ABSTRACT

Rural social enterprises (RSEs) represent an emerging actor in rural and local socio-economic development. The study of RSEs recognizes the importance of place-based actions for development. Social impacts of RSEs have been touted, particularly in filling roles in the rural context that are underperformed by governments and private actors. However, RSEs’ social impact measurement remains emerging. This review confirms that measurement of RSEs’ social impact, and its attribution to RSEs’ interventions, remain underdeveloped and lacking in both rigour and consistency. Solutions are proposed that contribute to improved methodological approaches applicable to rural regions and appropriate for related interventions confronting spatial disparities in rural development.

1. INTRODUCTION

Social entrepreneurship, a field that spans disciplines (Bruin & Teasdale, Citation2019; Morris et al., Citation2020; Saebi et al., Citation2019) is emerging in regional studies and economic geography to address roles that place-based actions (cf. Horlings, Citation2015) play within and for their regions (Steiner & Teasdale, Citation2019). Social enterprises (SEs) that are focused on rural development (thus part of mainstream rural businesses (Norris, Citation2020), hereafter rural social enterprises (RSEs),Footnote1 have the potential to contribute to solving intractable challenges such as poverty and inequality, which are disproportionately faced in rural areas (Breau & Saillant, Citation2016; World Bank, Citation2021). RSEs deliver products and services in rural areas using market-based approaches (Musinguzi et al., Citation2022aa, Citation2023; Steiner & Teasdale, Citation2019; van Twuijver et al., Citation2020). Programmatically, they are a development strategy that reduces rural poverty and inequality through their social impacts (Eversole et al., Citation2014; Musinguzi et al., Citation2022a, Citation2022bb, Citation2023; Olmedo & O’Shaughnessy, Citation2022; O’Shaughnessy et al., Citation2022).

In development, rurality (Pike et al., Citation2010) commonly poses challenges related to inadequate resources and service supply (Steiner & Teasdale, Citation2019; Ward & Brown, Citation2009). Restricted product and service provision negatively affects rural dwellers and leads to their disproportionate exposure to grand challenges such as high poverty rates and inequality (World Bank, Citation2021). These factors make rural areas undesirable for the operations of mainstream private and government service providers. It is thus vital to focus on ‘rural’ towards achieving local and regional development (Leeuwen, Citation2019; Ward & Brown, Citation2009).

Cavanaugh and Breau (Citation2017) remark that ‘regional scientists have yet to focus much attention on understanding the changing dynamics of inequality across rural regions’. Martin (Citation2021, p. 153) argues that scholars conducting regional studies should ‘take a much more explicitly progressive stand and strive through their theoretical, empirical and public engagement for fair and equitable regional and local outcomes’. However, rural areas have received little attention in social entrepreneurship (Steiner et al., Citation2019; Steiner & Teasdale, Citation2019; Weerakoon, Citation2021). Muñoz (Citation2010) set out a geography-oriented research agenda for social entrepreneurship, featuring spatially oriented social entrepreneurship studies. However, this field is multidisciplinary, and there persists limited available synthesis by systematic literature review (SLR) of studies of RSEs (see van Twuijver et al., Citation2020, for an exception featuring European RSEs), particularly of social impacts and their measurement.

Social impacts, and their measurement, in social entrepreneurship remain underdeveloped theoretically and empirically (Hertel et al., Citation2020; Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), Citation2015; Rawhouser et al., Citation2019). Initiatives towards theoretical/conceptual understanding of social impact measurement have appeared (e.g., Arena et al., Citation2015; Bagnoli & Megali, Citation2011; Grieco, Citation2015; Hertel et al., Citation2020; Irene et al., Citation2016), as have efforts in empirical social impact measurement (e.g., Rawhouser et al., Citation2019). However, the existing theoretical/conceptual frameworks lack an explicitly rural approach, notably on the definition of social impacts, while received empirical work does not address the measurement of these impacts and associated methods.

Many published social entrepreneurship studies report positive social impacts, generating concerns about potential bias towards ‘success stories’ (Dees et al., Citation2008, Amin et al., Citation2002, cited in Muñoz, Citation2010). This is resounded by Vázquez-Maguirre et al. (Citation2018, p. 327) who note that social impact as a ‘concept is encumbered with the pragmatism of administrative theory, characterized by the documentation of only good practices or successful business cases’. Thus, such positive narratives that lead to assuming that SEs generate positive social impacts on their beneficiaries’ livelihoods should be further assessed’ (Vázquez-Maguirre et al., Citation2018). Davies et al. (Citation2019, p. 1619) note that ‘much of the current SE literature has adopted a positive management frame in which advantageous values, virtues and impacts are proselytized’ rather than a critical analysis of the field (Dey & Steyaert, Citation2012). Thus, understanding and measuring SEs’ social impact could enable cognizance of the importance and contribution of SEs in development, and indeed could contribute to the establishment of SEs’ legitimacy (Molecke & Pinkse, Citation2020; Sarpong & Davies, Citation2014). Without such understanding, there exists a danger of overhyping SEs and their being discarded in the future as a development fad (Lyon, Citation2009) in general terms and particularly within the local and rural development context which is a focus for this study.

This paper responds to these gaps in the literature with a SLR. It has the following objectives: (1) to map extant RSE studies measuring social impact, and their measurement approaches; and (2) to propose future social impact measurement approaches in RSEs, based on gaps identified.

To the authors’ knowledge, it is the first SLR addressing these subjects. It extends to 21 empirical studies published in the period 1987–2019, and introduces a fresh conceptualization, understanding and application of social impact measurement in rural development. It advocates methodological approaches such as: (1) a definition of social impact, through applying relevant existing frameworks within RSE studies; (2) identifying the appropriate operational level for social impact measurement; and (3) identifying rigorous analytic techniques, specifically for attribution. We attempt to advance methodological rigour in RSEs’ social impact measurement, and thus advance both scholarship and management of RSEs. We also answer Harrison et al.’s (Citation2019) call to extend the conceptual and methodological boundaries of regional studies as well as Martin’s (Citation2021, p. 154) agenda of advocating methods for articulating ‘an unassailable case for reducing spatial disparities’ particularly in rural areas.

The remainder of the paper is structured as follows. Section 2 highlights key existing literature focussing on social impact measurement. Section 3 presents the SLR approach that employs the preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses and the sample, phenomenon of interest, design, evaluation, research type frameworks for assembly and analysis of material. Section 4 presents the results. Section 5 discusses the findings reflecting on four methodological themes and future research directions. Section 6 concludes the paper.

2. SOCIAL IMPACTS OF SEs AND THEIR MEASUREMENT

Social impact of SEs is referred to variously as social value, public value, social performance, social returns, social output, environmental performance, triple bottom line, social performance, environmental impact, social accounting, non-financial performance, and others (Hertel et al., Citation2020; Rawhouser et al., Citation2019). This inconsistent nomenclature impedes academic advancement (Rawhouser et al., Citation2019). Despite disagreement on the nomenclature, and on the definition and measurement of SEs’ social impact (Hertel et al., Citation2020; Ormiston, Citation2019; Rawhouser et al., Citation2019), as explored further below, most scholars concur that understanding social impact is essential to advancing social entrepreneurship in academia and in practice (Barraket & Yousefpour, Citation2013; Grieco, Citation2015; Hertel et al., Citation2020; Rawhouser et al., Citation2019).

Measurement of social impact is variously interpreted (OECD, Citation2021). Vanclay (Citation2003, p. 6) notes that it ‘includes the processes of analysing, monitoring and managing the intended and unintended social consequences, both positive and negative, of planned interventions and any social change processes invoked by those interventions’. It is beset with definitional inconsistencies even in established fields such as international development (Belcher & Palenberg, Citation2018) and evaluation (Vo & Christie, Citation2018). The OECD (Citation2021, p. 28), states that in measuring social impacts, the following changes should be considered: ‘the effects achieved by others (alternative attribution), those that would have happened anyway (deadweight), potential negative consequences (displacement), and sustainability over time (drop-off)’.

