ABSTRACT

Path development and path creation are prevalent concepts in efforts to understand regional economic change and innovation. A recent focus has been on ‘green’ path development: industrial change associated with environmentally beneficial products and services. This provides a moment to take stock of the path development literature to date and ask: What or who is it for? In this article we use the concept of just transition to explore ways that (green) path development concepts could be more attuned to concerns for human and environmental well-being as opposed to economic growth and innovation as goals in themselves. Building from Geographical Political Economy approaches and injecting complementary cultural economic and sociological perspectives, we generate a conception of green and just path development. This conception builds a more variegated understanding of path development as a theory of change, focusing on negotiation, struggle, inclusion and exclusion in path development processes, and leaning to a stronger orientation towards outcomes for people and places, especially implications for work and communities. This matters for understanding what the purpose of investigating path development is, and what counts as ‘success’ in evaluating path development processes.

1. INTRODUCTION

A large body of literature in regional studies and economic geography is focused on industrial path development: how economies embed and change over time, reinforcing existing industrial trajectories or evolving into something different (Binz & Gong, Citation2022). Changing economic development trajectories also has potential implications for the distribution of economic outcomes. However, without intervention existing patterns of uneven development and exclusion will likely persist through economic restructuring, albeit potentially moving some contours of those patterns (While & Eadson, Citation2022). These implications have been largely overlooked in the path development literature (Mackinnon et al., Citation2019). In this article we argue that path development as currently conceptualized and operationalized does not easily lend itself to such questions, nor questions of justice more broadly.

This is especially important in the context of decarbonization, given the wide-ranging and urgent industrial change required. Although there has been emerging concern for ‘green’ path development (Trippl et al., Citation2020), evidence for environmental or socio-economic outcomes remains scarce (Gibbs & Jensen, Citation2022). And while those investigating path development have incorporated learning from different branches of transition theories (Gibbs & Jensen, Citation2022; Mackinnon et al., Citation2019), less attention has been paid to questions of justice (Coenen et al., Citation2021).

We argue that the concept of just transition can complement existing understanding of green path development. Just transition is concerned with ensuring decarbonization does not entrench new or deeper forms of inequality and injustice, and more optimistically to address existing inequalities (Newell & Mulvaney, Citation2013). The path development literature has provided important frameworks for understanding processes of industrial change that are useful for considering just transitions in terms of how and where industries will emerge, decline or transform. We argue that those working in the field of regional studies need to engage with these overlaps.

As such, in this article we begin a conversation between the path development and just transition literature to propose an original synthetic concept of green and just path development (GJPD). We think this is important because path development as a theory of change needs to better account for underpinning normative assumptions and logics behind understandings of such change, as well as the outcomes of these processes. Our conception involves: (1) an expanded gaze for path development analysis, considering a wider set of logics and actors within path development processes, paying particular attention to processes of negotiation, inclusion and exclusion; and (2) a reworked analytical framework for path development as theory of change, shifting analytical emphasis towards the politics of path development.

The remainder of the paper is structured as follows. We next briefly outline recent path development debates before homing in on ‘green’ path development literature. We then outline key facets of an expanded analytical gaze for GJPD, cueing up a revised framework for path development as theory of change.

2. PATH DEVELOPMENT: WHAT IS IT FOR?

Path developmentFootnote1 is a core concept in regional studies and economic geography. This includes growing focus on innovation and industrial change for sustainability transitions; sometimes called ‘green’ path development (e.g., Dawley et al., Citation2015; Jakobsen et al., Citation2021; Nilsen & Njøs, Citation2021).

Martin and Sunley (Citation2006) set out key terms and questions relating to literature to that date on regional path dependence, situated in evolutionary economic geography (EEG). This paper and other contemporaneous contributions, including by Boschma and Frenken (Citation2006) and Martin (Citation2010), ignited a boom in scholarship considering the question of ‘how new paths come into being’ (Martin & Sunley, Citation2006, p. 13, original emphasis). They set out a series of scenarios whereby regions can ‘escape lock-in’ (p. 419) and create new industrial paths, which remain central to contemporary debates on path development, as highlighted in a series of recent articles that have set out to provide a ‘comprehensive understanding’ of (Hassink et al., Citation2019), ‘rethink’ (Mackinnon et al., Citation2019) or ‘unravel’ (Trippl et al., Citation2020) regional path development. These articles have detailed the roots and trajectories of the path development literature. We do not propose to do so again here. Instead we note two trends within the recent path development literature: examining the role of different types of institution, and of agency, in determining path development.

First, a recurring critique of path development literature as rooted in EEG is lack of concern for how institutions shape path development processes and outcomes. In the words of Trippl and Tödtling (Citation2018, p. 1779), this reinforces ‘a neoliberal policy approach that restricts the role of public interventions to setting up a suitable regulatory frame and supporting an entrepreneurial climate’. Various attempts have been made to complement EEG approaches with insights from alternative sociological, political science and geographical traditions. Boschma and Capone (Citation2015) employ a Varieties of Capitalism framework in combination with EEG approaches to emphasize the role of national institutions in shaping path development (in their case through a focus on industrial diversification). The Varieties of Capitalism framework reminds us not only of the importance of state actions but also of markets as institutions. Hassink et al. (Citation2019) take this further to note the importance of multi-scalar analysis of institutional influences, including policy institutions and the state, as well as anchor institutions such as universities and research institutes. Mackinnon et al. (Citation2019) offer a compelling contribution to this theme through advocating a Geographical Political Economy (GPE) approach to path development, which situates such processes within ‘wider dynamics of capital accumulation’ (p. 120), incorporating a wide range of institutions including financial institutions, labour regimes, market construction, infrastructural organization and state regulation. Informal institutions (such as informal networks between individuals and firms as well as sets of attitudes and beliefs) are also important (Chlebna & Simmie, Citation2018).

