ABSTRACT

Urban regeneration of previously developed, or brownfield, land requires a host of competing factors to ‘fall into place’ at the same time. This includes private finance to develop and deliver a vision for how an area will develop and integrate with the existing urban fabric. Governmental support is also essential to enable the development to take place. This paper focuses on the urban regeneration of Gloucester Quays by Peel Holdings, in the south-west of the UK, and uses a combined practice theory and systems of provision approach created by Williams et al. in Citation2019 to explore the factors that enabled the regeneration to occur. The paper explores each level of the governance structure and the practices that influence planning and development. It demonstrates that many different factors need to fall into place to enable regeneration to take place, and the system of provision model enables the identification of these factors.

JEL CLASSIFICATIONS:

1. INTRODUCTION

The regeneration of previously developed land (PDL), often known as brownfield land, has the potential to drastically enhance both the immediate environs as well as the wider town or city. Regeneration of former industrial areas, such as Baltimore’s Inner Harbour, have created vibrant centres and trip attractors in derelict post-industrial locations (Papatheochari, Citation2011). In the UK the benefits of similar regeneration schemes, such as London Docklands, have been disputed, as private places have been created rather than public spaces (Raco, Citation2003a), providing little benefit to the existing and surrounding population (Minton, Citation2009).

Urban regeneration is a drawn-out process taking many decades to be delivered often leaving areas derelict for many years before redevelopment. This paper seeks to understand the mechanisms that enable regeneration to occur by studying the case study of Gloucester Quays’ regeneration, a PDL development in the south-west of England. The regeneration of Gloucester Quays took place over several decades following the closure of the docks in the 1980s, with the work predominately completed by developer Peel Holdings. The case study therefore adds to the work of Harrison (Citation2014, Citation2021) who has studied Peel Holdings’ role in the regeneration of Manchester and Liverpool by exploring how Peel Holding’s methods work in smaller settlements.

Research exploring urban regeneration of PDL has predominantly focused on large-scale urban conurbations (Servillo et al., Citation2017), or smaller economically strong towns (Raco, Citation2003b). This paper therefore enhances our knowledge of the similarities and differences that exist when urban regeneration occurs in a socially deprived small to medium city. The paper uses social practice theory (Reckwitz, Citation2002: Schatzki, Citation1996: Shove et al., Citation2012), a novel approach in regeneration research, as a means of understanding both the system and the processes involved in the regeneration of Gloucester Quays.

The article explores the dynamics that exist within regeneration including people, organizations and funding that are involved in turning a derelict area of PDL into a thriving retail and entertainment hub. A social practices framework, developed by Williams et al. (Citation2019, p. 753), forms the basis of the article and is used to demonstrate the benefits social practice theory can provide in understanding how changes occurs within an urban regeneration scheme. By undertaking this research, it is possible to identify pathways that can unlock future regeneration schemes for local governments and developers in similar small to medium conurbations.

The remainder of the article is structured as follows. Section 2 provides an overview of current research in urban regeneration before providing more detail of the Gloucester case study. It also introduces the social practice model developed by Williams et al. (Citation2019) that will be tested in this paper. Section 3 outlines the research methodology, with the findings presented in section 4. Section 5 discusses the findings and outlines the benefits of using the Williams et al.’s social practice model for understanding complex delivery mechanisms and the implications for understanding of urban regeneration and other public–private schemes moving forward.

2. URBAN REGENERATION

The regeneration of PDL provides local governments the opportunity to regenerate unproductive areas focusing on enhancing economic growth and providing inner city property development (Tallon, Citation2013) through creating ‘new consumption spaces’, delivering property-led developments to transform deindustrialized urban spaces (Raco, Citation2003b). In the 1980s, the UK government moved away from the public sector-led regeneration, focused on moving people and jobs away from inner cities (Tallon, Citation2013), towards property-led regeneration (Turok, Citation1992). The government were influenced by the success of the market-led approaches being delivered in North America, where the regeneration was seen as a ‘growth machine’ for a city (Harrison, Citation2021), bringing together a host of actors from the public and private sector, reducing the impact on public expenditure.

In several large urban conurbations with significant post-industrial land the UK government introduced urban development corporations, public funded, unelected non-governmental organizations (quangos) designed to regenerate areas such as London Docklands, Tyneside and Merseyside (Minton, Citation2009), and Trafford Park, Manchester (Trafford Park Development Corporation, Citation1998). As part of Trafford Park, the developers of Gloucester Quays, Peel Holdings, were responsible for the regeneration of significant areas around Manchester and Salford, including the regeneration of the Manchester Ship Canal and the delivery of the Trafford Centre in 1998 (Harrison, Citation2014).

A change of political direction in 1997 with the election of a Labour government led to several changes to regeneration in the UK. This included the dissolution of eight urban development corporations, including Trafford Park in 1998 (The Urban Development Corporations in England (Dissolution) Order, Citation1998). The new government’s approach was called ‘Urban Renaissance’ and was based on new regionalism, where regions became competitive territories through the creation of regional development agencies (Harrison, Citation2021) providing knowledge, decision-making and funding at the regional level (Atkinson et al., Citation2019). Urban Renaissance incorporated many of the previous government’s neo-liberal urban policies, but sought to address the disparities between private, property-led developments through the incorporation of policies that included previously excluded local communities (Tallon, Citation2013).

