Abstract

Purpose

The purpose of this study was to investigate what treatment methods physiotherapists in Sweden use for infants 0–24 months hospitalised with acute breathing difficulties due to lower respiratory tract infections.

Material and methods

We constructed an anonymous digital survey for paediatric physiotherapists in Sweden. It was distributed by e-mail and was posted on professional websites. Completed forms were obtained from all 21 counties in Sweden.

Results

Eighty-eight physiotherapists replied and 52 worked with the target group. Different treatment methods were used, based on the situation and the individual’s symptom. The most common methods involved physical activity and change of the body position.

Conclusions

A variety of treatment methods are used by the Swedish physiotherapists. The most commonly used are treatment methods involving frequent changes of the body position and stimulation to physical activity. Thus, the praxis in Sweden seem to differ from methods described in the literature. Methods are chosen depending on the symptoms of the patients. No differences in the choice of treatment methods were found regarding the physiotherapists’ background characteristics.

Introduction

Bronchiolitis is a lower respiratory tract infection and the most common cause of hospitalisation for infants younger than 2 years [Citation1] and involves a high cost for families and health care organisations around the world [Citation2]. In a population based study [Citation3] 20% of the children under 2 years of age were diagnosed with bronchiolitis, and 3% were hospitalised. In bronchiolitis the airways are thickened due to inflammation with oedema, and increased mucus production leads to occlusion or narrowing of the airways [Citation4,Citation5]. The infants often have an increased work of breathing and difficulties to maintain fluid balance and nutrition status. The oxygen saturation is often low. Different medical treatments have been used, and there is no definite consensus about the best practice [Citation6,Citation7]. Antibiotics, corticosteroids, bronchodilators and antivirals are not generally recommended. Supporting treatment such as oxygen therapy, fluid/nourishment supplement is common [Citation8].

Physiotherapy treatment is sometimes used for children and infants who are hospitalised with bronchiolitis and other acute breathing difficulties such as pneumonia, to alleviate their symptoms. Physiotherapy methods aim at moving and evacuating mucus from the airways in order to reduce work of breathing, increase gas exchange/oxygen saturation and increase lung volumes [Citation9–11]. Outcome measures used in studies can also include time to reach clinical stability or length of hospital stay [Citation12,Citation13]. Chest physiotherapy for infants with bronchiolitis involves a wide range of methods. Some methods are not scientifically evaluated but several therapies have been evaluated in clinical trials in the last years. In guidelines the different methods are not specified, but referred to in general terms like ‘chest physiotherapy’ [Citation6,Citation8]. ‘Chest physiotherapy’ is not generally recommended for infants with severe bronchiolitis in a review, and especially not the forced expiration technique [Citation14]. In another recent review the authors conclude that the use of chest physiotherapy in children with acute viral bronchiolitis remains controversial [Citation15]. However, different physiotherapy treatment methods are presently being used in hospitals around the world. Some of the physiotherapeutic methods that are described in international literature for infants hospitalised with breathing difficulties such as bronchiolitis or pneumonia are: assisted or induced cough described as a brief manual pressure on the child’s trachea [Citation9,Citation13,Citation16], nasal-CPAP (Continuous Positive Airway Pressure) [Citation17–20], forced expiration technique [Citation9,Citation13], percussion [Citation12,Citation21–23], postural drainage [Citation12,Citation22–24], slow expiration technique [Citation12,Citation16], thoracic compressions [Citation12,Citation23,Citation25], thoracic vibrations [Citation12,Citation22–25]. With these methods, the physiotherapist applies manual techniques on the infant’s chest to alter the breathing pattern of the infant or puts the infant in an inclined resting position in order to move the mucus, or supplies mechanical airway pressure.

There is a lack of clinical guidelines/recommendations about the different physiotherapy treatment methods. Many physiotherapists in Sweden do not recognise the treatment methods described in the international literature for this particular group of patients as the methods they use in daily praxis, which makes it difficult to relate to international guidelines. In Sweden, physiotherapists work independently and normally choose treatment methods depending on their own professional judgement, which is based on relevant scientific evidence and personal experience [Citation26]. The panorama of treatment methods used in Sweden for infants with breathing difficulties are not yet fully known, and a description of the clinical practice in Sweden is lacking.

Aim

The aim of this study was to explore what physiotherapy treatment methods are being used in Sweden when treating hospitalised infants with acute breathing difficulties due to lower respiratory tract infections. The aim was also to investigate if there are any differences in choice of treatment related to the background characteristics of the physiotherapists such as professional experience, gender, type of hospital and graduation country.

