ABSTRACT

Urban politics is a US-dominated field, and since the late 1990s there have been academic discussions with a view, on the one hand, to better understanding the British/European case and what distinguishes it from the US one and, on the other, to develop a better comparative theory much of which subsequently went down the path of studying neoliberalism. This article follows an urban politics perspective and the qualitative case-study method to explore Everton Football Club’s 20-year-long unsuccessful struggle to relocate to a new modern stadium of its own in the Liverpool city-region. Although this paper has limitations stemming from the fact that it is a single case study, its contribution to the field is three-fold. First, it adds to the scant literature on new private sports stadia in the UK. Second, it shows that US-based urban politics theories beyond regimes may remain alive in the UK. Third, it supplements the neoliberalist–financialized city statecraft literature by adding sports stadia as infrastructural projects never before incorporated.

INTRODUCTION

In response to modern consumer and business cultures, new private sports stadia operate as multifunctional spaces that incorporate sports’ grounds, playgrounds, shopping centres, etc., and constitute a key business strategy component for any professional club’s economic survival. For the last two decades, Everton Football Club (FC) has been struggling unsuccessfully to relocate to a new modern stadium of its own in the Liverpool city-region. This paper studies the club’s relocation experience, from an urban politics perspective, for the following reasons. First, and most importantly, the paper seeks to unveil which bodies of urban/regional theory and empirical work can help us understand stadium-projects in the UK, and how in turn the UK experience might contribute to that body of theory. Second, the construction of new stadia requires large, controversial investment projects that involve power relations. Third, the urban politics of private new sports stadia have been studied extensively in the United States, and to a lesser extent in the UK. Lastly, only one of Everton’s relocation attempts has been the focus of relatively recent research, presenting the initiative of an Everton fan club that opposed the club’s plan to move outside of Liverpool as an example of their involvement in the club’s governance (Fitzpatrick, Citation2013; Kennedy, Citation2012).Footnote1

To place the issue in perspective, since the late 1990s there have been academic discussions with a view to a better understanding of the British/European case and what distinguishes it from the US, and to develop a better comparative theory much of which subsequently went down the path of studying neoliberalism. Nevertheless, these academic discussions have been following separate paths.

Starting with neoliberalism, the issues tackled have moved from urban politics to urban finance. Pike et al. (Citation2019) have unveiled the emergence and impacts of contemporary forms of financialization that have been engaging the local authority and its governance and infrastructure since the global financial crisis of the late 2000s. Predominantly, infrastructure is perceived to comprise not only physical artefacts, such as bridges, cables, pipes and roads, but also the processes, resources and services associated with these artefacts.Footnote2 Studies have demonstrated an increase in foreign ownership and control of essential infrastructure systems, as well as the enduring problems of privatization. The urban infrastructure provision for urban activities in cities has become a challenge for local governments in the UK, which have had to become more commercialized and even financialized as they struggle to close funding gaps between income and expenditure under austerity. An instrument used often is the special purpose vehicle (SPV). The instrument acts as a managing and operating company for projects, as well as a legal body that guarantees concessions from the public authority. The SPV is embraced by lenders, financial institutions, public authorities, export credit agencies, guarantors, suppliers and off-takers in the event where equity comes from a prime contractor, service provider or public authority. However, most of the risks assumed to be transferred to the SPV are not managed by the SPV and instead are passed on to its subcontractors. If the public authority provides a loan or subsidy to aid a struggling SPV, there is no guarantee it will be paid back, hence the taxpayer would have to unfairly shoulder the financial burden (Burke & Demirag, Citation2015, Citation2019). Local authorities also behave as financial risk-takers, acting as intermediaries, assuming various types of financial risks to secure required infrastructural projects. Pike et al. (Citation2019) label this phenomenon as the financialized city statecraft model. Fears have been expressed that this model might lead local governments into financial difficulties and possible bankruptcy within the current decade.

Continuing with US urban politics theories and their cross-national applicability, the two most influential urban politics theories, urban regimes and growth machines, have urban regeneration as an epicentre. Regarding urban regimes, Mossberger and Stoker (Citation2001) see them as coalitions drawn from government and non-governmental sources, and their collaboration is based on social production, that is, the need to bring together fragmented resources for the power to accomplish local growth tasks. Besides, their policy agendas are identifiable, and cooperation follows longstanding patterns, not temporary ones. Viewing the city as a ‘growth machine’, Logan and Molotch (Citation1987) propose that various local actors in the city, guided by their disparate interests, form coalitions aimed at supporting single-purpose projects that enhance the exchange value – market value – of land, and thus induce local growth. Therefore, the two theories are not identical. As coalitions, they may face local resistance by other actors opposing their goals. However, whereas urban regimes are long-lived – engaged in governance and the execution of multiple projects – growth machines are short-lived supporting only single-purpose projects.Footnote3 The discussions on the export of these theories to Europe were focused almost exclusively on urban regimes. Scholars have observed the emergence of urban regimes in Europe. Among them are John and Cole (Citation1998), Dowding et al. (Citation1999), Brenner (Citation2009), Holman (Citation2007), Pinson (Citation2002) and Blanco (Citation2015). Interestingly, Blanco’s study demonstrates that the urban regimes theory can help overcome the networks/neoliberalism dualism by showing how different coalitions mobilize different sets of resources over time and in different policy arenas.

Growth machines theory has not received much support for use in the UK. Harding’s (Citation1999) reservations rest mainly on the centralized nature of the British planning system which does not allow locally based rentiers as much scope as in the United States. He recommends, however, that it is worth retaining and building upon the core features of US urban political theories, in the hope of developing a fresh approach to urban coalition formation in Britain. MacLeod and Goodwin (Citation1999) offer critiques on similar grounds. Using the popular English public–private partnerships (PPPs) as an example, they argue that a better theory of local government is required, and that the struggle over the exchange and use values of land must be given more thorough consideration.Footnote4 Wood (Citation2004) has proposed a new concept, the strategic-relational approach, but its empirical application is long overdue. Reassessing the growth machines theory, Cox (Citation2017) has concluded that, although attempts to transfer it across the Atlantic have not been very successful, it remains a guidepost for research in urban studies.

Indeed, researchers continue to rely on this thesis. Recent work uses the growth machines concept as a heuristic tool to analyse how public and private interests, driven by the growth of London, formed a coalition that supported the development of the Crossrail project (Mboumoua, Citation2017).

Following this brief introduction to US-based urban politics theories and the discussions about their export to the UK and other parts of Europe, along with neoliberalist approaches, the remainder of this paper presents the US and UK literature on new private sports stadia and the selected research approach. Before concluding, we briefly follow the case studies on Everton’s four relocation attempts (in chronological order), which offer an in-depth narrative of the urban power relations that have been taking place around Everton’s alternate stadium-project plans since the year 2000.