Urban Renaissance incorporated social policies designed to tackle deprivation and improve public services (Smith et al., Citation2007), however the outcomes and benefits were modest and had limited long-term impacts for the local populations (Lawless, Citation2010). Post-1997 urban regeneration policies have been criticized and called ‘neo-corporatism’ (Tewdwr Jones, Citation2011), as they retained the privatization public spaces, focusing heavily on property, over public spaces (Raco, Citation2003a), rather than providing community services and assets (Maliphant, Citation2014). This has meant that in many cases the local communities that lived in or close to the regeneration site have not benefited from the regeneration of the site over the longer term as the land has been owned by private businesses, management companies or private home owners, rather than becoming a public asset.

Peel Holdings and their partners, British Waterways, began to develop their plans for regenerating Gloucester Quays in this era of Urban Renaissance, where funding was available regionally and nationally, drawing the complex web of actors required to deliver the regeneration of Gloucester Quays.

2.1. Urban regeneration complexity

Urban regeneration schemes rarely meet a one-size-fits-all approach to development (Turok, Citation2009), formed of complex actor constellations, unique site-related issues and temporal variations that make each scheme unique. Understanding these complex systems and how they develop is essential to understanding how urban regeneration occurs. Urban regeneration is more that the delivery of new physical infrastructure for a town or city. Graham and Healey (Citation1999, p. 642) argue that ‘planning must consider relations and processes rather than objects and forms’, as Healey (Citation2007, p. 25) later clarifies: ‘It is within the complexity of this jostling and jumbling in specific situations that governance interventions are both shaped and come to have effects.’ Without this governance system and the associated finance, innovation, and expertise of public and private practitioners the PDL would remain undeveloped. It is complexity that is of interest, as at present we do not really understand how through all this complexity the pathways for delivery are formed and enable the regeneration process to occur.

Mitleton-Kelly (Citation2003) identified the principles of complex evolving systems, such as those that develop to deliver urban regeneration schemes can use elements drawn from both natural and social sciences and seek to explain the pathways for delivery. Mitleton-Kelly explains that the stages of development of a complex system are: self-organization, emergence, connectivity, interdependence, feedback, far from equilibrium, space of possibilities, co-evolution, historicity and time, path dependence – each of these leads to the creation of a new order. Within urban regeneration Atkinson et al. (Citation2019) describe this complexity at the first stage of the development process as a ‘bowl of spaghetti’, until the order is formed, where the structure becomes more organized and a ‘bowl of macaroni’, when the system and processes solidify. Whilst research has explored the processes of complex systems and urban regeneration we still do not understand how and why change occurs, what the trigger points are that enable to the process to take place. Practice theory offers the opportunity to understand how change occurs, by exploring the practices involved in urban regeneration, rather than the individuals involved in the process.

2.2. Social practice theory (SPT)

SPT is a sociological approach to understanding behaviour and takes a wider perspective than traditional psychological theories in understanding behaviour and behaviour change. As such SPT explores practices and their performance meaning that the individual is no longer the unit of inquiry (Chatterton & Anderson, Citation2011).

Theories of practice have been used for understanding a wide range of diverse practices from activities such as Nordic walking (Shove & Pantzar, Citation2005) and mixed martial arts (Blue, Citation2017) to understanding methods of delivering behaviour change initiatives through energy consumption (Gram-Hanssen, Citation2010) and travel modes (Spotswood et al., Citation2015). More recently social practice theory has been used to explore systems for delivering infrastructure (Williams et al., Citation2019) or understanding energy demand (Rinkinen et al., Citation2021). Social practice theory’s flexibility means that it is a useful tool in understanding the processes of delivering urban regeneration.

2.3. Practitioners or actors?

Schatzki (Citation1996, p. 89) defines a practice as, ‘temporally unfolding and spatially dispersed nexus of doings and sayings’. Reckwitz (Citation2002, p. 249), suggests that they are:

a routinized type of behaviour which consists of several elements, interconnected to one another: forms of bodily activities, forms of mental activities, ‘things’ and their use, a background knowledge in the form of understanding, know-how, states of emotion and motivational knowledge.

Practices are carried and performed by people who are ‘recruited’ to activities to perform the practices (Shove et al., Citation2004), so instead of focusing on actors and their ability to influence change, you instead focus on practitioners who are performing the practices of urban regeneration.

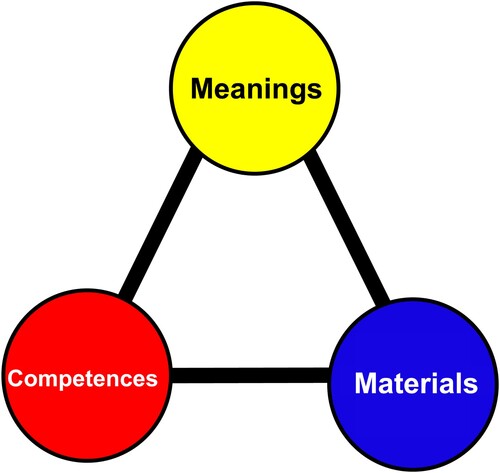

Shove et al. (Citation2012) simplify the various elements into: materials, competences and meanings and focus on the links between each of these elements (). The recruited performer or performers undertake these practices in relation to the materials available, the competences they possess to perform the practice and the meanings associated with the performance of the practice (Shove et al., Citation2012). This breakdown of practices is essential to understanding how change occurs, as the absence of materials or competences can have a direct impact on whether the practitioners are able to deliver the urban regeneration scheme. In addition, the importance placed on meanings within social practices is essential, as urban regeneration brings a complex range of actors from different sectors and levels of governance together and often their reasons for delivering urban regeneration schemes will not align. SPT offers an understanding of the co-evolution process described by Mitleton-Kelly (Citation2003). This provides a new way of understanding the processes of urban regeneration.

