ABSTRACT

This paper analyses different categories of legacy from socialist central planning policies (SCPP) for urban development. How have city-specific measures by SCPP affected local economic systems, and have there been long-term consequences for cities even after their return to a market economy? Drawing from case studies of four East German cities, we identify several types of socialist policy measures that determine the local economic performance up to now. The impact of some measures was primarily displayed via ‘soft’ factors such as local image and identity and the attitudes of residents, local decision-makers.

1. INTRODUCTION

Up to the rise of the ‘Iron Curtain’, during more than 40 years of socialism, politicians in central governments had tried to create new conditions for the economic development of cities and regions in Central and Eastern Europe. These conditions followed the logic of centralist planning and were based on the specific needs of socialist countries. They stemmed from the countries’ rejection of an international division of labour as well as from pure ideological ideas. The allocation of specific economic and political functions to certain cities was accompanied by shifting resources to those cities considered most relevant for the socialist economy (Sjöberg, Citation1999).

This paper focuses on the legacy of these measures for the present economic performance of post-socialist cities. Has socialist central planning policy (SCPP) created specific trajectories for cities which are still relevant today, more than 30 years after the return to a market economy? By answering this question, this paper contributes to the discussion about diverging development paths of post-socialist cities and to the international debate on the impact of history on cities and regions. Since the 1990s, scholars from regional and urban science have stressed the importance of historical accidents and path dependences (Arthur, Citation1994; Krugman, Citation1991) and aimed at developing an evolutionary approach towards regional economic growth in the context of a market economy (Martin & Sunley, Citation2006; Simmie, Citation2012). By looking at the most relevant categories of ‘treatment’ by SCPP for cities, we illustrate whether development measures by an autocratic regime may result in phenomena which are similar to the mechanisms discussed in the context of path dependence, especially the tendency of self-reinforcement.

Our study is based on a selection of cities in East Germany (the former German Democratic Republic – GDR) which played a significant role in the GDR economy and were prioritized for strategical and/or ideological reasons. They received massive investments and their economic, social and building structures were drastically transformed.

The paper is structured as follows. We next give an overview of the literature about the role of history for regional development and the regeneration of post-socialist cities. This is followed by a theoretical discussion on how different measures by SCPP may affect urban development. After presenting our empirical results, we discuss these findings and draw conclusions for the discussion on path dependence and future research.

2. LITERATURE REVIEW

2.1. The empirics of ‘history matters’

The seminal works of Paul A. David (David, Citation1985, Citation1994) and W. Brian Arthur (Arthur, Citation1989, Citation1994) spread the general idea of long-term feedbacks from historical events and path dependence. They have provoked a fruitful discussion and a steadily growing body of empirical literature emphasizing the historical determinants of regional economic growth. Although there is agreement about the general importance of history in the sense that ‘the past will strongly condition the range of possibilities that lie open in the future’ (Wolfe, Citation2010, p. 140), the literature considerably varies with regard to the concepts of history and path dependence as well as the empirical approaches. According to Henning et al. (Citation2013), we may distinguish between path dependence and past dependence. A crucial feature of path dependence is that a given structure of factors which has evolved in the past is shaping the current economic performance of a region and has a tendency to become reinforced. This is frequently due to increasing returns or network externalities (Pierson, Citation2000, Citation2003) and leads to a situation often described as lock-in (Henning et al., Citation2013). The concept of past dependence in contrast only refers to general effects of history on present situations, even if a reinforcing mechanism does not exist.

With regard to path dependence, empirical studies are focusing on the role of existing local or regional structures (which have developed through self-reinforcing mechanisms in the course of time) for specific types of reaction and for the grade of resilience of cities and regions towards different categories of change. Grabher (Citation1993) and Hudson (Citation1994) have shown for old industrial districts that structural change was hampered by existing industrial monostructures, the strong entanglement of regional decision-makers within several categories of networks and the resulting ignorance towards global economic shifts. Wolfe (Citation2010) shows that a city’s ability to respond to external shocks by innovative economic activities is strongly influenced by existing industrial structures, but other determinants such as a strong civic leadership are also important. Quite similar, by comparing case studies of regional shipbuilding and textile clusters in Germany and Korea, Hassink (Citation2010) concludes that the strength of path dependence can hardly be determined by the structure of an industry or the degree of local specialization alone. In each case a unique setting of institutional factors shaped the process of local path dependence.

Most studies that follow the approach of path dependence want to explain a certain present situation in a region by asking how this situation has evolved and why no alternative development path was chosen. Our intention is to examine SCPP measures as a special category of historical determinants and ask for their impact on local development at the present time. The literature quoted above is strongly focused on regional economies in capitalist countries. Hence, one could expect that path dependences and processes of self-reinforcement may only evolve within a free-market economy. Therefore, our general hypothesis is that special treatments by SCPP for selected cities will probably have an impact on the current situation of these cities in the sense of past dependence, but with our empirical explorations, we also aim to find evidence for mechanisms of self-reinforcement after the end of socialism.

2.2. Socialist legacies and the regeneration of post-socialist cities

The discussion on post-socialist cities is encompassing a great variety of topics, for example, research on different approaches of governance with regard to urban shrinkage (Rink et al., Citation2014; Runge et al., Citation2020) and diverging patterns of city planning in post-socialist cities (Tsenkova, Citation2014), or explanations for the lack of cooperation between post-socialist core cities and adjacent municipalities (Sagan, Citation2014). There is also some more general discussion whether former socialist cities may still be characterized by some typical features (Hirt, Citation2013) and whether post-socialist cities are ‘radically different’ from Western European cities (Grubbauer & Kusiak, Citation2012). But up to now, most contributions on the transformation of post-socialist cities are not explicitly focusing on the role of SCPP within this process. Although some relevant aspects of SCPP and the legacies from socialism have been discussed, there has been no comprehensive analysis, so far, of the long-term impact of SCPP on cities.

