Abstract

Digital platforms, with their ever-increasing reach and power, are reshaping many aspects of society. China is experiencing a platformization of society akin to what has occurred in the West. By mapping the algorithmic news distribution field in China, this study shows how the key players (including digital platforms, news organizations, and state regulators) compete, collaborate, and work symbiotically with each other in this changing ecology. We explore a particularly key player—Jinri Toutiao, led by ByteDance (parent company of the popular app TikTok)—as a case that exemplifies the platform logic in China’s news ecosystem and how it involves a delicate dance with the public and regulators in a politically restrictive environment. We find that the mutual shaping of platforms and society is not a given but rather a dynamic process. Indeed, we show that Toutiao’s tremendous success is partially because of the state’s laissez-faire policy in the earlier years, and that its move to assume greater social responsibility is a response to recent tightening of regulations. Amid widespread questions about the role and influence of Big Tech and platforms in society, the case of China enriches our understanding of the platformization of news outside the Western context.

Introduction

Social and civic practices around the globe have been shaped in recent years by what has been characterized as the platformization of society: the widespread uptake and influence of datafication and algorithmic applications, and the dominance of digital platforms and the economic models associated with them (Van Dijck, Poell, and Waal Citation2018). Such platformization has infiltrated the news industry, with the journalistic use of algorithms widely adopted throughout the news value chain (Diakopoulos Citation2019). Because the platformization of news may favour a system powered by algorithmic processing of datafied user activities and thus potentially clash with journalistic autonomy (Bucher Citation2018; Christin Citation2020), such phenomena deserve further scholarly examination—particularly in contexts that, to date, have been relatively understudied in journalism studies.

There is a growing body of literature examining how the introduction of algorithms in newsrooms has influenced journalism. However, little research on the topic has focused on cases and consequences outside the Western platform ecosystem. Much less is known about the drivers of digital innovation uptake and its socio-political impact in a wider variety of political and cultural environments. There is a need to look beyond the Western world, especially with an eye toward the rising global platforms being developed in China, as they are operating under different economic models and societal norms when compared to most taken-for-granted liberal democratic assumptions about journalism (cf. Lin and Lewis, Citation2022). The present study offers a unique contribution by studying the platformization of news in China by mapping the algorithmic news distribution market as well as zeroing in on a particularly salient player: Jinri Toutiao, led by ByteDance, the parent company of the widely popular app TikTok. This case study serves to illustrate the growing role of platforms in China’s news ecosystem, its corresponding impacts on journalism, and the complicated dynamics playing out among news organizations, tech companies, and state institutions in a repressive media system and a politically restrictive environment.

The Rise of Platforms as Distributors of News

Building on the political economy tradition in media and communication studies, Nieborg and Poell theorized the process of the ever-increasing power of digital platform companies in cultural production as platformization, which they define as “the penetration of economic, governmental, and infrastructural extensions of digital platforms into the Web and app ecosystems, fundamentally affecting the operations of the cultural industries” (2018, 4276). The growth and ubiquity of digital platforms generally and social media platforms particularly has resulted in a media and information environment dominated by “distributed” forms of discovery (Kalogeropoulos, Fletcher, and Nielsen Citation2019), one with profound implications for how information moves and how people encounter it in light of new forms of gatekeeping (Thorson and Wells Citation2015). The growing centrality of algorithms in such distribution has added another layer of complexity.

The Spread and Influence of Algorithmic News Distribution

Recent decades have seen dramatic changes in how news is distributed and how people consume it. The struggle for news organizations to control news distribution in the face of competition from algorithmic third-party intermediaries was first manifested in news organizations using Search Engine Optimization (SEO) to beat search engine algorithms (Dick Citation2011), and later included tactics such as adjusting distribution strategies to meet social media feeds’ algorithmic design (Dwyer and Martin Citation2017; Meese and Hurcombe Citation2021) and reorienting the news business around data-driven and algorithm-powered approaches to production and distribution (Van Dijck, Poell, and Waal Citation2018). Ultimately, because of the ubiquity of digital platforms as a primary means of information discovery and distribution in a world of smartphones, search, and social media, it is difficult for news producers to reach the public (and vice versa) without the content being affected in some way by platforms. The ongoing platformization of news distribution continues apace.

The increasing use of algorithms in automated news distribution is a focal point of tension because “algorithmic judgement presents a fundamental challenge to news judgement based on the twin beliefs that human subjectivity is inherently suspect and in need of replacement, while algorithms are inherently objective and in need of implementation” (Carlson Citation2018, 1755). In investigating algorithmic news distribution, scholars have generally looked at platform companies and their public documents, or have interviewed software developers and engineers—though the lack of technical know-how among social scientists has sometimes limited their inquiries, and the “black box” character of algorithmic systems remains a conundrum regardless (Pasquale Citation2015; Van Dijck, Poell, and Waal Citation2018). Moreover, Nechushtai and Lewis (Citation2019, 309) highlight the difficulty in studying algorithmic news distribution, indicating that “because there is no agreed-upon standard for human news gatekeepers, assessing the performance of machines in the role is doubly complicated.” Helberger (Citation2019) furthers the discussion by asking the important normative question of what kind of algorithmic news recommenders we want to align with our values — and what those values should be in the first place. The study of algorithmic news distribution thus remains an open-ended and ongoing process in the field.

Chinese Platforms as Rising Contenders in a Global Contest

Thus far, most studies on technology and journalism have concentrated on liberal democracies. Relatively few have focused on contexts outside the Western platform ecosystem. Given the dominant roles of platforms globally, it is crucial to examine other parts of the world, especially with the emergence of major global platforms in China. At present, the global platform economy is dominated by American and Chinese models, with Europe squeezed in between, largely depending on the infrastructures developed by the platform companies from the U.S. and China (Van Dijck, Poell, and Waal Citation2018). In recent years, China’s platforms have experienced rapid development and become ubiquitous, supported by the government’s Internet Plus and China 2025 policies (Keane Citation2016). Though there is the omnipresent spectre of regulation, the Chinese government previously had allowed for-profit platforms to grow, with some of these selling data services (such as analytics and cloud computing) to help facilitate local government surveillance of online opinion and activities (Hou Citation2020). The Silicon Valley-modelled Chinese tech giants promoted a Western-style liberal ethos of entrepreneurial success while appeasing party officials to execute a “collectivist national agenda that calls for mass innovation, in which the revitalisation of the nation is first and foremost” (Keane and Chen Citation2019, 1).

