Abstract

Objective: We aimed to provide an overview of telehealth used in the care for patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), and identify the barriers to and facilitators of its implementation. Methods: We searched Pubmed and Embase to identify relevant articles. Full-text articles with original research reporting on the use of telehealth in ALS care, were included. Data were synthesized using the Consolidation Framework for Implementation Research. Two authors independently screened articles based on the inclusion criteria. Results: Sixteen articles were included that investigated three types of telehealth: Videoconferencing, home-based self-monitoring and remote NIV monitoring. Telehealth was mainly used by patients with respiratory impairment and focused on monitoring respiratory function. Facilitators for telehealth implementation were a positive attitude of patients (and caregivers) toward telehealth and the provision of training and ongoing support. Healthcare professionals were more likely to have a negative attitude toward telehealth, due to the lack of personal evaluation/contact and technical issues; this was a known barrier. Other important barriers to telehealth were lack of reimbursement and cost-effectiveness analyses. Barriers and facilitators identified in this review correspond to known determinants found in other healthcare settings. Conclusions: Our findings show that telehealth in ALS care is well-received by patients and their caregivers. Healthcare professionals, however, show mixed experiences and perceive barriers to telehealth use. Challenges related to finance and legislation may hinder telehealth implementation in ALS care. Future research should report the barriers and facilitators of implementation and determine the cost-effectiveness of telehealth.

Introduction

Patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) suffer from progressive disability, which develops at a variable rate, resulting in ever-changing care-needs. Symptomatic management by a multidisciplinary team of specialists is the mainstay of treatment for patients with ALS. This type of care aims to optimize patients’ quality of life and survival (Citation1–5). For this reason, patients should be monitored closely and have continuous access to multidisciplinary care throughout their disease. However, many patients with ALS experience issues with accessing and attending multidisciplinary clinics. These issues are mostly related to long travel distances, difficulty traveling and long days at the clinic (Citation6,Citation7). In addition, there is a lack of monitoring between clinic visits (in ALS care). The access issues and lack of monitoring limit the continuity of multidisciplinary care, which could negatively affect patients with ALS.

Telehealth has the potential to improve the accessibility and continuity of ALS care by enabling the remote provision of care and facilitating remote monitoring. The use of telehealth allows patients to receive specialist care, regardless of their ability to travel, their level of impairment or the distance to a multidisciplinary clinic. Despite these potential benefits and the availability of digital technology, the use of telehealth in ALS care is currently limited. This view is supported by a recent systematic review that looked into the use of digital technology to improve access to specialist ALS care (Citation8). The limited number of studies in the review were mostly feasibility or pilot studies and/or included only a small number of patients with ALS. This lack of (robust) literature suggests that telehealth innovations rarely survive beyond the initial pilot phase and are not implemented into usual ALS care.

These findings indicate that there are issues that hinder the implementation of telehealth in ALS care. In order to facilitate telehealth implementation, we describe its current use in ALS care and aim to identify the barriers and facilitators that influence implementation.

Methods

Search strategy

Comprehensive electronic searches were conducted using Pubmed and Embase to look for articles up until 2019. A clinical librarian was consulted regarding the construction of the searches. Search terms used included “amyotrophic lateral sclerosis” or “ALS” or “motor neuron disease” or “MND” or “ALS/MND”, combined with “telehealth” or “telemedicine” or “mhealth” or “ehealth” or, “telerehabilitation” or “telemonitoring” or “teleconsultation” or “digital technology” or “mobile technology” or “mobile app”. Full search queries for Pubmed are shown in Supplementary material 1; we adjusted these for the other databases. Additionally, reference lists of identified articles were scrutinized and citations of these articles were checked using Google Scholar. Duplicates were removed using Mendeley software.