Some findings on the impact of SCPP for urban development are focusing on the built structures of cities; it is obvious that built structures from the time of socialism still have relevant impacts for cities which are ‘not about to vanish into thin air’ (Hirt, Citation2013, p. 36). For example, one feature of SCPP was to neglect housing stocks in traditional inner-city areas. After the end of socialism, these places were less attractive compared with newly developed suburban areas. Consequently, the process of urban shrinkage in many post-socialist cities was accompanied by a strong wave of residential suburbanization (Nuissl & Rink, Citation2005).

With regard to urban economic development, Golubchikov (Citation2006) has shown that the recent economic performance of cities within the region of Leningrad has been largely determined by their economic structures at the end of the Soviet era. In addition, Heider (Citation2019b) found that recent trajectories of urban population growth in East Germany are negatively correlated to population growth during socialism and interpreted this as evidence that SCPP were in general not sustainable in changing the long-term growth trajectories of cities.

3. THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK

Which means did SCPP use to change the economic situation of certain cities? We are not looking at general policies that affected all regions within the GDR, such as the nationalization of businesses, discrimination against entrepreneurship or the permanent presence of the intelligence service. Instead, we examine centrally planned place-specific treatments, following the strong ‘prioritization’ (Sjöberg, Citation1999) of certain industries and places. Building on Bröcker and Richter (Citation1999), four basic strategies of SCPP to change the development paths of cities can be identified: (1) large investments in existing industrial clusters; (2) the establishment of new industries in formerly rather undeveloped places; (3) changes in the administrative status of cities due to the restructuring of administrative territories; and (4) socialist urban renewal. The latter category involves measures to transform the land-use and built environment of cities according to the ideas of socialist urban planning. Such measures were implemented in more or less all East German cities, but they had a much larger scope in cities ‘prioritized’ by SCPP.

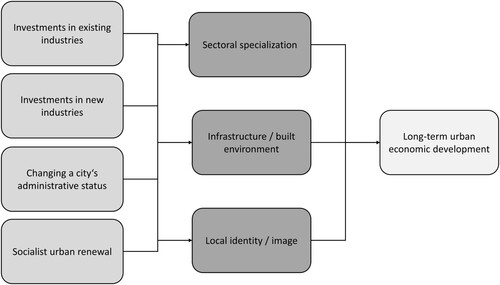

By which channels could those four categories of SCPP have affected the long-term economic performance of cities? According to the literature, there is a cornucopia of factors determining urban economic performance. The interplay of these factors is quite complex and researchers have developed numerous approaches to systematize those determinants (e.g., Storper, Citation2010). For our purpose we use a rather pragmatic approach and stick to three categories of determinants for urban economic growth which could have been affected by the aforementioned SCPP measures: (1) sectoral specialization; (2) infrastructure and the built environment; and (3) local image and identity. The causal relationships between SCPP measures, the three economic channels and long-term economic development are summarized in and will be discussed hereinafter.

Figure 1. Socialist central planning policies (SCPP) measures and channels of change within the urban economic system.

Source: Author’s illustration.

Sectoral specialization (which may have been supported by SCPP mainly through investments in existing or new industries) has often been considered as the core component of urban economic growth in market economies (Storper, Citation2010). Increasing the size of a local economic activity should yield positive agglomeration externalities (e.g., Duranton & Puga, Citation2004). However, especially in times of global economic change, a high level of specialization can result in regional lock-ins (Grabher, Citation1993), a high dependence on one or few industries and consequently economic decline in case of an external economic shock. If SCPP has supported sectoral specialization in a certain industry in a city where it was not possible to make use of the benefits described above, the industry in question could probably have been less productive than its competitors in Western countries and one could expect negative developments for the city in question after the return to a market economy.

The relationship between infrastructural endowments and local economic growth is well researched (e.g., Démurger, Citation2001; Cantos et al., Citation2005). Accessibility and the quality of infrastructure are obvious locational factors to attract businesses and citizens. In addition, the structure and visual appeal of the built environment might be important for a high quality of life for the local population and attracting new residents and tourists. Both infrastructural endowments and the built environment may have been affected by all four categories of SCPP measures. As infrastructural endowments and built environments may not be easily changed, the impact of SCPP in these fields will last in the long term.

Unlike the foregoing two channels affected by SCPP, local identity and image is more of a fuzzy category in relation to urban economic growth. Indeed, there are several ways how local identity can foster economic development. First, local identity can be linked to the concept of social capital (Putnam, Citation1993; Raagma, Citation2002). Strong identification with a city’s social and cultural structures might foster people’s incentive to participate in local networks and development processes and result in positive economic outcomes. Second, local identity can also be linked to the notion of ‘entrepreneurial culture’. Fritsch and Wyrwich (Citation2014, Citation2016) have shown that a rich entrepreneurial tradition of a region might stimulate long-term economic growth. Last, but not least, local identity is also relevant for the external perception or image of a city. Therefore, it serves as an important asset for ‘place branding’ strategies (Clifton, Citation2011; Cleave et al., Citation2016) and the attraction of tourists, investments and highly skilled and creative residents. All four categories of SCPP measures may have had an impact on local identity and the image of cities. Strong investments for a certain industry could lead to identify a city with the industry in question, for example, as to be a ‘steel city’. Changes in the administrative status of a city will always have an impact on the image of the city and on local identity. The same is true for measures of urban renewal which might have changed the perception of a city by its citizens and people from outside.

