on support for either the Conservative Party or the Labour Party.

Figure 2. Conditional marginal effects of Labour and Conservative treatment on trust in the information, conditioned on support for the Labour Party and the Conservative Party. (0 = definitely not vote for the party, 10 = definitely vote for the party).

The figure shows clearly how the effect of the Conservative partisan treatment is contingent on respondents’ support for the two parties. Let us describe the results in a step by step manner. Conservative supporters getting message from Conservative politician are not affected by the treatment (1), but Labour supporters getting message from Conservative politician are (2). The Labour treatment on the other hand is, as mentioned, not contingent on respondents’ party support: Conservative supporters getting message from a Labour politician (3), are affected to the same extent as Labour supporters getting a message from a Labour politician (4). Here the effect is around .7 across support for both parties.

This can appear puzzling, but if we take a closer look at the data, we find that this result is related to the general relationship between political ideology and message credibility perceptions. Conservative supporters find the news story less credible than Labour supporters at the outset, when it is presented at the original news site, echoing the relationship between trust in news and political ideology found in previous studies. Hence, the effect of the Labour treatment is similar for Conservative and Labour supporters, but Conservative supporters are influenced from a higher level of mistrust (see Figure A2 in appendix).

nevertheless suggest that Labour supporters are more influenced by the Conservative treatment (picture 2) compared to the Labour treatment (picture 4). This is confirmed by two regression analyses restricted to the two party supporters, one for Labour supporters and one for Conservative supporters (Table A3, Appendix, Supplementary material). The nonpartizan, Conservative and Labour treatments all have considerable effect on the Labour supporters. However, the Conservative treatment has a significantly stronger effect. Only the Labour party treatment has an effect on Conservative supporters. In conclusion, there are indeed intermediary-sender effects on Facebook, and H3 is supported. However, such intermediary effects are entangled in the rather complex relationship between trust and political ideology.

Finally, we turn to the proposition that the original news source might influence the effect of Facebook sharing (, model 8 and 9). Theoretically, we argued that two scenarios were likely: Facebook could have a stronger effect when the initial source is really trusted as the potential to influence is greater. However, trust in the original source could also trump the distrust in Facebook. As described above, the original news source (NRK or TV2) was visible for all treatment groups (see Figure A1). We investigate the effect of original source (Model 8) and if the treatment effect is contingent on the news source through an interaction term (Model 9). Indeed, people consider the new story more credible when presented on the public broadcaster website (NRK), but the interaction term between news source and treatment in Model nine is not significant. Hence, the effect of the treatment is not contingent on news source. Separate analysis of groups exposed to either NRK or TV2 as the original source show that the effect is stronger for the groups exposed to NRK (Table A5, Appendix, Supplementary material).Footnote6 Although the difference is not statistically significant, it arguably suggest that the credibility of the original news source do not hinder the negative influence of social media on news credibility.

Discussion and Conclusion

In this article, we have investigated if the disruptive change in news consumption found in most established democracies (Newman et al. Citation2020; Van Aelst et al. Citation2017) influences news story perceptions. More precisely, we have studied if the distribution of a news story through Facebook influence the credibility of the news story. All in all the results suggest that perception of a news story is influenced by Facebook distribution; people find the news less credible when they are exposed to it through Facebook. Hence, hypothesis one was supported.

The effect of Facebook distribution is stronger when the news story is shared by a politician. Although the effect was clearly significant in all treatment groups, the partisan effect was twice the size of the nonpartizan treatment. Hence, also hypothesis two received clear support. At the outset, there was no difference between the effect of the Conservative and Labour treatments. However, the results revealed clear intermediary-sender effects, rooted in a somewhat complex relationship between perceptions of message credibility and political ideology. First, the Conservative partisan treatment found a clear sender effect: Conservative supporters were not influenced by Facebook distribution when the story was shared by a politician from the Conservative Party, while the effect on Labour supporters was very strong. Second, however, the effect of the Labour partisan treatment was not contingent on support for the two parties. As discussed above, these results must be understood in light of the relationship between political ideology and trust in news; Conservative supporters were less influenced than Labour supporters because Conservative supporter already found the news story less credible when it was presented on the original news site. The Conservative treatment did, however, have a stronger effect on Labour supporters than the Labour treatment had, indicating that intermediary sender effects are in play for Labour supporters as well. Hence, hypothesis three was also supported, but the relationship was not as straightforward as expected.

