Abstract

We previously reported on a series of patients diagnosed with ALS whom had an extraordinary course defined by substantial and sustained improvement in weakness and function. For this study, twenty-five of these “ALS Reversals” completed extensive environmental exposure questionnaires. These responses were then compared to a large database of prior responses from patients with typically progressive ALS (n = 6187). The results demonstrated that the “Reversal” participants have had a diverse number of exposures with substantial heterogeneity. In general, this was similar to the control group; however, there were a few specific differences that could be further explored in future research.

Introduction

Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) is a motor neuron disease characterized by widespread and progressive death of both upper and lower motor neurons (Citation1). We previously published a series of patients who met diagnostic criteria for ALS, that subsequently demonstrated a substantial and sustained clinical improvement over time (Citation2) which is inconsistent with the natural history of ALS (Citation3). As of this study, we have identified 46 cases of “ALS Reversals” (Citation2,Citation4).

It has been previously reported that ALS is associated with various environmental toxins (Citation5,Citation6). We hypothesize that these “Reversals” may have had a time-limited environmental exposure that triggered an ALS-like disease, with motor neuron death stopping after the exposure ended. Alternately, there may have been an exposure with a priming effect that facilitated a milder, recoverable form of ALS. In order to study this, we recruited patients with validated “Reversals” (Citation2,Citation4) to complete exposure questionnaires.

Methods

This was a prospective case-control study comparing environmental exposures for a previously defined group of “ALS Reversals” (Citation2) with typically progressive patients with ALS, i.e. “typical ALS” (control group). Criteria for participation by the “ALS Reversal” participants included prior documentation by our study team as an “ALS Reversal”, English language speaking, and having capacity to consent to research. To assess exposures, we used the United States Centers for Disease Control’s National ALS Registry. This is a 17-part electronic self-report survey (Citation7,Citation8) that attempts to enroll all patients diagnosed with ALS that reside in the U.S. Questions span topics including demographics, employment history, military service, alcohol, tobacco, physical activity, occupational exposures, home exposures, hobby exposures, caffeine, head and neck injuries, and electrical shocks.

Enrolled “Reversal” participants took the surveys on the CDC’s website (Citation8), on paper, in person, or over the telephone. If the survey was not completed on the CDC’s website due to participant preference, the study team entered the responses on CDC website on the participant’s behalf. Following study participant activities, the data was compared with a dataset from 6187 prior survey respondents with “typical ALS.” This control dataset represents all registered users from October 19, 2010 to December 31, 2016 except duplicate accounts and users that only completed demographics. The stated “n” for each statistic is the number of respondents excluding those responding as “not sure.” For some exposures, participants reported the amount they were exposed to various substances or activities allowing calculation of an estimated lifetime quantitative exposure (i.e. total discrete exposures or total time exposed).

Statistical analysis was performed using both Microsoft Excel and JMP Pro 15 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC). Due to the small sample size of the "Reversals” group, we used the Haldane-Anscombe correction for odds ratios. Tests of association were performed with the two-sample Welch t-test, Fisher’s Exact Test, and linear regression. Figures were made with Prism 9 (GraphPad Software Inc., San Diego, CA). This research study protocol was approved by the Duke University Health System institutional review board (Pro00100219). This study is registered with ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT03706391).

Results

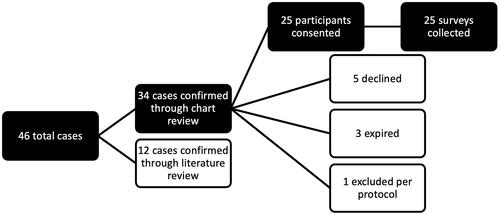

For this study, 46 cases of “ALS Reversals” were evaluated for inclusion in this study. Twelve of these cases were published cases for which the authors were uncontactable or the authors had lost contact with the patient. Of the remaining 34 cases, twenty-five consented to participate in this study ().

Figure 1 Recruitment and enrollment into StAR4.

This figure displays enrollment of the “ALS Reversals” group participants. We had previously attempted to contact the authors of the cases identified in the literature but the authors were either non-contactable or the case in question was lost to follow-up. The individual excluded per protocol did not speak English to the extent necessary to complete this survey accurately.