The case of China thus matters not only for its technological impact globally but also because its political context departs from the democratic assumptions usually implicit in much of the social sciences. The Chinese case challenges Western conceptions of governance, citizenry, and civil society, including the often taken-for-granted liberal democratic role of journalism that does not so easily transfer to the “non-liberal-democratic” context of China (Meng Citation2018; Zhao Citation2008). It is important to ask, therefore, how various institutions seek to shape platforms and journalism in their ambitions to dominate the digital information space, and with what corresponding implications for journalism and the public. This is because the vision of society that unfolds in China, including as it is manifested in this study of platformization of news distribution, might lend a clue for understanding China’s promotion of its own global alternative to liberal democracy.

Theoretical Framework and Research Questions

When Platform Ecosystem Meets News Ecosystem

While the conceptualization of platformization of news points our attention to look beyond individual news outlets and legacy news media to a more general awareness of the platform ecosystem and its selection mechanism, how the “platform ecosystem” interacts with the “news ecosystem” has yet to be looked at through an “ecological” approach that we outline here. We borrow these concepts from platform studies and digital journalism studies, and develop our theoretical framework by merging the “ecosystems” of the two strands of scholarship. While it is beyond the scope of this study to provide a genealogy of either “platform ecosystem” or “news ecosystem” (see Anderson Citation2016 and Van Dijck, Poell, and Waal Citation2018 for more detail), the use of the concept of “ecosystem” in media and communication in general can be traced to the 1960s. Then, practitioners called it “media ecology,” and it was part of a larger turn toward the “ecology” metaphor in various research fields (Anderson Citation2016). Following the lead of Marshall McLuhan (Levinson Citation2000), Neil Postman (Citation2000) coined the term “media ecology” in 1968, arguing that human beings are at the centre of a media “ecosystem” and that this ecosystem affects their perceptions and cognition and thus their behaviour. Forms of media within the media ecosystem are considered as species that could go extinct or evolve to coexist.

The platform ecosystem puts the assemblage of networked platforms at the centre, and considers the ecosystem to be governed by certain mechanisms, including the interplay among technologies, commercial strategies, user practices by individuals, corporations, state institutions, and societal organizations (Van Dijck, Poell, and Waal Citation2018; Van Dijck and Poell Citation2013). It resonates with a news ecosystem concept that encompasses the “entire ensemble of individuals, organizations and technologies within a particular geographic community or around a particular issue, engaged in journalistic production and, indeed, in journalistic consumption” (Anderson Citation2016, 412). A news ecology approach also allows us to look beyond a particular newsroom to view the process of news diffusion as it plays out across digital and physical spaces, involving both human and non-human actors—akin to the Actors, Actants, Audiences, and Activities socio-technical model of news work developed by Lewis and Westlund (Citation2015). Thus, the media ecosystem approach stresses the importance and inevitability of various media as filters through which citizens navigate the world. In turn, the platform ecosystem approach highlights the shift of the dominant carriers of meaning in society from traditional media outlets to platforms.

Regardless of their origin, the actors involved will seek legitimate authority as distributors of news as they cannot fill this function otherwise (e.g., they need to have social autonomy as standalone institutions) (Vos Citation2019). To investigate and understand the institutional actors that are striving to be acknowledged as authoritative distributors of news is in society, it is necessary to zoom out from individual platforms or news organizations and look at the environment in which they are engaged. Thus, any organization involved in the distribution of news will relate to many other organizations whose behaviour will impact their standing and autonomy as legitimate distributors of news. Consequently, a first task is to identify the key actors in this ecosystem, the institutions from which they arise, and their characteristics. Therefore, our first research question asks: Who are the actors in the ecosystem of platformitized news distribution in China, and what are their key characteristics (RQ1)?

After the institutional actors have been identified, we move the focus to our designated actor, Jinri Toutiao, to better understand its inner workings and interactions with the other institutional actors.

Platform Logic and the Institutional Boundaries of Journalism

While the ecological approach allows us to identify the actors, we draw from institutional theory to understand those actors as competitors trying to influence each other’s paths, in accordance with how they are each driven by distinct institutional logics based on their beliefs, norms, rules, and practices, among other things (Thornton and Ocasio Citation1999). The journalistic institution is guided by norms and values stemming from overlapping and conflicting professional, commercial, technological, and cultural logics that coexist and create tensions (Belair-Gagnon and Revers Citation2018). Journalism in China, for example, cannot be seen as a mere extension of the Chinese government, even though processes of journalistic professionalization in China historically have been constrained by the government’s control. Since the Open and Reform period in the late 1970s, and though their fulfillments vary under different eras of political leadership, at least four types of orientations have coexisted in China’s journalistic institutions—namely, directing public opinion, providing information, making profits, and criticizing or investigating wrongdoings of the powerful. The space for the last orientation, which is inspired by both the Western journalistic profession and Chinese intellectuals’ tradition of seeing themselves as being responsible for speaking for people and educating people (Hassid Citation2012), has doubtlessly diminished because of increasing political pressure and a growing commercial orientation in the Xi era. Additionally, the introduction of new technologies has left Chinese journalists with a greater sense of uncertainty, as the shift of news distribution and consumption to digital platforms has, much as in the West, weakened traditional news organizations’ readership and advertising revenue. Thus, to examine the platformization of news through institutional theory, we must account for internal and external logics that interact when boundaries across different institutional orders are transgressed, and we need to include in that study the institutional logics of the platforms themselves as well as the institutional logics of Chinese political, technological, commercial, and media organizations.

As of now, many have heard about the hit video-sharing app, TikTok, which has become a worldwide social media phenomenon since its launch in 2018. However, not many of its users know the platform company behind it—Chinese tech firm ByteDance. The ByteDance saga began in China in 2012 when the Chinese smartphone equipment was booming. Its first core product, news aggregator Jinri Toutiao (“Today’s Headlines”) quickly became a household app in China with its unparalleled ability to identify users’ interests, thanks to the algorithms that powered its news distribution. As new actors such as Jinri Toutiao supplement, compete with, or take over the news distribution that previously was dominated by legacy news organizations, it raises questions about the values and practices that guide news distribution on various platforms. It is particularly important to understand the beliefs, values, rules, and practices that were present in its constitutive moment—e.g., when the entity emerges as something distinct from the larger environment (Örnebring and Karlsson Citation2022). Such elements have a shaping influence because organizations are inclined to path dependency (David Citation1994). Moreover, this is particularly important for a first-mover because it has the potential to set a precedent that later arrivals adapt to, in what is described as institutional isomorphism (DiMaggio and Powell Citation1983). Implicitly, this is also a question about which logics prevail in guiding practices relative to those logics that have traditionally shaped journalism (and continue to do so). Previous research has suggested that platforms and their algorithms treat information differently than an organization within the journalistic tradition. In contrast to journalism’s focus on content, platforms are more interested in who your friends are and who interacts how and with what—and, above all, how those interactions with the platform contribute to securing its central position in the wider information ecology and its ability to generate revenue based on such dominance (DeVito Citation2017).