Inclusion criteria for review

To be eligible, a study had to meet following criteria: (a) a full-text article with original research, (b) >75% of the study population had to be patients with ALS, (c) report on the use or implementation of telehealth in a healthcare setting, (d) published in English, (e) published in a peer-reviewed journal. Telehealth was defined as the provision of remote healthcare services through the use of digital and telecommunication technologies. The study methodology was assessed (i.e. study design and recruitment strategy), but was not an inclusion criterion for this review. Two reviewers screened titles and abstracts and selected relevant articles. A full-text assessment, also by two reviewers, determined which studies were eligible for inclusion based on the inclusion criteria.

Analysis method

The framework for the qualitative data extraction was based on the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR) (Citation9). This instrument specifies the determinants that affect the implementation of an innovation. The determinants in this review were divided into four domains from the CFIR: Innovation characteristics, patient/caregiver characteristics, healthcare professional characteristics, and the inner and outer setting. Innovation characteristics include the core components and complexity of the telehealth innovation that is being used or implemented. Patient/caregiver characteristics include the user-experiences/benefits, and compliance of patient/caregiver end-users. The healthcare professional characteristics include the user-experiences/benefits of healthcare professional end-users. The inner and outer setting includes the available resources, and finance and legislation that the organization has to manage. The definitions of each determinant can be found in .

Table 1 Definitions of implementation determinants.

Results

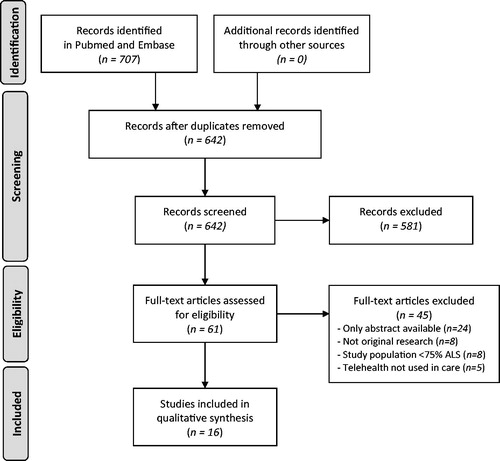

The final literature search was performed on the 6th of November 2019 and identified a total of 707 articles, 61 of which were reviewed for eligibility. After full-text analysis, 16 articles were included in the review. Reasons for exclusion are shown in . At least 429 patients with ALS were included who used telehealth (one study did not report the number of patients); 65.9% of patients were male and the mean age was 60.5 years. Eight of sixteen studies reported the revised ALS Functional Rating Scale (ALSFRS-R) with a mean total score of 28.0; twelve of sixteen studies reported that 67.5% of patients were ventilated through either noninvasive ventilation (NIV) or tracheostomy invasive ventilation (TIV); and six of sixteen studies reported that 29.2% of patients had a gastrostomy. Details of the included studies can be found in .

Table 2 Details of telehealth studies.

Three main types of telehealth were identified: videoconferencing (n = 5), home-based self-monitoring (n = 7) and remote NIV monitoring (n = 4). Videoconferencing is any consultation between a patient/caregiver and a healthcare professional through real-time video. Home-based self-monitoring is the process in which patients (and their caregivers) manually perform measurements at home, and transmit data to the medical team and receive medical support via digital technology. Remote NIV monitoring is the process whereby a patient’s digital NIV data are monitored remotely and transmitted to the medical team. One of the studies used the store and forward method in addition to videoconferencing. The store and forward method includes recording a patient assessment at home, after which the recording is stored and forwarded to the medical team for further assessment. The determinants of implementation per study can be found in and an overview of all identified barriers and facilitators telehealth use/implementation is presented in .

Table 3 Determinants of implementation categorized according to the CFIR domains.

Table 4 The barriers to and facilitators of telehealth use/implementation in ALS care.

Videoconferencing (n = 5)

Innovation characteristics

Core components

Studies reported that videoconferences were attended either by multiple healthcare professionals (Citation10,Citation11) or by one physician (Citation12,Citation13). In another study, during a home visit, a nurse set-up a videoconference for the patient and caregiver with the clinical director (Citation14). A few studies required patients to login on the webserver with a personal ID code (Citation10,Citation12,Citation13).

