Abstract

Objectives: To explore users’ experiences of a tailored, interactive web application that supports behaviour change in stress management and to identify if and in that case what in the web-based programme that needed further development or adjustment to be feasible in a randomised controlled trial.

Method: The design of this study was explorative with a qualitative approach. Nine individuals were recruited among the staff at a university. Semi-structured individual interviews were conducted and analysed using qualitative content analysis, after the participants had completed the web-based stress management programme.

Results: One theme was identified, Struggling with what I need when stress management is about me, describing the paradox in having a programme that is perceived as supporting stress management while also being perceived as extensive and time consuming. The theme was divided in two categories: Defining the needs, where the users expressed what they needed from the programme and their everyday environment, to be able to use the programme, and It is about me, where the programme was described as helping the users understand their own stress.

Conclusion: The participants expressed acceptance of using a web-based programme for stress related problems. The perceived extensiveness of the programme must be considered in further development.

Introduction

Digitalisation is a prominent field in the health care sector of many countries [Citation1]. Several interventions that were earlier carried out as face-to-face options have now been translated into web-based formats [Citation2–4]. Web-based interventions have been shown to be effective when it comes to easing different health-related problems, but the dropout rates are often high. On average, studies show a dropout rate of 50% [Citation5]. Many interventions aim at lifestyle-related issues, such as physical activity [Citation4,Citation6] and healthy eating [Citation7], but interventions for mental health are also common [Citation8,Citation9]. However, programmes for mental health promotion and mental illness prevention are scarce.

In Europe, 25% of the working population is at the risk of developing stress-related health problems [Citation10]. Perceived stress is a common reason for sick leave [Citation11]. Stress is also related to several health-related consequences, and contributes to cardiovascular diseases [Citation12], depression [Citation13], sleep disturbances [Citation14], immunocompromising [Citation15,Citation16] and musculoskeletal pain [Citation17], which, by themselves, can lead to sick leave. Concerning the origin of stress-related ill health, distinction between the stress derived from work and that stemming from private life is not clear – both being included in the sick leave numbers caused by stress.

Considering the today’s challenge of stress being a common reason for sick leave [Citation11], there is an urgent need to decrease the frequency of stress-related sick leaves in the workforce. A web-based programme that identifies heightened stress levels and educates users on how to handle stress on an individual level before it leads to sick leave could contribute to decreasing stress levels in the working population. If individuals can identify their own high stress levels early on, learn about stress and the associated health risks with long-term stress, the importance of recovery, and are given tools for handling periods and situations with high stress, their suffering from health-related consequences due to stress may be prevented. Earlier programmes supporting stress management have shown positive effect on perceived stress among different target groups [Citation8,Citation18–23]. In addition, a meta-analysis showed a medium-to-large effect size on perceived stress [Citation24]. Earlier programmes were often based on one or a few stress management techniques and are thus difficult to tailor to the users’ specific needs for stress management. Further, adherence is often low in web-based programmes [Citation5,Citation25], which could be due to the lack of key elements, such as tailoring and interactivity [Citation26,Citation27]. To facilitate adherence and to support behavioural change and stress management with a broader perspective, the web-application My Stress Control (MSC) was developed [Citation28,Citation29]. MSC is a fully automated, tailored, and interactive stress management programme that supports behavioural change in several ways. The programme is built on a theoretical framework using the theories found in earlier effective web-based programmes [Citation30]. The overarching theories are Social Cognitive Theory (SCT) [Citation31] and the Transactional Model of Stress and Coping (TSC) [Citation32,Citation33]. In SCT, the reciprocity of the individual, behaviour and environment is helpful in understanding how behaviours occur, develop and are maintained over the time [Citation31]. The TSC is a framework for evaluating how individuals cope with stressful situations. The central concepts within the model are primary appraisal; how the individual evaluates the situation as potentially harmful, threatening or challenging; secondary appraisal, which includes the person’s ability to alter the situation using available coping strategies, both adaptive and maladaptive; and coping [Citation32,Citation33]. MSC targets both primary and secondary appraisal by providing users with tools to support coping strategies for outcomes of improved or sustained health and well-being. The transtheoretical model and stages of change [Citation34–36] are used for tailoring MSC to each user.

Finally, the theory of reasoned action (TRA) and the theory of planned behaviour (TPB) add the perspective of affecting behavioural intention, attitudes towards performing the behaviour, and perceived control over the behaviour [Citation37]. MSC aims at providing the users with tools to control their own behaviour related to stress reduction. In addition, according to TRA/TPB, how easy or difficult the new behaviour is perceived to be by the individual, determines the individual’s behaviour intention [Citation37]. In MSC, the strategy for learning stress management is divided into basic skills training and applied skills training to successively increase the difficulty by grading the stress management techniques from an easier level of performance to a more complex level.

During the development of MSC, the Behaviour Change Model for Internet Interventions [Citation38] was considered. The model describes factors affecting behavior change by internet interventions. Website use and adherence depends on user characteristics and website characteristics. The degree of support and environmental factors also influences website use and adherence. Behavioural change is attained through various mechanisms included in the programme and possibly leads to symptom improvement, which is sustained through treatment maintenance [Citation38]. Thus, the users are also highly important in the development of a new programme for attaining in-depth knowledge regarding how the programme is perceived. It is also important to study users’ experiences of how the programme targets their specific stress-related problems as well the users’ perception of the acceptability and usability of a new web-based stress management programme.