To explore the drivers behind how this platform operates, the second research question asks: What is the inner logic of Jinri Toutiao guiding the distribution of news (RQ2)? We ask this question for two reasons. First, there is too little understanding about how platforms operate in general and in China in particular. Second, and more importantly in the context of this study, we need to understand the internal logic of this institutional actor to inform our understanding of how it interacts with other actors, such as the journalistic institution. Because although platforms are given great significance, and rightly so, they are still a part of a larger system in which autonomy must be negotiated relative to the institutional logics from neighbouring institutions that either stimulate or hinder platform innovations (see Nieborg and Poell Citation2018 for a detailed argument). As for the institutional logics in the Chinese context, the combination of state-owned enterprise restructuration and the political-institutional logic of the Chinese bureaucracy generates tensions between “the uniformity in policymaking and flexibility in implementation, incentive intensity and goal displacement, bureaucratic impersonality and the personalization of administrative ties” (Zhou Citation2010, 47).

As institutions with different goals interact and seek to advance their goals in relation to each other, it becomes important to understand how algorithmic news distribution challenges and potentially interrupts the centralized nature of news media in China and the roles those institutional actors play and the strategies they employ. Institutions are competing for resources and relying on each other to develop social legitimacy, influence other institutions, and serve their own ambitions (Rhodes Citation2007). Any new institution that emerges (such as platforms) or existing institutions (such as entertainment companies moving into news production and the shaping of opinion) that try to move into and occupy a space in an already established network of institutions is likely to create some friction, causing other institutions to respond, lest they lose their influence and ability to achieve their goals. In the Chinese political context, the strongest institution is presumed to be the government (e.g., see the concept of coercive isomorphism in DiMaggio and Powell Citation1983), but other institutions have room to manoeuvre, too—thus offering an opportunity for them to increase their autonomy and influence the behaviour of other institutions to align with their goals. This continuous positioning and negotiation should in some way be observable and inform how institutional actors form alliances, further their own interests, and hinder others. For that reason, and to be able to explore the inter-institutional struggles, our third and final research question is: How does Jinri Toutiao try to strengthen its own position in the news distribution ecosystem, and how are other institutional actors reacting (RQ3)? Since this is a process that goes on through several years, with ebbs and flows, it is best tracked over time.

Methodology

To answer RQ1, it is imperative to have a general picture of the ecosystem of the platformization of news by charting the landscape of algorithmic news distribution market in China. In this study, we map the field by identifying all major service providers in the Chinese market and collect relevant data on them, such as ownership detail, years since launch, and the level of human intervention in their use of algorithms, altogether offering a general overview of the algorithmic news distribution market. RQ2 and RQ3 zoom in on Jinri Toutiao. The news aggregator, also known as “Today’s Headlines” in Chinese, was first launched in 2012 and is the flagship product from the Chinese tech firm ByteDance, which is also the parent company of the viral short-video sharing platform TikTok. Toutiao uses an algorithm-powered recommendation system to offer personalized news feeds, and is an example of the platform logic of China’s news ecosystem. The single case study design is a suitable empirical method to examine contemporary real-world circumstances and address inquiries in concrete social phenomena (Yin 2018).

This study is inspired by Bucher’s (Citation2018) call to tackle the seemingly blacked-boxed nature of algorithms, and “reverse engineer” known unknowns to map the operational logics of algorithms. As for the empirical material, the data comprise multiple sources of evidence (see Appendix), triangulated on three levels: first, primary data (materials with ByteDance being the primary source), such as publicly available documents, including company reports, terms of services, records of company press conferences, public letters from the CEO, more than four hours of CEO interviews in video format on various channels, and other interviews in text formats; second, contextual material, such as laws and regulations from Chinese authorities, including China’s newly issued laws on platform governance and directives on algorithmic recommendation systems, court case documentation related to ByteDance in regards to copyright disputes and unfair competition among others legal cases, and other relevant policies and official statements; third, discursive material, as in news articles and industry reports that address algorithmic news distribution and public discussion around platformization.

For data analysis, we rely on our theoretical framework and establish a chain of evidence as suggested by Yin (2018). We do not treat the records as firm evidence but examine them for what they are and their intended goals; the analysis of the qualitative materials involved an iterative process of skimming (superficial examination), reading (thorough examination) and interpretation (Bowen Citation2009). The findings and analysis were communicated within the research team to ensure that a uniformed analytical approach was employed and that the results were interpreted through a consistent theoretical lens. The methodological and conceptual approach, inspired by Denzin (Citation1989), allowed us to triangulate the combination of methods and theoretical perspective that leads to an increase of understanding about the platformization of news in China. Such a “fully grounded interpretive research approach” (Denzin Citation1989, 246) is suitable for us to analyse such a new technological development in journalism and society, one that reveals key dynamics among various institutional actors and offers a window into the platformization of journalism both generally and in the non-Western context specifically.

Findings and Analysis

Mapping Algorithmic News Distribution

Our first research question asked: Who are the actors in the ecosystem of platformitized news distribution in China, and what are their key characteristics? maps the landscape of Chinese algorithmic news distribution. Given that most Chinese internet use is on mobile, the table catalogues predominant news distribution channels on mobile devices, including algorithm-oriented news platforms, portal-originated news platforms, news organizations’ apps, social media, and mobile web browsers that together cover most of the institutional actors involved in algorithmic news distribution. For each of these five news distribution channels, we have listed the 2-4 major products, their parent companies, ownership attributes (privately owned or state-owned), the year the product launched, the year algorithms were first used, the number of monthly active users, and the intensity of human gatekeeping (according to the companies’ own announcements and explanations; we classify the intensity as “weak,” “middle,” and “strong”). This mapping thus gives an overview of the development, key focus, and institutional affiliation of the main organizations.

Table 1. The landscape of Chinese algorithmic news distribution.

Much as in the West, the platformization of news in China also started with a historical process of “‘unbundling’ and ‘rebundling’ of news content, audiences, and advertising” (Van Dijck, Poell, and Waal Citation2018, 51). In China, this was initiated mainly by a group of nationwide portal websites, such as Sina, Sohu, and Netease, and a plethora of local portal websites at provincial, municipal, county, and township levels.