The results related to the intermediary sender has two implications worth discussing. First, the results support existing empirical evidence emphasizing the importance of the relationship between the intermediary sender and the audience when it comes to effects on news credibility (e.g. Bene Citation2017a; Sterrett et al. Citation2019; Turcotte et al. Citation2015). If people are sympathetic to the intermediary sender, any negative effect is smaller, or non-existent. Second, and relatedly, the results imply that the intermediary-sender contributes not only to “agenda setting” in social networks, but also to how shared news stories are perceived, and this could also increase tendencies towards polarization. Although social media curation might curb tendencies towards fragmentation and echo chambers (Taneja, Wu, and Edgerly Citation2018; Thorson and Wells Citation2016), people seem to some extent to disregard news shared by someone they perceive to differ from their own political beliefs. To investigate such possibilities should be of great importance for future research.

In regards to trust in the original source, we had no clear expectation, but considered it plausible that Facebook distribution could on the one hand remove much of the credibility of the original news source, but on the other hand also considered it plausible that trust in the original source could trump the distrust in Facebook. Most importantly, effects were found regardless of the original source. The effect did not differ significantly between groups exposed to the public broadcaster (NRK) and the commercial alternative (TV 2). Moreover, a closer analysis of the data found that the effect was consistently stronger for the groups exposed to the treatment with NRK as the original source. This resonates well with Sterrett and colleagues (Citation2019) finding that a trusted news outlet did not influence to what extent respondents trusted information in a news story distributed on social media.

As with all experiments, the experiment reported on in this article also has limitations in regards to external validity. When people are exposed to news stories on Facebook, it is often shared by someone they know. If they trust this person, they are more likely to trust the news story as well (Bene Citation2017a; Sterrett et al. Citation2019; Turcotte et al. Citation2015). Due to the nature of the data collection (national representative survey), we were unable to include friends as the individual sharing the news story. Still, exposure to news on Facebook is by far restricted to what close friends share as “people get information not from a small network of homogenous users, but from larger diverse networks that consists of friends of friends” (Taneja, Wu, and Edgerly Citation2018, 1794). When designing the experiment, we did consider using well- known politicians as intermediary senders. However, we were concerned that respondents’ strong opinions about these individuals would complicate the interpretations of the experimental effects. Still, experiments using well-known politicians should be an interesting avenue for future research, but will probably need pre-treatment items measuring opinions about the intermediary senders (Sterrett et al. Citation2019).

We only tested the effect using one single message. This was done because it was important to avoid order effects (particularly fatigue due to the panel design). In this case, using a single measure and between groups design should therefore not have influenced the results, whereas a within group design could have caused order effects. Although the aim of the study was not related to the content of this specific message (the country’s economic development), but rather to the type of message (Facebook distribution), it may be argued that the effects could also be influenced by the content of the message distributed. Moreover, contextual factors might also influence the results. Norway has high general levels of trust, and the comparatively low worry about fake news might lead us to expect even stronger effects in other less trusting contexts. However, this is an empirical question. Thus, replications are valuable and we encourage similar studies to support the results of our experiment (see McEwan, Carpenter, and Westerman Citation2018).

Our results are also at the outset limited to Facebook, and not all other types of social media like Twitter, Instagram, and so on. Still, Facebook is the most widely used social media, and is also increasingly important for news consumption (e.g. Newman et al. Citation2018). Hence, the platform is a highly relevant social media for an investigation into these matters. Studies that compare the effect of different types of intermediary platforms should be an interesting avenue for future research.

Trust in news depends on several factors. Previous research has focussed on characteristics with the message, the source, and the media, as well as individual level characteristics of the news consumers. The results presented in this article adds evidence to the proposition that in today’s hybrid communications systems, social media platforms (the intermediary), as well as the intermediary-sender, must be included as factors influencing people’s trust in news. They act as heuristic cues for the audience when evaluating the credibility of the news story (cf. Metzger, Flanagin, and Medders Citation2010; Metzger and Flanagin Citation2015; Kang et al. Citation2011). These results are both reassuring and unsettling from a democratic perspective. As Coleman (Citation2012) argues, citizenship only works on the basis of common knowledge, and this makes trust in news an essential aspect of modern democracies. If an increasingly common way of consuming news indeed decrease news credibility, this can increase tendencies of citizens not trusting that their fellow citizens are well informed about developments in society. On the other hand, a total belief or trust in news are certainly not healthy for democracy. As reports of fake news are increasing, it can be considered healthy for democracy that people are sceptical towards the news they consume through intermediaries such as Facebook. And importantly, although the effect of Facebook distribution was strong and significant, it is not the case that people really distrust news they read on Facebook, at least not when the original news source is visible. Still, if scepticism is the new normal, the consequences of social media news sharing for long-term trust in journalism and news production can be severe.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (593 KB)Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 We use social media to denote online media for social interaction, including what is often referred to as social networking sites that focus on building online social networks based on shared interests or activities.

