ABSTRACT

This article provides new insights into the relationship between industrialization and new forms of post-industrial development. Adopting a historical sensibility, it frames the contemporary development of the local economy of the city of Siracusa, in south-east Sicily, in an evolutionary historical perspective. The article focuses on the recent process of touristification of the city and surrounding area, analysing this process in connection with the industrialization and growth-pole strategy implemented in south-east Sicily in the post-war period. Emphasis is placed on the narratives that have been mobilized to justify different forms of development in the area, focusing in particular on the recurrent representation of the area as a periphery. Pointing out the selective use of visions of the past in post-industrial development strategies, the authors highlight how an uncomfortable industrial past has been removed from the main narratives to envision the city of Siracusa as moving towards a new phase of capitalist development. Finally, the article provides novel insights into the critical literature on tourism, showing that tourism, narrated and promoted as a sustainable and eco-compatible alternative to industrialization in Siracusa, can in fact produce highly negative impacts on the local environment and communities.

JEL:

1. INTRODUCTION

In the mid-1950s the Italian government launched an ambitious top-down industrialization programme for the country’s depressed and underdeveloped southern regions to reduce the socio-economic gap between these areas and the wealthier northern regions. Inserted in the wider framework of the Marshall post-war reconstruction plan and explicitly inspired by Perroux’s (Citation1955) growth poles theory, the Industrial Development Areas strategy involved the industrialization of selected southern Italian coastal areas, one of which was the province of Siracusa in south-eastern Sicily. This pole was assigned the role of spreading development and well-being in a peasant-like premodern society as well as leading it towards industrialized modernity. The pole of Siracusa produced a significant impact in terms of socio-economic transformation. It became one of the largest petrochemical poles in Europe and, until the 1970s, processed approximately 60% of all crude oil at the national level (Benadusi, Citation2018). Heavily hit by the mid-1970s’ international oil crisis and related collapse of the Italian chemical sector, the Siracusa industrial corridor began to undergo an inexorable decline. Progressive falls in employment rates and the emergence of a new awareness about environmental and public health impacts fostered stagnation and public distrust. In recent decades, a ‘post-industrial turn’ rhetoric has been reshaping institutional discourses and patterns of development in the city of Siracusa, using a set of narratives and strategies ranging from tourism-led regeneration to green and smart growth.

The article follows recent developments in regional studies and economic geography that stress the importance of developing a historical sensibility by considering time and history when explaining the evolution of regional economies in order to capture their multiple and evolving spatial configurations (Castigliano, Citation2018; Garretsen & Martin, Citation2010; Henning, Citation2019; Kolasa-Nowak, Citation2019; Zarycki, Citation2007). This strand of literature – developed to counter the tendency to take ‘snapshots’ and thus underestimate the importance of historical representations (Hincks et al., Citation2017, p. 654) – calls for adopting a longitudinal long-term perspective when analysing different forms and conceptualizations of regional development over time. This is not necessarily a new approach: as early as 1939, August Lösch, one of the founding fathers of economic geography, posited the necessity of considering both time and space in economic analysis: ‘If everything occurred at the same time, there would be no development. If everything existed in the same place, there would be no particularity. Only space makes possible the particular, which then unfolds in time’ (quoted in Garretsen & Martin, Citation2010, p. 130).

The article therefore frames the contemporary development in the local economy of the city of Siracusa in an evolutionary historical perspective. In adopting this position, it focuses on the recent process of touristification of Siracusa by placing it in connection with an analysis of the industrialization and growth-pole strategy implemented in south-eastern Sicily in the post-war period. The paper also aims to map a timeline of the narratives that have been deployed to justify different forms of development in the area, focusing in particular on the recurrent representation of the area as a periphery. In doing so, it seeks to offer further evidence of how a diachronic analysis of economic development and its failures can provide crucial insights for a critical assessment of current urban and regional policy, and to support the development of new policy (Castigliano, Citation2018).

In considering history, much of the literature in the field of regional studies and geography documents the crucial role the past can play in constructing and shaping new identities, images, brands and spatial configurations of contemporary cities and regions (Castigliano, Citation2018; Hincks et al., Citation2017; Hincks & Powell, Citation2022; Hoole & Hincks, Citation2020; Paasi, Citation2013; Vall, Citation2011). In many cases, scholars have interpreted the elements of the industrial landscape in particular as heritage worth valorizing and capable of contributing to local development (Bianchi & Placidi, Citation2021; Dansero et al., Citation2003; Lazzeroni & Grava, Citation2021) by taking into consideration both their material components (e.g., industrial buildings, warehouses and machinery) and their intangible components (e.g., cultural traditions, knowledge and production methods) (Raffestin, Citation2006). Pointing out the selectiveness characterizing uses of the past, however, this article paints a different picture. In the case of Siracusa, an uncomfortable industrial past was removed so as to represent the city as moving towards a new phase of capitalist development and rebrand it as an international tourist destination. The creation of this new cultural and touristic city unfolded through a process we define as ‘industrial undoing’. We borrow from the psychanalytic domain the concept of ‘undoing’ first formulated by Freud (Citation1909), indicating a defence mechanism through which individuals try to remove a threatening memory of an event or thought as if it had never happened. We thus argue that Siracusa’s industrial past has been similarly purged from the main narratives promoting tourism-led development through a collective ‘defence mechanism’ aimed at symbolically undoing not only the consequences of industrialization but the process itself, as if it had never occurred there.

Finally, the article provides novel insights into the critical literature on tourism (Boukhris, Citation2017; Büscher & Fletcher, Citation2017; Devine, Citation2017; Devine & Ojeda, Citation2017; Gibson, Citation2021; Salazar, Citation2017), underlining that tourism – narrated and promoted as a sustainable and eco-compatible alternative to more exploitative forms of development – can in fact produce strong negative impacts on the local environment and communities.

The paper is organized as follows. The second section outlines the context of Italy’s regional imbalances, state interventions to promote industrialization in depressed regions, and the more recent tourism – and culture-led wave of development. The third section outlines the methodological approach and case study area. The fourth section presents the findings of our analysis by describing the evolution of economic development in the Siracusa area from post-war industrialization through the 1970s’ crisis to the present. The fifth section details how the current crisis, striking both the environment and traditional top-down industrialization strategies, has contributed to shaping a new tourism rhetoric for the city of Siracusa and set the stage for new real-estate development in the field of tourism. A discussion and final considerations are presented in the last section.

