Abstract

The insular usage of media sources is a common tool for populist actors to position themselves in relation to the social mainstream and to hold up their claim of creating a counter public. In this article, we traced these dynamics by analysing differences in the insularity of right-wing populist parties’ source repertoires compared to other parties, i.e., the exclusivity of the sources used by populist politicians. By analysing the linking practices of parliamentarians in seven EU countries and Switzerland on Twitter we were able to test the impact of political and media context on these practices. In a second step, we asked to what extent the insularity of sources allows us to draw conclusions on the insularity of topics, i.e., whether right-wing populists used a broad or narrow topic agenda. Our key findings: In countries with high levels of media trust and low levels of polarization, the populist source repertoire features a comparatively low insularity, except for politically marginalized populist parties that use more insular sources. Regardless of the insularity of source use, right-wing populist parties in almost all countries feature a high degree of topic insularity, making a narrow topic agenda the cross-national characteristic of right-wing populist communication.

Introduction

The rise of right-wing populist parties in recent years has been linked to the growing relevance of social media as news environments (Ernst et al. Citation2019; Krämer Citation2017) and the emergence of new (hyper)partisan media (Newman et al. Citation2018; Rae Citation2021), at times also described as alternative media (Holt, Figenschou, and Frischlich Citation2019; Holt Citation2020) with an affinity to populism (Müller and Schulz Citation2021). Within social media, right-wing populist parties strategically link to specific news sources, aiming to create news environments friendly to the causes and needs of their followers. Through this, the relationship between populist actors and partisan media may at times appear to be symbiotic as both sets of actors create public attention for each other, lend each other legitimacy, and build loyalty among supporters/recipients by jointly offering them an identity (Haller Citation2020; Starbird Citation2017).

Though the linking practices of right-wing populist parties on social media have lately received increasing scholarly attention, most of the research is limited to single case studies, and often the single case is the US with its very highly polarized two-party system and hyper-commercialized digital media system (Benkler, Faris, and Roberts Citation2018). This greatly impedes more general conclusions on the linking practices of right-wing populist actors within multi-party systems and comparatively stable media systems. According to Heft et al. (Citation2020), one of the few comparative analyses in the field, these media and political contexts determine variations in the characteristics of right-wing media in different countries. Hence, they should, in turn, also impact the linking practices of right-wing populist actors on social media by impacting the partisan sources available to them.

It is thus the first aim of this study, to systematically explore across different political and media systems which sources right-wing populist actors share on social media, and whether these are popular among a wide range of political actors, or more insular sources with whom the populists have formed somewhat symbiotic relationships. To this end, we analyse the linking practices of parliamentarians in seven EU countries and Switzerland (4,368,030 tweets by 2,229 parliamentarians of 141 different parties). Based on the identified media repertoires, we measure the insularity of sources used by populist actors – i.e., whether certain sources are used more exclusively by right-wing populist politicians’ than by politicians from other parties in the same country. This will also allow us to assess under which conditions of the political and media system right-wing populist actors link to specific sources outside the mainstream or whether their linking practices are actually quite similar to those from the other parties.

In a second step, we also investigate whether these linked sources are used by right-wing populists to promote a broad topic agenda shared with many other political actors or an insular, narrow topic agenda focussing on issues outside of the mainstream topic agenda.

This way, we can show that the degree of insularity in right-wing populist source repertoires is indeed highly dependent on contextual factors, such as political polarization, general trust in the media or the position of the populist party within the political system. We can identify countries where right-wing populist parties stand out by their comparatively insular source use (e.g., Italy, France, the Netherlands, or Germany); but we also find countries where right-wing populist parties’ source repertoires do not differ significantly from those of other parties (e.g., Denmark, Austria, or Switzerland).

Irrespective of how much countries differ in terms of populist source repertoires, all the right-wing populist parties under study display topic insularity which diverges significantly from the average of the other parties (with the exception of Spain). From this comparison, we can conclude that right-wing populist agendas are mostly characterized by not only comparatively low topic diversity, but also by a focus on topics outside of the general public discourse.

Theoretical Framework and State of Research

From the theoretical perspective of the “networked public sphere” (Benkler Citation2006), the position of a political party within the digital public sphere – at the fringes or in the core – can manifest itself through its linking practices to other political actors and sources. Various studies in the political blogosphere have found that the practice of linking is mostly affirmative, meaning that referencing via hyperlinks mostly indicates a closeness between the entity that links and the entity that is being linked (Adamic Citation2008, 234; Park and Thelwall Citation2008). In general, this corresponds to models of content selectivity, in which “affirmation of beliefs and values, or, though probably less often, the opportunity to counterargue or belittle opposing perspectives” (Slater Citation2007, 299) are important drivers. It seems logical, then, that the sharing of newsworthy content is often used to build a relationship (Ihm and Kim Citation2018). The hyperlink can thus also be “reflecting political affiliations” or be interpreted as a “sign of political homophily” (De Maeyer Citation2013, 740–741). Against this background, the linking practice of political actors, or a certain group of actors (for example, members of a certain party), is a relevant object of research. After all, this repertoire of linked sources, their media repertoire (Hasebrink and Popp Citation2006), reflects an identity offered by a political actor and thus anticipates his or her followers’ expectations. In particular for right-wing populist parties, this repertoire is likely not be limited to traditional news media, but also encompasses a wide range of alternative news sources, including blogs or webpages of political actors with no claims to journalistic professionalism (even though they may still be perceived as “news sites” by the social media users that encounter them).

The starting point of our analysis is the insularity of right-wing populist actors’ media repertoires. The measure of insularity shows how a media repertoire relates to the media use of all other actors in a sample. Low insularity occurs when an actor links to many media sources that largely overlap with other actors’ media repertoires. By contrast, high insularity describes an actor whose media repertoire is focussed on only a few sources to which other parties rarely link. There are various reasons why political groups create repertoires with high source insularity, i.e., have very exclusive ties to certain media, for example ideological proximity to outlets, a shared regional or thematic focus, etc.