Soon after the introduction of Apple’s iOS mobile operating system in 2007 and Google’s Android mobile operating system the following year, the Chinese social media platforms Weibo (launched in 2009 by Sina) and WeChat (launched in 2011 by Tencent) gained enormous popularity, leading news organizations and even public sectors at all levels to flock to open their own accounts on Weibo and WeChat to compete for online visibility. At the same time, the key players in the era of portals—Netease (which launched its news app in 2010), Sohu (2010), Sina (2013), and Tencent News (2010, based on its success in QQ, an instant messaging software)—continued to share the news distribution market by expanding their business as providers of the primary news aggregator apps. Mobile browsers, such as UC Browser App, QQ Browser App, 360 Browser App, and Baidu App, also clustered news in their homepages, becoming another venue where smartphone users could encounter news. To compete with these platforms, large news organizations in China, including Phoenix News (privately owned, from Hong Kong), People’s Daily (state-owned), Xinhua News Agency (state-owned) and The Paper (state-owned), also launched their news apps—but, generally speaking, they are much less popular than news aggregators and social media platforms.

The launch of Jinri Toutiao (or Toutiao) by ByteDance in 2012 is seen as the first use of algorithms in news distribution in China, three years after Facebook started to use algorithms in its news feed (Bucher Citation2018, 74). Its great success in personalized news distribution attracted many market followers, such as Yidianzixun (launched in 2013), Tiantian Kuaibao or Kuaibao (launched in 2015 by Tencent), and Qutoutiao (launched in 2016). It also triggered news portals to shift from an “editorial distribution” model, which underlines a human editor’s choices and arrangements in news distribution, to an “algorithmic distribution” model, which emphasizes algorithms’ decision-making power for personalized news distribution (China Internet Network Information Center Citation2017; Xie, Yang, and Yu Citation2021), even as most news portals today still claim that they are using a “mixed” model. By 2016, most Chinese platforms had adopted algorithms to personalize users’ news consumption (Jia Citation2019). In recent years, the state-owned news organizations also commenced to use algorithms in news distribution (and news production) processes, even as they emphasized that their algorithms are “mainstream algorithms” that can promote “mainstream value” (Zhang and Zhang Citation2020).

Distribution ≥ News

Concerning RQ2 and the inner logic of Jinri Toutiao, there are five key facets behind the design of its algorithmic system and operation of the company: (1) technology at its core, (2) “turning audience into users,” (3) an apparent lack of understanding or disregarding of journalistic values, (4) pursuit of sustainable growth, and (5) elements of ethical concerns. In the paragraphs that follow, we explain each logic in detail, providing empirical evidence for such claims and analysing the underlying motives as well as the implications of these logics.

Core Technology is the Backbone

The key explanation of Toutiao’s success, in terms of user growth, can be found in its technology, namely the recommendation algorithms, a pride of ByteDance founder Zhang Yiming. With a degree in software engineering, experience from various tech companies, and an interest in entrepreneurship, he founded a real-estate website, JiuJiuFang, in 2009. Itching for something more interesting and with an urge to catch the wave of the growth of mobile Internet in China, Zhang identified a news recommendation system as his next aim for a business start-up. Zhang’s goal was to use technology to better match content to users and to build a news aggregator for mobile devices. Indeed, of the 100 founding staff members at Toutiao, nearly all were engineers or other technologically oriented personnel. While the product was named “Today’s Headline” in a clear reference to news, none of the initial staff had a journalistic background. Zhang took great pride in the product, boasting of its uniqueness because “every time you open it, it will give you what it believes is most fitting for you to read at that time. It constantly ‘touches’ your interests. What everyone sees is different. And the longer you use it, the better it understands you, and the better it recommends content to you” (Appendix Item 28, 2014).

The power of recommendation algorithms worked. In 2014, Toutiao had reached more than 10 million daily active users within two years of launch. The focus on technology may have brought the company a level of audience success, but it also blinded the firm from taking into account other values (elaborated below). Thus, recommendation systems and staff who can understand and program them were key aspects of Toutiao’s constitutive moment. The next step is to understand what guides the recommendation system, its algorithms, and the engineers overseeing it.

Recommendations Built around Satisfying Users

“Headline is only what you care about” claimed the product’s first slogan. This suggests that a news app powered by algorithms, with no human editors, centred itself on user interests, specifically by feeding users not what they should see (a common journalistic value) but what they may want to see. In 2015, during a keynote speech at a tech innovation summit, Zhang disclosed that Toutiao relied on three main types of user information for content recommendation: (1) action characteristics, including clicks, stops on screen, movements on screen, comments, and shares; (2) environmental characteristics, including GPS location, whether connected to Wi-Fi or 3G, whether it’s a workday or holiday, etc.; and (3) social characteristics, including a user’s social graph on the social networking platform Weibo and a history of their posts.

In a commentary titled Machine replaces Editors? (Appendix Item 28, 2014), Zhang highlighted the logic of “turning audience into users,” and revealed how Toutiao builds a “DNA interests map” within five seconds when a user logs in to the Toutiao app with their Weibo account. Such a map is a statical model based on tags of users’ SNS accounts, followers, friends, comments or reposts, etc., as well as the mobile device the user uses, the location, and time of usage. This illustrates the logic that the user is at the core of the design of such news aggregator and that the user knows their information needs best. However, such a focus on user engagement has resulted in the proliferation of some low-quality content, such as vulgarity, pornography, and violence that are often more eye-catching than traditionally higher-brow news content. It also exacerbated the phenomenon of repackaging original content and reposting, or what is called manuscript laundering in China (Xie, Yang, and Yu Citation2021). While protecting original content has always been a challenge under China’s weak copyright laws, the rise of algorithmically driven platforms has magnified such a problem. Parallel to the increased salience of user data, traditional journalistic norms and practices were downgraded.

“We Are a Tech Company, Not a Media Company”

Initially, the content served on Toutiao was largely taken from news organizations, among other content producers. It called itself “Toutiao” (headlines) but had little regard for journalistic values. In the early days of the company, Zhang had repeatedly said in public that Toutiao is a tech company and not a media company. While acknowledging humans with creativity would not be completely replaced by machines, Zhang had also believed in the neutrality of technology and that the bottom line was abiding by laws and regulations. In a 2016 interview, Zhang said, “The media should have values. It should educate people and disseminate opinions, which we do not advocate because we are not media. We are more concerned with the throughput and multiplicity of information. At the same time, we really shouldn’t get involved in the [values] debate, and we are not in a position and have no capacity to do so.” He added, “If you had to ask me what the values of Toutiao (as a company) are, I think it is to improve the efficiency of distribution and meet the information needs of users, this is the most important (Appendix Item 15, 2016).”