All three above-mentioned channels for SCPP measures are interrelated. Hence, each of the four measures may have affected more than one of those channels.

4. EMPIRICAL STRATEGY

This paper is based on case studies on four East German cities. The selection of cities followed our main research question: Had city-specific SCPP measures an impact on the economic development of cities even after their return to a market economy? We selected cities which had been affected by one or more of the four main SCPP support-measures, as described above and which showed diverging development paths after the end of socialism. This was done on the base of our background knowledge on regional and urban development patterns in East Germany, additional literature on the development of the East German urban system since 1945 (Berentsen, Citation1987; Bröcker & Richter, Citation1999) and discussions with experts from the Urban Economics Department at the Leibniz Institute for Economic Research in Halle (Saale).

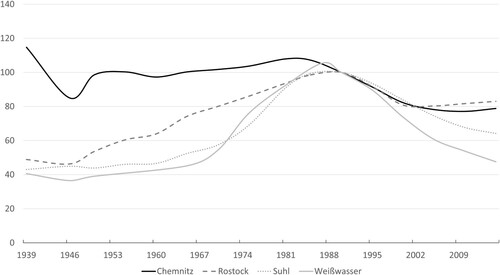

As a result, we selected two larger cities with a population today of around 200,000 residents,Footnote1 which after years of shrinkage have turned to a positive development (Chemnitz and Rostock) and two smaller cities with a strong population growth between 1946 and 1989, which have not been able to return to a growth of inhabitants (Suhl and Weißwasser) (). These development paths are quite representative for post-socialist urban development in East Germany. After a general period of urban population decline during the 1990s, some of the larger cities entered a phase of regrowth, while the majority of smaller cities is constantly shrinking (Haase et al., Citation2017; Heider, Citation2019b; Kauffmann, Citation2009). A comprehensive overview of the initial conditions in our case study cities (before socialism), the major SCPP measures, and the cities’ development since 1990 is provided in . The main trajectories of the cities will be described in the following discussion. The description is mainly based on our initial knowledge of the case study cities as well as the empirical findings, as presented in section 5.

Figure 2. Indexed population development of the case study cities before and after German reunification, 1939–2015.

Note: 1990 = 100%; population figures before 1990 refer to GDR municipal territories; population figures after 1990 refer to municipal territories of 2015.

Source: Authors’ illustration based on Federal Statistical Office Germany (2017) and Ministerrat der Deutschen Demokratischen Republik (1983).

Table 1. Synopsis of case study cities, their main characteristics and development paths.

Chemnitz is the largest city in the southern part of the state of Saxony (about 300,000 inhabitants in 1990). Since Chemnitz had always been an important industrial location, it received particular attention by SCPP. Its name was changed to Karl-Marx-Stadt, and the intention was to turn the city into a model socialist city. Until 1989 the city and its region played an important role as the GDR’s major industrial production site. After a relatively long period of deindustrialization and population shrinkage after 1990, Chemnitz can now be classified as a slowly growing city ().

Rostock is the largest city in the northern state of Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania and had around 250,000 inhabitants in 1990. It was the GDR’s most important port city and an international seaport. Massive investments were made in its infrastructure and fixed assets in the shipbuilding industry. Following a period of drastic shrinkage after 1990, the number of inhabitants in Rostock has seen a continuous increase in the last 15 years ().

Suhl is a small city in south-western Thuringia (about 54,000 inhabitants in 1990). It has a tradition of arms production and is also known for its construction of bicycles, motorcars and light motorcycles. Despite its small size, Suhl was chosen to be the capital of a GDR administrative region (‘Bezirksstadt’). In addition, electric household appliance manufacturing was moved to Suhl in the 1970s. After German reunification, the loss of the capital status, as well as the collapse of local industries, was accompanied by a quick decline in population. Today the city can be characterized as stagnating ().

Finally, Weißwasser is a small city (approximately 35,000 inhabitants in 1990) in north-eastern Saxony near the Polish border. During the first half of the 20th century the town had become an important location for the German glass industry due to natural resources in the surrounding areas. SCPP expanded the glass industry, making Weißwasser one of the most important glass-producing clusters in Europe. A second wave of industrialization resulted from the emergence of lignite mining and energy industry nearby, leading to a massive influx of workers. After German reunification, the glass industry vanished almost totally and the energy industry was massively downsized. Weißwasser became one of the most drastically shrinking cities in East Germany ().

To discover the impact of city-specific SCPP measures on the economic performance of the four cities since 1990, there is only very limited information in the form of statistical data or written documents. Therefore, we turned to conducting qualitative interviews with different categories of stakeholders. We are aware that this method involves several shortcomings. Some stakeholders from today may be too young to be correctly informed about the local development before and in the immediate aftermath of German reunification. This means that some statements will not be based on personal experience but more on the narratives about local development which prevail in a city. Statements by some stakeholders may be influenced by their special interests. To reduce these shortcomings, our group of interview partners includes a wide range of stakeholders: mayors, city councillors, representatives of local job agencies, business development agencies, business associations, heads of local museums and major local businesses as well as local scientists and journalists (see Appendix A in the online supplemental data).

We started the semi-structured interviews by asking the local experts for their views on the economic development and the most relevant changes in their city before and after 1990. Then, following our knowledge about city-specific SCPP measures, we asked for details about the scope and structure of these measures during the times of socialism. This was followed by questions regarding the present relevance of these measures and the channels by which the SCPP measures have – in the view of the interview partners – influenced (or are still influencing) the local economic situation. Between summer 2015 and winter 2017, a total of 33 interviews were conducted; the interviews lasted between one and two hours and took place in the professional premises of the interviewees. We took extensive notes during the interviews and subsequently wrote interview records which were analysed according to the theoretical framework presented in section 3.