Looking at research on right-wing populist actors’ source use, two opposing trends regarding the expected insularity of their media repertoires can be identified:

Demarcation and Alternative Identity

As researchers examine clusters within the digital public sphere that result from linking practices, it becomes clear that there are indeed cross-connections between political camps, but they vary in intensity. Clusters that can be located on the political right tend to be more isolated – asymmetrically polarized spaces of discourse (Barberá et al. Citation2015) with high insularity (Benkler, Faris, and Roberts Citation2018; Giglietto et al. Citation2019) emerge. Nuclei of particularly isolated clusters are often media outlets, which, analogous to right-wing populist ideology, see themselves as opposing the “corrupt elite” (Mudde Citation2004, 543). According to Holt (Citation2020), media that enter this form of partisan bond can also be described as alternative media, since they produce counter-publics and thus offer a populist identity. Studies show that homogeneous, affirmative media have an identity-building effect, especially for individuals who hold extreme right-wing populist ideologies (Dvir-Gvirsman Citation2017). In line with this finding, recent studies from various countries observed how right-leaning populist alternative media have gained influence (Aalberg et al. 2017; Heft et al. Citation2020; Müller and Schulz Citation2021; Newman et al. Citation2018).

The loyal readership of these mostly digital media has a very high degree of online affinity (Newman et al. Citation2018) and is closely networked via social media. Analyses of the relationships of far-right groups on Twitter show that like-minded, stable communities have formed in several European countries – and the members of these groups are often also associated with populist parties, for example, the United Kingdom Independence Party (UKIP) (O’Callaghan et al. Citation2013). Starbird (Citation2017) calls this triangle of populist actors, alternative partisan media, and radical communities ‘Alternative Media Ecosystems’.

Complicity and Legitimacy

In contrast to the isolation described above is the trend of “paradoxical populism” (Haller and Holt Citation2019): While populists accuse the mainstream media of acting against the interests of the “pure people” (Nygaard Citation2019), they seek proximity to these media to increase their public visibility and perceived legitimacy and to boost the salience of certain issues (Mazzoleni Citation2008). In doing so, they benefit from an often-unintentional complicity of the news media, as the commercialized media’s “production logic” actually converges with the populist actors’ goals (Mazzoleni Citation2008, 54–55). In high-choice media environments, this interdependence is evident, for example, in populist actors’ linking practices – as secondary gatekeepers (Singer Citation2014) they support their own statements by sharing articles from mainstream media (Bachl Citation2018; Haller and Holt Citation2019), while the media, in turn, profit from the high level of engagement that populist parties trigger (Dittrich Citation2017). Accordingly, in their analysis of linking practices of right-wing online news sites, Heft et al. (Citation2021) found no insulated, alternative sphere, but rather observed that the emerging digital news ecology on the right seeks to link up to the broader information environment across borders (cf. also Kaiser, Rauchfleisch, and Bourassa Citation2020).

These two forms of linking practices between right-wing populists and media differ in terms of their expected source insularity. While the first practice leads to homogeneous and self-contained media repertoires with a high degree of insularity, a proximity to mainstream discourse is more likely to result in a low degree of insularity, with media repertoires that overlap largely with those of other actors. There is, as yet, no comparative evidence which of these forms predominates in which countries – therefore, we ask:

Research question 1. In which countries do right-wing populist media repertoires show a relatively high degree of source insularity (in absolute terms and in relation to the country average)?

Political and Media System as Contextual Factors

There are cues that the insularity of right-wing populist media repertoires depends on certain contextual factors, which in turn derive from a country’s media and political system. From a media system perspective, Mancini (Citation2012) observes a strategic appropriation of media channels – “media instrumentalization” – especially in Southern Europe and Latin America: “In these countries, political parallelism and media instrumentalization coexist because there is a strong tradition of partisanship that over time has been transformed into weaker political parallelism” (276). Biorcio (Citation2003) observes that the close bond between traditional parties and mainstream media in Italy has led populist parties such as the Lega Nord to establish their own forms of communication. Here, parallelism leads to a formation of partisan media. Accordingly, we formulate the following:

Hypothesis 1. The more pronounced the political parallelism, the higher the (relative) source insularity of a country’s right-wing populist parties.

Another factor might be the degree of polarization in a society, which determines the potential success of a political style of “strategic extremism” (Glaeser, Ponzetto, and Shapiro Citation2005). Extremism is a rational choice when extreme communication allows politicians to mobilize more supporters on the fringes than they scare off “median-voters” (Downs Citation1957). Lewandowsky et al. (Citation2020) stress that partisan media provide an opportunity for this kind of “pragmatic extremism” (57). Accordingly, we can formulate the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 2. The higher the degree of polarization in a country, the higher the (relative) source insularity of a country’s right-wing populist parties.

Heft et al. (Citation2020) further indicate that general trust in the media “might influence the demand and thus prospects of alternative online news providers on the right” (25). As Holt (Citation2020) points out, right-wing populist alternative media are to be understood as a phenomenon “that signifies a reaction to something that is perceived to be wrong” (204). It is therefore only logical that distrust of mainstream media increases the demand for ‘alternatives’. Furthermore, it is plausible to assume that the social capital gained by approaching mainstream media is lower in countries with a low level of media trust and thus plays a lesser role in populist strategies. We thus conclude:

Hypothesis 3. The weaker the population’s trust in media, the higher the (relative) source insularity of a country’s right-wing populist parties.

And finally, on the level of specific parties, the communication strategies may differ depending on their position within the political system. Populist parties are characterized by varying degrees of marginalization or integration within their respective political system (for a thorough discussion, see Zulianello Citation2020). Though the claim to be ‘anti-establishment’ is at the core of populist ideology, populist parties may, at times, become part of a coalition government or even the governing party. This level of political integration will impact their relationship to the media: A populist party will be excluded from mainstream reporting “if its electoral strength and standing in the polls is low and if the other parties jointly install something like a cordon sanitaire (formally or informally) to exclude a populist party from power” (Esser, Stępińska, and David Nicolas Citation2017, 366). In fact, Bos and Brants (Citation2014) showed that in the Netherlands, a country with a relatively young populist party, even the tabloid de Telegraaf is not particularly populistic, which might indicate that the media mainstream is distancing itself from populism. Similarly, in Germany we can observe that the media clearly distance themselves from the relatively young right-wing party Alternative for Germany (AfD) (Fawzi, Obermaier, and Reinemann Citation2017). In turn, Heft et al. (Citation2020, 25) deduce that marginalization in the public debate might help niche alternative media prosper. Based on these insights, we conclude:

Hypothesis 4. Nonintegrated right-wing populist parties display a higher (relative) source insularity than integrated right-wing populist parties.