2 We adhere to the tradition that do not differentiate between these concepts.

4 The election survey also included questions about important issues, issue ownership, and news consumption. These questions were asked in all four rounds.

5 See Figure A1, Supplementary material.

6 The mean in the experimental groups exposed to NRK are still, however, lower than in experimental groups exposed to TV2.

References

- Allcott, Hunt, and Matthew Gentzkow. 2017. “Social Media and Fake News in the 2016 Election.” Journal of Economic Perspectives 31 (2): 211–236.

- Anspach, Nicolas M. 2017. “The New Personal Influence: How Our Facebook Friends Influence the News we Read.” Political Communication 34 (4): 590–606.

- Bene, Marton. 2017a. “Influenced by Peers: Facebook as an Information Source for Young People.” Social Media + Society 3 (2): 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1177/2056305117716273

- Bene, Marton. 2017b. “Sharing is Caring! Investigating Viral Posts on Politicians’ Facebook Pages during the 2014 General Election Campaign in Hungary.” Journal of Information Technology & Politics 14 (4): 387–402.

- Bennett, Stephen E., Staci L. Rhine, Richard S. Flickinger, and Lance M. Bennett. 1999. “Video Malaise’ Revisited: Public Trust in Media and Government.” Harvard International Journal of Press/Politics 4 (4): 8–23. https://doi.org/10.1177/1081180X9900400402.

- Blöbaum, Bernd. 2014. “Trust and Journalism in a Digital Environment: Working Paper.” Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism. Oxford, UK: Oxford University.

- Blumler, Jay G. 2016. “The Fourth Age of Political Communication.” Politiques de Communication 1: 19–30.

- Chadwick, Andrew. 2013. The Hybrid Media System: Politics and Power. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

- Coleman, Stephen. 2012. “Believing the News: From Sinking Trust to Atrophied Efficacy.” European Journal of Communication 27 (1): 35–45. https://doi.org/10.1177/0267323112438806.

- Dahl, Robert. 1998. On Democracy. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- Dalton, Russel J., Paul A. Beck, and Robert Huckfeldt. 1998. “Partisan Cues and the Media: Information Flows in the 1992 Presidential Election.” American Political Science Review 92 (1): 111–126.

- Elvestad, E., and Angela Phillips. 2018. “Misunderstanding News Audiences.” Seven Myths of the Social Media Era. London: Routledge.

- Enjolras, Bernard, Rune Karlsen, Kari Steen-Johnsen, and Dag Wollebaek. 2012. Liker – Liker Ikke. Oslo: Cappelen Damm.

- Evans, Jonathan. 2008. “Dual-Processing Accounts of Reasoning, Judgment, and Social Cognition.” Annual Review of Psychology 59 (1): 255–278.

- Eveland, William P., and Dhavan V. Shah. 2003. “The Impact of Individual and Interpersonal Factors on Perceived News Media Bias.” Political Psychology 24 (1): 101–117.

- Eysenbach, Gunther, and Christian Kohler. 2002. “How Do Consumers Search for and Appraise Health Information on the World Wide Web? Qualitative Study Using Focus Groups, Usability Tests, and in-Depth Interviews.” BMJ (Clinical Research ed.) 324 (7337): 573–577.

- Fisher, Caroline. 2016. “The Trouble with ‘Trust’ in the News.” Communication Research and Practice 2 (4): 451–465.

- Flanagin, Andrew, and Miriam J. Metzger. 2000. “Perceptions of Internet Information Credibility.” Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly 77 (3): 515–540. https://doi.org/10.1177/107769900007700304.

