ABSTRACT

Federal conservation programmes compensate property owners and farmers for sustained land-use practices which generate ecosystem services, yet enrolling participants can be a challenge. This paper studies that challenge in order to understand what values drive enrolment patterns in the Columbia River basin in the US Northwest, a region designated as a Critical Conservation Area by the US Department of Agriculture. Utilizing a relational values framework, the dynamics of the federally administered Conservation Reserve Program are explored. Findings are revealed through qualitative coding and analysis of semi-structured interviews and visual artefacts from programme participants, government employees and university-affiliated extension knowledge holders. This study concludes that five key relational values inform enrolment in this region beyond monetary reasons: stewardship, care, kinship, responsibility and identity. This paper posits that integrating information regarding relational values into federally administered conservation programmes may lead to more resilient and sustainable social–ecological systems.

1. INTRODUCTION

As environmental degradation and climate change continue to pose greater challenges throughout the world, federal governments are becoming increasingly active in delivering regionally focused conservation policies that rely on community cooperation (da Silva et al., Citation2021). These targeted conservation policies are typically meant to ameliorate some of the issues that arise from previous ecologically destructive land-use activities while often trying to reconcile local development goals and aspirations (Jain, Citation2022). This tension (and opportunity) between economic prosperity and the protection of natural resources makes multi-scalar government conservation policies particularly revelatory. While there have been calls for ‘significant investments in public and private lands conservation’ (Dreiss & Malcom, Citation2022, p. 1), there appears to be a pressing need to understand what values inform public–private participation in federally administered and regionally operationalized conservation programmes in order to maximize these future investments.

Through a case study of the Columbia River basin in the US Northwest, a region designated as a Critical Conservation Area by the US Department of Agriculture (USDA), this article addresses the question of what values, beyond monetary, inform enrolment dynamics in the Conservation Reserve Program (CRP). The CRP has been one of the dominant federal soil conservation programmes in the United States ever since its inception in 1985, and even though its acreage enrolment cap is currently growing (Johnson et al., Citation2019), that cap is rarely reached (Lehner & Rosenberg, Citation2021). Thusly, information that can assist with understanding enrolment dynamics is valuable. Using qualitative data from interviews and visual artefacts, while incorporating the concept of relational values (Chan et al., Citation2016, Citation2018), this paper proposes that five specific relational values are significant to understanding enrolment in the CRP in the US Northwest: stewardship, care, kinship, responsibility and identity.

The remainder of this paper describes in further detail the concept of relational values, the methodology and case study, and how the findings herein can be relevant in terms of theory, practice and policy.

2. RELATIONAL VALUES

Relational values, as an alternative to dualistic notions of intrinsic and instrumental values, have been offered as a way to better understand the complexity of social–ecological systems (Chan et al., Citation2016, Citation2018; Himes & Muraca, Citation2018; Norton & Sanbeg, Citation2021). As a new category of value articulation, relational values frameworks attempt to connect ‘preferences, principles, and virtues about human–nature relationships’ (Chan et al., Citation2018, p. A1) as they relate to decision-making. Instrumental notions of value typically express how something is a means to something else, with the assumption that all things are substitutable. Thusly, ‘Money, as the universal equivalent, is the most common metric of that substitutability’ (Chan et al., Citation2016, p. 1463), with even conservation programmes often being measured using market-centric ideologies and principles (Gómez-Baggethun & Ruiz-Pérez, Citation2011). Intrinsic value conceptions, on the other hand, are expressed by the belief that nature has worth beyond what it can do for society. Relational values then are more contextual, expressed as values about relationships to a thing/component of nature rather than values of a thing/component of nature. Additionally, relational values can be audited because ‘they are measurable, in the sense of the strength of commitment to an ideal or aspired relationship with nature’ (Chan et al., Citation2018, p. A6).