In this regard, Toutiao focused on information distribution, where the distribution aspect matters more than the information being conveyed. Zhang had also expressed frustrations when faced with copyright challenges from news organizations, saying that his platform had helped news organizations increase their visibility. It was not until 2018 that Toutiao acknowledged its role as a “platform company.” In doing so, Zhang said, “Such as clickbait, fake news, and anti-addiction systems for minors, as a platform, we have the responsibility to minimize platform-based problems as much as possible” (Appendix Item 10, 2018). In sum, something other than journalistic virtues and its overarching goal of public enlightenment is guiding the behaviour of the platform (at least rhetorically).

Capitalizing on the Power of Recommendation Algorithms

Toutiao’s revenue model is based on advertising. Zhang Yiming highlighted the recommendation algorithms’ power in matching advertisements to potential customers, which resulted in a higher return on investment of advertisement placement on Toutiao. He also indicated the goal of commercialization of its product is to “make advertisement a piece of useful information” (Appendix Item 28, 2014), saying that even if advertisements on the platform were clearly labelled as ads, users do not mind because of their relevance based on personalized recommendations. In fact, Zhang took pride in Toutiao being the “first company in China exploring native advertising” since its commercialisation in November 2013 (Appendix Item 28, 2014).

As the aggregator has relied on a growing amount of user generated content (UGC) to provide information for its users, Toutiao has tried to keep users engaged by “sharing the profits.” It has created many projects to diversify the revenue streams for the creators, from cash rewards to traffic sharing to paid content, among other means. As the company’s algorithm architect, Cao Huanhuan, put it when explaining the design principles of Toutiao’s algorithmic system, “Jinri Touriao, as a content sharing platform, has to provide value for content creators and let them create with dignity. It also has the obligation to satisfy its users—such needs need to be balanced. In addition, there is the interest of advertisers that need to be taken into consideration. These is a process of negotiation and balancing” (Appendix Item 29, 2018).

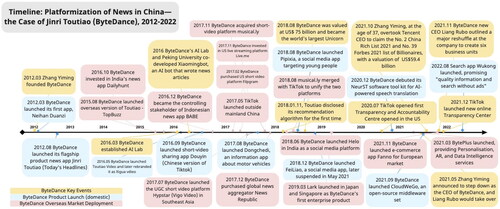

By capitalizing on the power of its algorithms and the user data collected, the company has expanded its business (see for a timeline of ByteDance development since its foundation). It spun out numerous products in social media, photography, and e-commerce, culminating with the huge success of the video-sharing app Douyin, which was launched in September 2016 in China, and later went viral globally (TikTok is Douyin’s international version). The company’s focus on continuous growth lies in its early stage strategic deployment and global ambition. It has also dipped its toes in other sectors, such as education, gaming, and autonomous vehicles. However, the sustainability of such growth came into question with a recent reshuffling of the company leadership, a restructuring of the business units, and a company-wide downsizing, amid increasing scrutiny and tightening regulations on platforms both domestically and globally. TikTok, for instance, as one of ByteDance’s major international business, is under persistent attacks for sharing international users’ data with the Chinese authority, despite ByteDance’s denials in many occasions (Baker-White Citation2022). The company experienced stagnant growth in domestic advertising revenues in the first half of 2021, for the first time since its commercialization in 2013.

Good Faith and Corporate Social Responsibility

As Toutiao was born out of Zhang’s idea of satisfying people’s information needs, giving people greater value through information discovery has been the driving goal of the company. In 2018, this goal was articulated in the company’s new slogan: “Information creates value.” Toutiao has explained how it aimed to create such value in a press conference disclosing the Principles of Jinri Touriao Recommendation System, held in January 2018. It was also answering the call from society and regulators for opening the “black box” of the algorithmic news distribution system, in a bid to increase algorithmic transparency and build trust. The company’s algorithm architect disclosed that, since the launch of the product, the algorithmic system had undergone four major adjustments (Appendix Item 29, 2018), which he outlined in relation to key mechanisms that powered the algorithmic recommendation system: (1) the relevance feature, which evaluates the compatibility between the content and user with regard to keyword, category, theme, and sources; (2) the environmental feature, which collects geolocation of the user and time of use (e.g., content recommendation would vary if you are at home scrolling in bed during the night, or inside a metro on the way to work in the morning); (3) the trendiness feature, which evaluates category trendiness, topic trendiness, and keyword trendiness, which served well during a “cold-boot” of a user, meaning when little information about a given user had yet been collected; and (4) the collaborative feature, which was described as the mean tactic to prevent the “algorithmic recommendation [getting] narrower and narrower,” thereby offering users enough similarity in content recommendations so as to avoid the filter bubble problem.

Cao, the algorithm architect, further highlighted at the press conference the social responsibility of the company, including its “content safety mechanism.” With Toutiao as the largest and most influential information aggregator in China, “even if one percent of the content recommendation goes wrong,” Cao said, “it will result in big societal impact,” and so the company described prioritizing content safety since its foundation. Cao (Appendix Item 29, 2018) revealed different machine learning models are built for three kinds of “risky content,” namely pornography, vulgarity, and hate speech. Other models are also built to detect “low-quality content.” Such machine models are working with human censors to ensure higher “content safety.” Toutiao has also established the Transparency and Accountability Centre as well as a “Toutiao Tracing System,” which is similar to the Amber Alert in the US that helps to find missing people, believing it is “providing information service for the society” (Appendix Item10, 2018).

While these are the stated ambitions of Toutiao, the firm has to work toward accomplishing its goals and imposing its logics on Chinese news distribution in a context where other institutions are trying to realize their goals and logics—ones that may be quite different.

Competition, Collaboration, and Subject of Regulation

The road for development for Toutiao has been a bumpy ride, especially amid growing societal scrutiny and the Chinese state’s increasingly tightened regulations to rein in of platform power. To answer our RQ3—regarding how Jinri Toutiao attempts to strengthen its own position in the network and how are other institutional actors react in turn—we provide a visualization of these dynamics in . In the text to follow, we give an account of the interactions that Toutiao has had with its competitors (including some that later became partners), namely news organizations, other tech platforms, and other actors in the media ecosystem competing for audience attention and with the Chinese state regulators.

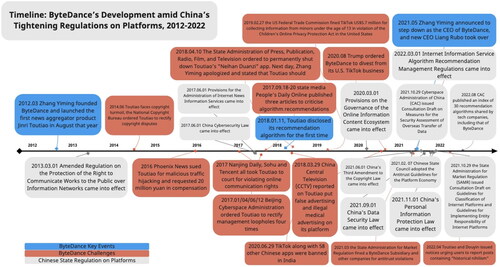

Figure 2. Timeline: ByteDance’s Development amid China’s tightening regulations on platforms, 2012–2022.