Second, there has been growth in concern for how (and by who) agency is exercised in path development, particularly different types of actors beyond individual firms (Grillitsch & Sotarauta, Citation2020). This has centred on entrepreneurship within firms: entrepreneurs identifying and seizing opportunities for new competitive advantage through adaptation or creation of new paths. However, a broadening focus on different types of actor and institutions has fostered interest in changing institutional rules and norms (institutional entrepreneurship) and building place-based capacities for leadership (place leadership) to mobilize and connect different actors (Grillitsch & Sotarauta, Citation2020). Others have worked to conceptualize different forms of agency (e.g., Bækkelund, Citation2021; Trippl et al., Citation2020). Without denying the value of these conceptualizations, here we are less concerned with forms of agency than who or what possesses agency in path development processes (see below).

2.1. Enduring blind spots in path development

Despite recent advances to produce more situated and complex theories of change, there remains a lack of serious attention to the following question: What or who is regional path development for? A simple answer might be that regional path development analyses seek to explain relative regional economic change and potentially offer solutions for how places and regions might develop new economic trajectories. This response sets up a different question: What is economic development for?

Implicit within the path development literature is that innovation and regional economic growth is important for well-being of places but specific outcomes for people and places are rarely interrogated (although see Breul et al., Citation2021). Gibbs and Jensen (Citation2022) point out that this extends to lack of consideration for environmental benefits or otherwise of new ‘green’ industrial pathways. These questions are particularly important for mission-oriented change such as green economic restructuring. GPE perspectives (Mackinnon et al., Citation2019) have helped foreground questions of uneven development, as have those interested in ‘dark phases’ or fragility of regional path development (Blažek et al., Citation2020; Chlebna & Mattes, Citation2020; Jolly & Hansen, Citation2021). Mackinnon et al. (Citation2019) draw attention to recent work that has emphasized value capture and labour relations in the spatial organization of production networks: ‘New paths may generate new forms of inequality and exploitation through, for instance, the growth of low-value and precarious employment, uneven resource allocation, and the exclusion and displacement of some groups’ (Mackinnon et al., Citation2019, p. 121). They also highlight how shifting production geographies or decline of industries in particular places will not always be fully compensated by creation of new paths, potentially reinforcing spatial inequalities over successive rounds of restructuring. We can reach beyond recent preoccupation with path development to foundational work by Massey (Citation1984) on the spatial divisions of labour to further understand how interaction between changing global production networks and regions can ‘layer up’ to embed inequalities. Such work directs focus to what matters beneath the sometimes-abstract concern for changing industrial paths: the well-being of people, in places and enhancement of non-human well-being as an end in itself as well as being the foundation of human well-being.

Further, despite increasing attention to different forms of institutions and agency, many actors remain excluded from path development analyses. This might be because those actors are also excluded from the path development processes being studied. But it is important to understand and uncover who is being denied agency (and how) as well as to investigate who can effect change. Rainnie (Citation2021, p. 43) argues that ‘the concept of agency at a local level is at best undercooked’, also highlighting an ‘inclusionary bias’ in analyses which focus on participation in networks rather than non-participation or processes of ‘linking and de-linking’ (citing Bair & Werner, Citation2011). Lack of detailed consideration of ‘who is path development for’ and the role of agency beyond those included in path development processes also highlights need to better account for politics and power relations, which remain muted in the literature.

Finally, work on path development has mostly focused on new technological advancements and related industries at the expense of other forms of economic development (see section 3.2). Therefore, this provides a relatively narrow basis for understanding what forms path development might take and – by extension – the outcomes associated with those change processes.

3. GREEN AND JUST PATH DEVELOPMENT

Green economic restructuring is producing new economic geographies with implications for regional path development (While & Eadson, Citation2022). Decarbonization as a driver of economic restructuring has prompted a growing branch of ‘green’ path development literature either explicitly using that term (Gibbs & Jensen, Citation2022; Sotarauta et al., Citation2021; Trippl et al., Citation2020) or through a focus on regional path development in ‘green’ industries (e.g., Chlebna & Simmie, Citation2018; Cooke, Citation2012; Dawley, Citation2014; Zhao et al., Citation2021).

Interacting with literature on sustainability transitions (Köhler et al., Citation2019; Markard et al., Citation2012), green path development literature has brought new insights for understanding how transition to an environmentally sustainable economy might be achieved, as well as to path development literature. Sustainability transitions literature has been identified as particularly helpful for identifying legitimation processes in achieving change (Gibbs & Jensen, Citation2022; Mackinnon et al., Citation2022); and literature on the agency of incumbent actors to support or stymie transitions (Mori, Citation2021) further elaborates agency in the ‘dark side’ of path development. Green path development is directly related to multilevel policy change, and so is a particularly good case for highlighting how regulatory and market construction regimes shape path development. Path development theories are especially helpful for understanding how green restructuring processes take place in different regions, and for highlighting potential causes of geographical differentiation, especially if situated within wider concern for GPE of uneven development.

In addition to sustainability transitions literature, we believe a different set of literature focusing on green economic restructuring can make an important contribution to path development scholarship, helping to overcome some key blind spots outlined above and take forward debates about inequalities, exclusion and politics in path development processes: that which focuses on the concept of ‘just transition’. Although sustainability transitions and just transition literatures share use of the term ‘transition’, they tend to begin from different standpoints. Broadly, just transition literature is more rooted in political geography and sociology as opposed to sustainability transitions’ leaning towards evolutionary economics and innovation studies.