Research in the impact evaluation field is converging towards defining social impacts in terms of changes that are brought about by actions or effects which are produced by a particular intervention, regarding the extent of achievement of an intervention’s objectives (Ebrahim, Citation2020, cited by Hertel et al., Citation2020). Disagreement on a definition of SEs’ social impact (Hertel et al., Citation2020; Rawhouser et al., Citation2019) persists: Hertel et al. (Citation2020, p. 7) note that an emerging focus interprets social impact as ‘intended, positive effects on a target audience’. Exceptions include: Vanclay’s (Citation2003) definition that encompasses both the intended and unintended social consequences of interventions; Pärenson (Citation2011) who emphasizes the inclusion of both positive and negative impacts, and Nicholls (Citation2018) who considers social impact to be the effects on targeted beneficiaries which can be both positive and negative. Amongst such variety in definition and nomenclature, the OECD (Citation2015) notes that social impact measurement by SEs themselves is not currently widespread because they have limited resources (both financial and human) suited to the task. Further to this, SE practitioners note that pursuing social impact measurement can be unrealistic and confusing (Adams et al., Citation2017; McCreless & Trelstad, Citation2012, cited in Hertel et al., Citation2020). There are other reasons for choosing to measure social impact or not in SEs beyond limitations imposed by resources and these include alternative priorities for some social entrepreneurs (e.g., Barraket & Anderson, Citation2010; Siqueira et al., Citation2021), past experiences with social impact measurement (e.g., Ormiston, Citation2022), the rationale for measurement such as measuring performance improvement (van Rijn et al., Citation2021), and to obtain financial resources from new funders or meet the compliance demands of existing ones (Barraket & Anderson, Citation2010; Barraket & Yousefpour, Citation2013; Nguyen et al., Citation2015; van Rijn et al., Citation2021).

To facilitate understanding of social impact measurement in RSEs, we need to understand how SEs have previously been framed in relation to their function and disciplinarity. This provides bases for methodological elements to consider in the measurement of social impacts. Academics in the social entrepreneurship field have conceptualized SEs as development actors or as having a development model, intervention or programmatic base (e.g., Cieslik, Citation2016; Venot, Citation2016) aimed at regional/rural development in RSEs (e.g., Eversole et al., Citation2014; Musinguzi et al., Citation2022a, Citation2022b). It is noted that SEs combine existing development ideas/models and reframe them in new and unique ways for addressing contemporary and complex challenges of development (e.g., Chandra, Citation2018). SEs’ development basis does not however justify ‘positive framing’ (Dart, Citation2004; Venot, Citation2016) in the absence of critical understanding of SEs’ social impact creation.

Given SEs’ promise in contributing to development, and in the case of RSEs rural and regional development, development literature offers insights for social impact evaluation methods. The basis of impact measurement from development literature would ideally be at the core (e.g., Abadie & Cattaneo, Citation2018; Barnett et al., Citation2020; Duflo et al., Citation2008; Vinod & Chindarkar, Citation2019). This includes attribution – impact evaluation requires differentiating programme effects from other confounders (factors), and addressing selection bias (Abadie & Cattaneo, Citation2018; Barnett et al., Citation2020; Duflo et al., Citation2008; Vinod & Chindarkar, Citation2019). The emerging SE literature on social impact evaluation strongly supports this attribution emphasis (e.g., Caló et al., Citation2021; Rawhouser et al., Citation2019). Development literature also advocates the explicit use of a counterfactual. Development literature divides impact evaluation approaches into ex ante and ex post (Khandker et al., Citation2010, cited in Barnett et al., Citation2020). Whichever the case, the emphasis is on ‘what would have happened to programme beneficiaries/participants if they had not been involved’. Reporting results of programmes’ achievement according to stated objectives is insufficient to determine whether it indeed created these achievements. This is because, organizations including RSEs are involved in implementing particular interventions/programmes with targeted clients/beneficiaries based on the objectives/ aims of the intervention and the needs of the target group. The associated selection bias then requires statistical techniques which put into context the observed and unobserved variables that affect self-selection (e.g., Abadie & Cattaneo, Citation2018; Duflo et al., Citation2008; Vinod & Chindarkar, Citation2019).

Approaches taken to measurement of social impact in the social entrepreneurship context include mixed method, quantitative and qualitative approaches. Notwithstanding the foregoing’s tendency toward quantitative approaches, social entrepreneurship literature features mixed method approaches (both qualitative and quantitative techniques) as the most feasible (e.g., Caló et al., Citation2021). This is because SEs’ core purpose is mission achievement (Grieco, Citation2015; OECD, Citation2015; Peattie & Morley, Citation2008) which can be best measured using both qualitative and quantitative methods.

Quantitative approaches applied in social impact measurement include the use of experiments or quasi experimental methods (e.g., Caló et al., Citation2021; Wry & Haugh, Citation2018). These apply techniques such as correlation analysis, propensity score matching and multivariate difference-in-difference (DiD) models. Qualitative approaches are also applied widely, including realist evaluation employing identified context–mechanism–outcome (CMO) configurations for explaining why particular causal links materialize or not in the logic model or Theory of Change (ToC) (e.g., Caló et al., Citation2019, Citation2021). This has been applied in combination with a quasi-experimental method for attribution purposes (Caló et al., Citation2021).

Other qualitative approaches include contribution analysis (CA) (Befani & Mayne, Citation2014; Delahais & Toulemonde, Citation2012) and process tracing (PT) (Trampusch & Palier, Citation2016) that provide attribution of impacts to an organization. In terms of data, these social impact evaluation methods are based on narrative causal statements elicited from the beneficiaries/participants of interventions and other relevant actors without use of a control group (BetterEvaluation, Citation2016). The attribution logic appears through the beneficiaries’ own accounts of the casual mechanisms as analysed through the lens of CA and PT (Befani & Mayne, Citation2014; Punton & Welle, Citation2015a, Citation2015b).

CA is a process-based evaluation technique developed by Mayne as a response to the issues which arose in the assessment of cause and effect of complex interventions extending to policies, programmes, services or other interventions for which experimental designs are infeasible (Mayne, Citation2001). Rather, a causal chain is established alongside the relative influence of exogenous factors, in the ToC model (e.g., Befani & Mayne, Citation2014; Delahais & Toulemonde, Citation2012). CA acknowledges that there are many and complex processes at play in order to achieve an impact or outcome and thus helps in the estimation of organizations’ contribution.

PT is a qualitative method in the social sciences in which probability tests are used to assess evidence strength in specified causal relationships within a case without using a control. It helps to establish confidence in how and why an effect of an intervention occurred, hence going beyond most statistical evaluation designs (Punton & Welle, Citation2015a, Citation2015b). PT helps in understanding both the evidence and its strength (Punton & Katharina Welle, Citation2015a, Citation2015b). Some authors advise integration of these methods in conducting impact evaluation studies (Befani & Mayne, Citation2014). In the context of RSEs, CA and PT could enable a thorough understanding of the sequence and causal steps RSEs’ interventions have gone through to achieve the intended outcomes/social impacts. Implementation of such methods is enhanced by the use of a logic model, or ToC tools. These facilitate understanding of social impacts as proposed by the OECD (Citation2021, cited in Hertel et al., Citation2020), Ebrahim (Citation2020) and Wry and Haugh (Citation2018), and provide conceptual clarity. They facilitate the identification of relevant indicators and cause-and-effect pathways for interventions (OECD, Citation2021; Hertel et al., Citation2020; Wry & Haugh, Citation2018). They are commonly used in the field of evaluation (Clark et al., Citation2014; Ebrahim, Citation2020) and are receiving attention in social entrepreneurship (Hertel et al., Citation2020; Wry & Haugh, Citation2018). A logic model for a RSE outlines linkages amongst five basic components (input, activities, outputs, outcomes and impact) (cf. Clark et al., Citation2014; So & Staskevicius, Citation2015). The ToC, on the other hand, is more detailed and goes beyond the linear representation of a programme to elaborate how and why the desired change is expected to happen (Clark & Anderson, Citation2004). For RSE management and social impact measurement purposes, these tools can illustrate how an intervention or project should work. They offer several other functions when used in RSE social impact evaluation, such as easing goal articulation, providing better understanding of the RSE intervention or project including how goals can be achieved, guidance in planning, design and execution of the social impact measurement processes and establishing the correct scope of the activities internally.