2. FROM GROWTH POLES TO TOURISM-LED DEVELOPMENT

The Italian socio-economic system is characterized by intense subnational polarization between the country’s dynamic and vibrant northern regions and underdeveloped southern ones. This historically rooted gap has been further exacerbated in recent decades by the new socio-economic inequalities reshaping long-entrenched core–periphery relations on a global scale (Kühn, Citation2015). The worldwide rise in socio-spatial disparities is mirrored by the growing use of terms such as peripheralization and marginalization in academic research, embedded in a process-centred perspective that has recently been combined with the traditional distance-based vision of periphery (Crone, Citation2012; Fischer-Tahir & Naumann, Citation2013; Herrschel, Citation2011; Lang, Citation2012).

Regional disparities are often viewed through a prevailing dual approach that identifies the opposing poles of centralization and peripheralization as the main causes of uneven development, fostered by the increasing growth of structural disadvantages in peripheries. According to this view, a dominant core will tend to absorb socio-economic assets and high-level functions, thereby peripheralizing other local areas (Pociūtė-Sereikienė, Citation2019).

As a result, peripheries are constantly reproduced by a diverse repertoire of socio-spatial inequalities that are embedded in both long-lasting, historically rooted polarization processes and unprecedented divergent dynamics fostered by ongoing globalization. As Iammarino et al. (Citation2019) argue, since the late 1970s’ globalizing processes, tech-driven transformations and policy agendas have generated what critical observers have called the ‘great inversion’ inserted in a new global geography of jobs (Moretti, Citation2012; Storper, Citation2013). This inversion has been driven by the increasing decline of once-prosperous rural or middle-to-small metropolitan regions owing to decreasing employment rates and per capita income. In contrast, several large metropolitan regions have enjoyed rising employment and income rates. In the complex and multifaceted European scenario, on the one hand stagnating, industrialized remote regions have been increasingly split off from the most dynamic urban agglomerations, thereby reinforcing a steady, long-term dichotomy. On the other hand, several capital metropolitan regions have been struck by a harsh socio-economic crisis whilst some rural or middle-to-small regions have demonstrated higher levels of resilience (Dijkstra et al., Citation2015).

Within this ever-changing core–periphery dichotomy, Italian policymakers have been engaged in a heated debate about development trajectories for decades, giving rise to an overall national strategy designed to reduce intra-national divides since the post-war era (Pescatore, Citation2008).

The state-led strategy of industrialization through ‘extraordinary intervention’ in southern Italy was influenced by the economic theories on economic growth developed in the post-war era, notably the 1950s’ polarization theories posed as an alternative to the critical neoclassical perspective by emphasizing that centres tend to enjoy cumulative processes of growth while peripheries weaken on a regional scale. This vision of polarized development was understood as the outcome of self-reinforcing dynamics that continually widen the gap between the most advanced core regions and marginalized peripheries (Maes, Citation2007).

The political debate was influenced by Perroux’s (Citation1955) model of agglomeration involving the combination of intra-firm and interfirm relationships driven by – in Perroux’s words – a ‘propulsive’ firm. In Perroux’s view, growth was seen as naturally stemming from the consequences of an unbalanced, uneven process and as an inherent feature of a dynamic economic space embedded in an input–output system in which one propulsive industry acts as a development engine by stimulating – and dominating – other industries.

By the mid-1960s, the growth-pole perspective had gained worldwide popularity, becoming a ubiquitous ‘cross-national’ framework for increasingly homogenizing Fordist–Keynesian regional policies. This theoretical–operational framework was applied in a variety of socio-cultural contexts, with Latin America among the early adopters. In many cases, however, it failed to achieve its main policy goals within the envisioned timeframe. Historically formulated to apply more to underdeveloped economies than a ‘dual’ economic system like the Italian one, this theoretical–methodological approach fostered new patterns of imbalances and socio-economic divides (Parr, Citation1999a, Citation1999b).

In the last two decades, the centre–periphery dichotomy has been vigorously called into question (McCann & van Oort, Citation2019). As Kühn (Citation2015, p. 371) underlines:

a general weakness of polarization theories is that the principle of circular causation is often too rigid and clear-cut. The underlying assumption, that in peripheries everything is in decline due to a loss of migration and investments, neglects the possibility of a ‘de-peripheralization’ or ‘re-centralization’.

Over the last three decades, therefore, a growing emphasis has been placed on culture, creativity, and tourism-led renewal programmes as ‘alternative’ approaches for supporting post-industrial development. Hailed as inclusive and sustainability-oriented strategies, such programmes mirror the increasingly ubiquitous culturalization of economic development led by cognitive–culture capitalism and the emergence of technology-intensive and/or creative and cultural industries as the new ‘driving industries’ of post-Fordism (Rozentale & Lavanga, Citation2014; Tafel-Viia et al., Citation2014).

Public–private partnerships have promoted the operational and symbolic expansion of culture-led development in urban contexts, often used not only to rehabilitate former industrialized zones in decline, but also mobilized as a panacea to support broader city expansions and speculative plans. In spite of several criticisms – accusing this approach of ubiquitous diffusion, neoliberalization, elitism, and so forth (Bontje & Musterd, Citation2009) – creativity, tourism, and culture have become transversally widespread buzz words (Peck, Citation2012).

In fact, over the last few decades the ‘boosterism’ approach to tourism planning (Hall, Citation2000) has characterized multiple local agendas, drawing on ‘the untested and preconceived conclusion that the attraction of tourists has developmental benefits that exceed costs’ (Marcouiller, Citation2007, p. 28). This approach has been widely adopted in peripheral areas dealing with decreasing employment rates and declining populations, where leisure and tourism are increasingly treated as tools for stimulating regional development (Hartman, Citation2015; Meekes et al., Citation2017).

This vision has recently intertwined with the smart city ‘mantra’ theoretically aimed at achieving greater effectiveness in managing local service demand in different domains, tourism included. However, in some cases this combination has proven to foster socio-economic inequalities and cultural polarizations, as well as new forms of marketization stemming from the assemblages of neo-liberal governance (Söderström et al., Citation2014).