3.1. Just transition and green path development

Just transition is a concept with its own lengthy history. It was initially rooted within political struggles for labour rights in industrial change as labour movements in the United States during the 1980s sought to ensure protection for workers whose jobs were put at risk by new environmental legislation. The trade union movement has continued to be an important force for just transition, more recently centring on mitigating negative implications of decarbonization for workers in fossil fuel and high-emitting industries (International Labour Organisation (ILO), Citation2015). This has been accompanied by academic literature concerned with conceptualizing just transition as a labour-oriented challenge (Clarke & Lipsig-Mummé, Citation2020; Stevis & Felli, Citation2020), also inspiring work on place-based implications of decarbonization (Duffy & Whyte, Citation2017). A second branch of literature considering just transition as relating to different forms of justice in decarbonization processes has helped to foreground questions of participation, inclusion and exclusion (Wang & Lo, Citation2021). These overlapping branches provide useful insights for analysis of green path development. From an economic geography perspective, the focus of earlier literature on labour processes and outcomes and broader questions about uneven development is particularly important, while literature on just transition as a question of justice more broadly conceived provides useful frameworks for considering ‘whose agency’ in path development. Both perspectives on just transition are helpful for expanding understanding of place within a GJPD framework, as we elaborate below.

To date the just transition literature has been less strong on investigating mechanisms of change, in particular decision-making by firms and investors: for instance, ‘the role and responsibility of private sector actors … is surprisingly absent from much of the current debate about JT [just transition]’ (Snell, Citation2018, p. 554). Similarly this literature has also tended not to engage in a deeper understanding of how the state operates as a range of institutions and actors engaged in shaping place-based processes and outcomes. There is much then that path development analyses can bring to understanding processes for just transitions.

Bringing together path development theorizations with the just transition literature and related concepts with a more avowedly political approach to decarbonization processes can help to understand how different routes to path development might achieve different forms of transition which might be more or less ‘just’ in terms of processes and outcomes. We highlight four ways a just transition sensibility can support analysis of green path development more attuned to questions of what path development is for, who matters within path development processes, and related questions of power and control. We argue for an expanded view of:

Economic development.

Labour (also highlighting expanded view of agency).

Place.

Political struggle.

Through this expanded gaze we seek to create potential for different ways of understanding process and outcomes for path development. This informs how we consider GJPD as a theory of change (see section 4).

3.2. An expanded view of economic development

GJPD requires an expanded view of economic development. Development of new industrial paths is not just about whether x or y industry becomes embedded within a place but also about how economic change interacts with places as more-than-economic entities and people within those places. Some of this concerns how investment is attracted or endogenous growth is fostered, but concern for these changes is a narrow view of path development. GJPD research needs to consider how potential and existing economic futures unfold for different (interconnected) places and what that means for well-being of those places (and the people who live in them). We consider three conceptual and empirical expansions required to achieve this: from production orientation towards systems of provision; considering different potential economic development trajectories; and towards a more diverse conceptualization of economic activity.

First, GJPD requires moving beyond the production-oriented focus found in much existing literature to a concern for systems of provision, considering different aspects of production, distribution and consumption cycles. This is important for considering green futures where, for instance, circular economy principles and overall reduction in resource use might be essential to success.

Second, GJPD needs to consider potential for different forms of economic futures, beyond a focus on ‘high value’ industries. Deep decarbonization might not be possible within the current focus on economic growth as a Key Performance Indicator for economic success, yet path development literature has tended not to consider this possibility:

While mainstream economic geography is doing increasing research on green manufacturing and services, with a few notable exceptions, its predominant conceptual approaches to emerging modes of economic orientation continue to examine economic transitions somewhat unreflexively within the context of traditional growth paradigms. (Schulz & Bailey, Citation2014, p. 277)

GJPD could usefully investigate what regional path development might look like from a degrowth perspective, and how this might support socially and environmentally positive outcomes. Changing development logics means thinking about how alternative economic activities might become embedded in places and regions. GJPD therefore requires moving beyond the analysis of high-growth ‘frontier’ sectors to a clearer focus on supporting sectors and business models that support alternative economic models, such as well-being economies, or focus on reforming the foundational economy to support human and ecological well-being. Again, this implies a ‘refocus from growth per se to purpose-driven economic strategies that prioritize public services and redistribute incomes’ (Wahlund & Hansen, Citation2022, p. 171). This kind of expanded gaze requires consideration of shifts across and relations between more than one industry, or ‘interpath dynamics’ (Fraggenheim et al., Citation2020). This is particularly pertinent when considering how regional path development might be trained towards circular economic models essential to sustainability transitions. Here development of industrial symbiosis becomes critical, requiring coordinated strategies of path development across different industries (Henrysson & Nuur, Citation2021).

Third, thinking beyond frontier sectors requires a further expansion if we want to consider path development as if it matters. This means supplementing a political economic gaze (as set out by Mackinnon et al., Citation2019) with contributions from cultural economy to explore what counts as economy in the first place. An expanded view of economic development would account for a more diverse economic perspective (e.g., Gibson-Graham, Citation2006). This is partly needed to better understand ‘classic’ path development through high-tech, high-growth industry. For example, such growth increasingly implies a growing reliance on automated processes, which has implications for where economic gains are realized. For instance, automation creates uncertainty about how wealth creation is transferred to workers if the need for labour is reduced, which in turn changes how we think about possibilities for locales to benefit from path development processes. Considering path development as a process helps to expand our way of thinking about potential economic paths which do not foreground the formal, waged economy as the primary source of well-being to people in communities.

An expanded view of ‘the economy’ in path development also means expanding views of interpath dynamics: for instance, in some scenarios new industrial activities might displace informal subsistence activities (Bainton et al., Citation2021). Considering the economy in this way is important to understanding path development because it helps us situate our understanding of human ‘assets’ within systems of relation that produce conditions in particular places and different industries. It also enjoins us to think more broadly about the outcomes of path development processes, for instance: How does industrial change impact on, for example, the gendered division of labour or other forms of intersectional inequalities? How do new industrial developments impact on other pathways built on informal or subsistence economies?

