?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

This paper explores the link between globalization and internal mobility in Vietnam. We find that Vietnam’s internationalization processes have an asymmetric economic impact on the provinces. Using data on inter-provincial migration flows, we show that this asymmetry is also detectable in terms of differences in the levels of provincial attraction vis-à-vis internal migration. In particular, provinces receiving higher foreign direct investment are found to be the most attractive for internal migrants. The existence of a pull-through effect associated with migrant networks also emerges in our findings. Overall, the results corroborate the idea that globalization processes are key determinants of internal migration flows.

1. INTRODUCTION

Since the Second World War internationalization processes have represented significant drivers of economic development within Asian countries. Starting with Japan’s economic miracle in the late 1950s and the subsequent emergence of the ‘Asian Tigers’ in the 1970s, the economies of Asian countries have gradually grown and consolidated. With the exception of China and India, which merit separate discussion due to their exclusive characteristics, other Asian countries (e.g., Thailand, Malaysia, Philippines and, recently, Indonesia and Vietnam) have undergone a progressive liberalization of trade over recent decades, with many entering the World Trade Organization (WTO). Despite their diversity, these countries have all experienced significant acceleration in economic development by following export-led policies and opening up to foreign direct investment (FDI), as well as by engaging in selective import control measures and steering internal transformations. The rapid pace of growth has led to dramatic demographic imbalances, accompanied by significant internal movement.Footnote1 In many countries, demographic relocations have been predominantly rural–urban, following economic development trajectories that are mostly polarized towards the largest cities, which are the preferred destination for FDI.

The present study focuses on the case of Vietnam – a country emblematic of globalization-driven development and significant internal migration. On the one hand, the processes of progressive openness to international trade and inclusion in global value chains through massive FDI inflows have been decisive in fuelling Vietnam’s rapid economic growth in recent decades, with positive repercussions in terms of poverty alleviation. On the other hand, this development pattern has not been uniform but characterized by spatial concentration of production activities triggered by foreign capital and industrial polarization. In this context of territorially asymmetric effects of globalization, this study investigates the link between FDI and inter-provincial mobility in Vietnam, contributing to enrich the analysis of the determinants of internal migration.

In particular, the study addresses the following research questions:

To what extent does globalization impact internal migration flows in Vietnam?

How does globalization interplay with other determinants of internal migration in the country?

The study aligns with the literature on the macroeconomic determinants of internal migration flows (Massey et al., Citation1993). To the best of our knowledge, it represents the first exploration of the role of FDI in determining internal mobility in Vietnam. From a methodological perspective, the use of different econometric specifications (including quantile regressions and the generalized method of moments (GMM) estimator) enables us to achieve robust results and conduct a dynamic investigation of the pull-through effect linked to migrant networks, as evidenced in the literature (Beine & Salomone, Citation2013; Boyd, Citation1989).Footnote2

The remainder of the paper is structured as follows. Section 2 discusses the determinants of internal migration from both a theoretical and an empirical perspective. Section 3 builds the research hypotheses, stemming from an overview of internal mobility and globalization in Vietnam. Section 4 presents the methodology by describing the econometric strategy. Section 5 reports and discusses the results. Finally, Section 6 provides some concluding remarks.

2. THE DETERMINANTS OF INTERNAL MIGRATION

A vast literature on the economic determinants of international migration has explored the fundamental mechanisms underlying decisions to migrate. From a theoretical perspective, the first explanations of international migration developed according to standard neoclassical models of economic growth, including both macro- and microeconomic approaches (Massey et al., Citation1993). According to the neoclassical macroeconomic angle, international mobility is caused by geographical differences in labour supply and demand, whereby international wage differentials encourage labourers from low-wage (i.e., labour abundant, capital poor) countries to move to high-wage (i.e., labour poor, capital abundant) countries. The migration of workers stops when wage equalization is achieved – or, more precisely, when the wage differential reflects only the costs of international movement (equilibrium). According to the neoclassical microeconomic perspective, individuals migrate because they expect a positive net return: according to a cost–benefit analysis, they choose a location associated with the maximum net benefit from migration (Borjas, Citation1990; Greenwood, Citation1975).

Relative to the macroeconomic approach, which is based essentially on wage differentials, the microeconomic approach involves a richer set of variables and allows for a more nuanced conceptual framework considering: (1) international differentials in employment rates, besides earnings; (2) individual human capital characteristics that could increase the probability of employment in the destination country relative to the origin country; (3) individual, social and technological conditions that could lower migration costs and increase the likelihood of migration; (4) different attitudes to migration of individuals within the same country; and (5) understandings of migration that view it as an investment decision (Sjaastad, Citation1962). More recently, alternative approaches to the economics of migration have challenged the hypotheses and results of the neoclassical perspective. Departing from the standard neoclassical framework, contributions that fall under the ‘new economics of migration’ (Massey et al., Citation1993) tend to consider households (rather than individuals) the key entities that take decisions about migration: unlike isolated individuals, households can allocate their human resources to local and/or foreign labour markets in order to diversify risks associated with unemployment or income deterioration (Stark, Citation1991). Furthermore, the new approach recognizes that the incentive to migrate may exist even in the absence of wage differentials, assuming that changes in income distribution occur. In other words, relative and not absolute income is the crucial factor affecting the likelihood of migration: if changes in income distribution increase the relative deprivation of some households with respect to others, then those households will be encouraged to migrate (Stark & Taylor, Citation1989).

In general, even in the absence of wage differentials, incentives to migrate may persist due to market failures that limit domestic income opportunities (e.g., inefficient capital markets, incomplete unemployment insurance systems), especially in poor countries. The presence/absence of social networks is an additional factor affecting mobility. That is, an individual’s decision to move to a particular destination may be positively affected by the existence of a group of people from his/her community (or country) in that destination. This social network of compatriots can help the migrant to find work and housing, and mitigate feelings of alienation in the new setting. In some ways, however, social networks are only second-order drivers of migration, as the first-order drivers are the factors that motivated the earlier migrants’ (i.e., those in the established network) decision to migrate (Lucas, Citation2015). Additionally, the presence/absence of social networks in the place of origin may also impact the decision to migrate. According to Munshi and Rosenzweig (Citation2013), the decision to migrate involves a consideration of the trade-off between the income gains associated with mobility and the risk of leaving home (and social networks).