Thus, the aim of the present study is to explore users’ experiences of using a tailored and interactive web application that supports behavior change in stress management (MSC). The aim was also to identify if, and what, the web-based programme needed further development or adjustment so as to be feasible in a randomised controlled trial (RCT).

Materials and methods

Design

This study had an explorative and qualitative design.

Setting and participants

This study is part of a larger study whose aim is to develop and evaluate a tailored and interactive web-based programme that supports behavioural change in work-related stress. In the overarching project, the web-based self-management programme MSC was developed and tested in a feasibility study [Citation29]. Of the participants in the feasibility study (n = 14), nine consented to take part in the present study.

The feasibility study and present study are both part of a process to further develop MSC and prepare for a RCT to enhance the likelihood for success in a large, more expensive study. The present study participants were recruited from a Swedish university. The inclusion and exclusion criteria was the same as in the feasibility study and the planned RCT. Inclusion criteria were as follows: stress score of 17 or higher [Citation39], measured with the Perceived Stress Scale (PSS-14) [Citation40,Citation41]; employed; 18–65 years old; able to speak and understand the Swedish language; consented to take part in the study; and participated in the feasibility study. The exclusion criteria were currently on sick leave or scoring 11 or more on either of the subscales on HADS [Citation42]. The PSS-14 measures the degree of perceived stress in situations of an individual’s life that are appraised as stressful; higher scores meaning higher perceived stress [Citation40]. Scores above 25 on the PSS-14 have been used as a cut-off score for high stress [Citation39]. The cutoff score of 17 was based on the mean minus one standard deviation in a group in the same study reporting perceived stress on a lower level [Citation39]. The inclusion criterion of a PSS-14 cut-off score of 17 or higher was chosen for the present study to select individuals clearly experiencing stress. The PSS-14 has adequate reliability [Citation41] and validity [Citation40], and the Swedish version has shown good internal consistency and split-half-reliability [Citation43].

Nine women consented to participate in this study. The sample varied in terms of participants’ education level, fixed (e.g. using a stamp watch) versus free working schedule, how much they were engaged with other people during the day, and in terms of age (). One man participated in the feasibility study. He was not accessible when it was time to make an appointment for the interview, despite several attempts to reach him. One of the participants was a dropout participant from the feasibility study who consented to participate in the present study. The participants had all used MSC but taken part in different modules of the programme due to the tailoring.

Table 1. Overview of the study participants.

Content of MSC

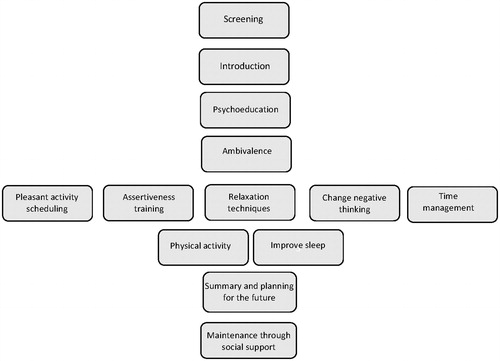

Information in MSC is delivered in text, movies and audio recordings. Empirical findings in several fields have been considered during the development process: stress management, behaviour change and information design. Interactivity comprises online assignments and assignments to complete between the online sessions. Tailoring is based on the experienced symptoms of stress using the Symptoms of Stress Survey (SySS) and readiness to change. SySS was developed for the tailoring in MSC. Symptoms experienced leads to tailored recommendations of modules for each user. The programme screens for stress levels (with PSS-14) and for depression and anxiety with the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) to target the intended population. Individuals experiencing stress but without clinical signs of depression and/or anxiety are permitted access to MSC. After screening for users’ stress level and symptoms of depression and anxiety, the programme starts with psychoeducation, information on what stress is and how to handle it, and education for users on how to make a behaviour analysis using the antecedent-behaviour-consequence model (ABC-model). Stress management modules include relaxation techniques, assertiveness training, pleasant activity scheduling, change negative thinking, time management, improve sleep and physical activity. The programme supports behaviour change in several ways, but five techniques are considered central and used in most modules: self-monitoring, goal-setting, re-evaluation of goals, feedback and prompting of the formulation of behaviour change intentions [Citation44]. Some assignments in the programme are locked for a certain number of days in order to facilitate users to work with them for some time. This time lock was not activated in this study, but the users were informed about it existing See for an overview of MSC.

Procedure

The first author visited three departments at the university and informed staff about the feasibility study and the interview study. Both oral and written, information included the aims of the studies, the fact that participation is voluntary and could be withdrawn at any time, how the data were stored, and the ethical considerations of participation. Information included the content of MSC and estimated time involved in using the programme. Interested individuals signed informed consent for both studies. After completing participation in the feasibility study, the participants were consecutively asked to take part in the present study.