3. METHODS AND CASE STUDY AREA

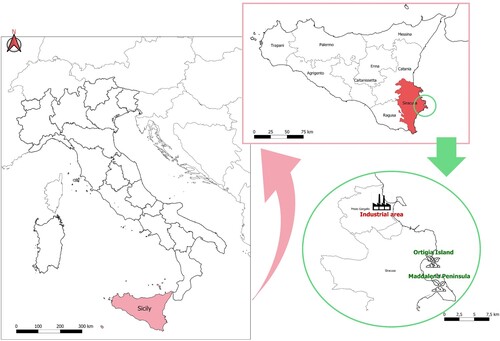

Our study took place in the eastern coast of Sicily, namely the province of Siracusa, a UNESCO-listed area globally renowned for its extraordinary environmental, archaeological and cultural heritage (). In order to scrutinize the vicious circles shaping the development dynamics of the area and urban centre–industrial pole relationships as well as the dead ends they lead to, this article adopts an exploratory case study approach (Streb, Citation2010).

Figure 1. The case study area.

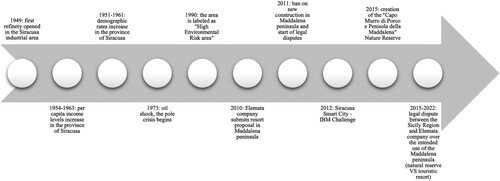

First, we conducted archival research on the history of industrialization in the area, drawing on environmental and urban history literature by scholars such as Vittorini (Citation1971), Adorno (Citation2014) and Nucifora (Citation2011, Citation2017a, Citation2017b). We also conducted an in-depth exploration of a varied set of secondary data such as city reports, strategic plans developed by the Siracusa local municipality, regional laws and documents related to ongoing legal disputes about the Elemata Company’s plan to build a new tourist resort ().

Table 1. Secondary informational sources.

As far as newspaper sources, we carried out keyword research in the digital archive of some national and regional newspapers covering the last 12 years to retrace the most recent history of the area, starting from the proposal to build a new tourist resort in the area launched in 2010 by a Netherlands-based company, Elemata Group. The combination of words were: Siracusa AND sviluppo turistico; Siracusa AND impatto ambientale; Siracusa AND resort turistico; Maddalena Peninsula AND resort turistico; Elemata AND resort. From the entire corpus of 44 items, we eventually selected the most relevant 18 articles (see the supplemental data online).

We carried out 20 periods of fieldwork from 2014 to 2019 in Siracusa as well as two towns in the province (Priolo and Augusta) located near the industrial pole. During the fieldwork, we conducted interviews with 12 key informants (KIs). We selected this qualitative method since it is exploratory in nature, usually involving a small number of individuals selected on a non-probability basis with the aim of gaining in-depth impressions of a specific topic. In particular, the main purpose of KI interviews is to collect information from a range of experts and/or representatives of a wider category who have first-hand ‘special and expert’ knowledge about the research topic (Taylor & Blake, Citation2015, p. 153) and can enable researchers to gain access to communities as well as support them in identifying additional research participants (Bogner et al., Citation2009, p. 2). As a result, we started the formation of the sample on a purposive basis by creating an initial list of potential KIs. A total of six out of 16 were shortlisted on the basis of specific criteria: environmental activists, trade union representatives, local politicians, company personnel and municipal experts. All the shortlisted KIs agreed to be interviewed, so we asked each respondent to indicate another potential participant on a linear snowballing sample basis, for a total of 12 KIs (). The interviewers explained the aims and steps of the research design to all the respondents; the research participants declared they were comfortable with these aims and agreed to proceed with an in-depth interview without the need for anonymity, considering they were already publicly engaged in discussions about these topics.

Table 2. Key informants and main interview scheme.

The unstructured interviews had different durations, ranging from 45 to 60 min, and were focused on understanding the respondents’ views on the impact of industry-driven strategies and the current clash between tourism-led development and environmental protection. The interview design was readapted for each interview according to the specific knowledge of the respondent. Finally, three fieldwork studies were conducted in which the researchers participated in public meetings using participant observation.

4. THE HISTORIC EVOLUTION OF THE AREA, FROM PERIPHERY TO CORE

The province of Siracusa was selected as a site to apply the post-war development strategy aimed at reducing the long-entrenched development gap affecting the country since its 1789 unification in which northern regions became prosperous while the agriculture-based southern regions, belonging to the so-called Mezzogiorno, remained depressed and backward (Dematteis, Citation1999).

The ambitious, capital-intensive, industry-led modernizing plan was reinforced – ideologically and economically – by the reconstruction funds of the Marshall Plan and, in the case of Sicily, also by regional funds allocated in the political–financial framework of the Cassa per il Mezzogiorno (Funds for the South), a national entity appointed to carry out extraordinary public works in southern regions (SVIMEZ, Citation1949). On a theoretical level, the development programme was part of New Meridionalismo (Saraceno, Citation1986), a new political–economic approach formulated to solve the long-entrenched north/south divide. The state-led, large-scale industrialization programme was thus aimed at stimulating economic development by focusing on selected ‘growth poles’ of capital-intensive ‘propulsive’ industries located mainly in the coastal areas, one of which was Siracusa province.

In 1949, the first refinery was built on the coast stretching nearly 32 km between the cities of Augusta and Siracusa. This area was selected for geo-economic and geopolitical reasons – its strategic location along the Mediterranean/Middle East routes – in addition to some place-based advantages: both environmental, such as the abundance of groundwater necessary for processing, and socio-technical and political, such as low labour costs and the financial windfalls ensured by the region’s autonomous status (Benadusi, Citation2018).

During the peak expansion period, the entire industrial settlement covered an area of 2700 ha and represented one of the largest petrochemical poles in Europe (Adorno, Citation2007b). Between 1954 and 1963, the per capita income of the area increased from 134,196 to 326,168 lire to rank first among all the southern regions. From 1959 onwards, per capita net income increased by 12% compared with 8.5% for Sicily as a whole. In the decade 1951–61, the area underwent a significant increase in population due to internal migratory flows (7.05% compared with 5.22% for Sicily and 6.54% for Italy) and the employment rate increased by 7.13%, with 13,000 employers in the petrochemical pole (Vittorini, Citation1971). Viewed through the lens of polarization theories, therefore, the ‘propulsive’ drive of the oil industry succeeded in triggering a development process that transformed a rural, remote, marginal periphery into a core of Mediterranean commercial flows and geopolitical networks.

The area enjoyed two decades of growth in employment, income and consumption levels accompanied by a few expressions of dissent and mild attempts at resistance by stakeholders concerned about the environmental impact (Nucifora, Citation2011). Shortly, however, it was struck by a severe crisis due to the international oil industry shock of the 1970s. New plant construction was halted along with the creation of new job opportunities. The progressive drop in employment rates revealed the extent to which the exogenous-driven model of post-war development was failing in the long term. Against the backdrop of emerging concerns about the industry’s terrifying environmental impact, the 1980s and 1990s were marked by an inexorable and abrupt decline that once again carried the area from a centralizing, dominant position to progressive peripheralization: from core back to periphery.