5. EMPIRICAL RESULTS

5.1. Investments in existing industries

5.1.1. Implementation by the GDR regime

One crucial strategy of the GDR was to conglomerate and expand existing industrial clusters, which were prioritized by SCPP. All our case study cities were seats of the headquarters of important industrial conglomerates which formed out of the nationalization of existing firms. This includes the production of automotive parts, machine tools, household appliances and textile fabrics in Chemnitz, the shipping and shipbuilding and fishing industries in Rostock, the production of mopeds and guns in Suhl, and the glass industry in Weißwasser.

Chemnitz and Rostock are the most significant examples for this strategy. Since large proportions of the local production sites had been destroyed during the Second World War, and parts of the remaining machinery were shipped to the Soviet Union as reparation payments, high investments were needed to restore Chemnitz’s leading role in East German manufacturing. In contrast to other regions of the GDR, the nationalization of local firms was relatively superficial. Even though the many small and medium-sized companies were merged to large industrial conglomerates, small-scale, historically grown structures remained intact below the surface (cf. interview I.b; I.c). Chemnitz’s important role within the overall national economy and a strongly dominating industrial sector, combined with the approach to build a model socialist city resulted in an ambiguous external perception of Chemnitz. One of our interviewees stated that the city was regarded from outside as a rather technocratic city without attractive cultural amenities (cf. interview I.h).

Unlike in Chemnitz, where investment in existing industries resulted in only a modest population growth, the expansion of local maritime clusters in Rostock led to continuous growth up until 1989. Rostock’s rise followed the strategic decision to create a state-owned commercial fleet and to establish an international seaport in order to become independent from neighbouring countries in international trade. This could only be achieved through large investments into new docks, port facilities and train connections as well as roads to the hinterland. The need for new ships resulted in investments in the shipbuilding industry in Rostock. In addition, SCPP supported the fishing industry by expanding the East German fishing fleet (Nuhn, Citation1997).

The stock of human capital in Rostock was insufficient to implement these plans, and workers, particularly engineers were needed. Relevant qualifications could mainly be found in the southern parts of the GDR. Therefore, SCPP offered special incentives to migrate to Rostock: Modern dwellings near the Baltic coast, far away from old industries and air pollution, as well as high salaries. The newly established international harbour strongly affected the city’s image. Rostock was regarded as the ‘GDR’s Gate to the World’ (Nuhn, Citation1997). Migrants from other regions endorsed this image and soon developed a strong personal identification with the city and its harbour (cf. interviews II.c; II.d).

5.1.2. Development after socialism

With the end of socialism came the end of competitiveness for almost all traditional industrial clusters in our case study cities. This led to plant closures and massive job losses. The reasons for this were manifold, including low productivity, a lack of Western technology standards in East German manufacturing, the breakdown of major sales markets in Eastern Europe, general structural change (changes in private demand, shift of production to low wage countries), East Germany’s entry to the German currency unionFootnote2 and individual mistakes during the process of re-privatization (cf. interviews I.i; IV.j).

In Chemnitz, the partial collapse of three major industries – engineering, automotive and textiles – caused a severe ‘identity crisis’ for the city and its inhabitants (cf. interview I.c). Though the city changed its name back to Chemnitz, the downturn of the local economy during the first half of the 1990s severely destroyed faith in the city’s citizens in its once very proud industrial tradition. For a relatively long period local development strategies almost neglected the manufacturing sector (cf. interview I.h). However, starting in the early 2000s, Chemnitz began a slow resurgence that followed old industrial pathways. Before the war, Chemnitz had a high level of self-employment. The rather superficial conglomeration process during GDR times with persistent small-scale firm structures under the surface of the large conglomerates meant the re-privatization process was more successful here than in other East German regions (cf. interview I.c). Some of the former directors within the industrial conglomerates, or in some cases even the employees themselves, took charge and, after a long period of economic struggle, were able to successfully reposition their businesses within a market economy. This revival of the old entrepreneurial culture was accompanied by several outside investments, partly promoted by managers with strong historical and/or personal ties to the city (cf. interview I.b). Today, the local economic structure is again dominated by small and medium-sized firms, with the automotive industry and mechanical engineering being core sectors.

While the regeneration of local industries took a relatively long time, many of our interview partners have claimed that the regeneration of local identity has taken even longer. First 20 years after German reunification, local decision-makers were turning their faces back towards Chemnitz’s industrial tradition in terms of place branding strategies. In 2009, the marketing label ‘modern city’ was established, reflecting the rediscovery of the city’s industrial tradition.

Unlike in Chemnitz, where economic resurgence can be linked to the adaptive resilience of small-scale structures in the local engineering cluster, the economy of Rostock in around 1989 was dominated by a few large conglomerates in the shipping, shipbuilding and fishing industries. These industries quickly collapsed after German reunification.Footnote3 Due to the new political geography in Europe, the international seaport lost its competitiveness to the much larger and more accessible ports in West Germany and the Netherlands. But global economic developments after 1990 worked in Rostock’s favour. European integration resulted in the emergence of ferry traffic as a rapidly growing sector around the Baltic Sea. Thanks to the docks built in GDR times and the city’s location, Rostock could attract a relevant share of this ferry traffic (cf. interviews II.b; II.e). A second new economic development path was the rapidly growing sector of cruise line business. As the East German fleet was already active in this business before 1990, one part was privatized and turned into a special shipping company for cruise liners (cf. interview II.g). Today Rostock is one of Europe’s most important ports for cruise ships. Also in favour of Rostock was the increasing global demand for seaport equipment. Once one of the port basins of the (former) international harbour was refilled, it was possible to develop a site for manufacturing, particularly for building dockside cranes. The plans to restructure the harbour, and in particular to transform the harbour basin into a production site for dockside cranes, were quite controversial and faced strong resistance from local initiatives (cf. interview II.a). Citizens of Rostock wanted to preserve all basins, as they regarded them as ‘the most precious sites of Rostock’ (cf. interview II.a) and a symbol for Rostock’s ambitions for playing a role as a relevant international seaport.