Complexity

One study reported issues with video and audio, but did not prevent any videoconferences from taking place (Citation13). Audio issues were solved by using a phone and a pager was used to troubleshoot technical issues. In one study, there were issues with buffering large video files, and an unstable and unreliable internet connection (Citation14).

Patient/caregiver characteristics

User-experiences and benefits

Three studies reported that patients were satisfied with videoconferencing (Citation12–14). One study reported that satisfaction with telehealth was not related to disease severity or travel distance (Citation14). Reported benefits of patients included reduced travel burden, reduced clinical burden and time-saving (Citation12,Citation13). Remote consultation increased the continuity of care (Citation11,Citation13) and allowed more severely disabled patients to continue receiving specialist care (Citation13). Caregivers reported a lack of physical evaluation by a healthcare professional (Citation10).

Compliance

Several studies reported that patients felt comfortable and liked working with technology (Citation10,Citation12,Citation14), which determined enthusiasm with telehealth (Citation14). According to two studies, patients were willing to discuss most practical topics via remote consultation (e.g. medication, equipment, research, symptoms, and treatments) (Citation12,Citation13). However, one of these studies indicated reluctance of patients to discuss sensitive topics, such as acceptance/coping and end-of-life, during a remote consultation (Citation12). These topics would require a face-to-face consultation. Patients were assisted by caregivers in order to use videoconferencing in some studies (Citation10,Citation12,Citation13).

Healthcare professional characteristics

User-experiences and benefits

One study showed that healthcare professionals were generally satisfied with the communication and provision of care during videoconferences (Citation10). In addition, videoconferencing enabled a local therapist to attend the consultations, which normally was not possible with in-clinic care (Citation12). The healthcare professionals in two studies were able to discuss most, but not all, topics (as reported by patients) through videoconferencing (Citation12,Citation13). Despite these positive experiences, several studies indicated the lack of a sense of touch perceived by healthcare professionals (Citation10,Citation13,Citation14) and one study reported that healthcare professionals might be uncertain about whether videoconferencing allows for an appropriate medical assessment (Citation13). Additionally, in one study, healthcare professionals expressed dissatisfaction with the quality of the video and audio, and reported that telehealth was not equal to in-person care (Citation10). One study reported mixed opinions on time requirement and ease of the process of the store and forward method (Citation14).

The inner and outer setting

Available resources

Studies showed that the care protocol for videoconferences was the same as for in-clinic care, including equal staff requirement during consultations (Citation10,Citation11). In a couple of studies, training of healthcare professionals and patients was required for using videoconferencing (Citation12–14). Technical support for healthcare professionals in two studies was provided by an external information technology organization (Citation12) or the internal telehealth division (Citation13).

Finance and legislation

One study reported a lack of reimbursement for telehealth (Citation13).

Home-based self-monitoring (n = 7)

Innovation characteristics

Core components

Studies included the at-home assessment of oximetry (Citation15–20), questions on functional status and symptoms (Citation15,Citation20,Citation21), manually or mechanically assisted coughing, airway suctioning and mechanical in-exsufflation (MI-E) (Citation16), peak cough expiration flow, respiratory discomfort and a clinical diary on changes in clinical condition (Citation19), and body weight and balance (Citation21). Some studies used a monitoring protocol with daily assessments (Citation17–19), while a number of other studies applied a weekly or bi-weekly monitoring protocol (Citation15,Citation20,Citation21). Self-monitored data was transmitted either through telephone or a tablet device (Citation15–21).

Complexity

One study reported that self-monitoring seemed to be too cumbersome due to the large number of daily assessments and complexity of reporting (Citation19). In contrast, adhering to the self-monitoring protocol in other studies was considered to be easy, due to an appropriate frequency of monitoring and user-friendly technology (Citation15,Citation21). Specifically oximeters and tablet devices were reported to be user-friendly (Citation17,Citation20,Citation21). In some cases, the self-monitoring protocol was reinforced by home visits (Citation17) or telephone calls (Citation17,Citation21).