Methods

In order to investigate what different treatment methods Swedish physiotherapists use when treating infants with breathing difficulties in hospitals, a digital web-based survey, Survey&Report (Artisan Global Media) was constructed. In the instructions to the informants, we asked for answers about their use of different physiotherapy treatment methods and outcome measures concerning infants in hospitals with acute breathing difficulties due to e.g. bronchiolitis, RS-virus and pneumonia. In the present paper only the treatment methods are reported and analysed. As only the most affected infants normally are hospitalised [Citation3,Citation27], the present study concerned those with moderate to severe breathing difficulties. The survey mainly consisted of closed questions, with given alternatives to choose from. It was also possible to answer in free text. In order to develop the answers, a few additional questions regarding details were shown if the respondents chose certain answers. See Appendix 1 for the entire survey translated into English.

The survey was purpose-built for this study, and to ensure its validity the following actions were taken. The answer options were chosen from reviewing literature and from the main author’s clinical experience. It was also at an early stage discussed with other physiotherapists. A pilot survey was distributed to a panel of 8 physiotherapists in Sweden, some with expert knowledge in the area and some with a more general paediatric knowledge. They discussed their views with the main author, either by telephone or e-mail communication. The survey was adjusted to its final design when consensus was reached in the panel group. Practical advice and help to constructing the survey was also obtained from literature on the subject [Citation28–30]. The survey was distributed to physiotherapists in Sweden working with children in hospitals in April and June 2017. It was posted on two different closed Facebook groups for physiotherapists in the professional union “Fysioterapeuterna”, and also on the union’s closed homepages in both the departments of respiration and of paediatrics, that are available only for members of this professional union. It was also distributed by e-mail directly to physiotherapist working with paediatrics at hospitals in the south of Sweden and to physiotherapist working with paediatric heart diseases, known from previous collaboration. Furthermore, it was sent by e-mail to 21 contact nurses at hospitals in Sweden where there are children’s wards, with a request to forward the link with the survey to the relevant physiotherapists working at their children’s ward in the hospital. A reminder with the same link and information was posted two weeks after the first distribution.

When all data was collected we found that the treatment methods could be sub-grouped as passive or active methods or neither active or passive. Details are shown in the Result section. When defining a method as active or passive respectively, we made a distinction between putting the infant in a resting position or a drainage position on one hand (passive), and frequently alternating positions in bed or in the adults arm on the other hand (active). The decision was based on the repeated movements and the expected effect. Alternating the positions and making other movements such as passive arm movements were labelled ‘active’ for their aim to stimulate deeper breaths by activity. The passive treatment methods were labelled ‘passive’ for their aim to reduce work of breathing in the resting position or manual compressions of the chest. The methods were labelled ‘active’ and ‘passive’ during the data analysis and thus not known to the respondents.

Statistics

The results were compiled and analysed in the IBM SPSS Statistics version 25 (IBM Corporation Armonk, New York, United States). The analyses were mainly descriptive using mean values and standard deviations when data were normally distributed and median and inter quartile range and min-max when data was not normally distributed. We performed Chi2 tests to compare the use of active and mixed active and passive treatment methods with the physiotherapists’ background characteristics. A p-value below 0.05 was determined as statistically significant.

Ethics

There was no personal contact between the respondents and the researchers. The answers were marked and collected electronically. It was clearly stated in the adjacent text that it was anonymous, and no individuals could be identified in the responses. The survey is not considered dealing with sensitive information but only with choice of methods. The Regional Ethical Review Board in Lund approved the study in April 2017 (2017/190).

Results

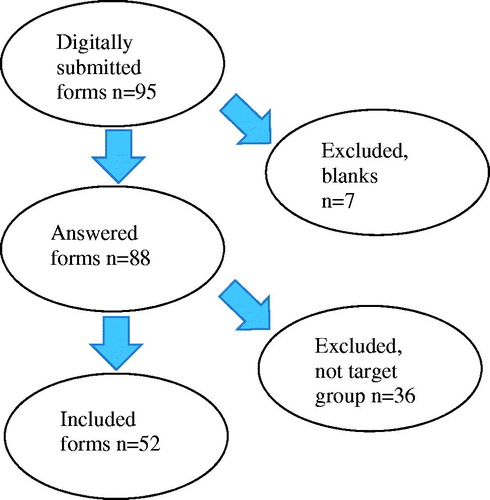

Completed questionnaires were returned from all 21 counties in Sweden. Only physiotherapists who had treated infants with respiratory problems in hospitals during the last 2 years were included, see .