From an empirical perspective, the literature identifies (sometimes without a consistent underlying theory) several push and pull factors determining migration. Commonly, push factors are represented by a high rate of unemployment in a source region and/or job loss (Fidrmuc, Citation2004). Among the pull factors, high wage levels are among the most important (e.g., Liu & Shen, Citation2014). In general, the empirical research in this area has focused on wage gaps, differentials in unemployment rates and distance as factors determining willingness to migrate (Borjas, Citation2019; Jandová & Paleta, Citation2015), both internationally and internally. To disentangle the different motivations and aspects of internal mobility from those of international migration,Footnote3 we must shift focus away from some factors, such as language ability and legal systems, toward individual and labour force characteristics, such as skills (Borjas et al., Citation1992), risk aversion (World Bank, Citation2009), home ownership (Oswald, Citation1996, Citation2019), preferences for local amenities (Chen & Rosenthal, Citation2008; Treyz et al., Citation1993), age, sex and family status (Dennett & Stillwell, Citation2008). These socio-demographic variables are important incentives for internal migration, with an equal (or in some cases greater) impact on migration as the economic factors described above.Footnote4

However, most studies that have detected such explanatory factors of internal migration have mainly focused on developed countries such as the United States, Canada, the UK, France and Germany (Greenwood, Citation1997). In contrast, research on internal migration in less developed countries has embraced a different perspective, oriented towards the exploration of rural–urban migration (Lucas, Citation2015; Stark, Citation1991; Todaro, Citation1976). In the case of China, for instance, research has documented the migration of a very large number of Chinese people from rural inland territories to coastal cities over the last three decades, to pursue job opportunities created by FDI (Chan, Citation2013; The Economist, Citation2012).Footnote5 Similarly, in other less developed Asian countries, a high proportion of the population has been shown to engage in internal migration, and especially rural–urban migration (or rural–rural migration in predominantly rural societies). In Cambodia, for instance, the National Institute of Statistics estimated that in 2013 nearly one-quarter of the population changed their location of residence (United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), Citation2018). Low productivity in agriculture (also due to climate change) and high rates of poverty in rural areas were the main push factors underlying Cambodian rural–urban (and rural–rural) internal migration. The country’s particularly poor economic conditions may explain why the push factor represented by poverty overwhelmed the pull factors of internal migration; however, other Asian countries (e.g., China, as previously described) show a different picture. In Indonesia, for example, inter-provincial mobility has mainly been driven by economic opportunities provided by primate cities, such as Jakarta (Van Lottum & Marks, Citation2012). If in the first half of the 20th century Dutch plantations on the Outer Islands represented the main explanatory factor of inter-provincial mobility in Indonesia (Van Lottum & Marks, Citation2012),Footnote6 in recent years the concentration of Chinese, Singaporean, Japanese and Hong Kong FDI in Java – especially in infrastructure and housing (BKPM, Citation2019) – has played a more important role in influencing patterns of internal migration.

In quickly developing countries such as Thailand and Vietnam, internationalization processes may have also contributed to shaping internal migration patterns.Footnote7 However, focusing on the main drivers of internal mobility in developing countries, some authors have questioned the standard distinction between push and pull factors. In this regard, Lucas (Citation2015, p. 6) remarked:

The common distinction between push and pull factors driving migration is misplaced; private decisions to move or stay are driven by the differentials in opportunities across locations. … . In turn, more fundamental forces shape some of these proximate causes, representing deeper elements driving population movements.

Lucas listed 10 drivers of migration in developing countries: (1) development strategy and job creation, (2) spatial gaps in earnings, (3) rural–rural relocation for work, (4) risk strategies, (5) availability and quality of amenities, (6) education, (7) climate change and natural disasters, (8) forced migration and violence, (9) return and circular migration and (10) family accompaniment and formation. While this list of internal migration drivers in developing countries is largely shareable, we argue that it should also include internationalization and globalization processes, as these may crucially affect the developmental dynamics of fast-growth countries.Footnote8 In this paper we focus on the case of Vietnam as a quickly developing country that, in recent decades, has opened its economy to foreign trade and FDI and, at the same time, been significantly affected by internal migration.

3. INTERNAL MOBILITY AND GLOBALIZATION IN VIETNAM: OUR HYPOTHESES

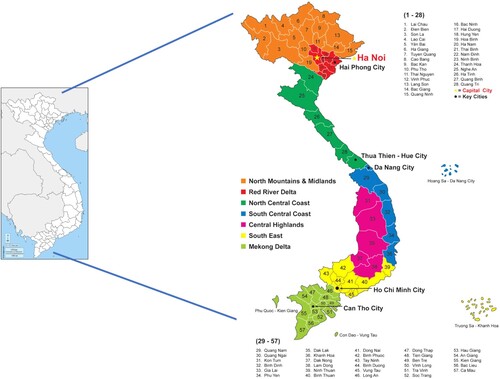

Recent statistics on internal mobility in Vietnam show that a significant proportion of the Vietnamese population (almost 14%) engaged in internal migration over the period 2010–15 (General Statistics Office & United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA), Citation2016). Over the same years, rural–urban and urban–urban migration represented 36.2% and 31.6%, respectively, of total internal mobility. This testifies to the ongoing urbanization in Vietnam and, at the same time, the significant development already achieved in some areas of the country. The bulk of internal migration is intra-regional, but the South East and Central Highlands are important destinations for migrants from other regions – especially the North and South Central Coast and the Mekong River Delta ().

Figure 1. Map of Vietnam’s provinces.

Source: Authors’ elaboration based on https://d-maps.com/carte.php?num_car=986&lang=it and https://amotravel.com/map-of-regions-of-vietnam/.

Migrants are typically young (85% are aged 15–39 years), born in rural areas (79.1%) and better qualified and educated than those who do not migrate (almost 25% of migrants are college/university educated, in comparison with 17% of non-migrants; General Statistics Office & UNFPA, Citation2016). With respect to the main motivation to migrate, the highest percentage of migrants (34.7%) emphasize employment, followed by family or study (25.5% and 23.4%, respectively). However, male migrants mainly move for work reasons, while women tend to migrate for family or study purposes (General Statistics Office & UNFPA, Citation2016).