Patient characteristics

User-experiences and benefits

Satisfaction with telehealth was reported in three studies (Citation15,Citation17,Citation21). Patients reported increased awareness of the disease (Citation15,Citation21), more confidence in dealing with the disease (Citation17) and an increased feeling of security for home management of respiratory symptoms (Citation16). A reduction in hospital admissions was seen in one study (Citation16) and in another study, the number of unnecessary clinic visits was reduced, resulting in a saving in time and costs (Citation15).

Compliance

In several studies, patients were assisted by a caregiver when they were too impaired (Citation16–18,Citation21). Patients reported in two studies that devices worked well and were easy to use (Citation15,Citation17), but patients in another study had difficulty using a tablet device due to upper limb disability (Citation21). One study reported that patients showed low compliance with a monitoring protocol with multiple daily measurements (Citation19). In contrast, two studies reported high adherence with a (bi-)weekly monitoring protocol (Citation15,Citation21). Accordingly, patients and caregivers in these studies reported that self-monitoring was easy, not time-consuming nor tiring.

Healthcare professional characteristics

User-experiences and benefits

It was reported that telehealth allowed healthcare professionals to monitor symptoms effectively, provide timely support (Citation15) and make appropriate decisions in care (Citation21). One study reported that telephone-assisted self-monitoring increased healthcare professionals’ feeling of security for home management of respiratory symptoms (Citation16). A telehealth nurse reported that telehealth was easy to use and not time-consuming (Citation21). However, she also reported that information from self-monitoring was often not detailed enough and that repetitive alerts lead to frustration.

The inner and outer setting

Available resources

Studies reported that medical support could be requested through a telephone-call (Citation15–21), a message system (Citation15,Citation20) or email (Citation21), and that support was provided by either a therapist or a nurse. In one study a telehealth nurse remotely monitored patients through a clinical portal, phoned patients, expedited appointments and liaised the medical team (Citation21). In another study, nurses used a standardized ALS card-of-risk to guide telephonic clinical interviews (Citation18). Nurses in these studies required training for operating the ALS card-of-risk and the clinical portal. Healthcare professionals provided face-to-face training to patients in the process of restoring blood oxygen saturation (Citation16) and in operating a tablet (Citation21).

Finance and legislation

It was reported that on-demand MI-E rental was cost-effective compared to continuous rental and that fewer hospital admissions reduced hospitalization costs (Citation16). Telephone-assistance was believed to be sustainable in terms of cost and staff requirement (Citation17). Reported barriers to the continuation of telehealth use were a lack of information on cost-effectiveness (Citation18) and a lack of reimbursement (Citation16). A large variety of fixed and variable costs related to tele-assistance were seen in two studies (Citation17,Citation18).

Remote NIV monitoring (n = 4)

Innovation characteristics

Core components

Studies reported using an NIV device with bi-directional data transmission, which allowed for automatic transmission of NIV data and remote adjustment of NIV settings (Citation22–25). NIV devices had flexible use of electronic slots, which allowed arrangements to be tailored to patients’ needs (Citation22,Citation24). In two studies, patients had access to a helpline for on-demand medical or technical support; technicians monitored NIV data and flagged the physician to immediately change settings (Citation22,Citation25).

Complexity

Two studies reported that the NIV devices were easy to use and showed robust wireless connection tests for transmission of data and setting changes (Citation22,Citation24). In one study, additional functionalities and aids were provided to facilitate NIV use (Citation24). The speed of data extraction was limited in two studies (Citation22,Citation25).

Patient characteristics

User-experiences and benefits

The main benefit for patients was a reduced need to travel to the clinic for adjustment of NIV settings (Citation22–25). Additionally, fewer hospital admissions were reported (Citation23,Citation25). In one study, patients experienced improved enablement and more confidence in managing the disease (Citation23).