THE US AND UK LITERATURE ON THE POLITICS OF NEW PRIVATE SPORTS STADIA

Addressing sports stadia as local development projects and relabelling growth machines as local growth coalitions (LGCs), US scholars have developed a solid body of urban theory. LGCs include local governments, land developers and real estate agents, business leaders, financial entities, newspaper owners and other actors, and are formed to promote only single new private sports stadia projects. The commitment of LGCs to urban growth bonds their members together, giving them a hegemonic role over their opponents, who are stakeholders interested in the use-value of the land. For example, heritage preservation activists want the land preserved for its historical significance, while poverty activists prefer to see the land developed in a way that provides affordable housing. This conflict over the exchange versus use values of land provides an understanding of the politics of urban spaces.Footnote5 LGCs do not always prevail, as both internal (e.g., structure, composition) or external (e.g., referenda) factors may determine their success. In their study of LGCs for new private sports stadia projects across the United States, Delaney and Eckstein (Citation2003, Citation2008) distinguish between ‘strong’ and ‘weak’ coalitions depending on whether the media is on their side. They also acknowledge the fact that LGCs may not always reach their targets due to internal and/or external factors. From 1984 to 2000, 40% of LGCs were unsuccessful due to external factors: local referendums (Brown & Paul, Citation2002). Recent literature has revealed that the current US trend is to replace local referenda with decisions more commonly carried out through legislation by elected officials at the municipal, county or state level (Hutchinson et al., Citation2018). Acknowledging variations in the outcomes of battles over stadium construction initiatives, Delaney and Eckstein (Citation2007) maintain that more often than not, the outcome is in favour of the elites, even in the face of significant grassroots resistance. The dominant ideology of these coalitions, ‘local growth for the public good’, is exercised long before the matter surfaces as a political dispute which gives them an advantage. However, it is becoming obsolete and, therefore, it may be more effective to call upon the public’s ‘community self-esteem’ and ‘community collective conscience’ to secure support for a project plan (Eckstein & Delaney, Citation2002). LGCs influence local political processes that favour projects serving essentially private interests (Brown & Paul, Citation2000, Citation2002; Delaney & Eckstein, Citation2003; Friedman et al., Citation2004; Smith & Ingham, Citation2003). Finally, the tremendous costs associated with new sports facilities usually minimize any chance for a positive economic return on these projects (Chapin, Citation2004).

Studying new private sports stadia, UK-based research is scant and has used a variety of lenses. Bale (Citation1990, Citation2000) relied on views about placelessness and Michel Foucault’s notion of the gaze, to describe stadia as safe, sanitized and surveilled modern enclosures that also stand as potential offences to the urban environment and citizens’ quality of life. Davies (Citation2005) used an economic approach to portray new stadia as threats that lead to declining property values, stirring up local opposition. Lately, studying the case of Tottenham Hotspur’s stadium regeneration in the London Borough of Haringey, Panton and Walters (Citation2019) used stakeholder theory to attribute the formation of a local network challenging several factors regarding the stadium’s regeneration, including the perception that locals were being sidelined to accommodate the developers’ plans, the lack of transparency around both the development plans and the focal organizations, the protection of community interests and the lack of salience felt by community stakeholders. Also, fairly recently, using power theory, a study of Arsenal’s Emirates Stadium in the London Borough of Islington examined the power relations between three main non-coalitional actors: Arsenal FC, Islington Borough Council and the Highbury Community Association (Church & Penny, Citation2013). Arsenal requested the council’s approval to acquire at its own cost and demolish the housing complexes along two streets adjacent to its old stadium to increase its capacity. The community association objected to the plan. Two commercial property surveyors proposed an alternative site within the borough, ideal for the construction of a new stadium that fully satisfied all three key actors. The council bought Arsenal’s old stadium and made a land investment, Arsenal relocated to a state-of-the-art stadium and the community association saved the housing complexes around the old stadium. This was a win–win solution compromising the powers of the developers and their opponents.

RESEARCH APPROACH

This paper follows a qualitative case-study research approach, using the narrative format (Yin, Citation2012). Everton’s stadium-project plans have become public issues, hosted on various local and national media websites, as well as fan websites, allowing the collection of useful digital material. Digital media – particularly newspapers, television and radio broadcasts – are a well-known source of valuable documents, and political researchers endorse their consultation (Harrison, Citation2001). We also note that press reports tend to be considered as primary sources (Hazareesingh & Nabulsi, Citation2008). Given the club’s repeated attempts to relocate, the research effort has followed a longitudinal path. We started with Liverpool City’s website, searching for relevant documents and then, using the keywords ‘Everton’s new stadium’ in different time intervals, we located newspaper articles published in the leading local and national press (Liverpool Echo, BBC, The Guardian), as well as three Everton supporter websites, which were characterized by continuity and relevance to the stadium-project plans. We selected our material, making sure that they were referring mainly to the positions and networks of key actors and not issues such as the geography or architecture of each new stadium-project. Given the nature of our data, we closely followed the transparent enquiry method, which is applicable regardless of how the data are employed, for description, narrative or causal inference (Elman et al., Citation2018). The method requires the backing of an author’s claims and data sources by annotated citations hyperlinked to the sources themselves. The most inclusive website, www.keioc.net, included full media coverage, activist records and a systematic collection of all official documents such as council resolutions, public hearings, evaluation reports and relevant government documents. Recently, the site was discontinued and now appears as https://keioc.net.cutestat.com/, offering news only. The other two sites supporting Everton, www.vintagebluekipper.co and www.toffeeweb.com, also host media reports, viewpoints and interviews with key actors. Only the second website is currently in operation. Although we have built a database using records from these websites, we were unable to reference some of them directly. Thus, we crosschecked a large segment of that database via other accessible digital sources eligible for referencing. Finally, in March 2019, to supplement our data sources, we conducted semi-structured interviews with three key local figures: Dave Kelly, senior member, spokesperson and representative of Keeping Everton In Our City (KEIOC), an Everton fan club; Richard Buxton, a local sports journalist; and Richard Kemp, a councillor and head of the opposition in Liverpool City Council (LCC).

EVERTON’S ALTERNATE STADIUM-PROJECT PLANS

Everton’s stadium is situated in Goodison Park, Liverpool, with a current capacity of 41,000. The stadium was built in 1892, so nowadays it is inadequate in many respects. It lacks the capacity and opportunity for expansion, spectator viewing is obstructed, its corporate facilities are well below those of competitor clubs, and concourse facilities are constrained and underprovided. However, irrespective of its many inadequacies, it is the spiritual home for Everton’s fans. Politicians and local elites have always come to Everton’s support. Soon after its foundation, its appeal to Liverpool’s society attracted the patronage of political and business figures, including Conservative MPs, local councillors and officials from the Liverpool Chamber of Commerce, the gas company, among others (Kennedy, Citation2011).