The measurement of social impacts requires an understanding of what to measure in terms of social impact indicators and this is aided by a well-developed logic model/ToC. Existing performance frameworks in social entrepreneurship provide indicators (also termed dependent variables in the field of economics) commonly used for measuring social impacts on their beneficiaries/clients (independent variables in economics). Common dependent variables include: percentage of clients finding a permanent job in work integration SEs; poverty reduction; contributions to local associations; net income changes; job creation; increased skills or knowledge; promotion of democracy and civic engagement; citizen engagement; democratization and political advocacy; and women’s empowerment (e.g., Bagnoli & Megali, Citation2011; Irene et al., Citation2016; Penna, Citation2011; Slaper & Hall, Citation2011). In the context of RSEs, there are currently no explicit indicators. Emerging literature (e.g., Musinguzi et al., Citation2022) note the following:

increased independence of participants; reduced isolation of participants due to increased capability to travel through rural transport provision; improved access to health and related care services; economic resilience through job creation; addressing rural market failure through promoting local commodity marketing; stimulation of voluntary and collaborative community culture; supporting and building skills amongst young people; environmental education; promoting sustainable energy and agricultural production etc.

Other available information sources include the RSE Hub established by Inspiralba Ltd,Footnote2 which lists information on RSEs and what they have achieved. Other RSE-related indicators are available from the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI), which contains general and sector-specific indicators (GRI, Citation2021).

Given the many possible social impact indicators of SEs, their reduction could be vital in cases where comparison between many RSEs is a concern. To this end, multidimensional indices are emerging such as Hertel et al.’s (Citation2020) civic wealth index. There are existing multidimensional indices such as the multidimensional poverty index (MPI) (Alkire & Santos, Citation2013) from development and economics fields that could be adapted to measure poverty reduction as an indicator for social impact in RSEs.

The social impact indicators mentioned in the context of RSEs link to rural livelihoods and well-being, which in turn connects to an existing overarching approach within the development literature: the rural livelihoods or sustainable livelihoods framework (DfID, Citation1999; Scoones, Citation2015). This framework has an emerging linkage to rural social entrepreneurship studies (Laeis & Lemke, Citation2016; Masukujjaman et al., Citation2016). Borrowing of theories and/or concepts and frameworks from other fields to enrich an emerging field such as (rural) social entrepreneurship has been encouraged by other researchers such as Vo and Christie (Citation2018) regarding research between evaluation and impact measurement and Bruin and Teasdale (Citation2019) and Haugh (Citation2012) on social entrepreneurship.

3. METHODOLOGY

Researchers have undertaken a number of SLRs on aspects of social entrepreneurship, and SEs. SLRs have been preferred by scholars to narrative literature reviews, as they overcome researcher bias through comprehensive search and analysis strategies such as cross-referencing between researchers, extensive search of scientific databases and use of a transparent exclusion/inclusion criteria (Phillips et al., Citation2015; Tranfield et al., Citation2003). For instance, Gupta et al.’s (Citation2020, p. 211) SLR identifies 21 earlier SLRs. There are also a number of related SLRs in the social entrepreneurship field (e.g., Aliaga-Isla & Huybrechts, Citation2018; Bansal et al., Citation2019; Bozhikin et al., Citation2019; Buratti et al., Citation2022; Persaud & Bayon, Citation2019; Phillips et al., Citation2015; Rawhouser et al., Citation2019; Roy et al., Citation2014; Saebi et al., Citation2019; Short et al., Citation2009; Stephan & Drencheva, Citation2017; Suchowerska et al., Citation2019; Tan et al., Citation2019; van Lunenburg et al., Citation2020; van Twuijver et al., Citation2020). Out of this number of SLRs, just two have to date explicitly covered issues related to RSEs, specifically as a solution to contemporary rural development challenges globally (Buratti et al., Citation2022) and in Europe (van Twuijver et al., Citation2020). These papers mention some impacts/contributions of RSEs but do not address issues considered in this study. Only one study, Rawhouser et al. (Citation2019) reviews social impact measurement but these authors note that the data used in their SLR are mostly drawn from papers from developed or industrialized countries. The review also does not conduct a detailed analysis of social impact measurement methods from empirical studies, nor does it have an explicit focus on rural and regional development aspects.

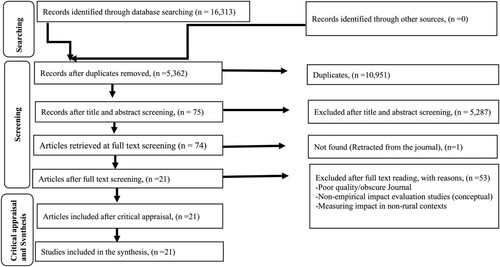

Our SLR uses an adapted version of PRISMA (Moher et al., Citation2009 in Krupoderova & Portnov, Citation2020). The PRISMA is a protocol that facilitates the understanding and appraisal of methods for review (Moher et al., Citation2009). This approach is commonly applied in medical science reviews but it is increasingly being applied in business and management including social entrepreneurship (Aliaga-Isla & Huybrechts, Citation2018) with an emerging application in Regional Studies, Regional Science (e.g., Krupoderova & Portnov, Citation2020). The PRISMA framework provides a checklist that facilitates preparation and reporting of a rigorous protocol for a SLR (Moher et al., Citation2009). It generates comprehensive and replicable search results, that is, identification of a range of studies of interest for a particular topic for determining the known and unknown for a given period (Denyer & Tranfield, Citation2009) and thus is advantageous when compared with a random search of information which can be selective regarding thematic coverage and resulting summary findings.

We developed and employed a template (see Table A1 in Appendix A in the supplemental data online) for consistent data extraction, with variables used obtained from: (1) authors’ judgement on suitability based on the objectives of the SLR; and (2) existing analytical tools used for SLR synthesis (e.g., Sample, Phenomenon of Interest, Design, Evaluation, Research type framework – SPIDER; Cooke et al., Citation2012) that was adapted (). The SPIDER is a framework suitable for use in review studies of qualitative and mixed method research designs (Cooke et al., Citation2012). It assists researchers in mapping ‘the primary dimensions of research designs that involve qualitative or mixed research methods’ (Suchowerska et al., Citation2019, p. 7).

Table 1. Theory and method applied in the studies.

Our search strategy employed a comprehensive search of relevant databases.Footnote3 Databases were selected with advice from a University librarian as they are main sources for business, management and regional science information. Further to this, they are recognized internationally as academic sources that cover journals indexed for impact factor.

The search was confined to the period 1987–2019, sufficient to capture RSE studies given the field’s evolution (Short et al., Citation2009). The 1987 starting year was also used in a related SLR (Phillips et al., Citation2015), while the most recent related SLR uses the period 1996–2016 (Rawhouser et al., Citation2019). Our study deviates from most prior SLRs by its slightly longer time frame, and by its explicit rural focus.

Search termsFootnote4 featured variants on the names given to SEs/RSEs, for example, social entrepreneurship, social entrepreneurial organizations, social ventures, social entrepreneurial ventures, community-based enterprises plus other selected keywords related to rural/regional development (see Table A2 in Appendix A in the supplemental data online), and accessed only English language publications. We use peer review as an indicator of academic quality (Kraus et al., Citation2020), as well as SCImago Journal Rank and Scopus quartile rankings (Thananusak, Citation2019) (see Table A3 in Appendix A online). Following Heyvaert et al. (Citation2013), our inclusion criteria after full text review required (1) clearly defined social impacts, and indicators used to measure them; and (2) a rural focusFootnote5 and targeting the conditions of rural populations. Studies that were non-empirical in nature were excluded and this occasioned a sharp fall in the total number of eligible articles (21) ().

Figure 1. Systematic literature review flow diagram based on the adapted version of the PRISMA diagram.

Sources: Moher et al. (Citation2009), cited by Krupoderova and Portnov (Citation2020).

4. RESULTS

4.1. Academic domain, sector and location

The 21 articles included in this SLR are drawn from 18 journals. All journals in the sample published at least one article each, with the exception of Social Enterprise Journal from which four papers were drawn. The 18 journals cover a range of domains with 14 articles under business and management, but all the articles address the broad area of community development, relevant to regional/rural development. No captured study predated 2010 (see Table A4 in Appendix A in the supplemental data online). A peak of seven studies appears in 2016. The absence of studies published between 1987 and 2010 suggests recent emergence of empirical measurement of social impacts in RSEs.