Figure 1. The 3-Elements model.

Source: Shove et al. (Citation2012).

2.4. Practice ecology

This complexity and interconnectivity of practices was termed ‘practice ecology’ by Kemmis et al. (Citation2009), as it provide a new and novel way of disentangling Atkinson et al.’s (Citation2019) ‘bowl of spaghetti’ complexity that characterizes urban regeneration and explaining how urban regeneration is delivered.

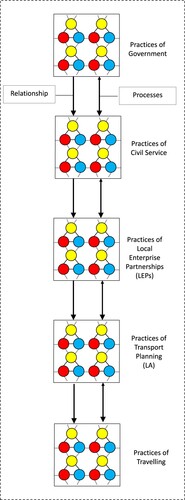

Williams et al. (Citation2019) identified funding as the starting point for creating change in practices when focusing on to the delivery of sustainable transport. They found that funding was essential to provide the new infrastructure (materials) and new skills (competences) and that funding needed to be incorporated into any understanding of how change occurs. To do this they developed a structure to demonstrate how practices within the national government influence the opportunity for people to change their travel behaviour. The authors explored the system of provision model developed by Fine (Citation2002). Fine describes a system of provision as a chain of activity that exists within a delivery network. The chain of activity’s construction is the key to change occurring within a system, something that is absent from Shove et al.’s (Citation2012) model. Williams et al. (Citation2019) used the system of provision to develop a framework of practices that enable meanings, materials, and competences to be transferred through a chain of practices ().

Figure 2. System of provision incorporating practices.

Source: Williams (Citation2015).

The practice ecology approach offers a novel means of understanding the where the points of change occurs within the governmental and private sector ‘ecosystems’. These changes move an area of PDL that has been derelict for decades into a new area of the city. It provide an opportunity to track where the meanings regarding the site are developed within the systems, where the competences come from to drive the development forward and where the materials to build come from. Practice ecology enables users to ‘follow the money’ through the system and demonstrate how and why change has occurred.

2.5. Case study: Gloucester Quays – background

The city of Gloucester is situated close to the River Severn in south-west England. The Severn in this area was difficult to navigate, and the completion of the Sharpness Canal in 1827 enabled Gloucester to compete with Bristol due to its proximity to the Midlands of England (Conway-Jones, Citation2009). Whilst other canals suffered with the competition caused by the construction of the railways after the Sharpness Canal’s completion (Glover, Citation2017), Gloucester thrived due to its rail links and lower costs than Bristol and its proximity to Birmingham. The port was used for importing foodstuffs and timber, whilst exporting salt (Conway-Jones, Citation2009). With the decline in timber and grain, petroleum became the primary product shipped in the 1930s. Trade, however, began to decline from the 1960s as the increase in ship size, competition from road transport and relocation of the petroleum works further south on the River Severn and the docks closed in 1988 leaving the architecturally significant warehouses empty and available for regeneration (Conway-Jones, Citation2009).

2.6. Case study: Gloucester Quays – complexity

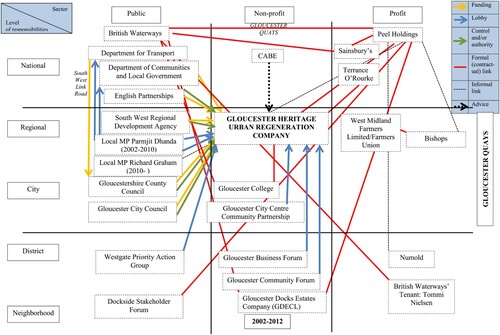

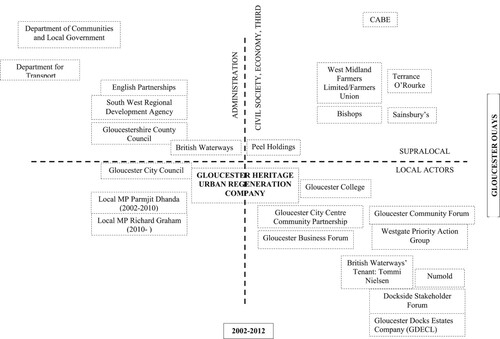

Despite its status as a city in the UK, Gloucester is what Servillo et al. (Citation2017) classed as a small to medium-sized town with a population of 129,000 (Gloucestershire County Council, Citation2017). The scale of a town or city does not, however, reduce the complexity of the delivery model, with the regeneration process of Gloucester Quays involving many public and private actors and funding bodies. Atkinson et al.’s (Citation2019) social network analysis (SNA) map () provides an overview of the number of actors and agents involved in the regeneration of Gloucester in the 2000s. Each of these practitioners brought different meanings, competences and materials to the regeneration process. Their SNA map places the Gloucester Heritage Urban Regeneration Company (GHURC), an organization set up by Gloucester City Council, Gloucestershire County Council, South West Regional Development Agency (SWRDA) and English Partnerships (now Homes England) at the heart of the regeneration process across the city.

Figure 3. Social network analysis (SNA) map of Gloucester Quays, 2002–12.

Source: Atkinson et al. (Citation2019).

The development of the Gloucester Quays site took place within the wider context of regeneration across the city as one of Gloucester’s ‘Magnificent Seven’ regeneration sites (Gloucester Renaissance, Citation2008), for which the GHURC were responsible for driving forward and securing funding before its disbandment in 2013.

2.7. Case study: Gloucester Quays – Peel Holdings and British Waterways

The development of the Gloucester Quays started before the founding of the GHURC in 2006 with a public–private partnership (PPP) between Peel Holdings and British Waterways.