Liverpool is a left-leaning city with local politics dominated by the Labour Party and the Liberal Democrats since the 1970s. The latter were in office between 1998 and 2010 when Labour took over. The current mayor controls the grand majority in the council and labels himself an ‘Everton fan’. Liverpool is also a city benefitting from the commercialization of English football on a global scale and has oriented its local economic development around football to the extent that its visitor economy has become a role model for the rest of the UK (Evans & Norcliffe, Citation2016; McDonough, Citation2016). Beyond television, live consumption remains an essential component in the production of the Premier League, with overseas supporters increasingly viewing matches and even making pilgrimages as football-tourists to watch in person Liverpool’s two major teams, Everton FC and Liverpool FC. Both teams attract tourists from countries including Iceland, Norway and America, while their badges and scarves are popular in China and Japan (Dawkes, Citation2019).

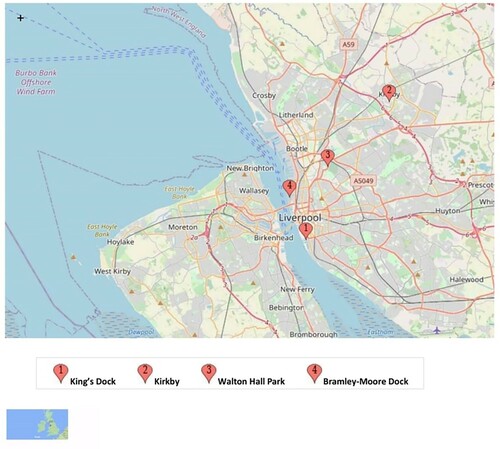

Everton’s unsuccessful relocation attempts began in the year 2000, with a plan to move to King’s Dock, one of Liverpool’s obsolescent waterfront areas. Three years later, in 2003, its second plan involved relocating to Kirkby, a town adjacent to Liverpool with low land prices. The third plan, which began in 2014, involved moving to Walton Hall Park (WHP), a park in north Liverpool. Finally, its current ongoing plan, which was announced in 2018, aims to relocate Everton to a stadium in Bramley-Moore Dock (BMD), another waterfront area owned by a powerful corporation. The King’s Dock and WHP stadium-project plans were short-lived, so their presentation and analysis shall inevitably be shorter too. shows the locations of the four plans.

PROJECT PLAN NO. 1: KING’S DOCK

Like almost every other old industrial port city in the world, the LCC was faced with the desperate problem of developing its obsolescent waterfront areas and found some institutional support. In the 1990s, the government had created three urban regeneration companies, not-for-profit companies limited by guarantee, to draw city regeneration plans (Parkinson & Robson, Citation2000). One of these companies was Liverpool Vision. Beyond public figures, the company’s board included three private business persons, among them Terry Leahy the chair of Tesco, Plc – a multinational chain of supermarkets. Liverpool Vision asked a non-UK consultant to draft a ‘Strategic Regeneration Framework’ that was meant to complement the city’s freshly drawn Unitary Development Plan. The framework included the redevelopment of Liverpool’s waterfront King’s Dock, eligible to draw support funds from the European Union and designated to host an arena and sports facility.

The first round for submission of draft bids by potential developers opened in October 2000 (Toffee, Citation2001). Huston Securities, a company owned by one of Everton’s major shareholders, submitted a bid. In the second round of detailed submissions, in January 2001, Everton submitted a joint bid with the US-based Clear Channel Entertainment, owned by Houston Securities. In July 2001, the bid won the status of ‘preferred bidder’ over six other rivals. Within the next three months, a King’s Waterfront Development Company was established and appointed a prestigious stadium constructor (Pellow, Citation2001). The new stadium’s seating capacity was 55,000 and according to the LCC leader the stadium/arena construction costs alone would be £150 million. The funds were anticipated from various sources, including the European Commission, Houston Securities, English Partnerships, North West Development Agency, LCC and development receipts from non-arena development. The key finance component was the development receipts of £40 million. Houston Securities could add another private partner to fund non-stadium/arena structures, but finally it was Everton that would eventually contribute £30 million from the sale of Goodison Park.

In the end, Everton was unable to raise the required funds. At a meeting of the club’s board in October 2002, the Houston Securities owner presented a plan by which Everton would borrow £30 million for 10 years and would honour the loan by paying back a total of £70 million. Both the board and the club’s fans rejected the plan. Businesses that had stated their intentions to invest in the project began to withdraw their interest. On 31 December 2002, Liverpool Vision decided to end Everton’s status as the ‘preferred developer’ but allowed the club to produce the required funds within a three-month grace period. By April 2003, however, the stadium construction costs had increased by 20% and thus the entire project had to be stalled (BBC, Citation2003). Based on this experience, the council and Liverpool Vision coalition cannot be compared with a US-style LGC. It was, in essence, the desire of the LCC to see a new stadium built for Everton.Footnote6 As Councillor Richard noted:

That project was never an Everton idea. It was mainly a Council idea. At King’s Dock, we were trying to get both teams to have a common ground. Liverpool FC was up for the discussion, but Everton FC was not, due to its bad financial base, until recently when it was acquired by an Iranian billionaire.Footnote7

PROJECT PLAN NO. 2: KIRKBY

In May 2006, the club was contemplating moving to Kirkby, a town four miles outside Liverpool in the adjacent Borough of Knowsley – an undeveloped area with low land prices. Knowsley council offered Everton three prime development sites on which to build its new stadium. At the annual meeting of Everton’s board in early December 2006, its chairman argued that remaining in Goodison Park was no longer an option, and that they were investigating the possibility of working with Knowsley Council and Tesco (Gaunt, Citation2006). A US-style – transient single-purpose – LGC was thus formed, composed of Tesco, Everton FC and Knowsley Council (TEK). The council owned the land on which the new stadium would be built, and Tesco would provide ‘enabling funds’ for the scheme provided that in addition to the stadium it could build a series of new supermarket stores. The allocated land was at the time regarded as worthless, but with planning permission for a Tesco store and shopping complex its value would rise.

All in all, based on their disparate interests, Everton, Tesco and Knowsley had reached an agreement to ‘regenerate’ Kirkby, just as American LGCs do. The mutually beneficial investment project, worth a total of £400 million, would secure 3000 new jobs, a stadium, a new shopping area including a 24-hour Tesco Extra supermarket, 40 individual shops and improvements to the town centre, new leisure facilities, offices and housing. Everton would hold a 99-year lease, meaning that effectively it would ‘own’ the stadium. This project was not a new experience for Tesco, which has supported new sports stadia in the past. It had bought, for example, the old stadium of Wigan Warriors rugby league team and turned it into a car park and had also helped Warrington Wolves rugby league team build a new stadium in 2000 (Slater, Citation2012).