Individual semi-structured interviews

Interviews were held in a private room chosen by the participants, in most cases their offices. The tape-recorded interviews lasted from 21 (only one interview) to 40 min, in all approximately 4.5 h. The first author carried out the interviews. The interviews were semi-structured with open-ended questions. To elicit more detailed information than was given in the first answer and to steer the interviews toward the study’s aim, probing questions followed the main questions [Citation45]. Interview questions focussed on how the user worked with the programme as a whole and in specific parts, whether the user understood how to use the programme and the assignments, how the user experienced how the programme was tailored and thoughts about working with stress management using a programme such as MSC. The participants were encouraged to suggest changes, and reflections from each interview were noted.

Qualitative content analysis

The text was analysed using a qualitative content analysis [Citation46]. The research question and the need to reach the manifested content of the interviews steered the decision to use a qualitative content analysis. Thus, methods such as phenomenology or grounded theory were not suitable [Citation47]. The first author listened to and transcribed the interviews verbatim. The first author read the transcribed text several times to obtain a picture of what the participants were talking about. Meaning units that consist of words or sentences that are related to the aim were highlighted and condensed. The condensed meaning units were abstracted into codes. All codes were grouped together, forming eight sub-categories and two categories. The whole text was considered during the analysis and when uncertainties were brought up the code was taken back to the unit of analysis to achieve credibility [Citation48]. The sub-categories consist of codes sharing commonalities, and there was a striving to create mutually exclusive categories from the sub-categories. In the final stage, a theme was identified that connected the categories. During the analysis process, the first, second and fourth authors discussed the coding, the sorting of the codes and the tentative sub-categories and categories, comparing individually performed analyses of parts of the material on several occasions. The final sub-categories, categories and theme were discussed and agreed upon. The analysis process is illustrated in .

Table 2. Examples of the process of the qualitative content analysis.

Results

The analysis resulted in one theme: Struggling with what I need when stress management is about me. The theme was divided in two categories. The first, Defining the needs, contains four sub-categories: time – a paradox in stress training, adequate presentation for a stressed individual, a relevant programme, and make stress management happen in my reality. The second category, It is about me, also contains four sub-categories: taking departure from me, a programme that understands what I need, perceived gains and possibilities of choices and structure. provides an overview of sub-categories, categories and the theme.

Table 3. Overview of sub-categories, categories and theme from the analysis of the users’ experiences of MSC.

Struggling with what I need when stress management is about me

The theme sheds light on the paradoxes experienced by the users when trying to handle their stress using MSC. Time was experienced and expressed as a paradox. To have access to a programme that supports individualised and tailored stress management was expressed as something good to handle stress at an individual level, but at the same time paradoxical when being stressed taking time to work with an extensive programme, thus leading to exacerbated feelings of stress. To handle stress with MSC on ones’ own, it was expressed, there needed to be a great deal of information, but the heavy load of information needed to be presented and structured in a way that did not lead to feelings of being overwhelmed and getting lost. Yet, at the same time MSC was experienced as somewhat stiff and the participants felt steered and not being able to pick and choose, losing some of the feeling of it being tailored.

Defining the needs

This category consists of descriptions of the prerequisites needed to use the programme concerning both environmental factors and what is needed from the programme itself. The programme was experienced as extensive; it was perceived as contradictory when the lack of time is a source of stress, and stress management takes time. The programme was perceived as complicated and overwhelming at first sight. However, participants also expressed that a self-management programme needs to have extensive information to enable self-management. A programme like MSC allows stress management training to happen at a convenient time and place for the user. But because the users are on their own, the programme can easily be forgotten about or pushed aside for other priorities.

Time – a paradox in stress training

Central in the data was expressions about how the shortage of time is a source for stress, and when stress management takes time, it is a paradox. The programme was perceived as extensive in relation to the time the participants had access to the programme. When there was time, the participants wanted a programme that does not take more time than necessary. Reducing stress was nevertheless identified as something that really does take time. If it is defined exactly what amount of time is expected each day, it would be helpful in order to plan and use the programme. The programme was perceived as extensive, but participants did not suggest what should be excluded.

The extensiveness of the programme as well as having time locked assignments was perceived as indicating that getting rid of stress is not a ‘quick fix’; still, a quick fix was desired.

… And that is the positive thing with the time locked assignments. I’m thinking, it indicates that change takes time. So, it is not like it’s a quick fix. (Study participant no. 5)

Time, it was noted, was needed to be set aside to work with the programme, but the programme was difficult to plan for, even for the closest upcoming days. High workloads during the study were perceived as a barrier for engaging in the programme. Some expressed that they wanted to work with the programme during a calmer period at work.

If there were time, the programme was believed being something that could help manage stress, but the given time frame for the study was perceived as too short for working through the programme, and some parts were just ‘clicked through’. Still, a time limit was believed to facilitate use of the programme without procrastination.

I don’t feel that this HAS to be changed. Of course, some things can be improved. I saw a spelling mistake or other small things. But, as a whole, I think it’s a very good program. But that it was so extensive, it made it a little difficult to accomplish for me. (Study participant no. 2)

Adequate presentation for a stressed person

The platform was perceived as easy to navigate. But, at first sight the programme appeared complicated to use and to include too much information. Thus, the programme itself triggered stress. Paradoxically, a self-management programme was expressed as needing to have a great deal of information and when becoming familiar with the programme it was not as extensive as first expected. The information was easy to understand, and assignments could be completed independently. The examples provided sufficient feedback for the participants to complete assignments. Other types of feedback, such as tables and notifications on the screen, were not identified by the participants, and the tables with graphs describing changes over time were often not used. Overall, feedback was expressed as important, and even without extensive personalised feedback, MSC was helpful.