- Flanagin, Andrew, and Miriam J. Metzger. 2017. “Digital Media and Perceptions of Source Credibility in Political Communication.” In The Oxford Handbook of Political Communication, edited by Kate Kenski and Kathleen Hall Jamieson, 417–435. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Fletcher, Richard, and Sora Park. 2017. “The Impact of Trust in the News Media on Online News Consumption and Participation.” Digital Journalism 5 (10): 1281–1299.

- Franklin, Mark N. 2004. Voter Turnout and the Dynamics of Electoral Competition in Established Democracies since 1945. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Gronke, Paul, and Tomothy E. Cook. 2007. “Disdaining the Media: The American Public’s Changing Attitudes toward the News.” Political Communication 24 (3): 259–281.

- Hanitzsch, Thomas, Arjen van Dalen, and Nina Steindl. 2018. “Caught in the Nexus: A Comparative and Longitudinal Analysis of Public Trust in the Press.” The International Journal of Press/Politics 23 (1): 3–23. https://doi.org/10.1177/1940161217740695.

- Haugsgjerd, Atle, Rune Karlsen, and Toril Aalberg. 2019. Velgere i Valgkamp: øker Politiske Forskjeller? in Valg og Valgkamp, edited by Johannes Bergh and Bernt Aardal, 81–102. Oslo: Cappelen Damm.

- Hovland, Carl I., and Walter Weiss. 1951. “The Influence of Source Credibility on Communication Effectiveness.” Public Opinion Quarterly 15 (4): 635–650.

- Johnson, Thomas J., and Barbara K. Kaye. 2010. “Still Cruising and Believing? An Analysis of Online Credibility across Three Presidential Campaigns.” American Behavioral Scientist 54 (1): 57–77. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002764210376311.

- Jones, David A. 2004. “Why Americans Don’t Trust the Media: A Preliminary Analysis.” Harvard International Journal of Press/Politics 9 (2): 60–75.

- Kang, Hyunjin, Keunmin Bae, Shake Zhang, and S. Shyam Sundar. 2011. “Source Cues in Online News: Is the Proxamite Source More Powerful than the Distal Source?” Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly 88 (4): 719–736. https://doi.org/10.1177/107769901108800403.

- Karlsen, Rune. 2015. “Followers Are Opinion Leaders: The Role of People in the Flow of Political Communication on and beyond Social Networking Sites.” European Journal of Communication 30 (3): 301–318.

- Karlsen, Rune, and Bernard Enjolras. 2016. “Styles of Social Media Campaigning and Influence in a Hybrid Political Communication System. Linking Candidate Survey Data with Twitter Data.” The International Journal of Press/Politics 21 (3): 338–357.

- Kiousis, Spiro. 2003. “Public Trust or Mistrust? Perceptions of Media Credibility in the Information Age.” Mass Communication and Society 4 (4): 381–403.

- Kohring, Matthias, and Jörg Matthes. 2007. “Trust in News Media: Development and Validation of a Multidimensional Scale.” Communication Research 34 (2): 231–252.

- Ladd, J. M. 2012. Why Americans Hate the Media and Why It Matters. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Lazer, David M. J., Matthew A. Baum, Yochai Benkler, Adam J. Berinsky, Kelly M. Greenhill, Filippo Menczer, Miriam J. Metzger, et al. 2018. “The Science of Fake News: Addressing Fake News Requires a Multidisciplinary Effort.” Science (New York, N.Y.) 359 (6380): 1094–1096.

- Lee, Tien-Tsung. 2010. “Why They Don’t Trust the Media: An Examination of Factors Predicting Trust.” American Behavioral Scientist 54 (1): 8–21. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002764210376308.

- McEwan, Bree, Christopher J. Carpenter, and David Westerman. 2018. “On Replication in Communication Science.” Communication Studies 69 (3): 235–241..

- Metzger, Miriam J., and Andrew J. Flanagin. 2015. “Psychological Approaches to Credibility Assessment Online.” The Handbook of the Psychology of Communication Technology 32 (445): 445–466.

- Metzger, M. J., A. J. Flanagin, K. Eyal, D. R. Lemus, and R. M. McCann. 2003. “Credibility for the 21st Century: Integrating Perspectives on Source, Message, and Media Credibility in the Contemporary Media Environment.” Communication Yearbook 27 (1): 293–336.

- Metzger, Miriam J., Andrew Flanagin, and Ryan B. Medders. 2010. “Social and Heuristic Approaches to Credibility Evaluation Online.” Journal of Communication 60 (3): 413–439.