Background information about the 88 respondents is shown in . After excluding those respondents who did not treat infants with respiratory problems in the last 2 years, a total of 52 respondents remained.

Table 1. Background information of the respondents. n = 88.

All the methods concerning physiotherapy for children 0–24 months hospitalised with breathing difficulties that were suggested in the survey were marked at least twice, see . All respondents (100%) marked giving information to the parents. One respondent gave in free text an example of information to the parents: “about the treatment that is prompted for the infant at the moment”. One respondent reported additionally in free text to use ‘huffing’ (forced expiratory technique) and ‘blowing games’ such as blowing bubbles and one respondent sometimes used a wrapped-in electric toothbrush for vibrations on the back.

Table 2. Treatment methods used by the Swedish physiotherapists for infants hospitalised with breathing difficulties, listed in frequency order.

The 49 of 52 respondents who had marked bouncing on a big ball were asked to specify the baby’s position on the big ball. The most common positions were sitting in the adult’s arms (n = 38, 77.6%), and prone on the ball (n = 37, 75.5%). Side lying on the ball and sitting on the ball were used by 33 respondents (67.3%). Side lying in adult’s arms were also common (n = 25, 51.0%). See examples in .

When describing the resting positions in the bed, several examples where obtained. The most frequent measures were to elevate the head of the bed, to change positions to side lying or prone, using support by pillows, using a sitting or semi-sitting position, or individually adjusted positions to support the work of breathing. Several respondents reported that the choice of action was based on the individual’s situation and breathing difficulties.

Thirty-one of the physiotherapist had given advice to other health professionals regarding inhalations, further tests, further actions or the use of flow/pressure devices such as Hi Nasal Flow, CPAP or BilevelPAP.

In , each respondent is characterised as either using passive or active or mixing active and passive methods in their three most commonly used treatment methods. Interventions not directed directly towards the infant, such as giving advice to parents or health professionals, were excluded from this analysis. In , the different methods are marked as active = a, passive = p or neither active or passive = -.

Table 3. Description of the most preferred treatment methods with regard to respondent properties.

When performing the Chi2 tests, there were no significant differences regarding treatment methods for the different groups: years since graduation, type of hospital or frequency treating the infants (p > 0.05), see . It was not possible to analyse the gender or graduation country in this way, as there were so few males and physiotherapists graduated outside of Sweden, see .

Discussion

This study describes a toolbox of physiotherapeutic treatment methods used for infants with breathing difficulties in Sweden. All the methods that were suggested in the survey was marked. This indicated that the physiotherapists used a wide variety of methods, educated parents and health care providers, used technical equipment, stimulated to physical activity and employed passive manual techniques. The physiotherapists in Sweden used internationally described treatment methods, but also to a large extent other methods.

The fact that all respondents marked that they gave information to the parents suggests that a common measure is to involve the parents in the treatment session. In clinical practice, the physiotherapist often starts the treatment session and the parents continue to do the same activities with their child as long as is needed throughout the hospital stay, with support by the physiotherapist.

The most common physiotherapy treatments in this study can be described as different ways of performing frequent changes of the body positions and stimulating physical activity. No respondent used only methods defined as ‘passive’ as their three most common treatment methods. A majority of the respondents reported only methods defined as ‘active’ as their three most common and the rest used a combination of methods defined as ‘active’ and ‘passive’.

The method of bouncing on a big ball was used by almost all respondents at some time, and is described by Lagerkvist [Citation31] when treating children with neuromuscular disorders in Sweden. The aim of using the big ball for children with neuromuscular disorders and secondary breathing problems seems to be the same as the desired effect for infants with bronchiolitis: increase deep breathing, cough and mucus transportation, and thus increase oxygen saturation [Citation31,Citation32].

There is a lack in the literature on descriptions of physiotherapy methods that stimulates physical activity such as lifting up in arms or changing the body positions, for infants with breathing difficulties due to airway infections. One guideline recommends on the contrary “minimal handling” of the infant [Citation33]. Balachandran et al suggests however: “…vigorous activity such as skipping and jumping can precede postural drainage in order to loosen the secretions, provided such activity is not contraindicated” [Citation34].