Demographics

For “Reversal” participants, there was an average 10.5 years (SD = 9.8) from ALS diagnosis to when this study was completed. When compared with the typical ALS group (), the odds of being male in the “ALS Reversal” group were slightly higher (not significant) and the “ALS Reversals” were 5.2 years younger on average at age of diagnosis which approached statistical significance (t = –2.04, p = 0.052). The odds of having a sibling with ALS were similar. These findings are consistent with our previously published data (Citation2).

Table 1 Demographics.

Exercise and BMI

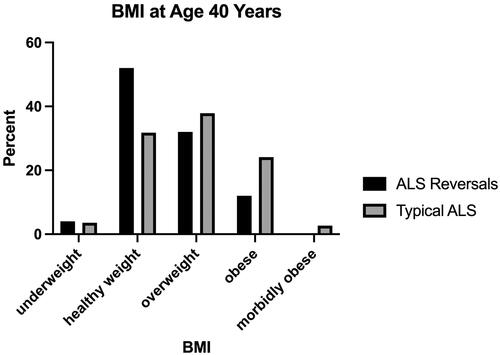

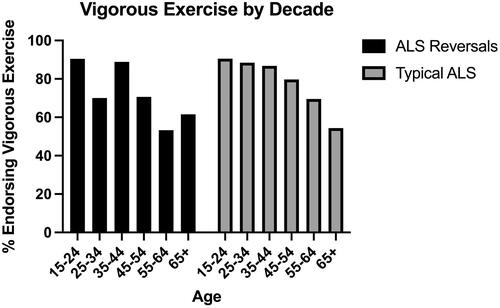

Participants reported frequency of vigorous exercise during each decade of life () defined as “leisure-time physical activity for at least 10 minutes that caused heavy sweating or large increases in breathing or heart rate.” In the “ALS Reversals” group, 84% (21/25) endorsed having ever engaged in vigorous exercise which was not significantly different (OR 0.84, 95% CI 0.3–2.33) from the control group (4895/5756). The mean body mass index (BMI; from self-reported height and weight) at time of survey was 25.6 for the “Reversal” participants (SD = 4.4, n = 25) which was minimally different from typical ALS participants (x̄ = 26.9, SD = 5.5, n = 6151). Similar results were found for BMI at age 40 years ().

Figure 2 Vigorous exercise by decade.

This figure depicts the percent of participants endorsing engaging in vigorous exercise during different decades of life. The small n of the “ALS Reversals” group limits interpretation, but the overall response appears similar visually. There does not appear to be substantial difference between comparison groups.

Caffeine consumption

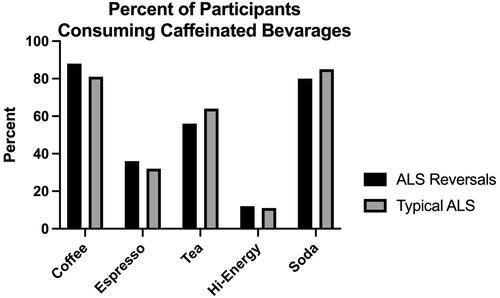

Participants were asked about caffeinated beverage consumption. The “Reversal” group participants (entire group) reported an average of 43,859 (SD = 29,132, n = 21) caffeinated drinks compared to the typical ALS group average of 48,168 caffeinated drinks (SD = 41,567, n = 1330). Analysis with linear regression found that there were no significant group differences when controlling for current age (p = 0.410). Due to variable caffeine content in drinks (Citation9), this is not an accurate estimation of actual caffeine intake. demonstrates no obvious differences in likelihood to consume different caffeinated beverage types. Additional quantitative analyses of lifetime dosage showed no significant group differences in consumption of either tea, coffee, naturally caffeinated beverages or high caffeine beverages (data not shown).

Tobacco use

Of the “ALS Reversal” group, 36% (9/25) identified as ever being someone whom regularly smoked (daily for minimum 6 months) versus 49% of the typical ALS group (n = 3032/6179) with similar odds (OR = 0.60, 95% CI 0.27 to 1.33). Among participants with a smoking history, the average pack-years (a measure of lifetime consumption) was 26.9 (SD = 37.9, n = 9) in the “ALS Reversal” group compared with 21.0 pack-years (SD = 19.9, n = 2999) in the control group which was not a significant age-corrected difference (p = 0.503). All “Reversal” participants with a history of smoking had quit, while only 83% of the control group whom had smoked (n = 2512/3025) had quit. This did not meet statistical significance (OR 3.88, 95% CI 0.23 to 66.83).