Before filing a formal planning application to the council, the TEK coalition began to take action promoting its plan. Among various actions, on 24 August, Everton sought the support of its fans. They balloted over 36,000 fans, of whom close to 26,000 responded, with 59% of them being supportive of the club’s move to Kirkby (Liverpool Echo, Citation2006). Tesco submitted a planning application to Knowsley Council on 22 November 2007, which was accepted as valid on 2 January 2008 (BBC, Citation2008). However, the application encountered several obstacles, starting with the Knowsley council’s communication of the TEK plan to the Commission for Architecture and the Built Environment (CABE) – a government advisory body. In its report, CABE applauded the council’s efforts to redevelop Kirkby, but deemed that the master plan failed to translate the opportunity into a positive regional transformation (Vaugan, Citation2008). In early April 2008, Knowsley also approached the adjacent council of Sefton. A month or so later, in a report, Sefton’s planning director concluded that the potential impact of this scale of development had not been properly assessed, and therefore the true effect on the vitality and viability of other established centres within the study area had been underestimated. That conclusion was an indication that the Sefton official was against the size of the project’s retail element, which would damage businesses in the adjacent localities (Sefton Council, Citation2008).

Among the plan’s opponents was KEIOC, an Everton fan club. KEIOC wanted Everton to remain in Liverpool. Its arguments were three-pronged. First, the club’s involvement in the specific development scheme was against local, regional and national planning policies. Second, the plan represented a significant risk to the future aspirations of the club, effectively preventing the emergence of alternative proposals. Third, the finances around the stadium appeared flawed. Due to all these departures, the Secretary of State was requested to ‘call-in’ the planning application.Footnote8 One of our interviewees, KEIOC’s spokesperson, revealed that their campaign had received moral support from the LCC:

LCC passed resolution 538. It was me who moved the resolution along with the leader of the council, Ronald Bradley. … I said something along the lines of that I believed it would be an act of municipal vandalism for LCC to allow one of the jewels in the crown of this city to move out of the city boundaries, we’ve got two football clubs and the city council should do everything within its power to do that. That was voted on and it was agreed unanimously that LCC would support the aims and objectives to keep them within the city … they brought another element to the campaign.Footnote9

The TEK coalition’s most powerful opponent, however, was the neighbouring councils of Sefton, Lancashire County, West Lancashire District and St Helens. Sefton council’s head had warned Everton as early as July 2006 not to consider moving to his district (Sefton Council, Citation2008). In North America, actors such as these do interfere with LGCs due to free competition among cities to attract sports clubs and funds.

On 6 August 2008, the Secretary of State ‘called-in’ the Tesco application (Liverpool Echo, Citation2008a). The official inquiry, involving all interested parties, began on 18 November 2008 and closed on 6 February 2009. Before the inquiry, the inspector gave the main contender status only to two groups. One was the five neighbouring councils, which had also campaigned strongly for the plan to be ‘called-in’ by the Secretary of State. They appeared as the combined authority objectors (CAO). The other groups were the Kirkby Residents Action Group (KRAG) and Knowsley’s Constituency Liberal Democrats (KCLD), representing the interests of Knowsley and Kirkby residents who objected to the proposals (e.g., Liverpool Echo, Citation2008b).

The inspector filed her report on 2 July 2009, recommending that the application be rejected (The Independent, Citation2009). Four months later, the Secretary of State agreed and officially informed Tesco that their proposed plan had more minuses than pluses. Based on its scale, the proposed project was in clear conflict with regional spatial strategy and other policies. While mention was also made of the harmful effects on living conditions, the rejection letter emphasized the likely damaging impact on the vitality and viability of Kirkby, Bootle, Skelmersdale and St Helens, plus the fact that it would conflict with policies to support and enhance Liverpool’s city centre. The proposal was not under the retail hierarchy of the subregion. In simple terms, the project would siphon away business from other towns and city centres, violating local shopping policy. Under British law, the Secretary of State’s decision could be challenged by applying to the High Court within six weeks from the date of the letter, but that option was never pursued. Thus, the TEK’s defeat was due to an external factor – the UK’s planning system – even though they had the resources, the support of the local political machine as well as the local media. Any speculations that the LCC might have intervened with the Secretary of State appear to be baseless. Whatever action was taken by the council was only in support of the Kirkby project’s opponents. As our interviewee, Councillor Kemp explained:

It is very difficult to influence the Secretary of State because when he makes planning decisions. He goes into what is called the quasi-judicial situation, and although opinions come out in his name, the decisions are made by planning inspectors, by professionals, and it is very difficult for a national politician to not agree with them.Footnote11

PROJECT PLAN NO. 3: WALTON HALL PARK

Plans for a new stadium at Walton Hall Park (WHP) in north Liverpool were announced in September 2014. A report, carried out by a consulting firm for the LCC, assessed the benefits of the project which could begin in 2017 (Voltera Group, Citation2014). It claimed that the club’s current home could not deliver, compared with other modern stadiums. Also, the 130-acre WHP would benefit from this project and assist in regenerating the local area. The stadium-project could deliver more than 900 new jobs, as well as low-cost housing for over 2000 people. The report did not convince the locals. In December 2014, they began mobilizing against the WHP plan, blaming the LCC for having abandoned their park, and that the project would affect the residents’ quality of life, destroy valuable green space and disrupt wildlife. Lastly, the proposed new jobs would be zero-hour contract, part-time and low-wage jobs. The protesters signed petitions against the plan and managed to become part of a wider ‘political’ coalition including the opposition parties, the Greens and Liberal Democrats, opposing the development of green spaces across the city. shows a group of protesters against the stadium-project.

Figure 2. Protesters against Everton’s Walton Hall Park stadium-project plan.

Source: https://www.liverpoolecho.co.uk/news/liverpool-news/everton-fcs-walton-hall-park-11335603.

More than a year later, with no sign of any progress, Everton’s chief executive officer (CEO) and the mayor exchanged accusations (BBC, Citation2015). As time was passing, the governing elites weighed the political costs of their support of the WHP project. On 16 May 2016, the club and the city announced that they would now be looking elsewhere for a new home for Everton (Murphy, Citation2016). The mayor pledged that WHP would remain a park, and future development there would be prohibited. The two sides also agreed to keep looking for other sites in the city to host the new stadium.