3.3. An expanded view of labour

As noted in section 2, a concern for our reassessment of path development literature is to emphasize different potential sources of agency within path development processes. These sources include a range of actors often not considered within the path development literature, such as civil society activists, community groups and individual citizens. We draw particular attention to the potential agency of workers.

Labour processes in the path development literature have largely been framed as a question of resource or ‘assets’: workers who can be harnessed to achieve path development goals through either utilization of existing skills and knowledge or retraining to provide the required skills (at the right price). Workers as assets which can support path development is one important way of understanding industrial change. However, this viewpoint denudes labour of agency. We argue for an expanded view of labour through a more detailed focus on how waged labour shapes and is shaped by path development processes.

First, labour-perspective just transition literature reminds of workers’ roles as agents in shaping path development through organized collective action, most commonly through trade unions. The history of industrial change shows how path development shapes and is shaped by labour agency. For instance, the birth of manufacturing also created physical spaces for labour to organize on the shop floor and demand changes to working conditions, in turn prompting change in industrial processes. Elsewhere, Mitchell (Citation2009) discusses how a shift from coal- to oil-based energy systems allowed for different ways of spatially organizing production processes to initially limit opportunities for collective worker action. Massey (Citation1984) also extensively researched similar processes of labour control through her spatial divisions of labour approach to economic geographies.

Further, the ‘unpredictability’ of human labour (especially its ability to exercise agency) is linked to mechanization and automation of economic processes, driving innovation and industrial change (Lin, Citation2022). Following this theme, growing literature on labour and decarbonization highlights that green path development processes do not imply improved working conditions (Pearse & Bryant, Citation2021; While & Eadson, Citation2022). Indeed, if we assume green path development continues within prevailing economic restructuring logics, investment in new green plant, products and businesses potentially creates a point for reducing worker agency through automation of processes, and continued casualization and flexibilization of what work remains (Lin, Citation2022).

Just transition literature has also shone a light on labour’s collective agency through trade unions to accelerate and hinder green path development processes. As well as supporting better working conditions for workers in green industries, research has found that primary concern for workers’ welfare can lead to opposition to green industrial change. Normann and Tellmann report on Norwegian petroleum unions proposing to ‘work actively to maintain and further develop the oil and gas industry’ (LO Union, 2017, p. 257, cited in Normann & Tellmann, Citation2021). However, such trends are not universal. Stevis (Citation2018) notes the spatially uneven nature of unions’ approaches to green industrial change, which in the United States often relate to interplay of political contexts at local, regional, state and national levels.

In summary, labour matters to understanding path development because worker agency can make a difference to processes and outcomes of industrial change. Understanding outcomes for workers is also essential if we understand the purpose of economies (and, by extension, study of path development) to support livelihoods and well-being. In that sense new path development should support increased access to ‘good quality’ work (however that might be defined). Greater focus on labour processes also matters because it highlights that path development is not a politically neutral process. Indeed, industrial change is marked by political struggle, often between labour and ‘capital’ (see section 3.5). We also need to link understanding of diverse economic pathways with relations between diverse forms of work which go beyond waged labour (as outlined in section 3.2).

3.4. An expanded view of place

Path development literature emphasizes the importance of place to economic development. Just transition literature could benefit from greater engagement with path development concepts. These concepts provide a basis for understanding how economic processes happen within places, and increasingly incorporate how these place-based processes are situated within global production networks and innovation systems: discussion that is often missing from place-based just transition literature which tends to focus more on local experience of change (Stevis & Felli, Citation2020). Emerging work on green path development also identifies the need to consider effects of industrial change beyond those places, for instance, other sites along systems of provision or spatial displacement effects of closing high emissions industries in a place (Chlebna et al., Citation2022). Understanding these spatial implications as well as firm decision-making and processes of mobilizing institutions and assets for industrial change in just transition literature would be particularly enhanced by reference to contributions from path development literature.

That said, there are calls for more theoretical engagement with ideas of place, as well as scale and space within studies of green industrial change (Binz et al., Citation2020), and recent literature on just transition taking a ‘sociology of place’ perspective can provide insights in support of this aim. This literature has focused on how path dependent economic processes and activities become internalized as local economic identities, which in turn play a role in reconfiguring places and communities resulting from decarbonization processes. It emphasizes how change is anticipated, experienced and lived with ‘on the ground’ (Ceresola & Crowe, Citation2015; Evans & Phelan, Citation2016; Olson-Hazboun, Citation2018). Such literature also usefully complements existing concern for materiality in path development (Steen & Njøs, Citation2019) to highlight the symbolic role of material infrastructures, buildings, etc. in producing path dependent identities: for example, the dismantled winding gear of a coal mine as often displayed at the boundary to former mining towns in northern England as a reminder of place identity and heritage.

This literature also shows complex ways people make sense of change and what that might mean for public acceptance of new path trajectories. For example, Mayer (Citation2018) found that communities historically dependent upon fossil fuel extraction are no more likely to support packages for workers facing difficulties than other communities. This helps better understand potential points of resistance or support in mobilizing different publics for industrial change. Socio-cultural factors shape path development processes: social identities can be impacted by industrial change, and these identities can also mediate other change processes.

Such an approach also points to difference within communities, and the importance of recognizing legitimate difference, which is sometimes picked up in justice-perspective just transition literature as recognition justice:

acknowledgement of divergent identities, cultural histories, and power dynamics, and how these may interact with proposed changes. … Space is particularly important to recognition justice in terms of recognising specific place identities and how these may shape the acceptability of transition measures. (Garvey et al., Citation2022, p. 2)

3.5. GJPD as a process of political struggle

The final point of our expanded gaze emphasizes path development as a process of political negotiation and struggle. This understanding is central to labour-perspective just transition literature (Snell, Citation2018). To understand path development processes and outcomes, it is necessary to study these negotiations.