Alcohol consumption

Participants were also asked about alcoholic beverage consumption in terms of number of drinks. The survey did not ask for details about types of alcoholic beverages or state what qualifies as a single drink. A total of 72% (18/25) of the “ALS Reversal” group reported drinking alcoholic beverages compared with 80% of the typical ALS group (4938/6164) which was not a significant difference (OR 0.61, 95% CI 0.26 to 1.43). The mean lifetime number of alcoholic beverages (averaged over drinkers and non-drinkers) was 14,746 (SD 20,787, n = 24) in the “ALS Reversal” group. There was not a significant age-corrected difference (p = 0.526) compared with the typical ALS group’s average of 10,877 lifetime drinks (SD = 19,759, n = 5984).

Military service

Within the “ALS Reversal” group, 16% (4/25) reported being a veteran; none of these veterans were deployed. The odds of being a veteran were similar to the 22% of the typical ALS group (1367/6170) that reported being a veteran (OR 0.74 95% CI 0.27–2.03). Of the typical ALS group, 32% of veterans (431/1363) were deployed which was not clearly different from the “Reversal” group (OR 0.24 95% CI 0.01 to 4.47).

Occupational exposures

Participants were asked to report their longest job title and what industry that their job was within ( and ). There was a tendency for jobs traditionally associated with higher socioeconomic status to have disproportionally greater representation in the “Reversals” group. Of the “ALS Reversals” group, 42% endorsed holding a job as a company executive or owner or holding a professional position such as in healthcare, engineering or legal sectors. Only 17% of the typical ALS progression group endorsed these jobs. Responses about longest industry reproduced this difference (). There were several specific jobs that were more common in the “ALS Reversals” group than the control group () such as carpenter or cabinet maker” and “janitor, maintenance worker or housecleaner” which led to large odds ratios but is of unclear significance. When asked about specific occupational exposures (), there were no significant differences in odds of being exposed to an exposure. Among exposed participants, exposure time was generally similar except for "glue and adhesives" for which “Reversal” participants reported twice the number of years of exposure which met statistical significance ().

Table 2 Longest held job.

Table 3 Longest NAICS industry.

Table 4 Occupational exposures.

Home exposures

Participants were asked about hobby and recreational exposures () and household chemical exposures (). There did not appear to be differences between groups in the frequency of reporting any hobby or recreational exposure. However, there were some differences in the exposure dosage among those exposed; “ALS Reversals” had significantly fewer hours of exposure to leather work, oil-based paint, and photograph development. There was also a numerically large difference in the number of hours spent woodworking (the "Reversal” group reported almost five-fold more hours than the control group), but this did not reach statistical significance.

Table 5 Hobby & recreational exposures.

Table 6 Home exposures.

Head & neck injuries and electrical shocks

Among the “Reversals” group, 68% (17/25) reported having a history of a head or neck injury of any etiology, 40% (10/25) had such an injury due to a motor vehicle accident or all-terrain vehicle (ATV) injury, 48% due to a sporting or recreation accident (12/25), 4% (1/24) due to assault and 8% (2/25) due to an explosion or blast. The odds of a head or neck injury of any etiology was similar (OR 1.58, 95% CI 0.69 to 3.62) compared to the control group (748/1323; 57%). Two “Reversal” participants (8%; 2/25) reported severe injury features (i.e. seizure, amnesia, or skull fracture) which was similar odds (OR 2.22, 95% CI 0.59 to 8.37) compared to the control group (5%; 62/1364). Within the “Reversal” group, 24% (6/25) reported having been exposed to an electrical shock which approximated the odds in the (OR 1.41, 95% CI 0.57 to 3.47) typical ALS group (19%, 230/1206).

Discussion

This study investigated a number of environmental exposures of persons with ALS that had a substantial and sustained recovery (Citation2). The main conclusion from this data is that the “Reversal” participants have been exposed to a diversity of environmental factors. There was no specific environmental factor that appeared to predict a participant of the “ALS Reversal” group. It has been suggested that the development of ALS is a lifetime process that is multifactorial and includes genetic and environmental factors (Citation11) and may be due to heterogenous etiologies (Citation12). This study is particularly limited in detecting multifactorial effects or etiologic heterogeneity due to the obligatorily small sample size of “ALS Reversal” cases which limits the statistical power substantially.