Topic versus Source Insularity

Once a party attains a certain level of success, media coverage increases, particularly if the success at the polls leads to a participation in government. Esser, Stępińska, and David Nicolas (Citation2017, 366) point out that this pattern also supports the assumptions of the life cycle model by Mazzoleni et al. (Citation2003), which predicts different levels of media support during the various phases of a populist party’s life cycle. In a similar manner, a populist party’s degree of marginalization may also affect their use of topics. For example, Udris (Citation2012) was able to show that in Switzerland, the well-established populist Swiss People’s Party (SVP) receives more attention than any other party in the six examined newspapers. The SVP was able to gain visibility not only with core right-wing populist issues (e.g., identity politics, law and order) but also by penetrating issues typically owned by other parties. There is thus some indication that the marginalization of populist parties within a political and media system is also expressed in their (narrow) choice of topics, i.e., their topic insularity.

However, there is no research yet on the relationship between a party’s media insularity and its topic agenda: In traditional public spheres, a demarcation from the general discourse, an emergence of a counter-public with a specific agenda and topic priorities may have been very closely linked to the use of alternative media – polarized or fragmented media used to be a strong indicator for an equally sharply demarcated topic setting (Vliegenthart and Mena Montes Citation2014).

The conditions of a high-choice media environment and the unbundling of media content, particularly on social media, mean that we can no longer look at sources and draw conclusions on the content. Extreme agendas can also be curated from a repertoire of mainstream media. Hatakka (Citation2018), for example, shows that populist actors use social media opportunities for the “remediation and ideological reconfiguring of news content” (245).

It is thus our aim to analytically distinguish these two phenomena, exploring how the relative insularity of media use is related to the relative diversity of the populist topic agenda. Of particular interest here is the question whether mainstream media use is also accompanied by a mainstream agenda. We thus ask:

Research Question 2. What is the relationship between populist parties’ relative source insularity and relative topic insularity?

Method

Case Selection and Contextual Factors

To analyse the impact of political and media systems, we collected data from seven EU countries and Switzerland. The selection includes representatives of two types of media system according to Hallin and Mancini (Citation2004): the Mediterranean or Polarized Pluralist Model, featuring countries such as France, Italy and Spain and the North/Central Europe or Democratic Corporatist Models, such as Austria, Denmark, Germany, the Netherlands, and Switzerland.

Within our analysis, however, we will focus on the impact of specific characteristics of these countries as independent variables, nominally political parallelism, political polarization, and general media trust on the country level, as well as marginalization on the party level.

The data on parallelism stems from Brüggemann et al. (Citation2014). The degree of polarization in a given country is based on data from the Varieties of Democracies (VDem) Project (Coppedge et al. Citation2019) for which experts assess the polarization of public opinion on major political issues (variable v2smpolsoc/2019). Data on general media trust was taken from the Digital News Report (Newman et al. Citation2020), an annual representative survey in 37 countries. Within each of the eight countries, we selected the largest right-wing party in terms of parliamentary seats (based on Rooduijn et al. Citation2019, see ): the Freedom Party of Austria (FPÖ), the Swiss People's Party (SVP), the Alternative for Germany (AfD), the Danish People's Party (DF), VOX from Spain, the French National Rally (RN), the Northern League (LN) from Italy, and the Party for Freedom (PVV) from the Netherlands. Based on the concept of integration according to Zulianello (Citation2020), all right-wing populist parties considered here are either nonintegrated (not actively cooperating with mainstream parties) or negatively integrated (actively cooperating with mainstream parties, for example as part of a government coalition, but also continuously challenging the values and institutions of the liberal-democratic regime).

Table 1. Explanatory factors per country.

Measuring Linking Practices

For our dependent variables, we collected the tweets for delegates of all parties in each parliament (we precluded small parties, i.e., parties with a share < 1% of seats, as well as parties with a very low number of tweets). For this purpose, we created a list that assigns an account to each parliamentarian who is active on Twitter. Tweets by 2,229 parliamentarians were downloaded in August 2020 using rtweet (Kearney Citation2019). We downloaded all tweets of a given account that are available via Twitter’s API (max. 3,200), which yielded a data set of 4,368,030 tweets that can be assigned to 141 parties. The percentage of parliamentarians active on Twitter varies from country to country (Austria: 45%, Switzerland: 74%, Germany: 75%, Denmark: 92%, Spain: 90%, France: 95%, Italy: 78%, the Netherlands: 96%).

For the right-wing parties (see case selection), we constructed their media repertoires based on the links used within the tweets. Our research ties in with various studies that analyse media repertoires based on social media platforms (Schmidt Citation2016; Eady et al. Citation2019). Rauchfleisch, Vogler, and Eisenegger (Citation2020) also “utilize the sharing of URLs of news media articles on Twitter as a proxy for corresponding news media usage” (4), aggregating individual media consumption to compare the specific repertoires of domestic and foreign communities. Analytically, we group links according to the domains of their URLs (e.g., the link www.example.com/path/ is reduced to the domain ‘example.com’) – we call this part of the link the source.

Source Insularity

We start with a table of the absolute numbers of links from party X to source Y (for each country). These absolute values were first standardized by party, then by medium, with values across all parties per medium adding up to 1. To make the countries comparable, these resulting values were centred around the value 0.5, i.e., values of less than 1/(number of parties) were stretched to [0, 0.5], and values ≥ 1/(number of parties) were compressed to [0.5, 1]. For each party, this adjusted table results in a vector with a length of N = number of media in the given country. This vector thus specifies for each medium how insular, i.e., how exclusively it is being used by that party.

In turn, the source insularity specifies for each party how much a party focuses only on a few sources in its linking practices. It was calculated as Gini coefficients on these parties’ vectors. The Gini coefficient is a statistical measure to represent unequal distributions, assuming values in the range [0,1] – the (absolute) source insularity is thus the measure of an uneven distribution of links across associated sources. When a party uses (i.e., links to) all sources in one country evenly, the Gini is 0. If it uses only one source, it is 1. In addition, we also calculated relative source insularity by comparing a party’s source insularity from the average source insularity of all political parties in that country.

Topic Insularity

To calculate topic insularity, we scraped the articles to which the tweets link as the tweets themselves do not allow us to fully reconstruct the underlying topics. The scraping process required us to reduce corpus size. We only considered tweets that were retweeted or liked at least 10 times cumulatively (362,269 tweets with 258,688 links). We did not consider links to Twitter, Instagram, and YouTube, since we did not expect to find pertinent texts there. We scraped the expanded short URLs using the packages RCurl (Temple Lang Citation2020) and RJSONIO (Temple Lang and Wallace Citation2020) as well as the Scraper Diffbot (Citation2020). The service’s API yields a structured text file that identifies the article, its title, date, and author. Overall, we were able to download 67% of the links accessed via Diffbot (N = 172,638 texts) successfully (the scraper failed mainly due to multimedia content).