Since the end of the 1990s, empirical research (especially that focused on macro-gravity models) on the determinants of internal migration in Vietnam has found increased migration in urban areas, despite the fact that government policies – implemented after reunification in 1975 – aimed at promoting rural–rural and urban–rural migration, in order to rebalance geographical disparities in population density (Dang, Citation1998). Reform in the allocation of land-use rights since 1986 (as in the ‘Doi Moi’ policy)Footnote9 is another factor that, contrary to government proposals, has encouraged rural–urban migration through the emergence of labour surpluses in rural areas. Although the higher per capita income of urban areas has been shown to be an important pull factor in inter-provincial migration, liquidity constraints (i.e., the inability to finance migration) in poorer Vietnamese provinces have been sufficiently relevant to surpass the push effect associated with low income (Phan & Coxhead, Citation2010). Macro-gravity models that have introduced unemployment rates (in the origin and destination provinces) as explanatory variables have generated ambiguous results. Nguyen-Hoang and McPeak (Citation2010) found that higher unemployment in the origin province was linked to more out-migration, and higher unemployment in the destination province was associated with more immigration. These puzzling results were likely due to omitted variables or unexplored characteristics of the unemployed and migrants. Nguyen et al. (Citation2008) adopted a micro-approach that complemented the results of macro-gravity models by using the Vietnam Household Living Standard Survey (VHLSS) panel data for households in two years, 2002 and 2004. These authors provided evidence of an inverted ‘U’-shape curve in the likelihood of migration, with respect to per capita expenditures. Looking at VHLSS 2012, Coxhead et al. (Citation2015) found that the probability of migration is more strongly associated with young individuals, with post-secondary education and coming from Vietnamese households whose household head has a better educational attainment.

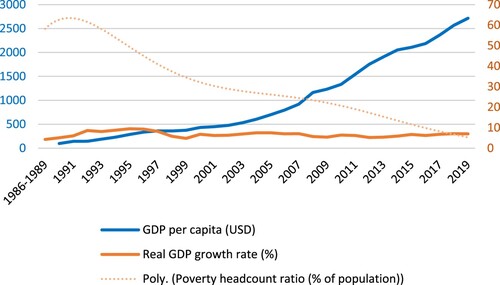

While internal mobility may be linked to rapid economic growth, the latter may be driven by international integration. Indeed, behind Vietnam’s inclusive and socially transformative growth there are 30 years of major policy and institutional reforms that have shifted the economy from central planning toward market mechanisms and global integration.Footnote10 Starting from 1986, the Vietnamese transitional economy has seen an impressive pace of development with a real gross domestic product (GDP) growth rate that ranged from 4.3% to 9.5% and GDP per capita that has grown steadily (). Although this economic performance has contributed to lower poverty rates on average, the high economic growth has not been equally distributed throughout the country: regions such as the Northern Mountains, North Central Coast and Central Highlands have fallen behind,Footnote11 while a large share of industrial capital has concentrated in a very small number of urban centres, mainly Ho Chi Minh City and surrounding provinces (i.e., Ba Ria Vung Tau, Dong Nai, Binh Duong) in the South and Hanoi (the capital), Hai Duong, Hai Phong and Quang Ninh in the North.

Figure 2. Vietnam’s economic indicators, 1986–2019.

Note: The curve representing the poverty headcount ratio was obtained through a polynomial interpolation.

Source: Authors’ elaboration based on World Bank data.

Several studies have investigated economic disparities in Vietnam at various levels: between regions/provinces (Le, Citation2003; Ramachandran & Scott, Citation2009; Taylor, Citation2004), between ethnic minorities and ethnic majorities (Gunewardena & Walle, Citation2000; Scott & Chuyen, Citation2004; World Bank, Citation2006), between/within rural areas (Takahashi, Citation2007), between/within urban areas (Liu, Citation2008), and between rural and urban areas (Liu, Citation2001). In these studies the main explanatory factors of income inequality have been found to be differences in climatic conditions, agricultural capacity, infrastructure, geographical features, natural endowments, human capital, physical capital, household structure and production techniques.

The role of globalization in Vietnamese regional disparities – and, consequently, in internal migration flows – has been relatively unexplored. However, empirical evidence suggests that this factor could be relevant. If we look at one of the most significant dimensions of globalization, FDI, we can observe imbalances in inward foreign investment (General Statistical Office, Citation2021). For instance, between 2001 and 2006, inward FDI was highly concentrated in 19 key economic provinces, representing approximately 92% of total GDP. The two core areas of Hanoi (in the North) and Ho Chi Minh City (in the South) received 27% and 59% of total FDI, respectively, while the remaining 14% was distributed among all other provinces, thereby resulting in the marginalization of remote regions (i.e., Northern Mountains, Central Highlands and North Central Coast).

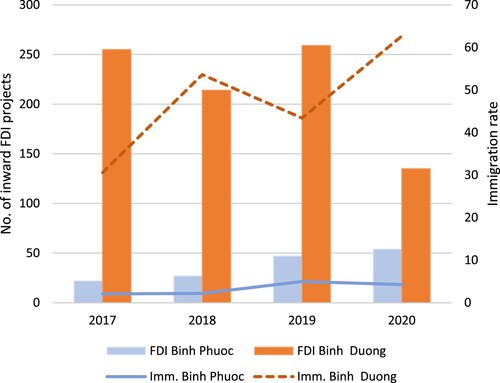

After Vietnam’s accession to the WTO in 2007, the FDI allocation map changed remarkably as the provinces that had previously attracted the most FDI retained a declining share of total GDP (66% in comparison with 92% in the period 2001–06). In 2019, the provinces with the most inward FDI were Binh Duong, Ho Chi Minh City, Hanoi and Binh Duong. These were also the main destinations of internal migration flows, while provinces with the most intensive population pressure on resources and with low average incomes (e.g., those in the North Central Coast region) had the highest rates of out-migration. The interplay between FDI and migration flows is also revealed in a closer look at Binh Duong and Binh Phuoc – two southern provinces that were established after the division of Song Be province 20 years prior. Nationally, Binh Duong has attracted some of the highest proportions of FDI, with annual economic development exceeding 14.5%. In 2019, 259 FDI projects were concentrated in the province, contributing to modernizing industrial production. At the same time, Binh Duong has paid great attention to urban development and invested in human resources, bolstering the local investment environment. Conversely, Binh Phuoc attracted only 47 FDI projects in 2019, mostly due to its inability to capitalize on its favourable geographical conditions. Interestingly, more immigrants have moved to Binh Duong than to Binh Phuoc. In 2019, Binh Phuoc’s immigration rate was only 5.0‰, while that of Binh Duong was 43.4‰.