In international guidelines, physiotherapy is sometimes not recommended for children with bronchiolitis [Citation8]. However, it is not always clear what specific physiotherapy methods are referred to. The wide variety of physiotherapy treatment methods seems not to be generally recognised as there is a lack of clinical guidelines about the different physiotherapy treatment methods. That may be the reason why physiotherapists use such a wide variety of treatment methods despite the lack of evidence. In our opinion chest physiotherapy is often used as an umbrella expression, and with this study we wanted to add knowledge about the diversity of the methods used. We find it important that the clinical practice of chest physiotherapy around the world is displayed and thus made available for discussion and scientific evaluation.

The physiotherapists in Sweden may rely on well-known general physiological principles of frequent changes of the body positions and physical activity on lung function, as a basis for their clinical decision-making. The physiological response is among others that it stimulates deep breathing and increased lung volumes, increased expiratory airflow and thus enhances mucus transportation [Citation35,Citation36].

In Sweden, the chest physiotherapy that is generally used for children with respiratory difficulties is strongly influenced by the physiotherapy treatment for children with cystic fibrosis, CF. This treatment programme has excellent outcomes, even on a long term basis, and is used both in an acute phase of CF and as maintenance treatment [Citation23,Citation37–39]. Physiotherapy treatment for children with CF changed in the 1980s in Sweden from drainage positions and percussions to physical activity in combination with forced expiration technique [Citation40] and has continued to develop in that direction since then [Citation10]. The fact that physiotherapists mainly treat symptoms of the infants and not diagnoses [Citation41], may explain why this practice is widespread in Sweden.

Even though differences to internationally described physiotherapy treatment methods is the most striking result of this study, there are however some similarities as well. As all the methods listed in the survey were marked as being used at least by two respondents, the physiotherapists in Sweden can be described as using a wide variety of methods on the whole. There was a common use of PEP, cough support by hands on the thoracic wall or abdomen, light chest compressions and CPAP. So there seems to be a general usage of different strategies as well as the specific Swedish approach with physical activity.

We collected background characteristics of the informants with the idea that these variables might influence what treatment methods they used, but the physiotherapy treatment seems to be similar all over Sweden. There was no significant difference in the choice of treatment depending on what type of hospital the physiotherapists worked in, how long they had been graduated or their experience in treating infants in recent years. As there were so few internationally graded and few males in the study, it was not possible to draw any conclusions about treatment methods in relation to graduation country or gender.

There are some limitations with a survey study regarding how informants remember and retrospectively report. To secure the anonymity of the respondents we could not track individuals in the responses and for that reason we cannot rule out the risk that others than the intended population have answered the survey. We have however used closed Facebook groups for registered physiotherapists and professional e-mail addresses in order to direct the survey to the intended group. The aim of this study was to get as wide a view of the methods as possible, and for that purpose, a survey study was chosen, in spite of the possible risks above. We wanted answers from many individuals with a great variation in experience, from different types of hospitals and with a broad geographic representation. The digital distribution enabled an easy spread to many physiotherapists in all of Sweden. Although this does not guarantee that all eligible physiotherapists got the opportunity to answer the survey we think enough information has been collected. Answers were obtained from all counties in Sweden. Thirty-six of the physiotherapists (41%) who completed the survey had not treated infants with breathing difficulties the last 2 years, but they still filled in the form as far as was relevant. This suggests an overall high degree of answers. It is not known how many physiotherapists actually work with the target group. The Swedish population in 2017 was a little more than 10 million inhabitants [Citation42] and in that context, we estimate that a large amount of the total number of relevant respondents has replied to this survey.

The answer options were selected according to literature and professional experience, and the respondents could also add methods not listed by the authors, in free text. It would however have been interesting if we had also used “no treatment” as an option, as this might have added information about decisions to refrain from treatment.

It is likely that physiotherapists in other countries also use a large variety of methods, as the Swedish physiotherapists do. However, further studies are needed to explore the treatment methods physiotherapists use for this patient group in other parts of the world. Further studies are also warranted about selecting which patients and in what stage of the illness they may benefit from the different treatment methods.

The present study sheds light on the most commonly used physiotherapy treatment methods for infants with breathing difficulties in hospitals in Sweden. These treatment methods has to our knowledge not previously been described in connection with bronchiolitis or other acute lower respiratory tract infections, and have not been scientifically evaluated. Based on these results, our research group is running a randomised controlled trial to evaluate changes of body positions and stimulation to physical activity for these patients.