In a next step, we removed all texts from the corpus that were written in languages other than the dominant language of the texts from a given country (in Switzerland, for example, we only left German texts) to avoid distortions in our subsequent topic measurement. We cleaned up the remaining texts by removing upper and lower case, punctuation, numbers, and individual stop words for each country, and then tokenized (for further pre-processing, see the script in the appendix). Texts were also randomly shortened (to a maximum of 500 words) to ensure that very long texts would not bias the topic model.

The topic clustering method LDA was then applied to this data. Topic modeling methods such as LDA (cf. Blei, Ng, and Jordan Citation2003; Maier et al. Citation2018) make it possible to visualize latent topic connections in large text corpora. LDA models these relationships as topics, as probability distributions over all words. Each document in the corpus can also be represented as a probability distribution (via the topics). The model assigns a topic to each token (each word in each text), so that each text can be represented as a topic mix.

To calculate the LDA models, we used the method LDA-Prototype (Rieger et al. Citation2020), implemented in the R-package ldaPrototype (Rieger Citation2020). Several LDA models are calculated using the same variable settings. Then the model whose topics bear the greatest similarity to the topics of all other models is selected. The LDA prototype is thus the model with the highest similarity value over all pairings, which ensures that the model is not an extreme or unstable expression of a certain constellation of variables (Rieger, Rahnenführer, and Jentsch Citation2020). The parameters for the LDA were varied for each country via K ∈ {20, 25, … 75}, resulting in 12 prototypes. The LDA results were thus stabilized at two levels: First, the prototype method minimized fluctuations of the probabilistic method; second, it ensured that inferences regarding topic insularity would not depend on a certain constellation of variables – the LDA values used in the analysis are the average of 12 prototypes.

As we did for source insularity, we started our calculation of topic insularity with a table showing the absolute assignments of party X to topic Y per text (again, one table for each country). This table was first standardized for each text to ensure every text has the same influence. These relative topic assignments were grouped and totalled per text and political party, resulting in a table of cumulated relative topic assignments per party. We used this table the same way as we did for source insularity: first standardization per party, then per topic, resulting in a table where the sum of all topic assignments per party is 1. To make countries comparable, these values were also centred around the value 0.5, i.e., values of less than 1/(number of parties) were stretched to [0, 0.5], values ≥ 1/(number of parties) were compressed to [0.5, 1].

Findings

RQ1. In which countries do populist media repertoires show a high degree of source insularity (in absolute terms and in relation to the country average)?

Absolute Source Insularity

Considering the absolute source insularity of the right-wing populist parties in our study, we can distinguish three types (see ):

Table 2. Sources and topic insularity per party.

1. Very high degree of source insularity (>0.7)

Within the sample of right-wing parties, there is a single party with a very high degree of source insularity, the French National Rally (formerly Front National). The special role of this party seems to be related to its importance in French regional councils. The parliamentarians of National Rally link to many local media which they use almost exclusively, e.g., madeinperpignan.com, a site from the French city of Perpignan – which, alongside Toulon, is one of two major French cities with an extreme right-wing mayor.

2. Moderate degree of source insularity (<0.7, >0.5)

The right-wing populist parties with a moderate degree of source insularity are Italy's Northern League, Spain's VOX, Alternative for Germany and Party for Freedom from the Netherlands. This is due to their linkages to various alternative media not commonly linked to by the more mainstream parties: MPs from the Northern League link to partisan media, such as the far-right website ilpopulista.it, which is financed by LN-affiliated companies according to Newsguard (Paura Citation2020). Also, LN parliamentarians are the only ones to frequently share contents of the Sindacato Autonomo di Polizia (sap-nazionale.org) – a news site closely associated with the Italian state police. A similar pattern can be observed in Spain: VOX uses alternative media in an insular fashion, e.g., rebelionenlagranja.com, actuall.com, or outono.net.

In Germany, in addition to the party’s own website afd.de and blogs by right-wing politicians Boehriger and Münzenmaier, AfD parliamentarians are the only ones who link to right-wing media such as jungefreiheit.de, journalistenwatch.com, philosophia-perennis.com and pi-news.net. Interestingly, links exclusively shared by the Dutch Party for Freedom MPs point to international right-wing media such as breitbart.com, voiceofeurope.com, or jihadwatch.org.

3. Low degree of insularity (<0.5)

In the remaining countries from the Northern European or Democratic Corporatist countries (Switzerland, Denmark and Austria), right-wing populist parties tend to exhibit a more varied and less exclusive use of sources, though in each country some sources stand out. In Denmark, politicians of the Danish People's Party link rather exclusively to moderate partisan media (e.g., denkorteavis.dk and ditoverblik.dk), in Austria, the Freedom Party is rather exclusive in its links to right-wing blogs such as erstaunlich.at, thedailyfranz.at, and unzensuriert.at, as well as to its own party website and a blog by party member Schnedlitz. In contrast, the Swiss People's Party’s insularly used sources (in addition to proprietary party channels and politicians’ blogs) tend to stem from the (often German) right-wing conservative or libertarian milieu (schweizerzeit.ch, tichyseinblick.de, deutsche-wirtschafts-nachrichten.de etc.) rather than the openly radical right wing.

Data on the populist parties’ source insularity suggest a clear correlation with polarization (r = −0.71), general media trust (r = −0.71) and political parallelism (r = 0.52): The more polarized the country and the more pronounced the political parallelism, the more insular is the media use of its right-wing populist parties, the more citizens trust their media in general, the more right-wing populist parties link to mainstream media (H1, H2 and H3 confirmed).

H4 cannot/only partially be confirmed: The Northern League and VOX, as integrated parties, have a higher degree of source insularity than the nonintegrated right-wing populist parties from Holland the Netherlands and Germany. H4 can be confirmed, however, if we consider only the group of countries with strong media trust (countries that can be assigned to the North/Central Europe or Democratic Corporatist Model). In this group, AfD and PVV, as nonintegrated right-wing populist parties, have the highest degree of source insularity.

Relative Source Insularity

To understand a populist relative source insularity in relation to mean insularity, we must first look at the overall situation in the given country. Here, we see a gradation that corresponds to the categories proposed by Hallin and Mancini (Citation2004) and Brüggemann et al. (Citation2014): Countries with a low mean source insularity, i.e., countries where parties are less inclined to communicate via exclusive partisan channels, fall under the North/Central Europe or Democratic Corporatist Model (in order of increasing insularity: Austria, Denmark, the Netherlands, Switzerland, Germany). By contrast, countries that belong to the Mediterranean or Polarized Pluralist Model (Italy, France and Spain) show a higher mean source insularity.