It was that when you open it (the program), there are so many things you can click on. (…) It might be good that not everything appeared on the screen visually because it should be… should not feel like this is complicated. (Study participant no. 9)

Films, as information channels, were perceived as positive. They were perceived as adequate regarding length, were informative and easy to grasp and served as a starting point for reflections about stress. To be able to choose how to receive the information since it was provided both in text and in films was seen as positive.

The built-in questionnaires were perceived as too long; for example, the SySS had only small nuances between some presented symptoms, especially regarding problematic sleep. Completing the questionnaires took an unnecessarily long time.

One major problem with the usability of the programme was that the participants did not reach the last module because there were activities that they failed to mark as finished. The participants did not understand, to a large extent, that parts of the programme could be skipped and how to mark these modules as ‘finished’ activities and move on. They suggested to include some kind of overview in order to understand the programme as a whole.

A relevant programme

Stress was expressed as something that needed to be handled at an early stage and something everyone could benefit from learning. If not experiencing stress currently, examples to work with in the assignments were hard to find and decreased the motivation to use the programme. Still, the programme was perceived as unsuitable for those with extremely high levels of stress. The participants identified that being able to take responsibility, being motivated, staying disciplined and having good social relationships are essential to change the behaviour, when working with self-management to handle stress.

A programme like MSC could be an alternative for face-to-face contact because, as expressed, some people do not like to ‘go and talk to someone’. Face-to-face contact was expressed as to be felt like a big deal sometimes. Here, a programme like MSC could be offered at an early stage. Using a programme instead of face-to-face counselling was perceived as comfortable because the participants were not being supervised and thus were more independent. Nevertheless, feedback in face-to-face contact could be more personalised. The programme was suggested as a complement to traditional therapy for those with very high stress levels.

So, I think, not everyone likes to talk to someone. It depends on which phase you are in. Sometimes it may be nice not to talk to anyone. In that case, I think it's good that there is an electronic tool that does not require to meet anyone. Where you can sit in your bathrobe if you want or maybe if you’re still in bed. And I think it’s good that there is a good alternative, for everything does not fit everyone. (Study participant no. 1)

Make stress management happen in my reality

The programme enabled stress management training to occur wherever and whenever. Engagement in the programme was more present in the beginning. Finding a routine was identified as important to make stress management training happen. But if the planning was disrupted, it was hard to get back on track. It was difficult to remember log-in details and to remember to practice the techniques in everyday life. One suggestion was to have reminders sent to the person’s cell phone. Another was to make log-in and registering assignments easier.

If something was difficult to understand or get started, access to support from a real person was desired. Now, difficult tasks were just skipped. To keep motivation, a personal contact in the beginning, at some point during the programme, and toward the end would be helpful. Feedback was important, and without feedback, motivation can be lost. If the programme could more clearly indicate that one is on the right track, it could have helped to maintain motivation. To discuss with colleagues was suggested as something that could be helpful for keeping motivation.

I know I should do it, and I know I should do something at a certain time. Then, then, I think I would do it if I would get into some rhythm and do it regularly. I am almost convinced about that. It’s just that it has to be very simple. That's the most important thing for me. (Study participant no. 4)

It is about me

Learning how to use the ABC model and to understand their stress was perceived as central, giving the participants a frame to work with their own stress-related problems. It was considered logical to use the ABC model in the tailoring process, thus departing from their own stress-related problems and sometimes problematic behaviour. Being involved in the study gave participants valuable insights into their own stress and tools to handle stress at an individual level in everyday life to take control over the stress.

Taking departure from me

The ABC model gave the participants a tool for understanding their own stress, initiated reflections about their own stress and it was perceived logic as central in the tailoring of MSC. It was easy to find situations from which to depart. At times, the ABC model was not comprehensive. The programme was also perceived as facilitating individual goal setting; the programme did not provide any previously determined goals making the goals relevant when set by the individuals. It was perceived as both difficult and easy to formulate goals, and when goals were not achieved, it led to frustration. Formulating the goals was one of the assignments that was often skipped and felt redundant.

Yes, you got something to start from (regarding the ABC model). Like something to take off from instead of just ending up with a lot of different techniques and not really knowing what I'm striving for and where I'm departing from. What is my starting point, and where do I want to go? So, I thought it was great. And it became much clearer, visually, to me what my problem is, so to speak. (Study participant no. 2)

A programme that understands what I need

Although there were some shortcomings regarding the tailoring, it was considered logical to learn the recommended stress management techniques. One shortcoming was that the programme did not detect stress levels and recommended all the stress management techniques even when stress levels were low, which felt illogical. But if one were very stressed, all the techniques were perceived as relevant.

Participants worried about how conditions with the same symptoms as stress could confuse the programme. Some symptoms of stress were perceived as missing, leading to difficulties in describing the stress.