Compliance

The bi-directional and automatic functionality limited the need for manual intervention by patients and caregivers for monitoring. Patients reported that the NIV devices were easy to use, and that settings were easy to change/arrange (Citation22,Citation24). In one study, patients appreciated the extra aids that were provided to facilitate NIV use (Citation24).

Healthcare professional characteristics

User-experiences and benefits

One study reported that remote monitoring facilitated communication with the patient, but that healthcare professionals missed the sense of touch.(10) In all studies, healthcare professionals had the ability to remotely monitor NIV and adjust settings, which would not be possible with usual in-clinic care (Citation22–25).

The inner and outer setting

Available resources

In some studies, on-demand support was provided through a helpline (Citation22,Citation25). A testing phase was required in two studies and (cardio-pulmonology) technicians were hired to monitor NIV data (Citation22,Citation25) and check procedures and mistakes (Citation22). Two studies reported that the number of NIV setting changes was 50% lower over the entire period of NIV use, compared to usual care, hence saving time (Citation22,Citation25).

Finance and legislation

One study reported that a large initial investment is required to set up telehealth and that remote NIV monitoring in ALS care is cost-effective (Citation23). Another study reported that the number of hospital admissions was reduced, which resulted in lower hospitalization costs (Citation25). Reported barriers to telehealth implementation were a lack of robust cost-effectiveness-analysis (Citation22,Citation24) and issues with reimbursement (Citation22).

Discussion

This review identified three different types of telehealth used in ALS care and showed that telehealth was mainly targeted at patients with respiratory impairment. Furthermore, we found that the barriers and facilitators of telehealth implementation in ALS care were consistent with the determinants identified in other healthcare settings. The main barriers hindering implementation of telehealth in ALS care were related to issues with finance and legislation, and lack of personal contact perceived by healthcare professionals.

It was noticeable in this review that the proportion of patients who were ventilated through NIV or TIV (68%) was much higher compared to the general ALS population (18–36%) (Citation26,Citation27). In addition, 10 of 11 remote monitoring studies focused primarily on respiratory function, such as oximetry, (assisted) coughing, respiratory symptoms, and NIV. These findings demonstrate that patients in the included studies are not representative of a general ALS population and that telehealth is focused on respiratory function up until now.

Determinants of implementation

Our results indicate that patients with ALS (and their caregivers) have a positive attitude toward the use of telehealth. This may be attributed to patients’ perceived benefits of telehealth (e.g. an increased feeling of enablement, reduced travel and clinical burden) and good compliance to telehealth use (i.e. easy to use devices, comfort with using technology and caregiver assistance). A positive attitude of patients/caregivers is a facilitator for implementation as it increases acceptance of telehealth and positively influences the attitude of healthcare professionals (Citation28,Citation29). It should be noted that several studies recruited a convenience sample of patients, who were likely to benefit from telehealth, or liked working with technology. This may have affected patients’ experiences. Results suggest that healthcare professionals in ALS care have a more negative attitude toward telehealth. Despite being positive about communication through telehealth, healthcare professionals mostly reported barriers, such as technical issues, a lack of physical evaluation/contact and issues with a comprehensive medical assessment. A negative attitude among healthcare professionals creates resistance to telehealth and is a known barrier to implementation (Citation28,Citation29). Regrettably, more than half of the studies did not evaluate user-experiences of healthcare professionals and therefore lack this information. Two important facilitators in this review that positively influenced the attitude of end-users were the provision of training and ongoing support. Despite requiring more staff time, the provision of training and ongoing support ensures that end-users are able to apply technology properly, which is essential for a successful implementation (Citation28,Citation29). One of the main barriers to implementation of telehealth in ALS care was issues related to finance and legislation. Studies mostly reported a lack of robust cost-effectiveness analyses and a lack of reimbursement for telehealth. These are important issues that are also known in other healthcare settings, and hinder the implementation and integration of telehealth in ALS care. There was, however, evidence to support that on-demand MI-E rental and remote NIV monitoring were cost-effective, primarily due to a lower number of emergency room visits and hospital admissions. This financial benefit of telehealth is a facilitator for implementation and should be investigated in future research.