PROJECT PLAN NO. 4: BRAMLEY-MOORE DOCK

Shortly after the abandonment of the WHP plan, in early 2017, Everton’s new plan to build a £300 million stadium at Bramley-Moore Dock (BMD) on the banks of the Mersey River were leaked to the media (BBC, Citation2017). The club and the landowners, Peel Group – formerly known as Peel Holdings – had reached an agreement on the BMD as the preferred site for the stadium. The agreement foresaw a 200-year lease for a nominal rent, allowing Everton to take control of the land in the future. BMD’s owner, Peel, is a company that has been operational quietly acquiring land and real estate, cutting billion-pound deals, and influencing numerous planning decisions across the UK (Shrubsole, Citation2019). The acquisition in 2005 of the Mersey Docks and Harbour Company made Peel the second-largest port group in the UK. Peel’s attempt to raise the international profile of the Liverpool–Manchester urban corridor – the Ocean Gateway – and capitalize on its potential of becoming a globally competitive urban area, was perceived as a sign of the company’s hegemony role in urban and regional planning affairs (Harrison, Citation2014). Second, BMD is part of an area the United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organisation (UNESCO) placed on its World Heritage Site list in 2004 as ‘Liverpool – Maritime Mercantile City’ (Gaillard & Rodwell, Citation2015). Finally, in the field of local political networks, Peel may have supported the mayor’s campaign in the 2012 local elections. Mayor Joe Anderson appears to have won the election on a Peel ticket, promising to create thousands of new jobs and dwellings, something that did not materialize and something the local press never made an issue of (LPT, Citation2015).

The ruling majority in the LCC stood by the club in its dealings with Peel. Adopting the recommendations of an internal report and using the financialized city statecraft mode, the council offered to guarantee the project financially. It agreed to set up an SPV which would help the club borrow the required funds, acting as the guarantor of the loan, but there would be no direct LCC financial outlay towards the project (BBC, Citation2017). The SPV would repay Everton’s loans to its creditors. In return, it would receive repayments (capital plus fees) from the club, having the first call on its revenues from ticket sales, gate receipts, television rights and the so-called ‘parachute payments’. Clubs receive these latter payments when they are relegated from the Premier League so they can get by on lower earnings. The mayor claimed that it was a great deal for taxpayers, as the club would be paying the council about £4.4 million per year as loan security fees. Moreover, according to the report, the new stadium would bring economic benefits to the city, forecast at around £9 million annually. The project would also help the city’s Commonwealth Games bid for either 2022 or 2026. Finally, the club appeared willing to assist in a legacy project that would transform Goodison Park into facilities delivering health, education, affordable housing and public spaces for the community (Jones, Citation2020).

Members of the LCC had doubts and objections. The leader of the largest party in the opposition made it clear that although he was not against the deal, he demanded information on the plan’s safeguards and how it would benefit the council, wondering why Everton’s billionaire owner needed a guarantee from a third party. Local citizens also objected to the mayor’s proposal. shows a petition filed with the UK Parliament.

Plans were stalled for several months. As Richard Buxton reckoned, the mayor’s proposal did not survive because:

essentially it could be privately funded. Also, because the Labour council were quite conscious of the backlash. This city is split into two sides. Liverpool and Everton, and a lot of Liverpool fans were not happy with the idea that their council tax would be going to fund Everton’s stadium. So that was a factor.Footnote12

The context set for the mayor’s decision appears to be the continued withdrawal of financial support for the council over the years, which has effectively boxed him into deals like this, in lieu also of Peel’s hegemonic financial power position. If the council were to fund the whole deal, it would mean borrowing from PWLB, building and owning the ground and then leasing it to the club. That option could lead to a 6% increase in council tax (Houghton, Citation2018). If the money were to be reloaned to Everton, the council would face an unpredictable loan repayment risk. The plan left many wondering about the risks to the city. For a cash-strapped council, the mayor’s logic was indeed astounding. From 2013 to 2018, the council’s gross expenditure exceeded gross income, with its reported net worth following a descending path (LCC, Citation2019a). More importantly, the council’s statement of accounts for 2018–19 read, ‘beyond the period of the current 3-year budget to 2020/21 and future years, the financial position for the city council is unclear’ (LCC, Citation2019b, p. 14). Also, the council’s medium-term financial plan (MTFP) itself identifies several problems that could severely endanger the council’s financial position in the ensuing years. The problems included increasing demand for adult health and social care budgets due to an ageing population; the need to maintain funding of future capital and investment that are strictly dependent on the ability of the council to generate income; and the likelihood of an economic downturn or a reduction in welfare support funding, which would increase deprivation levels in the city.

The plan received criticism from the opposition and even from members of the city’s Labour Party (Bona, Citation2018). The leader of the opposition expressed his fears, revealing his conditional support:

First, while Everton’s majority shareholder appears to be from the Mid-East, rumours say the money is Russian. As an outsider, he might just ‘abandon the train’ anytime without warning. Second, most of Everton’s fans believe that the public sector should not be putting any money into the project because Everton is a private business. Third, investors do not buy a football team for a purpose other than making profits. Finally, the cost of construction was originally estimated to be £300 m and now it has risen to £500 m. The city would certainly benefit from developing north Liverpool, but the Council should resort to building infrastructures there excluding the stadium. Someone said to me, ‘Richard, the stadium will cost £500 m. Should the city council be putting in a quarter of that as an investment?’ My answer is that I might be quite prepared to support that.Footnote13

More than a year following his proposals, in the May 2019 local elections, Liverpool’s mayor surprisingly saw his party’s vote drop by about 5%, and Everton’s majority shareholder announced that the club was expecting a loan of £350 million from the private market, confirming that he would be putting his own money into the project (Jones, Citation2019). In mid-October 2019, the mayor experienced his second surprise when the government announced that HM Treasury had suddenly increased the interest rate on borrowing from the PWLB by 1%, news that shocked town halls across the country (Thorp, Citation2019). In November 2019, the mayor openly expressed his support for Everton’s plan once again when the club revealed the results of its public consultation, according to which 96% of 43,000 citizens supported the BMD project (Jensen, Citation2019). Around the same time, however, the head of the city’s steering group revealed that the city’s need for economic growth and regeneration was incompatible with some of UNESCO’s World Heritage rules, adding that ‘what will be will be’ (Houghton, Citation2019). In the face of the club’s previous experiences and its current hurdles, it remains to be seen if and when the BMD project will indeed materialize. One thing is now certain: our assessments proved to be correct. PWLB’s recent loan rate hike and the dire state of council finances due to Covid-19 have annihilated the mayor’s plans. So, while the council might pay for some infrastructure work around the scheme, it shall be neither an investor nor a creditor of the project.Footnote14 The LCC will consider a revised planning application and furnish its final decision in late March 2021 for a 52,888-seater stadium worth £500 million with funding from the private sector rather than the LCC. The stadium is expected to start operating for the 2024/25 campaign (Jones, Citation2021).