Many other examples can be offered in support of this significant relationship between FDI and migration flows. In the following section we provide a more systematic analysis of the globalization-internal migration nexus, building an econometric model. We believe that globalization has generated regionally differentiated effects on the Vietnamese economy, entailing flows of native migrants from provinces with relatively less to relatively more FDI, respectively. We use FDI as an index of globalization, since foreign capital has played a crucial role in the country’s privatization and restructuring, providing growth and labour opportunities. The role of FDI as a catalyst for local development is well documented in the literature (Markusen & Venables, Citation1999; Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), Citation2002; United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD), Citation2019). The inflow of capital from abroad for productive investment in developing countries facilitates the access of these countries to new markets and more advanced technological standards, as well as their integration into international rules-based settings. In general, FDI has a positive impact on the performance of local companies by creating a competitive environment that stimulates their export capacity, the transfer of innovations and human capital formation. All this represents a powerful stimulus to economic growth, which is an essential factor in mitigating poverty in developing countries. In addition, in not strictly economic terms, the possible transfer of clean technologies through FDI would also benefit the environment of the host country, and the possible spread of ‘regular’ labour contracts would also lead to an improvement in social conditions. Obviously, against these expected benefits, the downside is a series of adverse effects that could occur in the host country: deterioration of the balance of payments if the bulk of multinational companies’ profits are repatriated; weak linkages with local communities, if not destructive as a result of large-scale production/marketing processes that displace pre-existing local activities; harmful effects on the environment especially in the presence of mining and heavy industries. Moreover, a not secondary effect of FDI is their contribution to regional disparities within host countries as a result of industrial polarization and concentration processes, as well documented, for example, in Central and Eastern European countries, where incoming FDI have been one of the most important drivers of their recent economic growth, but with spatial over-concentration effects (Chapman & Meliciani, Citation2018; Smętkowski, Citation2013). Vietnam itself exemplifies an impetuous economic development driven by FDI and internationalization processes, but with significant spatial polarization effects that inevitably reverberate on internal migration.

displays the trends in immigration rate (calculated for internal migration only) and FDI (measured through the number of inward FDI projects) for the two aforementioned provinces of Binh Duong and Binh Phuoc, showing a clear (positive) correlation between these variables. When we look at the most economically active province (Binh Duong), we can observe a delayed response of migratory flows with respect to FDI, suggesting the relevance of immigration networks. A possible cumulative effect over time seems to occur, which may be interpreted in terms of the pull-through effects stemming from migrant networks, as discussed in section 2.

Figure 3. Immigration and foreign direct investment (FDI) trends in Binh Duong and Binh Phuoc provinces.

In light of this evidence, we propose the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 1: Provinces with higher inward FDI are relatively more attractive to interprovincial migrants than provinces with lower inward FDI.

Hypothesis 2: In a dynamic context, provinces with higher inward FDI and an already established presence of migrants are more attractive destinations of further inter-provincial migration.

4. METHODOLOGY

To test Hypothesis 1, we estimated the following regression model:

(1)

(1) where i and t represent, respectively, the Vietnamese province (i = 1, … , 63) and year (t = 2008, … , 2020). MIGR accounts – alternatively – for a measure of immigration (IMM) and out-migration (OUT) at the inter-provincial level, and FDI for the presence of inward FDI in each province. X is a vector of provincial time-varying control variables that may influence internal migration. It includes proxies for income (INC), university facilities (UNI), skilled work (TRA), poverty (POV), health establishments (HLT) and industrial production (IND). Finally, the error term

∼ IID (0, σ2) accounts for possible stochastic shocks at the provincial level that may affect the dependent variable. Data were gathered from the Vietnamese General Statistics Office. describes all variables.

Table 1. Description of the variables.

Among the control variables we distinguish between those with a narrower economic connotation (TRA, IND), those with a broader socio-economic characterization (INC, POV) and those linked to public goods, such as education and health (UNI, HLT).

With regard to TRA and IND, we assume that provinces with a higher incidence of skilled workers and a greater industrial production index are more economically dynamic and, therefore, more attractive to incoming migration. INC and POV are proxies for living conditions and economic well-being. In particular, INC tests whether provinces with relatively high returns for labour attract more immigrants than those with relatively poor returns for labour. Regarding POV, we know that emigration, when sustainable, can provide an escape from conditions of poverty and deprivation; thus, this variable expresses a push factor for migration. Therefore, first, we assume that provinces with a higher poverty rate experience a greater outflow of migrants and, subordinately, are less attractive for incoming migrants. Finally, UNI and HLT represent locational amenities (Greenwood, Citation1985) and non-traded goods that may encourage mobility. In particular, we use the number of health establishments (HLT) as an indicator of health development, and assume that higher opportunities for health services attract immigrants. With regard to education (i.e., UNI), we know that the decision to move not only considers potential economic benefits, but also takes into account potential educational opportunities for migrants and/or their offspring. We use UNI as a proxy for ease of access to tertiary education, and assume that the greater the number of university teachers in a province, the more attractive the province is for immigrants.

Model 1 was first estimated through traditional pooled, fixed and random panel estimators and then through a quantile estimator, for robustness. Quantile regression represents an extension of ordinary least squares (OLS). Whereas the standard OLS estimator considers the average relationship between a regressor (x) and a dependent variable (y) based on the conditional mean function (E[y/x]), and therefore focuses on a single part of the conditional distribution, the quantile regression model employs a continuum of quantile functions, describing the above relationship at different points in the conditional distribution of y (Troster et al., Citation2018). Since tail causality may differ from mean causality, this method generates more robust estimations than OLS against outliers in the response measurements, by providing information about the possibly heterogeneous effects of a regressor at different quantiles of the dependent variable. Moreover, it can be particularly useful for managing heteroskedasticity (Huang et al., Citation2017).