The RSEs studied span the continents, confirming that (rural) social entrepreneurship is an international phenomenon (Short et al., Citation2009). Thirteen of our sample articles are located in developing countries (see Table A4 in Appendix A in the supplemental data online). This may reflect not that RSEs are more studied in such countries, but rather that most of the studied RSEs were originally non-governmental organizations (NGOs) or are NGO spinoffs as well as have been funded partly by external donors and funders (e.g., Barstow et al., Citation2016; Bonny & Rajendran, Citation2013; Cieslik, Citation2016; Kabeer & Sulaiman, Citation2015; McKague & Tinsley, Citation2012; Mohanan et al., Citation2016; Torri, Citation2010). A further consequence of this genesis for RSEs is that they are likely to conduct social impact measurement in order to comply with their external stakeholders’ expectations, as noted in extant literature (e.g., Barraket & Yousefpour, Citation2013; Nguyen et al., Citation2015).

4.2. Studies’ methods, samples and theoretical basis

The most commonly used data collection methods () include interviews (used in 11 studies), focus group discussions (six) and participant observation (six), followed by surveys (four), document reviews (two), ethnography (one) and workshops (one). All studies in the sample used a case study approach: 14 used a single case, two used two and the remaining five each used three, nine, 10, 20 and 50 cases, respectively. Further, 13 papers in our sample were qualitative in nature and applied qualitative techniques such as realist evaluation to measure social impact. Others conduct thematic and content analysis to describe respective RSEs’ social impacts. Fifteen studies explicitly state a theory and/or a concept and six more implicitly do so. Thirteen theories/concepts have been applied in situating the theoretical underpinning of the studies and they include the following with the number in parentheses indicating the number of studies applying that theory/concept: social entrepreneurship (six), ToC (three), impact evaluation (two), realist evaluation (two), spaces of well-being and therapeutic assemblage (two), empowerment (two), global commodity chain (one), community/rural development (two), hybrid organization (one), moral economy (one), social exchange/community agency (one), entrepreneurship (one) and community entrepreneurship (one) ().

Eight studies used quantitative methods for social impact measurement: correlation, propensity score matching (PSM) and DiD. Two studies used a quasi-experimental design to address selection bias, 17 studies used purposive (non-probability based) sampling, while in four it was random. These findings indicate that self-selection and attribution are in general not accounted for in social impact evaluation of RSEs. Of the eight studies that applied a quantitative approach to social impact measurement, five papers used solely quantitative methods while three used mixed methods.

4.3. Definition and terminology for social impact measurement

As shows, social impact is defined in various ways across the studies included in this SLR, which concurs with extant literature regarding definitional issues (e.g., Grieco, Citation2015; Hertel et al., Citation2020; Rawhouser et al., Citation2019). Although this poses a challenge to researchers, we adhere to the term social impact, and its measurement (as in, e.g., Barraket & Yousefpour, Citation2013; Rawhouser et al., Citation2019; van Rijn et al., Citation2021), rather than creating further nomenclature controversy. With regard to the definition, an emerging agreement from our study is that social impact in this context refers to the outcomes that emanate from RSEs’ interventions. Although most of the included studies in this SLR do not measure negative or unintended outcomes, in defining social impact, RSE studies should recognize that social impacts can be intended/unintended as well as positive/negative (e.g., Nicholls, Citation2018; OECD, Citation2021; Pärenson, Citation2011; Vanclay, Citation2003).

Table 2. Terminology, definition and measurement of RSEs’ social impacts.

4.4. Measurement of RSEs’ social impact

4.4.1. Independent and dependent variables

In the absence of studies’ explicit classification of variables employed in their analyses, we categorized them as independent and dependent. The independent variable common to all the 21 studies was participation in (including membership/beneficiary of) the RSE. The dependent variable (social impact) varied ().

4.4.2. Attribution and causal inference

Rigorous measurement of social impacts of RSEs satisfies key methodological issues such as the use of a comparison/counterfactual and selection bias to attribute the social impacts to the RSEs. This can be achieved with both theory-based (e.g., PT and CT), quantitative (e.g., PSM) and DiD approaches. Thirteen qualitative studies in our sample do not use any comparison group nor a rigorous theory-based technique (that attributes social impacts to the RSE) when measuring the social impacts of RSEs. For the eight quantitative and mixed method studies, only three employ a comparison and two of these apply a technique to enable causal inference ().

4.4.3. Variables measured

We summarize studies’ measurement of activities, outputs, outcomes or impacts (see Table A5 in Appendix A in the supplemental data online for details). The most commonly studied social impact (17 studies) is poverty reduction in terms of well-being/livelihoods improvement. The identified overall sign of impact of the RSEs was positive in 17 studies. Two report mixed results and the remaining show no, or minimal, social impacts. The operational level at which social impacts are measured is uniform across studies, with 20 measuring social impacts at project/programme level while one combined many RSEs and analysed their impacts at organizational level. This kind of analysis masked detailed social impacts from different projects within the RSE studied. Notably, just one study attempted rigorously to measure social impacts following all the considerations for social impact measurement already described, while the remaining 20 reported a mixture of activities, outputs and outcomes ().

5. DISCUSSION AND IMPLICATIONS FOR FUTURE RESEARCH

As the first, to the authors’ knowledge, SLR oriented to regional/rural development-focused social entrepreneurial interventions’ social impact measurement, this study suggests that this scholarship is at an emerging stage. Further, we identify the need for conceptual clarity specifically in definition and in alignment with regional/rural studies and identification of approaches to enable rigorous social impact measurement. These approaches could contribute to clarity in the conceptual/underpinning of RSE social impact studies and provide reliable social impact measures essential for understanding and improving the effectiveness of regional/rural oriented interventions thus improving the practice besides stimulating appropriate research to progress regional/rural development research (Harrison et al., Citation2019) in the efforts of unravelling and reducing spatial disparities in welfare (Martin, Citation2021).

5.1. Social impact measurement in the context of rural studies

A substantial number of studies in this SLR employ theories/concepts to situate and structure their findings for conceptual clarity. A variety of theories or concepts are employed. This finding concurs with received SLRs on social entrepreneurship (e.g., Bozhikin et al., Citation2019; Gupta et al., Citation2020; van Twuijver et al., Citation2020). The finding that such a variety of theories or concepts are observed across a relatively small number of studies (21) is a further indication of the emergent nature of rural social entrepreneurship and more generally the social entrepreneurship discipline (Short et al., Citation2009). This study also identifies a number of RSE impact studies that do not explicitly employ a theory or key concept in which the research was anchored, which concurs with van Twuijver et al.’s (Citation2020) SLR in European RSE studies which concludes that the theoretical lens of most studies in their SLR was not explicit. This result poses concerns about the rigour of some existing RSE studies, and progress towards the emergence of a distinct discipline. We argue that rural social entrepreneurship studies should indeed be anchored explicitly in a relevant theory/concept.

Despite the reported inconsistency in definition of RSEs’ social impacts, we identify an emerging definitional pattern that relates to livelihoods and well-being outcomes of the RSE target stakeholders. This strongly relates to RSEs’ overall goal: to improve the well-being/livelihoods of rural communities. We propose that this definition includes positive, negative, intended and unintended consequences of the RSEs’ interventions (e.g., Nicholls, Citation2018; OECD, Citation2021; Vanclay, Citation2003). Additionally, we suggest that RSE studies could also be anchored/situated in an overarching framework that is linked to regional and rural development, e.g., the rural livelihoods/sustainable livelihoods framework (DfID, Citation1999; Scoones, Citation2015). Further rationalization could lead to a heuristic framework that integrates social impact measurement with rural livelihoods.

5.2. Level at which social impacts are measured

It is vital to choose the level (intervention/project, organization or programme) at which to measure the social impacts of regional/rural development focused actions. For RSE practitioners and policymakers, the appropriate level is determined by the purpose of the analysis and the audience. However, all stakeholders in social impact measurement make rational decisions based on the resources available for data collection, analysis and reporting. As most (R)SEs are resource poor and do not prioritize social impact measurement (e.g., Barraket & Yousefpour, Citation2013; OECD, Citation2015; Siqueira et al., Citation2021), this consideration becomes even more important.

In most of our RSE sample studies, data collection/analysis of social impact is at project/programme level. This is vital because a RSE is in most cases involved in a variety of projects or programmes and measurement of social impact needs to consider the social impacts stemming from each. The project or programme level of measurement enables attribution (e.g., Kabeer & Sulaiman, Citation2015; Salazar et al., Citation2012). Its management advantage is its identification of project or programme-specific effects (both intended and unintended) at beneficiaries’ or clients’ levels, and this would enhance the operation of the SE to achieve its social mission which is the core reason for social impact measurement (OECD, Citation2015).