There are still many questions for how to best study and measure relational values (Britto dos Santos & Gould, Citation2018), with some scholars claiming that all relational values research must be place-based in order to be conceptually appropriate (Norton & Sanbeg, Citation2021). One such place-based relational values empirical study in the Otún River watershed in the central Andes of Colombia found that compared with instrumental and intrinsic values, ‘relational values were the most frequently mentioned value domain’ (Arias-Arévalo et al., Citation2017, p. 43). Furthermore, a meta-analysis of 50 studies examining social outcomes of Payments for Watershed Services programmes found that approximately half discussed relational values, even though relational values, as a term or concept, typically was absent from the examined research (Bremer et al., Citation2018). From this perspective, relational values can be seen as often present in social–ecological systems literature, even when not classified as such.

What values specifically constitute relational values, and which ones are most present within environmental research, is an ongoing discussion within the literature. Britto dos Santos and Gould (Citation2018) examined 40 papers on environmental education in peer-reviewed journals and found connectedness and stewardship to be the most common values articulated, with identity, community, kinship, care and responsibility being less widespread. Another study reviewed how relational values were considered within the biodiversity conservation in agricultural ecosystems literature from 2014 to 2017 and found stewardship and identity to be key values associated with farmer land-use decisions (Allen et al., Citation2018).

Bremer et al. (Citation2018) propose that as relational values studies become more prevalent it is important to appreciate ‘local value systems in communities where reciprocal relationships to place are central to survival, thriving, and worldview’ (p. 121). This paper adds to the existing scholarship of relational values by employing a novel methodology which works towards creating better public processes for sharing and negotiating ideas regarding conservation policies.

3. METHODOLOGY AND CASE STUDY OVERVIEW

This case study examines qualitative data from interviews, visual artefacts and secondary data. It includes 22 semi-structured interviews with CRP enrolees, government employees from the Farm Service Agency (FSA) tasked with administering the programme, and university-extension programme employees knowledgeable about conservation practices in their counties. The data collection processes were approved by an institutional ethics review in June 2021. The interviews were conducted via telephone from November 2021 to June 2022 with a number of respondents also providing visual artefacts, such as photographs and maps, via email.

Similar to other semi-structured interview protocols, the conversations with respondents were guided by a number of predefined questions, while also allowing for the exploration of unforeseen topics that arose during the interviews (Longhurst, Citation2010). Questions were altered slightly if the respondent was an FSA administrator or a university-extension programme employee rather than a farmer. The questions posed were meant to understand the non-monetary reasons for enrolment in a federally administered soil conservation programme, such as:

What has been your experience with the CRP?

What are some of the reasons you decided to enrol in the CRP?

How do you feel you are making a difference by being enrolled in the CRP?

An FSA administrator in each county was initially contacted and interviewed. Through that key respondent snowball sampling was employed in order to speak to at least three farmers in each county who were dependent on their farm for their income. Once a saturation of themes associated with values was reached, data collection from farmers and FSA employees ceased. University-extension programme employees, considered to be knowledge holders about conservation practices and their local communities, were the final respondents interviewed and their data were used to both accentuate the analysis and as a validity check on the results. There was one university-extension programme employee interviewed per state.

A summary of the respondent demographics is provided in .

Table 1. Sample and demographic information.

Additionally, nine respondents provided visual artefacts with written descriptions for consideration. Previous research has used the qualitative data collection technique of photo-elicitation combined with interviews as a tool for farmers to explain their relationships with the landscape and their community (Beilin, Citation2005; Stotten, Citation2018), and this research project builds upon those techniques in order to explore how relational values frameworks can be enhanced by multiple forms of data. Finally, analysis was complemented with the study of secondary data, including federal agency communications, county conservation reports and regional websites.

There are 24 counties in Oregon, Washington and Idaho states in the broadly defined Columbia River basin where over 7501 acres of county land are enrolled in the CRP as of October 2019 (USDA, Citation2022), and this represents the research area (). The primary agricultural activity within the region is wheat production, with some cattle ranching and winemaking also being present. The majority of the counties are sparsely populated and economically dependent on agricultural activities in addition to government subsidies in the form of commodity support and conservation practices. Tourism, forestry, academia and public administration also contribute to the economic and social landscape of the region. Four counties were randomly selected from these 24 counties in order to decrease sample bias and increase generalizability: Klickitat and Franklin counties in Washington, and Sherman and Union counties in Oregon.

4. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

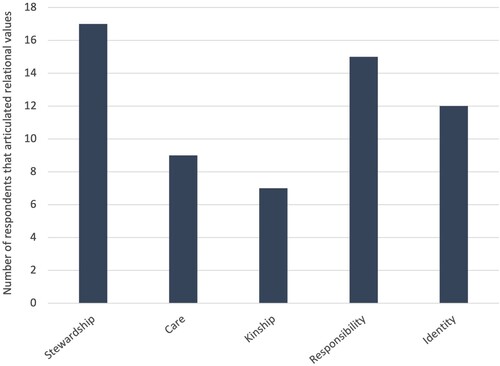

Thematic analysis was used to identify consistent points, comments or motifs from the 22 interviews transcribed. Additionally, the visual artefacts provided by nine respondents were considered in a similar fashion. The collected data were analysed with ATLAS.ti software using an iterative process of examining and re-examining each respondent’s interview and visual artefacts alongside other respondent data. This approach allows the researcher to systematize the multiple forms of data into specific emergent themes which correspond with certain relational values. Through qualitative coding and analysis, five relational values were frequently present in the interviews and visual artefacts as they relate to the land ().

Table 2. Relational values frequently present in the interviews and the visual artefacts as they relate to the land.

Below are example quotations and photographs with the relational values associated with each piece of data labelled in italics. These examples are a sampling of how thematic analysis and value coding was conducted. The quotations given beneath the photographs () were written messages delivered via email describing each of the particular pieces of visual data. The form of qualitative research employed herein is concerned with connecting the ethnographic narratives and visual motifs to the associated values. Often multiple relational values were articulated within the same data, which alludes to the intersectionality of the land within value constellations for the respondents.

Stewardship/Care/Identity

I’ve got some of the most beautiful stands of CRP grass on the breaks of the John Day River. … And I take it from the emotional standpoint. I look at the land and I remember what it looked like 40 years ago. … The guy before … ran the place to death with cows. It was just the times. (respondent 5)

Stewardship/Care/Kinship

If you’re actually doing it right, and you’re actually trying to have nice grass stands, and do what the contract says, it’s expensive. It’s really, really rewarding for me. I love it. I love to see the wildlife out in it, the birds, and the deer. I mean it’s great. Some of this ground, it shouldn’t be farmed. It should be grass. (respondent 12)

Stewardship/Responsibility

And you can drive by those pieces that are in CRP and the water running off of those fields will be fairly clean. Then I’ve had neighboring fields that come off muddy. So, there’s no question it’s not only saving soil, but it’s building soil. (respondent 7)

Care/Responsibility

See . (respondent 2)

Kinship/Identity

See (respondent 14)

Stewardship/Responsibility/Identity

See (respondent 8)

Figure 2. Expansive rolling hills with large grass stands. ‘By pulling this ground out of production, we are helping to preserve much of this land’ (respondent 2).

Figure 3. An elk chews grass in an open clearing between some conifer trees. ‘This is an elk on our CRP [Conservation Reserve Program] … licking her lips as we harvest hay’ (respondent 14).

![Figure 3. An elk chews grass in an open clearing between some conifer trees. ‘This is an elk on our CRP [Conservation Reserve Program] … licking her lips as we harvest hay’ (respondent 14).](/cms/asset/18d1d008-f391-48a5-84af-fef5a2a5c5c1/rsrs_a_2168565_f0003_oc.jpg)

Figure 4. Respondent 8 sitting in the rear of a truck flatbed and looks out over an expansive grass stand. Large clouds pepper the sky. ‘This is one that reflects the part of my job I love’ (respondent 8).

4.1. Prevalence of each relational value

displays how often respondents articulated and/or affirmed each value. If a respondent mentioned a relational value multiple times, it was only counted once. Over 90% of respondents articulated and/or affirmed at least one relational value. This high frequency for the presence of at least one relational value was seen as a validity confirmation on the research design. Stewardship and responsibility were mentioned the most frequently with kinship being the least apparent. That said, when kinship was mentioned, it was often strongly articulated. Approximately 77% of respondents’ narratives and accounts mentioned or alluded to multiple relational values, while approximately 9% of respondents did not articulate any relational values and focused mainly on monetary values.