Although the structural problems after 1990 led to massive unemployment and the migration of many people to West Germany, according to our interviewees the general image of the city as a relevant seaport and a pleasant place to live near the coast remained positive.

5.2. Investments in new industries

5.2.1. Relevant support measures by SCPP

SCPP also invested in completely new regional production systems. Examples of these new clusters can be found in all our case study cities, but most of them did not take a leading role in the cities’ long-term economic development.

A strong impact of these strategies can be discovered in Weißwasser. The town’s impressive population growth since the 1960s () can be closely linked to the strategy of the GDR to become self-sufficient in the field of energy supply and therefore exploit the lignite deposits in the region of Upper-Lusatia. Key to this was the establishment of a power plant in nearby Boxberg, which, at its peak in the 1980s was the largest power plant in the GDR (Kabisch et al., Citation2004). Although the lignite mining and energy industry were not located within the city itself, Weißwasser received massive investments in new residential areas, cultural amenities and local infrastructure aimed at workers in the nearby industries. According to the number of workers living in the city, the lignite and energy industry became the most important sector for Weißwasser.

5.2.2. Decline of new industries since 1990

The decline of the lignite and energy industry is an ongoing process and job cuts proceeded more gradually than in other sectors (cf. interview IV.j). Although lignite mining in the region will fade in the near future, the lignite and energy industry shaped the economic landscape in and around Weißwasser in an influential way. Large areas occupied by the lignite mining industry have even reinforced the city’s peripheral location. In particular, infrastructure development in the surrounding region is severely restricted due to the low load-bearing capacity of the ground (cf. interview IV.e). As a result of these restrictions, Weißwasser today is not only truncated from Germany’s economic centres, but also from closer regional centres such as Cottbus, Bautzen and Görlitz. Moreover, the lignite and energy industry with its air pollution has contributed to an unfavourable image of the region in terms of quality of life. This partially suppresses potential tourism which, according to the local development strategy, is seen as an important future development path. Finally, the rapid rise of Weißwasser during GDR times resulted in a rather difficult relationship with neighbouring municipalities whose representatives are unwilling to accept the city’s central position within the region and therefore restrict opportunities of intermunicipal cooperation (cf. interview IV.g).

5.3. Changing a city’s administrative status

5.3.1. Measures to reconstruct public administrations

One goal of SCPP was to dismantle the historic administrative structures. After 1952, 14 new administrative regions (‘Bezirke’) replaced the six states (‘Länder’) that had emerged historically. The state authorities were dissolved and replaced new regional authorities (‘Räte der Bezirke’ and ‘Bezirkstage’) located in newly established regional capitals (‘Bezirksstädte’). An additional goal of these territorial reforms was to reduce the importance of old capital cities such as Dresden and states such as Saxony. From our sample, Chemnitz, Rostock and Suhl are examples of newly established regional capitals.

Suhl is a good illustration of a relatively small, peripheral town that strongly benefited from its new status as a regional capital. The city was chosen over the traditional capital city of Meiningen due to its industrial tradition and its relatively high proportion of manufacturing workers among its population. The status of ‘Bezirksstadt’ was combined with a strong influx of workers, the construction of new dwellings and the creation of expensive ‘GDR-style’ cultural amenities such as a congress hall and a concert hall with its own philharmonic orchestra.

5.3.2. What has remained after 1990?

After German reunification, the 14 GDR administrative regions were replaced by six federal states that reflected the old institutional set-up. Thus, eight cities, including all three regional capitals in our sample, lost their administrative status. The effect was rather inconsequential for Chemnitz and Rostock, which remained important regional centres due to their sheer size. In contrast, Suhl was much more severely affected by its loss of administrative status. Because the rise of the city during GDR times was very strongly linked to its assignment of regional capital functions, the same can be said for its continuous downturn since 1989. Due to its relatively peripheral location within Germany and the end of the local moped production in 1996, Suhl was unable to compensate for the loss of centrality caused by the change in its administrative status.

The city’s dependence on public administration during GDR times has led to barriers against adapting to new paths of urban economic development. After 1989 local policymakers wanted Suhl to remain a central hub for the entire region, with a strong focus on the service sector, and neglected new investments in the field of manufacturing (cf. interview III.a).

The extensive GDR infrastructure, designed for a population of up to 100,000 inhabitants (cf. interview III.d), and the extraordinary social and cultural amenities still generate exorbitant maintenance costs for the small city (today about 35,000 inhabitants). This prevents it from making important investments for future urban development (cf. interview III.e). Although some of the amenities, such as the philharmonic orchestra, have already been dismantled, any potential reductions in public infrastructure face strong opposition from the local population, which has become accustomed to an outstanding level of cultural amenities. While the inhabitants and decision-makers in Suhl keep up to the idea of being the ‘capital city’ of Southern Thuringia (cf. interview III.a), other municipalities in the region still ‘feel discriminated’ (cf. interviews III.a; III.d; III.e), as the ‘red Suhl’ (interview III.f) had been prioritized by the socialist regime. Therefore, neighbouring municipalities are unwilling to cooperate with Suhl, for example, in the field of business development.

5.4. Socialist urban renewal

5.4.1. Implementing plans for ‘socialist cities’

Instead of rebuilding the inner cities in a way that would retain their traditional character, the GDR aimed at creating completely new inner cities that reflected the ideas of socialist urban planning. This included broad streets, large squares for mass events and large modernist buildings such as event halls, and was often complemented by new residential areas with huge prefabricated housing blocks.