Conclusions

A variety of treatment methods are used by the Swedish physiotherapists. The most commonly used are treatment methods involving frequent changes of the body position and stimulation to physical activity. Thus, the praxis in Sweden seem to differ from methods described in the literature. Methods are chosen depending on the symptoms of the patients. No differences in the choice of treatment methods were found regarding the physiotherapists’ background characteristics.

Consent to participate

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Consent for publication

Consent for publication was obtained from all individuals or their guardians who shared person’s data, photos, in this manuscript.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all physiotherapists who participated in the study and also project manager Ola Stjärnhagen, system administrator of the web-based survey at Lund University for valuable help with technical aspects of constructing the digital survey and compilation of the answers.

Disclosure statement

The authors report no conflict of interest.

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Gillies D, Wells D, Bhandari AP. Positioning for acute respiratory distress in hospitalised infants and children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;(7):CD003645.

- Nair H, Simoes EA, Rudan I, et al. Global and regional burden of hospital admissions for severe acute lower respiratory infections in young children in 2010: a systematic analysis. Lancet. 2013;381(9875):1380–1390.

- Munoz-Quiles C, Lopez-Lacort M, Ubeda-Sansano I, et al. Population-based analysis of bronchiolitis epidemiology in Valencia, Spain. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2016;35(3):275–280.

- Fahy JV, Dickey BF. Airway mucus function and dysfunction. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(23):2233–2247.

- Shaffer TH, Wolfson MR, Panitch HB. Airway structure, function and development in health and disease. Paediatr Anaesth. 2004;14(1):3–14.

- Castro-Rodriguez JA, Rodriguez-Martinez CE, Sossa-Briceño MP. Principal findings of systematic reviews for the management of acute bronchiolitis in children. Paediatr Respir Rev. 2015;16(4):267–275.

- Mecklin M, Heikkila P, Korppi M. The change in management of bronchiolitis in the intensive care unit between 2000 and 2015. Eur J Pediatr. 2018;177(7):1131.

- Florin TA, Plint AC, Zorc JJ. Viral bronchiolitis. Lancet. 2017;389(10065):211–224.

- Gajdos V, Katsahian S, Beydon N, et al. Effectiveness of chest physiotherapy in infants hospitalized with acute bronchiolitis: a multicenter, randomized, controlled trial. PLoS Med. 2010;7(9):e1000345.

- Lannefors L. Cystic fibrosis – long term results of a treatment package including preventive physical exercise [dissertation]. Lund (Sweden): Lund University; 2010.

- Postiaux G, Zwaenepoel B, Louis J. Chest physical therapy in acute viral bronchiolitis: an updated review. Respir Care. 2013;58(9):1541–1545.

- Gomes EL, Postiaux G, Medeiros DR, et al. Chest physical therapy is effective in reducing the clinical score in bronchiolitis: randomized controlled trial. Rev bras fisioter. 2012;16(3):241–247.

- Rochat I, Leis P, Bouchardy M, et al. Chest physiotherapy using passive expiratory techniques does not reduce bronchiolitis severity: a randomised controlled trial. Eur J Pediatr. 2012;171(3):457–462.

- Roque I Figuls M, Gine-Garriga M, Granados Rugeles C, et al. Chest physiotherapy for acute bronchiolitis in paediatric patients between 0 and 24 months old. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;2:CD004873.

- Gomes GR, Donadio MF. Effects of the use of respiratory physiotherapy in children admitted with acute viral bronchiolitis. Archives de Pédiatrie. 2018;25(6):394.

- Postiaux G, Louis J, Labasse HC, et al. Evaluation of an alternative chest physiotherapy method in infants with respiratory syncytial virus bronchiolitis. Respir Care. 2011;56(7):989–994.

- Giannantonio C, Papacci P, Ciarniello R, et al. Chest physiotherapy in preterm infants with lung diseases. Ital J Pediatr. 2010;36(1):65.

- Kugelman A, Feferkorn I, Riskin A, et al. Nasal intermittent mandatory ventilation versus nasal continuous positive airway pressure for respiratory distress syndrome: a randomized, controlled, prospective study. J Pediatr. 2007;150(5):521–526, 526.e1.

- Milesi C, Matecki S, Jaber S, et al. 6 cmH2O continuous positive airway pressure versus conventional oxygen therapy in severe viral bronchiolitis: a randomized trial. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2013;48(1):45–51.