5.3. Selection of social impacts to measure

Selection first requires clarity on the conceptual basis of social impact and its alignment with the underpinnings of rural studies (see section 5.1 above). Second, it achieves clarity by the use of a ToC/logic model (Ebrahim, Citation2020; OECD, Citation2021, cited in Hertel et al., Citation2020; Wry & Haugh, Citation2018), which establishes linkages amongst five basic components (input, activities, outputs, outcomes and impact) of an intervention (OECD, Citation2021; Hertel et al., Citation2020; Wry & Haugh, Citation2018), and provides a basis for attribution.

We detect many dependent variables as measures of social impact. This creates difficulties in comparison of social impacts across sectors or contexts. Opportunities for improvement lie in measurement in similar contexts (such as rural settings), and the use of social impact variables that are indirect measures of human development or welfare (Salazar et al., Citation2012). Indicators drawn from the GRI contain appealing general and sector-specific indicators (GRI, Citation2021), as one example. The additional application of the ToC/logic model and the rural livelihoods framework would create an opportunity for comparison of social impacts. This would be strengthened by application of multidimensional indices, for example, multidimensional poverty index (Alkire & Santos, Citation2013) and Hertel et al.’s (Citation2020) civic wealth index.

5.4. The measurement of social impacts

Because most of our sample’s studies are from business and management, they lean towards management research (Wry & Haugh, Citation2018). One study in our sample (Kabeer & Sulaiman, Citation2015) applies the logic model/ToC and attribution by way of a comparison group and PSM), exemplifying the feasibility of a mixed method approach. However, purely quantitative and qualitative approaches can also be applied in RSEs’ social impact measurement. Realist evaluation, which is a qualitative approach that involves identifying CMO was applied by a few of the studies in our SLR. Other qualitative techniques that can be applied to increase the rigour of social impact measurement, such as PT and CA, need to be applied together with a ToC/logic model to describe concisely the RSEs’ causal chain.

RSEs are involved in development through implementing particular interventions/programmes with targeted clients/beneficiaries (e.g., Cieslik, Citation2016; Kabeer & Sulaiman, Citation2015). In practice this introduces selection bias, and dealing with this requires random assignment of beneficiaries (treatment) to the interventions (Abadie & Cattaneo, Citation2018; Kabeer & Sulaiman, Citation2015; Vinod & Chindarkar, Citation2019). Rigorous social impact measurement also requires consideration of: (1) a comparison/control group to be compared with the treatment; and (2) a counterfactual (Abadie & Cattaneo, Citation2018; Kabeer & Sulaiman, Citation2015; Vinod & Chindarkar, Citation2019). Table A6 in Appendix A in the supplemental data online summarizes these identified key issues and suggests ways they can be dealt with.

6. CONTRIBUTION AND CONCLUSIONS

We respond to Harrison et al.’s (Citation2019, p. 136) call for regional studies’ ‘approaches that, in combination, result in the pushing on (by creating), pushing off (by consolidating), pushing back (by critiquing) and pushing forward (by collectively constructing) the field’ by focussing on the ‘local and regional development perspective’ theme. Specifically, we ‘push back’ by critiquing RSE studies that have measured social impacts and identifying concepts/theories and methods which have been applied. We ‘push forward’ by suggesting a mix of approaches for social impact measurement suitable for (1) RSE practitioners and managers, (2) policymakers and (3) future researchers. In achieving these aims, we also contribute to ‘a progressive and melioristic regional studies’ agenda as called for by Martin (Citation2021, p. 154) in order ‘to articulate an unassailable case for reducing spatial disparities in incomes, employment opportunities, health, education, housing, productivity, and well-being’ to achieve rural development.

Owing to the variation found in definitions of social impact and many variables used as indicators for its measurement in RSEs, we advocate the application of existing frameworks, such as the rural livelihoods framework, in the definition and classification of social impacts. We also advocate use of social impact measures related to human development/welfare, possibly drawing relevant indicators from the GRI, and the use of multidimensional construct measures. These steps contribute to comparability of results, both for practitioners and in the context of future quantitative meta-analyses.

Our review has also revealed minimal use of rigorous measurement methods for RSEs’ social impact. This constrains the extent to which objective analysis can proceed towards verifiable results with attribution to RSEs. Moreover, the mostly positive narratives of social impact could be rendered anecdotal. To measure effectively social impacts of RSEs, we advocate the use of a mixed method approach involving the RSEs’ ToC/logic model, and techniques (e.g., PSM) that enable attribution of social impacts to the RSEs. Rigorous theory-based impact evaluation methods such as PT and CT with the ToC/logic model could also be applied in cases of purely qualitative studies.

We find that empirical social impact measurement has been conducted primarily at project/programme level, and this offers opportunities to reduce ambiguity, and advance identification of project/programme-specific social impacts of the RSEs. At both design and implementation stages, this could lead to the improvement of the RSEs’ design and operation and thus contribute to regional/rural development.

The application of methods we suggest in this study introduces analytic rigour and enables attribution of the social impacts to RSEs. Without the use of rigorous social impact measurement methods, the resulting impacts could easily be rendered anecdotal and thus impede proper understanding and legitimizing RSEs as key partners within rural development besides missing opportunities that such findings could offer to relevant stakeholders e.g., policymakers, supporters, practitioners and researchers in the efforts of improving the effectiveness of such organizations for achieving rural development objectives. Most of the approaches described in this study are mostly from development and economics. Thus, given the emerging nature of social impact evaluation studies of social entrepreneurial organizations in the regional/rural context, practitioners, policymakers and researchers interested in rigorous social impact measurement should borrow from such fields because much can be gained from the application of diverse analytical approaches that have the potential to illuminate each other cumulatively for the advancement of sound and dependable knowledge i.e., theory and practice in this case on the social impacts of social entrepreneurial organizations particularly RSEs and other related interventions within rural development.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (57.4 KB)DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Social entrepreneurship still lacks a universally accepted definition of SEs (Morris et al., Citation2020), and consequently of RSEs. Based on the emerging rural social entrepreneurship literature (Musinguzi et al., Citation2022b; Steiner & Teasdale, Citation2019; van Twuijver et al., Citation2020), in this paper RSEs are defined as ‘organisations/enterprises with a social mission/goal of improving the well-being/creating positive social change for rural communities in form of social impacts achieved through the use of entrepreneurial/market based approaches’.

2 See https://ruralsehub.net/.

3 Databases searched include Web of Science, Scopus, ProQuest, EBSCO, JSTOR, Cambridge Core, Gale, Informit, Oxford Journals, Taylor & Francis, Wiley Online library, Science Direct, Business Source Complete, Emerald Insight and rural science/development (CAB abstracts). We exclude Google Scholar as a database for our SLR because it might not be reproducible (Kraus et al., Citation2020).

4 An example of a typical search string using a combination of key words from ProQuest is: ‘social enterprise’ AND impacts AND (Rural develop*) AND (at.exact (‘Article’) AND la.exact (‘ENG’) AND pd (19870112-20190331) AND PEER (yes)) AND pd (>19870101).

5 For studies that did not clearly state their geographic focus, we contacted authors for clarification.

REFERENCES

- Abadie, A., & Cattaneo, M. D. (2018). Econometric methods for program evaluation. Annual Review of Economics, 10(1), 465–503. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-economics-080217-053402

- Adams, T., Ripley, M., & Speyer, A. (2017, August 14). At the heart of impact measurement, listening to customers. Stanford social innovation review. https://ssir.org/articles/entry/at_the_heart_of_impact_measurement_listening_to_customers

- Aliaga-Isla, R., & Huybrechts, B. (2018). From ‘push out’ to ‘pull in’ together: An analysis of social entrepreneurship definitions in the academic field. Journal of Cleaner Production, 205, 645–660. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.09.133

- Alkire, S., & Santos, M. E. (2013). A multidimensional approach: Poverty measurement & beyond. Social Indicators Research, 112, 239–257, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-013-0257-3

- Amin, A., Cameron, A., & Hudson, R. (2002). Placing the social economy. Routledge. http://dro.dur.ac.uk/2832/

- Arena, M., Azzone, G., & Bengo, I. (2015). Performance measurement for social enterprises. VOLUNTAS: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations, 26(2), 649–672. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11266-013-9436-8

- Bagnoli, L., & Megali, C. (2011). Measuring performance in social enterprises. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 40(1), 149–165. https://doi.org/10.1177/0899764009351111

- Bansal, S., Garg, I., Sharma, G., Bansal, S., Garg, I., & Sharma, G. D. (2019). Social entrepreneurship as a path for social change and driver of sustainable development: A systematic review and research agenda. Sustainability, 11(4), 1091. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11041091

- Barnett, M. L., Henriques, I., & Husted, B. W. (2020). Beyond good intentions: Designing CSR initiatives for greater social impact. Journal of Management, 46, 937–964. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206319900539

- Barraket, J., & Anderson, H. (2010). Developing strong social enterprises: A documentary approach (No. CPNS 52). Australia: Brisbane.