Figure 5. Relational values articulated and/or affirmed by respondents in this research. Stewardship is the tallest bar with 17 articulations, followed by responsibility at 15, identity at 12, care at nine and kinship at seven. The sum of frequencies exceeds the sample size (22 respondents) because most respondents mentioned more than one relational value.

4.2. Exploring each relational value

Understanding the values that inform enrolment in federally administered and regionally operationalized soil conservation programmes has the potential to explain larger conservation and land-use dynamics at personal and policy levels. The analysis herein employs the Syntax of Environmental Values Framework (Deplazes-Zemp & Chapman, Citation2021) as a way of understanding these dynamics, and should be seen as one of many ways of investigating relational values.

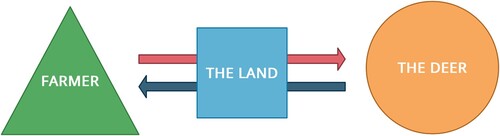

illustrates conceptually one expression in which relational values were found to be present within the research area of the Columbia River basin as they relate to enrolment in the CRP. The land is the object of which the valuing subjects (FSA administrators and farmers) attribute value. University-extension programme employees are not represented because their interviews were with regard to the values that inform enrolment and administration of the CRP, not their own values regarding the land. In aggregate the university-extension programme employees affirmed all the relational values presented in .

Figure 6. Relational values within the valuing schema of Farm Service Agency (FSA) administrators/farmers (the valuing subjects) and the land (the valued object).

The valuing process always goes from subject to object. The two arrows are meant to illustrate that relational values include aspects of instrumental (red arrow) and intrinsic (blue arrow) values but exist conceptually between these two types of values as a third category of value articulation.

The bidirectional valuing process with two objects shown in is not the only way the land was valued by respondents. illustrates another manner of valuing the land as a mediating object, for a relationship to another object. In this case, the farmer values the land as it mediates their relationship with the deer on their land. Two respondents spoke to a kinship with deer and sent photographs of deer enjoying their CRP land. Thus, these respondents articulated the relational value of kinship to both the land and the deer, which allows for a deeper understanding of the respondents' values in general. then can be seen as a template for other value constellations where the land is mediating a relationship to another object (e.g., the deer, a family member, the community, etc.).

Figure 7. A specific mediating relational value expression (kinship) displaying the valuing schema of a farmer (the valuing subject), the land and the deer on their land, with the land mediating a relationship between the farmer and the deer on their Conservation Reserve Program (CRP) land.

As noted previously, stewardship was the most frequently articulated and affirmed relational value and this appears to be in line with previous research (Britto dos Santos & Gould, Citation2018). Farmers and FSA administrators often interconnected their duty to the land as it related to their agricultural activities, their duty to provide for their families and also their conservation practices. Enrolment in the CRP was generally seen as a means for looking after the land in a more thoughtful and less extractive way. For example:

You’d like to say you’re a good steward of the land and all this, and you’re looking out for the environment and all that, but you still have to make a living and what have you. So, it kind of goes twofold … CRP is a pretty good option. (respondent 19)

A few respondents saw their CRP land as just as important as their crop-producing land, but the majority still maintained a greater sense of stewardship towards their non-CRP land. Thus, some landowners bifurcated the stewardship value within their personal valuing framework, which is notable. FSA employees tended to articulate a more holistic conception of stewardship as it related to the land. Stewardship was also the most present relational value when examining local agricultural conservation websites from each county.

Care as a relational value was mentioned by almost 41% of respondents and was mentioned by second-, third- and fourth-generation farmers – often associated with a desire to care for the land as others before them had done. A concern for aspects of the land because they matter to someone else, while not as frequently mentioned as stewardship, was almost always mentioned together by a respondent (with one exception). Care, as a relational value, has an inherent quality of connecting a respondent to another person or persons. One farmer emphatically stated it this way:

I enjoy working with the people in Klickitat County on the CRP stuff. I enjoy seeding it. Trying to make it grow. Trying to enhance it. Trying to figure out why pieces are dying out. Trying to figure out why others do better. I enjoy the whole entire challenge of the CRP program. (respondent 12)

This is a key example of a value constellation that shows how someone can value the land enrolled in CRP because it mediates a relationship with the valuer and the community.