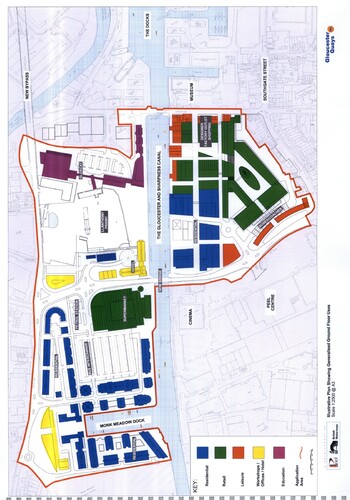

The Gloucester Quays site () was the amalgamation of two tranches of land, one owned by the now defunct non-departmental government organization (quango) British Waterways and the other owned private development company Peel Holdings. Peel Holdings had purchased their land from West Midland Farmers Ltd, who had undertaken a ‘rationalisation exercise’ of the site in 1993 to ensure that the site was vacated of tenants and businesses when Peel Holdings purchased the land in the late 1990s (Gloucester City Council, Citation1994). This means that Peel did not have any role in the displacement of existing residents and businesses. Neither Peel’s nor British Waterways’ sites were large enough to be developed separately, so British Waterways and Peel Holdings entered a PPP agreement to develop the land together. The motivations of both parties had several similarities, with both looking to develop the site, Peel to maximize their profit, building on their expertise from their work in Manchester, and British Waterways to enhance their existing assets, creating public spaces from area that were not accessible or useable before development due to their industrial heritage and the associated pollutants.

Figure 4. Gloucester Quays proposal, 2002.

Source: © Gloucester City Council.

The importance of the relationship between Peel and British Waterways in the regeneration of Gloucester Quays was underlined in Atkinson et al.’s (Citation2019) centrality map (). The map places both Peel and British Waterways at the centre of the regeneration process, for Gloucester Quays, as key actors in terms of their financial and land assets.

Figure 5. Centrality map of Gloucester Quays, 2002–12.

Source: Atkinson et al. (Citation2019).

3. METHODOLOGY

The research for this paper used an inductive grounded theory approach that generated data from interviews with key people involved in the regeneration of Gloucester Quays and the wider Gloucester area. The first stage of data collection involved a desk-based research of documents relating to the regeneration process, followed by a review of the relevant document in Gloucester City Council’s archives. A ‘snowballing approach’ was used from each interview that allowed the interviewee to provide other details of key actors within the regeneration process. This enabled access to the network of actors through personal contacts to both corroborate or contradict previous data provided by other interviewees. The findings were cross-referenced against official documents to build a comprehensive narrative around the regeneration process.

The interview data were transcribed and coded in NVivo to identify the key themes and issues that arose in the regeneration process. The data were then coded into primary categories: governance, partnership working; planning and public interest, the data in each of these codes being broken down into further subcodes to highlight how each development unfolded. In all 12 face-to-face interviews took place, as this has allowed interpretation of both verbal and non-verbal language used within the interview (Denzin, Citation2009). Each interview was semi-structures to allow the interviewer to retain control of the discussion and allow the interviewee to provide new topics and areas of that may be of interest to the research.

The interviews were used to develop a systems of provision/3-Elements framework (Williams et al., Citation2019) to identify where the materials, meanings and competences changed within the system and how this change enabled the regeneration process. The framework provides the opportunity to identify the key practitioners and understand how changes to the practitioners and the processes influenced the regeneration process. Interviews were conducted with developers, politicians (both local and national), local authority and government agency staff, and representatives of interest groups. A list of the interviewees and their references are shown in . The interviewees were involved with various stages of the regeneration process and provide a wealth of data, documents and leads that enhanced the findings of the research.

Table 1. Overview of interviewees.

does not include details of each interviewee’s role to comply with university ethical approval procedures, which have been implemented to protect participant anonymity.

4. FINDINGS

The interview responses have been used to illustrate how practices changed within the system of provision that enabled the regeneration process to take place in Gloucester. The findings are structured in relation to the various levels of the system and the practices and practitioner changes that occurred to enable the development to occur.

4.1. Private sector level

As discussed in section 2.8, Peel Holdings began purchasing the land various land holdings, then known as Bakers Quay in the 1990s and owned much of the land on the eastern side of the dock. The western side owned by government quango, British Waterways. Sections of the docks to the north of the site had already been developed after the closure in the 1980s, with several of the former warehouses converted to both flats and office use. Respondent GL3 explained: ‘British Waterways sold a long lease to the bulk of the dock estate in the 1980s to [developer] Crest Nicholson,’ and this meant that a precedent had already been set for the regeneration of the area. Peel, however, was looking to introduce a retail and leisure development, as well as constructing new private dwellings on the site. In 2002, a PPP deal was struck between Peel Holdings and British Waterways to develop the site, with planning permission submitted to Gloucester City Council in the same year ().

4.1.1. Meanings

The primary motivation for Peel Holdings, as the owners of the existing shopping development to the south of the site they were looking to maximize the value of their asset. This meant increasing footfall for this and the new site from the existing city centre to maximize profitability. Respondent GL10 explained that although this was the aim of the business, Peel saw themselves as ‘stewards’ of the site and that the development would have a ‘sympathetic use’ of the site in relation to its previous history. This included, ‘identifying and agreeing with councillors and stakeholders the key routes for a maritime heritage walk on the site’. This Heritage Walk has now been incorporated as a publicly accessible towpath and moorings for boats.