- Thia LP, McKenzie SA, Blyth TP, et al. Randomised controlled trial of nasal continuous positive airways pressure (CPAP) in bronchiolitis. Arch Dis Child. 2008;93(1):45–47.

- DiDario AG, Whelan MA, Hwan WH, et al. Efficacy of chest physiotherapy in pediatric patients with acute asthma exacerbations. Pediatr Asthma Allergy Immunol. 2009;22(2):69–74.

- Jacinto CP, Gastaldi AC, Aguiar DY, et al. Physical therapy for airway clearance improves cardiac autonomic modulation in children with acute bronchiolitis. Braz J Phys Ther. 2013;17(6):533–540.

- Paludo C, Zhang L, Lincho CS, et al. Chest physical therapy for children hospitalised with acute pneumonia: a randomised controlled trial. Thorax. 2008;63(9):791–794.

- Pupin MK, Riccetto AG, Ribeiro JD, et al. Comparison of the effects that two different respiratory physical therapy techniques have on cardiorespiratory parameters in infants with acute viral bronchiolitis. J Bras Pneumol. 2009;35(9):860–867.

- Lukrafka JL, Fuchs SC, Fischer GB, et al. Chest physiotherapy in paediatric patients hospitalised with community-acquired pneumonia: a randomised clinical trial. Arch Dis Child. 2012;97(11):967–971.

- Fysioterapeuterna. Etiska regler. 2:2 [Internet]. Stockholm: Fysioterapeuterna; 2017. [cited 2019 Aug 16]. Available from: https://www.fysioterapeuterna.se/Profession/Etik-lagar–regler/Etiska-regler/.

- The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Bronchiolitis in children: diagnosis and management. NICE guideline NG9 [Internet]. Manchester: The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence; 2015. [cited 2019 16 August]. Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng9/chapter/1-Recommendations#when-to-admit.

- Djurfeldt G, Larsson R, Stjärnhagen O. Statistisk verktygslåda 1: samhällsvetenskaplig orsaksanalys med kvantitativa metoder. Lund (Sweden): Studentlitteratur; 2010.

- Ejlertsson G, Axelsson J. Enkäten i praktiken: en handbok i enkätmetodik. Lund (Sweden): Studentlitteratur; 2005.

- Trost J. Enkätboken. Lund (Sweden): Studentlitteratur; 2001.

- Lagerkvist A-L. Assessment of chest physiotherapy in children [dissertation]. Göteborg (Sweden): Göteborg University; 2005.

- Lagerkvist A-L. Andningsfunktion. In: Beckung E, Rösblad B, Carlberg EB, editors. Fysioterapi för barn och ungdom: teori och tillämpning. Lund (Sweden): Studentlitteratur; 2013. p. 133–151.

- Nagakumar P, Doull I. Current therapy for bronchiolitis. Arch Dis Child.. 2012;97(9):827.

- Balachandran A, Shivbalan S, Thangavelu S. Chest physiotherapy in pediatric practice. Indian Pediatr. 2005;42(6):559–568.

- Lumb AB. Nunn’s applied respiratory physiology. 8th ed. New York (NY): Elsevier; 2017.

- Dean E. Body positioning In: Frownfelter D, Dean E, editors. Cardiovascular and pulmonary physical therapy: evidence to practice. 5th ed. St. Louis (MO): Elsevier/Mosby; 2013.

- Dennersten U, Lannefors L, Hoglund P, et al. Lung function in the aging Swedish cystic fibrosis population. Respir Med. 2009;103(7):1076–1082.

- Lannefors L. Physical training: vital for survival and quality of life in cystic fibrosis. Breathe. 2012;8(4):308.

- Lannefors L, Button BM, McIlwaine M. Physiotherapy in infants and young children with cystic fibrosis: current practice and future developments. J R Soc Med. 2004;97(Suppl 44):8.

- Andreasson B, Jonson B, Kornfalt R, et al. Long-term effects of physical exercise on working capacity and pulmonary function in cystic fibrosis. Acta Paediatr Scand. 1987;76(1):70–75.

- Postiaux G, Hankard R, Saulnier JP, et al. Chest physical therapy in infant acute viral bronchiolitis: should we really surrender? Archives de pediatrie: organe officiel de la Societe francaise de pediatrie. 2014;21(5):452–453.