- Barraket, J., & Yousefpour, N. (2013). Evaluation and social impact measurement amongst small to medium social enterprises: Process. Australian Journal of Public Administration, 72(4), 447–458. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8500.12042

- Barstow, C. K., Nagel, C. L., Clasen, T. F., & Thomas, E. A. (2016). Process evaluation and assessment of use of a large scale water filter and cookstove program in Rwanda. BMC Public Health, 16(1), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-016-3237-0

- Befani, B., & Mayne, J. (2014). Process tracing and contribution analysis: A combined approach to generative causal inference for impact evaluation. IDS Bulletin, 45, 17–36, https://doi.org/10.1111/1759-5436.12110

- Belcher, B., & Palenberg, M. (2018). Outcomes and impacts of development interventions. American Journal of Evaluation, 39(4), 478–495. https://doi.org/10.1177/1098214018765698

- BetterEvaluation. (2016). Qualitative impact assessment protocol (QUIP). http://www.betterevaluation.org/pl/node/5200 (accessed 10.4.17).

- Bonny, B. P., & Rajendran, P. (2013). Evaluation of self help groups (SHG) as a social enterprise for women empowerment. Journal of tropical agriculture, 51, 60–65. http://jtropag.kau.in/index.php/ojs2/article/view/282/282

- Bozhikin, I., Macke, J., & da Costa, L. F. (2019). The role of government and key non-state actors in social entrepreneurship: A systematic literature review. Journal of Cleaner Production, 226, 730–747. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2019.04.076

- Breau, S., & Saillant, R. (2016). Regional income disparities in Canada: Exploring the geographical dimensions of an old debate. Regional Studies, Regional Science, 3, 463–481. https://doi.org/10.1080/21681376.2016.1244774

- Bruin, A. d., & Teasdale, S. (2019). Exploring the terrain of social entrepreneurship: New directions, paths less travelled. In d. B. Anne, & T. Simon (Eds.), A Research Agenda for Social Entrepreneurship (pp. 200). Edward Elgar Publishing Ltd.

- Buratti, N., Sillig, C., & Albanese, M. (2022). Community enterprise, community entrepreneurship and local development: A literature review on three decades of empirical studies and theorizations. Entrepreneurship & Regional Development, 34, 1–26. https://doi.org/10.1080/08985626.2022.2047797

- Butler, A., & Lobley, M. (2016). Training as a social purpose: Are economic and social benefits delivered? International Journal of Training and Development, 20(4), 249–261. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijtd.12086

- Caló, F., Roy, M. J., Donaldson, C., Teasdale, S., & Baglioni, S. (2019). Exploring the contribution of social enterprise to health and social care: A realist evaluation. Social Science & Medicine, 222, 154–161. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2019.01.007

- Caló, F., Roy, M. J., Donaldson, C., Teasdale, S., & Baglioni, S. (2021). Evidencing the contribution of social enterprise to health and social care: Approaches and considerations. Social Enterprise Journal, 17(1), 140–155. https://doi.org/10.1108/SEJ-11-2020-0114

- Cavanaugh, A., & Breau, S. (2017). Locating geographies of inequality: Publication trends across OECD countries. Regional Studies, 52(9), 1225–1236. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2017.1371292

- Chandra, Y. (2018). New narratives of development work? Making sense of social entrepreneurs’ development narratives across time and economies. World Development, 107, 306–326. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.WORLDDEV.2018.02.033

- Cieslik, K. (2016). Moral economy meets social enterprise community-based green energy project in rural Burundi. World Development, 83, 12–26. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2016.03.009

- Clark, C., Emerson, J., & Thornley, B. (2014). The impact investor : lessons in leadership and strategy for collaborative capitalism. Wiley.

- Clark, H., & Anderson, A. A. (2004). Theories of change and logic models: telling them apart.

- Cooke, A., Smith, D., & Booth, A. (2012). Beyond PICO: The SPIDER tool for qualitative evidence synthesis. Qualitative Health Research, 22(10), 1435–1443. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732312452938

- Dart, R. (2004). The legitimacy of social enterprise. Nonprofit Management and Leadership, 14(4), 411–424. https://doi.org/10.1002/nml.43

- Davies, I. A., Haugh, H., & Chambers, L. (2019). Barriers to social enterprise growth. Journal of Small Business Management, 57(4), 1616–1636. https://doi.org/10.1111/jsbm.12429

- Dees, M. J. G., Nash, B. A., Kalafatas, J., Tolman, R., Wendy, K., Bloom, P., & McGrath, A. (2008). Developing the field of social entrepreneurship.

- Delahais, T., & Toulemonde, J. (2012). Applying contribution analysis: Lessons from five years of practice. Evaluation, 18(3), 281–293. https://doi.org/10.1177/1356389012450810

- Denyer, D., & Tranfield, D. (2009). Producing a systematic review. In D. Buchanan, & A. Bryman (Eds.), The SAGE handbook of organizational research methods (pp. 671–689). SAGE Publ.

- Dey, P., & Steyaert, C. (2012). Social entrepreneurship: Critique and the radical enactment of the social. Social Enterprise Journal, 8(2), 90–107. https://doi.org/10.1108/17508611211252828

- DfID, U. K. (1999). Sustainable livelihoods guidance sheets. DFID.

- Duflo, E., Glennerster, R., & Kremer, M. (2008). Using randomization in development economics research: A toolkit, in: Handbook of development economics (pp. 3895–3962). Elsevier.

- Ebrahim, A. (2020). Measuring social change. Stanford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1515/9781503609211

- Eversole, R., Barraket, J., & Luke, B. (2014). Social enterprises in rural community development. Community Development Journal, 49(2), 245–261. https://doi.org/10.1093/cdj/bst030

- Farmer, J., De Cotta, T., McKinnon, K., Barraket, J., Munoz, S.-A., Douglas, H., & Roy, M. J. (2016). Social enterprise and wellbeing in community life. Social Enterprise Journal, 12(2), 235–254. https://doi.org/10.1108/sej-05-2016-0017

- Franzidis, A. (2018). An examination of a social tourism business in Granada. Tourism Review, 74(6), 1179–1190. https://doi.org/10.1108/TR-04-2017-0076

- GRI. (2021). Global Reporting Initiative Standards Download Center. https://www.globalreporting.org/standards/gri-standards-download-center/.

- Grieco, C. (2015). Assessing social impact of social enterprises: Does one size really fit all? Springer Briefs in Business, 1–111. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-15314-8

- Gupta, P., Chauhan, S., Paul, J., & Jaiswal, M. P. (2020). Social entrepreneurship research: A review and future research agenda. Journal of Business Research, 113, 209–229. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2020.03.032

- Harrison, J., Delgado, M., Derudder, B., Anguelovski, I., Montero, S., Bailey, D., & Propris, L. D. (2019). Pushing regional studies beyond its borders. Regional Studies, 54(1), 129–139. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2019.1672146

- Haugh, H. (2012). The importance of theory in social enterprise research. Social Enterprise Journal, 8(1), 7–15. https://doi.org/10.1108/17508611211226557

- Hertel, C., Bacq, S., & L, G. T. (2020). Social performance and social impact in the context of social enterprises – A holistic perspective. In V. Antonino, & R. Tommaso (Eds.), Handbook of social innovation and social enterprises (pp. 137–172). Springer. https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-030-96596-9_7

- Heyvaert, M., Hannes, K., Maes, B., & Onghena, P. (2013). Critical appraisal of mixed methods studies. Journal of Mixed Methods Research, 7(4), 302–327. https://doi.org/10.1177/1558689813479449

- Holt, D., & Littlewood, D. (2015). Identifying, mapping, and monitoring the impact of hybrid firms. California Management Review, 57(3), 107–125. https://doi.org/10.1525/cmr.2015.57.3.107

- Horlings, L. G. (2015). Values in place; A value-oriented approach toward sustainable place-shaping. Regional Studies, Regional Science, 2, 257–274. https://doi.org/10.1080/21681376.2015.1014062

- Irene, B., Marika, A., Giovanni, A., & Mario, C. (2016). Indicators and metrics for social business: A review of current approaches. Journal of Social Entrepreneurship, 7, 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1080/19420676.2015.1049286

- Kabeer, N., & Sulaiman, M. (2015). Assessing the impact of social mobilization: Nijera Kori and the construction of collective capabilities in rural Bangladesh. Journal of Human Development and Capabilities, 16(1), 47–68. https://doi.org/10.1080/19452829.2014.956707

- Khandker, S. R., Koolwal, G. B., & Samad, H. A. (2010). Handbook on impact evaluation: Quantitative methods and practices. World Bank. © World Bank. https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/2693 License: CC BY 3.0 IGO.