Accordingly, a country’s mean source insularity correlates strongly with the underlying categories of the comparative model: The higher the degree of polarization (r = −0.81) and the more pronounced parallelism (r = 0.61), the higher the mean source insularity. The data also suggests a clear linear correlation between general media trust and source insularity (r = −0.58). We can thus conclude that the higher the level of trust, the lower the polarization, and the weaker the parallelism in a country, the more diverse are the sources used by political parties and the more the parties’ use of sources overlaps. In polarized countries with strong parallelism and low media trust, the parties, as a whole, tend to use sources in a more insular fashion. Finally, we consider the relationship of populist parties’ source insularity in relation to the average of the respective country (this relationship is illustrated by the vertical axis in ). We can generally distinguish four possible groups:

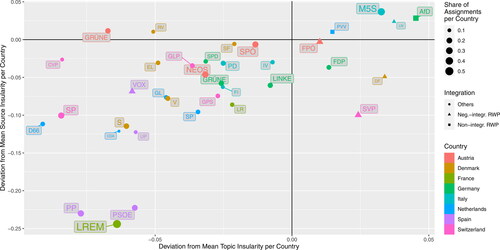

Figure 1. Relation of topic and source insularity for all parties and deviations from the mean value of all parties per country. (Negative) integrated right-wing populist parties (Neg.-integr. RWP) are shown as a triangle, non-right-wing parties (non-integr. RWP) as a rectangle – all other parties as a circle. For the sake of clarity only those parties are shown that received more than 9.5% of the assignments in the respective country. Assignments denote all tokens in articles considered in the LDA. The parties are coloured according to their country and sized according to their share of assignments in that country. For a list of all party abbreviations, see the appendix.

1. Adapted to a generally low level of source insularity

First, there are parties with below-average source insularity (below the x-axis in ) in countries with generally low mean source insularity – these include the Swiss SVP, the Danish PP and the Austrian FPÖ. These right-wing populist parties are adapting to the generally diverse, mainstream-oriented media use in their countries.

2. Adapted to a generally high degree of source insularity

Then we have parties with above-average source insularity (above the x-axis in ) from countries with relatively high mean source insularity – these include the right-wing populist parties from Italy and France. These parties aim to distinguish themselves by their use of sources – a practice common for all parties in their respective political systems, though to a lesser degree than for right-wing populist parties.

3. Conspicuous by its high degree of source insularity

The parties in the third category feature above-average source insularity in countries with a low mean source insularity, including the Dutch Party for Freedom and the Alternative for Germany. These parties clearly distinguish themselves through their linking practices, however, this practice is quite unusual for their respective countries – the other parties’ media use is rather evenly distributed in Germany and the Netherlands.

4. Conspicuous by its low degree of source insularity

Finally Spain is a special case: Here the right-wing populist party’s source insularity is lower than the generally high mean source insularity of the country which in the case of Spain is due to its large number of small regional parties, each of which caters to a very specific target group and uses specialized media for this purpose.

Looking at all parties, we can only confirm H3 (H1 and H2 not confirmed) where the data suggests a clear correlation (r = −0.53): The higher the media trust, the lower the relative source insularity of the right-wing populist parties. In analogy to absolute source insularity, H4 must also be considered in a differentiated way: Among the group of countries that fall under the North/Central Europe or Democratic Corporatist Model, only the nonintegrated right-wing populist parties feature above-average source insularity. H4 can therefore be confirmed for this group, but not for the remaining countries.

RQ2 What is the relationship between populist parties’ relative source insularity and relative topic insularity?

The populist parties in all countries feature higher topic insularity than the national average (Spain being an exception for the above-mentioned reasons). The concentration on a few core issues is thus apparently a fixed characteristic of right-wing populist parties. Only very small, regionally specialized parties surpass the populists – in in the fields to the right of the vertical zero axis (with the exception of the German FDP, which has a clear economic focus, see von Nordheim and Rieger Citation2020).

It is important to note that the data on source and topic insularity does not suggest a correlation between the two variables. Thus, we cannot make assumptions about topic insularity based on source insularity. Even right-wing populist parties with low levels of source insularity (in the lower right hand field of ), i.e., with a comparatively broad media repertoire, focus their agenda on right-wing populist core issues. This becomes clear when we look at topics that show high insularity in the populist agenda (we are considering the results of the LDA with K = 30) – typical core topics are, in particular: refugees/foreigners/Islam and crime.

Discussion

The insular use of sources on social media is part of a dynamic in which populist actors position themselves with regard to the general societal discourse and the mainstream on the one hand, and their followers and their claim of ‘alternativeness’ on the other. Various contextual factors determine the dominating forces in this dynamic, from the characteristics of the media and political system to the country’s current political situation, to the status of populist actors and their position in the public discourse. These factors determine whether politicians from right-wing populist parties tend to share exclusive sources with their supporters or sources that are also linked to by politicians from other parties. Both tendencies are reflected in populist parties’ media repertoire, or more precisely: in the degree of source insularity.

Based on our analysis, we can first state that our sample does not allow for a general statement on the source insularity of right-wing populist parties – rather, a high (or low) degree of source insularity does not seem to be a cross-national feature of right-wing populist parties’ linking practices. Our comparative approach did allow us, however, to attribute the varying degrees of insularity of right-wing populist parties’ media repertoires to contextual factors:

Our data suggests a correlation between general media trust and source insularity. In countries with high levels of media trust, the right-wing populist media repertoire has a comparatively low degree of insularity (e.g., in DK, CH, and AT). This supports the assumption that trust in media correlates negatively with the demand for and prospects of partisan sources (Heft et al. Citation2020). This relationship also holds true for relative source insularity: The higher the media trust, the less populist parties’ source insularity diverges from the average within each country.

At the same time, there seems to be a lesser inclination towards insular media use in less polarized societies. One reason for this could be that “pragmatic extremism” (Lewandowsky et al. Citation2020, 57) – a mobilization of the margins of society – is relatively ineffective in such countries. This is especially true in countries where the right-wing populist party is comparatively integrated in the political and media system, even it continues to challenge the values of the liberal-democratic regime (cf. Zulianello Citation2020). However, if the right-wing populist party is not integrated, their use of sources is comparatively insular, even in countries with low polarization and high media trust (e.g., in DE, NL).