4.1. From core to periphery

The downward trend therefore started in the mid-1970s, intersecting with the deterioration of the chemical sector. The intensity of the crisis and its ubiquity throughout the province of Siracusa was exacerbated by the typically monocultural structure of the pole, lacking flexibility and unable to meet the challenges posed by transformations in the global production system (Adorno, Citation2007a; Ruggiero, Citation1995). According to growth pole models, the so-called ‘propulsive industries’ should have slowed down and fostered the development of a new entrepreneurial environment (Salerno, Citation2018; Trigilia, Citation1992). As Dematteis (Citation1994) argues, however, petrochemical industries are by their very nature ‘not very propulsive’ as they are not very inclined to connect up with the local production system and generate the horizontal spillover effect that in Siracusa, but also other regions of southern Italy, should have led to a more stable and diversified economic system.

As the industrialization process matured, people in the area gained a gradual but dramatic awareness of the environmental disaster the pole represented, manifested in several tragic accidents (Adorno, Citation2007b) but also in a chronic and latent way (Benadusi, Citation2018) as the industry insinuated itself into the lives of inhabitants, animals and plants to emerge in the form of disease, tumours and genetic malformations (Ruggiero, Citation2017). As a result, in 1990 the national government declared the whole area a ‘High Environmental Risk Area’ and later, owing to the presence of several pollutants, a ‘Site of National Interest’ (SIN) to be targeted with an industrial remediation strategy. Over the years, environmental associations have defined the area ‘the triangle of death,’ while P.P., the Augusta parish priest who has read the names of local cancer victims out loud from the pulpit every last Sunday of the month since 2013, does not hesitate to define this case of industrial development as an ‘industrial holocaust’ (Benadusi, Citation2018).

This industrial decline highlighted the pole’s failure as a model of not only economic development but also social relations. Although initially the area experienced a sharp increase in income levels (Adorno, Citation2014; Trigilia, Citation2014), the industrial experience, according to some scholars (Benadusi, Citation2018; Rizza, Citation2019; Saitta, Citation2011), did not introduce any modernity; rather, it exploited pre-existing unequal social relations by imposing a colonial-type model of civilization.

In particular, a typical centre–periphery dualism emerged from the industrialization process that fostered a clear distinction between the ‘lucky’ few who worked in the factories and those who remained outside, condemned to conditions of poverty and backwardness (Hytten & Marchioni, Citation1970).

This ‘accelerated modernization’ (Benadusi, Citation2018, p. 51) and ‘sudden opulence’ (Saitta, Citation2011, p. 271) in a general context of backwardness did not fuel any real social progress or ‘mature workers’ consciousness’ among the peasants who entered into waged labour (Nucifora, Citation2017b, p. 73) but instead nurtured forms of over-consumption. The increase in industrial workers’ incomes resulted in a race to acquire status symbols such as second homes, cars and televisions (Benadusi, Citation2018). In the absence of specific regulations, urbanization grew in an uncontrolled, spontaneous way and unauthorized buildings proliferated. Some of these construction projects were never completed, as the industry-driven well-being was as sudden as it was ephemeral, leaving behind a landscape of degradation and desolation.

4.2. The ‘undoing of industrial trauma’ and emergence of a new tourist rhetoric

The collapse of this large-scale industry halted the development cycle and was perceived as a set of crises involving the development model, employment levels, and the environment all at the same time (Adorno, Citation2007b; Salerno, Citation2018; Trigilia, Citation2014). On the one hand, this fuelled distrust towards the industrial model. People began using the expression ‘cathedral in the desert’ to describe an industrial experience in which the investment choices of large companies were largely detached from the needs of the local context, mirroring the failure of the exogenous and dissipative model of the Cassa per il Mezzogiorno on which the industrialization had been founded (Nucifora, Citation2017a; Trigilia, Citation2014). On the other hand, it contributed to constructing the rhetoric of tourism as a sustainable and eco-compatible alternative to industrial development.

The ephemeral benefits brought about by industrialization were sufficient to make people forget the harshness of the pre-industrial past and encouraged an ‘ideological nostalgia’ intertwined with a ‘rhetorical overestimation of the tourist resources’ (Nucifora, Citation2017a, p. 73) that resembled a collective ‘undoing’ aimed at removing industry from public narratives. The power of this new rhetoric of tourism development in the nineties was comparable to the exaltation that the prospect of industrialization had aroused among the political class in the post-war period (Nucifora, Citation2017a).

The industrial failure and shift towards tourism marked the return of discursive practices and apparatuses aimed at painting the area as peripheral, marginal, and in need of receiving foreign capital to activate trajectories of economic development. This rhetoric, like the one that had served to justify the establishment of the industrial plants in the past, gave rise to an emergency-response mentality within which it seemed necessary to take action without hesitation and as quickly as possible to solve the area’s serious development delay. Like the patrons of the petrochemical companies during the industrialization period, those prepared to invest in the area had to be seen as benevolent capitalists and their investment intentions as opportunities that simply could not be missed lest potential capital flee from the area.

In this context, a phase of ‘analysing the traumas of industrialization’ would have been crucial to open up a wider debate in which local stakeholders at different levels might weigh in on the future of the petrochemical pole, namely its disposal, restructuring, or reclamation. What happened instead was a process of ‘removing’ the industrial experience tout court, as in the psychanalytic defence mechanism first outlined by Freud.

Today, Siracusa perceives itself as a city and tourist destination. The territory is split in two, with the city on one side and the petrochemical plants on the other. The problems of the pole, concerning its conversion and revitalization, are also due to this detachment (P.S., trade union representative, our interview 2016).

L.M., who in 2014 worked as a consultant for the Municipality of Siracusa, acknowledged that Siracusa and the industrial area are closely linked. At the same time, however, he explained that such ‘removal’ is not a new phenomenon given that, ‘unlike the other municipalities of the pole (Priolo, Melilli, Augusta) that have received more returns in terms of investments but also “poisons”, Siracusa has never perceived itself as being in synergy with the industrial area’ (our interview 2014).

The petrochemical connection is therefore eliminated from debates over options for the development of this area. In a subtler way, however, it plays a role in (re)producing the discursive practices employed to promote tourism as a panacea. The petrochemical connection becomes a part of constructing a ‘new wave’ of tourism, framed as an inconvenient element from which to distance oneself, a symbol of failure, environmental deterioration and the decline of the local area.