Platform and Publisher Symbiosis: Turn Your Enemies into Friends

The popularity of the app has attracted advertisers and generated large revenues for Toutiao. It also made it a target of complaints from other media outlets, especially the ones from which Toutiao borrowed content. In June 2014, Toutiao, which had never paid any licensing fees for using news content, was sued by several news organizations (e.g., Guangzhou Daily, Chutian Metropolitan) and news websites (e.g., Beijing News) for copyright infringement. This was the first crisis Toutiao had faced since its launch. In 2016, Phoenix News sued Toutiao for malicious traffic hijacking and requested 20 million yuan in compensation. In 2017, Nanjing Daily, Sohu and Tencent all took Toutiao to court for violating online communication rights. The lawsuits against Toutiao were piling up. Amid the crisis, Zhang Yiming, who had not expected the copyright issue would be a hurdle for its revenue model, gloated at the publicity that these cases and corresponding news coverage brought, saying that they had turned Toutiao from a “low-profile” company into a “public company” (Appendix Item 2, 2014).

While pointing out that other companies (such as Sohu) do the same in aggregating content, Toutiao adopted a strategy of assimilating the news organizations onto their platform by “collaborating with them one by one,” but with a strong hand— “We disconnect (their websites) if there is no cooperation. No longer link (to them) (Appendix Item 2, 2014).” The strategy worked. Guangzhou Daily, 12 days after it filed the lawsuit against Toutiao, retracted the case and announced a partnership with Toutiao that would allow the two to collaborate in the news market. This is one of the earliest cases of what became more common later: inter-institutional cooperation between platforms and publishers, resulting not in a zero-sum game but a symbiotic relationship. State media started using Toutiao as a channel to disseminate their news, established their official accounts on the platform, and had designated staff responsible for liaising with the platform. Many also established their own news app and explored algorithmic news distribution, as described above. For some major news organizations in China, they apparently did not sense an existential market-based threat, but rather took advantage of the traffic brought by the platform as an effort to stay relevant. As Zhang put it, “every time a new technology comes out, there is a process of disputes, even when radio and television came out. Then, some industry norms will gradually form. I think it is in the process now (Appendix Item 2, 2014).”

The Taming of the Platform

Chinese state control over platforms has intensified in recent years (see ), with the launch of Measures for Cybersecurity Review (2020), Data Security Law (2021), and Personal Information Protection Law (2021), among other rules and regulations (Kuai, Ferrer-Conill, and Karlsson Citation2022). More specifically, the Cyberspace Administration of China along with other regulatory bodies issued a new set of regulations on recommendation algorithms which came into effect on March 1, 2022. There are provisions against generating and aggregating fake news, demanding more transparency over how algorithms function and allowing users to opt out of being targeted with algorithmic recommendations. The regulations also go beyond addressing user rights, mandating recommendation algorithm service providers to “adhere to the mainstream value orientation and actively spread positive energy.” In the eyes of the state, Toutiao not only poses a threat as a platform company growing into different industries but also because of the power that Toutiao has amassed in monopolizing information distribution channels on mobile devices and capturing public attention—an area to which the state attaches great importance because of its interest in ideological conditioning through controlling public discourse.

Not only did that state instruct its own news organization to enhance efforts in media innovation to “safeguard the public opinion battleground,” it also implemented a series of measures to rein in the power of Toutiao. In 2014, the National Copyright Bureau ordered Toutiao to rectify copyright disputes. In 2017, Toutiao had been ordered to rectify management loopholes four times by Beijing Cyberspace Administration, because of the proliferation of “vulgar, violent, gory, pornographic and harmful” information on its platform. In 2018, the State Administration for Market Regulation published Toutiao’s illegal advertising cases.

State-owned media were also mobilized. From September 18 to September 20, 2017, the state media People’s Daily Online published three opinions articles consecutively to criticize algorithmic recommendations, pointing out the risk of information cocoon and saying that “algorithms shouldn’t dictate content” and “watch out for algorithms going to the wrong side of innovation.” In March 2018, China Central Television (CCTV) made investigative reports on how Toutiao circumvented supervision and used its technology to redirect users to advertisers and had placed false and illegal advertising on its platform.

In a major blow, in April 2018 the State Administration of Press, Publication, Radio, Film, and Television (SAPPRFT) ordered the company to permanently shut down its joke app “Neihan Duanzi,” which allowed users to circulate jokes, memes, and humorous videos and had more than 20 million daily active users at the time of its termination. One day later, Zhang wrote an open letter to apologize to the public, stating that Toutiao should “incorporate correct values into technological products”:

I started my business as an engineer, hoping to create a product to facilitate interaction and communication among users around the world. Over the past few years, we have focused more energy and resources on growing our businesses, but not enough on platform regulation and corporate social responsibility, such as effective control of vulgar, violent, harmful content, and false advertising … For a long time, we have overemphasized the role of technology but failed to realize that technology must be guided by socialist core values, spread positive energy, meet the requirements of our time, and respect public order and good morals. (Appendix Item 24, 2018)

Discussion and Conclusion

There are at least two interrelated contributions from this study, both stemming from ecological and longitudinal approaches to studying platforms and their significance for the distribution of news. First, even in a seemingly totalitarian system such as China, there are opportunities for disruptive change in the distribution of information and news, at least initially. The Chinese news ecosystem was revolutionized by platforms and algorithms, especially but not limited to the realm of news distribution. After ByteDance introduced algorithmic news dissemination and gained notable success, news outlets ranging from privately owned enterprises to party mouthpieces tried to follow suit. This suggests that platforms, when capitalizing on the potential power and scale of algorithms, may be successful in exporting their institutional logic to other institutions in the broader information ecosystem (e.g., for an example of mimetic isomorphism, see DiMaggio and Powell Citation1983). Journalistic innovation, be it politically motivated in the Chinese context, or mostly economically driven in the Western setting, needs to answer the questions of how to reach the audience more effectively, how to develop a sustainable model of operation, and how to preserve journalistic values and fulfil its social responsibility amid the new reality of platformization of news. The solution may lie not merely in technological innovation, but rather through innovation of business models, legislation, and governance. Some studies align with our findings, discovering that as news organizations rely on platforms for distribution and as platforms rely on news organizations for production, the two can develop a symbiotic relationship (Xie, Yang, and Yu Citation2021); others, however, point to concerns about the negative consequences that the platformization of news may bring to journalism through inter-institutional collaboration. The platforms may indeed increase the visibility of news in certain instances, but the ever-growing dependency on such algorithms and digital metrics to assess news value risks narrowing our understanding of what counts as good work in journalism, much as Christin (Citation2020) observed in the Western context, or it may facilitate the circulation of vulgar content, as observed in the Chinese context (Xie, Yang, and Yu Citation2021). Moreover, sentiments, analytics, and tools provided by platforms may further create what Nechushtai (Citation2018) terms “infrastructure capture,” leading to news organizations bending to platforms’ interests. Ultimately, this collaboration points to the weakening of the journalistic institution—in the first step by a reliance on platforms, and in the second step as the platforms become tamed by the political institution.