It is potentially useful to consider GJPD as embroiled within a broader interplay of market embedding and disembedding as detailed by Polanyi (Citation1944). Regional path development is partly about the possibility of harnessing economic flows to benefit a particular place, itself a form of spatially embedding markets. Pragmatically GJPD involves continuing negotiation between market and civic goals, which draws attention to different actors within processes of path development. Here we need to pay attention to how different state, community, civil society and trade union actors can engage with path development processes to socially embed economic activities within places as forces for positive change for those places: for instance, the creation of good or better working conditions and pay; better local environments; financial flows into local infrastructure and amenities; etc.

Seeing path development as a political process also shifts our analytical gaze towards investigating how different ties are or are not formed between actors and the forms of power enacted in doing so. This means focusing on how different groups of people and organizations are brought together to what ends (Breul et al., Citation2021). But it also means more thoroughly interrogating what binds these groups together in pursuit of path development goals, and what decision-making mechanisms and fora operate to negotiate actions towards those goals. How those decision-making fora are convened, who is involved, what specific mechanisms and devices are employed to hear different voices and make decisions is critically important to understanding how decisions are made (Marres & Lezaun, Citation2011). This is not just about who is included in processes, but also how they are involved: What agency do different voices have within decision-making? This is a question of procedural justice as highlighted in justice-perspective just transition literature (McCauley & Heffron, Citation2018).

It matters normatively to understand how dominant or hegemonic views are (re)produced, but it also matters for understanding path dependency and change in path development, including unpicking how logics and principles of development are (re)produced through such processes. This helps to foreground questions of power, negotiation and conflict. Such analyses require understanding of relative levels of resources among different actors, and interrogation of decision-making processes or methods of participation. They also need to recognize conflict and unresolved dilemmas as necessary, unavoidable aspects of participation, which are as important to path development processes as consensus-building (Eadson & van Veelen, Citation2021). There are also pragmatic reasons for considering how different publics are enrolled, mobilized or excluded from path development processes. Citizens’ acceptance of new industrial pathways can hinder or accelerate change processes, and the form of participation makes a difference to public acceptance (Espert et al., Citation2016; Nurdiawati & Urban, Citation2022; Öhman et al., Citation2022).

4. IMPLICATIONS FOR GJPD AS THEORY OF CHANGE

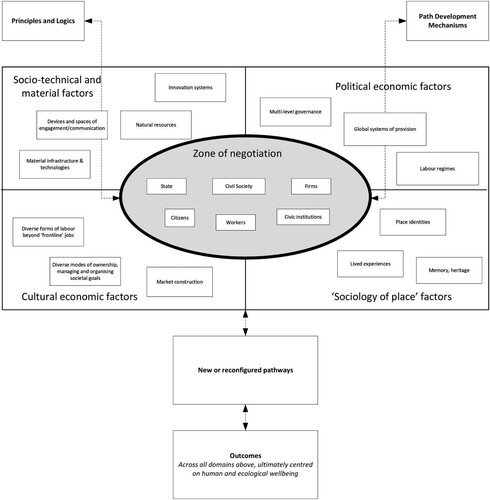

A corollary of expanding our path development gaze is a reconsideration of how we conceptualize path development as a theory of change. We build from our discussion above to set out four implications for path development as theory of change, which is summarized in .

Figure 1. Green and just path development (GJPD) as theory of change.

First, consideration for different potential economic models for path development (see section 3.1) and for path development as a process of political struggle (see section 3.5) implies a need for greater interrogation of logics of path development. As Pike et al. (Citation2007, p. 1260) argue:

Individuals and institutions with social power and influence can seek to impose their specific interests and visions of local and regional development but these may be contested. … It is, then, critical to ask whose principles and values are being pursued in local and regional development.

Second, our expanded gaze implies need to expand thinking about process and agency in path development as set out above. This includes acknowledging a greater range of actors in path development processes, unequal capabilities to exercise agency, and processes of negotiation between different sets of actors. spotlights a zone of negotiation between different actors, where focus on processes of assembling coalitions, and especially the dynamics of inclusion, exclusion and maintenance of those coalitions is critical. The diagram contains illustrative examples of key actors in those negotiations. It emphasizes workers and citizens as important actors in path development (even where this importance is defined by absence from formal decision-making mechanisms). Our conception especially requires attending to decision-making processes and development and maintenance of different kinds of ties between actors, focusing on who is included (and excluded) by what means.

The zone of negotiation is shaped through consideration of key analytical factors outlined in our preceding discussion (see section 3): socio-technical and material, political economic, cultural economic and sociology-of-place interpretations of change factors (acknowledging overlap and connections between these approaches). Socio-technical and material factors is partly covered in existing literature on the overlaps between green transitions and path development – for instance the role of innovation systems, and material resources – as well as questions about specific devices and spaces of engagement and communication which are critical to the process of negotiation, especially question framing and inclusion/exclusion of actors (Marres & Lezaun, Citation2011). Drawing from Mackinnon et al. (Citation2019), political economic factors focus on how negotiations are shaped by multilevel governance arrangements, systems of provision (and associated value chains), and governance arrangements for other sets of actors beyond firms, which includes labour regimes. Sociology of place factors encourage thinking how (for example) identity, lived experiences, memory and heritage shape negotiations and outcomes for industrial change (see section 3.4). Finally, cultural economic factors prompt consideration of diverse economic models and activities (see section 3.2), as well as how markets are constructed through negotiation (Eadson & Foden, Citation2019) as part of path development processes. highlights how principles and logics of path development feed into and are constructed by these negotiations, as are different path development mechanisms identified in mainstream path development literature which act as different drivers of change, like diversification, transplantation, upgrading or indigenous innovation (Mackinnon et al., Citation2019).