CONCLUSIONS

The aim of this paper was to unveil which bodies of urban/regional theory and empirical work can help us understand stadium-projects in the UK, and how in turn the UK experience might contribute to that body of theory. Following Harding (Citation1999) and Cox (Citation2017), we used the growth machines theory as a point of departure in search of evidence, which is mixed yet interesting. The King’s Dock and WHP projects were short-lived and pose little interest from a theoretical point of view. The former was a unilateral, unfortunate and poorly planned project on behalf of the LCC. Everton as a private business simply failed to produce its share of funds needed for the new stadium. The latter resembles Bale’s (Citation1990, Citation2000) view on stadia using theories about placelessness, and Foucault’s notion of the gaze.

In the Kirkby plan case, the new stadium-project was unequivocally the target of an American-style LGC. The TEK coalition had an internal structure, motives to enhance the exchange-value of the land around Kirkby, and the dominant ideology of a private stadium for the ‘public good’. Besides, it was a ‘strong’ coalition by the Delaney and Eckstein (Citation2008) standards, even given the support of the local media. Naturally, there are differences. The most powerful force opposing the project was not the residents mobilizing to protect an anticipated decline in the use-value of Kirkby’s land. The major opposing forces were the councils of the adjacent localities, which reacted against the plan, as politically accountable representatives of their residents. More importantly, as a result of this opposition, an external factor – the quasi-judicial review by the Secretary of State – finally made the plan impotent. TEK’s ineffectiveness does not necessarily render it any different from LGCs operating in the United States. Not all LGCs have been successful there, as shown by Brown and Paul (Citation2002), and TEK’s failure had nothing to do with its internal organizational composition.

The current ongoing BMD plan is unveiling new forms of local authority involvement in urban governance as regards urban regeneration via new private stadia construction projects. The support of the local authority for BMD has been material and relatively novel, in a neoliberalist-financialized city statecraft mode. Joe Anderson’s original proposal for an SPV was problematic, and that is why the council did not approve it. Although the council would make interest/security fees on the annual loan repayments by Everton to the SPV, its participation would involve taking on significant risk. Failure by Everton to meet its loan obligations could have effectively involved the taxpayer taking on that risk. What if Everton could not meet the annual loan repayments to the SPV? The loan repayment guarantees proposed by Everton were matchday revenue, television rights, etc. If cash flow were poor, would the council bail out Everton or extend the terms of the loan? So, there was risk involved, with the council acting as a guarantor in an unknown landscape (Burke & Demirag, Citation2019). Acting as a direct creditor after borrowing first from the PWLB, the LCC would have been the main broker. The mayor’s precarious actions, and even the statement by the head of the opposition, namely his readiness to vote in support of the council’s assumption of a partial investment towards the stadium, indicates the willingness of local politicians to spend ‘public money for private projects’. The mayor and his Labour Party council seem to have ignored the LCC’s possible entrance into uncharted waters, with a patent possibility of once again transferring its financial risks to local citizens in the form of new taxes or reduced social service provision, that is, subsidizing Everton’s stadium indirectly. This evidence appears to signify the entrance of the local authority into the financial risk-taking channel that might lead to financial problems and bankruptcy as suggested by Pike et al. (Citation2019).

To sum up, this paper is only about one UK football club and thus has limitations. However, it is not the only one of its kind and its contribution is notable. First, it adds to the scant literature on new private sports stadia in the UK. Second, it shows that US-based urban politics theories and specifically growth machines remain alive in the UK. Finally, it supplements the neoliberalist financialized city statecraft literature by adding the case of sports stadia as infrastructural projects, never before incorporated.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors express their gratitude to the Editor-in-Chief and the Editor of Regional Studies-Regional Science, Drs Stephen Hincks and Jen Nelles respectively of the University of Sheffield, for expediting the review process, as well as for selecting two meticulous anonymous reviewers. They thank these reviewers for their very constructive comments. The authors also thank Dr Timothy Chapin of Florida State University, Dr Costas Spirou of Georgia College & State University, Dr Andy Pike of the University of Newcastle upon Tyne, Dr Kevin Cox of Ohio State University, Dr James M. Smith of Indiana University, South Bend, Dr Andrew Wood of the University of Kentucky, and Dr Richard Bourke of Ireland's Waterfront Institute of Technology, who read earlier drafts and offered valuable guidance. Special thanks to the interviewees, Liverpool City Councillor Richard Kemp, KEIOC representative Dave Kelly, and local sports journalist Richard Buxton for their information and time. Finally, the authors acknowledge the generous financial support of the Special Account for Research Funds of the University of Crete (SARF UoC),Greece in making this work open access. The usual disclaimer applies.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Notes

1 Everton’s same attempt will be part of this paper from an urban politics perspective.

2 Pike et al. do not incorporate new private sports stadia as parts of that infrastructure.

3 Often, reference to growth machines can be confusing. For instance, Storper and Scott (Citation2016, p. 1117) note: ‘Urban governance arrangements, too, or what Molotch … called the urban ‘growth machine’ are in significant ways caught up in these frictions through their functions as suppliers of public goods … .’

4 In a PPP, the financing of a project is assumed by the private sector at its own risk, with the built structure remaining in public ownership.

5 David Harvey’s (e.g., Harvey, Citation2014) work has no bearing here, because Molotch’s exchange and use values were not borrowed from Marxian theories. Harvey’s work has inspired the research oh Obrien and Pike (2019) on city-deals.

6 Liverpool Vision was a tool used by the council. Two years ago, it was dissolved and transferred to the council’s administrative apparatus.

7 Interview between the Councillor Richard Kemp and the authors, 30 March 2019.

8 See Smith (Citation2016) on the call-in process.

9 Interview between the KEIOC official Dave Kelly and the authors, 28 March 2019.

10 Information in our original data set that is not reproducible. However, we learnt that Everton had threatened to take legal action against KEIOC because it had criticized its survey as ‘unfair’ (Liverpool Echo, Citation2008c).

11 Interview between Kemp and the authors, 30 March 2019.

12 Interview between the sports journalist Richard Buxton and the authors, 28 March 2019.

13 Interview between Kemp and the authors, 30 March 2019.

14 Personal communication with Kemp.

REFERENCES

- Bale, J. (1990). In the shadow of the stadium: Football grounds as urban nuisances. Geography (Sheffield), 75(4), 325–334.