Regardless of the degree of insularity, synergistic and even exclusive links between various forms of alternative media and right-wing populist actors could be identified in each country. Accordingly, even right-wing populist parties with otherwise low source insularity are part of nationally and internationally ramified alternative media ecosystems (Starbird Citation2017; Heft et al. Citation2021; Kaiser, Rauchfleisch, and Bourassa Citation2020).

In a second step, we explored to which extent we can derive conclusions about right-wing populist parties’ digital topic agendas from their media use. This additional content-level analysis allows us to determine whether the relatively mainstream, normalized source use by right-wing populist parties which we observed in various countries is also reflective of a similarly normalized political agenda. This does not appear to be the case. Regardless of their degree of source insularity, right-wing populist parties in all countries (except Spain) exhibit a relatively high degree of topic insularity. A narrow, non-diverse agenda seems to be a characteristic of right-wing populist communication independent of national contexts – as is their focus on certain core issues particularly prominent with right-wing populist parties, especially the ‘othering’ of foreigners and reporting on crime. While the results at the source level do not paint a clear picture, the topic analysis thus confirms the picture of asymmetrical isolation, of a network whose fringes form bubbles of extreme ideologies (Möller Citation2021).

The lack of correlation between source and topic insularity suggests that source selection and agenda setting, especially in digital publics, are two separate practices that should also be considered separately. Similar to studies on the relevance of filter bubbles, we found that cluster effects appear much smaller at the source level than at the content level (Bechmann and Nielbo 2018). This insight has clear implications for studies that seek to infer the quality of media repertoires (such as diversity, polarization, or fragmentation) or discourses from the use of specific sources – without an accompanying consideration of the content level, such inferences could end up painting a distorted picture.

Our method of reconstructing repertoires via the linking practices of right-wing populist MPs on Twitter has proven effective. We must point out, however, that especially in the case of strategic gatekeepers, it might be misleading to derive source repertoires (i.e., the sources that are actually used) from linking behaviours. The repertoire approach we applied measures the published source repertoire and is therefore not necessarily identical with the definition of ‘repertoire’ used in other studies. In our study, we focus more on the level of meta-communication, i.e., source choices and recommendations made in the public eye, and less on the actor’s ‘private’ media repertoire.

Furthermore, the repertoire concept we used here is broadly defined as a source rather than a media repertoire. This broad operationalization has the advantage of allowing us to consider different channels of partisan source use together, such as communication via the actor’s own Facebook pages, publications on politicians’ blogs, as well as content published on affiliated alternative media. The transition between these formats is rather fluid. The metric of insularity creates comparability. Future studies could follow up with a descriptive categorization of the sources used. Among the sources used in insular fashion, a closer look at the alternative media reveals interesting variations: Right-wing populist parties whose source repertoire resembles that of other parties in their country apparently also prefer alternative media more akin to traditional journalistic media. In countries with high polarization or rather marginalized right-wing populist parties, insular source use includes alternative media that clearly differ from traditional journalism.

Small or regionally specialized parties turned out to be a particular challenge for our comparative analysis. This factor has, for example, affected the comparability of Spain whose high mean source insularity is caused mainly by the regional parties in parliament. Here, too, it is therefore necessary to consider the content level to distinguish regional or thematic source insularity from the type of insularity which seems to be associated with populist communication in some countries. In future comparative studies, parties should therefore be categorized according to their thematic and regional focus to improve comparability.

The presented results are limited in three respects, in particular: They are limited to the platform Twitter, which is important for elite communication, but only of limited relevance for communication between politicians and voters. Politicians reach a larger target group on other platforms, especially Facebook. We should therefore examine whether the results of this study can be confirmed in a cross-platform comparison. In addition, the analysis is limited to the texts the scraper was able to access – the analysis neither included multimedia nor Facebook contents. In a next step, it would therefore be useful to supplement the corpus with social media posts and transcribed video and audio content. Third, the decision to reduce the corpus to texts in one language per country might have led to distortions – future studies may want to include automated translations of different-language texts.

rdij_a_1970602_sm8838.rar

Download (14.7 KB)rdij_a_1970602_sm8815.csv

Download Comma-Separated Values File (2.8 KB)Disclosure Statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- Aalberg, T., Esser, F., Reinemann, C., Strömbäck, J., & Vreese, C. d., eds. 2017. Populist Political Communication in Europe. New York, NY: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group.

- Adamic, L. A. 2008. “The Social Hyperlink.” In The Hyperlinked Society, edited by J. Turow and L. Tsui, 227–249. University of Michigan Press; JSTOR.

- Bachl, M. 2018. “(Alternative) Media Sources in AfD-Centered Facebook Discussions.” SCM Studies in Communication and Media 7 (2): 256–270.

- Barberá, P., J. T. Jost, J. Nagler, J. A. Tucker, and R. Bonneau. 2015. “Tweeting from Left to Right: Is Online Political Communication More than an Echo Chamber?” Psychological Science 26 (10): 1531–1542.

- Bechmann, A., and K. L. Nielbo. 2018. “Are We Exposed to the Same “News” in the News Feed?: An Empirical Analysis of Filter Bubbles as Information Similarity for Danish Facebook Users.” Digital Journalism 6 (8): 990–1002.

- Benkler, Y. 2006. The Wealth of Networks: How Social Production Transforms Markets and Freedom. New Haven, Connecticut: Yale University Press.

- Benkler, Y., R. Faris, and H. Roberts. 2018. Network Propaganda: Manipulation, Disinformation, and Radicalization in American Politics. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

- Biorcio, R. 2003. “The Lega Nord and the Italian Media System.” In The Media and Neo-Populism: A Contemporary Comparative Analysis, edited by G. Mazzoleni, J. Stewart, and B. Horsfield, 71–94. Westport, CT: Praeger.

- Blei, D. M., A. Y. Ng, and M. I. Jordan. 2003. “Latent Dirichlet Allocation.” Journal of Machine Learning Research 3: 993–1022.

- Bos, L., and K. Brants. 2014. “Populist Rhetoric in Politics and Media: A Longitudinal Study of The Netherlands.” European Journal of Communication 29 (6): 703–719.

- Brüggemann, M., S. Engesser, F. Büchel, E. Humprecht, and L. Castro. 2014. “Hallin and Mancini Revisited: Four Empirical Types of Western Media Systems.” Journal of Communication 64 (6): 1037–1065.