While in Rostock and Weißwasser urban planning was mainly directed at developing completely new districts outside the core cities, Chemnitz and Suhl are good illustrations of ‘socialist urban renewal’. Due to their largely industrial character both cities were chosen as model socialist cities, demonstrating the triumph of the industrial working class over old commercial and ‘bourgeois’ structures. In Chemnitz, the process of socialist urban rebuilding was closely linked to the change in name to ‘Karl-Marx-Stadt’ in 1953 and to the new status of a district capital and resulted in the demolition of some of the few historical structures within the city centre that had survived Allied bombing during the war (Viertel & Weingart, Citation2002). During the 1970s, the renewal of the inner city was abruptly halted and resources were bundled into the new socialist-style residential area ‘Fritz Heckert’, one of the largest prefabricated building settlements in the GDR.

Like in Chemnitz, the transformation of Suhl’s city centre was linked to its assigned status of a ‘Bezirksstadt’. Although the inner city was not severely damaged during the Second World War, the historical structures (of a country town with small, unpretentious buildings) were torn down and replaced by socialist style buildings (cf. interview III.a).

5.4.2. Legacies from built structures

After 1990, the results of socialist urban reconstruction made it difficult for the inner cities to attract tourism and other kinds of consumer activities and therefore hampered the emergence of new growth paths in retail and services. They also had negative long-term consequences for the internal and external perception of Chemnitz and Suhl and their attractiveness as a location for firms and private households (cf. for the case of Suhl; interview III.d). Both cities continue to suffer from their image as ‘old’ and ‘grey’ industrial cities with a lack of urbanity and historical sites. In the words of one of our interviewees, ‘Chemnitz has been destroyed twice, first by allied bombing and then by reconstruction under the socialist regime’ (cf. interview Ia).

The opportunities of local policymakers to tackle this legacy were limited. The complete reconstruction of the old urban structures was too costly for the financially strapped medium-sized cities of Eastern Germany and there was often a lack of alternative concepts that met the diverging interests of various stakeholders. For example, in Chemnitz during the 1990s and early 2000s, local planning policies mainly focused on the dismantling of old Wilhelmian buildings as a reaction to urban population shrinkage and on the upgrading of residential areas from socialist times. Today these neighbourhoods are perceived as socially deprived problem areas. In Suhl, both citizens and local policymakers were devoted to conserving the building tradition of the GDR (cf. interview III.a). In Chemnitz, since 2009, the city has used the label ‘modern city’ for marketing purposes, primarily referring to its industrial history but also to its modernist cityscape which had been deeply shaped by SCPP. This could be seen as an attempt to use the GDR legacy for creating a more positive image of the city.

6. DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSIONS

As explained above, qualitative interviews as the main data sources for our case studies have several deficiencies. Therefore, our findings and the following conclusions have to be read with some caution. Bearing these constraints in mind, we would at first summarize that the legacy of SCPP in our four case study cities was obviously in general a factor hampering the evolution of successful new economic trajectories after the return to a market economy – and many of these long-term effects of SCPP are still at work. In general, the impact of SCPP on urban development may be classified as just past dependence. But we have also identified some mechanisms which show similarities to the concept of path dependence.

Quite obvious are the negative effects of SCPP in the fields of investments in existing and in new industries. Following the general efficiency problems of state-owned enterprises and central planning, after 1990, the main industries in our case cities were not competitive, and many businesses went bankrupt. In Western countries, some of these industries (as the production of glassware and mopeds) had been under pressure since the 1970s, but many cities and regions took the opportunity to adapt towards new growth trajectories. Under SCPP the old industrial structures were conserved until it was too late. This tendency resembles the outcome of path dependence in some old industrial regions in Western countries. But in socialist countries, the tendency to avoid a change towards new trajectories was more or less ubiquitous. Moreover, these mechanisms stopped abruptly by the end of socialism.

The two larger cities within our sample were more successful in repositioning themselves than the smaller cities. While this certainly is associated to general agglomeration benefits of larger cities, the economic revival of Chemnitz and Rostock is also closely related to the efforts of local decision-makers to take advantage of local assets and turn the industrial legacy into new pathways. In Chemnitz this was strongly associated to the entrepreneurship culture that has survived the era of SCPP and the ‘quasi conservation’ of pre-socialist structures of businesses. Historical structures, evolved long before the socialist era, were more persistent than the efforts of SCPP to influence the city’s industrial structure. While the industries in Rostock had more problems to survive the post-socialist transition, the city was able to take advantage of the mega-investments by SCPP in maritime infrastructure, roads and railways to the hinterland. Based on these measures, a new cluster of businesses could evolve.

One of our most interesting findings is the relevance of the legacy from SCPP for different categories of ‘soft’ factors such as local identity and image and the attitudes of residents, local decision-makers. In the case of Rostock, the GDR had the intention to develop a positive picture of the city in the eyes of the local population and within the general public opinion – it was necessary to stimulate migration to the city and to legitimate the massive investments in the new international seaport. This positive picture is still existing and is supporting today’s economic development in Rostock.

For the other three cities, SCPP had a negative impact on their outside perception and a lot of these negative images are still alive. As Suhl and Weißwasser had been privileged in relation to the neighbouring regions, people and decision-makers from these regions still have their reservations against the cities, especially with regard to intermunicipal cooperation. This results in negative implications for the economic recovery of both cities. In addition, according to our interviewees, the supra-regional perception of Chemnitz, Suhl and Weißwasser is still quite negative. With regard to Chemnitz and Suhl, this is mainly due to socialist urban renewal policy. Weißwasser and its region are perceived as places with a low quality of life, following the extension of opencast mining and air pollution by power plants under the socialist regime.