- Bale, J. (2000). The changing face of football: Stadiums and communities. Soccer & Society, 1(1), 91–101. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/14660970008721251

- BBC. (2003). Everton fail in King’s Dock bid. http://news.bbc.co.uk/sport2/hi/football/teams/e/everton/2940481.stm

- BBC. (2008). Everton submit new stadium plans. http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/uk_news/england/merseyside/7168024.stm

- BBC. (2015). Everton blames Walton Hall Park delay on Liverpool council. https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-england-merseyside-34908063

- BBC. (2017). Liverpool City Council formally backs Everton stadium financing deal. https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-england-merseyside-39386164

- BBC. (2019). Fresh concerns over Liverpool’s World Heritage status. https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-england-merseyside-48787668

- Blanco, I. (2015). Between democratic network governance and neoliberalism: A regime-theoretical analysis of collaboration in Barcelona. Cities, 44, 123–130. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2014.10.007

- Bona, E. (2018). Mayor Anderson under fire for hinting council could fund Everton’s entire stadium. https://www.liverpoolecho.co.uk/news/liverpool-news/mayor-anderson-under-fire-hinting-14505810

- Brady, D. (2018). PWLB loans rise as councils try to shore up financial futures. https://www.publicfinance.co.uk/news/2018/08/pwlb-loans-rise-councils-try-shore-financial-futures

- Brenner, N. (2009). Cities and territorial competitiveness. In C. Rumford (Ed.), The Sage handbook of European studies (pp. 442–463). Sage.

- Brown, C., & Paul, D. M. (2000). The campaign by Cincinnati business interests for strong mayors and sports stadia. The Social Science Journal, 37(2), 161–177. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/S0362-3319(00)00053-7

- Brown, C., & Paul, D. M. (2002). The political scoreboard of professional sport facility referendums in the United States, 1984–2000. Journal of Sport and Social Issues, 26(3), 248–267. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0193723502263003

- Burke, R., & Demirag, I. (2019). Risk management by SPV partners in toll road public private partnerships. Public Management Review, 21(5), 711–731.

- Burke, R., & Demirag, I. (2015). Changing perceptions on PPP games: Demand risk in Irish roads. Critical Perspectives on Accounting, 27, 189–208.

- Chapin, T. S. (2004). Sports facilities as urban redevelopment catalysts: Baltimore’s Camden Yards and Cleveland’s Gateway. Journal of the American Planning Association, 70(2), 193–209. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/01944360408976370

- Church, P., & Penny, S. (2013). Power, space and the new stadium: The example of Arsenal Football Club. Sport in Society, 16(6), 819–834. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/17430437.2013.790888

- Cox, K. R. (2017). Revisiting ‘the city as a growth machine’. Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society, 10(3), 391–405. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/cjres/rsx011

- Davies, L. E. (2005). Not in my back yard! sports stadia location and the property market. Area, 37(3), 268–276. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-4762.2005.00630.x

- Dawkes, P. (2019). Football tourism – Why it’s not just half and half scarves. https://www.bbc.com/sport/football/49920019

- Delaney, K. J., & Eckstein, R. (2003). Public dollars, private stadiums: The battle over building sports stadiums. Rutgers University Press.

- Delaney, K. J., & Eckstein, R. (2007). Urban power structures and publicly financed stadiums. Sociological Forum, 22(3), 331–353. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1573-7861.2007.00022.x

- Delaney, K. J., & Eckstein, R. (2008). Local media coverage of sports stadium initiatives. Journal of Sport and Social Issues, 32(1), 72–93. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0193723507311674

- Dowding, K., Dunleavy, P., King, D., Marketts, H., & Ridin, Y. (1999). Regime politics in London local government. Urban Affairs Review, 34(4), 515–545. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/10780879922184068

- Eckstein, R., & Delaney, K. J. (2002). New sports stadiums, community self-esteem, and community collective conscience. Journal of Sport & Social Issues, 26(3), 235–247.

- Elman, C., Kapiszewski, D., & Lupia, A. (2018). Transparent social inquiry: Implications for political science. Annual Review of Political Science, 21(1), 29–47. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-polisci-091515-025429

- Evans, D., & Norcliffe, G. (2016). Local identities in a global game: The social production of football space in Liverpool. Journal of Sport & Tourism, 20(3–4), 217–232. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/14775085.2016.1231621

- Fitzpatrick, C. (2013). The struggle for grassroots involvement in football club governance: Experiences of a supporter-activist. Soccer & Society, 14(2), 201–214. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/14660970.2013.776468

- Friedman, M. T., Andrews, D. L., & Silk, M. L. (2004). Sport and the facade of redevelopment in the postindustrial city. Sociology of Sport Journal, 21, 119–139.

- Gaillard, B., & Rodwell, D. (2015). A failure of process? Comprehending the issues fostering Heritage conflict in Dresden Elbe Valley and Liverpool – Maritime mercantile city World Heritage sites. The Historic Environment: Policy & Practice, 6(1), 16–40. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1179/1756750515Z.00000000066

- Gaunt, K. (2006). Everton reveal stadium move talks. http://www.independent.co.uk/sport/football/news-and-comment/everton-reveal-stadium-move-talks-428139.html

- Harding, A. (1999). Review article: North urban political economy, urban theory and British research. British Journal of Political Science, 29(4), 673–698. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123499000320

- Harrison, L. (2001). Political research: An introduction. Routledge.

- Harrison, J. (2014). Rethinking city-regionalism as the production of new non-state spatial strategies: The case of Peel Holdings Atlantic Gateway strategy. Urban Studies, 51(11), 2315–2335. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098013493481

- Harvey, D. (2014). Seventeen contradictions and the end of capitalism. Oxford University Press.

- Hazareesingh, S., & Nabulsi, K. (2008). Using archival sources to theorize about politics. In D. Leopold & M. Stears (Eds.), Political theory methods and approaches (pp. 150–170). Oxford University Press.

- Holman, N. (2007). Following the signs: Applying urban regime analysis to a UK case study. Journal of Urban Affairs, 29(5), 435–453. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9906.2007.00359.x

- Houghton, A. (2018). Mayor Joe Anderson hints council could fund entire £500 m Everton stadium deal. https://www.liverpoolecho.co.uk/news/liverpool-news/mayor-joe-hints-council-could-14501578

- Houghton, A. (2019). Liverpool ‘may not get there’ in fight to retain UNESCO World Heritage status, steering group chief admits. https://www.business-live.co.uk/economic-development/liverpool-may-not-there-fight-17215029

- Hutchinson, M., Berg, B. K., & Kellison, T. B. (2018). Political activity in escalation of commitment: Sport facility funding and government decision making in the United States. Sport Management Review, 21(3), 263–278. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smr.2017.07.005

- Jensen, C. F. (2019). ‘A huge vote of confidence’: Massive public support for Everton’s stadium plans. https://offthepitch.com/a/massive-public-support-evertons-stadium-plans