- Coppedge, M., J. Gerring, C. H. Knutsen, J. Krusell, J. Medzihorsky, J. Pernes, S.-E. Skaaning, et al. 2019. “The Methodology of “Varieties of Democracy” (V-Dem)1.” Bulletin of Sociological Methodology/Bulletin de Méthodologie Sociologique 143 (1): 107–133.

- De Maeyer, J. 2013. “Towards a Hyperlinked Society: A Critical Review of Link Studies.” New Media & Society 15 (5): 737–751.

- Diffbot. 2020. Mission. https://www.diffbot.com/company/

- Dittrich, P.-J. 2017. Social Networks and Populism in the EU. Four Things you should know (No. 192; Policy Paper). Jacques Delors Institut. https://www.delorsinstitut.de/2015/wp-content/uploads/2017/04/20170419_SocialNetworksandPopulism-Dittrich.pdf

- Downs, A. 1957. An Economic Theory of Democracy. New York, NY: Harper & Row.

- Dvir-Gvirsman, S. 2017. “Media Audience Homophily: Partisan Websites, Audience Identity and Polarization Processes.” New Media & Society 19 (7): 1072–1091.

- Eady, G., J. Nagler, A. Guess, J. Zilinsky, and J. A. Tucker. 2019. “How Many People Live in Political Bubbles on Social Media? Evidence from Linked Survey and Twitter Data.” SAGE Open 9 (1): 1–21.

- Ernst, N., S. Blassnig, S. Engesser, F. Büchel, and F. Esser. 2019. “Populists Prefer Social Media over Talk Shows: An Analysis of Populist Messages and Stylistic Elements across Six Countries.” Social Media + Society 5 (1).

- Esser, F., A. Stępińska, and H. David Nicolas. 2017. “Populism and the Media. Cross-National Findings and Perspectives.” In Populist Political Communication in Europe, edited by T. Aalberg, F. Esser, C. Reinemann, J. Strömbäck, and C. H. de Vreese, 365–380. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Fawzi, N., M. Obermaier, and C. Reinemann. 2017. “Germany: Is the Populism Laggard Catching up?” In Populist Political Communication in Europe, edited by T. Aalberg, F. Esser, C. Reinemann, J. Strömbäck, and C. H. de Vreese, 111–126. New York, NY: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315623016

- Giglietto, F., A. Valeriani, N. Righetti, and G. Marino. 2019. “Diverging Patterns of Interaction around News on Social Media: Insularity and Partisanship during the 2018 Italian Election Campaign.” Information, Communication & Society 22 (11): 1610–1629.

- Glaeser, E. L., G. Ponzetto, and J. Shapiro. 2005. “Strategic Extremism: Why Republicans and Democrats Divide on Religious Values.” The Quarterly Journal of Economics 120 (4): 1283–1330.

- Haller, A. 2020. “Populist Online Communication.” In Perspectives on Populism and the Media: Avenues for Research, edited by B. Krämer and C. Holtz-Bacha, 1st ed., 161–180. Baden-Baden: Nomos Verlagsgesellschaft mbH & Co. KG.

- Haller, A., and K. Holt. 2019. “Paradoxical Populism: How PEGIDA Relates to Mainstream and Alternative Media.” Information, Communication & Society 22 (12): 1665–1616.

- Hallin, D. C., and P. Mancini. 2004. Comparing Media Systems. Three Models of Media and Politics. Communication, Society and Politics. Cambridge: Cambridge University.

- Hasebrink, U., and J. Popp. 2006. “Media Repertoires as a Result of Selective Media Use. A Conceptual Approach to the Analysis of Patterns of Exposure.” Communications 31 (3): 369–387.

- Hatakka, N. 2018. “Facebook and the Populist Right. How Populist Politicians Use Social Media to Reimagine the News in Finland and the UK.” In The Media and Austerity: Comparative Perspectives, edited by L. Basu, S. Schifferes, and S. Knowles, 237–247. London: Routledge.

- Heft, A., E. Mayerhöffer, S. Reinhardt, and C. Knüpfer. 2020. “Beyond Breitbart: Comparing Right‐Wing Digital News Infrastructures in Six Western Democracies.” Policy & Internet 12 (1): 20–45.

- Heft, A., C. Knüpfer, S. Reinhardt, and E. Mayerhöffer. 2021. “Toward a Transnational Information Ecology on the Right? Hyperlink Networking among Right-Wing Digital News Sites in Europe and the United States.” The International Journal of Press/Politics 26 (2): 484–504.

- Holt, K. 2020. “Populism and Alternative Media.” In Perspectives on Populism and the Media: Avenues for Research, edited by B. Krämer and C. Holtz-Bacha, 1st ed., 201–214. Baden-Baden: Nomos Verlagsgesellschaft mbH & Co. KG.

- Holt, K., T. U. Figenschou, and L. Frischlich. 2019. “Key Dimensions of Alternative News Media.” Digital Journalism 7 (7): 860–869.

- Ihm, J., and E. Kim. 2018. “The Hidden Side of News Diffusion: Understanding Online News Sharing as an Interpersonal Behavior.” New Media & Society 20 (11): 4346–4365.

- Kaiser, J., A. Rauchfleisch, and N. Bourassa. 2020. “Connecting the (Far-)Right Dots: A Topic Modeling and Hyperlink Analysis of (Far-)Right Media Coverage during the US Elections 2016.” Digital Journalism 8 (3): 422–441.

- Kearney, M. W. 2019. rtweet: Collecting Twitter Data (0.6.9). https://cran.r-project.org/package=rtweet

- Krämer, B. 2017. “Populist Online Practices: The Function of the Internet in Right-Wing Populism.” Information, Communication & Society 20 (9): 1293–1309.

- Lewandowsky, S., L. Smillie, D. Garcia, R. Hertwig, J. Weatherall, S. Egidy, R. E. Robertson, et al. 2020. Technology and Democracy: Understanding the Influence of Online Technologies on Political Behaviour and Decision Making. Publications Office. https://data.europa.eu/doi/102760/709177

- Maier, D., A. Waldherr, P. Miltner, G. Wiedemann, A. Niekler, A. Keinert, B. Pfetsch, et al. 2018. “Applying LDA Topic Modeling in Communication Research: Toward a Valid and Reliable Methodology.” Communication Methods and Measures 12 (2–3): 93–118.

- Mancini, P. 2012. “Instrumentalization of the Media vs. Political Parallelism.” Chinese Journal of Communication 5 (3): 262–280.