The content was perceived as relevant, but there were also suggestions for additional techniques: anger control and information about diet and stress. But it was doubted as to why physical activity was included.

I experience that everything is correct, except the sleep part, every part is correct for me. So, it (the program) could sense what my problem is, sort of. And that was pretty cool to see. (Interview no 7)

Perceived gains

Although the time frame for using the programme within the study was perceived as short, the participants expressed that they obtained valuable outcomes, such as insights regarding what stress is generally, what stress is for them as individuals, what symptoms of stress could be and how they had changed their behaviour to better cope with stressful situations.

The programme prompted the participants to start rehearsing stress management training and to start working with techniques they had tried before. The programme was described as a wakeup call when recommending certain, unexpected techniques.

But at the same time, it’s a wakeup call that the system thought that you’d have to look at this particular part first and foremost, and I understand that it's how I responded until I got my individual program. And it made me start thinking that I might have to look a little more on myself now that I’m talking about the fact that I’m already doing different things to fix my everyday life. So, ha ha ha. I’m actually, without going through the whole program, trying to work a bit more with my time management, so already you've succeeded, you little dodgers. (Study participant no. 1)

Possibilities of choices and structure

The positive aspect of being able to choose was often emphasised among the participants. They described how they chose the parts they were more interested in and skipped others. However, they reported that there could have been the option too more freely choose among the films, the assignments and tips in the programme instead of being forced into following a fixed structure. The structure was perceived as rigid and unnatural, and the programme was seen as guiding them a little too much. This contributed to the programme being perceived as ‘chopped up’ into small pieces. Nevertheless, structure was also identified as something important for ‘others’.

If you are going to follow the program to a T as it is, you are forced into a strict structure that may be a bit tricky. (Study participant no. 5)

Discussion

The aim of the study was to explore the experiences of using a tailored and interactive web application that supports behaviour change in stress management (MSC), and to identify if, and what, in the web-based programme needed further development or adjustment to be feasible in a RCT.

One theme was identified, Struggling with what I need when stress management is about me, capturing the paradox of having a programme that is perceived as good for supporting stress management, while at the same time being extensive to use. The information load was perceived as heavy, and users are on their own, not having someone supporting and encouraging them to use the programme.

The theme was divided into two categories: In the first, Defining the needs, the participants expressed what they needed to use the programme. In the second category, It is about me, the participants considered how the programme was able to focus on their unique stress-related issues, making stress management about them.

In the present study, we foremost investigated how the website characteristics were perceived and experiences in relation to using this web-based programme, since characteristics affects website adherence as described in the behaviour change model for Internet interventions [Citation38]. Time as an environmental factor, more specifically the lack of it, was the most prominent factor mentioned by the participants. The kind of support needed was another factor; specifically, participants reported that some could benefit from having support from a person to get started, but that for the rest of the programme only limited support was needed. Participants also mentioned insights and behaviour changes after using the programme.

Central in the first category, Defining the needs, was descriptions about time as a paradox. Working with an extensive web-based programme could become a source of stress if a shortage of time is perceived as the primary reason behind one’s stress. Nevertheless, MSC includes effective, evidence-based strategies for behaviour change and stress management, and it is a complex programme that uses multitrack possibilities to tailor itself and its functions to the user. But complex does not have to equate complicated [Citation49]. Complex could be defined as consisting of several parts, while complicated could be defined as hard to understand [Citation49]. Simplicity is, as well as complex and complicated, a subjective property, and what is simple differs from person to person. It is crucial strive for complex programmes to be perceived as simple. There is also a risk that if simplified too far, the entity will be lost. MSC’s included techniques were built on evidence and simplifying them could lessen their effectiveness. It might be beneficial to have a more stripped-down visual format because the participants also expressed that the programme was not as overwhelming when they became more familiar with it.

In the literature on stress, time has mostly been described as objective, physical and quantifiable, but a recent review on stress and time proposed time as a subjective matter in terms of perception and meaning and how it can influence the perception of stress [Citation50]. To understand how time is perceived, it is crucial to understand individuals’ relations to their environment and reaction to stressful events. The perception of time is influenced by cultural norms, individual perceptions of time and situational factors [Citation50]. One’s experience of work stress depends on norms, both cultural and organisational, which could influence how much time is acceptable to spend on, for example, such a programme as MSC.

Earlier studies have shown that feedback is important for supporting health-related behaviour change [Citation44,Citation51]. In the present study, the participants expressed that feedback was not missing and was sufficiently provided in MSC. Still, further investigation is needed to determine how feedback can support the users of MSC.

The second category, It is about me, considers how the stress management programme is experienced as focussing on the individuals’ own stress, tailoring the programme to their needs, and suggesting relevant assignments. It also reflects how the participants spoke about their beliefs regarding how using this programme really could affect their stress levels. Education on how to understand and cope with health problems such as stress, anxiety or depression is often called psychoeducation, and it includes both information about the disorder in question as well as analysis of problems with, for example, the ABC model. Studies have shown that psychoeducation alone can be helpful in lowering stress levels [Citation52,Citation53]. However, a general psychoeducational module, as in MSC, does not provide tailored assignments to handle specific stress-triggered symptoms, for example, sleeping problems, and may not contribute to sustainable behaviour change. Thus, the sustainable effect of non-tailored psychoeducation can be questioned and needs to be further studied.