Tourism is becoming the new monoculture; we have passed from an agricultural monoculture (in the pre-industrial phase) to the industrial [one] and, today, to a tourism-based monoculture. This is due to the fact that everyone wants to start a tourism-based business. However, it is not clear how this idea can survive without acknowledging the presence of a nearby industrial plant with all its environmental problems, but also with its enormous baggage of knowledge and economic opportunities. (L.M., our interview 2014 )

While many of the issues concerning the pole remain unresolved – such as whether to demolish facilities or relaunch the still-existing 20 active plants, as well as the 1995 clean-up plan that has remained largely un-implemented (Ruggiero, Citation2017) – an anti-industrial feeling has spread throughout the area (Benadusi, Citation2018), fuelling not only environmental justice movements but also this new rhetoric of tourism-led development.

The environmental catastrophe has, in fact, been used as a discursive tool to assert the need for Siracusa to leave its industrial past behind and move towards tourism-led development, automatically and intrinsically deemed to be sustainable and of low environmental impact. L.M. (2014) defines this removal of the petrochemical legacy as ‘short-sighted and schizophrenic’ and underlines that, even if not everyone wants to acknowledge it, one of the links between Siracusa and the pole lies in pollution itself: ‘pollution is not subject to administrative boundaries and Siracusa, even though it refuses to become aware of it, is always above the limits set for particulates’. In recalling the accident involving an oil tanker stranded off the northern border of the city of Siracusa, L.M. underlines that ‘if something happened there, the whole image of the tourist city would be inevitably destroyed’ (emphasis added).

The idea of the ‘tourist city’ is further reinforced through the new high tech ‘fantasies’ (Massey et al., Citation1991) provided by smart city models. In 2012, Siracusa took part in IBM’s Smartest Cities Challenge and was selected along with 100 other cities around the world. As a prize, the IBM Foundation sent a team of six US and European experts to Siracusa. After a three-week stay and face-to-face encounters with city stakeholders, this team produced a report providing advice and guidelines on how to develop smart city strategies, potentially by purchasing IBM-produced smart city products (Ruggiero & Di Bella, Citation2016).

The final report (IBM, Citation2012) of the IBM experts, a ‘sort of strategic plan’ (L.M., 2014) detailed how the quality of city services could be improved for both tourists and residents and, capturing the city’s detachment from the petrochemical plants, advised a kind of reconnection encompassing both challenging and resource-rich aspects.

Environmental damage and other negative outcomes associated with the petrochemical industry have separated the natural link between the major employers [the companies of the petrochemical pole] and the vitality of the city where the workers live. The team’s recommendations noted how positive it would be for the city to integrate industry more into the wider community of Siracusa, a community that actively seeks to grow in other areas as well. … The city should begin to benefit from an area [the petrochemical pole] that is striking for its highly visible impact on the landscape even if it formally remains outside the city limits. (IBM’s Smarter City Challenge, Siracusa, Final Report 2012, p. 40)

Despite these recommendations, the way the smart city model has been implemented in Siracusa has disregarded the presence of the petrochemical plant and aims instead to develop Siracusa as a tourism destination by creating a ‘techno-tourist’ image for the city. A number of projects have been launched to collect data and improve tourists’ experience of the city’s cultural heritage, but their outcomes have proved controversial (Graziano & Privitera, Citation2020).

4.3 . The ‘reconstruction’ of the area as a periphery in need of investment

The factors behind the decision to rely on touristic development are not only local. Since the 1980s, in response to the crisis of the Fordist production system, new ‘soft’ development paradigms based on tourism, sustainability, culture, and new technologies have been circulating and spreading internationally (Amin, Citation1994). Their territorialization in the local context has depended in part on the availability of European Structural Development Funds provided through new, locally negotiated project-based planning tools. These new tools have proven to be of little use or even counterproductive, however, in terms of solving the crisis-ridden issues of the petrochemical industry (transformation and/or relaunch), issues that certainly could not be solved or managed exclusively by local levels of governance.

In the Siracusa area, the partnership mechanism forced local authorities to join together on the basis of specific, strategic, local development projects. In most cases, the projects, ‘characterized by the instability of the coalitions and the inconsistency of the proposals’, focused on tourism and cultural revitalization (Nucifora, Citation2017b, p. 74). ‘The analysis of territorial resources tended, in many cases, almost to deny the evidence of a vast petrochemical center along the entire coast’ (p. 74). Attempts at building large-scale tourist infrastructural projects on the Maddalena peninsula, along the south coast of Siracusa, are to be understood as positioned in this context, where the new rhetoric of tourism development intersects with ‘planning by projects’ and the search for a new, competitive urban positioning.

The history of tourism-sector investment in this area, characterized by extraordinary environmental richness and landscape value, has been marked by heated conflict between external investors (supported by local economic and political interests) and the bottom-up environmental movements mobilized around the collective SOS Siracusa. A preliminary but decisive step towards facilitating tourism urbanization in the Maddalena area was made in 2007 when the existing urban planning rules banning large-scale tourism-led projects were altered to make them more flexible. In particular, the 2007 Master Plan of Siracusa removed a clause requiring tourism investment to be approved by all the landowners in the area. Land ownership in this area was extremely fragmented, and this clause had effectively paralysed any large-scale development planning. According to SOS Siracusa, by deploying arguments about tourism revival and sustainability, the new master plan was intended to facilitate a number of real estate development projects in environmentally sensitive areas and allow the construction of large tourist facilities on the coast.Footnote1 The local Green Party leader and founder of WWF Siracusa echoes this observation: ‘the WWF was the first to denounce the harmful impacts of the master plan, adopted in 2007 by the city of Siracusa, that would have allowed the construction of 8 tourist villages, most of them on the coast’ (G.P., our interview 2018).

Disputes over tourism-oriented urbanization projects have been ongoing since 2010, when Elemata – an Amsterdam-based real estate company that had purchased land along the coast – submitted a proposal to the Siracusa building commission to build a luxury resort in the Maddalena area. The construction of the resort, described as ‘a 1,500 euro per night resort with eco-Babylonian style roof gardens on the roofs overlooking Ortigia’Footnote2 would have blocked public access to the sea along one of the Maddalena peninsula’s most beautiful stretches of coastline. After a number of legal battles, the SOS Siracusa collective was able to initiate proceedings to establish a nature reserve in this area entailing a ban on any new construction ().Footnote3

Attempts to urbanize the Maddalena peninsula have been supported by a rhetorical structure very similar to the one used to justify the localization of exogenous capital during the previous industrialization phase. Indeed, the whole Siracusa area is once again framed as peripheral and marginal, with real estate investments thus representing a chance for redemption the area cannot afford to miss out on.