- Miller, Joanna M., and Jon A. Krosnick. 2000. “News Media Impact on the Ingredients of Presidential Evaluations: Political Knowledgeable Citizens Are Guided by a Trusted Source.” American Journal of Political Science 44 (2): 301–315.

- Newman, Nic, Fletcher, Richard Anne Schulz, Simge Andı, Rasmus, and K. Nielsen. 2020. Reuters Institute Digital News Report 2020. Oxford: Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism.

- Newman, Nic, R. Richard Fletcher, A. Kalogeropoulos, D. A. L. Levy, and Rasmus K. Nielsen. 2018. Reuters Institute Digital News Report 2019. Oxford: Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism.

- Newton, Ken. 2017. “Political Trust and the Mass Media.” In Handbook of Political Trust, edited by S. Zmerli, and T. van der Meer, 353–372. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

- Nielsen, Rasmus Kleis, and Kim Christian Schrøder. 2014. “The Relative Importance of Social Media for Accessing, Finding, and Engaging with News: An Eight-Country Cross-Media Comparison.” Digital Journalism 2 (4): 472–489.

- Oeldorf-Hirsch, Anne, and Christina L. DeVoss. 2020. “Who Posted That Story? Processing Layered Sources in Facebook News Posts.” Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly 97 (1): 141–160.

- PEW. 2016. “The Modern News Consumer.” Pew Research Center. http://www.journalism.org/2016/07/07/the-modern-news-consumer/

- Rieh, Soo Y, and Davis R. Danielson. 2002. “Credibility: A Multidisciplinary Framework.” Annual Review of Information Science and Technology 41 (1): 307–364.

- Slothuus, Rune, and Claes H. de Vreese. 2010. “Political Parties, Motivated Reasoning, and Issue Framing Effects.” The Journal of Politics 72 (3): 630–645.

- Sterrett, David, Dan Malato, Jennifer Benz, Liz Kantor, Trevor Tompson, Tom Rosenstiel, Jeff Sonderman, and Kevin Loker. 2019. “Who Shared It?: Deciding What News to Trust on Social Media.” Digital Journalism 7 (6): 783–801.

- Stier, Sebastian, Arnim Bleier, Haiko Lietz, and Markus Strohmaier. 2018. “Election Campaigning on Social Media: Politicians, Audiences, and the Mediation of Political Communication on Facebook and Twitter.” Political Communication 35 (1): 50–74.

- Tandoc, Edson. 2019. “Tell Me Who Your Sources Are: Perceptions of News Credibility on Social Media.” Journalism Practice 13 (2): 178–190. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/17512786.2017.1423237.

- Taneja, Harsh, Angela Wu, and Stephanie Edgerly. 2018. “Rethinking the Generational Gap in Online News Use: An Infrastructural Approach.” New Media & Society 20 (5): 1792–1812. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444817707348.

- Thorson, Kjerstin, and Chris Wells. 2016. “Curated Flows: A Framework for Mapping Media Exposure in the Digital Age.” Communication Theory 26 (3): 309–328.

- Tsfati, Yariv, and Gal Ariely. 2014. “Individual and Contextual Correlates of Trust in Media across 44 Countries.” Communication Research 41 (6): 760–782. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093650213485972.

- Tsfati, Yariv, and Jonathan Cohen. 2005. “Democratic Consequences of Hostile Media Perceptions: The Case of Gaza Settlers.” Harvard International Journal of Press/Politics 10 (4): 28–51. https://doi.org/10.1177/1081180X05280776.

- Turcotte, Jason, Chance York, Jacob Irving, Rosanne M. Scholl, and Raymond J. Pingree. 2015. “News Recommendations from Social Media Opinion Leaders: Effects on Media Trust and Information Seeking.” Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication 20 (5): 520–535.

- Vallone, Robert P., Lee Ross, and Mark L. Lepper. 1985. “The Hostile Media Phenomenon: Biased Perception and Perceptions of Media Bias in Coverage of the Beirut massacre.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 49 (3): 577–585.

- Van Aelst, Peter, Jesper Strömbäck, Toril Aalberg, Frank Esser, Claes de Vreese, Jörg Matthes, David Hopmann, et al. 2017. “Political Communication in a High-Choice Media Environment: A Challenge for Democracy?” Annals of the International Communication Association 41 (1): 3–27.

- Zaller, J. 1992. The nature and origins of mass opinion. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.