Using more advanced technology with, for example, sensors [Citation54] to measure stress levels and tailor the programme with the sensed information could contribute to the feeling of the programme being more flexible and personal.

Individual interviews were determined to be the most appropriate data-collection method since the main aim was to study in-depth and personal experiences in relation to the participants’ own stress. Sensitive topics are more likely to be raised in individual interviews than in focus group interviews [Citation55]. However, if the focus had been solely on problems solving to continue the development of MSC, focus groups could have been more appropriate [Citation56].

One of the interviews in the present study lasted for 21 min. This could have limited the level of depth of information provided by the informant. This specific participant was relatively satisfied with the programme, reached the final module, and seemed to understand the logic of the programme. This participant also clearly described what she did and did not use. She did not have any suggestions for changes except describing the programme as too extensive. Furthermore, after seven interviews it was noted that there was no new information added by the participants in interviews eight and nine. This indicates that the sample contained sufficient information power in relation to the study aim.

It may have biased the results that the person conducting the interviews was also the developer of MSC, potentially affecting participants’ expression of negative comments. This is a potential limitation. Although, the second part of the aim of this study – to further develop MSC – was recognised as something that might have facilitated negative comments contributing to further development. The participants were encouraged on several occasions to provide negative comments regarding MSC. Furthermore, it would have been problematic to have an interviewer who was not familiar with MSC in detail, which could have prevented him/her from asking relevant and necessary probing questions. A deep understanding of how MSC is built and where the critical points of navigating MSC are located was necessary knowledge for the interviewer to possess. Still, the preunderstanding must be bridled and self-reflected to be self-aware of the researcher’s role [Citation57]. The notes made during each interview were used as a base for the reflexions and for trying to identify behaviours that could bias the results. Self-awareness was also discussed among the co-researchers during the analysis process [Citation46].

Social critique deals with reflections regarding the power-balance between the interviewer and the interviewees to understand the interviewers’ role and impact in the interview situation [Citation58]. The power balance was reflected upon both when deciding who was the most appropriate interviewer in this study and during the analysis process. The interviewer is an ‘easy-going’ person, and the interviews were characterised by openness and a permitting climate to express one’s ideas. Notes were made after every interview, as a logbook [Citation45], to be able to recall the memory of what the climate was like during the interviews and in order to be able to reflect upon the interviewer’s role during the interviews.

Researchers have argued that 12 participants would be an optimal number for an interview study [Citation59]. But when the study’s aim is narrow, with a dense and homogeny sample relevant as in this study, even smaller numbers are acceptable [Citation60]. The study’s aim can be considered narrow when it is meant to investigate the use of a specific product and all study participants have used the same product, contributing to the density of the sample. Additionally, a strong dialogue between the interviewer and the participants also permitted the lower number of participants [Citation60]. The interviewer has training and experience in motivational interviewing and several years of experience interviewing patients for medical histories, likely contributing to an open and encouraging interview situation. The interviews were characterised by openness, and the participants opened up to the interviewer with both personal problems and situations in relation to using the programme. This was considered proof that the participants felt comfortable during the interviews, contributing to a strong dialogue.

The participants recruited for this study all scored 17 or higher on the PSS-14, meaning that they all experienced some level of stress. Including individuals experiencing higher levels of stress possibly on sick leave, or being from other working contexts may have produced different results and other needs for the programme to fulfil. However, the programme has been developed to tailor and target stress-related symptoms in persons who are not on sick leave. In addition, the participants had different types of work, giving the sample some variation.

The results indicate that several features of MSC could be further developed. The experiences of the programme being too extensive needs to be considered for further development and when introducing the programme to potential users. Information in the programme could be developed to support the users in making choices, for example, showing them how to skip parts of the programme perceived as irrelevant to in order for them to reach the end module. Because, environmental factors, such as time available to spend on the programme, affect the use of the programme, future users may benefit by having permission to use the programme during a specified part of their working hours. This would likely require a reduced number of work duties. This programme focuses on the users’ behaviour change, which could be provocative to users where stress-related problems derive from a problematic or unjust work site. The participants in this study expressed acceptance of using a programme like MSC to handle work-related stress on an individual level, and it was considered as a good tool to use prior to when stress reached levels necessitating sick leave.

Conclusion

The main theme describes how the participants expressed acceptance of using the web-based programme for stress management, still, there is a struggle to use an extensive programme for stress management when already stressed. The perceived extensiveness of the programme must be considered in further development of the programme.

Ethical approval

This study was reviewed and approved by the regional ethics committee in Uppsala, Sweden (Dnr 2015/555).

Disclosure statement

The authors CE, ME and YE report no conflict of interest. AS is the Editor-in-Chief of the European Journal of Physiotherapy.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Barkman C, Weinehall L. Policymakers and mHealth: roles and epectations, with observations from Ethiopia, Ghana and Swedan. Glob Health Action. 2017;10(sup 3):1337356.