- Statistiska Centralbyrån. Folkmängden efter region, civilstånd, ålder och kön. År 1968–2017 [Internet]. Stockholm: Statistiska centralbyrån; 2018. [cited 2018 22 May]. Available from: http://www.statistikdatabasen.scb.se/pxweb/sv/ssd/START__BE__BE0101__BE0101A/BefolkningNy/table/tableViewLayout1/?rxid=f45f90b6-7345-4877-ba25-9b43e6c6e299.

Appendix

Appendix 1

The webb-based survey translated into English.

In which county of Sweden do you work?

In what type of hospital do you mainly work?

What year did you graduate as a physiotherapist?

Where did you graduate as a physiotherapist?

In Sweden

In another Scandinavian country

Outside of Scandinavia

Are you…

Female

Male

Do not define myself as either female or male

How many times did your treat infants (0–24 months) for breathing difficulties in the last 2 years?

Never

1–2 times

3–6 times

More than 6 times

You who answered Never, may now submit the survey by clicking on the send-icon. (No more questions were shown to those who marked Never.)

What treatment methods did you use for infants with breathing difficulties due to for example bronchiolitis?

PEP

CPAP

BilevelPAP

Hi Nasal Flow

Mechanical insufflation-exsufflation

Percussions on the chest

Manual vibrations

Postural drainage

Induced/Provoked cough

Prolonged slow expiration technique, PSET

Light chest compressions

Cough support, chest or abdomen

Resting position

Change of positions in bed

Change of positions in arms

Bouncing on a big ball

Passive arm movements

Passive leg movements

Physical activity

Alternating inhalations with other methods

Improving inhalation technique

Information to parents

Advice to health care providers

Other treatments (please describe in the last question)

When you used the resting position, how was the child placed?

Please write the answer in the textbox.

When you used change of position in arms, in what position was the child placed?

Upright against adult’s shoulder

Side-lying in adult’s arms

Prone in adult’s arms

Supine in adult’s arms

Prone towards adult’s chest (who is semi-recumbent)

Sitting in adult’s knee

Other (please describe in the last question)

When you used change of positions in the bed, in what positions was the child placed?

Side-lying

Rolling from side to side

Prone

Supine

Other (please describe in the last question)

When you used bouncing on a big ball, how was the child placed?

Supine on the ball

Side-lying on the ball

Prone on the ball

Sitting on the ball

Upright against shoulder of an adult’s who sits on the ball

Sitting in adult’s knee on the ball

Side-lying in adult’s arms on the ball

Prone in adult’s arms on the ball

Supine in adult’s arms on the ball

Other (please describe in the last question)

You who marked giving advice to health care providers, what was the advice about?

Current inhalation medicine

Current inhalation devices

Current inhalation technique

Further tests

Further actions (e.g. medical actions or play therapy)

Use of Hi nasal flow, CPAP or BilevelPAP

Other (please describe in the last question)

What are your three most commonly used methods?

PEP

CPAP

BilevelPAP

Hi Nasal Flow

Mechanical insufflation-exsufflation

Percussions on the chest

Manual vibrations

Postural drainage

Induced/Provoked cough

Prolonged slow expiration technique, PSET

Light chest compressions

Cough support, chest or abdomen

Resting position

Change of positions in bed

Change of positions in arms

Bouncing on a big ball

Passive arm and leg movements

Physical activity

Alternating inhalations with other methods

Improving inhalation technique

Information to parents

Advice to health care providers

Other treatments (please describe in the last question)

What effects do you notice immediately in connection to your treatment?

Notice no effect

Improved capillary refill

Increased bloodgases

Improved x-ray image

Increased saturation

Reduced respiratory rate

Reduced work of breathing

Reduced retractions

Reduced heart rate

Increased general condition

Increased food intake

More productive/increased or decreased cough

Changed secretion sounds

Parents report of improved condition

Other effect (please describe in the last question)

You who notice a change in secretion or other breathing sounds, how do you do that?

Listen with my ears

Listen with a stethoscope

Manual palpation around the chest.

What effects do you notice after a little longer time?

Notice no effect

Improved capillary refill

Increased bloodgases

Improved x-ray image

Increased saturation

Reduced respiratory rate

Reduced work of breathing

Reduced retractions

Reduced heart rate

Increased general condition

Increased food intake

More productive/increased or decreased cough

Changed secretion sounds

Parents report of an improved condition

Other effect (please describe in the last question)

If you have any additional answers to the questions or views on the survey, please write them here.