The stewardship of the area appears to be similar to Peel Holding’s developments in Liverpool and Manchester, where management of the land provided opportunities to influence development, of what respondent GL9 called Peel’s ‘raptor-like approach’ to development. Respondent GL10 stated that Peel’s stewardship lets them ‘help’ developers Rokeby make their adjacent development viable though the sharing of parking between the developments.

Respondent GL3, suggests, however, that protection of the existing assets was not always the primary goal of Peel Holdings due to ‘the different motivations and perspectives’ of both Peel Holdings and British Waterways. GL3 suggested that ‘British Waterways’ insistence on the reuse of the existing buildings would never have been the best commercial decision, and that through negotiation as part of the PPP agreement.’ GL3 stated that Peel Holdings eventually saw the benefits of retaining many of the original structures, although ‘a balance had to be struck’ between both organization’s perspective in relation to historic buildings that ‘couldn’t be commercially saved or reused in a way that was necessary’. Whilst retaining historic buildings may not have been the primary motivation for Peel Holdings, the site has benefited from the buildings Peel Holdings and British Waterways were able to preserve in the completion of the site.

4.1.2. Materials and competences

Respondent GL10 states that Peel Holdings are not ‘a flip developer’, as they are capital rich and able to fund their own developments rather than rely on external funding. This provides them with the materials that enable to them to develop sites and hold onto the site rather than divest their ownership to pay back their creditors as early as possible. Being capital rich allowed Peel Holdings to take a longer term vision on the regeneration of Gloucester Quays and enable the development to withstand the downturn to the UK economy that followed the international financial crisis of 2008.

As highlighted by John Harrison’s work (Harrison, Citation2014), Peel Holdings is an experienced developer of waterside and retail developments. GL10 explains: ‘Peel has fourteen different divisions from hotels to utilities, to outlets to various other uses and development types in terms of mixed-use development.’ This range of skills and access to capital has enabled Peel Holdings to purchase land and develop sites within their own timeframes, rather than be influenced by the availability of funding on the financial markets. However, despite this ability and acumen as an organization, the development of the Gloucester Quays site came to an impasse in 2003/04 and required the intervention of the local MP, Parmjit Dhanda, to unblock the barriers that were preventing the development from proceeding.

4.2. National government level

Parmjit Dhanda was MP for Gloucester between 2001 and 2010. During his nine years in office, Dhanda’s actions enabled the delivery of several schemes and was described by GL6 as, ‘instrumental in driving a lot of projects forward’ and ‘a great ally’ who could ‘step in and sort out problems’. Viewing Dhanda’s actions through a social practice lens shows that the introduction of a new practitioner with the competences to use the political tools available to take the regeneration forward was a key factor in the early development of the scheme.

Dhanda benefited from the meanings that existed within UK politics during this period following the Labour Party’s landslide victory at the 1997 and 2001 general elections. The politics in the UK in the early 2000s were dominated by the centre-left of politics by ‘New Labour’, and this government provided significant funding to local authorities to drive the country forward in the new millennium. As respondent GL8 explained, ‘the Gloucester parliamentary seat was historically a marginal constituency’. GL8 explained the benefits of this as, ‘I think we must have had the entire cabinet down at one stage or another and a whole plethora of junior ministers and shadow cabinet ministers as well from both parties throwing people at it constantly.’

With the materials (funding) made available through the national government, it was possible for the practitioner in the role of MP to ensure that some of this funding came to Gloucester rather than other areas of the country. This funding was pivotal in enabling the regeneration process aligned to Gloucester Quay to occur.

4.3. Government department, regional government and quango level

In the early 2000s a number of quasi-autonomous non-governmental organizations (quangos) existed in the UK that provided funding for regeneration. Many of which were closed or amalgamated in the ‘bonfire of the quangos’ in 2011, reducing their number by 245 (Dommett et al., Citation2014). Several of these quangos were essential for providing funding or assisting with the delivery process. The regeneration of Gloucester Quays benefited from multiple funding sources including the Department of Education, Department for Transport, English Partnerships, SWRDA and English Heritage in addition to the British Waterways PPP with Peal Holdings in 2001.

A section of land on the western side of the dock (, purple building) was earmarked as a site for a new educational site. Gloucester College had sold their existing site in the city centre to a developer and wished to create a bespoke, modern college. To assist with the development of the new site, respondent GL8 explained that the Minister of Education wrote a letter to the now defunct funding body the Learning and Skills Council, who awarded Gloucester College £35 million to deliver the scheme.

The funding was a significant development in the regeneration process as respondent GL8 explained: ‘We got the offer of the biggest grant that this country has ever seen for an FE college, £35 m. We had a site; we had a sale; and we had an opportunity.’ This funding was time limited and if the college was not delivered the offer of £35 million would be revoked. MP Parmjit Dhanda therefore became an essential practitioner in the negotiation process, bringing together the head of the college, British Waterways, Peel Holdings and the local authorities to identify a pathway to delivery in September 2004. British Waterways would only agree to release the land for the college if the retail development were approved. As an MP, Dhanda had the skills and authority (competences and meanings) to negotiate the decoupling of the college from the wider development on the proviso that Gloucester City Council fast-tracked the planning application for the wider generation of the site. This permission was granted in 2005 and the retail development moved forward.

With planning granted, access to the site became essential. Respondent GL6 explained that government body English Partnerships provided £7 million to build a link road that provided access to the south of the site over the dock. This became the High Orchard Bridge, which crosses the docks to the south of the site.