- Söderlund A, Bring A, Åsenlöf P. A three-group study, internet-based, face-to-face based and standard-management after acute whiplash associated disorders (WAD)-choosing the most efficient and cost-effective treatment: study protocol of a randomized controlled trial. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2009;10:90.

- del Pozo-Cruz B, del Pozo-Cruze J, Adsuar JC, et al. Reanalysis of a tailored web-based exercise programme for office workers with sub-acute low back pain: assessing the stage of change in behaviour. Psychol Health Med. 2013;18:687–697.

- Moreau M, Gagnon M-P, Boudreau F. Development of a fully automated, web-based, tailored intervention promoting regular physical activity among insufficiently active adults with type 2 diabetes: integrating the I-Change Model, self-determination theory, and motivational interviewing components. JMIR Res Protoc. 2015;4:e:25.

- Kelders SM, Kok RN, Ossebaard HC, et al. Persuasive system design does matter: a systematic review of adherence to web-based interventions. J Med Internet Res. 2012;14:e152.

- Friederichs S, Bolman C, Oenema A, et al. Motivational interviewing in a web-based physical activity intervention with an avatar: randomized controlled trial. J Med Internet Res. 2014;16:e48.

- Hammel LM, Robbins LB. Computer- and web-based interventions to promote healthy eating among children and adolescents: a systematic review. J Adv Nurs. 2013;69:16–30.

- van Straten A, Cuijpers P, Smits N. Effectiveness of a web-based self-help intervention for symptoms of depression, anxiety, and stress: randomized controlled trial. J Med Internet Res. 2008;10:e7.

- Carlbring P, Maurin L, Törngren C, et al. Individually-tailored, internet-based treatment for anxiety disorders: a randomized controlled trial. Behav Res Ther. 2010;49:18–24.

- Siegrist J, McDaid D, Freire-Garabal M, et al. Economy, stress and health. Declaration of the Santiago de Compostela Conference, July 18, 2013; Santiago de Compostela: University of Santiago de Compostela; 2013.

- Sweden’s Social Insurance Agency (Försäkringskassan). Stress, the most common reason for sick leave [Stress vanligaste orsaken till sjukskrivning]; 2015 [cited 2015 Oct 8]. Available from: http://www.forsakringskassan.se/press/pressmeddelanden/stress_vanligaste_orsaken_till_sjukskrivning

- Nyberg ST, Fransson EI, Heikkilä K, et al. Job strain and cardiovascular disease risk factors: meta-analysis of individual-participant data from 47,000 men and women. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e67323.

- OECD. Mental health and work: Sweden. Paris: OECD; 2013 [cited 2018 Jan 9]. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264188730-en

- Åkerstedt T, Knutsson A, Westerholm P, et al. Sleep disturbances, work stress and work hours: a cross-sectional study. J Psychosom Res. 2002;53:741–748.

- Cohen S, Williamson GM. Stress and infectious disease in humans. Psychol Bull. 1991;109:5–24.

- Smolderen KG, Vingerhoets AJ, Croon MA, et al. Personality, psychological stress, and self-reported influenza symptomatology. BMC Public Health. 2007;7:339.

- Kraatz S, Lang J, Kraus T, et al. The incremental effect of psychosocial workplace factors on the development of neck and shoulder disorders: a systematic review of longitudinal studies. Int Arch Occup Environ Health. 2013;86:375–395.

- Yamagishi M, Kobayashi T, Kobayashi T, et al. Effect of web-based assertion training for stress management of Japanese nurses. J Nurs Manag. 2007;15:603–607.

- Allexandre D, Bernstein AM, Walker E, et al. A web-based mindfulness stress management program in a corporate call center: a randomized controlled trial to evaluate the added benefit of onsite group support. J Occup Environ Med. 2016;58:254–264.

- Billings DW, Cook RF, Hendrickson A, et al. A web-based approach to managing stress and mood disorders in the workforce. J Occup Environ Med. 2008;50:960–968.

- Frazier P, Meredith L, Greer C, et al. Randomized controlled trial evaluating the effectiveness of a web-based stress management program among community college students. Anxiety Stress Coping. 2015;28:576–586.

- Hasson D, Anderberg UM, Theorell T, et al. Psychologichal effects of a web-based stress management system: a prospective, randomized controlled intervention study of IT and media workers. BMC Public Health. 2005;5:78.

- Heber E, Lehr D, Riper H. Web-based and mobile stress management intervention for employees: a randomized controlled trial. J Med Internet Res. 2016;18:e21.

- Richardson KM, Rothstein HR. Effects of occupational stress management intervention programs: a meta-analysis. J Occup Health Psychol. 2008;13:69–93.

- Zetterqvist K, Maanmies J, Ström L, et al. Randomized controlled trial of internet-based stress management. Cog Behav Ther. 2003;32:151–160.

- Hasson H, Brown C, Hasson D. Factors associated with high use of a workplace web-based stress management program in a randomized controlled intervention study. Health Educ Res. 2010;25:596–607.

- Williams RA, Gatien G, Hagerty BM. Design-element alternatives for stress-management intervention websites. Nurs Outlook. 2011;59:286–291.

- Eklund C, Elfström ML, Eriksson Y, et al. Development of a stress management web application for persons with work related stress (submitted).