The least frequently mentioned relational value, kinship, was often the most strongly articulated value when it was present. Interestingly, kinship was the only relational value that was disputed by a number of other respondents, many of whom went out of their way to speak disparagingly of wildlife on CRP land or people who view kinship with wildlife as a motive for CRP enrolment. This could speak to the complexity of how animals interact with both CRP land and agricultural systems. Kinship as a relational value was present in one local agricultural conservation website’s newsletter which showed a picture of a monarch butterfly and implored people to consider planting milkweed on their land in order to protect the species. Since monarch butterflies are minimally important as pollinators for agricultural systems (Bloom et al., Citation2021), this is a prime expression of kinship in the secondary data because the newsletter’s creators value CRP land due to its ability to mediate a relationship with local monarch butterflies.

Closely tied to the relational value of stewardship was responsibility. Often respondents articulated both values (approximately 55% of the time), which demonstrates the closeness of the two values. Typically, if a farmer or administrator believed they had a duty to look after the land, they felt accountable for what happens to it in the future. This seems logical, but the two values were able to be parsed out because responsibility was normally coded when new farmers, the future or the long-term sustainability of agricultural systems were mentioned, which can be tied to looking after the land as a steward but was not always articulated as such. A prime example of this is as follows: ‘I also look at it that, and I know dad does, and a lot of guys do, is we’re trying to preserve the ground for future generations … ’ (respondent 20). Responsibility was the most frequently cited relational value attributed to people beyond the respondent. This was seen as further validation on the importance of that particular relational value to the research area.

Finally, identity as a relational value was articulated and/or affirmed by 12 respondents. This value was only coded if the respondent spoke to how enrolment in the CRP was related to land management and a belief about who they are as a person, as opposed to if a person identified as a farmer or FSA administrator. For example, one respondent when discussing CRP enrolment and the possibility of forging a larger income by taking some of their land out of agricultural production asserted: ‘There’s some heritage that goes with this property. … And it’s more important to me to see the family heritage passed on to the next generation than it is to see how much money I can put in the bank’ (respondent 16). Identity was never articulated and/or affirmed without the presence of the value of stewardship, which illustrates the conceptual proximity these two values have to each other.

4.3. Financial incentive of the CRP

To many respondents, the instrumental value of the land (through financial security obtained by the land) was foremost in their dialogues. That said, rental rates from the federal government for land enrolled in the CRP can often be lower than projected agricultural production rates, so an examination of values beyond instrumental is warranted. CRP rental rates have not increased significantly in the United States since 1997 (Hellerstein, Citation2017), and many respondents cited the variability of rental rates as a programmatic challenge. Thus, if the USDA wishes to increase overall enrolment in the programme, while not markedly increasing financial incentives, research into other values informing enrolment is critical.

4.4. Limitations

This research confronted several challenges during data collection and analysis. First, the study was conducted during the continued global COVID-19 pandemic, and interviews were conducted via telephone in order to ensure respondent and researcher safety. A lack of in-person communication and data collection can be seen as a limitation on the results.

Additionally, while a number of consistent themes and relational values emerged during data collection and analysis throughout the four counties sampled, 22 respondents can only yield a certain amount of generalizable data. Secondary sources, such as local agricultural conservation websites from each county, helped to supplement the primary sources but were constrained in their explanatory power. Furthermore, when the four counties out of a possible 24 counties were randomly selected for sampling, neither of the two counties in the state of Idaho were selected.

While the interpretation of the collected data revealed five relational values within the analysis, other researchers may have interpreted the data differently. Relational values are fundamentally multidirectional (Ishihara, Citation2018), and an effort was made to present results that were not overly reductive. That said, some nuance and detail was invariably lost in the process of coding and analysis.