- John, P., & Cole, A. (1998). Urban regimes and local governance in Britain and France: Policy adoption and coordination in Leeds and Lille. Urban Affairs Review, 33(3), 382–404. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/107808749803300307

- Jones, A. (2019). Everything we know so far on Everton’s new stadium and what next for Bramley-Moore dock. https://www.liverpoolecho.co.uk/sport/football/football-news/everton-new-stadium-bramley-moore-15841356

- Jones, A. (2020). Everton submit outline planning application for Goodison Park legacy project. https://www.liverpoolecho.co.uk/sport/football/football-news/everton-submit-outline-planning-application-18057272

- Jones, A. (2021). Everton new stadium plan recommended for approval by Liverpool City Council. https://www.liverpoolecho.co.uk/sport/football/football-news/everton-new-stadium-plans-breaking-19843173

- Kennedy, D. (2011). In the beginning God created Everton … . Soccer & Society, 12(4), 481–490. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/14660970.2011.593787

- Kennedy, D. (2012). Football stadium relocation and the commodification of football: The case of Everton supporters and their adoption of the language of commerce. Soccer & Society, 13(3), 341–358. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/14660970.2012.655504

- Liverpool City Council (LCC). (2019a). Statement of accounts library. https://liverpool.gov.uk/council/budgets-and-finance/statement-of-accounts/

- Liverpool City Council (LCC). (2019b). Statement of accounts 2018/19. https://liverpool.gov.uk/media/1358131/statement-of-accounts-2018-19.pdf

- Liverpool Echo. (2006). Exclusive: Everton fans vote yes to Kirkby. https://www.liverpoolecho.co.uk/news/liverpool-news/exclusive-everton-fans-vote-yes-3506578

- Liverpool Echo. (2008a). Everton FC Kirkby stadium plan called in for public inquiry, https://www.liverpoolecho.co.uk/sport/football/football-news/everton-fc-kirkby-stadium-plan-3478177

- Liverpool Echo. (2008b). Kirkby residents plan poll battle over Everton stadium bid. https://www.liverpoolecho.co.uk/news/liverpool-news/kirkby-residents-plan-poll-battle-3491229

- Liverpool Echo. (2008c). Everton FC have threatened to sue a fans’ group over claims made on its website. https://www.liverpoolecho.co.uk/news/liverpool-news/everton-threaten-sue-fans-group-3487691

- Liverpool Preservation Trust (LPT). (2015). Where are the 20,000 jobs that Joe Anderson and Peel Holdings promised? http://liverpoolpreservationtrust.blogspot.com/2015/02/where-are-20000-jobs-that-joe-anderson.html

- Logan, J., & Molotch, H. (1987). Urban fortunes: The political economy of place. University of California Press.

- MacLeod, G., & Goodwin, M. (1999). Space, scale and state strategy: Rethinking urban and regional governance. Progress in Human Geography, 23(4), 503–527. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1191/030913299669861026

- Mboumoua, I. (2017). Revisiting the growth coalition concept to analyse the success of the Crossrail London megaproject. European Planning Studies, 25(2), 314–331. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2016.1272547

- McDonough, T. (2016). UK’s tourism chief says Liverpool’s visitor economy is now a model for the rest to follow. https://www.liverpoolecho.co.uk/news/business/uks-tourism-chief-says-liverpools-10979518

- Mossberger, K., & Stoker, G. (2001). The evolution of urban regime theory: The challenge of conceptualization. Urban Affairs Review, 36(6), 810–835. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/10780870122185109

- Murphy, L. (2016). Everton FC’s Walton Hall Park stadium plans abandoned. https://www.liverpoolecho.co.uk/news/liverpool-news/everton-fcs-walton-hall-park-11335603

- NW Place. (2009). Secretary of state rejects Everton and Tesco stadium plans. https://www.placenorthwest.co.uk/news/secretary-of-state-rejects-everton-and-tesco-stadium-plans/

- Panton, M., & Walters, G. (2019). Stakeholder mobilisation and sports stadium regeneration: Antecedent factors underpinning the formation of the Our Tottenham community network. European Sport Management Quarterly, 19(1), 102–119. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/16184742.2018.1524505

- Parkinson, M., & Robson, B. (2000). Urban regeneration companies: A process evaluation. Department of the Environment, Transport and the Regions.

- Pellow, P. (2001). Preferred Bidder. https://www.toffeeweb.com/club/kings-dock/pref-bidder.asp

- Pike, A., O’Brien, P., Strickland, T., & Tomaney, J. (2019). Financialising city statecraft and infrastructure. Edward Elgar.

- Pinson, G. (2002). Political government and governance: Strategic planning and the reshaping of political capacity in Turin. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 26(3), 477–493.

- Sefton Council. (2008). Report to planning committee, date 4th June 2008. http://modgov.sefton.gov.uk/moderngov/documents/s1216/Kirkby%20report%20final%2023-05-08.pdf

- Shrubsole, G. (2019). Who owns the country? The secretive companies hoarding England’s land. https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2019/apr/19/who-owns-england-secretive-companies-hoarding-land

- Slater, G. (2012). The Warrington Wolves miscellany. The History Press.

- Smith, J. M., & Ingham, A. G. (2003). On the waterfront: Retrospectives on the relationship between sport and communities. Sociology of Sport Journal, 20, 252–274.

- Smith, L. (2016). Calling-in applications. Briefing paper No. 00930. House of Commons Library. www.parliament.uk/commons-library intranet.parliament.uk/commons-library

- Storper, M., & Scott, A. J. (2016). Current debates in urban theory: A critical assessment. Urban Studies, 53(6), 1114–1136. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098016634002

- The Independent. (2009). Rejection of Everton stadium plans confirmed. https://www.independent.co.uk/sport/football/premier-league/rejection-of-everton-stadium-plans-confirmed-1827934.html

- Thorp, L. (2019). Where things currently stand with Everton’s new stadium and Liverpool Council. //www.liverpoolecho.co.uk/news/liverpool-news/things-currently-stand-evertons-new-17102953

- Toffee Web. (2001). New Stadium. https://www.toffeeweb.com/club/kings-dock/new-stadium.asp#current

- Vaugan, R. (2008). CABE raises fears over new Everton stadium. https://www.architectsjournal.co.uk/news/cabe-raises-fears-over-new-everton-stadium

- Voltera Group. (2014). Outline feasibility report – Walton Hall Park. https://www.liverpoolexpress.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2014/11/VolterraRegenerationReport.pdf

- Wood, A. M. (2004). Domesticating urban theory? US concepts, British cities and the limits of cross-national applications. Urban Studies, 41(11), 2103–2118. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/0042098042000268366

- Yin, R. K. (2012). Applications of case study research. Sage.