- Eklund C, Elfström ML, Eriksson Y, et al. Web-based stress management supporting behavior change – a feasibility study. J Technol Behav Sci. 2018 [Feb 15];[1–11]. doi: 10.1007/s41347-018-0044-8

- Webb T, Joseph J, Yardley L, et al. Using the internet to promote health behavior change: a systematic review and meta-analysis of the impact of theoretical basis, use of behavior change techniques, and mode of delivery on efficacy. J Med Internet Res. 2010;12:e4.

- Bandura A. Human agency in Social Cognitive Theory. Am Psychol. 1989;44:1175–1184.

- Lazarus RS, Folkman S. Stress, appraisal and coping. New York (NY): Springer; 1984.

- Folkman S. Personal control and stress and coping process: a theoretical analysis. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1984;46:122–147.

- Prochaska J, DiClemente C. Stages of change in the modification of problem behaviors. Prog Behav Modif. 1992;28:184–218.

- Horiuchi S, Tsuda A, Kim E, et al. Relationships between stage of change for stress management behavior and perceived stress and coping. Japan Psychol Res. 2010;52:291–297.

- Knittle K, De Gucht V, Maes S. Lifestyle- and behaviour-change interventions in musculoskeletal conditions. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2012;26:293–304.

- Madden TJ, Ellen PS, Ajzen I. A comparison of the theory of planned behavior and the theory of reasoned action. Pers Soc Psychol Bull. 1992;18:3–9.

- Ritterband L, Thorndike F, Cox D, et al. A behavior change model for internet interventions. Ann Behav Med. 2009;38:18–27.

- Brinkborg H, Michaneck J, Hessel H, et al. Acceptance and commitment therapy for the treatment of stress among social workers: a randomized controlled trial. Behav Res Ther. 2011;49:389–398.

- Cohen S, Kamarck T, Mermelstein R. A global measure of perceived stress. J Health Soc Behav. 1983;24:385–396.

- Cohen S, Williamson GM. Perceived stress in a probability sample of the united states. In: Spacapan S, Oskamp S, editors. The social psychology of health. Newbury Park (CA): Sage; 1988. p. 31–67.

- Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1983;67:361–370.

- Eskin M, Parr D. Introducing a Swedish version of an instrument measuring mental stress. Stockholm (Switzerland): Department of Psychology, Stockholm University; 1996.

- Michie S, Abraham C, Whittington C, et al. Effective techniques in healthy eating and physical activity interventions: a meta-regression. Health Psychol. 2009;28:690–701.

- Polit DF, Beck CT. Nursing research: generating and assessing evidence for nursing practice. Philadelphia (PA): Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins; 2011.

- Graneheim UH, Lundman B. Qualitative content analysis in nursing research: concepts, procedures and measures to achieve trustworthiness. Nurs Educ Today. 2004;24:105–112.

- Bengtsson M. How to plan and perform a qualitative study using content analysis. NursingPlus Open. 2006;2:8–14.

- Lincon YS, Guba EG. Naturalistic inquiry. Newbury Park (CA): Sage; 1985.

- Mollerup P. Simplicity: a matter of design. Amsterdam (Netherlands): BIS Publishers; 2015.

- Eldor L, Fried Y, Wetman M, et al. The experience of work stress and the context of time: analyzing the role of subjective time. Organ Psychol Rev. 2017;7:227–249.

- Heber E, Ebert DD, Lehr D, et al. Efficacy and cost-effectiveness of a web-based and mobile stress-management intervention for employees: design of a randomized controlled trial. BMC Public Health. 2013;13:655.

- Shimazu A, Kawakami N, Irimajiri H, et al. Effects of web-based psychoeducation on self-efficacy, problem solving behavior, stress responses and job satisfaction among workers: a controlled clinical trial. J Occup Health. 2005;47:405–413.

- Van Daele T, Hermans D, Van Houdenhove C, et al. Stress reduction through psychoeducation: a meta-analytic review. Health Educ Behav. 2012;39:474–485.

- Begum S, Ahmed MU, Funk P. Individualized stress diagnosis using calibration and case-based reasoning. Proceedings of SAIS 2007: The 24th annual workshop of the Swedish Artificial Intelligence Society, 2007 May 22–23, Borås, Sweden; 2007. p. 59–69.

- Kaplowitz MD. Statistical analysis of sensitive topics in group and individual interviews. Qual Quant. 2000;34:419–431.

- Kaplowitz MD, Hoehn JP. Do focus groups and individual interviews reveal the same information for natural resource valuation? Ecol Econom. 2001;36:237–247.

- Dahlberg K, Dahlberg H, Nyström M. Reflective lifeworld research. Lund (Sweden): Studentlitteratur; 2008.

- Finlay L. Negotiating the swamp: the opportunity and challenge of reflexivity in research practice. Qual Res. 2002;2:209–230.

- Guest G, Bunce A, Johnson L. How many interviews are enough? An experiment with data saturation and variability. Field Methods. 2006;18:59–82.

- Malterud K, Siersma VD, Guassora AD. Sample size in qualitative interview studies: guided by information power. Qual Health Res. 2015;26:1753–1760.