5. CONCLUSIONS

The relational values explored herein gesture at a complexity to governing natural resources which goes beyond purely instrumental frameworks of understanding and that federal soil conservation programme enrollers and enrolees both foster similar values. Research has shown that bureaucracies prioritize environmental rehabilitation at certain times (Sneddon et al., Citation2021), and the relational values alignment between private citizens and bureaucrats found in this research suggests regional offices of the FSA may currently be prioritizing conservation practices in order to rehabilitate the environment. Morales and Sariego-Kluge (Citation2021) have suggested that policy coordination at multiple institutional scales, combined with place specificity, can be key to green policies and sustainable development in sparsely populated regions. Such sparsely populated regions are often vital to conservation efforts. Further exploration into these dynamics would yield significant findings about how public–private partnerships characterize environmental issues and actualize conservation practices.

Previous scholarship laid the groundwork for empirical enquiries into relational values (Chapman et al., Citation2019) and detailed the benefit of listening to community members for insight into the values which drive conservation (Staddon et al., Citation2021). This paper has endeavoured to build upon that scholarship and to endorse the proposal by relational values scholars that ‘ethnographic work can inform policy-making through methodological commitments to describe accurately the types of relationships and interactions that people have with their physical environment’ (Norton & Sanbeg, Citation2021, p. 710). As such, empirical relational values methodologies, such as the one employed in this paper, appear to be significant tools for policymakers striving to create more resilient, inclusive and sustainable social–ecological systems.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The author thanks Allen Thompson, Carolyn Fonyo, Hilary Boudet, Holly Campbell and Robert Thompson for support and guidance with this project. Additionally, thanks are extended to Rhiannon Pugh and the anonymous reviewers whose insightful comments helped improve this manuscript; as well as the interviewees for their time and participation.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

REFERENCES

- Allen, K. E., Quinn, C. E., English, C., & Quinn, J. E. (2018). Relational values in agroecosystem governance. Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability, 35, 108–115. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cosust.2018.10.026

- Arias-Arévalo, P., Martín-López, B., & Gómez-Baggethun, E. (2017). Exploring intrinsic, instrumental, and relational values for sustainable management of social–ecological systems. Ecology and Society, 22(4). https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-09812-220443

- Beilin, R. (2005). Photo-elicitation and the agricultural landscape: ‘seeing’ and ‘telling’ about farming, community and place. Visual Studies, 20(1), 56–68. https://doi.org/10.1080/14725860500064904

- Bloom, E. H., Graham, K. K., Haan, N. L., Heck, A. R., Gut, L. J., Landis, D. A., Milbrath, M. O., Quinlan, G. M., Wilson, J. K., Zhang, Y., Szendrei, Z., & Isaacs, R. (2021). Responding to the US national pollinator plan: A case study in Michigan. Frontiers in Ecology and Environment, 20(2), 84–92. https://doi.org/10.1002/fee.2430

- Bremer, L. L., Brauman, K. A., Nelson, S., Prado, K. M., Wilburn, E., & Fiorini, A. C. O. (2018). Relational values in evaluations of upstream social outcomes of watershed payment for ecosystem services: A review. Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability, 35, 116–123. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cosust.2018.10.024

- Britto dos Santos, N., & Gould, R. K. (2018). Can relational values be developed and changed? Investigating relational values in the environmental education literature. Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability, 35, 124–131. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cosust.2018.10.019

- Chan, K. M. A., Balvanera, P., Benessaiah, K., Chapman, M., Díaz, S., Gómez-Baggethun, E., Gould, R., Hannahs, N., Jax, K., Klain, S., Luck, G. W., Martín-López, B., Muraca, B., Norton, B., Ott, K., Pascual, U., Satterfield, T., Tadaki, M., Taggart, J., & Turner, N. (2016). Why protect nature? Rethinking values and the environment. PNAS, 113(6), 1462–1465. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1525002113

- Chan, K. M. A., Gould, R. K., & Pascual, U. (2018). Editorial overview: Relational values: What are they, and what’s the fuss about? Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability, 35, A1–A7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cosust.2018.11.003