Surprisingly, in Chemnitz and Suhl there have been only slight efforts to change the negative perception of cities caused by socialist urban renewal. For a long time, citizens and policymakers were devoted to conserve the socialist urban structures – a long-term effect of SCPP on local identity. Similar was the situation in Rostock, where residents tried to prevent the transformation of a harbour basin into a production site, as the construction of this basin was seen as an outstanding milestone for the upturn of the city during socialist times.

The impact of the described ‘soft’ factors may be interpreted as more than just ‘past dependence’, but we were not able to identify clear mechanisms of self-reinforcement after the end of socialism. All in all, on the base of our case studies, we would conclude that there are just slight similarities between the long-term effects of SCPP and the typical mechanisms of path dependence.

Finally, what are our general conclusions for the discussion on diverging development paths of post-socialist cities? With our case studies, we have discovered a few factors of SCPP that have supported and several other factors which have impeded the local economic recovery process. Most relevant were different categories of ‘soft’ factors. Future research should use these results as hypotheses for broadening the empirical base of our findings, especially by looking at cities in other post-socialist countries in Europe or the rest of the world that have experienced significant SCPP measures in order to change their economic development trajectories and faced similar challenges of adaptation within a market economy. Since the post-socialist transition process in East Germany differed from processes in most other post-socialist countries, it would be additionally interesting to examine more closely the interplay between the impact of SCPP and spatial policies after 1989 on urban economic development, as well as strategies which had been successfully used by post-socialist cities in order to overcome the long-term negative effects of SCPP, in particular with regard to ‘soft’ factors such as local image and identity.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (101.8 KB)ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors express their gratitude to their former colleagues from the research field of urban economics at the Leibniz Institute for Economic Research in Halle (Saale) for their support during this research project. Special thanks to Peter Haug for conducting the expert interviews in Suhl. We also thank all our local interview partners as well as the anonymous reviewers of this paper. The research presented in this paper is partly based on Heiders (Citation2019a).

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 As East Germany’s urban system consists of mostly rather small cities, and since there are only three major agglomerations with more than 500,000 residents in East Germany (Berlin, Dresden and Leipzig), cities with around 200,000 residents may be categorized as relatively large.

2 One strategy of SCPP was to sell products to Western countries below world market prices with the aim of maximizing foreign currencies. After the currency union, prices of East German products such as guns, mopeds and glassware immediately became far too expensive for consumers.

3 Although the federal and state governments initially tried to support shipbuilding through massive subsidies (cf. interview II.a).

REFERENCES

- Arthur, W. B. (1989). Competing technologies, increasing returns, and lock-in by historical events. The Economic Journal, 99(394), 116–131. https://doi.org/10.2307/2234208

- Arthur, W. B. (1994). Increasing returns and path dependence in the economy. Ann Arbor, 224. https://doi.org/10.3998/mpub.10029

- Berentsen, W. H. (1987). Settlement structure and urban development in the GDR, 1950–1985. Urban Geography, 8(5), 405–419. https://doi.org/10.2747/0272-3638.8.5.405

- Bröcker, J., & Richter, F. (1999). Entwicklungsmuster ostdeutscher stadtregionen nach 1945. In L. Baar, & D. Petzina (Eds.), Deutsch–Deutsche Wirtschaft 1945 bis 1990. Strukturveränderungen, Innovationen und regionaler Wandel. Ein Vergleich (pp. 98–136). St. Katharinen.

- Cantos, P., Gumbau-Albert, M., & Maudos, J. (2005). Transport infrastructures, spillover effects and regional growth: Evidence of the Spanish case. Transport Reviews, 25(1), 25–50. https://doi.org/10.1080/014416410001676852

- Cleave, E., Gorku, A., Sadler, R., & Gilliand, J. (2016). The role of place branding in local and regional economic development: Bridging the gap between policy and practicality. Regional Studies, Regional Science, 3(1), 207–228. https://doi.org/10.1080/21681376.2016.1163506

- Clifton, N. (2011). Regional culture in the market place: Place branding and product branding as cultural exchange. European Planning Studies, 19(11), 1973–1994. https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2011.618689

- David, P. A. (1985). Clio and the economics of QWERTY. American Economic Review, 75(2), 332–337.

- David, P. A. (1994). Why Are institutions the ‘carriers of history'? Path dependence and the evolution of conventions, organizations, and institutions. Structural Change and Economic Dynamics, 5(2), 205–220. https://doi.org/10.1016/0954-349X(94)90002-7

- Démurger, S. (2001). Infrastructure development and economic growth: An explanation for regional disparities in China? Journal of Comparative Economics, 29(1), 95–117. https://doi.org/10.1006/jcec.2000.1693

- Duranton, G., & Puga, D. (2004). Micro-foundations of urban agglomeration economies. In J. V. Henderson, & J. F. Thisse (Eds.), Handbook of regional and urban economics, 4 (pp. 2063–2117). Amsterdam. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1574-0080(04)80005-1

- Fritsch, M., & Wyrwich, M. (2014). The long persistence of regional entrepreneurship culture: Germany 1925–2005. Regional Studies, 48(6), 955–973. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2013.816414

- Fritsch, M., & Wyrwich, M. (2016). The effect of entrepreneurship on economic development – An empirical analysis using regional entrepreneurship culture. Journal of Economic Geography, 17(1), 157–189. https://doi.org/10.1093/jeg/lbv049

- Golubchikov, O. (2006). Interurban development and economic disparities in a Russian province. Eurasian Geography and Economics, 47(4), 478–495. https://doi.org/10.2747/1538-7216.47.4.478

- Grabher, G. (1993). The weakness of strong ties – The lock-in regional development in the Ruhr area. In G. Grabher (Ed.), The embedded firm – On socioeconomics of industrial networks (pp. 255–277). London: Routledge.