Third, our discussion above argued to extend analysis of outcomes from first order outcomes about the extent industries embed and grow or decline in places, to examining critical factors of human and ecological well-being: livelihoods, participation in economic decision-making, recognition of differential rights and needs, and environmental impacts. This also means making interrelations between different forms of outcome a focus of study: for instance, relations between different forms of work, and between economic processes and place-making.

Finally, bringing this together, we need to interrogate how different kinds of logics and processes lead to different outcomes for who and where. This requires paying particular attention to spatial context and the variety of forms that path development takes in different settings. From here we can build new, more variegated, typologies of path development that can account for the variety of logics, processes and outcomes we need to investigate in order to further our understanding of path development. There is a challenge for empirical studies to engage with GJPD to produce such typologies.

5. CONCLUSIONS

This article has set out how path development literature could usefully engage with just transition concepts to enhance its power as a theory of change, in doing so developing a novel conception of GJPD. This has implications for scholars of industrial change in different contexts across regional studies and economic geography, as well as for those who approach similar challenges from the perspective of just transition, often situated within political geography or sociology.

When thinking about green path development, engaging with just transition reminds us to consider path development as a more or less socially and spatially just process, with more or less socially and spatially just outcomes. These are important because economic change must be evaluated through its contribution to human and ecological well-being. Lessons from path development scholarship to date are critical to unpicking these processes to understand mobilization and modification of different types of assets, forms of entrepreneurship, and mechanisms of path creation. It will also require development of more variegated typologies of path development to capture, for example, different models of participation and decision-making and the different types of outcomes that result. For instance, do different asset ownership structures, financial models or social dialogue processes lead to different modes of path development? How does interaction with different types of global systems of provision and associated divisions of labour impact on the benefits people-in-places receive from new path developments? These more nuanced models are best developed through bringing together theoretical insights with empirical research: a challenge for future research.

Further, arguably, a guiding concern of path development literature has been to understand how industries emerge and evolve in some places and not in others rather than assess the logics or outcomes for those processes beyond the location, growth and decline of different industries. However the choice of analytical gaze and focus of such analysis on some aspects of change rather than others is a normative decision. Arguing for a shift in that gaze to consider different ways of looking at the path development ‘problem’ should not be seen as an attempt to impose a normative framework on an ‘agnostic’ set of concepts: it is rather to expand thinking to better account for change processes by situating them more fully within different social actions and concerns. Changing our success parameters might also change how we seek out ‘successful’ path development cases. It will certainly require a more diverse empirical focus: it will remain important to critically analyse path development through ‘high value’ innovation, and therefore to consider emergent industries, but equally it will mean looking at how places foster well-being through other path development routes.

In summary, a move towards a conception of GJPD is about acknowledging the potential need to attend to different economic development logics to achieve economic development that fosters human and ecological well-being. It is not enough to consider processes of economic change on their own merits: the logics, processes and outcomes all require a more critical lens utilizing a wider range of analytical tools. Fundamentally this is about producing a politics of path development.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors thank the two anonymous reviewers who provided new insights and constructive critique that improved the argument and flow of the article. Thanks also to Richard Crisp and Peter Wells for feedback on draft iterations of the article, as well as participants in the City and Regional Sustainability Transitions session at the Regional Studies Association Winter Conference 2022, who provided feedback on a presentation based on a draft of the article.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 ‘Path creation’ is often used in preference to path development. We align ourselves with Hassink et al. (Citation2019, p. 1636 ) who note that, ‘arguably it is mainly differences in the adoption of terms that divide the field’ rather than substantive differences in approach or focus. We have chosen to use the term ‘path development’ throughout this article for consistency.

REFERENCES

- Bainton, N., Kemp, D., Lèbre, E., Owen, J. R., & Marston, G. (2021). The energy–extractives nexus and the just transition. Sustainable Development, 29(4), 624–634. https://doi.org/10.1002/sd.2163

- Bair, J., & Werner, M. (2011). The place of disarticulations: Global commodity production in La laguna. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 43(5), 998–1015. https://doi.org/10.1068/a43404

- Binz, C., Coenen, L., Murphy, J. T., & Truffer, B. (2020). Geographies of transition – From topical concerns to theoretical engagement: A comment on the transitions research agenda. Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions, 34, 1–3. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eist.2019.11.002

- Binz, C., & Gong, H. (2022). Legitimation dynamics in industrial path development: New-to-the-world versus new-to-the-region industries. Regional Studies, 56(4), 605–618. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2020.1861238

- Bækkelund, N. G. (2021). Change agency and reproductive agency in the course of industrial path evolution. Regional Studies, 55(4), 757–768. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2021.1893291

- Blažek, J., Květoň, V., Baumgartinger-Seiringer, S., & Trippl, M. (2020). The dark side of regional industrial path development: Towards a typology of trajectories of decline. European Planning Studies, 28(8), 1455–1473. https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2019.1685466

- Boschma, R. A., & Capone, G. (2015). Institutions and diversification: Related versus unrelated diversification in a varieties of capitalism framework. Research Policy, 44(10), 1902–1914. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2015.06.013

- Boschma, R. A., & Frenken, K. (2006). Why is economic geography not an evolutionary science? Towards an evolutionary economic geography. Journal of Economic Geography, 6(3), 273–302. https://doi.org/10.1093/jeg/lbi022

- Breul, M., Hulke, C., & Kalvelage, L. (2021). Path formation and reformation: Studying the variegated consequences of path creation for regional development. Economic Geography, 97(3), 213–234. https://doi.org/10.1080/00130095.2021.1922277

- Ceresola, R. G., & Crowe, J. (2015). Community leaders’ perspectives on shale development in the new Albany shale. Journal of Rural Social Sciences, 30(1). https://egrove.olemiss.edu/jrss/vol30/iss1/5