Second, to understand why institutional actors act the way they do, it is necessary to look at the broader environment and the inter-institutional exchanges and adaptation that occur therein. The expansion and influence of a platform logic, our findings suggest, is subject to environmental constraints and can be modified through interactions with other institutional actors. These exchanges can be understood as a function of coercive isomorphism, or the formal or informal pressures to conform that organizations encounter as they attempt to meet cultural expectations in society or the demands that arise from regulators or other entities on which they depend (DiMaggio and Powell Citation1983). In the case of ByteDance, there is an evident discursive shift and attitude change from former CEO Zhang Yiming, from insisting “technology is neutral” to “technology needs to be guided by correct values.” This suggests that alternative articulations of platform mechanisms are not only possible but also involve a constant struggle between competing value regimes and ideological systems. Our study shows how China has intensified regulations in cyberspace and tightened its grip in reining in platform power, and how effective such measures have been. This means the mutual shaping of platforms and society that is described in social studies of technology is not a given; instead, it is a dynamic process shaped by practices from different actors, including but not limited to competition and regulatory bodies.

There are also signs that, possibly contrary to popular Western belief, Chinese platform companies demonstrate normative isomorphism (DiMaggio and Powell Citation1983), in that they alter their ethos and ethical concerns in response to the environment. In the case of ByteDance, the company made an effort to promote algorithmic transparency and accountability long before some of its Western counterparts. Interestingly, the company—which first developed its algorithmic system via its news aggregator and data collected from news readers—has not only diversified its product offerings and dipped into less politically sensitive sectors such as entertainment, but it is also expanding overseas. ByteDance’s move to downgrade the importance of news in its business profile could be a reaction to China’s increasingly repressive media environment. It also shows that transferable technology gives platform companies the edge in occupying other sectors and growing beyond national borders. However, as domestic forces intensify in reining in platform power, and with complicated geopolitics in overseas markets, many uncertainties lie ahead for ByteDance’s future.

In closing, the study offers a unique contribution by looking at journalistic innovation in China, which remains understudied in a field dominated by studies of Western democracies. The Chinese case serves an important role in enhancing our understanding of the dynamics among government, news organizations, and platforms. Further research might explore the audience’s perspective on this issue, as the fusion between the platform ecosystem and news ecosystem has also not only revolutionized the way people consume news but also challenged how people perceive, define, and experience news. As China and the West (mainly Europe) are converging in cyberspace regulation and data protection, platformization in China is worthy of ongoing examination, for the global contest of platforms is nowhere near to being settled.

Appendix.docx

Download MS Word (24.9 KB)Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the anonymous reviewers, the special issue editors and the Digital Journalism Editorial Team for their valuable feedback that helped to improve this article.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Anderson, Chris W. 2016. “News Ecosystems.” In The SAGE Handbook of Digital Journalism, edited by Tamara Witschge, C. W. Anderson, David Domingo, and Alfred Hermida, 410–423. Croydon, London: Sage.

- Baker-White, Emily 2022. “Leaked Audio From 80 Internal TikTok Meetings Shows That US User Data Has Been Repeatedly Accessed From China.” BuzzFeed News, June 17. https://www.buzzfeednews.com/article/emilybakerwhite/tiktok-tapes-us-user-data-china-bytedance-access

- Belair-Gagnon, Valerie, and Matthias Revers. 2018. “The Sociology of Journalism.” In Journalism, edited by Tim P. Vos, 257–280. Handbooks of Communication Science, Volume 19. Boston, MA: Walter de Gruyter Inc.

- Bowen, Glenn A. 2009. “Document Analysis as a Qualitative Research Method.” Qualitative Research Journal 9 (2): 27–40. https://doi.org/10.3316/QRJ0902027.

- Bucher, Taina 2018. If…Then: Algorithmic Power and Politics. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Carlson, Matt 2018. “Automating Judgment? Algorithmic Judgment, News Knowledge, and Journalistic Professionalism.” New Media & Society 20 (5): 1755–1772. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444817706684.

- China Internet Network Information Center 2017. “2016年中国互联网新闻市场研究报告 [2016 China Internet News Market Research Report].” Beijing: China Internet Network Information Center. http://www.cac.gov.cn/files/pdf/cnnic/newsmarket.pdf.

- Christin, Angèle 2020. Metrics at Work: Journalism and the Contested Meaning of Algorithms. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- David, Paul A. 1994. “Why Are Institutions the 'Carriers of History’?: Path Dependence and the Evolution of Conventions, Organizations and Institutions.” Structural Change and Economic Dynamics 5 (2): 205–220. https://doi.org/10.1016/0954-349X(94)90002-7.

- Denzin, Norman K. 1989. The Research Act: A Theoretical Introduction to Sociological Methods. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

- DeVito, Michael A. 2017. “From Editors to Algorithms: A Values-Based Approach to Understanding Story Selection in the Facebook News Feed.” Digital Journalism 5 (6): 753–773. https://doi.org/10.1080/21670811.2016.1178592.

- Diakopoulos, Nicholas 2019. Automating the News: How Algorithms Are Rewriting the Media. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Dick, Murray 2011. “Search Engine Optimisation in UK News Production.” Journalism Practice 5 (4): 462–477. https://doi.org/10.1080/17512786.2010.551020.

- DiMaggio, Paul, and Walter W. Powell. 1983. “The Iron Cage Revisited: Institutional Isomorphism and Collective Rationality in Organizational Fields.” American Sociological Review 48 (2): 147–160. https://doi.org/10.2307/2095101.

- Dwyer, Tim, and Fiona Martin. 2017. “Sharing News Online.” Digital Journalism 5 (8): 1080–1100. https://doi.org/10.1080/21670811.2017.1338527.

- Hassid, Jonathan 2012. “Four Models of the Fourth Estate: A Typology of Contemporary Chinese Journalists.” The China Quarterly 208: 813–832.

- Helberger, Natali 2019. “On the Democratic Role of News Recommenders.” Digital Journalism 7 (8): 993–1012. https://doi.org/10.1080/21670811.2019.1623700.

- Hou, Rui 2020. “The Commercialisation of Internet-Opinion Management: How the Market is Engaged in State Control in China.” New Media & Society 22 (12): 2238–2256. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444819889959.