One interesting association was the higher odds of the “Reversal” participants to endorse the occupation “carpenter or cabinet maker” (). Similar proportions of both groups engaged in hobby “woodworking” but the “Reversal” participants reported almost five-fold as many hours exposed (). These results leave open the possibility that there may be some part of woodworking exposure associated with the likelihood of an “Reversal.” Due to the diversity of responses in this study and high number of statistical comparisons in this study, these results should be considered hypothesis-generating only and may be due to chance.

There are several limitations of this exploratory study. Firstly, any exposure with predictive value for the “Reversal” group may represent recall bias in the setting of an extraordinary course of clinically diagnosed ALS. Secondly, we did not investigate the temporal relationship between the exposure and ALS symptom onset which may be important (Citation13). Finally, this study consists of a lengthy linearly administered survey. There was a clear decrease in response rate for the control group which did not occur for the “Reversal” participants (data not shown). This is likely because the “Reversal” group was highly motivated and received reminders. It is possible that this affected the results of the later surveys.

In conclusion, “ALS Reversal” cases have had heterogenous environmental exposures with more similarities than differences when compared with patients with typically progressive ALS. We are currently analyzing genomic data from “ALS Reversal” cases in order to elucidate possible genetic correlates (Citation14). Ultimately, we hope to obtain biomarker and neuropathologic data to help delineate the pathologic basis of these extraordinary cases of substantial and sustained reversal of clinically diagnosed ALS disease.

Declaration of interest

Richard Bedlack has research support from ALSA, Orion, MediciNova, and the Healey Center, and consulting support from AB Science, Alexion, ALSA, Amylyx, Apellis, Biogen, Brainstorm Cell, Clene, Corcept, Cytokinetics, GenieUs, Guidepoint, ITF Pharma, Mallinkrodt, New Biotic, Orphazyme, Shineki and Woolsey Pharma. The authors have no other conflicts of interest to report.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Ludolph A, Drory V, Hardiman O, Nakano I, Ravits J, Robberecht W, et al. A revision of the El Escorial criteria – 2015. Amyotroph Lateral Scler Frontotemporal Degener. 2015;16:291–2.

- Harrison D, Mehta P, van Es MA, Stommel E, Drory VE, Nefussy B, et al. “ALS reversals”: demographics, disease characteristics, treatments, and co-morbidities. Amyotroph Lateral Scler Frontotemporal Degener. 2018;19:495–9.

- Bedlack RS, Vaughan T, Wicks P, Heywood J, Sinani E, Selsov R, et al. How common are ALS plateaus and reversals? Neurology 2016;86:808–12.

- Bedlack RS. Unpublished Data. 2021.

- Su F-C, Goutman SA, Chernyak S, Mukherjee B, Callaghan BC, Batterman S, et al. Association of environmental toxins with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. JAMA Neurol. 2016;73:803–11.

- Oskarsson B, Horton DK, Mitsumoto H. Potential environmental factors in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Neurol Clin. 2015;33:877–88.

- 110th Congress. An act to amend the public health service act to provide for the establishment of an amyotrophic lateral sclerosis registry; 2008:4047–4050. Available at: https://wwwn.cdc.gov/als/Download/ALSRegistryAct(PublicLaw110-373).pdf

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National ALS Registry. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/als/

- Center for Science in the Public Interest. Caffeine Chart. Published 2021. Available at: https://cspinet.org/eating-healthy/ingredients-of-concern/caffeine-chart. Accessed April 5, 2021.

- United States Census Bureau. North American Industry Classification System. Published 2021. Available at: https://www.census.gov/naics/. Accessed October 2, 2021.

- Al-Chalabi A, Hardiman O. The epidemiology of ALS: a conspiracy of genes, environment and time. Nat Rev Neurol. 2013;9:617–28.

- Grad LI, Rouleau GA, Ravits J, Cashman NR. Clinical Spectrum of Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS). Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2017;7:a024117.

- Bradley WG, Andrew AS, Traynor BJ, Chiò A, Butt TH, Stommel EW. Gene-environment-time interactions in neurodegenerative diseases: hypotheses and research approaches. Ann Neurosci. 2018;25:261–7.

- Study of ALS Reversals 2: Genetic Analyses (StAR2). Available at: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03464903