To test Hypothesis 2, we estimated a dynamic panel data model that allowed us to identify possible pull-through effects in both in- and out-migration flows (i.e., whether migration in year t is affected by migration in year t – 1). Accordingly, we estimated the following model:

(2)

(2) where the vector X includes the same provincial time-varying control variables employed in regression (1), whereas

represents the error term. Due to its dynamic nature, model 2 can be estimated following several approaches. Using pooled OLS, intercepts and slope coefficients are treated as homogeneous across all i cross-sections and through all t time periods. However, slope estimates can be biased if the provincial-specific effects are correlated with the regressors, as occurs in this model. Therefore, a dynamic fixed-effects approach is more appropriate (Hauk & Wacziarg, Citation2009). Nevertheless, due to the presence of the lagged dependent variable among the regressors, the traditional within estimator cannot be used, since the within transformation would lead to a correlation between the lagged dependent variable and the error term and, therefore, to biased and inconsistent estimates. A possible solution to this problem consists in using the Arellano and Bond (Citation1991; Citation1998) estimator which uses moment conditions in which lags of the dependent variable and first differences of the exogenous variables are instruments for the first-differenced equation. The Arellano–Bover/Blundell–Bond GMM estimator (Arellano & Bover, Citation1995; Blundell & Bond, Citation1998; Hansen, Citation1982) augments Arellano–Bond by assuming that first differences of instrument variables are uncorrelated with the fixed effects. This allows for the introduction of more instruments, thereby considerably improving efficiency. Aside from the presence of a dynamic dependent variable (i.e., depending on its own past realisations), this estimator is appropriate for cases of heteroskedasticity and autocorrelation within – but not across – individuals (Roodman, Citation2009). Thus, the Arellano–Bond and Arellano–Bover/Blundell–Bond GMM estimators were used to estimate model 2.

reports the descriptive statistics.

Table 2. Descriptive statistics.

5. RESULTS

Estimations were conducted using STATA16 econometric software. reports the results of model 1. According to the findings jointly achieved from the Breusch–Pagan and Hausman tests, the fixed effect resulted in the most appropriate estimator, whose results are reported along with the pooled and the quantile estimations.

Table 3. Model 1 estimation’s results.

The Wald test shows the presence of heteroskedasticity, suggesting the pertinence of carrying out the quantile estimation along with the fixed effect. Moreover, the use of this estimation method is also appropriate due to the presence of outliers in the dataset. In particular, we refer to the provinces of Ho Chi Minh City and Ha Noi, which cannot be dropped from the dataset since they represent the most important metropolitan areas with the highest concentration of FDI, as discussed in section 3.

With regard to the determinants of immigration (columns 1–3), the FDI coefficient is significant in all specifications, confirming the hypothesis that internationalization plays an important role in determining internal mobility. The positive sign of FDI indicates that provinces with larger presence of multinational enterprises (MNEs) attract more immigrants. With respect to the control variables, the coefficient of INC is positive and highly significant in the fixed effects and quantile regressions, confirming the hypothesis that provinces with higher incomes are most attractive. Similarly, the coefficient of UNI is positive and highly significant in all specifications, suggesting that greater opportunities for university education foster immigration. On the other hand, the coefficients of TRA and IND are also positive and highly significant, although only in the quantile specification. Among the remaining control variables, the only steadily significant one is POV, whose positive sign can be explained by the possible polarization in income distribution, whereby a high poverty index may be accompanied by medium-high average income.

With respect to out-migration (columns 4–6), the FDI coefficient becomes broadly insignificant, suggesting that the activity of MNEs does not influence outflows of migration, but only inflows (as described above). In other words, the results suggest that MNEs do not directly affect the decision to migrate, but rather – in a two-stage process – influence the choice of migration destination once the decision to migrate has been made. As for the control variables, the coefficients of TRA, HLT and IND are negative although with different levels of significance across the various specifications, suggesting that migrants mainly leave less dynamic provinces (i.e., those with a low proportion of trained employed workers, limited health services and a lower industrial production index). The POV variable displays a positive and significant coefficient, indicating that provinces with higher poverty rates induce out-migration. As for immigration, UNI is positively related to out-migration, suggesting that, in general, both incoming and outgoing mobility are positively linked to provinces with the most university endowments. These provinces operate therefore as both attractors and developers of human capital formation, with the latter representing a factor that encourages mobility. Finally, the INC coefficient is positive and significant only in the fixed effects specification, but negative in the pooled and quantile regressions. How can this unexpected result be justified? One possible explanation is that there is an income threshold beyond which people do not emigrate. People with very low income are expected to emigrate to gain more money, but people with higher income are not expected to have the necessity to emigrate. Before reaching the income turning point, emigration can be expected to rise as income increases, since the cost of mobility becomes more affordable. To this end, we added the income variable squared among the regressors (columns 7–9). The existence of an income turning point is confirmed by the signs of the INC and INC2 coefficients, which are positive and negative, respectively, and both significant. The signs and significance levels of the other control variables remain confirmed.

In light of these findings, Hypothesis 1 seems validated.

reports the results of the model 2 estimation.

Table 4. Model 2 estimation’s results.

The results of the Sargan and Arellano–Bond tests suggest good specification for the model and that the instruments used are valid. As shown in , the lagged variable is positive and significant in all specifications, suggesting that migration in year t is affected by migration in year t – 1 (i.e., a pull-through effect), and thereby supporting Hypothesis 2.

The dynamic estimation generally corroborates the prior results. In particular, the attractiveness of provinces with the greatest MNE activity is confirmed with regard to incoming migration flows only, and the non-linear trend of INC and the positive role of UNI are confirmed for both incoming and outgoing mobility. The hypothesis of polarization in the income distribution is also verified with regard to the POV variable and its effect on incoming migration flows, and its expected sign is confirmed in relation to the outgoing flows.

6. CONCLUSIONS

The present study has investigated the impact of internationalization processes on Vietnam’s interprovincial migration flows. Since the 1990s, Vietnam has experienced intense growth, accompanied by equally significant international integration, favoured by its entry into the WTO in 2007. These processes have accompanied internal dynamics of strong urbanization and robust population movement. Despite policies to encourage territorial rebalancing of the population carried out in the past by the government, the most intense internal migration processes have involved rural–urban flows, following economic agglomeration in the most developed urban centres.