In this context, stakeholders such as entrepreneurial associations (‘Confindustria’) and local politicians interpret protests by environmental movements and alternative proposals for developing the area (such as establishing the nature reserve) as a serious obstacle that risks jeopardizing efforts to valorize the local area by attracting financial capital; such capital is in turn cast as highly mobile and flexible, in danger at any moment of being directed at some other local area instead.Footnote4 Viewed in this way, the loss of such capital would not only cripple current development plans but also jeopardize potential future investment, as investors would view Siracusa as an area where private enterprise is not sufficiently protected, causing the city to miss out on important opportunities for development down the line.

Figure 2. Timeline of the most relevant events in the area

This story [the attempts to create the Maddalena nature reserve] would put Siracusa in a bad light on a global scale, no one would come here to invest. And our assets, our coastline, will end up giving nothing to anyone: to our young people looking for work, to our producers of quality food. Everyone will be discouraged, and we will all lose. (T.R., our interview 2018)

5. DISCUSSION AND FINAL CONSIDERATIONS

Through the use of a historical perspective in analysing the transformation of the economic landscape of south-eastern Sicily, the article contributes to an ongoing discussion insisting on the need to overcome presentism in regional and geographical studies and provides tools for a thorough understanding and assessment of local economic policies.

By adopting a historical sensibility, this research has been able to identify recurrent narratives of the area as a periphery and bring into focus the failures of post-war industrialization strategies. The concept of periphery was mobilized in the post-war years at national and regional levels to promote top-down experiments of ‘industrialization as modernization’ in the area. Although for many years what Benadusi (Citation2018) has termed the ‘miracle of oil’ was hailed as a ‘chance for redemption’ drenched in a pervasive mythology of progress, this phenomenon completely disrupted long-established relations among the local area, local communities, land use, cultural heritage, and socio-economic traditions. Narratives of underdevelopment, built on images of a primitive past involving backwardness, immobility, and the poverty of an agriculture-based society, went hand in hand with counter-narratives of wealth, modernity, and civilization through incorporation in the globalized petrochemical sector.

Almost 70 years after having acknowledged the failure of top-down strategies, the discourses of local politicians and economic elites have again begun representing the area as a periphery so as to encourage the attraction of foreign investment in the form of large-scale tourism complexes. Disaster-focused representations of the historical past are used to argue that the area needs ‘low-environmental – impact rescue interventions’ in the field of tourism driven by external capital.

By reinterpreting the Freudian metaphor of ‘undoing,’ the article has highlighted how tourism operates in the area under investigation as a symbolic meta-policy frame aimed at enabling and normalizing exogenous-led neoliberal development through the systematic ‘removal’ of industrialization from discourses and planning schemes. And yet this form of ‘collective undoing’ serves to legitimate narratives of development that are actually quite similar to those mobilized around the petrochemical sector during the post-war era. Such narratives depict exogenous investment in the tourist sector as the panacea needed to tackle peripherality and a depressed job market. It is no coincidence, indeed, that widespread rhetoric tends to cast tourism as ‘the new oil’.Footnote5 In line with the emergence of cognitive–culture capitalism and the rise of tourism as one of the new ‘driving industries’ of post-Fordism (Rozentale & Lavanga, Citation2014; Tafel-Viia et al., Citation2014), more and more emphasis is placed on tourism-led renewal programmes as ‘alternative’ approaches to local development.

As a result, by adopting an evolutionary historical perspective, the article deconstructs the recent process of touristification of the city of Siracusa by highlighting its connections – at the level of narratives and planning schemes – with the growth-pole strategy implemented here in the post-war years. In so doing, the paper provides crucial insights for a critical assessment of contemporary urban and regional policies (Castigliano, Citation2018) by highlighting how little either the failure of post-war industrialization programmes or the frictions stemming from today’s shift to tourism have been effectively integrated into a place-based economic development framework, the kind of framework that would entail the identification, mobilization, and exploitation of local potential (Vázquez-Barquero, Citation1999).

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (25.1 KB)ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors warmly thank the editors for their work, the referees’ suggestions and Professor Francesca Valenti for having realized the map of the case study area.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 5 March 2012; www.italianostra.org/siracusa-sos-piano-paesaggistico.

2 La Repubblica, 30 June 2017.

3 La Repubblica, 6 September 2015; La Sicilia, 17 December 2017.

4 Il Sole 24 ore, 22 November 2012; La Sicilia, 23 December 2014; Milano Finanza, 23 December 2017.

5 ‘Tourism as the Italian oil’, Il Sole 24 ore, 16 January 2020.

REFERENCES

- Adorno, S. (2007a). L'inquinamento dell'aria e dell'acqua nel polo petrolchimico di Augusta – Siracusa nella seconda metà degli anni settanta. Reti controlli e indagini ambientali. I frutti di Demetra, 15, 43–58.

- Adorno, S. (2007b). Il polo industriale di Augusta–Siracusa. Risorse e crisi ambientale (1949–2000). In G. Corona, & S. Neri Serneri (Eds.), Storia e ambiente. Città risorse e territori nell’Italia contemporanea (pp. 195–127). Carocci.

- Adorno, S. (ed.). (2014). Storia di Siracusa. Economia, politica, società (1946–2000). Donzelli.

- Amin, A. (1994). Post-Fordism. A reader. Blackwell.

- Benadusi, M. (2018). Oil in Sicily: Petrocapitalist imaginaries in the shadow of old smokestacks. Economic Anthropology, 5(1), 45–58. https://doi.org/10.1002/sea2.12101

- Bianchi, A., & Placidi, B. (2021). Rigenerare il Bel Paese. La cura di un patrimonio dismesso esconosciuto. Soveria Mannelli.