The High Orchard Bridge provided an essential link to the south-west link road, which provided access to the M5 motorway, bypassing the city centre. The South West bypass was a £40 million highway scheme, of which respondent GL8 explains was primarily funded by the Department of Transport: ‘That was a £40 m project … the bulk of it that the government was giving, and the County Council were left with about £7m–£10 m that they had to find locally or private contributions.’

One of the significant quangos involved in the regeneration process were the SWRDA. GL8 explains that ‘Regional Development Agencies turned out to be incredibly powerful because they had the power to come in and sweep up and buy parcels of land for £10s of millions or more.’ SWRDA had the funds to make the links that allowed the site to be pieced together and enable area wide regeneration to occur. It significantly influenced the meanings related to regeneration, as respondent GL7 explained:

In making a business case for investment there were a set of outputs that we sought to achieve: jobs, wider economic impact, and new businesses attracted to the area. A built environment that attracts businesses and economic activity, that attracts investment into Gloucester, that brings footfall and spend into the town. It has benefits on the wider economy and creates a place that people use, enjoy and can be proud of.

4.4. Local authority level

The City of Gloucester is controlled by a two-tier government system with Gloucestershire County Council responsible for several areas including highways maintenance, transport planning and strategic planning. Gloucester City Council is responsible for approving planning applications and housing, along with other services. It has been involved in the regeneration of the docks since their closure in the 1980s, buying the then derelict North Warehouse from British Waterways for just £1, spending £1.5 million to renovate the building, which reopened in 1986 (Conway-Jones, Citation2009). Whilst this and other developments took place in the warehouses in the northern section of docks, the majority of the area remained derelict in the early 2000s. Whilst there was a desire to renovate the area, there was little impetus or funding available to drive this forward from the local authorities.

The changes to the local MP and the agreement between Peel Holdings and British Waterways in 2002, and the funding from SWRDA and English Partnerships, meant that the materials and competences for change finally existed for regeneration to occur. Gloucester City Council, as the planning authority, would be required to grant planning permission. As a relatively small local authority that lacked the experience of reviewing complex multi-million-pound developments, the council lacked the competences to approve the regeneration of the site. As respondent GQ8 explained, ‘We had to train every single councillor to be a member of the planning committee and then go straight to full council decision.’

In 2007, following the decision to provide training to the councillors (competence), planning permission was granted and planning for the regeneration scheme was able to start. Both the county and the city councils were aware of the need to work together ‘for greater good’ and both signed up to be part of the GHURC.

4.5. Urban regeneration level

Parmjit Dhanda’s first question as an MP to then Prime Minister Tony Blair in 2001, as respondent GQ8 explained, was ‘whether the government would help set up an urban regeneration company in Gloucester’. With the ‘Magnificent Seven’ heritage sites identified within Gloucester (Gloucester Renaissance, Citation2008), expertise to deliver these complex schemes was required.

The UK government approved the creation of the GHURC in February 2004 and comprised of several partnering organizations including both councils, SWRDA and English Partnerships (Atkinson et al., Citation2019). GHURC had an annual budget of £750,000, which was designed to facilitate the regeneration process across the city, including the new college and shopping centre. One of the key actions of the GHURC board was to employ a new chief executive with the competences of delivering urban renewal schemes. The GHURC appointed Chris Oldershaw, who as respondent GQ6 explained, ‘worked on the Grainger Town Partnership in Newcastle’, before his appointment, a 53-hectare area of the city centre had been regenerated in the late 1990s (Historic England, Citation2021).

The appointment of Oldershaw was key to the success of the regeneration process, as respondent GQ10 explained: ‘The URC was very important because they could fund having people like Chris Oldershaw who understood redevelopment and regeneration. He was credible to the developers and to the council officers.’

The GHURC became the conduit between the developers and the planning officers within the local authority and provided a ‘the bridge to get both sides to see common sense’ (GQ10), and with the competences brought by the chief executive, the materials to link schemes through new infrastructure, due to the significant financial investment and the ability to manage the narrative and meanings of what should be delivered within the city. The GHURC, along with the PPP agreement between Peel Holdings and British Waterways drove the regeneration forward to delivery with the college opening in 2007 and the first phase of the shopping centre opening in 2009.

Despite the successful delivery of the Gloucester Quays development, the GHURC has been criticized for its focus on providing infrastructure over social benefits for the immediate community adjacent to the site. Respondent GL4, highlighted how there were 23 members of the GHURC board, with only one member focused on communities. When the GHURC’s budget was halved from £20 million to £10 million in 2010 (GHURC, Citation2010), the remaining money was spent on providing physical infrastructure, a walkway linking Gloucester Quays to the city centre, and the social elements of the GHURC’s work were cut completely.

5. DISCUSSION

The use of social practice theory, specifically Williams et al.’s (Citation2019) system of provision model, is novel in urban regeneration research. By highlighting the triggers that created changes to materials, meanings and competences in Gloucester, it is possible identify how and why the development took the form it has, a retail development that has used the existing historic warehouses. The evidence shows that Peel Holdings’ desire to develop and enhance access to their existing site, the Peel Centre, to the south of the development was the primary driver, whilst developing a new retail centre based on the docks. The research also shows that both British Waterways’ desire to retain the historic nature of the site, and the GHURC’s wider focus on the regeneration of seven sites, meant that Peel’s control of the area was far more limited than in Manchester or Liverpool.