- Chapman, M., Satterfield, T., & Chan, K. M. A. (2019). When value conflicts are barriers: Can relational values help explain farmer participation in conservation incentive programs? Land Use Policy, 82, 464–475. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2018.11.017

- da Silva, J. M. C., Pinto, L. P., & Scarano, F. R. (2021). Toward integrating private conservation lands into national protected area systems: Lessons from a megadiversity country. Conservation Science and Practice, e433. https://doi.org/10.1111/csp2.433

- Deplazes-Zemp, A., & Chapman, M. (2021). The ABCs of relational values: Environmental values that include aspects of both intrinsic and instrumental valuing. Environmental Values, 30(6), 669–693. https://doi.org/10.3197/096327120X15973379803726

- Dreiss, L. M., & Malcom, J. W. (2022). Identifying key federal, state, and private lands strategies for achieving 30× 30 in the United States. Conservation Letters, 15(1), e12849. https://doi.org/10.1111/conl.12849

- Gómez-Baggethun, E., & Ruiz-Pérez, M. (2011). Economic valuation and the commodification of ecosystem services. Progress in Physical Geography, 35(5), 613–628. https://doi.org/10.1177/0309133311421708

- Hellerstein, D. M. (2017). The US conservation reserve program: The evolution of an enrollment mechanism. Land Use Policy, 63, 601–610. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2015.07.017

- Himes, A., & Muraca, B. (2018). Relational values: The key to pluralistic valuation of ecosystem services. Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability, 35, 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cosust.2018.09.005

- Ishihara, H. (2018). Relational values from a cultural valuation perspective: How can sociology contribute to the evaluation of ecosystem services? Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability, 35, 61–68. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cosust.2018.10.016

- Jain, A. (2022). Negotiating environmentality: Implementation of joint forest management in eastern India. Regional Studies, Regional Science, 9(1), 446–456. https://doi.org/10.10180/21681376.2022.2084446

- Johnson, R., Monke, J., Regmi, A., Rosa, I., Schnepf, R., Stubbs, M., Platzer, M. D., Yen, J. H., McMinimy, M. A., Angadjivand, S., Aussenberg, R. A., Clifford Billings, K., Bracmort, K., Casey, A. R., Cowan, T., Greene, J. L., & Hoover, K. (2019). The 2018 Farm Bill (PL 115-334): Summary and side-by-side comparison. Retrieved June 22, 2022, from https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/R/R45525/1

- Lehner, P. H., & Rosenberg, N. A. (2021). Policy pathways to carbon-neutral agriculture. In World scientific encyclopedia of climate change: Case studies of climate risk, action, and opportunity volume 2 (pp. 119–133). https://doi.org/10.1142/9789811213953_0012

- Longhurst, R. (2010). Semi-structured interviews and focus groups. In N. Clifford, S. French, & G. Valentine (Eds.), Key methods in geography (pp. 103–117). Sage.

- Morales, D., & Sariego-Kluge, L. (2021). Regional state innovation in peripheral regions: Enabling Lapland’s green policies. Regional Studies, Regional Science, 8(1), 54–64. https://doi.org/10.1080/21681376.2021.1882882

- Norton, B., & Sanbeg, D. (2021). Relational values: A unifying idea in environmental ethics and evaluation? Environmental Values, 30(6), 695–714. https://doi.org/10.3197/096327120X16033868459458

- Sneddon, C., Magilligan, F. J., & Fox, C. A. (2021). Peopling the environmental state: River restoration and state power. Annals of the American Association of Geographers, 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/24694452.2021.1913089

- Staddon, S., Byg, A., Chapman, M., Fish, R., Hague, A., & Horgan, K. (2021). The value of listening and listening for values in conservation. People and Nature, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1002/pan3.10232

- Stotten, R. (2018). Through the agrarian lens: An extended approach to reflexive photography with farmers. Visual Studies, 33(4), 374–394. https://doi.org/10.1080/1472586X.2019.1583079

- US Department of Agriculture (USDA). (2022). Conservation Reserve Statistics. Retrieved June 22, 2022, from https://www.fsa.usda.gov/programs-and-services/conservation-programs/reports-and-statistics/conservation-reserve-program-statistics/index