- Bogner, A., Littig, B., & Menz, W. (2009). Introduction: Expert interview—An introduction to a new methodological debate. In A. Bogner, B. Littig, & W. Menz (Eds.), Interviewing experts (pp. 1–13). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Bontje, M., & Musterd, S. (2009). Creative industries, creative class and competitiveness: Expert opinions critically appraised. Geoforum; Journal of Physical, Human, and Regional Geosciences, 40(5), 843–852. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2009.07.001

- Boukhris, L. (2017). The Black Paris project: The production and reception of a counter-hegemonic tourism narrative in postcolonial Paris. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 25(5), 684–702. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2017.1291651

- Büscher, B., & Fletcher, R. (2017). Destructive creation: Capital accumulation and the structural violence of tourism. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 25(5), 651–667. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2016.1159214

- Castigliano, M. (2018). Report on inaugural workshop RSA ReHi-Network ‘Interdisciplinary connections between history & regional studies’. Planning Perspectives, 33(2), 289–292. https://doi.org/10.1080/02665433.2018.1441068

- Copus, A. K. (2001). From core–periphery to polycentric development: Concepts of spatial and aspatial peripherality. European Planning Studies, 9(4), 539–552. https://doi.org/10.1080/09654310120049899

- Crone, M. (2012). Re-thinking ‘peripherality’ in the context of a knowledge-intensive, service-dominated economy. In M. Danson, & P. De Souza (Eds.), Regional development in Northern Europe. Peripherality, marginality and border issues (pp. 49–64). Routledge.

- Dansero, E., Emanuel, C., & Governa, F. (2003). I patrimoni industriali. Una geografia per lo sviluppo locale. Franco Angeli.

- Dematteis, G. (1994). Le trasformazioni territoriali e ambientali. In F. Barbagallo (Ed.), Storia dell’Italia repubblicana (pp. 660–709). Einaudi.

- Dematteis, G. (ed.). (1999). Il fenomeno urbano in Italia: Interpretazioni, prospettive, politiche. Franco Angeli.

- Devine, J., & Ojeda, D. (2017). Violence and dispossession in tourism development: A critical geographical approach. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 25(5), 605–617. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2017.1293401

- Devine, J. A. (2017). Colonizing space and commodifying place: Tourism's violent geographies. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 25(5), 634–650. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2016.1226849

- Dijkstra, L., Garcilazo, E., & McCann, P. (2015). The effects of the global financial crisis on European regions and cities. Journal of Economic Geography, 15(5), 935–949. https://doi.org/10.1093/jeg/lbv032

- Fischer-Tahir, A., & Naumann, M.2013). Peripheralization. The making of spatial dependencies and social injustice. Springer VS.

- Freud, S. (1909). Notes upon a case of obsessional neurosis. In Standard edition (Vol. X, pp. 155–320). Hogarth Press.

- Garretsen, H., & Martin, R. (2010). Rethinking (New) economic geography models: Taking geography and history more seriously. Spatial Economic Analysis, 5(2), 127–160. https://doi.org/10.1080/17421771003730729

- Gibson, C. (2021). Critical tourism studies: New directions for volatile times. Tourism Geographies, 23(4), 659–677. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616688.2019.1647453

- Graziano, T., & Privitera, D. (2020). Cultural heritage, tourist attractiveness and augmented reality: Insights from Italy. Journal of Heritage Tourism, https://doi.org/10.1080/1743873X.2020.171.9116

- Hall, C. M. (2000). Tourism planning: Policies, processes and relationships. Prentice Hall.

- Hartman, S. (2015). Towards adaptive tourism areas? A complexity perspective to examine the conditions for adaptive capacity. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2015.1062017

- Henning, M. (2019). Time should tell (more): Evolutionary economic geography and the challenge of history. Regional Studies, 53(4), 602–613. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2018.1515481

- Herrschel, T. (2011). Regional development, peripheralisation and marginalization and the role of governance. In T. Herrschel, & P. Tallberg (Eds.), The role of regions? Networks, scale, territory. Kristianstad Boktryckeri.

- Hincks, S., Deas, I., & Haughton, G. (2017). Real geographies, real economies and soft spatial imaginaries: Creating a ‘More than Manchester’ region. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 41(4), 642–657. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2427.12514

- Hincks, S., & Powell, R. (2022). Territorial stigmatisation beyond the city: Habitus, affordances and landscapes of industrial ruination. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 54(7), 1391–1410. https://doi.org/10.1177/0308518X221107022

- Hoole, C., & Hincks, S. (2020). Performing the city-region: Imagineering, devolution and the search for legitimacy. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 52(8), 1583–1601. https://doi.org/10.1177/0308518(20921207

- Hytten, E., & Marchioni, M. (1970). Industrializzazione senza sviluppo: Gela una storia meridionale. Franco Angeli.

- Iammarino, S., Rodriguez-Pose, A., & Storper, M. (2019). Regional inequality in Europe: Evidence, theory and policy implications. Journal of Economic Geography, 19(2), 273–298. https://doi.org/10.1093/jeg/lby021

- IBM. (2012). IBM’s smarter cities challenge. Siracusa. Rapporto finale. IBM. http://www.smartercitieschallenge.org/applications/siracusa-italy-summary-2012.pdf, retrieved on December, 2020.

- Kolasa-Nowak, A. (2019). The importance of history in regional studies: The role of the past in Polish regional sociology after 1989. Ruch Prawniczy, Ekonomiczny i Socjologiczny, 81(4), 239–252. https://doi.org/10.14746/rpeis.2019.81.4.18

- Kühn, M. (2015). Peripheralization: Theoretical concepts explaining socio-spatial inequalities. European Planning Studies, 23(2), 367–378. https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2013.862518

- Lang, T. (2012). Shrinkage, metropolization and peripherization in East Germany. European Planning Studies, 20(10), 1747–1754. https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2012.713336

- Lazzeroni, M., & Grava, M. (2021). Dalle fabbriche ai nuovi spazi dell’innovazione: Transizioni socio economiche e mutamenti dei paesaggi della produzione. Rivista Geografica Italiana, 45–72. https://doi.org/10.3280/rgioa4-2021oa12959

- Maes. (2007). The spread of Keynesian economics: A comparison of the Belgian and Italian experiences. NBB Working Paper, 113.

- Marcouiller, D. (2007). Boosting tourism as rural public policy: Panacea or pandora’s box? Regional Analysis and Policy, 37(1), 28–31.

- Massey, D., Quintas, P., & Wield, D. (1991). High-Tech fantasies. Science parks in society, science and space. Routledge.

- McCann, P., & van Oort, F. (2019). Theories of agglomeration and regional economic growth: A historical review. In R. Capello, & P. Nijkamp (Eds.), Handbook of regional growth and development theories (pp. 6–23). Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Meekes, J., Buda, M., & de Roo, G. (2017). Adaptation, interaction and urgency: A complex evolutionary economic geography approach to leisure. Tourism Geographies, 19(4), 525–547. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616688.2017.1320582

- Moretti, E. (2012). The new geography of jobs. Houghton Miffling Harcourt.