The findings also demonstrate the importance of key elements to enable regeneration to occur: materials, meanings and competences, as changes to each of these elements ultimately impacted how the scheme was delivered. Skilled practitioners such as Chris Oldershaw, as the chair of the GHURC, and Parmjit Dhanda, as the local MP, were able to use their talents (competences) to unlock significant funding that benefited the city and future generations through the creation of jobs and the construction of a new college in the heart of the city. The management of the various funding streams, developer and community expectations enabled the physical infrastructure to be enhanced in Gloucester Quays, and across the city. This adds to Atkinson et al.’s (Citation2019) work which demonstrated the complexity of urban regeneration in Gloucester, through the ‘bowl of spaghetti’ analogy, through understanding the elements of change required to move a scheme forward.

The GHURC provided a focal point for regeneration funding between 2004 and 2014, that provided a benefit to Peel Holdings and the Gloucester Quays development by highlighting and focusing complementary funding for schemes that provided a direct benefit to Gloucester Quays such as the £7 million walking link between the city centre and the site. The bonfire of the quangos and subsequent closure of the GHURC in 2013 and considerable reduction in government funding post 2010 have provided Peel Holdings with the opportunity to fill this void in council budgets to become involved in the management of the Gloucester Docks Estate Company on behalf of the Council (GL10). This ‘stewardship’ model is similar to Peel Holdings’ model for the Atlantic Gateway highlighted by Harrison (Citation2014, Citation2021) where the site is not run by the state but by private investors.

The Gloucester Quays development differs from the Atlantic Gateway, however, as the site is ‘standalone’ from Peel Holdings’ primary base in the north-west of England, and as yet the company are yet to develop other sites in Gloucestershire. The second difference is that the majority of interviewees were broadly supportive of Peel Holdings’ work in the city. Gloucester, as a small to medium-sized city (Servillo et al., Citation2017), has a several competitors for trade, from Bristol to the south, Cheltenham to the east and Birmingham to the north. Without Peel’s substantial investment in the site, visitors to Gloucester Quays for shopping and leisure would go elsewhere.

The research builds on Harrison’s work by providing an alternative view of Peel Holdings’ practices from a smaller, socio-economically deprived conurbation, where the delivery has provided benefits to the city and the local government officials that outweigh the many negatives of Peel Holdings’ business approaches highlighted by Harrison (Citation2014, Citation2021). With Peel Holdings’ funding in place, the local government through the GHURC were able to leverage £77 million of public sector investment into the city by 2007 (GHURC, Citation2007).

SPT is an incredibly useful tool to understand the regeneration process, and this work’s contribution demonstrate the complex constellation of actors involved in a small to medium-sized town or city were not included in the development corporations of the 1980s, but were able to exert themselves to gain funding from SWDRA and other quangos discussed above. Understanding the trigger points within the system in a SPT context such as: Peel Holdings’ and British Waterways’ PPP, the appointment of a new MP, the availability of government funding, employing Oldershaw, all explain where the materials (funding), competences and meanings came from that enabled the scheme to be delivered. Regeneration in small to medium-sized towns and cities tend to be researched to a lesser extent than large conurbations such as Manchester or London, and this paper addresses this by highlighting the complexity that exists in the regeneration process. As with any research, the limitations are that the findings here relate to one specific case study. Williams et al.’s (Citation2019) model does, however, provide the opportunity to be used in different financial settings and for other urban regeneration schemes, including ones that have not been delivered. For developments in process, the model can help what materials and finances are in place, what meanings (motivations) are dominating the narrative and what competences are in place and where they are absent within the planning process. The research shows that many local authorities in the UK lack the skills and expertise to review, appraise and approve or reject complex planning schemes and in the case of Gloucester Quays this issue was identified and rectified to allow the correct process to be followed. Understanding where the gaps exist means that the systems of provision model can be an incredibly useful mode for delivering urban regeneration schemes in the future.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Funding

REFERENCES

- Atkinson, R., Tallon, A., & Williams, D. (2019). Governing urban regeneration in the UK: A case of ‘variegated neoliberalism’ in action? European Planning Studies, 27(6), 1083–1106. https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2019.1598020

- Blue, S. (2017). Maintaining physical exercise as a matter of synchronising practices: Experiences and observations from training in mixed martial arts. Health and Place, 46, 344–350. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthplace.2016.11.002

- Chatterton, T., & Anderson, O. (2011). An introduction to thinking about ‘energy behaviour': A multi model approach. DECC.

- Conway-Jones, H. (2009). Gloucester docks an historical guide. Black Dwarf Lightmoor.

- Denzin, N. (2009). The research act: A theoretical introduction to sociological methods. Aldine Transaction.

- Dommett, K., Flinders, M., Skelcher, C., & Tonkiss, K. (2014). Did they ‘Read Before Burning’? The coalition and quangos. Political Quarterly, 85(2), 133–142. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-923X.12072

- Fine, B. (2002). The world of consumption. Routledge.

- Gloucester City Council. (1994). Bakers quay draft planning brief (revised) 1994.

- Gloucester Heritage Urban Regeneration Company (GHURC). (2007). The renewal begins: The first annual report 2006/07. Gloucester: GHURC.

- Gloucester Heritage Urban Regeneration Company (GHURC). (2010). Shaping the future: 2009/10 annual report. Gloucester: GHURC.

- Gloucester Renaissance. (2008). Annual report 2006/7: Network news edition. Gloucester: Gloucester City Council.

- Gloucestershire County Council. (2017). Current population of Gloucestershire (Mid-2017): An overview. https://www.gloucestershire.gov.uk/media/2082290/current-population-of-gloucestershire-overview-2017.pdf.

- Glover, J. (2017). Man of iron: Thomas Telford and the building of Britain. Bloomsbury.