In this context, FDI represents an important driver of the concentration of economic activities in the most productive Vietnamese provinces. For this reason, this study has focused on FDI as a proxy for the country’s internationalization, while investigating its role in internal migration. In our view, exploring the role of FDI in interprovincial movement represents a novel contribution to the literature on besides the traditional determinants of internal mobility.

Overall, our findings support the hypothesis that provinces with more inward FDI projects attract more inter-provincial migrants. In our estimates, most of the control variables have statistically significant coefficients, with the expected sign. In particular, provinces with more trained employed workers and a higher industrial production index are most attractive, confirming the importance of economic incentives to migrate. Similarly, provinces with greater health services are more attractive, suggesting the relevance of these services for potential migrants. Education also plays a significant role in internal mobility, with university endowments operating as both attractors and developers of human capital formation, thereby encouraging internal migration. Finally, provinces with higher average income levels are most attractive for immigrants. At the same time, the results show the existence of an inverted ‘U’-shaped relationship for emigration, showing that, as provincial income rises, migratory outflows first increase, then decrease. The rationale for this pattern is that low-income individuals must first increase their economic resources to be able to afford migration costs; however, once they have reached an income threshold, their incentive to emigrate declines as their income rises further. Moreover, from a dynamic perspective, the results corroborate the existence of a pull-through effect, confirming the importance of migrant networks, as largely highlighted in the literature.

Overall, the results suggest some policy implications. First, we have observed that migration flows mainly lead to a limited number of provinces. On the one hand, this may generate polarization effects in urban areas that are already congested in terms of population density and production; on the other hand, it may lead to further impoverishment of areas with greater agricultural vocation, resulting in negative socio-economic effects. Therefore, policies aimed at developing the local economy of relatively impoverished provinces would be desirable: such territorial rebalancing could serve to contain the dispersion of human capital, which represents a determining factor for long-term growth.

Future lines of research should aim at overcoming the limitations of this study. First, the availability of an origin–destination matrix for migration flows would enable explanatory variables to be expressed in relative terms (differentials). In addition, other hypotheses – relevant in the literature – related to migration decisions at both individual and family levels should be tested, in light of data on individual migrant characteristics (e.g., gender, age, skill levels). Future research could also include the productive specialization of the provinces that are attractors of internal migrants and take into account the existing regional disparities.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Published with a contribution from 5 x 1000 IRPEF funds in favour of the University of Foggia, in memory of Gianluca Montel.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Notes

1 In Malaysia, 51% of the population is under 30 years of age and inter- and intra-state migrants represent, respectively, 34.8% and 65.2% of the population (Department of Statistics Malaysia, Citation2021).

2 Quantile regression enables us to manage outliers, that is, the areas of Ho Chi Minh City and Ha Noi, which attract the most FDI and cannot be dropped from the dataset.

3 Although a difference between international and internal migration is recognized – if only in consideration of the regulatory role of the state – King and Skeldon (Citation2010, p. 1521) argued that ‘the “boundary” between internal and international migration can easy become blurred’ due to the similarity of explanatory factors between internal and international mobility. Similarly, Bodvarsson and Van den Berg (Citation2013, p. 27) claimed that ‘While there is a strong tendency in the literature to distinguish between domestic (internal) and international (external) migration, there is actually just one economic theory of migration’.

4 In the case of the Czech Republic, see Fidrmuc and Huber (Citation2007) and Jandovà and Paleta (2015). In the case of Italy, see Lamonica and Zagaglia (Citation2013). Smith et al. (Citation2016) provided a useful survey of internal migration in the UK over the past 20 years.

5 The shadow side of Chinese internal mobility is the phenomenon of ‘brain drain’: although coastal cities have enjoyed an inflow of skilled labour over recent years, the rest of the country has recorded dramatic losses in human capital (Liu & Shen, Citation2014).

6 For an analysis of economic development in the Outer Islands of Indonesia during the colonial period (1900–42), see also Touwen (Citation2001).

7 Junge et al. (Citation2015) observed that in Thailand and Vietnam migrants began to return to their home regions for employment as non-farm income opportunities spread to the periphery.

8 Internationalization and globalization are here used as synonyms but in reality their sequence (internationalization first and globalization later) indicates the very dynamics that mark the transition from a progressively increasing degree of openness towards international trade to the phase of globalization of markets, the pervasiveness of global value chains and the presence of multinational corporations’ activities in host countries through massive incoming FDI. In a sense, globalization is the culminating phase of internationalization processes in which the regulatory power of governments is perceived to be lost. Indeed, as sometimes emerges in the literature (OECD, Citation2002), the downside of FDI is also the host country authorities’ perception that they are too dependent on foreign companies to the extent that they feel a loss of political sovereignty.

9 December 1986 was a turning point in Vietnamese economic history when the Communist Party of Vietnam launched the so-called Doi Moi Renovation Process – a comprehensive reform package aimed at achieving the socialist-oriented market economy. Seven measures were set out: (1) almost, complete price liberalization; (2) significant devaluation and unification of the exchange rate; (3) an increase in interest rates to positive levels in real terms; (4) a substantial reduction in subsidies to state-owned enterprises (SOE); (5) agricultural reforms through replacement of cooperatives by households as the core decision-making unit in production and security of tenure for farming families; (6) encouragement of the private sector, including FDI; and (7) removal of domestic trade barriers and the creation of a more open economy (Thanh & Ha, Citation2004).

10 Vietnam participated in the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) in 1995 and, in the same year, signed a framework agreement with the European Union for technical, commercial and economic cooperation. Subsequently, it took part in the Asia–Pacific Economic Cooperation Forum (APEC) in 1998, joined the WTO in 2007 and, most recently, entered the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP). These actions dismantled a significant number of trade obstacles.

11 Vietnam comprises eight regions, including the North West, North East, Red River Delta, North Central Coast, South Central Coast, Central Highlands, South East and Mekong River Delta (GSO, 2009). The wealthiest region is the South East, where the largest economic centre (Ho Chi Minh City) is located, followed by the Red River Delta, which hosts Hanoi (the capital). On the other hand, the Northern Uplands, North Central Coast and Central Highlands have only marginal wealth.