Clinical implications

Current telehealth innovations are mainly targeted at a subgroup of patients with ALS, which means that a substantial portion of the ALS population does not benefit from them. Ideally, all patients with ALS should be able to benefit from the use of telehealth, irrespective of the disease stage or type of impairments. Recent evidence has shown that this is feasible and of benefit for patients with motor neuron disease (Citation21). For this reason, future innovations should remotely monitor all relevant domains of functioning from early on in the disease. This will help healthcare professionals with (a) detecting early signs and symptoms, (b) informing patients about changes in all aspects of the disease and (c) providing timely care and information. Additionally, if started in an early disease stage, patients will be able to receive training and become familiar with technology and remote monitoring before becoming severely impaired.

To make sure a telehealth innovation truly meets the needs of end-users, both patients and healthcare professionals should be involved throughout the development process (Citation21,Citation30). The involvement of end-users will promote a positive attitude toward telehealth and increase acceptance, thus facilitating implementation (Citation28,Citation29). Furthermore, telehealth innovations should be personalized, as the rate of disease progression is highly variable and the care needs of patients with ALS are ever-changing. The personalization of telehealth promotes patient engagement (Citation31) and involves the tailoring of monitoring frequency, clinic visit scheduling and the provision of care and information. To further increase patient engagement with remote monitoring, notifications and personal feedback could be provided (Citation31).

To improve remote monitoring and the usability of monitoring-data for research purposes, standardized outcome measures should be established and patients should be involved in determining which measures are relevant. Ideally, outcome measures should be associated with disease progression and survival, as this will help with the timely provision of interventions, assistive devices, and information. Examples of such outcome measures are the ALSFRS-R, weight loss and vital capacity (Citation32–34). Also, assessments on cognition, quality of life and caregiver burden could be included to facilitate psychological support.

Future research

In order to improve the implementation of telehealth in ALS care, future studies should be aimed at identifying the determinants of implementation and investigating how they affect the success of telehealth. Improved reporting (on determinants) will help to create a more detailed overview of relevant determinants, which is essential to guide healthcare professionals in the implementation of future telehealth innovations in ALS care. Furthermore, future research should focus on investigating the cost-effectiveness. Robust analyses will specifically facilitate the use of telehealth beyond the initial pilot phase.

Limitations

The main limitation of this review is that there were no studies primarily aimed at identifying the determinants of implementation. As a result, positive and negative aspects of telehealth might not have been reported or were not specifically reported as barriers or facilitators of telehealth implementation. For this reason, we may have missed a number of potential barriers, such as issues with (national) policy and incompatibility with the current infrastructure. Another limitation is that a number of studies included a convenience sample, which may have resulted in biased patients’ experiences.

Conclusion

Our findings show that telehealth in ALS care is well-received by patients and their caregivers, as a result of user-friendly technology and experienced benefits. The provision of training and ongoing support to end-users has shown to be key for a successful telehealth implementation. Issues with reimbursement of telehealth and lacking information on cost-effectiveness were the main challenges. Future research should specifically focus on reporting barriers and facilitators to guide future telehealth implementation and help design new implementation strategies.

Declaration of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest and that the current study is their own work.

Supplementary_material_1_-_PubMed_search__6_Nov_2019_.docx

Download MS Word (15.9 KB)Additional information

Funding

References

- Chiò A, PARALS, Bottacchi E, Buffa C, Mutani R, Mora G. Positive effects of tertiary centres for amyotrophic lateral sclerosis on outcome and use of hospital facilities. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2006;77:948–50.

- Van den Berg JP, Kalmijn S, Lindeman E, Veldink JH, de Visser M, Van der Graaff MM, et al. Multidisciplinary ALS care improves quality of life in patients with ALS. Neurology 2005;65:1264–7.

- Ng L, Khan F, Mathers S. Multidisciplinary care for adults with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis or motor neuron disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;(4):CD007425.