- Grubbauer, M., & Kusiak, J. (2012). Introduction. In M. Grubbauer, & J. Kusiak (Eds.), Chasing Warsaw – Socio-material dynamics of urban change since 1990 (pp. 9–24). Frankfurt.

- Haase, A., Wolff, M., Špačková, P., & Radzimski, A. (2017). Reurbanisation in postsocialist Europe – A comparative view of eastern Germany, Poland, and the Czech republic. Comparative Population Studies, 42(1), 354–389. https://doi.org/10.12765/CPoS-2018-02

- Hassink, R. (2010). Locked in decline? On the role of regional lock-ins in old industrial areas. In R. Boschma, & R. L. Martin (Eds.), Handbook of evolutionary economic geography (pp. 450–468). Cheltenham.

- Heider, B. (2019b). What drives urban population growth and shrinkage in postsocialist east Germany? Growth and Change, 50(4), 1460–1486. https://doi.org/10.1111/grow.12337

- Heiders, B. (2019a). The impact of institutional change on urban growth and decline: Lessons from East Germany (1990–2015) (dissertation). https://doi.org/10.25673/14115

- Henning, M., Stam, E., & Wenting, R. (2013). Path dependency research in regional economic development: Cacophony or knowledge accumulation? Regional Studies, 47(8), 1348–1362. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2012.750422

- Hirt, S. (2013). Whatever happened to the (post)Socialist city? Cities, 32(1), S29–S38. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2013.04.010

- Hudson, R. (1994). Institutional change, cultural transformation and economic regeneration: Myths and realities from Europe's old industrial regions. In A. Amin, & N. Thrift (Eds.), Globalization, institutions and regional development in Europe (pp. 331–345). Oxford.

- Kabisch, S., Bernt, M., & Peter, A. (2004). Stadtumbau unter Schrumpfungsbedingungen - Eine sozialwissenschaftliche Fallstudie. Wiesbaden.

- Kauffmann, A. (2009). Von der Bezirks- zur Landeshauptstadt: Zum Einfluss der Zuordnung staatlicher Funktionen auf das ostdeutsche Städtesystem. Wirtschaft im Wandel, 12, 523–532.

- Krugman, P. (1991). History and industry location: The case of the manufacturing belt. American Economic Review: Papers and Proceedings, 81(2), 80–83.

- Martin, R., & Sunley, P. (2006). Path dependency and regional economic evolution. Journal of Economic Geography, 6(4), 395–437. https://doi.org/10.1093/jeg/lbl012

- Nuhn, H. (1997). Hansestadt Rostock: Vom maritimen Tor zur Welt zum Regionalhafen für die Ostsee. Europa Regional, 5, 8–22.

- Nuissl, H., & Rink, D. (2005). The “production” of urban sprawl in eastern Germany as a phenomenon of post-socialist transformation. Cities, 22(2), 123–134. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2005.01.002

- Pierson, P. (2000). Increasing returns, path dependence, and the study of politics. American Political Science Review, 94(2), 251–267. https://doi.org/10.2307/2586011

- Pierson, P. (2003). Big, slow-moving, and … invisible: Macrosocial processes in the study of comparative politics. In J. Mahoney, & D. Rueschemeyer (Eds.), Comparative historical analysis in the social sciences (pp. 177–207). Cambridge. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511803963.006

- Putnam, R. D. (1993). Making democracy work. Civic traditions in modern Italy. Princeton.

- Raagma, G. (2002). Regional identity in regional development and planning. European Planning Studies, 10(1), 55–76. https://doi.org/10.1080/09654310120099263

- Rink, D., Couch, C., Haase, A., Krzysztofik, R., Nadolu, B., & Rumpel, P. (2014). The governance of urban shrinkage in cities of post-socialist Europe: Policies, strategies and actors. Urban Research and Practice, 7(3), 258–277. https://doi.org/10.1080/17535069.2014.966511

- Runge, A., Runge, J., Kantor-Pietraga, I., & Krzysztofik, R. (2020). Does urban shrinkage require urban policy? The case of a post-industrial region in Poland. Regional Studies, Regional Science, 7(1), 476–494. https://doi.org/10.1080/21681376.2020.1831947

- Sagan, I. (2014). Integrate to compete: Gdansk–Gdynia metropolitan area. Urban Research and Practice, 7(3), 302–319. https://doi.org/10.1080/17535069.2014.966512

- Simmie, J. (2012). Path dependence and New technological path creation in the Danish wind power industry. European Planning Studies, 20(5), 753–772. https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2012.667924

- Sjöberg, Ö. (1999). Shortage, priority and urban growth: Towards a theory of urbanisation under central panning. Urban Studies, 36(13), 2217–2236. https://doi.org/10.1080/0042098992395

- Storper, M. (2010). Why does a city grow? Specialisation, human capital or institutions? Urban Studies, 47(10), 2027–2050. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098009359957

- Tsenkova, S. (2014). Planning trajectories in post-socialist cities: Patterns of divergence and change. Urban Research and Practice, 7(3), 278–301. https://doi.org/10.1080/17535069.2014.966513

- Viertel, G., & Weingart, S. (2002). Geschichte der Stadt Chemnitz – Vom locus Kameniz zur Industriestadt. Gudensberg.

- Wolfe, D. A. (2010). The strategic management of core cities: Path dependence and economic adjustment in resilient regions. Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society, 3(1), 139–152. https://doi.org/10.1093/cjres/rsp032