- Kraus, S., Breier, M., & Dasí-Rodríguez, S. (2020). The art of crafting a systematic literature review in entrepreneurship research. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 16(3), 1023–1042. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11365-020-00635-4

- Krupoderova, A., & Portnov, B. A. (2020). Eco-innovations and economic performance of regions: A systematic literature survey. Regional Studies, Regional Science, 7, 571–588. https://doi.org/10.1080/21681376.2020.1848613

- Laeis, G. C. M., & Lemke, S. (2016). Social entrepreneurship in tourism: Applying sustainable livelihoods approaches. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 28(6), 1076–1093. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCHM-05-2014-0235

- Lapeyre, R. (2010). Community-based tourism as a sustainable solution to maximise impacts locally? The Tsiseb conservancy case, Namibia. Development Southern Africa, 27(5), 757–772. https://doi.org/10.1080/0376835X.2010.522837

- Leeuwen, E. v. (2019). The rural and peripheral in regional development: An alternative perspective. Regional Studies, 53(6), 924–925. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2019.1580978

- Lyon, F. (2009). Measuring the value of social and community impact. In P. Hunter (Ed.), Social enterprise for public service: How does the third sector deliver? (pp. 1–100). The Smith Institute.

- Martin, R. (2021). Rebuilding the economy from the COVID crisis: Time to rethink regional studies? Regional Studies, Regional Science, 8, 143–161. https://doi.org/10.1080/21681376.2021.1919191

- Masukujjaman, M., Siwar, C., Alam, S. S., & Halim, S. A. (2016). Does social business link with the sustainable livelihoods of rural households?: Lessons from Bangladesh. The Journal of Developing Areas, 50(5), 403–413. https://doi.org/10.1353/jda.2016.0031

- Mayne, J. (2001). Evaluating the complex: Attribution, contribution and beyond. Mita Marra: Google Bøger.

- McCreless, M., & Trelstad, B.. (2012). A GPS for social impact. Stanford social innovation review. https://ssir.org/articles/entry/a_gps_for_social_impact#

- McKague, K., & Tinsley, S. (2012). Bangladesh’s rural sales program. Social Enterprise Journal, 8(1), 16–30. https://doi.org/10.1108/17508611211226566

- Mohanan, M., Babiarz, K. S., Goldhaber-Fiebert, J. D., Miller, G., & Vera-Hernández, M. (2016). Effect of a large-scale social franchising and telemedicine program on childhood diarrhea and pneumonia outcomes in India. Health Affairs, 35(10), 1800–1809. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2016.0481

- Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., & Altman, D. G. (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. Annals of Internal Medicine, 151(4), 264. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-151-4-200908180-00135

- Molecke, G., & Pinkse, J. (2020). Justifying social impact as a form of impression management: Legitimacy judgements of social enterprises’ impact accounts. British Journal of Management, 31(2), 387–402. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8551.12397

- Morris, M. H., Santos, S. C., & Kuratko, D. F. (2020). The great divides in social entrepreneurship and where they lead us. Small Business Economics 57, 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-020-00318-y

- Muñoz, S.-A. (2010). Towards a geographical research agenda for social enterprise. Area, 42, 302–312. http://www.jstor.org/stable/40890884

- Munoz, S.-A., Farmer, J., Winterton, R., & Barraket, J. (2015). The social enterprise as a space of well-being: An exploratory case study. Social Enterprise Journal, 11(3), 281–302. https://doi.org/10.1108/sej-11-2014-0041

- Musinguzi, P., Baker, D., Larder, N., & Villano, R. A. (2023). Critical success factors of rural social enterprises: Insights from a developing country context. Journal of Social Entrepreneurship, 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1080/19420676.2022.2162108

- Musinguzi, P., Larder, N., & Baker, D. (2022a). Social enterprises as a revitalization strategy for rural communities. In N. Walzer, & C. Merrett (Eds.), Rural areas in transition: Meeting challenges & making opportunities (pp. 127–148). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003280620-7

- Musinguzi, P., Larder, N., & Baker, D. (2022). Social enterprises as a revitalization strategy for rural communities. In N. Walzer & C. Merrett (Eds.), Rural areas in transition: Meeting challenges & making opportunities (1st ed., pp. 127–148). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003280620-7

- Musinguzi, P., Villano, R. A., & Baker, D. (2022b). Social enterprise performance measurement using a diversity and inclusion approach: Implications for equitable and inclusive smallholder farmers’ improved wellbeing. In S. Dhakal, R. Cameron, & J. Burgess (Eds.), A field guide to managing diversity, equality and inclusion in organisations (pp. 266–278). Edward Elgar Publishing. https://www.elgaronline.com/view/book/9781800379008/book-part-9781800379008-31.xml.

- Nguyen, L., Szkudlarek, B., & Seymour, R. G. (2015). Social impact measurement in social enterprises: An interdependence perspective. Canadian Journal of Administrative Sciences/Revue Canadienne des Sciences de L’Administration, 32(4), 224–237. https://doi.org/10.1002/cjas.1359

- Nicholls, A. (2018). A general theory of social impact accounting: Materiality, uncertainty and empowerment. Journal of Social Entrepreneurship, 9, 132–153. https://doi.org/10.1080/19420676.2018.1452785

- Norris, L. (2020). The spatial implications of rural business digitalization: Case studies from Wales. Regional Studies, Regional Science, 7, 499–510. https://doi.org/10.1080/21681376.2020.1841674

- OECD. (2021). Social impact measurement for the Social and Solidarity Economy: OECD Global Action Promoting Social and Solidarity Economy Ecosystems (2021/05; OECD Local Economic and Employment Development (LEED) Papers). OECD Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1787/d20a57ac-en

- Olmedo, L., & O’Shaughnessy, M. (2022). Community-based social enterprises as actors for neo-endogenous rural development: A multi-stakeholder approach⋆. Rural Sociology, 0, 1–28. https://doi.org/10.1111/RUSO.12462

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). (2015). Social entrepreneurship: Social impact measurement for social enterprises (No. 10). https://doi.org/10.1787/5jrtpbx7tw37-en.

- Ormiston, J. (2019). Blending practice worlds: Impact assessment as a transdisciplinary practice. Business Ethics: A European Review, 28(4), 423–440. https://doi.org/10.1111/beer.12230

- Ormiston, J. (2022). Why social enterprises resist or collectively improve impact assessment: The role of prior organizational experience and ‘impact lock-in’. Business & Society, 000765032211205. https://doi.org/10.1177/00076503221120568

- O’Shaughnessy, M., Casey, E., & Enright, P. (2011). Rural transport in peripheral rural areas. Social Enterprise Journal, 7(2), 183–190. https://doi.org/10.1108/17508611111156637

- O’Shaughnessy, M., Christmann, G., & Richter, R. (2022). Introduction. Dynamics of social innovations in rural communities. Journal of Rural Studies, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2022.09.010

- Pärenson, T. (2011). The criteria for a solid impact evaluation in social entrepreneurship. Society and Business Review, 6(1), 39–48. https://doi.org/10.1108/17465681111105823

- Peattie, K., & Morley, A. (2008). Eight paradoxes of the social enterprise research agenda. Social Enterprise Journal, 4(2), 91–107. https://doi.org/10.1108/17508610810901995

- Penna, R. M. (2011). The nonprofit outcomes toolbox : a complete guide to program effectiveness, performance measurement, and results. Wiley.