- Rooney J, Byrne S, Heverin M, Tobin K, Dick A, Donaghy C, et al. A multidisciplinary clinic approach improves survival in ALS: a comparative study of ALS in Ireland and Northern Ireland. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2015;86:496–501.

- Aridegbe T, Kandler R, Walters SJ, Walsh T, Shaw PJ, McDermott CJ. The natural history of motor neuron disease: assessing the impact of specialist care. Amyotroph Lateral Scler Frontotemporal Degener. 2013;14:13–9.

- Schellenberg KL, Hansen G. Patient perspectives on transitioning to amyotrophic lateral sclerosis multidisciplinary clinics. J Multidiscip Healthc. 2018;11:519–24.

- Stephens HE, Young J, Felgoise SH, Simmons Z. A qualitative study of multidisciplinary ALS clinic use in the United States. Amyotroph Lateral Scler Frontotemporal Degener. 2016;17:55–61.

- Hobson EV, Baird WO, Cooper CL, Mawson S, Shaw PJ, Mcdermott CJ. Using technology to improve access to specialist care in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: a systematic review. Amyotroph Lateral Scler Frontotemporal Degener. 2016;17:313–24.

- Damschroder LJ, Aron DC, Keith RE, Kirsh SR, Alexander JA, Lowery JC. Fostering implementation of health services research findings into practice: a consolidated framework for advancing implementation science. Implementation Sci. 2009;4:50.

- Geronimo A, Wright C, Morris A, Walsh S, Snyder B, Simmons Z. Incorporation of telehealth into a multidisciplinary ALS Clinic: feasibility and acceptability. Amyotroph Lateral Scler Frontotemporal Degener. 2017;18:555–61.

- Selkirk SM, Washington MO, McClellan F, Flynn B, Seton JM, Strozewski R. Delivering tertiary centre specialty care to ALS patients via telemedicine: a retrospective cohort analysis. Amyotroph Lateral Scler Frontotemporal Degener. 2017;18:324–32.

- Nijeweme-d’Hollosy W, Janssen E, Huis in ’t Veld R, Spoelstra J, Vollenbroek-Hutten M, Hermens H. Tele-treatment of patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS). J Telemed Telecare. 2006;12: 31–4. Available at: http://www.embase.com/search/results?subaction=viewrecord&from=export&id=L44995837%0Ahttp://limo.libis.be/resolver?&sid=EMBASE&issn=1357633X&id=.

- Van De Rijn M, Paganoni S, Levine-Weinberg M, Campbell K, Swartz Ellrodt A, Estrada J, et al. Experience with telemedicine in a multi-disciplinary ALS clinic. Amyotroph Lateral Scler Frontotemporal Degener. 2018;19:143–8.

- Pulley MT, Brittain R, Hodges W, et al. Multidisciplinary amyotrophic lateral sclerosis telemedicine care: the store and forward method. Muscle Nerve 2019;59:34–39.

- Ando H, Ashcroft-Kelso H, Halhead R, Chakrabarti B, Young CA, Cousins R, et al. Experience of telehealth in people with motor neurone disease using noninvasive ventilation. Disabil Rehabil Assist Technol. 2019 Sep 12:1-7 [Epub ahead of print].

- Vitacca M, Paneroni M, Trainini D, Bianchi L, Assoni G, Saleri M, et al. At home and on demand mechanical cough assistance program for patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2010;89:401–6.

- Vitacca M, Comini L, Tentorio M, Assoni G, Trainini D, Fiorenza D, et al. A pilot trial of telemedicine-assisted, integrated care for patients with advanced amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and their caregivers. J Telemed Telecare. 2010;16:83–8.

- Vitacca M, Comini L, Assoni G, Fiorenza D, Gilè S, Bernocchi P, et al. Tele-assistance in patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: long term activity and costs. Disabil Rehabil Assist Technol. 2012;7:494–500.