- Chlebna, C., Martin, H., & Mattes, J. (2022). Grasping transformative regional development – Exploring intersections between industrial paths and sustainability transitions. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 0308518X2211373. https://doi.org/10.1177/0308518X221137346

- Chlebna, C., & Mattes, J. (2020). The fragility of regional energy transitions. Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions, 37, 66–78. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eist.2020.07.009

- Chlebna, C., & Simmie, J. (2018). New technological path creation and the role of institutions in different geo-political spaces. European Planning Studies, 26(5), 969–987. https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2018.1441380

- Clarke, L., & Lipsig-Mummé, C. (2020). Future conditional: From just transition to radical transformation? European Journal of Industrial Relations, 26(4), 351–366. https://doi.org/10.1177/0959680120951684

- Coenen, L., Hansen, T., Glasmeier, A., & Hassink, R. (2021). Regional foundations of energy transitions. Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society, 14(2), 219–233. https://doi.org/10.1093/cjres/rsab010

- Cooke, P. (2012). Transversality and transition: Green innovation and new regional path creation. European Planning Studies, 20(5), 817–834. https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2012.667927

- Dawley, S. (2014). Creating new paths? Offshore wind, policy activism, and peripheral region development. Economic Geography, 90(1), 91–112. https://doi.org/10.1111/ecge.12028

- Dawley, S., Mackinnon, D., Cumbers, A., & Pike, A. (2015). Policy activism and regional path creation: The promotion of offshore wind in North East England and Scotland. Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society, 8(2), 257–272. https://doi.org/10.1093/cjres/rsu036

- Duffy, M., & Whyte, S. (2017). The Latrobe valley: The politics of loss and hope in a region of transition. Australasian Journal of Regional Studies, 23(3), 421–446.

- Eadson, W., & Foden, M. (2019). State, community and the negotiated construction of energy markets: Community energy policy in England. Geoforum; Journal of Physical, Human, and Regional Geosciences, 100, 21–31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2019.02.006

- Eadson, W., & van Veelen, B. (2021). Assemblage-democracy: Reconceptualising democracy through material resource governance. Political Geography, 88, 102403. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polgeo.2021.102403

- Espert, V., Arnold, K., Vallentin, D., Lechtenböhmer, S., & Schneider, C. (2016). Platform climate protection and industry North-Rhine Westphalia – A multi stakeholder process for the advancement of energy efficiency and low carbon technologies in energy intensive industries. Eceee Industrial Summer Study Proceedings.

- Evans, G., & Phelan, L. (2016). Transitions to a post-carbon society: Linking environmental justice and just transition discourses. Energy Policy, 99, 329–339.

- Fraggenheim, A., Trippl, M., & Chlebna, C. (2020). Beyond the single path view: Interpath dynamics in regional contexts. Economic Geography, 96(1), 31–51. https://doi.org/10.1080/00130095.2019.1685378

- Garvey, A., Norman, J. B., Büchs, M., & Barrett, J. (2022). A “spatially just” transition? A critical review of regional equity in decarbonisation pathways. Energy Research & Social Science, 88, 102630. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.erss.2022.102630

- Gibbs, D., & Jensen, P. D. (2022). Chasing after the wind? Green economy strategies, path creation and transitions in the offshore wind industry. Regional Studies, 56(10), 1671–1682. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2021.2000958

- Gibson-Graham, J. K. (2006). A postcapitalist politics. University of Minnesota Press.

- Grillitsch, M., & Sotarauta, M. (2020). Trinity of change agency, regional development paths and opportunity spaces. Progress in Human Geography, 44(4), 704–723. https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132519853870

- Hassink, R., Isaksen, A., & Trippl, M. (2019). Towards comprehensive understanding of new regional industrial path development. Regional Studies, 53(11), 1636–1645. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2019.1566704

- Henrysson, M., & Nuur, C. (2021). The role of institutions in creating circular economy pathways for regional development. The Journal of Environment & Development, 30(2), 149–171. https://doi.org/10.1177/1070496521991876

- International Labour Organisation (ILO). (2015). Guidelines for a just transition towards environmentally sustainable economies and societies for all. ILO. https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/@ed_emp/@emp_ent/documents/publication/wcms_432859.pdf.

- Jakobsen, S., Uyarra, E., Njøs, R., & Fløysand, A. (2021). Policy action for green restructuring in specialized industrial regions. European Urban and Regional Studies, 29, 312–331. https://doi.org/10.1177/09697764211049116

- Jolly, S., & Hansen, T. (2021). Industry legitimacy: Bright and dark phases in regional industry path development. Regional Studies, 56(4), 630–643. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2020.1861236

- Köhler, J., Geels, F. W., Kern, F., Markard, J., Onsongo, E., Wieczorek, A., & Wells, P. (2019). An agenda for sustainability transitions research: State of the art and future directions. Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions, 31, 1–32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eist.2019.01.004

- Lin, W. (2022). Automated infrastructure: COVID-19 and the shifting geographies of supply chain capitalism. Progress in Human Geography, 46(2), 463–483. https://doi.org/10.1177/03091325211038718

- Mackinnon, D., Dawley, S., Pike, A., & Cumbers, A. (2019). Rethinking path creation: A geographical political economy approach. Economic Geography, 95(2), 113–135. https://doi.org/10.1080/00130095.2018.1498294

- Mackinnon, D., Karlsen, A., Dawley, S., Steen, M., Afewerki, S., & Kenzhegaliyeva, A. (2022). Legitimation, institutions and regional path creation: A cross-national study of offshore wind. Regional Studies, 56(4), 644–655. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2020.1861239

- Markard, J., Raven, R., & Truffer, B. (2012). Sustainability transitions: An emerging field of research and its prospects. Research Policy, 41(6), 955–967. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2012.02.013

- Marres, N., & Lezaun, J. (2011). Materials and devices of the public. Economy and Society, 40(4), 489–509. https://doi.org/10.1080/03085147.2011.602293

- Martin, R. (2010). Rethinking regional path dependence: Beyond lock-in to evolution. Economic Geography, 86(1), 1–27. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1944-8287.2009.01056.x

- Martin, R., & Sunley, P. (2006). Path dependence and regional economic evolution. Journal of Economic Geography, 6(4), 395–437. https://doi.org/10.1093/jeg/lbl012

- Massey, D. (1984). Spatial divisions of labour: Social structures and the geography of production. Macmillan.