- Persaud, A., & Bayon, C. M. (2019). A review and analysis of the thematic structure of social entrepreneurship research: 1990–2018. International Review of Entrepreneurship, 17, 495–528. ISSN 2009-2822.

- Phillips, W., Lee, H., Ghobadian, A., O’Regan, N., & James, P. (2015). Social innovation and social entrepreneurship. Group & Organization Management, 40, 428–461. https://doi.org/10.1177/1059601114560063

- Pike, A., Rodríguez-Pose, A., & Tomaney, J. (2010). What kind of local and regional development and for whom? Regional Studies, 41(9), 1253–1269. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343400701543355

- Pless, N. M., & Appel, J. (2012). In pursuit of dignity and social justice: Changing lives through 100% inclusion – How Gram Vikas fosters sustainable rural development. Journal of Business Ethics, 111(3), 389–411. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-012-1415-2

- Punton, M., & Welle, K. (2015a). Straws-in-the-wind, hoops and smoking guns: What can process tracing offer to impact evaluation? Brighton.

- Punton, M., & Welle, K. (2015b). Applying process tracing in five steps. Brighton.

- Rawhouser, H., Cummings, M., & Newbert, S. L. (2019). Social impact measurement: Current approaches and future directions for social entrepreneurship research. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 43(1), 82–115. https://doi.org/10.1177/1042258717727718

- Roy, M. J., Donaldson, C., Baker, R., & Kerr, S. (2014). The potential of social enterprise to enhance health and well-being: A model and systematic review. Social Science & Medicine, 123, 182–193. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.07.031

- Saebi, T., Foss, N. J., & Linder, S. (2019). Social entrepreneurship research: Past achievements and future promises. Journal of Management, 45, 70–95. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206318793196

- Sakata, H., & Prideaux, B. (2013). An alternative approach to community-based ecotourism: A bottom-up locally initiated non-monetised project in Papua New Guinea. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 21(6), 880–899. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2012.756493

- Salazar, J., Husted, B. W., & Biehl, M. (2012). Thoughts on the evaluation of corporate social performance through projects. Journal of Business Ethics, 105(2), 175–186. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-011-0957-z

- Sarpong, D., & Davies, C. (2014). Managerial organizing practices and legitimacy seeking in social enterprises. Social Enterprise Journal, 10(1), 21–37. https://doi.org/10.1108/sej-05-2013-0019

- Scoones, I. (2015). Sustainable livelihoods and rural development. Practical Action Publ.

- Short, J. C., Moss, T. W., & Lumpkin, G. T. (2009). Research in social entrepreneurship: Past contributions and future opportunities. Strategic Entrepreneurship Journal, 3(2), 161–194. https://doi.org/10.1002/sej.69

- Siqueira, E.H. da S., Bin, A., Stefanuto, R.C. (2021). Measuring impacts of social enterprises: Perspectives from Brazilians entrepreneurs and investors. Social Enterprise Journal, 17(4), 527–547. https://doi.org/10.1108/SEJ-10-2020-0086

- Slaper, T. F., & Hall, T. J. (2011). The triple bottom line: What is it and how does it work? Indiana Bus. Rev, 86, 1–10.

- So, I., & Staskevicius, A. (2015). Measuring the impact in impact investing. Harvard University Press.

- Spencer, R., Brueckner, M., Wise, G., & Marika, B. (2016). Australian Indigenous social enterprise: Measuring performance. Journal of Enterprising Communities: People and Places in the Global Economy, 10(4), 397–424. https://doi.org/10.1108/JEC-10-2015-0050

- Steiner, A., Farmer, J., & Bosworth, G. (2019). Rural social enterprise – Evidence to date, and a research agenda. Journal of Rural Studies, 70, 139–143. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2019.08.008

- Steiner, A., & Teasdale, S. (2019). Unlocking the potential of rural social enterprise. Journal of Rural Studies, 70, 144–154. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2017.12.021

- Stephan, U., & Drencheva, A. (2017). The person in social entrepreneurship. In A. Gorkan, C. Tomas, K. Bailey, & K. Tessa (Eds.), The Wiley handbook of entrepreneurship (pp. 205–229). John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118970812.ch10

- Suchowerska, R., Barraket, J., Qian, J., Mason, C., Farmer, J., Carey, G., Campbell, P., & Joyce, A. (2019). An organizational approach to understanding How social enterprises address health inequities: A scoping review. Journal of Social Entrepreneurship 11, 1–25. https://doi.org/10.1080/19420676.2019.1640771

- Tan, L. P., Le, A. N. H., & Xuan, L. P. (2019). A systematic literature review on social entrepreneurial intention. Journal of Social Entrepreneurship, 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/19420676.2019.1640770

- Thananusak, T. (2019). Science mapping of the knowledge base on sustainable entrepreneurship, 1996–2019. Sustainability, 11(13), 3565. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11133565

- Tobias, J. M., Mair, J., & Barbosa-Leiker, C. (2013). Toward a theory of transformative entrepreneuring: Poverty reduction and conflict resolution in Rwanda’s entrepreneurial coffee sector. Journal of Business Venturing, 28(6), 728–742. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JBUSVENT.2013.03.003

- Torri, M. C. (2010). Community-based enterprises: A promising basis towards an alternative entrepreneurial model for sustainability enhancing livelihoods and promoting socio-economic development in rural India. Journal of Small Business & Entrepreneurship, 23(2), 237–248. https://doi.org/10.1080/08276331.2010.10593484

- Trampusch, C., & Palier, B. (2016). Between X and Y: How process tracing contributes to opening the black box of causality. New Political Economy, 21(5), 437–454. https://doi.org/10.1080/13563467.2015.1134465

- Tranfield, D., Denyer, D., & Smart, P. (2003). Towards a methodology for developing evidence-informed management knowledge by means of systematic review. British Journal of Management, 14(3), 207–222. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8551.00375

- Vanclay, F. (2003). International principles For social impact assessment. Impact Assessment and Project Appraisal, 21(1), 5–12. https://doi.org/10.3152/147154603781766491

- van Lunenburg, M., Geuijen, K., & Meijer, A. (2020). How and Why Do social and sustainable initiatives scale? VOLUNTAS: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations 31, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11266-020-00208-7

- van Rijn, M., Raab, J., Roosma, F., & Achterberg, P. (2021). To prove and improve: An empirical study on why social entrepreneurs measure their social impact. Journal of Social Entrepreneurship, 0, 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1080/19420676.2021.1975797

- van Twuijver, M. W., Olmedo, L., O’Shaughnessy, M., & Hennessy, T. (2020). Rural social enterprises in Europe: A systematic literature review. Local Economy: The Journal of the Local Economy Policy Unit, 35(2), 121–142. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269094220907024

- Vázquez-Maguirre, M., Portales, L., & Velásquez Bellido, I. (2018). Indigenous social enterprises as drivers of sustainable development: Insights from Mexico and Peru. Critical Sociology, 44(2), 323–340. https://doi.org/10.1177/0896920516688757

- Vázquez-Maguirre, M., Ruelas, G. C., & Torre, C. G. D. L. (2016). Women empowerment through social innovation in Indigenous social enterprises. RAM. Revista de Administração Mackenzie, 17(6), 164–190. https://doi.org/10.1590/1678-69712016/administracao.v17n6p164-190

- Venot, J. P. (2016). A success of some sort: Social enterprises and drip irrigation in the developing world. World Development, 79, 69–81. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2015.11.002

- Vinod, T., & Chindarkar, N. (2019). Evaluation, Economics, and Sustainable Development. Economic Evaluation of Sustainable Development, 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-13-6389-4_1

- Vo, A. T., & Christie, C. A. (2018). Where impact measurement meets evaluation: Tensions, challenges, and opportunities. American Journal of Evaluation, 39(3), 383–388. https://doi.org/10.1177/1098214018778813

- Ward, N., & Brown, D. L. (2009). Placing the rural in regional development. Regional Studies, 43(10), 1237–1244. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343400903234696

- Weerakoon, C. (2021). A decade of research published in the journal of social entrepreneurship: A review and a research agenda. Journal of Social Entrepreneurship, 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1080/19420676.2021.1968938

- World Bank. (2021). Rural population (% of total population). https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/sp.rur.totl.zs (accessed 6.22.21).

- Wry, T., & Haugh, H. (2018). Brace for impact: Uniting our diverse voices through a social impact frame. Journal of Business Venturing, 33(5), 566–574. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2018.04.010