- Mazzoleni, G. 2008. “Populism and the Media.” In Twenty-First Century Populism: The Spectre of Western European Democracy, edited by D. Albertazzi and D. McDonnell, 49–64. Palgrave Macmillan UK.

- Mazzoleni, G., Stewart, J., & Horsfield, B., eds. 2003. The Media and Neo-Populism: A Contemporary Comparative Analysis. Westport, Connecticut: Praeger.

- Möller, J. 2021. “Filter Bubbles and Digital Echo-Chambers.” In The Routledge Companion to Media Misrepresentation and Populism, edited by H. Tumber and S. Waisbord, 92–100. London: Routledge.

- Mudde, C. 2004. “The Populist Zeitgeist.” Government and Opposition 39 (4): 541–563.

- Müller, P., and A. Schulz. 2021. “Alternative Media for a Populist Audience? Exploring Political and Media Use Predictors of Exposure to Breitbart, Sputnik, and Co.” Information, Communication & Society 24 (2): 277–217.

- Newman, N., R. Fletcher, A. Kalogeropoulos, D. Levy, and R. Kleis Nielsen. 2018. Reuters Institute Digital News Report 2018. https://www.reutersagency.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/digital-news-report-2018.pdf

- Newman, N., R. Fletcher, A. Schulz, S. Andı, and R. K. Nielsen. 2020. Reuters Institute Digital News Report 2020. Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism. https://reutersinstitute.politics.ox.ac.uk/sites/default/files/2020-06/DNR_2020_FINAL.pdf

- Nygaard, S. 2019. “The Appearance of Objectivity: How Immigration-Critical Alternative Media Report the News.” Journalism Practice 13 (10): 1147–1163.

- O’Callaghan, D., D. Greene, M. Conway, J. Carthy, and P. Cunningham. 2013. “An Analysis of Interactions within and between Extreme Right Communities in Social Media.” In Ubiquitous Social Media Analysis, edited by M. Atzmueller, A. Chin, D. Helic, and A. Hotho, Vol. 8329, 88–107. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer.

- Park, H. W., and M. Thelwall. 2008. “Developing Network Indicators for Ideological Landscapes from the Political Blogosphere in South Korea.” Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication 13 (4): 856–879.

- Paura, A. 2020. ilpopulista.it. A Website Controlled by the Far-Right Party The League that Has Published False and Unsubstantiated Claims. Newsguard Nutrition Label. https://www.newsguardtech.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/IlPopulista.it-with-boxes.pdf

- Rae, M. 2021. “Hyperpartisan News: Rethinking the Media for Populist Politics.” New Media & Society 23 (5): 1117–1132.

- Rauchfleisch, A., D. Vogler, and M. Eisenegger. 2020. “Transnational News Sharing on Social Media: Measuring and Analysing Twitter News Media Repertoires of Domestic and Foreign Audience Communities.” Digital Journalism 8 (9): 1206–1225.

- Rieger, J. 2020. “ldaPrototype: A Method in R to Get a Prototype of Multiple Latent Dirichlet Allocations.” Journal of Open Source Software 5 (51): 2181.

- Rieger, J., L. Koppers, C. Jentsch, and J. Rahnenführer. 2020. Improving Reliability of Latent Dirichlet Allocation by Assessing Its Stability Using Clustering Techniques on Replicated Runs. ArXiv:2003.04980 [Cs, Stat]. http://arxiv.org/abs/2003.04980

- Rieger, J., J. Rahnenführer, and C. Jentsch. 2020. “Improving Latent Dirichlet Allocation: On Reliability of the Novel Method LDAPrototype.” In Natural Language Processing and Information Systems, edited by E. Métais, F. Meziane, H. Horacek, and P. Cimiano, 118–125. Cham: Springer International Publishing.

- Rooduijn, M., S. van Kessel, C. Froio, A. Pirro, S. De Lange, D. Halikiopoulou, P. Lewis, C. Mudde, and P. Taggart. 2019. The PopuList: An Overview of Populist, Far Right, Far Left and Eurosceptic Parties in Europe. https://popu-list.org

- Schmidt, J.-H. 2016. “Twitter Friend Repertoires: Introducing a Methodology to Assess Patterns of Information Management on Twitter.” First Monday 21 (4). https://firstmonday.org/ojs/index.php/fm/article/view/6207.

- Singer, J. B. 2014. “User-Generated Visibility: Secondary Gatekeeping in a Shared Media Space.” New Media & Society 16 (1): 55–73.

- Slater, M. D. 2007. “Reinforcing Spirals: The Mutual Influence of Media Selectivity and Media Effects and Their Impact on Individual Behavior and Social Identity.” Communication Theory 17 (3): 281–303.

- Starbird, K. 2017. “Examining the Alternative Media Ecosystem through the Production of Alternative Narratives of Mass Shooting Events on Twitter.” Proceedings of the Eleventh International AAAI Conference on Web and Social Media (ICWSM 2017), Montréal, Québec, Canada, 230–239.

- Temple Lang, D. 2020. RCurl: General Network (HTTP/FTP/…) Client Interface for R (R package version 1.98-1.2). https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=RCurl

- Temple Lang, D., and J. Wallace. 2020. RJSONIO: Serialize R Objects to JSON, JavaScript Object Notation (R package version 1.3-1.4). https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=RJSONIO

- Udris, L. 2012. Is the Populist Radical Right (Still) Shaping the News? Media Attention, Issue Ownership and Party Strategies in Switzerland (Working Paper No. 53). Switzerland: University of Zurich, NCCR Democracy. https://www.zora.uzh.ch/id/eprint/97624

- VDem Codebook. 2019. VDem. Varieties of Democracy. Codebook. V9. https://www.v-dem.net/media/filer_public/e6/d2/e6d27595-9d69-4312-b09f-63d2a0a65df2/v-dem_codebook_v9.pdf

- Vliegenthart, R., and N. Mena Montes. 2014. “How Political and Media System Characteristics Moderate Interactions between Newspapers and Parliaments: Economic Crisis Attention in Spain and The Netherlands.” The International Journal of Press/Politics 19 (3): 318–339.

- von Nordheim, G., and J. Rieger. 2020. “Im Zerrspiegel Des Populismus: Eine Computergestützte Analyse Der Verlinkungspraxis Von Bundestagsabgeordneten Auf Twitter.” Publizistik 65 (3): 403–424.

- Zulianello, M. 2020. “Varieties of Populist Parties and Party Systems in Europe: From State-of-the-Art to the Application of a Novel Classification Scheme to 66 Parties in 33 Countries.” Government and Opposition 55 (2): 327–347.