- Mayer, A. (2018). A just transition for coal miners? Community identity and support from local policy actors. Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions, 28, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eist.2018.03.006

- McCauley, D., & Heffron, R. (2018). Just transition: Integrating climate, energy and environmental justice. Energy Policy, 119, 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2018.04.014

- Mitchell, T. (2009). Carbon democracy. Economy and Society, 38(3), 399–432. https://doi.org/10.1080/03085140903020598

- Mori, A. (2021). How do incumbent companies’ heterogeneous responses affect sustainability transitions? Insights from China’s major incumbent power generators. Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions, 39, 55–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eist.2021.02.003

- Newell, P., & Mulvaney, D. (2013). The political economy of the ‘just transition’. The Geographical Journal, 179(2), 132–140. https://doi.org/10.1111/geoj.12008

- Nilsen, T., & Njøs, R. (2021). Greening of regional industrial paths and the role of sectoral characteristics: A study of the maritime and petroleum sectors in an Arctic region. European Urban and Regional Studies 29, (2), 204–221. https://doi.org/10.1177/09697764211038412

- Normann, H. E., & Tellmann, S. J. (2021). Trade unions’ interpretation of a just transition in a fossil fuel economy. Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions, 40, 421–434. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eist.2021.09.007

- Nurdiawati, A., & Urban, F. (2022). Decarbonising the refinery sector: A socio-technical analysis of advanced biofuels, green hydrogen and carbon capture and storage developments in Sweden. Energy Research and Social Science. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.erss.2021.102358

- Öhman, A., Karakaya, E., & Urban, F. (2022). Enabling the transition to a fossil-free steel sector: The conditions for technology transfer for hydrogen-based steelmaking in Europe. Energy Research and Social Science, 84, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.erss.2021.102384

- Olson-Hazboun, S. K. (2018). Why are we being punished and they are being rewarded?” views on renewable energy in fossil fuels-based communities of the U.S. West. Extractive Industries and Society, 5(3), 366–374. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.exis.2018.05.001

- Pearse, R., & Bryant, G. (2021). Labour in transition: A value-theoretical approach to renewable energy labour. Environment and Planning E: Nature and Space, 5, 1872–1894. https://doi.org/10.1177/25148486211055542

- Pike, A., Rodriguez-Pose, A., & Tomaney, J. (2007). What kind of local and regional development and for whom? Regional Studies, 41(9), 1253–1269. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343400701543355

- Polanyi, K. (1944). The great transformation. Farrar & Rinehart.

- Rainnie, A. (2021). Regional development and agency: Unfinished business. Local Economy, 36(1), 42–55. https://doi.org/10.1177/02690942211023877

- Schulz, C., & Bailey, I. (2014). The green economy and post-growth regimes: Opportunities and challenges for economic geography. Geografiska Annaler B: Human Geography, 96(3), 277–291. https://doi.org/10.1111/geob.12051

- Snell, D. (2018). ‘Just transition’? Conceptual challenges meet stark reality in a ‘transitioning’ coal region in Australia. Globalizations, 15(4), 550–564. https://doi.org/10.1080/14747731.2018.1454679

- Sotarauta, M., Suvinen, N., Jolly, S., & Hansen, T. (2021). The many roles of change agency in the game of green path development in the North. European Urban and Regional Studies, 28(2), 92–110. https://doi.org/10.1177/0969776420944995

- Steen, M., & Njøs, R. (2019). Green restructuring, innovation, and transitions in Norwegian industry: The role of economic geography. Norsk Geografisk Tidsskrift, 73(1), 1–3. https://doi.org/10.1080/00291951.2018.1558281

- Stevis, D. (2018). US labour unions and green transitions: Depth, breadth, and worker agency. Globalizations, 15(4), 454–469. https://doi.org/10.1080/14747731.2018.1454681

- Stevis, D., & Felli, R. (2020). Planetary just transition? How inclusive and how just? Earth System Governance, 6, 100065. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esg.2020.100065

- Trippl, M., Baumgartinger-Seiringer, S., Frangenheim, A., Isaksen, A., & Rypestøl, J. O. (2020). Unravelling green regional industrial path development: Regional preconditions, asset modification and agency. Geoforum; Journal of Physical, Human, and Regional Geosciences, 111, 189–197. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2020.02.016

- Trippl, M., & Tödtling, F. (2018). Regional innovation policies for new path development – beyond neo-liberal and traditional systemic views. European Planning Studies, 26(9), 1779–1795. https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2018.1457140

- Wahlund, M., & Hansen, T. (2022). Exploring alternative economic pathways: A comparison of foundational economy and Doughnut economics. Sustainability: Science. Practice and Policy, 18(1), 171–186. https://doi.org/10.1080/15487733.2022.2030280

- Wang, X., & Lo, K. (2021). Just transition: A conceptual review. Energy Research & Social Science, 82, 102291. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.erss.2021.102291

- While, A., & Eadson, W. (2022). Zero carbon as economic restructuring: Spatial divisions of labour and just transition. New Political Economy, 27(3), 385–402. https://doi.org/10.1080/13563467.2021.1967909

- Zhao, K., Zhang, R., Liu, H., Wang, G., & Sun, X. (2021). Resource endowment, industrial structure, and green development of the Yellow River basin. Sustainability, 13(8), 4530. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13084530