- Jia, Jun 2019. “算法推荐新闻:技术困境与范式变革.” [Algorithm Recommendation News: Technological Dilemma and Paradigm Change].” 西南民族大学学报(人文社会科学版) [Journal of Southwest Minzu University (Humanities and Social Science)] 5: 152–156. http://xnmzxbsk.ijournal.cn/ch/reader/create_pdf.aspx?file_no=20190519&year_id=2019&quarter_id=5&falg=1.

- Kalogeropoulos, Antonis, Richard Fletcher, and Rasmus Kleis Nielsen. 2019. “News Brand Attribution in Distributed Environments: Do People Know Where They Get Their News?” New Media & Society 21 (3): 583–601. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444818801313.

- Keane, Michael 2016. “Internet + China: Unleashing the Innovative Nation Strategy.” International Journal of Cultural and Creative Industries 3 (2): 68–74. https://espace.curtin.edu.au/bitstream/handle/20.500.11937/50534/250277.pdf?sequence=2.

- Keane, Michael, and Ying Chen. 2019. “Entrepreneurial Solutionism, Characteristic Cultural Industries and the Chinese Dream.” International Journal of Cultural Policy 25 (6): 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1080/10286632.2017.1374382.

- Kuai, Joanne,Raul Ferrer-Conill, andMichael Karlsson. 2022. “AI ≥ Journalism: How the Chinese Copyright Law Protects Tech Giants’ AI Innovations and Disrupts the Journalistic Institution.” Digital Journalism. http://doi.org/10.1080/21670811.2022.2120032.

- Levinson, Paul 2000. “McLuhan and Media Ecology.” In Proceedings of the Media Ecology Association, 1:17–22. https://www.media-ecology.org/resources/Documents/Proceedings/v1/v1-03-Levinson.pdf.

- Lewis, Seth C, and Oscar Westlund. 2015. “Actors, Actants, Audiences, and Activities in Cross-Media News Work.” Digital Journalism 3 (1): 19–37. https://doi.org/10.1080/21670811.2014.927986.

- Lin, Bibo, and Seth C. Lewis. 2022. “The One Thing Journalistic AI Just Might Do for Democracy.” Digital Journalism. 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1080/21670811.2022.2084131.

- Meese, James, and Edward Hurcombe. 2021. “Facebook, News Media and Platform Dependency: The Institutional Impacts of News Distribution on Social Platforms.” New Media & Society 23 (8): 2367–2384. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444820926472.

- Meng, Bingchun 2018. The Politics of Chinese Media: Consensus and Contestation. New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Nechushtai, Efrat 2018. “Could Digital Platforms Capture the Media through Infrastructure?” Journalism 19 (8): 1043–1058. https://doi.org/10.1177/1464884917725163.

- Nechushtai, Efrat, and Seth C. Lewis. 2019. “What Kind of News Gatekeepers Do We Want Machines to Be? Filter Bubbles, Fragmentation, and the Normative Dimensions of Algorithmic Recommendations.” Computers in Human Behavior 90 (January): 298–307. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2018.07.043.

- Nieborg, David B, and Thomas Poell. 2018. “The Platformization of Cultural Production: Theorizing the Contingent Cultural Commodity.” New Media & Society 20 (11): 4275–4292.

- Örnebring, Henrik, and Michael Karlsson. 2022. Journalistic Autonomy: The Genealogy of a Concept. Columbia, MO: University of Missouri Press.

- Pasquale, Frank 2015. The Black Box Society. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Postman, Neil 2000. “The Humanism of Media Ecology.” In Proceedings of the Media Ecology Association, 1:10–16.

- Quest Mobile. 2021a. QuestMobile2020 中国移动互联网年度大报告·下 [QuestMobile2020 China Mobile Internet Annual Report · II]. Beijing: Quest Mobile. https://www.questmobile.com.cn/research/reportnew/143

- Quest Mobile. 2021b. QuestMobile2021 中国移动互联网秋季大报告 [QuestMobile2021 China Mobile Internet Autumn Report]. Beijing: Quest Mobile. https://www.questmobile.com.cn/research/reportnew/177

- Rhodes, R. A. W. 2007. “Understanding Governance: Ten Years On.” Organization Studies 28 (8): 1243–1264. https://doi.org/10.1177/0170840607076586.

- Shi, Hongmei. 2020. 流量博弈中的电商成长路径: 电商行业专题系列报告 (二) [The growth path of e-commerce in the traffic game: E-commerce industry special report series (II)]. Shanghai: Orient Securities. https://pdf.dfcfw.com/pdf/H3_AP202009161413205891_1.pdf?1600245742000.pdf

- Thornton, Patricia H, and William Ocasio. 1999. “Institutional Logics and the Historical Contingency of Power in Organizations: Executive Succession in the Higher Education Publishing Industry, 1958– 1990.” American Journal of Sociology 105 (3): 801–843. https://doi.org/10.1086/210361.

- Thorson, Kjerstin, and Chris Wells. 2015. “How Gatekeeping Still Matters: Understanding Media Effects in an Era of Curated Flows.” In Gatekeeping in Transition, edited by Timothy Vos and François Heinderyckx, 25–44. New York, London: Routledge.

- Van Dijck, José, and Thomas Poell. 2013. “Understanding Social Media Logic.” Media and Communication 1 (1): 2–14. DOI:https://doi.org/10.17645/mac.v1i1.70.

- Van Dijck, José, Thomas Poell, and Martijn De Waal. 2018. The Platform Society: Public Values in a Connective World. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

- Vos, Tim P. 2019. “Journalism as Institution.” In Oxford Research Encyclopedias. Oxford University Press. Online. https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190228613.013.825

- Xie, Emilie, Qiguang Yang, and Sun Yu. 2021. Cooperation and Competition: Algorithmic News Recommendations in China’s Digital News Landscape. New York: The Tow Center. https://www.cjr.org/tow_center_reports/cooperation-and-competition-algorithmic-news-recommendations-in-chinas-digital-news-landscape.php.

- Zhang, Jian, and Shenyuan Zhang. 2020. “人民日报客户端主流算法应用实践” [People’s Daily App’s Mainstream Algorithm Practice].” 人工智能 [AI-View] 2: 90–96. DOI:CNKI: SUN: DKJS.0.2020-02-013

- Zhao, Yuezhi 2008. Communication in China: Political Economy, Power, and Conflict. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers.

- Zhou, Xueguang 2010. “The Institutional Logic of Collusion among Local Governments in China.” Modern China 36 (1): 47–78. https://doi.org/10.1177/0097700409347970.