REFERENCES

- Arellano, M., & Bond, S. (1991). Some tests of specification for panel data: Monte Carlo evidence and an application to employment equations. The Review of Economic Studies, 58(2), 277–297. https://doi.org/10.2307/2297968

- Arellano, M., & Bond, S. (1998). Dynamic panel data estimation using DPD98 for Gauss: A guide for users. Mimeo.

- Arellano, M., & Bover, O. (1995). Another look at the instrumental variable estimation of error-components models. Journal of Econometrics, 68(1), 29–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/0304-4076(94)01642-D

- Beine, M., & Salomone, S. (2013). Network effects in international migration: Education versus gender. The Scandinavian Journal of Economics, 115(2), 354–380. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9442.2012.01733.x

- BKPM. (2019). Domestic and foreign direct investment realization. Quarter IV and January–December 2019. https://www.bkpm.go.id/images/uploads/file_siaran_pers/Paparan_Bahasa_Inggris_Press_Release_TW_IV_2019.pdf.

- Blundell, R., & Bond, S. (1998). Initial conditions and moment restrictions in dynamic panel data models. Journal of Econometrics, 87(1), 115–143. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0304-4076(98)00009-8

- Bodvarsson, Ö. B., & Van den Berg, H. (2013). The economics of immigration. Springer.

- Borjas, G. J. (1990). Self-selection and the earnings of immigrants: reply. The American Economic Review, 80(1), 305–308.

- Borjas, G. J. (2019). Labor economics (Eighth Edition). McGraw Hill.

- Borjas, G. J., Bronars, S. G., & Trejo, S. J. (1992). Self-selection and internal migration in the United States. Journal of Urban Economics, 32(2), 159–185. https://doi.org/10.1016/0094-1190(92)90003-4

- Boyd, M. (1989). Family and personal networks in international migration: Recent developments and New Agendas. International Migration Review, 23(3), 638–670. https://doi.org/10.1177/019791838902300313

- Chan, K. W. (2013). China: Internal migration. In I. Ness, & P. Bellwood (Eds.), The encyclopedia of global human migration (pp. 1–15). Blackwell Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781444351071.wbeghm124.

- Chapman, S., & Meliciani, V. (2018). Explaining regional disparities in Central and Eastern Europe: The role of geography and of structural change. Economics of Transition, 26(3), 469–494. https://doi.org/10.1111/ecot.12154

- Chen, Y., & Rosenthal, S. S. (2008). Local amenities and life-cycle migration: Do people move for jobs or fun? Journal of Urban Economics, 64(3), 519–537. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jue.2008.05.005

- Coxhead, I., Nguyen, C. V., & Vu, L. H. (2015). Migration in Vietnam: New evidence from recent surveys. Vietnam Development Economics Discussion Papers. 2.

- Dang, N. A. (1998). Patterns of migration and economic development in Vietnam. Vietnam Economic Review, 7, 38–45.

- Dennett, A., & Stillwell, J. (2008). Population turnover and churn: Enhancing understanding of internal migration in Britain through measures of stability. Population Trends, 134, 24.

- Department of Statistics Malaysia. (2021). Migration survey report, Malaysia, 2020. Available at: https://www.dosm.gov.my/v1/index.php?r=column/cthemeByCat&cat=125&bul_id=dDQ2U05BZjM5ZCtaa3JOQW5Jbm5VQT09&menu_id=U3VPMldoYUxzVzFaYmNkWXZteGduZz09#:~:text=Intra%2DState%20Migration,to%20be%2076.7%20per%20cent.

- Fidrmuc, J. (2004). Migration and regional adjustment to asymmetric shocks in transition economies. Journal of Comparative Economics, 32(2), 230–247. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jce.2004.02.011

- Fidrmuc, J., & Huber, P. (2007). The willingness to migrate in the CEECs evidence from the Czech Republic. Empirica, 34(4), 351–369. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10663-006-9028-6

- General Statistical Office. (2021). Data on population and investment and construction, General Statistics Office of Vietnam, https://www.gso.gov.vn/en/.

- General Statistics Office & United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA). (2016). The 2015 national internal migration survey, Ha Noi: Vietnam news. Agency Publishing House. https://vietnam.unfpa.org/sites/default/files/pub-pdf/PD_Migration%20Booklet_ENG_printed%20in%202016.pdf.

- Greenwood, M. J. (1975). Research on internal migration in the United States: A survey. Journal of Economic Literature, 13(2), 397–433.

- Greenwood, M. J. (1985). Human migration: Theory, models, and empirical studies. Journal of Regional Science, 25(4), 521–544. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9787.1985.tb00321.x

- Greenwood, M. J. (1997). Internal migration in developed countries. Handbook of Population and Family Economics, 1, 647–720. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1574-003X(97)80004-9

- Gunewardena, D., & Van de Walle, D. (2000). Sources of ethnic inequality in Vietnam. Policy Research Working Paper Series 2297, The World Bank.

- Hansen, L. P. (1982). Large sample properties of generalized method of moments estimators. Econometrica, 50(4), 1029–1054. https://doi.org/10.2307/1912775

- Hauk, W. R., & Wacziarg, R. (2009). A Monte Carlo study of growth regressions. Journal of Economic Growth, 14(2), 103–147. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10887-009-9040-3

- Huang, Q., Zhang, H., Chen, J., & He, M. (2017). Quantile regression models and their applications: A review. Journal of Biometrics & Biostatistics, 8, 3. https://doi.org/10.4172/2155-6180.1000354

- Jandová, M., & Paleta, T. (2015). Gravity models of internal migration – The Czech case study. Review of Economic Perspectives, 15(1), 3–14. https://doi.org/10.1515/revecp-2015-0008

- Junge, V., Diez, J. R., & Schätzl, L. (2015). Determinants and consequences of internal return migration in Thailand and Vietnam. World Development, 71, 94–106. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2013.11.007

- King, R., & Skeldon, R. (2010). ‘Mind the gap! Integrating approaches to internal and international migration. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 36(10), 1619–1646. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2010.489380

- Lamonica, G. R., & Zagaglia, B. (2013). The determinants of internal mobility in Italy, 1995–2006: A comparison of Italians and resident foreigners. Demographic Research, 29, 407–440. https://doi.org/10.4054/DemRes.2013.29.16

- Le, K. Q. (2003). An assessment of spatial differentiation in Vietnam's social-economic development, 1990–2000. PhD dissertation. The University of Akron.