- Graham, S., & Healey, P. (1999). Relational concepts of space and place: Issues for planning theory and practice. European Planning Studies, 7(5), 623–646. https://doi.org/10.1080/09654319908720542/

- Gram-Hanssen, K. (2010). Residential heat comfort practices: Understanding us. Building Research & Information, 38(2), 175–186. https://doi.org/10.1080/09613210903541527

- Harrison, J. (2014). Rethinking city-regionalism as the production of new non-state spatial strategies: The case of Peel Holdings Atlantic Gateway strategy. Urban Studies, 51(11), 2315–2335. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098013493481

- Harrison, J. (2021). Seeing like a business: Rethinking the role of business in regional development, planning and governance. Territory, Politics, Governance, 9(4), 592–612. https://doi.org/10.1080/21622671.2020.1743201

- Healey, P. (2007). Urban complexity and spatial strategies: Towards a relational planning for our times. Routledge.

- Historic England. (2021). Several buildings in Grainger Town, Newcastle upon Tyne. https://historicengland.org.uk/advice/heritage-at-risk/20-years/grainger-town/.

- Kemmis, S., Wilkinson, J., Hardy, I., & Edwards-Groves, C. (2009). Leading and learning: Developing ecologies of educational practice. Symposium: Ecologies of practice. Wagga Wagga, NSW: Charles Sturt University, School of Education. Paper Code: WIL091156.

- Lawless, P. (2010). ‘Urban regeneration: Is there a future? People, Place & Policy Online, 4(1), 24–28. https://doi.org/10.3351/ppp.0004.0001.0006

- Maliphant, A. (2014). Power to the people: Putting community into urban regeneration. Journal of Urban Regeneration & Renewal, 8(1), 86–100.

- Minton, A. (2009). Ground control: Fear and happiness in the twenty-first-century city. Penguin.

- Mitleton-Kelly, E. (2003). Ten principles of complexity and enabling infrastructures. In E. Mitleton-Kelly (Ed.), Complex systems and evolutionary perspectives on organisations: The application of complexity theory to organisations (pp. 23–50). Pergamon.

- Papatheochari, D. (2011). Examination of best practices for waterfront regeneration. Littoral 02003. doi:10.1051/litt/201102003.

- Raco, M. (2003a). Remaking place and securitising space: Urban regeneration and the strategies, tactics and practices of policing in the UK. Urban Studies, 40(9), 1869–1887. https://doi.org/10.1080/0042098032000106645

- Raco, M. (2003b). Assessing the discourses and practices of urban regeneration in a growing region. Geoforum; Journal of Physical, Human, and Regional Geosciences, 34(1), 37–55. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0016-7185(02)00040-4

- Reckwitz, A. (2002). Toward a theory of social practices: A development in culturalist theorizing. European Journal of Social Theory, 5(2), 243–263. https://doi.org/10.1177/13684310222225432

- Rinkinen, J., Shove, E., & Marsden, G. (2021). Conceptualising demand: A distinctive approach to consumption and practice. Earthscan from Routledge.

- Schatzki, T. (1996). Social practices: A Wittgensteinian approach to human activity and the social. Cambridge University Press.

- Servillo, L., Atkinson, R., & Hamdouch, A. (2017). Small and medium-sized town in Europe: Conceptual, methodological and policy issues. Tijdschrift Voor Economische en Sociale Geografie, 108(4), 365–379. https://doi.org/10.1111/tesg.12252

- Shove, E., & Pantzar, M. (2005). Consumers, producers and practices: Understanding the invention and reinvention of Nordic walking. Journal of Consumer Culture, 5(1), 43–64. https://doi.org/10.1177/1469540505049846

- Shove, E., Pantzar, M., & Hand, M. (2004). Recruitment and reproduction: The careers and carriers of digital photography and floorball. http://www.lancaster.ac.uk/staff/shove/choreography/recruitmentandreproduction.pdf.

- Shove, E., Pantzar, M., & Watson, M. (2012). The dynamics of social practice. SAGE.

- Smith, I., Lepine, E., & Taylor, M. (2007). Disadvantaged by where you live? Neighbourhood governance in contemporary urban policy. Policy Press.

- Spotswood, F., Chatterton, T., Tapp, A., & Williams, D. (2015). Analysing cycling as a social practice: An empirical grounding for behaviour change. Transportation Research Part F, 29, 22–33. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trf.2014.12.001

- Tallon, A. (2013). Urban regeneration in the UK. Routledge.

- Tewdwr Jones, M. (2011). Urban reflections: Narratives of place, planning and change. Policy Press.

- The Urban Development Corporations in England (Dissolution) Order. (1998).no.953, Article 2. Available at: https://www.legislation.gov.uk/uksi/1998/953/article/2/.

- Trafford Park Development Corporation. (1998). Trafford Park development corporation 1987–1998. https://web.archive.org/web/20071003035647/http://www.poptel.org.uk/trafford.park/.

- Turok, I. (1992). Property-led urban regeneration: Panacea or placebo? Environment and Planning A, 24(3), 361–379. https://doi.org/10.1068/a240361

- Turok, I. (2009). ‘The distinctive city: Pitfalls in the pursuit of differential advantage. Environment and Planning A, 41(1), 13–30. https://doi.org/10.1068/a37379

- Williams, D. (2015). Social practice theory and sustainable mobility: An analysis of the English local transport planning as a system of provision PhD. University of the West of England.

- Williams, D., Spotswood, F., Parkhurst, G., & Chatterton, T. (2019). Practice ecology of sustainable travel: The importance of institutional policy-making processes beyond the traveller. Transportation Research Part F, 62, 740–756. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trf.2019.02.018