- Nucifora, M. (2011). Il paesaggio della storia. Patrimonio, identità territorio nella Sicilia sud orientale. Bonanno, Acireale-Roma.

- Nucifora, M. (2017a). Il racconto della deindustrializzazione. La dimensione locale, tra stigmatizzazione e patrimonializzazione del passato industriale. In M. Meli, & S. Adorno (Eds.), Il futuro del polo petrolchimico siracusano. Tra bonifiche e riqualificazione.

- Nucifora, M. (2017b). Le ‘sacre pietre’ e le ciminiere. Sviluppo industriale e patrimonio culturale a Siracusa (1945–1976). Franco Angeli.

- Paasi, A. (2013). Regional planning and the mobilization of ‘Regional Identity’: From bounded spaces to relational complexity. Regional Studies, 47(8), 1206–1219. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2012.661410

- Parr, J. B. (1999a). Growth-pole strategies in regional economic planning: A retrospective view. Part 1. Origins and advocacy. Urban Studies, 36(7), 1195–1215. https://doi.org/10.1080/0042098993187

- Parr, J. B. (1999b). Growth-pole strategies in regional economic planning: A retrospective view. Part 2. Implementation and outcome. Urban Studies, 36(8), 1247–1268. https://doi.org/10.1080/0042098992971

- Peck, J. (2012). Recreative city: Amsterdam, vehicular ideas and the adaptive spaces of creativity policy. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 36(3), 462–485. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2427.2011.01071.x

- Perroux, F. (1955). Note sur la notion de ‘pôle de croissance’. Economie appliquée VII, 1–2, P.N.

- Pescatore, G. (2008). La ‘Cassa per il Mezzogiorno’. Un’esperienza italiana per lo sviluppo. Il Mulino.

- Pociūtė-Sereikienė, G. (2019). Peripheral regions in Lithuania: The results of uneven development. Regional Studies, Regional Science, 6(1), 70–77. https://doi.org/10.1080/21681376.2019.1571437

- Raffestin, C. (2006). L’industria: dalla realtà materiale alla ‘messa in immagine’. In E. Dansero, & A. Vanolo (Eds.), Geografia dei paesaggi industriali in italia. Riflessioni e casi di studio a confronto (pp. 19–36). Franco Angeli.

- Rizza, M. O. (2019). La vicenda della riserva della penisola della Maddalena a Siracusa. Molto rumore di democrazia e mercato. Mediterranean Journal of Human Rights, 287–341. https://doi.org/10.4399/97888255201709

- Rozentale, I., & Lavanga, M. (2014). The ‘universal’ characteristics of creative industries revisited: The case of Riga. City, Culture and Society, 5(2), 55–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ccs.2014.05.006

- Ruggiero, L. (2017). Il fallimento di un modello di sviluppo e l’arduo percorso per il risanamento ambientale. Notabilis, 6(VIII), 17–21.

- Ruggiero, L., & Di Bella, A. (2016). Néolibéralisme et Développement urbain dans l’Italie du Sud: le modèle «IBM smart city» dans la ville de Syracuse. In H. Ter Minassian (Ed.), Penser la fabrique de la ville en temps de crise(s) (pp. 61–70.

- Ruggiero, V. (1995). L’inconsistenza dei sistemi locali e la fragilità dei nuovi progetti di sviluppo industriale in Sicilia. In F. Dini (Ed.), Geografia dell’Industria. Sistemi locali e processi globali (pp. 299–314). Giappichelli.

- Saitta, P. (2011). Il consenso e l’industria. Storia e usi dello spazio nelle indagini sulle aree a rischio. Culture Della Sostenibilità, IV(8), 264–275.

- Salazar, N. B. (2017). The unbearable lightness of tourism … as violence: An afterword. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 25(5), 703–709. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2017.1293405

- Salerno, F. (2018). Siracusa: un polo di sviluppo industriale per la crescita del Meridione. Clionet. Per un senso del tempo e dei luoghi, 2. Retrieved July 29, 2020, from https://rivista.clionet.it/vista.clionet.it/it/vol2/societa-e-cultura/paesaggi/salerno-siracusa-un-polodi-sviluppo-industriale-per-la-crescita-del-meridione

- Saraceno, P. (1986). Il nuovo meridionalismo. Istituto italiano per gli studi Filosofici.

- Söderström, O., Paasche, T., & Klauser, F. (2014). Smart cities as corporate storytelling. City, 18(3), 307–320. https://doi.org/10.1080/13604813.2014.906716

- Storper, M. (2013). Keys to the city: How economics, institutions, social interaction, and politics shape development. Princeton University Press.

- Streb, C. K. (2010). Exploratory case study. In J. Mills, G. Durepos, & E. Wiebe (Eds.), Encyclopedia of case study research (pp. 372–373). SAGE Publications.

- SVIMEZ. (1949). Contributi allo studio del problema industriale del Mezzogiorno. SVIMEZ.

- Tafel-Viia, K., Viia, A., Terk, E., & Lassur, S. (2014). Urban policies for the creative industries: A European comparison. European Planning Studies, 22(4), 796–815. https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2013.772755

- Taylor, G. A., & Blake, B. J. (2015). Key informant interviews and focus groups. In M. De Chesnay (Ed.), Nursing research using data analysis. Qualitative designs and methods in nursing (pp. 153–165). Springer.

- Trigilia, C. (1992). Sviluppo senza autonomia. Effetti perversi delle politiche nel Mezzogiorno. Il Mulino.

- Trigilia, C. (2014). Prefazione. In S. Adorno (Ed.), Quot. (pp. 4–8).

- Vall, N. (2011). Cultural region. North east England 1945–2000. Manchester University Press.

- Vazquez-Barquero, A. (1999). Inward investment and endogenous development. The convergence of the strategies of large firms and territories?. Entrepreneurship and Regional Development, 11(1), 79–93. https://doi.org/10.1080/089856299283308

- Vittorini, M. (1971). Raffinerie e porti petroliferi in italia. Urbanistica, 58.

- Zarycki, T. (2007). History and regional development. A controversy over the ‘right’ interpretation of the role of history in the development of the Polish regions. Geoforum; Journal of Physical, Human, and Regional Geosciences, 38(3), 485–493. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2006.11.002