- Liu, A. Y. (2001). Markets, inequality and poverty in Vietnam. Asian Economic Journal, 15(2), 217–235. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8381.00132

- Liu, A. Y. (2008). Changes in urban inequality in Vietnam: 1992–1998. Economic Systems, 32(4), 410–425. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecosys.2007.10.002

- Liu, Y., & Shen, J. (2014). Jobs or amenities? Location choices of interprovincial skilled migrants in China, 2000–2005. Population, Space and Place, 20(7), 592–605. https://doi.org/10.1002/psp.1803

- Lucas, R. E. (2015). Internal migration in developing economies: An overview. KNOMAD’s Working Paper, 6.

- Markusen, J. R., & Venables, A. J. (1999). Foreign direct investment as a catalyst for industrial development. European Economic Review, 43(2), 335–356. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0014-2921(98)00048-8

- Massey, D. S., Arango, J., Hugo, G., Kouaouci, A., Pellegrino, A., & Taylor, J. E. (1993). Theories of international migration: A review and appraisal. Population and Development Review, 19(3), 431–466. https://doi.org/10.2307/2938462

- Munshi, K., & Rosenzweig, M. (2013). Networks, commitment, and competence: Caste in Indian local politics (No. w19197). National Bureau of Economic Research.

- Nguyen, T. P., Tran, N. T. M. T., Nguyen, T. N., & Oostendorp, R. (2008). Determinants and impacts of migration in Vietnam, Depocen working paper series No. 2008/01, Hanoi, Vietnam: Development and Policies Research Center.

- Nguyen-Hoang, P., & McPeak, J. (2010). Leaving or staying: Inter-provincial migration in Vietnam. Asian and Pacific Migration Journal, 19(4), 473–500. https://doi.org/10.1177/011719681001900402

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). (2002). Foreign direct investment for development. Maximising benefits, minimising costs. OECD Publications Service.

- Oswald, A. J. (1996). A conjecture on the explanation for high unemployment in the industrialized nations: Part I. The Warwick economics research paper series (TWERPS) 475, University of Warwick, Department of Economics.

- Oswald, F. (2019). The effect of homeownership on the option value of regional migration. Quantitative Economics, 10(4), 1453–1493. https://doi.org/10.3982/QE872

- Phan, D., & Coxhead, I. (2010). Inter-provincial migration and inequality during Vietnam's transition. Journal of Development Economics, 91(1), 100–112. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdeveco.2009.06.008

- Ramachandran, L., & Scott, S. (2009). Single-player universities in the south: The role of university actors in development in Vietnam's north central coast region. Regional Studies, 43(5), 693–706. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343400701874115

- Roodman, D. (2009). How to do Xtabond2: An introduction to difference and system GMM in Stata. The Stata Journal: Promoting Communications on Statistics and Stata, 9(1), 86–136. https://doi.org/10.1177/1536867X0900900106

- Scott, S., & Chuyen, T. T. K. (2004). Behind the numbers: Social mobility, regional disparities, and new trajectories of development in rural Vietnam. In P. Taylor (Ed.), Social inequality in Vietnam and the challenges to reform, ISEA Publishing (pp. 123–165).

- Sjaastad, L. A. (1962). The costs and returns of human migration. Journal of Political Economy, 70(5), 80–93. https://doi.org/10.1086/258726

- Smętkowski, M. (2013). Regional disparities in Central and Eastern European Countries: Trends, drivers and prospects. Europe–Asia Studies, 65(8), 1529–1554. https://doi.org/10.1080/09668136.2013.833038

- Smith, D. P., Finney, N., & Walford, N. (2016). Internal migration: Geographical perspectives and processes. Routledge.

- Stark, O. (1991). Migration in LDCs: Risk, remittances, and the family. Vol. 28, No. 004, p. A013. International Monetary Fund.

- Stark, O., & Taylor, J. E. (1989). Relative deprivation and international migration oded stark. Demography, 26(1), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.2307/2061490

- Takahashi, K. (2007). Sources of regional income disparity in rural Vietnam: Oaxaca–Blinder decomposition. IDE Discussion Paper 95, Institute of Developing Economies, Japan External Trade Organization (JETRO).

- Taylor, P. ed. (2004). Social inequality in Vietnam and the challenges to reform Vol. 23. Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, p. 212.

- Thanh, V. T., & Ha, P. H. (2004). Vietnam’s recent economic reforms and developments: Achievements, paradoxes, and challenges. In P. Taylor (Ed.), Social inequality in Vietnam and the challenges to reform, ISEA Publishing (pp. 63–89).

- The Economist. (2012). Welcome home: Changing migration patterns. The Economist, 25 February. https://www.economist.com/china/2012/02/25/welcome-home.

- Todaro, M. P. (1976). Rural–urban migration, unemployment and job probabilities: Recent theoretical and empirical research. In A. J. Coale (Ed.), Economic Factors in Population Growth (pp. 367–393). Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-349-02518-3_13.

- Touwen, J. (2001). Extremes in the archipelago: Trade and economic development in the outer islands of Indonesia, 1900–1942. KITLV Press.

- Treyz, G. I., Rickman, D. S., Hunt, G. L., & Greenwood, M. J. (1993). The dynamics of US internal migration. The review of Economics and Statistics, 209–214.

- Troster, V., Shahbaz, M., & Uddin, G. S. (2018). Renewable energy, oil prices, and economic activity: A Granger-causality in quantiles analysis. Energy Economics, 70, 440–452.

- United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD). (2019). World investment report. Special economic zones. United Nations.

- United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO). (2018). Overview of internal migration in Cambodia. Policy Briefs on Internal Migration in Southeast Asia, jointly produced by UNESCO, UNDP, IOM, and UN-Habitat. http://bangkok.unesco.org/content/policy-briefs-internal-migration-southeast-asia.

- Van Lottum, J., & Marks, D. (2012). The determinants of internal migration in a developing country: Quantitative evidence for Indonesia, 1930–2000. Applied Economics, 44(34), 4485–4494. https://doi.org/10.1080/00036846.2011.591735

- World Bank. (2006). Vietnam aiming high. Vietnam development report 2007. joining donor report to the Vietnam consultative group meeting, Hanoi, December 14–15, 2006.

- World Bank. (2009). World development report. Reshaping economic geography. The World Bank.