- Paneroni M, Trainini D, Winck JC, Vitacca M. Pilot study for home monitoring of cough capacity in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: a case series. Rev Port Pneumol. 2014;20:181–7.

- Ando H, Ashcroft-Kelso H, Halhead R, Young CA, Chakrabarti B, Levene P, et al. Incorporating self-reported questions for telemonitoring to optimize care of patients with MND on noninvasive ventilation (MND OptNIVent). Amyotroph Lateral Scler Frontotemporal Degener. 2019;20:336–47.

- Hobson E, Baird W, Bradburn M, Cooper C, Mawson S, Quinn A, et al. Process evaluation and exploration of telehealth in motor neuron disease in a UK specialist centre. BMJ Open. 2019;9:e028526.

- de Almeida JPL, Pinto AC, Pereira J, Pinto S, de Carvalho M. Implementation of a wireless device for real-time telemedical assistance of home-ventilated amyotrophic lateral sclerosis patients: a feasibility study. Telemed e-Health. 2010;16:883–8.

- de Almeida JPL, Pinto A, Pinto S, Ohana B, De Carvalho M. Economic cost of home-telemonitoring care for BiPAP-assisted ALS individuals. Amyotroph Lateral Scler. 2012;13:533–7.

- Tura A, Santini P, Longo D, Quareni L. A telemedicine instrument for home monitoring of patients with chronic respiratory diseases. Ann Ist Super Sanita. 2007;43:101–9.

- Pinto A, Almeida JP, Pinto S, Pereira J, Oliveira AG, De Carvalho M. Home telemonitoring of non-invasive ventilation decreases healthcare utilisation in a prospective controlled trial of patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2010;81:1238–42.

- Lechtzin N, the ALS CARE Study Group, Wiener CM, Clawson L, Davidson MC, Anderson F, Gowda N, et al. Use of noninvasive ventilation in patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Amyotroph Lateral Scler Other Mot Neuron Disord. 2004;5:9–15.

- Boylan K, For the ALS Center Cost Evaluation W/Standards & Satisfaction (Access) Consortium, Levine T, Lomen-Hoerth C, Lyon M, Maginnis K, Callas P, et al. Prospective study of cost of care at multidisciplinary ALS centers adhering to American Academy of Neurology (AAN) ALS practice parameters. Amyotroph Lateral Scler Frontotemporal Degener. 2016;17:119–27.

- Broens THF, Huis in’t Veld RMHA, Vollenbroek-Hutten MMR, Hermens HJ, van Halteren AT, Nieuwenhuis LJM. Determinants of successful telemedicine implementations: a literature study. J Telemed Telecare. 2007;13:303–9.

- Ross J, Stevenson F, Lau R, Murray E. Factors that influence the implementation of e-health: a systematic review of systematic reviews (an update). Implement Sci 2016;11:146.

- Dabbs ADV, Myers BA, Mc Curry KR, Dunbar-Jacob J, Hawkins RP, Begey A, et al. User-centered design and interactive health technologies for patientsi. Comput Inform Nurs. 2009;27:175–83.

- Simblett S, Greer B, Matcham F, Curtis H, Polhemus A, Ferrão J, et al. Barriers to and facilitators of engagement with remote measurement technology for managing health: systematic review and content analysis of findings. J Med Internet Res. 2018;20:e10480.

- Kaufmann P, Levy G, Thompson JLP, DelBene ML, Battista V, Gordon PH, et al. The ALSFRSr predicts survival time in an ALS clinic population. Neurology 2005;64:38–43.

- Peter RS, Rosenbohm A, Dupuis L, Brehme T, Kassubek J, Rothenbacher D, et al. Life course body mass index and risk and prognosis of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: results from the ALS registry Swabia. Eur J Epidemiol. 2017;32:901–8.

- Baumann F, Henderson RD, Morrison SC, Brown M, Hutchinson N, Douglas JA, et al. Use of respiratory function tests to predict survival in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Amyotroph Lateral Scler. 2010;11:194–202.